Time in the Hi s

Celebrating 75 years of connecting people to the land

Merck Forest holds traces of what came before. You can see it in the hand-hewn timbers of the Sap House, in the contours of old pastures returning to forest, and in the worn footpaths where generations have walked.

You can feel it in the rhythm of lambing season, the slow growth of the sugarbush, the way a child’s wonder echoes that of a parent decades before.

Time in the Hills is a special edition marking 75 years since the Vermont Forest and Farm Land Foundation first began welcoming people to learn from and care for this land. These pages are filled with the voices of people who were shaped by Merck Forest, and who will continue to shape it for the next 75 years.

This landscape we love will continue to evolve and shift in response to climate change, our work, and intentions. It’s a living, working, learning place, alive with the rhythms of land and people.

What endures is the care behind it: a deep-rooted commitment to stewardship, to teaching, to community, and to multi-generational thinking.

Thanks for being part of that. The work continues.

PAST

From Indigenous stewardship to modern conservation, this land holds a story of transformation.

1960s

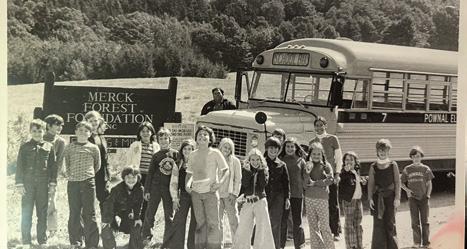

The name “Merck Forest & Farmland Center” is adopted. A network of roads and trails is constructed, and infrastructure is added to welcome the public. In 1967, the first Student Conservation Association (SCA) crew, two leaders and eight high schoolers, arrived to support forest and farm work. Hundreds more will follow in their footsteps.

1980s

The SCA continues to play a major role as MFFC expands its educational offerings and deepens its commitment to sustainable practices.

• A network of cabins invites immersive visitor experiences.

• 30+ miles of trails draw hikers, skiers, and riders across seasons.

• Maple sugaring becomes both an educational tool and a source of income.

• A new Visitor Center and farm expansions showcase sustainability in action.

1940

George Merck’s assistant, Elizabeth Kelly, discovers Wind Gap Farm on Rupert Mountain and recommends it as a family retreat. She describes it as “a wonderful piece of farmland with a beautiful view.” George agrees and purchases the property.

1950s

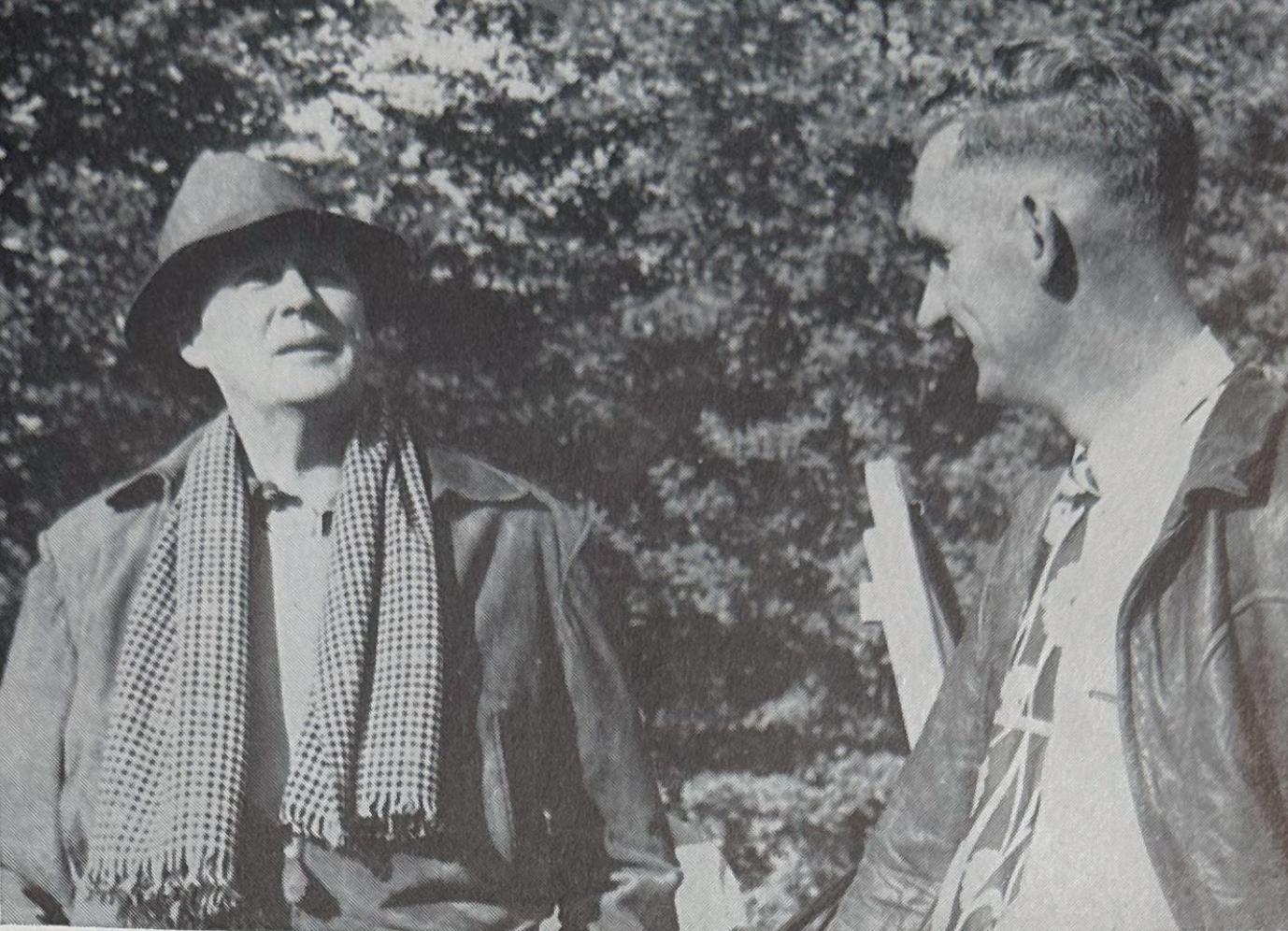

The Vermont Forest and Farm Land Foundation is established, anchored by the Harwood, Young, and Sheldon Farms. George Merck donates 2,600 acres to form the Vermont Forest and Farm Land Foundation, Vermont’s first ecological foundation. With guidance from pioneering forester Dr. Carl Schenck, Merck Forest’s early land management is grounded in restoration, science, and public benefit.

1970s

MFFC incorporates as a nonprofit, centering on sustainable forestry, agriculture, and education. In 1972, MFFC and Mt. Rainier host the first youth corps crews to include young women—a milestone for women in conservation. By 1977, Dunc’s Cabin is built, and the first sugaring season begins with 150 tapped lines and 350 sap buckets, hand-collected and hauled in by draft horses.

1986

Cut Your Own Christmas Trees with sleigh rides led by Belgian draft horses Mollie and Charlie up to the tree plantation, and hot cider for visitors back at the caretaker’s cottage upon return.

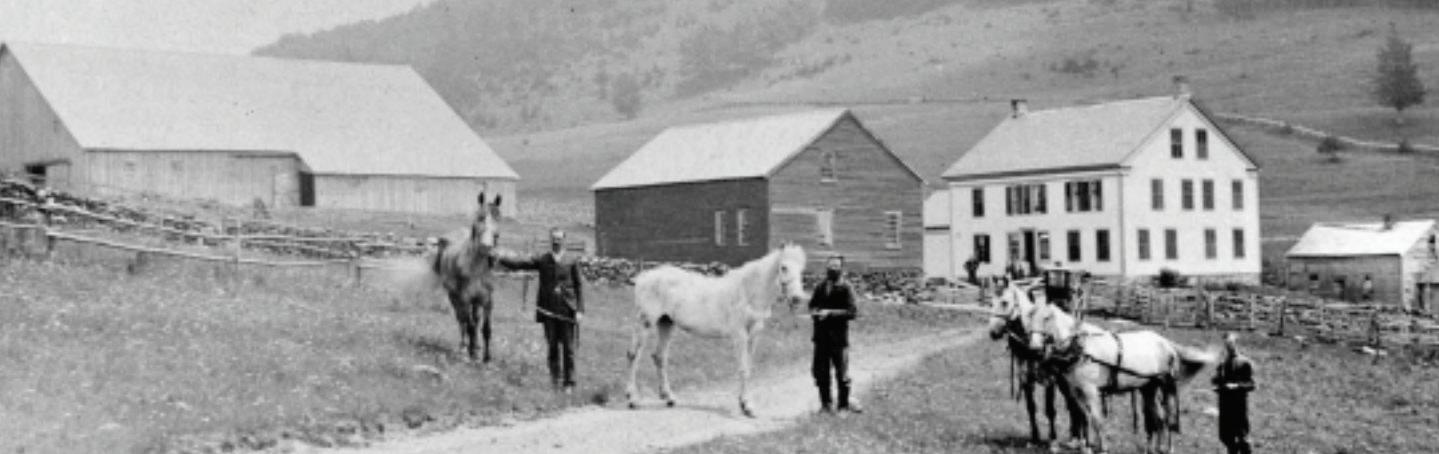

By the 1850’s, nearly two thirds of the land that is now Merck Forest was cleared for pasture and hay, and hundreds of sheep roamed the mountainsides. Only the very tops of the mountains remained forested. After the 1850’s the demand for sheep dropped and much of the land eventually began to revert to forest. Butter, cheese, and potatoes became the main crops through the 1900’s. Over time all but one of the farms gradually failed and were abandoned. The last operating farm, was the Harwood farm that operated in the 1940s. In 1950 that became Merck Forest.

