I

MATUSCHKA

LOVE MYSELF MORE THAN I LOVE MYSELF

“What makes a heroine? Someone who enters difficult battles and emerges victorious. Someone who challenges society's thinking and creates a new and higher standard than ever before. Someone who inspires, provides hope, encouragement and support to many people. Matuschka is a woman to admire for her beauty, to thank for her fierce bravery, and most especially, to honor for her heroism.”

–Leigh Silverman Broadway Director

Since the 1970s, Matuschka’s heroine seemed ideally created for women; one who is strong, unafraid, and unashamed. The desire to eradicate shame is at the heart of her work. Whether it be the startling photos of her naked body in a roadside lake, her one-breasted iconic images to raise awareness, or her own amusement with cross dressing, she is highly sexual in a revolutionary way; on her terms with one breast, one scar, a mustache, toupee, goatee or blond wig. Her photographs strike you, dare you. She asks of you something you may have never felt before: a new acceptance and love for the human body, with no beauty ideal attached to it.

Her work also illustrates a global generic theme: we are all unique and yet universally alike; but the central question is: “What is beauty and why do we strive to enhance our body—and our image— to fit conventional ideals or radical new trends in appearance?”

I Love Myself More Than I Love Myself is an anthology of Matuschka’s black and white photographs encompassing five decades of her love affair with the camera (behind and in front of one) from 1970 through 2021. The photographs in this book explore the phenomenon that many individuals share: the common desire of transforming their current life situations by altering—or attempting to

alter—their appearance.

Matuschka is without a doubt an artist for the times. Her unique style combined with a fundamental understanding of human nature is powered by Zappa’s mantra: I Love Myself More Than I Love Myself. One must love oneself before they can love others. Her ability to capture that undefinable but absolutely necessary element raises mere record to memorable experience. She is a survivor with a voracious capacity for telling a truth about the human spirit. Matuschka's self-directed photographs, self-portraits and collaborations with others eradicates self-consciousness while taking the wraps off several taboo topics: nudity, breast cancer and gender modifications. In this way we can view her photographs as having both a therapeutic and aesthetic effect on the viewer. For women it is empowering. For men it challenges conventional readings of desire in a vitalizing way.

By understanding Matuschka’s work, we acknowledge the power of women as creators of culture, not as eternal victims nor as idealized female images. We also examine the underlying causes of women's conditions in society to understand and to expand our creative potential. Matuschka's works represent a courageous act which often shocks at first glance. After further reflection we begin to see a beauty of strength and survival.

Either you capture the mystery of things or you reveal the mystery. Everything else is just information.

– RAGHU RAI

IT’S ME.

IN 1970 I WENT SKINNY DIPPING IN A LAKE IN MAHWAH, NEW JERSEY. AN ENTHUSIASTIC PHOTOGRAPHER JUMPED OUT OF THE BUSHES AND ASKED TO TAKE MY PHOTO. I RESPONDED, "UNDER ONE CONDITION: YOU SEND ME SOME PRINTS."

LITTLE DID I KNOW THAT DAY I WOULD BECOME BOTH A PHOTOGRAPHER AND MODEL. AND OF COURSE, A MUSE TO MYSELF.

PUBLISHER

PINKY TOE PRESS

BOOK DESIGN

Matuschka

COPYRIGHT

©2024 Matuschka & Co., All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

CONTACT

matuschka@verizon.net (646) 408 7818

www.matuschka.net www.matuschkathemodelofthefuture.com @matuschkafinearts

Printed in the United States of America

First Printing, 2020

ISBN 0-9000000-0-0

Sections of this book were featured in the following publications amongst many others:

The New York Times

LIFE Books

People Magazine

Aperture Books

American Photo

P/F Magazine

Glamour Magazine

Maclean’s Magazine

FOTO Magazine

Stern

Der Spiegel

World Press Foundation

Kamera Magazine

35mm Special Edition

Cosmopolitan

News Austria

TIME

Collector’s Magazine

US Magazine

Mademoiselle

The Body: Photographs of the Human Form, William Ewing

The Age of Silver: Encounters with Great Photographers; John Loenguard

The New York Times Magazine Photographs; Kathy Ryan (Editor)

MATUSCHKA FINE ARTS

In the late 1980s Matuschka, an established artist and former fashion model, chose photography as her main medium after taking pictures of herself as an experiment in abandoned buildings. The inspiration came from a suite of images published in the June 1971 Playboy Magazine, of the famous model – Veruschka – whose painted body made a profound impression on her.

