Juanita and the Whales ANOVELLA

Copyright © 2023 by Pedro Chávez

All rights reserved. Except for fair use, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission.

Pedro Chávez / Megatrato Books

(214) 316-1291

Frisco, Texas www.megatratobooks.com

Publisher’s Note: This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are a product of the author’s imagination. Locales and public names are sometimes used for atmospheric purposes.Any resemblance to actual people, living or dead, or to businesses, companies, events, institutions, or locales is completely coincidental.

ISBN: 978-1-7333826-6-3

Juanita and the Whales / Pedro Chávez

1st edition

Illustrations by Pedro Chávez“I know they’re not afraid,” said Juanita and repeated a comment she had made before. “They’re not afraid because they’re big and other fish cannot hurt them.”

Karl was intrigued by Juanita’s response and the supposed invulnerability of the whales.

“Unfortunately,” Karl said to himself, “most fish cannot harm them, but some humans can.”

Excerpt, Juanita and the Whales

CHAPTER ONE

Mid-December 1998

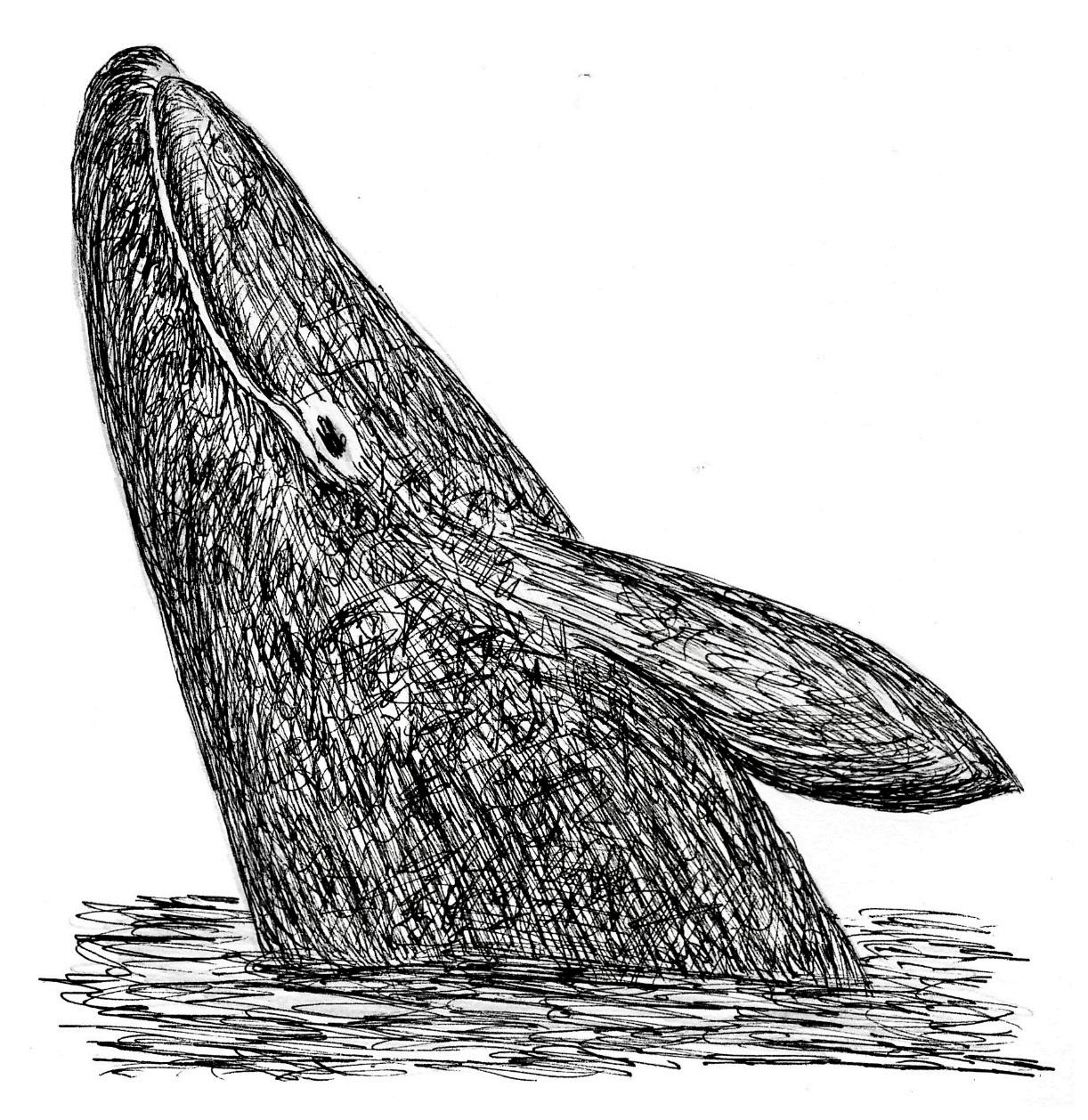

WINTER WASABOUT to arrive and so were the rest of the gray whales. Laguna San Ignacio was one of their destinations. They traveled there yearly from the waters offAlaska.Agood number of whales had already showed up, but many more would come soon and stay at that lagoon for a while. Some turned up early, as early as the beginning of December. Some stayed late, until early May.

It was the best time of the year, according to Juanita. She and her friend Luis had recently spotted a few whales from atop a strategic lookout point they both called the mound. The site was near the edge of the lagoon and somewhat close to a deep area in that body of water. Juanita was nine years old; Luis was seven. They lived a few meters from each other in a desert-like stretch called La Laguna. The area they called home was a barren and desolate collection of scanty settlements that bordered the southern end of the upper arm of the San Ignacio Lagoon, a huge salt-water bay off the Pacific Ocean and half-way down the Baja California peninsula.

“We need to hurry,” Juanita told Luis as the two walked back from school.

They were planning to again visit the mound that afternoon, hoping to see a few of the early whale arrivals.

“We won’t be able to go to the mound if we don’t hurry,” she added.

It was a long walk from school, about three kilometers long.Although they usually took their time going home, stopping for different reasons but mainly to rest, they did not do so during this time of year. They

would hurry instead so they could later have a chance to visit the whales before it got dark.

“I’m trying,” said Luis as he turned his slow walk into a fast pace.

They both had their school backpacks with them, which made it difficult to walk quickly.

“We’re almost there,” Juanita said as she stopped to take a quick breather, but also to allow Luis to catch up to her.

“Look, Gordito is coming to meet us,” said Luis, after seeing Juanita’s dog running toward them. They were now close to their respective homes. The dog’s given name was the diminutive of gordo, which means fat in Spanish, but he wasn’t really fat. He was playful, though, especially when around Luis. He was a mid-size dog of mixed breed.

“Hi Gordito,” said Luis as he petted him.

“I’ll see you in a little while,” Juanita told Luis as they parted ways, and he was about to go into his house. “After I eat and do my homework.”

Juanita was in fourth grade, Luis in second.

“Hola Juanita,” saidAlejandra as her daughter entered the house.

“Hola mommy,” Juanita replied and hugged her.

“Would you like to wait for your dad so we can all eat together?” she asked her daughter.

Alejandra was being facetious. She was just prodding her daughter in a fun way. Juanita normally ate first, right after coming home from school. The three had dinner together on weekends, though. Her father was a commercial fisherman. His name was Manuel.

“No, I’m very hungry,” she told her mother as she dropped off her backpack.

Once she washed her hands, she sat down to eat.

“We’re going to see the whales a little later,” Juanita mentioned as she ate. “After I finish my homework.”

“I hope you can get to see them,” said Alejandra. “Most whales haven’t arrived yet.”

“Some are here already,” Juanita replied. “Do you like the whales?”

“Of course I do. I wish they would stay here longer,” her mom said.

Soon after consuming her food, Juanita worked on her homework. Once done, she went outside to wait for Luis to join her. She played with her dog while she waited.

It ended up being a long wait, long enough that for a while Juanita thought about making the trip alone. It was getting late.

“I’m ready,” Luis yelled when he finally came out from his house.

“I had a lot of homework,” he said once he met up with Juanita.

“It’s late. It’s going to get dark pretty soon,” she said, adding that that they were going to have to run to the mound and run back after their visit.

“Okay, let’s go,” Luis said and took off running. Gordito was also running, closely following Luis.