-Ecologist Charles V. Cogbill

In the 1940s, George Merck began acquiring land in Rupert, Vermont, working with forestry pioneer Carl Schenck to restore a once-deforested landscape. By 1950, the Merck family had donated 2,600 acres to establish the Vermont Forest and Farmland Foundationwhat is now Merck Forest & Farmland Center.

Today, the property spans 3,500 acres, with 3,200 acres permanently conserved.

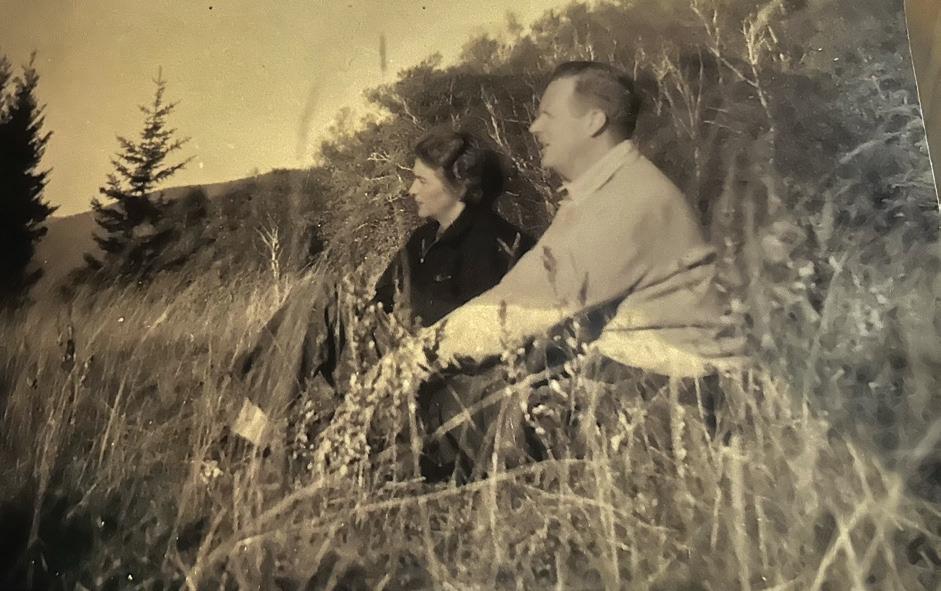

Clockwise top left: A view from the lodge. VFFF is the Vermont Forest and Farmland Foundation. Standing at the lodge today, the view is blocked by forest; Founder George W. Merck with John C. Page, Bennington County Agent; Buechners with George Merck in October of 1956; Executive Director Bill Meyer talks over with Bulldozer Operator Vernon Beebe of Rupert plans for extending one of VFFF roads; Annual meeting of the VFFF in 1953. R to L: Page, Meyer, Mitiguy, Buechner, McCormick, Kouwenhouen, Merck.

Frank Hatch Stories

(From Jane Beck interview - June 26, 2001)

Reminisces from Frank Hatch, George Merck’s son-in-law, and one of the founding members of the board of Merck Forest & Farmland Center.

The two closest friends George Merck had were Gene Tunney, the boxer, and John Marquand. And on one hot July weekend, with the temperature very much as it is today, the three of them were having lunch. And in those days, they would have a martini or two before lunch.

And so you would sit at the dining room table--and Burton Blackmer, the then farmer on the place, would come in and say, “Mr. Merck, what would you like me to do today?” And Uncle George said, “Well, today, Mr. Buechner, Mr. Tunney, and I, are gonna improve the hedgerow along the Foundation field. If you’d bring up some axes, we’ll be up there after lunch.”

And so they went up there on this hot day. Burton Blackmer was a very resourceful man, and he knew all about Gene Tunney. And so he had an axe by a tree for Buechner and said, “Here, you take that tree. And then here’s yours, Mr. Merck. And then here’s yours, Gene Tunney.”

Tunney was an American boxer who competed from 1915 to 1928 and held the world heavyweight title (1926–1928) and the American light heavyweight title (1922–1923).

Well, Buechner and Uncle George had normal maples or even softer woods. But he gave Tunney a huge, hard hack. And so Gene Tunney got hotter and hotter, and he swung harder and harder with the axe, and by then they realized what the farmer had done and they all got laughing. Tunney finally hit the tree so hard with the axe that he shattered the handle.

Burton Blackmer’s successor, Vernon Beebe--he was a wonderful man--he used a little bulldozer on the property that George Merck bought for the Foundation. He built most all the original roads around the Foundation, the ponds and everything else.

We wanted a pond-- this was after Uncle George died--and we wanted a pond up, more remote, with the campsite. And it’s up in the Wade Lot and we named it the Beebe Pond.

And I remember coming up one day and as I walked into the forest, and Vernon happened to be there and he saw a man coming down and he said, “Well,” he said, “where you been?” “Well, we’ve been up at a cabin up--I think it’s called Beebe Pond.” “Well, did you catch a trout?”

“There aren’t any trout there.”

“Yes, there are,” said Vernon. “No, there aren’t,” said the man. “Yes, there are!” And finally, the man said, “Well, how do you know?” He said, “I put ‘em there!” That ended that one.

Vernon had such a penchant for building roads and ponds that when he heard we had hired this man with a very big bulldozer to build a pond, Vernon got up at five o’clock in the morning on his little slow bulldozer and he went all the way up over by Mt. Antone, down the side, and he got there, to the site, about an hour before Bob Slater, the man with the big bulldozer from Salem, arrived. Slater had done all the sitings. And Vernon had started to dig that pond too far up the valley and there was nothing you could do to turn it around, so we now have two ponds because Vernon came over early.

The laughter, labor, and love in these stories still echo across the ridgeline. Today, Merck Forest carries forward the legacy that George Merck began, stewarding the land in ways that connect people, protect biodiversity, and shape a resilient future. Support the next 75 years.

Built Into the Beams: A Forest Manager’s Legacy

As told by Sam Schneski

My time at Merck Forest has shaped my life in many ways. I worked there and loved it, found my wife, found a career, I got stronger in skills that I wanted to build: being a forester, being a sugarmaker, teaching folks through hands-on experience, working in the woods. My life’s trajectory was forged in those fields and forests.

I met my future wife at MFFC. Laurie Snyder was the Farm Manager from 1998 to 2003. She’s a veterinarian now in Brattleboro.

Ken Smith hired me as Forest Manager in 1999 and I helped build the Frank Hatch Sap House.

I cut the logs from MFFC property and hauled them down to Jim Ross’s mill in Pawlet. Ray Pratt and I and a couple of MFFC interns started building the sugar house in a sub-zero winter. It was 15 below almost every day, with Merck mountain world-class winds. There was one day - we were working hard - it got warm so we took our jackets and gloves off, and Laurie looked at the thermometer on the small animal barn, and she said, “Guys, it’s eight degrees outside”.

If you take a look inside the sap house, you’ll see almost every post in that room is a different species - I thought it could be a way for someone to learn what different tree species look like when they are milled into lumber.

I took a wood burner and burned my name into one of the beams--”Schneski.” I left little notes too - stashed in the roof and nooks and crannies - recording the date, weather and the temperature. Someone will find them one day.

What’s in the Walls

“Every post in that room is a different species. I thought it could be a way for someone to learn what different tree species look like when they are milled into lumber”

- Sam Schneski

Red Maple (Acer rubrum) Red maples grow in swamps, on dry ridges, and everything in between. Their nickname is America’s tree and their twigs taste sweet to moose!

Yellow Birch (Betula alleghaniensis) The yellow birch gets its name from its shiny, curling, golden bark. If you scratch the wood, it smells like wintergreen, and its twigs taste minty. (It contains methyl salicylate, the same compound found in old-fashioned root beer.)

Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) Its bark is sometimes called “burnt cornflakes” because of its dark, flaky look. The tree’s fruit feeds birds, mammals, and insects, but its leaves can be toxic to livestock when wilted.

White Ash (Fraxinus americana) This tree produces strong, resilient wood traditionally used for baseball bats, though its future is threatened by the invasive emerald ash borer, which has a foothold in Vermont and elsewhere.

“I stashed little notes in the rafters—someday, somebody will find them.”

- Sam Schneski

Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum) It takes about 40 gallons of sap to make one gallon of syrup. Merck Forest has a 2200-tap sugarbush. Sugar maples are also showstoppers in fall with their brilliant orange and red leaves.

Norway Spruce (Picea abies) Though native to Europe, this tree has naturalized here, and it’s the species most often chosen for Christmas tree displays, including the famous Rockefeller Center tree in NYC!

Larch / Tamarack (Larix laricina) Larches are deciduous conifers, meaning they have needles that turn golden and fall off in autumn! They look like evergreens but act like maples in fall.

Red Oak (Quercus rubra) Red oaks grow tall and fast, reaching over 90 feet, and some exceptionally old specimens live up to 500 years. They also have fiery foliage in the fall.

