HANDBOOK FOR A DIVERGENTARCHITECTURE

By Megan Moloney

By Megan Moloney

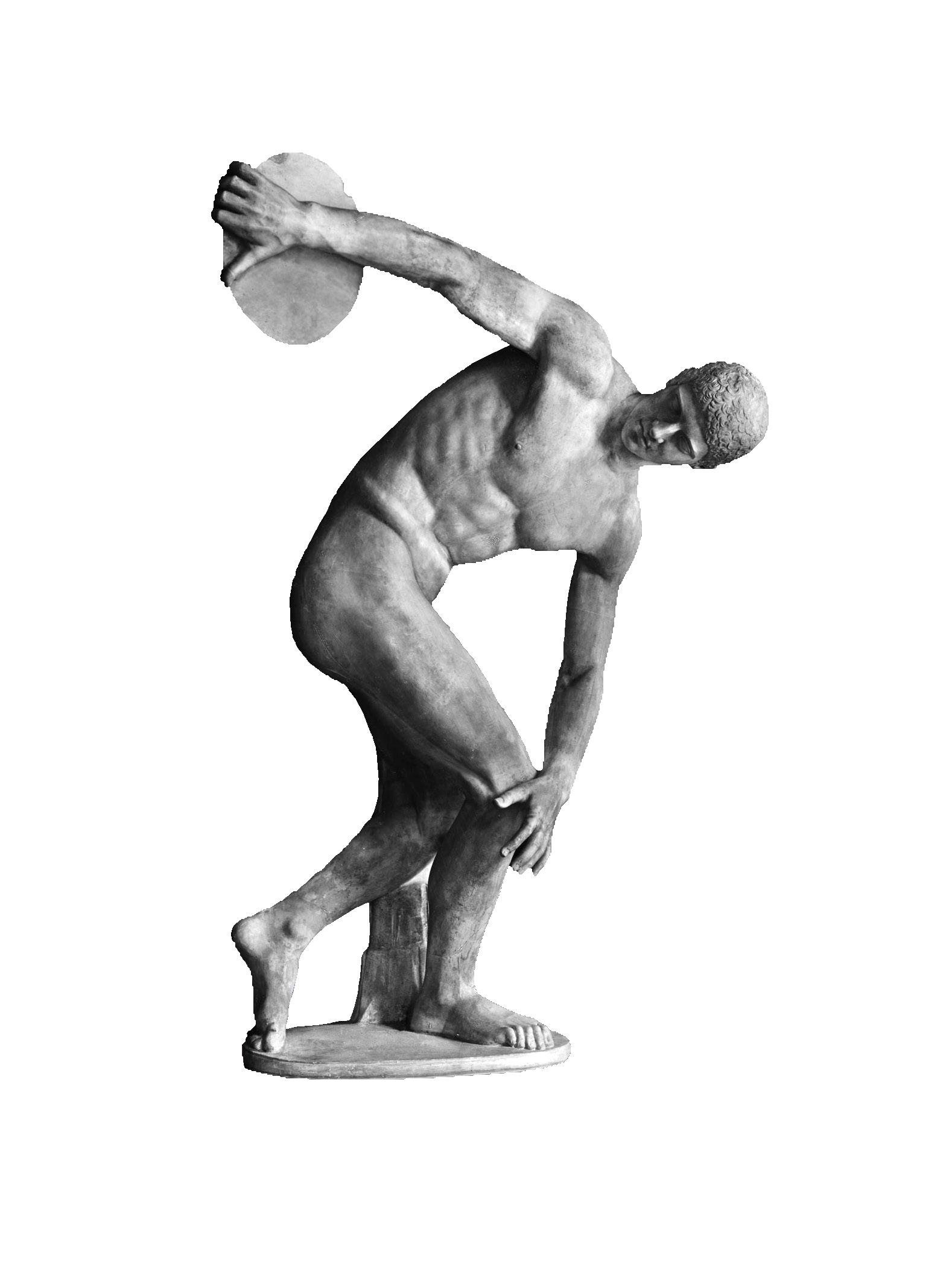

Society promotes a narrow criterion upon which we define the “Ideal Human.” He is the standard by which we measure beauty. If you are not him, your best chance at success is to spare no expense in your effort to look like him, act like him, and think like him. To retain his authority and value, the Ideal Human has, throughout the course of history, made concrete a set of intricate political, social, and economic systems that reinforce his position. Ideal Humans who hold power in society are slowly becoming more aware of the lack of diversity amongst them, and some are trying to use their privilege to make change. However, the changes that result are often superficial at best, pulling at the leaves of the weed while neglecting the root. This is the case in architecture, which, despite a constant evolution in style, remains entrenched in Ideal systems. These systems reinforce architecture’s reliance on conventional programs, circulation, and materiality. Because the qualities of buildings are conventional and therefore immediately understandable and totally unstimulating, they deny the user any chance at renegotiation of the space through other interpretations. This is at odds with the fact that buildings serve a population beyond just Ideal Humans, and

their diverse users have a more dynamic and indeterminant metric of success. These users have a wide variety of personalities, preferences, and values, which reflects the neurodiversity - or the evolutionarily developed variance in brain structure - of the human species. Within this spectrum of neurodiversity exists people who are considered “neurodivergent”, “… [those who have] a brain that functions in ways that diverge significantly from the dominant societal standards of ‘normal.’” This neurodivergent population naturally operates outside of the Ideal systems that drive architecture. Architecture’s allegiance to these Ideal systems stifles the potential for neurodivergent people to flexibly interpret their environments to fit their needs. As an alternative to Ideal architecture, a (neuro)Divergent architecture subverts conventional categories of architecture to accommodate alternative systems and modes of being. Divergent systems of thinking are independent of the static, conventional thought that gives Ideal systems of thinking their power, and instead are shaped by ever-evolving stimuli, assigning value and meaning to spaces based on their qualities instead of using labels.