What the two children called a mound was basically an old pile of trash that had become a tiny dirt hill. It was made up of mixed waste, sand, and soil that someone had at one time dumped over the rusted carcass of an abandoned truck. Over the years, the mixed heap had grown wayward plants with long roots that had attached themselves to every crevice in that trash mound, giving it an ornate and verdant look.As time passed, sand and dirt blown in from the lagoon ended up adding volume, character, and style to that trash pile.

Soon after discovering the place, the mound became a favored destination and playground for Luis and Juanita, especially during the winter months, when it provided a faraway but strategic lookout point to somewhat observe the visiting gray whales.Although it was difficult to fully discern them from that distance, Juanita claimed that she could see them clearly and that she could tell one whale from another. Based on those

supposedly observed peculiarities, she ended up giving names to several of the whales. They were all girl names. One she called Clodomira, another one Domitila. There was also a Susana and a Fabiana.

“Come on, hurry up,” Juanita yelled at Luis and Gordito as she was about to reach the mound.

Luis was at least forty meters back, barely walking now.

“Come on, run, it’s going to get dark,” Juanita shouted after coming to a stop at the bottom of the trash heap.

“Wait for me,” said Luis and took off running again.

The dog was still with him.

Juanita waited for them before climbing the small dirt hill. Once they were there, they quickly reached the top of the so-called mound.

“Domi, Domi, where are you,” Juanita yelled loudly, calling the whale she had named Domitila, but that she called Domi for short.

“Domi, Domi, come and play,” she yelled again.

“Domi, Domi ¿dónde estás?” she screamed even louder.

“I think it’s too late,” said Luis. “I think they went to sleep.”

Just as he finished making the statement, a large whale stuck its head above the water in an area far away from the shore.

“There she is, there she is!” said Juanita. “Hola, Domi.”

The whale soon disappeared but just as quickly appeared again, gliding across the lagoon and spouting a large tower of water from its back. Less than a minute later, it was joined by another large whale and two calves. Before long, they were all going underwater in tandem and coming up in the same fashion, as if making a statement or playing a game.

“That’s Domi, Luis. It’s Domi,” said Juanita. “Do you know how I can tell?”

“No, how?” asked Luis.

“By the five large white spots on the right side of her tail,” she replied. “No other whale has so many large spots.”

“I do not see the spots,” Luis replied. “You have good eyes.”

“I’m here Domi, I’m here!” Juanita shouted at the whale again.

“I’m here Domi, I’m here, too!” Luis shouted too. “Look at me.”

Both children believed that the whales could hear their far away shouts.

In his own way, the dog was also doing his own kind of yelling, barking at the whales without stop.

“It’s enough, Gordito. You lost your voice already,” Juanita admonished him.

His barking was just a muffled sound now.

“It’s getting dark. We need to go home,” she said to Luis.

He agreed. Right after waving goodbye to the whales, they began their descent from the scrap hill. They both had to get back to their respective homes soon, or they would get in trouble.

Most children that lived near the lagoon usually stayed indoors after the sun went down. Unless the moon was out and the night sky was clear, it was very dark outside. There was no public lighting. Except for a few homes that had power generators, the rest were devoid of electricity. The area was safe, though. Neighbors knew each other and looked after each other. But there was another reason for not allowing the children to remain outdoors after dark. It had to do with varied superstitions.

Most permanent dwellers in La Laguna believed in ghosts and in spirits that returned from the ever after to repent for their sins or to punish the living. Most of their beliefs were based on old legends that were common in many parts of Mexico.Afew of their superstitions were only common to that Baja California Sur lagoon area. There were stories about large creatures that flew over the villages late at night and

about ferocious half-man, half-animal beasts that came down from the mountains to meander nearby, howling and trying to drive away the people that currently lived on that land.

There was also the story of a teenager named Aidé, a young woman who drowned in the lagoon and who, according to that legend, was “pulled into the water by the jealous sea.” It was a myth that had been around in La Laguna for a long time. Most locals believed thatAidé often returned from the ever after, in the form of a spirit, to remind everyone with her cry that no woman must ever attempt to upstage the allure of the sea and its bays.

According to local lore,Aidé was a beautiful woman that took leisurely nightly walks along the edge of the lagoon.At times, she would also bathe in its waters. The sea, called la mar in Spanish and believed to be a female, became enraged byAidé’s presence and also jealous of her beauty.According to the legend, to punish the young girl, la mar decided to “pull her” into the water and drown her.

“Ya llegué, mamá,” Juanita said to her mother as she entered her house.

“I’m back, mom.”

Luis was no longer with her; he had already gone inside his own home. The dog wasn’t allowed indoors, so Gordito stayed outside.

“I was getting worried about you,”Alejandra replied. “It’s almost dark and I swear I was beginning to hearAidé crying.”

“Is she really a ghost?” Juanita asked.

“No,” her mother said. “It’s un espíritu,Aidé’s soul, returning to make sure we don’t behave inappropriately.”

“What’s the difference between ghosts and spirits, mom?”

“Ghosts just scare people,”Alejandra said. “Spirits help people. They return to prevent us from repeating the same mistakes they made when they were alive.”

“Gracias, amá,” Juanita told her mother.

After having a snack, Juanita washed her hands and her face in a sink located next to the back entrance to the house. She was ready to go to sleep.

“¿Me vas a contar un cuento, mamá?” she asked her mother as she walked to her bed.

Juanita wanted a bedtime story.

“Of course,” her mother replied. “Children need to go to sleep with happy thoughts and a nice cuento.”

Alejandra had often told her daughter traditional tales such as Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, and Little Red Riding Hood, but at other times she had made up stories that included subjects and themes that were born in her imagination. One of those invented cuentos had to do with a girl namedArco Iris. Juanita loved hearing theArco Iris story.

Once in her bed and properly tucked in, Juanita made several jerky body movements, until she found a comfortable sleeping position. Once that was accomplished,Alejandra stroked Juanita’s face and gave her a kiss on the cheek. She also made the sign of the cross on the girl’s forehead.

That going-to-bed drill usually took a few minutes.

“Once upon a time,”Alejandra said in jest, as she began to tell her theArco Iris story.

“No, mom, don’t start like that. Say it the way you always do it,” Juanita replied as she pulled the blanket over her shoulder and adjusted her body position in her bed again.

It was sort of a test. If Juanita didn’t complain, it meant that she was already falling asleep. It didn’t take long for that to happen once she was in a comfortable position in bed.

“Arco Iris was very young, perhaps not even ten years old,”Alejandra said as she began to tell the bedtime story. “She wanted to go to the forest and hunt just like the boys did, but she wasn’t allowed to do so because she was a girl.”

Alejandra noticed that Juanita had closed her eyes already, so she paused and said nothing for a few seconds, waiting to find out whether there would be a reaction to the silence.

“Come on, mom,” said Juanita in a sleepysounding voice. “Keep telling me aboutArco Iris.”

“The young girl was not about to let others decide what she could or could not do,”Alejandra said. “So she decided to build a bow, and also arrows, similar to the ones the boys used. She planned to watch and learn from those whose job was to make them in her tribe, so she would be able to build something just as good as what the men used.”

OnceAlejandra noticed that Juanita had fallen asleep, she stopped talking. She then touched the side of her daughter’s face, stroked her hair a few times, and again kissed her on the cheek.

Alejandra went then to the kitchen to complete a few remaining chores. She would also go to bed soon. Manuel was already sleeping. He usually went to bed early since he had to be at work by five in the morning. As she lay in bed,Alejandra could clearly hear the sound made by the bay water as it splashed on the edge of the lagoon. She could also hear the erratic winds that prevailed most of the year, and that usually howled throughout the night.

CHAPTER TWO

Fetching water for Don Julián

EVERY

SATURDAYAND Wednesday Juanita and Luis fetched lagoon water for an old man named Don Julián, someone who lived near them and also next to the lagoon. The water was used to replenish five 55gallon barrels that stored saltwater to be used for a mini-desalinization plant that he built behind his house. Juanita’s dog would always tag along whenever they fetched water. Juanita and Luis received twelve pesos each for their labor every time they worked regardless of how much water was required to top off the tanks. It was an easy task most of the time. The water was carried in two five-gallon plastic jars that were held in place by metal supports that Don Julián had built onto the small bed of an old Radio Flyer toy wagon. To make it easier to pull heavy water loads, he switched the original wheels of the cart with small, inflatable tires. The children used one-gallon plastic bottles to retrieve seawater from the edge of the lagoon and to fill the jars on top of the cart. Once the large jars were full, they would pull the Radio Flyer and the load to Don Julián’s backyard and to a platform next to the 55gallon tanks. The water was then transferred to the tanks using gravity force and a hose.