Scan here to listen to a clip from Sam’s interview inside the Sap House!

Clockwise top left: Sam Schneski in front of the logs he and Ray Pratt will use to build the sap house. Faint remains of Sam’s name burned into the beam. Building the roof. The interior of the Frank Hatch Sap House showing the various species of wood used in its construction. Snow inside the sap house as they prepare for the installation of the evaporator.

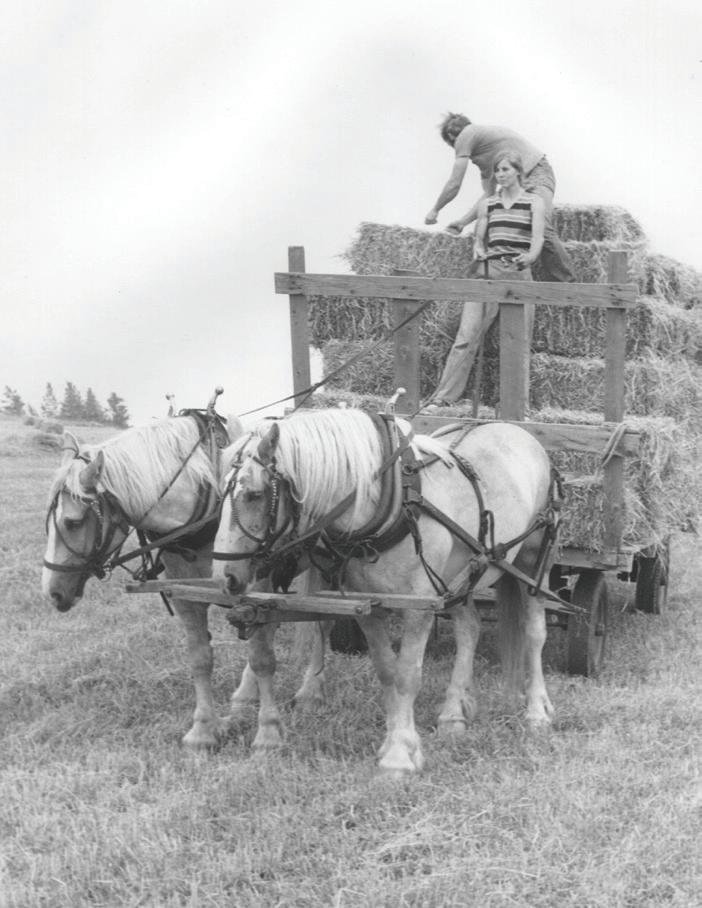

Clockwise top right, left hand page: 1850’s Harwood barn from a distance; Wild turkeys roaming; Building the first sugar house (now Dunc’s cabin); 2001 was the year of the 36-hour boil, making over 400 gallons of fancy grade maple syrup; Karen Noyce building the caretaker’s cottage; Much of the work in the early days was done with the help of Mollie and Charlie two Belgian Draft horses; Ed Reading, Duncan Campbell, and Ellen Scott with the two evaporators in the sugar house.

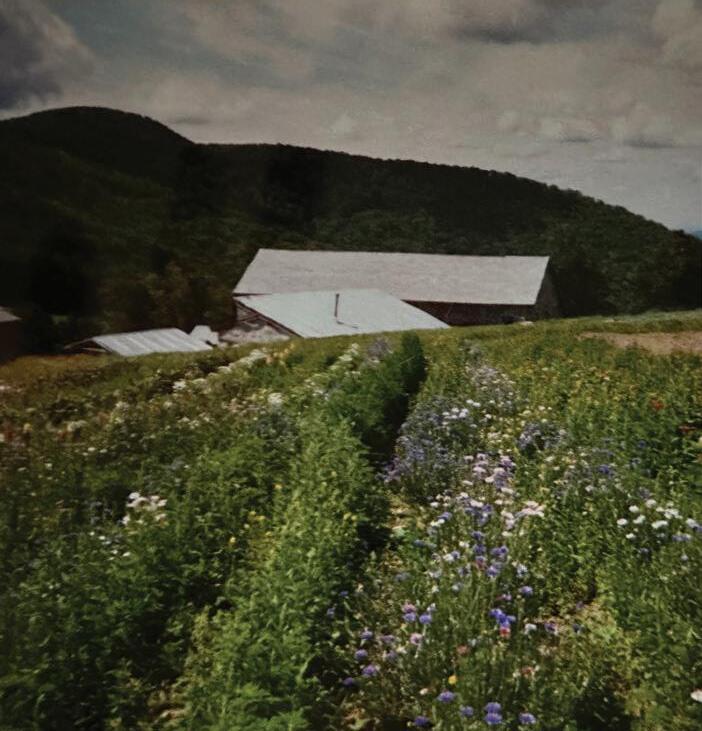

Clockwise top left, right hand page: Winter study group; Laurie (Snyder) Schneski feeding the guard llama. This animal protected the sheep in 1998; L to R: Ben Winship, Caroline Herter, Ed Reading, and Duncan Campbell; Flowers grown in the fields; Jaimy George, Laurie (Snyder) Schneski, Melissa Pline, and Christina Cosgrove showing arrangements they made in a workshop from the flowers they grew in the picture to the right, 2001; Ed Reading collecting sap buckets with Mollie and Charlie, draft horses; Much of the work in the early days was done with the help of Mollie and Charlie; Sam Schneski (forest manager) teaching interns Joe Dunlap and others the Game of Logging method of safely felling a tree in 2001.

PRESENT 2000s 2020 2021 TODAY 2025

The Welcome kiosk at the entrance is erected, and solar panels are installed at the Frank Hatch Sap House.

As the 21st century begins, MFFC begins exploring permanent conservation. In partnership with Vermont Land Trust, the process culminated between 2015 and 2018, protecting 3,200 of Merck’s 3,500 acres in perpetuity.

• Merck pilots its first bilingual field trip curriculum to better serve Spanish-speaking ESL students in the BenningtonRutland Supervisory Union.

• Little Sprouts, a new naturebased morning drop-off program for children ages 3–5, is introduced to connect the youngest learners to the land.

With support from the Vermont Land Trust, MFFC acquires 144 acres next to Mettawee Community School to create a satellite campus for its K–6 students and co-develop outdoor programs, teacher trainings, and trails - engaging students in both design and stewardship.

Merck Forest & Farmland Center welcomes thousands of visitors annually (20K in 2024), including students, families, solo hikers, educators, researchers, and community members. With its working farm, research partnerships, trail system, and diverse educational programs, it remains a living classroom and a vital ecological refuge.

A Pathway Through the Present

By Rob Terry, Executive Director

There’s only one place in the known universe where rain falls, rivers run, trees breathe, and creatures, from barred owls to humans, move through a shared, living story.

That place is here. Earth.

At Merck Forest & Farmland Center, we stand at the pinch point of one of its most important passages.

As we write this, at the midpoint of our 75th anniversary, the air continues to warm year over year. Every living species has what scientists call an envelope, a delicate set of conditions it needs to survive. As climate change pushes temperatures and humidity beyond those boundaries, species are responding the only way they can: by moving. Up in elevation. North in latitude. Toward somewhere that still feels like home.

