Contents

Featured Articles

Accretion Desk by Martin Horejsi

Jim's Fragments by Jim Tobin

Micro Visions by John Kashuba

Mitch's Universe by Mitch Noda

MeteoriteWriting by Michael Kelly

Terms Of Use

Materials contained in and linked to from this website do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of The Meteorite Exchange, Inc., nor those of any person connected therewith. In no event shall The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. be responsible for, nor liable for, exposure to any such material in any form by any person or persons, whether written, graphic, audio or otherwise, presented on this or by any other website, web page or other cyber location linked to from this website. The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. does not endorse, edit nor hold any copyright interest in any material found on any website, web page or other cyber location linked to from this website.

The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. shall not be held liable for any misinformation by any author, dealer and or seller. In no event will The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. be liable for any damages, including any loss of profits, lost savings, or any other commercial damage, including but not limited to special, consequential, or other damages arising out of this service.

© Copyright 2002–2024 The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. All rights reserved.

No reproduction of copyrighted material is allowed by any means without prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Vouillé Rings a Bell: Soon, another 200 year old meteorite will already be in my collection.

Martin Horejsi

One of the benefits of growing old, if there are any, is that sometimes you forget things. Like that you have a large piece of a particular historic French meteorite from 1831 in your collection. And this happened to me recently.

Meteorite Times Magazine

It all started with a for sale notification that popped up in an email. A familiar meteorite name was listed was named Vouillé. While the offering was not a large specimen, and by large I mean over a gram. And by not large, I mean under a gram, the name did ring a bell. It occurred to me that I did have a piece of that location in my collection, but I had not seen it in years. I forgot about the situation for a while until I was looking for a different specimen and realized that the size and shape of my piece of Vouillé would relegate it to a nondescript paper box rather than a transparent display case, or even better, a coveted spot in a glass cabinet.

Meteorite Times Magazine

So I took a moment one day and dug around for what I remembered as the box that held Vouillé the last time I saw it. Sure enough, there it was, just sitting at the bottom of a safe waiting for rediscovery.

Meteorite Times Magazine

I like to imagine what something looks like before the big reveal after I have not seen it in years. And Vouillé looked just like what I remember. This is likely because I spent so much time with my polished, crusted fragment of Vouillé years ago when I wrote an article about it here in the Meteorite Times

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

That was back in May of 2009, some 15 years ago! So much has happened since then, but I still have a clear picture in my mind about Vouillé and how I got it. I won’t drill down into the gory details again since that is already chronicled in the linked article, but I will say that given the sale notice that started this conversation with both myself and you, the price has possibly yet again gained a zero. Or at least part of one!

Meteorite Times Magazine

In seven years, Vouillé will join a select few meteorites whose fall was witnessed, documented, and preserved from over 200 years ago. I have not checked to see if there are any major changes in the global distribution of Vouillé ,but I doubt it. While so much in the meteorite world has changed, and even more in the meteorite collectors realm, one thing is certain and that is historic witnessed fall meteorites for sale or trade are few and far between. In fact even entire collections of meteorites have been built with few or no witnessed falls of any vintage, and often very few meteorites named with a known location that is not followed by a number.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Now meteorites are meteorites, but my collecting interest involves a human element mixed in with science and planetary geology. The hot desert stones and irons, and even the cold desert ones for that matter, all follow a similar trajectory beginning with a ground level story. Personally, I enjoy the thunder and lights that accompany fresh material, and the reactions humans have for such events. I guess I too am writing my own story here as well in that my intersection with meteorites involves the events post-landing that continue the storied man/meteorite relationship that seems as old as time. So I’m doing my part.

Until next time….

Meteorite Times Magazine

Looks Aren’t Everything

James Tobin

Over the last several decades I have sent off meteorites to be classified and have a couple going through the process nearly all the time now for fun. There are some troublesome questions that come up along the way on some meteorites. It might be an instructive discussion of how some of these potential pit falls can be avoided when working with meteorites worthy of being classified. And also, I will relate some of the issues with an unsolvable condition in the meteorite community. That being the visual pairing of meteorites and the use of names and designation gotten by others. These are problems that have existed for nearly three decades and will likely never be satisfactorily resolved. I won’t even be trying to rehash all of the many points of view. I will just discuss a few to describe the issues and problems I see.

That statement about meteorites worthy of getting analyzed might be misleading since all meteorites are rare material and one could argue that all space rocks are worthy of scientific study. I would agree with that if the system for classifying them had the resources and the experienced personnel to do the specialized work required to get fine classifications for all the meteorites. The reality is that there is a backlog of meteorites in the pipeline all the time and there are not the resources to analyze every piece of meteorite. So we acquire or find meteorites and if the ones we acquire are special then we send them in to be made official. The ones I find at new locations I always send in and get classified that’s seems to be very important to me as a hunter. The cost and time for the work to be done is not a very important factor to me with personal finds. I just want to know what I have and make them officially listed meteorites.

There is another factor to initially consider and then dismiss for the balance of this article. It costs a chunk of change now to get meteorites classified and if it is a few small pieces of an unremarkable old north African meteorite, it is not going to sell for a profit after paying for the classification work. It is better to grind and polish a window on the stones to expose the nickeliron metal grains and the chondrules if there are any. That will prove to the buyer that it is a real meteorite. Just sell it as an Unclassified NWA and be done.

What if it is a single big stone, or many nice size stones, or dozens of small stones that deserve to be studied. What happens then and what are the pitfalls in these cases?

First the one big stone. There are essentially no pitfalls with this. You follow the rules and that’s it. Send in the cut off piece for the type specimen. The requirement is 20 grams or 20%, but you can send more if you feel like it. Give all the answers about where it was found or bought, by whom, when, how much it weights, and was it seen to fall or was it a find. Then wait for the results of the testing to be sent after a while. Make the submission to the governing body of the Meteoritical Society (the nomenclature committee) and see your space treasure get a name or designation with your name as the main mass holder. Done deal after what can be a long wait sometimes. That is how it normally goes with a find and submission of a meteorite sample. Patience is important and not bugging the scientists is super important. They have a lot of them to do all the time.

