THE IMPACT OF 124 YEARS OF LEGACY

MEET THE MINDS FROM THEORY TO IMPACT BRAINS ov ER B o RDERS FOR THE BENEFIT OF MANKIND KELLERMAN

INTRODUCING THE FUTURE TODAY

We are proud to be the first hospitality company to launch Verified Net Zero hotels. Through third-party verification and alignment with the Net Zero Methodology for Hotels, we’re turning ambition into action.

This is what the future of hospitality looks like. Powered by 100% renewable energy, fuelled by low-carbon cuisine, and driven by minimum waste principles, our Verified Net Zero hotels are setting a new benchmark for sustainable stays.

Discover the future of sustainable travel with our first openings in Manchester and Oslo.

MANCHESTER CITY CENTRE, A VERIFIED NET ZERO HOTEL

OSLO CITY CENTER, A VERIFIED NET ZERO HOTEL

Photo: Ola Ericson,

Stockholm Where tradition meets transformation

The brightest minds in the world meet in Stockholm. Every December, the Nobel Prize Awards light up the City Hall, celebrating innovation and discovery. But the influx of ideas doesn’t end there. Stockholm is rapidly becoming Europe’s go-to destination for creative meetings, conferences and congresses – a city where innovation thrives year-round. Compact yet cosmopolitan, Stockholm offers modern venues, excellent accommodation, breathtaking surroundings and a buzzing social scene. Add efficient public transport and a strong commitment to sustainability, and it’s easy to see why Stockholm is the perfect place to meet, connect and create.

Imagine an Unbelievable event in the Faroe Islands

Meet the Faroe Islands at IBTM Stand H33

Unordinary ideas arrive in

A Nation of Ideas A DESTINATION FOR

INSPIRATION

In Poland, ambition fuels discovery, and hard work turns dreams into history.

From Maria Skłodowska – Curie’s revolutionary breakthroughs in physics and chemistry to the Nobel-winning words of Henryk Sienkiewicz, Władysław Reymont, Czesław Miłosz, Wisława Szymborska, and Olga Tokarczuk – and the fearless fight for freedom led by Lech Wałęsa – this is a nation where ideas evolve into inspiration, and inspiration into impact.

Bring your next meeting to a place that inspires progress.

Foto:

Jakub Krawczyk

Ambassadors of Polish Congresses THE PEOPLE BEHIND GLOBAL MEETINGS SUCCESS

The Polish Congress Ambassadors Program recognises leaders who bring international events to Poland — experts, scientists, and visionaries whose work strengthens the country’s position on the global meetings map.

Through their commitment and creativity, Poland becomes a meeting point for the world’s brightest minds.

SCANDINAVIAS LARGEST EXPO FOR PLANNERS AND BUYERS OF MEETINGS & EVENTS

Copenhagen

A City of Nobel Minds and Global Conventions

With 14 Nobel Prize laureates to its name, 13 of them connected to Copenhagen University, Denmark ranks among the top 20 most successful countries in Nobel history. Many of these laureates have lived, worked, or studied in Copenhagen. The city’s identity as a hub for knowledge, intellectual exchange, and international collaboration is most clearly seen through Denmark’s Nobel Prizes. These honours reflect not only individual achievement but also a thriving academic and cultural ecosystem, supporting innovation and progress.

Where Nobel ideas meet global challenges

Copenhagen, as the capital, acts as both a stage and a catalyst; a city where intellectual capital thrives and cross-disciplinary ideas converge to create innovations with a global reach. From Niels Bohr’s revolutionary work in quantum physics to Henrik Pontoppidan’s literary contributions, Copenhagen has nurtured Nobel minds whose ideas have shaped the world. But beyond being a birthplace of brilliance, the city has also served as a meeting ground for the global exchange of knowledge.

Or consider August Krogh, Nobel laureate in Medicine (1920), whose research on capillary regulation revolutionised our understanding of oxygen transport. After his Nobel win, Krogh toured North America, lecturing at universities and engaging with peers. His visit to the University of Toronto led to the founding of what would become Novo Nordisk, a global pharmaceutical leader headquartered in Greater Copenhagen.

Professor Morten Meldal, recipient of the 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on click chemistry, is a prime example of this dynamic. Based at the University of Copenhagen, Meldal’s

research has not only advanced molecular science but also inspired new formats for academic exchange. His work has been presented at international congresses hosted in Copenhagen, where the city’s infrastructure and intellectual climate support highlevel dialogue.

Every year, Nobel Prize-winning research inspires more than 100 international meetings, symposia, and congresses. These gatherings are not just celebrations of achievement, but incubators of future breakthroughs. As Swedish historian Gustav Källstrand, author of Think Like a Nobel Prize Winner, notes: “Being part of conventions could be an important way to one day become a Nobel Prize winner.”

A Nobel tradition rooted in collaboration

Copenhagen’s congress infrastructure, from its world-class venues to its commitment to sustainability and legacy, makes it an ideal host for such transformative events. The city’s convention culture is deeply rooted in the values of the Enlightenment: open dialogue and the pursuit of groundbreaking ideas. And in recent years, Copenhagen has embraced the concept of legacy beyond the event. Scientific congresses held in the city often leave lasting impacts, from public engagement initiatives to long-term research collaborations. This aligns with the spirit of the Nobel Prize itself: a legacy that endures for generations.

As the world faces complex challenges, now is the time to harness the power of congresses to foster interdisciplinary collaboration and global understanding. Denmark’s Nobel tradition spans diverse fields, from physics and chemistry to medicine, literature, and peace, underscoring the truth that innovation is not confined to a single discipline. Copenhagen mirrors this breadth. While life

sciences remain a core strength, the city’s academic events and conferences draw thought leaders from economics, environmental studies, engineering, and the humanities. This mix sparks collaborations that might never occur without people physically gathering, exchanging insights over coffee, or debating late into the evening at symposia. Here, the concept of ‘innovation’ becomes tangible. Breakthroughs are born from conversation, and those conversations need both the right minds and the right meeting environment.

The Nobel connection reinforces Copenhagen’s value proposition to the global academic and business events community. Each prize is rooted in years of shared inquiry, often spanning institutions and nations, and many of those relationships have been strengthened through physical meetings hosted here. The city’s infrastructure – including purpose-built conference venues, historic university halls, sustainable transportation, and human-scale urban design – supports the seamless flow of ideas. Copenhagen is probably also one of the foremost cities when it comes to legacy, both with its internationally renowned Legacy Lab, and how they work strategically with congresses to ensure they generate positive societal change.

The power of physical meetings

Hosting an event in Copenhagen is not just about logistics; it’s about embedding participants in an environment where intellectual curiosity is the currency, and mutual respect is the shared language. Academic events here benefit from Denmark’s strong tradition in education and research funding, which feeds a pipeline of world-class experts and young innovators. These events do

more than showcase theory – they activate networks. Delegates leave with new partnerships and projects, often inspired by Copenhagen’s openness to interdisciplinary connections. Much like the Nobel laureates’ work, these collaborations ripple outward, influencing global challenges from climate change to public health. Copenhagen’s narrative, framed by its Nobel achievements, is a testament to the power of physical meetings as catalysts for innovation. The city understands that while digital tools can connect minds across continents, there is an irreplaceable value in gathering under one roof. The handshake, the live debate, the shared laughter during a social event – these moments build trust, spark creativity, and sometimes plant the seeds of a Nobel-worthy idea.

A city that hosts the future

To host a congress in Copenhagen is to embed it in a tradition of excellence. It’s a city where Nobel minds have walked, debated, and discovered. Where the past informs the present, and the present shapes the future. For event organisers, the city offers more than prestige, it offers the opportunity to create meaningful impact. In Copenhagen, meetings matter. Make yours one that counts. Bring your event to a city where the right minds meet in the right place, and together, you just might change the world.

For more information, scan the code to visit www.copenhagencvb.com

Flowing Toward New Horizons Sarawak’s Strategic Rise Through Purpose-Driven Events

Like the river that defines its capital city, Sarawak is charting a steady and confident course toward a new future, one that embraces sustainability, innovation, and knowledgedriven growth. Positioned along the banks of the Sarawak River, the Borneo Convention Centre Kuching (BCCK) has become a catalyst in this journey, serving not only as a venue but as a strategic platform for business events that advance the region’s long-term aspirations.

In today’s global landscape, business events are no longer measured solely by delegate numbers or spectacle. Increasingly, governments, associations, and industry leaders are prioritising outcomes: knowledge transfer, talent development, policy alignment, investment and trade opportunities, and social impact. This shift aligns seamlessly with Sarawak’s Post-Covid Development Strategy 2030 (PCDS 2030), which emphasises key priorities such as renewable energy, bioeconomy, medical sciences, advanced agriculture, and sustainable tourism. Business events held in Sarawak are therefore not just hosted, they are woven into a larger developmental narrative.

“Business events play a pivotal role in shaping economies and communities,” says Rayner Simon, Chief Operating Officer of BCCK. “Our vision is to support conferences that bring vision, drive collaboration, and create lasting impact for Sarawak and the wider region.”

Managed by the Sarawak Economic Development Corporation (SEDC), BCCK has earned its reputation as a trusted host for international and regional meetings. Upcoming programmes across strategic sectors, including the 23rd World Veterinary Poultry Association Congress 2025, Asia Pacific Green Hydrogen Conference 2026, World Polymer Congress 2026, and Asia Conference on Occupational Health 2026, among others, which reflect the confidence global organisers are placing in Sarawak’s direction. This sector led approach demonstrates both capability and intent, the ability to deliver high level events, and the commitment to align them with long term state priorities.

The centre’s riverfront setting, supported by warm hospitality and accessible infrastructure, provides an environment where dialogue can flow naturally and ideas can deepen without distraction. At the same time, Sarawak’s unique blend of Bornean culture,

rainforest heritage, and modern aspirations offers delegates a sense of place, something memorable, grounded, and authentic.

As Sarawak prepares for its next chapter, BCCK2 is set to elevate the state’s position in the Asia Pacific business events arena. Designed as a future-ready expansion to the existing centre, BCCK2 will offer larger configurations, advanced technology, enhanced sustainability features, and greater flexibility for rotating international conferences of up to 10,000 delegates, along with 34 versatile breakout rooms, a spacious concourse area, and a multi-purpose hall. When completed in Q1 2028, the combined capacity will allow Sarawak to host multiple sizeable programmes simultaneously, strengthening its competitive edge and expanding its reach.