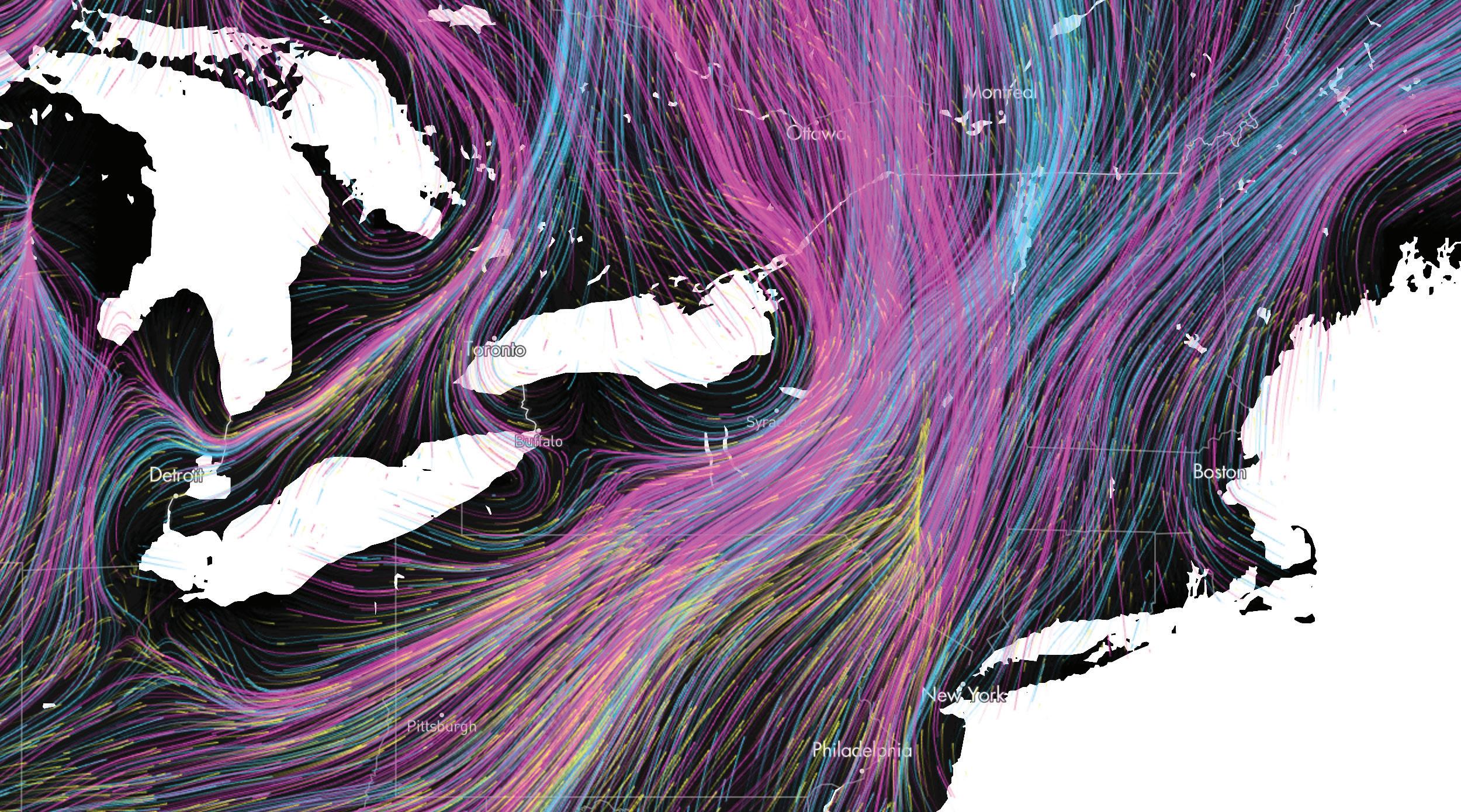

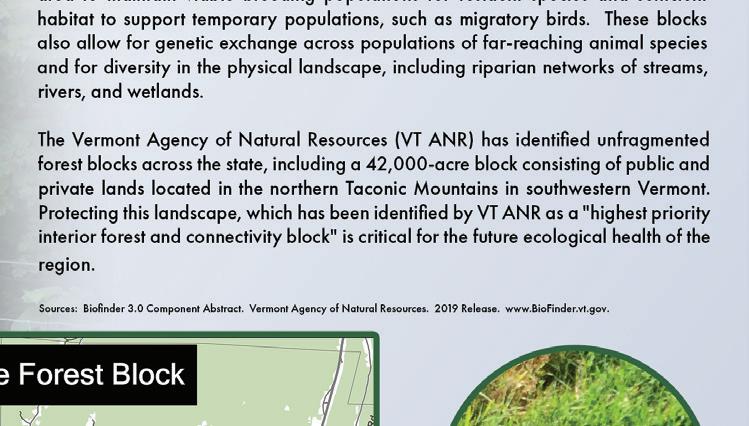

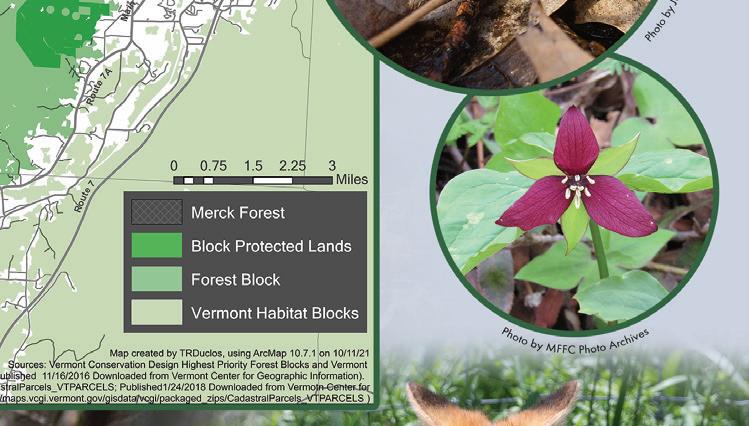

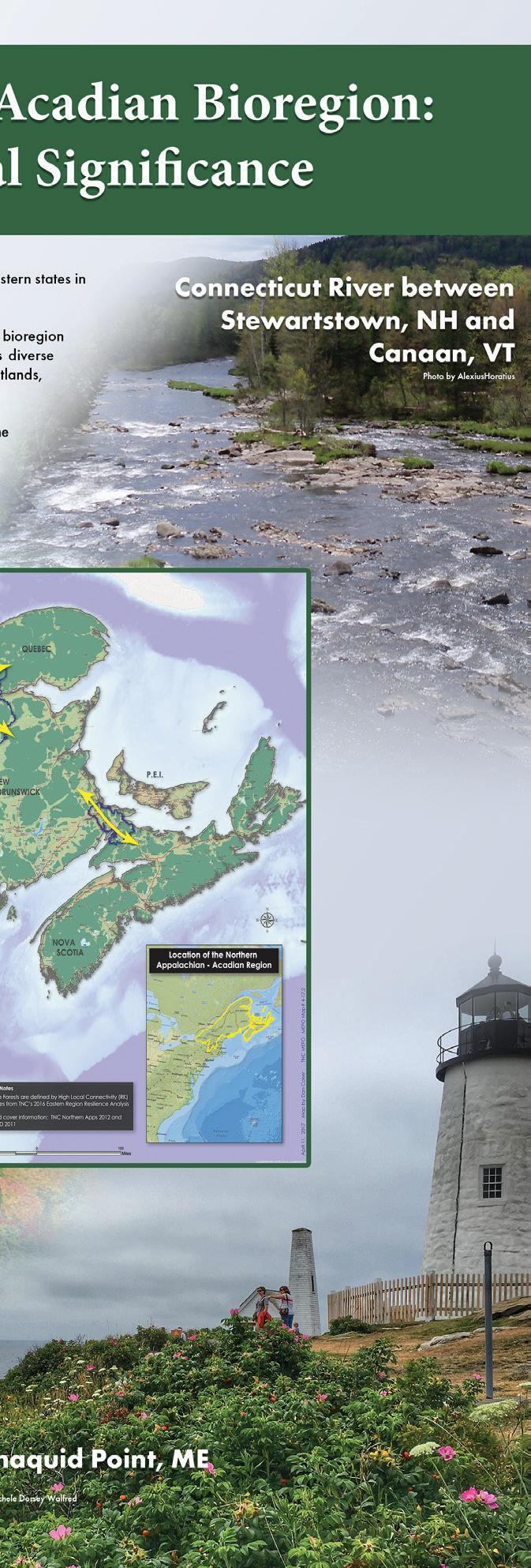

This migration is already underway. Birds, mammals, amphibians, and insects — creatures from as far south as Texas and Florida— are traveling along a vast ecological corridor that threads its way up the Appalachian Mountains, narrowing here in the northern Taconic range before widening again into the boreal forests of Canada.

This corridor is vital. And Merck Forest sits squarely in its most vulnerable pinch point.

This reality shapes our work at MFFC: We are stewards of a beautiful place and caretakers of a vital passageway. This land, these forests, these trails are not only for us. They are for the future of life itself.

A 100-year-old sugar maple, vibrant green moss soft between its roots, grows beside a stone wall. Overhead, warblers flash through the canopy. Ants ferry soil in tiny arcs. The forest is alive in ways we can see, and in ways we cannot.

Merck Forest is part of a larger landscape known as the Northern AppalachianAcadian Ecoregion - the largest intact temperate broadleaf forest on Earth. It filters our air and water, stores carbon, and offers refuge for the astonishing diversity of life on this planet.

We welcome you to the “Present” of Merck Forest. The past teaches us what once was. The possible points toward what may be. But the present is where we humbly make decisions, the impact of which we may not see in our lifetime.

As robust and healthy as it may seem to our 20,000 annual visitors, it is fragile. It was subject to a mass clear-cutting, resulting in forest cover dropping from over 90% to less than 30% in just a few generations after European settlement, and it is still recovering.

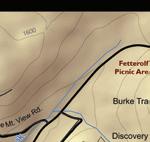

Where will the wildlife go as the climate changes?

This map traces the paths birds, mammals, and amphibians may follow in search of suitable conditions.

Merck Forest’s 3,500 protected acres connect directly to a 42,000-acre unfragmented forest block, which contains interior habitat that many species depend on. Forest fragmentation creates “edge habitat,” unsuitable for the majority of species. Every driveway, house, or road slices the land further apart.

And yet here, because of the steep terrain, the old geology, the inaccessibility, and, more recently, the intention, the forest remains largely unbroken.

We manage the land actively and sustainably. That means we tend to the woods to improve habitat, reduce stress on the land, teach visitors, harvest modest yields of timber, and more.

Our farm shares this same ethic. By practicing rotational grazing and avoiding chemical inputs, the soil stays intact. The watershed at the top of Merck Forest, which feeds both the Hudson and the St. Lawrence, is protected. Our trees absorb and filter water along the way. These headwater forests reduce flood risk and improve water quality for downstream neighbors as far away as Manhattan and Montreal.

From the birdsong before dawn to the stillness after dark, this place pulses with life. And if you spend a day here, you can feel the rhythm of a landscape still in balance, even as it reflects the effects of climate change, environmental stressors, and attempts at recovery.

We welcome you to the “Present” of Merck Forest. The past teaches us what once was. The possible points toward what may be. But the present is where we humbly make decisions, the impact of which we may not see in our lifetime. This is where change begins, where care becomes action.