Meteorite Times Magazine

For those in my audience who are new to studying meteorites try to make sure you have a real meteorite before you send it off to be analyzed. Have someone with some knowledge of meteorites look at it. Do some of the basic tests before sending off just a funny looking rock. There is information available readily about the initial home testing of suspected meteorite rocks. Most places will not return the non-meteorite samples sent to them. If you want your sample back, make those arrangement and provide prepaid postal return supplies. Contact the lab before sending to make sure they are accepting stones for testing.

Let me just mention that many times a thin section is still made. That can take a long time depending on factors like if the lab can make their own. Or if they have to send a wafer or the type specimen to a commercial manufacturer of thin sections. Often this alone can create a month or two of time in the classification process after yours reaches the top of the backlog.

Secondly, the case of the several nice size stones. First problem to discuss. Were you the finder or was that finder far away and you bought the stones? Do you have great confidence that when the finder guarantees that the pieces were all found at the same location, and away from other meteorites finds, you can believe that totally. Along with that is the next issue. Do the pieces all have characteristics that identify them as being the same. Is the fusion crust the same in appearance indicating the same terrestrial age and weathering experience for the various stones? Do broken surfaces expose interior texture, color, and appearance that is the same for all pieces with broken surfaces? Do the pieces have the same amount of metal and do the chondrules if any have the same appearance, density and color range? Is the matrix the same color and mottling the same? Are the rust halos similar for all the pieces? These type questions can go on and on. The point is that unless you are going to send in a cut piece from every one of the several pieces, your best estimation of the stones in comparison to each other must be made if you did not find them at the same location. Or even if you did find them at the same location. More about that later.

This gets further complicated when there are say three stones found and they are quite pretty in their shape and form. They may have nice fusion crust and are not broken. It can be hard to identify related meteorites if none of the insides show. And if they are pretty, you and your partners may want to not cut them. Each may want to keep a whole individual. You will need to cut one of them and divide it to balance the shared weight to each partner in the purchase. And you will be forced to send in the type specimen from that one cut individual as well. Here is the problem.

Are the other stones the same? How do you know if you cannot see inside because they are too attractive to cut? Well the answer is you cannot be 100% sure. But is that a reason to feel completely unsure about the uncut stones. Not necessarily. It does become a matter of trust to an extent. If you are working with a finder, then it is quite likely that they were found at the same location. If you are working with a subsequent seller than it might not be so good. Similar looking meteorites could be mixed up to make a larger more profitable sale and who would ever know until much later. Or never or perhaps not until years later when you cut and try to sell your stone, or your heirs have to sell your collection. And it is then cut by a buyer who finds it is not like the classified piece. One could go nuts thinking about all these conditions. But preserving pieces uncut in two and three stone finds happens often.

If you are a collector, then the situation is different too from the experience of a dealer in meteorites. The dealer is saying that all the meteorites he is calling something are exactly that.

Meteorite Times Magazine

They have done their very best to maintain a property chain of custody on the stones all through the purchasing, shipping and preparation phases of handling the stones. In the end if all goes well when the various stones are cut, they will look the same, slice to slice and endpiece and complete stones. If there are pieces that look different a responsible dealer will know that it is best to remove those and sell them as unclassified pieces that have gotten into the batch at the beginning. Usually that does not happen if the stones were bought from a good reliable source in the first place.

The third of these first situations, the batch of numerous small stones that was worthy of being classified. It is impractical to cut a piece off of every stone and have it classified. That is just an insane thought if there are hundreds or thousands of pieces. Besides the fact that there may again be many very nice pieces that are complete or nearly complete that should not be cut into because of their beauty. Oriented pieces for instance that are complete. Who in their right mind would chop them up to make sure a 100% they are the same. At some point you have to let go just a little bit and say something like, “They were found at the same place at the same time and have been together as a uniquely kept batch from then on. They in all respects appear the same so they are the same.”

For a moment lets look at a very strange and unique event that happened a few years ago. The asteroid that formed the Almahata Sitta meteorites was tracked from space. The exact landing zone was known, and the pieces of the meteorite were recovered. It was officially classified as a Ureilite, polymict, anomalous. Since that original classification was done, the specimens were found to exhibit multiple distinct lithologies, ranging from ordinary chondrite to bencubinnite. Certainly the only way to be sure you have an Almahata Sitta is to trust the person you are acquiring the specimen from. There is no standard specimen type to go by or appearance to trust as pieces from this fall can be almost any type of meteorite. It remains the only meteorite found at that location to the best of my knowledge so any fragment found there even at this time would probably be called Almahata Sitta I suppose. How would anyone know different?

As terrible and risky as visual pairing of meteorites can be, it is almost a necessity in some circumstances where hundreds of pieces are involved. There just are no resources to test every piece. But here the next problem arises. A batch of all similar stones are found at a location and representative pieces are sent to be analyzed. They were all collected by a single finder or group of finders at the same time. All that is good they get a name or designation. Later someone else goes and finds meteorites and claims that they are “paired” to the first batch. Were these later meteorites found at the same location or were images of hundreds of meteorites examined online until a close visual match was found and then with a “who will ever know attitude” said to be visually paired? Once again, we are seemingly forced to trust in the meteorite dealer and finder.

Is there good and bad pairing? Yes, I think that there is. Bad pairing is what I just described. Looking at images of meteorites with the intent of finding something close enough to call another already classified meteorite. There is from the beginning of that the intent of avoiding the costly and time consuming process of getting a classification. Profit is the only consideration. I have no idea to what extent such a blatantly wrong way of saying stones are pair happens. Rarely I would guess and hope. Doing pairing in a much better way and arriving at a profitable outcome is not that hard. Just go to the location and find more meteorites and then compare what you have found to what was found before. Then guarantee you have not found any other type meteorite within the same strewnfield area. Let the world know that they

Meteorite Times Magazine

have been only visually paired but found at the same location. Be transparent about the persons who found these additional pieces and when. It would never be a bad thing to show images of the fun hunt, and hunters, and the location on the sales pages. Don’t sell any pieces of meteorite that look different. Grind or cut a sample of the stones recovered and examine the inside also. Once everything is seen to be correct the meteorites can be confidently offered for sale as “Visually Paired with XXXXX meteorite.” Is there still a risk that they are not. Of course. Again not all the stones are being laboratory analyzed and not everyone of hundreds or thousands can ever be checked in a lab. Multiple meteorite falls in the same location have happened repeatedly. As metal detectors have improved and hunting has become more intense all the old falls of an area are discovered. It is possible to have several meteorites being recovered from one place.

