MARIELLA ATTARD

Montelukast (Singulair) has been in the news recently, with reports that US government researchers have found the drug binds to brain receptors linked to psychiatric function.

The TGA has told ARR it’s currently “working with the sponsor to strengthen existing warnings in the PI”.

Australian experts say the neurocognitive side-effects of montelukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist treatment for asthma and allergic rhinitis, have long been known. In most cases it is not the

p2

People with an eosinophilic exacerbation of asthma or COPD will have a better option than corticosteroids for the first time in over half a century.

The benralizumab injection is a targeted treatment that is more effective than a steroid tablet specifically for this type of exacerbation, which can be determined by a simple blood test.

A study published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine has found that eligible patients treated this way were four times less likely to need re-treatment or die compared with one-size-fits-all standard of care.

“Someone is being hospitalised for an asthma or COPD exacerbation every seven minutes in Australia,” Australian lead author, Dr Sanjay Ramakrishnan, who is now clinical senior lecturer at the University of Western Australia but began working on the study at the University of Oxford, UK, told the media.

“Together, they account for the most preventable hospital admissions in Australia. COPD is the third leading cause of death worldwide but treatment for the condition is stuck in the 20th

century. We need to provide these patients with life-saving options before their time runs out.”

One in 13 Australians over the age of 40 has COPD, around half without knowing it, and many of the 474 asthma-related deaths in Australia last year were avoidable, the researchers said.

About half of asthma and 30% of COPD exacerbations are caused by inflammation due to high eosinophil levels.

Benralizumab targets eosinophils and is one of four monoclonal antibodies already used in asthma management in Australia as a preventative addon treatment for patients aged 12 years and up with severe allergic or eosinophilic asthma that can’t be controlled with high-dose

➥ Montelukast due for ‘stronger’ side effects warning – from Page 1

recommended treatment as there are more effective alternatives.

The preliminary research findings, covered by Reuters, were presented at an American College of Toxicology meeting in Austin, Texas. Reuters said the two FDA scientists told them the receptors were involved in various functions including mood, impulse control, cognition and sleep and while the data did not confirm this led directly to harm, “it’s definitely doing something that’s concerning,” said researcher Julia Marschallinger.

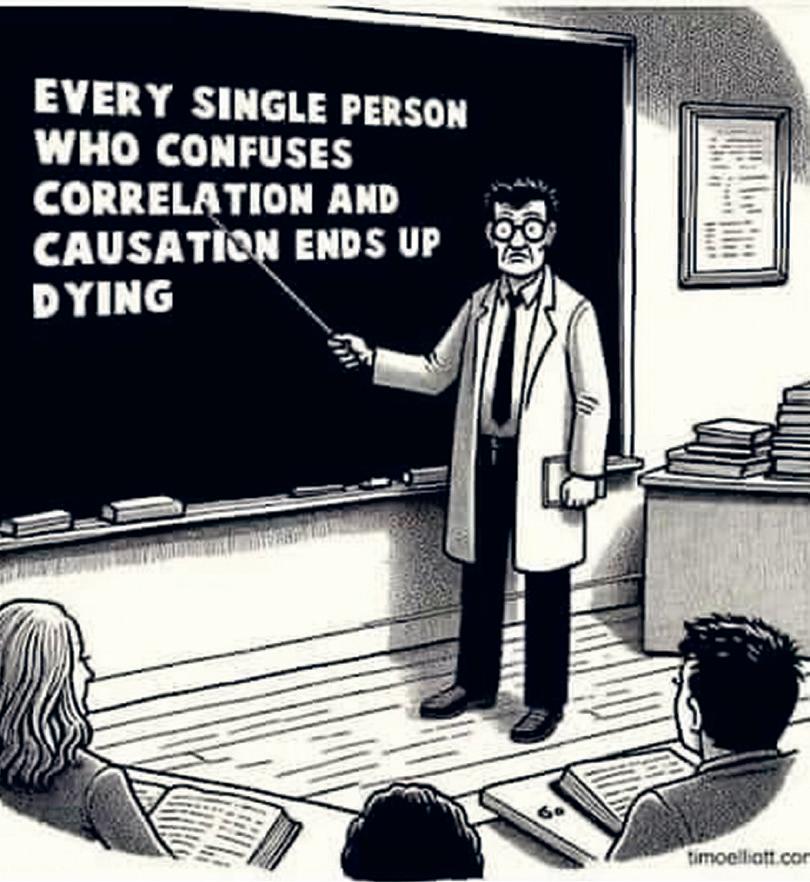

A spokesperson for the Department of Health and Aged Care told ARR that 339 adverse events had been reported since late 2014 in which the patient was taking montelukast; a psychiatric condition was noted in 204 of them. Of the 16 events reported this year, three were death from suicide where montelukast was the only drug the patient was taking.

“Reporting of an adverse event to the TGA and publication in our Database of Adverse Event Notifications (DAEN) – medicines does not necessarily mean that a causal link with the medicine has been established,” the spokesperson said.

In a TGA safety investigation conducted this year after warnings were strengthened in the US, the Advisory Committee on Medicine (ACM) told the TGA “the updated evidence did not identify any new neuropsychiatric risks; and the existing evidence for the association between montelukast and neuropsychiatric risks had not changed and remained uncertain,” the spokesperson said.

“However, on balance, the ACM

advised that, while the scientific and clinical evidence to 2024 does not demonstrate a causal association between montelukast and neuropsychiatric symptoms, a boxed warning would now be appropriate to ensure alignment with international regulators and in acknowledgment of consumer concerns.

“In formulating the boxed warning, the ACM supported careful wording that neuropsychiatric events are generally mild and may be coincidental.”

Professor Peter Wark, a member of the National Asthma Council Australia Guidelines Committee, conjoint professor of medicine at Monash University and a respiratory and sleep specialist at John Hunter Hospital, Newcastle, said current research showed an association between neurocognitive effects and montelukast in adults, but it was inconclusive in children.

“The neurocognitive effects were not well defined, and that’s a bit problematic,” he told ARR.

“And the evidence was really not strong enough to make a recommendation that montelukast was clearly associated with them in children. But certainly that association exists in adults and it does seem to be strong.”

Importantly, montelukast is not recommended as first line of treatment for asthma

“That’s probably the most important thing to say, and clearly the guidelines say it’s inferior to inhaled corticosteroids,” said Professor Wark.

“Inhaled corticosteroids with LABA is a better choice, even in

the mechanism of adverse effects sometimes seen after commencement of montelukast.

She said that although the risk of these adverse effects was low and use of the drug was decreasing, it was important for parents and practitioners to be aware of the possibility.

Adverse effects including sleep disturbance, behavioural problems and, rarely, suicidal ideation were well known and documented in product information and consumer medicines information leaflets, said Professor Reddel.

“The potential for these adverse effects to occur with montelukast treatment is also described in Australian and international asthma guidelines. Every time montelukast is mentioned in the GINA strategy report, there is a reminder to discuss potential neuropsychiatric adverse effects with the patient or parent/ caregiver.”

children, certainly in adolescents. In terms of regular treatment, montelukast is not as effective in children over the age of six. And in younger children the evidence for montelukast is equivocal. It performs no better than inhaled corticosteroids, either as needed or regularly.”

Montelukast, which is taken orally, was marketed in the US as being easier for young children to use than inhalers, he said, but in fact the chewable tablets were no better tolerated in children than masks with spacers.

“The concern has been to avoid corticosteroids in that age group. Regular use of inhaled corticosteroids has certainly been shown to lead to a temporary decline in height gain, but these kids do catch up later on.

“Interestingly, if you treat asthma intermittently with inhaled corticosteroid and short-acting beta agonist, it’s as effective as montelukast, and you don’t get the impact on growth that you see with regular everyday use.”

In children under six, it’s harder to determine when they require preventative treatment, but where it’s persistent disease or frequent severe intermittent disease, inhaled corticosteroids is “at least equivalent” to montelukast and is “probably superior”, said Professor Wark.