architecture subverts conventional “Ideals” of the built environment and instead actively evolves and adapts through an engagement with a neurodiverse population to accommodate alternative systems and modes of being.

“to [those with visible, disabilities], society says, must adapt and adjust!’ [neurodivergent people], says, ‘You must adapt and

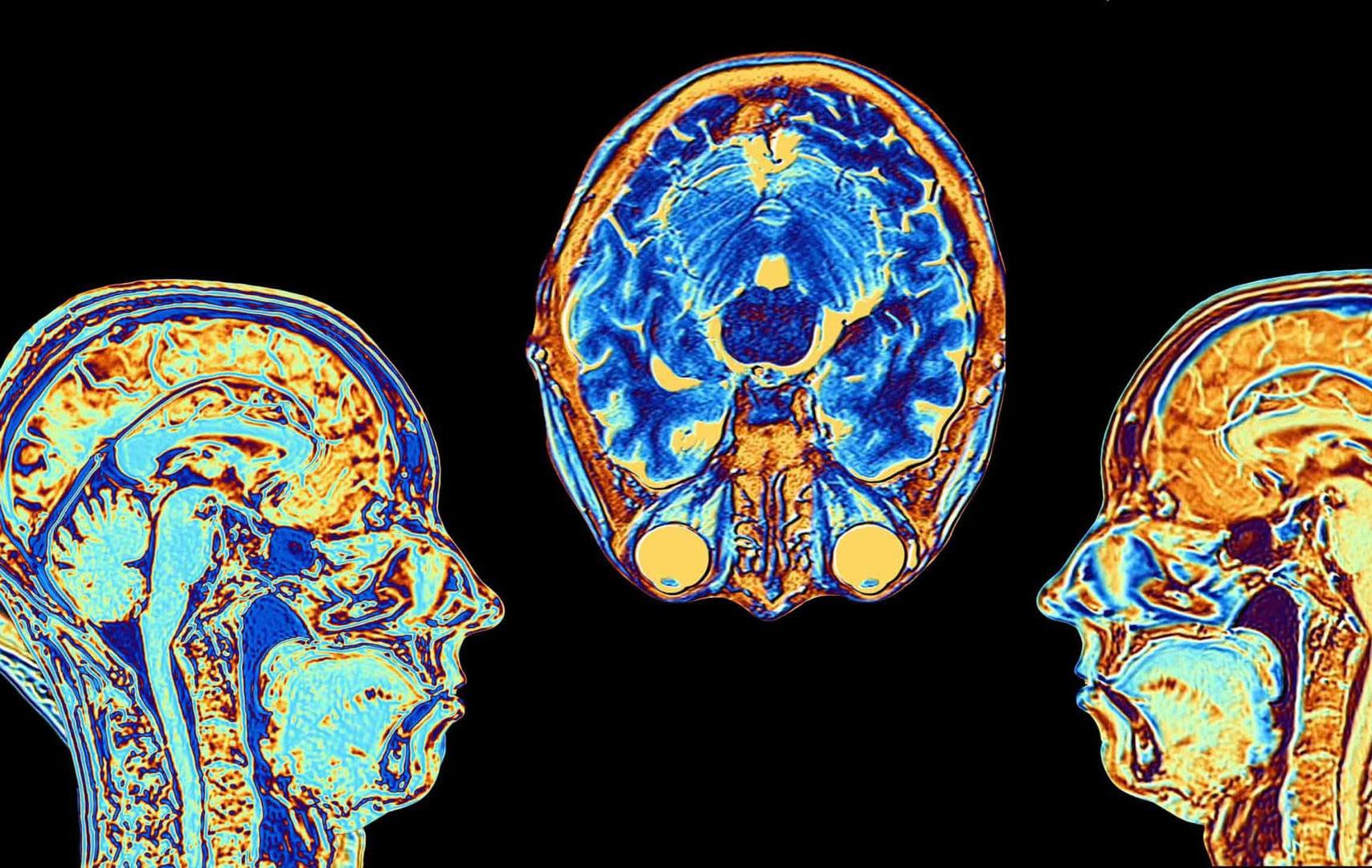

The term neurodiversity was first used by Judy Singer in the 1990s, and it refers to the naturally occurring diversity of neurological structuring within the human species. It was adopted by many members of the autistic community, who recognized the word’s usefulness in expressing a new way of thinking about human brains, and from it they built the framework for a new view of autism. Since then, its use has since expanded to include people with ADHD, dyslexia, and dyspraxia. For most of the 20th century, these conditions were considered pathological in the Western world. The neurodiversity movement reframes them as not pathologies, but rather as variations in brain structure that evolved for distinct reasons. In fact, it’s suggested that neurodivergent people- people who “…[have] a brain that functions in ways that diverge significantly from the dominant societal standards of ‘normal’” due to variances in specific

physical

‘We adjust!’ To people], society and adjust!’”

