. re viv e

.पुनर्ज ीवन

.

a thesis by mehul sathya narayan

.rethinking informality in informal settlements

.preface

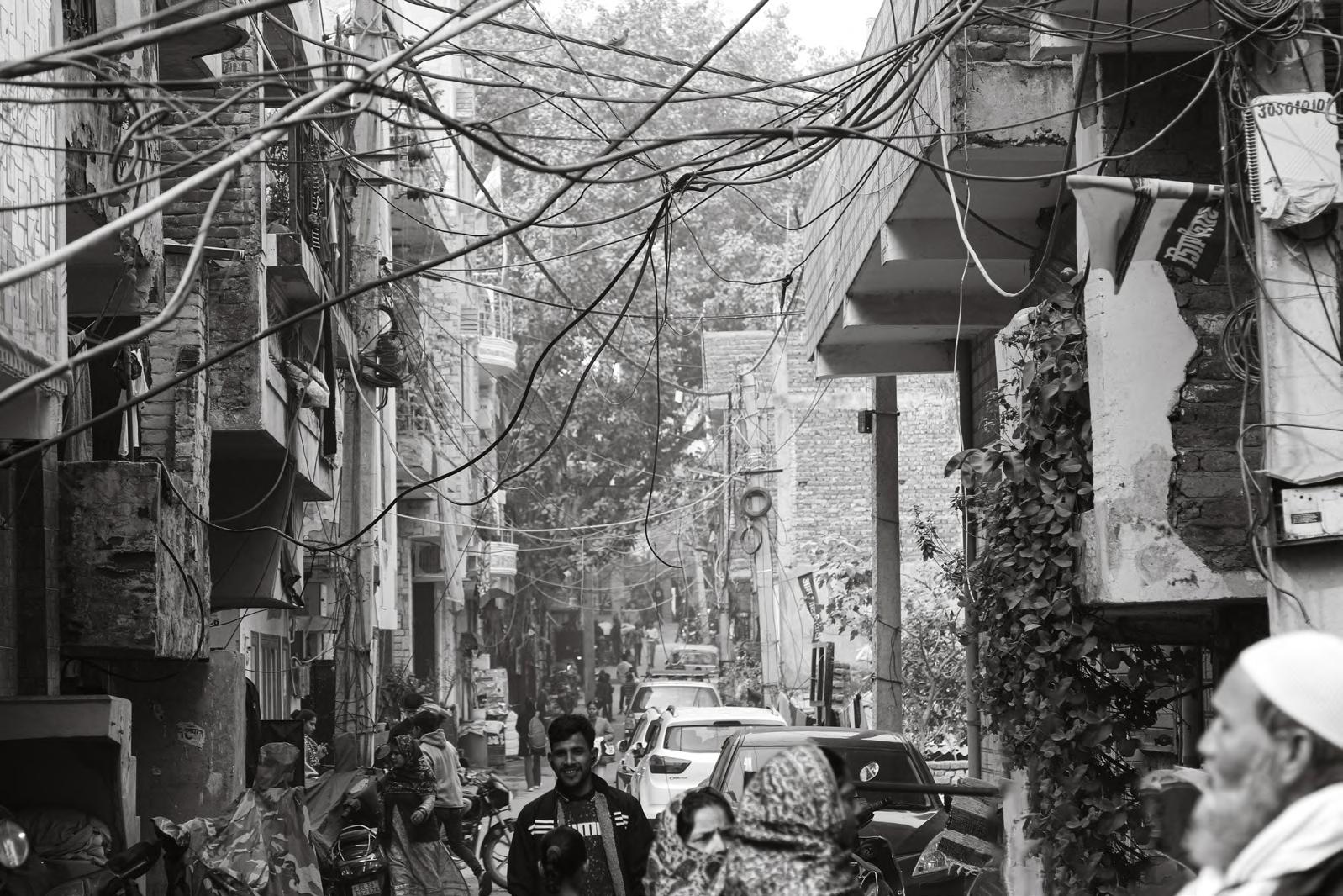

As you venture into the pages of this thesis, you are about to embark on a journey that traverses the many alleyways of Delhi, India, to a place often overlooked, yet brimming with life and potential—the slums of Delhi. This journey is not merely an academic exercise; it is a personal voyage of understanding, empathy, and ambition to reshape a narrative that has been neglected for far too long.

The focus of this thesis—the rehabilitation of Sangam Vihar in the city of Delhi—is not just about the physical transformation of a space, but it digs deeper into the core of social structure, economics, and cultural integration. This work aims to illuminate the resilience and tenacity of these communities and seeks to create an architecture that is not imposed but emerges from the very heart of their experiences and aspirations. This thesis is guided by a profound belief that architecture is more than just a profession; it is a social responsibility. It is about the empowerment of communities, the celebration of cultural identity, and the crafting of spaces that inspire dignity, safety, and aspiration. It is a delicate dance between preserving the rich tapestry of community life and introducing elements that foster growth, prosperity, and a healthier environment.

Through the lens of this project, you will find an exploration of innovative, sustainable, and community-driven design solutions that are not only practical but empathetic. Herein, you will find a dialogue between the old and the new, the traditional and the modern, and the complex interplay of culture, community, and architecture. This project is a humble attempt to contribute to the discourse on urban poverty, slum rehabilitation, and the role of sustainable architecture in shaping our societies. It stands as a testament to my belief that every individual, regardless of their socioeconomic status, has the right to live in a space that respects their dignity, fosters their dreams, and bolsters their sense of community.

As you traverse the pages of this thesis, I invite you to share in my journey, to question, to engage, and to reflect upon our role as architects in moulding a more inclusive, compassionate, and sustainable world.

.contents

.the designer .abstract

state ment the cube & grid relationship

.inspiration architectural principles analysis motiv ation

. proposal (WINTER) urban scale development micro scale development . reflection . bibliography

. the present defining a slum &world context Delhi‘s current scenario reality check . studies re-development strategies & informal settlements preced ents current scenario si te

.thedesigner

.about me

My name is Mehul Sathya Narayan. am Indian by birth, born in a country rich in its cultural heritage on September 10, 1999 in the beautiful ‘City of Gardens’, Bangalore. From a very young age, was fascinated by structures and constructions. My driving force to pursue architecture comes from the sheer creativity, diversity, and progress that are present within this field. In addition to this my passion for photography has helped me to master the skill of observing objects with a different perspective. want to help add and improve the quality of design and living.

My jounrney at Cal Poly as an architecture student has helped me not only find myself as a designer but also has transformed me as a person. My initial years were all about cultivating a design language that acts as a mirror of my personality and conveys that to the larger audience. My ambition to create ambitious and iconic architecture saw itself change to creating architecture that is realistic, pragmatic, and a solution to complex compounded problems that exist in society today. My ultimate goal as a designer is fulfil the philosophy of design for all and creating spaces that are accessible to people in areas that require it the most.

My senior design thesis project showacses my journey of learning through exploration, experimentation and expression, self-confidence, teamwork and a never-ending desire for more. It takes a deeper dive into my purpose as an aspiring architect by retracting back to my hometown, and understanding the complexity of a high density population with a different perspective, no longer from the viewpoint of a kid who ignored the possibilies of breathing life into these communities, but with the perspective of a designer striving to re-ignite a sense of revival and self-sustainability

.abstract

.introduction

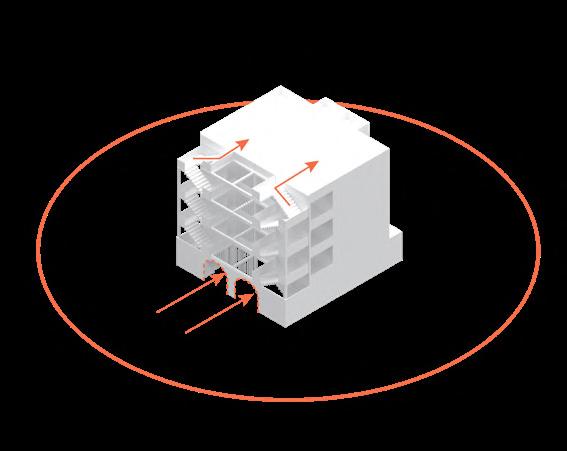

The term “revive“ means to return to consciousness or life. This project seeks to intervene in an area in the city of Delhi that has long been ignored, and has gradually declined further to a point where the existing urban fabric of the city has been heavily affected due to problems that exist within this region. My aim is to intervene in this region in two phases, first being the urban re-design and planning of this area at a macro scale, and then focusing on re-developing a certain core area of this region that can be used as a model for replication throughout this region as well as other similar regions spread throughout the city.

1 . statement

Moving into my final year of my architecture education, seek to further my learning of various architectural typoloigies and and disciplines while trying to further my knowledge of proposing solutions to complex urban issues. Throughout my last four years at Cal poly, the focus of my projects has been to maintain a balance between formal and spatial experiences while trying to give back to the community through humble yet future proof design solutions. Even though the scale of the projects for most part have been limited to individual buildings, my learning experience in third year double quarter design integration studio as well as my study abroad in Rome, allowed me to focus on projects that zoom out and focus on a larger urban area. And, this is something I want to further pursue and strengthen during my fifth year thesis project. The aspect of the urban scale will not only allow me to cultivate my interest in community projects but also allow me to recognize what it takes to create design solutions that have a much larger impact on the existing urban fabric.