Matuschka's first comprehensive photographic series entitled The Ruins was published in many fine art magazines internationally, including the cover of P/F (Professional Photography) while exhibits were mounted at the Center for Photography at Woodstock and the Photographic Museum of Helsinki until 1991. The Ruins, based on Matuschka posing alongside plaster casts of her body in abandoned buildings, is considered her first major work known to the public. The images of her figure cloned in plaster, along with herself, juxtaposed with picture frames, mirror and plastic, often created a tromp l’oeil impression. The result is more like a photograph of a painting, or photography capturing a performance in a dream.

At the age of 37, Matuschka was diagnosed with breast cancer and began making posters and taking pictures of herself in a variety of 'styles' to bring greater attention to what was then called "The Silent Epidemic". Matuschka is credited with helping launch the breast cancer movement with her iconic self-portraits which attracted global attention beginning in 1991.

Matuschka joined many breast cancer groups and her alliance with W.H.A.M.! proved to be the most significant. In May 1993, W.H.A.M.! sent Matuschka with a suitcase of political posters to the National Breast Cancer Coalition conference held in Washington D.C. to represent the group. Susan Ferrara, a writer from The New York Times, was covering the three-day event. On the last day of the convention, she spotted Matuschka wearing the Vote for Yourself poster on her body much like a sandwich board at a strike. Ms. Ferrara interviewed the artist for the article she would title: The Politics of Breast Cancer.

That August, The New York Times decided to run Ms. Ferrara's article as a feature in their Sunday Times Magazine and selected Matuschka's photo, Beauty out of Damage, showing her mastectomy and face in the picture—a decision that turned out to be controversial—sparked debate about the treatment, awareness and depiction of breast cancer throughout the world. This

historical publishing decision made headline news for showing a "topless" cover girl on a mainstream magazine, and was viewed by many as ending the silence, shame and concealment for millions of women regarding their bodies and how they are portrayed by the media. This series, entitled Beauty out of Damage, which Matuschka worked on from 1991-2000 is her most political and historical body of work to date.

Like others before her, she challenged stereotypes and did not conform. But unlike others, Matuschka took self-portraits, reminiscent of high fashion photographs, in vertical format, in color, “with enough room for the Magazines’ masthead to be displayed across the top of the image. I deliberately designed my breast cancer imagery to mimic magazine covers.” In total, 22 more book and magazine covers would follow in addition to thousands of reprints in periodicals, paper backs, hard covers, documentaries, magazines and newspapers.

Matuschka always works in series, typically photographing herself in a wide range of locations, different contexts and various guises. To create her photographs, Matuschka assumes numerous roles as she explores the shapes formulated by her body, the various aspects of her persona, the connection between beauty and damage, and the history of photography itself.

Whether working with others, alone, or with an assistant, Matuschka is the author, director, make-up artist, hairstylist, wardrobe stylist, and master printer of the pictures she creates. Covering decades of figurative, photographic, and abstract expressionism rich in iconic imagery, her conceptual photographs are self-portraits, sometimes chemically toned or skillfully manipulated in the darkroom. Her works are in the collections of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York; Cincinnati Art Museum, Ohio; and the Musee de I'Elyee Lausanne, Switzerland among many others.

