SPEECHLESS?

A MAGAZINE ABOUT ENDANGERED LANGUAGES AND THE PEOPLE WHO WANT TO PRESERVE THEM

A MAGAZINE ABOUT ENDANGERED LANGUAGES AND THE PEOPLE WHO WANT TO PRESERVE THEM

If I could choose one superpower, it would be to speak every language in the world. I have always been fascinated by languages. They are not just a means of communication, but an expression of our identity and culture, our home. They can be a source of pride or shame, and often contain centuries-old stories of power and oppression, and sometimes of heroism. Of people who have lost everything and yet have never given up.

There are still around 7’000 different languages in the world today. It is predicted that about half of them will be extinct by the end of the century. The reasons are many. They include oppression, globalisation and digital change.

But humans are not only good at breaking things. Countless projects are dedicated to the preservation and revitalization of endangered languages and offer hope. For my bachelor’s thesis, I analysed a number of projects in Europe and their chances of success - this magazine is the associated project. It’s about the people behind the revitalization projects. It’s about those affected by the loss of their language telling their stories.

You want to read this magazine online?

There is a german version too.

Imprint

Bachelorproject by Melissa Stüssi

August 2024

Multimedia Production

University of Applied Sciences of the Grisons

Contact: melissa.stuessi@gmail.com

Available online at www.issuu.com/melissastuessi

by Melissa Stüssi

The evening sun shines over Chur, the capital of the

The Romans once occupied the Alps and oppressed the local people. This is how Rhaeto-Romanic originated - today Switzerland’s fourth national language.

From the other side of the valley, you have a good view of the village of Salouf. You can’t miss the Sonder family’s stable.

Images: Melissa Stüssi

Around 35’000 people still speak Rhaeto-Romanic - including Gian and Simon Sonder from Salouf. The family explains what it means to them to speak an endangered language.

Salouf is a small village in the Surmeir region of Graubünden. Around 200 people call it their home, 80 percent of whom speak RhaetoRomanic. Surmiran, to be precise, one of the five idioms. Salouf was an independent municipality until 2015, when it merged with eight others to form the municipality of Surses.

