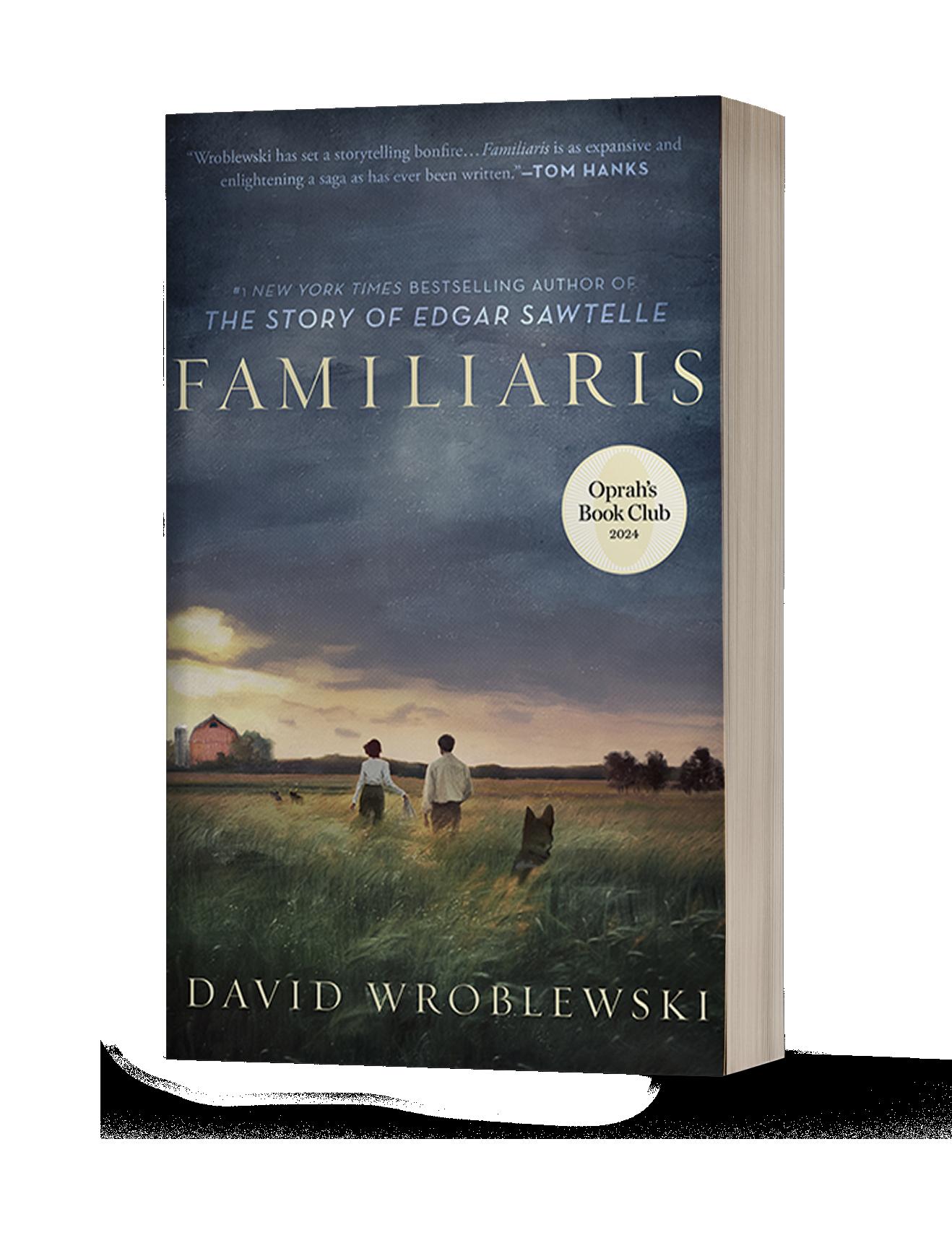

Oprah’s Book Club Pick for Summer 2024

A Kirkus Reviews Pick of 2024’s Hottest Summer Reads

A Minneapolis Star-Tribune Pick of Summer Books

A Newsday Pick of Summer Books

A Barnes & Noble Favorite Indie Book for June & July

A Milwaukee Journal Sentinel Pick of New Books for Summer Reading Finalist for 2204 Colorado Book Award

“An extraordinary journey that brilliantly interweaves history, philosophy, adventure, and mysticism to explore the meaning of love, friendship, and living your life’s true purpose.”

