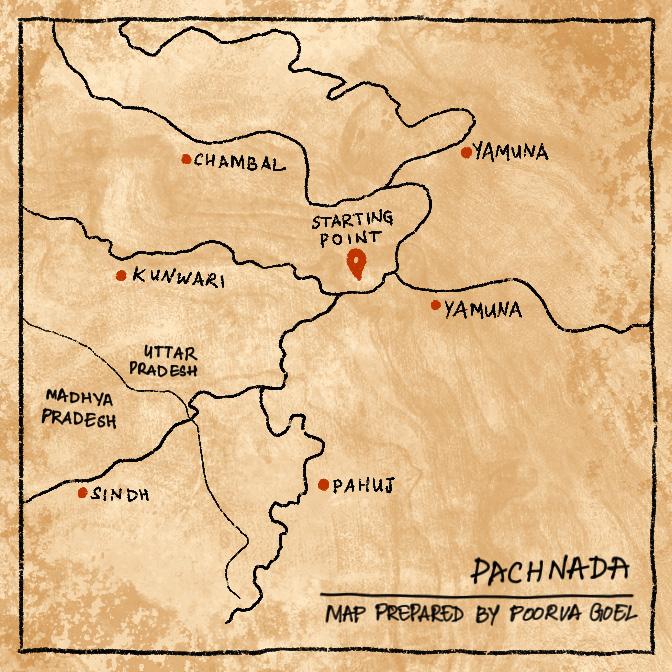

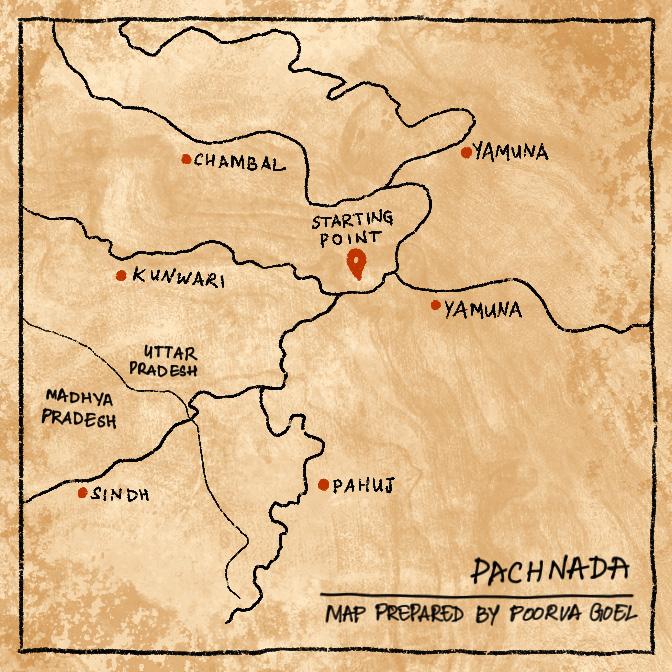

Rising in the Malwa Plateau, River Sindh flows through Madhya Pradesh and joins River Yamuna along with Rivers Kunwari, Pahuj and Chambal at Pachnada in Uttar Pradesh.

