LOVE, STELLA

Winter 2024 Edition 3- Apricity

‘The warmth of the sun in winter’

By Emelia Koop

Winter 2024 Edition 3- Apricity

‘The warmth of the sun in winter’

By Emelia Koop

Myfinaleditionof ‘Love,Stella’,thestudent&staffbodies’veryownartsmagazine,hasmarkedthe endofaninspiringjourneyformeyetalsoithassymbolisedthegenesisofwhatI’msurewillbea beautifulnewsetofmagazines.Inshort,thismagazineonceagainprovidesabeautifulmirageofthe peoples,passionsandprojectsofmembersoftheMelbourneGirlsGrammars’StellaSociety.

Particuarly,itfocusesheavlyoncreativewritingpieces-whicharealwaysajoytoreadasspring burstsintoseason.As‘Apricity’,wehopethismagazinebringsourreaders-whethertheybestaff, studentorcommunity-asenseofwarmthamidstwhatiscertaintobeadifficulttermasstudents undergofinalexams,begintheirrowingseasonsandaretoldforthemillionthtimetostophemming theirdresses(apersonalstruggleofmine) WarmthisoftenfoundintheartsIbelieve:thebookswe loveholdusfirmly,poetryenchantsusandartcanmakeusfeelseen.Certainly,alongsidetheicy blueofthiszine-thereiswarmth-whetheritbeingrief,orHalloween,orMatildaUnsworth’sart. Perhapsthemostnoticeablewarmthtomethoughisthewarmthcreatedandspreadbythelovely StellaSociety

