Experience the seamless combination of Georgetown’s historic architectural splendor and distinctive modern luxury at The Guyana Marriott Hotel Georgetown. Marvel at picturesque views of how the Demerara River meets the Atlantic Ocean and enjoy a charming welcome to nearby Georgetown’s central district with its various attractions and sites. Witness a breathtaking sunset by our pool bar and grill or re energize at our state-of-the-art fitness center.

Plan meetings effortlessly, with over 8,600 square feet of flexible meeting space. Whether hosting an intimate event for ten or a large-scale affair for 700, our Guyana Marriott Hotel Georgetown can easily accommodate your needs.

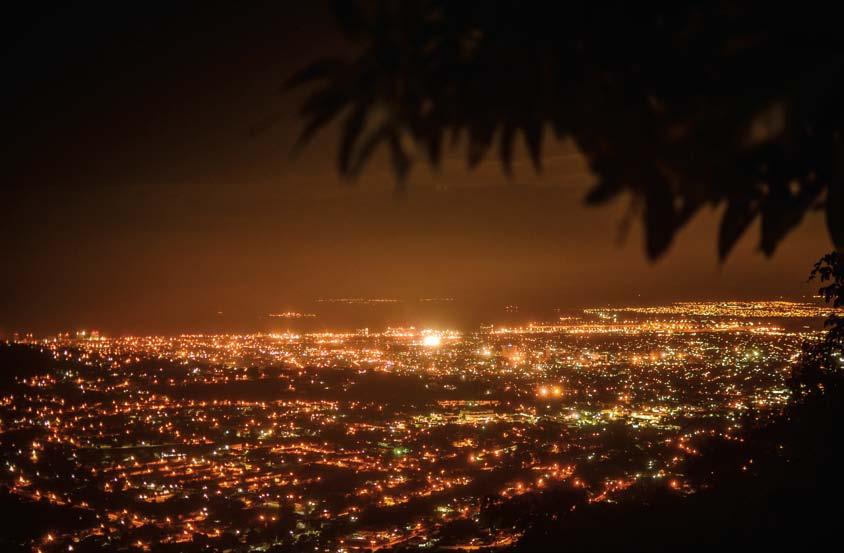

Book one of our 197 guest rooms or suites with views of the ocean or Georgetown’s city lights. Treat yourself to one of the best spots in Georgetown; full of light, full of life and full of energy, where you can work & play, mix, mingle, connect & relax. Travel Brilliantly.

MHRS.GEOMC.RESERVATIONS@MARRIOTTHOTELS.COM MARRIOTT.COM/GEOMC

19 DAtEBooK

Events around the Caribbean in May and June — from the St Kitts Music Festival to the Tobago Legends football tournament

26 WoRD of Mouth

Tropical beauty at Dominica’s annual flower show, and going the distance at the Rainbow Cup Triathlon

30 thE looK

Barbadian designers Shayla Cox and Kimberley Angoy are ready for beach season

32 thE DEAl

What the new Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative means for Trinidad and Tobago’s economy

34 BooKshElf

This month’s reading picks, from poetry to art to cricket

36 PlAylist

New releases to get you in the groove

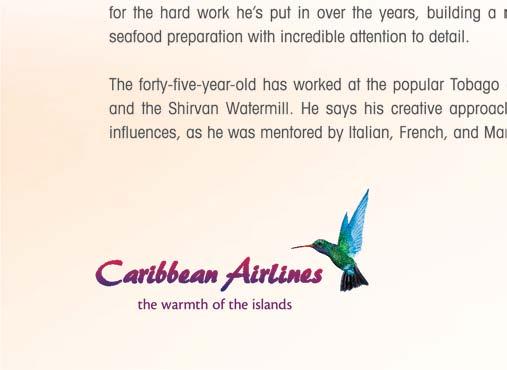

39 CooKuP

bright lights, big city, hot sauce

How did Bajan hot sauce end up on one of New York City’s trendiest restaurant menus? Jonathan Ali meets chef Paul Carmichael

No. 133 May/June 2015

42 PAnoRAMA ready for their closeup

Caribbean actors have been lighting up Hollywood screens for decades — even if you don’t recognise their accents. Caroline taylor looks back at the first generation of Caribbean movie and TV stars, and profiles some of today’s headliners who can claim Caribbean roots

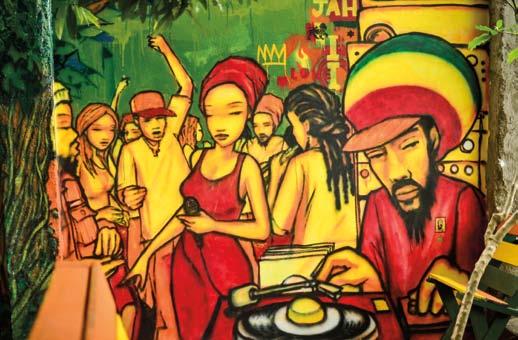

54 BACKstoRy dubbing is a must

In recent years, the Jamaican music scene has been gripped by a “Reggae Revival,” and the movement’s ground zero is a weekly gathering of musicians and fans high in the hills above Kingston. David Katz treks up to the Kingston Dub Club and meets founder DJ Gabre Selassie

60 shoWCAsE

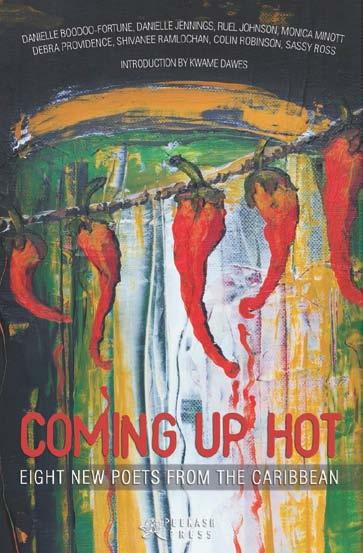

Two selections from the exciting new poetry anthology Coming Up Hot

62 snAPshot

the anti-expected

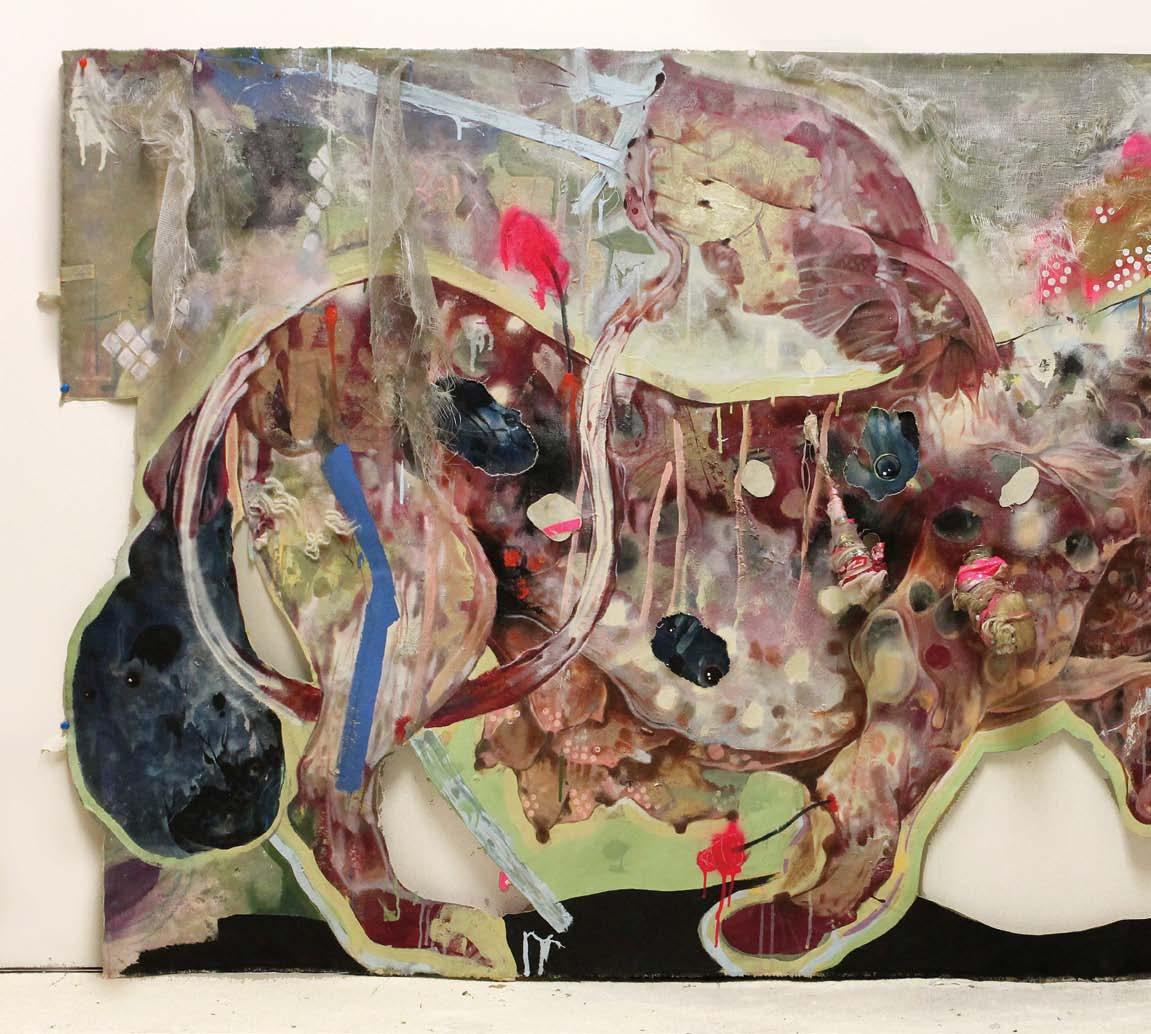

Selected for the prestigious 2015 Venice Biennale — the art world’s major international event — Bahamian Lavar Munroe creates mixed-media works that explore tricky ideas of “difference.” nicole smythe-Johnson finds out more

68 offtRACK

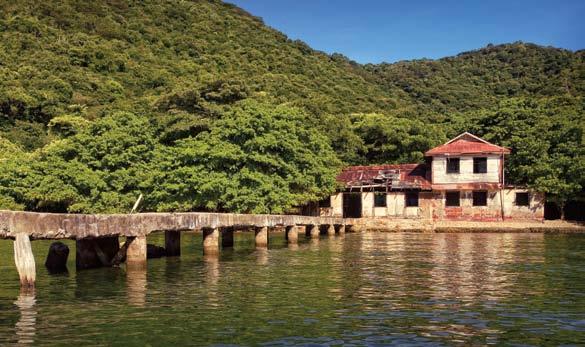

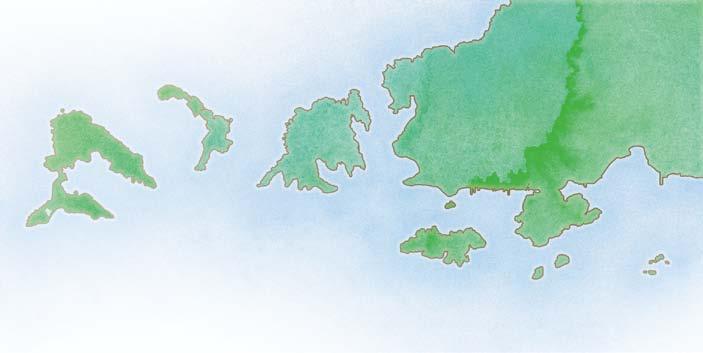

among the dragon’s mouths

The tiny islands scattered off Trinidad’s north-west peninsula, separated by the sea channels called the Bocas del Dragon, are beautiful and sometimes eerie outposts of history. Gasparee, Monos, Chacachacare, and the others have long been known as holiday retreats, writes sharon Millar, but their bays and hills also conceal a wealth of stories

76 nEighBouRhooD holetown, barbados

The oldest settlement in Barbados, founded in 1627, Holetown has history, a prime beachside location, and some of the island’s best dining and shopping

78 hoME gRounD the magic mountain

St John, smallest of the three main US Virgin Islands, is best known today as a vacation stomping ground for the rich and famous — “the Beverly Hills of the Caribbean.” But for David Knight, Jr, who grew up on its forested slopes, St John is a place of childhood mystery and family history, whose fragrant bay trees supported a once-famous industry long before the first tourists arrived