We believe that this forest, and places like it, may hold answers. Not likely quick or easy ones. But enduring ones. Here, children crouch to watch frogs. Students help clear trails. Interns build fence lines and carry sap buckets. Researchers examine canopies and record leaf-out timing. We learn daily what it means to live in harmony with the land. You may have come to MFFC for the view, to hike a trail, to stay in a cabin, or for the quiet. You may not have known that this is one of the Earth’s vital passageways. We invite you to return, or to come for the first time. Walk the trail that runs from the farm to the lookout. Listen for the Hermit Thrush. Feel the air shift as you step beneath our sugar maples. This land is a place to protect today. Welcome to the present.

One Week in May: Life at Merck Forest & Farmland Center

In the span of just five days, Merck Forest & Farmland Center welcomed more than 300 people through its farmyard, fields, and forest. The week following Memorial Day was a condensed one, but the pace didn’t slow. From preschoolers in the forest to college students at backcountry shelters, the land hosted a full spectrum of educational programming. This one week offers a clear snapshot of how MFFC lives out its mission every day.

TUESDAY the Williams College Outing Club launched the week with a two-night stay at the Glen and Beebe Pond shelters. Seventy-five student leaders attended a training session to learn to lead orientation trips for incoming first-year students in the fall of 2025. It was their largest training session to date at MFFC, and many had never been on campus before.

Kits & Cubs, MFFC’s weekly forest school for toddlers and their caregivers, ran as scheduled on WEDNESDAY AND FRIDAY. That brought 13 adults and 14 children to the mountain for hands-on, play-based learning in the woods.

On WEDNESDAY, the Berkshire Taconic Regional Conservation Partnership convened a regional meeting at Merck Forest, drawing nearly 40 professionals for a collaborative session focused on land use and conservation in the region.

THURSDAY’S activity stretched well beyond campus. Rob Terry, Executive Director, traveled to Montpelier to participate in a Forest Health Integrity meeting alongside 17 other practitioners from across the state. Meanwhile, back at MFFC, the Maple Street School held its annual Mountain Day. Nearly 60 students rotated through mini-classes in animal tracking, garden work, vernal pool ecology, and nature journaling.

Hear John Schneble, Director of Program, share more about MFFC’s programs.

FRIDAY opened with a visit from Saratoga Independent School’s 7th-grade class, who had stayed overnight in the Barn Cabins. Students came down to the farm for a tour and helped with trail and site work around the Caretakers Cabin as part of their service project.

Later that afternoon, 32 second graders from Manchester Elementary & Middle School arrived for a Farm Connections field trip. The timing was perfect as they joined staff for the ram turnout, watching (and helping with) the process of introducing breeding males to the flock.

Also on FRIDAY, MFFC co-hosted a statewide Climate and Forestry event with the Vermont Woodlands Association. Twenty professionals from across Vermont gathered to discuss forest-based climate solutions and land management practices.

The week concluded with a SATURDAY afternoon lecture by ornithologist and Pulitzer Prize finalist author Scott Weidensaul, held in the Sap House. Despite wind and rain, 45 people turned out for the event to learn about how coffee and maple syrup can be grown in habitats that also protect birds and wildlife.

Seeding Change: Land Projects at MFFC in 2025

Border Softening: Near Birch Pond, our team is preparing to plant a diverse mix of native trees and shrubs, including serviceberry, elderberry, beaked hazelnut, and red and white oak, as part of a forest edge softening effort designed to improve ecological function and climate resilience. By transitioning from an abrupt boundary to a layered, structurally diverse edge, this planting will reduce wind and light penetration, moderate temperature and moisture fluctuations, and buffer interior forest habitat from external stressors. The selected species offer a range of flowering and fruiting times, providing season-long food sources for birds, pollinators, and other wildlife, while also enhancing cover and nesting opportunities. In total, over 200 stems will be planted in staggered groupings to mimic natural regeneration patterns, with more to come through continued support from NRCS’s Conservation Service Provider program. Over time, this project will increase habitat complexity and biodiversity and serve as a model for climateadaptive, ecologically sensitive land stewardship.

Tree & Shrub Establishment: This project in Old Town Pasture is funded through VT DEC’s Regional Conservation Partnership Program for sustainable grazing. This effort marks the beginning of a long-term silvopasture initiative, where native trees and shrubs will be planted in rows or clusters through grazed fields. Species are chosen for their adaptability and ecological value, and for their compatibility with pasture dynamics and livestock health. As these trees establish, their root systems will help stabilize soil, reduce compaction, and improve water infiltration. Their leaf litter will contribute organic matter and support below-ground microbial life, enhancing overall soil health. Above ground, the trees will provide shade and windbreaks for grazing animals, helping to moderate heat stress and improve animal welfare. The added vegetation layers will also increase plant and insect biodiversity, create habitat corridors, and contribute to long-term carbon sequestration both above and below ground. This integrated approach offers a regenerative land management model that balances agricultural productivity with climate resilience, ecological adaptation, and habitat enhancement.

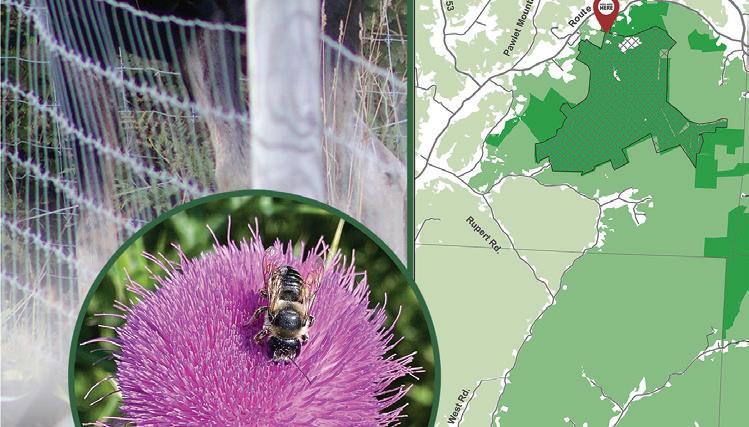

Pollinator Habitat Establishment: We have conducted an array of native pollinator enhancement plantings around the farm and at the visitor center, thanks to the generous support of Nature Aligned Vermont. These plantings represent both ecological landscape improvements and tangible climate solutions. The project will establish diverse, flower-rich habitat patches in pasture margins, fencelines, and other underutilized spaces, using a thoughtfully selected mix of native grasses, wildflowers, and woody shrubs. These species were chosen for their staggered bloom periods, providing a continuous supply of nectar and pollen from early spring through late fall. In addition to seeding, the project features the construction of a large hugelkultur mound, a permaculture-inspired raised bed made from decomposing wood and organic material, planted with deep-rooted, pollinator-friendly native shrubs. This technique not only supports floral diversity but also enhances soil fertility, water retention, and carbon storage. As these habitats mature, they will support native bees, butterflies, and other beneficial insects that are critical to crop and ecosystem health, increase pasture resilience, promote natural pest control, and contribute to the overall ecological integrity of the farm landscape.

A Snapshot of Learning & Stewardship at Merck Forest & Farmland Center

LEGACY PROGRAMS

Meet & Feed Connect with farm animals & daily rhythms.

Sap to Syrup Hands-on maple sugaring experience.

Full Moon Hikes Explore forest trails by moonlight.

Wreath Workshops

Seasonal creativity meets woodland materials.

Game of Logging

Backwoods safety & certified skills

Wilderness First Aid Train for safer exploration in remote places.

LEARNING FOR ALL - PRE-K TO GRAY

300+ K-12 students from 20 schools

New elder workshops at Bromley Manor

College partnerships: Williams, Tufts, Harvard, Rutgers MFFC is a living classroom—from toddlers to tenured reasearchers.

SUMMER CAMPS

100+ campers over 7 weeks. Staff trained and ready for adventure

First bilingual field trip

Spanish-speaking students welcomed new resources

Kits & Cubs 500+ early learners explored Merck through play

Little Sprouts Pilot drop-off toddler camp launching this year

VOLUNTEERS & PARTNERS

Trail work, mowing, firewood, and more.

Longstanding ties with the Student Conservation Association (SCA)

New partners: MEVO & Farm & Wilderness Camp

NEW WAYS TO ENGAGE

Fall Foliage Wagon

Rides Ride through peak color, learn seasonal ecology.

Tracking Hikes Decode wildlife signs with expert guides

Tree to Cutting Board & Ornament Making Craft forest materials into meaningful keepsakes.

MFFC

We’re building on the care that came before us, while shaping what’s next.

A place where learning, stewardship, and love for the land are lived, shared, and passed on.

We asked our community for a word that they think best describes Merck Forest. Here are their responses.