Professor Helen Reddel, respiratory physician, research leader at the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research and chair of the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Science Committee, said many drugs crossed the blood-brain barrier but the FDA study could perhaps help with understanding

She noted that in a large cohort study in adults with asthma, a new mental health diagnosis of anxiety was more likely in those who were taking montelukast than those who were not (6.4% vs 4.7%).

“Adverse effects seem to be more likely in children,” said Professor Reddel. “In a wellconducted study of children aged one to 17 years started on montelukast, 16% of parents reported that the treatment had been stopped within a couple of weeks because of their child developing symptoms such as irritability, aggressiveness or sleep disturbance.

“The vast majority of the adverse effects are minor. In the case of young children, if nightmares, irritability or behaviour problems begin within a couple of weeks after starting montelukast, the medication can be stopped and replaced with an alternative asthma treatment.

“Once someone has been taking a medication for months or years, it’s really difficult to disentangle whether a behavioural or mental health problem is due to the medication or might have occurred anyway. Improvement of the symptoms after the medication is stopped, and recurrence if it is restarted, is a good indication that the medication was the problem.”

A spokesperson from Organon, the company that markets Singulair, told ARR: “Organon is aware of the recent press and scientific discourse in relation to Singulair ... We remain confident in the efficacy and safety profile of Singulair when used in accordance with the approved product information. The product label ... contains appropriate information regarding Singulair’s benefits, risks and reported adverse reactions.”

Asthma and COPD rates are fairly stable, but adherence to asthma meds is dropping, new stats show

HELEN TOBLER

The number of people taking biologics for asthma has tripled in four years, while adherence to asthma medication is falling, according to the latest Australian data.

A report from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare shows that the overall prevalence of both asthma and COPD has been stable for 21 years.

Fewer people are visiting emergency departments or dying because of their asthma (from 297 per 100,000 in 2018-19 to 232 in 2020-21), and rates of asthma-related hospitalisations have also dropped since 2017.

But fewer people with asthma have good adherence to preventer medication, with adherence falling to 31% in 2022-23 from 33% in 2017-18.

Adherence to biologic therapies is stable,

Overall, asthma control is getting better

apart from a slight downward trend among people aged 34 and under.

And between 2018–19 and 2022–23, the number of people dispensed at least one biologic more than tripled from 810 to 2900.

Overall, asthma control is getting better.

In 2022-23, 27% of people aged 40 and under

were considered to have poor asthma control compared with 29% in 2017-18 (based on their use of reliever medication).

More males (29%) had poor asthma control than females (26%).

For people aged 35 to 40, 31% had poor asthma control, which was higher than for all other age groups.

“Rates have changed little since 2017–18, apart from spikes in 2019–20 and 2020–21 likely related to the 2019 bushfires and covid-19 pandemic,” the authors said.

Overall, the prevalence of asthma remained relatively stable over 21 years, at 12% in 2001 and 11% in 2022.

Asthma is the leading cause of disease burden for children aged one to four (11%) and five to nine (13%). Prevalence was higher among boys aged 0-14, but higher among females over 15.

“This change in prevalence for males and females over the age of 15 is likely to be due to a complex interaction between changing airway size and hormonal changes that occur during adolescent development, as well as differences in environmental exposures,” the AIHW authors said.

Around 65% of people with asthma also had one or more other chronic condition and 41% had a mental or behavioural condition.

While asthma rates don’t vary according

➥ First new treatment in 50 years for asthma, COPD exacerbations – from Page 1

Awareness is warranted and better treatments exist, experts say

inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta 2 agonists.

Standard treatment for acute exacerbations is prednisolone, which causes side-effects including diabetes and osteoporosis.

This phase II trial, conducted in the UK,

included 158 adults (54% female, mean age of 57) who presented with an acute exacerbation of either COPD or asthma, with a blood eosinophil count of 300 cells per µL or higher.

They were equally randomised to receive either prednisolone 30mg once daily

for five days and one 100mg injection of benralizumab; or placebo tablets once daily for five days and one 100mg injection of benralizumab; or prednisolone 30mg once daily for five days and one placebo injection.

Of those who were only given the standard steroid tablet treatment, nearly three-quarters failed treatment within three months.

That figure was 45% overall for the patients in the other two groups where patients received benralizumab.

At 28 days, symptoms of cough, wheeze, sputum and breathlessness were significantly better for benralizumab patients than for the steroid only group. And hyperglycaemia and sinusitis or sinus infection adverse events only occurred in participants who had prednisolone.

In addition, the authors said the findings suggested treatment with benralizumab reduced future need for corticosteroid treatment.

“[O]n the injections, it’s fantastic. I didn’t get any side effects like I used to with the steroid tablets. I used to never sleep well the first night of taking steroids, but the first day on the study, I could sleep that first night, and I was able to carry on with my life without problems,” trial

to different socioeconomic areas, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is far more common in rural and remote areas and in disadvantaged areas.

The report also shows that almost nine out of 10 people with COPD have another chronic condition, and the disease accounts for 1% of all GP appointments.

Around 638,000 Australians have COPD –2.5% of the population but 10% of those aged 85 and over.

Prevalence of COPD has remained stable over 10 years, barely shifting between 2011–12 (2.3%) and 2022 (2.2%).

Last year, COPD caused half of the total burden of all respiratory diseases in Australia, 71% of fatal burden and 3.6% of the total disease burden. In 2022, COPD caused 4% of all deaths in Australia.

The disease affects slightly more women than men.

In 2021–22, there were 53,000 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of COPD for people aged 45 and over.

Of people with COPD, 87% had at least one other chronic condition, most commonly mental or behavioural conditions (49%), arthritis (45%), and asthma and back problems (both 42%).

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 27 November 2024

participant Geoffrey Pointing told media.

Professor Peter Wark, member of the National Asthma Council Australia Guidelines Committee, conjoint professor of medicine at Monash University and a respiratory and sleep specialist at John Hunter Hospital, Newcastle, told ARR the findings of the trial were “really exciting”.

“It’s huge,” he said.

“And the group that just received benralizumab and received no prednisone was non inferior to the other arms.

“So it really says that if you select these people, and it doesn’t matter whether they’ve got a label of asthma or COPD, but if they have an acute exacerbation associated with eosinophilia, they get a better response with benralizumab without exposing them to oral corticosteroid at all.”

Professor Wark confirmed that the autoinjector could be easily administered in a primary care setting or any hospital in Australia.

“It’s such an important and frequent problem and yet this is probably the most novel intervention we’ve seen in this space in many, many years,” he said.

The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 27 November 2024

The program aims to connect parents of children and babies with evidence-based education while they wait to see a specialist

AMANDA SHEPPEARD

Anational pilot and research program aimed at connecting parents of children and babies with eczema with expert advice while they wait to see dermatology and allergy specialists has launched in Western Australia.

Perth Children’s Hospital will be the first location to offer the program, known as Eczema Connect, which has been developed by Allergy & Anaphylaxis Australia.

The free service provides parents and caregivers with evidence-based information and practical tools to help them manage their child’s eczema as they wait to see a dermatologist or allergy specialist.

Allergy & Anaphylaxis Australia CEO Maria Said told Allergy & Respiratory Republic she believed the pilot would be welcomed by Australian specialists as it offered a lifeline for parents while they waited for an appointment.

“Wait lists are long around the country,” she said.

“We can support them by delivering an email to their inbox, sending them to credible information in plain, easy to understand English, not medical jargon, and encouraging them to call our health professionals, our allergy educators, or our national helpline if they have questions.”

Ms Said said demand for dermatologists and allergy specialists across Australia had seen waiting times blow out.

“While severe cases of eczema are prioritised,

some children and babies can wait more than six months for an appointment,” she said.

“Eczema is a chronic condition and when severe it places a huge burden on the whole family. While they wait, parents are left feeling helpless and desperately hunt for answers from Dr Google, social media or advice from family and friends, which can be well-intended, but often misguided and even dangerous.