and scientifically identified genes- may be responsible for many of humankind’s biggest leaps forward. Because a caveperson who was neurodivergent was less likely to be sitting still or socializing around the fire, they were more likely to discover new things and investigate new ideas; they were the hunters, explorers, and innovators of their communities. It is because of this predisposition that I am interested in researching neurodivergent people and neurodivergent thought for my thesis. Neurodivergent people are not oriented to operate at peak performance within the (capitalistic) systems and modes of being that society deems “Ideal.” By default, the systems and modes of being that they operate within instead are the opposite of “Ideal”, or what I will refer to, in absence of an opposite-pair for Ideal, as “divergent.” In her book, Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism, Kyra Anderson puts it this way: “To [those with visible, physical

disabilities], society says, “We must adapt and adjust!” To [neurodivergent people], society says, “You must adapt and adjust!” With my thesis, I hope to uncover an (neuro)Divergent architecture that subverts “Ideal” systems and modes of being and actively evolves and adapts with the participation of the people who operate within divergent systems and modes of being.

In this section, I have provided the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) symptom identification information for both autism and ADHD. The phrasings are reflective of those that are used in actual diagnostic testing, and therefore they reveal the medical and/or pharmaceutical attitude towards these brain types. People with ADHD (Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder) have two categories of symptoms, according to the NIMH.

The first is inattention- people with ADHD may often:

• “overlook or miss details

• make careless mistakes…

• have problems sustaining attention…

• not seem to listen when spoken to directly…

• not follow through on instructions and fail to finish [tasks]… or start tasks but lose focus and get easily sidetracked…

• have problems organizing tasks and activities, such as what to do in sequence…

• avoid or dislike tasks that require sustained mental effort…

• lose things necessary for tasks…

• be easily distracted by unrelated thoughts or stimuli

• be forgetful in daily activities…”

The second is hyperactivity-impulsivitypeople with ADHD may often:

• “fidget…

• move around in situations where staying still is expected…

• feel restless…

• be unable to play or engage in hobbies quietly…

• be constantly in motion or ‘on the go,’ or act as if driven by a motor”

Autistic people also have two categories of symptoms (National Institute of Mental Health). Social communication/ interaction behaviors may include:

• “making little or inconsistent eye contact

• tending not to look at or listen to people

• rarely sharing enjoyment of objects or activities by pointing or showing things to others

• failing to/being slow to, respond to someone calling their name or to other verbal attempts to gain attention

• [for autistic people who speak] having difficulties with the back and forth of conversation

• [for autistic people who speak] often talking at length about a favorite subject without noticing that others are not interested or giving others a chance to respond

• having facial expressions, movements, and gestures that do not match what is being said

• [for autistic people who speak] having an unusual tone of voice that may sound singsong or flat and robot-like

• having trouble understanding another person’s point of view or being unable to predict or understand other people’s actions”

The second is restrictive/repetitive behaviors, which may include:

• “repeating certain behaviors or having unusual behaviors- for example, repeating words or phrases, a behavior called echolalia

• having a lasting intense interest in certain topics, such as numbers, details, or facts

• having overly focused interests, such as with moving objects or parts of objects

• getting upset by slight changes in a routine

• being more or less sensitive than other people to sensory input, such as light, noise, clothing, or temperature”

The diagnostic view, however, phrases all of these “symptoms” in a pathological sense. However, with the understanding of human neurodiversity as a result of evolution, and neurodivergence as a product of genetics rather than as a product of disease, the traits of neurodivergence read differently. Thom Hartmann, in his book The Edison Gene: ADHD and the Gift of the Hunter Child takes this approach in his list of traits that are typical of people with ADHD:

• “enthusiastic

• creative...

• non-linear in thinking (leap to new conclusions or observations)

• innovative…

• easily attracted to new stimuli

• capable of extraordinary hyperfocus

• understanding of what it means to be an ‘outsider’…

• impulsive

• entrepreneurial

• energetic”

And Penny Spikins, in her article “How our autistic ancestors played an important role in human evolution”, lists traits of autistic people like this:

• “exceptional memory skills

• heightened perception in realms of vision, taste, and smell

• enhanced understanding of natural systems

• focus on parts rather than wholes

• strong attention to detail

• strong visual and auditory learners

• excel in math, science, music, art”

Comparing the diagnostic and the neurodiversity-aware descriptions of neurodivergent people is very revealing. Diagnostic descriptions are not inaccurate observations of neurodivergent people as they operate in the world- they’re just

completely dependent on comparison to a non-existent “neurotypical” Ideal. The neurodiversity-aware descriptions evaluate the individual independently of any Ideal. They provide a much better understanding of the value and beauty of people operating in these Divergent modes of being.