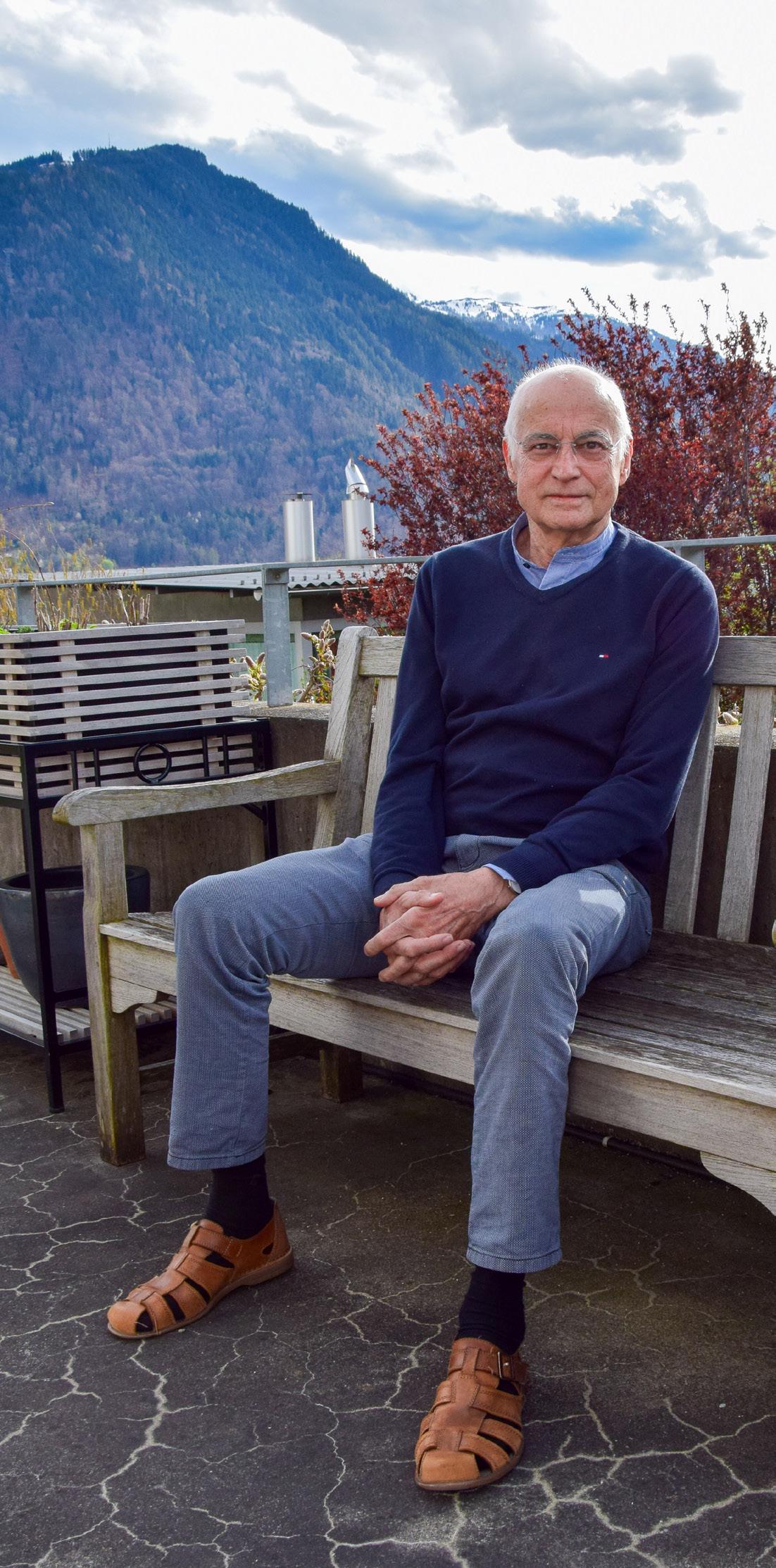

Gian Sonder was mayor at the time. Now 60, he lives in the centre of the village with his wife and three grown-up children. He only spent a short time in Chur when he was born, otherwise he has lived in Salouf all his life, the farmer says jokingly. «Romansh is very important to me. I live

here, it’s my mother tongue. Of course I want it to be preserved.»

Gian Sonder had to learn German as a foreign language at school since fourth grade. «Before that you heard it on TV or from holiday guests», he recalls, «after that I mainly knew written German. The Grisons dialect came when I started working away from home.» At the age of 25, he met his wife Rita, who was working in the tourist office in Savognin. Born in the canton of Aargau, she attended courses to learn Rhaeto-Romanic. On the first day, the teacher told her that the language would be extinct in

50 years. Today, she understands it very well, but speaks only a little: «One day, I was shopping in the village and talking to someone when an elderly man came up to us and said: ‹discurra Rumantsch!›, which means ‹speak Romansh!›that kind of put me off right there.» There’s no point in putting pressure on people, says Gian Sonder: «The language must be used casually in everyday life. If it’s a ‹must› , it won’t work anyway.»

The Sonders have brought up their three children bilingually - they speak German with their mother and mostly Romansh with their father - and things have developed a little strangely between them, explains Simon Sonder, with 27

«It was not until I reached a certain age that I regained the motivation to speak ‹clean› Romansh.»

years the oldest of the three siblings: «I speak Romansh with my sister, but we both always speak German with our younger brother, even though we are all bilingual. This has nothing to do with quarrels, it’s completely normal for everyone. The family has different theories as to how this came about, but it is a good example of how languages can blur naturally in everyday life. In general, language has a different meaning for younger people, says Simon Sonder. Many speak a mixture of Romansh and German. «It was not until I reached a certain age that I regained the motivation to speak ‹clean› Romansh.»

Written Rhaeto-Romanic also plays an important role for the Sonder Family. As president of the «Uniun Rumantscha da Surmeir», Gian Sonder works on a voluntary basis to preserve the Surmiran idiom. The association publishes the weekly newspaper «La Pagina da Surmeir», which has been in existence for almost 80 years. It has a circulation of around 1’200 copies. Gian Sonder and his committee are responsible for printing and distribution. These costs are covered by subscriptions. The «Fundaziun Medias Rumantschas» takes care of the editorial part, which is mainly done by people who don’t speak Rumantsch. According to Gian Sonder, it

Wondering what Rhaeto-Romanic (Surmiran) sounds like?

would be very important to have local authors, but there are not many of them. «The paper is always trying to find a certain consensus between the preservation of Romansh and good, informative articles about the region. It’s not a dictionary», says Gian Sonder.

La Pagina da Surmeir is not only lacking in writers, it is also lacking in young readers. A

point of view, as the editor of this newspaper and as a Romansh patriot, I would like to be able to reach young people better. I want them to have better access to Romansh content.»