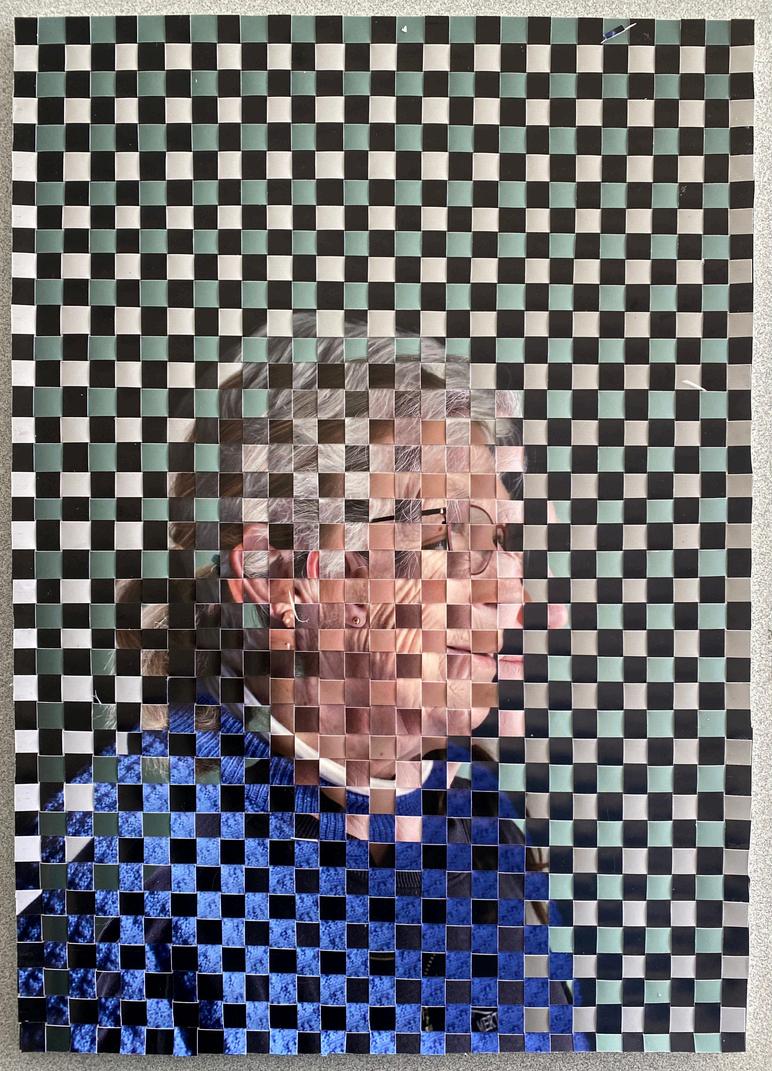

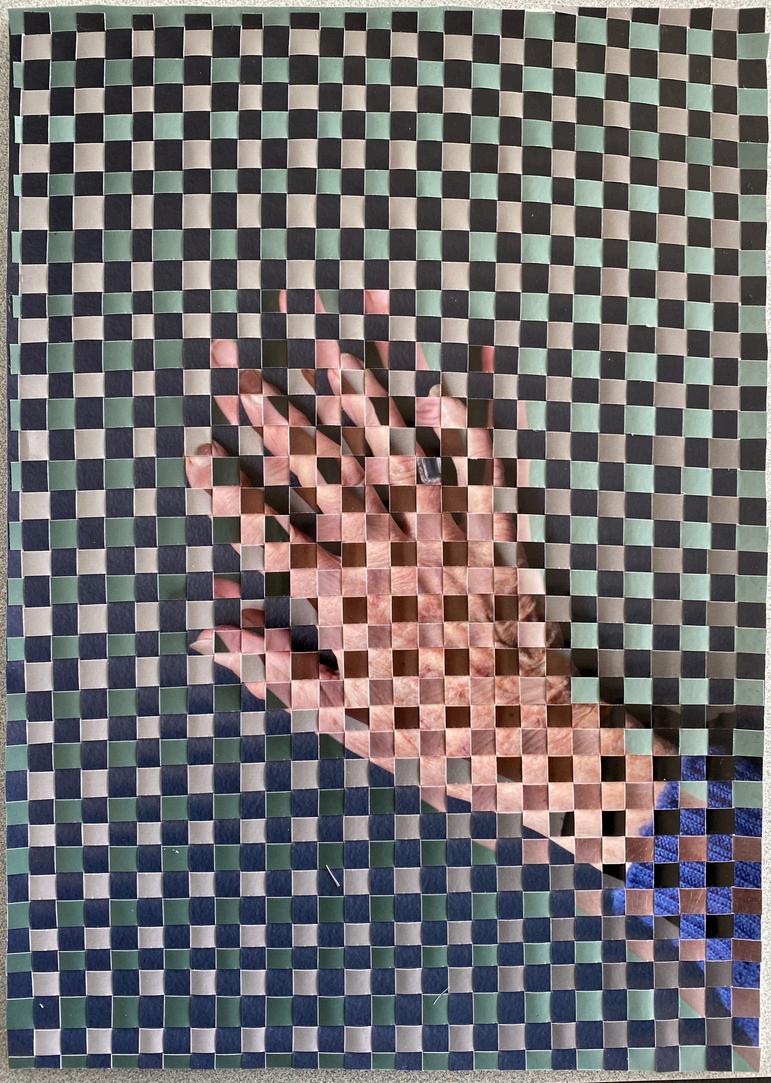

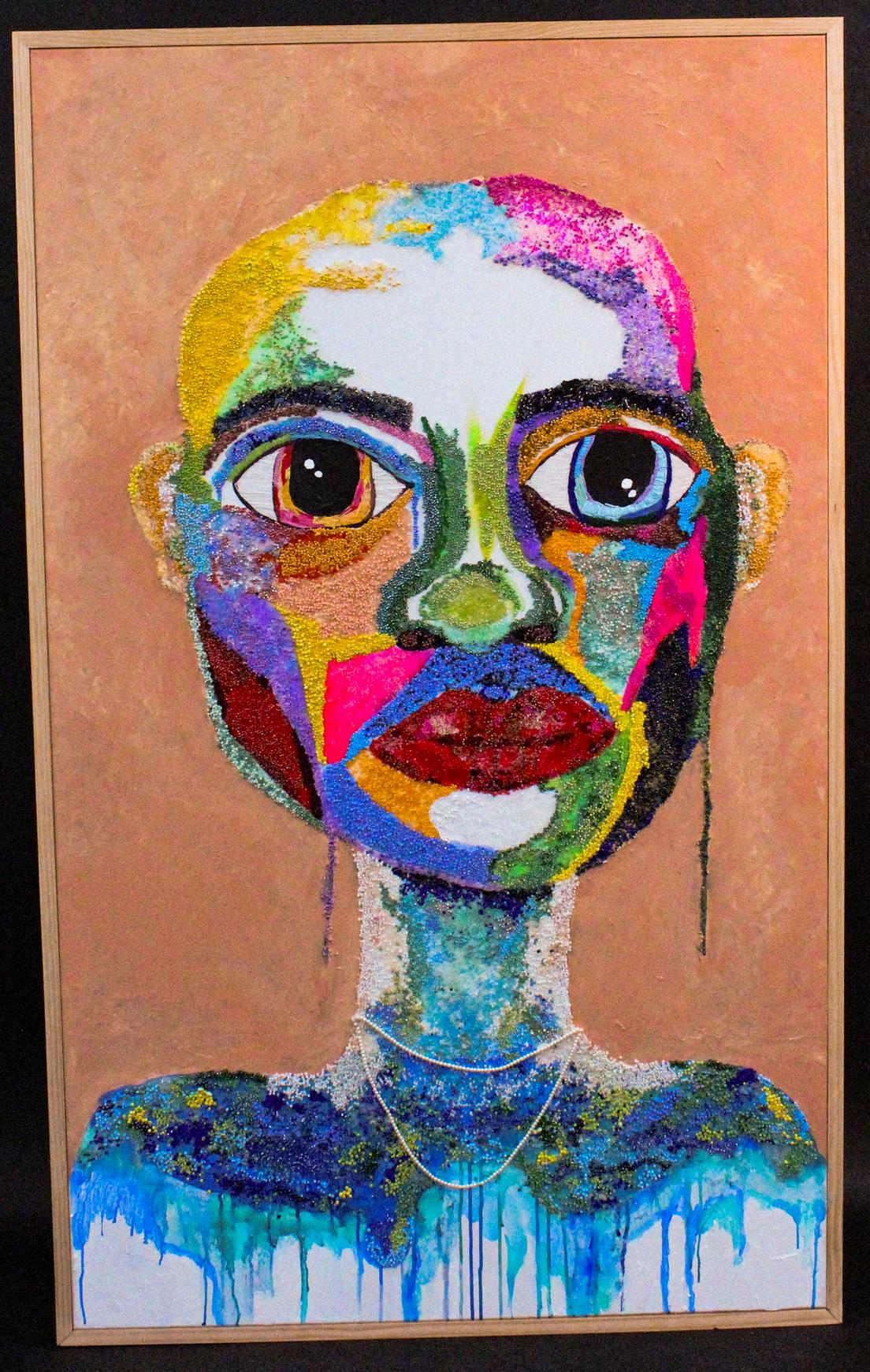

Asagroup,thereisawarmth,apassionandaunity-afriendship-amongstmembers.Thismore evidentthaneverinLove,Stella’s‘Apricity’,ajointstorywrittenbyAliceChoi,XantheO’Loan, ScarlettCulliver,andArabellaPappas,whobegantheirwritingwheretheirfriendsfinished Alongsidethis,wearealsoluckyenoughtohaveacollectionofartfromYear12students-Matilda Unsworth,ChloeEvansandSophMckay.Notonlydosuchpiecesdemonstratetheexpansiverange andtalentofourstudentcreatorsbuttheyalsosymbolisetheclosureofwhathasbeena monumental,emotionalandimportantyearforourgraduatingclassof2024;ofwhich,Iamsadyet alsoproudtosayIamapartof.AsmytimeatMelbourneGirlsandalsoatStelladrawstoanendI hopethatthisbeautifulmagazineissymbolicofallthethingsofwhichartandeducationare-that theyarediverseandexcitingandemboldening

ThankyousomuchformakingthispossiblemybrilliantStellarites!