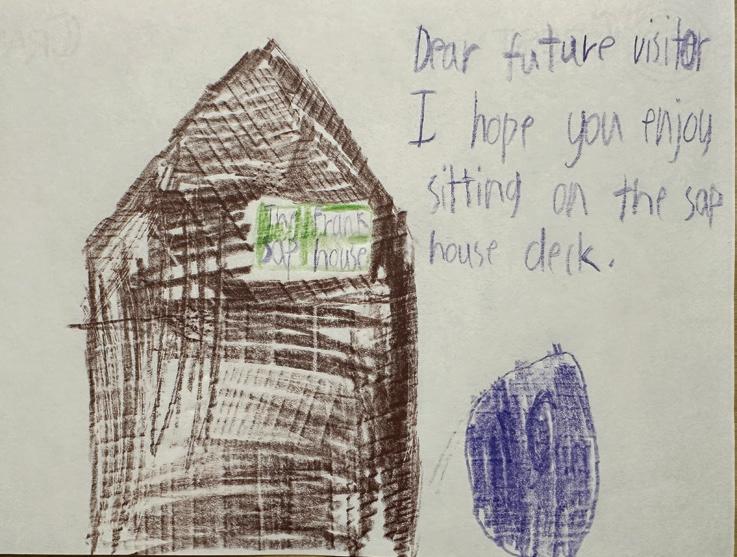

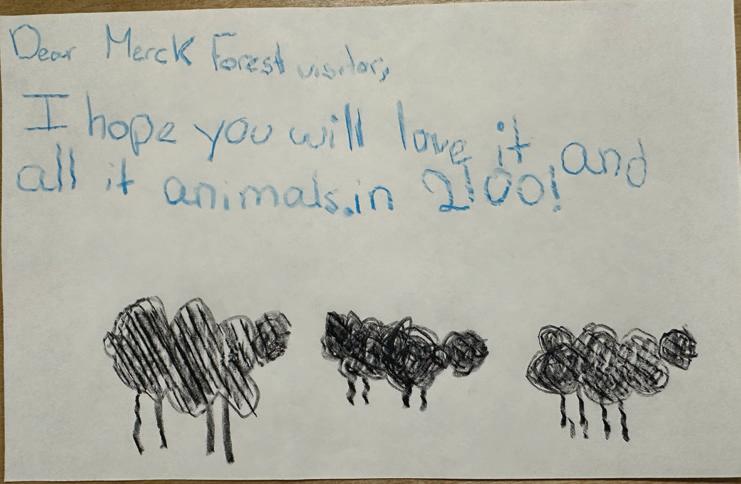

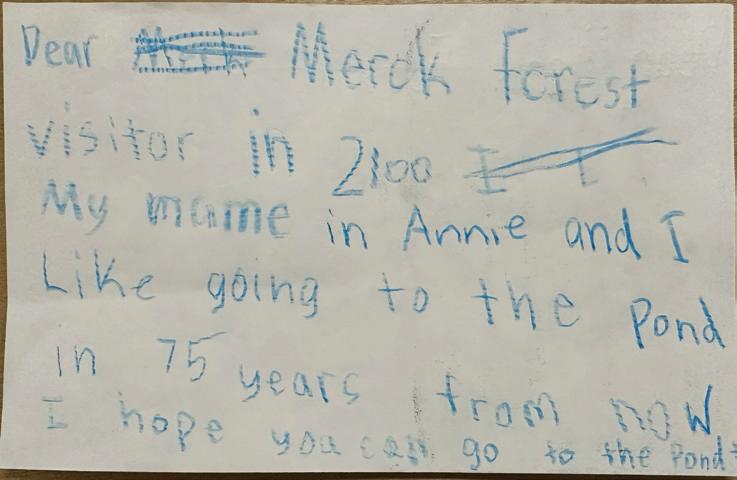

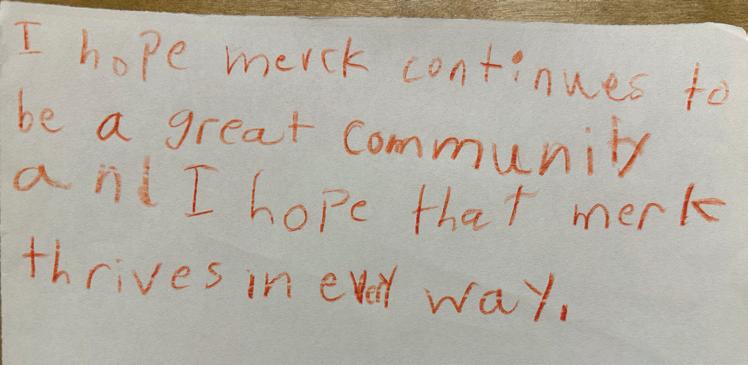

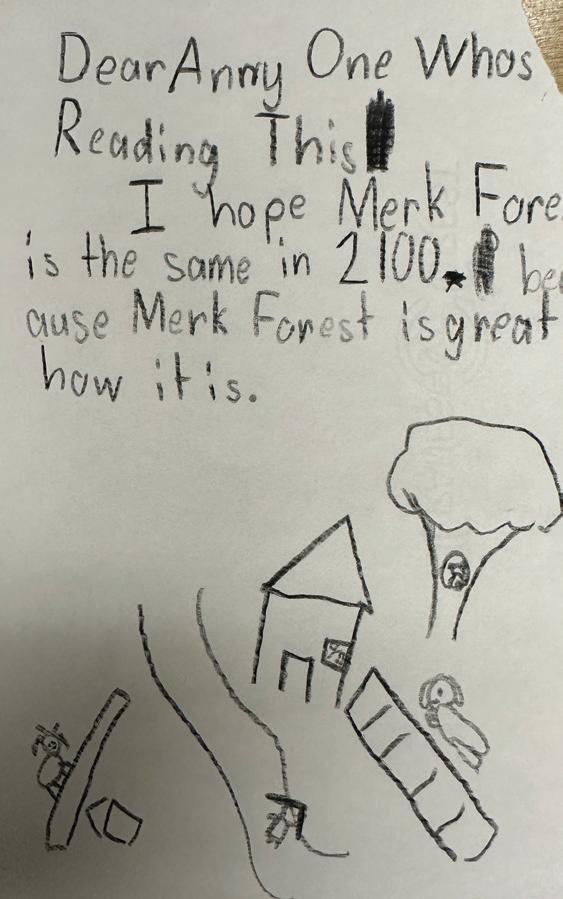

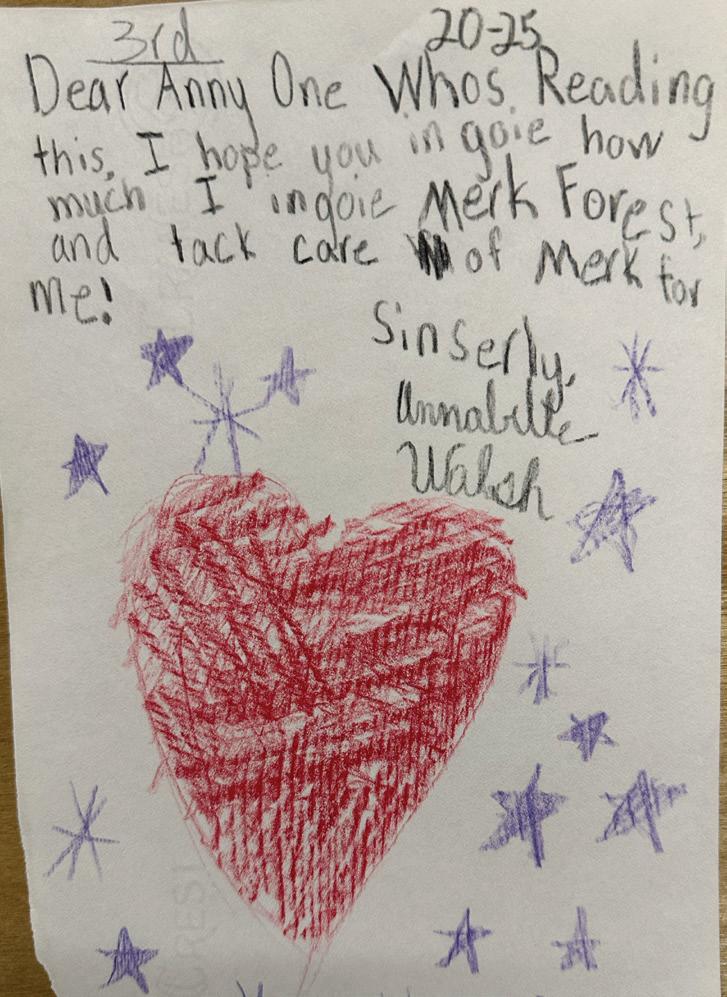

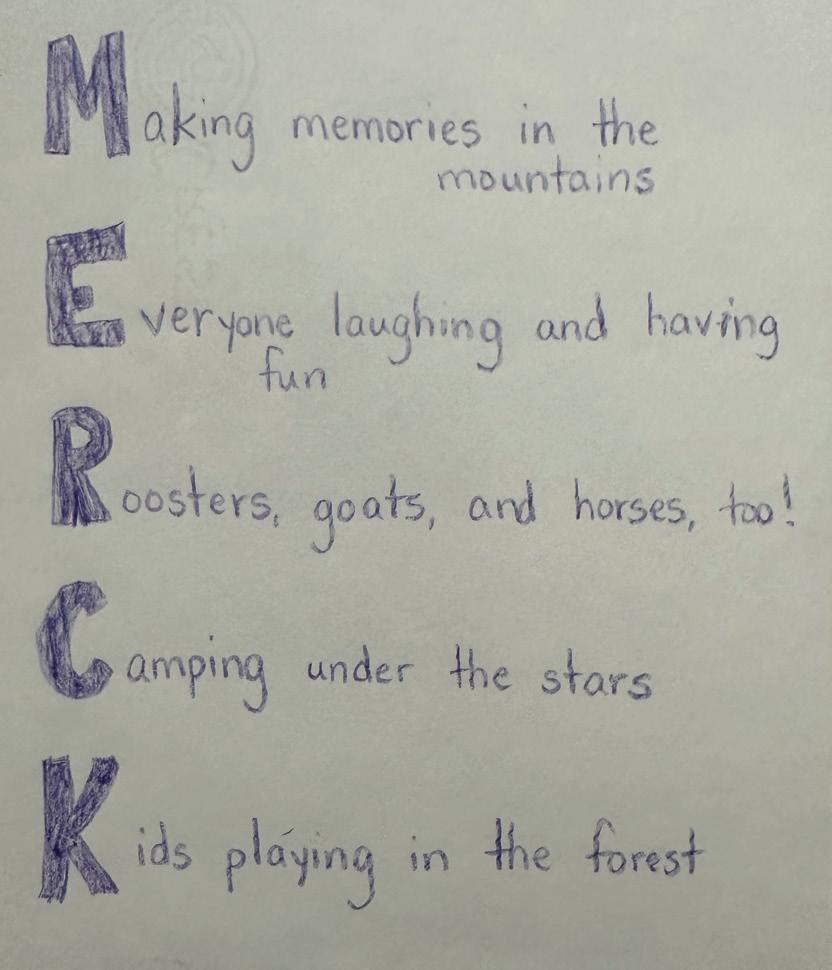

Letters to the Future: Wishes from

Today’s Young

Stewards

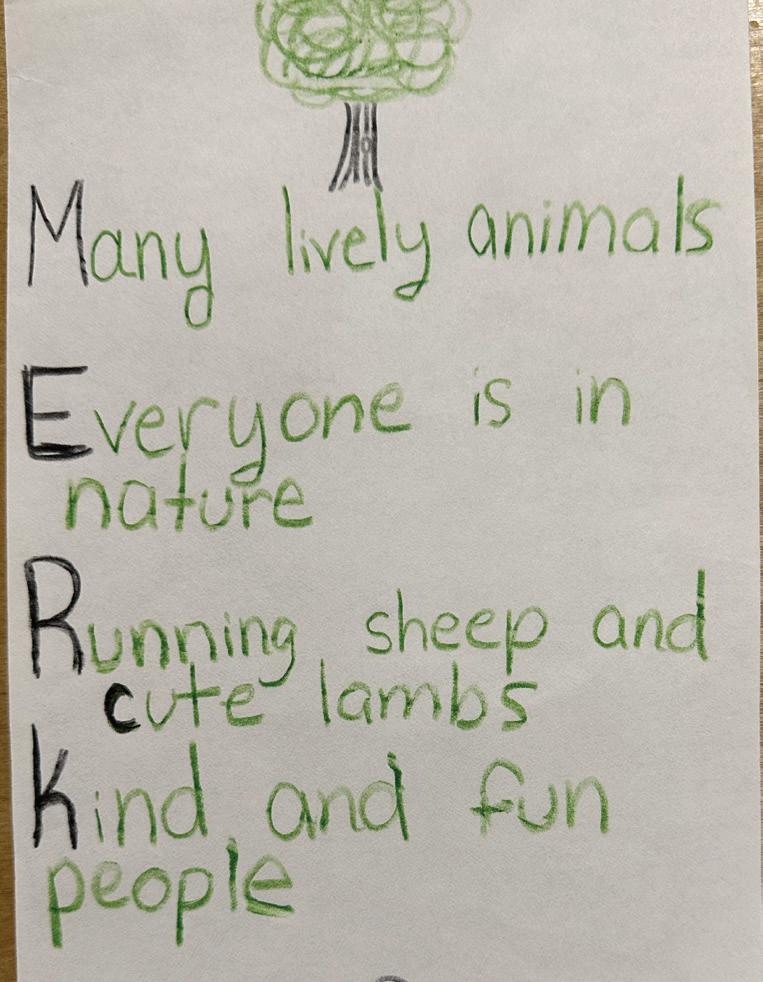

As part of our 75th anniversary celebrations, we invited two groups of students, 1st and 7th graders, to help us imagine Merck Forest 75 years from now. We asked them to write letters to the future: messages for the visitors who will walk these trails and explore this landscape in the year 2100.

Their prompt was: “Merck Forest & Farmland Center is turning 75 this year! What do you hope people will see, feel, and care about when they visit Merck Forest in the future? What message would you send to someone your age walking the trails or taking care of the land in the future?”

With crayons, colored pencils, and imagination, these young writers and artists shared what they love about MFFC today, and what they dream it will be like tomorrow.

These letters and drawings reflect the curiosity, care, and creativity of the next generation of land stewards. We hope you enjoy their visions and that their wishes come true.

PRESENT

To all past and future caretakers of Merck Forest & Farmland Center, Thank you.

To those who came before us: you built trails, raised barns and animals, hauled sap, built cabins, welcomed school groups, faced world-class Rupert windstorms, harvested trees, and tended this land with care and intention. Your work lives on in the soil beneath our boots, in the fences that still hold, and in the programs we continue to grow. We stand on what you built.

To those who will come after us: this land will ask things of you, patience, curiosity, courage. You’ll face the challenges of your day, celebrate breakthroughs and victories, and settle into the daily rhythms that shape this place over time. We hope you’ll carry forward the same spirit of stewardship and reverence that has shaped MFFC for 75 years.

This forest and farm belong to no one and to everyone. It is a living classroom, a working landscape, and a place where people grow through labor, learning, and connection.

We’re proud to be part of this heritage. Thank you for being part of it, too.

Sincerely,

The 2025 Merck Forest & Farmland Center Staff

Renata, Darla, Stephanie, AJ, Hazel, Cara, Dylan, Bella, Marv, Chris, Eric, Marybeth, Dillon, Keenan, Tom, Amy, Elena, John, Hadley, Mike, Rob, Ryan

LOOKING FORWARD POSSIBLE

As Merck Forest celebrates 75 years of stewardship, it reaffirms its commitment to:

• Testing and sharing sustainable practices

• Nurturing future generations’ relationship with the land

• Modeling how working landscapes can thrive alongside conservation

• Serving as an inclusive resource for all

We invite you to be part of the next chapter—on the trail, at the farm, or around the campfire.

Voices from the generation that will have a hand in shaping the future and who are looking to do that work.

Keenan McMorrow, Land Management Assistant

Working at Merck Forest & Farmland Center as a Farm Assistant, I’ve gained a wide range of hands-on skills that I know will serve me well as I continue my studies.

Tessa McGann, County Forester

What I’m most interested in is thinking about shifting the relationship between people, our society, the forest, and the earth in general, and not seeing ourselves as so separate from it.