84 DisCoVER

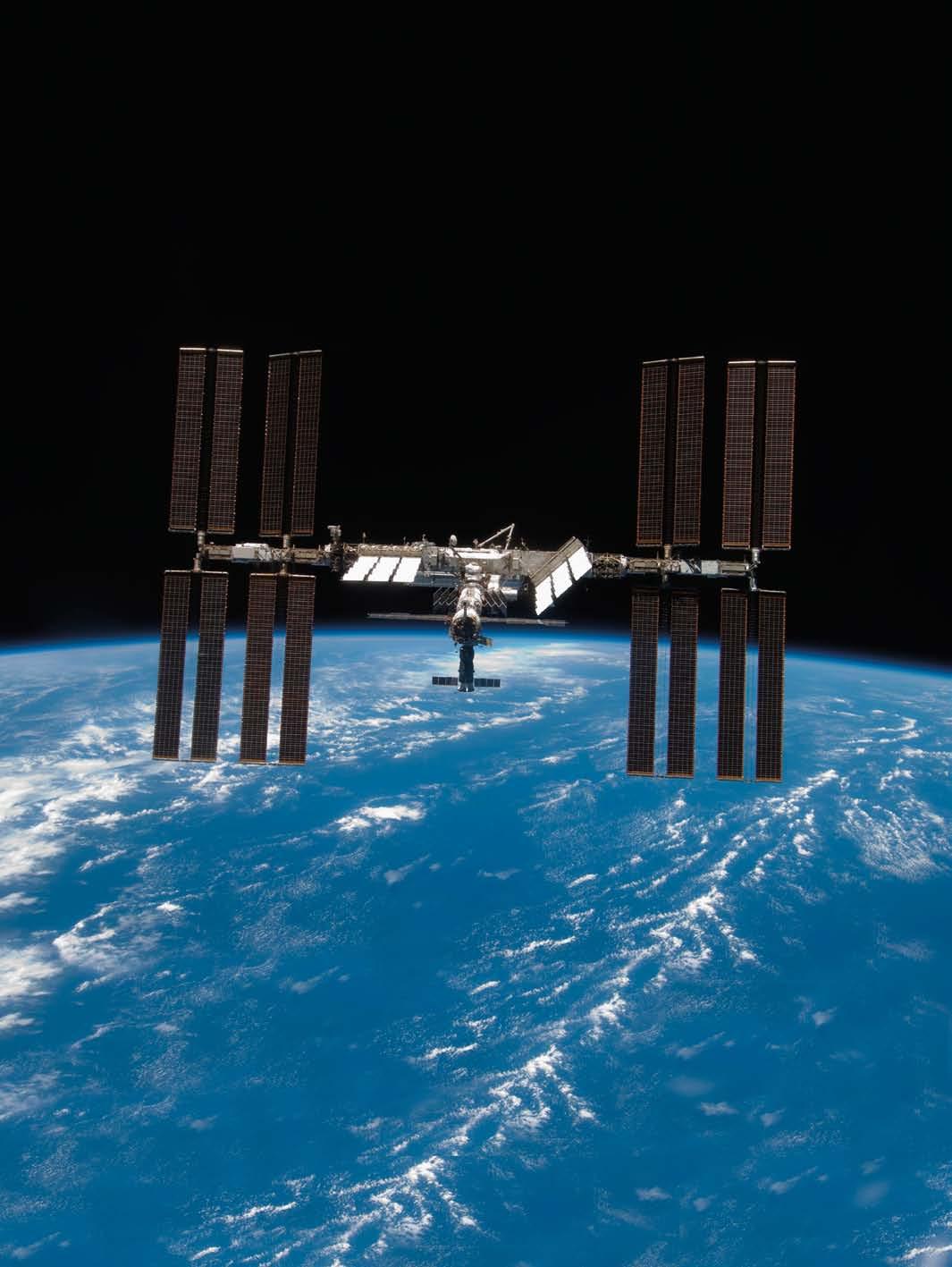

another giant leap

When a three-year-old Camille Wardrop Alleyne watched the 1969 Moon landing on TV, she couldn’t have imagined she’d one day be part of the exploration of outer space. As a NASA scientist, she now helps run the International Space Station. And her second passion, as Erline Andrews discovers, is the campaign to get more young people — especially girls — into the fields of science, technology, engineering, and math

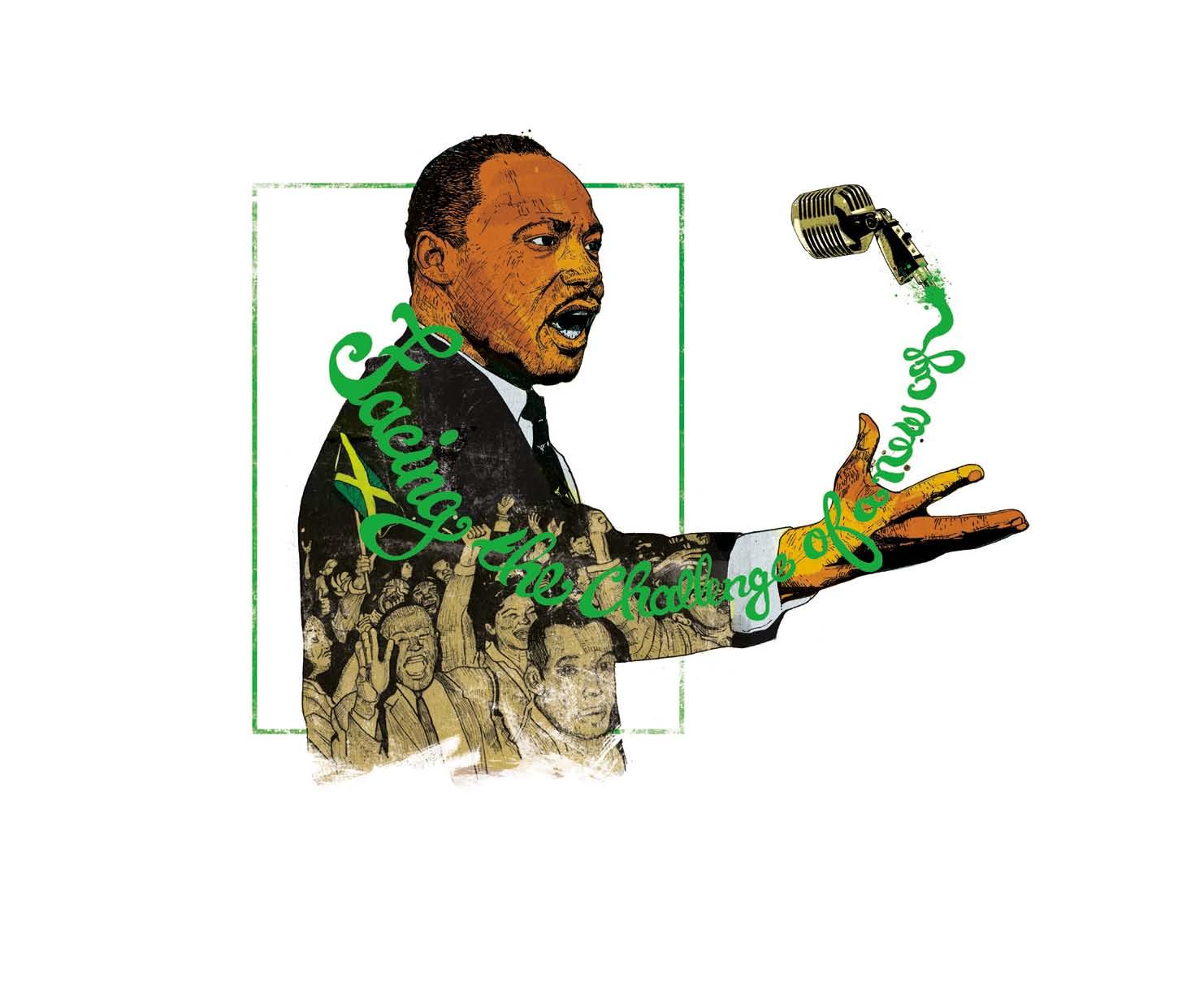

86 on this DAy out of many

Martin Luther King, Jr, visited Jamaica in 1965, at the height of his fame. He roused audiences there with his soaring speeches, James ferguson explains, but the newly independent nation inspired the Civil Rights hero just as indelibly

94 onBoARD EntERtAinMEnt

Movie and audio listings, to entertain you in the air

96 PARting shot

On the Bahamas’ Eleuthera Island, the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea are separated by whisper-thin Glass Window Bridge

Media & Editorial Projects l td, 6 Prospect Avenue, Maraval, Port of s pain, trinidad and tobago

Tel: (868) 622 3821/5813/6138

Fax: (868) 628 0639

E-mail: info@meppublishers.com

Website: www.meppublishers.com

Business Development Manager

trinidad & tobago

Yuri Chin Choy

T: (868) 460 0068, 622 3821

F: (868) 628 0639

E: yuri@meppublishers.com Printed

An MEP publication

ISSN 1680–6158

Editor Nicholas Laughlin

g eneral manager Halcyon Salazar

o nline marketing Caroline Taylor

Design artists Kevon Webster & Bridget van Dongen

Business Development Manager

Caribbean & i nternational

Denise Chin

T: (868) 683 0832

F: (868) 628 0639

E: dchin@meppublishers.com

folloW us:

www.facebook/caribbeanbeat wwww.meppublishers.com

www.twitter.com/meppublishers

this is your personal, take-home copy of Caribbean Beat, free to all passengers on Caribbean Airlines

Caribbean Beat is published six times a year for Caribbean Airlines by Media & Editorial Projects Ltd. It is also available on subscription. Copyright © Caribbean Airlines 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced in any form whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher. MEP accepts no responsibility for content supplied by our advertisers. The views of the advertisers are theirs and do not represent MEP in any way.

Website: www.caribbean-airlines.com

This issue’s contributors include:

Erline Andrews (“Another giant leap”, page 84) is an award-winning Trinidadian journalist. Her work has appeared in publications in Trinidad and Tobago and the US, including the Chicago Tribune and the Christian Science Monitor magazine.

Paul Crask (“The flower ladies”, page 26) is a freelance writer and author of two Bradt Travel Guides: Dominica and Grenada, Carriacou & Petite Martinique

David Knight, Jr (“The magic mountain” page 78,) is a writer from the US Virgin Islands, and the co-founder and co-editor of the journal Moko. He is currently collaborating on an overview of art history in the Virgin Islands.

sharon Miller (“Among the Dragon’s Mouths”, page 68) is a Trinidadian writer. Her short fiction collection The Whale House was published in 2015. She is the winner of the 2013 Commonwealth Short Story Prize and the 2012 Small Axe Literary Competition for Fiction.

nazma Muller (“The transparency challenge”, page 32) is a Trinidad-born, Jamaica-obsessed writer who has worked in newsrooms in T&T, Jamaica, and the UK. She is also the editor of Discover Trinidad and Tobago 2015.

nicole smythe-Johnson (“The anti-expected” page 62) is a writer and independent curator, living in Kingston, Jamaica. She has written for ARC magazine, Jamaica Journal, and several other regional publications. She curated three exhibitions in 2014 (Transforming Spaces, Float, and Trajectories).

Trinidadian Caroline taylor (“Ready for their closeup” page 44) makes a living doing what she loves most: telling stories. That includes acting (and directing) in theatre, film, and TV productions, and writing and editing for both print and online publications.