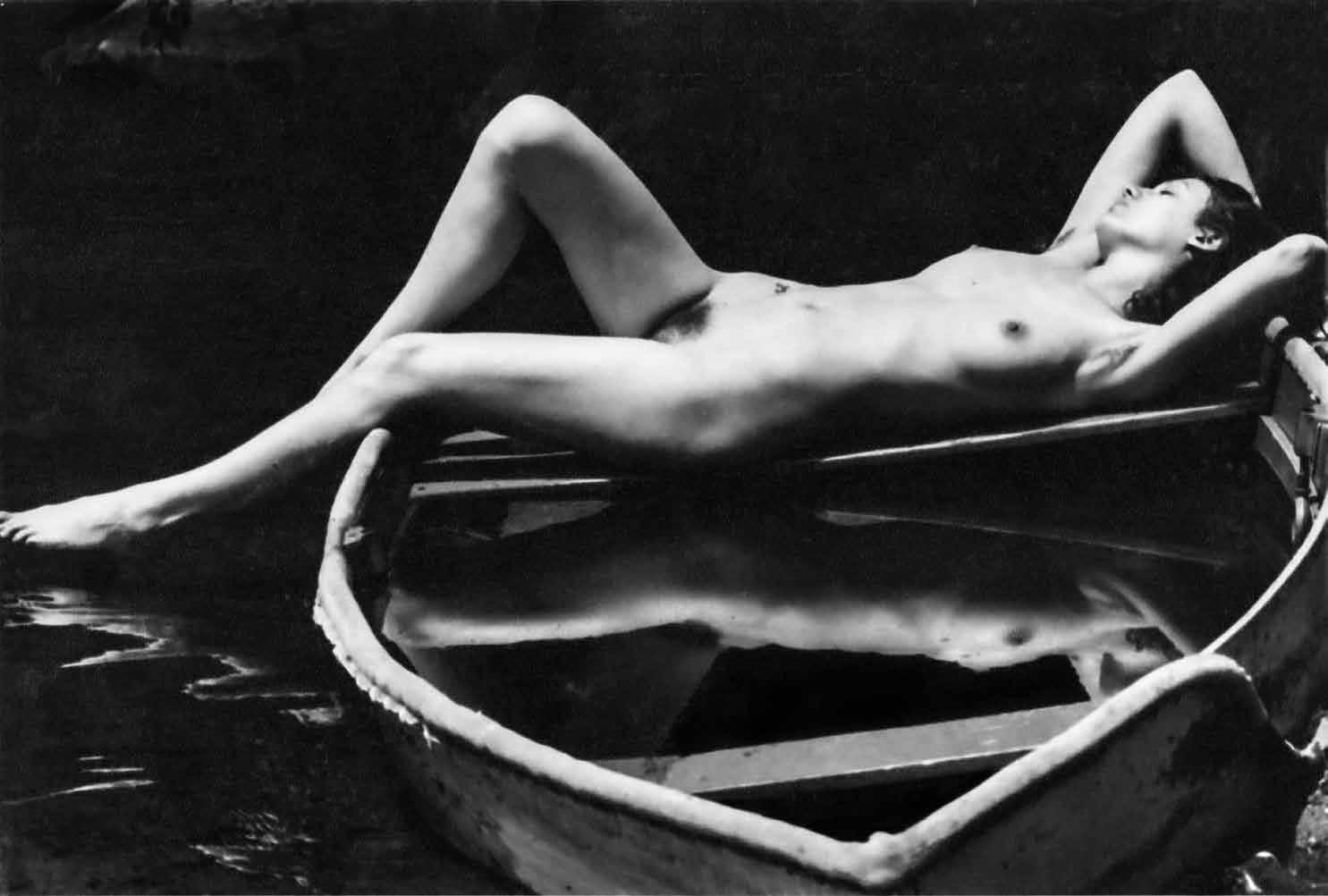

Photo previous page: Matuschka/McWhorter It's Me, Lake Buel MA 1972

Photo following page: Anton Perich, Charles James' Tulip Dress, New York City 1978

matuschka

I LOVE MYSELF MORE

Self-directed portraits from 1970 to 2021

THAN I LOVE MYSELF

FOREPLAY

The muse inspires; the artist creates. This ancient binary between creation and embodiment is exemplified in the Greek myth of Pygmalion and his Galatea: a sculptor and a marble woman of such beauty that the Gods deigned to vivify her so that her lovestruck creator might marry his custom-made bride. The artist makes; the muse is made. The photographer looks; the model is seen.

But when the muse sees her own reflection in the mirror and takes a picture—what then?

It is this traditional perception of the female model as a passive accessory in the artistic process that Matuschka’s work seeks to renegotiate. In her presentation of self as an active performer, Matuschka blurs the roles of photographer and model, reworking this dual dynamic between beholder and the beheld so that the audience no longer ‘stares at’ the model but are, instead, engrossed by the model’s own gaze.