Besides welcoming the twice a week stipend, Juanita and Luis felt proud of their participation in the energy generating process.

Topping off the tanks was a task that Don Julián had been doing by himself for years, but something that had recently become more difficult for him to accomplish as his body began to suffer the aches and physical discomfort caused by aging.As he thought about paying somebody to haul the seawater, he mentioned it to Juanita, just in case her parents knew

someone who might be interested in doing the work. She immediately replied that she wanted to do it and that she would get Luis to help her. Don Julián was at first opposed to having children doing the task, but he eventually relented, especially after being bombarded by Juanita’s unending insistence on giving them the gig. Once he decided to have them haul the water, he mentioned to both of them that they had to have their parents’permission to do the work.After getting that approval, he built a wooden platform at the edge of the lagoon to make it safer and easier for the children to extract the water.

Both,Alejandra and Manuel, had predicted that Juanita and Luis would stop hauling water after a few weeks, that they would get tired of having to do the work on an ongoing basis. But they were wrong. Close to a year later, both children were still hauling saltwater for Don Julián. Getting paid to do the work was probably a big incentive.After all, it was a lot of money for them.

Soon after getting her first stipend, Juanita began to save part of the money in tin cans that she hid in different parts of the house. Each can had a name taped on it. One said, “For University,” another one, “For Books,” a third one, “For Dolls.” One can, the one that was usually empty, had “For Emergencies” written on it. Juanita called the cans her treasure. Luis also saved part of his earnings.

The mini-desalinization plant was a crude concoction put together by Don Julián to produce fresh water, to be used to generate energy.After years and years of trial and error, he eventually figured a way to remove the salt from the lagoon water by running it through a slow and repetitive process that used sunlight, glass tubes and solar power to transform it into distilled fresh water. Some of the liquid was lost due to evaporation, but the remainder was used to feed a crude power generating system that created electricity by turning heated water into steam and running it through a turbine. The electricity was used to power a few

household appliances and lights and to feed two sets of battery units, to continue to run the household goods at night and to restart the small steam power plant.

According to what he had told others, he learned about this method of generating energy from articles in Mecánica Popular, the Spanish language version of Popular Mechanics, a magazine he avidly read. Although most people that knew him called Don Julián an inventor, he often said that he was no inventor. That he was just a tinkerer.

He also dabbled in the construction of an endless number of gadgets, but it seemed that everything that he built was done in a way that minimized waste. The power plant, for example, had a glass shield over the turbine that captured the steam before it evaporated into the atmosphere. The cooled water would then run down under the glass, usually a car windshield, and fall through a filter and into a container below. The recycled salt-free water was later poured into one-liter bottles that over the years gained popularity and demand for the product, not only among the villagers in La Laguna, but with the inhabitants of nearby communities.

Some people believed that the water had medicinal qualities, too.

The sediments that were left at the bottom of the mini power plant were also sold in packets and used as common kitchen salt.

On Wednesdays, Juanita and Luis usually hauled the water after school; on Saturdays, they did it early in the morning so they could have the rest of the day for other matters, but mainly to play outdoors.After a while, the gig became more fun than work and easier to accomplish. On this particular day, however, Juanita wanted to finish hauling water as soon as possible so they could go to their secret mound earlier and spend more time watching the whales.

“Apúrate,” Juanita told Luis.

She wanted him to work faster so they could finish early.

“I am hurrying,” Luis replied as he again submerged the one-gallon container into the lagoon.

Luis had gotten distracted by a flock of loud seagulls that were flying overhead. He wondered why they were making such a racket.

Juanita’s dog was also distracting Luis. He kept barking at him and then running up and down the edge of the lagoon as if trying to tell him that there were more small fish than usual swimming in that area.

“That’s enough,” Juanita told her dog. “No more barking.”

“How many more trips do we need?” Luis asked Juanita as they poured the current load into the last 55gallon barrel.

“One more,” said Juanita, jumping off the platform and motioning to Luis to pull the wagon back to the lagoon.

Once they finished topping off the tanks and after collecting their pay, instead of going right away to the mound, Juanita and Luis decided to remain at Don Julián’s house for a while since he was about to make a batch of candy, a rare, sweet delight made from a special type of cactus named biznaga. They had seen him make that candy several times before and were already somewhat aware of the process.

To keep the children busy and to get them involved in the effort, Don Julián decided early on to ask for their help in exchange for a few pieces of the biznaga candy. One of their assigned tasks was to fill a burlap sack with the cotton-like substance that was extracted from inside the top of the biznagas. Once it was full, they would tie the sack and stomp on it to soften the cotton-like matter.

Making the candy was a two-day affair. On the first day, Don Julián would remove and clean the stem of the biznaga, a special type of prickly barrel cactus, and cut it into small chunks. He would then put them in a large pot and cook them for a while. Once cooked, he would place the candy on top of an outside table to let it

dry. It took at least a day for the chunks to crystallize and be ready to be eaten.

Biznagas grew wildly in the nearby foothills. Although he picked them freely, he believed in replacing them, saving the scraps from the cactus to be used as cuttings to produce new plants, spreading them over the areas where they grew.

“From these scraps,” he said to the children that day, as he placed the cuttings in a wooden box, “more biznagas will be born.”

“How long does it take for the biznagas to grow?” asked Luis.

“Along time,” said Don Julián. “That’s why we have to plant a lot of them.”

He also explained that the biznagas were wild and required many years to give fruit and that it was the responsibility of all people to plant them so they would always have them available.

“If we all do our jobs, we will be able to enjoy the fruits that grow in the wild,” he added.

“I like the biznaga candy,” said Juanita. “I like it a lot.”

“I’m glad you like it,” said Don Julián, “but it’s becoming very rare because many people who pick biznagas from the hills do not plant more of them as replacements.”

Luis and Juanita enjoyed listening to Don Julián talk about plants and other nature matters. That was one of the reasons for often visiting him. They usually had plenty questions to ask, queries about a myriad subjects that intrigued their young lives. This time, however, their interest was centered on the wild plant that would eventually become a sugary and tasty candy that no one else made in the area, so he continued to talk more about biznagas.

“It’s a tough plant, a true survivor, is wild and was growing on these hills way before any man was ever here,” he said.

“Do you know what kind of plant it is?” he asked them.

“No,” said Luis.

“It’s a cactus,” he explained. “You know, like nopales.”

“I like nopales,” said Juanita. “My mother makes them with eggs. But she removes the thorns from them before she cooks them.”

“I’m glad you mentioned the thorns, Juanita,” said Don Julián and explained that the sharp thorns protected the plants from predators, especially those that wanted to suck the water from the cactuses.

He also mentioned that the thorns were really leaves that helped the plants grow and keep the moisture from evaporating.

“Cactuses store large amounts of water, that’s why they’re able to survive in the hot desert,” he added.

“They’re pretty, too,” said Luis. “And they have different colors.”

“And they’re wild,” said Don Julián, “like that wild seagull that seems to be chasing Gordito.”

“Get over here, Gordito!” yelled Juanita. “Get over here!”

“When will the biznaga candy be ready?” asked Luis.

“Tomorrow,” said Don Julián. “Late tomorrow.”

CHAPTER THREE

About dinosaurs, paella and snails

“WHATARE YOU doing mom?” asked Juanita as she walked into the house and noticed that her mother was cleaning and separating seashells.

“I’m getting ready to build more of those figurines that you saw before and really liked,” said Alejandra and smiled at her daughter.

She then picked a prototype she had just built and handed it to Juanita. It was one meant to look like a woman.

“I’m going to help you, mom,” said Juanita as she placed the piece on her hand and held it against the sunlight. “I will build figurines in the shape of whales.”

“Thank you, Juanita, I’m looking forward to your help,” saidAlejandra.

“Don Julián is going to have biznaga candy for sale soon, mom,” her daughter said as she placed the figurine on the kitchen table. “Luis and I helped him make it.”

“How did you help him?”Alejandra asked.

“We stuffed the cotton balls inside a sack and jumped on it,” she explained to her mother. “We also helped him pick up the scraps, so he can plant more biznagas on the hills.”