The prefrontal cortex is responsible for “regulat[ing] thought and control behavior.” An active prefrontal cortex is key “in situations that require goaldirected actions, inhibition of irrelevant information, and contextually-appropriate modification of behavior.” One key similarity between neurodivergent people is that their prefrontal cortexes develop on a significantly different timeline and to a significantly different extent

than most people, according to Sharon L. Thompson-Schill’s research article Cognition without control: When a little frontal lobe goes a long way. This means neurodivergent people have a less active prefrontal cortex, sometimes described as “frontal immaturity” or “hypofrontality.” People that are not neurodivergent also experience hypofrontality at two times in their lives- as children and during REM sleep (dreaming). Hypofrontality is associated with difficulty in convention learning. Convention learning is the ability to “do and say and understand the right thing in the right context.” Convention learning helps people to operate within Ideal systems. But in some situations, convention learning can be restrictivewhen it comes to creative problem solving, this restrictiveness is known as functional fixedness. Functional fixedness “hinder[s]

flexible thinking…” when looking at a particular object “…because the representation of the object is sculpted by prior experience and expectations.” This means that within an Ideal framework, the number of possible uses for any given object is limited by the conventional labels that have been placed on it. People with less active prefrontal cortexes- children and neurodivergent adults, are not as subject to functional fixedness. This “flexibility of behavior can be interpreted as a stimulus-driven response: A mind that is at the mercy of its environment is not shaped by expectations or belief.” This is clearly a totally different mode of operation than the Ideal system allows for. It is this functional flexibility that allows neurodivergent people to generate a multitude of creative solutions to any given problem.

Current research on neurodivergent people makes it clear that there are unique benefits to Divergent systems of thinking. In my thesis work, I want to explore how people who operate in Divergent modes of being can be players in the development and adaptation of an Divergent architecture. Functional flexibility, as a shared trait between neurodivergent people, is one way in which the relationship between the human and the architecture can be made dynamic rather than static, because it is a mode of operation driven by incoming stimuli rather than preconceived notions. With further research and experimentation, I hope to come to a better understanding of how this mode could impact architecture and what new forms it could create.

The relationship between architecture and its users actively shapes the lives of both parties. Architects, however, rarely design in a way that is centered around the dynamism of that relationship. Instead, design orbits around the desires of a client that may not ever actually use the building. This client is often white, male, and rich. He considers financial gain to be the primary metric of a project’s success. In contrast, the occupants of the buildings are much more diverse than the men that commission them, and their metric of a project’s success is much more qualitative. My thesis explores architecture and the people that use it as flexible, evolving players with the potential to mutually benefit from each other’s continued existence. This essay will summarize the expert analysis of participation-centric

projects that continue to work for the communities that use them. There are two sources referenced: the first, an essay titled “Mass housing cannot be sustained”, by Jon Broome, primarily focuses on user participation in the preoccupancy, future-occupant-informed design; the second, a book titled “How Buildings Learn: What happens after they’re built”, by Stewart Brand, is about user participation in the adaptation of post-occupancy, existing buildings.

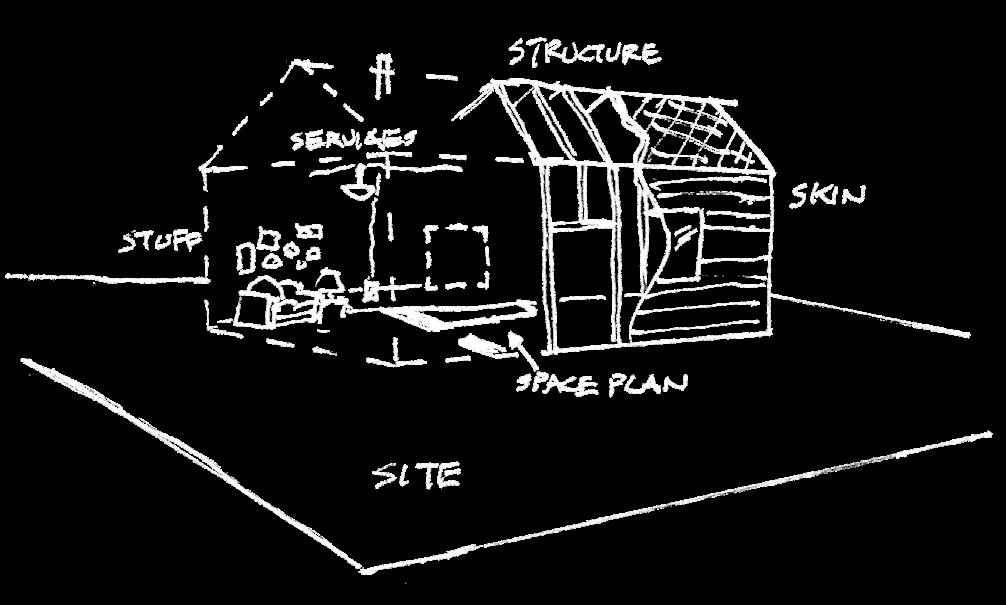

It’s worth noting that Broome’s essay directly references a small portion of Brand’s book, and the topic is one of shared importance for both authors: the evolution of a building over time. Brand, elaborating on work done by Frank Duffy of firm DEGW, “separat[ed] different

elements of a building with different timescales of change”. These six elements are site, structure, skin, services, space plan, and stuff. While elements like site and structure are quite permanent and “in charge” of the building, skin, services, space plan, and stuff are relatively easy to change. With the flexibility of these latter four elements, there exists potential opportunity for occupants to make the space work for them.