Robin Wall Kimmerer’s idea of reciprocity is essential to my land ethic. Especially as a county forester, I meet with private land owners all the time, and answer questions, and help guide them in their forestry work, and, to me, that’s grounded in just trying to bring them into an active and reciprocal relationship and see that we can say, yes, thank you for these gifts. There are so many gifts we get from the forest.

And then, how can we actively give back?

Something I also think about is scale; instead of all these individual little parcels, I consider the bigger picture and how they all fit together.

I would love to have tools to integrate that better, to have people work across boundaries with their neighbors more easily, at the town level, at the county level, and even bigger, across states, and break down those boundaries.

I’ve learned to drive and operate all kinds of equipment: excavators, tractors, bulldozers, a diesel 4x4, a sawmill, and a wood splitter. I’ve even mastered the mini truck’s manual transmission. I’ve helped care for animals I had never worked with before, rabbits, pigs, goats, sheep, chickens, turkeys, and horses, and I’ve learned how to process poultry, bottle maple syrup, and build a solid fence. My tree identification has improved a lot thanks to the mentoring I have received at Merck Forest, and I’ve begun to understand the thinking behind long-term forest decisions by working with MFFC’s staff and forester.

There’s still so much more to learn but what I’ve already gained here goes beyond technical skills. It’s given me a clearer picture of what responsible land stewardship looks like, and the kind of care and attention it takes to do it well.

I’m heading to graduate school at Paul Smith’s College this summer, and wherever I go from there, I know these experiences will help me contribute to a more sustainable future.

I’m really inspired by a retired county forester up along the Canadian border who worked with an organization called Two Countries, One Forest, that was trying to think across scale into Canada.

Scan here to listen to a clip from Tessa’s interview!

I’m thinking all the way down to landowners who have less than an acre, any amount of woods, thinking about just bringing our society back into relationship with our land. All those little pieces make up this bigger picture, and I think those smaller pieces have been neglected. Vermont is going to see more people moving here, and as a result, more people will need housing. We’re going to see more and smaller parcels.

It’s exciting to think about how to work with people on that scale and get them working together as well. And coordinating around, what are the habitat needs? What are the animals here? What are the plants here? What needs to be moving with climate change, either to avoid threats or take advantage of opportunities, and how can we help make sure that they can do that?

Bella

Garrison,

Summer Camp Counselor

Working as a camp counselor at Merck Forest & Farmland Center has been a great source of personal growth for me. Leading campers through hikes, helping them connect with the land, and watching their curiosity expand taught me how crucial education and hands-on experience can be in shaping our relationship with nature. That experience helped confirm my decision to study fisheries. I realized I wanted to be someone who helps others understand and care for the ecosystems around them, especially our water systems.