Yet, the foundation of progress is partnership. Sarawak’s strength lies in the close collaboration between government, industry, academia, and community stakeholders, creating an ecosystem that supports everything from bid development to legacy planning. This collective spirit ensures that international events held in Kuching do not end when the closing ceremony concludes, but continue creating value through knowledge exchange, research pathways, and community engagement.

BCCK extends its sincere appreciation to the Sarawak Government, Business Events Sarawak (BESarawak), the Ministry of Tourism, Creative Industry & Performing Arts Sarawak (MTCP), the Malaysia Convention & Exhibition Bureau, industry partners, and the wider business events community. Their trust, alignment, and shared purpose make it possible for Sarawak to advance confidently toward a stronger, smarter, and more sustainable future.

For organisers seeking a destination where ideas can take root and progress can be shaped, Kuching offers a clear proposition. Here, business events are not just hosted, they help build the future.

For more information, scan the code to visit bcck.com.my

Prague Congress Centre A Unique Convergence of History, Innovation and Prestige

Prague has long been one of the world’s top MICE destinations, and the Prague Congress Centre (PCC) is its key pillar. It has hosted a number of prestigious events, including the recent 22nd World Congress in Fetal Medicine, which brought 3,000 experts from more than 100 countries to the Czech capital. We spoke with Roman Sovják, Sales and Marketing Director of the Prague Congress Centre, about why Prague and the PCC are among the best in the industry, how they differ from the competition, and what global trends are shaping the MICE industry.

Prague is one of the five most sought-after MICE destinations in the world and has long been the leader in Europe. How does it maintain this position?

The Prague Congress Centre recently hosted the ICCA European Venues Workshop. What did the format reveal about Prague and the PCC?

The extraordinary interest in Prague is due to a unique combination of safety, easy accessibility and a unique historical and cultural environment. It offers a plethora of monuments, many of which are listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. It has top-notch infrastructure – from modern congress centres and high-quality hotels to reliable public transport. This creates an environment that guarantees an exceptional delegate experience, which international event organisers have long valued.

Thanks to the workshop, European congress centre representatives and associations with the potential to bring major international events to us gathered in Prague. In addition to the opportunity to address future customers directly on home turf, we also had a unique opportunity to share our best experiences with each other. For us, the ICCA Workshop also represented an opportunity to gain useful know-how from competing congress centres. And we are, of course, delighted that during the B2B meetings and the ‘Partnering for Success’ forum, the participants appreciated not only the facilities and services, but also the experiences that are an integral part of Prague – from a walk through medieval Vyšehrad to a gala evening at the Old Town Hall. Although convention centres that normally compete for the same customers met here, the atmosphere was extraordinarily friendly. In my opinion, this perfectly captures the openness and meaningful cooperation that are driving the MICE industry forward.

Prague has the ambition to increase the number of congresses by 30 per cent by 2030. How is it

coping with the growing demands of international competition?

In addition to its strong congress infrastructure, it also systematically invests in modernisation and new projects. One of these will be the new exhibition hall at the Prague Congress Centre. This should increase our capacity by 5,000 m² of exhibition space and enable us to host even the largest global events, for which the existing premises are insufficient. The planned direct connection from the airport to the city centre and the expansion of event spaces will also be key. At the same time, Prague offers something that is difficult to replicate – a unique location in the heart of Europe and an exceptional atmosphere that remains in the guests ‘memory.’ The same goes for the panoramic views of the historic centre from the PCC premises, complemented by our many years of experience and ability to provide top-quality services.

Growing competition is placing high demands on local conference centres. How are you responding to this?

Our greatest advantage is 45 years of experience, which we are happy to share with other centres and enrich each other with best practices. We have a professional team that can respond flexibly to client needs and unforeseen situations. We offer flexibility for events with a capacity of up to 10,000 participants, top-notch security and a great location right next to the metro, with a view of the Prague Castle. Part of our identity is also our connection to art. The designer interiors feature works by famous artists. This unique backdrop gives our events a distinctive character and sets us apart from most of our European competitors. We provide our clients with comprehensive support and keep up with constantly changing trends, from technology and AV to ESG support. I believe that this makes us not just a venue for our clients, but a true partner. And references from events such as the Czech Presidency of the Council of the EU in the second half of the year 2022 and the IMF/ World Bank Meetings or the NATO summit confirm that we score highly even with the most demanding clients.

system on the roof of the building and switched to purchasing green energy. We are continuing to invest this year: more economical escalators with ionisation technology increase hygiene standards, while drinking fountains save plastic. In addition, we adhere to zero waste principles – digitisation instead of printing, waste sorting, local catering with seasonal ingredients, and so on. Every year, we strive to enable our clients to organise events with the least possible impact on the environment. To this end, they will also have a new GM mobile app available that will allow them to measure the carbon footprint of events organised in Prague.

What global trends do you think are shaping the MICE sector the most, and how is the PCC responding to them?

Events are no longer just business, but experiential and interactive formats that leave a mark, whether in the form of new partnerships and friendships or a positive impact on infrastructure and the local community. The emphasis on the authenticity of local markets and diversification of offerings is also key. You must be prepared to address different generations of clients with different needs – from IT, through the tech sector to science. Some expect wellbeing zones and flexible spaces, while others emphasise cutting-edge digital facilities. Technology plays a big role – the right software, data, and analytics increase the efficiency and value of events. Logically, AI is also coming to the fore. Here, it is necessary not only to keep pace, but also to maintain caution and security. The global MICE market is set to more than double in volume by 2032, so it is necessary to develop, ideally to play the role of a trendsetter, which we are succeeding in doing in areas such as sustainability and artistic value.

If you had to invite event organisers to Prague and the Prague Congress Centre in one sentence, what would it be?

Prague offers unique experiences, and we are its congress icon, where meetings become moments that really matter – come and see for yourself.

Sustainability is an essential standard today. What is your stance on it?

We see sustainability as a long-term commitment, not a marketing label. Since 2016, we have been reducing our energy consumption thanks to an EPC project, and we have saved hundreds of millions of CZK on energy and reduced CO² emissions by tens of thousands of tonnes. We have started measuring the carbon footprint of the Prague Congress Centre, installed a 7,000 m² photovoltaic

For a closer look at the atmosphere and possibilities of the Prague Congress Centre, scan the code to watch a video.

Prague Congress

C e n t r e exterior bynight.

23 Without Congresses, No Nobel Prizes INTRO Atti Soenarso on how a vast Nobel Prize ecosystem is reminding the world that brilliance rarely blooms in solitude.

24 Think Like a Nobel Laureate IDEAS THAT CHANGE THE WORLD Nobel historian Gustav Källstrand explores what connects the great minds of Nobel laureates.

36 Unlocking the Nobel Mindset: How o penness to Change Unites Laureates’ Ideas EMBRACE CHANGE The concept of change is a fundamental part of the sciences, but extends far beyond, into every aspect of daily life.

42 The Last Will: The Legacy of Alfred Nobel LEGACY From dynamite to philanthropy, Nobel’s bold testament challenged expectations and created a new standard for excellence.

46 The Nobel Foundation Stewards and Promotes Alfred Nobel’s Legacy LONG-TERM STRATEGY Preserving Nobel’s vision, the Foundation manages assets and events to inspire generations to strive for excellence.

52 Selecting the Nobel Prize Laureates Based on Principles From 1897–1900 NOMINATION PROCESS Thousands of nominated candidates are painstakingly assessed annually, before a majority vote finalises laureates.

60 o utreach Programmes Drive Nobel’s Scientific and Cultural Legacy

THE NOBEL E v ENTS ECOSYSTEM The Nobel Prize drives knowledge exchange and global engagement through hundreds of meetings annually.

70 The Nobel Day, December 10: A Celebration of Science, Literature and Peace

CELEBRATION DAY On December 10, the world unites to award those outstanding individuals who have most benefitted human progress.

80 The Nobel Banquet: Climate-Smart Gastronomy Supporting Sustainability

FOOD WASTE STRATEGY The Nobel Banquet celebrates zero-waste dining, showcasing inspiring Swedish ecofriendly gourmet innovation.

90 Down the Line of Innovative Thinking the Future Awaits

SLOW FUTURISM Scott Steinberg on how today’s most preeminent scholars and achievers pave the way for a brighter tomorrow.

94 Unleashing Intellectual Capital for Human Progress

KELLERMAN Roger Kellerman on transformative exchanges inspiring excellence in both sciences and event hosting.

LEGALLY RESPONSIBLE EDITOR IN CHIEF Atti Soenarso atti.soenarso@meetingsinternational.com

PUBLISHER Roger Kellerman roger.kellerman@meetingsinternational.com

GLOBAL SALES DIRECTOR Graham Jones graham.jones@meetingsinternational.com

TEXT Roger Kellerman, Atti Soenarso, Scott Steinberg

PHOTOS / IMAGES Front cover artwork based on a photo by by Atelier Florman © Nobel Foundation, Nanaka Adachi, Sara Appelgren, Niklas Elmehed, Pi Frisk, Dan Lepp, Magnus Malmberg, Clément Morin, Torben Nuding, Ken Opprann, Mark Strozier, Anna Svanberg, Vertigo, Jannis Werner

DESIGN KellermanDesign.com

EDITORIAL RAYS OF SUNSHINE Dr Jane Goodall + The Faroe Islands + Alfred Nobel + Robert Redford + Bettina Rewentlow-Mourier + Mare Nostrum Trio

SUBSCRIPTION Subscribe at www.meetingsinternational.com or subscription@meetingsinternational.com

CONTACT Meetings International Publishing Formgatan 30, SE-216 45 Limhamn, Sweden info@meetingsinternational.com www.meetingsinternational.com

PRINTING Exakta Print AB, Malmö 2025 [environmentally certified, ISO 14001]

PAPER Arctic Paper Munken Pure 100 g + 240 g FSC labeled paper Cert No SGS-COC-1693 ISSN 1651- 9663

Facebook @MeetingsIntCom

Same Great Location, Better Than Ever.