When I go and find meteorites at Franconia am I 100% sure that they are actually Franconia’s and not Palo Verdes Mine or another of the several meteorites found in the area. No not a 100% every time. It depends a little in what part of the vast area I am finding them. It depends a bit more on how the detector responded to them. I think I can always tell very low metal fresher LL stones from the regular Franconia’s. I never sell the meteorites I find. I suppose if I discovered a strewnfield during one of my trips every few days out into the desert I would probably sell some. Then I would want to make sure all were from the same fall event. But regardless of whether or not I sell them they go into my collection, and I want my data for the specimens to be accurate and so I visually examine the finds to see if they are normal for where I found them.

Visual pairing is exactly what it reads. The meteorites are looked at and a determination is made. It is dangerous because not everyone has an equal level of knowledge or awareness about what should be looked at and looked for. It is much more than the color on the outside or the state of the sandblasting of the fusion crust or the development of the desert patina. It involves looking at the type, size, and color range of the chondrules. Does the meteorite that was lab classified have shock veins and clasts of different colors and textures? Do the meteorites later found have the same kind of melt pockets and weathering features? There is a long laundry list of characteristics that should all match very well before a meteorite is said to be paired. The most important thing remains. They must have been found at the same location or exceedingly close. There is nothing wrong with expanding a strewnfield’s size by further exploration and making additional finds. But miles apart with no continuation of finds between locations maybe suspect. Same location is the best fact and place to begin when saying that the stones are from the same event.

Even with individuals possessing great experience and knowledge visual paring will sometimes be a problem. Some meteorites are not homogeneous throughout even a single stone. They may be brecciated stones that are largely one kind of clasts in one part and other types of clasts in other parts. It has happened before that meteorites were classified as a certain meteorite from one type specimen and were actually something related but different because the submitted type specimen was not representative of the whole meteorite. A case in point could be a Howardite where the type specimen does not show the amounts of diogenite and eucrite to get that classification and it ends up being either a eucrite or a diogenite. Later it might be corrected with further work as a Howardite. A classic example is Al Haggounia 001. The chondrules in it are so scattered and rare that in some pieces a single chondrule may only be seen after dozens of slices have been taken. It was for a long time classified as an Aubrite.

Chemically accurate but structurally wrong as it has very rare chondrules and is therefore not an

Meteorite Times Magazine

achondrite. Those of us who have cut hundreds of pieces of Al Haggounia 001 knew this for years. We can even tell from the color of the mud produced during cutting and lapping that we have another piece of Al Haggounia 001 in mixed batches of UNWA material. But it took a while for it to be reexamined and reclassified as an Enstatite Chondrite.

Visual pairing will never be free of problems but the negative impact on collectors and dealers can be minimized by doing a careful and throughout examination and not just finding something that looks enough alike inside and out to sell.

We have always chosen to be very selective in business of who we obtain meteorites from. We have over the decades gotten our own classifications for meteorites that were special enough to warrant the cost and time. We have only worked from single stone meteorites per classification in nearly all cases. This has made it easy to say that something is what it is. The only issue at all is the actual handling of the cut pieces in the lab, so they do not become mixed ever. But that is fantastically easy. Just only work on one stone at a time and copiously mark all plastic baggies with a black felt marker at every stage of the preparation work. Label cans of desiccant with the name or number of the single stone’s slices they contain between stages when pieces need to rest in a dry place. Lab control is not difficult, but it is essential.

Pairing of meteorites has become especially problematic with the exotic planetary meteorites, the Martians and the Lunars. Are there really over 600 unique meteorites related to the Moon? Are there really 380 individual meteorites related to Mars? No I don’t actually think so. I don’t think anyone does now. We know that many of the classifications are related. Some meteorites have been classified in many labs in many countries repeatedly. Often with these exotic types it has been too expensive to buy all that was available. The pieces recovered were sold individually and separated from other pieces found at the same time. There is a strong desire among finders, collectors, and dealers to obtain their own designation or name for these special meteorites. So often there are multiple names for the same find location.

It is expensive to get Martian and Lunar meteorites classified. In the old days when Lunar and Martian meteorites sold for a few hundreds of dollars per gram just giving up that 20 grams minimum amount for the type specimen was thousands of dollars of lost sales. Then on top hundreds of dollars more for the lab work and scientist time. The price on some Lunar and Martian meteorites has come down so the pain of giving up the material is less but the costs for getting the classification work have not come down and the time is still whatever is required. There was the additional desire to get on the market as soon as possible before another classified stone from those first finds was being sold. Fears that collectors had gotten what they needed thus making later sells of identical material harder.

It is not hard to see the motivation to avoid those expenses. Doing a pairing with another meteorite is an urge hard for some to resist. If the meteorite being paired is truly found at the same location and looks the same, then I personally have little current objection to the practice. With the understanding that it must be a real knowledgeable pairing and the location the same with evidence that it is the same place, i.e. in situ and terrain photographs.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

The four images above are samples that look initially quite similar. Would you like to put the names or designations on them just from looking at these images? I would not want to do that. The reality is that some might be from the same location and event.

If someone comes along which might happen, I will be disappointed and angry about a visual pairing to one of my classified meteorites. I am sure when the name attached to my classification is appropriated at no expense by someone else, I will be very upset. I am not a saint after all. I can feel in myself the urge to jealously defend my location name. Almost like a sandworm defending a spice field. I will want evidence that the supposedly paired stone was found at the same place and looks the same in all regards. I know also that it will be a hopeless effort and it would be better for my mental health if I just let it go. It is a fact of life that some people will do anything to save and make a buck.

Who suffers with bad visual pairing? Well we have discussed a lot of that already, but science really suffers also. The data we all use is corrupted by false or faulty pairings. The true information about the amount of meteorite actually recovered from a location is no longer trustworthy and accurate. It is also a disservice to genuine hunters who go to the location after more has been stated to have been found. They go only to discover that there is really no more

Meteorite Times Magazine

meteorite to find because the only real amount was the first true recovery.