Other organisations are also working towards this goal: the «Uniun Rumantscha Grischun Central» in Surmeir and the «Lia Rumantscha» in Chur. The federal government and the canton of Graubünden together invest around seven

«You also have to live the language. Otherwise it remains theory.»

digital version of the paper is being discussed as a solution - but Simon Sonder points out that his generation would probably not read it even then. The fact that they would have to pay for it would be a deterrent for young people who are used to free content online. He only watches the Romansh news, Telesguard, and listens to the radio from time to time. Nevertheless, Gian Sonder is convinced that digitalisation is an opportunity to revitalise his language: «From my

million francs a year in the preservation of Romansh. According to «swissinfo.ch», this is supplemented by around 25 million francs in licence fees that flow into the public Romansh radio and television station (RTR). But the language can only be preserved if it is needed, says Gian Sonder, «if it is used in everyday life. I can see all the ways in which the language can be promoted - but you have to live it. Otherwise it remains theory.»

Rhaeto-Romanic, colloquially known as Romansh, is one of Switzerland’s four national languages. There are five different idioms. The language originated with the Roman province of Rhaetia when the Romans occupied the Alps more than 2’000 years ago. They suppressed the people of the alpine region and imposed the Latin language. The Romansh language was eventually pushed back more and more by Germanisation. Today, the Rhaeto-Romanic area stretches from the Grisons Oberland via the Oberhalbstein to the Engadin and Val Müstair. According to a study by the European Commission, the critical number of speakers required for the survival of a language is 300’000 and Romansh, with around 35’000 speakers, is well below this threshold.

The village of Salouf is characterised by its quarrystone houses. The birthplace of freedom hero Benedikt Fontana stands in a row of houses at the end of the village.

Image: Melissa Stüssi

For more than 40 years, Bernard Cathomas has been an advocate for Rhaeto-Romanic. He has encountered great resistance, but also a lot of support.

Bernard Cathomas’ commitment to the Romansh language began more than 40 years ago. As head of the «Lia Rumantscha», the 78-yearold played a key role in the introduction of the standard written language, Rumantsch Grischun. Rumantsch Grischun is a mixture of the five Romansh idioms - a way of achieving unity in diversity, says Bernard Cathomas.

Bernard Cathomas, which idiom do you speak? I grew up in Breil in the Surselva, Sursilvan is one of my languages.

Has the disappearance of Rhaeto-Romanic had an impact on your everyday life?

Today, Romansh is not disappearing, but has been consolidated in many areas for years. The language lives with the people who speak it. It also lives on in literature, in museums, on recordings and in the means of communication. In my everyday life, I sense a revival, not a disappearance, of Romansh. If one day it disappears - in the distant future! - it would be a gradual process, not a sudden blow.

Nevertheless, you have been an advocate of the preservation of the Romansh language for many years.

Yes, because small languages need special attention. For the big ones, there are thousands of people in universities, media organisations and so on who are committed to the language. Small languages like Romansh on the other hand have to make an effort. As head of the Lia Rumantscha and later at «RTR» (Radiotelevisiun Svizra Rumantscha) and in the management of the «SRG» (Swiss Broadcasting Corporation) in Berne, I was committed to this.

Bernard Cathomas is often referred to as the father of Rumantsch Grischun.

Image: Melissa Stüssi

You came up against a number of obstacles. Romansh speakers feared that Rumantsch Grischun would damage their idioms. Although it was introduced in schools by 40 communes in the autumn of 2009, only a year later 14 of them decided to revert to teaching in their regional languages. Today, Rumantsch Grischun is mainly used in the media and at the administrative level.

New things are always met with resistance - but they also inspire people to take action to shape the future. The protests were also a sign of vitality. Of course it was sometimes unpleasant when I was attacked, but there was also a lot of recognition.

«You cannot preserve a minority against the will of the majority.»

Is there anything you would do differently today?

We are all wiser in hindsight. There are mistakes you have to make once, to avoid making them again. Trial and error, as they say. So yes, with the knowledge I have today, I would do things differently.

What do you think of digital empowerment to revitalise endangered languages?

The digital world is definitely a great opportunity for minorities. It allows them to organise and communicate better. But it should not be overestimated. The digital world is only a tool. What really counts are values, beliefs, commitment, cooperation, risk-taking and trust.

Wondering what Rhaeto-Romanic (Sursilvan) sounds like?

You can’t create that digitally. If people lose interest in their language, digital tools won’t help.

How do you rate the support from the federal government and the canton?