The upgraded Hynes Convention Center is here for your next win.

In Boston, our rich tradition is powered by forward thinking, which means big things for your next meeting. The John B. Hynes Veterans Memorial Convention Center is undergoing a $100 million renovation and is open for bookings now and far into the future. This flexible meeting space is refreshed with significant infrastructure improvements, more cutting-edge technology, and enhanced comforts throughout the building, all backed by award-winning services to help bring your vision to life.

Come visit and see what’s new!

Schedule a site visit and make history with your own event. Call 877-393-3393 or visit SignatureBoston.com

BA R CEL ONA, SPAIN

Without Congresses, N o N o BEL PRIZES

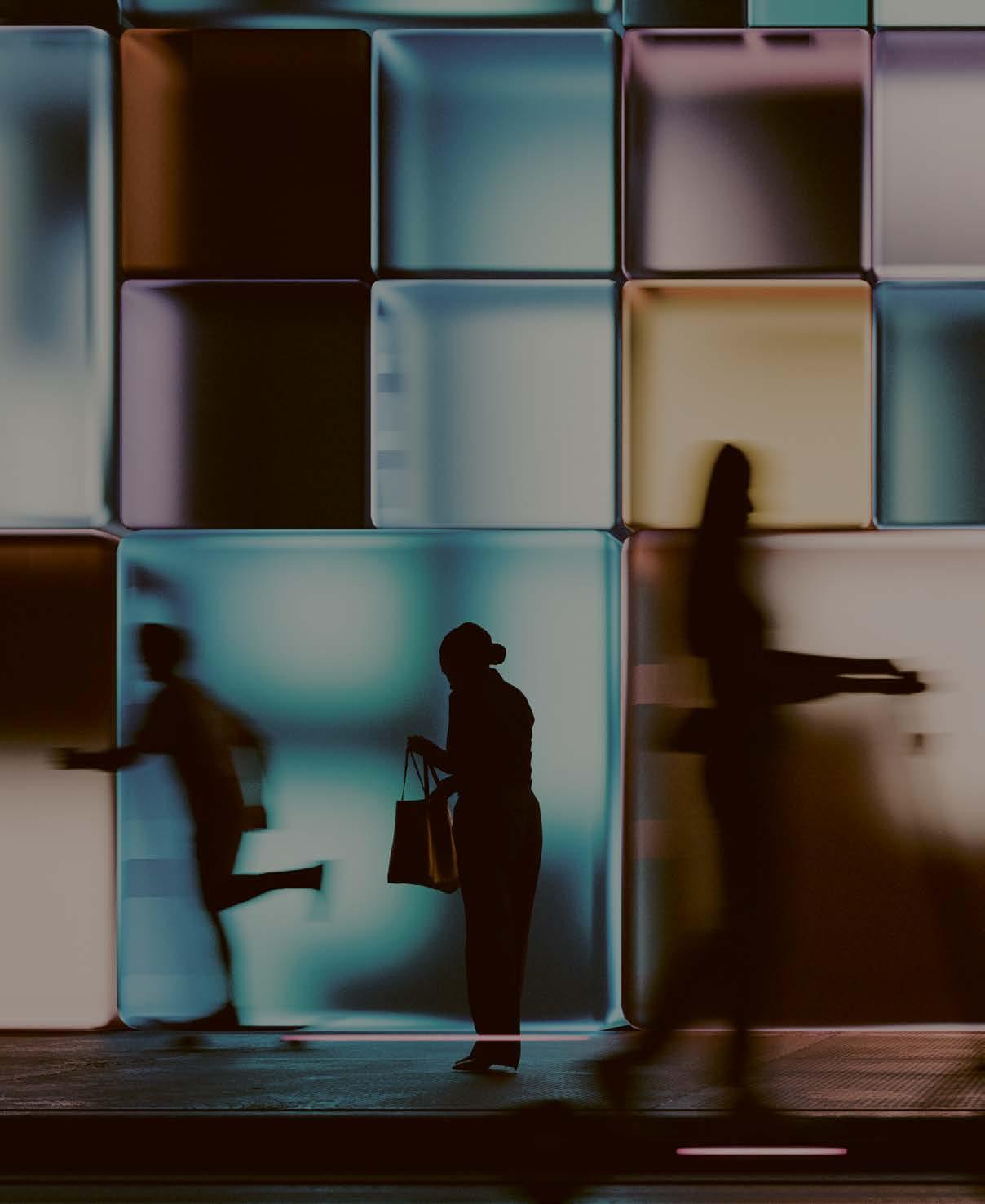

Every December, the Nobel Prize award ceremonies in Stockholm, Sweden, and oslo, Norway, remind the world that brilliance rarely blooms in solitude. Behind every breakthrough in Physiology or Medicine, Chemistry, Physics, Economic Sciences, Literature, and Peace, lies not just genius but conversation, debate, and collaboration. Without meetings, there would be no Nobel Prizes.

Behind the glittering ceremonies lies a vast Nobel Prize ecosystem, encompassing a network of hundreds of meetings annually that blend recurring laureate gatherings, scientific conferences, committee sessions, educational summits, formal award events, and public outreach programmes at the global and local levels.

The story of discovery is, at its heart, the story of dialogue. Congresses, for example, create fertile ground for that dialogue. They turn ideas into action by forcing researchers to explain, defend, and refine their work. A paper read in a vacuum might go unnoticed, and a presentation delivered before peers could spark a revolution. Every handshake at a poster session, every heated debate after a keynote, every late-night exchange over coffee or beer can be moments when science evolves.

The structure of the prize categories shows the breadth of Alfred Nobel’s thinking. Each category reflects a facet of human advancement, and he understood that a more peaceful and prosperous world required breakthroughs not only in science but also in literature and political effort.

Consider the so-called Nobel Minds: the laureates who gather each year in Stockholm for an open discussion about discovery and determination. They talk less about eureka moments and more about grit, the daily discipline that keeps ideas alive long enough to matter. Moreover, great ideas need friction. They need the hum of a crowded auditorium and the energy of disagreement. They need people in the same room, sharing not only data but doubt. Congresses serve as testing grounds, where fragile hypotheses meet the world, where bold claims face friendly fire, and where collaboration replaces competition.

When the Nobel committees announce their choices each year, they honour not only individuals but networks: the mentors, colleagues, and critics who shaped the work. Behind every medal stands a conference badge, a shared table, a

conversation that might have lasted only minutes but changed everything. Virtual platforms have made research more accessible, but something vital gets lost in the translation: serendipity. The unplanned encounter in a hallway, the overheard conversation that sparks a new question, cannot be scheduled in a Zoom breakout room.

Peace, the most collective of all Nobel categories, exists only through meeting. Diplomacy is a long meeting, spanning borders and decades, built on compromise, conversation, and courage. The grit to keep showing up, to listen when listening feels impossible, defines peace-making more than any treaty ever could.

When the laureates gather for the Nobel Banquet, the symbolism is clear: minds sitting together, ideas in conversation, achievements shared. The world celebrates their discoveries, but the true victory lies in their persistence in meeting, in continuing their research, even through frustration, doubt, and failure.

Beyond the ceremonies, the Nobel Prize ecosystem of meetings continues to evolve, ensuring that Alfred Nobel’s legacy keeps pace with the times.

Swedish-Indonesian Atti Soenarso has worked as a journalist for over 40 years. She has worked for Scandinavia’s largest daily newspaper, was TV4’s first travel editor, has written for many Swedish travel magazines and has had several international clients. She has travelled the length and breadth of the world and written about destinations, people and meetings.

PH o T o Magnus Malmberg

GKÄLLSTRAND

TEXT

Atti Soenarso

Sara Appelgren PHOTOS

Gustav Källstrand is a researcher, historian of ideas, author, and one of the world’s leading experts on the Nobel Prize. His doctoral thesis on its history was published in 2012 . Since then, he has worked at the Nobel Prize Museum in Stockholm, conducting research, writing, lecturing, and interviewing laureates. He is also an expert commentator for Swedish Television’s annual live broadcast of the Nobel Prize ceremony, and has appeared on Nobel Studio as well as in several international media outlets.

For many years, he has hosted the Nobel Prize Museum’s podcast Ideas that Change the World, which explores the laureates, their discoveries, and their impact on how we live and think. Gustav Källstrand’s book Think Like a Nobel Laureate was published in Swedish last year and has not yet been translated into other languages.

When people discuss science, they often focus on its practical applications. Gustav Källstrand also emphasises that science is an integral part of our culture and can be appreciated much like literature or art: “It is enriching and rewarding to learn more about evolution, the Big Bang, the butterfly effect, mutants,

and much more. There is an incredible world to discover if you, like the Nobel Prize winners, dare to see the world as a place you do not yet fully understand.”

According to the Nobel historian, several characteristics unite many prize winners. Alongside deep knowledge, they share curiosity, perseverance, and courage: “What they have in common is that they have achieved something groundbreaking – and to do that, you must be willing to think in new ways. You need to accept that things do not have to be as they are, or as everyone believes them to be. It begins with being open to the idea that what you think you know is not necessarily true.”

“ There is an incredible world to discover if you dare to see the world as a place you do not yet fully understand”

Gustav Källstrand says that working with the Nobel Prize allows him to spend time in a world full of creative people with big ideas: “It is incredibly inspiring and enlightening. I’ve realised that my world grows and expands the more I understand these ideas. And what’s remarkable is that all these stories and ideas are available to everyone.”

Change is a central theme in the book, reflecting the Nobel laureates’ approach to progress and discovery. Gustav Källstrand explains that making discoveries means transforming how we understand the world. Researchers who uncover something new often overturn established ideas in the process, and that requires a mindset grounded in the belief that what we know today is not the ultimate truth. Sometimes, what we consider true now may later prove false.

“There is a kind of scepticism built into science, and it’s shared by Nobel Prize winners and all good researchers. It’s a form of constructive scepticism, grounded in the belief that it’s not only possible to question old explanations but also to create new and better ones.