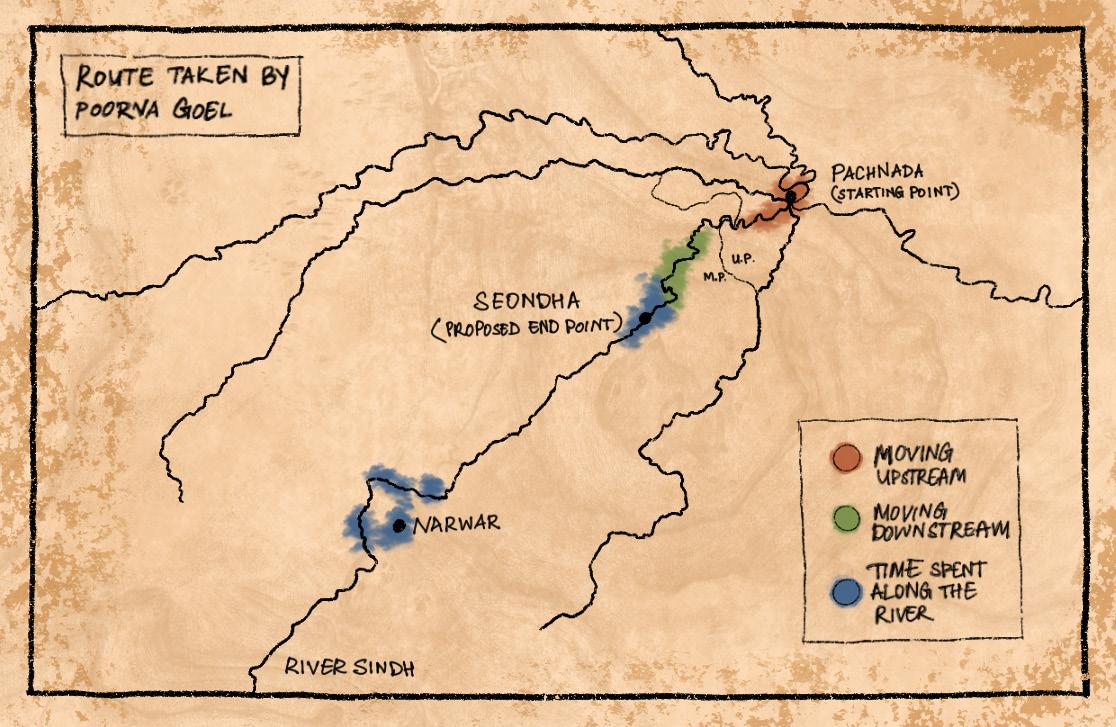

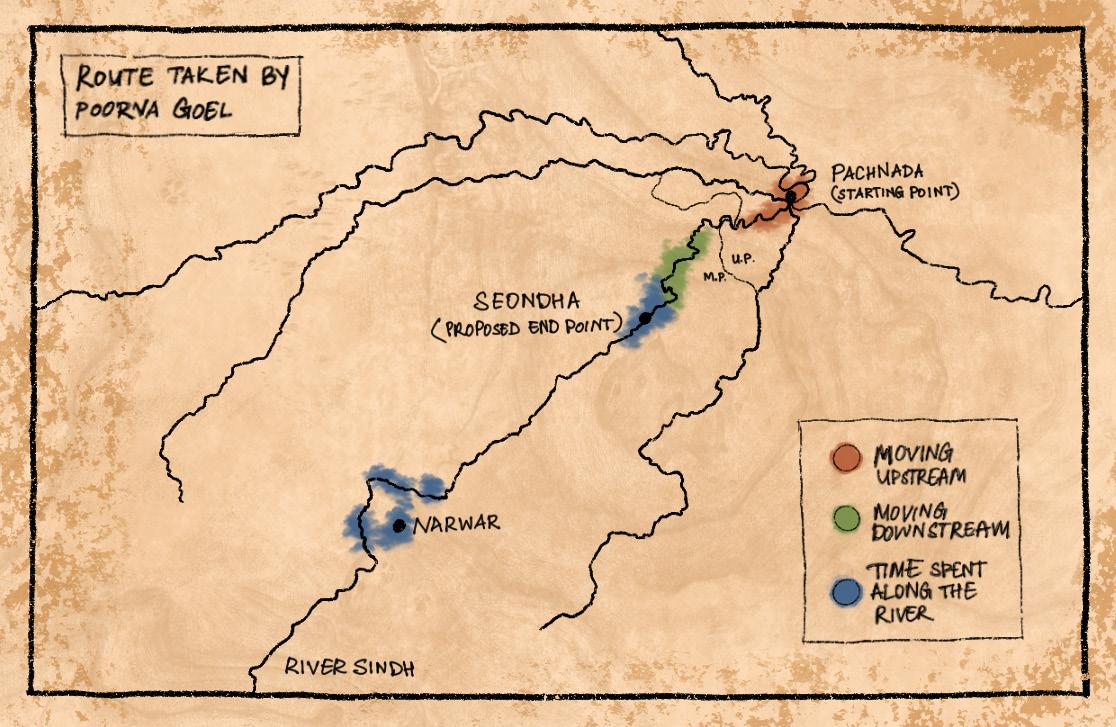

In late February 2022, Poorva Goel and her teammate, two people volunteering for the ‘Moving Upsream’ project by Veditum, had set out to walk upstream from the Sindh’s mouth at Pachnada to Seondha, aiming to cover about 120km in 15 days. They marked the start and end points on their Survey of India map after which everything was an act of improvisation.

The lack of documentation from the region made it difficult to anticipate what lay ahead of them. They walked into the unknown, planning every hour as it came. They had to reroute a few times due to the tensions on the ground. After spending the first couple of days in the Pachnada region along River Yamuna and River Chambal, they walked upstream River Sindh from Pachnada to Hukumpura, then downstream from Seondha to Birona, and finally, the team split up and spent time at different stretches of the river.

Using the river as their compass, they paced themselves through the overwhelming sources of stimuli. They had to strike a balance between being present and recording their observations through quick sketches, written notes and photographs. Often subtle visual cues and patterns that emerged became clearer as they spent more time along the river.

Conversations with people helped set the context and fill the gaps. Time seemed to have slowed down by the river. During the day, they went through agricultural fields, scrub forests, sand bars, ravines and hairpin bends. They aimed at reaching a village before nightfall for food and shelter.