After going through all the work, cost, and waiting to get a meteorite classification is the name of the meteorite yours and yours alone to hold and use? Should you have a say in how it is used and when and by whom? More sometimes difficult questions. A case can be made that it is similar to the address of your house. You likely did not create the address. That was done by the land developer with the city’s approval. But when you buy the lot and the home the address is yours and yours alone to use. If someone went to the local mailbox store and signed up for a box with your address and began getting your mail maliciously that would be a crime, mail theft. We don’t always have much input as to the exact name of the meteorite if it is from a Dense Collection Area (DCA) which only has number designations. Other times when we have all the find data for a meteorite we recovered, we do get to have something to say about the name it receives. If it is a single stone discovery and we have all of the meteorite, do we have control of the use of that name? Or can others just claim that they have found more and use the name? The various meteorite organizations have created some rules for their members on these issues, but none really have any authority to enforce their rules on the many people who operate outside those various organizations. Stay in this field long enough and find meteorites on a regular basis and this will become an issue you consider. Do I really “own” the name of the meteorite I found if I retain all of the material recovered?

For a next few sentences let me use a real world case as an example of some of this discussion. NWA 14370 is a classified meteorite that Jason Phillips and I worked on as one of our fun projects. We acquired all there was of the meteorite. It was 3071 grams in 45 pieces. It was all purchased with no location known. It is a nice looking brecciated eucrite. Some pieces have patches of fresh fusion crust. Some pieces have been sliced by me and sold to my own meteorite business. Some specimens have been bought. I no longer have control of all of my half of the find. Jason may have done the same. No one should be able to look at the photo listings on our website and say I have some stones that look like that I will call them paired with NWA 14370 because the location of our find is unknown. The ramifications if they do is to effectively change without evidence the Total Known Weight (TKW) of NWA 14370 from 3071 grams to who knows what weight and change the actual carefully and thoroughly collected number of stones from 45 to whatever. They cannot be visually paired to another stone because our find location is not known to anyone. A new classification needs to be gotten by someone with similar stones.

Is there more NWA 14370 to be found. Very likely but with no exact location data for our original 45 pieces that became NWA 14370 it should not become a victim of random and unjustifiable visual pairing. It’s an attractive meteorite. But it’s average unspectacular characteristics should not make it vulnerable to attack either. It should be able to sit in the Meteoritical Bulletin forever with no other meteorites ever attaching themselves parasitically to the classification.

The problem with some meteorites from my observations is that some are so generic in appearance that they are easy victims to visual pairing. Others are also so unusual that they become candidates for visual pairing. In the second case there may actually be justification for correct visual pairing. If the meteorite has characteristics never or rarely seen. Then another found or bought in the same region of the world may indeed be more of the original classification. But there still needs to be more than just the appearance to make that connection. Back to in situ and area photography of the second find along with who found it or from whom it was purchased. If it was purchased from the same hunter or dealer as the first and

Meteorite Times Magazine

they state it was found at the same location as the stone or batch used for the classification that should be enough information to allow a proper visual pairing. If the stones are identical looking. That is at least enough evidence in this writer’s opinion.

Would the original meteorite owner be upset. I guess that again depends on various sets of circumstances. Was he told at the time of purchase that it was the only stone and there were no more meteorites around to find. Then he might have reason to be upset with the seller if later more is properly visually paired to his classification. But if there were numerous stone as in many cases then the expectation that he had it all would be unrealistic. It should be no surprise when more is found and the weight and number of pieces in the Meteoritical Bulletin become all wonky forever. That seems to happen all the time. He has to take pride in the fact that he was the first to get it classified and that a piece of his stone is going to be the official type specimen. That’s all you get to hold on to sometimes.

Occasional you know as the finder of a meteorite that more will be found. At some point after you get it classified other hunters will go to the location. You have found one or more pieces and there has to be more. There will be no visual pairing statements in sales listings or with collection pictures. They will just be more of the same meteorite with the original name. When I found Old Dominion Mine, I knew there had to be more pieces. I suppose even after all these years and the other unsuccessful attempts that have been made more may still be found. No more has so far. If the location was not now considered dangerous by me, I would return to the area and try again myself. But I have a strong belief after some things that happened on the last trip that drug planes are landing there for its good secrecy and criminals are using the same access roads I have to use. So no more hunting there. But I also believe I might be able to hunt there and find more of the meteorite. My own finds if made of the meteorite could change the records in the Meteoritical Database on my own classification.

Is there a solution to any of this under current conditions of limited testing resources. No. Will the situation change so that most subsequent recoveries of meteorites can be laboratory paired. No. We have seen over the decades free classifications change to donation paid classifications, and now fewer available labs are doing only charged classification work based on the time and resources needed. Every meteorite classification is changed its own cost. I am fine with that. We are taking the time of valuable professionals who have research and other tasks like teaching to perform. They deserve to be paid. And there is nothing wrong with saying you are worth a lot for what you do. Even retired I find my rates going way up and my desire to share time and knowledge changing. I have come to realize I gave away my special knowledge and skills for far too little for years when I was working. I will close this by saying with some of the last part in mind. Saving the cost of getting a meteorite classified by saying it is the same as another based only on a similar appearance is not a good practice that we should see being done.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

These three Martian Shergottites look to me identical. Should another stone be called by one of their numbers? Again do you think you can pick out the true numbers of these three meteorites from an image? If none of us can then there is no protection for their individual names and designations other than honesty and doing things the correct way.

Spring is here and the desert is still a pleasant temperature, and the wildflowers are coming into bloom. I will be out hunting every few days and I wish the other hunters the same good luck I hope for myself. Find the big ones or a lot of little ones before it gets too hot. Stay safe.