“This way of looking at change means that, just as what we know can change, we can use that knowledge to drive change – helping us become better at developing the world. For individual laureates, it often involves maintaining an open attitude towards the constant evolution of knowledge and recognising that science, like the world itself, is in perpetual transformation. The goal is not to preserve the status quo, but to advance it in the right direction.”

The first chapter of the book opens with American scientist Frances Arnold, the 2018 Chemistry laureate, whose research focuses on harnessing evolution to develop new chemicals, applying natural processes of change for beneficial purposes. She has pursued a path of her own, achieving remarkable success while also confronting professional and personal setbacks. Yet she maintains an unshakable faith in both humanity’s and her own capacity to adapt, evolve, and change the world. Her story teaches us to reflect on how we come to be what we become.

“It’s fascinating to hear her talk about her work in the laboratory and

“The goal is not to preserve the status quo , but to advance it in the right direction”

about the community and collaboration at the heart of science. You can tell she has great integrity and wastes no time on anything she considers unimportant. That could be offputting to some, but because Frances Arnold is such a generous and warm person, it instead inspires you to do your very best.”

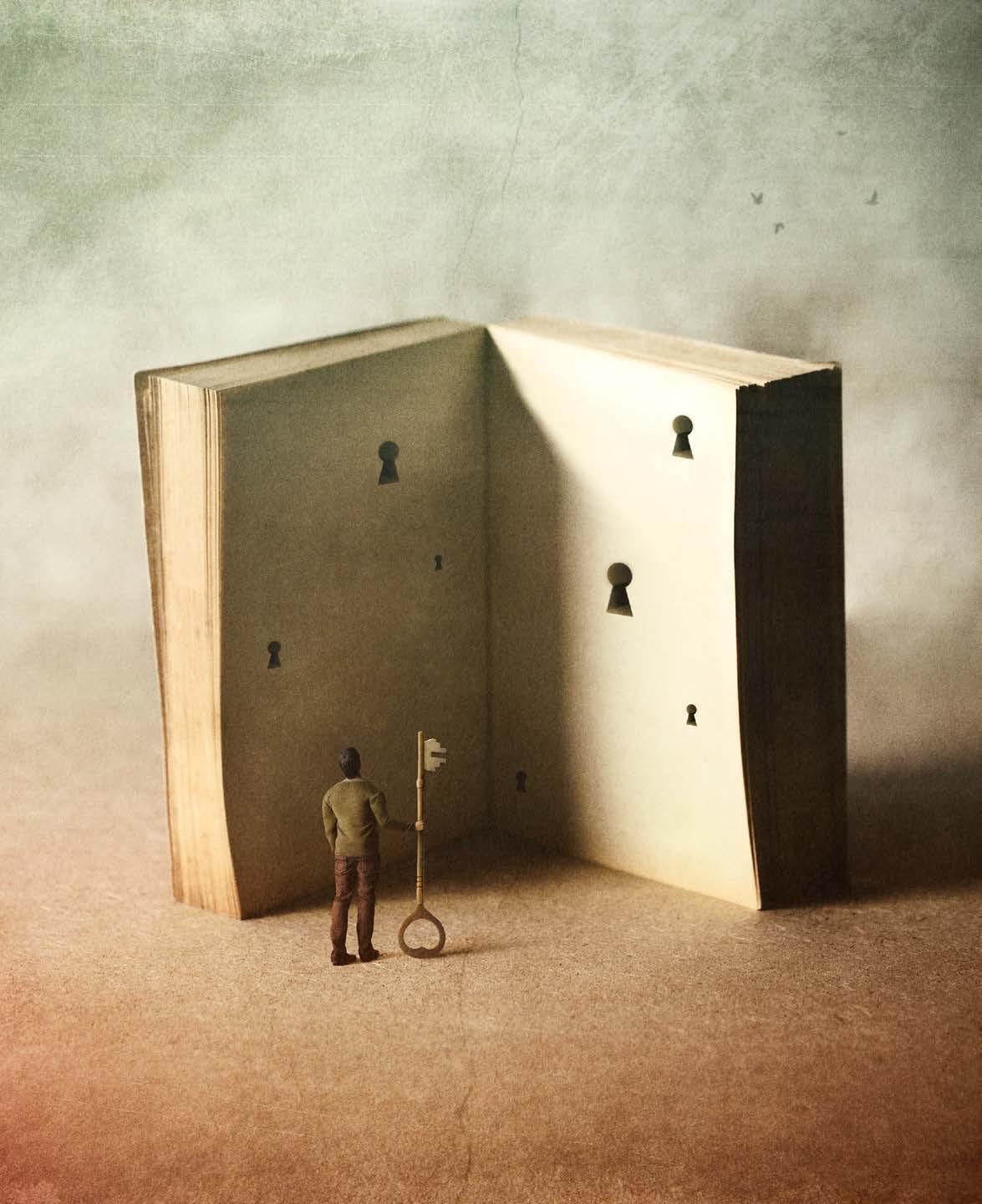

In several passages in the book, Gustav Källstrand highlights a central theme: many Nobel Prize winners have founded or participated in congresses and conferences. Building and developing networks, acquiring new knowledge, and meeting other researchers both within and beyond one’s own field are all vital to scientific progress. We discuss the value of the informal encounters that happen in the margins of such events: during coffee breaks, between sessions, or even on the shuttle bus to the conference centre, where strangers strike up conversations and discover shared interests that spark new insights and collaborations.

To claim that Nobel Prize winners are somehow “special” is to oversimplify; they possess different qualities, just like everyone else. Gustav

Källstrand points to two laureates with contrasting approaches to their work. one is the American geneticist Barbara McClintock, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1983 . It reportedly took the Nobel Committee three days to reach her with the news, as she preferred working alone, free from interruptions, and had no telephone in her laboratory. The other is Ernest Lawrence, also American, who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for inventing the modern particle accelerator. In contrast, his achievements rested largely on collaboration – with other researchers, industry leaders, politicians, and funders. Particle accelerators are more powerful the larger they can be made, which in turn demanded collective efforts to secure the necessary resources.

“There are many different approaches to achieving success. Some researchers may work diligently, alone or in small groups, on problems whose importance may not be on everyone’s radar, while others thrive through collaboration and working in the public eye. Yet for both, it is essential not only that

IDEAS THAT CHANGE

others know what they are doing, but that they in turn know what others are doing. one of the great strengths of science is that it offers conferences and meetings where even independent researchers can come together and engage in person; and that you don’t have to be particularly outgoing, because events like these have clear rules for presentations and discussions.”

Gustav Källstrand notes that congresses and conferences have played a key role in science for as long as modern science has existed, or at least since the late 19 th century. A hundred years ago, travel was not as easy as it is today, but it was far easier than it had been half a century earlier. The advent of trains and steamships made it possible for people to travel with relative ease. It was still expen-

“ It begins with being open to the idea that what you think you know is not necessarily true”

Gustav Källstrand goes on to say that most researchers fall somewhere on a spectrum between the extremes of Barbara McClintock and Ernest Lawrence. For introverted individuals, conferences can be invaluable in helping them progress and make contacts – which also benefits extroverted researchers who might not otherwise get to meet individuals from the former group.

“one should not underestimate the importance of conferences in developing a community. It can include, for example, learning how to convey one’s message and relate to frames of reference and norms –what is sometimes referred to as tacit knowledge. When attending a conference or congress, it quickly becomes apparent which individuals are accustomed to the context and which are more tentative. In addition, you learn how to behave so that your own research has a better chance of reaching a wider audience.”

sive, though attending a conference and meeting leading researchers in one’s field could ultimately save both time and money. At that time, obtaining the latest publications and scientific findings was often costly and complicated, whereas at a conference you could efficiently update your knowledge and establish contacts that enabled direct correspondence with colleagues.

“The research world was also much smaller back then. In 1900, there were approximately 1 ,000 professional physicists worldwide and around 3 ,000 chemists. So if you attended a conference in your own field of research, you would probably meet most of the researchers in that field. This made it worthwhile to attend a conference, even if it meant spending a few nights in a sleeper carriage on the train.”

one of the most important lessons you learn at a scientific conference is that the vital moments do not always

take place during the presentations, but during coffee breaks, lunches and dinners – or when you skip a seminar to take a walk with someone who seems to have interesting ideas.

Gustav Källstrand explains that this is how researchers Emmanuelle Charpentier, from France, and Jennifer Doudna, from the United States, first met at a conference in Costa Rica. They left the hotel to have lunch and discuss their shared interest in the bacterial immune system, and specifically the use of CRISPR As Emmanuelle Charpentier was based in Umeå, Sweden, and Jennifer Doudna in Los Angeles, the likelihood of their having a few hours together would otherwise have been relatively small.

The lunch meeting marked the beginning of a collaboration that was carried out mainly through digital meetings. The fact that the researchers worked in different time zones proved advantageous, as one research group could work during the day and report its progress, while the other continued overnight. Within a few years, the teams had developed CRISPR into a new and revolutionary method for editing DNA. The discovery led to Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna being awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020.

Gustav Källstrand believes that it is beneficial that much of the scientific exchange can now be conducted remotely, as it makes science more democratic by allowing even researchers who cannot afford to travel to share in new findings. But there are limitations: “The new connections and personal contact are crucial, and you get that when you meet in person. When I interviewed Jennifer Doudna about her and Emmanuelle Charpentier’s work, she emphasised how important it is

“One of the most important tricks you learn at a scientific conference is that the important stuff may happen during breaks”

to be able to trust one another when working together, and that such trust is difficult to create digitally.

“Physical participation in conferences and other scientific meetings is as important as ever. I also believe that all other means of communication make it easier to maintain networks, while in-person meetings remain central to creating them in the first place. Moreover, we need to take a more nuanced view of the new forms of communication. They have great advantages, but I think it is largely a question of increased accessibility for people who might otherwise have difficulty participating.”

When it comes to building networks, researchers have been doing so since at least the 17th century –partly through physical meetings and partly through written correspondence. In the 1920 s, for example, when digital meetings were of course not an option, ideas were exchanged through long and carefully composed letters in which many scientific questions were discussed and sometimes even resolved. When Swedish researchers corresponded with one another in the 1920 s, mail was delivered four or five times a day in Stockholm and Uppsala, allowing for remarkably quick communication even then.