I am impressed by what is being done there. All the documents and reports on «admin.ch» and «gr.ch», the commitment to schools, cultural projects, the media, the modern RTR media centre... All this shows that the confederation and the canton believe in the value of the language. But it is up to the Romansh speakers themselves to come up with sensible proposals.

Since you became involved, what has changed? In the past, people were afraid of being bilingual and often had an inferiority complex because the language was small. Today, people are more confident. I hope that young people will be convinced of the value of preserving linguistic, cultural and natural diversity. And that tolerance and generosity will continue to be practised towards minorities.

What are your wishes for the future of Romansh?

The courage to accept important changes, such as a common written language. And the strength to continue to develop what is new. And to ensure that Romansh remains an «added value» for Switzerland and Graubünden. You cannot preserve a minority against the will of the majority.

Want to know more? Bernard Cathomas has recently published a book: «A path to unity in diversity: a plea for Rumantsch Grischun»

ISBN 978-3-907095-72-0

Reindeer, dog sleds, ice and snow - this is what many people associate with Sami culture. Another important part of it is the language, which is unfortunately spoken less and less.

Norway is making great efforts to promote the Sami language and culture - but Google and Microsoft are putting a spanner in the works.

The Sami have been around for thousands of years. An estimated 80’000 Sami live in Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. They lead a traditional lifestyle of fishing and hunting and are renowned for their reindeer herding. The Sami in Norway have faced many challenges over the years, including government attempts to assimilate them into Norwegian culture and language. In the 20th century, Sami children were forbidden to speak their own language in state schools. The situation was similar in other Scandinavian countries. There are several Sami languages that are not related to Norwegian or other Scandinavian languages. The effects are still felt today - many Norwegian Sami now speak one of the two national languages, Bokmål or Nynorsk.

Sjur N. Moshagen

Against all odds, the Norwegian Sami Parliament was established in 1989 to officially represent the interests of the Sami. Sjur N. Moshagen is one of the scientific employees of the Sami Parliament. He has been developing technology for minority languages for almost 30 years. Although he speaks very little Sami himself, the language is close to his heart: «It’s about basic human rights. People should have the right to learn and use their own language. It has a lot to do with identity and self-esteem.» When an entire community is denied access to their language, it has a huge impact on the well-being of both the individual and the community as a whole. You create huge social problems by denying people access to their own language and culture and the ability to decide for themselves what they want to do with it, says Moshagen.

«Language has a lot to do with identity and self-esteem.»

Sjur N. Moshagen and his team have already developed several tools for Sami, including a comprehensive translation tool, a keyboard for smartphones and a text correction programme. Unfortunately, the language monopoly that the big tech companies such as Google, Microsoft and Apple have created for themselves is a major obstacle. «They decide which languages

to cover and to what extent, and generally don’t allow outside parties to participate in language support», explains Moshagen.

This is a problem because the language technology and databases for the Sami languages exist, but they are not included in, for example, Google Scholar or other applications. Why is this? Google gives priority to languages with which they can make money. Sami and other minority languages are too small for that. «They don’t understand that what they do or don’t do creates barriers to language use», says Moshagen. The fact that the tools provided by the Sami Parliament are being actively used is shown not only by the promising usage data, but