While it’s inevitable that some level of modification to a building will be done by its occupants, there is much to gain from a more deliberate attempt on the part of the architectural designer to understand the factors that influence user modification and building adaptation. Brand classifies which types of buildings invite user modification and which do not. In the former category are “Low Road” buildings, which Brand defines as “low-visibility, low-rent, no-style, high-turnover”. These stand in contrast with what he calls “magazine architecture”- architecture that looks great in photographs but that can immediately be called out as a failure with one walkthrough. Brand sets forth two buildings on MIT’s campus to demonstrate the two categories: the contemporary Wiesner Building, informally

known as the Media Lab and designed by starchitect I.M. Pei, and the World-WarII-constructed-to-be-temporary Building 20, MIT’s first interdisciplinary laboratory. The former was a $45 million failure that prioritized a magazine-cover-worthy atrium at the cost of much needed lab and office space for the scientists that use the building. Building 20, on the other hand, was “too hot in the summer, too cold in the winter, Spartan in its amenities, often dirty, and implacably ugly.” What made it work is the fact that it wasn’t precious; it was disposable. One occupant extolled the “ability to personalize your space and shape it to various purposes. If you don’t like a wall, just stick your elbow through it.” Brand points out that, at least within the university context, “Grand, final solution buildings obsolesce and have to be torn down because they were too overspecified to their original purpose to adapt easily to anything else.” In contrast, “temporary buildings are thrown up quickly and roughly” but their occupants “flourish in the low-supervision environment.” Broome’s essay supports the notion that an occupant’s sense of agency in bringing about the evolution of a building results in a rich occupant-building dialogue. When conditions of newness and preciousness reduce the occupant’s sense of agency

“While elements like site and structure are quite permanent and “in charge” of the building, skin, services, space plan, and stuff are relatively easy to change.”

to adapt the building to their needs, occupant-building dialogue is practically non-existent, instead outsourced to building management. Broome captures this dynamic with a quote from John Turner: “Deficiencies and imperfections in YOUR housing are infinitely more tolerable if they are your responsibility than if they are SOMEBODY ELSE’S.”

Brand enthusiastically promotes this “yes, it’s a mess, but it’s our mess” mentality. He wrote his book inside “a derelict landlocked fishing boat” that was fixed up by a gay couple who “acquired it for dockside trysts, fixing it up like a Victorian

cottage” and then occupied and worked on by a string of small businesses. In a Low Road building (or boat), Brand argues, “weather becomes a perverse attraction… you smell and feel the seasons. Weather comes in the building a bit. That sort of invasion we would condemn in a new building and blame the architect, but in a ratty old building- designed for some other use, after all- there’s no one to blame. Such buildings leave fond memories of improvisation and sensuous delight.” This is in line with Broome’s assertion that the occupant’s relationship to the building is far more importantand ideally more complex- than any

“If you don’t wall, just elbow through

outsider could perceive it to be.

The architectural designer can, with thoughtful consideration and action, facilitate the relationship between building and occupant. Broome suggests the use of “pattern language”, which was developed by Christopher Alexander in the late 1970s. According to Alexander, “A pattern language gives each person who uses it the power to create an infinite variety of new and unique buildings…” by, as Broome clarifies, “offer[ing] a vocabulary of design features which can make people’s experience of the… buildings where they live explicit and easy to understand, thus enabling them to participate in the development of ideas about their environment.” It is a set of 273 assertions that make clear why people like what they like about built environments. For example, one “pattern” is “Light on two sides of every room”- it’s a concise articulation of a condition that a nonarchitect processes only on the subconscious level. By presenting design issues in such an accessible way, architects and occupants can better understand each other and work together productively within a framework designed for their mutual success. One way to make this material is to use a design process like the

Segal method for housing. Perhaps best described as a mash up of Lincoln Logs and IKEA furniture, scaled up to building size, the Segal method makes building construction possible for occupants, and even whole communities, to participate in. Using simple grids and dry-joinery (screw, nail, and friction-fit joinery only- no wet joinery), the future occupants put in sweat equity as they make physical their plans. These are individualized versions of modular plans they have worked on in close, back-and-forth collaboration with the architect. The internal walls are all non-load-bearing, the windows and doors can be easily shifted, and the occupant has an intimate understanding of how their house is put together- they are perfectly set up to be able to adapt their house as needed over time, post occupancy. Brand has more to say about the post-occupancy stage. He feels that the architect’s role in post-occupancy buildings of any scale lies in helping the users to take advantage of the beauty of a misfit. Brand quotes Robert Campbell’s Cityscapes of Boston: “Recyclings fit best when the new use doesn’t fit the old container too neatly. The slight misfit between old and new… gives such places their special edge and drama. The best buildings are not those that are cut… to

fit only one set of functions, but rather those that are strong enough to retain their character as they accommodate different functions over time.” Brand expands upon this, saying that “obsolete buildings are fun to convert and a delight to use once converted.” They can be the perfect playground for an architect, because “originality is unavoidable.” The status quo, the off-the-shelf solutions we block into our drawings and models, simply don’t fit the bill. “Invention becomes a habit as you proceed.” And, architects are uniquely skilled to be the perfect mediator between the occupant and the space they want to adapt. We can enter a building that is being used for one particular purpose and visualize within that space how it could be adapted to serve a completely different purpose.

