In a world that rarely slows down, where concrete stretches further than the eye can see and the city hums day and night, Subtle emerges as a quiet space. We are a magazine dedicated to exploring well-being and spirituality not apart from urban life, but deeply embedded within it. Here, we believe that healing doesn’t require escaping the city — it can begin at the crosswalk, in the morning light hitting your kitchen wall, or in the moment you finally take a breath between meetings.

Urban life is complex, asometimes chaotic, and often overwhelming. But within that chaos, there is rhythm — and within rhythm, the chance to reconnect with ourselves. Subtle exists to trace those connections: between the inner and the outer world, between body and mind, between ritual and routine. We’re interested in how people cultivate presence in fast-paced environments, how they find meaning in small daily acts, and how softness can survive and even thrive in hard places.

Through essays, interviews, practices, and visual storytelling, Subtle invites you to reflect, question, and feel. Our stories are rooted in real life, but always reaching inward. We welcome both ancient wisdom and modern messiness, spiritual traditions and intuitive gestures, silence and sound. There’s no one path here, only possibilities — subtle ones, perhaps, but powerful all the same.

This is an invitation to pause. To pay attention. To remember that even in the city — maybe especially in the city — the sacred is always within reach.

By Luiza Frade

Podcasts for the Spiritual Searcher

Pause | Pages

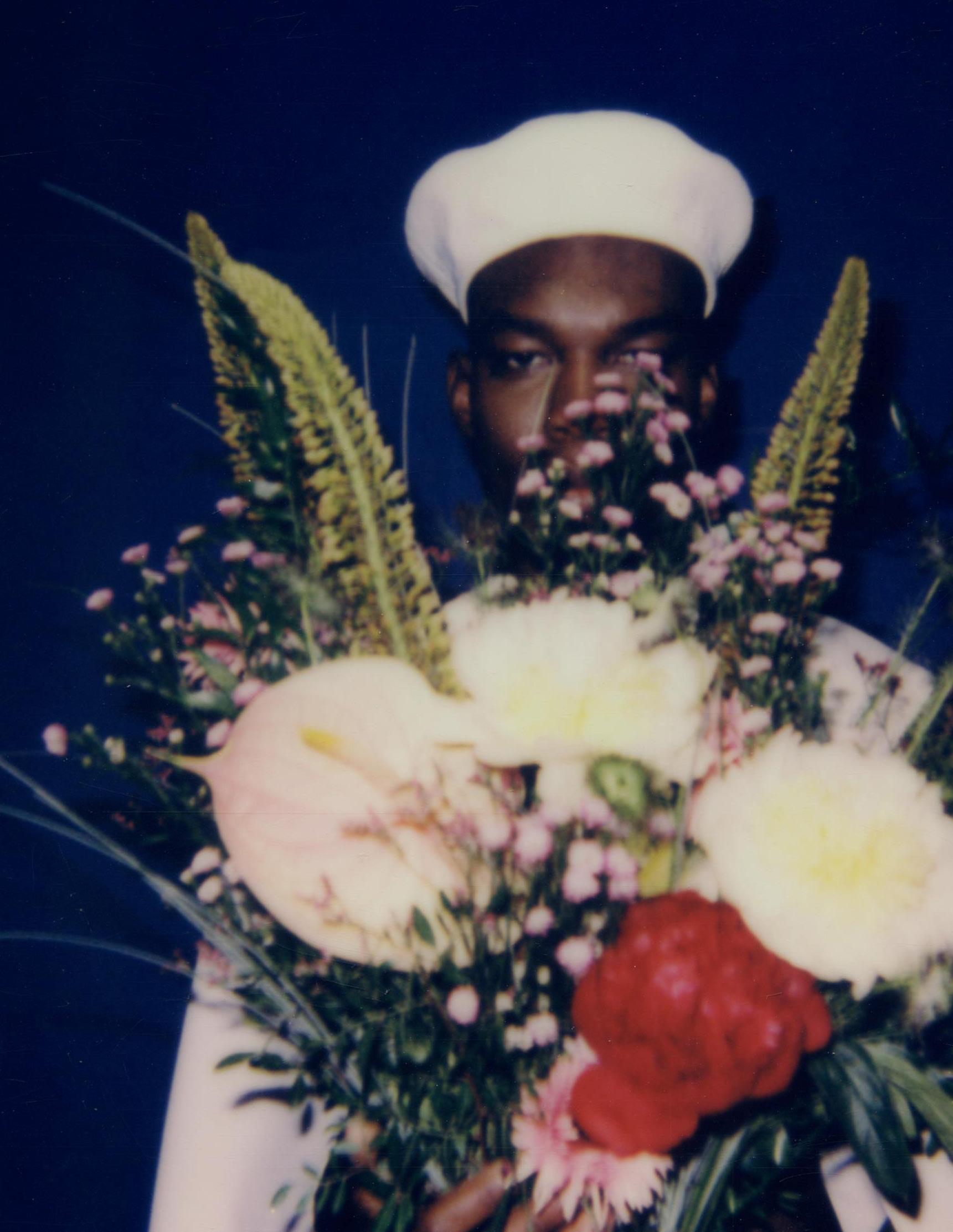

Photography

Pause | Pages Poetry

The Power of the Presence

Why is the loneliness epidemic so hard to cure?

Are We In the Middle of a Spiritual Awakening?

Even as organized religion loses adherents, people continue to seek higher meaning in their lives.

written by Emma Dibdin illustration by Mayara Sampaio

Organized religion may be on the decline, with more Americans than ever identifying as either atheist, agnostic or religiously unaffiliated. But spirituality’s grip remains tenacious, with the search for meaning merely taking different paths. A growing number of Americans identity as “spiritual but not religious,” a trend that tracks with the explosion of interest in practices like meditation and astrology that transcend traditional religion. If you are spiritually curious, podcasts make it possible to curate your own diverse radio diet, finding voices to which you relate while also dabbling in viewpoints that are unfamiliar or even antithetical to your own.

