Alum Kai Cheng Thom speaks at McGill’s annual Queer History Month keynote

A transgender woman of colour, Thom emphasizes the need to pract ice revolutionary love

Kaitlyn Schramm News Editor

Attendees shed tears of queer solidarity on the evening of Oct. 22 as author and somatics teacher, Kai Cheng Thom, addressed McGill during the university’s annual keynote speech for Queer History Month. The event, ‘Remembering Resilience: Embodying the Queer Legacies in Uncertain Times,’ opened with a land acknowledgement appreciating the night’s rain and emphasizing that humans are not superior to the land they inhabit.

Tynan Jarrett, director of the Equity Team in McGill’s Office of the Provost and Executive Vice-President Academic, then introduced Thom as his previous student at McGill, briefly describing Thom’s activities on campus before commenting on the importance of Queer History Month.

“Queer History Month is more than a celebration. It is a call to honour the lives, struggles, and triumphs [of] those who came before, to connect our struggle to theirs, and to move forward stronger,” Jarrett noted.

Director of McGill’s School of Social Work, Nicole Ives, continued the introduction, outlining Thom’s impressive accomplishments since graduating from McGill.

“[Kai] is [an] award-winning writer, performer, and creative arts facilitator, whose work delves deeply into the themes of revolu-

tionary love, transformative justice, spirituality, and healing from collective trauma,” Ives said. “I know I speak for my colleagues who are here from the School of Social Work, and I speak for myself, saying how thankful we are that she is here to share her vision for how we can transform society into a more socially just and humanist world.”

As Ives concluded the introduction, Thom approached the stage and shared a hug with Ives before addressing the crowd. She began with a prayer centring love: “Love that heals, love that speaks, love that tells the truth, the whole truth, the ugly truth, nothing but the truth, love that sees it all and yet keeps moving anyway.”

Shortly thereafter, Thom admitted her complicated relationship with McGill while offering gratitude for the opportunity to speak at the university. She described the mix of emotions she feels as a trans woman and as a changemaker who has evolved from admiring veteran activists to becoming one of those veteran activists, despite few corresponding societal improvements for the trans community.

Demonstrating her expertise, Thom then led a short somatic practice, instructing the group to find their length, find their width, and find their depth physically within their bodies. She then encouraged attendees to take a moment, breathe, and orient themselves within what they have been noticing about their social landscape. She concluded the

somatic practice, with many participants crying silent tears and loud cries of relief, before continuing to speak on resilience and resistance for queer activists.

“The resilient edge of resistance is a term that comes to us from somatic trauma therapy. It refers to the ability to feel stress and even distress, while remaining grounded, centred, connected, crucially connected,” she described. “And my offer to you about this term resilience, […] is that it can be about resistance having more emotion, actually having more sensation, more feeling, but not in a way that fragments, that leaves us feeling despair, […] [but] in a way that leaves us feeling more connected […] to ourselves. Resilience is not about toughness or being superior to others, and I believe that the great mothers of queer and trans history knew this.”

As her speech concluded, Thom spoke to the feeling of hopelessness common to lifelong activists who fail to see results from their advocacy, quoting Ursula K. Le Guin, who stated that when living under capitalism, its power seems unescapable. But, Le Guin said,

so did the divine right of kings. Thom urged the crowd to remember that human power goes both ways: Any human system can be resisted and changed by human beings. And for human beings to stand strong under pressure and see the change they want to make, she emphasized, they must work together.

“Love survives, love revives, love redeems, love forgives,” she finished.

SSMU LC discusses gender-affirming care insurance, new VP hires, and Fall Referendum

Council hears updates from Black Affairs Commissioner, Chief Offic er of SSMU Elections, and Medical Students’ Society

Devdas Hind Contributor

The Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU) Legislative Council held its fourth meeting of the semester on Oct. 23, with 25 members present.

After the Steering Committee briefly presented a report, SSMU Black Affairs Commissioner Kendra-Ann Haynes gave a presentation. Haynes stated that the Black Affairs Committee is interested in opening a chapter for Black Future Lawyers and expanding the Black Equity Fund to post-

graduate students at McGill.

Next was a presentation from Chief Officer Mike Lee of SSMU Elections. He outlined strategies to increase voter turnout for the upcoming Fall Referendum, including a raffle, flyers, and a stronger social media presence.

“People do vote [when] they feel related to a topic [and] when they feel that things are related to them,” Lee said.

The Conference on Diversity in Engineering (CDE) then presented its request for $25,000 CAD from the SSMU Campus Life Fund to balance its budget. The CDE’s Co-Chair Claire Levasseur stated that sponsors are especially difficult to find this year.

“Three out of the four major [engineering] conferences are being held in Quebec [in 2025], [so] we are all going for the same resources, which has been extremely difficult,” Levasseur reported.

After a unanimous vote in the CDE’s favour, the LC approved the

CDE’s request for funding.

SSMU President Dymetri Taylor then gave an Executive Committee report. Among other things, President Taylor noted that the implementation of a new gender-affirming care student insurance model will be pushed back from the beginning of the Winter 2026 semester to the Fall 2026 semester.

“McGill required roughly six months’ notice to provide information of a secure nature to third parties, [which] is then pushing back implementation of genderaffirming care,” Taylor clarified.

The new hires to the SSMU Vice-President (VP) Finance and VP Internal Affairs positions were next presented to the LC. VP Finance Jean-Sébastien Léger and VP Internal Minaal Mirza both began their roles on Oct. 20.

The Executive Reports continued with SSMU VP External Affairs Seraphina Crema-Black confirming that she will be hosting a Montreal municipal election debate on Oct. 27 in the SSMU ballroom, with confirmed participation from Transition Montréal, Projet Montréal, Futur Montréal, and Ensemble Montréal. The debate will be moderated by McGill’s Associate Provost Angela Campbell. Crema-Black emphasized that there is a form where students can submit their questions for candidates as well.

After Crema-Black spoke, the Medical Students’ Society (MSS) of McGill presented a report. Among other things, MSS SSMU Representative Ling He announced that an emergency MSS General Assembly would be held on Oct. 26 regarding the Fédération des médecins spécialistes du Québec (FMSQ) and Fédération des médecins omnipraticiens du Québec (FMOQ) strikes. The LC concluded by handling a series of motions. Notably, the Council voted unanimously to add Crema-Black and SSMU VP University Affairs Susan Aloudat to the SSMU Board of Directors.

Moment of the meeting:

Chief Officer Lee warned that the consequences of not reaching a quorum of 15 per cent during the Fall Referendum means none of the campaigns on the ballot will move forward.

Soundbite:

“We’re [trying] to e-mail professors of large courses for them to remind students [to vote], [while] identifying faculties and programs with the lowest voter turnouts [to] see how we can make sure the target groups can increase their voting.”

— Lee on additional strategies SSMU is undertaking to help reach quorum.

A record five new clubs were formed within the Medical Students’ Society this semester. (Anna Seger / The Tribune)

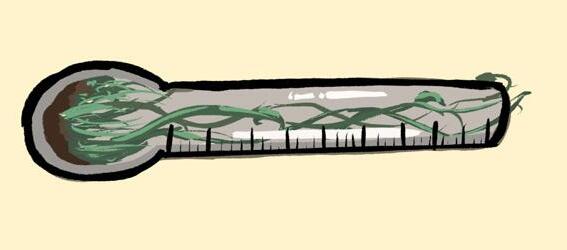

Thom graduated from McGill’s School of Social Work and has worked as a mental health clinician for trans youth. (Alexa Roemer / The Tribune)

Students face delays in accessing student loans and grants during B.C. public worker strike

McGill community discusses disruptions and funding alternatives in response to the strike

Basil Atari Staff Writer

On Sept. 2, the British Columbia General Employees’ Union (BCGEU), one of the province’s largest public sector unions, went on strike until Oct. 26. The strike affected most provincial ministries in B.C., including the Ministry of Post-Secondary Education and Future Skills, which administers student financial aid programs through StudentAid BC. The BCGEU went on strike when negotiations with the B.C. government for higher wages

in future contracts reached an impasse. Until it was resolved, the strike left some B.C. students who rely on provincial student assistance unable to access their student loans and bursaries. According to StudentAid BC’s website, delays in student aid disbursements occurred until the labour dispute was resolved, and access to its online systems remained unavailable during the ongoing labour action.