Through time-shifted lenses of pre- and post- occupancy, “Mass housing cannot be sustained” and “How Buildings Learn:

What happens after they’re built” establish a framework for both thinking about participation in architecture and making real. Awareness of what can and can’t change in a building, and at what rate that change occurs, is key to understanding why people form adaptive relationships with some buildings and not others. When we as architects acknowledge and anticipate the importance of those relationships, we can design to accommodate and even encourage them. Part of our role is to help buildings users to verbalize their desires and to use our technical expertise to aid them in taking ownership of their space, whether that looks like modifying an unbuilt plan or adapting an existing building to fit a new set of needs. This participation process is a chance for us as designers to both flex our creative muscles and equip and train others to do the same. This is at the core of my thesis- putting creative power into the hands of the users, and I plan to use this framework to do so.

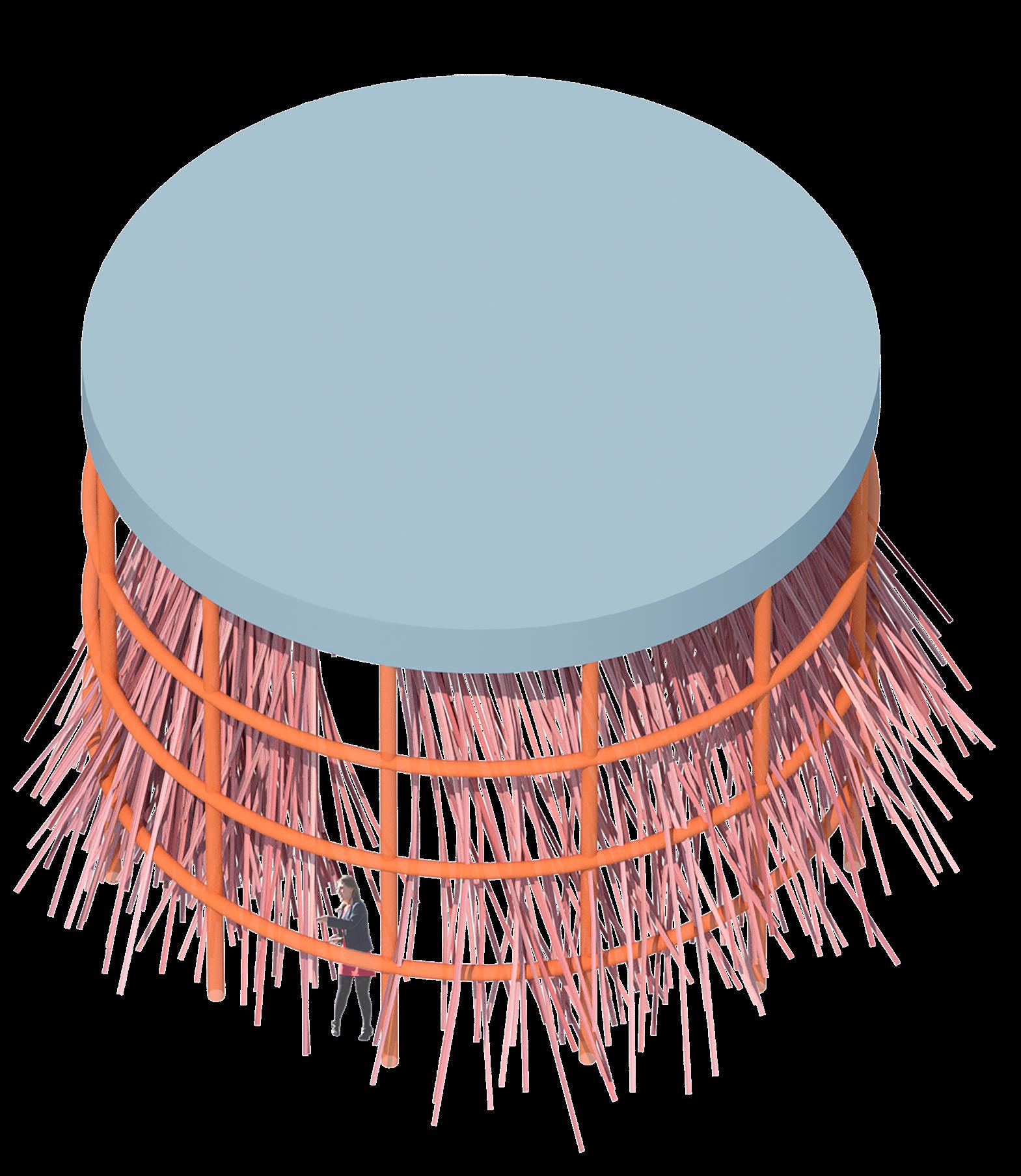

The wood panels that support this column can be rotated to be parallel to or perpendicular to the column. This adaptability allows the interior of the column to be variable in its exposure to its surroundings. The form inside of the column provides surfaces and masses for users to appropriate. The wood surface in the center is sitting height for people who prefer low stimulation. The fuzzy spheres towards the edges are more suited for people who like to stand or pace around the room, and the surrounding area is wide enough to comfortably take laps around.