“Many parents remove foods from their child’s diet thinking it may be the cause, when it is not. Eczema is rarely linked to a child’s diet and removing foods can place them at an increased risk of developing a food allergy.”

Eczema Connect has been developed by eczema nurses, allergy specialists and a dermatologist. It includes resources from the National Allergy Council and the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy.

Referred parents will receive a range of easy-to-understand fact sheets, videos and webinars with evidence-based advice from

allergy specialists, including nurses trained in eczema.

Parents waiting to see a specialist also have access to a support line so they can speak directly with a qualified allergy educator from Allergy & Anaphylaxis Australia.

“So, we’re not diagnosing them; we’re basically supporting them with the basic treatments of eczema [such as] explaining what wet dressings are, explaining that a bleach bath is no different to swimming in a chlorinated pool, for example,” Dr Said explained.

“When you mention a bleach bath to a parent whose baby’s skin is bleeding, they look at you like, ‘I’m not going to put my baby in bleach’. But having the time to explain that to the parent, to explain how much moisturiser to use, how much steroid cream and for how long to use it – all of that information greatly helps these parents.”

Professor Michaela Lucas, a clinical

immunology/allergy specialist at the University of Western Australia, said early, credible information and support was crucial.

“We are excited to be trialling a program that could successfully bridge the gap and empower parents with credible information right from the start,” she said.

“When treated and managed correctly, eczema can clear up in a matter of weeks, helping to reduce suffering from relentless itchiness and inflammation.

“Credible, easy to understand information for parents and carers is critical, so they can help their child as best they can while they are waiting to be seen by a specialist. The program also helps reinforce what the general practitioner has communicated in relation to management of eczema.”

The Eczema Connect pilot will also be the focus of a research trial in collaboration with the University of Western Australia to evaluate the effectiveness of the program as an intervention.

Ms Said told ARR that the study results would be used to inform a rollout of the program in other states.

“Our hope is that we’ll be able to prove that the concept does help people who are in the community waiting to be seen, and that by the time they get to see the specialist, hopefully these people are not taking foods out of diets and not doing treatments that are not evidence-based, they’re listening to science, and that they feel supported and that they persist to do what is seen as best practice for eczema.”

The Eczema Connect pilot program and research trial are funded by the Department of Health and Aged Care through the National Allergy Council, a partnership between Allergy & Anaphylaxis Australia and the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy, the peak patient and medical bodies for allergic disease in Australia. The project has also received support from sponsors of Allergy & Anaphylaxis Australia.

LINCOLN TRACY

The Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee have removed the need for patients with uncontrolled severe asthma to have trialled oral corticosteroids before being eligible for a biologic prescription on the PBS. The change, which came into effect at the start of the month, means the PBS authority requirements for benralizumab, dupilumab, mepolizumab and omalizumab now

carry a new definition of “optimised asthma therapy”, which still requires adherence to maximal inhaled therapy (including high dose ICS plus LABA therapy) for at least a year, unless it is contraindicated or the patient is unable to tolerate it.

“The PBAC did not consider that the change to the OCS clinical criteria would increase the eligible population and therefore considered there to be nil financial impact to the government,” the committee said in its public outcomes document.

The decision came on the back

of a submission from GSK, who sponsor mepolizumab (Nucala). The pharmaceutical company’s request was supported by the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy.

GSK had also asked for a reduction in the PBS authority level required to prescribe the drug, which the committee declined.

“The PBAC considered that, while the available data suggested that the growth of mepolizumab is gradually stabilising, the overall uncontrolled severe asthma market continues to grow. The PBAC therefore considered

that it would not be appropriate to amend the circumstances of mepolizumab in isolation, noting the growth of the overall anti-interleukin-5 market for uncontrolled severe asthma,” the committee said.

The change for the four biologic agents has been restricted to the oral corticosteroids requirement, with other criteria – like the requirement for the patient to have a blood eosinophil count exceeding 300 cells/μl –remaining unchanged.

The updated PBS form is available via the Services Australia website.

Propellants from our most commonly used devices are much worse than CO2 and methane, and we must reduce the damage

MARIELLA ATTARD

Inhalers are contributing to global warming, and clinicians can contribute to the solution, says The Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand’s position statement published last month in Respirology “Choosing an appropriate inhaler for an individual involves consideration of factors such as dexterity, inspiratory capacity and cost. In our current climate emergency and with the availability of lower carbon alternatives, health professionals should also consider environmental impact,” the statement says. The culprit is largely the hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) propellant used in pressurised metered dose inhalers (pMDIs), along with their manufacture, distribution and disposal.

These inhalers are estimated to be responsible for 13% of healthcare’s total carbon footprint. They are currently the most common devices used by more than 3 million Australians and 700,000 New Zealanders with airway diseases such as asthma and COPD. Work is under way to reduce the carbon footprint as required by international ozone agreements.

But in the meantime, “[t]here are positive steps that prescribers can make now, by considering environmental impact in the decision-making algorithm when prescribing, dispensing and recommending inhaler

medications, with a focus on improving asthma control and reducing unnecessary pMDI use,” the statement says.

“It is everyone’s responsibility to consider if and how they can take action to help mitigate the detrimental environmental impact of inhalers and we need to act now.”

The society proposes the following strategies:

• Accurate diagnosis to avoid unnecessary treatment

• Better disease control to reduce the need for reliever therapy

• Choosing inhalers with a lower carbon footprint where possible

• Educate patients and health professionals about the climate impact

• Assess and reassess a patient’s abilities around using a prescribed device

• Choose dosage regimes that use fewer devices

“Several of the above strategies can be achieved simultaneously with the use of ‘antiinflammatory reliever’ (AIR) therapy,” the authors write.

“This involves the as-needed (prn) use of combination formoterol/ICS inhalers instead of SABA, with or without regular use of the same inhaler as maintenance. This is now the preferred strategy in New Zealand and

international adult asthma guidelines and is an option in Australian guidelines.

“When formoterol/budesonide in a DPI is chosen for this purpose, over 90% of the carbon footprint can be saved due to a reduction in use of salbutamol pMDIs, reflecting not just the use of less-polluting inhalers but also improved asthma control.

“Further, prn-only use in mild asthma likely modestly reduces plastic waste compared to regular ICS maintenance, due to using fewer doses, while achieving equivalent clinical outcomes”.

In Australia, we use pMDIs a lot more than in many other countries with similar populations. Despite guidelines suggesting a single combination inhaler as preventer and reliever for adolescents and adults (not children), most continue to use separate inhalers, the statement says.

Dry powder inhalers (DPIs) and soft-mist inhalers (SMIs) have a 100-200-fold lower carbon footprint than pMDIs, but pMDIs are available over the counter and the PBS only covers DPI terbutaline when the patient can’t use a pMDI.

“This is despite the absence of evidence that one device type is superior to the other at a population level,” the statement says.

“The reduction in a person’s annual carbon footprint for a regular pMDI user changing from a pMDI to a DPI is similar to changing from a petrol to hybrid car or from a meat-eater to a vegetarian.”

Some pMDIs – Airomir and Autohaler – use less HFCs than others. Ventolin and several pharmaceutical companies, including Chiesi, AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline, have promised to produce lower emission devices which could be available as early as next year.

Importantly, switching devices has to be a shared decision. If a patient isn’t comfortable with a new device, that can lead to loss of disease control and even greater carbon footprint, TSANZ warns.

Proper disposal of devices also plays a part. Reusable devices are still uncommon, but the plastic body of SMIs can now be kept for several months, with only the drug-containing canister replaced monthly.

Some pMDI devices have dose counters, so consumers don’t throw them out too early, but “even fully used pMDIs contain residual propellant that will eventually leak into the environment,” the statement says.

Disposal through the National Return and Disposal of Unwanted Medicines (NatRUM) program, rather than in landfill, reduces the environmental impact by using high temperature incineration.

Reducing the environmental impact of inhalers is of course a team effort, the authors note. It involves the development of alternative devices, regulators including environmental considerations in approval processes, pharmacists providing device technique education, government providing safe disposal and recycling schemes, manufacturers reducing packaging, and consumers managing their disease and disposing of inhalers properly.