Therefore, as part of my fifth year thesis, I seek to trace back to my cultural roots and hometown and tackle an issue that has not only worsened in the past two decades but has also affected the future development of cities in India. Delhi, the capital of India, witha staggering population of 30 million people is not only one of the most diverse and historically rich cities in the world but is also an example of some of the worst urban problems that exist in a city that is trying to progress by ignoring some of the most prevalent problems. Lack of organized urban planning migration into, and

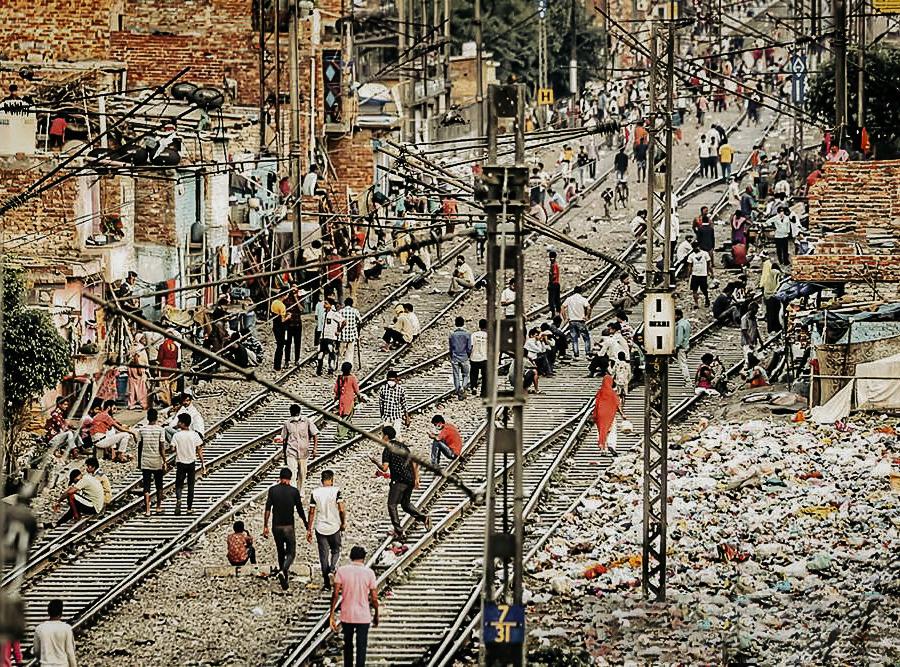

the ever growing problem of pollution has led to the stagnation of progress. However, the most major problem that is being ignored and has gradually been spreading across the city is the aspect of “slums.“ This has not only affected the overall look and feel of the city, but has led to a large part of the land available being occupied by un-organized slums that has affected the cleanliness, crime rate, and overall living quality.

The solution to this issue is not the eradication of slum areas, but to embrace these communities and re-think the idea of spaces for people living below the poverty line, and create a model that can be replicated, thereby improving the quality of life while indirectly improving the overall look and feel of the city. While the major solution to this problem is housing, it is not the only solution. It requires the amalgamation of housing with education and healthcare improvements. Therefore, through my thesis project, seek to research the existing condition of the problem and provide a comprehensive urban scale model for my proposed slum region in Delhi that involves the process of design thinking in housing education, sanitation, transportation and healthcare thereby improving the quality of life of these communities and eventually leWWading to the creation of new economic generators from these highly populated communities.

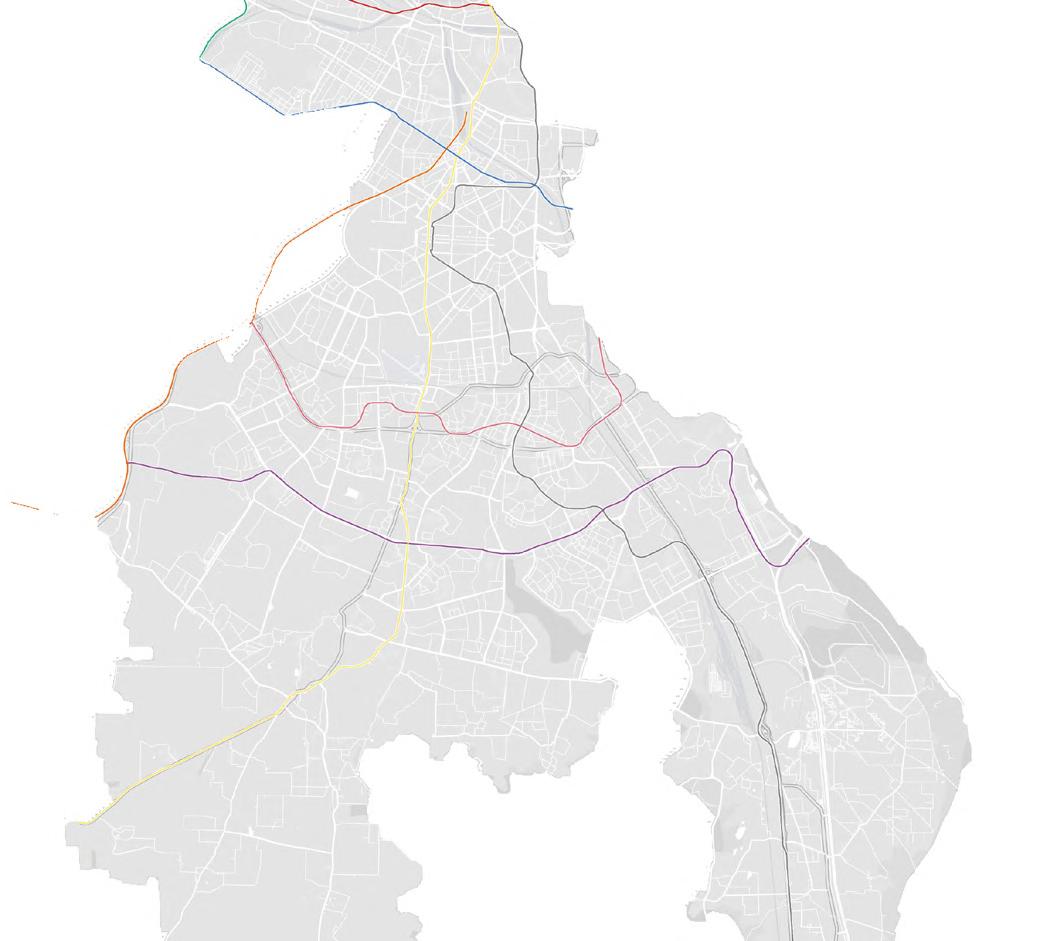

Slum Concentration in Delhi, 2020

.

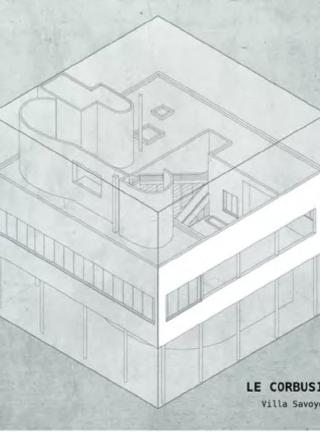

cube & grid

“CUBE”

- The Fundamental Piece of Architecture

The cube is one of those geometrical volumes that since the beginning of design. It’s a volume that is used as a reference to understand spaces as well as a tool for measurements. Most of the architecture that surrounds us is derived from this primitive volume with certain variations and modifications made to it. We also find the presence of cubes and cuboids in various activities that people from all ages enjoy like video games and LEGOS. However, the cube on its own cannot survive without it’s 2-dimensional partner, the “GRID”.

“GRID”

- The Organizational Structure of Architecture

While the cube might be more instantly visible to the human eye, if you take a step back and lift yourself above the ground, now you see a completely different world of flatness neatly organized by a thing called the “Grid”. This is most evident when one see an aerial view of city from an aircraft, or in everyday household items like an egg crate or an ice tray. Every single 3-dimesional volume in this world requires an organizing mechanism, and for design, this is most evident in the way cities are planned.

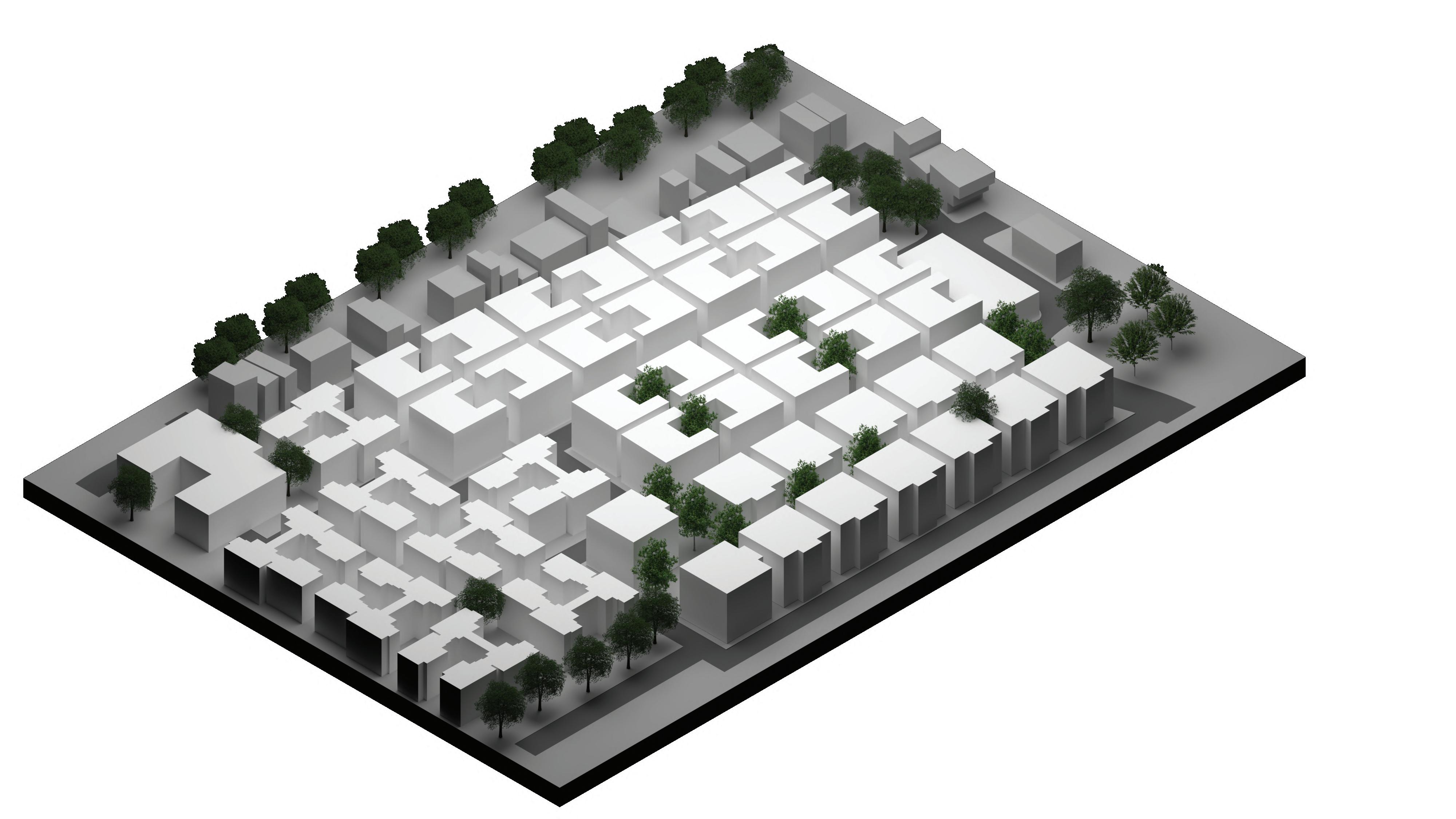

.comparative study (los angeles & london)

Conventional rigid city block with perpendicular intesections, high density and high-rise typology.