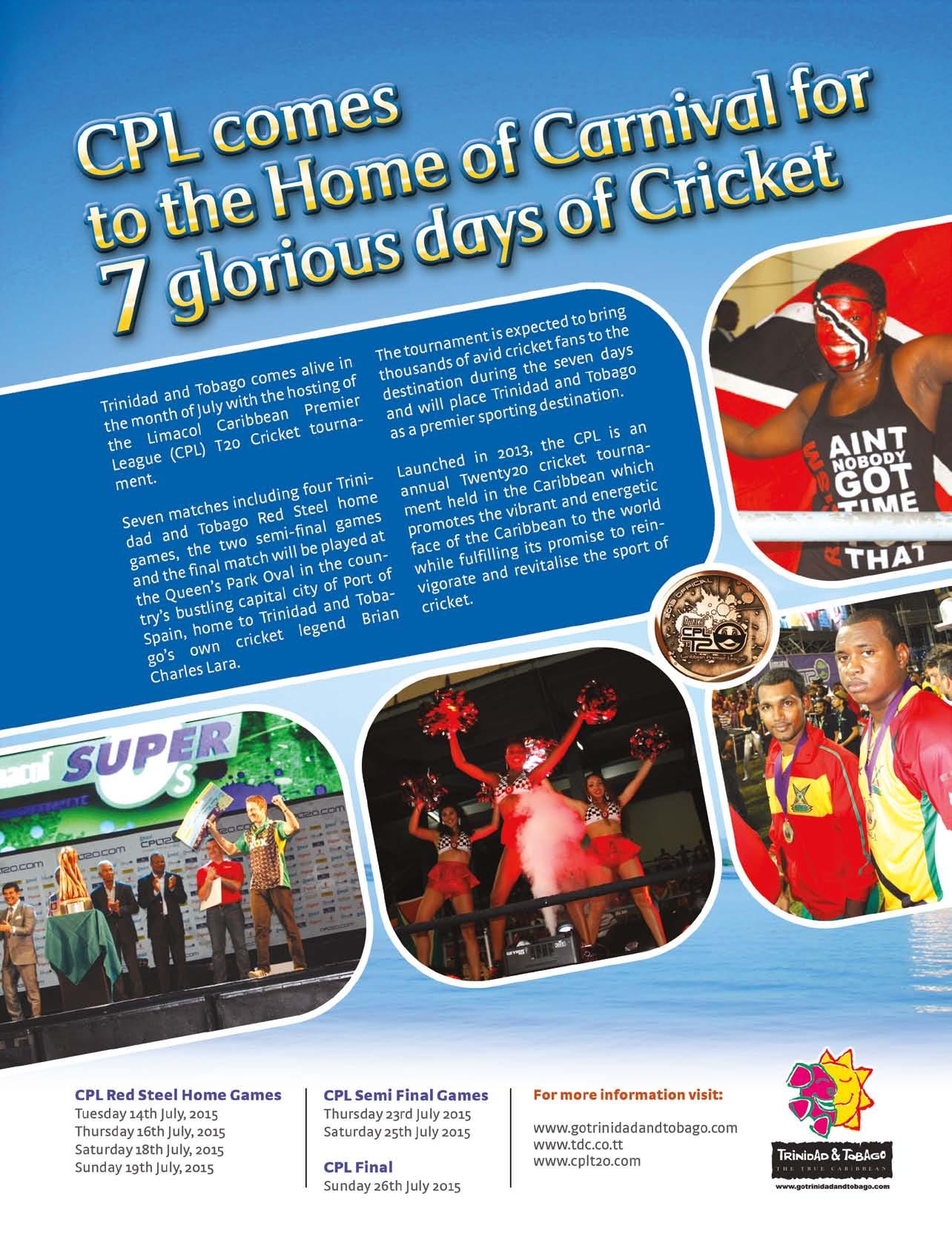

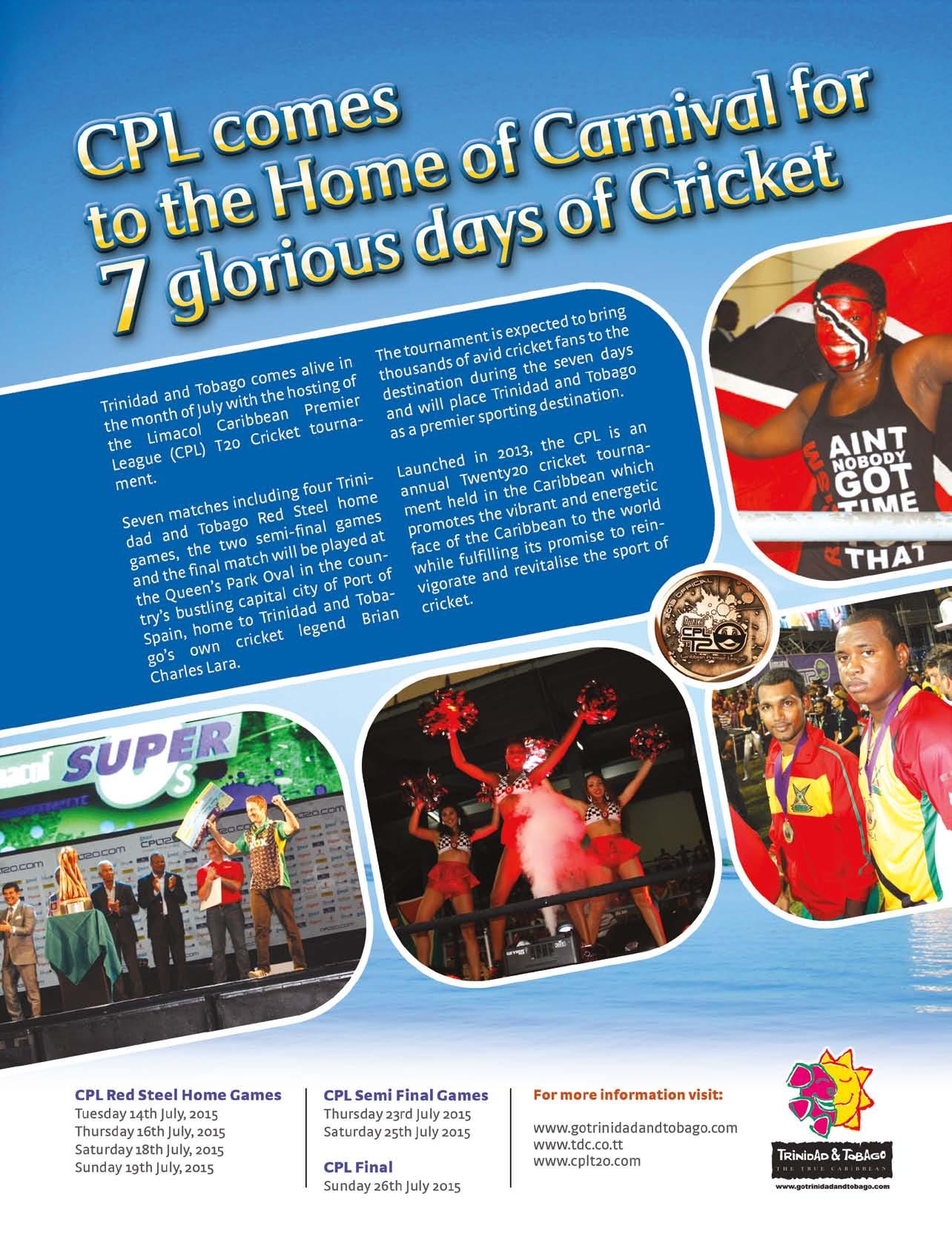

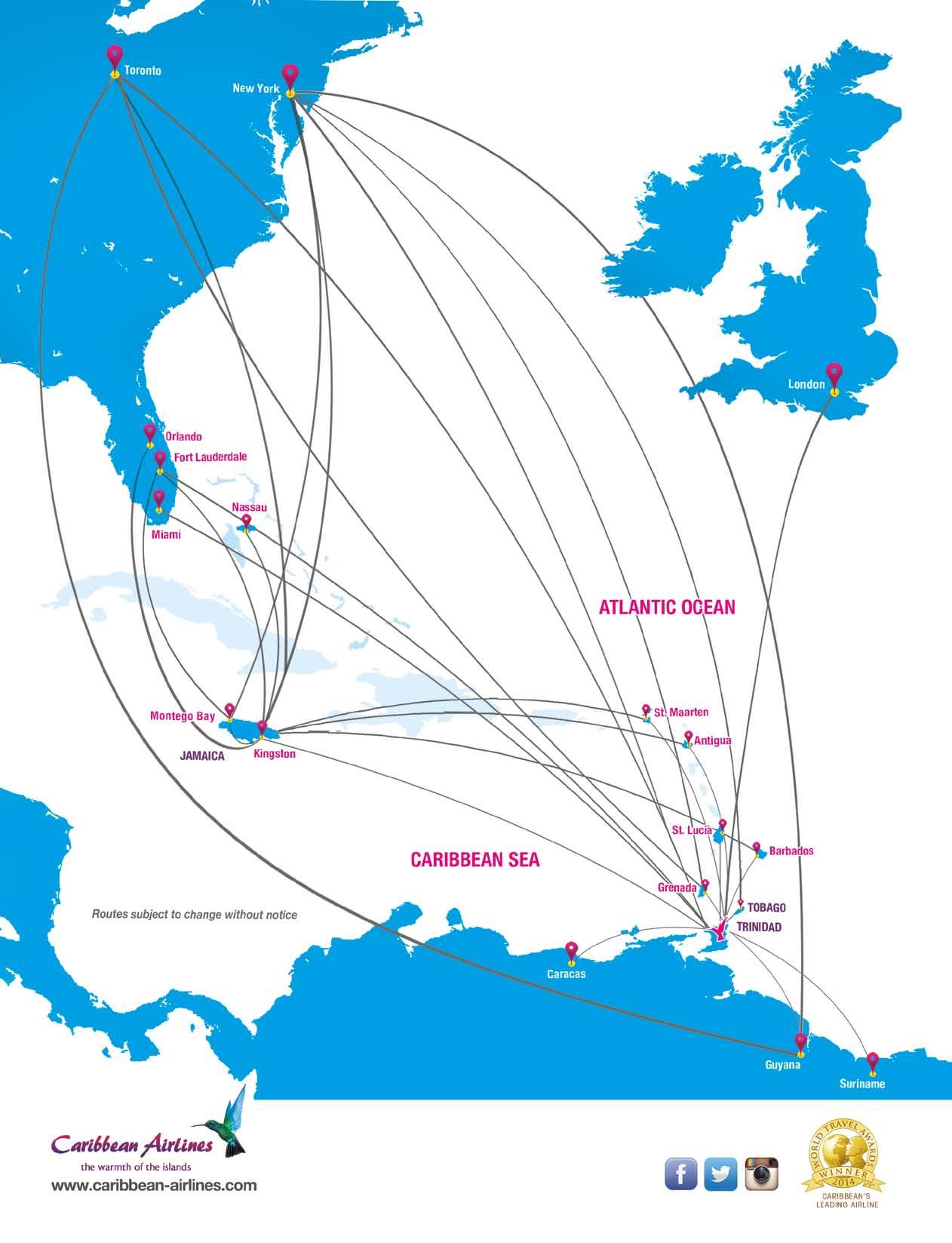

Welcome aboard! In our last issue, I declared 2015 as the Year of the Caribbean, and we are excited to be the Official Airline Sponsor for the 2015 Caribbean Premier League T20. The CPL is the newest addition to the yearly cricket calendar, and it will be a spectacular event, drawing some of the most talented cricket players and fans to the beautiful islands of the Caribbean. And who better to get the teams and supporters around the Caribbean?

Moving teams and fans throughout the region for the sport of cricket allows us to continue to serve our customers. This partnership represents the best that the Caribbean has to offer, and it’s a natural fit for both our brands. The CPL logo has been branded on our aircraft, so look out for the vibrant image when you head to the games.

Caribbean Airlines will also participate in Caribbean Week, which will be held in New York from 1 to 7 June, 2015. This is another event which highlights the diversity and vibrancy of the authentic Caribbean, organised by the Caribbean Tourism Organisation. We have partnered with the CTO to promote the sights, sounds, colour, culture, and unique experiences of the Caribbean.

I take this opportunity to wish the Legacy sailing team success with the “Operation Southman” expedition. The locally built yacht branded with the Caribbean Airlines logo, led by Reginald Williams and his crew, will attempt to establish a new national elapsed time across the Atlantic. Team Legacy will compete in Cowes Sail Week on the south coast of England in August, which provides Caribbean Airlines with a captive UK and European travelling audience of 10,000 sailors and 200,000 visitors daily over eight days of racing.

Our connections are expanding. I am pleased to announce that we have signed a new interline agreement with Emirates Airline, the world’s largest international airline. In addition to easy transfers at key airports such as London’s Gatwick and New York’s John F. Kennedy, this agreement creates an opportunity to offer through fares from the extensive Emirates network over London and New

York to Port of Spain, Georgetown, Kingston, and Montego Bay. As the co-operative agreement unfolds this year, we look forward to exploring even more opportunities and reach to the huge Emirates Airline network beyond Dubai, covering over 100 cities.

Our multinational Caribbean workforce has been enhanced with the orientation of nineteen trainees from Metal Industries Company and the University of Trinidad and Tobago into our Maintenance and Engineering department, a complement to our employee base of nationals from Jamaica, Guyana, and Barbados.

Additionally, we have developed a new marketing plan to create a centre of aircraft maintenance and engineering excellence for airline customers worldwide who are seeking quality aircraft maintenance facility services for their respective heavy maintenance needs. Caribbean Airlines has been completing heavy maintenance C-checks in-house on its Boeing and ATR fleets.

Caribbean Airlines team members are readily available to attend to your needs, even before you arrive at the check-in counter. Our teams are busy behind the scenes, preparing for the upcoming summer period. Our commitment to your safety is unrelenting.

We remain truly committed to treating you to a great flight today, and every time you choose to fly with us. We understand that you have a choice, so we appreciate you sharing this special journey with us.

We want to hear from you — give us your feedback on your experience at feedback@caribbean-airlines.com

Have an enjoyable flight and we look forward to serving you again.