Meteorite Times Magazine

SaU 562 Eucrite

John Kashuba

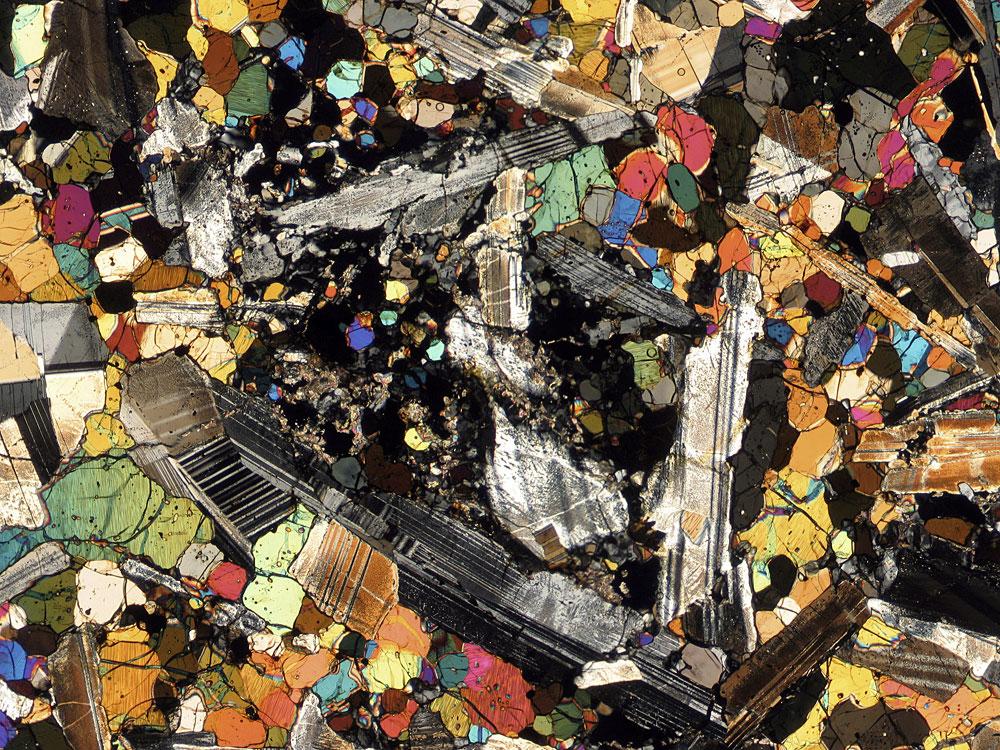

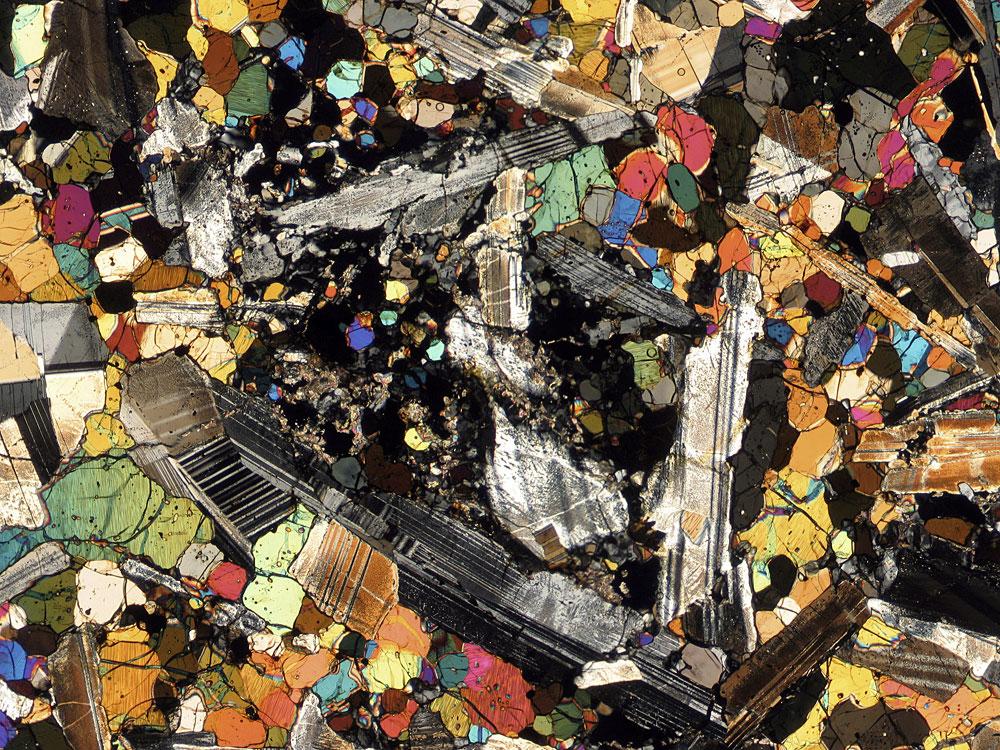

I first saw this material at “Ensisheim Météorite 2008.” Luc Labenne had come down from Paris for just the day and was blowing through the show really fast. He had a few thin sections, I had a homemade viewer to check them out and I bought a couple. It’s spectacular because of the relatively large mineral grains and it is not brecciated.

Later, we bought a slice from Luc and had this and other thin sections made. Early on it hadn’t acquired a name so we were calling it Labenne Eucrite.

Meteorite Times Magazine

This sample is 22 mm long. The white/gray is plagioclase feldspar. The brown is pigeonite pyroxene. Plane polarized light (PPL).

Meteorite Times Magazine

There are several shocked pockets with broken mineral grains and opaque minerals. We’ll look closer at one toward the top left. PPL.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Opaques and crushed pyroxene are surrounded by broken and crushed laths of feldspar. PPL. Field of view (FOV) is ~11 mm wide.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

Same view in cross polarized light (XPL). FOV~11mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Closer. PPL. FOV~6 mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Same close view. XPL. FOV~6 mm.

Other

Meteorite Times Magazine

views of this thin section. PPL. FOV= 3 mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

PPL. FOV= 3 mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

PPL. FOV= 3 mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

XPL. FOV= 3 mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

XPL. FOV= 3 mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

XPL. FOV= 0.5 mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

PPL. FOV= 0.3 mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

XPL. FOV= 0.4 mm.