Respirology, 13 November 2024

Covid remains our biggest acute respiratory killer, being implicated in 4056 deaths this year to August, compared with 851 for flu and 380 for respiratory syncytial virus.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics reported these numbers of “acute respiratory associated deaths”, meaning ones where a virus either caused a terminal complication or contributed significantly to the death.

Of the 4056 covid-associated deaths, 62 were in Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander people, lower than in the same period last year (92) and 2022 (204).

There were 3177 deaths due directly to covid this year to August, compared with 4597 for the whole of last year and 10,309 in 2022.

Of these, 223 (7%) were in people under 70 and 56 (1.7%) were in people under 60.

Noting that the numbers are provisional and likely an underestimate, the ABS said that between January and July, deaths involving covid were 18% lower than last year and 60% lower than in 2022.

Flu-associated deaths this winter were about double those of last year, similar to those in 2017 and about 20% lower than in 2019, a particularly bad flu year. RSV-

associated deaths were 50% higher than last year and double those of 2022.

The Covid-19 Response Inquiry report released last month noted covid’s disproportionate impact on the elderly, who not only accounted for the great majority of deaths but also “experienced extreme social isolation”, due to the choice to avoid interactions or because of visitation bans enforced in aged care facilities.

Our residential aged care population were better protected early on by population control measures than their counterparts in other countries. “Up to early 2022, 1 per cent of the total number of Australian aged care residents died

of covid-19 associated illness, compared to Sweden (8 per cent), Scotland (13 per cent), and the United States (13 per cent),” the report says.

Nonetheless, in 2022, our worst year for covid mortality, almost 90% of the deaths were in people 70 years and older.

Since 2020, when the lack of outbreak preparedness and emergency planning in the aged care sector became stark, the government has developed half a dozen new guidelines and established several formal bodies and offices.

The flawed vaccine rollout “did not meet a single key target for vaccinating older Australians, either in or out of residential aged care facilities”, the report says.

Environmental factors may be contributing to higher allergy rates

AMANDA SHEPPEARD

Australian researchers have found a link between exposure to higher levels of air pollution as a baby and having a peanut allergy throughout childhood.

And they say policies aimed at tackling poor air quality could potentially reduce the prevalence and persistence of peanut allergies.

The research, led by Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI) and the University of Melbourne, has been published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology and was touted as the first study to explore the link between air pollution and challenge-proven food allergy over the first decade of life.

While the research reported exposure to poorer air quality from infancy was associated with increased odds of developing a peanut allergy and having the allergy persist across the first 10 years of life, the same association was not seen for egg allergy or eczema.

The research included 5276 children in Melbourne from the HealthNuts study, recruited at age one and followed up at four, six and 10 years. The researchers used estimates of the annual average concentration of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) at each

LINCOLN TRACY

participant’s residential address at the time of each follow up.

MCRI’s Associate Professor Rachel Peters said the study found that higher levels of air pollution were a risk factor for the development and persistence of peanut allergies – despite Melbourne having generally good air quality compared with international counterparts.

“The rise in allergy prevalence has occurred at a similar time to increased urbanisation, leading to the belief that environmental factors may be

contributing to high allergy rates,” she said.

“Eczema and food allergy most often develop in infancy. Both immune conditions can naturally resolve over time, but for some they can persist throughout adolescence and into adulthood.

“This is the first study to use an oral food challenge, the gold-standard of food allergy diagnosis, to investigate the relationship between food allergy and air pollution.”

University of Melbourne researcher Dr Diego Lopez said the co-exposure of peanut allergens in the environment and air pollutants could be increasing the allergy risk.

“Air pollutants have an irritant and inflammatory effect that may boost the immune systems pro-allergic response, potentially triggering the development of food allergies,” he said.

“However, the underlying mechanisms of how air pollution increases the risk of a peanut allergy, and why eczema and egg allergy aren’t impacted in the same way, need to be explored further.”

The authors acknowledged that results from previous studies into air pollution as a risk factor for eczema in infants and children were mixed.

“[A] study done in a similar low-pollution setting in the Netherlands also reported little evidence of an association between these air pollutants and eczema in eightyear-old children,” they wrote.

“Given this lack of association, it is unlikely that eczema acts as a mediator in the association between air pollution and food allergy. In addition, the inconsistent results in the literature may also be due to variations in the diagnostic criteria for eczema in various nations, temperature, humidity, and the method used to measure air pollution (i.e., static ground-level monitoring vs satellite-based estimations).

“Furthermore, different types of air pollutants exist and are exposed to humans in different proportions and at varying levels throughout the world.”

Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 23 October 2024

New European research suggests miscarriage and the use of fertility treatment are more common in women with asthma. Systemic inflammation may interfere with reproductive organs and potentially affect pregnancies.

Asthma commonly affects women of childbearing age. While previous research has shown it takes asthmatic women longer to get pregnant than those without asthma, few of these studies have included or focused on women who have failed or had difficulty getting pregnant.

Now, a new cohort study, presented at the recent European Respiratory Society congress in Vienna, reports a greater

proportion of women with asthma miscarry and use fertility treatment than women without asthma.

The researchers tracked the reproductive outcomes for over 750,000 Danish women for a median 11 years. Individuals who repeatedly redeemed prescriptions for anti-asthmatic drugs were deemed to have asthma.

A greater proportion of women with asthma experienced a miscarriage (17% versus 15.7%) and used fertility treatment at some point of their pregnancy journey (5.6% versus 5%).

Researchers also observed an association between disease severity and the fertilityrelated outcomes but couldn’t pin down what explained their findings.

“The more severe the asthma and the more flare-ups the women experienced,

the more likely they were to need fertility treatment,” said study author Dr Anne Vejen Hansen.

“Why this is, is not clear. It might be related to systemic inflammation throughout the body, including women’s reproductive organs.”

However, asthma was not seen to impact the likelihood of having a live birth in women who were able to fall pregnant. That is, the proportion of pregnant women with and without asthma who went on to have a live birth was the same (77%).

Professor Lena Uller, head of the respiratory immunopharmacology research group at Lund University in Sweden, was reassured to read that the live birth rate did not differ between women with and without asthma.

But Professor Uller, who was not

involved in the new study, emphasised the importance of managing asthma in women of childbearing age.

“Women with asthma should take into consideration potential reproductive challenges in their family planning. If women with asthma are worried about their fertility, they should speak to their doctor.

“The fact that the more severe the asthma, the more the problems with fertility, suggests that uncontrolled asthma is the problem and we should be helping women to get their asthma under control.”

Dr Vejen Hansen and her collaborators are now planning to explore the effects of asthma on fertility in males to determine if similar associations to those reported here are observed.

European Respiratory Society Congress

about colleagues with AHPRA and using personal data in medical research.

New privacy laws may restrict the ability of doctors to do routine collections of family medical history and sharing of specialist reports, with the AMA calling for healthcarespecific carve-outs.

The government is looking at introducing a statutory tort for serious invasions of privacy as part of an update to the Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2024, something which has been on the table since 2014.

Australia is a relative outlier in not having a tort law – that is, a recognised protection from wrongful conduct that gives claimants a right to sue for compensation – relating to breaches of privacy.

These already exist in the UK, Canada and New Zealand.

The proposed tort covers two types of privacy invasions: intrusion upon seclusion and misuse of private information.

It’s this second part, which includes the unauthorised collection or disclosure of personal information like health records, that has the AMA concerned.

“The Privacy Act provides quite a few exemptions that currently protect healthcare providers, but they don’t apply under this new tort,” AMA vicepresident Associate Professor Julian Rait told Allergy & Respiratory Republic

“We think there’s a need for further amendments, because otherwise doctors, other health practitioners and medical researchers could be unfairly involved in litigation or class actions as a result of quite routine sort of conduct.”

Crucially, the tort would operate independently of the rest of the Privacy Act, which itself specifically permits the handling of personal health information for health and medical research.