Michael de Lollo Chief Executive Officer

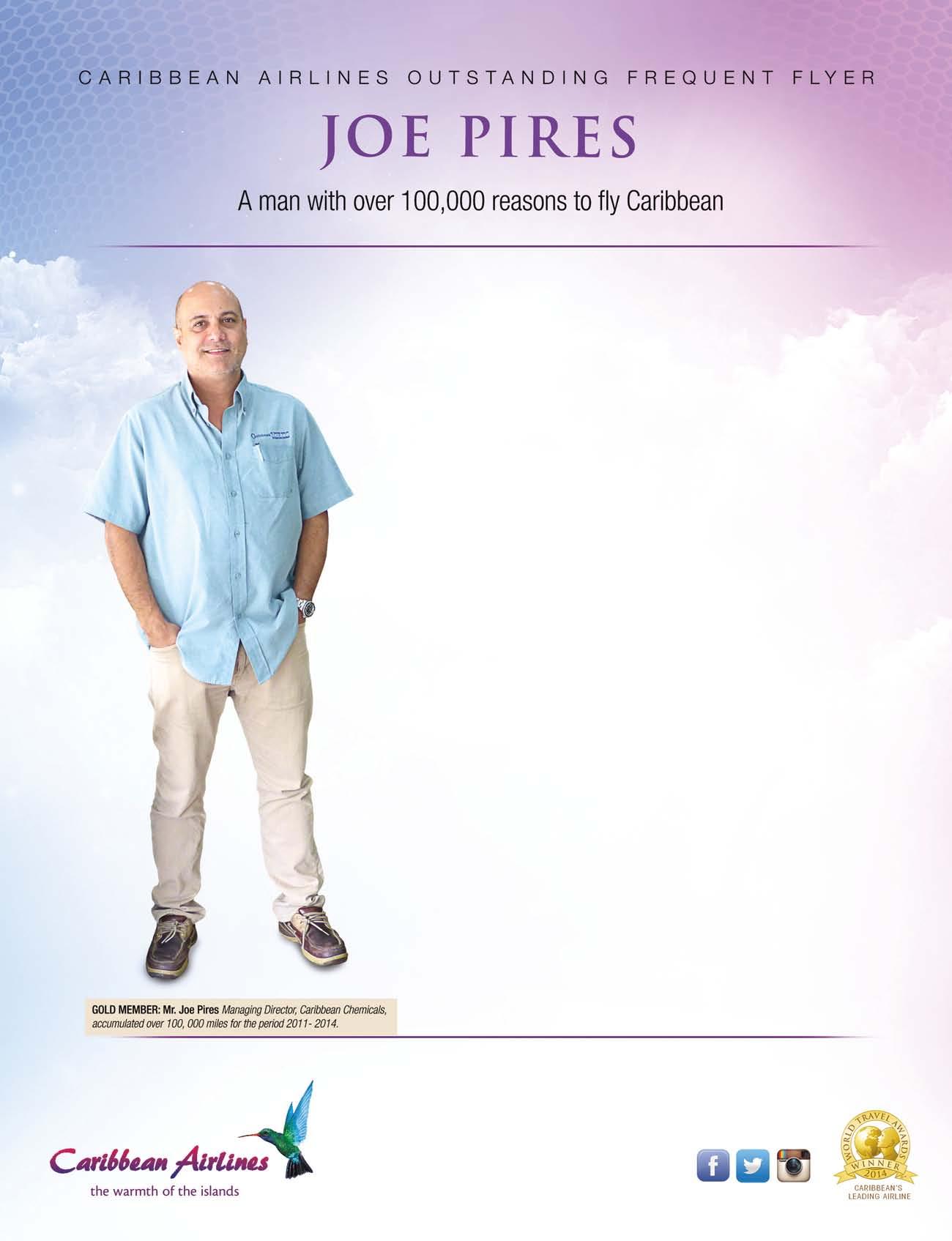

For Trinidadian businessman Joe Pires, home is definitely where his heart is. A “serial entrepreneur” by his own admission, he started his first business at age twenty-one, when he got the idea into his head that flavoured popcorn would be a bestseller, he would be the first to market. He launched his brand, Munchies Ltd, before realising he didn’t have enough capital. His father (Joe Pires, Sr., a successful self-made businessman himself) said no, “you want to start a business,” he told his son, “find the means to do it.” Every bank turned him down and Munchies Ltd never got off the ground, but the lesson was learned. Pires’s second business, Gardenland, which he opened when he was twenty-four, remained a successful venture until the day he closed it to take over the reins of Caribbean Chemicals, the company his father built from the ground up. He was then thirty years old.

He is still Managing Director of Caribbean Chemicals, which has expanded to Guyana, Suriname and Jamaica, and now also holds ownership or controlling interest in at least twenty-five other companies. “When I see a niche market that needs filling,” Pires says, “my first thought is ‘I can do that.’” And he usually does. Most of his businesses were born out of a need he himself experienced and couldn’t fill (at least not easily). His, was the first company to introduce the now-flourishing “skybox” business to facilitate online shopping, because he wanted to subscribe to a magazine that he couldn’t get in Trinidad. His business interests now range everywhere from boat building and communications, to nightclubs and

restaurants, and a host of others in-between. His personal mantra is “everything always works out for the best, even if it fails, so why not try.”

You might assume it would be difficult trying to reach such a person, and expect a fleet of staff to wade through on the way, but you’d be wrong. Pires is a literal “regular Joe’ — an open-necked shirt and sneakers are his office wear. All his staff call him by his first name and he’s accessible to them, his family, and his friends around the clock, no matter where in the world he is. His office door (when he happens to be in office) is always “open.”

Pires’s rigorous business schedule takes him from Trinidad and Tobago to the rest of the Caribbean, Miami, Latin America and South America, week in and week out. A CAL Boeing 737 is as familiar a mode of transport to him as his Land Rover — but he never wanted to live anywhere else but Trinidad. This is and will always be “home,” which he has invested a lot in. He plays as hard as he works and he plans his business trips to fall between Mondays and Thursdays, so that his weekends find him right here, in Trinidad with his people.

His favourite airport in the world is Piarco, because it’s “home.” Pires has many choices for air travel, but he chooses Caribbean Airlines, he says, “I genuinely find our people to be the friendliest of all when it comes to airline staff, as soon as I step in that lounge or on that plane, no matter where in the world I am, I feel like I’m already in my favourite place — home.”

We congratulate Joe for outstanding loyalty that truly goes the distance with us.

“I genuinely find our people to be the friendliest of all when it comes to airline staff, as soon as I step in that lounge or on that plane, no matter where in the world I am, I feel like I’m already in my favourite place — home.”

Your guide to Caribbean events in May and June, from Carnival in St Vincent to freediving in Bonaire

25 to 27 June • Warner Park Stadium

stkittsmusicfestival.net

The Caribbean’s cultural calendar is overflowing with music festivals, covering almost every musical style imaginable, from jazz and blues to reggae and dancehall, calypso to classical, salsa to zouk. But few have as eclectic a lineup as the St Kitts Music Festival, which turns nineteen this year. Since 1996, the festival has welcomed a galaxy of star regional and international artists — as diverse as Hugh

Masekela and David Rudder, Jimmy Cliff and Roberta Flack, Kenny Rogers and Busta Rhymes — and during the three days of the festival, the population of tiny St Kitts swells with visiting music fans.

How to get there? Caribbean Airlines operates regular flights to V.C. Bird International Airport in Antigua and Princess Juliana International Airport in Sint Maarten, with frequent connections to Robert L. Bradshaw International Airport in St Kitts

26 June to 7 July • venues around St Vincent carnivalsvg.com

The self-proclaimed “hottest Carnival in the Caribbean” runs for almost two weeks, from Fantastic Friday on 26 June — featuring the semi-finals of the national calypso competition — to Mardi Gras on Tuesday 7 July.

havana biennial

22 May to 22 June • venues around Havana bienalhabana.cult.cu

“Between the idea and the experience” — that’s the theme for the Twelfth Havana Biennial, the biggest and most prestigious art event in the Caribbean, and reliably the most controversial. With a focus on the Caribbean, Latin America, Africa, and Asia, the Biennial is arguably the most important international gathering of artists from the “global south,” and the recent relaxing of travel restrictions by the US government means an even larger contingent of star curators and gallerists from the “north” will descend on the Cuban capital this year, competing to spot the next round of major talent.

Along the way you’ll find all the events you’d expect from a Caribbean Carnival: soca, steel pan, J’Ouvert on Monday 6 July, and fetes galore.

“When we touch the road, we touch the road to party hard”: so said Vincentian soca star Gamal “Skinny Fabulous” Doyle in a Caribbean Beat interview last year. The former Vincy Mas soca monarch knows what he’s talking about. He’ll be a leading contender to reclaim the soca crown from 2014’s winner, Delroy “Fireman” Hooper, at the competition on Saturday 4 July, and whoever comes out on top, their songs are guaranteed to dominate the road on Carnival Monday and Tuesday.

Other key events in the Vincy Mas season:

Junior Carnival Parade

27 June

Junior Pan fest 28 June

steel and glitter (steelband competition finals)

Dimanche gras

2 July

5 July

Cuban artists will dominate the programme as usual. For the first time, there will be no central

15 to 22 June • Dwight Yorke Stadium

Son-of-the-soil Dwight Yorke heads the squad of international football legends — including former stars from UK clubs like Manchester United, Chelsea, Arsenal, Tottenham, Liverpool, and Aston Villa — preparing to face off with

exhibition area, and artworks will be spread out across the city. Keep an eye out for other Caribbean talent, including Jamaican Ebony G. Patterson, Barbadian Ewan Atkinson, Puerto Rican Chemi Rosado, and Tirzo Martha and David Bade of Curaçao, among others. The gossip behind the scenes will almost certainly be about the fate of Tania Bruguera, the star Cuban artist detained and released by the Cuban government in January this year, after staging an unauthorised performance.

select teams from the Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA) and a Caribbean All Stars side, at the first-ever instalment of this new tournament. Sixty-four players have signed up, including Liverpool legend Stan Collymore, and former Chelsea teammates (and top club managers) Roberto Di Matteo and Gus Poyet. Eight top teams will compete in the Legends six-a-side tournament, which is expected to reignite old team rivalries among the legendary names competing in Tobago’s laid-back and scenic landscape. “It’s been a while since I had a chance to strut my stuff back in Tobago,” says Yorke, the Legends ambassador,” and we will try to bring the trophy home for all my fans around our beautiful island and the world.” Young Tobago talent will also have a chance to shine, as Legends players visit schools and sports clubs around the island. Is the next Dwight Yorke waiting to be discovered in Pembroke or Parlatuvier, Carnbee or Charlotteville?

Magdalena Grand, Tobago’s premier oceanfront resort, strives to provide our guests with the ultimate in service during their stay with us. We are now offering guests VIP concierge service from Trinidad’s airport to the short Tobago commuter flight. Guests will enjoy personal service and be able to relax knowing they have made their connection.

When you arrive at the resort you will enjoy a welcome beverage and another personal welcome from our resort staff. range

The Magdalena Grand Beach & Golf Resort has 178 deluxe oceanfront guest rooms and 22 suites, all featuring breathtaking ocean views from large private balconies and terraces. There are 3 oceanfront swimming pools, a PGA designed 18-hole golf course, tennis, a PADI 5-star dive center, spa services, guest activities, a kids club and a variety of excursions, as well as a wide range of dining options.

make the most of may

[30 April to 10 May]

St Lucia Jazz and Arts Festival Venues around st lucia stluciajazz.org

Jamaicans Jimmy Cliff and Chronnix join Guadeloupean jazz pianist Alain Jean-Marie and Barbadian band Krosfyah at St Lucia’s major annual music event

[2 to 3 May]

IAAF World Relays thomas A. Robinson national stadium, nassau bahamasworldrelays.org

The world’s best sprint athletes, from over fifty countries, gather for the biggest international tournament devoted solely to relays

COURTESY GRENADA CHOCOLATE FESTIVAL

[8 to 17 May]

Grenada Chocolate Fest true Blue Bay Resort and other venues chocolate.truebluebay.com

[22 to 25 May]

Terre de Blues

grand-Bourg, Mariegalante terredeblues.com

The sixteenth annual blues festival on Marie-Galante, south of Guadeloupe, features Guy Vadeleux, Vasti Jackson, Mayra Andrade, and disco/ R&B legends Sister Sledge

Anguilla Lit Fest Paradise Cove Resort

This “literary jollification” brings Caribbean and international writers together to read and debate against a background of tropical sea blue

[9 to 13 June]

Jamaica International Reggae Film Festival

island Village, ocho Rios

A whole festival of films devoted to Jamaican music? Look out for features, documentaries, animated shorts, and awards for the best in show

[5 to 9 June, 13 to 17 June]

West Indies vs Australia

Windsor Park, Dominica, and sabina Park, Jamaica windiescricket.com

The Australia cricket team’s tour of the West Indies includes just two Test matches — a prelude to the upcoming Caribbean Premiere League tournament

[11 to 14 June]

Charleston Carifest

Charleston, south Carolina charlestoncarifest.com

June — Caribbean-American Heritage Month in the US — brings celebrations of all kinds, including this Caribbean-style Carnival in one of the country’s oldest cities

Blanchisseuse, trinidad

This Hindu observance, paying tribute to the Ganges and all the world’s rivers, reminds participants of their vital connection to nature

[17

Deepsea Challenge Bonaire

Plaza Beach Resort

Venezuelan freediving champ Carlos

Coste is the star attraction at this international competition for stronglunged divers. Will he break the world record again?

Experience international quality and service with a local flair at Guyana’s premier boutique hotel. Conveniently located minutes away from our capital city, Georgetown, Grand Coastal Hotel is the place to stay when travelling for business or pleasure.

Tel: 592-220-1091

Fax: 592-220-1498

www.grandcoastal.com reservations@grandcoastal.com

this year — are such time-consuming activities that she’s about ready to hang up her secateurs.

stephanie Royer tells me she can’t make it right to the top of her golden apple tree anymore, because she tends to come over a bit woozy. I feel rather light-headed just thinking about it. She’s seventy, though you’d never believe it as she strides effortlessly, machete in hand, up the steep muddy tracks of her terraced flower and vegetable plots, leaving me breathless in her wake. President of Dominica’s Giraudel and Eggleston Flower Growers Group for ten years, Stephanie cultivates flowers and sells arrangements for a living. Ambling around her elongated hillside garden of anthuriums, heliconias, ginger lilies, and rambling passionflowers, she says it’s high time someone else took charge. Organising fundraising events, overseeing enhancements to the Giraudel Flower House and Gardens, and putting on the annual Flower Show — which runs from 2 to 6 May

One contender for the role may be committee member Victoria Giraudel, whose one-acre cottage garden is bursting at the seams with sprays of colourful horticulture. Every inch, it seems, is inhabited by wildflowers, trees, and shrubs. A huddle of bottle plants catches my eye, and, as we stand chatting, they discharge their seed pods like corks popping from miniature Champagne bottles. Strolling between beds of pentas, azalea, agapanthus, and amaryllis, she pulls up occasional weeds from around celosia, fragrant tuberose, and star of Bethlehem. Begonias and caladium stretch long necks to the light, and salmon pink mussaenda blossoms, gloriosa lilies, and pandanus contribute to what is already a breathtaking backdrop of forestcovered mountain peaks and the Caribbean Sea.