PACHNADA: WHERE THE FIVE RIVERS MEET

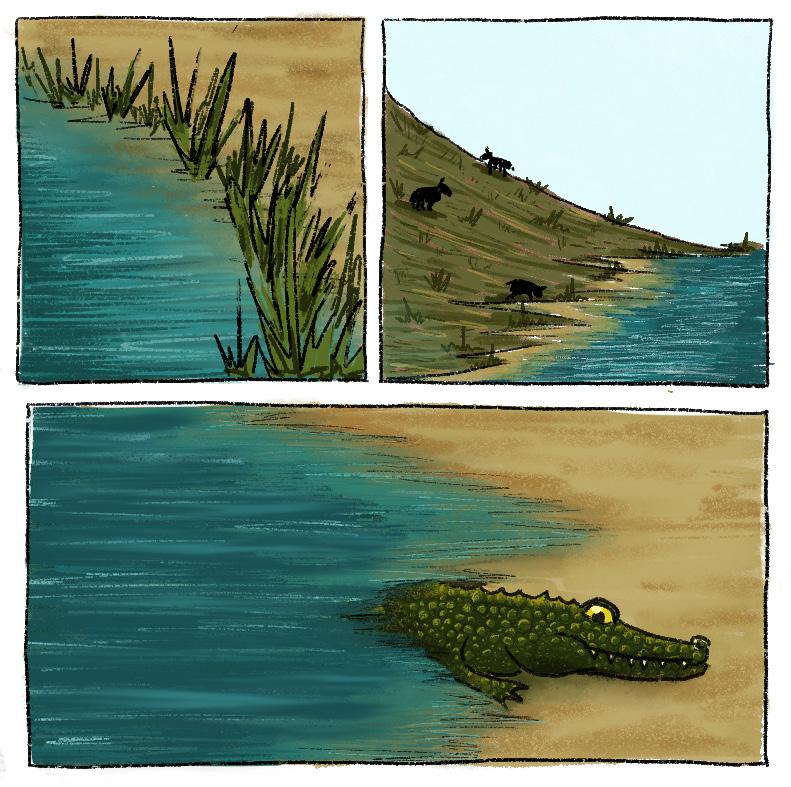

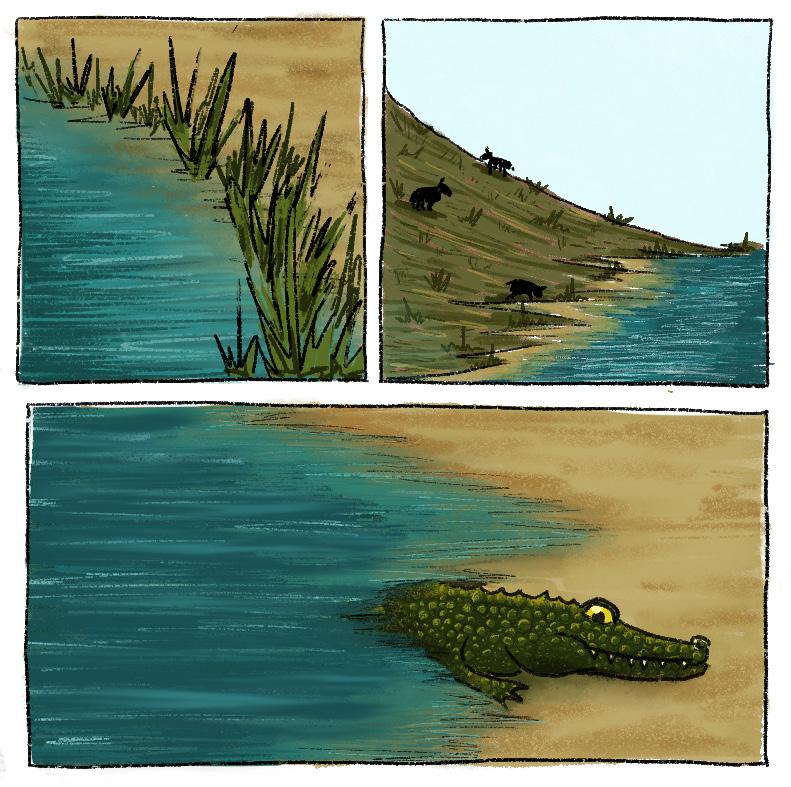

At Pachnada, the rare spectacle of five rivers converging exceeded all expectations. The floodplains were lush with mustard and wheat fields, and the scrub slopes were dotted with grazing cattle.