This opens up the risk of doctors being sued under the tort even though they have complied with the Privacy Act

Specific examples cited by the AMA were collecting family history or reports from other specialists without express patient consent, disclosing health information to family members or authorities, raising concerns

“[Doctors] frequently receive information from other specialists about a patient without always obtaining consent,” Professor Rait said.

“That’s allowed under the privacy legislation and basically is a common practice

that’s important in terms of how specialists interact and care for people, but it’s not protected under the new statutory tort.”

In order to sue, there has to have been a reasonable expectation of privacy and an intentional or reckless invasion of that privacy which was serious in nature.

QUT law researcher Dr Lisa Archbold, whose work aligns with the Australian Centre for Health Law Research, told ARR there were sufficient safeguards within the design of the tort to address some of the AMA’s concerns. “There has to be a reasonable expectation of privacy … which would take contextual things [into

account], which include where the information has been disclosed,” she said.

“The thinking around it would be different, obviously, in a medical setting [compared] to some other setting.”

There are also four statutory defences that defendants can use, one of which is that the

*Improvement in health-related quality of life (SGRQ). Mean change from baseline at week 24 in SGRQ total score: TRELEGY Ellipta OD (100/62.5/25 mcg) -6.6 units vs Symbicort BD (400/12 mcg budesonide/ formoterol) -4.3 [difference -2.2 units (95% CI -3.5, -1.0); p<0.001]1

TRELEGY Ellipta Indication: Maintenance treatment of adults with moderate to severe COPD who require LAMA+LABA+ICS. Not indicated for initiation in COPD. 2

SCAN QR CODE TO SEE FULL TRELEGY ELLIPTA PRODUCT INFORMATION

defendant reasonably believed the invasion of privacy was necessary to prevent or reduce a serious threat to a person’s health, life or safety.

“There are lots of safeguards within the tort to protect those legitimate and necessary activities that would be occurring in the medical sector,” she said.

Safety: In FUFIL, the two most common adverse events for TRELEGY Ellipta and Symbicort Turbuhaler were nasopharyngitis (7% vs 5%) and headache (5% vs 6%). Adverse events of special interest included cardiovascular effects (4.3% vs 5.2%) and pneumonia (2.2% vs 0.8%).1

Please review Product Information for Information on other Precautions and Adverse Effects. 2

PLEASE REVIEW PRODUCT INFORMATION BEFORE PRESCRIBING.

Product Information can be accessed at www.gsk.com.au/trelegy or by scanning the QR code.

PBS Information: COPD (100/62.5/25 mcg presentation only); Authority Required (Streamlined). Criteria apply. Refer to PBS for full information.

Study design: FULFIL was a randomised, double-blind, parallel group, multicentre, controlled trial comparing TRELEGY Ellipta 100/62.5/25 mcg OD and Symbicort 400/12 mcg BD in patients with moderate to severe COPD (n=1810). The co-primary endpoints were change from baseline in trough FEV1 and SGRQ at 24 weeks. Mean change from baseline in trough FEV1 at 24 weeks: TRELEGY Ellipta 142 mL vs Symbicort Turbuhaler -29 mL [difference 171 mL (95% CI 148, 194); p<0.001].1 The SGRQ is a validated disease-specific health status assessment for use in asthma and COPD, and a reduction of 4 units or more from baseline is considered clinically meaningful. 3 Contraindications: Severe milk protein allergy or hypersensitivity to any of the ingredients. Dosage: One inhalation once daily. After inhalation, rinse mouth with water without swallowing. 2 Abbreviations: BD, twice-daily; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CI, confidence interval; FEV 1 , forced expiratory volume in 1 second; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta2 agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; OD, once-daily; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. References: 1. Lipson DA et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196:438-46. 2. TRELEGY Ellipta Product Information. 3. Jones PW. COPD. 2005;2:75-9. For more information on GSK products or to report an adverse event involving a GSK product, please contact GSK Medical Information on 1800 033 109. GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd ABN 47 100 162 481, Melbourne, VIC. Trademarks are property of their respective owners. © 2024 GSK group of companies or its licensor. PM-AU-FVUADVR-240001 Date of approval: July 2024.

Research suggests this drug can safely sustain weight loss and glycaemic control

LINCOLN TRACY

Along-term study of tirzepatide in prediabetes and obesity suggests people can keep weight off and remain diabetes-free for years, with a serious adverse event rate similar to placebo.

GLP-1 receptor agonists and glucosedependent insulinotropic polypeptide drugs – such as tirzepatide and semaglutide – have been shown to be incredibly effective treatments for weight reduction, glycaemic control and a whole host of other things in the short term, but there is a constant desire for more long-term safety and efficacy data.

Now, a new study that investigated the efficacy and safety of tirzepatide in people with both obesity and prediabetes over three years reports that, compared with placebo, patients treated with tirzepatide had a 94% reduction in the risk of developing type 2 diabetes while losing up to 20% of their weight.

The findings were published in the New England Journal of Medicine

Professor Elif Ekinci, director of the Australian Centre for Accelerating Diabetes Innovations, said it was equally important to see that patients derived significant health benefits above and beyond sustained weight loss.

“These findings underscore the critical role of long-term therapy in achieving and maintaining weight reduction and associated health benefits,” she said.

Researchers recruited over 1000 patients with both obesity (a BMI of at least 30, or at least 27 with one or more obesity-related complications) and prediabetes (based on the results of at least two tests e.g., glycated haemoglobin level, fasting serum glucose level or serum glucose level as part of an oral glucose tolerance test) as part of the SURMOUNT-1 study, an international, doubleblind randomised controlled trial.

The average age of included participants was 48.2 years. At baseline participants had a mean weight of 107.3kg, and the average BMI was 38.8. The recruited sample was predominantly female (63.9%) and White (73.4%).

Patients were randomised to receive weekly subcutaneous injections of 5, 10 or 15mg of tirzepatide – or placebo – for 176 weeks. The treatment period was followed by a 17-week safety follow-up period. All patients also received a lifestyle intervention consisting of counselling sessions with a dietician, a caloriedeficient diet and a minimum of 150 minutes of exercise per week.

Two-thirds of patients remained enrolled in the trial to the end of the safety observation

period, and a similar number adhered to the assigned regimen of tirzepatide or placebo injections.

After 176 weeks patients in the 5, 10 and 15mg tirzepatide groups lost, on average, 12.3%, 18.7% and 19.7% of their baseline body weight, corresponding to an average weight loss of 12.4, 20.0, and 21.4kg. In contrast, the placebo group lost 1.3% (0.9kg) of their baseline body weight.

Less than 2% of patients in each of the tirzepatide groups went on to develop type 2 diabetes, compared with 13.3% of patients who received the placebo. This translates to an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.07 of developing type 2 diabetes after receiving tirzepatide.

A greater proportion of patients receiving tirzepatide also developed normal blood glucose levels by the end of the treatment period (89.9% of the 5mg dose group, 91.2% of the 10mg dose group and 93.3% of the 15mg dose group) compared to placebo (58.9% of patients).

The researchers highlighted that simultaneously targeting both weight and glycaemic control was important in preventing the progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes, with additional mediation analyses suggesting that up to half of the effect of tirzepatide on delaying the onset of type 2 diabetes could be attributed to the medicationinduced weight loss.

“[Drugs like tirzepatide] improve glycaemic regulation through multiple mechanisms, including direct effects on glucose-dependent insulin resistance through centrally mediated body weight reduction,” they wrote.

“These results highlight the sustained metabolic health benefits that may be attained

“These findings underscore the critical role of long-term therapy in achieving and maintaining weight reduction.” ,

Professor Elif Ekinci

with anti-obesity medications that combine proximal effects on islet function with longterm weight reduction that increases insulin sensitivity and reduces beta-cell workload in persons with prediabetes and obesity.”

Patients in the tirzepatide group also displayed reductions in waist circumference, blood pressure and lipid levels compared with the placebo group, as well as improvements in self-reported mental and physical health (as measured by the 36-item Short Form Health Survey [SF-36]).