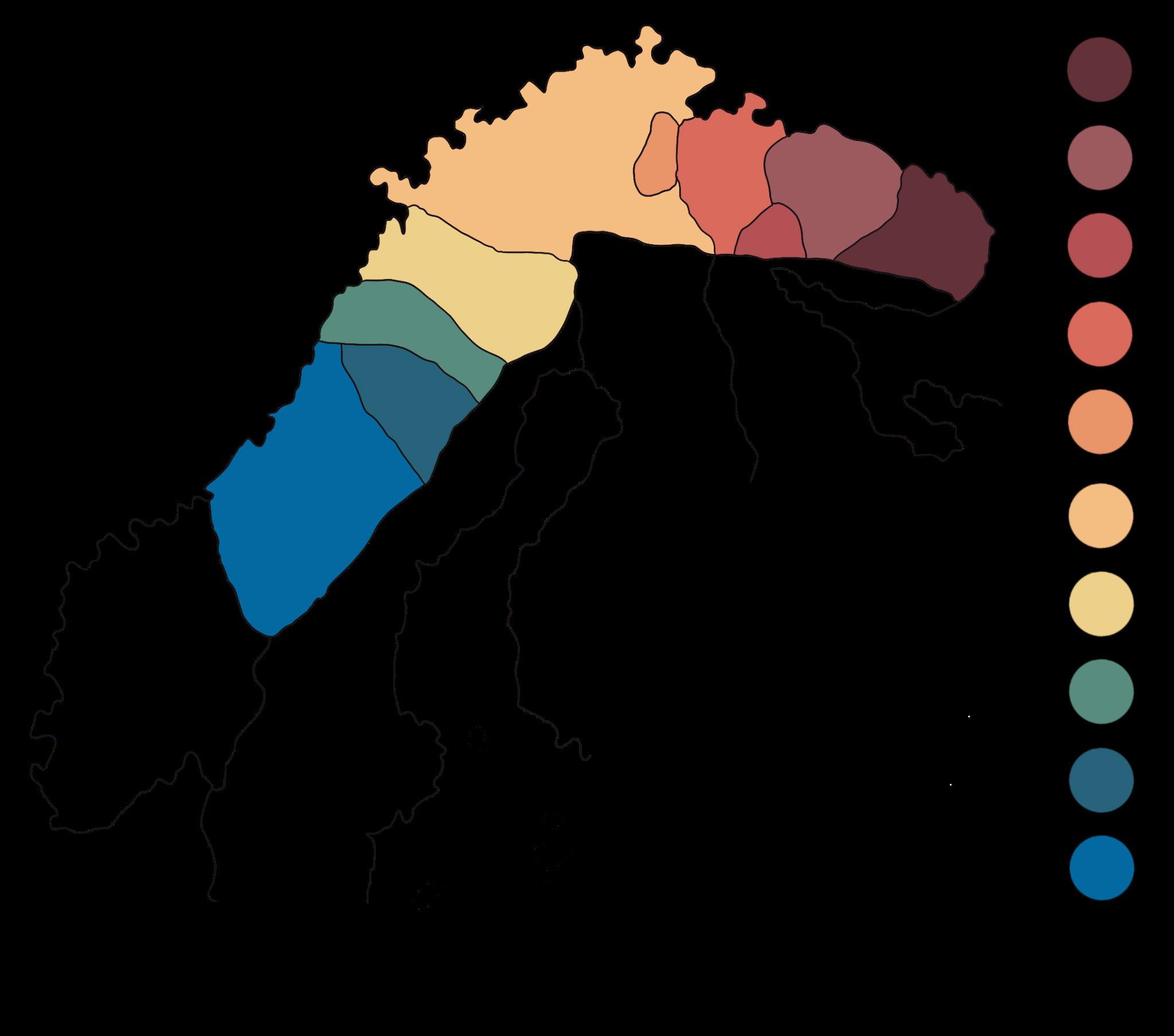

North Sami

Lule Sami

Pite Sami

Ume Sami

The Sami languages, sometimes referred to collectively as Sami or Saami, are the indigenous languages of the Sami people in northern Europe. There are nine Sami languages, with significant differences between them. These languages originated more than 2’000 years ago and developed from Proto-Samic, which in turn developed from Proto-Finno-Ugric. As the Nordic peoples expanded, the Sami languages were gradually pushed into more remote areas. Today the Sami language area covers the northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia’s Kola Peninsula, an area known collectively as Sápmi. According to UNESCO, all Sami languages are considered endangered. The largest, North Sami, has around 25’000 speakers, while some of the smaller languages have fewer than 500 speakers. This is well below the estimated 300’000 speakers needed for the long-term survival of a language, according to a study by the European Commission.

also by the personal discourse: «The mother of a student thanked me personally a year or two ago and explained that these tools are very helpful and essential for her.» A reassessment by the big tech companies could give these tools a much wider reach and thus be a decisive step towards preserving the Sami languages.

To combat this, Norway has been participating in UNESCO’s Decade of Indigenous Languages for the past year and a half. Together with other countries, efforts are being made to find solutions, exchange ideas and benefit from the network. Kristin Solbjør, Deputy Director

General at the Royal Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, is responsible for this cooperation. Unlike Sweden and Finland, Norway invests a lot of money in preserving Sami culture, she says. One of the ministry’s main concerns is to fund the development of technology for minority languages. It also works closely with the Sami Parliament on these issues, because it is important that the Sami themselves can influence policy. The three parties agree that they need language technology - because if the languages are to survive in the future, it must also be possible to use them digitally.

Wondering what Sami sounds like?

The next eight pages are all about the Irish language. How is it that the Irish hardly speak it any more? This story is representative of the fate of so many other languages.

by Melissa Stüssi

On a road trip through Ireland, I went in search of the Irish language and its standing in today’s Irish community. Not such an easy task, as it turned out.