It is this distinct combination of fine-a t precision and a fuckyou attitude, which comes together to form the specific aesthetic that is consistently contained in Matuschka’s pervasive self-portraiture. She has forged this aesthetic for nearly a half-century career while frequently being mistaken for someone else’s muse.

Whose?

Try any of the male photographers who continue to take credit for their collaborative works. “Photographers think that they have complete artistic ownership over photographs. I have a different viewpoint on this,” Matuschka laughs. At 67, the artist is wry, honest and reflective about her s oried career.

“I mean, I think Marilyn was the artist in her pictures. She had a tremendous love affair with the camera—she made that magic happen. If you couldn’t take a good photo of Marilyn Monroe, something was wrong with you!”

When we bring up Marilyn, I am thinking of that iconic first Playboy centerfold which featured the blonde Monroe sprawled, nude, against a lush red background; eyes lidded in a gaze that could seduce the lens itself.

Like Marilyn, Matuschka’s own love affair with the camera will begin in her birthday suit. But it will be the lens—and what lies behind it—that will fascinate the young artist from that first summer day in 1970 when she becomes a model and a photographer at the exact same moment.

"Matuschka's performance photography is a compelling story of transformation. All art is, to varying degrees, an act of revolution. It asks us to change, if only momentarily, the way we see. But political art has a specific purpose. It deliberately leads the way to a shift in social values and historical perspective. It ignores taboos. Matuschka's body has become a body politic, her art subversive, an act of revolution."

Nancy Baele

The Ottawa Citizen

"I needn't be cynical about Matuschka. She isn't an empty-headed fashion model capitalizing on her looks or the calamity of misfortune, but an honest-to-goodness artist and activist."

Karen Caviglia

Sojourner

RAW

By Jeremy Stigter with Peter Falk

Narcissism wasn’t born yesterday—the Greeks obviously knew a thing or two about it. In a similar vein, there is nothing particularly novel about the advent of the selfie. Though the term may be newly coined, the self-portrait as a photographic practice has been exercised from the very beginning of the history of photography by fledgling and experienced photographers alike. Maxi Matuschka has had a distinguished career as both a model and photographer. Her self-portraits have been her primary means of artistic expression. Matuschka has considerable presence. An imposing figure, she stood six feet tall before a calamitous accident compressed a vertebra, thereby “shrinking my spine,” she says. With a deep voice and a booming laugh, this voluble character presents a curious mix of strength and fragility—of masculine brutality and an almost girlish coquettishness. However, in 1993 the story behind a far more serious incident would be told by her self-portrait on the cover of The New York Times Sunday Magazine. It’s an image unique in the history of photography. It’s also the opposite of narcissism. She is clothed in a white sleeveless dress, and a white diaphanous fabric is wound around the top of her head, stretching along her left arm out of the picture frame. But one’s eye is quickly drawn to the shocking focal point. The right side of her torso is exposed, revealing the large scar that had replaced her right breast. The cover had a huge impact, for nothing like this—showing off the result of a mastectomy—had been done before in such an unforgiving way. No wonder that LIFE books selected it for 100 Photo-

graphs that Changed the World. It won numerous accolades and medals and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

Following a long period of breast cancer awareness activism, Matuschka received corrective surgeries and a full breast eventually took the place where once there was but a scar. She has emerged with a series of projects, including this book—I Love Myself More Than I Love Myself. After years of taking self-portraits she invited others to join her, which is how I found myself gently roped into doing a shoot of her during her latest visit to Paris. The shoot was divided into two parts, the first of which might be called a fashion shoot with Matuschka wearing a black dress. She had received this “thing”—as she disparagingly called it—in lieu of payment for having appeared in a Paris fashion show. It was more of a wrap than a dress, the shiny black silk resembling little more than a big black plastic bag when not worn properly. She hated it. Nevertheless, she decided to model the “thing” and did so with poise. She may not be as limber as she once was, but she most certainly has retained all the moves. If the latter may seem somewhat reminiscent of another age of modeling—one where the big gesture still counted for something—the pictures certainly reveal that she still knows how to turn it on. The second half of the shoot shows her wearing a fabulous concoction of her own creation—an embroidered bikini with feathers hanging on either side of her hips, a big Indian necklace, and, topping it off, a very bright platinum blond wig. It’s like something one might have seen in a sixties Hollywood B-movie as there’s

something distinctly Californian about the whole look. If it reveals parts of her body that might not reach the high standards of perfection Matuschka sets herself, it matters not. She looks quite the part and she can still be considered a catch.