“Did you finish topping off the tanks with saltwater?” her mother asked.

“Yes, we did and Gordito helped too, scaring the seagulls so they wouldn’t get close to us while we pulled the water from the lagoon.”

Juanita then took out the twelve pesos that she had earned from a small purse that she usually carried with her. There were two five peso and two one-peso coins. Don Julián knew that Juanita split her earnings

with her mother, so he always tried to give her the correct change.

“These are the six pesos for our family savings,” said Juanita as she gave the money to her mother.

“Thank you, Juanita,” saidAlejandra, adding “maybe we can buy a car now.”

“I will be happy with a bicycle,” said Manuel from the other end of the room.

He was already at home, back from work.

“I want a bicycle, mom,” said Juanita.

She had wanted to own one since she was six years old.

“Well, maybe a bicycle will be, one that you can share with your father,” said her mother.

“I don’t mind sharing,” said Juanita. “But I want a girl’s bike and I don’t know if dad wants to ride a girl’s bike.”

“I don’t mind,” said her father, “as long as it helps me run my errands.”

Alejandra had already ordered a bicycle for Juanita from Don Miguel, a traveling salesman who came by the lagoon once a month. The bike was supposed to arrive soon.

“Okay Juanita, you said that you were going to help me build figurines,” saidAlejandra.

“Can I do it later, mom?” asked Juanita. “Luis wants me to go with him to the mound.”

“Fine,” said her mother and smiled at her daughter.

Juanita called Gordito as she went outside. Luis was already waiting for her.Afew minutes later they were at the mound, again calling the whales.

“Domitila!” cried Juanita from the top of the dirt hill as she tried to get the attention of that whale.

“Domi!” she shouted again.

Luis was also calling the whales.

Not long after starting their shouting, several whales began to show their heads above the water in a faraway spot.

“There they are,” Juanita screamed loudly. “There they are.”

“Hi, Domi,” yelled Luis at one of the larger whales.

“It’s not Domi, Luis,” said Juanita. “She doesn’t have the five spots on her tail.”

“Who is she, then?” asked Luis.

“It must be Susana,” said Juanita. “That whale is very good looking, and Susana is very good looking.”

“Look at that baby whale,” said Luis. “I bet she was just born.”

“She’s beautiful,” said Juanita. “But she’s so small.”

“Are you going to give her a name?” asked Luis.

“Yes, let’s call her Bolita. She is like a little ball; she’s puffy,” said Juanita.

“Hi, Bolita!” yelled Luis at the calf.

The whales were more than a kilometer from the edge of the lagoon, but Juanita believed that they could hear their shouting. She kept telling them to come closer to the edge.

“Come, come here, so we can talk to you better,” she shouted.

Juanita had learned a lot about whales from Don Julián and from Karl Wagenhoffer, a university student who was doing research in La Laguna.

“The whales are very smart,” Juanita told Luis as they both took a break from their yelling.

“Are they as smart as Gordito?” Luis asked Juanita.

“Just as smart. Dogs are very smart too, especially Gordito,” replied Juanita.

“Not all dogs, some dogs are very dumb,” said Luis.

“I don’t think so,” said Juanita. “All dogs are very smart.”

The two children and Gordito remained at the mound for a while. Once they noticed that it was getting late, they decided to leave. Besides, they had

gotten tired of so much shouting, and it seemed that the whales had also gotten tired of going underwater repeatedly and doing so much frolicking. By then they had already stopped their antics and started to swim away from the spot in the lagoon where the children had first seen them.

As Juanita, Luis and the dog climbed down the mound, a large lizard ran quickly from under a rock and later hid in a bush not far from the mound. Gordito barked and ran after it but wasn’t able to catch it.

“Did you know that lizards are just like dinosaurs?” Luis offered.

“I don’t think so,” replied Juanita. “Dinosaurs were different.”

“How do you know that?” asked Luis.

“Because I read about it. Dinosaurs were very large and had warm blood. Lizards have cold blood.”

“But I think lizards and dinosaurs look the same,” replied Luis.

“They look alike, but they’re not alike,” said Juanita. “Alot of animals look alike, but they’re not the same.”

Juanita was an avid reader and someone who had learned a lot about animals.

They decided to stop at Don Julián’s on their way back since they had a question for him. The discussion about lizards and dinosaurs had veered into talking about snails and about Don Julián having eaten snails in Spain. Luis didn’t think it was true.

“Snails are bugs and if people eat them they will get sick,” Luis said to Juanita on their way back from the mound.

“¿Qué tal niños?” said Don Julián as the two stopped at his house. “Don’t tell me, if you’re coming for dulce de biznaga, I might as well tell you up front that it’s not ready yet.”

“No, we came by because Luis wants to know something,” said Juanita.

“What is it Luis?” asked Don Julián.

“Is it true that you eat snails?”

“Only once,” he said. “Once.”

“Did you get sick?” asked Luis.

“No, but I didn’t like eating them. I did it because my friend from the ship said that I had to taste them so I could find out for myself how great they were.”

Don Julián worked as a merchant marine before settling in La Laguna. Both Luis and Juanita were aware that he had traveled all over the world.

“How did they taste?” asked Juanita.

“Not good. They were chewy, buttery and expensive.”

He explained that he ate the snails at a wellknown restaurant called Los Caracoles, in Barcelona, Spain, when his ship made a port call there.

“We went to that restaurant to eat paella, but we ended up also eating snails,” Don Julián added. “One of the merchant marines in the group, someone who had previously eaten there, suggested that we should try snails as an appetizer.”

Luis was cringing as he heard the snails anecdote.

“We were all young and adventurous, so it wasn’t difficult to convince any of us to try the snails,” Don Julián explained.

“But for a moment I had second thoughts,” he added. “I didn’t really want to eat something that looked just like the slugs I had seen sliding their slimy bodies on the ground.”

“What is paella?” asked Luis.

“It’s a famous dish from Spain, prepared on a large pan. It’s made with rice, saffron, tomatoes, beans, lots of olive oil and is cooked with different types of meats, especially seafood,” explained Don Julián. “The meat in the original paella consisted only of chicken and rabbit.”

“Rabbit?” exclaimed Juanita. “Rabbits are nice. People shouldn’t eat rabbits.”

“No, we shouldn’t eat rabbits,” said Don Julián. “Or snails.”

CHAPTER FOUR

Ahuge salt plant is coming

MANUELAND OTHER fishermen usually gathered on Sundays at a café near La Fridera, the fish processing plant, to watch TV and soccer games from throughout Mexico. The television signal was received by a satellite dish antenna atop the tiny building. It was an old TV installed at the café mainly for the tourists that visited the lagoon during the whale season, but a device that got plenty use from the locals throughout the year.

Manuel enjoyed watching fútbol, especially when his favorite team played, Club Deportivo Guadalajara, also known as Chivas Rayadas (striped goats) and Rebaño Sagrado (the sacred herd). Just like other faithful Chivas fans, he would always make the sign of the cross whenever anyone said the name Chivas or Chivas Rayadas or Rebaño Sagrado.

On this particular Sunday, Manuel’s team was not scheduled to play, he eventually found out. It had already won that week’s game the day before, he also found out, against some team from the north.Although he wasn’t happy for having missed the match, he was glad that his beloved Chivas had won. Son instead of watching other soccer games, Manuel decided to spend the time at the café having a beer and talking to his friends. Some were neighbors and one a coworker, a man that went out to fish with him on the same boat.

The usual conversation among fishermen was centered on their work, talking about the fish they caught or didn’t catch. They also talked about other fishing matters and about soccer. Once in a while, their conversation would be about other topics, like politics, or the need for public improvements in the area. That particular Sunday’s topics were no different. Manuel

and his friends talked about the usual things they always discussed.

One of the men at the table, though, mentioned something that surprised almost everyone. He said that he had heard that the Mexican government had finally approved the building of the world’s largest salt plant in Laguna San Ignacio. It was a project that had been mentioned in passing a few years before, but a rumor that most people at La Laguna had already forgotten.

“Who told you that?” Manuel asked.

“One of the tour guides that works for a whale watching camp who claimed that he heard it from another guide, someone who had just arrived from Guerrero Negro,” said Eleazar, the man that had broken the news regarding the imminent construction of the salt plant.

“I guess it’s true,” said Ricardo, a fisherman that had lived in La Laguna for more than twenty years, and who explained that he had heard the same rumor recently, from someone else who was also from Guerrero Negro.