Just over 70’000 people in the Republic of Ireland speak Irish every day outside the education system. That’s around 1.4 percent. But the figure is probably much higher, says language mentor Alexandra Philbin. Taking into account those who speak it every day in the education system, others who could speak it but rarely or never do, and any figures for the North of Ireland that are not included in the census figures for the Republic of Ireland.

Alexandra Philbin works as a mentor for the Endangered Languages Project - an organisation that provides information about endangered languages and supports people involved in

revitalisation projects around the world. On a personal level, she is particularly passionate about the Irish language, having grown up in Dublin but speaking mostly English.

Alexandra Philbin, how do you perceive the fact that Irish is a minoritised language in your everyday life?

Of course, the fact that it is a minoritised language means that in my everyday life when I’m in Ireland, I can’t live my whole life in Irish as I would like to. For example, in certain shops I get served in Irish, but I can’t just go into any shop in Dublin and speak the language. Or if I go to hospital, it’s very likely that I won’t receive care in Irish. Unless a lot of work is put into finding someone for me who speaks the language.

What was your experience learning Irish?

When I was growing up, there was no Irishmedium education in my town. Today there is, which is great, but when I was growing up there was none. So I was taught almost entirely in English in primary and secondary school. I did study Irish at school, though. And I was able to go to summer camps as a child and teenager both in Dublin and in the Gaeltacht, or the region where there is a higher proportion of Irish speakers. I

«Preserving languages is also part of a rightsbased movement.»

later worked at one of the summer camps and studied Irish at university. I have met so many people through the language and now speak it regularly. I teach the language and am involved in its promotion.

Why do you think the preservation of languages in general is important?

I think it is very important because languages are much more than just a means of communication. They also have a deep meaning for the communities in which they are spoken. They have a lot to do with culture, identity and history. For me, preserving them is also part of a rights-based movement. It’s about the injustices that have happened in the past, and continue to happen, to communities that speak endangered languages. And it’s about supporting communities that have faced oppression. I see working towards language equality as working towards a fairer world.

Wondering what Irish (Dublin) sounds like?

It is said that the Giant’s Causeway was once a bridge to Scotland that was destroyed by one giant fleeing from another.

Fascinated by the Irish language and culture, I wanted to find out more. Unfortunately, it wasn’t possible to arrange an interview with a local in advance - so I set out to find someone who could tell me more about the Irish-speaking community.

Our trip started in Dublin. My partner and I rented a car and drove to Belfast in about an hour and a half. That evening, in a bar, over our first (and last) pint of Guinness, I tried my luck

Background

Irish, also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is one of the official languages of Ireland. There are three main dialects: Ulster, Connacht and Munster. The language originated more than 1500 years ago, when Old Irish developed from Proto-Irish. During English rule, Irish was increasingly displaced. Today, Irish is mainly spoken in the western coastal regions, the so-called Gaeltacht areas. Despite its official status as the first official language of Ireland, Irish is used far less than English in everyday life. Irish is a compulsory subject in schools, but the rest of the curriculum is taught in English. According to the 2016 Irish census, around 1.7 million people speak some Irish, but only around 73’000 use it on a daily basis outside of the education system. The Irish government is endeavouring to promote the language, including through language courses and media offerings in Irish. Nevertheless, Irish remains a minority language, categorised as «definitely endangered» by UNESCO.

with a barman. The young man told me that unfortunately he didn’t speak any Irish, just a few words at most. He told me to try further west where I might have better luck. So, a few days later, we checked into a wonderful little bed and breakfast near Bushmills. It didn’t take much convincing to get Martin Brown, our host, to do a quick interview with me. In fact, I found all the people we met in Ireland to be heart-warmingly hospitable and open.

Martin Brown, Maghernahar

«Almost no Irish is spoken in Ireland any more. Over in Bushmills you get a funny look if you speak Irish to someone. I went to Catholic school as a child. We had to learn Irish, but I hardly picked it up. I also had French, but I forgot it too. I wasn’t a good student - although I was the ‹teacher’s pet› (laughs). Most people only speak English. I think it might have something to do with the fact that we don’t have any neighbouring countries.»

Unfortunately, Martin Brown didn’t speak Irish either. So my search continued. And on the same day, we drove our little Toyota onto the ferry from Magilligan to Greencastle. After the trip, I wanted to make a short film summary for my personal archive, so I filmed us getting on the ferry. We came to a halt next to a black estate car and the man at the wheel spoke to me: Did he look good on my video? I was a little embarrassed and thought for a moment that he

didn’t want to be filmed. Nevertheless, I replied directly, asking if I should take another photo of him to make sure he looked good. He laughed and we got talking.