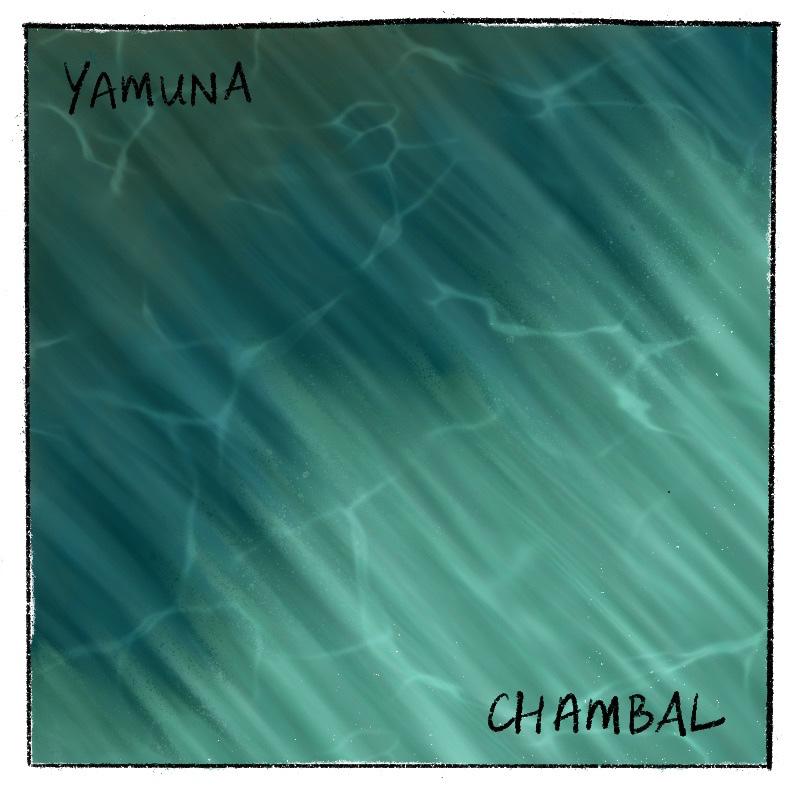

Over time, the gentle currents of the Chambal and Yamuna rivers have meandered and unloaded their sediment on the floodplains, creating massive sand deposits over 200 meters wide, locally referred to as ‘morham’. This is where the Crocodiles come out to sunbathe. They camouflage so seamlessly with the morham that one might miss them at first!

The soft sound of the flowing rivers is subdued by birds chattering, darting and splashing in the water. The loudest is the strong wind that blows over the morham, unhindered by the scant vegetation on it. The lack of vegetation does not mean that these are ‘wastelands’. Besides being a crucial habitat for wildlife, they are also utilised for riverbed farming by the communities along the river.

In their first couple of nights, the former Pachnada Yamuna Nadi Mitra Mandali (YNMM) members generously hosted Poorva and her teammate at their office. Mr Indrabhan Singh Parihar, a former president of the committee, was well-acquainted with the region from years of experience in surveying the Yamuna-Pachnada stretch as part of their river restoration program. Indrabhan Ji describes the Yamuna as parivartansheel (in flux) – constantly changing and shaping all else around it. He explained how the river replenishes the floodplains every year. Like their ancestors, they reap the benefits of seasonal flooding in the form of bountiful harvests.

However, in August 2021, the region witnessed unusually devastating floods that washed away homes, cattle, agricultural fields, and community forests. Speculations suggest that these unprecedented floods were caused by a combination of climate change effects and mismanagement of the dams on the Sindh. The floods had also destroyed important bridges, making transport and connectivity very difficult. The area had not witnessed a flood this extreme at least in the last 40 years. With sparse compensation for their loss and the lack of media coverage, people feel a sense of neglect from both government and society.

CO-SCULPTORS OF THE LANDSCAPE: THE RIVERS AND THEIR PEOPLE

The river cuts through the central highlands leaving a texture like a knife through butter. In Lalpura village, a passage through the alluvial ravines leads to the Chambal’s bank. The natural earthy structures reminded Poorva of old fort walls.

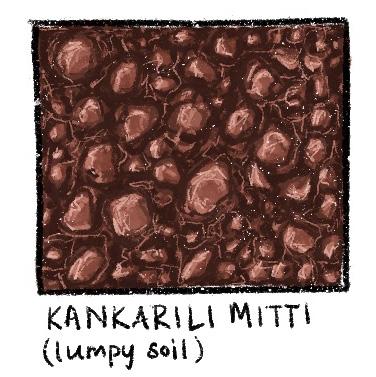

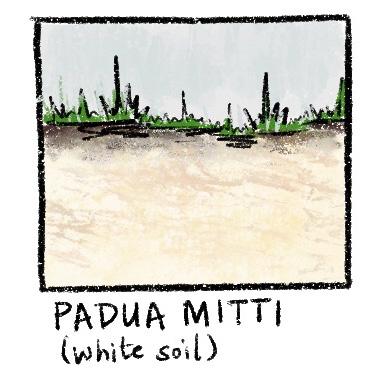

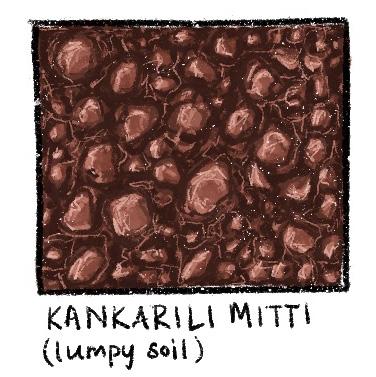

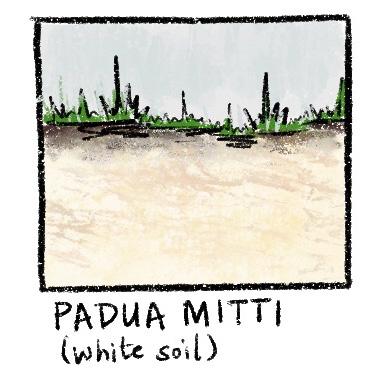

The landscape was different shades of ochre. Indrajitji, another volunteer at the YNMM, pointed out the varieties of soil and their respective uses in traditional mud houses; padua mitti for putai (coating walls), peeli mitti for lipai (coating floors) and kankarili mitti, that is not used for much.

According to local belief, the infamous game of dice between the Kauravas and the Pandavas had taken place on Chambal’s banks. When Draupadi found out that she had been gambled away by her husbands, she cursed the river for being a silent bystander. Consequently, the Chambal river has remained largely untouched by human activities. It is ironic that an ‘unholy’ or ‘cursed’ river becomes polluted upon contact with the ‘holy’ river, Yamuna.