—Oprah Winfrey

The follow-up to the beloved #1 New York Times bestselling modern classic The Story of Edgar Sawtelle, Familiaris is the stirring origin story of the Sawtelle family and the remarkable dogs that carry the Sawtelle name.

ITIS SPRING 1919, and John Sawtelle’s imagination has gotten him into trouble… again. Now John and his newlywed wife, Mary, along with their two best friends and their three dogs, are setting off for Wisconsin’s northwoods, where they hope to make a fresh start—and, with a little luck, discover what it takes to live a life of meaning, purpose, and adventure. But the place they are headed for is far stranger and more perilous than they realize, and it will take all their ingenuity, along with a few new friends—human, animal, and otherworldly—to realize their dreams.

By turns hilarious and heartbreaking, mysterious and enchanting, Familiaris takes readers on an unforgettable journey from the halls of a small-town automobile factory, through an epic midwestern firestorm and an ambitious WWII dog-training program, and far back into mankind’s ancient past, examining the dynamics of love and friendship, the vexing nature of families, the universal desire to create something lasting and beautiful, and of course, the species-long partnership between Homo sapiens and Canis familiaris.

www.davidwroblewski.com • davidw4words

DAVID WROBLEWSKI is the author of the internationally bestselling novel The Story of Edgar Sawtelle, an Oprah’s Book Club pick, Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers selection, and winner of the Colorado Book Award, Indie Choice Best Author Discovery award, and the Midwest Bookseller Association’s Choice award. The Story of Edgar Sawtelle has been translated into over twenty-five languages. He lives in Colorado with the writer Kimberly McClintock.

FAMILIARIS is the long-awaited followup to David’s 2008 smash success literary phenomenon, The Story of Edgar Sawtelle.

• #1 NYT bestseller

• Oprah’s Book Club pick

• Winner of the Colorado Book Award

• Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers selection

• Indie Choice Best Author Discovery award winner

• Midwest Bookseller Association’s Choice

• Translated into more than 25 languages

David Wroblewski is a two-time Oprah Book Club pick!

FAMILIARIS is the profoundly human, stirring origin story of the Sawtelle family and the remarkable dogs that carry the Sawtelle name. Like The Story of Edgar Sawtelle before it, FAMILIARIS was also chosen as an Oprah’s Book Club pick. In a rare move, Oprah made it her pick not just for one month, but for the entire Summer of 2024 when the book was released in hardcover last year.

“Already having drawn comparisons to Russo, Irving, Strout, McCarthy, and Gilbert, with García Márquez added here, Wroblewski earns them all, amply rewarding readers who have been waiting impatiently for fifteen years...This colossus of a book will own you, and you will weep to be freed.”

Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“If you’ve read The Story of Edgar Sawtelle, you know that no one writes about dogs with more insight than Wroblewski...This great American novel bustles with life, and if it takes all summer to read it, who cares.”

“Spellbinding...This warm, big-hearted novel pays tribute to the joys of curiosity and creation and turns out to be surprisingly funny, even as storm clouds gather on the family’s horizon.”

“Tender, ambitious, fierce, deeply human, and of course wonderfully canine, David Wroblewski’s second novel is an American tour de force. There were moments when reading that I thought of Russo, Irving, Strout, McCarthy, Gilbert, and then just Wroblewski himself. A story spun out over generations, to be read for generations, this is a big brave book that is old fashioned in the very best sense of the word.”

—Colum McCann, National Book Award winner and author of Apeirogon and Let the Great World Spin

“By taking us back to the origins of the Sawtelle family, Wroblewski has set a storytelling bonfire as enthralling in its pages as it is illuminating of our fragile and complicated humanity. Familiaris is as expansive and enlightening a saga as has ever been written.”

—Tom Hanks, Academy Award-winning actor, bestselling author of The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece and Uncommon Type

“‘Suppose you could do one impossible thing,’ John Sawtelle says in David Wroblewski’s stunning new novel Familiaris. What would you do? Clearly, what the author would do and has done is write this impossibly wise, impossibly ambitious, impossibly beautiful book.”

—Richard Russo, Pulitzer Prize winner, author of the North Bath trilogy (Nobody’s Fool, Everybody’s Fool, and Somebody’s Fool)

“David Wroblewski is one of the few contemporary authors who can create a world that the reader doesn’t merely visit but fully inhabits. And what a world it is, rich with love and joy and heartbreak. And wonder, especially in the way human and canine form inseparable bonds. It has been a long wait for a new Wroblewski novel. The wait is worth it.”