A grid system that strictly follows the cardinal directions along the X and Y axis for easy accesibility and navigations for the people.

In the case of Chicago (left), the end result is a city that is rigid in it’s organzation however very effcient in terms of naviagtion and understanding the overall patterns and spaces in it.

The downside is the lack of scope for further expansion, re-modelling and planning.

And, in case of London (right), it is a city that has a very dynamic and almost non-existent grid which most modernday cities take pride in. The lack of hierarchy in the height of the building also creates a situation where no one is above the other.

The downside to this organization is the lack of efficiency and navigational implications. It also creates this network of disorganized patch development which leads to a lot of unused wierd spaces within the city.

Low-rise city blocks organized into pie shaped slices with a lose arrangement of buildings, and with greater open pathways for pedestrian access.

The grid is considered to be “wobbly” and heavily affected by the river. The streets are seen to encourage and follow the movement of people like in Rome.

Grid Organization of Los Angeles, Milan, Paris, Delhi 2

“Effective design is a process requiring deep understanding of the history of a place – its culture, its topography and its vernacular.”

-Diana Kellogg

.inspiration

.introduction

The process of design acts on the philosophy of give-and-take. Successful architecture projects around the globe seek inspiration from what has been done in the past, and lays down principles for what is required and essential in the present. In this this section of my thesis, seek to lay down some design principles that are central to my design philosophy and further develop my understanding about essential architectural theories that still resonate around the globe.

Gyaan center, Thar desert, Rajasthan, India -by Diana Kellogg Architects 3

“Simplicity & Complexity”

3 . architectural principles

“ARCHITECTURE as a Transformative Engine vs. Form Follows Fiction”

Architecture as a practice is characterized by its diversity and the intention and purpose for which the design is carried out. Michael Murphy in his TED Talk titled, “Architecture that’s built to heal,” emphasizes the aspect of architecture as a service to serve the people that require it the most.. He makes use of personal anecdotes to lay the foundation of his design thinking thereby putting forward his argument that “good architecture” (referrign to the more ambitious and adventurous sculptural architecture) only serves a few and doesn’t really create architecture that is needed to solve more complex issues. Michael Murphy emphasizes on the need for engaging the local community in the design and construction of the spaces around them and encourage the aspect of ‘LO-FAB’ architecture as is evident in the Cholera Treatment Center in Haiti and The Illma Conservation School. By allowing the community to be part of the process, they create the stories and the purpose of the architecture around them rather than letting the architecture dictate their performance within a space.

In an oppossing argument put forward by the German Architect, Ole Sheeran in his TED talk, “Why great architecture should tell a story,” emphasizes on the importance of establishing new design languages and creating icons for a particular region. His design thinking revolves around the notion that “form follows fiction”, thereby presenting us with with the argument that, it is the architecture that scripts stories and the users are mere actors that peform the scripts of the stories. Furthermore, Sheeran puts forward the idea of treating architecture as “organizational structures”. He stresses that to improve the quality of life of people, it is important to design in a way that encourages human interaction and engagement rather than creating spaces that cultivate isolation. He gives the examples of the “Interlace” project in Singapore, the “Collaborative” cloud in Berlin, the Pompidou Center in France, and the CCTV headquarters in Beijing to support his argument and explain how complex circulation systems and public spaces allow for a greater impact on the quality of life of individuals.

Both the speakers talk about architecture in completely opposite ways in terms of the design drivers as well as the scale of the projects and their impact on the community. Both sides of the argument have their shortcomings, however, in terms of Sheeran, the practice of architecture seems to focus on creating icons and where the program has already been determined by a pre-defined “form.” Even though his design ideology forces us to think that this kind of architecture can be replicated, it cannot, and it seems to be out of context when considering the surrounding context.

On the other hand, the thesis put forward by Murphy focuses on the more functional aspect of design with no pre-determined form. The quality and use of space is dictated by the users putting them at the center of the design process and considers what type of architecture is essential to create a much bigger impact in the long run by proposing small scale interventions that fit more accurately with the surrounding context.

Architecture as a discipline comprises of diverse set of complexities as well as technicalities that has seen this discipline evolve in the last decade. Design is no longer something that is thought of on a blank canvas and then realized in real life with the help of ground-breaking engineering solutions. The arguments put forward by Robert Venturi and Marcel Breuer is something that most designers have trouble finding a solution to and in the end, land up in the middle ground when posed with question of integrating simplicity and complexity in the design process.

Where Marcel Breuer talks about the standardization of architecture in the ‘New Architecture’ that we see around us, Robert Venturi talks about the bland simplicity of architecture that most designers are focusing on in the current age. Marcel Breuer’s claim that ‘New Architecture’ is neither original, individual, or imaginative seems to be a bit too exaggerated and we all can agree to this in some extent or the other. His entire argument and stance are based on the fact that he does not appreciate the how architecture in the current age is tracing back to its fundamentals rather than focusing on design where ambition and passion can be the leading design drivers for expressive and more dynamic design. He also feels in that in the race for mechanized efficient designs, we have forgotten the include the cultural or handcrafted aspects of design. On one hand, where we can agree with most of his points of standardization in design and repetition across the globe in terms of what is considered as ‘good

design’, on the other hand, we can also disagree with his stance on the lack of complexity and expressiveness in design. Modern architecture in my opinion definitely traces back to what has been done in the past, incorporates it into the design process of the present, and creates the most efficient solutions to complex problems for the foreseeable future. While it might seem like every city around the world follows the same styles, but those architecture styles and typologies have undergone a far more rigorous and complex set of testing and problem solving before being used as the ‘norm’ for years to come. One can agree with his argument that the idea of setting or making an end-all-be-all style of architecture with no consideration for the future is definitely a major issue, however, by creating constant changes gives rise to an architecture where passion transcends logic, something which he aligns with but is not the most efficient architecture.

Breuer’s discontentment with the simple and standardized architecture is further highlighted by Robert Venturi as well who advocates for complexity and contradiction in architecture. He feels that complexity in architecture can only be achieved if one can integrate the ambiguity and richness that is found in art. Hybrid elements rather than ‘pure’, compromising rather than ‘clean’, distorted rather than ‘straightforward’, according to him should be the fundamental design drivers for design. Through this process he also tries to convince the reader that ‘more is no longer less’, and less and simplification

Image: courtesy of ArchDaily

Tirana Theater by BIG, follows the aspect of not conforming to standard conventions in architecture. The building has no relation to human scale and the building is made to fold upwards to just create a tunnel to pass through without any essential function. An example where logic does not act as the design driver.

in architecture leads to boring and bland design. However, we can disagree with this claim of his by considering the fact in modern architecture with complex issues, one needs to be very surgical as to which issues require the most attention and which do not. Architecture in the 21st century works in way of layers, where complexity is achieved with each new layer being added to the design process. Even though Venturi feels that there is a constant effort for oversimplification of architecture; what is not considered by him is the fact that the final product may not be as expressive and complex in its aesthetic, however, the pathway that was taken to reach that final product is way more complex than any architectural icon of the past where the main intention was to create something that was meant to create a distinct memory of a place rather than focusing on the true purpose for what it can be.

San Pellegrino Factory by BIG, tries to go against Venturi’s argument by proposing a a simplistic primitive geometry as the ‘arch’ which can be interpreted as just an aesthetic or a bridge that of tunnels. It is a simplistic form where the complexity is derived from the meaning it imparts to the architecture.

Image: courtesy of ArchDaily

The Mountain by BIG, showcases a balanced approach where a simple form through gentle moves like twisting and raining to allow for sunlight for each apartment units provides the users an equal experience. the twisting helps define the apartments units and the slight use of colors helps in creating the hierarchy of levels. the different aspects create a kind of complexity when combined together.

Image: courtesy of ArchDaily

“Ornament & Crime”

Art and architecture throughout history have given recognition to cities and nations around the world. Not only have they allowed people to understand a place and its progression throughout history, but it has allowed visitors from other regions to immerse themselves with culture of that region. Architectural icons like the Roman Forum and the Colosseum in Italy, the Palace of Versailles in France, the Pyramids of Egypt, and the Remains of the Indus Valley Civilization in India, have all contributed to the recognition of these regions on the World Stage, and one can easily relate to the history of the region by visiting these icons. However, the architecture of the past has one thing in common, and that is the aspect of “ornamentation.” The plethora of statues carved out of stone on the exterior of religious buildings in India to the intricate Corinthian columns that form the basis of majority of Italian and Greek architecture is perceived by us as ornament and decoration in the field of architecture.

With the advent of the 20th and 21st century, architecture and design has moved away from the traditional norm of over-decoration and overornamentation, and has shifted focus towards simplicity, efficiency, and functional design. Adolf Loos’s argument that “the evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornamentation” is very valid in today’s modern-day cities. He provides an analogy of the Papuan who covers his skin with tattoos is not seen as a

criminal however, the modern man if does the same is seen as a criminal or a degenerate. Anything that is not necessary or is extra is seen as redundant or a “crime” in Adolf Loos’ words. Most of the objects or intricate designs created by people in the past, now merely exists as ruins, with certain cases where they are cleaned and maintained but never seen as something that imparts value to the modern age. He further goes on to give examples of how cities with white walls will soon be appreciated and how eating a plain piece of gingerbread is better than the ones shaped like a heart, or the ones covered with decoration. Adolf Loos tries to convince that in the present day and age, the simplest form of things are appreciated by people without the “extra” factor. He argues that ornament today, just makes things more attractive and in some cases more expensive, however, the amount of time that is invested in producing an ornamental object or design is way more than something that is simple. Ornament in his vision is sign of “wasted labor and hence wasted wealth.” He therefore describes ornament as symbol of backwardness and something that can be associated with people at the lower end of the social strata, as the people producing it are not compensated fairly. This is very evident in more developing countries where handcrafted goods still have a wide-ranging market, however the cost of those goods are always lower than something that has been created by a

machine with the same materials but in half the time devoid of any ornamentation.