Draupadi’s curse might have saved the Chambal’s water from pollution but not from extractive and destructive developmental activities. Sand mining and the four dams that punctuate its flow pose a major threat to the river’s health. This along with poaching has negatively impacted the population of the soos, the Gangetic River Dolphin and gharials, fish-eating crocodiles. Indrajit Ji has witnessed the river shrink significantly in width and depth in his lifetime alone.

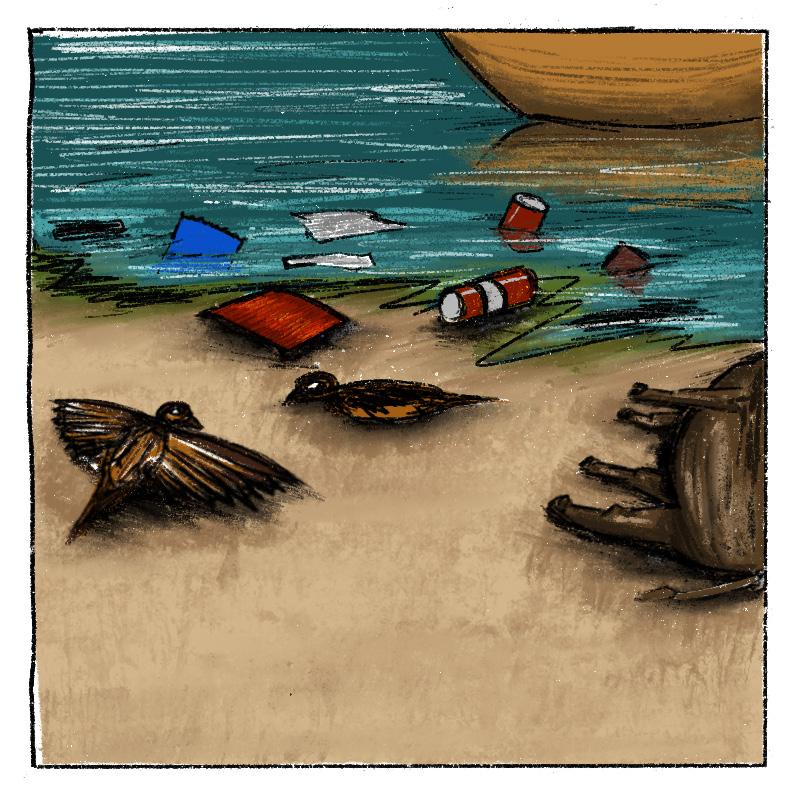

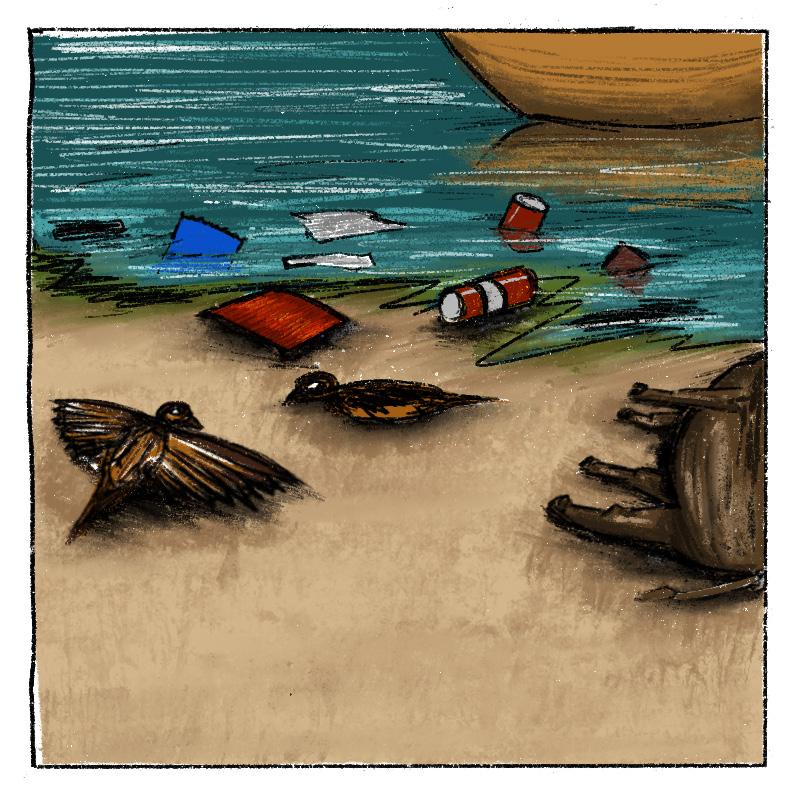

At the Yamuna-Sindh confluence, River Yamuna’s bank is lined with trash, algae, and carcasses of cattle and several individuals of a migratory bird species that Poorva’s teammate identified as the Egyptian Vulture. While the cattles die from a common sickness, the reason behind the death of the Egyptian Vultures is unclear. The locals claim that they fall prey to a poison that the poachers use to catch other birds for meat.

Vilayati Babool (Foreign Babool), has rapidly taken over much of the ravines. The name vilayati or foreign suggests that it is not a native species. This invasive species however has become an integral part of life there as it is commonly used by the locals for fuelwood and fences.