Love,

YourStellaCaptain Emelia

Theyresisted,seemingtohaveawonderfullywickedvexatiousconsciousnessoftheirownastheywere pulledonharder,thesmoothrubberdeceivingeventhemostobservantofeyes,beckoningtobemeshed againstmyskinonlytoembracetheindispensabletoolsofmotionwithasuffocatingaggression An agressionsocompletelyandutterlyparalleltothemannerismsthatwouldberequired,anactsoheinousby comparisontosuchanaltruisticintention.Asnapcommandedmymind’ssubconscioustosubmittoits antitheticalconsciousformastherubberedgewasreleasedandtheglovescoatedmyhandsafterthefirstof thebattlesthatIwastobedraggedthrough;asaprotectoragainstthesoulinwhichIwastotouchorashield frommyowncontaminatingbacteriumthatmayworkitswaythroughtotheverycoreofthepoorsuffering figurethatwouldbelayinginanagonizingsedatedpain,Ididnotknow,didnotknowhowIwasmoreaware ofthegloriouslyagonizingtaskthatawaitedmeintoday’sfuture,thefuturethatIhadalreadycompletedin theoryoverandoveragain,thefuturethatIhadrespondedtoinwrittenform,inkglidingover microscopicallyroughpaperalongsideamultitudinalarrayofalternatefuturesthatImayneverplayoutbut couldifneedbe Astep,oneisolatedstep,yetsuchanunsteadyuncertainmovement,butasnecessaryasthe nexttogettothestillstancethatwasrequired,requiredtogettothesurestatethatitalwaysledto,the unevenbarely-holding-onbeepechoingmythunderingheart Anotherstep,thebloodroaringand squawkingandscreaminginmyearsmyheadmymind,anotherstep,ahurricaneofwarnings,apulsing surgingalarmdeepwithinwhirringinacrescendoingchaoticsymphonythatresoundedthroughoutevery inchofmypsyche,afinalstep.Assuddenasithadbegun,thesilencefell,allatonceandintocomplete nothingness,acalmingwaveoficecoldtranquillityovercomingmymind,ascalpelhandedover,ablinkto turndowneventhesilence,andIwasnolongerthewide-eyedinexperiencedstudent,butthewomanwith thescalpelthathadonlythegoaltosavealife,andsoitbegan.

By Olivia Jane

By Chloe Evans

I sit cross-legged and upright on the train Sure to keep my feet from touching the ground and my knees from bumping against the woman across from me She sits there, squeezed up against the window, her body rippling like a poked puddle each time the train heaves forward. She is knitting. The insolent, methodical clicking of the needles, occasionally separated by one of her fat fingers getting caught in the yarn, penetrating the silence in tiny, vicious stabs. She smells strongly of talcum powder, as I find all old people do, and I squeeze up my nose- not because I particularly dislike the smell, but rather because, despite not having spoken a word to the woman, I particularly dislike- her I dislike her emerald woollen sweater, which she likely knitted herself, I dislike her nude lipstick, and her face, and the way she sits, her pudgy knees pressed forward and once, I have run out of things to dislike about her, I move on to the woman to her left. Barely a woman at all, she seems, quite the contrast to her seating partner, to be fading away right in front of me. Eyes like round tablespoons that might pop out of their sockets at any given moment, the woman looks as if she is in a constant state of surprise. She is thin, too thin I think, and looks as though, with her semicolon tattoo and dark hair, she smokes at least a pack a day In fact, examining her now, she looks a bit like a cadaver, as if she might explode into a cloud of dust that would inevitably clog up the train, leaving us all stranded amongst the gully birds and eucalypts. She stays quite still. About to move on to the man next to me for examination as the train groans into Avonlea station, which sits at the end of a long, shabby sort of street. The rusted station, a mere shell, lies empty- it’s doors boarded up.

The station is decadent amidst the sweltering heat and standing at the feet of the station the crevices between my nose and lips overflowing- I frown The land here is wider and flatter and redder, and I cannot help but miss the cold commerciality of Melbourne. I miss the slicing noise of trams, the electric rod tugging against the ceiling, I miss the dark swarms of people at 8am, coffees scurrying toward workplaces in silent shuffles like ants weaving across the asphalt, I even miss the smell of diesel and wet concrete. Outside in the warmth, layered in thick black jumpers and coats, I feel exposed- my skin chalked and muted against the violent red earth

I can hear as the ute come wheeling around the road, dust flying as it takes a turn My dad looks like any other local, browned by dust and sun. He jumps out of the front seat, half running half walking to my side of the vehicle, his arms bracketed. He looks gruff and warm. He still hasn’t shaved, yet nonetheless inhabits a sort of physical softness one is only ever born with. I shake my head anyway. He nods, and I build my shield high. Not looking at him, not smiling at him, not speaking to him as he throws my bags in the back The ute smells of beer, leather and sheep, and something in my stomach squirms at the callosity of it

With each jump of the ute, the seats throb along to a silent melody, a clicking of needles. It’s almost silent. But poignant. When we arrive I stand at our cast iron gate, immobilised as I look up at our old white house Nothing’s changed It’s like nothing has changed The vines hang over the veranda, and there are the same two flowerpots by the driveway, my sister’s shoes are at the door and the chickens peck at grass seed that’s been speckled across the weeded lawn. I can feel my dad watching me as I stand there… staring at her house, our house, exactly as we left it. It’s ugly, I think, to myself. The garden is overgrown, and Dad has painted the door a vibrant green colour that I dislike. The cicadas hum is drilling. I drop my bags at the front door, and I leave it behind.

When we arrive at the service everyone is already seated My sisters both wear black dresses and tights. Their hair is mousy and unbrushed. Alice, the older of the two, has grown at least an inch since I saw her last. She has braces now, somehow they suit her. The dark bands bringing out her eyes. My aunt speaks first. She sounds like my mother, and I sit there, small and scowling, looking at my feet as I wait for everyone to eventually drain out of the church. She smells like talcum powder and Special K, my mother, her eyes are big and blue- like round tablespoons- she has mousy hair, a heavy, naff emerald engagement ring my father gave her, and I love her so much it stings. She is so still, my mother. She is so still. Her wrinkles splaying out evenly across her face, a new kind of youth remoulding her. So, in an act of gross sentimentality I take her hand in mine, and I cry, and the tears sting, and the loss stings, and the pain stings. It pierces through me in deep stabbing movements, it’s disabling, harrowing and returns me right back to who I was the last time I stood in this tired church. A girl. An angry girl An angry girl who perhaps wasn’t so much angry as she was lonely A girl who needed her mother Yet, in this moment I am not alone, I finally have her, right there beside me I squeeze her hand and place it back by her side, and as I stand there, quite alone I smile for my mother who was kind and gentle. I smile because she exists in the women on my train who smell and look like her and my aunt’s voice and my sisters hair and my father’s heart. I stand there and for the for the first time since she passed I don’t feel angry anymore. And the cicadas wail, and the gravel crunches and the knitting ticks, and my father cries, and the river murmurs, and the noise holds me firmly, but it’s not enough So, I turn my back on my mother’s casket, and I walk out into the garden There, my sisters sit on the warm pavement and my cousins chase each other around the trees and bushes and my uncle flips sausages on our old barbeque. The garden is lit up with fairy lights, and my cousins scream with delight as they chase and tag. I close my eyes; the air is warm and gentle, and it smells like sausages. I don’t long for the slashing of trams, or wet concrete or coffee. I miss my home, and I miss my mum but most of all I miss my dad; who is big and who is soft So I stand by his side in the garden, and I let him hold me in his arms as I cry for my mother and all the beautiful things that I’ve scowled at And the world turns emerald, and it stings, and clicks, and smells of talcum powder. By Emelia Koop