Corinthian Columns as an Architecture Standard in Italian and Greek Architecture Ancient Indian

Furthermore, ornament throughout history in architectural design was meant to signify a certain period in the history of a region. Ancient scripts inscribed on the walls, statues carved out of stone, intricately designed columns, and the over-exaggerated scale of certain architectural elements, all added to the narrative of a certain culture and lifestyle of people. With the passage of time, newer ornamentation gave rise to newer styles and added to the layering of different periods that till date allows people to understand the essence of a place. However, in the past two centuries, this aspect of ornamentation has become less and less evident. Loos argues that the ornament created these days has “no parents and no offspring, no past and no future.” Ornament in today’s architecture is rare to find unlike the past where the ornament was the architecture. The popular notion that “form follows function” has gained more and more emphasis in today’s world of design when it comes to architecture, and that is what Adolf Loos portrays as “architecture without ornament” which more and more people view as the gold standard in architecture today.

While Adolf Loos’s arguments are valid to a certain extent, I feel that his ideologies and opinions about ornamentation are too extreme and outdated, and it feels like, a lot of important aspects that makes up the modern movement in architecture have been neglected. While we all perceive ornamentation like it used to be in the past, the modern movement in architecture proposes a different kind of ornament and complexity. Ornament in 21st century comes in the form of problem solving and environmentally

friendly solutions. The detailing of new structural systems, innovation in material science, automation of the architectural production process, and increased emphasis on reducing emissions and incorporating more ecofriendly sustainable systems in the form of façade design, HVAC systems, and daylighting all form the system of highly complex but functional ornamentation in modern architecture. Even though these forms of ornamentation in architecture are not very explicit and don’t really inform the user about a particular culture or history of a place, their focus is more towards enhancing the userexperience and improving the overall function of a space. Even though, Adolf Loos tries to convince that the future of architecture is bleak and mundane, on the contrary, the design process in architectural practice has never been more complex and sophisticated. Furthermore, with this sophistication, comes more cost especially in terms of the procurement process of materials as well the construction phase of architecture where un-realized reality finally becomes a reality. Therefore, one can say that architecture in the modern era strikes the perfect balance between ornamentation and function with varying degrees, but the end goal of today’s architecture is not to represent the past or the future, but instead allow its users to create the narratives and stories associated with a space.

4 . motivation

The motivation to undertake a slum rehabilitation project in a dense city like Delhi, is something that has been cultivated throughout my architectural education and learning and seeking inspiration from existing architectural projects that strive to create a difference on a larger scale. Having grown up in a city where the boundary between the wealthy, the middle-class, and the people living below the poverty line is close to non-existent, one is able to observe how the poverty striken areas in the city have been completely ignored. The race for modernization and urbanization and modernization has created a situation of gentrification which in the case of Delhi has forced people at the lower end of the income spectrum to form these undeveloped groupings of areas called “slums.“ These slums have in turn created a wierd situation around the entire city by affecting the urban fabric as well how essential resources can be made accesssible to the people living in these slums.

My aim through this urban re-developement and re-habilitation of an existing slum is not to follow the conventional approach of tearing down these areas and causing displacement of the people living in these areas. But, it is to rather identify key problems that have affected these areas, and trying to integrate them into the existing slum area. Working with an existing canvas and trying to enforce infrastructural improvements through sustainable architectural practices is the end

goal of this project while tackling key issues like housing, sanitation, and transportation.

While the focus is re-developing and creating architecture that helps in the healing of these communities (as relevant in Michael Murphy‘s TED talk), the goal is to also allows users to be at the center of the spaces that are created and allowing them to add character and significance to the architecture. Furthermore, while ornamentation in the modern era is seen in the form of complex energy efficient systems in most modern day cities, the biggest strength of the historical architecture in India, is the use of decorated ornamentation as a system for daylighting and ventilation. By adding elements of vernacular architecture of the past to the existing infrastructure of these areas, where people are still in sync with culture and tradition will also allow me to help create these areas as cultural hubs within a sprawling mega-city that allows people regardless of social status to re-connect with the past and understand the significance of different areas throughout the city.

The ultimate purpose of good architecture is to heal communities that require it the most and to help create a unique identity that give these communities imprortance and the opportunity to be recognized and accepted into society.

Brise Soleil System in Office Building by AQSO Arquitectos

Park Royal Hotel Green Garden Terraces in Singapore

3D Printed Architecture by Yanko Design

.thepresent

.introduction

To propose an intervention in a densely populated “slum“ area, it is important to understand the defintion of a slum as well as the complexities and issues that come with it. My goal is to identify key issues associated with slums on a global basis as well as my proposed area of focus through existing survey data and real-life experiences of the slum dwellers in my proposed site.

5 . defining a slum

What is a SLUM ?

The word “Slum” refers to informal settlements within cities that have inadequate housing and squalid, miserable living conditions.

Further diving into the definition of a slum:

1.6 Billion people live without adequate shelter

1 in 7 people on the planet live in a slum

1 in 3 urban residents live in slums in developing countries

In some countries, 90% of the urban population lives in slums.

Major developing cities where slums are one of the main types of housing are Kibera in Nairobi, Manila, and New Delhi. Major characteristics of slums include:

- Unsafe & unhealthy homes (lack of windows, dirt flooring, leaky walls and roofs)

- No access to basic services: water, toilets, transportation.

- Unstable homes and no secure land tenure.

Major hazards in slum dwellings?

Why do slums exist ?

In the 21st century, the population rise in most cities is increasing at a pace where cities are unable to repond to the needs of the housing.

As a result, low-income families are being evicted by force and pushed to the edges of the cities to un-planned and poorly serviced areas.

However, in Asian countries these unplanned and poorly serviced areas have been forming in patches within the major city areas which has created many obstacles for future urban planning and development.

Health These settlements are not well connected to basic services like clean water, sanitation, and hygiene. high population density and lack of proper toilets leads to widespread diseases.

Safety & Violence Emergency and law enforcement vehicles are unable to access these areas due to narrow pathways and unorganized roadways. Un-sound construction creates hazards for inhabitants and affected by natural disasters like floods, fires, earthquakes and landslides.

Un-Employment lack of a formal address causes obstacles in finding jobs.

Disconnection Lack of public transport hubs like bus stations, trams, metro lines due to tight and un-feasible roadways has led to these areas being inaccessible leading to no proper distribution of resources.

Across the GLOBE (Journey to Kibera, Manila & Mumbai)

Dharavi, Mumbai, INDIA

60% of Nairobi’s population lives in slums and around 250,000 people in Kibera making it the biggest slums in Africa and one of the biggest in the world. Most of the structures are made out of mud and corrugated metal for roofs. 20% of the people have access to electricty. Other major problems include lack of toilet facilities (1 toilet per 50 shacks), lack of water supply, medical facilties, increase in the usage of illegal drugs, unemmployment rate of almost 50%, and increased disagreement between tribes.

35% (3.4 million) of Manila’s population lives in slums. The slums in Manila re home to some of the highest rates of childhood malnutrition in the world (50% of children are found to be anemic). Other major issues include lack of sanitation (66% people do not have access to proper waste disposal, and only 16% children have access to clean water), increase in diseases due to lack of drainage, and vulnerability to natural disasters due to temporary and unstable infrastructure.

It is regarded as one of the third largest slums in the world with a population of 1.2 million people. Like other slums in the world, sanitation is one of the key issues that is prevalent here as well. There is an everage of toilet for every 1,450 people. Furthermore, while most slums around the globe have high rates of unemployment, the Dharavi slum despite its challenges produces a revenue of 650 USD/yr making it the most productive slum in the world. The goods produced here are sold worldwide, and people mostly run their business on digital platforms.

Kibera, Nairobi, KENYA

Manila, PHILIPPINES

6

. Delhi‘s current scenario

Delhi: A dichotomic reality!

The word “Dichotomy” in true sense means, choosing between two antithetical (opposite) choices. However, in some cases there are no choices that one can choose from, one particular case being the city of Delhi, also known as the Capital of India.

India is one of the fastest growing economies, with a population of more than 1.2 billion people, 30.7 million of which live in the capital capital city of Delhi. The city is generally seen as a symbol of power and wealth due to the existence of the governing bodies offices including the Parliament as well as posh communities and a central location for major events. However, within the city, people are also battling to survive without bare necessities. There is a strange system in how the impoversihed people are isolated from the rich. Opulent retail centers and cafes surround the slums and and some slums are sandwiched between rich neighborhoods. Poverty in Delhi, hidden between the cracks of luxury is very different from the overall picture of the city as a whole, and something that is becoming a major concern.

To understand the problem of slums, it is improtant to understand the dichotomy that has been created in the urban fabric of the city. Delhi is regarded as one of India’s most prosperous cities with an estimated GDP of $293.6 billion (as of 2022). The trypical delhi resident earns “three times” more than the average Indian. However, for instance, within one of the most affluent communities in Delhi, Vasant Vihar, there is Kusumpur Pahari, a hub of poverty and almost 10,000 slums. People living in this area live in small and densely populated spaces, and lack the necessary resources to live a stable life. And, to further add to the poor planning of the city, is the presence of Delhi’s biggest shopping mall and its 102 meter high civic center. This lopsided condition exists throughout the city and has forced the people in these slums to work for the elite without much reward and improvement to their living conditions.

Before understanding the complex reasons that contribute to the existence of slums and the life of people in these slums, it’s also important to understand where these slums exist throughout the city and how each one of them differs from each other.

Is home to Migrants from U.P, Bihar, Orissa, and Assam. Dwellers here work as drivers, gardeners, and housekeepers for their wealthy neighbors. People most live in one-room shacks with no water. The only improvement has been seen in terms of the availability of freshwater through trucks every several days.

MADANPUR KHADAR

Located in the suburbs of Delhi, narrow streets and sewage lines run throughout this area affecting the dwellers. People most collect and sell rags. The major issues here include polluted drinking water and sanitation.

However, since 2018, NGOs have taken note of this area and have started creating more awareness through internet. “The dichotomy not only exists in the way the city’s urban fabric is, but also in terms of the life of people living in these different slums.”

This is the area of focus for my thesis. It is a slum community that houses people from neighboring states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. It has no freshwater access and a lack of community toilets, which has led to open defecation, leading to snaitary concerns in the area. The increased poverty and lack of awareness about this area has transformed Sangam Vihar into a refuge for thieves and brought rise to gangs who are willing to kill for water.

Kathputli colony can be regarded as the entertainment slum of India. People here are mostly illusionists, puppet masters, and other types of entertainers. It is also known for its colorful buildings and roads bustling with street performers. India, generally likes to hide its slums, however, whenever it wants to showcase its culutural prowess, it showcases this particular slum. In contrast, Seemapuri is seen as an example of extreme poverty in Delhi. People struggle to find proper sanitation, water, and electricity. People here reside in mud dwellings and fetch contaminated water from exposed sewers.

