5 minute read

South East Asia production

READY, WILLING AND ABLE?

With more manufacturing shifting from China to South East Asia, AJ Keyes assesses the impact on port requirements in Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia

China has been the biggest exporter on a global basis since 2009, with hundreds of millions of its workers manufacturing and producing goods for shipment throughout the world. As the world’s most populous country, with 1.4 billion people, China possesses a massive low-cost labour force that has played a major part in the globalisation of supply chains satisfying demand for cheaper products wordwide.

However, times are changing. The cost of doing business in China is rising, with higher labour costs making profits thinner, and recent trade and political issues with other key economies, notably the USA, resulting in the country’s stranglehold over the world’s manufacturing being disrupted.

Consequently, demand for production in South East Asian countries like Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia is rising.

Yet, while China’s ports have developed over the past 20 years to keep pace with the country operating as the “world’s factory” a key question is will the shift of activity to these other developing countries be supported by sufficient terminal capacity and infrastructure?

BIG NAMES MAKING THE SHIFT

There are a number of manufacturing companies that have shifted or are preparing to move from China to South East Asian countries. One highly notable name is Apple Inc., the multinational technology company.

In mid-2019, the UK’s Financial Times reported that Apple had already looked at the benefits of shifting up to 30 per cent of its production activities out of China and into countries in South East Asia, as part of a restructuring of supply chains. So, this was already in place ahead of recent COVID-19 disruptions. As one terminal operating executive, who did not wish to be named, says: “It may be called restructuring, but it means reducing costs. China has become more expensive, whereas other locations, such as Vietnam and others in South East Asia are now cheaper and as such a more attractive proposition.”

Apple is not the only global brand adopting this strategy. Well-known sportswear companies, Adidas and Nike, have also moved significant manufacturing activities involving

8 Figure 1:

Overview of South East Asia Region

clothing and footwear production out of China and into South East Asia, with Vietnam and Thailand the preferred options.

“LUCRATIVE” OPPORTUNITIES

The decision (and publicity) generated as these globallyknown brands move manufacturing capacity, partially or wholly, out of China represents a strong statement about the viability of the country’s future manufacturing role compared to the increasing benefits of neighbouring locations in the South East Asian area.

Industry analyst, Dataand, confirms that the population throughout South East Asia continues to increase, rapidly and this combined with lower wages means that moving manufacturing activities from China to Vietnam, Thailand and Cambodia offers “lucrative” opportunities for cost reductions without any loss of quality of the output compared to China. Moving forward, the company further expects the automotive, electronics and raw material-based product businesses to realise further shifts of activity out of China into South East Asia.

It is also evident that the goods manufactured are all typical of what is moving in containers from Asia to key markets in North America and North Europe, in particular.

So, what does this mean for ports in South East Asia and are they prepared for what the future holds if manufacturing activity continues to increase? To begin with, it is important to see how volumes at ports have grown, with containers handled a good proxy of import-export development.