Most students who rely on StudentAid BC have received their funding for the fall semester, but the few who have not have been greatly affected by the delays. Students who rely on assistance via BCGEU have expressed that the potential for continued delays during labour disputes may cause them more difficulty, especially with upcoming winter semester payment deadlines.

In a written statement to The Tribune, a McGill student who experienced delays to their B.C. student loans during strike negotiations, who wished to remain anonymous, described how McGill can support students under related financial strain.

“I hope that McGill will be understanding of the difficult situation the strike puts students in, and I hope they will

take into consideration that most students who use [StudentAid BC loans] can not seek outside financial support,” they wrote.

In a written statement to The Tribune, McGill’s Scholarships and Student Aid Office encouraged B.C. students who have experienced financial hardship due to delays in government aid to contact the office for assistance.

“We offer one-on-one appointments with Financial Aid Counsellors who can assess individual circumstances and, where appropriate, provide institutional aid in the form of an emergency interest-free McGill loan to help bridge the gap while students [from British Columbia] await their funding,” the Office wrote. “Additionally, students who have requested a fee deferral due to delayed government aid have until the end of November to pay their tuition and fees. If a longer deferral is needed, our office can assist with arranging an extension.”

On behalf of the Arts Undergraduate Society (AUS), Pearce-Tai Thomasson, the Society’s Vice President of Communications, clarified how the AUS has been aiming to help students affected by the ongoing delays.

The AUS also provided a list of resources for students seeking ways to reduce their living costs, in the face of the burden brought on by the B.C. government’s failure to successfully negotiate to end its public sector strikes. The list includes resources for affordable transportation, on-campus food options, and mental health services.

Another student who wished to remain anonymous expressed frustration with the lack of public communication from the McGill Scholarships and Student Aid Office about the BCGEU strike’s effect on B.C. student aid disbursements.

“[McGill] hasn’t been super transparent. [....] They could have sent an email to all of the [affected] students telling them they were addressing this,” they said in an interview with The Tribune. “[McGill] has a delay on payments that you can apply for through the financial aid application […] and there’s [also] emergency funds, […] which are [resources] that the school definitely could advertise [more].”

Students from B.C. who have been impacted by student aid delays can reach McGill’s Scholarships and Student Aid Office by phone at 514-398-6013 or by email at studentaid@mcgill.ca.

“The AUS […] deeply sympathizes with the affected students and are open to sitting down with students struggling with this issue,” he expressed in a written statement to The Tribune. “While our scope remains limited to our constituents, we can provide students with options and help them navigate potential escalation to [the Students’ Society of McGill University] or the Deans within the Arts Faculty Admin. Students concerned can reach out to us using the Arts Public Directory.”

Dialogue McGill uses funding to retain bilingual healthcare pro fessionals $52 million CAD in federal funding fuels hope for Quebec’s anglophone healthcare accessibility

Sofia Vidinovski Contributor

On Oct. 15, the Canadian federal government announced a budget increase of $52 million CAD, allocated to anglophone health services in Quebec. The funds will be distributed between McGill University and the Community Health and Social Services Network over the next five years. These institutions will lead execution, with Dialogue McGill heading the project on the university’s behalf. They will prioritize developing research, language training, and resources tailored to the needs of both anglophone and francophone professionals, staff, and students to support their experiences within the healthcare system. The budget increase will also sustain initiatives to recruit and employ bilingual professionals across the province.

In a written exchange with The Tribune, McGill’s Media Relations Office (MRO) explained how Dialogue McGill will specifically allocate the university’s funding towards building accessible healthcare for anglophones in Quebec.

“Dialogue McGill received a $20.7 million [CAD] grant […] of the $52 million [CAD] that Health Canada allocated,” the MRO wrote. “The money is planned to be useful in supporting initiatives that maintain and build capacity of bilingual health professionals in Quebec’s public sector.”

The

The Office also highlighted Dialogue McGill’s missions and the services it provides specifically to McGill students.

“[Dialogue McGill’s] programs include free French- and English-language training, as well as bursaries for students committed to working in the public sector post-graduation and funding for research projects that examine relationships between language, access to health and social services, and health-related outcomes.”

This is not the first time Canada’s federal government has outwardly supported an increase in anglophone healthcare accessibility in Quebec. In 2024, Quebec Health Minister Christian Dubé announced a government di-

rective that would require patients to provide an English-language eligibility certificate to Quebec’s health networks to receive treatment in English. Only when the federal government pressured the Quebec government did Dubé backtrack on the directive.

McGill students who have engaged with Quebec healthcare, especially in the MiltonParc neighbourhood, have described the experience as strenuous. Amélie Evans, U2 Sciences, outlined her experience as an anglophone patient in a Montreal hospital, highlighting how a language barrier can complicate access to safe healthcare in the province.

“I’ve had moments where language created misunderstandings,” she said in an interview with The Tribune. “For example, during one visit to the hospital, a nurse misunderstood part of what I was explaining about my symptoms because I wasn’t sure how to phrase it correctly in French. It didn’t cause serious harm, but it made me realize how critical it is to have clear communication in healthcare.”

Furthermore, Evans hopes that this budget increase will aid English-language communication in Quebec’s medical system.

“I think the first priority [for funding use] should be expanding bilingual training programs and ensuring every major clinic has at least one English-speaking staff member available,” she stated.

To track the funding’s progress, the federal government of Canada will receive annual reports from the project’s leaders on its outcomes. In an interview with The Tribune, Mark Johnson, spokesperson for Health Canada, explained the measurable outcomes and performance indicators that McGill will use to ensure the budget is effectively applied.

“McGill University [will report] on the number of health professionals who have both enrolled and completed their language training program, the number of bursaries to recent graduates to retain them in the public system in an underserved region in Quebec, as well as research projects and knowledge products that have been produced and offer new data on [official language minority communities] in health,” Johnson said.

Some of the educational institutions BCGEU members work for include community colleges and the B.C. Institute of Technology. (Zoe Lee / The Tribune)

Montreal region currently holds the record for the largest anglophone population in Quebec, with the Eastern Townships holding a close second. (Anna Seger / The Tribune)

McGill hosts ‘Building Bridges: Insights from Hispanic and Latin American Diplomats’ panel

Hispanic diplomats and students discuss foreign affairs and Lati n American culture

Katherine Dale Contributor

On Oct. 24, McGill’s Spanish and Latin American Students’ Association (SLASA) and McGill’s Caribbean and Latin American Studies and Hispanic Studies Association (CLASHSA) collaborated with McGill’s Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures to host the ‘Building Bridges: Insights from Hispanic and Latin American Diplomats’ panel, in honour of Latin American Heritage Month. The event provided McGill students, staff, and community members with dialogue on the field of diplomacy, and on ways to embrace Hispanic and Latin American culture in Montreal through organizations like SLASA and CLASHSA.

In an interview with The Tribune, Sophia Newmann, U3 Arts and Vice President of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at SLASA explained why Latin American cultural groups and heritage months are important to diasporic students at McGill.

“SLASA provides a place of friendship, family, and home,” she said. “When you’re with people of the same ethnic background as you, you are able to share the same food, interests, and worldview. For Hispanic Heritage Month, it is really important to celebrate [Latinx people] because we’re a really unique

group of people who have a unique way of looking at the world.”

SLASA holds a variety of different events throughout each academic year, including reggaeton parties and Spanish-language-learning social gatherings. This fall, in an effort to expand its offerings, the club hosted Oct. 24’s diplomatic panel. The panel was moderated by Víctor Muñiz-Fraticelli, associate professor in McGill’s Faculty of Law, and featured Victor Manuel Treviño Escudero, Montreal’s Consul General of Mexico, Mauricio Baquero Pardo, Montreal’s Consul General of Colombia, Gerardo Ezequiel Bompadre, Montreal’s Consul General of Argentina, and Carlos Ruiz Gonzalez, Deputy Ambassador of Spain in Ottawa.

Throughout the panel, the main points of discussion included what the daily life of a diplomat and their duties look like. The panel participants also described how their experience in Canada differs from their postings in other places, and the most challenging aspects of their profession, like working to build what Treviño described as “bridges of understanding” with host countries.

Bompadre of Argentina spoke about the continuities and changes of the job.