With “On Being,” Krista Tippett explores what it means to be human and live well, through conversations with scientists, artists, politicians and more. The focus is not on any particular belief system or denomination, but on the abstract forces — beauty, nature, loss — that can shape an inner life. When Tippett was awarded the National Humanities Medal in 2014 for her work on the show, the Obama White House praised her in a statement for “embracing complexity and inviting people of all faiths, no faith, and every background to join the conversation.” That remains the podcast’s strong suit today.

The RobCast Rob Bell, a pastor turned media personality, has built

The Potter’s Touch

Bishop T.D. Jakes has become one of the most famous pastors in the country since founding the Potter’s House, a 30,000-member nondenominational megachurch in Dallas. What “The Potter’s Touch” lacks in production values, it makes up for in sheer energy and verve thanks to Jakes’s rich, sonorous baritone and knack for persuasive oratory. Most episodes are wholesale recordings of Jakes’s sermons, which often use religion as a jumping-off point for discussions about personal upheaval and even mental illness, as in a memorable installment from last year titled “When Anxiety Attacks.” Though a tough sell for anyone not predisposed to the megachurch style, the show provides a unique window into the worshiping habits of vast swaths of America.

Oh No, Ross and Carrie!

Ross Blocher and Carrie Poppy are former evangelical Christians who channel their mutual fascination with belief into this weekly show, which turns skepticism into a wry, revealing art form. “Oh No, Ross and Carrie!” allows the duo to conduct undercover investigations of religious groups, cults and fringe science, and then discuss their findings back in the studio. Some of their missions are wrapped up in a single episode, while others take longer; their gripping investigation of Scientology is spread over a well-earned 10 chapters. At the end of each investigation, Blocher and Poppy rate their subject in a series of categories, including creepiness, danger and pseudoscience.

If you’re looking for a simple, audio-based alternative to the overwhelming number of meditation and mindfulness apps on the market, a weekly dose of Zen is available from Tara Brach, a psychologist and Buddhist meditation teacher. Through a mix of guided meditations and motivational speeches, Brach explores the lofty concept of spiritual awakening alongside more concrete everyday problems like anxiety, conflict and insomnia. And most helpfully, she addresses the common stumbling blocks that make it hard to stick with a meditation practice.