«They beat me up because I was Irish.»

Keith Mccracken, Greencastle

«The Irish language is coming back, but slowly. My mother is an Irish teacher and when I was young Irish was a compulsory subject, and it still is. But at that time it was difficult politically. I studied music in London in the 90s. I met some English people who beat me up because I was Irish. I returned home soon after. Anyway, I personally speak very little Irish - I only know a few words. But I’m very happy that the language is starting to find its way back.»

«You get a funny look if you speak Irish to someone.»

The ferry ride only lasted about 15 minutes, but Keith Mccracken promised to keep in touch via Instagram if I had any further questions. So our journey continued. After the beautiful Downhill Beach we came to more deserted beaches, lonely cliffs, found ourselves on Inishbofin and travelled through our first fjord on a boat in Connemara Nationalpark. After many memories and miles - or kilometers, depending on where in Ireland you are - we arrived in Killarney, famous for Rosscastle and the beautiful National Park. On a carriage ride through the park, Donald the coachman explained a lot about the history, flora and fauna - but unfortunately he didn’t speak Irish either.

Tired from our travels, we decided to go to our next accommodation, a lovely little Bed and Breakfast with an amazing view, where we were greeted by a warm, elderly lady who immediately agreed to answer a few questions for me.

the Killarney National Park.

Image: Melissa Stüssi

«I am not afraid of

Almost at the end of our journey, I found a person who told me not only her story, but the story of a country and a language that had endured many sorrows.

Her original name was Emilia Ní Coileáin. «Ní for the girls and O’ for the boys», she explains. The 64-year-old is sitting in a wicker chair, with a breathtaking view of Killarney National Park out the window behind her. This is where she runs a bed and breakfast with her «other half», as she puts it. Coileáin, also known as Cullane or O’ Cullane, is the Irish name for Collins. The story of why this translation was necessary began centuries ago, when the English came to Ireland.

The Protestant English conquered Ireland in the 16th century and subsequently oppressed the Catholic Irish population. This gradually led to

more conflict and rebellion, but nevertheless Ireland was incorporated into the Kingdom of Great Britain by the Act of Union in 1801. Another important piece of the puzzle followed some 50 years later: the Great Hunger, known in Ireland as the Famine. Numerous museums and memorials throughout the country commemorate this pivotal part of history. «The Famine was England starving Ireland», Collins says, «people were living off the land, off the lakes, off the fish - they were living naturally. But the landlords came in, killed the people, drove them out into the streets and put them to work as tenants on their estates,

in little corners here and there. They just had a sort of vegetable garden for themselves. The problem was that even though they were working the land, they had to pay rent to the owner, otherwise they couldn’t stay.» Children as young as nine or ten were taken from their parents and sent to countries where they were kept as slaves. If the parents did not pay the rent, they were evicted. Their huts were burnt down and they were thrown out into the streets to starve to death. «And in 1847 there was a bad potato crop. A million people died and a million emigrated. We’re talking about a holocaust», says Collins, «and at the same time England

Wondering

what Irish (Killarney) sounds like?

in 1998. «You can play it up all you like and say the IRA was very cruel», says Collins, «the IRA tried to talk. There was no talking. They were persecuted until they rebelled. Did they do cruel things? Yes, they did. But so did England. And as far as I’m concerned, two wrongs don’t make a right.» To this day, there is resentment between the two groups, which has been exacerbated by Brexit and the border issue.

Throughout history, many Irish people have been victims of oppression. Speaking Irish was frowned upon or even forbidden. Needless to say, many were unable to find work. So the

«As fas as I’m concerned, two wrongs don’t make a right.»

was exporting all our grain back home.» One in seven people died during the Famine. To this day, the Irish population has not returned to its former size. The partition of Ireland in 1921 into an independent south and a British north exacerbated tensions. «They had no choice», says Collins, «they could no longer resist. So the Irish split over the treaty. Over the signing away of six counties.»