Navigating through the babool forest is like doing an obstacle course made of barbed wire. One prick from its thorns could leave one sore and scratching for days. This invasive species has negatively impacted biodiversity by hindering the movement of larger mammals.

GANGS, GUNS AND GAUMATA

Large unsupervised herds of cows straying across the morham or being chased out of a farm by a distressed farmer is a common sight. Farmers say that the ban on the sale of cows for slaughter has led to an unprecedented rise in their numbers. The holy cow that they have worshipped for generations has become the bane of their existence. Not only does this cow-farmer conflict affect the mental and economic well-being of farmers but subjects old cows to an afterlife of abandonment and neglect post their productive years.

Cattle rearers now prefer rearing buffalos and goats over cows as the former are more economically viable since the ban. Poorva and her teammate heard iterations of similar stories from several farmers across the floodplains. The farms are sealed off with Jhakkars (farm fences) made of thorny branches from vilayati babool and Ber trees (Indian Jujube). This is not enough by itself to prevent conflict between animals and farmers. The fields need round-theclock vigilance. At night, the machans, temporary sheds, is manned by a solo daily-wage worker, typically from a scheduled caste background, to guard a few acres of farmland owned by an upper caste landowner.

Back on their planned walking route, they were stuck at the Kunwari-Sindh confluence for there were no means to cross the Kunwari. The mallah (a boatman from the Mallah community) had already returned home after cutting Berseem (Eyptian clover) as fodder for his buffalos and he was not going to return for his evening fishing until much later. They sat there waiting for a few hours for the mallah to row past them. When it was almost sunset, the people who accompanied them while they waited, invited them to spend the night in their village, Bithauli. Everyone around was a little apprehensive about their journey ahead. Stories of a gang of 40 aatankis or dakus (dacoits) had begun resurfacing in the region they were traversing. Their origin was unclear- some had heard that it was men and women from families of rival gangs while others deduced that it had something to do with the preceding UP elections.

Thanks to social media, rumours surrounding dacoits-on-the-run spread fast. They met at least one person in every village who knew someone who had heard that somebody had been recently shot and dragged by dacoits in broad daylight. Their conspicuous appearance in the bihad (ravines) set off alarm bells among some suspecting inhabitants. They were stopped by villagers and eventually reported to the police for further investigation thrice within the first four days of their walk. Their hosts in Bithauli village, who had only known them for a few hours, went out of their way to accompany them to the police station and took complete responsibility for them. Poorva and her teammate were extremely grateful, but were also guilt-ridden for the undue anxiety they caused the family. Getting stuck there allowed them to develop a close bond with their hosts

No sooner did the police verify them as non-criminals than the people from the village suspected them to be eloping lovers, a trafficked woman and her tormentor and so on. It was apparent that their presence did not make sense there.

However, some of the younger people in the village were apologetic on behalf of their elders. They explained that this was a regressive region and most of them don’t understand what they are doing because of almost the non-existence of media and information.

After considering the advice of their host family to return home and weighing their options, they continued walking the next day. The news of their “capture” had reached the villages further upstream before they did! The people, as anyone would expect, were inquisitive about them and concerned about their own safety on account of strangers walking through their village. Once again, they found themselves in the midst of angry and suspecting locals.

Even with a plan as broad as ‘moving upstream’, they had to adapt and reroute in the face of roadblocks. They instead began walking downstream from Seondha, Madhya Pradesh, which had been earlier decided as the endpoint of their walk. They hoped that Madhya Pradesh had not yet caught up to the stories about the notorious gangs.

Walking downstream, once again they were stopped near Birona village, this time by a group of locals armed with two loaded rifles and around ten sticks and axes. The locals filmed as they presented id cards and emptied the contents of their bags at their demand. Confronted by these instances of fear and apprehension yet again, they decided to approach the walk differently. their journey had turned out to be far more adrenaline-pumping, spine-chilling and hair-raising than one could have anticipated. From what they knew, the other Moving Upstream fellows that had walked along the different stretches of the Sindh river shortly before them, had not experienced anything as extreme. They may have happened to be there at the wrong time. Poorva stated that she felt surprisingly calm negotiating with the suspicious villagers and deduced that it was a survival instinct.

Escaping the crosshairs of the locals, quite literally, they were slowly catching on to the mental turmoil of it all. Fortunately, they were able to carry on with support from Veditum and a synergy of strangers they met and befriended along the river.

MOVING DOWNSTREAM

On their foot traverse down from Seondha town, Madhya Pradesh, they were warned to expect sand mining on the river. They saw people working with shovels in the sand from a distance and immediately inferred that they were sand miners. As they got closer, they saw that a family was tending to the saplings of gourds, cucumbers, pumpkin, chillies and coriander. This practice of riverbed farming was locally known as kachuari or kachuaee.

Between Seondha and Indurkhi, the river forms massive hairpin bends. The heavy sand deposits in this stretch act as magnets for heaps of sand mining activity. They employ people and heavy machinery to extract, load and displace sand and stone from the riverbed.