Every October the school moms gather for the Halloween party, a precursor to the Parade the day after. This year, the party was to be hosted at the Singer family home – heaven knows why, because the Singers don’t even live in our district. Sarah Singer had been my kindergarten teacher three years ago. A woman with a long, oval-shaped face, Sarah wore thickly rimmed black glasses which enlarged her eyes like a giant microscope; her auburn perm a fuzzy lion’s mane which seemed to double in size on humid days. Sarah was obsessed with the arts and ‘free expression.’ One night in late September of kindergarten, after our parent-teacher conference, my mother remarked to my father that she was a “strange bohemian cat”. That night I looked up the word ‘bohemian’ on the blocky family computer. The computer said it meant ‘ a socially unconventional person, especially one who is involved in the arts.’ I catalogued this word neatly into a growing personal vocabulary, which dad said made me sound like my mother in miniature.

Mom dressed me for the Halloween party in a skirt of soft pleats and a crisp navy J Crew polo. It had a little white crest sewn on the left-hand corner, the same brilliant white as my socks, like a good Madeline Schoolgirl. On the car ride to the Singer’s house, my mother made impatient tapping motions with lacquered nails on the steering wheel. I found this quite annoying. I asked her why the Singers’ home was in Yonkers, not Scarsdale like the rest of the kids from school. “Benny’s mommy is a teacher, and teachers don’t live in houses like us ” , she explained. I nodded in silent assent.

We exited the New York State Thruway onto Palmer Road, rumbling slowly to 4 Kenilworth Street, an anticlimax of dusty cherry brick. The two discoloured lion statues flanking the protruding, walk-up brick staircase were a weak attempt at grandeur, at which the red bricks seemed to laugh. As I looked closer, I could see that the staircase was slightly lopsided, and tiles were missing from the sloping grey roof. Standing in front of the brown, plastic screened door was Sarah; auburn spongy fuzz dancing wildly above her head, hands waving vigorously at our arrival. Her cotton pink dress was visibly pilling, accompanied by little scruffy heels, their colour scratched off at the sides from wear. She wore crimson wool stockings. Complete with a rose lipstick, which showed itself on her teeth, Sarah resembled an unsightly flamingo.

Moms from our neighbourhood – which, as I said before, was a decent drive from this one -ascended the brick stairwell in orderly procession, holding elbows with affection as they complimented one another’s dress in caressing voices with which I was well-acquainted. Small white sandwiches with smelly egg were consumed with ‘champagne’, its hideous sweetness made at once evident by screwed up faces. Mothers were quick to replace such faces with saccharine smiles in Sarah’s general direction. As I walked down the carpeted hallway, I noticed a slight damp smell, which made my nose feel very itchy. I suddenly felt quite uncomfortable and wished I had agreed to go with Hannah Rosenburg to the City instead – Hannah's mom had a little shop on the Upper West Side that sold macarons, and Hannah would help line the small coloured biscuits in good, orderly rows. Images of small, plump macarons rose brilliantly before my mind before Mom flashed me a look that said “ go play with the other children”, so I walked unwillingly to the little slab of concrete - the ‘backyard’, if you could call it thatwhere the Singer children and others were congregated. I was easily the oldest one there, except for Benny Singer, who was actually in fourth grade too but in a different class. Benny was a portly child with a wan face, an ochre outcrop of greasy hair and sweat marks showing through his JC Penny flannel. He wore coral jelly shoes, discoloured and chewed on the left side of the heel, as if by some mysterious dog. I refused to join their big game of Blind Man’s Bluff – I wasn’t being impolite or anything, but games like that are for little kids, not fourth graders

The next day was the Halloween Parade, and mom, my little brother Jacob and I walked to school with the Rosenburgs. The Rosenburgs live in a lovely house of cream brick, just off Chalford Road, on Dorset Lane, not far from the Hebrew Sunday School that Hannah Rosenburg attended. According to the moms, Sarah had been touting little Benny’s costume all throughout the Party yesterday. “It’s really something”, Sarah had smiled broadly, a wildness flickering in her eyes, head tilted slightly back, revealing lipstick-stained crowns.

As their little heels clicked along the asphalt, mom remarked to Elizabeth Rosenburg “Such a queer cat she is”. They walked ahead of Hannah and I, talking with bowed heads about Sarah as if sharing important secrets in the playground. They also talked about Sarah’s husband, Steven Singer, who was equally strange, if not stranger, than his beatnik of a female partner. He was an entrepreneur of a small business ‘Yummy Mummy’ which sold breastfeeding gear to new moms. Most of the moms who had met him said he had a malodourous presence which they claimed had a hint of sour milk.

Later that day at Seely Place Elementary School, the moms gathered in swelling bunches on the dirtpatched front lawn, as we busied ourselves with our costumes in whispered anticipation. Children wore classic costumes with little variety between them, boys as superheroes – there were five Captain Americas in the cohort of thirty-five - and girls as pearlescent princesses. Hannah was Tinkerbell, her dress an iridescent pistachio macaron that caught the light wonderfully, the fabric flowing easily with her movement. My mother’s dressmaker had made me a buttercream Belle costume which reminded me of the little daffodils which lined our lawn in neat rows in the springtime.

Assembled in an orderly procession, the fourth graders began the slow snaking toward the school’s asphalt driveway, where a herd of overzealous moms and dads waited with bated breath. Small grey phones were fixed in position to capture the glory of ceremony. But as the snake of fourth graders emerged from the left-hand side of the school’s rose-bricked flanks, a gasp issued from the crowd at Benny Singer, the group leader. Benny was unrecognisable, as Jigsaw from the Horror Movie Saw. Sarah had clearly spent weeks on his home-made mask, which fit his pudgy, pathetic face perfectly. Swirls of blood red adorned the ashen, protruding cheeks of the mask. His little pupils were hardly visible from his mask-eyes, a shocking vermillion in the black pools of his sclera. His nose was bulbous, like a swollen, grey carrot. Worst of all were his grotesque tufts of black hair that shone obscenely in that waning October sun. Whispers started to cord through the crowd, as parents beheld such an absurd, unthinkable costume for a children’s parade. My mom bristled uncomfortably, and I turned to Hannah. “It’s so ugly I want to puke.” The unspoken agreement of costume civility had been broken by Sarah, the singular face which beamed from the audience at her little Benny.