Thus began the conflict in Northern Ireland, also known as «The Troubles». It was, and in a way still is, a struggle for identity and power between the mainly Protestant Unionists in the north, who wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom, and the mainly Catholic Irish Republican Nationalists, who wanted to unite to form the Republic of Ireland. Violent clashes between the underground IRA (Irish Republican Army) and British security forces continued for decades until a peace agreement was reached

Coileáin family, like many others, changed their name to Collins to improve their chances of finding work and thus survival. But over time the tide has turned, at least for the Irish language. When Emilia Collins was at school, everyone had what she calls «cúpla focal Gaeilge - a few words of Irish». It was important to be able to read and write and ask questions. «Because they saw that the Irish language was dying, they tried to reintroduce it», she explains, «and then Irish became a compulsory subject in school again. It was also reintroduced into some television and radio programmes. This is how Collins learned Irish. But after secondary school, everyone chose French or German instead of Irish because it was more useful to them.

So, are there any native Irish speakers left in Ireland? «You have to go to the Gaeltacht areas, Dingle and Ballyferriter, just beyond Dingle, to find native Irish speakers who still speak

by Melissa Stüssi

‹An Gaeilge› in their homes. There are areas in Galway where it is still spoken and there is also an area in Donegal where people refuse to give up and talk in Irish in their homes.» Today, Irish is on the rise again, says Collins. For many people, the language is part of who they are and they are working hard to ensure that it is not lost. «I am not afraid of change», she says, as the clouds slowly drift over Killarney National Park, «I think this change is natural. And I think that as an Irish nation we have looked around the world a lot for new prospects, new hope, new challenges. So I think it’s only fair that we welcome anyone who comes to us. I just don’t want to lose my own identity.»

Killarney Nationalpark with Ross Castle sitting enthroned in the background. Image: Melissa Stüssi

by Melissa Stüssi

The only constant is change - and that includes our language. Digitalisation and globalisation have had a major impact on the way we express ourselves. This is also noticeable in Swiss dialects.

On the way to the Leglerhütte SAC, you have a wonderful view of the Glarner Alps. Image: Melissa Stüssi

Probably the most beautiful place in the canton of Glarus: the Klöntal.

Images: Melissa Stüssi

Wondering what the Glarus Dialect sounds like?

new dialect dictionary attempts to capture

It must have been in the 1960s when Professor Dr Marianne Duval-Valentin went camping with her two sons at Lake Sihl, as she did every year during the summer holidays. When it wouldn’t stop raining, she asked around to see where she could get good rubber boots for her children. She was sent to Glarus, to the «Goldener Stiefel». There the manager personally sold her two pairs of rubber boots in the finest Glarus Dialect. Madame Duval fell head over heels in love with this beautiful language. So much so that a few years later she wrote her thesis on it: «Le système phonologique du parler de Glaris» was the title of this work.

This is how the Glarus Dialect Dictionary came into being, explains Dodo Brunner, president of the association of the same name, at the book launch. Around 200 people gathered in the Glarus goods shed that evening in May to see the result of more than 4’200 hours of work. The 400-page dictionary is based on Mrs Duval’s dissertation and her extensive collection of index cards. But how do you decide how to spell a dialect word?

«There is no binding, standardised spelling. There are guidelines on how you can or should write in dialect. But these also leave a lot open.

Background

Swiss German is made up of a number of dialects that differ in pronunciation, vocabulary and, in some cases, grammar. The Swiss dialects evolved from Alemannic, which was introduced into present-day Switzerland from the 5th century AD. Unlike endangered minority languages such as Romansh, Swiss dialects, including Glarus Dialect, are not threatened with extinction. Nevertheless, efforts are being made to preserve dialect diversity as mobility and the media increasingly blur regional differences.

«We, the people of Glarus, carry a peculiar linguistic melody as an unwritten certificate of our homeland.»

You can discuss it as much as you like», says Brunner, «with almost every word, you can debate the best way to write it. That was a big challenge.»

«It was very interesting, but also very exhausting,” Brunner sums up. It showed how much the dialect has changed over time. You could spend hours researching a single expression. «In total, we have over 26’000 entries in our database.»

Increasing mobility and progressive networking have changed the Glarus Dialect - just like any other language, says Brunner. Whereas in the past it was mercenaries or traders who imported French or Italian expressions, today it is English and above all High German that influences the dialect.

A dialect dictionary could hardly stop this process, but it would be an important contribution to the preservation of a valuable cultural heritage. It is to be hoped that the dictionary will arouse interest in the dialect and make people aware of the need to maintain it. The Swiss linguist Rudolf Trüb (1922-2010) wrote: «We, the people of Glarus, carry a peculiar linguistic melody as an unwritten certificate of our homeland.»

Dodo Brunner presents the new Glarus dialect dictionary.

You want to read this magazine online? There is a german version too.

by Melissa Stüssi