This year’s flower show theme is “Love in Bloom,” Elizabeth Alfred informs me, as we meander the narrow pathways of her mature hillside garden. Like Stephanie and Victoria, Elizabeth and her sister Cybil are also members of the Flower Growers Group, and earn a living from the sale of cut flowers and arrangements. Operating on a much larger scale, their garden has also become a tourist attraction, and in the high season they host bus-loads of green-fingered cruise ship visitors. I tag along with a group who gawp wide-eyed at this visual feast and hang on Elizabeth’s every word, as she enchants them with snippets of homespun life in a Caribbean garden.

Giraudel and Eggleston are known by Nature Islanders as the “flower villages,” because they have supplied cut flower arrangements to both businesses and residents of Dominica’s capital, Roseau, for generations. Planted on the side of the Morne Anglais volcano, the villages look down on the town from a vertiginous height. The Flower Growers Group, born from a women-inagriculture movement, has few male members, though neighbours and nephews are all dragged into the fray in the frenetic weeks of preparations before the show opens. Stephanie, Victoria, Elizabeth, and Cybil coordinate activities, and despite the good intentions of early meetings, everything always happens at the last minute. It is customary this way, it seems, but miraculously it all gets finished in time for the pomp and protocol of the opening ceremony. Were it not for the love affair between the ladies and their delicate blooms, I wonder if any of this would ever endure. Indeed, the tremendous array of plants and flowers used for the show’s creative displays all come from the their own backyards. It’s a personal sacrifice that usually goes unnoticed and unmentioned.

“There should be more plants for sale this year,” Stephanie muses, as we share an old sofa on her porch, drinking sorrel and enjoying the sea view. “So we might be able to make a little money back this time.”

hhughh, hhughh . . . I gasp for air as I make my way through the run leg of the triathlon. I ask myself, why am I doing this again? No answer comes to mind as I contemplate the finish on this last leg of the race, broiling from within under the blazing Tobago sun. The only thing clear to me is that I must keep moving, must not give up, must cross the finish line.

In 2011, I joined the sport of triathlon, jumping in head-first with the Rainbow Warriors club. I was slow but determined, acquiring skill, “bad mind,” and flair. It was a welcome respite from the constant mental and emotional stress that came with completing a PhD thesis. I now had the opportunity to work my body in ways I had never done before. I knew I wouldn’t be competitive, being overweight and struggling to control cough-variant and exercise-induced asthma, but I didn’t care — I could now get out of my head, and enjoy the relaxed, fun, family atmosphere with just enough competitiveness mixed in to build motivation and excitement.

I was open to every event, and I didn’t mind coming in dead last — I was joyful at the finish. My first experience at the Rainbow Cup Olympic Distance Triathlon in Tobago was a moment of selfactualisation. Was I nervous? Oh, yes! But

the distance the sport of triathlon, with its run-swim-ride combination, is not the for faint-hearted. But Sue Ann Barratt discovers that even an asthmatic competitor can experience the thrill of victory — and the cheers of onlookers — at tobago’s Rainbow Cup race

from the reception at the start to the afterparty, I knew I could do “me” in a space that facilitated any athlete, from the most competitive to determined participants like myself.

Then, the following year, I decided to up the ante. I knew that my lungs would not allow me to pick up the pace, but I also knew I had the strength to go longer. My past experience at Rainbow Cup had given me confidence and a zeal for battle. It was a battle indeed. Coming out of the sea for the second lap of the 1,500-metre swim, a little voice said, “just stop.” But then I heard my friends, family, teammates, even strangers, calling out. “Go Sue, go Sue!” they screamed. How could I stop with such encouragement, even when the beach was near-empty, as most of the other racers had gone ahead of me? I had to go on, if not for me then for those who supported me with such dedication.

I had to go on when I jumped on the bike for eight laps, legs trembling and already exhausted, and I heard leading athletes urging me on: “Just keep going,

you looking strong.” I just couldn’t quit when a male spectator told me on every lap that he was waiting for me, he wasn’t leaving until I was finished.

I gasped my way through the run leg — truly a walk for me, really — and I crossed that finish line, praising the Almighty for taking me through. With tears in my eyes, I didn’t care about cameras or a photo finish — I just felt my heart bursting, not so much from exertion, but with gratitude for the support I got along the way.

A lady came up to me at the end and told me she was impressed — a big woman like me in an unforgiving tri-suit facing the demons of body image, athletic challenge, and hot, hot sun. I thanked her, sitting cautiously to rest my aching body, and humbled by each person who passed and congratulated me. Then I found the energy to party the night away with a group of people who were living life on their own terms, and loving doing it. Once again Rainbow Cup was a true mind-body experience: the place, the people, the vibe, calling my name, forever urging me to “Go Sue, go!”

The 2015 Rainbow Cup Olympic Distance Triathlon takes place on 13 June at the Turtle Beach Heritage Park in Tobago. For more information, visit www.rainbowcuptobago.com

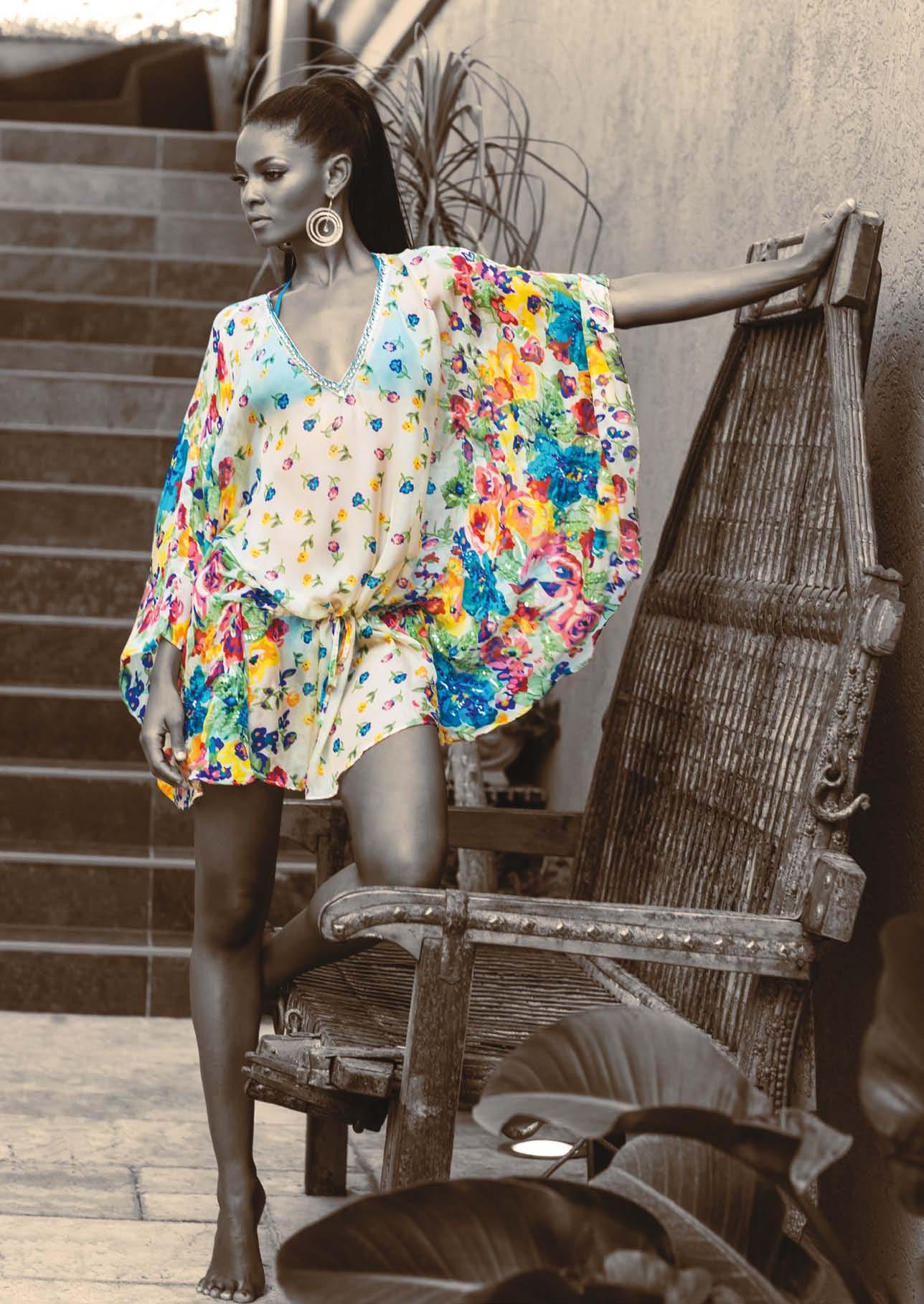

With “summer” right around the corner, now is the perfect time to hone your style for vacation days ahead. And designers Shayla Cox and Kimberley Angoy both provide collections — of jewellery and swimwear, respectively — that will stand out on any beach.

“I was experiencing a rebirth, mentally and spiritually,” says Cox of her transition from fashion merchandising to jewellery design. Originally from Ohio, this New Yorker’s journey began while working at a ceramic studio, where she learned the craft that would later become the basis of her architecturally beautiful jewellery line. She describes her work as a “quiet rebellion,” and explains that part of her self-discovery as a designer

stems from her family’s history, which includes her grandmother’s origins in Barbados. No piece is the same, which makes everything she designs absolutely worth having.

Savannah College of Art and Design alumna Kimberley Angoy also recently made a shift in career, from interior design to creating the swimwear line Suga Apple Swim. Her collection is the first among Caribbean designers to successfully master the Brazilian cut suit, and her love for bright colours, prints, and textures is infused throughout. Each suit has a unique detail that makes it fun and flirty. And up next? A line of fitness wear.

Alia Michèle Orane style.aliamichele.com

For more information on Shayla Cox’s pieces, visit shaylacox.com or email info@shaylacox.com

Suga Apple swimsuits can be purchased directly from the designer — contact her at sugaappleswim@gmail.com

oil and natural gas are the backbone of the trinidad and tobago economy — but how can citizens be sure the national petro-income is being accounted for and spent ethically?

THEthe new Extractive industries transparency initiative is a step in the right direction, reports Nazma

mullerIn a country where allegations of corruption are made almost every week, the Trinidad and Tobago Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (TTEITI) stands as a beacon of hope in the fight-back against white-collar criminals. T&T, the largest oil and natural gas producer in the Caribbean, has been involved in the petroleum sector for over a hundred years, and total receipts from these sectors accounted for TT$21 billion (uS$3 billion) — about forty per cent of GDP and eighty per cent of exports — in 2012, according to the TTEITI.

Oil and gas power T&T’s economy in more ways than one — the country’s natural gas is used to fuel eleven ammonia plants and seven methanol plants — and their annual output makes the twin-island republic the world’s largest exporter of ammonia and the second largest exporter of methanol. The Point Lisas Industrial Complex in Couva, central Trinidad, houses one of the largest natural gas–processing facilities in the Western Hemisphere, Phoenix Park Gas Processors Limited (PPGPL), as well as a subsidiary of PCS Nitrogen, the world’s largest fertiliser company.

The EITI is a global venture that

asks companies involved in extracting a country’s natural resources to voluntarily disclose the payments they have made to the government — which, in turn, declares how much it has received from the companies. An independent auditor then reconciles these receipts and the verified data is published in an annual report.

Forty-eight countries now belong to the EITI, and T&T, which has been a candidate since 2011, finally met the set standards and was given countrycompliant status last January — the first country in the Caribbean. The importance of the TTEITI was thrown into sharp focus within a month of T&T attaining country-compliant status, when

allegations of financial impropriety and mismanagement hit the oil company Petrotrin and the National Gas Company simultaneously.

The first the world heard of the EITI was from Tony Blair, former prime minister of the united Kingdom, when he announced its intended formation at a 2002 conference on sustainable development in South Africa. A formal launch was planned at the first EITI Plenary Conference in London, the following year, where T&T publicly announced its commitment to the initiative. However, when the first fifteen countries were admitted to EITI membership in November 2007, T&T was not among them. It was not until September 2010 that the country set up a tripartite steering committee, comprising eighteen representatives of the state, the private sector, and civil society (six each).

In March 2011, T&T became a member of EITI, but it took the country four years of intensive work to gain compliant country status. The TTEITI secretariat, which is housed at the headquarters of the Ministry of Energy and Energy Affairs, came in for high praise from Clare Short, chair of EITI, when she made the announcement at the Energy Chamber’s Trinidad and Tobago Energy Conference in January 2015. “The EITI puts information about the energy sector in the public domain so that analysts, academics, the media, and the public are more informed,” she said. “Trinidad and Tobago is now a regional leader and is expected to carry the mantle. However, you must maintain the standards you have now set.”

Solomon Ioannou, the European union’s programme officer in the Sector Policy Support Programme to the environment sector in T&T (the Eu is a donor to the TTEITI), is impressed by how quickly the country achieved compliant status, and praised the steering committee for their hard work and commitment. “Future possible enlargement of this initiative,” he said, “could include the mining sector, among others.”

The E u aims at “greening” the EITI in T&T by incorporating environmental aspects into its scope. As it is, illegal quarrying of soil aggregates in the Northern Range of Trinidad has had a devastating effect on the landscape and ecology of the sites. Dr Mark Thomas, CEO of the Cropper Foundation, one of the civil society representatives on the steering committee of the TTEITI, warns that “Trinidad and Tobago is second in the world in terms of per capita greenhouse gas emissions, meaning that the country and its energy sector make an unusually high contribution to global climate change. This will come back to bite us, because, as small islands, we are really vulnerable to the effects of climate change, like sea level rise and more intense dry seasons.