—Ron Rash, New York Times bestselling author of Serena, In the Valley, and The Caretaker

“No writer understands the depths of dogs’ natures the way David Wroblewski does, and once again we have a vital, absorbing, and remarkable fiction fueled by this understanding. Familiaris is a rare novel, modest and epic.”

—Joan Silber, PEN/Faulkner Award-winning author of Secrets of Happiness and Improvement

“Like many readers, I adored The Story of Edgar Sawtelle, with its gripping tale of treachery and the magnificent Sawtelle dogs. Now I adore Familiaris. David Wroblewski is a wonderfully inventive writer; he knows so much--how to test a tractor, how to make a table, how to borrow money, how to see the future--but best of all he is a writer of extraordinary characters, human and canine, who will take up residence in your mind and heart. A dazzling and irresistible novel.”

—Margot Livesey, New York Times bestselling author of The Road from Belhaven and The Flight of Gemma Hardy

David’s unique perspective and wide-ranging interests, coupled with his gift for linking disparate ideas and domains in down-to-earth terms, have made him an engaging and popular teacher and public speaker.

In an interview David could discuss:

His background in computer science

• The surprising ways David’s background in computer science shaped his understanding of novel writing

• Storytelling as a technology: the craft and linguistic connections between computer programming and writing fiction

• The role of design in writing

The themes in his novels:

• The ancient bond between humans and dogs. Why is it so powerful? How did it arise?

• The power of lifelong friendships, both human and animal

• The importance of creating something lasting and beautiful in the world; the idea of pursuing “one impossible thing” as espoused by John Sawtelle in the novel

• Life considered as a series of great quests; finding one’s purpose

• The impulse to get away and start over

• The little-known story of the 1871 Peshtigo firestorm

Craft/writing and life as a creative:

• The single best piece of writing advice ever, and how it applies broadly to life

• The single worst revision strategy ever, and why it’s inescapable

• What a story is, exactly—a definition that’s useful to writers

• Where creativity is located—an answer that’s useful to writers

• How every writer has a “tractor gear,” and when to use it

• The “Three is Magic” rule

• The function of supernatural/magical elements in stories

• Sources of inspiration to help creatives endure the years-long process of making and revising original works

• How two artists living together balance couplehood with creative immersion/isolation

To arrange an interview or request a book, contact: Meg Walker, Tandem Literary meg@tandemliterary.com • 212-629-1990 x2

You had an unusual path to becoming an author. You studied computer science in college and had a successful career as a computer science researcher. At what point were you inspired to try your hand at writing a novel?

It’s impossible to pinpoint, a slippery slope. Sometime in the late 1980’s, a decade or so out of college, I started taking creative writing classes. These were, at first, mostly an academic exercise: I wanted to explore and perhaps articulate the common craft practices underlying both programming and writing. But the more I looked into it, the more I realized that if I wanted to answer my questions adequately, I would have to take on a large-scale writing project of some kind. It wasn’t until what seemed like a legitimately viable idea for a novel occurred to me, somewhere around 1995, that I felt ready to give it a try. The result, more than a decade later, was the publication of The Story of Edgar Sawtelle.

How do you feel your work in computer science informed your creative writing? Did you find many of your skills transferrable? In what ways are computer programming and novel writing alike?

The deep connections between writing and programming would take pages, if not volumes, to explore, but the short answer is: both involve crafting an artifact out of language alone—the use of language as the raw material. Both are exercises in the purest form of design. So while computer and natural languages are wildly different in kind and expressiveness, the practice of working with language itself as a material—designing, drafting, debugging, analyzing, redesigning, revising, and managing language at scale, as a work material— is surprisingly similar. I came to the daily practice of novel writing already knowing how that could and should feel from my work as a research programmer, where the goals are vague and the whole point of writing a program is not to deploy the program as a completed app for commercial use, but to understand if and how well such a program could in principle be written. Is it possible at all? How well does it scale? When does it tip over from being doable to being impossible in principle?

When and why did you commit yourself to formal training in writing? Are there particular teachers or mentors who you credit with helping you along the way to becoming a published author?

My first serious writing teacher was Robert McBrearty, the wonderful short story writer. He suggested I look into an MFA Program, and I ultimately chose the Warren Wilson MFA Program for Writers, where I studied directly under Ehud Havazelet, Joan Silber, Margot Livesey, and Richard Russo, among others.