Joel Osteen, the prominent televangelist and megachurch leader, has attracted both a devoted following and a healthy amount of controversy for his preaching of the “prosperity gospel,” the belief that there is a link between Christian faith and financial success. The podcast, with new episodes every few days, showcases upbeat sermons from Osteen and his wife, Victoria, also a pastor at Lakewood, that tend to focus as much on cognitive patterns as they do on scripture. In recent episodes, Osteen has emphasized the importance of gratitude and urged listeners to envision an abundant future in which they are wealthy and successful, even they are struggling right now. While the primary audience will be Christians seeking on-demand sermons, Osteen’s unique position within his community may make the show an informative listen even for atheists.

In our hyper-connected world, where distractions are endless and multitasking is the norm, the simple act of being fully present has become a rare and powerful gift. True presence—giving someone your undivided attention—has the power to deepen relationships, foster trust, and even transform ordinary moments into meaningful ones.

Research shows that when we are truly present, our brains synchronize with those we're engaging with—a phenomenon known as "neural coupling." This creates a sense of connection that texts, emails, and distracted conversations can never replicate. Presence isn't just about listening; it's about making others feel seen, heard, and valued. Studies in psychology reveal that feeling genuinely acknowledged activates the same reward pathways in the brain as financial incentives, demonstrating just how fundamental this need is to human wellbeing.

Yet, presence is under siege. Smartphones, endless notifications, and the pressure to always be "productive" fracture our attention. We may be physically in a room, but our minds are elsewhere—scrolling, planning, or worrying. The cost? Shallow relationships, missed opportunities for genuine connection, and a lingering sense of disconnection even when surrounded by people. A 2023 study found that the average person checks their phone 58 times a day, with heavy users experiencing significantly lower relationship satisfaction.

The good news? Presence is a skill we can cultivate. It starts with small choices: putting away devices during conversations, practicing active listening, and grounding ourselves in the moment through mindfulness techniques. The rewards are profound—stronger bonds, reduced stress, and a richer experience of life. Clinical trials have shown that just eight weeks of presencefocused meditation can physically thicken the brain's prefrontal cortex, enhancing our ability to focus and connect.

Perhaps most importantly, presence is contagious. When we model deep attention, we give others permission to do the same, creating ripples of authentic connection in our communities. Teachers who practice presence report classrooms buzzing with engagement, while managers who listen deeply foster more innovative teams. This multiplier effect suggests that our individual efforts to be present could collectively reshape our culture of distraction.

In a world that glorifies busyness, presence is an act of rebellion. It says, "This moment matters. You matter." And in that space, real connection flourishes. As we relearn this ancient art of being fully here, we may discover that presence isn't just a personal practice—it's the foundation for healing our fractured attention and rebuilding meaningful human connections in the digital age.

written by Mayara Sampaio

Like a flower, we grow

the sunny ones. not just

Why is the loneliness epidemic so hard to cure?

Maybe because we aren’t thinking about it in the right way.

When psychologist

Richard Weissbourd began investigating loneliness at Harvard in early 2020, he was building on alarming pre-pandemic data showing over half of Americans regularly experienced loneliness. His comprehensive survey of 950 individuals revealed startling findings: more than a third reported chronic loneliness, while another 37% experienced it intermittently. These numbers represented a significant

increase from previous decades and painted a troubling picture of American social life.

The COVID-19 pandemic acted as both a magnifying glass and an accelerant for this crisis. As lockdowns forced people into isolation, the fragility of modern social connections became painfully apparent.

Weissbourd noted how the pandemic "exposed and turbocharged" existing vulnerabilities in our social fabric. Young adults emerged as particularly vulnerable, with many reporting that

of the respondents reported feeling chronic loneliness in the previous month

social distancing measures had severed their already tenuous connections to community and purpose.

What made these findings especially concerning was their persistence even after pandemic restrictions lifted. A 2023 Gallup poll found that 25% of adults still reported frequent loneliness, with rates nearly doubling among young people.

The American Psychiatric Association confirmed this trend, noting that a quarter of Americans felt lonelier postpandemic than before. These statistics suggested the crisis wasn't just about temporary isolation but reflected deeper, systemic issues in how we connect.