What is most remarkable is the contrast between the two series of shoots. In the first she is fully dressed, with the exception of her magnificent legs covered in black stockings. The effect is a certain high-class chic. In the second she presents as “a white trash hippy” (her own words)—revealing all both physically and psychologically. Faced with these two opposing versions of Matuschka’s “photographic representation,” I at first felt rather puzzled, and wondered what her possible motivation may have been for presenting herself these ways. Could it be that she has chosen to show the two distinct parts that compose the new person she has become: the woman she once was merged with the woman she has become? Does that first chic part represent this new self—a “Manhattan self”? Does that second part represent her “original self”—the “white trash hippy” who made it all the way from rural New Jersey to the limelight in New York? Could it be, in having chosen two very different, even opposing, ways of presenting herself that she is telling us the story of her life? Or, was this two-act play where the process of posing served as an unintended self-revelation, where viewers are innocent onlookers of a drama taking place in her mind? Whatever her motivation may have been, the result appears to have pleased her as can be witnessed from the handwritten notes scribbled on top of the contact sheets. Upon the seventh frame in the first series she wrote, “the best picture ever to have been involved in”—surely high praise coming from a photographer as critical as she. The reason for this may very well be that together we managed to record the full force of her presence, whether dressed up or down, or looking chic or totally trashy. If I too am happy with the pictures it’s only because the force of her presence ultimately gives them their “zing.” I felt so compelled to capture her story that my goal was not to shoot the “one great picture.” Instead, the entire set of sequential pictures became increasingly fascinating as the shoot progressed. It was as if the mechanics of the shoot laid bare the process in slow motion, shot by shot, in revealing the subject. If these pictures are any good at all, it is primarily owing to

Matuschka’s overwhelming desire to actually become the picture. I may be projecting this alternative reality upon her, but it seemed that for a glorious moment she was once again the stunning model as well as the very person she refused to be anymore. In either guise, there is an intensity in each and every picture. In the first series she achieved this energy by playing fashion for all it’s worth by taking up the pose, and, as they say, really working it. In the second series she achieved another energy by simply standing half naked, staring down the camera. Then, almost like a caged animal intent on showing its magnificence, she slowly rose to her full height, hands on hips, giving herself entirely to the camera, letting it all show with a never-say-die, fuck-you attitude. Here is the merging of past and present lives, and perhaps more important, the woman as survivor. The sheer power of her projection appears to imbue the pictures with ambiguity. It isn’t clear whether we are seeing the “real” Matuschka or whether she is performing—but a formal distinction between the two projections matters little because

Matuschka simply is the performance. This is photographic representation of her own choice, her own reality. Sometimes her self-portraits appear outrageous, hyped-up, or even the self-indulgent products of an exhibitionist. However, they are equally full of pathos, with a measure of raw emotion expressing her gnawing sense of insecurity as to who and what she is—yet coupled with the sheer courage in overcoming these very fears. Thus, her play-acting is not masquerade. It is heartfelt and sincere. Her sense of vulnerability, normally hidden by a show of big attitude, is poignantly laid bare—as is her courage to overcome the vulnerabilities of insecurity and pain. Such is her own unique and magnificent form of masterly expression, and her work, including these pictures, should be judged only on these terms. In Matuschka’s entire body of work her physical being is her main means of expression.

Matuschka—the grand dame of the self-portrait—is still a muse to herself, and while her work may appear self-absorbed, her self-absorption has nothing to do with either narcissism or the reverse narcissism of self-loathing. She is and always has been, her own raw material. She looks at her raw material objectively and manipulates it unflinchingly, which now seems, in a way, uncannily predictive.