How and when did the idea for The Story of Edgar Sawtelle come to you? How long did it take from when that idea first arose until you were a published debut novelist?

The basic idea came to me very quickly one day in 1994 or 1995, I don’t have a record of the exact date. When I say quickly, I mean over the course of maybe 90 seconds, during which I saw how an old and familiar story might mapped onto a contemporary setting I knew well: the farm where I grew up. I’m talking about the general outlines, of course, and a few obvious points of alignment. The real work of writing a novel is the slow sentence by sentence, page by page effort of proving that your initial idea is genuinely workable.

When it was published in 2008, The Story of Edgar Sawtelle was a smash success and became somewhat of a literary phenomenon—hitting #1 on the NYT list, being chosen for Oprah’s Book Club in its heyday, winning the Colorado Book Award, translated into dozens of languages, etc. What was this experience like for you? Did you ever suffer imposter syndrome?

It was surprising, no doubt about it, and exciting, but less head-turning than it might have been simply because I was already long-established in another field, had an understanding of the relative contributions of hard work and chance to such things, and also a strong sense of where I had succeeded in what I’d set out to accomplish and where I’d fallen short. That last is essential safety gear for publishing. It protects you from too thoroughly believing either praise or rejection.

As for imposter syndrome, of course I felt it. Still do, always will. It comes with job, as far as I can see, so I don’t get too worked up about it. If you’re going to try anything really new, you’re going to feel like an imposter; and in some sense, you are an imposter, though a more accurate word might be “novice,” which is nothing to be ashamed of. Novices have some unique advantages over the old hands in a field, though it might not feel that way at the time.

Was your experience writing Familiaris different from crafting your first novel? Did you feel pressure to churn out a masterpiece after the astounding success of your debut?

Yes, it was different, but how could it have been otherwise? A sample size of one is unlikely to be representative. Both books were hard to write, but for entirely different reasons. TSOES was a first novel, so I had to learn many basic lessons along the way. It was also an exercise in retelling an old story, which presents unique difficulties. Familiaris turned out to be a far more ambitious project than Edgar (and far more ambitious than I expected.) I wanted it to be as different in tone and structure as possible from Edgar.

As for pressure, the only pressure I felt came from within, and that was the desire to do justice to John and Mary’s story as I imagined it. I very purposely wrote the book slowly in order to not put myself in a position to trying to capitalize on Edgar’s success. Surely a terrible business decision, but for me, creatively essential.

Did you always know that you wanted to return to the Sawtelle story? Was the origin story presented in Familiaris in you all along, or did it come to you well after your debut was published?

John, who is Edgar’s grandfather, kept popping up while I was writing Edgar, mainly in the form of family legends that really had no place in Edgar’s story. Virtually all of those passages had to be discarded, but by the time I finished Edgar I felt I knew John very well and wanted to see what would happen if I gave his story a chance to play out on its own terms.

Sixteen years have passed between the publication of The Story of Edgar Sawtelle and Familiaris. Were you concerned about the prequel finding its readership?

Of course. As the scale of the project gradually became clear, I worried about many things, especially the daunting length of time it was going to take to do it right. But I’ve never found a way to rush the writing process that doesn’t backfire, and quickly. It just takes as long as it takes. So I did the best I could to put that worry out of my mind.

Do readers need to have read The Story of Edgar Sawtelle first to enjoy Familiaris? Or can the books stand alone and/or be enjoyed in either order?

They can be read in either order—this is why I never call Familiaris a prequel (besides the fact that “prequel” has to be one of the ugliest portmanteau terms ever coined.) The two novels are interlocking stories. Either can act as the entry point for both, though readers will have quite a different experience depending on which order they choose.

Maybe the best alternative to “prequel” was suggested to me by Danny Goldin, owner of Boswell Books in Milwaukee: TSOES and Familiaris are “companion novels”. I like that.

The publishing landscape has changed tremendously in the intervening years. Social media was in its most nascent stage when you debuted, review space has changed, new genres have taken to the fore. Did it feel like an entirely new world publishing in 2024 vs. in 2008?

The publishing industry certainly has changed, but in truth I haven’t paid much attention to publishing as an industry. I’m sure that’s not savvy, but then again I spent sixteen years writing a thousand page novel set in the Midwest with a Latin word for a title. Nobody’s about to mistake me for a savvy operator in the publishing world.