The health implications became impossible to ignore. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy's 2023 advisory drew direct parallels between loneliness and smoking, noting its association with cardiovascular disease, dementia, and premature mortality. Researchers found that chronic loneliness could increase dementia risk by 40% and shorten lifespan as much as obesity or smoking 15 cigarettes daily. The crisis had clearly evolved from a personal struggle to a full-blown public health emergency.

What makes modern loneliness particularly insidious is its paradoxical nature in an ostensibly hyper-connected world.

As Weissbourd's research revealed, many lonely individuals weren't physically isolated but rather trapped in unsatisfying relationships. Nearly half reported feeling they invested more effort into connections than they received in return, while 19% believed no one outside their family truly cared about them. This pointed to a crisis of quality, not just quantity, in human connections.

The pandemic's legacy continues to shape our social landscape. Studies show many emerged from lockdowns with atrophied social skills, struggling with basic interactions like maintaining eye contact or casual conversation. Simultaneously, the convenience of digital alternativesfrom food delivery to remote work - created new barriers to spontaneous human connection. These combined forces have left many Americans feeling profoundly disconnected in crowded virtual spaces.

To understand today's loneliness crisis, we must examine its historical evolution. Historian Fay Bound Alberti's research reveals that before the 19th century, loneliness as we understand it barely existed as a concept. While people certainly experienced solitude, it wasn't inherently associated with distress. In fact, in pre-industrial societies where privacy was scarce, solitude was often welcomed as a rare luxury.

The Industrial Revolution marked a turning point. As people migrated from rural villages to crowded cities, traditional community structures dissolved. Alberti's analysis of linguistic trends shows the word "loneliness" began appearing with unprecedented frequency in the 1820s, precisely as urbanization accelerated. This wasn't coincidental - people were grappling with a new form of alienation amidst crowded tenements and factory work.

The mid-20th century brought new dimensions to the problem. Sociologist David Riesman's landmark 1950 work "The Lonely Crowd" identified how postwar prosperity and

consumer culture were reshaping social bonds. Americans increasingly defined themselves through possessions and status rather than community ties, creating what Riesman called "other-directed" personalities constantly seeking external validation.

Simultaneously, psychologists began recognizing loneliness's severe mental health impacts. Frieda FrommReichmann's groundbreaking work distinguished everyday solitude from pathological loneliness capable of triggering psychotic episodes. Her research revealed how prolonged loneliness could create a self-reinforcing cycle of suspicion and withdrawal, making it increasingly difficult for sufferers to connect even when opportunities arose.

The late 20th century saw loneliness become medicalized

as researchers uncovered its physiological impacts. The work of John Cacioppo and Louise Hawkley demonstrated that loneliness wasn't just psychologically painful but physically harmful, triggering inflammatory responses and accelerating cellular aging. Their evolutionary theory framed loneliness as a biological warning system - like hunger or thirst - alerting us to unmet social needs.

Today's crisis represents the culmination of these historical trends. The decline of community institutions, from churches to unions, has left many without traditional support networks. At the same time, digital technology has transformed social interaction in ways we're still struggling to understand. What began as an industrial-era phenomenon has become a defining feature of postmodern life.

of young adults (18-34) report no close friends

Modern neuroscience has revolutionized our understanding of why loneliness feels so viscerally painful. Groundbreaking brain imaging studies reveal that social rejection activates the same neural pathways as physical injury. The anterior cingulate cortex, which processes physical pain, lights up equally when people experience social exclusion - explaining why loneliness can literally feel like a wound.

Psychologists Louise Hawkley and the late John Cacioppo spent decades mapping loneliness's physiological impacts. Their research shows chronic loneliness triggers a cascade of stress responses, including elevated cortisol levels and increased inflammation. These changes weren't merely correlational - in ingenious experiments using hypnosis, they demonstrated that inducing feelings of loneliness could directly raise blood pressure and inflammation markers.

The evolutionary explanation for this pain makes it even more fascinating. As social creatures, humans depended on group cohesion for survival. Loneliness likely evolved as an early warning system - like hunger signals the need for food, loneliness signals the need for connection. In our ancestral environment, social isolation meant literal danger, hence the body's dramatic stress response. However, this ancient alarm system malfunctions

in modern contexts. Where occasional loneliness once motivated people to reconnect with their tribe, today it often triggers maladaptive behaviors. Hawkley's research identified a cruel paradox: the more lonely people feel, the more they tend to withdraw and interpret social cues negatively, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of isolation.