However, as other emerging studies have demonstrated, the beneficial effects of

tirzepatide disappeared once the patients stopped their injections.

Researchers estimated that patients regained 7% of their pre-treatment body weight during the 17-week safety follow-up period, and that 16% of patients reverted from having normal glucose levels back to levels that were indicative of diabetes.

“Collectively, these findings support the concept that to maintain weight reduction and glycaemic improvements, therapies would need to be continued long-term, as is done for other chronic diseases,” they concluded.

Constipation, nausea and diarrhoea were the most commonly reported side effects, with the latter two complaints affecting patients during the dose escalation period of the study.

Serious adverse events – including cancer, pancreatitis, cardiovascular events and gallbladder disease – occurred in 13 to 15% of patients receiving tirzepatide and in 12% of patients receiving placebo.

The TGA approved tirzepatide “for the treatment of adults with insufficiently treated type 2 diabetes mellitus as an adjunct to diet and exercise” either “as a monotherapy where metformin is not tolerated or contraindicated” or “in addition to other medicinal products for the treatment of type 2 diabetes” almost two years ago.

Last year, the PBAC rejected Lilly’s application for tirzepatide to be added to the PBS, expressing concerns around the economic analyses and questioning whether it had a greater effect on weight loss and glycaemic control compared with semaglutide. It has now reviewed a second submission. NEJM, 13 November 2024

checking the output of the tool.

“That is a very, very concerning issue, because [those notes are] your record and you will be anchored to that record.

“It will not be a defence to say that it was produced by an AI scribe.”

She cited one case where a physician was conducting a consult ahead of a plastic surgery and had run through the complete list of risks, including fat necrosis, nipple necrosis and various other conditions.

Because of this, Ms Pickett said, patient consent needed to be obtained three times: once to cover the privacy aspect of collecting patient data, once for the act of having a device “listen” to the consult and once for the action of using the algorithm to turn a conversation into notes.

OLOPATADINE HYDROCHLORIDE + MOMETASONE FUROATE MONOHYDRATE Australia's fastest growing prescription nasal spray for relief from the symptoms of allergic rhinitis†3

*Combination nasal sprays are a first-line treatment option for persistent and/or moderate-severe allergic rhinitis as per ASCIA guidelines.2

†Based on IQVIA™ National sales audit data (Australian Pharmaceutical Index) in retail pharmacy for S4 nasal corticosteroids without anti-infectives (R01A1), Volume and Value Moving Annual Total (MAT) for the past 3 MATs from July 2021 to July 2023. Ryaltris launched in July 2020.

Dr Michael Gliksman

Dostoyevsky said: ‘Tyranny is a habit, it has its own organic life, it develops finally into a disease’

It seems that in its latest examination of the medical profession by the Medical Board of Australia (MBA), yet another aspect of what we dreadful medical doctors are up to has been uncovered. This time it is the turn of the worst of us, the over 70-year-olds, to be dealt with, for according to the latest Medical Board of Australia’s MBA) musings contained within its 93-page Consultation Regulation Impact Statement (CRIS):

“…doctors have a reputation as reluctant patients, and the Board is concerned that doctors do not always seek the care they need. This is a particular issue for late career doctors (those aged 70 years and older), given that health challenges escalate with age. There is also strong evidence that there is a decline in performance and patient outcomes with increasing practitioner age, even when the practitioner is highly experienced.”

In my opinion that statement, at best misleading for want of the MBA’s claim of “strong” evidence for their allegations about our “reputation”, is a clear indication that it has already made up its mind action is necessary, and that any consultation with the medical profession is window dressing.

The justification relied on by the MBA is in large part drawn from a study conducted in 2018 by Thomas et al. That study examined 12,878 notifications

I do not believe AHPRA or the MBA possesses the competence, impartiality, or the ethical capacity to use such highly personal information only for its stated purpose. ,

lodged with AHPRA between 1 January 2011 and 31 December 2014, including a cohort aged more than 65 years, the majority of whom are unlikely to still be in practice.

The results found older doctors had notification rates 1.4 times higher than for doctors aged 36 to 65 years (90.9 compared with 66.6 per 1000 practitioner years). Notifications resulting in regulatory action such as a reprimand, fine or imposition of conditions were 1.5 times higher among doctors aged 65 years and older.

It is on these figures the MBA justifies its proposal to subject all registered doctors 70 years and older to highly personal cognitive and physical examinations and, as if to rub salt in the wound, expect them to pay for it themselves.

There are several reasons to doubt the veracity and applicability of the figures the MBA relies on.

The MBA/AHPRA CRIS indicates that of the 485 complaints received in 2022-3 regarding 6975 registered doctors over 70 years, nearly 80% led to no further action. The corresponding contemporaneous findings in the under 70s? Approximately 5130 complaints were received regarding the 125,391 doctors registered in that age group in the same period.

This gives a relative risk of 1.70 of a complaint (meritorious or otherwise) being lodged if a practitioner is over 70 years, a little higher than the RR reported by Thomas et al.

Out of the 5130 complaints made against registered practising doctors aged under 70 years in 2022-23, an estimated 708 doctors had adverse regulatory findings made against them. The penalties included fines, conditions on practice, suspensions and deregistration.

Out of the 485 complaints made against practicing doctors aged 70+ years in the same period, an estimated 90 doctors had adverse regulatory findings imposed on their practice. Of those 90 doctors that had conditions imposed on their practice, not one received fines, reprimands, or suspension of registration (the more stringent actions), unlike the under 70 years cohort.

Not one!

That, dear colleagues, is what the MBA considers sufficient reason to burden an entire cohort with the product of an ageist assumption, let alone the added burden to be visited on those doctors expected to conduct the examinations.

But that doesn’t tell the whole story.

Relying on relative risk alone to assess population risk (absolute risk), especially when based on small numbers relative to the populations being compared, is known to overstate population risk. Unfortunately, this basic epidemiological and statistical fact appears unknown to the MBA’s favoured researchers.

As the Australian Senior Active Doctors Association (ASADA) submission to the MBA CRIS puts it:

“Reporting relative rates of unsubstantiated complaints without reference to absolute numbers and outcomes serves to grossly overstate issues. For example, of what meaning is it to know that unsubstantiated complaints for one group are 1.7 times that of another group, if we know nothing of the veracity of the complaints, or the actual outcome of the complaints?”

What is the absolute risk difference of proven regulatory trespass as determined in a tribunal hearing, not simply an unsubstantiated complaint lodged with AHPRA, when patients are treated by over 70-year-olds are compared to the under 70-year-old doctors?

That calculation tells a very different story to the one being promoted by the MBA.

Ninety complaints against 6975 doctors older than 70 years resulted in regulatory penalty, none in the more serious categories. Seven hundred and eight complaints against 125,391 younger than 70 years resulted in regulatory penalty, including some in the more serious categories, including deregistration.

Applying these figures, the absolute risk difference is 0.726% and if the over 70s had the same risk as under 70s, then one would expect 39 adverse findings among

the older cohort compared to the 90 experienced. This in turn yields an excess of 51 (but lesser) adverse findings in the older cohort of 6975 registered practicing older doctors, or 0.7% per 100 doctors.

So that’s what the MBA/AHPRA relies on to promote its ageist agenda. What does the MBA think it’s preventing with their CRIS proposals? How can the MBA be so unaware, if indeed it is?

Perhaps the answer can be found in the MBA’s favoured researchers’ statement:

“Our study adopted a regulator’s perspective.”

And in Thomas et al:

“Partnerships between researchers and regulators can enable new insights into patient safety risks and inform regulatory practices.”

The apprehension of bias must be obvious to all impartial observers.

The medical history that forms part of the triennial mandatory examination proposed as detailed in the MBA’s CRIS document is intrusive and extends into areas well beyond the purpose stated. Further, there appears no attempt by the MBA or by its “go-to” researchers to validate the cognitive tests they propose be used for their fishing purposes.