KUSUMPUR PAHARI

SANGAM VIHAR

KATHPUTLI COLONY & SEEMAPURI SLUM

Delhi’s Slums

City Center, New Delhi

SANGAM VIHAR

KUSUMPUR PAHARI

MADANPUR KHADAR

SEEMAPURI SLUM

KATHPUTLI COLONY

SLUMS: An outcome of rapid urbanization

In the year 2009, the first time in human history, more people lived in cities than in villages. This process of urbanization has been celebrated due to the associated rapid rise in productivity and thereby GDP growth, especially in counties like China and South Korea. However, there are instances of urbanization without Growth, such as in Brazil and certan African countries, where the quality of opportunities in cities rather than the quantity of people determines economic development. However, one such instance of a place where regardless of the rise in GDP, the quality of life for a large number of people still remains sub-standard or even not feasible is India.

In 2011, 377 million people in India lived in cities, but of these, 65 Million (27% of the urban population) lived in extreme shelter poverty in areas called “slums.” This challenge however is not just unique to India, 863 million people around the world live in similar settlements. India and China have the highest number of slum dwellers, with 50 million plus inhabitants living in acute shelter poverty.

In the case of India, and more specifically the city of Delhi, due to increasing population and the lack of affordable housing in the city, the number of slums continues to increase, while basic public services provided to dwellers of these slums continues to remain almost invisible. There are several reasons for such low level of services, including a low tax base of urban local bodies, poverty debt traps, and a lack of informed voting. Local

governments or state governments in India operate with very low tax bases, where eight of the largest 21 cities ar unable to finance even 50% of the municipal costs. As a result, informal districts (slums) of the city are worsthit by low service levels. If the slum population is largely informal and tax non-compliant, local governments see little incentive to spend money on increasing their service levels. This is evident in visible open drainage lines, and lack of streetlights, roads, household toilets, and garbage collection services. This has led to major public health issues such as open defecation and the presence of unsanitary waste adjacent to houses. Various studies correlating health outcomes to the built environment found that children living in urban slums in India have stunted growth compared to non-slum urban and rural children.

The health effects on slum residents have shown to vary by several factors including number of years living in the slum, presence of a separate kitchen, type and permanence of the shelter. The extremely dense housing also causes communicable diseases to spread rapidly.

Market Failure and the Demand Side Supply Side

Most studies done in India have highlighted slums as a problem that need to be fixed however, some recent studies have also tried to show how slums are a space for entrepreneurship and provide accessible affordable housing for urban migrants. There are multiple reasons for the growth of slums including rapid urban migration, urban governance, and the housing demand-supply gap. While all the factors contribute to the slum formation in certain degrees, housing demand and supply remains central to the formation of slums in most Indian cities especially in the capital city of Delhi.

The gap between growing demand for affordable urban housing and insufficent supply has encouraged the formation of slums. Whenever the demand surplus is not met by formal sectors, this gap is typically filled by an informal dwelling such as a slum. While a slum is better than nothing, it cannot be compared to housing that is safe, clean, and secure. This whole supply and demand chain has prevented suffcient affordable housing for the urban poor, stimulating slum formation.

Talking about the real estate market in India, it has always focused on serving the needs of the urban rich, households with monthly income greater than $700 (60,000 INR). At the base of the income pyramid, a typical double-income slum household can only earn up to $100 per month. The Government of India reports that there is a shortage of about 19 million homes in urban India, 56% of which are from

from EWS (Economically Weaker Section) households with monthly income less than $300 (25,000 INR). In addition to the unmet demand for housing, the slum dwellers also lack the access to formal financial resources to help them purchase new homes or maintain a new life in a housing unit. To add to the trouble of the slum dwellers, Housing Finance Companies only serve the midto-high income families and are hesitant to serve the informal sector due to the high per capita costs of serving this section. A large majority (65% - 70%) of the workers in urban areas are working in the informal sector, and since they are paid in cash and lack collateral, formal records of identification, address and salary, they continue to be under served by the HFCs.

A well-established pricing rule indicates that a household can afford a home priced below a forty-month income. Therefore, to put that in context, slum households could only afford to buy a unit cheaper than $4000 (4 lakh INR). However, current private developers fail to provide decent housing at this pricWe, and instead a typical 269 sq.ft unit costs between $6030 and $8400. The supply of affordable housing that a slum family can afford is limited due to lack of available urban land, rising construction costs, and other constraints.

LACK OF AVAILABLE URBAN LAND

RISING CONSTRUCTION COSTS

In the past 15 years, India’s urban population has increased by 45% (in the case of Delhi by 97.5% according to 2012 census), and it is further estimated that 40% of the population will live in urban areas. Careful urban planning helps in the urbanization process. But, excess control over land development in most Indian cities has created an urban land shortage leading to urban sprawl and corrupt practices in land licencing. Due to this factor, slum and temporary settlements are on the rise in most urban areas as these kind of settlements are unauthorized and try to acquire land without going through the legal process that is bound to not favor the slum dwellers.

In the general hosuing market, the largest driver of cost in private development projects is land costs, however, in slum redevelopment projects, where land cost is alnost non-existent, then the largest driver of the final project cost is construction costs. However, the estimated construction cost for this housing is about ₹800 per sq. ft., accounting for more than half of the final price. The construction cost has increased about 80% in the past decade. Due to this reason private developers alone are not able to deliver affordable housing to the market, leaving the infrastructure of slums almost non-liveable while also forcing other migrants to look for low quality housing in established slums.

Source:

Urban Income Pyramid & Housing Shortage

Ministry of Housing & Urban Poverty Alleviation, 2012-17

7 . Sangam Vihar: an untold story

Stereotypes of Slum Dwellers Sangam

For more than two decades now, the city planners of Delhi and the urban elite have been preoccupied with the in-migration to Delhi. These migrants usually constitute cheap labor in search of housing, services, and urban infrastructure. However, there are many stereotypes that have developed over the years about “these others” and have been considered as a threat to the environment. Migrant slum dwellers are portrayed as young, backward, illiterate, and uprooted men coming to Delhi in search of unskilled work. They are considered as illegal encroachers of government land (which in the case of Sangam Vihar is true due to the reasons of slums formations discussed above), pollutors of the environment, and thieves of electricity. The slum area(s) is considered as breeding places for everything evil, such as crime, alcoholism, drug trafficking, and prostitution. Due to lack of clean water, sanitation, garbage collection, and sewerage they represented a potential threat for the city hygiene and spread of water and air borne diseases, such as cholera and malaria. All these factors have forced governments to consider demolition instead of rehabilitation.

A “dingy backyard” quite perfectly can be used to describe the area of Sangam Vihar due to constant neglect of this unauthorized zone. This area lies in the outer part of Delhi, and is considered to be one of the least prestigious but the fastest growing political constituency.

Despite people having lived there for many years, the risk of demolition has made people build fairly modest one, occasionally two, storey houses in mud or brick. Families of five and six live in one or two rooms houses, more congested than Indian health norms permit. Despite constituting an urban living area for almost three decades, Sangam Vihar has no proper road system and few paved roads, no drainage, sewerage system or garbage collection, and most people rely on private or collective solutions for water supply, electricity, health and education. The area is flooded and muddy during the rains with smell of cloak and uncollected garbage.

The municipal government, reflecting unwillingness to invest limited city resources in the development of illegally occupied land, and that demolition was and is its preferred strategy, having neglected the slum

dwellers potential rights to basic services.

First, following the partition in 1947 (and the formation of Pakistan), many well-off Muslim families with large properties in their posession since the Mughal and british period, fled from this area of south Delhi, leaving land vacant in an area that was already sparsely populated. Following the civl war, many of the newly arriving immigrants from todays Pakistan settled in these Southern areas, occupying land, and lay the foundation for peri-urban townships and new communication infrastructure. During this period, delhi’s population almost doubled as it was an active site for refugees as well.

Second, the hosting of Asian Games by the city of Delhi in 1982, in major ways demanded construction workers for new housing, sports arenas, and communication infrastructure in Southern parts of the city.

The area once belonged to the “old city” of Tughlaquabad, established by early Mughal emperors. The ancient and mighty ruins could still be admired across the main road North of the living quarters. Bordering on the Southern side, was a green and huge forest along a ridge. In the past, this land served as crop land, forests, and pastures for the buffaloes of Gujjar nomads, and provided milk and meat for the emperor and later for the British colonial administrators. Around two decades ago it was also a buzzling, dynamic, and evolving housing and business zone. These general factors also led to people moving to Sangam Vihar. However, to understand the whole process of in-migration into this region, it is important to consider three important historical events, events that were related to political and economic factors and local demand for labor.

Third, new industrial zones were established during the 1980s and 1990s, including the nearby Okhla industrial area, which grew in importance as the economy responded to new global markets for Indian made garmets. Through these developments, the market for unskilled labourers kept growing. New middle-class living quarters also increased job opportunities in the private service industries, for shop keepers, craftsmen, domestic servants, guards, and drivers.

Vihar : a dingy backyard

The History

Vihar : where life is struggle

. reality check

Stereotypes of Slum Dwellers by Urban Elite

Status and Backward (caste system)

the Environment

(burden on

Reality of Livelihoods among the average slum dweller in Sangam Vihar

literate; higher than Delhi Average (82%)

More than 80% middle-or-high caste, higher than for Delhi average

employed - mainly in informal private businesses

Average income about Rs.3000/month ($38), more than that of official poverty line (65% between Rs.2000 and 3000)

Majority still owned crop land at native place (61 percent)

Majority possessed or 2 room brick house (pucca)

Majority owned TV, Radio, Fan, Bicycle

Only 2% had connection to government source, since very few transmission lines present

No sewerage, hence, contribute to water pollution. Depletion of groundwater is a problem. Consume little and produce little waste. Yet, lack of sanitation and open defecation is a problem.

Income of household slightly above consumption but not enough

Majority of people in Sangam Vihar perceive lack of electricty and water as key problems. Other major problems include lack of paved roads which has made the area less accessible by public transport and other small modes of transportation. Even though lack of sewage system and waste disposal is a problem that is perceived byt the government, it is not the top priority for residents of this area.

People in the past have formed groups and raised their voice to request for basic sevices, however, due to government inaction, a lerge chunk of the residents have formed their own water management groups. The groups are mostly organised on street basis: one group assigning a member to manage a tubewell to which they all would connect and pay a monthly fee. These few tubewells are in most cases constructed by a local NGO, private individuals, or occasionally by the government. Even after these efforts, only 10-20% of the people have access to tapped water.