Neuroplasticity plays a surprising role in this process. Chronic loneliness appears to rewire the brain's threat detection systems, making lonely individuals hyper-vigilant to potential social slights. This neural hypersensitivity explains why lonely people often misinterpret neutral expressions as hostile and why well-meaning advice to "just socialize more" frequently backfires.

The physiological consequences extend far beyond momentary discomfort. Long-term loneliness correlates with a 26% increased mortality risk, surpassing many traditional health risk factors. It accelerates cognitive decline and increases vulnerability to everything from heart disease to compromised immune function. These effects are so pronounced that some researchers argue loneliness should be treated as a medical condition.

Perhaps most tragically, loneliness impairs the very skills needed to escape it. Studies show lonely individuals often struggle with emotional regulation and social cognition, making it harder to form new connections. This creates what psychologists call a "loneliness trap" - the condition actively prevents its own resolution through neurological and behavioral changes.

The erosion of America's social infrastructure has created fertile ground for the loneliness epidemic. Political scientist Robert Putnam's seminal work "Bowling Alone" documented how participation in community organizations - from PTAs to bowling leagues – plummeted in the late 20th century. This decline has only accelerated, leaving many without the casual connections that once provided social sustenance.

Religious institutions, historically central to community life, have seen particularly dramatic declines. Gallup data shows weekly religious attendance has fallen from 70% in the 1950s to just 21% today. This represents more than just secularization – it's the loss of a ready-made community that provided everything from social support to rites of passage. As Weissbourd notes, these institutions offered "structure for dealing with grief and loss" that many now lack.

The workplace, another traditional site of social connection, has been transformed by remote work. While 22 million Americans now work from home, research suggests virtual interactions don't satisfy our need for connection. University of Kansas studies found younger workers are half as likely as older colleagues to form close friendships at work, reflecting how digital work environments inhibit organic relationship-building.

“Has someone taken more than just a few minutes to ask how you are doing in a way that made you feel they genuinely cared?”

Family structures have undergone equally dramatic changes. Single-person households have tripled since 1950, now comprising 29% of all homes. Marriage rates have declined sharply, while multigenerational living has become increasingly rare. These shifts mean many Americans can no longer rely on family as their primary social safety net. Even community spaces have diminished. Sociologist Eric Klinenberg documents how "third places" – cafes, parks, libraries – that once facilitated casual interaction have declined in both quantity and quality. Many remaining public spaces have become commercialized or securitized, discouraging spontaneous sociability. The result is what Klinenberg calls "social deserts" - neighborhoods physically crowded but socially barren.

The digital revolution has created paradoxical effects on these trends. While technology enables unprecedented long-distance connection, it often does so at the expense of local ties. Studies show heavy social media users frequently report feeling lonelier than moderate users, suggesting virtual connections don't fully satisfy our social needs. The convenience of digital life – from food delivery to streaming – has also reduced the necessity of face-to-face interaction. These institutional declines have created what researchers call a "network society" – one where people have more

contacts than ever but fewer meaningful relationships. The average American's social network has shrunk dramatically since the 1980s, with surveys showing nearly half of young adults report having no close friends. Without traditional community structures, many are left adrift in a sea of shallow connections.

Addressing the loneliness epidemic requires moving beyond simplistic solutions. While Surgeon General Murthy's advice to "call a friend" is well-intentioned, it fails to account for how profoundly our social landscape has changed. Effective solutions must address both individual behaviors and systemic failures in our community infrastructure.

Urban design offers promising avenues for intervention. The concept of "social infrastructure" - public spaces designed to foster interaction - has gained traction among policymakers. Examples include pedestrianfriendly streetscapes, community gardens, and mixed-use developments that encourage casual encounters. Research shows such design can significantly increase neighborhood social capital.

Workplaces need reimagining for the hybrid era. Rather than mandating full returns to office, forward-thinking companies are creating "anchor days" where teams gather for meaningful collaboration and social bonding. Some are incorporating

"connection hours" into schedules - dedicated time for non-transactional interaction that mimics the watercooler conversations of traditional offices.