“Today, there are naturally other and faster options, but my point in offering this perspective is that while different ways of communicating are all important – whether through letters, emails, or digital meetings – the need to still meet in person seems to have been constant throughout history. Good things happen when people meet.

“Another thing that strikes me, however, is that one reason why so much happens in the intervals between research meetings is that researchers are often self-motivated and independent, even at the junior level. They do not work primarily for an organisation, but for a specific project or issue. Their goal in participating in a conference is mainly to advance their understanding of a chosen field or topic, such as the expansion of the universe, gene editing, or new chemical materials.”

In addition to the fact that many prize winners share traits such as excelling in knowledge, curiosity, persistence, and fearlessness, they also have another notable thing in common: a relatively large number of Nobel Prize laureates have had previous prize winners as mentors during their careers. Interestingly, these mentors often received the Nobel

Prize only later. In other words, many future Nobel laureates have apparently chosen other future Nobel laureates as their mentors.

“The laureates clearly have a keen sense of which researchers are talented. It means that those who are later awarded Nobel Prizes seem to understand who else is exploring the right topics and working on the most important issues. As a researcher, being able to identify key areas where there is real work to be done – is a crucial trait.”

Unlocking the Nobel Mindset: H o W o PENNESS T o CHANGE UNITES LAUREATES’ IDEAS

We are sharing the foreword of Think Like a Nobel Laureate – Ideas That Change the World by Swedish author Gustav Källstrand, one of the world’s leading experts on the Nobel Prize. The book was published in Swedish last year but has not yet been translated into any other language. The foreword serves as a kind of mission statement, describing the common thread running throughout the book, which is change:

Everything changes, all the time. We encounter change on a more or less daily basis. Some changes we like; some scare us. Sometimes we want everything to be as usual; sometimes that is precisely what we fear most.

Change is also one of the most significant questions in science, philosophy, and culture. How do things change? Why do they change? Can we influence their conditions or results? Can we slow down, accelerate, or change their direction?

Yet it is easy to see change as an exceptional state of affairs. The norm is for everything to be as usual, while transitions from one state to another are often accompanied by ceremonies and rituals, from life events such as weddings or funerals to seasonal celebrations like New Year’s or Midsummer. The constant feels safe, while the inconstant is something we must manage.

This is also evident in the history of science and philosophy, which has been characterised by a search for the eternal, the constant. Even if the world appears chaotic, we seek the underlying rules revealing that the chaos is just an illusion. But what if there is no eternal order? What if everything is fluid?

In this book, you will meet people who have faced situations in which they have grappled with changes in nature, and where the solutions have required or involved new ways of looking not only at the world but also at the nature of change itself. A good place to look for people like this is among Nobel Prize laureates.

That’s because the Nobel Prize is an award given to individuals who have made ground-breaking scientific discoveries and opened up new perspectives, thereby expanding our understanding and the applications of that knowledge.

I have been looking for answers among this group of people for many years. I have researched and worked with the Nobel Prize, and met quite a few Nobel laureates.* It’s a very special feeling to meet someone and hear them describe what it’s like to discover something that no one else has ever seen – to be the first to know something that no one else knows. This book is about what I have

learned from listening to and reading about people and ideas that have changed the world – and what I keep returning to is the question of change.

Take, for instance, scientists like Frances Arnold, who found a way to use evolution to create new chemicals. or Adam Riess, one of the people who discovered that the universe is expanding faster and faster; Jennifer Doudna, who found a new tool for changing our genes; or Giorgio Parisi, who wanted to understand how starlings move in flocks and discovered a new way of looking at science. But also about Jacques Monod, who drew upon his understanding of life’s changes to construct a philosophical worldview, and of course, Albert Einstein, who altered our very understanding of what time is – and thus what is the fundamental basis of all change.

The book explores how people throughout history have sought to understand the process of change, as well as accept and cope with the fact that things do change. It also explores what we can learn from people who in various ways have challenged how we view change.

Science is about exploring the world. often this means following the paths that others have taken before and correcting, confirming, or expanding on what we already

know – which is essential work. But sometimes the paths start to go in circles, at which point someone needs to break new ground. To do that, you have to be open to knowledge itself fundamentally changing.

Scientists who achieve major breakthroughs know that it is only when knowledge changes that you learn something new, so even though it can be challenging, it is the only way forward. Moreover, they under-

from how we view life on Earth, the origins of the universe, the direction of time, and the meaning of life, to the end of the world, among other things.

We will also see that ideas about change are everywhere, even beyond science and philosophy. They are present when we are thinking about mortgages, school choices, careers, and pension funds, or whether things were better in the past, and when we look in the mirror and wonder if there

“ It is more difficult to predict what will happen on a regular Tuesday at work than how the planets move in an alien galaxy”

stand that not changing their knowledge isn’t even an option. Every notion that previous knowledge may be wrong, has already changed the knowledge.

And we can all learn something from this way of thinking. If we nurture the idea that everything is forever changing, our existence becomes both more exciting and more interesting. We discover the beauty of a world not eternal – that life is not a state but a process.

In that sense, this then becomes a book about ideas that are both in change and the cause of change, as well as ideas about change itself. We will examine the nature of the path taken by our ground-breaking Nobel Prize winners, how they changed this path, and which ideas about change they employed or contributed to in doing so. The very idea that things change will, as we shall see, have major consequences for everything,

is anything that can make the passage of time a little gentler.

What makes the question of change both fascinating and relevant is that it deals with everything from the most astonishing science, such as the building blocks of life and the evolution of the universe, to understanding such concrete things as why things get messy at home, or why it is more difficult to predict what will happen on a regular Tuesday at work than how the planets move in some faraway galaxy.

once you start looking for them, you discover questions about change everywhere, even when you’re relaxing in front of the TV, with your favourite films. In any case, I discovered that several of my film favourites turned out to be about change, in different and sometimes unexpected ways, and because of that they too ended up in the book. Both because they serve to illustrate the questions,

and because they themselves illustrate how change is everywhere.

It may seem obvious to state that the world we live in looks the way it does because it has changed – but it’s easy to miss. Both we ourselves and the environment we live in are the result of processes that have affected nature and culture for not just millions but billions of years. The same forces that formed the first stars, that formed galaxies and planets, that caused atoms to form molecules, and made molecules turn into living cells, are affecting our bodies right now.

We are here and now, but neither here nor now are unique positions in the geography or history of the universe. If we want to understand our place in the world, we shouldn’t just try to understand how things happen to be at this point in time, but also the processes behind everything turning out that way.

The interesting thing is not that things are the way they are, but how they turn out the way they turn out, and the goal of this book is to provide inspiration and tools for understanding and dealing with the fact that change is the only constant – and to see how this understanding of the forces of change can make life richer, freer, and more exciting.

* My doctoral thesis on the history of the Nobel Prize was published in 2012 . Since then, I have worked at the Nobel Prize Museum in Stockholm, researching, writing, lecturing, and conducting interviews. For several years, I have also produced the podcast “Ideas that change the world,” which features the prize winners, their discoveries, and their impact on what we know and how we act.

Rotterdam: meet the unexpected

Internationally accessible

■ Europe’s best-connected large city with 2 international airports within 24 minutes reach and high-speed train links to major European cities.

Dynamic ecosystem

■ Europe’s gateway for business and knowledge: strong sectors in Life Science & Health, Energy, Maritime, IT & Tech, Logistics and Urban Planning.

■ A city that reinvents itself –innovative, forward-thinking and globally connected.

Compact congres destination

■ 10.000 hotel rooms within Greather Rotterdam and social programmes all within walking distance.

■ Seamless citywide congress capability for 2.000+ delegates, with Ahoy as the anchor venue and the city as your stage.

Unmatched flexibility

■ 35 breakout rooms, flexible spaces and exhibition halls for hybrid congress formats under one roof.

■ Largest auditorium of the Netherlands (RTM Stage) for up to 4.400+ seats.

Sustainable venue

■ 100% fossil-free building and circular catering.

■ Supporting the city’s vision for sustainable, future-proof congresses.

50 years of experience

■ Trusted partner for international events with over five decades experience in hospitality.

■ Dedicated event team guiding you from bid to closing session.

Ready to elevate your next congress in the Netherlands? Find out more via Ahoy.nl/racc