“The poorly regulated mining sector also creates huge environmental problems by removing forests, silting rivers, and so on. So, while financial transparency in our extractive industries is good, it cannot be the only thing. We can only solve the environmental problems caused by our extractive industries if we know the sizes of those problems, and this will be achieved only when there is environmental transparency as well.” n

The narrator in one of St Lucian Vladimir Lucien’s poems stoically avows, “I can close my mouth over opinions screeching like chalk. I can cut the dread talk and learn how to peck past the breadline.” We can be grateful that the poet himself swears no allegiance to these commandments — instead, the whole of Sounding Ground , Lucien’s debut collection, affirms a steady eye, and a poetic register intent on cataloguing the whole: whether it be life within an island, or the worlds within both beloved and distant figures.

It is not indebtedness that whispers in between the lines of Lucien’s symbolic mapmaking, but a sense of ancestry, a certain fealty to cultural bloodlines that have bloomed and taken root within our region. Some of these are overt and outstanding: “Black Light”, a praise and remembrance poem for Walter Rodney’s industry of resistance, is immediately followed by a meditation at the grave of

The Sea Grape Tree, by Gillian Royes (Atria Books, 368 pp, ISBN 9781476762388)

“You’d never think Jamaica was once British,” writes a reclusive painter, in the early chapters of Gillian Royes’s third Shadrack Meyers novel. Her email back home continues, “It has a character all its own. It’s loud, crude, beautiful, and utterly unpredictable.” In the artist’s bewildered musings lie the distilled ambitions of Royes’s entire Shad series: to portray Jamaica and its people as real, non-commercial entities, and to render the island in all its outrageous splendour. This she achieves through her central character of multiplying narrative delights, Shad himself. An unsuspecting Jamaican proletariat Sherlock, Shad’s personal woes are by turns gently humorous (witness his prolonged dread over tying the knot with Beth, already his beloved wife in all but legal decree) and reflective of society’s larger malaises. Through this plucky, resourceful everyman of a hero, the novel glows optimistically, while refusing to peer at Jamaica from the glossy pages of a travelogue.

C.L.R. James. Other poems declare the subjects of their twinned worship and critical focus more subtly, identifying them as intimate luminaries whose valours can be sung from the dinner table as well as on a podium. Among these are the father in “A Picture”, who “use to wear an afro in the 70s — black champagne on his head . . . his eyes averted from the dark-dark Ages, from the bad breath of History yellow pages.” Lucien breathes life into the fears and strengths of mothers who suffer lamentations for the loss of their children’s faith, who wait into the long nights for their wayward sons to strike a path back home.

What moves most about this collection is its lack of apologies over linguistic authenticity. Lucien’s poems straddle English and French Patois, delivering in well-studied turns the rhythms and realities of a St Lucia that is both proud island and a whole world unto those who know it best.

See me here: A Survey of Contemporary Self-Portraits from the Caribbean, edited by Melanie Archer and Mariel Brown (Robert & Christopher Publishers, 224 pp, ISBN 9789769534476)

Whether an assembly of lies, or a chorus of truths transmuted onto canvas, the art of the self-portrait is revelatory, even (or perhaps especially) when it conceals. In See Me Here, twenty-five Caribbean visual artists present themselves — in stasis, in blurred kinetic motion, in full regalia and perhaps, above all, inconsistently — for their own selfperception as much as the audience’s. The vision of co-editors Archer and Brown suggests that in this inconsistency, a ledger of the body in Caribbean space is allowed to emerge. From the fabric and paint of Annalee Davis’s Creole Madonnas , to the wire, paper, and fabric of Susan Dayal’s Costumed Series, these personal embodiments evoke the provocative tussle with the polemical, and show whole worlds within an archipelago of possibility.

Indian-Caribbean Test Cricketers and the Quest for Identity, by Frank Birbalsingh (Hansib Publications, 250 pp, ISBN 9781906190743)

Literary scholar Frank Birbalsingh reminds us in this investigative and illuminating report that the West Indies’ best-beloved game does not exist without complication. Amid our inheritance of post-colonial divisions and exacerbated contemporary tensions, the writer seeks to shine light on the accomplishments of both extraordinary and factotum-level IndoCaribbean cricketers. Cogent chapters are devoted to the industry’s big six, beginning with Sonny Ramadhin and closing on Ramnaresh Sarwan. The latter’s sanguine declaration that “cricket has taught me a lot about how a simple sport can unite so many West Indian people” is the study’s emotive cornerstone. At every turn, Birbalsingh strives to show cricket’s inclusiveness, its power to silence racially prompted hue and cry with a series of stunning innings, served up by our region’s multicultural sons.

(Everything Slight Pepper, 44 pp, ISBN 9789769535008)

Boasting a colour palette as bold and bright as Grande Riviere beach at midday, the story of young leatherback turtle Hatch leaps with exuberance into young seafarers’ hearts. Alkins’s tale of this precocious tiny adventurer begins with the maritime journey made by his mother across thousands of North Atlantic miles towards the welcoming harbours of Caribbean waters. Her dangerous travels in search of safe spawning grounds, and the subsequent trials of Hatch and his siblings, are interwoven into this childhood primer on teamwork and resilience. “Just put one flipper in front the other. We’re almost there,” Hatch reassures a few of his slower-footed siblings, as they race towards the sea. Gaiety and crusading mirth mark the pages of this successful juvenile introduction to the life-cycle of one of our most endangered circumglobal species.

Reviews by Shivanee Ramlochan, Bookshelf editor

Brooklyn-based steel pannist Garvin Blake at long last follows up his 1999 debut album Belle Eau Road Blues with his new paean to pan jazz music, Parallel Overtones . The album is described as exploring “the synergy between pan, calypso, and jazz,” which it does with sure-handed skill. Balancing a repertoire between jazz standards and calypsos, Blake stealthily makes the case for renewed efforts of Caribbean pannists to record new music for the instrument. Vincentian keyboard stalwart Frankie McIntosh shares co-production along with songwriting and arrangement credits, making this album a showcase for the art of the Caribbean piano, with a sense of swing found only in hot latitudes. Kaiso-jazz classic “Fancy Sailor” sashays along at the steady chip of a slow lavway, while “Body and Soul” waltzes effortlessly to ably feature Blake’s quintet of players as soloists. The steelpan jazz oeuvre, while notably small, is emboldened by the addition of this well-produced album.

David Rudder represents a key link between old-style calypso and modern soca in the twenty-first century. A contemporary master of both genres, Rudder showcases that bridge on his new album Catharsis with music that is modern and lyrics that “turn a woman’s body into jelly.” Calypso is a lyricist’s and singer’s art, and here Rudder proves that he is unparalleled in the art of the metaphor to bring relevance to any topic, whether local or international. In “Long Walk Home” he sings of “race and America” using Nelson Mandela’s autobiography title to effect a broader perspective. On “Brooklyn Retro” Rudder recounts the essential sights and sounds of Caribbean-American existence of yore in the New York City borough. The word “catharsis” is defined as a relieving of emotional tensions — through music, for example — and on this album one can sense joy and celebration, anger and displeasure, reflection and awe. Rudder’s emotional release is food for the listener’s pleasure.

At the end of the 2015 Trinidad Carnival season, Machel Montano — now in his thirty-third year as a professional soca artist — effectively “owned” the festival by winning both the Soca Monarch and Road March titles. “Like a Boss” was an apt name for his hit single, included here, as he channelled his energies beyond simply making songs for Carnival. It’s not just business as usual. Montano’s new mission is to win a Grammy award, and he’s also declared a new persona — the still young performer has re-invented himself and his brand as Monk Monté, thus supplying the title of this new album of a dozen songs that dominated Carnival 2015. Here he teams up with Grammy-winning songwriter Angela Hunte on “Party Done” to deliver the message that once you have this Montano/Monté album, all other considerations are, in effect, over. Modern soca music is transforming, and Monk Monté may be its new pacesetter.

Northern Caribbean islanders, our Leeward Island “cousins,” have their own perspective on the regional music scene. Anguillan Natalie (Richardson), born in the US Virgin Islands and now resident in Florida, epitomises the young “upisland” scene with the release of her debut single “Perfect”. She is part of the new cadre of island artists who live in the metropolitan diaspora seeking success there, yet have their identities planted firmly on island terra firma. Musically, this smooth R&B groover signals that the island vibe of native Caribbean music has given way to a more international influence. Lyrically, youthful admonitions dominate — “If this love can’t keep us together / Then tell me what I want to hear / Tell me that I’m perfect” — suggesting that the headspace young people occupy here in the islands is in need of emotional fulfilment.

Reviews by Nigel A. Campbell

Reviews by Nigel A. Campbell

The answer to the first question is easy. That person is Paul Carmichael, and he’s the thirty-five-year-old Barbadian executive chef at Má Pêche, one of the jewels in the crown that is Momofuku, the famed group of restaurants founded by chef and restaurateur David Chang.

Momofuku began as the Momofuku Noodle Bar in New York’s East Village in 2004. That restaurant — and in particular its signature dish, to-die-for pork buns — put Chang on the Big Apple’s culinary map, and its success led him to unfurl several other establishments in the city under the Momofuku name, with Má Pêche opening its doors in 2010. Momofuku is Japanese for Lucky Peach; it’s also a tribute to Momofuku Ando, inventor of the ramen noodle — and, perhaps, it’s also meant to echo an English word you wouldn’t say in polite company. Several Michelin-guide and New York Times stars later, the brand has gone international, and counts among its outposts several in Toronto and one Down under, in Sydney.

The food at all of Momofuku’s restaurants can be said to have its roots in “Asian cuisine,” that well-worn, catch-all term lacking in nuance (and political correctness). “Eclectic” is another handy (and hackneyed) word of some use in describing the Momofuku style, but it’s the dim sum–inspired communal dining experience found at all its establishments, with passed plates and à la carte dishes meant for sharing, that best typifies the Momofuku experience.

It’s early evening in New York City, and you’re in a buzzing restaurant with friends for an informal dinner. As you sip your ginga ninja — a sublime, warming cocktail of Japanese whisky, ginger, and lime — you scan the menu for the choices on offer. In between dishes like creamy calamari chowder and duck sausage, your eyes alight on this: “Pan-fried whole boneless porgy — my dad’s hot sauce, fennel, lime.”

Questions, of course, are immediately forthcoming. Chief among them concerns the identity of the creator of the menu, and in particular this pronoun-personalised sea-bream dish. Who has taken their father’s fiery capsicum concoction and placed it on the menu of a chic midtown Manhattan eatery? And is it really their dad’s?

u ltimately, of course, each place is its own gastronomical beast, including Má Pêche. When it opened, the official nod was to French-influenced Vietnamese cooking — Má Pêche translates from Vietnamese-French creole as Mother Peach. Yet, since taking over from original executive chef Tien Ho in 2011, Carmichael has steered the restaurant in an altogether different direction — which, naturally, includes some Caribbean detours. Such dishes have included classic Barbadian fare like barbecued pigtails (paired with scrambled eggs) and souse (pickled pig’s parts) — the latter given an ingredient makeover, with lobster, green bananas, and cucumbers getting the pickling treatment, and scotch bonnet peppers tossed in to liven things up.

Pigtails and souse were among the dishes of Carmichael’s childhood, which he spent in a food-oriented family split between

how did a Bajan with a love for home cooking end up as executive chef at one of new york City’s most celebrated restaurants? Jonathan Ali meets Paul Carmichael, and hears his storyPhotography by gabriele Stabile, courtesy Má Pêche

the Barbados parishes of St Peter and St James. “I spent a ton of time growing up with my great-grandmother and my grandmother, and they were both very, very good cooks,” the amiable and forthcoming chef says from his busy restaurant. “They would sell food — [blood] pudding and souse. Sweetbread on Saturdays. People would come from all over to buy.”

The cooking bug bit him early. “My mom recently sent me a picture — I was on a stool making bacon and eggs at age three. I always wanted to cook. It’s the only thing I’ve ever really, really enjoyed doing. I was always cooking for my parents, for my siblings, friends. I even got some jobs as a kid in school making pizza.”

School wasn’t where he wanted to be, though, and at fifteen he tried to convince his parents to let him go to Puerto Rico to cook at a restaurant there. unsurprisingly, they said no (“Parents gotta do what parents gotta do”), but Carmichael’s father, a bartender at the renowned Sandy Lane Hotel, offered to get his son an after-school job in the resort, thinking the rigours of a top-flight restaurant environment would see Carmichael pack it in after a week.

Carmichael père misjudged his son. “I stayed there a year and a half,” Carmichael says smiling. In addition to learning invaluable cooking techniques from some of Barbados’s best professional cooks, Paul learned in Sandy Lane’s hallowed kitchens — and at The Cliff, the restaurant he worked at subsequently — the core values that have guided him through his career thus far: “Give one hundred per cent. Don’t complain. Stay humble.”

After graduation, Carmichael further acceded to his parents’ wishes by taking a degree in computer programming from Barbados Community College. Once that was dispensed with, however, he headed promptly to the united States, and the prestigious Culinary Institute of America in upstate New York. In between classes, he would dip into the city, to check out the restaurant scene and possible places of employment.