1 2 3 4

I Love Myself NAKED

I Love Myself HIGH END

I Love Myself RUINED

I Love Myself MINUS ONE

I

Love

Myself MANIPULATING

I Love Myself QUEER

I Love Myself LOVING OTHERS

I Love Myself MORE THAN I LOVE MYSELF

I Love Myself NAKED

The body is meant to be seen, not all covered up.

— MARILYN MONROE

We were skinny-dipping in a murky lake located behind an abandoned mansion in Mahwah, New Jersey in 1970, a sort of hippie haven when a group of passing bikers came upon us. One of them had a camera and asked if he could take photographs of us standing naked near the water. I said, 'under one condition, you give us some prints.'

In the 70s, photography was different. Hardly anyone had a camera; pictures had to be developed manually in a home-made darkroom, usually in their bathroom. In this case, the photographer would need to print the images himself, then mail them out. Though the anonymous photographer eagerly agreed to Matuschka’s demand, the likelihood that the young woman would ever receive those shots was a long shot.

Incredibly, she did. The photographer kept his promise: that weekend, Matuschka received an envelope containing a few photographic prints and a first glimpse of a possible future.

Crucially, Matuschka’s nude work and her early education in her articulation has already begun: she has, at this point, already been a frequent life-sketching model for classes around New Jersey. But it was that shoot at the lake which spurred her initial career as a model. When that photographer, his name now lost forever, showed the pictures around to his friends and fellow shutterbugs, Matuschka was suddenly busy posing for a variety of regional photographers in North Jersey.

“I really didn’t make much money as a nude model,” she smiles. “The value was for aesthetics, the making of something interesting, poetic or beautiful.”

Modeling means access to darkrooms, and early lessons in the alchemical process of photography. Seeing her body emerge on the photographic paper, she began to view it differently: as an object, as something to make art with.

For the young artist, nude photography is a way to make collaborative art with other people using the tools she already pos-

sesses, her body, personal vision, and artistic training. Modeling quickly becomes a means-to-an-end: education for nothing, photographs for free.

From these formative mentors she learned not only how to pose but how to print; how to develop pictures in bathrooms and basements, how to tone and spot prints.

But the true spark of art will come from elsewhere. One day—while the prints are drying—a photographer gives her a gift which will change the trajectory of her career forever. A January, 1971 Playboy Magazine featuring a photo spread shot by Franco Rubartelli of the German model, Veruschka, whose nude form is painted vividly into an optical illusion of abstracted animals and stones. She was “a blend between the beautiful and the bizarre, the perfect mix between reality and imagination,” Matuschka recalls. Painted like a snow leopard, a lizard or even a rock, Veruschka used her body as an art form. “She made me realize that being in front of a camera could be an enormously creative experience. Modeling could be a means to convey something personal; to make a statement or to even be a symbol.”

Matuschka’s inspiration to become both a model and a photographer will come more from the models she admires than from the photographers she would work with. In her childhood she had been drawn to the pin-up girls of the ‘50s, but it was the ‘70s own Veruschka, not Marilyn, who will introduce the young Matuschka to the true artistic possibility of her body.

While the men who mentored her helped to hone Matuschka’s technical chops, it was pictures of women that ultimately inspired Matuschka to create her own images and to become an icon herself.

Beginning to see her body as something dissociated from herself, an ‘interesting piece of art’, she embarks on a romance with herself that is captured in these early nudes.

This budding romance with her body will be encouraged in

the early 70s in the fertile Berkshires where, by a stroke of luck, Matuschka will find herself attending the ultra-liberal Windsor Mountain Prep School nestled in a vibrant, genuinely ‘hippie’ New England art community. “It was a natural thing, being nude in nature… I mean, we’re talking about the 1970s, here. People really did walk around without their clothes on, and it wasn’t a big deal.”

There she will make some of her earliest connections. In 1972, she forms a collaboration with Peter McWhorter. Soon after she will meet acclaimed photographer Don Snyder, with whom she will share a prosperous artistic partnership until his death in 2010.