It was customary to give out an honorary ‘Best Dressed Award’ at the Parade, usually to the most handsome little Prince who the parents gushed over and who made the little Princesses blush. This year, Principal Bolton had invited the local Scarsdale costume designer – who made costumes for the local Jewish theatre group which Hannah had quit in third grade – to announce the Award. The Award provided the lucky child with bragging rights in the playground, thus formally securing one ’ s social position. Johnny Brinberg, who won last year as Spider Man, had been the head of the boys’ Popular Group ever since, a venerated playground Jester. The costume designer – Miss Carrie Cohen –sauntered up to the makeshift podium, a round woman with lots of little sunspots on her skin. Any restlessness from the group of children momentarily stilled, as Miss Carrie held the crowd with her high and breathy voice. “And the winner is...” she inhaled sharply into the microphone, “Benny Singer from Fourth Grade!” A deep shock arrested the crowd, punctuated only by Sarah, who beheld her little tubby terror with sickening pride.

The car ride home was so quiet that I could hear acorns dropping on the car roof, hitting it like an incessant game of miniature darts. Mom tapped her lacquered nails on the steering wheel with an anxious rapidity. She sighed, then opened her mouth slightly, hesitated, then closed it. A few minutes passed. “Mom?”, my brother Jacob asked.

“Yes, what is it honey?”

He paused in thoughtful deliberation. “Why don’t people like Benny and his mama Sarah? Is it only because they live in Yonkers?”

“Of course not sweetie,” she trilled. “It’s just that their family – well, a lot of the families who live in those kind of suburbs – are a bit different, that’s all.”

“Oh.” Jacob looked down with a quiet acquiescence at his twiddling thumbs, before turning to face the window, where apricot-coloured trees dropped their leaves.

I reproach back into my dining room with Alex’s third beer in my hand. “Legend”, he says, and hones his eyes back in on his lovestruck girlfriend. I hate that I have to witness her sister’s love crisis in my own home and make small talk with her rebound boyfriend. Why is this Brooke’s method of choice for getting over Harry? I dread the season of chaos that is to come. I will have to pretend to root for this man, because god forbid I’m not happy for my sister being in love again. And then when he fucks up I’ll have hours of conversations with Brooke about how we both hate him, and that we were so blind sighted, and could not have possible guessed he wasn’t as great as we thought. It’s inevitable.

“Alex, how do you like Melbourne?” Jess asks. “Oh it’s great! But I don’t stay in one place for long.” He turns back to Brooke, pointing at her flirtatiously. “You should leave that big corporate job of yours and come travel with me in my van. ” They start discussing the idea, as if I wasn’t there hosting them for a nice dinner I search Brooke’s face for a hint that she’s not actually serious about leaving her job. That job was everything to Brooke when she was with Harry. His ambition was good for her.

Man, I miss Harry. The night Brooke first introduced me to Harry, five years ago, I loved him immediately He took a genuine interest in me and my plans for the future and cherished me like a sister. I envisioned him as part of their family. I told Brooke he was the one, and she’d better do everything she can to make sure he never breaks up with her. She promised that she would. Five years later, Brooke broke up with him. Out of ‘boredom’.

I’m tuned out of the conversation, but something Alex says catches my attention. “You deserve some freedom, babe. You’re not with him anymore. Stop living like you are. ” I’m livid. How selfish, Brooke is impressionable and he’s using that to his advantage. I know exactly what Brooke must be thinking, that all he wants is for her to be happy. More like all he wants is some company on his little road trip. I bet Brooke will end up paying for this trip too. I can only hope that’s not part of Alex’s plan.

Knowing what I’m about to say is inappropriate for a meeting-the-boyfriend dinner, I decide I’ll do anything I can to steer Brooke back to her senses. Nostalgia rushes through me as I bring it up. “Brooke, remember the time we went camping with Harry? He planned it all months in advance.” I was sixteen at the time, and Harry was so kind to invite me even though it was his one week away all year with his girlfriend

“Ha! I bet that was fun.” Alex jokes sarcastically “A romantic getaway babysitting your sixteen year old sister.” Brooke laughs. She never found Harry funny. A fire brews within me at the joke made at my expense. But I take the chance to commend Harry further

“Brooke had a great time actually. Plus, she got the whole back row of the car to herself on the way to and from the campsite because Harry was teaching me to drive. That was the best trip ever, right Brooke?”

Brooke stares at the floor like she’s trying to decide whether to say something. “Well I’m glad you had fun with Harry on that trip Because he ignored me the whole time ” The silence in the room is deafening. I have to look away as Alex puts on a convincing act of sympathy and concern. Does he not know Brook at all? Brooke isn’t even sad about Harry. She doesn’t need comforting. Although I doubt his concern is genuine anyway.

Had Harry ignored Brooke the whole time? I try to imagine it from Brooke’s perspective. Brooke was never easily satisfied with the small things in life like Harry and I were, but she had been complaining that the two didn’t know each other inside and out the way couples should. That’s why Harry planned the trip.

I now feel a bit guilty that I came along Looking back, Harry had probably invited me out of politeness. It wasn’t fair to Brooke.

“Did you break up because of me?” I ask. Brooke looks mad now.

“No. I hate to break it to you but believe it or not, Harry isn’t perfect. He was uncompromising.” She gets up and leaves for the bathroom, leaving me alone to entertain Alex with no guidance

After a good minute of silence, Alex attempts to make a joke. “Don’t worry, I won’t invite you on the trip Brooke will even get to sit in the front seat ” He looks unsure of himself, like the joke was desperate attempt to fill the awkward silence. I don’t know whether to clap back or laugh and save him the embarrassment.

“It sounds like he really cared about her ” Alex says “He did.” I say, instinctively. Forever defending Harry. Although a tiny bit of doubt has started creeping into my mind

“I know I’m not what you ’ re used to but I’ll be the best that I can. ”

Some of my hostility towards Alex softens, even though what he said was the bare minimum. With the idea of that Brooke will never be as happy as she was with Harry, being tainted by what Brooke had just said, I guess I don’t have to hold Alex to such a specific standard

Brooke comes back into the room looking like she’s preparing herself for any level of chaos or awkwardness I might have caused, but I take her by surprise with a joke “Don’t worry about us getting along, Brooke. I get more invested in your relationships than you do.”