The pink “hair” spilling from this column can be manipulated in a number of ways. It can be draped over the orange frame to maximize privacy inside, parted and gathered to allow for visibility and interaction with the space outside of the column, braided or knotted or knitted as a stimming tool (stimming is commonly done by neurodivergent people to express energy, reduce or increase personal sensory intake, or express emotions).

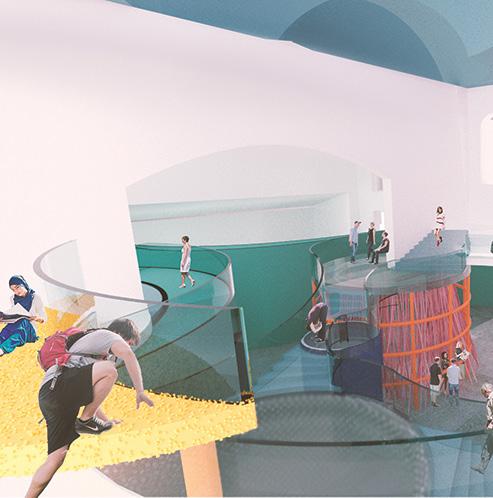

The once-functionally-fixed, Ideal auditorium space has been made Divergent and functionally flexible. Before, the architectural cues directed users to file orderly into rows of seats, face towards the stage, and sit still and quietly. Now, a series of Divergent interventions perverts those Ideal cues. A series of occupiable columns support

circulation ascending from the first to the second floor. These occupiable columns serve as semi-private to private spaces for small to medium groups, and each has qualities that make higher- and lower-stimulation modes of occupation possible: porous, adaptable, folded, fuzzy, hairy.

1, 3, 5: These platforms rest atop exaggerated columns (shown more clearly in bubbles 2 and 4) and provide spaces to gather of varying sizes. Their varying heights allow visibility of the space from multiple angles.

2: This column allows users to adjust its “walls” (a set of 2” x 6” panels of wood). The panels are mounted on

structural steel rods, and each individual panel can be rotated to face parallel or perpendicular to the center of the column. This allows for different levels of transparency at different points within the column, making it able to effectively serve people who prefer higher levels of stimulation and people who prefer lower levels of stimulation.

4: This column is woven and wrinkly. Its form allows moments of positive and negative space that can be used for a number of different purposes. Users can freely read/interpret these qualities and appropriate the space as they see fit.

On the balcony, a series of smaller platforms rise up amongst the space where there used to be rows of seating. Users can stand atop the platforms for a high-stimulation experience, sit below them for a low-stimulation experience, or occupy space in between to observe others using the platforms. Whereas the flow of energy in the space used to

be controlled by the stage that formerly stood underneath the arch (left side of render), the individual platforms at the balcony level decentralize the space, allowing user attention and movement to flow freely.

1: The sequence of stairs that takes users from the first floor to the balcony is repeatedly interrupted by large “landings”, which are actually the tops of the oversized columns that populate the space. This is Divergent circulation because it allows users to circulate at their own pace, taking as many “pit stops” as they desire. It also increases

the liklihood of chance encounters between colleagues, which often result in conversations and exchanges of ideas occurring that might not have otherwise occurred.

2: The “hair” on this column has been allowed to hang back from the frame, and a user inside is having a conversation with two other users outside of the

column. Another user is appropriating it as a window to the outside space as she reads.

3: The platform shown here is fuzzy, and allows for higher stimulation occupation above and lower stimulation occupation below

4: This platform is easily viewable from the entire room, and its location puts it in an acoustic position to allow for performances to carry well throughout the space.

The former Ideal lobby of St. Alphonsus Hall has been transformed into an Divergent gathering space. Before, users were expected to enter the lobby and proceed directly up the narrow stairs to the auditorium. Now, the entry space allows users to linger and mingle with help from the following qualities: broad entryway, multiple possible paths upon entry, wide

sittable stairs, multiple levels of vantage, a *hairy* “wall” between the entry and subsequent space.

1: Bleacher-style stairs curve around the corner of the entry space and provide circulation to the basement level of the building.

2: A balcony allows for a point from which users can survey the space and gain an understanding of the layout of the the building. This is especially important for neurodivergent people to

feel comfortable within the space.

3: A hair wall divides this entry space from the rest of the building. This allows for some noise control without making the space feel restricted. This hair can be draped and gathered to increase permeability between the entry space and the rest of the building.