“It is important to find opportunities for your country and your people and to make your country known [where you are posted],” Bompadre said. “Diplomacy has changed

quite a lot, our ancestors of this field had it differently, and now it is less autonomous.”

Specifically, Bompadre noted emergent technological networks as one of the primary changes of the job. In the digital world, diplomats now have more opportunities to receive advice from their nation’s capital on foreign policy decisions.

All four diplomats explained the initiatives they have in place for students, including networks of exchange for undergraduates.

“We found that there is a greater interest for students studying here to come to Spain and study for a year,” Gonzalez said. “The [Spanish] embassy tries to ease the path for them to get in touch with the local people here in order to empower those kinds of agreements.”

The diplomats also explained how they seek to empower all members of the Hispanic community in their respective posts, including students.

“As a member of the foreign service of my country, it is important to empower stu-

are

dents after they finish university to join this career and open doors to provide different kinds of advice,” Treviño stated.

Newmann emphasized how students can learn new perspectives on international diplomacy through participating in events like these.

“It is important to look at what diplomacy looks like outside of [just] North America or Europe,” Newmann said. “Diplomacy means something different in the context of Latin America, and I think this event provides students with the ability to see those differences, and how that plays out in international relations.”

Cara Chellew leads workshop, showcasing walking as a research m ethod Culture Shock 2025: QPIRG hosts workshop exploring Milton-Parc’s hostile urbanism

Asher Kui News Editor

On Oct. 23, the Quebec Public Interest Research Group (QPIRG) McGill hosted the “Walking as method: Exploring hostile design in Milton-Parc” workshop as part of its annual Culture Shock event series. This exploration was led by Cara Chellew, PhD candidate in McGill’s School of Urban Planning, as well as Jonathan Lebire, co-founder of coaching organization Agence Dragonfly.

The event kickstarted at QPIRG’s office on av. du Parc, with a group of around 15 people making their way to the street’s intersection with rue Prince-Arthur Ouest. Chellew pointed out bright white light bulbs placed above benches at the intersection.

“Across the street, there’s another light, and you’ll see […] it’s actually blinking,” she observed. “For the longest time, I thought it was malfunctioning. [....] [But] it’s blinking very steadily. It’s been happening for a couple months now. [....] These interventions are meant to really target certain behaviours like trying to sit too long or sleep in public.”

Chellew continued to explain why these acts of hostile urbanism—architectural attempts to restrict certain social groups from enjoying public spaces—are meant to be kept subtle and unnoticeable.

“Often when [hostile urbanism is] really noticeable, […] there’s outrage, rightfully

so, and then sometimes, things get removed,” she said. “[Hostile urbanism] is meant to target these kinds of behaviours, but also not be very noticeable to everyday people.”

The group then ventured inside Les Galéries du Parc, where Lebire highlighted the neighbourhood’s lack of third places.

“You want to cry, you want to yell, […] something bad happened in your life, you don’t want to be seen crying. You’re going to transit to your house as soon as you can. But normally there should be what you call ‘third spaces,’ […] to kind of temper having a bad day at the job,” Lebire said. “There should be a way to use this architecture to make sure people have places to take a minute.”

Chellew then added that spaces where people cluster and socialize are crucial to a neighbourhood’s quality of living. She then talked about the intersection of av. du Parc and rue Milton, where an abandoned lot has been heavily restricted to keep Milton-Parc’s unhoused population out, effectively depriving them of third places.

“We’re purposely not going down [av. du Parc] because I want to give our friends a little bit of privacy,” she said. “There’s this lot that folks used to hang out [at]. [....] I call it ‘ground zero’ because it’s really the most heavily fortified spot in the neighbourhood. It just shows every little space here […] is restricted from people accessing [it].”

Chellew and Lebire continued the tour, pointing out benches that were designed to

be uncomfortable, with unnecessary armrests meant to keep sleepers away. Such benches could be found at intersections of rue Sherbrooke and rue Jeanne-Mance, and rue Sherbrooke and rue St.-Urbain.

The tour ended at Jardins du Monde et des Premières Nations at the corner of rue St.-Urbain and rue Milton, as Chellew encouraged McGill students to look out for signs of hostile urban planning.

This perforated ‘roof,’ located in the Jardin du Monde et des Premières Nations on rue St.-Urbain, is an example of hostile urban planning as it fails to provide shelter from adverse weather. (Asher Kui / The Tribune)

through various anti-oppressive perspectives.

“There are certain things that you can kind of look out for. When you’re checking out a space, are there places to sit? Does the space feel comfortable? Does it feel uncomfortable for some reason? Why is it uncomfortable? Is it too bright or too loud?” she emphasized.

In an interview with The Tribune, Joseph Liang, the Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU) Popular Education Events Coordinator, explained that this year’s Culture Shock aims to examine the McGill and Montreal community’s relations to the land

“For example [.…] with the Migrant Justice Panel [Culture Shock event], we look at land in terms of […] border regimes that are imposed on land,” they said. “I think [this land theme] is particularly relevant in the context that we’re living in. The settlercolonial occupation that we see happening in Palestine, that is fundamentally an issue of land, an issue of occupation of land. Here in Quebec, the PL 97 was a law that granted a lot of [Indigenous] land in northern Quebec to forestry companies. [....] I think land is sort of at the center of a lot of struggles that we are seeing right now.”

In Montreal, there

66 diplomatic missions from six continents, which help manage their respective countries’ consular affairs and foreign policy in Quebec. (Mia Helfrich / The Tribune)

Editor-in-Chief

Yusur Al-Sharqi editor@thetribune.ca

Creative Director Mia Helfrich creativedirector@thetribune.ca

Managing Editors

Mairin Burke mburke@thetribune.ca

Malika Logossou mlogossou@thetribune.ca Nell Pollak npollak@thetribune.ca

News Editors Asher Kui Helene Saleska Kaitlyn Schramm news@thetribune.ca

Opinion Editors Moyo Alabi Lulu Calame Ellen Lurie opinion@thetribune.ca

Science & Technology Editors

Leanne Cherry Sarah McDonald scitech@thetribune.ca

Student Life Editors

Gregor McCall Tamiyana Roemer studentlife@thetribune.ca

Features Editor Jenna Durante features@thetribune.ca

Arts & Entertainment Editors

Annabella Lawlor Bianca Sugunasiri arts@thetribune.ca

Sports Editors Ethan Kahn Clara Smyrski sports@thetribune.ca

Design Editors Zoe Lee Eliot Loose design@thetribune.ca

Photo Editors Armen Erzingatzian Anna Seger photo@thetribune.ca

Multimedia Editors Jade Herz Ella Sebok multimedia@thetribune.ca

Web Developers Rupneet Shahriar Johanna Gaba Kpayedo webdev@thetribune.ca

Copy Editor Ella Bachrach copy@thetribune.ca

Social Media Editor Mariam Lakoande socialmedia@thetribune.ca

Business Manager Celine Li business@thetribune.ca

McGill must get on the right track and prioritize accessibility—not anti-unionism

The Tribune Editorial Board

This October, employees of the Société de transport de Montréal (STM) filed strike notices that will disrupt bus and metro services throughout November. The Syndicat du transport de Montréal-CSN, which represents maintenance workers, has pledged to strike from Oct. 31 to Nov. 28. The Syndicat des chauffeurs, opérateurs, et employés des services connexes (SCFP 1983)—representing drivers and operators—also plans to strike, instead on Nov. 1, 15, and 16. Their decisions to strike follow over 100 failed negotiation efforts between the unions and the STM, in which the employees sought a 25 per cent wage increase and compensation for the hours they spend on tasks adjacent to their primary responsibilities, such as moving from station to station. This strike, critical for livable pay and fair working conditions for STM employees, will bear an impact on individuals across Montreal, including McGill students, faculty, and staff. As such, it is crucial that McGill, and other public institutions whose communities rely on public transit, prioritize supporting the strike by

offering reasonable accommodations for those impacted—not demonizing the strike as an inconvenience.

This will mark the third and fourth strikes by STM unions this year, following a two-week strike in September and an earlier strike in June. Yet, the prospects of achieving improved pay structures seem low; the STM has communicated a plan to cut over 300 jobs to offset its severe budget deficit, a fiscal antithesis to the wage increases its unions are demanding.