Brenham, Kansas Meteorite Farm

Mitch Noda

Years ago, I had a conversation with a meteorite collector friend of mine. I mentioned the “Meteorite Farm,” and he did not know what I was talking about. I was surprised. I thought just about everyone knew about the “Meteorite Farm,” but I was wrong to assume this. Therefore, I am sharing with my friends the story about the “Meteorite Farm,” “Kansas Meteorite Farm,” “Brenham Meteorite Farm,” “Haviland Meteorite Farm,” or “Kimberly Farm” as the names some of you may recognize, and all of them refer to the same farm located in Haviland, Kansas in the Brenham Township of Kiowa County, USA.

I find it refreshing to read about a non-fiction story related to a famous historic meteorite whose main character is a strong woman who was ahead of her time.

In 1885, Frank Kimberly and his bride, Eliza, came to Kiowa County, Kansas , to exercise their rights under the Homestead Act to claim 160 acres of free land, as long as, they improved the plot by building a dwelling and cultivating the land. Frank was looking at Brenham (Haviland), and Greensburg for a plot of land for his farm. The Kimberly’s first home was a “dug-out” which was a large hole dug into the ground and covered with poles or lumber to support the soil which was piled on the roof. It was the most common home for homesteaders.

Frank planted corn and feed. Frank farmed the land and would occasionally come across unusually heavy black rocks scattered over the buffalo grass. No other stones were to be seen for miles around the treeless plain.

When the Kimberly’s came to the farm, Eliza immediately noticed the black rocks, and she was convinced they were meteorites. She would collect the “iron stones” and make a rock pile near the dug-out house. Frank and the neighbors would laugh at Eliza and her growing rock pile. Occasionally, Frank would plow into the rocks, and Eliza would add them to her growing rock pile.

Meteorite Times Magazine

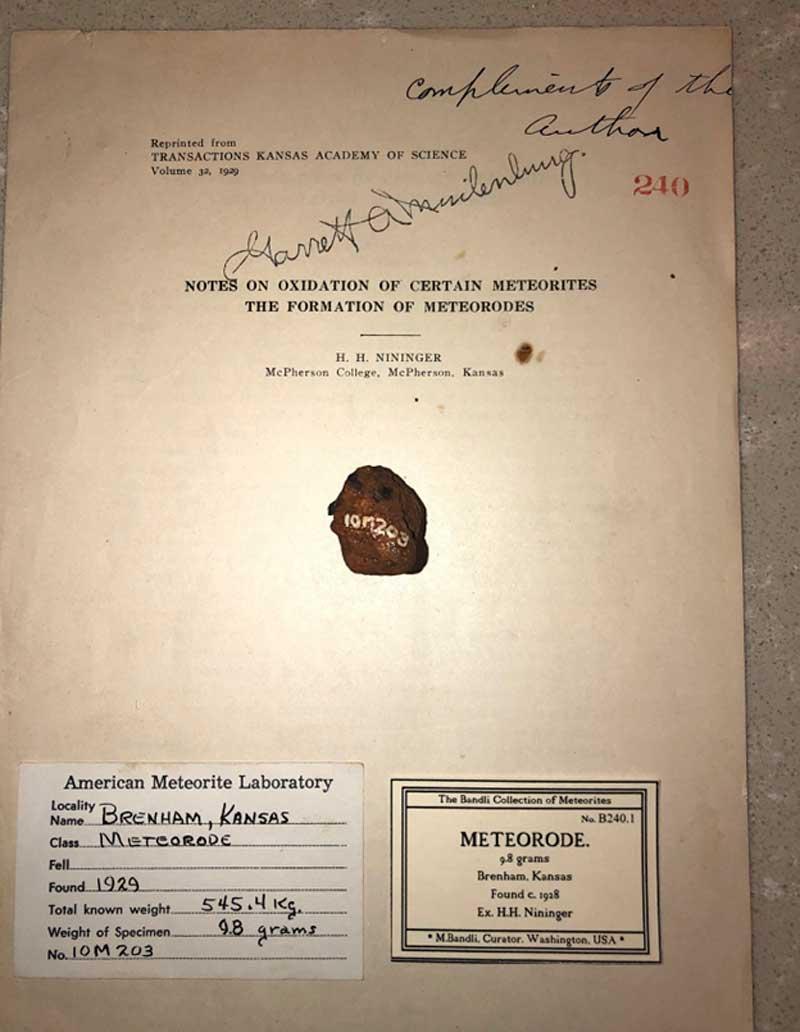

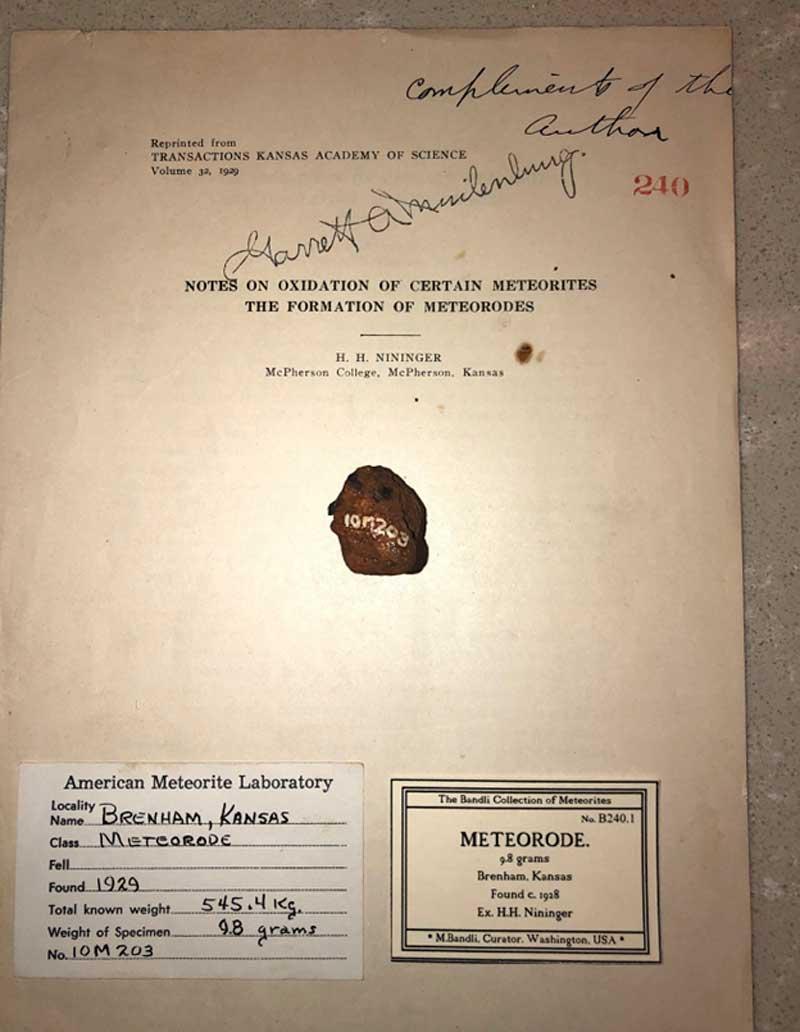

A thick 53 gram slice of Brenham with impeccable provenance, painted numbers, matching labels, and a rich history. This piece has it all.