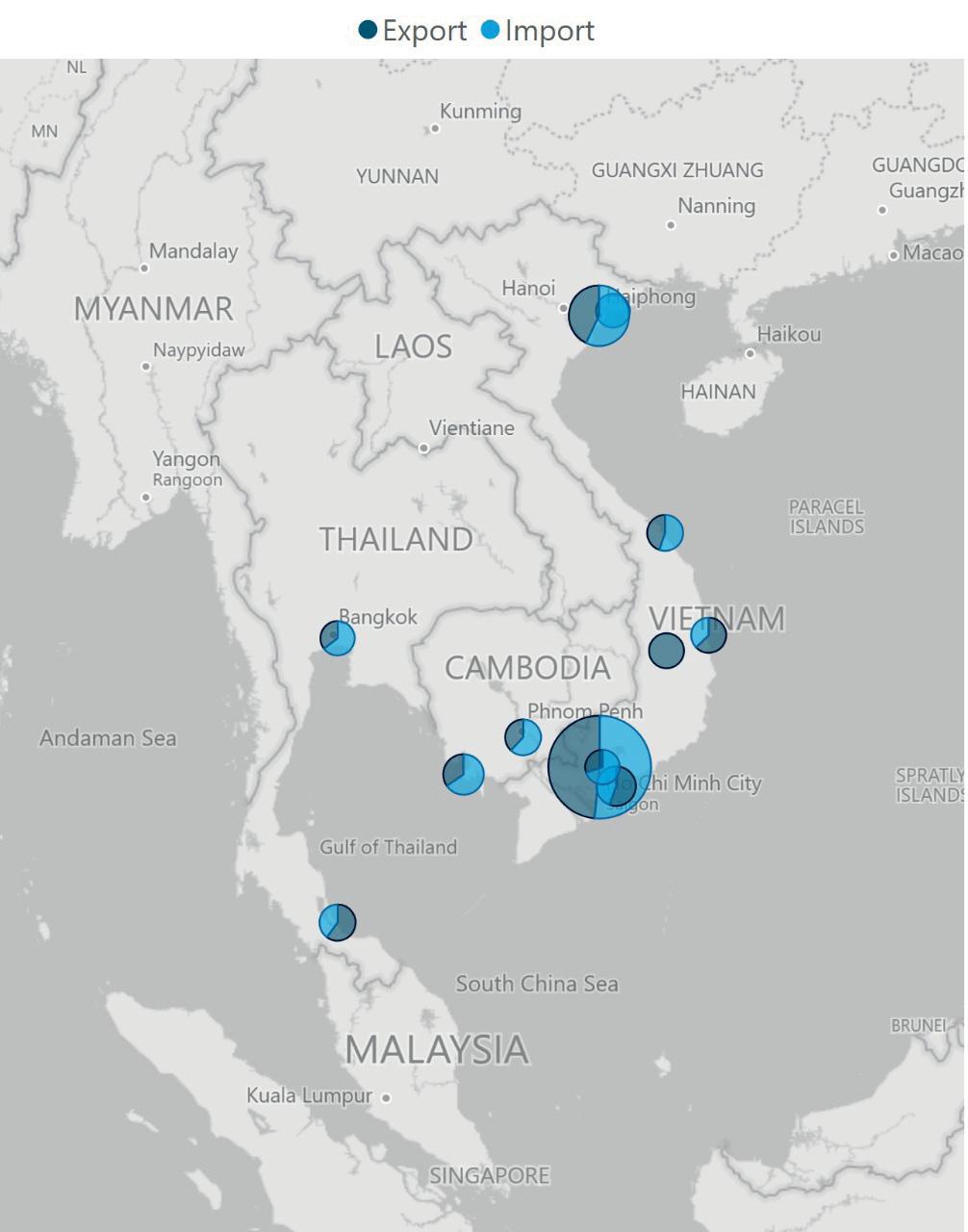

The location of the main container ports in the region is shown in Figure 2. The facilities identified are based on import-export activity, with the major gateways in terms of throughput being Ho Chi Minh (in the south of Vietnam), Haiphong (in the north of Vietnam), Bangkok/Laem Chabang (Thailand) and, for Cambodia, Sihanoukville.