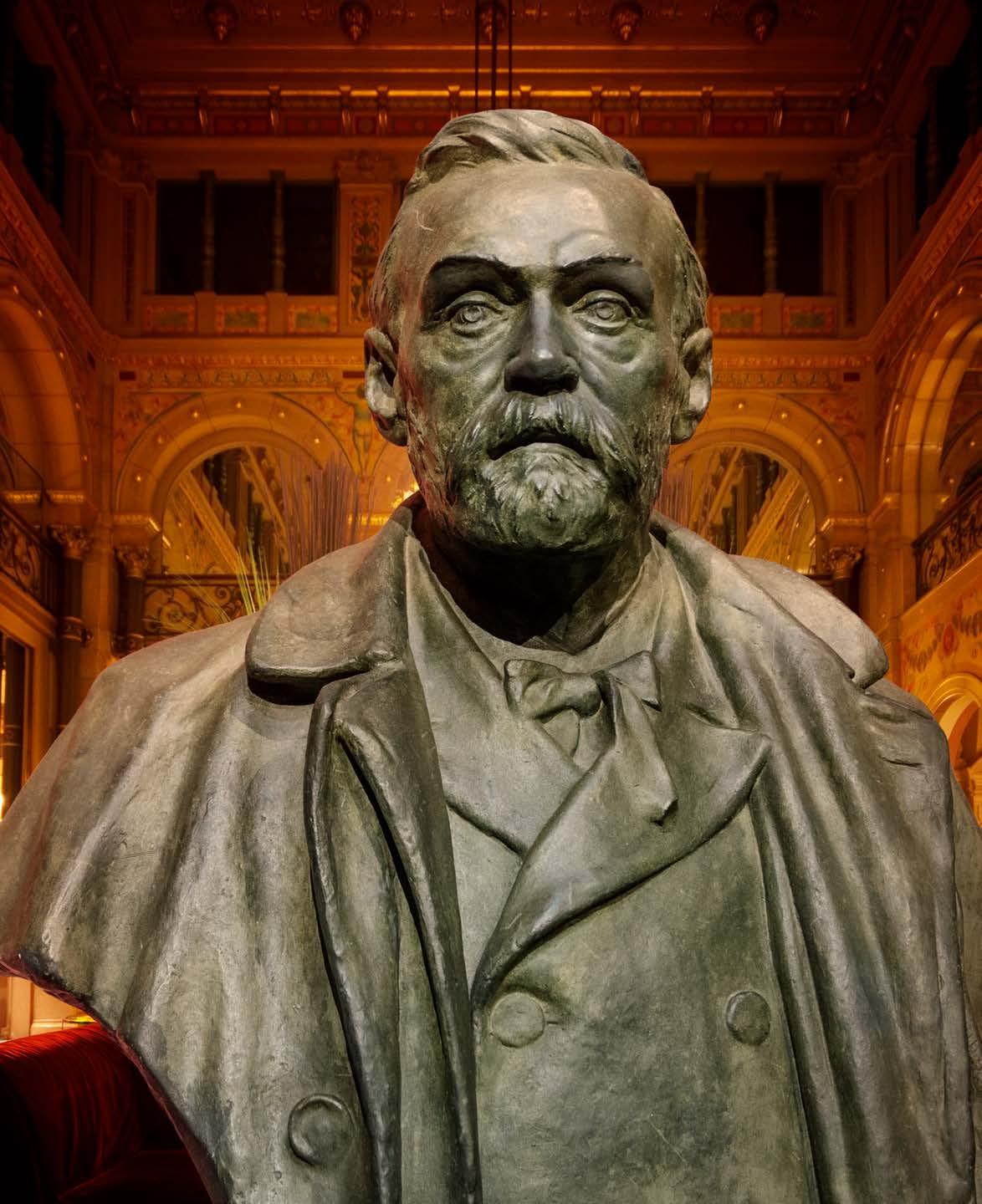

The Man Who Dreamed o F D o ING G oo D F o R HUMANITY

When Alfred Nobel (1833 –1896) patented dynamite in 1867, he didn’t just revolutionise construction and mining, and increase safety for explosives, he ignited a global debate about invention, responsibility, and legacy. Born in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1833 to an engineer father, Alfred Nobel grew up surrounded by scientific experimentation. He was a competent chemist by age 16 and was fluent in English, French, German, and Russian as well as Swedish. His curiosity and relentless drive pushed him to master chemistry, languages, and engineering, setting the stage for one of the most influential careers in industrial history.

Alfred Nobel founded laboratories and factories across Europe, turning his explosive invention into a thriving global enterprise. His business empire spanned more than 90 factories across 20 countries, producing explosives that powered the industrial age and enabled the construction of tunnels, canals, railways, bridges, and roads at unprecedented speed. Alfred Nobel’s greatness lay in his ability to combine the penetrating mind of the scientist and inventor with the forward-looking dynamism of the industrialist.

In parallel, he was very interested in social and peace-related issues and held views considered radical in his era. He had a great interest in literature and wrote his own poetry

and dramatic works. The Nobel Prizes became an extension and fulfilment of his lifelong interests, which, in addition, have become among the most highly regarded of all international awards.

Victor Hugo, the world-famous French writer, human rights activist, and politician, once described Alfred Nobel as “Europe’s richest vagabond.” When he was not travelling or engaging in business activities, Nobel himself worked intensively in his various laboratories, focusing on developing explosives technology and other chemical inventions, including synthetic rubber, leather, and artificial silk. By the time of his death in 1896 , he had 355 patents registered in his name worldwide.

Yet, as Alfred Nobel’s fortune grew, so did his discomfort. He realised that his creations, designed to aid progress and vital construction projects, but also to make handling and transporting previously highly volatile explosives a lot safer, were inevitably also being used in warfare and for other nefarious uses. In 1888 , a French newspaper mistakenly published his obituary under the headline “The Merchant of Death is Dead.” Reading how the world might remember him, deeply affected Alfred Nobel. Determined to reshape his legacy, he made a decision that would outlast every business he built. When he died in 1896 in Sanremo, Italy, he left most

of his wealth to establish the Nobel Prizes, awards that would honour those who “conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.”

Today, Alfred Nobel’s name no longer only evokes explosives but also a long-lasting legacy. one hundred and twenty-four years later, the Nobel Foundation continues to celebrate breakthroughs in the sciences, literature, and peace, embodying the same spirit of innovation that fuelled Alfred Nobel’s entrepreneurial journey. Alfred Nobel stands as a reminder that profit and purpose can coexist, and that a single visionary decision can transform how the world remembers you.

A source of inspiration for this issue of Meetings International is the book “Nobel: The Enigmatic Alfred and His Prizes” (2023), written by the Swedish award-winning author and journalist, Ingrid Carlberg. She tells the fascinating story of the path from Alfred Nobel’s youth to the high-stakes drama that enveloped the dynamite king’s last will. Set against the backdrop of cities such as St Petersburg, Hamburg and Paris, and framed by family quarrels, heartbreak, successes and betrayals. The book is a captivating account of nineteenth-century Europe that explores its political currents, literary treasures and scientific genius. This is a story about breaking boundaries.

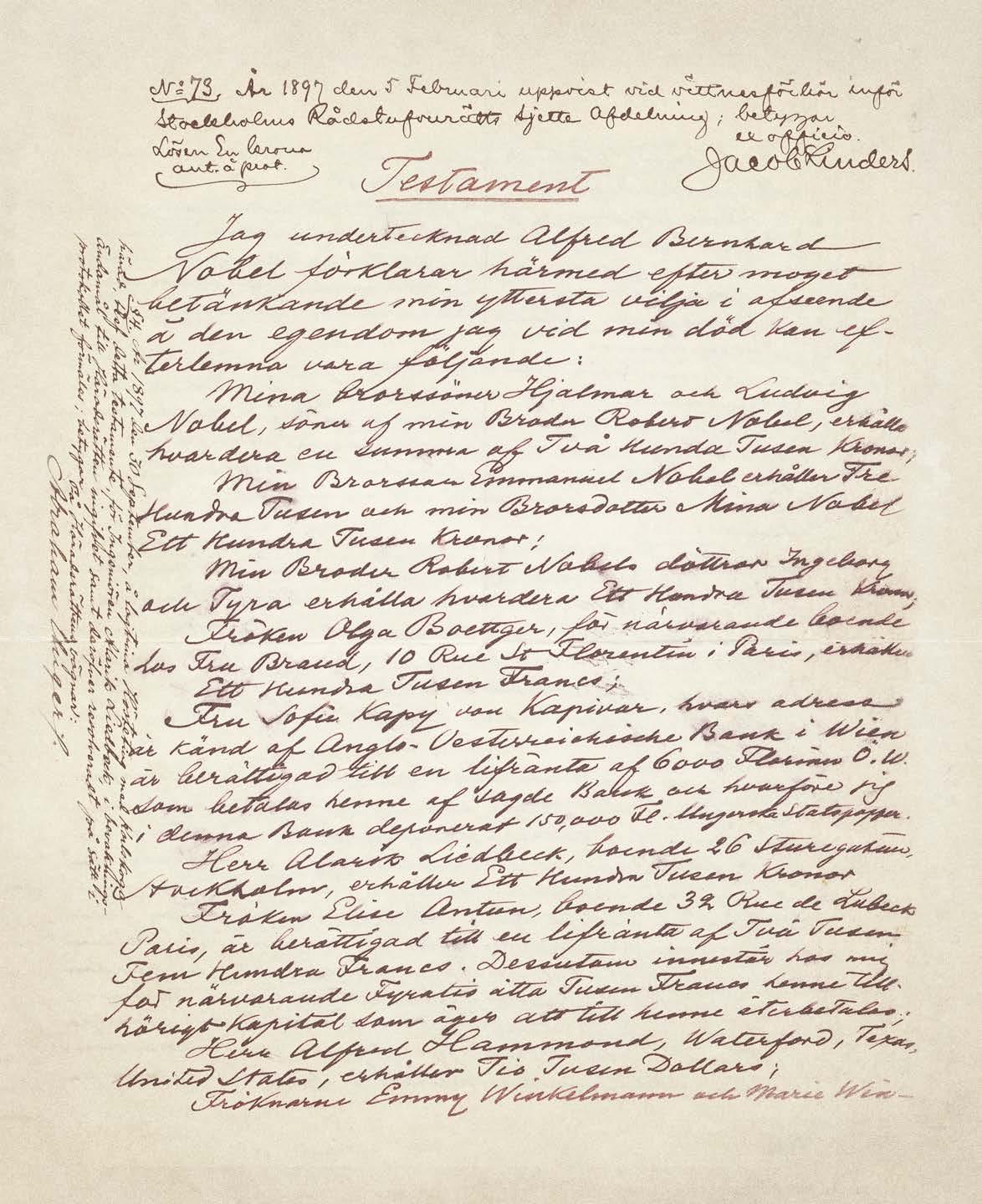

The Last Will: THE LEGACY o F ALFRED N o BEL

Known for being France’s oldest national newspaper, Le Figaro, founded in 1826 , had the following comment on Alfred Nobel’s will, on January 7, 1897: “The will remains a magnificent memorial to the love of humanity, and in that capacity guarantees that the respected name of Mr Alfred Nobel will not fall into oblivion.”

Excerpt from Alfred Nobel’s will in a simplified and abridged version:

“All of my remaining realisable assets are to be disbursed as follows: the capital, converted to safe securities by my executors, is to constitute a fund, the interest on which is to be distributed annually as prizes to those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.

The interest is to be divided into five equal parts and distributed as follows: one part to the person who made the most important discovery or invention in the field of physics; one part to the person who made the most important chemical discovery or improvement; one part to the person who made the most important discovery within

the domain of physiology or medicine; one part to the person who, in the field of literature, produced the most outstanding work in an ideal direction; and one part to the person who has done the most or best to advance fellowship among nations, the abolition or reduction of standing armies, and the establishment and promotion of peace congresses.