I am instantly embarrassed by my obnoxious joke, but Alex laughs and makes light of the situation. Despite the insensitivity of it all, Brooke seems relieved. It’s been a while since she and I have bonded over a light-hearted joke. I notice Alex’s beer is empty and this time, ungrudgingly offer him another one

By Nina Chang

His back is a beautiful contortion, exhaling and shivering with breath. Tiny hairs sprinkling the olive skin like magnificent freckles of the night. In. Out. Shiver. Gone.

My side of the bed is cold. I let it eat me alive. The cold, racing up the palms of my feet into my ears- whispering secrets.

I’m too cold, too lazy, to move.

So, I lie there, outstretched, letting cold kiss my body- sucking and biting, stripping me of myself. Just as he did. But it’s so cold and his so warm that it aches. The heat of his body throbbing off him in waves that engulf and swallow and drown.

The water is dark. And I open my eyes, letting them fill with salt water. It doesn’t sting. Or pinch. It’s agonisingly gentle- the water. And for a terrifying second, my body won’t move, it just floats beneath the surface- my mind awake but my body cold and still. And I let it tug me, and hold me, as it carries me to the shore. My breath still and foggy. And if only for a second I can see him, paddling out into the break, his back contorting, arms peeling through the waves. In that moment, the sand doesn’t crunch, and my heart doesn’t beat, and no one sips their coffee -the wind stops her wailing. The whole beach is silent, the world is. The world is silent as we lie there together, in the ocean, in my bed, on his couch and as I turn to smile at him, one ear out of the water, the noise returns, and I’m alone- submerged in a terrifying cold.

By Emelia Koop

A layer of mist across the Alaskan tundra held the world in silence, disturbed only by irregular quivering’s of the wind. Through the trees, the horizon faintly glowed, and I smiled knowing it would be a sunny new year ’ s morning. Hours before the earth had imperceptibly woken and stretched her limbs in unconquerable strength, I had chopped the wood, fed the hens, and rehammered a fencepost. I left an offering in my late father’s shrine and wished him a happy birthday, then set off on a stroll while my grandparents still slept inside. Down my well-trodden path, en route to the raven ’ s hill where I could watch the sunrise, I came by the frozen lake and noticed an ice sculpture which I had either never noticed or had never been there before.

It was shaped like a small girl, yet she did not look young She was kneeling by a tall stone covered in bundles of fresh forget-me-nots, not a day old. Writing on the stone read, ‘Semper Desiderari.’ I didn’t quite know what that meant. As I got closer, I distinguished the position of her hands, clasped together in angelic prayer, and her head tilted slightly up to the horizon line across the lake. And as I shuffled through the sleet to stand beside her, I saw droplets of frozen water dripped across her cheeks, and solid tears welled up in her eyes. Her emotions set frozen in time. I studied her face, and met her eyes, when she blinked And this was when she spoke to me.

“Hear me human,” she said, her tears reanimating. “Here lies he who I was supposed to protect.”

She cast her eyes to the bushes a little to the left, and mine followed. Two wings lay in the winter shrubbery, fractured, broken, and unnaturally torn. I snapped my attention back to the girl and noticed the two jagged stubs on her back, where wings once grew proud. I drew a sharp breath in, and my eyes widened in epiphany

The girl then took my hands and clutched them in her subzero fingertips, and said, “I am a very bad guardian angel. I failed my human, let him die, and received my judgement. Today was his birthday, I want to find the family he left behind and give them my blessing ”

I bit back a cry of pain as she gripped my hands tighter and tighter. “Okay, okay... I can help you find him. But I'll tell ya, there’s a fair few people living about the village. It won’t be easy, ” I replied.

‘I have not got long human. When you feel the apricity in the bleak mid-winter, I shall be all melted Please, help me before then ’

“That'll come in two hours, but I’ll see what I can do. She looked on to me, expectingly. I sighed, then said with a smile, “Your hands may be cold, but y’know, your heart is like the comfort of a cat curled in your lap as the storm grumbles outside ”

At that, her distant eyes seemed to soften as if the biting air’s chills stopped for just a second to let in the warmth of the sun A faint twinge of amusement on her plump cheek was overridden by a steady breath.

“Let’s go ” .

And so we did, yet, without her wings, the angel looked like an amputee lacking a wheelchair- stumbling to the ground with a damp crunch of the permafrost, smacking her snow-white palms into the dirt and landing on a forget-me-not, tarnishing her enclosure of skin with a pointed howl Her stubbed wings quivered with the sharp inhale of what, at that moment, was merely the body of a powerless young girl.

The slopping back linking two straggling legs conjured a phantom memory in lucid colour, it reminded me of that movie I used to watch with my grandmother through all those long nights in the hospital. It's not the constant smell of sanitizer, or the sound of wailing widows that I think of when I see that place- - I think of the nothing. The absolute absence of anything. Any kind of stimulation or distractions. Any place to look that isn’t his weeping bandages, or watching his chest fall to pray it will rise again just one more time I used to pray a lot then Those were the nights my Grandma would sit me on her lap, balancing an iPad against a vase of wilting flowers, and we would watch The Little Mermaid.

And now, as my mermaid grips her never-before-used toes into the hard dirt to push herself up and gain momentum, the momentum that would eventually cause pain when she hits the ground again, I’m as still as the frozen lake. The prince should go and pick up the dainty shoulders of the stumbling girl; he should support each modest step into the sweltering horizon. Yet, a slight ping of inhuman satisfaction ticks behind my left eye as her jaw hits a small stone on her descent Voltaic vindication twinges deep from my spine running to fill my veins and collect at my pulsing fingertips- a servant of God himself- the father of all- plunges down to the cold earth, and feels, just for a second, what he felt. Pain.

“That man you said died”, I said to her, cocking my head left to get a closer view of the ‘angel’ “Why why didn’t you save him?”

Stopping her fruitless clamoring, she looks up to me, allowing the bouncing curls that loop around her shoulders to flutter weightlessly to the side. Her angelic clear blue eyes lulled as a deep sob escaped her pink lips.

“I got distracted…I…I… ” her own tongue became too heavy with the weight of memory, stopping, she looked to the bedraggled forget-me-not mutilated under her palm. “Wherever I go, I just cause destruction. That’s why I’m incarcerated to the shackles of legs…maybe if I help the boy, God will give me my wings back.”