This led him to an apprenticeship at Aquavit, the Swedish restaurant then helmed by twenty-six-year-old Ethiopia-born wunderkind Marcus Samuelsson, who was committing delicious culinary crimes by using Asian ingredients in his traditional Scandinavian dishes. Did Samuelsson’s ethnicity play any part in Paul’s decision?

“I didn’t even know Marcus was black until I walked into the kitchen,” Carmichael says. “It was never about colour for me, it was always about skill. I never held myself back because I was the only black person in a place. It was always, ‘Hey, am I good enough to be here, or am I not, skill-wise?’”

After graduation, Carmichael returned to Aquavit. It was the turn of the millennium, a time when the New York restaurant scene was starting to capture the public’s imagination, and chefs began to be fêted like rock stars — a period bottled by one-time celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain in his vivid best-selling memoir Kitchen Confidential. Over the coming decade, Carmichael paid his dues at a number of restaurants in the city, ending up under executive chef Wylie Dufresne at WD-50, “the first restaurant I cooked in where I felt I had a voice.”

Ten years in the New York cauldron led Carmichael to seek a change. He headed back to the Caribbean and to Puerto Rico, where he’d originally intended to go as a teenager. He eventually became executive chef there at the Pearl restaurant — but then New York, in the personage of David Chang, came calling again.

Carmichael had first met Chang back in his Aquavit days, and from time to time the Momofuku man would ring him up in Puerto Rico to see if he was ready to return to the centre of the culinary universe. Finally, with Má Pêche set to open, Chang called one more time. This time Carmichael took the plunge.

On its opening, Má Pêche was anointed with two out of a possible four stars from The New York Times. Not long afterwards, the day came when Carmichael was offered the position of executive chef. “It was scary. It took a long time to make the decision,” he says. “But I’m glad I made it, glad I didn’t back out.” He remembers Chang telling him, “Pauly, it’s yours, do what you will.”

Carmichael took those words to heart. Finally, New Yorkers would get to taste his true hand. In addition to the Barbadosinspired dishes that have been served at Má Pêche, the cuisines of other islands have also graced the restaurant’s vaunted tables. These include Paul’s take on Jamaican jerk chicken wings (arguably the gateway food to Caribbean cooking), and, in a nod to his Puerto Rico days, a DIY mofongo, with a mortar and pestle for patrons to gleefully pound their plantains, garlic, and pork together.

Yet, as diverse as Carmichael’s dishes can be, it’s his finely honed culinary “voice” — which he speaks of much in the way a writer might speak of theirs — that ties together everything he does. “You’ve got to find a voice, and you’ve got to use that voice in a way that people can understand, otherwise you’re just yapping.”

That voice, of course, is grounded in the solid, unpretentious food of his childhood, the food he first loved and to which he always comes back. “I can never forget the first time I had a barbecued pigtail. Or black pudding and souse. Or the first time my mom made me fish cakes and bakes,” Carmichael says, with a Proustian air. “The beauty about being a cook is that you get to give that feeling to somebody else, a version of that thing that they perhaps never thought could be that good.”

And that hot sauce that comes with the porgy? “It’s my version of my dad’s hot sauce,” he confesses. “I like to call it New York hot. It’s not as spicy as my dad’s hot sauce. I have a bottle of that in my fridge at home.”

42 Panorama ready for their closeup

54 Backstory dubbing is a must

60 showcase two poems from Coming Up Hot

62 snapshot the anti-expected

DJ Gabre Selassie, founder of Kingston Dub Club

DJ Gabre Selassie, founder of Kingston Dub Club

It was sixty-five years ago that Cyrano de Bergerac was released, a film that would make Puerto Rican actor José Ferrer the first Caribbean person to win an Oscar (for best actor in a leading role, 1951). He also won a Golden Globe, and a Tony award for the Broadway production, and ultimately donated his Oscar trophy to the university of Puerto Rico. Born in 1912, he would earn more Oscar and Emmy recognition in his career, and effectively clear the way for a generation of Caribbean actors born after him who would command American and British stages and screens — breaking new ground, and some records, along the way.

Ferrer’s homeland of Puerto Rico is the birthplace of some of the most dynamic performers in film and television history. Exactly ten years after Ferrer’s win, legendary actress Rita Moreno became the second Puerto Rican to win an Oscar (and a Golden Globe), as best supporting actress, for her role in West Side Story She is among just twelve individuals worldwide, and the first Hispanic, to have won all of the Oscar, Grammy, Emmy, and Tony awards. Notably, when that list is

extended to include winners of honorary awards, another Caribbean-American star — Harry Belafonte — is among the prestigious number.

Four years older than Moreno, Belafonte was born in 1927 in Harlem to a Jamaican mother and a Martiniquan father. An actor, singer, songwriter, and activist, he first appeared on the silver screen in films like Carmen Jones and the controversial Island in the Sun, filmed on location in Grenada and Barbados. His album of calypso and mento recordings, Calypso , was released in 1956. Now eighty-eight, and considered a living legend, Belafonte counts three Grammys, an Emmy, a Tony, Kennedy Centre Honours, a u nited States National Medal of Arts, and the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award among his many accolades.

There was another very notable birth in 1927, when Sidney Poitier — though raised in the Bahamas to Bahamian parents — was born in Miami. Poitier would become the first African-American, and third Caribbean man or woman (after Rita Moreno) to win an Oscar. In 1964, he took both the Golden Globe and the

you see their familiar faces on the screen, but perhaps you don’t always catch their accents. Caribbean acting talent has been infiltrating h ollywood for decades, from blockbuster movies to hit t V shows to

indie productions.

Caroline Taylor takes a look back at an earlier generation of actors who made it big on stage and screen — and profiles some of the heaviest hitters among the current generation

Academy Award for best actor in a leading role for his performance in Lilies of the Field. An actor, director, author, and diplomat, Poitier is one of the most celebrated artists of his generation, with recognition that includes a knighthood, Kennedy Centre Honours, the u S Presidential Medal of Freedom, and numerous lifetime achievement awards.

Esther Rolle was also born in Florida to Bahamian parents, just a few years earlier than Poitier, in 1920. A theatre, film, and TV actress, dancer, and singer, she aptly became best known for her role as Florida Evans on 1970s uS TV series Maude and its spin-off Good Times ,

Dozens more Caribbean-born and –descended performers have made their mark in hollywood, continuing the tradition of winning top industry prizes and starring in popular films and tV series

The Orchid House, directed by Trinidadian Horace Ové. After she died of leukaemia at just fifty-seven, Sinclair’s ashes were scattered in her hometown in Jamaica.

a role for which she was nominated for a Golden Globe. She made history in 1979 by winning the very first Emmy for outstanding supporting actress in a limited series or special, for the TV movie Summer of My German Soldier

Twelve years later, Jamaican actress Madge Sinclair (born in Kingston in 1938) made more Caribbean Emmy history, winning for best supporting actress in a drama series (Gabriel’s Fire), and receiving another Emmy nod for her role in the TV miniseries Roots . The voice of Simba’s mother in The Lion King film, she notably performed in the uK miniseries adaptation of Dominican Phyllis Shand Allfrey’s novel

Further south in the island chain, the multi-talented Geoffrey Holder — who passed away in 2014 — was born in Trinidad in 1930. Holder conquered stage and screen, featuring in films like All Night Long, Annie, and Boomerang; narrating Charlie and the Chocolate Factory ; playing James Bond henchman Baron Samedi in Live and Let Die ; and becoming 7 up’s “uncola” spokesman in the 1970s and 80s (later reprising the role for an appearance on uS TV show The Celebrity Apprentice) An actor, choreographer, director, dancer, painter, costume designer, and singer, his accolades included two Tony awards and a Guggenheim Fellowship in fine arts.

Since those defining moments in the 1940s onwards, when these trailblazing artists from the region first appeared on global screens, dozens more — both Caribbean-born and children of Caribbean immigrants, a majority of them women — have made their mark, continuing the tradition of winning top industry prizes and starring in popular films and TV series. We profile just a few of them in the following pages, with extended coverage — including candid interviews — on our website, caribbean-beat.com

Born in Britain in 1967, to an Antiguan mother and St Lucian father

Jean-Baptiste made her mark early in her career by snagging an Oscar nomination for supporting actress in Secrets & Lies in 1996, becoming the first black British (or black Caribbean) actress do to so. An actress, singer-songwriter, writer, director, and composer (she wrote the score for Mike Leigh’s film Career Girls), she’s perhaps best known for her roles on the uS TV series Without a Trace, the u K series Broadchurch, and films like last year’s RoboCop

On her Caribbean roots: JeanBaptiste was appointed a tourism ambassador for Antigua and Barbuda in 2007, and believes the islands are perfect potential film and music video locations. Proud of her Caribbean heritage, she says: “It has informed who I am and how I see the world. A deep love for my culture, firmly grounded in family and tradition, keeps things in perspective for me. Family first, always. I still have family back in Antigua who I visit whenever I’m there,” she continues. “I think there is a sense of community among Caribbean actors in film and TV. And though it might not be that we all hang out, there is definitely a sense that we are from the same tribe, a sort of shorthand.”

Joseph Marcell: Born in St Lucia, he is best known for US TV series The Fresh Prince of Bel Air (co-starring with three actors of Trinidadian heritage) and films like Cry Freedom. He plays influential Trinidadian writer C.L.R. James in Trinidadian director Frances-Anne Solomon’s upcoming film Hero

Born in the uS in 1977, to a Jamaican mother and American father

Her iconic Emmy- and Golden Globe–nominated role as Olivia Pope in uS TV series Scandal has made Washington a household name. This actress and activist is the first black female lead in an American network TV drama since 1974. Other notable screen appearances include Save the Last Dance (starring GuyaneseAmerican actor Sean Patrick Thomas), The Human Stain, Ray, The Last King of Scotland, the Fantastic Four films, For Coloured Girls, and Django Unchained. She was listed as one of the hundred “most influential people in the world” by TIME magazine in 2014.

more stars of Jamaican heritage:

Dulé hill (Jamaican parents): best known for roles on US TV series The West Wing (for which he received an Emmy nomination) and Psych.

Delroy lindo: Born in England to Jamaican parents, he’s best known for film roles in movies like Malcolm X, Get Shorty, Ransom, The Cider House Rules, and Gone in 60 Seconds. He was also nominated for a Tony Award for Joe Turner’s Come and Gone.

Born in Guyana on Christmas Day 1962, as Carol Christine Hilaria Pounder, and grew up in the uS and the u K

Currently appearing in the uS TV drama NCIS: New Orleans , Pounder is also known for her past roles on ER (for which she received one of four Emmy nominations), The X Files, Law & Order SVU, The Shield, and Sons of Anarchy, and in films like Face/Off, RoboCop 3, Prizzi’s Honour, Avatar, and Bagdad Café. She also starred in Home Again, a movie filmed in Trinidad in 2012 (an island she has visited with friend Lorraine Toussaint). Pounder nurtures emerging African and Caribbean diaspora visual artists through the Pounder Kone Art Space in Los Angeles and the Musée Boribana in Senegal, co-founded with her husband. She received an honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from her alma mater, Ithaca College.

On her Caribbean roots: “Having left Guyana so young, one would think it was long left behind in my lifestyle,” she says, “But my parents never lost what they brought with them, and I was always the most curious in my family to go back and reconnect with what I remembered of Versailles Estate. I made my mother join me on one of my trips to Guyana . . . I sat and listened to Ole Haig stories, ate black cake, sugar cake, curry and roti, drank mauby and ginger beer. I revisited all I remembered from childhood.

“The impact of these journeys has been indelible, and holds me closer to a country I now rarely see but never forget and always claim . . . Having lost my mother, I’ve also lost many connections to Guyana, but not the Guyanese people, who seem to be scattered to the four winds . . . We cross paths enough for our presence to be known.”

in Puerto Rico in 1967,

Beginning his career with bit parts on TV playing the stereotypical Latino drug dealer, del Toro graduated to playing a James Bond villain in License to Kill (still the youngest actor ever to do so), and popular and critically acclaimed films like China Moon, The Usual Suspects (considered his breakout performance), Basquiat (about the Haitian- and Puerto Rican–American painter of the same name), Snatch, 21 Grams, Sin City, Guardians of the Galaxy, and the title role in Che. He joined the ranks of a handful of Caribbean actors (and became the third Puerto Rican) to win an Oscar, Golden Globe, and other awards for his supporting role in Traffic, in which his character predominantly spoke a language other than English (most of his lines were delivered in Spanish). Coming up? A film with maverick director Terrence Malick.

On his Caribbean roots: On receiving a lifetime achievement award last year, del Toro said: “I want to dedicate this award to the piece of land where I come from, where I was born, where I learned to throw rocks and had them first thrown at me, where I learned to take risks, and where I learned not to do things just to do them.”

Rosario Dawson (Puerto Rican mother): known for Men in Black II, the Sin City and Clerks films, Rent, Alexander, Seven Pounds, Unstoppable, and the new Daredevil series.

Acclaimed for her performance in the hit series Orange Is the New Black , the Juilliard-trained actress — whom Caribbean Beat interviewed back in 2008 — is also known for roles on uS TV series Forever, Saving Grace, Any Day Now, The Fosters, Friday Night Lights, Crossing Jordan, Ugly Betty, and Law & Order, as well as films like Hudson Hawk, Dangerous Minds, The Soloist, Middle of Nowhere, and the recently released Selma, in which she grippingly played iconic civil rights activist Amelia Boynton Robinson. These days, Toussaint is focusing more on producing, with an eye for projects that are Caribbeanbased, and a desire to invest in Trinidad and Tobago’s film industry and develop young acting talent.