“Maybe now we will have a doctor in town and electricity,” he added.

Eleazar explained that he had been told that a salt plant would not be good for the whale tourist business, based on what had happened in Guerrero Negro a few years back.

The salt plant in that other area, he was told, had driven the whales to other locations, and away from that bay.

“The whales will still come here,” said Ricardo. “Maybe they won’t remain in the same spot, but they will still come to the lagoon.”

“Do you think the salt plant will have job openings?” asked someone else.

“Probably,” Ricardo replied. “I bet there’s going to be a lot of work available. I also think that there are going to be a lot of things getting built around here besides the plant.”

Manuel was mostly quiet during much of the conversation, but he liked what he was hearing. The possibility of building a salt plant offered a ray of hope, he thought. Maybe they wouldn’t have to move somewhere else after all, somethingAlejandra had been wanting to do for a while.

Afew minutes later the conversation turned to other matters. Manuel, however, didn’t stick around long; he preferred to go home instead and take care of a chore that he had put off for a while, but a task that needed to get done. He had to install a hose to a handwashing sink to divert the wastewater to an area outside. For years the wastewater had been temporarily stored in a bucket below the sink and emptied outside as needed.

Installing the hose was the easy part; digging a ditch to hide it underground was the hard part. That was perhaps the main reason for having postponed the chore for a while.

Once at home, he began to dig the required ditch with a shovel.Alejandra wasn’t at home; she had gone to visit a nearby neighbor. By the time she returned, Manuel was half-way done with the digging.Alejandra was surprised to see him at home so early.

“¡Qué milagro!” she said in jest, meaning “what a miracle.”

He smiled at her and continued to dig.

“I thought you were going to watch soccer at the café,” saidAlejandra.

“I was,” replied Manuel, “but there were no good games being shown.”

“Come on, you felt guilty about not having installed the hose, didn’t you?” she said. “You just got tired of looking at it, lying on the floor and me nagging you and nagging you about it, didn’t you?”

“No, I just had to get it done,” said Manuel.

Alejandra had mentioned the nagging just to say something, mostly because she didn’t know why Manuel had returned home so early.

“I love you, honey,” saidAlejandra. “Thank you for installing the hose. Now we won’t have to be taking out the sink bucket and drain it at all hours.”

She then went inside to cook. Once in the kitchen, she began to clean two medium size corvinas, sea bass that Manuel had caught and had brought home the day before. It was very tasty fish, especially if it was prepared with the right condiments. She noticed that there were no limes left but needed them to help flavor the fish once it was cooked and to add it as dressing to the cabbage salad that she wanted to mix. Vegetables and fruits were a rare commodity in La Laguna, but once in a while a few of them could be found at a nearby shack.

“Juanita!” yelledAlejandra at her daughter through the kitchen’s open window. “Go see if the store has limes.”

“Sí, mamá,” said Juanita and took off toward the shack that served as a very, very small store in that part of La Laguna. Luis and Gordito were with her. Alejandra watched them through the window, seeing them run to the place.As she began to slice the cabbage into thin strips, she noticed that Juanita had already begun to run back to the house. She had a small bag with her.Alejandra felt relieved. She was certain that she had found the limes that she needed for the meal.

CHAPTER FIVE

The saltworks rumor grows

IT DIDN’T TAKE long for the new rumor about the salt plant to spread throughout La Laguna. It was good news, it seemed, for almost everyone. Juanita found out about it at school during recess. One of the students in her class was telling someone else that his parents had mentioned that the government was going to build a salt plant in the lagoon and that a lot of good things would take place in the area.

“Roads are going to be built,” her classmate said, “and we are going to have large stores and movie theatres.”

“What kind of salt plant?” Juanita asked.

“I don’t know,” her classmate replied. “But it’s something big that is going to be built in the lagoon.A big plant. That’s all I know.”

Puzzled by the news, Juanita went back into the classroom and waited for her teacher to return from her own break. She wanted to ask her about the salt plant.

Was the lagoon going to be covered with salt? she asked herself as she waited at her desk and as she became invaded by a multitude of questions and heartwrenching quandaries.

“What about the whales? Where are they going to live? Below the salt? What if the whales leave the lagoon forever and never come back?”

She imagined the whales completely covered with salt and remaining underwater for long periods of time to try to remove thye salt from their bodies.

“Oh, no!” Juanita cried quietly. “No!” she cried again, trying to hold back tears that were already welling up in her eyes.

“What’s wrong, Juanita?” her teacher offered as she entered the room and heard the stifled moaning.

“I have to ask you something,” Juanita replied after a while, once she half-way regained her composure. “Is it true that the government is going to build a salt plant?”

Tears were already rolling down Juanita’s face.

“That’s what I hear,” her teacher said. “But right now it’s only a rumor. No one from the government has come here to tell us that they are going to build it.”

The rumor, explained the teacher, was based on information brought to the area by different people. But she didn’t have any more details, she added.

“What kind of salt plant?” Juanita asked.

“What do you mean by what kind?” the teacher asked.

Juanita had already stopped her sobbing and was able to communicate in a collected manner, informing her teacher about the small salt Don Julián had near the lagoon. She also explained in full detail how salt was created in that small plant.

“It’s something similar but much, much larger,” the teacher said. “And it’s sort of a farm in the water that grows salt instead of fruits or vegetable.”

The teacher added that she had seen a similar salt plant while visiting Guerrero Negro.

“It was just like a farm, with a lot of white fields at the edge of that bay,” she explained.

The industrial salt complex at Guerrero Negro was then known as the largest salt works in the world, supplying commercial salt to the United States and countries inAsia, among them Japan and Taiwan. The company that operated that plant was the same one that wanted to build the saltworks in Laguna San Ignacio.

Juanita’s teacher was a 22-year-old woman known to her students as Ms. Jiménez. She was serving her one-year civil service commitment in La Laguna, a requisite she needed to fulfill to become a certified teacher. She had wanted to take care of that required year at a place close to home, near La Paz, in the southern end of the Baja California peninsula, but was sent to La Laguna instead. She did not welcome the

assignment but figured that a year would go by quickly. However, after living and teaching there for less than a month, she began to develop a nagging disgust toward the area because of the lack of infrastructure and what she called “its nothingness.” She hated having to teach there and religiously counted the days left before going back home.

“Will all of the water be covered with salt?” asked Juanita.

“No, just a small portion of the lagoon and just at the shallow areas near the edge,” Ms. Jiménez said.

She added that the project would be good for La Laguna, that good things would happen because of it.

Juanita didn’t say anything. She just stood there, dumbfounded and awestruck.

“The salt plant will be good for us,” Ms. Jiménez repeated.

“No, it will not,” Juanita replied after a while. “The whales will go away and will never come back.”

“The plant will bring jobs to La Laguna and many improvements to the area.And God knows we need them. The plant will be good for this place.”

Although she tried to remain composed, Juanita was unable to fight back the heartache that continued to invade her and began to cry again. They were subdued whimpers at first, but as she saw her classmates file back into the room, the weeping became an uncontrollable sobbing.

The students wondered what had caused her to cry. Once Ms. Jiménez disclosed the reason, they all laughed loudly.

“How silly,” one student said as she threw up her hands.

With her teacher’s permission, Juanita had already gone outside to try to regain her composure. But she was still able to hear her classmates’off and on laughing.

Afew minutes later, she wandered back into the classroom. She was no longer crying.

Some classmates giggled as she walked to her desk. That and other signs of mockery, however, soon stopped, after Ms. Jiménez admonished them and told them not to be so disrespectful.

Juanita tried hard to remain calm and collected and not have direct eye contact with anyone. She also tried hard to pay attention to the teacher, take good notes, and learn what was being taught. But she continued to think about the salt plant.

On her way home from school and after bidding goodbye to her friend Luis, Juanita decided to visit Don Julián to find out if he knew anything about the salt plant. When she arrived at his house, he was about to store some items that had just been delivered to him by Don Miguel, the traveling salesman.

“Hi, Juanita,” said Don Julián as he noticed her standing near the porch of his house.

She returned the greeting and then told him that she had a very important question to ask.

“What’s in your mind, Juanita?” asked Don Julián.

“Did you know that a salt plant is going to be built in the lagoon?” she asked.

“That’s what I hear, but it’s still just a rumor,” he replied.

He was surprised by her question. He wondered how she had gotten the information.