Meteorite Times Magazine

I have not seen another Pallasite specimen with such documented provenance. Imagine the hands that touched this Pallasite – H. H. Nininger, Dolores Hill (University of Arizona), Mike Farmer, Eliza Kimberly? Nininger bought a few specimens from Eliza and Frank Kimberly.

One day, Eliza brought Frank lunch and noticed a particularly large specimen weighing approximately hundred and fifty pounds Frank dug out of the ground. They loaded it onto the wagon, but Frank was becoming increasingly annoyed with his wife’s crazy fantasy, and dumped it out into the fields instead of adding it to the rock pile.

Many times, the rocks were a point of contention between Frank and Eliza. Frank thought Eliza could spend more time with chores around the farm instead of spending time moving worthless rocks. Disregarding his criticism, she continued adding to her collection pile.

Eliza was so convinced that her rock collection were meteorites that she wrote to everyone she

Meteorite Times Magazine

knew who had knowledge of geology asking them to examine her rocks. After a long five years, she convinced Dr. F.W. Gragen, a Harvard trained geologist who taught at Washburn (Kansas) college, to come inspect her rocks. He wrote that he would come examine her rock collection.

Frank and his neighbor son-in-law, Jud, looked forward to Gragen’s visit as a break from work, and they felt the professor would inform Eliza that she had been breaking her back to gather a bunch of worthless rocks. The two men knew little about science and less about the “meters” that Eliza had been saving.

On 13 March 1890, Dr. Gragen visited the farm. Mary, the Kimberly’s daughter and her husband Jud Evan were neighbors and came over for Dr. Gragen’s visit. Frank and Jud speculated about the professor’s reaction when seeing the pile of rusty stones. Frank was hopeful that Dr. Gragen would pay even a small amount and remove the nuisance from their yard. Frank thought this may finally convince his wife to stop with her obsession of collecting worthless rocks and spend more time with important chores.

Eliza wanted her entire collection to be available for Dr. Gragen’s inspection, and she had more than twenty specimens lying in the yard near the house which included a seventy pound rock that had been holding down the cover on a rain barrel that she carried to the yard. The prize in Eliza’s collection was a 466 pound stone. It was nicknamed the “moon rock.” Frank cursed when he found it because it broke his plow and gave him some bruised ribs when he ran into the plow as it suddenly stopped after hitting the large stone. Frank and his son-in-law Jud brought it to the yard using horses and a tow chain.

When the professor arrived, he brought from his buggy a bag with tools. Dr Gragen took out a chipping hammer and magnifying glass from his bag. The chipping hammer was used and an examination of the opening it created was done. The professor took a long time examining the “moon rock.”

After a pause, Dr. Gragen informed the group that Eliza’s rocks were meteorites. Eliza proclaimed, “I knew it!” He tried to bargain and purchase all of them. Dr. Gragen’s offer was so astonishing and generous that Frank wanted to accept the offer right away. The Kimberly’s were barely eking out a living at their homestead. Eliza was overjoyed with the offer and glanced at Frank, and proceeded to tell Dr. Gragen, “no.” Frank’s heart sank.

The family had a private meeting and returned to discuss the value of the meteorites, but the professor held firm to his first offer telling them that is all the money that he had. Eliza countered that Dr. Gragen could select five of the masses from her collection of twenty, and he agreed. Eliza being a shrewd negotiator received several hundred dollars for a little more than half of Eliza’s collection that weighed about a ton. It was enough money for the Kimberly’s to pay off their mortgage and buy a neighboring farm from which they found more meteorites to sell. They also shared a portion of the money with their neighboring daughter and son-in-law - Mary and Jud Evans.

The next day, after Frank delivered Dr. Gragen’s specimens to the railroad station, the Kimberly’s were visited by Professor Robert Hay who was a teacher and scientist educated at the College of London and also worked for the U.S. Geological Survey as a geologist. Professor Hay made more than one visit mapping out where many of the masses were found. It is unknown if he purchased any meteorites.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Three days after Professor Hay’s visit, Professor Francis Huntington Snow, scientist and Chancellor of Kansas University visited the farm and purchased a 101.5 pound specimen which was earlier purchased by Frank from a cowboy. According to the Kansas City Star, Frank purchased the rock from a cowboy for three dollars and sold it for $150. According to the newspaper, the sale of meteorites helped the Kimberly’s save the farm from foreclosure since it was heavily mortgaged.

Eliza’s five years of collecting “iron stones” culminated in tremendous activity. Farm work became secondary to this unexpected business of reaping money that had fallen from the sky. Frank took up the cause enthusiastically and would go about the neighborhood offering to buy up the “iron stones.” He was not as discerning as Eliza and sometimes paid for a huge hunk of slag. He went back to his field to search in vain for the 150 pound meteorite he dumped from the wagon. Frank searched again and again for the specimen but without success.

Dr. Gragen and Dr. Snow sold part of their haul to Dr. George F. Kunz, who would go on to become vice-president and chief gemologist at Tiffany and Co. Dr. Kunz obtained eight masses which he resold to other scientists, universities, and museums. (Read my Meteorite Times article on George F. Kunz and Tiffany’s for more information on a fascinating man.) Three months after Dr. Gragen’s discovery, an article written by Dr. Kunz appeared in Science on June 13, 1890 providing a comprehensive history of the Brenham meteorite.