At camp, I learned to translate complex ideas about conservation and stewardship into meaningful and digestible moments for kids. Whether it was exploring a pond, helping out with chores, or just sitting quietly in the forest. That kind of work taught me the value of patience, communication, and fostering connection to a place.

In the future, I hope to work in fisheries in a way that combines science and outreach. Helping communities better understand, access, and care for their watersheds. Merck Forest helped me see that even small moments, like a camper’s first time holding a salamander, can spark a lifelong sense of stewardship.

The Weight of Time: Merck Forest in a Warming World

By Rob Terry, Executive Director

What the past 12,000 years reveal about the future of land stewardship

As recently as 12,000 years ago, what we now call Vermont lay buried beneath two miles of ice—a frozen landscape shaped over tens of thousands of years. Evidence of this glacial past is still visible at Merck Forest, where massive, out-of-place boulders known as glacial erratics dot the terrain. During this Ice Age, the region was home to woolly mammoths and mastodons, and our human ancestors lived as small, mobile bands of huntergatherers, just as they had for nearly 300,000 years.

The Holocene

Today, Vermont’s temperate forests are a far cry from the ancient tundra those giants once roamed. Despite recent summer highs pushing toward 100°F, we are still technically living in an ice age. More specifically, we’re in an interglacial period called the Holocene, which began 11,700 years ago and is defined by a relatively stable, moderately warm climate. That stability enabled agriculture, population growth, and the rise of civilizations— transformations that occurred in the most recent 10,000 years of humanity’s 300,000-year history. We’ve accomplished quite a bit in just the last 4% of our time on Earth.

SSP stands for Shared Socioeconomic Pathway. It describes how society, the economy, and technology might develop in the future. SSP5 represents a future where the world relies heavily on fossil fuels (like coal, oil, and gas) and prioritizes rapid economic growth, with little concern for reducing emissions or switching to clean energy.

The 8.5 refers to radiative forcing, which is a measure of how much extra energy gets trapped in Earth’s atmosphere due to greenhouse gases. 8.5 means a large increase in trapped heat, leading to very high levels of warming.

So, SSP5-8.5 represents a “business-asusual” scenario where fossil fuel use keeps growing and greenhouse gas emissions rise sharply. If this path continues, scientists project significant global warming by the end of the century, with major impacts on ecosystems, weather patterns, sea levels, and human health.

It’s one of the worst-case scenarios and is often used as a baseline to show what could happen if we don’t take action to reduce emissions.

The Anthropocene

This remarkable progress has come at a cost. Through extensive research and experimentation, many scientists contend that the massive release of carbon dioxide— first through deforestation and later through fossil fuel combustion—has driven Earth out of the Holocene and into a new epoch: the Anthropocene, or “age of humans.” Whether or not this shift is officially recognized, the impacts are undeniable. Since the 1950s, global temperatures have risen to levels unprecedented in human history.

We’re seeing the effects: in Vermont’s forests, milder winters enable invasive insects to move northward, threatening native tree species. At the same time, shifting precipitation patterns drive an increase in more frequent and severe floods and droughts. Climate projections are sobering. Our most extreme emissions scenario, SSP5-8.5, forecasts a global temperature rise of up to 12°C over the next 275 years, reaching conditions not seen on Earth in 45 million years. Even more moderate models, like SSP1-2.6, which would require widespread action to curb emissions, still predict a warming trend that pushes us well beyond the familiar climatic envelope that has shaped human society.

Here at Merck Forest, we are part of the first generation of land managers who fully understand the extent and impact of anthropogenic forcing, human-driven changes to the climate caused by burning fossil fuels, converting forests, and building cities. Actions that add heat-trapping gases to the atmosphere and alter how the Earth reflects sunlight fundamentally shift the planet’s climate system. The question is no longer “Will things change?” but “How will they change?” Regardless of where we land in the global emissions gap between SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5, the natural communities we know today will experience clear and measurable changes in the coming decades that will compound into far-reaching ecological transformations over the centuries ahead.

Lessons from Deep Time

This is not nature’s eulogy. Earth’s forests have endured for over 400 million years. They’ve survived extremes, including the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), which occurred roughly 56 million years ago and saw global temperatures exceed even the high-end projections of SSP5-8.5, with profound effects on ecosystems worldwide. Forests shifted in composition and distribution in response to rapid warming, elevated CO₂ levels, and intensified hydrological stress. Fossil evidence shows that deciduous and coniferous trees grew in the Arctic and Antarctica, and subtropical species like palms, ferns, and even alligators lived in what are now polar deserts. Despite such dramatic changes, many forest ecosystems showed remarkable resilience and adaptability over the PETM’s 100,000–200,000-year span.

Change is Here

The current pace of climate change, however, is unprecedented and concerning in geological terms. Today’s warming is occurring 10 to 100 times faster than past natural events like the PETM, leaving ecosystems with little time to adapt. As a result, we are entering a period of rapid ecological transformation, one without historical precedent in human experience. The landscape at Merck Forest is showing early signs of disruption. Rising winter low temperatures enable invasive insects and nematodes to expand their range northward, threatening forest species such as ash, hemlock, and beech. Traditional management strategies are proving increasingly inadequate.

For generations, terms like conservation, preservation, and restoration have guided our efforts to build sustainable relationships with the natural world. They often share a common impulse: to respond to environmental loss by referencing a past ecological state. But increasingly, land stewards and scientists alike recognize that our relationship with nature must also look forward, embracing change, complexity, and the understanding that humans are not separate from nature, but embedded within it.

Rethinking Stewardship

In the face of this uncertainty, we must cultivate resilience. We must forge new relationships with our plant and animal neighbors, drawing on the traditional ecological knowledge and sense of interspecies kinship central to many Indigenous cultures. Simultaneously, we must acknowledge the growing body of science showing that countless species, including plants, make decisions, communicate, and form complex social relationships. It is time to reassess our place in the living world, not as observers from the outside, but as participants within it. We are not “in” nature. We are of nature.

“Adaptive management acknowledges uncertainty and treats every action as both a solution and an experiment.”

Protecting biodiversity and ensuring Earth’s continued habitability goes beyond the imperative to reduce emissions and limit atmospheric carbon. Even our most optimistic climate models suggest that, within the next 50 years, the planet will be warmer than at any point in human history. The luxury of waiting for long-term study results is behind us. We must develop new adaptive management strategies that move us beyond strictly linear, hypothesis-driven science and into a more responsive, iterative approach, one grounded in learning by doing.

A New Way Forward

Adaptive management acknowledges uncertainty and treats every action as both a solution and an experiment. It requires land managers to make informed guesses, implement them, monitor outcomes, and adjust course as conditions evolve. In a changing climate, this dynamic, feedback-driven approach is pragmatic and essential. In addition to enhancing how we plan, assess, and adapt our work, we must also implement new practices to help regional ecosystems adjust to shifting conditions. That means moving beyond our current focus on sustainable rotational grazing and restoration-based ecological forestry. We must include new tools like climate-informed reforestation, which considers future conditions when selecting species and seed sources for active planting.

In the coming decades, many native plants and animals will migrate north in search of suitable habitat. Plants, in particular, will require human assistance to move quickly enough to keep pace with the rapidly changing climate. In response, Merck Forest will adopt a suite of emerging practices, including assisted migration and land sparing, as well as broader frameworks such as biodiversity-centered design and social-ecological co-management.

Merck Forest’s future will depend on teaching and modeling effective adaptive management, ensuring we can respond in real time, develop new strategies, and collaborate with our plant and animal neighbors to sustain regional biodiversity for generations to come.

For more: Read Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer for a lyrical, Indigenous perspective on reciprocity and relationship with the natural world. For a more academic lens, Sacred Ecology by Fikret Berkes connects traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) to modern land management practices.

A New Day at Merck Forest

Merck Forest & Farmland Center was shaped by bold ideas and people willing to bring them to life.

Noted forester (and cousin to George Merck) Carl Schenck laid down what he called an impossible challenge: to restore a deforested Vermont hillside, to reimagine working lands as places for public learning, and to model a new kind of stewardship. George Merck and others rose to meet that challenge with vision, humility, and grit. Today, we face a different kind of complexity: climate change, ecological uncertainty, and the vital need to reconnect people with the land. We stand on firmer ground with a vibrant community behind us, 3,500 acres under our care, and a mission that’s more relevant than ever.

With your support, we will accomplish what once seemed impossible. There is work ahead, and we begin, as always, with purpose and hope.

Below is the message Dr. Schenck wrote, more than 70 years ago (October 25th, 1952) to the Trustees and Advisors of the Vermont Forest and Farmland Foundation. His words guide us today.

Dear Trustees of the V.F.&F.F

I am afraid I have submitted to you a program much too long, too timestaking, and too expensive for adoption! Of course, my program cannot be carried through in one year, nor is it realizable in ten years. But, mind you! Whatever success this V.F.&F.F may have, depends on YOU, on YOUR active, personal interest and cooperation with the founder and notably with the forester of the Foundation. As a matter of fact, the most important question and problems of research - more important than the 10 material, substantial, terrestrial problems just enumerated taken together - are the human, are the spiritual problems which complete my dozen of problems by bearing numbers XI and XII: What can each one of the Trustees of the V.F.&F.F do individually, actively cooperating with a foundation established with that aim and goal, for the improvement of forest and farmland in the State of Vermont?

Very respectfully yours, but always with a smile,

C.A. Schenk