When it comes to electricity, only 2% have access to government source. While majority have access to electricty through private generators, the high costs makes it unfeasible for the slum dwellers. Furthermore, the problems in Sangam Vihar don’t stop with lack of basic services. The inadequate number of public schools in the area, most people have to send their children to private schools. The health services are also provided by private doctors in under-developed clinics and hospitals

as well as NGOs which focus more on mother and child care.

Monopoly on distribution of services

The government bodies in Delhi give the excuse that there is a crisis in the supply of electricity to the city. They, therefore, argue that the large numbers and illegal encroachments by slm dwellers is to be blamed on the overburdening of the total electrcity supply. There is also the notion by the Delhi electricity board that majority of the electrcity is stolen by the slum dwellers, however, studies show that the irregular supply of electrcity is in fact more pronounced in the low-cost housing and slums. For instance, out of a supply of 3000 MW about 80% is consumed by the residential areas, buisnesses and industrial centers: with the middle class consuming a large share of the electricity. Some studies also show that most of the illegal electrcity is used by the industrial zones and middle-class households, and the equipment used to monitor the electrcity is faulty therefore causing an uneven distribution around the city.

Apart from electrcity, water is another essential everyday resource. The government bodies in this case as well have the perception that slum dwellers are responsible for the water crisis in the city. In Delhi, 90 percent of the water supplied is for domestic consumption. But while average per

capita water consumption in Delhi is about 350 liters per person per day –the average consumption per capita in the slums is about 35 liters. This directly points towards the fact that water is disproportionally supplied to the middle-income area and non-slum zones. In the case of Sangam Vihar, among the water management groups, the norm is set to 60 liters of water per household per day. Some people have access to official water supply, and some people would bargain with other groups’ access to the common shared resource. The water quality however is contaminated due to lack of sewage and sanitation.

Seeing this the Supreme court over the last couple of decades has passed an order blaming the Municipal corporation of Delhi and the lack of coordination between local and state governments for organized urban planning in Delhi. However, for the slum dwellers of Delhi once again were placed at the center of attention and held responsible for the garbage and pollution in the city and the Supreme Court to prevent further illegal encroachment and formation of slums in the existing city fabric, has stuck to it one -and-only solution that clerance of slums is the only path forward to creating a “hygenic” and “clean” Delhi; following the failure of the “relocation intiatives” that were taken in the past.

Sangam

.studies

.introduction

Slum redevelopment projects have a diversity of strategies that are successful and unsuccessful based on the surrounding context, the local policies related to urban design and planning, and what the residents living in these areas desire. Therefore, it is important to understand these strategies as well past projects that have been either successful or un-successful, in order to propose future improvements to existing strategies with greater effciency and enduser satisfaction.

9 . re-development strategies & informal settlements

of Slums

This methodology of slum redevelopment first came into existence in the United Kingdom and the United States to redevelop London and New York City, which were interspersed with squatter settlements. The policies in these cities forced local councils to initiate mass slum clearance, demolish poor quality housing, and replace with new building which most of the times were not meant for the existing slum dwellers, and was focused more towards the upper and middle class society due to the cost of these programs. As a result of these slum demolition programs (one in particular being the Slum Clearance Compensation Act of 1956), by 1979, 1.5 million dwellings had been demolished and more than about 3.70 million people had been relocated. Over the years, this concept of Slum Redevlopment has become very popular in most regions around the world as it takes away the massive costs of relocating milions of slums dwellers.

Several policies around the world in the past show the success and failures of this type of redevlopment. The most noticeable ones include the US Housing Act of 1949 and BSUP India 2006. While

the Policy in the US focused on creating new public housing on cleared slum land, on the other hand, the policy in India focused on providing basic essential services like water, electrcity, sanitation in improved housing.

US HOUSING ACT 1949

This Housing Act of 1949 shows similarities with the Housing for All policy adopted by the Government of India in 2015. The US Housing Act of 1949 aimed at provide a decent home to every American family by 1955 by redeveloping slum areas and construct 810,000 units of public housing. Federal government incentivized local government to use their powers of eminent domain to clear and then sell parcels of land in blighted urban areas for either public housing projects or for urban redevelopment. It also provided federal grants and loans to create public housing with low rental rates and construction cost caps. These two features of the scheme were most controversial, because of the social cost it caused(racial segregation and large scale relocation of 300,000 families). All of this led to substantial

delay in achievement of the goal, and it took 20 years to complete construction of all housing units.

The achievments of the program include:

- Efficient Land Use: 57,000 acres (90 square miles) of pure residential area was redeveloped to create public amenities and places for commercial use. 35 % was used for residential redevelopment, 27 % was used for streets and public rights-of-way, 15 % was used for industrial purposes, 13 % was used for commercial purposes, and 11 % was used for public or “semipublic” spaces.

- Economic Growth: A $100 per capita difference in grant funding was associated with a 2.6 percent difference in the 1980 median income and a 7.7 percent difference in 1980 median property value. Thus, mandatory investment in urban redevelopment along with construction of housing can lead to overall investment in the builtenvironment and improved quality of life for slum residents.

Challenges and failures:

- Vertical Design: high-rise public housing was criticized, lack of social spaces in the new proposals were chided.

- Quality of Construction: most of the times governments looked towards private developers for affordable public housing, however, due to intensive costs that go into relocation of slum dwellers, the private developers provide substandard housing.

- Excessive Relocation Costs: Even though the slash and rebuild technique helped in the overall economic development of the area. However, the social cost of relocation became too much to handle due to which future slum interventions focused on minimizing this.

this program was to provide security of tenure at affordable prices and improved housing, water supply, and sanitation, it ultimately became a housing construction program subsidized and implemented by the government. Government agencies estimated the housing unit cost as $3631.77 and decided to provide a housing subsidy of approximately 88%, with the remaining 12% contributed from the end beneficiary. BSUP failed to take into account the limited capacity of government for implementation of such a project. Limited local government capacity resulted in poor monitoring during the construction process leading to poor quality housing. In the case of Bhopal (in the state of Madhya Pradesh), the housing was so poorly constructed, with dark alleys and leaking pipes that slum residents refused to move in, and in this case overall take-up rates by original inhabitants was less than 30%.

This program was started as part of a larger scheme called JNNURM, a large scale urban renewal program for urban India. SUP aimed to provide basic services to urban poor in 63 of the largest cities in India by population. While the original intent of

The BSUP failed due to poor quality housing and lack of transparency in the costs. Project delays led to escalation of prices, and exceeded intial estimated. For example: the beneficiary share was estimated to be $420, but by the time construction was completed, the cost escalated to $690. Therefore, these units became un-affordable and are currently standing empty. The total amount spent on housing under the program was approximately $32 billion.

Clearance

BASIC SERVICE TO URBAN POOR (BSUP, 2006), INDIA

Slum Occupied Land in the USA, 1900s

High-Rise Public Housing as part of 1949 Act

The cycle of razing slums continues

Slum Upgradation

Following the problems associated with slum re-development (clearance of slums), most countries in the world have adopted a new model for slums known as “slum upgrading.” This is an integrated approach that aims to turn around downward trends in an area. These downward trends can be legal (land tenure), physical (infrstructure), social (crime, education) or economic. This method is not only about water, drainage, or housing. Rather it is a more holistic approach incorporating economic, social, institutional and community activities that are needed to turn an area round. These activities are undertaken cooperatively among all parties involved—residents, community groups, businesses as well as local and national authorities if applicable.

Slum upgradation’s focus apart from providing basic services to the slum dwellers also put the people at the center of this process. It creates a sense of ownership, entitlement and inward investment in the area.

DIFFERING FROM URBAN UPGRADING

While urban upgrading is about striking a balance between investing in areas that attract investment to city on a global level and in schemes that invest in the citizens of the city in order for them to reap the benefits as well. Slum upgrading on the other hand is an integrated component of investing in citizens. Residents of a city have a fundamental right to environmental health and basic living conditions, and therefore, cities have to ensure that

the same is provided to the urban poor. The reason this methodology of improving slum living condition is being considered by governments on a global is because it allows them to prevent the formation of new slums. If slums are allowed to deteriorate, then the government loses control of the population and these areas become regions of crime and disease.

Slum Upgrading in India

NATIONAL SLUM DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM (NSDP)

ADVANTAGES OF SLUM UPGRADATION

- Fostering Inclusion it addresses serious problems affecting slum residents, including illegality, exclusion, precariousness and barriers to services, credit, land, and social protection for vulnerable populations such as women and children.

- Promoting Economic Development: allows slum dwellers with their skills to be a productive part of the economy, which most of the times is denied to them.

- Addressing City Issues deals with issues like environmental degradation, imrpoving sanitation, lowering crime, and attracting investment.

- Minimal Social Cost: involves laying down amenities without uprooting existing houses and avoids disturbing livelihoods.

This 1996 program aimed at upgrading 47,124 slums throughout India. It identified a target slum in each city which it planned to develop as a “model” slum. In this program, improvements in physical amenities - such as water supply, storm water drains, community baths and laterines, wider paved lanes, sewers, streetlights are provided to the entire slum community. This program provided loans to states for upgradation projects on the basis of their urban slum population. The slum households wre provided loans to make improvements to their housing whil the government focused on providing amenities.

However, as is the case with most policies in India, administrative restraints only allowed part of the funds to be made available for the projects under this program. Even though this program reached a large number of people, it lacked proper monitoring and supervision resulting in extensive time delays and misused funds.

IN-SITU SLUM REDEVELOPMENT USING LAND AS A RESOURCE (HFA PROGRAM, 2015)

The Housing for All scheme was approved in 2015 with the goal to provide housing to every India household by 2022 (which hasn’t yet been achieved). This scheme plans to include 300 major cities in India in its first two phases,

and extend it to the remaining cities. This program incorporates the in-situ rehabilitation (on-site upgradation) through which the government has devised a strategy to incentivize private developers to use land as a resource (known as ISSR). Under this scheme, slums which are tenable - able to be maintained and not at high risk - will be re-developed/upgraded using the in-situ strategy. In order to make this program successful, the government has decided to incorporate private sector partnerships.

The main features of this upgradation includes:

- It will use land as a resource to involve private developers.

- Public-private partnerships to create affordable housing.

- Affordable housing through credit linked interest subsidy.

- Beneficiary-led individual house construction or enhancement.

The way this program works is that state or urban local bodies provide slum areas with additional floor space index that will result in verticalization of the sprawl. The freed up land area from the verticalization can be used by private developers for commercial resale. This allows private builders to construct houses for eligible slum dwellers free of cost. In areas where such cross-subsidization is not possible, the government will share the financial burden through viability gap

funding (60-75%).