Social media holds zero interest for me. I’m too familiar with the early research showing how poor a substitute good old email is for genuine human interaction, much less the exchange of one-liners. And the whole idea of engaging social media to “build a following” feels antithetical to the work of a novelist. That’s not hyperbole. I’m often asked, “Where do all those ideas come from? All that detail?” Part of the answer is, ideas and details come to mind during those idle hours between writing sessions. If I’m worrying about my next social media post, I’m not leaving space for those volunteer ideas and images to arise.

Do you still write computer programs these days? What role do writing and programming play in your present-day creative life?

I write code all the time. I’ve written all sorts of tools and utilities to help me as a writer, because there are plenty of cases where the current (appalling) state of the art in word processing software falls short. I also take on little projects for no good reason, just for the pleasure of programming. For example, I recently decided to recreate in Python the very first program I ever “wrote” – by which I mean, typed into a terminal out of a BASIC programming tutorial, while only half-understanding what the program did. And what it did was display Robert Frost’s “Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening” one line at a time, while crudely simulating falling snow. I was enchanted back then, and still am: my introduction to the wonders of programming was instantly and intrinsically connected to the wonders of literature.

Familiaris is part love story, part adventure story, and epic in scope, covering 40 years in the life of John Sawtelle. You introduce us to work in an automobile factory, rural midwestern farm life, and dog training. Did you have to do much in the way of research?

The farm itself is drawn from memory. The Sawtelle farm is an exaggeration of the 92 acre farm where I grew up, and I can still today in my mind walk the fence line down to the creek, and up the hayfield back to the road. I can see the barn from house through the kitchen windows, and see the apple trees planted out by the road. But all the rest derives from plain old research, some online, some in libraries and archives (the Wisconsin Historical Society was a tremendous resource, as was

the Wisconsin Automotive Museum in Hartford) and the rest boots on the ground exploration. And there is an absolutely unique two-volume history of Mellen, Wisconsin entitled “Journey Into Mellen,” compiled back in the 1980’s by the town’s residents, who extracted the highlights of a century of weekly reporting in the town’s weekly newspaper. I spend I don’t know how many hours paging through it and looking at the photographs.

How does your upbringing in rural Wisconsin inform your novels? Did you base any of your characters and story on real people and actual events?

No doubt my Wisconsin upbringing permeates these novels from beginning to end. The model for the run-down farm that John and Mary rehabilitate was the run-down farm my parents bought in 1963. The northlands landscape that the Sawtelles inhabit is very much like – though not entirely identical to—the landscape of central Wisconsin, where I grew up. But all the characters are inventions.

Dogs play a central role in both of your books. How did dogs come to figure so prominently in your life and your writing?

My family has had dogs going back generations. My first memory is of our family dog. And mother’s great dream, when we moved to that central Wisconsin farm, was to raise dogs, something she eventually did for five or six years before my folks had to make the hard decision to stop, because they couldn’t afford it. Raising dogs is expensive and far from a money-making endeavor. My father made just enough to keep us above the poverty line, but not by much. Of course, as a kid I didn’t understand any of that, only that when we stopped raising dogs, an idyllic period of my childhood had been lost. Familiaris examines John at five distinct points in his life, which you call “great quests.” How did you decide on this structure for the novel?

From the beginning I thought of Familiaris as the biography of a fictional character. I wanted the story to capture the sweep of an entire life, but without the requirement to be comprehensive, as in a true biography. And it seemed to me that our lives truly are a series of quests that resist any easy label. So the shape of the novel emerged from pondering what those quests would be, in John’s case, then letting the reader witness them. Some of these quests turned out to take months, or years to play out, others only a week.

But that may be a misleadingly cool, architectural way of talking about this novel. The common thread running through all those “great quests” is a love story—John and Mary’s story, most centrally, but also a story about how love manifests between parents and children, between siblings, and between old friends.

What do you hope readers come away with after reading Familiaris?

A novel isn’t merely a story. It’s a ride the reader takes, woven through days or weeks of their life. My main hope is that readers will have a entertaining, exciting, engrossing ride, ideally one they’d like to take again. Beyond that, I also hope readers will finish Familiaris with a renewed sense of optimism. John’s goal, as a young man, was to create something lasting and beautiful–the “one impossible thing” he challenges his friends to find and make—and it would be great if readers came away with a renewed sense that they can and should do the same.