“What is going to happen to the whales if the plant is built?” asked Juanita.

“Probably nothing,” Don Julián said and smiled at Juanita.

“But how are the whales going to swim with so much salt in the lagoon?”

“If a salt plant is built, it will take place near the inland end of the bay, in the shallow areas, away from the places where the whales swim,” Don Julián explained. “Only a very small part of the lagoon is going to be used by the salt plant.”

He added that salt making was a simple operation which would not get in the way of the whales

and reaffirmed that it would take place away from the main body of water. He didn’t want to provide more detailed information; he thought that it would be too difficult for Juanita to understand.

“Will the whales return to the lagoon once the plant is built?” she asked.

“I think so,” he replied.

Juanita felt somewhat relieved after Don Julián explained how the salt plant would operate, but some doubts still dwelled in her mind. Something in her head kept telling her that it was not good for the whales. She felt better, though, after talking to him.

“I think they have something waiting for you at home,” Don Julián said.

He didn’t tell her what it was since it was a surprise gift, a bicycle. He was just trying to make her happy and help her forget the salt plant. Juanita then waved goodbye and took off running toward her house, but the words about a surprise did not register in her mind.

Don Julián returned to his interrupted chore and began storing the items that had been delivered earlier by Don Miguel. There were two solar panels, which he took to the back of the house; he then returned to the porch to inspect the rest of the merchandise.Among the items were four magazines, two new editions each of the Spanish language versions of Popular Mechanics and Reader’s Digest. He placed them on one corner of the table, away from the older magazines. He noticed that a book he had ordered many months before had finally arrived; it was a hard-to-find copy of a novel titled La vida inútil de Pito Pérez. He had read it before, when he was very young, but wanted to read it again. He thought it would make more sense to him now that he was older. It was a book written by José Rubén Romero in the late 1930s and was known in English as The Useless Life of Pito Pérez. It was a comedic take on Mexican politics and everyday life as seen by a two-bit thief and town drunk. It was funny and candid, Don Julián remembered.

Once he completed stocking his recent purchases, he pondered about the salt plant. It was a subject matter that he had previously decided to leave temporarily alone, hoping that the plant wouldn’t be built. But Juanita’s visit and her concerns about the livelihood of the whales compelled him to mull over the proposed project again.

It was a painful reflection, mainly because he believed that the construction of such industrial complex would destroy the region’s habitat. The whales would adapt, he thought, but the environment would get hurt. Population growth would tip the balance of nature and would affect the status quo, he also believed.

Up until then, the proposed project had been opposed by some Mexican intellectuals and foreign environmental groups, mainly from the United States, so there had been hope that it wouldn’t be built.

But it was now closer to becoming a reality.A reliable source had recently mentioned to Don Julián that the Mexican government had already agreed to allow a Japanese conglomerate to build the plant. Both parties, Mexico and that multinational company, were going to be partners in the saltworks.

“That’s how things are done often; important environmental concerns don’t matter much,” he said to himself, after hearing the latest scuttlebutt regarding the project. “It’s all about greed.”

Don Julián continued to mull over the salt plant, but the pondering bothered him. In a way, he didn’t want to think about it anymore. Yet, he couldn’t let go of the mulling. He felt tired, too, though it was still early.

“It’s probably stress,” he told himself as he sat on an old wooden chair next to the table where he kept some of his books and magazines.

He turned toward the water as he rested and observed the lagoon for a while.

“What a grandiose bay,” he said to himself silently.

Pedro Chávez

He then reminisced about La Laguna and about how much he had enjoyed that area, the out of the way next to the lagoon place where he had lived for years.

“You were right Pito Pérez.And you weren’t crazy,” Don Julián added as he peeked at the cover of the book that was delivered to him that day. “We’re the ones who are crazy. We have to be to do the things we do to ourselves.”

Don Julián sat there a while longer and continued to think about what he believed was going to be La Laguna’s ominous future. Once he noticed that it was getting late, he got up and went back to doing his chores. He still had to check the water levels on his mini desalinization plant and turn on the small power transformer that converted direct current intoAC electricity and provided power to the lights and other gadgets in his home.As he approached the back of his property to do the checks, he thought about Juanita and her unambiguous concern regarding the salt plant and the whales.

“She sure is a smart kid,” he said to himself.

Once he reached his own mini-salt plant, instead of doing the checking and the turning of the switches in an expeditious manner, as he usually did, he perused the mechanical creation that he had built a few years back, a contrivance that he put together perhaps by pure necessity. He then stuck his hand in one of the containers and picked up a chunk of sea salt.After lifting the lump with his fingers, he pressed it hard against the palm of his other hand. It broke down easily. The applied pressure turned the lump into white, sparkling grains. Don Julián then turned over his hand, allowing the salt to spill back into the container.

“You’re a valuable asset,” he said loudly, directing his words toward the salt that was leaving his hand. “The Japanese and theAmericans need more of you and our Mexican government is going to allow you to grow in our lagoon.”

As he proceeded to check the water levels, he noticed the Radio Flyer wagon with the two five-gallon

containers resting on top of it. It was neatly parked next to a water tank. He again thought about Juanita, but also about Luis, as he observed it and remembered how much they loved working and fetching water for the tanks. He also thought about how they appreciated being part of the salt-making process and telling others that they had helped make the salt that many people used at home in La Laguna. He remembered other things, too, mostly personal stuff, and instead of doing his work, Don Julián just stood there for a while, thinking of the past. He no longer felt tired.

He also reminisced about the time when he first came to the lagoon area to stay just for a few weeks, mainly to mend a broken heart. Don Julián shook his head as he remembered that mostly forgotten personal life passage. He also smiled as he recalled the pretext that brought him to La Laguna.

“I better get back to work,” he said to himself and smiled again.

As he continued his last chore, he removed one of the containers and dumped the harvested salt into a 55-gallon wooden drum that served as temporary storage for the product. He removed as much salt as he could from the flat; some of it was stuck to its sides.

“Salt, you are powerful, and you are now going to destroy La Laguna,” Don Julián said to the chunks of salt that were stubbornly attached to the sides of the flat. “You are powerful, and you are now going to kill our soil and our vegetation.”

The late afternoon wind was blowing stronger than usual, whipping the area with a loud, howling hum. The waves hitting the edge of the lagoon were becoming nastier, making a repetitive splish, splash sound as they went over the side. It was still light outside, but the wind-driven moaning of the lagoon announced the coming of night. Don Julián again realized it was getting late, so he hurried, checking again the water levels and adjusting the rate and amount of seawater being released into the salt making containers.

He looked forward to going to bed so he could rest. Once he finished his chores, he went inside the house. He tried to think about good things, but a capricious feeling of anguish and a stubborn image depicting a painful future continued to hang over him.

CHAPTER SIX

The bike no longer matters

BOTH PARENTS WERE at home when Juanita arrived that afternoon. They were planning to surprise her with a bike that had just been dropped off by Don Miguel. It was bright red with 24-inch wheels, probably too big for a nine-year-old, but a good fit for the long term. Because of the lowered top tube, shaped especially for girls, Juanita would not have any problem reaching the pedals, they thought. It had no training wheels, but Alejandra planned to walk along her daughter as she learned to ride, holding the bike whenever needed.

“Surprise!” they both yelled as Juanita entered the house.

She saw the bike and walked to it to touch it and said thank you but displayed no sign of happiness.

“What’s the problem?”Alejandra asked her after sensing that something was wrong.

She had expected to see her daughter jump up and down with joy after seeing the bicycle and finding out that it was bright red, the color that she had often mentioned she wanted.

“The whales will not come to the lagoon anymore,” Juanita said and began to cry loudly.

Her mother was puzzled by the comments and her weeping.

“Why do you say that?” her father asked.

Juanita didn’t say anything; she was still crying. She then ran toward her mother and hugged her.

After talking to Don Julián about the salt plant and being reassured that it wouldn’t harm the whales, she felt confident that it would be so. But during her short walk home, she began to worry again, and the more she thought about it, the more certain she felt that the salt plant would be bad for the whales.

“Why do you say that about the whales Juanita?” her mother asked as she stroked the girl’s hair.

“The whales won’t come back because of the salt plant,” Juanita replied.

She had already stopped sobbing but was still hugging and grabbing her mother’s blouse.

“Who told you that?” asked her father.

“No one. I just know. I just know,” Juanita said.