The shift in India as well as other parts of the world from slum clerance redevelopment, to ex-situ, and then insitu has shown a promising future for the slum areas in developing countries. It has ensured better quality housing, faster construction, and enhanced beneficiary input.

The success of this program can be particularly seen in the city of Mumbai, india. The strategy of insitu development in Mumbai has been running for more than 20 years and created a large market for slum rehabilitation projects in the city. The entire program in Mumbai is run by private developers with no form of payment from either the end user or government. With Mumbai, having one of the largest slums in the world, the success and strategies implemented in this city are now being incorporated at a slow pace in other cities.

form the core composition in the Sangam Vihar area, which is the prposed area of focus for my design intervention.

JHUGGI-JHOMPRI CLUSTERS

These are the slum clusters or squatter settlements which have formed on public and private land all over the city to accommadate migrants and also the main focus of this study. In cities like Mumbai & Kolkata, slum have developed near large factories and mills. However, in the case of Delhi they are scattered all over the city, usually along railway tarcks and roads, river banks, parks, public places, and vacant lands. As a result traditional insitu rehabilitation very expensive until the recent Housing for All scheme was released in 2015. The slum shelters are made of mud wall waith thatched roof, with brick and mud wall with abestos roof, and with brick wall and tin roof.

Existing Informal Settlements in Delhi

To understand and effectively propose architectural and redevelopment proposals in Delhi, it is important to understand the types of informal settlements that exist in the urban fabric of the city and which typologies

Jhuggi Jhompri clusters around railway lines

RESETTLEMENT COLONIES

These colonies have been developed on the outskirts of the city to resettle around 2,16,000 squatter families, with each household given 18 sq meters of land at a rate of $106 (5,000 INR). These colonies suffer from issues like lack of electricity, waste disposal, schools, hospital, roads etc. Most of the families also don’t have access to individual water connections or toilet facilites.

The distance of some of these colonies from the work place of the squatters have made this an unsuccessful project, and has forced them to move to slums that are located within the city.

UNAUTHORISED COLONIES & HARIJAN BASTIS

The unauthorised colonies are those residential pockets that have come up on private land in an unplanned manner in violation of the master plan and zonal plan regulations. The ‘harijan bastis’ are those unauthorised colonies that are inhabited by the low caste families. The buildings in these colonies are concrete structures which have been constructed without approved plans. road networks, drainage and sewage system, parks, playgrounds, community centers and other common facilities have not been developed in such colonies.

LEGALLY NOTIFIED SLUM AREAS

The notified slums are those, which have been declared/notified as slum areas under section 3 of the Slum Areas (Improvement and Clearances) Act, 1956. Under this Act those areas of the city where buildings are unfit for human habitation by reason of dilapidation, over-crowding, faulty arrangement and design or where due to faulty arrangements of streets, lack of ventilation, light sanitation facilities, or any combination of these factors the living environment are detrimental to safety, health or morals. These areas are found heavly in the walled city of Shahjahanabad (present day Old Delhi).

URBAN VILLAGES

It is estimated that about 70,000 people live on the pavements in busy market places in the city where they work as wage earners.They can not afford to commute from a distance since their livelihood depends on the places where they have to work. These people mostly work as porters, shoeshine boys, rag pickers, and other unstable wage work. They can also be compared to the large homeless population in many US cities.

There are about 106 villages on the outskirts of Delhi, which have become urbanized in a haphazard and unplanned manner. These are not notified urban areas and are outside the jurisdiction of Municipal Corporation. Therefore these areas are devoid of the facilities of assured potable water, surface drainage system and sanitation arrangement. The real estate speculators have acquired large tract of land in these villages, displacing their original habitants, who have either migrated to the city or switched over to the tertiary occupations, while new settlers have started constructions in an unplanned manner, making the future planning of these prospective urban areas even more difficult.

Jhuggi Jhompri narrow unpaved streets

Jhuggi Jhompri housing with bricks & tin roofs

PAVEMENT DWELLERS

Resettlements colonies in Savda Ghevra, Delhi outskirts Safeda (top) & Deoli (bottom) harijan bastis, Delhi

Commercial and housing zones in the city of Old Delhi Pavement Dwellers scattered around the city

. precedents uncovering Kathputli, Yerwada & Sanjaynagar slum redevelopments

This colony was formed in the late 1950s. The colony was established on an unoccupied 5.22 hectare former bus depot in the Shadipur neighborhood just west of Delhi. Most kathputli residents are gypsy artisans from Rajasthan whole settled here while contunuing to practice their art.

At the time when the in-situ project was undertaken, the population of Kathputli colony continued to decline as people moved to the transit camp. As of february 2017, 40% of the houses had been demolished as part of the re-development plan by the Raheja developers and the DDA.

Train tracks form the western boundary of the site. Patel road, which forms the boundary to the north, is elevated to along the length of the site to cross over the tain tacks. Many of the city’s metro lines pass over the colony in the form of elevated bridges. The colony forms the southern tip of a group of informal developments that cuts through the western Delhi following the train tracks.

THE DDA & RAHEJA DEVELOPERS PLAN

The request for proposal for this redevelopment project was initiated in 2008, and in 2009, the project was awarded to Raheja developers. This in-situ project was carried out by a private-public partnership between the private developer and the DDA (Delhi Development Authority). The developer in this case had full control of the rehabiltion process which allowed them to propose market-oriented, private sector housing on a portion of the site in exchange for constructing 2800

for

of

Colony.

Along Patel road (which forms the north boundary of the colony), there would be a private sector tower called Raheja Phoenix with a height of 190m with 54 floors. The tower would also have a commercial complex. During the redevelopment, temporary accommodations for residents was provided in the form of a transit camp constructed by the developer, located a kilometer away from the colony. In the period between 2014 and 2016, 500 out of the 2800 households moved to the transit camp.

THE PROPOSAL

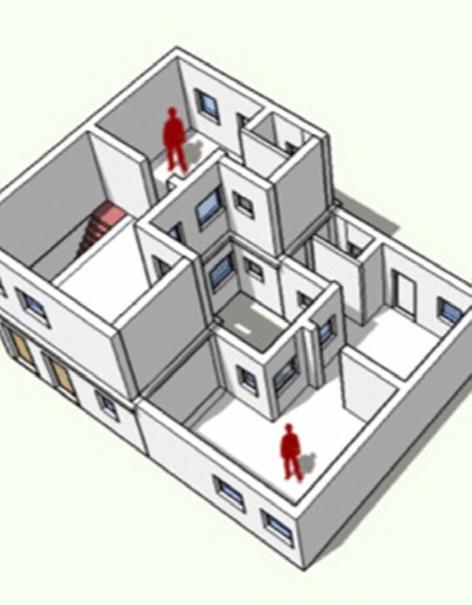

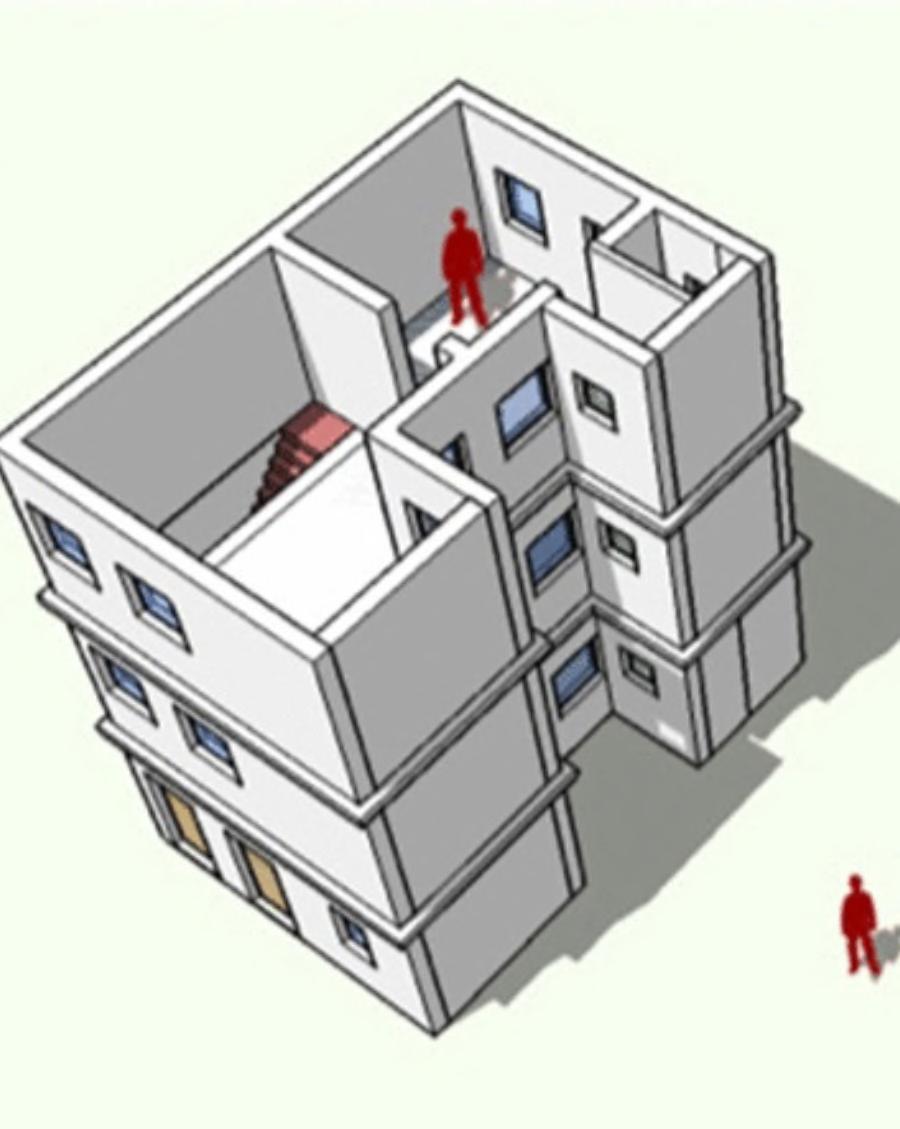

The total site area comprises of 5.2 hectares (559,723 sq. ft). out of this, 1.9 hectares (204,514 sq. ft) was given to private sector developemnt with the remaining 3.35 hectares (360,591 sq. ft) designated to replacement housing units and a school.

Features of the proposal:

• The resplacement housing consists of a network of connected 15-storey apartment slabs with a total of 2800 units.