Technology, often blamed for isolation, can also be part of the solution when used intentionally. "Slow social media" platforms emphasizing depth over virality are gaining popularity. Digital tools that facilitate realworld meetups, like neighborhood sharing apps, help translate online connections into offline relationships. The key is designing technology that serves human needs rather than exploiting attention.

Intergenerational programs represent another promising approach. Initiatives pairing seniors with young people for mutual support have shown remarkable success in reducing loneliness across age groups. These programs recognize that different generations often have complementary needs - elders craving purpose, youth seeking wisdom - that can be met through structured interaction.

Policy innovations are also emerging. Singapore's "kampung spirit" initiative funds neighborhood projects that build community cohesion. The UK's "social prescribing" program allows doctors to refer isolated patients to community activities. These

approaches recognize that solving loneliness requires systemic support, not just individual effort.

Ultimately, overcoming the loneliness epidemic will require cultural shifts as profound as those that created it. We must move beyond stigmatizing loneliness as personal failure and recognize it as a societal challenge. This means valuing care work as much as productivity, prioritizing time-rich living over convenience culture, and redefining success to include community belonging.

The path forward won't involve returning to some idealized past, but rather building new forms of connection suited to our digital age. As Klinenberg observes, every major social transformation initially increases loneliness before new modes of community emerge. The challenge - and opportunity - lies in consciously shaping what comes next.

written by Scharlet Cho

by Cottonbro Studio

A single bloom, so soft, so small, Pushes through the cracks of all The silent grief we try to hide, The ache that echoes deep inside.

Its petals hum a quiet song, Of things that hurt, but don’t stay long. Of time that moves, and breath that slows. Of how a broken spirit grows.

A flower doesn't ask for much, Just light, and air, a gentle touch. Still it rises, wild and true— A lesson hiding in the dew.

For growing isn’t loud or fast, It doesn't burn—it doesn’t blast. It whispers in the wind, it waits, It cracks old pain and rearranges fates.

The bloom will come—it always does— In quiet strength, in what just was.

As traditional religion declines, a new spirituality is emerging. One that finds meaning in recovery groups, nature, and human connection. While some mourn fading institutions, others see a rebirth of personal faith, redefining what it means to seek the sacred today.

When I asked readers who identified as spiritual but not religious to reach out to me, I was astounded by how much variety there was in the faith experiences of individuals in this group. Some said they found spirituality both in the beauty of the physical world and in communing with other people.

“I found the 12-step program to be sort of a spirituality that worked for me,” a woman named Maggie who lives in the Northeast told me. (I’m not using her last name because one of the tenets of her 12-step program is anonymity.) “It’s about making a connection with a higher power. It’s about trying to improve that connection with prayer and meditation,” she said.

Maggie lost her taste for organized religion, she said, after being disappointed by the way her church handled a situation in which a minister had an affair with an employee. She finds the 12-step program to be free of that kind of hypocrisy and appreciates the “bone-scraping honesty” of her fellow group members. People talk about “what’s really going on in their lives,” she said. “It’s refreshing and often relatable, and it feeds me.”

As I read and listened to the wide range of spiritual stories that readers shared with me over the past few weeks, I thought about the way that nones — the catchall term that describes atheists, agnostics and nothing in particulars — can imply blankness and almost a kind of nihilism.w

But as I learn more about the idea and the history of being spiritual but not religious, and the growth of this self-definition over the past few decades, alongside the documented move away from traditional church attendance, I wondered if I hadn’t given enough weight to new expressions of faith. Rather than seeing this moment as reflecting the slow demise of organized religion in America, one that leaves some people bereft of community and meaning, it’s worth asking if we’re in the middle of the birth of a messy new era of spirituality.

First, I want to be honest that I’m not going to be able to give a definitive answer through the data here. The polling around questions of spirituality is pretty noisy, because the terms “spiritual” and “religious” are “so amorphous and they overlap so greatly,” said Robert Fuller, a professor of religious studies at Bradley University and the author of “Spiritual but Not Religious: Understanding Unchurched America,” when we spoke last week.