The STM serves over 1.7 million riders daily, many of whom take the metro out of necessity. Low-income Montrealers who cannot afford a car or alternative transit options will be particularly at risk if the metro shuts down, alongside commuters, senior citizens, and workers with precarious employment circumstances or irregular working hours. Furthermore, given that the strike measures extend to the closure of metro stations themselves, unhoused populations who rely on stations as a respite during the colder months will be forced into life-threatening conditions.

The McGill community too relies on the services the STM offers: Approximately 50 per cent of students and faculty and 70 per cent of staff use public transit or shuttle

bus options to access campus. When strikes disrupt service, students face long waits or are forced to opt for more costly, less sustainable alternatives. Yet when the STM unions went on strike just a month ago, the McGill administration’s only response was a brief memo directing students to consult the STM website and anticipate longer commute times, encouraging faculty to “be flexible” with students who may be impacted—without providing any tangible guidance or institutional support.

Nowhere in the memo did McGill set standardized expectations for professors and students navigating the strike. Administrators did not mandate classes go online or be recorded, resulting in a confusing mix of responses and varying degrees of flexibility. As a result, the burden of reliable support for the McGill community amidst STM closures fell on Students’ Society of McGill University services such as DriveSafe, while the McGill administration absolved itself of all responsibility to ensure campus accessibility.

Furthermore, the communication memo lacked any information regarding why the strike was taking place, effectively encouraging the McGill student body to redirect

Francois Legault’s climate policy is an unforced error

Max Funge-Ripley Contributor

Anxious about his plummeting approval rating, Quebec

Premier François Legault is shrinking away from one of his strongest positions: Fighting climate change. Earlier this month, Legault’s government announced it will end funding for the Climate Action Barometer (CAB), an annual survey that allows Quebecers to voice their opinions about their municipal, provincial, and federal governments’ environmental policies.

Curtailing this communication channel removes agency from a populace that has been clamouring for climate action. Meanwhile, Legault has hinted at more potential rollbacks— such as cutting the gasoline tax—at a time when climate action policies need to be front and centre.

Annual average surface temperatures are rapidly rising, and the frequency of extreme weather events is increasing. Tropical storm Debby was a brutal reminder of this for Quebecers. In 2024, the freak inland tropical storm killed an elderly man and became the costliest weather event in the province’s history.

By ending the democratic outlet that the CAB provided, Legault

alienates his constituents. Most CAB respondents support climate action; in response, he chooses to throw the survey out. This is not just a poor policy choice—Legault is silencing a mechanism that allows citizens to hold their government accountable. However, it does not have to be this way. Working with Quebecers to implement climate action is a ripe opportunity for Legault to regain some of the public faith he has lost, and it is imperative in the context of rampant global warming.

One of the shining stars of the Legault government has been its energy in fighting climate change. Thanks to his government’s investments, Quebecers around the province—from pilots-in-training in Gatineau to CEGEP teachers in Montreal—have tested commuting on electric bicycles through Equiterre’s Velovolt Program.

Last year, the Fonds d’action québécois pour le développement durable (FAQDD) provided $1.5 million CAD to support thousands of farmers in a collaborative project called Agriclimat, which helps farmers adapt to climate change and modify their farming techniques to lower carbon emissions.

This progress has sparked international acclaim, notably for Quebec’s hydroelectric power system

their frustration towards strikers. McGill has an extensive history of suppressing labour movements on campus, most recently during the 2024 strikes hosted by its Faculty of Law, during which administrators dragged out negotiations and insulted students who supported the striking faculty members. McGill must abandon its provocation of antiunion sentiment and blame-shifting among community members, and instead prioritize accessibility during all strikes, STM, faculty union, or otherwise.

McGill must standardize a university-wide response to STM closures, complete with genuine, effective accommodations that do not shift responsibility to the discretion of faculty. Without a cohesive, integrated response, community members are left disadvantaged and resentful of critical union activity, while the union’s efforts themselves are vilified. Students too must hold in high regard the rights of striking workers and avoid viewing metro closures as an inconvenience rather than a rightful protest tactic. STM employees have a right to strike; McGill has an obligation to support union activity and accommodate its affected students, faculty, and staff.

and research on circular economies of reuse.

If battling climate change has been such a bright spot for Legault, then why is he retreating from it?

The answer is affordability. He wants to recoup his losses in favourability with Quebec residents who are frustrated by his spending mistakes, like the $1.1 billion CAD spent on the well-over-budget SAAQclic project, and the $500 million CAD spent on the never-built Northvolt factory. In response, Legault is attempting to make a big deal of cutting the CAB, which costs one fivethousandth the cost of that nonexistent Northvolt factory. This is a mistake— for Legault and for the environment whose preservation he is choosing to neglect.

Counter to Legault’s rhetoric about affordability, cuts in environmental programs, such as the CAB, do not rest on sound economic logic.

Taking public transportation costs half as much as driving, and biking costs only one-seventh the cost of driving. Quebecers’ electricity bills are the cheapest in the nation— and it is not close. Environmentallyfriendly options are often cheaper for individuals than high-emission ones, so building up eco-friendly options would make life more affordable for

everyday people.

The strong support for climate action shown in the CAB study results should—and still could—be great news for François Legault. His government has a track record of delivering on community-focused environmental projects, so he should capitalize on this opportunity to further Quebecers’ climate priorities.

Quebec has worked hard to integrate clean energy and multimodal transportation, making many everyday necessities more affordable for residents while fighting for our planet.

Legault must not turn his back on his own progress. Defunding the CAB is detrimental to his party, his constituents, and the democratic process in which they participate, not to mention the environment as a whole, which is deteriorating and in need of swift action. Legault should play to his strengths and continue to set the pace for clean energy, sustainability, and public engagement in climate action.

Shatner University Centre, 3480 McTavish, Suites 404, 405, 406

Simona Culotta, Defne Feyzioglu, Alexandra Hawes Silva, Celine Li, Lialah Mavani, Nour Kouri, Laura Pantaleon

TPS BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Norah Adams, Zain Ahmed, Eren Atac, Basil Atari, Rachel Blackstone, Amelia H. Clark, Samuel Hamilton, Merce Kellner, Antoine Larocque, Alexandra Lasser, Lialah Mavani, José Moro, Jenna Payette, Alex Hawes Silva, Jamie Xie, Michelle Yankovsky, Ivanna (Ivy) Zhang Sahel Delafoulhouse, Lilly Guilbeault, Emiko Kamiya, SeoHyun Lee , Alexa Roemer

Loriane Chagnon, Guillaume Delgado, Dylan Hing, Joshua Karmiol, Anna Roberts, Sabiha Tursun, Jeremy Zelken, Sophia Angela Zhang

Sophie Schuyler, Kate Sianos

Canada must criminalize coerced sterilization and confront its propagation of colonial violence

it reached House debate.

Ellen Lurie Opinion Editor

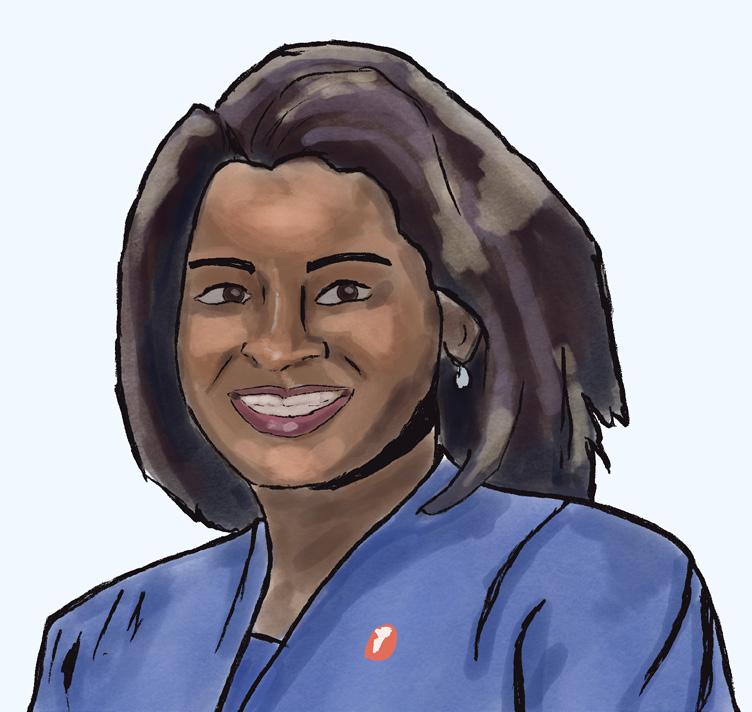

In 2005, Montreal practitioners performed a nonconsensual hysterectomy on Quebec Senator Amina Gerba, resulting in irreversible infertility. Gerba would not learn she had undergone this procedure—a clear violation of her medical rights and autonomy—until over a decade later, when, during an unrelated procedure, her gynecologist discovered she lacked a uterus. This phenomenon, known as coerced or forced sterilization, constitutes an international human rights violation and has been perpetrated against women—particularly of marginalized backgrounds—throughout Canada since the 1800s.