In some places, the river no longer appears like a flowing channel but instead, puddles of water interspersed among sand ramps and mounds. This disturbance in the river’s flow is visible even from satellite imagery. Workers and their machines came to a standstill as soon as they noticed strangers walking toward them from a distance. Their fixed, hostile gazes followed them till they were no longer in sight. Climbing up and sliding down sand mounds and trenches about 12ft high, they had loaded and displaced a good amount of sand in their shoes.

Trucks pregnant with river sand frequently passed through the big small towns; leaving one wondering how much of it is legal. Members of a local NGO in Bhind, explained to them the nexus of different stakeholders, and the extent and impacts of illegal sand mining on the Sindh. They consider unsustainable sand mining to be among the greatest threats to the Sindh river and its human and non-human ecosystems.

Some believe sand mining to be just another source of livelihood for the locals. However, not only does it exploit the river but also those that are hired for lifting sand manually from the riverbed.

A local boatsman in Seondha says - “I don’t want to do it (sand mining). The tractor owners employ local people to mine the sand. They load tractors manually at night. It’s done illegally. I don’t do it because it involves a lot of violence. Sometimes they don’t pay you on time and sometimes nothing at all. The tractor owner makes 10,000-20,000 rupees a night. We do all the work and he takes the money. You have to fight to get your share for your labour which is something I am not able to do.”

IMPROVISING: REFRAMING THE APPROACH

When rerouting and walking downstream did not work, they had to figure out a way to push on without endangering anyone. Their safest bet was to split up, base out of different small towns and spend time along the river for the remaining field days. Poorva was upset about not being able to walk the landscape as planned but she was reminded of how lucky they were to come out of it all unscathed, which helped her keep going. However, the time spent by the river was gratifying for her. She stated that it was the perfect opportunity to dive deeper into what had piqued her interest during the walk. For instance, besides the more predictable sources of livelihood such as agriculture, cattle rearing and fishing, people’s subsistence was entwined with the river in more ways than she could have conceived before this walk!