It’s also important to note that spiritual beliefs have been part of American faith since the earliest days of colonization. “Colonial Americans were especially eclectic when it came to their beliefs about the supernatural,” Fuller writes. “While less than one in five belonged to a church, most subscribed to a potpourri of unchurched religious beliefs including astrology, numerology, magic and witchcraft.” (And the Indigenous people of North America had their own belief systems that varied from nation to nation.)

When you get granular about what people believe today, specific beliefs don’t always track neatly with the labels that people use for themselves. As I wrote last year in a series about nones, many people who identify as having no religion in particular still go to church and still believe in a higher power.

Pew Research tried to rectify the overall lack of good data on spirituality with a big report in December. Pew acknowledges that this is a tough topic to pin down because definitions of spirituality are all over the map: Though church attendance has definitely declined and formal religion is important to many fewer Americans than it used to be, “the evidence that ‘religion’ is being replaced by ‘spirituality’ is much weaker, partly because of the difficulty of defining and separating those concepts.”

That said, Pew’s survey found that “22 percent of U.S. adults fall into the category of spiritual but not religious.” Pew found that some of the things that most S.B.N.R.s believe are that “people have a soul or spirit in addition to their physical body” and “there is something spiritual beyond the natural world, even

if we cannot see it.” They are also likely to believe that animals and elements of nature like rivers and trees can have “spirits” or “spiritual energies.”

In his book, which was published in 2001, Fuller describes S.B.N.R.s as “seekers” who often “view their lives as spiritual journeys, hoping to make new discoveries and gain new insights on an almost daily basis. Religion isn’t a fixed thing for them.” They tend to value intellectual freedom and “often find established religious institutions stifling.”

Even at that time, Fuller wrote that “unchurched spirituality” was “gradually reshaping the personal faith of many who belong to mainstream religious organizations.” And I would argue that this kind of spiritual influence has increased.

While confidence in and adherence to organized religion have dropped since the aughts, according to a 2023 Associated Press/NORC poll, 63 percent of American adults believe in karma, 50 percent believe “that the spirits of those who died can interact with the living,” 42 percent believe “that spiritual energy can be rooted in physical objects,” 34 percent believe in astrology and reincarnation, and 33 percent believe in yoga “as a spiritual practice.”

There are those whose fears about the retreat of organized religion have reached the point that they insist the world would be a better place if more people were forced to be like them. You see the fruits of this panic everywhere: in Louisiana’s new law that requires posting the Ten Commandments in all classrooms, and in the Oklahoma state superintendent’s edict that the Bible must be taught in all public schools.

But there’s another, more nebulous concern that I have heard — and expressed myself — that organized religion is an obvious way to find meaning outside oneself and to form community, and that those things may be harder for some people to achieve without the ready-made structure that existing churches, temples and mosques offer.

Reporting this piece has changed my thinking somewhat, because I’ve been focused on the decline: the decaying church buildings with their fraying exteriors and cold, emptying pews. What we may be seeing instead are the first shoots of regrowth, of something else that’s too new and diffuse to really track or understand properly.

Many spiritual communities form online, which means that cataloging them is even more difficult. “There’s such a large number by now of groups that form over affiliations with S.B.N.R. or nones that it’s hard to know where to begin,” said Linda Ceriello, an assistant professor of religious studies at Kennesaw State University. “These sorts of groups had plenty of momentum prior to the pandemic, but that circumstance cemented their presence and utility for so many.” She made it clear to me that we won’t know the full

shape of the change until this period is in the rearview.

Still, I was most moved hearing from Brent Wright, an Indiana-based hospital chaplain, who also believes that we’re in some kind of transitional period. When we spoke, he said, “Those of us who are living right at the cusp of this shift are the ones bearing the burden of the cultural assumptions that came before us that we’re breaking out of, but then bearing the uncertainty of what does this mean?”

He talked about the profound, transcendent spiritual connection he experiences through his work with patients. “I can look in their eyes and they look back and whatever our conversation is, whatever the content on the surface of the words, there’s a spiritual connection,” he said. “There’s a togetherness and aliveness that is profoundly rooted in the fact that we are both simply human beings and we’re here right now and I care.” I can’t think of a deeper, more meaningful experience than that.