Despite centuries of evidence of nonconsensual hysterectomies, Canada has failed to criminalize this violating, dangerous practice. The persistence of forced sterilization testifies to how systemic anti-Blackness and colonial violence continue to shape Canadian healthcare systems, propagating the denial of Black and Indigenous women’s reproductive autonomy.

Senator Gerba shared her story when testifying in support of Bill S-228, an act to amend the Criminal Code that would criminalize coerced sterilization in Canada. An equivalent bill—Bill S-250—was introduced to and passed by the Senate in 2024. However, the proroguing of Parliament in advance of the 2025 Federal Election forced the termination of the bill before

Bill S-228 brings forced sterilization to the forefront of the legislative agenda, opening a window for overdue systemic change: Affording //legal// reproductive rights to women across Canada. In her testimony, Senator Gerba noted the intersectional nature of prejudices against Black and Indigenous women in the Canadian healthcare system, particularly in regard to gynecological interventions. In healthcare settings, medical students and practitioners alike frequently dismiss the pain of Black women patients due to the harmful and racist misconception that Black women have a higher pain tolerance. Such misinformation amounts to an undeniable truth: North American healthcare institutions are failing Black women.

Indigenous women have also been the historic and current targets of this procedure. In the 1970s, Canadian practitioners facilitated approximately 1,200 cases of coerced sterilization of Indigenous women as part of a broader eugenic, colonial effort to eliminate Indigenous persons. By systematically sterilizing Indigenous women without their consent, these practitioners—acting on behalf of the colonial state—sought not only to control individual bodies but to exterminate future generations of Indigenous peoples. This practice amounts to one of the five acts encompassed within legal definitions of genocide: The deliberate imposition of measures intended to prevent births within a group.

The UN Committee Against Torture issued

a statement in 2018 calling on Canada to end this abhorrent practice. Yet Bill S-228 remains under debate, and organizations like Amnesty International Canada continue to observe extensive evidence that the practice persists today.

In Quebec, 35 Atikamekw women have brought forward a class action lawsuit against the Centre intégré de santé et de services sociaux de Lanaudière (CISSS) for forced sterilization, citing at least 22 cases of the procedure between 1980 and 2019. Some of these women were misinformed, told sterilization was reversible. Others were falsely told that the health of their future children could be at risk should they fail to undergo the procedure. Still more were told the procedure was unavoidable in the maintenance of their long-term health.

An estimated 20 other women are pending approval to join the class action lawsuit; the youngest survivor was merely 17 years old at the time of her nonconsensual gynecological intervention. Clearly, Canada has subjected the reproductive rights of women—disproportionately Black and Indigenous women—to systemic disregard through its ongoing failure to implement policy prohibiting this medical practice.

In a report published by the Canadian Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights in 2022, representatives offered clear steps that the federal government must take to achieve the end of this abhorrent and violent practice. Foremost among these

recommendations were three key obligations: To criminalize forced and coerced sterilization; to implement measures heightening standards of informed consent and cultural competency in medical training; to collect data on sterilization to inform future policy and reconciliation efforts.

As Bill S-228 now awaits approval by the House of Commons, lawmakers, healthcare institutions, and the general public must call for the swift passage of this bill and for effective, comprehensive implementation. Evidence of forced sterilization is extensive and undeniable; its consequences for future generations of Black and Indigenous women are grave. Canada’s government must wait no longer to enshrine humane reproductive healthcare standards in the legislature.

Nobody is running for mayor! The death of municipal democracy in Quebec

Noah Bornstein

Contributor

On Nov. 2, Quebec will hold municipal elections—though in 87 cities throughout the province, the results of these elections are already decided. In the 2025 Quebec municipal election cycle, over 4,500 municipal candidates ran unopposed. In a process known as acclamation, candidates who are running unopposed bypass the election cycle and are automatically awarded the title. One of these constituencies is Terrebonne, a city of more than 120,000 residents. If Canada wants to maintain its democratic capacity at all three levels of government, then federal leaders need to treat municipal government with equal importance as they do provincial and federal governments

If nobody is running against incumbents, maybe constituents are simply happy with their current municipal leaders. That is what Terrebonne mayor Mathieu Traversy believes, and in his case, it might even be true. Traversy is a well-liked mayor and has a diversity of political viewpoints in his government. Nonetheless, he still ought to have an opponent for the sake of democracy.

It is abnormal for a city the size of Terrebonne to have zero competition in a mayoral race. In 2021, three candidates ran for mayor, and four candidates ran in 2017. The lack of competition for Mayor Traversy is a sign of political apathy and a weakening of local democracy. In a representative democracy, the primary way for citizens to influence policy is through elections. Without

elections, representative democracy fails to give its citizens a voice. Without a civic voice, democracy does not exist. In Terrebonne, there is no election, and consequently, no democracy.

While uncontested elections are concerning in cities like Terrebonne, they become even more troubling in small towns where municipal government roles are often thankless jobs. Faced with mounting tasks, these mayors often get lambasted on social media for minor problems that they have little power to fix. Yet, election by acclamation is most common in these districts. Of smaller municipalities in Quebec, almost a quarter of districts with less than 2,000 people elected an all-incumbent council this cycle. Normand Marin, former mayor of Pointe-Lebel in the Côte-Nord region, describes rural mayoralty as an impossible task because mayors of small towns tend to be overworked and criticized heavily on social media. The meagre salary makes the job even less desirable.

With immense censure and low salaries, it is no mystery why there are so few candidates for municipal politics. In the ChaudièresAppalaches region, four municipalities— Sainte-Cyrille-de-Lessard, Saint-Benjamin, Lac-Frontière, and Saint-Phillibert—currently have no mayoral candidates. Yet a robust democracy, especially at the municipal level where every vote counts, is reliant upon competition. The question, then, is how to make small-town leadership sustainable and appealing to would-be political candidates.

One potential solution for some of these smaller municipalities could be to merge with neighbouring towns. A municipality

such as Saint-Phillibert, which is closer to larger towns, could easily be added to the municipality of either Saint-Prosper or SaintGeorges. Declining local autonomy would be a necessary trade-off, as Saint-Georges has almost 33,000 people and a budget to match. Many of the administrative duties of a mayor could be absorbed by a larger, better-resourced municipal administration.

However, municipal mergers are not viable for every community. If Lac-Frontière merged with its neighbouring municipality, Sainte-Lucie-de-Beauregard, the new territory would span over 130 square kilometres with a combined population of just 450 constituents. Merging such remote, sparsely populated areas would only intensify logistical challenges, as servicing a large, spread-out region is far more difficult than managing a compact community.

Combining two municipalities of such a small size would only exacerbate the problems that sparsely populated municipalities already face.

Although merging municipalities represents a compelling potential solution to the crisis of Quebec’s uncompetitive municipal elections, the deeper issue is that local governments are chronically underfunded and understaffed. Government programs to mobilize capable university graduates into voting in municipal elections could offer a means to improve the province’s democratic capacity.

The provincial government cannot force people to run for office, but it can make running for office more appealing. A first step would be to properly fund and staff rural communities by bringing municipal government to parity with the provincial and federal levels.

In the 2025 Quebec municipal election cycle, over 4,500 municipal candidates ran unopposed and were thus automatically elected by acclamation. (Anna Seger / The Tribune)

Amina Gerba was appointed as the Independent Senator for Quebec in 2021. (Mia Helfrich / The Tribune)

My Halloween sitcom recommendations A spooky sitcom season

Sarah McDonald Science & Technology Editor

Do you fundamentally refuse to be scared out of your skin for socalled ‘entertainment’ this Halloween season? Have you seen The Nightmare Before Christmas one too many times? Yes and yes again? That’s what I thought. But don’t worry; the Halloween season has more to offer than inspiration for your very own sleep-paralysis demon and overdone, overhyped, over-Halloweened content. It’s the end of October, and I am pleased to welcome you to the season of spiders, skeletons, and sitcoms.