The feedback I receive from colleagues suggests some have brought forward retirement plans because of the MBA’s poorly justified recent changes to CPD requirements. I wonder how the politicians who direct AHPRA/MBA policies will react to the likely loss of doctors from the medical workforce resulting from the regulators’ poorly researched imposts?

To assess the true effect of what the MBA proposes, one would need to conduct a prospective study that shows clinical and statistically significant adverse differences in patient outcomes for practitioners with, versus without any measured impairment especially if, as they propose, the MBA uses assessment tools not validated for that purpose. That prospective study has not been done.

None of the cognitive screening tests the MBA proposes using have been evaluated to discover what scores would determine the doctor’s capacity to practice, and the Board has shown no evidence of interest in validating the tests for that purpose.

The American Medical Association in 2015 noted: “the effect of age on any individual physician’s competence can be highly variable”

In 2018 it withdrew its support for testing physicians cognitively at 70 years of age. None of this is mentioned in the MBA’s CRIS document.

The detailed submission made by ASADA addresses many more shortcomings including in data gathering and presentation, miscalculation of numbers, and biases in the MBA’s CRIS document. They are too numerous to detail here so I encourage you to read the CRIS document and ASADA’s submission in response, to obtain a more complete picture on what rotted foundations the MBA/AHPRA’s latest regulatory edifice is built.

As a result of these considerations, I do not believe AHPRA or the MBA possesses the competence, impartiality, or the ethical capacity to use such highly personal information only for its stated purpose.

I would not consent to being subject

,It is on these figures the MBA justifies its proposal to subject all registered doctors 70 years and older to highly personal cognitive and physical examinations and, as if to rub salt in the wound, expect them to pay for it themselves.

to such an examination without robust, independent validation of their predictive ability and with iron-clad guarantees as to its privacy and its non-use for other purposes.

If the MBA’s proposal remains unchanged, I suggest my over 70-year-old medical colleagues should do likewise.

Taking the time necessary to conduct such a study, presuming the MBA and its preferred researchers possess the willingness and ability to do so competently and impartially, lies well beyond the three-year attention span of the state and federal health ministers who direct the policy behaviour of AHPRA and therefore the MBA, but all is not lost. Their proposal can only work if we doctors agree to perform the examinations.

The Australian Constitution prohibits the use of the medical services power to authorise any form of civil conscription (subsection 51 [xxiiiA], and thus it would be difficult if not impossible for the MBA to lawfully compel doctors to conduct assessments of questionable validity in this setting.

As a fully registered (for now) non-GP specialist, I will not be doing so without such evidence.

It is also clear that the MBA has not conducted (or if it has it has chosen not to reveal the results) a cost-benefit analysis on their latest proposal, just as they did not when changing CPD requirements without good evidence as to benefit. How many competent, highly experienced doctors will bring forward their retirement because of these changes? Where will the impact fall more heavily, in metropolitan or in rural/remote areas? Will the MBA’s decision to bypass the medical colleges and speed through the registration of overseas trained doctors from certain countries be enough to counter any further Board-aggravated shortage?

Does the MBA believe leaving large tracts of the country without relatively easy access to medical coverage is in the interest of patient safety? If so, why not simply deregister us all. There is a ready supply of pharmacists, naturopaths, chiropractors and herbalists keen to replace us.

Regular health check-ups for all doctors and targeting assessments based on specific performance issues would provide a more equitable and effective strategy for safeguarding patient care. This would be consistent with the Medical Board of Australia’s Code of Conduct that requires “all doctors to have their own general practitioner (GP) to help them take care of their health and wellbeing throughout their working lives”

The Medical Board of Australia should reconsider its approach and adopt practices that uphold principles of fairness and evidence-based regulation, rather than implementing poorly researched mandates that may lead to discrimination, unnecessary damage to or destruction of medical careers, and the loss of valuable experience in the medical field.

Dr Michael Gliksman is a physician in private practice in Sydney and a past vice-president and chair of Council of the AMA (NSW), and a past federal AMA councillor. He has never been the subject of a patient complaint to any regulatory body.

I am

very grateful to know voluntary assisted dying is being practised in NSW with such professionalism and humanity

We all have stories about the failings of our current health system. We can all think of patients who we have referred to some tertiary service only to have them receive substandard or inadequate care.

This is not such a story.

This is the story of my first encounter with a voluntary assisted dying service. It’s the story of my patient, Kate – the mother of a good friend of mine, who – as the wise, pragmatic and no-nonsense 84-year-old country woman she was – decided enough was enough.

And it’s the perfect example of how well a system can work when it’s designed well and adequately and appropriately staffed. Kate should never have been my patient. For one thing, she lived more than 450km from me in country NSW.

But in “a series of unfortunate events” she had to see specialists in Sydney and I became her “Sydney” GP.

Over a period of a couple of years –a couple of years that included a few orthopaedic operations and a couple of respiratory infections – she became increasingly short of breath and developed a chronic cough.

Long story short – Kate was diagnosed with progressive pulmonary fibrosis. And it seemed the progression was pretty relentless. Initial, standard treatment didn’t help and she was put on a trial mab, but it gave her such dreadful diarrhoea she stopped it.

By the time she headed back to her own home in the country, she had portable oxygen and had been given the prognosis of “terminal” and we (Sydney specialists, family and me) were all trying to engage local palliative care services.

This is not a criticism of this town or the local health district – it is simply the reality of rural medical services – there just aren’t enough people there.

In fact, there was one palliative care nurse to cover some enormous area. The local GP had a three-week wait list and didn’t do house calls.

The nearest palliative care physician worked out of a larger district hospital over one hour away – lovely man – who organised meds and put Kate in their system, but Kate couldn’t even hang clothes on the line, let alone attend medical appointments

Dr Linda Calabresi

an hour away. It was never going to be enough. It took less than a couple of months for even fiercely independent Kate to realise this wasn’t working. She put up the white flag and went to live and be cared for by her daughter and son-in-law on the Central Coast.

The referral to the new local palliative care service was emailed that day and included Kate’s very emphatic instruction that she wanted to investigate the VAD option.

Within two days of Kate arriving at her daughter’s place she was visited by the palliative care team, she was assessed, and daily nursing services were commenced. Within a week she had been contacted by the VAD team and visited personally by a team member to explain the VAD process in detail.

Now that she was living with her daughter she was far less anxious and panicky than she had been when living alone in the country, but she was adamant – this slow suffocation was no way to live.

The assessments occurred over a few weeks, all done at home. Both Kate and her daughter could not speak highly enough of all the health professionals that visited them over this time – especially those associated with the VAD service.

By all reports they were not only incredibly warm, empathetic and

unhurried, but they always made sure Kate knew she had all the power. They could determine she was eligible for VAD and even dispense the oral medication, but it was totally up to her when, how and even if she ever took it.

Kate’s overwhelming state of mind at this time was one of peace. The knowledge that she was not going to have to suffer more than she could bear and that she could dictate if and when it was time to go was an absolute gift.

In the end, less than two months after first contacting VAD services, Kate was determined for VAD and chose the IV option. She died there, in her daughter’s house, surrounded by her family. She just went to sleep and then stopped breathing. By anyone’s standards – it was a good death.

I’ve always been a supporter of VAD in principle but, to be honest, I have been less sure of how the process would work in the real world. I suppose shades of the debacle of medicinal cannabis prescribing spring to mind.

But I’ve got to say, this experience – albeit all second-hand – has been enlightening and, in a way, comforting.

All the appropriate checks and balances were done according to the strict criteria of the legislation but the process was timely, personal, respectful and seemingly devoid of needless and frustrating bureaucracy.

I’ve always been a supporter of VAD in principle but less sure of how the process would work in the real world… This experience … has been enlightening and, in a way, comforting.

Here in NSW, legislation allowing VAD only went through in November 2023, the last state to approve it. In the first three months about160 people died this way, and over 500 had made a first request.

On a recent webinar hosted by my local PHN, it was estimated that here in NSW we can expect that 1.5% of all deaths will involve VAD.