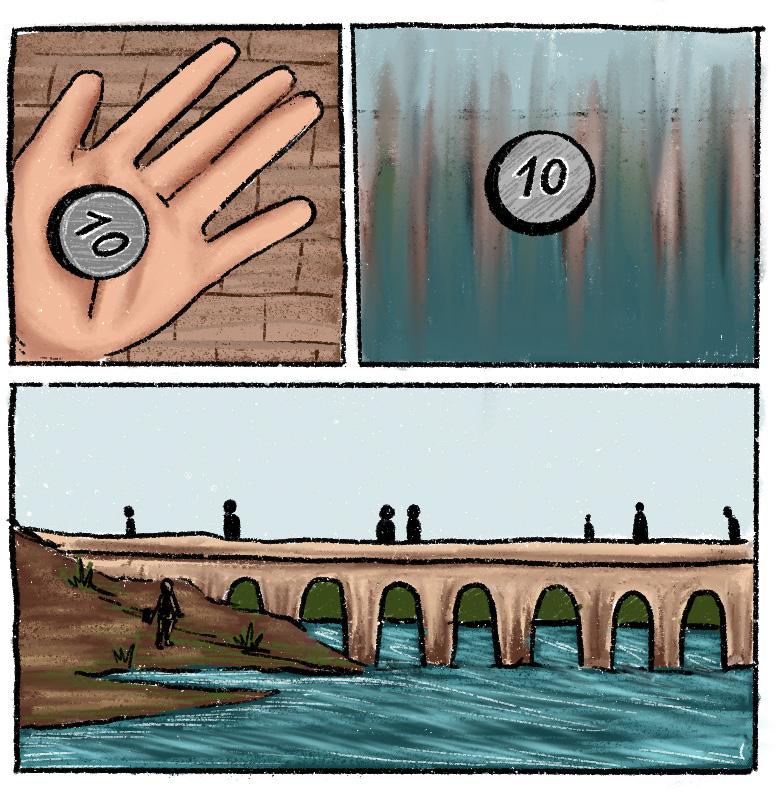

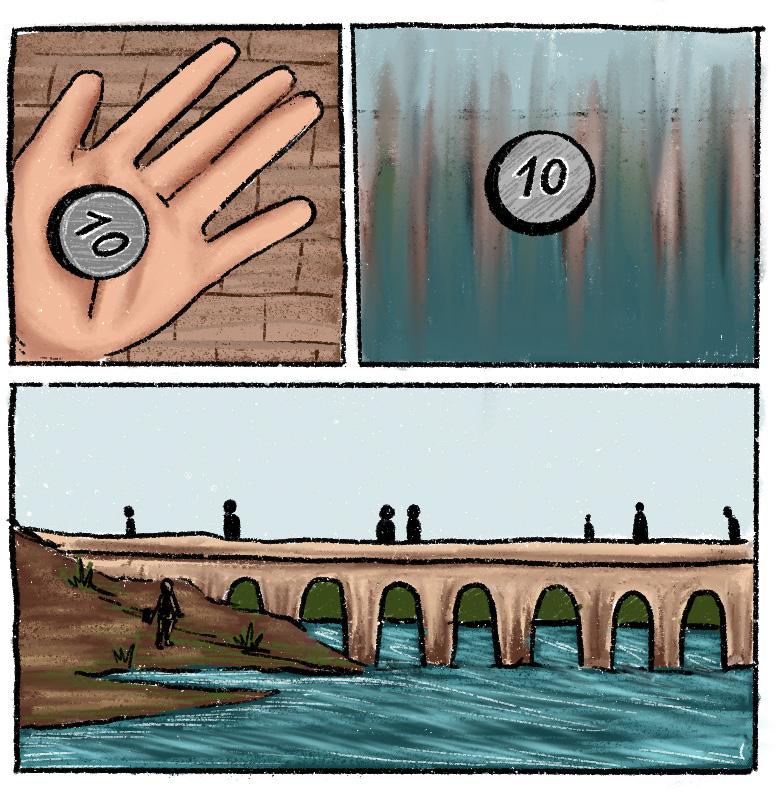

As she stood observing pilgrims and passersby at the Narwar-Magroni bridge, she heard a young boy yell from under the bridge asking to throw coins off the bridge. Raju, a seven-year-old boy, collected coins that the pilgrims left at the bridge. He did not want Poorva to know that he doesn’t go to school and instead gleans money and edible offerings by the river. “The financial situation at home and the condition of government schools have made him reluctant to attend school,” admitted an older friend of Raju’s, on his behalf.

Poorva met numerous young boys like Raju along the Sindh who dive into the river to find coins in order to support their families and she returned to their stretch of the river and spent more time with them.

Close to Pachnada, two brothers filled up a gunny bag with plastic waste washed ashore by the Yamuna river. They made a living from collecting and selling the plastic to recycling plants in Kanpur. They walked 40-50 km a day on their hunt for recyclable plastics, making her daily target of walking 10km seem trivial.

In Shivpuri District, the Sahariya Adivasi people harvest river sedges and other Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) for a living. They are especially vulnerable to changes in the river’s ecosystem. The recent floods washed away the social forest in their district, forcing them to walk an extra 10km approximately, to procure NTFPs. In addition to this, they struggle to acquire huts and ration cards that they are entitled to under central and state government schemes. Now pushed further into poverty since the flood, some have had to succumb to gleaning grains from the fields they work in. The situation is only going to worsen with floods becoming increasingly intense and frequent due to climate change.

Degradation of nature and the massive deficit in opportunities for education and employment within the region pushes people to migrate to other states in search of daily wage labour, usually as factory workers or street food hawkers.

Rajendra Manjhi, 18, from the Kevat community is a skilled diver, fisherman and boatsman. He spends time away from home, vending snacks at popular forts in Rajasthan. In conversation with Poorva, Rajendra, who wears many hats to make a living, said that he hoped to find opportunities in his village itself so that he can stay close to the river. She noticed that he always referred to the Sindh as Ganga Maiyya, mother Ganga.

WALKING WOMAN, WATCHING WOMEN

Throughout her journey, people around discouraged Poorva from carrying on the walk as they felt that it was especially unsafe for a young woman out there. Concerns about her safety and feelings of suspicion around her character were expressed very frankly. While she faced uncomfortable questions and situations as a woman researcher, she was constantly reminded of her privilege and freedom in comparison to the women she met on the walk.

Women from the upper-caste, landowning families were not allowed to step outside the house to protect their respectability, unless it was for a temple visit. Only women from Adivasi communities or lower class and caste backgrounds could be seen outside, given that it was always only for work.

The purdah for women was indispensable, be it while working in the fields or at home. At certain banks of the river that were associated with temples, young girls and older women enjoyed a marginally greater sense of physical freedom than women who are in the reproductive stages of their lives.

On the right is an illustration of a lady that Poorva took a picture of; she didn’t want to be seen around and rushed back with her bundle of fodder. She insisted on wearing her veil around her male relatives who can be seen lounging in the background.

Marriage of underage girls was not uncommon and the male child was seen as a necessary component of a complete family. All married women customarily sat on the floor whereas only the male members of the family sat on chairs and cane beds, and socialised in the baithak or common room.

FINDING CLOSURE

Poorva looked forward to finding a Ber tree everyday on her walk. She stated that the reward of its fruit was just what she needed to replenish the electrolytes that were depleted through walking on those cloudless afternoons in central India. Her eyes had grown accustomed to the soothing ochre-blue-green palette and shifting textures of the landscape, and her heart to the kindness of strangers. Despite her blistered feet and sore body, she dreaded tearing herself away from the river and returning to hunching over a desk all day.

During her last hour by the river, she waited in anticipation for a metaphor or an epiphany to strike that would encapsulate the meaning of a river but it didn’t. She thought that perhaps the fragments of that meaning lay right in front of her. The meaning is made in relation to all that interacts with the river.

The Sindh is a conduit of life- culture, local economies, biodiversity and more. The Sindh, 470km long, forms an essential part of this intricate mesh of several tributaries, rivers and distributaries that have cradled and nurtured life across the northern span of India. A better understanding of the river, its significance and why it must flow freely could keep this channel of life from disappearing out of existence.

Revisiting her notes, sketches and photographs to write her piece, she is grateful to Veditum for this intimate experience with a river. She looks forward to digging deeper into and engaging with all that she absorbed in the walking study and sharing these humbling encounters with people, places and paradigms along the lesser -known Sindh river.