Brooklyn Nine-Nine

These Halloween episodes are famous, and for good reason. With a ‘Halloween Heist’ in every season, the squad competes to be in possession of a selected object by midnight, with the winner being crowned ‘an amazing detective/genius.’ These episodes contain some of the most elaborately ridiculous heist plans of all time—from stuffing pigeons into air vents and filling the precinct with characters from The Handmaid’s Tale to hiring previously-arrested criminals as co-conspirators—and the most intense rivalries. Watch a Brooklyn NineNine Halloween Heist episode for Charles Boyle’s (Joe Lo Truglio) terrible and forever un-guessable costumes, outrageous thievery, and to watch friendships be temporarily put aside in the name of glory.

The Office Season 2, episode 5 of The Office brings the reality of a scary Halloween into the workplace. Michael faces the terrifying task of having to fire someone while everyone else prepares for a Halloween party. Michael Scott (Steve Carell) acts as the Halloween Scrooge, and the real scare comes from the decision he must make. This episode reminds us that navigating adulthood is actually the spookiest part of any season.

Friends

Friend s is a staple sitcom for a reason, and its Halloween episode is no exception. Rachel Green (Jennifer Aniston) may or may not start writing children’s cheques after she runs out of candy, Phoebe Buffay (Lisa Kudrow) may or may not end an engagement, and the costumes—well, I guarantee they’re worse than yours. I don’t want to spoil too much for those of you who are planning a Friends marathon this sitcom season, so all I’ll say is: Pink. Fluffy. Bunny. Oh, and potato. If you want to be able to treat Halloween as a more-or-less regular day, this is the show for you. It’s lighthearted and fun—the only spooky part is the notion of marrying someone you’ve known for two weeks— making it a great choice for those who are ready for Halloween to be over already.

Superstore

Superstore is a lesser-known sitcom, or so I’ve been led to believe. But wheth-

er you’ve heard of it or not, its Halloween episode is worth a watch. Everyone shows up in costume, except for the company’s resident rule-follower, Dina Fox (Lauren Ash). Dina gets, as you might expect, peerpressured into dressing up. But she changes into a particularly revealing cop costume. Cue the chaos. Suddenly, everyone’s workplace archnemesis is alluring? If you ever reminisce over middle-school friendship dynamics—or just revel in watching middleschool-esque situations play out—then I promise you will be entertained. Her outfit, combined with rumours that someone may

or may not have a crush on someone else, makes the perfect storm for those of you who love to revel in the knowledge that you left high school behind years ago.

If you enjoy any singular aspect of the horror movie experience, you and I are clearly two entirely separate types of people. But you’d best believe that if I’m watching anything on Halloween, it’ll be a sitcom. I’ll laugh and sigh and be unspeakably grateful that Monica Geller (Courteney Cox) won’t ever buy me a Halloween costume.

Breaking ground at new creative collective’s defiant art-expo and rave

Concrete Breaks melds raving and fine art to form a multi-media concoction

Norah Adams Staff Writer

Iwas whisked into Concrete Breaks’ Communal Art-Expo and Rave on Oct. 23 by heavy bass thrumming under my feet and a crush of people bottlenecking behind me. Once through the doors, bright projections of cityscapes flashed to my right while a diverse array of prints and poetry lined the walls to my left. To the far end of the st. Laurent bar Barbossa, the density of event-goers increased until they formed a dancing mass, all crowded in front of one of the rave’s string of DJs.

Concrete Breaks is an offshoot of Nina Rossing, Matt Pindera, and Luke Pindera’s initial creative endeavour Pacific Breaks, “a grassroots electronic music collective” in Vancouver, which similarly hosted a rave. According to their mission statement, Pacific Breaks aimed to “reinvigorate Vancouver’s rave scene with innovative, open-air events and cutting-edge sounds.”

Concrete Breaks wields much loftier goals, evident from its name, which strays from a specific place and instead describes a geographically universal breaking from stasis. In an interview with The Tribune, co-organizer Nina Rossing described the globality of this event, noting artists from Denmark to Toronto. The cosmopolitan nature of the expo aligns with one of its cardinal themes: Connection.

Another facet of the art-expo rave’s broader scope lies in its name, the event being an amalgam of many art forms, breaking beyond just

sound. Concrete Breaks sent out a call for ‘All Medium/All Voices,’ the only directive being that pieces tackle the themes of dystopia, resistance and connection. This expansive breadth of forms came together at Barbossa to produce a mode of art that was completely novel.

The DJ’s beat shook the floor of the bar, causing the videos on the walls to fizzle at the edges while red rave lights cast prints on the wall in new shades. Each piece of art did not merely exist alone in the space, but instead all multiplied to form one new piece of which we were all a part.

Rossing reflected on what she and her team hoped to achieve through the event’s vast array of media.

“I think it’s just creating humanity. [...] The beauty of being human and the beauty of art and of hope, and the power that it holds,” she said.

The night’s goal of humanity was achieved tenfold, with tables sprawled with pens and sticky notes for attendees to place their art alongside the selected artists, a gallery space loud not from music but from conversation, and a dancefloor bouncing beneath jigging bodies.

Concrete Breaks undertakes a return to humanity, especially imperative in our current zeitgeist. As society moves towards extremist radicalization, forging simple connections feels unreachable—people become friends with artificial intelligence or strangers on subreddits.

Rossing emphasized the importance of resisting such a world of alienation.

“We need to connect more, and with that, we become super powerful, and we can turn bad

things into good things,” Rossing said.

Fellow organizer Luke Pindera similarly commented on the importance of the Concrete Breaks’ ideology in this moment. He told The Tribune in an interview that they “want to represent something positive amidst this […] world of chaos.”

Rossing, both Pinderas, the artists, and the attendees came together last Thursday to do just that: Create positivity and good. Everyone gathered, interacted, danced, and left feeling fuller

than when they entered.

The defiant art exposition, alight with inspiration and connection, presents a fresh perspective on the importance of coming together and pushing towards resistance. As proclaimed by Pindera, Concrete Breaks goes beyond just a collective; he described it to The Tribune in terms of a way of life. In this fissured world, perhaps we should take up their mantle: Look down and see how we may break the concrete upon which we tread.

‘The One With The Halloween Party’ is rated 8.4/10 on IMDB. (Zoe Lee / The Tribune)

In 2014, Lady Gaga performed Swine—a song about being raped by a music producer at 19—while an artist onstage shoved two fingers down her throat and vomited rainbow paint across Gaga’s body.

The performance was disturbing. It was also the most precise depiction of the feelings of shame, disgust, and paralysis of sexual violence I have ever seen. She did not merely describe her trauma; she made you feel a fraction of it.

One could reasonably ask what such a projection accomplishes. Disgust does not undo rape, and catharsis does not constitute restorative justice. Some see art that engages with violence as a luxury of those who can afford to aestheticize pain rather than endure it. Yet art’s power lies not in repair but in revelation: It exposes what violence conceals, insists that suffering be seen, and transforms recognition itself into a form of resistance.

In that way, the effects of art are not solely therapeutic or ornamental; they are epistemic. They alter our perception of reality, collapsing the emotional distance between experience and witness that makes apathy possible. Art has the unique ability to transmit the pain of the few into the conscience of the many. It serves as a medium for revelation, transmission, and survival.

Lewis, associate professor in McGill’s Philosophy department, traced the intellectual roots of this repression to nineteenth-century formalism—a European art theory that defined a work’s value by its structure rather than its emotional or social content.

“From my perspective, it’s really hard to see how you could actually imagine art merely to be decorative,” he says. “That really is a product of a particular moment in time in European, North American theorizing about art [....] But it stands in stark contrast to a much longer tradition of viewing art, in some sense, instrumentally, socially and politically.”