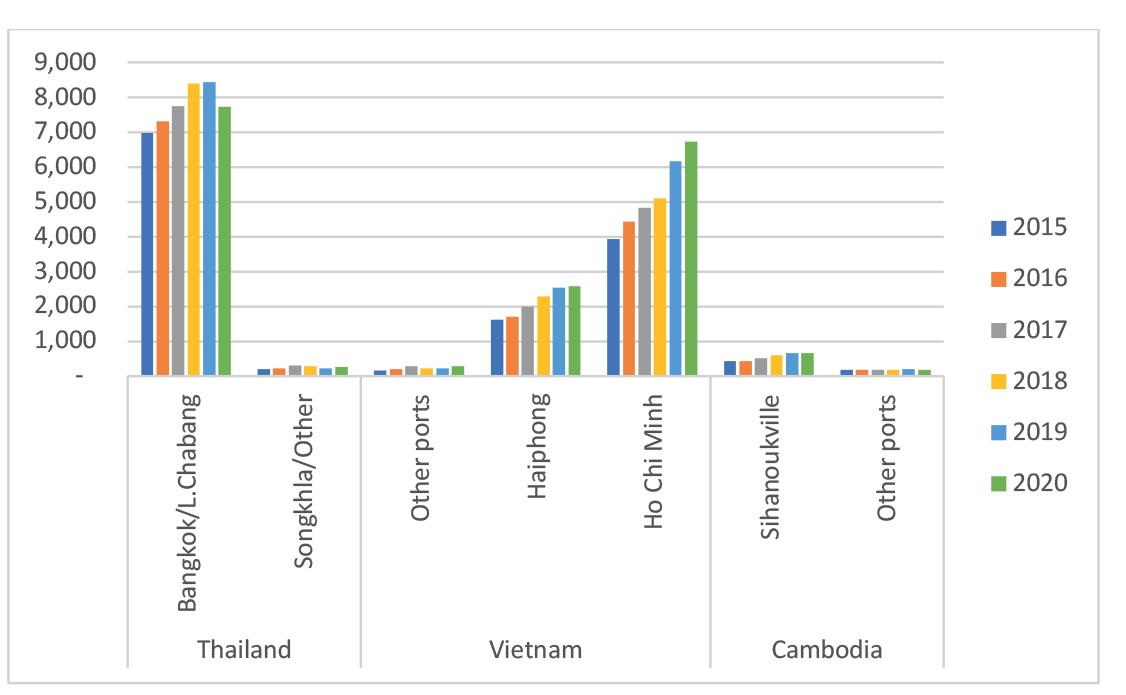

In terms of import-export container volumes (and excluding transshipment activity), there are several largescale ports in each country. For example, as Figure 3 shows, for Thailand the Bangkok/Laem Chabang port complex is dominant.

In 2015, this port area handled almost 7.0 million TEU, which continued to increase to 8.4 million TEU by the end of 2019. However, the COVID-19 pandemic saw a reduction to 7.2 million TEU during 2020. To put this level of activity into perspective, the other (minor) ports in the country handled around 265,000 TEU of import-export activity in 2020.

By comparison, Ho Chi Minh City terminal facilities in Vietnam recorded almost 6.7 million TEU during 2020, representing strong growth on the 2015 total of 3.9 million TEU, equal to 11.3 per cent per annum over this assessment period.

On the basis of the container volumes handled by the selected ports in South East Asia, there are strong increases in throughput from Vietnam, which is indicative of the trend of greater manufacturing of items typically shipped via containers and to consumer markets in North America and North Europe.

Strong growth has also occurred in the northern Vietnam port of Haiphong with an annual increase of 9.8 per cent recorded between 2015 and 2020, entailing throughput rising from 1.6 million TEU (2015) to 2.6 million TEU (2020).

As a result, ports in Vietnam have seen the collective 2015 total of 5.7 million TEU increase to reach 9.6 million TEU by the end of 2020 – equivalent to annual growth of 10.9 per cent per annum over this assessment period.

There was also no drop in 2020 as a result of the impact of COVID-19, with volumes handled by the country’s ports seeing an improvement last year of 6.9 per cent over 2019.

Cambodia’s container ports are much smaller in terms of throughput compared to the main facilities in both Thailand and Vietnam. The largest port in the country, Sihanoukville, has seen annual growth in the 2015 to 2020 period, rising from around 430,000 TEU to 648,000 TEU, which is equal to growth of 8.5 per cent per annum.

However, the total for 2020 was down on the throughput recorded for 2019 by -1.4 per cent, primarily due to weaker intra-Asian activity caused by the negative effects of COVID-19.

There is a requirement for major ports throughout South East Asia to offer sufficient infrastructure to keep pace with demand. The base question is, therefore, are the ports in question ready, willing and able to meet this challenge? The following article takes a close look at the state of readiness of gateway ports in Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia.

8 Figure 2: Principal

container port gateways in Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia

8 Figure 3:

Import-Export Container Volumes at Select Ports in South East Asia, 2015-2020

Note: Volumes are based on import-export activity only and shown in ‘000 TEU Source: Dataand