“No, I meant, who told you about the salt plant?” Manuel revised his question.

He was surprised that others in the area knew about the supposed salt plant project. It had been only a couple of days since he had heard about it.

“I found out at school,” she said. “And my teacher said that it would be good for us.”

Juanita let go of her mother to wipe off her tears with the sleeve of her blouse. Vestiges of dried, older tears were still visible on her face. She then hugged her mother again.

“I also found out about it today,”Alejandra interjected. “Don Miguel mentioned it to me.”

He said it in passing, indicating that the salt plant would be a good thing for La Laguna, but that it wouldn’t benefit his business. He did well in small, isolated communities, he explained, where he had no competition from local stores.

“I want the whales to return,” said Juanita. “I don’t want a salt plant.”

“The whales will return,” said her father. “This is their home.”

“I don’t want a salt plant,” Juanita repeated. “I want the lagoon to stay the same.”

“Don’t worry, it will, it will always be the same,” said her mother. “Would you like to learn how to ride your new bike?”

“No, not right now,” said Juanita as she sighed. The news about the salt plant still weighed heavily on her mind, but she had found a comforting respite hugging her mother. Once she felt better, she had a bite to eat and after resting for a while, took up

her mother’s offer and asked her to teach her how to ride the bike.Alejandra welcomed the request, hoping that the training session would help get her daughter’s mind away from thinking about the whales and the salt plant.

But there was something else thatAlejandra entertained: she was hoping to get to ride the bike herself. It was an opportunity that she had been anticipating for a while. She often wondered, however, whether she could still perform the pirouettes she once executed when she was young and rode her own bike at high speeds and with dexterity.

It didn’t take long for Juanita to learn the basics of bike riding after they all went outside and participated in the training activity.Although she fell several times as she tried to ride it, Juanita soon figured how to prevent the bicycle from tilting to one side or the other.

Her dad was hoping to perform some riding tricks too, but he didn’t get a chance to do so. Mom and daughter were having too much fun playing the parts of instructor and student and they didn’t stop their carousing until it got dark.

Alejandra, just like Manuel, didn’t get an opportunity to ride the bike that afternoon. She would do it the following day, she told herself, while her daughter was at school.

Juanita went to bed earlier than usual that day. She fell asleep thinking of her bicycle and about adding streamers to the handlebars and maybe a basket in front to carry her schoolbooks.

SHE HAD SOMEWHAT forgotten about the salt plant as the days passed, especially after learning how to ride the bike well and spending time enjoying it. Traces of past worries regarding the proposed saltworks, though, still lingered in the back of Juanita’s mind.

On a Saturday, as she and Luis fetched water for Don Julián, the subject matter came up again as they

ran into Karl Wagenhoffer and Juanita decided to ask him about the salt plant.

Karl was a young man that had been living in La Laguna for several months, doing research about the whales, the lagoon, and the area’s habitat. He had in the past and on numerous occasions answered many of Juanita’s questions regarding a myriad of scientific topics, but mainly about the gray whales that yearly visited the lagoon and about some of the land animals that made the nearby hills their home. He seemed always ready to comply and try to provide answers in layman’s terms to her questions. Besides, he enjoyed talking to Juanita, listening to what he called “her insightful comments,” and addressing her queries. He was at La Laguna working on his doctorate degree’s required thesis, but also on a study for a joint program between his school, UC San Diego, and the Autonomous University of Baja California’s oceanography investigation center in Ensenada. He lived in a tent, close to one of the camps near La Fridera.

Most researchers that came to the area usually introduced themselves to most people to let them know what they were doing. Karl did the same.As part of his work, he often interacted with the local population, asking questions about La Laguna for his scientific investigations and gathering other appropriate information.Among those previously interviewed were Manuel,Alejandra and Juanita.

Karl was originally from Philadelphia. While in high school in that city, he became captivated by the world of scientific research after reading Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Soon after reading that tome, he decided to dedicate his life to the study of animals. He was especially intrigued by the principles of evolution, natural selection and other research done by Darwin in the Galapagos Islands. One of his early goals was to one day visit that SouthAmerican archipelago and do scientific research there, just like Darwin had done. To prepare himself for that objective,

he studied Spanish in high school and in college and took advantage of every opportunity he had to practice that language with others that spoke it, often visiting Philadelphia’s Latino cultural and commercial hub, El Centro de Oro, to do so.

When it came time to decide which college to attend, he chose UC San Diego, one of several schools that had accepted him. But once there, he became obsessively attracted to the study of marine life instead and soon changed his major.After completing his undergraduate work, he remained in San Diego, working part time at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at La Jolla and doing graduate study at the university. Because of his marine life background and his Spanish language skills, he was selected on a couple of occasions for scientific projects done in partnership with the Baja California state university in Ensenada.

When Karl wasn’t at his tent, he could be found writing on a notepad at one of the tables at the café near La Fridera. On this particular day, when he ran into Juanita and Luis, he was on his way to a place called La Base, a tiny community next to the lagoon. Right after he greeted the children, Juanita asked him if he knew that a salt plant was going to be built at the lagoon.

“I’ve heard about it,” said Karl and added, “why do you ask?”

“I just want to know. I don’t want a salt plant. I want the whales to always return to the lagoon,” Juanita replied.

The response puzzled Karl.

“What makes you think that the plant is going to keep the whales from returning?”

“The whales won’t be able to swim in the lagoon. It’s going to be filled with salt and the whales don’t like salt,” said Juanita.

Karl tried to find simple words to use to explain to her that the salt plant would not affect the whales.

“Look, if the salt plant is built, it will be located at the end of the lagoon, in shallow waters,” Karl explained.

“The only thing that might come in contact with the whales would be the barges, you know, large, flat boats that will have to be used to transport the salt to ships someplace out here,” he added. “By the way, whales like salt. That’s why they come to this lagoon, because the water is very salty.”

Karl knew there were other factors that attracted the gray whales to Laguna San Ignacio, but he didn’t want his response to be too complex or to add more concern to an already worried child. In his research, Karl had concluded that the whales chose lagoons along the Baja California peninsula not just for the warm, shallow waters and high salinity, but also because of the relative tranquility. In his own assessment of the impact that a salt plant might have on the whales, Karl had written in his research documents that part, if not all, of the peacefulness in certain sections of the lagoon would be lost.

“I don’t want the salt plant, I want the whales to come back,” said Juanita.

“They will come back, even if there is a salt plant,” Karl replied.

He wanted to assure her that the whales’annual migration would not be affected by the construction of the plant but felt that he hadn’t been able to diminish Juanita’s concern.

“The whales are very smart,” Karl told Juanita. “Do you know why the gray whales have been around for millions and millions of years?”

“Because they are big and the other fish cannot hurt them,” replied Juanita.

“That’s somewhat true,” said Karl. “But they have survived for so long because they are smart and are also able to adapt.”

He wondered whether Juanita understood the meaning of the word “adapt,” so he decided to explain it.

“To adapt means to change. It also means to survive, you know, to stay alive,” Karl said. “Animals that adapt, survive, and their descendants stick around for a long time, too. Do you understand what I’m trying to say?”

“Yes, I understand. I read about it in one of Don Julián’s books,” said Juanita.

Karl felt relieved.

“Well, gray whales have been adapting for a long time.And they are very smart. Many, many years ago when it got too cold and frozen at their home, they found other places where they could live for a while. That’s how they ended up coming here. When the water at home is no longer frozen, they return there, because there is a lot of food for them there,” Karl said.

“And because they like it there, because that is their home,” said Juanita.

It seemed to Karl that she was no longer concerned about the salt plant.

“True.And I’m going to tell you something else about the gray whales,” Karl added. “They try very hard not to scare us. When people get close to them, they don’t move much and sometimes let people touch them because they don’t want to scare us. Do you know why?”

“Because they’re nice,” said Juanita.

“True again, but I think it is also because they’re watching us, and they don’t want us to be scared of them. We think we’re watching them, but they’re really watching us. They are not afraid of us.”

“I know they’re not afraid,” said Juanita and repeated a comment she had made before. “They’re not afraid because they’re big and other fish cannot hurt them.”

Karl was intrigued by Juanita’s response and the supposed invulnerability of the whales.

“Unfortunately,” Karl said to himself, “most fish cannot harm them, but some humans can.”