“Oh, little angel” the words falling from my mouth like butter on a hot spoon, “ we are a long way from heaven”.

The quickest route from the lake to the village was down through the forest, back to the sun, across the river, then through more forest. It was the quickest yet the least taken for a reason: the river was too wide and deep to safely freeze over in the winter The ice there forms deceptively thin, thin enough for all the mothers to scare their children into avoiding the river in wintertime with a tale learnt from their mothers who in turn learnt from their own. It’s in the summer, when the silence of the snow is broken by the cries of the plovers coming in for the river running thick with trout and blackfish, that the village comes together again The nets become heavy with fish; bird for dinner is almost always a given; there’s warmth beyond the crackling hearths of our homes, found high up in the sky.

There’s a heaven to be found there. In the middle of winter, the first day of the new year, there’s no solace to be found in a place without the sun. The early morning sky resembled that of shadowed snow, tainted darkly; in turn, our path lay against to where the sun should rise. Explaining that to her, I tread on through: the angel followed behind. Finding our feet in the snow. Avoiding the thin branches of birch hidden in the dark. It was for some time that we walked like that: her, in quiet focus; I, in rumination.

What words were meant to be said to a servant of a higher being? She’d little to say as we walked on through to where the river should stand, managing quiet answers to any avenues of conversation useful to her task A task that should be completed before the sun should rise; by the time we got to the river, we had an hour and a half left.

We tramped over snowy mounds, these cloudlike shapes blocking our path to the village, but with each step closer to our goal, I felt myself becoming more and more hesitant Did I truly want to see the townspeople, who would heap their insincere words of sympathy for my father's passing? Truly, my initial idea of helping the fallen angel with her quest seemed irrelevant now that I was in the face of such events. I found myself walking slower as we reached the frozen river, my footfalls as heavy as my heart. The snow seemed to be falling more quickly now, and the shadows that had once been so shy to emerge were now enveloping us in ominous darkness The angel shivered, chills racking her body as we stopped to gaze out to the crystal blue river. It was not as frozen as I had hoped, with more cracks and liquid patches appearing every minute.

The fallen servant twisted around to face me; her eyes flicking over my frost-bitten nose and lips

“Are you sure it is safe?” she asked. “No, but I believe we must only hope that your divine being will grant us safe passage over the river.”

“That is a risky gamble, my friend,” was all she had to say. Willing myself to tread lightly over the thin ice, I continued onwards into the open The little angel followed behind me, slipping and sliding all the way. “Be careful!” I found myself ordering her “The ice is only thin; one small misstep may be the end of you. ”

We pushed on, placing our feet on the darker spots, cursing when we trod in the wrong spot. For the moment, we were making good progress, and I allowed myself to relax a little when we arrived closer to the bank.

But this was to be my fatal error

This relaxation of the body, for only a single moment in time, was all it took for the ice to refuse me. It began to crack at my feet, fractured pieces floating off into the open water, rapidly drifting away from me.

The snow seemed too white, the ice too sharp, my breathing too loud, the apricity of winter chaining my heart, soul and being to this moment My life, too, was slipping away.

Pieces of my jagged heart cracking, the last bit of the glue holding me together, Melting......................................................................................................................................

.....until it was gone.

It was a pity that the fallen angel didn’t get to see my face as I fell through the ice. Perhaps it would have increased her guilt about the death of the one she was meant to protect with her every will.

My father.

FIN

Sheisalmostrunning.Sheholdsthecrownofherhat,consciousthatsheiscrushingthelinenflowers thatlessthananhouragoshecarefullywoveintoitsribbonedbrim.Herskirtsnapsaroundhershins, obstructs,atthelengthofherstride,thespeedofherflight.Herhairiscomingloose.Shewantsto pauseandreturneverything thehat,thehair,thebatteredroses toorder,butthereisn’tenough time.Shemustkeepmoving.

‘Comeon.Quicklynow!’Shetugs,andthesmallboybesideherlurches.Herunsflat-footed.His shoulderstiltlikeunbalancedscales.Sheknows,withoutlooking,thathisnewbootswillbescuffedat thetoesandhewillbeweepyandeasilyroused.Somewhere,beneaththeflurry,sheisdisappointed.

Shehadwantedeverythingtobeassheimagined.Smiles.Boots.Acheeryhow do you do.

Absurdly,impossibly,shehadwantedhimtobeperfect Shesighsandlookstothesky Itstonesvaryfromadrearygreytoanapocalypticdarkness Soon,she thinks,therewillberain.Whatasurprisethatwillbeafteryearsinthedesert.Shetriestoimagineit, theendlesssandandburningsky,thehorsesandthemenastrangecalligraphyagainsttheblankness ofthatgeography.Aworldawayfromthiscitystreetanditspeople mainlywomennow going abouttheirbusiness,tunedtothesubtleshiftinatmospherethatsignalsrainisimminent.

Shetugsagainandsheandtheboysqueezebetweenanironpoleandawomanpushinga perambulator Despitethecold,sweatmustersbeneathherbreastsandslicksthebackofherneck A fruitererdressedinadirtycanvasapronandclaspingahandfuloforanges,stepsoutofherway As shepasseshim,thesmelloforangesbloomsandfades.Somethingcatches,justoutofreachof memory,butshepushesitaside.Thereisn’tenoughtimeandbesides,sheisalmostthere.Thereis onlythisstreet,theroadandthenthestation,whichsurelyatthishourwillnotbesofull.

Sheturnsacorner,breathes.Ayoungmaninabatteredhatwithacigaretteclaspedbetweenhisteeth smilesather Shereturnshissmileasonegrantssmall,tediouswishestochildren It’sbarelyasmile atall Shelooksdownattheboy Hisblondeheadisturnedtotheyoungmanandthesmokethat plumesfromhisbottomlip.Shesqueezestheboy’ssmall,moisthand.

‘Teddy!’

Theboycoughs,trips.Shestops,irritated.Theyoungmanturnsaway.