The prizes for Physics and Chemistry are to be awarded by the Swedish Academy of Sciences; that for physiological or medical achievements by the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm; that for Literature by the Academy in Stockholm; and that for champions of Peace by a committee of five persons to be selected by the Norwegian Storting. It is my express wish that when awarding the prizes, no consideration be given to nationality, but that the prize be awarded to the worthiest person, whether or not they are Scandinavian.”

Alfred Nobel (1833 –1896), who invented dynamite, became one of Europe’s wealthiest men. Yet he was unmarried, had no children, and

ended his life feeling lonely and bitter, partly because of relatives who were interested in his money. He changed his will several times, writing to a friend: “I rejoice in advance at all the wide-eyed looks and the many curses that the lack of money will cause.”

He believed that large individual fortunes should not be gifted or inherited by relatives. They “become a misfortune by encouraging idleness and thus contributing to the degeneration of the human race.” Instead, he championed the principle of equal opportunities and education for all, helping ambitious young people and science-oriented companies.

Alfred Nobel’s last will was signed in Paris on November 27, 1895 . A few weeks after he died in 1896 , the handwritten will was opened, and many people were surprised by his financial plans. It turned out that he had endowed most of his fortune to a fund, the interest from which would be distributed annually as prize money to those who had done the most good for humanity in the past year. In his last will, Alfred Nobel emphasised the prizes and avoided the detour of donations to institutions. Instead, he wrote that the interest on his fortune should

be divided into five equal parts, with each part awarded as an annual prize.

Three of the prizes were for natural sciences and would go to the most significant discoveries in Physiology or Medicine, Chemistry, and Physics. In addition, Nobel wanted to create a Literature Prize and a Peace Prize. His relatives were not disinherited, but they received only about 0 5 per cent of the inheritance.

in today’s currency. The sum can be compared to the annual salary of an ordinary manual labourer at the time: roughly €50 (SEK 500). Through his donation, he hoped to achieve a more positive legacy, and maybe even a greater appreciation of his achievements as an industrialist.

After setting aside about €150,000 (SEK 1 5 million) for inheritances to loved ones, Alfred Nobel reserved

“ Alfred Nobel dreamed of prizes that were more than mere glory”

outraged, some family members challenged the will in court, igniting a bitter legal battle that dragged on for years. Despite their efforts, Alfred Nobel’s wishes endured. In 1901 , five years after his death, the world saw the inaugural awarding of the five Nobel Prizes.

Alfred Nobel dreamed of prizes that were more than mere glory. He saw scientists and idealists, unlike engineers and industrialists like himself, rarely profiting from their work. Determined to help them, he vowed to ensure his prizes granted them freedom from financial worries so they could pour all their energy into serving humanity.

The idea of creating a scientific and cultural prize emerged during the last years of Alfred Nobel’s life. At the time of his death in 1896 , Alfred Nobel’s assets amounted to approximately €3 million (SEK 33 million), about €135 million (SEK 1 .5 billion)

the rest of his fortune for the international prize. This bold decision transformed the future prize winners into his principal heirs, while the designated institutions became mere presenters. With clear intent, Nobel’s will assigned specific institutions to select the awardees: the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for Physics and Chemistry, the Karolinska Institutet for Physiology or Medicine, and the Swedish Academy for Literature. All these institutions are located in Stockholm.

Alfred Nobel envisioned the Nobel Peace Prize differently; it would not be awarded in Sweden, as the other prizes were, but in oslo, Norway’s capital. There, a five-member committee, chosen by the Norwegian Parliament (Storting), would select the winners. At first, uncertainty clouded several institutions, which doubted their ability to carry out Nobel’s wishes. Tension built, until – after

some hesitation – each institution finally agreed to undertake the responsibility.

When Alfred Nobel wrote his will, Sweden was in a union with Norway, which may explain why he wanted the Peace Prize awarded in oslo. Furthermore, another reason that is often cited is that Nobel believed Norwegian politicians were more committed to peace issues than Swedish politicians.

Alfred Nobel was confident that his prizes would be international, awarded to the most deserving in each field, regardless of origin. Reactions were swift and divided. While some celebrated an award for those who served humanity, others resented that it wasn’t limited to Swedes. At the end of the 19 th century, when nationalist enthusiasm was high in Sweden, certain groups even accused Nobel of betraying his homeland. Yet, seeing himself as a citizen of the world, Nobel believed it was only natural that his prize be international.

The will established the Nobel Prize and led to the creation of the Nobel Foundation in 1900. However, it was only after a lengthy legal process that the Foundation’s statutes were approved. As a result, the first Nobel Prizes were awarded on December 10, 1901 , on the anniversary of Alfred Nobel’s death.

THIS OR THAT?

In Gothenburg, you don’t have to choose.

Here, the vibrant city meets the serenity of the sea. City-centred venues, 15,000 hotel rooms, and a truly collaborative mindset ensure a seamless meeting experience.

As an official UN Sustainable Lifestyle Hub, home to renowned universities with 70,000 students and leading global companies, Gothenburg is a hotspot for innovation, a master of collaboration, and a front-runner in sustainability.

Welcome to the Nordic capital of getting things done.

The Nobel Foundation STEWARDS AND PR o M o TES ALFRED N o BEL’S LEGACY

“Alfred Nobel dreamed of a better world. And in many ways, the world has become a better place since he wrote his will in the late 19th century. Thanks to scientific, cultural, and economic developments, more people have the opportunity to fulfil themselves and live long, rich lives. Scientific achievements have not only made new technologies possible; they have also given us a deeper understanding of how everything in our universe functions – from the stars to the cells of our bodies. Cultural advances have lessened the impact of prejudice and tradition. Economic growth has laid the groundwork for technological and social progress as well as material wealth. We now have societies where people are able to live the lives they desire to a degree the world has never seen before.”

From the opening address at the Nobel Prize award ceremony on December 10 , 2017, delivered by Professor Carl-Henrik Heldin, Chairman of the Nobel Foundation.

The Nobel Foundation, located in Stockholm, Sweden, is a private institution established in 1900 that manages Alfred Nobel’s fortune to support the Nobel Prizes. Its primary mission is to manage Nobel’s assets to ensure the long-term financial stability of the prizes and to safeguard the independence of the prize-awarding institutions that select the laureates. The Foundation also works to strengthen the Nobel Prize brand, represent the Nobel organisation, and promote its values through various outreach activities to share knowledge and inspire future generations. Alfred Nobel’s will, written in 1895 , was the single most decisive factor in shaping the Nobel Foundation’s structure and purpose. In his will, he dictated that nearly all his remaining estate be invested in safe securities to create a fund whose interest would annually finance prizes for those who conferred the “greatest benefit to humankind.” He specified not only the prize fields of Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, Literature, and Peace, but

also the exact institutions awarding the prizes, stipulating independence from personal or national bias.

The Nobel Foundation was founded in 1900, four years after Swedish scientist Alfred Nobel died in Sanremo, Italy. The institution was set up primarily to invest his fortune and to manage the intangible value of the Nobel Prize. While the first task remains basically the same after more than a century, the second has

The Nobel Foundation’s statutes were approved by Swedish King Oscar II in 1900, defining its administrative and investment duties. Its board consists of representatives chosen by the Nobel Prize-awarding institutions. The Foundation itself does not select laureates. Instead, it manages the prize endowment, handles publicity, and coordinates the annual awards ceremony in Stockholm and oslo.

“ The Nobel Centre will be a space for dialogue between science, literature, and peace efforts”

grown in importance as the prize has accumulated prestige over the years. Furthermore, the Foundation ensures the independence of the academic institutions that nominate Nobel Prize laureates, and organises the prize ceremony and the Nobel festivities in December.

Alfred Nobel also appointed the executors of the will, whose duty was to establish an organisation for the prize. Their task in the subsequent years was to negotiate how this prize was to be set up, with Nobel’s relatives and the Nobel Prize-awarding institutions: The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for the prizes in Physics and Chemistry, Karolinska Institutet for the prize in Physiology or Medicine, and the Swedish Academy for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Furthermore, a five-person committee was appointed by the Norwegian Parliament to select the Nobel Peace Prize laureate. At the time, Sweden and Norway were a union (1814 –1905).

The history of the Nobel Foundation can roughly be divided into three phases. The first covers the formative years from 1900 to the 1920 s. During this period, there was at first an ambition to make the Foundation a unified institution. However, the prize-awarding institutions were more interested in establishing a close connection with the Nobel institutes, which meant that the Nobel Foundation took on a more administrative and representative role. It focused on the investments and on arranging the prize award ceremony. It was manifest in the plans to build a Nobel Palace where the prize would be awarded. When this proved too expensive, the Foundation settled on holding the ceremony in Stockholm’s new City Hall. It meant a slightly less visible role for the Nobel Foundation, and also made it a more integral part of the public life in Stockholm.

In the second phase, from the 1920 s to the 1960 s, the Foundation

became a funding agency in a way it had not been before or since. At the time the Nobel Institutes were established, the prize-awarding institutions effectively utilised the Nobel funds as a scientific resource. In this way, the Foundation played a significant role in a time when government funding for research did not exist in Sweden. This role waned after World War II, when research councils were set up. Eventually, the Nobel Institutes were either closed or transferred to government ownership, thus ending the second phase in the Foundation’s history.

During the second phase, investing Alfred Nobel’s money remained of utmost importance, as did organising the Nobel Prize festivities. However, during the 1970 s and 1990 s, the public aspects of the prize became a higher priority for the institution. one of the priorities of this period was to modernise the award ceremony and banquet. It was done through a series of careful steps and culminated in a large jubilee in 1991 , when the Nobel Foundation’s 90 th anniversary was celebrated with the most ambitious festivities to date. The growing interest in the public image of the Nobel Prize continued in the 1990 s, leading to the establishment of the NobelPrize.org website in 1995 , the Nobel Museum in 2001 , and the media rights entity Nobel Media in 2004

From the 1970 s to the 1990 s, the ceremonies underwent modernisation, and to some extent, media relations also evolved. The period from the mid-1990 s to the present has built a new structure for public relations. It accelerated in the 2010 s, with plans to create a new Nobel Centre in Stockholm and for Nobel Media to organise international public events.