CHAPTER SEVEN

Aletter writing campaign

AFTER TALKING TO Karl that morning, Juanita and Luis went about their work routine. They continued getting water from the lagoon, hauling it to Don Julián’s backyard, and topping off the tanks.After making several trips and completing their work, Juanita and Luis put away the Radio Flyer wagon and the water containers and looked for Don Julián to tell him they had finished doing their chore. They found him working inside the house, grinding clusters of salt and filling small bags with it, which would be later sold to others. He was happy to see the children.

“Thank you for bringing the water,” he told Juanita and Luis and gave each one their pay.

“But I have a surprise,” he added. “I have some biznaga candy that I saved for you.”

An entire batch of candy that he had recently made was already gone. It was mostly sold to Don Miguel, who would then sell it to customers throughout his route.

“Thank you,” said Juanita as she took her share of the candy.

Luis was trying to fight off Gordito. The dog kept jumping up, trying to grab the sweets from his hand.

“The water tanks were low today,” said Juanita. “I don’t know why.”

“It’s been a little hot and that causes the water to evaporate faster,” Don Julián explained. “But that’s good. It speeds up the process.”

“Thank you for the biznaga candy Don Julián, it’s very good,” said Luis.

He had already eaten the first piece in his packet.

“I’m glad you like it and I’m glad I remembered to save some for both of you before I sold the rest of the batch. I also saved some for Karl. He’s been bugging me about it for almost a week,” Don Julián responded.

“I talked to Karl about the salt plant a while ago,” said Juanita. “He says that the whales will always come back to the lagoon even if a plant is built.”

“Sure, they will,” said Don Julián. “This place belongs to them.”

“Karl says that the whales are very smart and that they are not afraid of people,” said Juanita. She hadn’t touched the candy. She was saving it for later.

“He’s right; the whales are very smart and so is he.”

Karl had met Don Julián for the first time soon after arriving at La Laguna. He was immediately awed by the energy producing concoction that he had built in his back yard and also by its by-products: fresh water and salt. He also enjoyed talking to him.Although the initial conversations were mainly centered on the needs of his research, soon the topics turned to other matters, like finding food sources in desert plants, planting vegetables in salty soil, and replenishing wild sources of food both on land and in the lagoon.

“But I don’t want the salt plant,” said Juanita. “It’s not good for the whales.”

“I don’t want it either, but for different reasons,” Don Julián said.

He waited for Juanita’s reply before saying anything else.

“I don’t want the salt plant and the whales don’t want it either. I know they don’t want it,” she added.

Don Julián smiled at both children and told them that he had decided to do something that might help stop the building of the salt plant.

“This is what I plan to do to try to stop its construction,” Don Julián said. “I’m going to write letters to important organizations that might be able to help.”

After finding out that the construction of the salt plant was no longer just a rumor, Don Julián decided to do whatever he could as an individual to try to stop the project from getting built.Ascheme that soon flourished in his mind had to do with launching a personal letter writing campaign, contacting worldwide environmental organizations that might be interested in trying to stop the building of the salt plant in Laguna San Ignacio. He had read about similar campaigns in an article in Selecciones – the Spanish language version of the Reader’s Digest magazine.

The letter writing idea was a sort of last-ditch effort by Don Julián to do something about the matter and to tell others that the salt plant would be detrimental to La Laguna’s habitat. In a way, he felt that his effort would not help much but that it had to be done.

“But it’s better than doing nothing about it,” he told himself.

Once he decided to launch the last-ditch scheme, he mentioned it to Karl and asked him whether he could come up with a list of possible organizations to contact. Karl said that such a plan was already underway but agreed to help him, adding that he would put together a list of potential contacts for such a campaign. He had several sources that could provide him the information that was needed, he explained, as well as contacts in the two universities that sponsored his research, UC San Diego and UABC. Karl added that both educational institutions worked with several major environmental groups that not only promoted the conservation of natural resources throughout the world but were already involved in an effort to stop the construction of the saltworks in Laguna San Ignacio.

“Can I also write letters?” asked Juanita.

“Of course, you can. I was going to ask you to help.”

“What about me? I want to write letters, too,” said Luis.

“Yes, I was going to also ask for your help.”

Don Julián decided to mention his letter writing plan to both children mainly to appease Juanita and to imply that he also opposed the construction of the salt plant. He never thought that they would be interested in writing letters.

“The more people that write letters the better,” he told them, “but you have to do what you promise.”

He wanted to instill a sense responsibility in them, so they would go through with the effort.

“This is what you need to do. You have to write a letter in your own words that states why you don’t want the salt plant to be built.”

He gave each one a few sheets of paper so they could write their sample drafts on them.

“I will tell them that if the salt plant is built, the whales will not return to the lagoon anymore,” said Luis.

“Very good,” said Don Julián and then explained that the same content would be used in every letter.

“I’m going to write my letter tonight,” said Juanita.

Juanita and Luis thanked Don Julián for being allowed to participate in the letter-writing effort. Both then went home, but they had plans to get together that afternoon to go to the mound and visit the whales.

Once in her house, Juanita told her mother about the letters.Alejandra listened to her attentively and congratulated her for getting involved. She figured that the campaign was just a make-believe project that Don Julián had conceived to support her daughter and help her forget about the salt plant. But she welcomed the scheme with open arms.

“It’s good to see her happy,” she told herself. Juanita went to work on the letter right away. She did it on the kitchen table. Her mother would peek at her off and on, trying to appear as oblivious as possible. Less than half an hour later, Juanita had a finished product.

“My name is Juanita,” she stated in the letter. “I am nine-years-old. I live next to a lagoon that is liked by big whales. Some are small too. They come here every winter because they like the lagoon. They also like me. They always listen to me when I talk to them. I like them a lot. They are very nice, and they play in the water. Somebody very nasty wants to build a salt plant in the lagoon. If that happens, the whales will not come back. I need your help. Please do not let the nasty people build the salt plant.”

After making a couple of corrections and writing a clean copy of the letter, Juanita showed it to her mother.

Alejandra started reading it.As she read each word and each sentence, a pleasant sense of awe grew in her mind. She was surprised by the content’s clarity and the brief and simple way her daughter used to state her case. It was good, she thought. She hadn’t realized that Juanita could write so well.

“Excellent; I like the letter a lot,”Alejandra said and handed it back to her daughter.

Luis wrote his letter the following day. It was simple and short too, and also to the point. He showed it to his parents that evening after confiding in them that he was involved in a project that involved writing letters to important people all over the world.

“We want them to stop the construction of the salt plant,” Luis told his parents. “Juanita is writing letters too.”

Both parents were surprised by the news. Luis was too young to be writing letters, they believed.At the same time, they wondered whether the letters would ever be mailed. They congratulated him for getting involved in the campaign, though, just to be nice to him.

After school on Monday, Juanita and Luis showed their letters to Don Julián. He read them and told them he liked them.

“Both of you are good writers,” he said and gave each one several blank pages to write the first ten

letters. He still didn’t know how many names of organizations he was going to get from Karl but felt that there would be at least ten of them. He told Juanita and Luis where to leave space for the name of the individual and the organization. That would be completed later once he received the list, he explained to them. The envelopes would also be addressed at that time, he added. Don Julián said to be as careful as possible when writing the letters, but not to worry if mistakes were made, and to just try to correct the errors, crossing them out on the same piece of paper. Besides the ten blank pieces of paper, Don Julián gave Juanita and Luis an ink pen.

“We have to use ink,” he said. “No pencil.”

The letter writing effort had temporarily helped ease Juanita’s anguish regarding the proposed salt plant, but she still worried about it.

Once she finished writing her ten initial letters, she decided to visit the mound more often to warn the whales about the pending salt plant. Both Luis and her dog would tag along.

“Don’t let them build the salt plant! Don’t let them build the plant!” Luis and Juanita would yell in unison once the whales appeared on the horizon.

Gordito would accompany the shouting with his usual relentless howling and barking.

“Don’t let them build the salt plant! Don’t let them build the plant!” they would yell again and again until they got tired, or it started getting late.

Gordito would also get tired and after a while he would stop his barking and howling and just drag his tail across the ground.

TALKABOUT THE salt plant had somewhat subsided in La Laguna a month or so after the arrival of the most recent rumor, the one that had announced the plant’s imminent construction. Just a few people mentioned the project, here and there, but not with the same initial fervor. The general feeling, however, was that it would be built. But no one seemed to know when that would

take place or if much would change in the area any time soon.