Art as revelation

Psychology has long known what politics refuses to learn: Intellectualizing our emotions doesn’t resolve them; it represses them. Therapists call it a defence mechanism—the mind’s way of avoiding what the body already knows. What occurs in the individual psyche also operates at the collective level. Entire nations learn to rationalize horror, to translate it into data and debate. But if emotional repression keeps individuals stuck in cycles of trauma, mor-

CAN ART

WRITTEN BY YUSUR AL-SHARQI, DESIGNED

BY ELIOT LOOSE, ON THE FAILURE AND NECESSITY REVELATION, TRANSMISSION,

Originally aesthetic, formalism rapidly increased amidst the logic of capitalist modernity, which privileges abstraction, exchange value, and efficiency over affective meaning. As art became increasingly commodified, emotion was recast as excess: Something to be managed rather than engaged. What began as a style of interpretation hardened into an ideology that treats feeling as a threat to reason. And when societies learn to distrust emotion, they become easier to govern through abstraction. Politically regressive and reactionary governments have long known this, and that is why they continue to wage a war on empathy—and by extension, on art.

“One of Hitler’s very first proclamations upon being made chancellor was to ban what was called at the time, ‘Negro art,’ [...] You know, in 1969 in the aftermath of the Paris student riots in France, the French banned a jazz and new rock music festival, fearing that would reignite the kind of protest movement,” Lewis said. “Going back in the western philosophical tradition [...] Plato literally bans certain musical modes because he believes they incite turbulent emotions that could yield in violent and active behaviour.”

Yet the capacity of art to move people is what makes it politically indispensable. By collapsing the distance between viewer and subject, art does what reason cannot.

“One thing that has to happen in order to convince folks to not just cognitively believe in anti-racism [...] but to get them to actually modify their own behaviours [...] requires somehow

ing, that Jean Michel Basquiat is very good at doing, that Nikki Giovanni is very good at doing.”

Palestinian artist Khaled Hussein is a prime example of how art anchors social change in care for the individual rather than allegiance to an abstract ideology. Hussein’s exhibition features various sculptures of legs, unassuming at first glance—mere limbs suspended in space, painted in muted tones—until one looks closely and reads the title: i miss you so much. The sculptures represent parts of bodies that no longer exist. Gaza has the largest number of child amputees anywhere in the world—a fact too easily diluted to numbers, until Hussein’s art renders it human again.

“It is true that amputees are everywhere, but a large portion of these victims are confined to their homes, reliving their physical and psychological pain, away from the eyes of others,” Hussein said in an interview with ArtZone Palestine. “I wanted people to recognize that something unseen can still wound us.”

His work takes mass tragedy and scales it down to an individual wound, pulling the viewer’s focus away from debates about the definition of genocide and ‘who came first’ and instead toward the innocent people at the heart of it all. Sadly, the violence he confronted in his art did not spare him: Israeli occupation forces bombed his house and Gallery 28 in Rafah, displacing him and reducing his art to rubble.

A representative of Students for Palestine’s Honour and Resistance (SPHR) at McGill, who wished to remain anonymous, reiterated Hussein’s sentiment about focusing on those directly affected by tragedy. For SPHR, discomfort is not a weakness of art, but its ethical function—it reminds us that no amount of physical distance from the genocide absolves us, and our institutions, of complicity.

“When images of the occupation and genocide are used, we need to remember

SAVE US?

NECESSITY OF ART FOR TRANSMISSION, AND SURVIVAL

AL-SHARQI, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF LOOSE, DESIGN EDITOR

ly funding, and it should absolutely make us uncomfortable.”

A similar idea plays out in Ibtisam Azem’s The Book of Disappearance, in which every Palestinian vanishes overnight. The premise may appear speculative, but Azem’s realism lies in the details; after all, the book imagines a reality that some already wish for, and that history has made possible in increments.

The novel’s Israeli narrator—a “friend of the Palestinians”— slowly inherits what isn’t his: His friend’s apartment, his coffee, even his words. Erasure here is not a single event but an accumu lation of small actions—the choice to call it ‘Tel Aviv’ as opposed to Jaffa, or to sign a lease for a home whose ‘owners left in 1948.’

The novel thus collapses the moral dis tance between complicity and atrocity, reminding readers that the scale of destruction we see today is sustained by millions of such minor, plausible gestures.

Art as transmission

The moment art leaves the page, the screen, or the gallery, it begins to circulate. As it weaves itself into conversations, gatherings, and protests, it transforms private emotion into public action.

In an interview with The Tribune, Montreal-based photographer William Wilson emphasized the importance of art in shaping public opinion and propelling activism.

“The level of grotesque violence that you see [...] does inform the political opinions of people. The more severe the images [...] and the more pressing the issue feels, perhaps the more likely [you] are to mobilize the streets for it,” Wil son said. “Probably the single most important mobilizing thing [is] imagery.”

Wilson’s work has exposed countless instanc es of police brutality at protests across the city. At the Rad pride demonstration this year, the Service de Police de la Ville de Montreal tear-gassed protesters; nearby, a family attending a salsa event was caught in the cloud. Wilson captured a photograph of the scene, showing a father clutching his infant, the baby’s tiny hand pressed against her eye, a five-year-old beside them frozen in fear. The photo spread rapidly across social media and quickly became a topic of conversation throughout the city.

deflections as “obscene,” but this kind of conversation in itself reveals the photograph’s power. Images don’t merely depict injustice but participate in its contestation. The circulation of that photo forced audiences to confront competing narratives about culpability, protection, and power. In doing so, it altered the long-held moral coordinates of public discourse: Who is seen as innocent, who is seen as dangerous, and who is meant to keep us safe.

Similarly, the representative from SPHR described how their imagery, particularly through social media, has enabled them to reach thousands of students across the city, resulting in record-breaking student support for the Palestinian cause.

“We live in

confuse it with argument. Art does not reason—it reorients. And reorientation is where action begins.

Art as Survival

Still, hesitation to speak of art amid suffering is understandable. It can feel almost perverse to speak of paintings and poetry while people endure material and bodily catastrophe—those in the midst of rape, occupation, or famine are not asking for performance art to make people empathize with them. And it is true that art, even when it mobilizes and exposes, can still fail to create the change we hope for. Yet, when all else fails, consider instead its most elemental power:

Some commenters accused the family of negligence, claiming they should not have been near a protest, or that “children shouldn’t be out past nine.” William dismissed these

al world and images help us communicate our message more efficiently, whether that be an image of previous student protests which show the will and power of the student movement, or images of Palestine which remind people who we are fighting for when demanding divestment.”

The evidence is palpable: On Oct. 7, 2025, SPHR helped mobilize thousands of students and community members for a strike and rally across Montreal, demanding university divestment from industries complicit in the war in Gaza.

Taken together, these examples make it hard to believe that theory alone could have moved so many people. To call art futile or self-indulgent is to

Discomfort is part of art’s purpose, especially in times of crisis. If art like Lady Gaga’s Swine performance makes us recoil, that reaction should remind us how fortunate we are to encounter pain only through art, not through our own bodies. It is easy to call a performance “too graphic” when we are safe enough to experiment with its horrors only through representation. The least we can do to honour those who create art in times of suffering is to recognize their pain: Look, feel, and resist the privilege of detachment.

One might think of the children of the Terezín ghetto, awaiting deportation to Auschwitz. Their art was discovered hidden behind the walls of the barracks after the war. Among them was a poem by Hanus Hachenburg, which reads:

“I am a grown-up person now, I have known fear.

[...]

But anyway, I still believe I only sleep today, That I’ll wake up, a child again, and start to laugh and play.”

Hanus was killed in Auschwitz in 1944 at the age of fourteen.

Art may not have saved him, but if nothing else, it gave him a form of survival beyond the body. Maybe that’s why the children of Palestine paint flowers and the children of the Terezin ghetto wrote poems about butterflies—because art offered them what reality no longer could: The hope of freedom, and perhaps the feeling of it.

The hidden merit of McGill’s Visual Arts Collection A closer look at the art pieces that students pass every day

Dylan Hing Contributor

One thing that everyone can agree on about McGill is that the campus is absolutely stunning. With the beautiful Mount Royal as a backdrop to the varying architectural styles on campus, one only has to stop and look to find beauty here. Often ignored, the many smaller pieces that make up McGill’s Visual Arts Collection (VAC) also possess their own beauty; they bring the university’s distinctive cultures to the forefront.

Scattered around campus, the collection features paintings, photographs, cultural items, and several sculptures that

punctuate the university’s green spaces. Since it began collecting art in the 1830s, McGill’s VAC has grown to over 3,500 pieces. With a library of works that large, nothing is forgotten.