The Nobel Museum, now renamed the Nobel Prize Museum, has been

“Today’s challenges for the Nobel Foundation include addressing mistrust and attacks on science”

a presence in Stockholm since 2001 , honouring Alfred Nobel, who was born in the city. The museum’s mission is to spread knowledge about the Nobel Prizes and the achievements of its laureates, thereby protecting the prestige of the prize and inspiring people worldwide. In 2004 , the Nobel Peace Centre opened in oslo, tied to an ambitious digital strategy, with the number of social media followers increasing from a few hundred thousand to several million.

Next year marks the 125th anniversary of the Nobel Foundation. one of the most critical projects for the future is the planned construction of a Nobel Centre in Stockholm. In 2031 , you will be able to explore the work and the ideas of the laureates in a new public building. The Nobel Centre will be a space for dialogue between science, literature, and peace efforts, brought to life through exhibitions, workshops, lectures, cultural events, and family activities. A part of the centre’s motivation is to create a venue that can accommodate more visitors interested in the Nobel Prize. There was also a deeper purpose: to further and spread the values that the Nobel Prize represents.

Today’s challenges for the Nobel Foundation include addressing

mistrust and attacks on science, promoting sustainable and green innovation, ensuring the prizes are inclusive and representing diverse voices, while maintaining relevance in a rapidly changing world, particularly with the rise of AI. The Foundation is also serious about facing the challenges of adapting its ceremonies and traditions to modern circumstances, as the Foundation’s former CEO, Lars Heikensten, put it: “We are in this forever.”

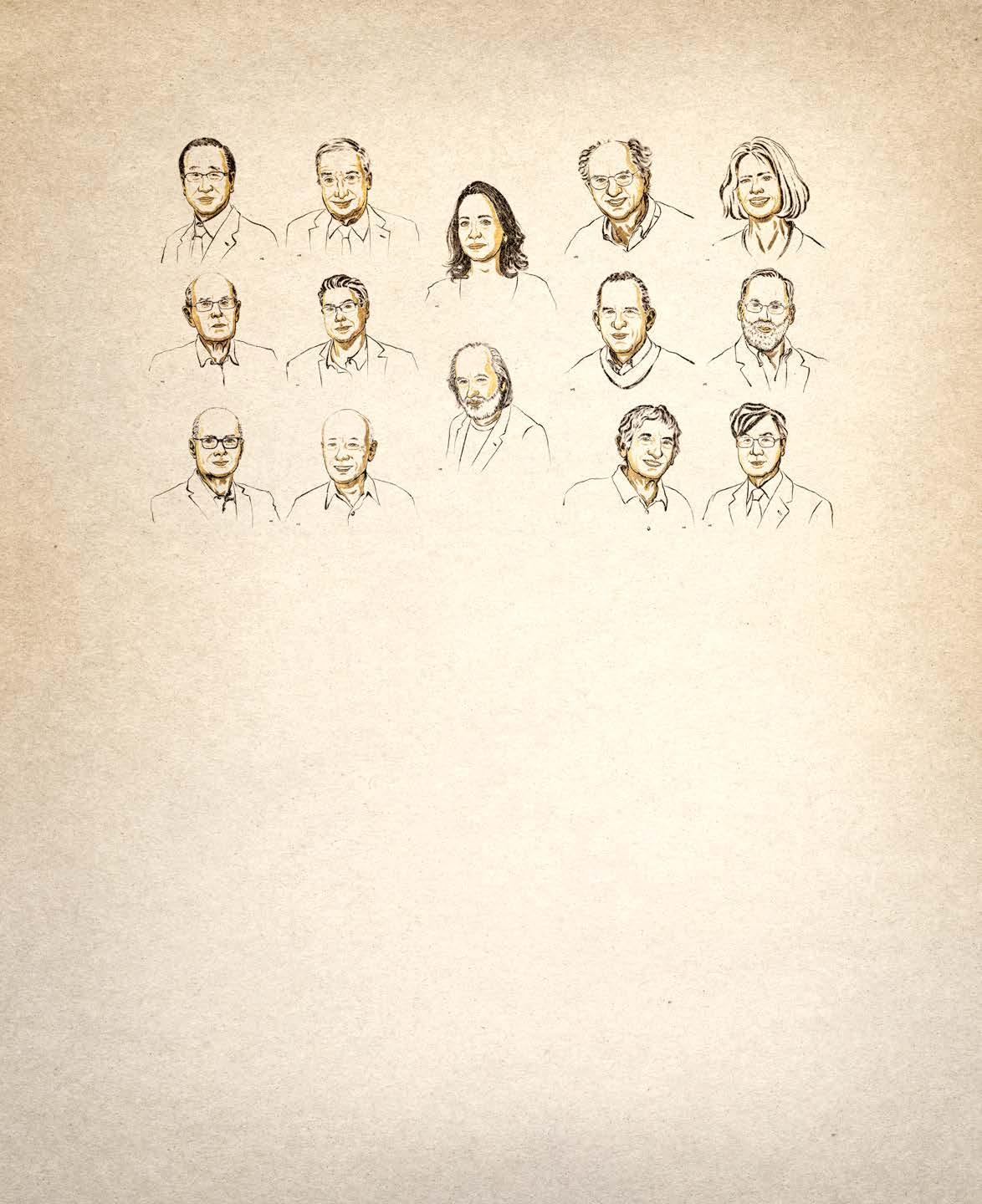

Breakthroughs for Humanity: MEET THE 2025 NOBEL LAUREATES

Six prizes were awarded for the achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates’ work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to advancing democratic rights.

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institutet has decided to award the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to:

Mary E Brunkow, Institute for Systems Biology, Seattle, USA

Fred Ramsdell, Sonoma Biotherapeutics, San Francisco, USA

Shimon Sakaguchi, Osaka University, Japan.

“For their discoveries concerning peripheral immune tolerance”

They discovered how the immune system is kept in check. The body’s powerful immune system must be regulated, or it may attack our own organs. Mary E Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell, and Shimon Sakaguchi are awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2025 for their groundbreaking discoveries concerning peripheral immune tolerance, which prevents the immune system from harming the body.

The Nobel Prize in Physics The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics to:

John Clarke, University of California, Berkeley, USA.

Michel H Devoret, Yale University, New Haven,

and the University of California, Santa Barbara, USA

John M Martinis, University of California, Santa Barbara, and Qolab, Los Angeles, USA.

“For the discovery of macroscopic quantum mechanical tunnelling and energy quantisation in an electric circuit”

Their experiments on a chip revealed quantum physics in action. A major question in physics is the maximum size of a system exhibiting quantummechanical effects. The laureates conducted experiments with an electrical circuit, demonstrating both quantum-mechanical tunnelling and quantised energy levels in a system large enough to be held in one’s hand.

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2025 to:

Susumu Kitagawa, Kyoto University, Japan.

Richard Robson, University of Melbourne, Australia.

Omar M Yaghi, University of California, Berkeley, USA

“For the development of metalorganic frameworks”

Their molecular architecture contains room for chemistry. The Nobel Prize laureates have created molecular constructions with large spaces through which gases and other chemicals can flow. These constructions, metal-organic frameworks, can be used to harvest water from desert air, capture carbon dioxide, store toxic gases or catalyse chemical reactions.

The Nobel Prize in Literature The Swedish Academy has decided to award the Nobel Prize in Literature 2025 to:

Hungarian author László Krasznahorkai.

“For his compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art”

László Krasznahorkai is an epic writer in the Central European tradition, extending from Franz Kafka to Thomas Bernhard, characterised by absurdism and grotesque excess. But there are more strings to his bow, and he soon looks to the East in adopting a more contemplative, finely calibrated tone. The result is a string

of works inspired by the deep-seated impressions left by his journeys to China and Japan.

The Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences The prize is officially called the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel but is awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, and the Academy has decided to award the Prize in Economic Sciences 2025 to:

Joel Mokyr, Northwestern University, Evanston, USA.

“For having identified the prerequisites for sustained growth through technological progress”

Peter Howitt, Brown University, Providence, USA, and Philippe Aghion, Collège de France and INSEAD, Paris, France, and the London School of Economics and Political Science.

“For having explained innovationdriven economic growth, including the key principle of creative destruction”

The three men represent contrasting but complementary approaches to economics. Dutch-born Joel Mokyr is an economic historian who delved into long-term trends using historical sources, while Canadian-born Peter Howitt and Philippe Aghion relied on mathematics to explain how creative destruction works.

Philippe Aghion is also a recent honorary doctor at Stockholm University due to his strong connection to the university and his work supporting students.

The Nobel Peace Prize The Norwegian Nobel Committee has decided to award the Nobel Peace Prize for 2025 to:

Venezuelan politician María Corina Machado

“For her tireless work promoting democratic rights for the people of Venezuela and for her struggle to achieve a just and peaceful transition from dictatorship to democracy”

In the past year, María Corina Machado has been forced to live in hiding. Despite serious threats against her life, she has remained in the country, a choice that has inspired millions of people. She has brought together the opposition in her country. She has never wavered in resisting the militarisation of Venezuelan society. She has been steadfast in her support for a peaceful transition to democracy.

Selecting the Nobel Prize Laureates BASED o N PRINCIPLES DE v EL o PED DURING NEG o TIATI o NS IN 1897–1900

Alfred Nobel’s will does not specify details of the nomination process itself, but instead focuses on who will select the laureates and what criteria will apply. The will states that laureates are to be chosen by specific institutions: The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for both Physics and Chemistry, the Karolinska Institutet for Physiology or Medicine and the Swedish Academy for Literature. It also stated that no nationality should be taken into account when choosing the laureate. The Nobel Prize laureates are awarded for significant discoveries that advance science and benefit humankind. The emphasis is on groundbreaking discoveries, not lifetime achievement or leadership. The process and nomination procedures for selecting Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine, Physics, and Chemistry are based on principles developed during negotiations in 1897–1900. The procedure is highly structured and confidential. For each prize category, there is a Nobel Committee, and the expert committees at distinguished Swedish scientific institutions coordinate this

work. Nominations are by invitation only, and the names of nominees and nominators remain secret for 50 years.

Main steps of the nomination process Each year in September, each committee sends confidential nomination forms to thousands of qualified experts. These include previous laureates, academy members, parliamentarians, university professors, other researchers, and members of relevant academies worldwide.