After the Kimberly’s sold a ton and a half of meteorites, for years they could find no more buyers. In 1923, Nininger, with borrowed money, purchased a couple of large specimens the Kimberly’s could not market. Nininger wrote, “These specimens from the “meteorite farm” made a substantial addition to my young collection and were a substantial help to my thin bank roll when I made resales of parts of them. In 1927 I purchased a mass weighing 465 pounds, turned up by a plow boy. Ultimately I added a half ton of Brenham to my collection before the supply seemed to be exhausted.”

Meteorite Times Magazine

From my library, H. H. Nininger’s, “Notes on Oxidation of Certain Meteorites” “The Formation of Meteorodes” On the cover at the top right corner, in Nininger’s hand, “Compliments of the Author” A 9.8 gram meteorode with painted number and matching AML label.

In 1929, when Nininger was visiting Frank and Eliza, he found out about a “buffalo wallow” where Frank discovered a sixty-eight pounder. Eliza chimed in that she had found a bushel of those real small ones around the wallow, but not in the hole. Nininger asked Frank to show him the “buffalo wallow.” Frank showed Nininger the shallow depression about forty feet across with a rim around the edge. Frank said, it was a lot deeper but that he filled it during planting season. Nininger recognized it immediately as a meteor crater.

Nininger received permission to dig near where Frank found the sixty-eight pounder on the edge of the rim. He encountered small, potato sized, rusty brown nodules which when broken

Meteorite Times Magazine

exposed inside of them rounded olivine crystals. Except for the olivine crystals, the round rust color lumps bore no resemblance to the meteorites the Kimberly’s found. Nininger coined the phrase “meteorode” to describe these oxidized meteorite lumps. Frank was never able to sell any of these lumps, so he was not too interested in the wallow. Nininger was interested in excavating into the wallow, but Frank insisted on doing any excavating. Nininger was more interested in the structure of the crater, and did not want Frank to destroy the crater, so he did not push the issue. Nininger mused, “I conceived that these oxidized forms with their shell of oxides containing remnants of a true pallasite might be scientifically more valuable than unoxidized specimens.”

My 26.7 gram meterode specimen with hand painted number and matching American Meteorite Laboratory label.

Around May of 1933, Nininger returned to the Haviland crater. Frank passed away on 14th December 1932 at the age of 85, and Eliza passed away 1st April 1933 at the age of 84. Both were gone when Nininger visited and a new generation of Kimberly’s gave him permission to excavate the buffalo wallow. Nininger was expecting to find a meteorite weighing about a ton,

Meteorite Times Magazine

however, he was disappointed to find the largest meteorite was eighty-five pounds even though they found in total 1,200 pounds of meteorites and Meteorodes.

A decent sized 50.1 gram meteorode from ASU’s collection and accompanying Aerolite Meteorites label. Geoff Notkin of TV “Meteorite Men” fame signed the label certifying the meteorode’s authenticity and ASU provenance. The label could be considered a collector’s item since Geoff doesn’t sign most of the Aerolite labels. Also pictured is the matching ASU label.

The Meteorite Farm was acquired in 1940 by Charles J. Harmon from the Kimberly heirs, then

Meteorite Times Magazine

in 1946 was acquired by Ellis L. Peck who wrote “Space Rocks and Buffalo Grass” a wonderful book about the famous meteorite farm. It is my favorite writing about the farm. Ellis and H.O. Stockwell struck up an agreement for Stockwell to search the Meteorite Farm for meteorites. Stockwell found a 1,000 pound Brenham meteorite on the property and paid $1,000 to Ellis. That 1,000 pound rock is still in Greensburg, Kansas.

In 1993, Ellis Peck passed away and his farm went up for sale in auction in 1994. My friend Don Stimpson and his wife Sheila Knepper purchased the meteorite farm. Prior to purchasing the farm in 1991, Don and Sheila came searching for meteorites around the farm during their vacation from Chicago. Their first Brenham finds were a few grams to baseball size using a metal detector based on the Stockwell design.

After purchasing the farm, Don found another crater out on the farm that was more compact than the one Nininger found, but had a larger amount of material, over 1,500 pounds of meteorites and Meteorodes. He tried to get a paper published about his discovery, but the science journal declined.

My friend Don Stimpson wrote and signed the card attesting to his finding the accompanying

Meteorite Times Magazine

metorode on the Meteorite Farm that he and his wife, Sheila purchased in 1994. They were well aware of the Meteorite Farm history and specifically bought the farm for the meteorites located on it, and its marvelous history.

Around 1996, Don and Sheila opened the first meteorite museum in the old school house in Haviland. They planned to open a second museum in Greensburg in 2008 in a corner building owned by Mayor McCullough, but a tornado changed everything. They built their own building to get the meteorite museum started. Don and Sheila came to Kansas to start a meteorite museum with the goal of making a new tourist attraction that would be self-sustaining. They wanted to call attention to a very unique site in this country. Unfortunately, they did not make the selfsustaining goal, and the museum closed when Don reached retirement age.

You can watch YouTube videos and live vicariously through Don as he locates and excavates Brenham meteorites that weigh hundreds of pounds to 1,100 pounds on his meteorite farm. He uses a large metal detector set-up he created and drags behind his truck to locate the meteorites.

Don and Sheila certainly channel the spirit of Eliza and Frank - the original owners of the meteorite farm.

References:

1) Ellis L. Peck, former owner of the “Meteorite Farm,” book “Space Rocks and Buffalo Grass”

2) H.H. Nininger’s book “Find A Falling Star”

3) Wikipedia – Brenham (meteorite)

4) Don Stimpson, current owner of the “Meteorite Farm,” emails to Mitch Noda

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Sponsors

Paul Harris

Please support Meteorite-Times by visiting our sponsors websites.

Dog Meteorites

The Meteorite Exchange, Inc.

Impactika

Rocks From Heaven

Tucson Meteorites

MSG Meteorites

KD Meteorites

Meteorite Times Magazine

Nakhla

Once a few decades ago this opening was a framed window in the wall of H. H. Nininger's Home and Museum building. From this window he must have many times pondered the mysteries of Meteor Crater seen in the distance.

Photo by © 2010 James Tobin