‘Comeon.You’realright.’ Butshe’stoolate.Theboy’sarmsarearoundherthighsandhisface,halfsubmergedinthenavywool ofherwintersuit,iscollapsing Shepusheshisforeheadwiththeheelofherhand,consciousofhis tearsandofhisnose,whichhasstartedtorun Heopenshismouthandemitsawailofdespairthat drawsinitswakeatrainofdisapprovingglances. Theskinofherneckflushes.Itisallfallingapart.Theyoungmanstandsupandwalksintheother direction.Shepicksuptheboy,swiftlyandwithouttendernessandplaceshimonthehalf-moonof herhip.Theboyrestshischeekagainsthercollarbone.Hisbodyiswarmandheavy,asawkwardasa boxorablockofwoodinherarms Still,itgivesherpause Softening,sheplacesherhandontheback ofhishead ‘It’salright,’shesays ‘Everythingisalright’

Frecklesofraindarkenthefootpath.Shelooksup.Awomaninapalesuitraisesherhandandrubsherfingers together,asthoughinspectingthetextureoftheair Anotheropensanumbrella Carefullybalancingtheboy,who reallyistoobigtobecarried,andclutchingthecrownofherhat,shestepsforward.

Theboy’sbootsbouncerhythmicallyagainstherthighs.Shepausestohitchhisslidingbody.Walks.Pauses.The situationisimpossible Shewondersifhehasalreadyarrived Sheimagineshim,standingbeneaththestation’s clocks,watchingtheslowprogressoftheunfamiliarrain.Sheimaginesthethought,smallatfirst,likeanitch,or thefirstintimationofaheadache,thengrowinglarger.HethinksIwillnotcome.

Shestepsoffthecurb Theshrill,competingcriesofthepaperboyspunctuatethesteadycacophonyofbellsand hoovesandfeetquickenedbythesuddenrain.Abicycleclangsloudly,thencurvesaroundher,asneatlyasaknife peelinganapple Shepressestheboytoherbody Sheislettingherimaginationgetawayfromher Evenifby somemiraclethetrainswereaheadofschedule,surelyhewillwaitforher.Fouryearsandallthoseletters.Andfor each,howmany?Three?Four?Enoughforhimnottodoubther. Still,shetriestoquickenherpace Theboyslips Shebumpshimupwithherforearm Heslipsagain Awoman glaresattheboyfrombeneathherumbrella.Shewantstoreturntheexpressionbutitishardenoughtoholdthe hatandtheboy,tomanagetheroadandtherain,thistaskthatitseemssheisfailing.

Whenatlastshearrivesatthestationherarmsaretrembling Shesetstheboydownonthefootpath ‘It’stimetobeabigboynow.’ Hisfacepuckers Shelooksatthestepsandabovethem,attherowofclocksthatmarktherhythmofthecity’s arrivalsanddepartures Sheisunsureofwhatmakesherwanttoweepmore,theboyortheclocks,orperhapsthe inexorablestepsthatrisetothestation’sthreshold.Shelooksbackattheboy.

‘It’sraining,’shesays

Theboylooksatthesky.Thenhecloseshiseyesandsticksouthistongue.Shewatcheshimcarefully.Hispaleface wrinklesandsmooths.Thenhelaughs.Shesmiles,relieved,andgrabshishand.

‘HowaboutIraceyou?’shesays ‘BetterhurryorImightbeatyou!’

Theboyclambersupthewetsteps,hissmallarmsswinging.Beneaththestation’stinrooftheairiswarmand close Shepausestoleanagainstawall Whensheopenshereyesamiddle-agedwomaninaplainsuitandstraw boaterasksifsheisallright Shenods,althoughsheisnotatallcertain Thewomanhesitates,andthenmoveson Theboypullsatherskirt.Hewantshertolookateverything.Shetriestofollowtheflitofhisfinger.Aman.Adog. Thebrightandpredatoryflowersthatleerfromdankbucketsatthestation’sentrance Shewantstosmilebutit seemssheisbereftofexpression.Shestraightensherself.Theboyfrowns.

‘It’stimetogo,’shesays.

Theboyfrownsagain Shegraspshishand ‘Yourfatherisabouttoarrive.’

Somethinghappenswithintheboy Sheexpectshimtocry,buthedoesn’t Instead,hisfacestillsandheinhabits himselfquietly,asoneinhabitsastranger’shouse Hishandinhersisasmallanimal,earspricked,eyeslargein thedarkness. Shethinksofhiscot,unusedinthelittleroombythekitchen,andhowthebedtheyhavesharedsincethedayof hisbirthwillbehisnomore.Shebendsdownandtoucheshischeek.Father.Eveninherownmouthithasthe tasteofaforeignlanguage.Shetriestoimaginewhatitmeanstohim,thiswordwithnothingtopointto.Her handsareempty Shedrawstheboyclose Atnightsheinhaleshisbreath,cradlesthesolesofhisfeet Shewill neverhaveherfillofhim.

Theboysighs.Herfingerstraverse,likethestonesofariver,thepathofhisspine.Shewhispersinhisear. ‘Everythingwillbeallright’

By Dr Lenny Robinson

Inanefforttokeepthisshort,Iwilltrytokeepacknowledgementstoaminimumhowever onceagain,thebeautyofTheStellaZinecanmostprominentlybeattributedtoTheStella Society'swonderfulandengagedmembers Thisloveforliterature,theawe,creativityand passionthat‘Love,Stella’createsseasonallyaroundtheschoolissomethingIwilldearly miss.Iwillmissourfive-minutewritingactivities,bookrecommendationsand heartwarmingStellaEvenings-however,equally,theseareexperiences,thatIamtruly thankfulfor.You,Stellamembershavemadethismagazinenotonlypossiblebutyouhave alsomadeitthrive.

Secondly,Icouldnottrulyacknowledgetheworkthatgoesinto‘Love,Stella’without acknowledgingMs.Sibley-whoseorganisationandpassionbringenergyandefficiencyto

Finallytoourreaders.Thankyou!IthasbeenSOIMPORTANThearingstaffandparents congratulatestudentsontheirpieces.Thepeoplewhowelookupto,moreoftenthannot, havethepowertogiveustheconfidencetocreate.Personally,myownbrilliantteachers haveenabledmetofeelnotonlysecureinmyworkbutalsoproud.Thisisanincredibly importantfeelingforayoungpersonandoneYOUcreate.Particularly,totheEnglish department-especiallyMs Huon-yourloveforEnglishdoesnotgounnoticedbystudents likeme.Wefeelthatlove,itshowsusthatthereisbeautyandworthinthereadingand writingthatwesoenjoy!Whatyouaredoingis,inmyview,undeniablyworthwhile.Lastly, tomymum-thankyou!Manyofuswouldagreethatourmumsareourbiggestsupporters (althoughfewofussayitaloudnearlyenough)sohereismywayofsayingahugethanksfor b i l i i j ithStella. tStellarites!