I was particularly impressed by the collection’s emphasis on Indigenous art, including the minimalist nature pieces by the late Benjamin Chee Chee displayed on McConnell Engineering’s first floor. His work Afternoon Flight , depicting geese in motion, uses simple strokes and minimal colour to create a striking image that seems both ancient and contemporary.

As demonstrated by Chee Chee’s piece, the collection’s contemporary pieces highlight diverse perspectives that reach

beyond European-style portraits and settings.

For example, on Macdonald Harrington’s first floor, I stumbled across a photograph by Yann Arthus-Bertrand; it’s an overhead shot of a Dogon village near the town of Bandiagara in Mali. It presents the town from the perspective of an outsider, inviting the viewer to learn more about the Dogon people and their way of life from an angle they might not have otherwise considered.

Outside, the collection continues in the James Sculpture Garden, where community members pass through and study day in and day out. These abstract sculptures definitely fit in with their surroundings—although they sit within view of the 19th-century-style administration building, they also sit within the shadow of the very 20th-century-built McConnell Engineering Building.

These juxtapositions make the campus feel cohesive despite its many artistic and architectural differences. Like a museum, every piece of art belongs exactly where it stands, and like a museum, the VAC takes its position as a provider of public art very seriously.

Uniquely, while the VAC has works of art in storage just like any museum in the world, its Visible Storage Gallery on McLennan Library’s fourth floor offers a unique glimpse of artwork that would not normally be on display. The collection displayed here is a microcosm of the types of paintings chosen to hang around campus.

It acts as a snapshot of the wider collection—complete with European-style portraits, abstract sculptures, landscapes and photographs, and a major compilation of Indigenous-created artwork.

One of the pieces, What is She Looking at? What Does She See? by Freda Guttman Bain, is particularly intriguing. In my exploration of campus art, it was the first photograph I’d seen of a human subject, and a woman at that. Although the photo is in black and white, it reflects a sort of modernity compared to many of the paintings and ceremonial objects in the room with her. With the subject sitting across from the camera, the viewer is explicitly asked to wonder what she’s facing. Perhaps a more equal future?

Taking more notice of the art all around campus can be a learning experience in and of itself, as the priorities of the collection have changed over its two centuries of building. Through various specialized exhibits, including the Japanese prints on the fourth floor of Bronfman, the VAC today critically highlights non-Western approaches to art and artistry. Although art is but one aspect of creating a safe community for all, the diversity of the VAC is an important reflection of the students for whom it is presented.

While you rush to classes or find yourself hunched over a textbook, take a moment to look around and see how cultures around the world have displayed their passions, fears, hopes, and stories. You never know what you might find.

Le Train is a dream-filled Quebecois coming-of-age film

Festival du Nouveau Cinema’s closing film harkens back to 1960s Quebec

Siena Torres Contributor

This October, Festival du Nouveau Cinéma wrapped up its 54th edition, featuring a robust program of 200 films over 12 days. The Montreal-based film festival prides itself on showcasing diverse international features and short films, while spotlighting a strong selection of Canadian films. This edition’s closing film, Le Train, is a mesmerizing debut from renowned Quebecois playwright and actress, Marie Brassard.

Le Train follows Agathe, a young girl in 1960s Quebec, who dreams of a fantastical world where she is not plagued by severe asthma. As she grows into adolescence, she meets a man who shares her same longing for something more than their reality. Rising stars Thalie Rhainds and Electra Codina Morelli, who play Agathe at various ages, deliver captivating performances that hint at promising careers ahead. The exquisite Larissa Corriveau, who plays Thérèse, Agathe’s eccentric mother, shines in her portrayal of a woman balancing professional life, single motherhood, and creative pursuits.

In an interview with The Tribune, Brassard reflected on the experience of writing and directing her first feature film, noting how it differs from theatre. She described theatre as ephemeral: An experience that creates unique experiences each time. It lives only in our memories because it takes place in the ‘real’ world with ‘real’ people, as opposed to cin-

ema.

“Cinema is different. At one point, you have to stop [adding on] for it to exist as an object, and from that moment on, it’s gonna be that. You have to let it go,” Brassard said. “And at the same time, what’s beautiful is that you can look at it again and again, and eventually have a different experience as well, but the thing is that it will persist in time.”

Inspired by her own childhood experiences with asthma in the Quebec suburbs and her coming-of-age in 1970s Montreal, Brassard sought to recreate the feeling of hope she felt at that time, contrary to today’s cynicism and increased isolation.

“I wanted to make a film that would state that there was a time [in Quebec] where people were dreaming. People were dreaming of a better world, a more equal world,” Brassard said.

As someone who admires the aesthetics of the 1970s, I found the visuals of Agathe’s teenage years a feast for the eyes. Brassard mentioned that she remembers the aftermath of Montreal’s Expo 67, a world’s fair in which there was a liberating spirit in the air, both politically and creatively. Le Train recreates these artistic communities and countercultures that she found in the city, where intellectual and creative thoughts were freely exchanged.

Brassard grew up listening to the sound of trains running through her town, dreaming of the places they would go. In Le Train, these dreams recur and contrast the rest of the film in their black-and-white stylization, as Agathe

tries to figure out both their meaning and the other world that intrigues her. Brassard used these childhood dreams as the starting point of her script.

“I imagined that it was a lumberjack there [by the train], who was cutting trees and protecting our world, and that he was standing at the frontier between us and the world that we don’t know,” Brassard said.

The themes of identity, dreams, and a blend of fantasy run through much of Brassard’s work.

“There’s something fundamental that is

part of you that you cannot escape from. And I think that for me, it is a very thin layer between dream and reality, or between the imagined and reality,” Brassard said. “And somehow, it intersects with [the] science worlds. When we think of quantum realities, where scientists reflect on the possibility of parallel worlds that we cannot perceive.”

As Le Train rolled its final frames, it left audiences with a resonant message that speaks to both nostalgia and hope, reminding viewers of a time, and perhaps a place, where dreaming of a better world still felt possible.

The 3,500-piece collection is spread across over ninety buildings and public spaces. (Sophie Schuyler / The Tribune)

The community of Montreal creatives the film depicts was heavily inspired by Brassard’s own experiences as a teenager. (Kate Sianos /The Tribune)

McGill Athletics’ varsity program restructuring: Student-athletes’ perspectives

Varsity- and club-team athletes alike report hope for more transparency from McGill Athletics in the coming months

Clara Smyrski & Zain Ahmed Sports Editor Staff Writer

For over a year, rumours have circulated that McGill Athletics is evaluating its varsity teams with the intention of making cuts to the varsity program. This year, that rumour was confirmed. Fourthyear Women’s Rugby player and Varsity Council member Annette Yu shared in an interview with The Tribune that McGill Athletics has communicated with select Varsity Representatives that a ‘restructuring’ of the varsity program is underway, having started this in September. McGill Athletics will also consider 12 to 15 of McGill’s club teams that are petitioning to gain varsity status, rethinking which teams at the university deserve to wear the varsity ‘M.’

According to Yu, McGill Athletics shared that factors such as a team’s performance, recruitment, funding, alumni support, facilities, eligibility, medical services, and transportation will determine whether they gain, maintain, or lose varsity status. The review is set to be completed on Dec. 1.

This week, The Tribune sat down with athletes from various varsity and club teams to learn about how McGill Athletics’ restructuring may affect them.

Varsity Women’s Rugby

Martlets Rugby players Kate Murphy, U2 Science, Olivia Ford, U3 Arts, Yu, U3 Arts, and Captain Raurie Moffat, U4 Education, shared that in a 2024 meeting with McGill Athletics, the team was given an ultimatum: Win games in the 2025 season, or get cut. Moffat explained Martlets Rugby seemed “set up to fail,” when asked to prove their program growth without the resources to do so.

Because the team plays in the Réseau du sport étudiant du Québec (RSEQ) and U SPORTS leagues, they are ineligible to compete without varsity status. Furthermore, with greater team fees and administrative duties under club status, the players expect that if Women’s Rugby gets cut from the varsity roster, a formal team will cease to exist at McGill.

Every player spoke to the team’s positive impact. Yu emphasized the sense of community it gave her in her first year, and Ford said that if McGill did not have a team, she would have been deterred from attending McGill.

Moffat explained how the team’s potential cancellation is detrimental to future women in sport at McGill.