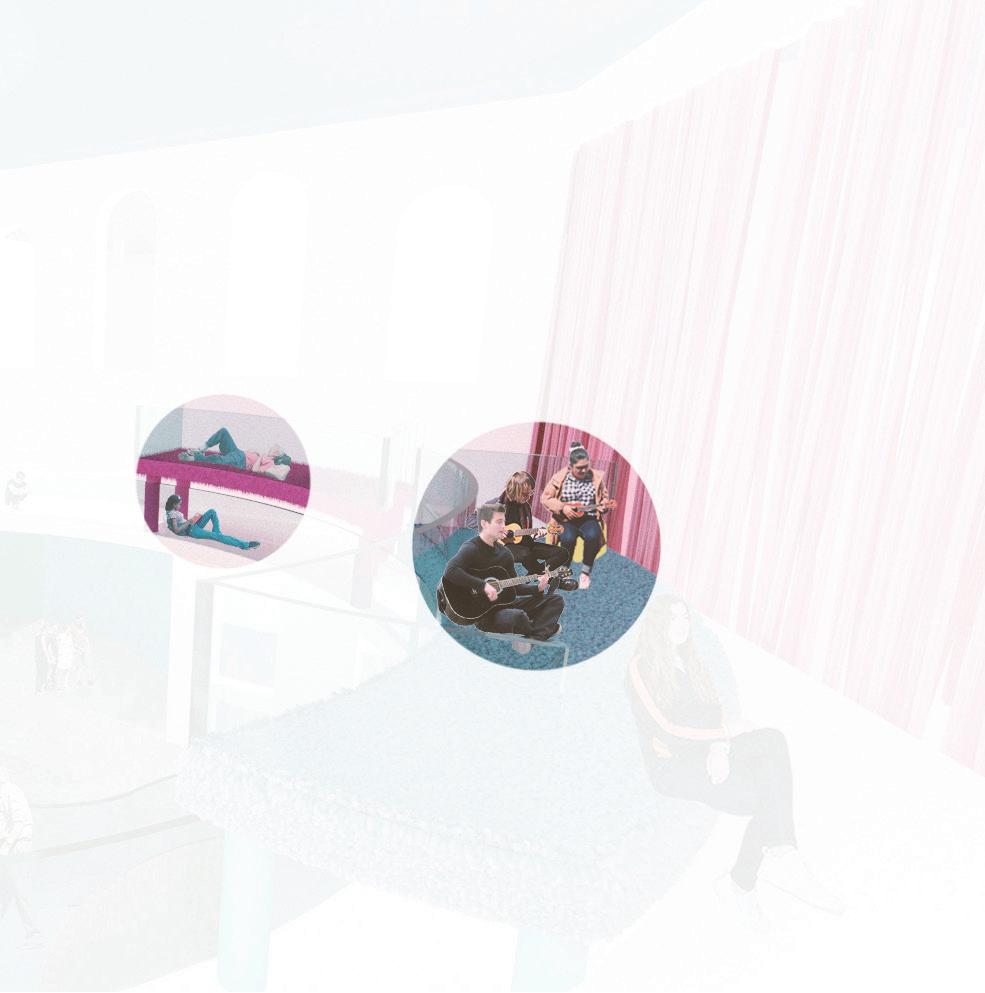

In the former convent, the rooms were small and the hallways were tight. Visibility through the building was limited. The new space creates more flexible conditions by applying vaulted textured ceilings that control acoustics, multiple levels of usable space, meandering pathways, variety of sizes of space, fuzzy perimeter.

1,2: Varying levels of platforms create opportunities for users to customize the space with things like plants. They also create a feeling of intimacy and a lower stimulation enviroment in some spots while creating a grander, higher stimulation environment in other spots.

3: The path of circulation meanders through the space, increasing the

possibility of a chance encounter. It creates moments of constriction and release, qualities which prompt various uses of the spaces surrounding the path.

The space above each residential module is separated from the module below by a netting. The netting’s qualities are as follows: breathable, a “transparent” surface, weight-bearing. This “attic space” is partially enclosed by a domed ceiling. The domed ceiling’s qualities are as follows: porous, provides acoustic control, climbable, pinnable, adaptable.

1: Patches of “grass” provide comfortable, lower-stimulation spots to rest. These are covered by domes whose walls curve at an ideal angle for pinning up drawings, papers, decorations, etc.

2: The domes are perforated and allow users to climb them.

3: Netting provides a flexible and comfortable surface that provide stimulation for users who need to expend energy.

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): The Basics. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd-the-basics/index.shtml

Autism Spectrum Disorder. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/ topics/autism-spectrum-disorders-asd/index.shtml

Brand, S. (1994). How buildings learn: and fail to learn. New York, NY: Viking.

Hartmann, T. (2005). The Edison gene: Adhd and the gift of the hunter child. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press.

Jones, P. B., Petrescu, D., & Till, J. (2009). Architecture and participation. London: Taylor & Francis.

Penny Spikins Senior Lecturer in the Archaeology of Human Origins. (2020, March 3). How our autistic ancestors played an important role in human evolution. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/how-our-autistic-ancestors-played-an-importantrole-in-human-evolution-73477

Rosa, S. D. R. (2011). Thinking persons guide to autism. Redwood City, CA: Deadwood City Pub.

Thompson-Schill, S. L., Ramscar, M., & Chrysikou, E. G. (2009). Cognition without control: When a little frontal lobe goes a long way. Current directions in psychological science, 18(5), 259–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01648.x