On her Caribbean roots: Toussaint returns to Trinidad regularly, and has hosted workshops for developing filmmakers and actors back at home through the national film company. She sees no reason her homeland can’t be the mecca of the film and theatre industry in the Caribbean. Toussaint has said that her Trini roots, and identifying as a Caribbean woman, have served her well. Being from the Caribbean is “an empowering perspective on the world,” she says, “coming from a place where being a person of colour doesn’t render you a minority. To be part of the majority as a person of colour is very important, so I keep bringing [my daughter] home. So that she’s got roots there . . . My daughter considers herself a Trinidadian. I am glad we’re a part of this.”

Another star of Trinidadian heritage:

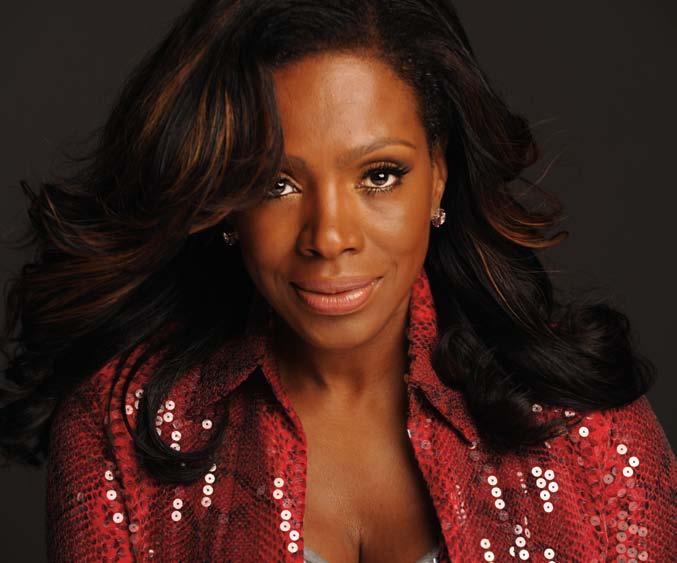

Jackée harry (Trinidadian mother): best known for US TV series like Sister, Sister (with Tia and Tamera Mowry, who are of Bahamian heritage) and 227, for which she has the distinction of becoming the first and only black actress to win the Emmy for outstanding actress in a comedy.

Born in Britain in 1976, to a Jamaican mother and Trinidadian father

Millions saw her performances as Tia/Calypso in two of the wildly popular Pirates of the Caribbean movies, but Harris’s film, television, and theatre roles on both sides of the pond include more literary fare, such as the BBC TV adaptation of Jamaican-British author Andrea Levy’s Small Island (filmed in part in Jamaica) and the mini-series adaptation of Jamaican-British writer Zadie Smith’s White Teeth. She’s also played Winnie Mandela in Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom and Eve Moneypenny in the James Bond films Skyfall (2012) and Spectre (due for release later this year) — both of which are directed by Sam Mendes, himself of Trinidadian descent. Harris is the first black actress to play the role of Moneypenny.

On her Caribbean roots: Asked about her heritage, the graduate of Cambridge university has said: “I was raised within the Jamaican culture in Britain. I was surrounded by these incredibly powerful women growing up — independent, opinionated, strong-willed women, like my mum and my aunt.”

grace Jones: Born in Jamaica, this iconic model, songwriter, model, record producer, and Grammy-nominated singer is best known as an actress for roles in Conan the Destroyer alongside Arnold Schwarzenegger, the 1985 James Bond movie A View to a Kill, and Boomerang with Eddie Murphy.

Born in the uS in 1974, to a Guyanese father and American mother

Luke’s breakout performance was his film debut in Antwone Fisher, in the title role and alongside Denzel Washington. These days, he’s best known for heating up the screen in the new hit uS TV series Empire. Other notable screen appearances include Spike Lee’s Miracle at St Anna, Captain America: The First Avenger, Madea Goes to Jail, Sparkle, Biker Boyz, Friday Night Lights, and playing Sean “Puffy” Combs in Notorious. He’s also been featured in music videos by Alicia Keys (“Teenage Love Affair”) and Monica (“So Gone”).

Also of Guyanese heritage:

sean Patrick thomas: Born in the US to Guyanese parents, he’s known for roles in Conspiracy Theory, Courage Under Fire, Cruel Intentions, Save the Last Dance, Barbershop 2, Halloween: Resurrection, and TV series The District. Read a full interview with Sean on our website.

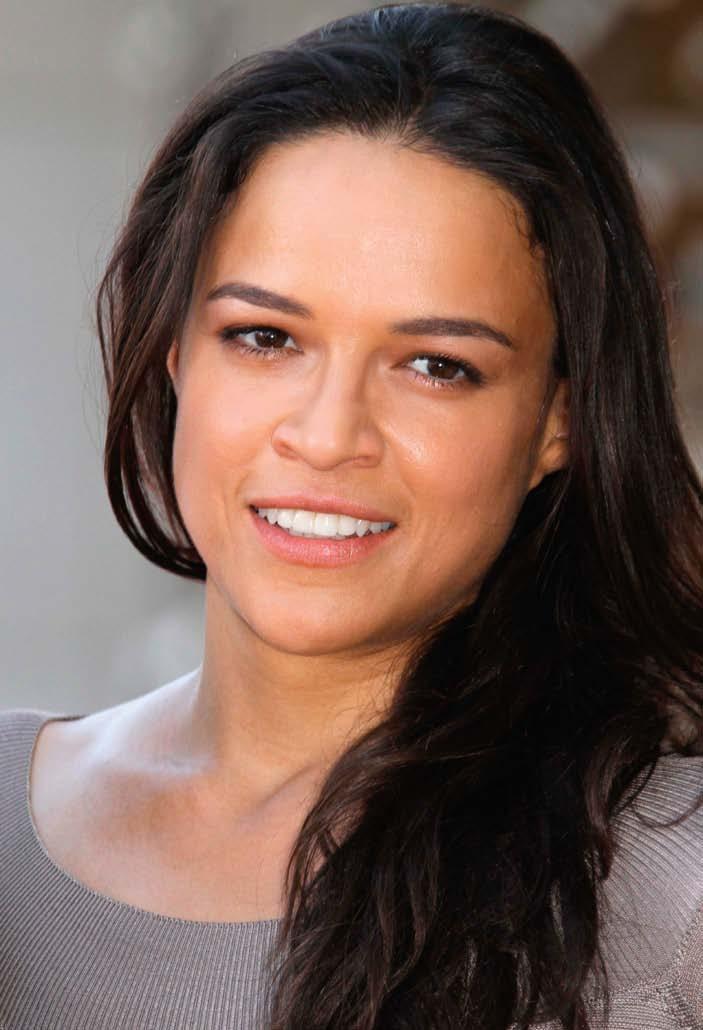

Born in the uS in 1978, as Mayte Michelle Rodriguez, to a Puerto Rican father and a mother from the Dominican Republic, spending some of her early years living in both those Caribbean countries

Her breakout role (as a boxer) in the film Girlfight won her an Independent Spirit Award. She went on to star in S.W.A.T., the surfing movie Blue Crush, the Resident Evil and Fast and Furious film series (including this year’s seventh instalment of the latter), and Avatar, as well as popular TV series Lost. She’s been described as “the most iconic actress in the action genre” in Hollywood, becoming known for “tomboy” roles — and she moonlights as a DJ.

On her Caribbean roots: In 2012, Rodriguez travelled to the DR for the PBS series Finding Your Roots , and was also part of National Geographic’s Genographic Project. Of the impact of her heritage, she says: “The Spanish language has come in handy throughout the years, helping me connect with people all over the world in ways they’d never expect to connect with an English-speaking American. The culture has made me a laid-back warm-hearted seeker of joy in life — I blame that on salsa, Spanish love songs old and new, as well as the warm weather in Puerto Rico . . .

I’ll eventually come back and buy some land in either Puerto Rico or the DR, so I can enjoy some of the nature I love so much in my retirement,” she adds. “The Caribbean has a warm welcoming spirit and a zest for life I can’t compare to any other place I’ve been to. I’ll always have a place for the Caribbean in my life.”

Zoe saldana: Born in the US to a Puerto Rican mother and father from the Dominican Republic, she spent some of her childhood in the DR before returning to New York City as a teen. Known for Drumline, Pirates of the Caribbean, Guardians of the Galaxy, Avatar, and the rebooted Star Trek films (playing Uhura), and the forthcoming Nina Simone biopic, Nina.

Born in the uS to a Jamaican mother, she spent some of her childhood in Jamaica, and is best known for uS TV series Moesha, It’s a Living, and films like Sister Act II, White Man’s Burden, The Distinguished Gentleman, and The Flintstones

Born in the uS to a Trinidadian father and Panamanian mother, she’s best known for uS TV series The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, The Young and the Restless, and films like Kiss the Girls and Home Again, which was filmed in Trinidad in 2012 and co-starred C.C.H. Pounder.

Born in Haiti, migrating to the u S as a child, she’s featured in roles on uS TV series The Jaime Foxx Show and NYPD Blue, and films like Coming to America, Wild Wild West, and White House Down. She also starred in the u S TV movie Girlfriends Getaway, shot on location in Trinidad and Tobago in 2014.

Born in the uS to Trinidadian parents, he’s best known for roles in uS TV series like Weeds, and movies like The Forty Year Old Virgin, the Think Like a Man films, Baby Mama, and Blades of Glory.

Born in the uS to Trinidadian parents (and the grandson of Trinidadian calypso legend Rafael “Roaring Lion” Leon), he won uS TV series Dancing with the Stars last year, but is probably best known for his role in The Fresh Prince of Bel Air with Will Smith (and co-starring with Tatyana Ali, Karyn Parsons, and Joseph Marcell).

Born in the uS to Cuban parents, she’s appeared in uS TV series Suits and the Matrix films. She is married to fellow Matrix co-star Laurence Fishburne.

Born in the uS to parents from St Kitts and Nevis, this decorated veteran actress of stage and screen has starred in films like Sounder (Oscar and Golden Globe nominations for best actress), Hoodlum, Diary of a Mad Black Woman, Idlewild, The Help, and countless uS TV movies and miniseries, including Emmy-nominated performances in Roots , King, The Marva Collins Story, Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All, The Trip to Bountiful, as well as The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (Emmy for outstanding lead actress, and actress of the year). Recently she played Viola Davis’s mother in the hit series How to Get Away With Murder.

And did you know these Caribbean connections?

Beyoncé (Bahamian father)

tyson Beckford (Jamaican mother)

naomi Campbell (Jamaican mother)

stacey Dash (Barbadian father)

Cameron Diaz (Cuban ancestry on father’s side)

Cuba gooding, Jr. (Barbadian grandfather)

ll Cool J (Barbadian grandparents)

tia and tamera Mowry (Bahamian mother)

gwyneth Paltrow (Barbadian great-grandmother)

Jada Pinkett smith (maternal Barbadian/Jamaican ancestry)

Karyn Parsons (Trinidadian mother)

For an extended version of this article — including interviews — visit our website at caribbean-beat.com/ issue-133/caribbean-hollywood

A major change in the Jamaican music scene of recent years is the rise of a bold “Reggae Revival,” reaching back to “conscious,” Rastafari-influenced roots. And the headquarters for the movement is an increasingly trendy weekly gathering of DJs, musicians, and music fans high in the hills above Kingston. David katz visits the Kingston Dub Club and meets its inspired founder, gabre selassie

If you don’t have your own car, getting to the weekly Kingston Dub Club requires a significant commitment, since there is no public transport to its location up in the hills above Jamaica’s capital. An hour-long walk up a very steep hill from Papine Square or a pricey cab fare are the only options, if you can’t catch a ride with a friend. Once you get to the end of Skyline Drive — where it might be cool and foggy, depending on which way the wind is blowing — cellphones switch to torch mode, as you walk along a dirt track, heading over a small rise in the direction of the music.

Steep concrete steps that wind down the hillside soon bringing you to the Dub Club itself, in the yard around founder Gabre Selassie’s home. Turn left to find your place on the heaving dance floor, where massive columns of speakers blast roots reggae at top volume. On the rear

deck, at the other side of the DJ’s sound station, there is a large wooden bar with homemade moringa tonics and ganja wine on offer, along with more standard beverages.

The deck is a real chill-out zone, where you can hear the music clearly, but still carry on a conversation, and in its far corner you may find Rastafari veterans sharing a communal water-pipe. Hot ital food is served, courtesy of Veggie Meals on Wheels, and books on black history are often sold near the entrance.

A mere two years ago, the Kingston Dub Club was an insiders’ affair, an underground destination populated by a few local regulars and the occasional overseas visitor. But these days the place is the talk of the town: a hip spot packed to the rafters, despite its remote location. usain Bolt has been spotted there, and many reggae luminaries form a regular presence — such as dub poet Oku Onuora and singer Kiddus-I, who both worked

with Bob Marley during the 1970s. Most significantly, the space is currently home to the vanguard of the “Reggae Revival,” a coterie of close-knit musicians, filmmakers, and visual artists active in different sectors of the city, who have collectively risen to prominence in tandem with the club, bringing the focus of Jamaican popular music back to its roots.