• Each unit measures approximately 330 sq. ft. In terms of all units combined together, this accounts for 1,115,141.12 sq. ft. Adding the circulation, this square footage changes to 1,345,488.8 sq. ft.

THE KATHPUTLI COLONY : In-situ EWS Housing

Kathputli Colony Site Analysis Plan Present Day Kathputli Colony

The private Sector ower proposal, Raheja Phoenix, that will be built along Patel Road by the developer alongside the 2800 replacements units for the colony.

replacement units

the people

Katputli

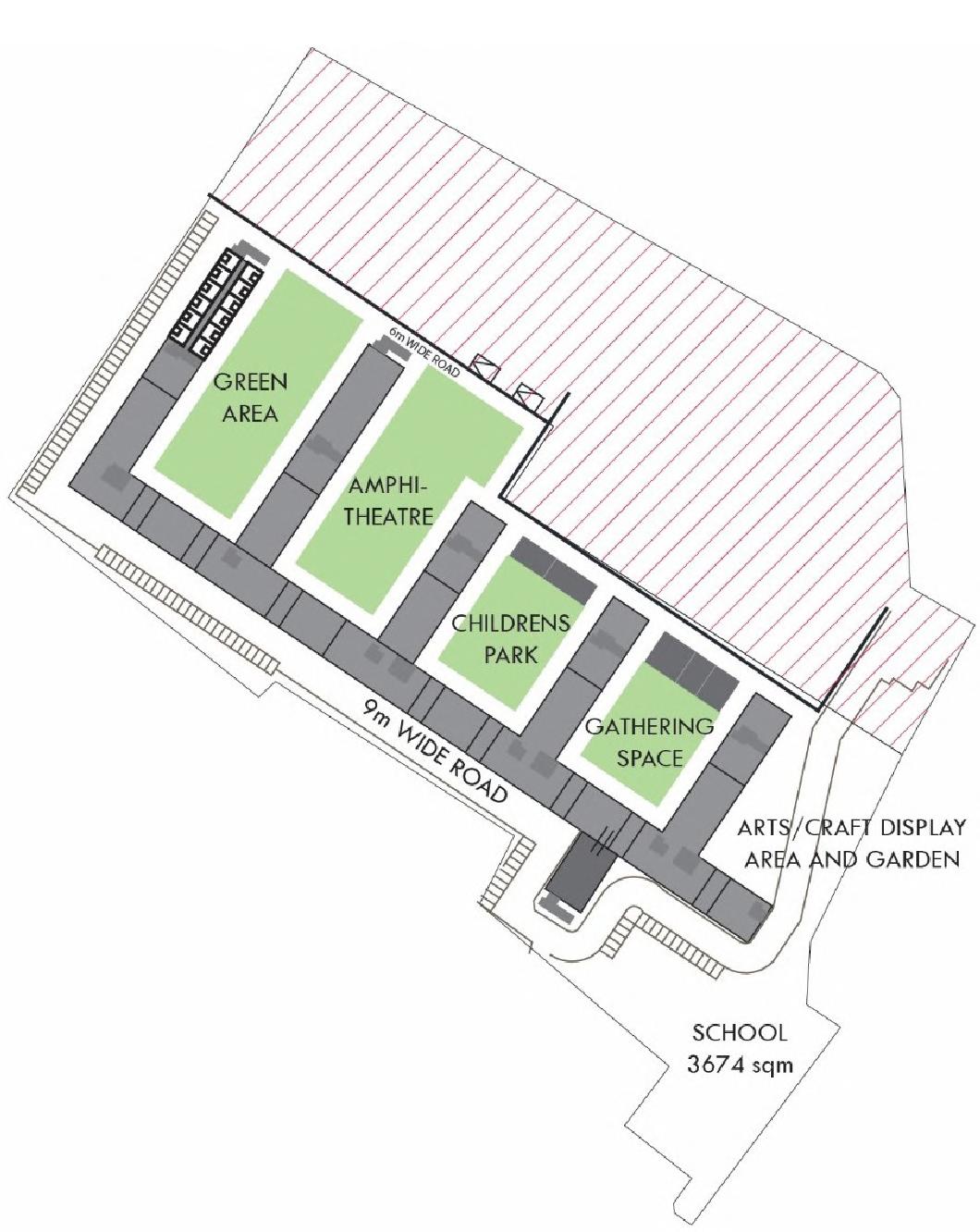

Significant amount of consideration was also given to the open spaces between the buildings. The total area occupied by open spaces is approximately 103,333 sq. ft.

The programmatic configuration of open spaces include

• Two large (98.42 ft x 295.27 ft) spaces between tower blocks: two smaller spaces between tower blocks (98.42 ft x 164.04 ft and 98.42 ft x 131.23 ft); one triangular space (16,145 sq. ft).

• Since the building sits on ‘piloti’ the space under the building are available for parking, and art and craft display area. 14 cores connect spaces at grade ith upper levels.

Other spaces and features include:

• School 39,546 sq.ft

• Community garden plots

• Two outbuildings containing health center, police post, multi-purpose hall, “basti vikas” (shelter board office), and religious space.

• Roads

- 29.5 feet setback around the perimeter of the community (used as a road) on the east, west and south side.

- 19.6 ft wide road along north side of site (separating Kathputli community from Raheja development.

- 19.6 ft wide fire lanes around all buildings.

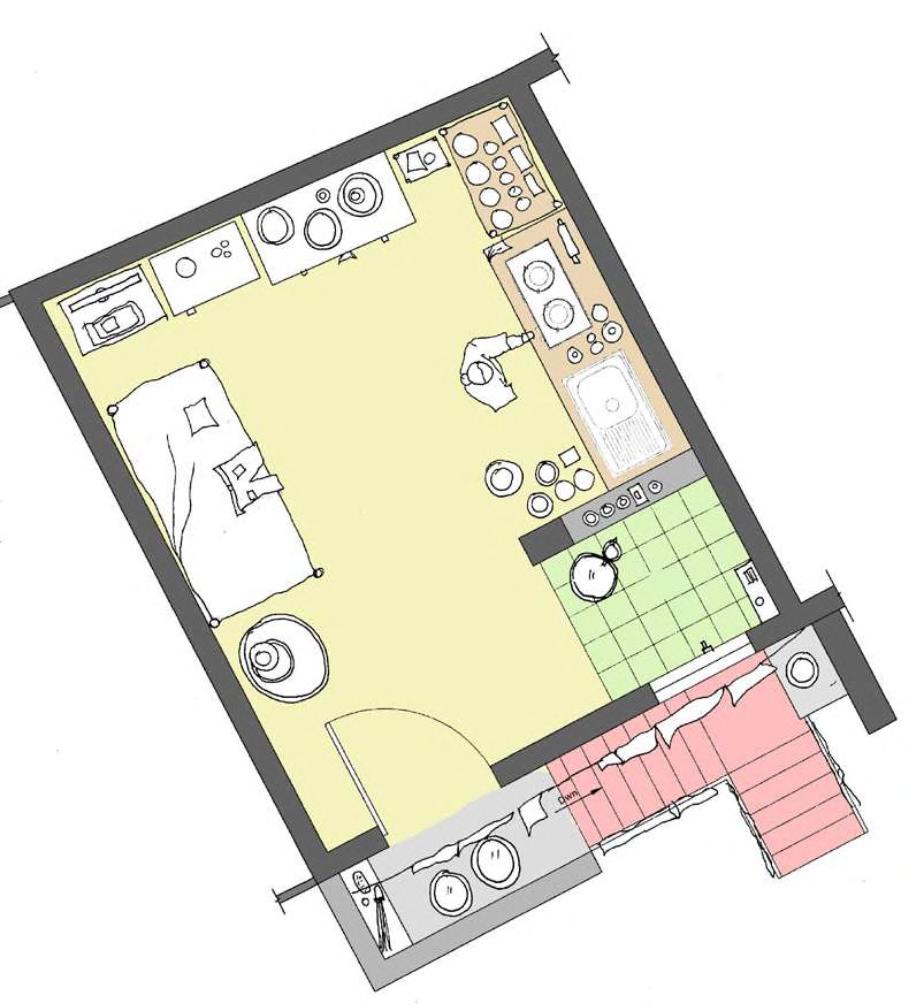

Proposed Unit Layout

Proposal for the Re-Housing of Kathputli

ISSUES AND CHALLENGES : Why the project did not resonate with the community ?

Kathputli Colony was delhi’s most colorful and vibrant colonies with people performing all kinds of puppetry and entertainment shows. It is a symbol of India’s tradition and culture and reminds one of the entertainment industry of the past.

The Kathputli redevelopment project, even though meant for the welfare of the community that had been residing for years in miserable conditions, did not resonate with the dwellers because it seems like a project that focused on urban transformation while destroying the culture and essence of tradition of the people it is meant for. The main concern raised by the residents was that the proposal “did not take into consideration the needs of the residents of the area, who have specific requirements in view of the nature of the vocations.” The program did have a long list of art viewing spaces and outdoor spaces, but those were more genric in nature and could be found anywhere.

The developer of the project (Raheja) seemed to tackle the problem in Kathputli Colony with a lack of sensitivity to people’s culture and traditions. Assuming that people in the past were forced into their particular lifestyle due to lack of resources, and trying to enforce a genric design style of high-rise housing took away from the aspect of community and celebration. The project definitely had to tackle a lot of challenges, the major one being, the “relocation” of dwellers to and from the colony during the redevelopment

process. However, what made the project even more alien to the dwellers is the fact that they were given a readymade plan, and they were expected to adapt and change their lives upon the completion of the apartments, which itself carried on for 14 years before finally being completed.

KEY DRAWBACKS OF THE PROJECT

The first major drawback of the project is in terms of the trade-offs between low-rise and high rise units. While the high-rise approach is an effective way to house large numbers of people on a small footprint, it definitely disrupts the cohesion of the community. Lots of families of Kathputli colony have children, and high-rise buildings are not well suited to them as it isolates the children from outdoor space, and one cannot monitor the log corridors that are part of these newly built apartments. The system of elevators requires constant maintenance, and maintenance in these high-rise EWS units are not always guaranteed. This aspect of high rise buildings aslo affects the lifestyle of women who in general are adapted to cooking food outdoors.

The second major drawback is the failure you to incorporate the true essence of in-situ rehabilitation. This process emphasizes the need to incorporate user input as well as participation in the design and construction process, something which this project does not really do and creates forced changes.

YERWADA SLUMS : In-situ upgradation

OVERVIEW