To my mind, the benchmark for the NSW VAD process has been set very high. Hopefully there is sufficient manpower, enthusiasm and funding to maintain this high standard of care as demand grows. The signs are good.

In my extensive experience (of one) this whole system, from the legislation through the registration to the delivery, has been well thought through and implemented with wisdom and clarity of purpose. I know Kate was incredibly grateful to have had this option available to her. I can think of so many patients in the past who would’ve been similarly grateful had they had the opportunity.

For me too, I am very grateful to know such an emotionally fraught and potentially confronting area of medicine is being practised with such professionalism and humanity. We are lucky.

Dr Linda Calabresi is a Sydney GP and editorin-chief of The Medical Republic.

Dr Lisa Kenway

A creative pursuit may be the best way to manage the moments and memories that haunt

Almost 20 years ago, a few years after I qualified as a specialist anaesthetist, a patient in my care was paralysed after major surgery.

Although the exact cause of their deterioration was never clear, and despite maintaining a high standard of care throughout the case, my choice of anaesthetic technique may have played a role. I was devastated for my patient and immediately began to ruminate over what may have gone wrong.

Afterwards, I questioned my right to work as an anaesthetist. I’ve battled imposter syndrome my whole life, but this was next level. I wasn’t just an imposter; I might have inadvertently caused material harm to another person, and that knowledge almost destroyed me.

It took me years to recognise that I too was a victim of this medical error, and that I wasn’t alone.

My initial response to my patient’s disastrous complication was by the book: I apologised and engaged in open disclosure, participated in family meetings, presented the case to my colleagues, reported the incident to my medical defence organisation and spoke with hospital administrators.

Although necessary and appropriate, these activities were gruelling and humiliating, only amplifying my self-doubt. Rather than addressing my emotional response at the time, I buried it and carried on.

My husband was working long hours, I had a five-year-old and a two-year-old, we’d recently moved back into our home after renovations, and we had no nearby family to help. I barely had time to scratch myself, let alone recognise that I might have been suffering from what researchers have coined “secondvictim syndrome” – a term used to describe healthcare workers who are themselves traumatised when a patient is harmed due to physician error.

There’s a not unreasonable expectation in the community that medical mistakes should be preventable. Doctors are held to a high standard, and we, in turn, expect perfection from ourselves.

Many of my colleagues see complications as personal failings, even though an adverse

outcome is rarely the result of a single mistake. Sometimes no-one is at fault.

After the incident, I doubted my skills, my clinical judgment and my ability to do my job, but because of financial and career pressures, I couldn’t afford to take time off.

Guilt was a constant companion. My sleep suffered. I replayed my actions and their outcome in my head, again and again.

When furniture arrived to fill our newly renovated home, I was reminded of the ramp that had to be fitted to my patient’s house to accommodate their new wheelchair. I changed my practice, gave away challenging lists and toyed with the idea of leaving medicine altogether.

As years passed, my grief was eclipsed by a fear of going to court. I’d previously followed medical negligence cases in the media with macabre fascination, wondering how the system could protect shoddy practitioners. But imagine how it would feel to be held to public scrutiny like that as a conscientious new specialist.

Ultimately, my patient chose not to take legal action – I still wonder if my open disclosure influenced their decision – yet years later, well after the statute of limitations has passed, the apprehension remains.

A 2013 meta-analysis found that up to 43% of doctors suffer from depression, anxiety or PTSD in the weeks following an adverse patient outcome, with some even committing suicide. Even more physicians are traumatised by events that they witnessed but did not directly cause. Medical practitioners are often exposed

and

to horrific scenes, images and sensations at work that live rent-free in their heads for years.

Traditionally doctors have been taught to remain stoic and professional on the job and to deal with its emotional impact on our own time. But the way we practise, and teach medical students, is beginning to change.

In my hospital, we have instituted a formal mentoring program for anaesthetic registrars, and I’m proud to act as a mentor.

Medical schools are beginning to address practitioner self-care and resilience alongside anatomy and physiology.

Of particular interest to me are the programs that utilise creative writing to explore feelings triggered by the traumatic events that doctors experience at work, because writing was my saviour.

Last year, the University of Melbourne introduced a narrative medicine subject for medical students with the aim of helping students become “more sensitive practitioners, beautiful writers, and advocates for the health of all people”.

The course was inspired by a narrative medicine masters offered by Colombia University in the US. A similar program is offered at Temple University in Philadelphia, which employs Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Michael Vitez in a program that aims to teach medical students how to “give voice to their feelings”.

I eventually found my own way to creative writing.

A few years after my patient went home in a wheelchair, when my children were both at

Many of my colleagues see complications as personal failings, even though an adverse outcome is rarely the result of a single mistake.

school and the chaos of my life had settled a little, I found myself searching for something more – a creative outlet, a road map back to the confident, relaxed woman I had once been.

After trying my hand at organic gardening with mixed success (the brush turkeys won in the end) and knitting (it turns out I’m not very crafty), I decided to try creative writing.

It was immersive, challenging and addictive, and I haven’t looked back. Sometimes I write to process the trauma I experience at work, but mostly these days I write to please myself.

I’m not sure why so many doctors are drawn to creative writing. In my case, the personality traits that led me to study medicine in the first place – empathy, compassion and curiosity –feed and enrich my creative writing.

Interestingly, the act of writing and my engagement with the writing community has, in turn, helped me become a better communicator and a more holistic practitioner and mentor.

Enough years have now passed to reflect on that defining moment, early in my career, with balance and objectivity.

I will always feel grief and compassion for the patient who suffered a life-changing complication, but I also regret the callous way I treated my younger self.

If I’d had the skills, I might have written about it at the time.

Dr Lisa Kenway is an Australian anaesthetist and writer. Her debut novel, All You Took From Me, which draws on her work as an anaesthetist, was recently published by Transit Lounge Publishing.

People deserve differential diagnosis too

“It’s so pure, it’s so strong; though I do admit it came on fast, but I do believe that it can last” – Elphaba and Glinda, Wicked

“Just eating a whole raw tomato, are we?” is what my piss-taking, shit-stirring newbie self said to a fellow paediatric resident in the handover room at 7.58am on a regular day at the Northern Hospital once upon a time.

She looked up, equal parts flummoxed and offended, from munching through a whole bag of gourmet tomatoes at morning handover. What ensued was what polite folk would have called a “spirited debate” on whether it was normal to consume a whole gourmetsized tomato on its own, which then branched into whether it was acceptable if truss, after which the whole handover room got involved and accepted that it was far from forensically psychopathic if they were cherry tomatoes.

First impressions-wise, not a strong prognostic indicator for a future friendship between the two of us. But here we are, 10 years later, best of friends with a standing Wednesday post-clinic dinner (and churros) built into our teeming schedules.

But how does one go from unadulterated loathing to entrenched friendships?

The art of medicine, being an extremely potent conduit to building friendships through the steaming cauldronic mess it provides as the backdrop, also teaches us daily the dangers of “diagnostic inertia”, where a first impression anchors a diagnosis at front of mind, to the neglect of every piece of contradictory new evidence.

It’s not uncommon for us in the field to form a strong first picture of a patient’s condition, persona and family dynamics, just on the interaction at which they first presented.

The danger of this, of course, is the lack of alacrity when the toddler with “viral pneumonitis” and bilateral crackles then turns around and loses their cardiac output and begins to have rigors. What sorcery is this? Must be salbutamol toxicity, and so we cheerily press on, only to find ourselves a few hours later hanging up inotropes and sticking in chest drains for a cheeky staphylococcal pneumonia with effusions.

But how do we safeguard ourselves and keep our objectivity, especially in the face of withering criticism at morbidity and mortality

meetings, when young children typically present in subjective manners?

Is the correct approach to do Q12H CRPs in neonates who have weird-looking rashes, or keep kids of parents with fringe personalities who might throw the management plan out the window another whole week/until 18 years corrected age on the ward for safety?

Is four hours’ observation in emergency a guarantee that someone won’t re-present to the emergency department with worsening wheeze needing PICU later down the track?