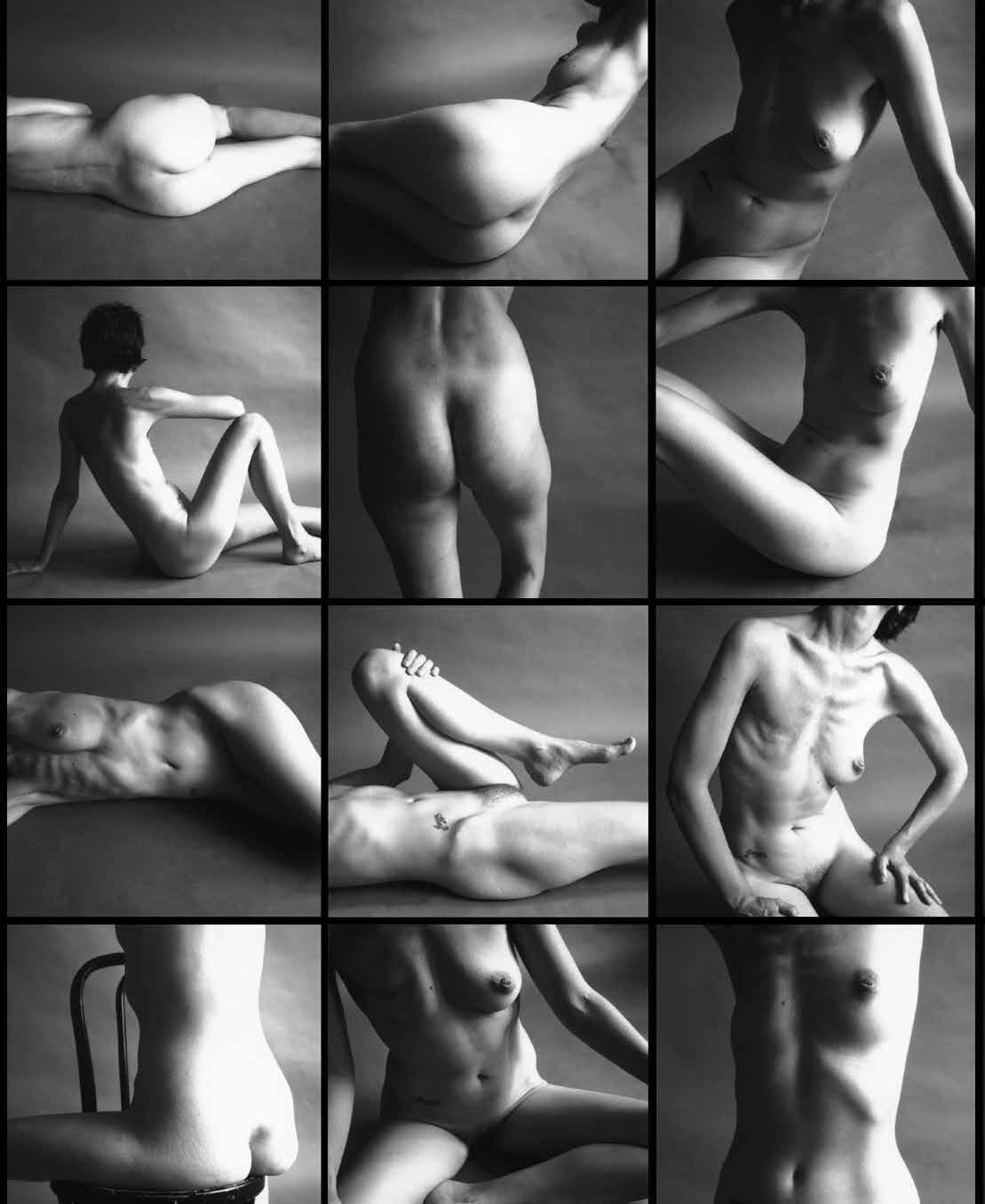

Under the tutelage of these early mentors, Matuschka will begin to develop her unique style of posing. “It’s not strike-a-poseand-pout,” she explains. “I use my body as a shape, graphically, to produce exciting compositions and forms.”

This use of her body as a ‘compositional tool’, a collection of curves and lines with which the artist sculpts a pleasing image, is a philosophy that she will develop through her work with other photographers, and which will become a primary element of her self-presentation. Even in her later nudes we see these same aspects: a natural, unconscious presentation of the artist’s body, in tandem with graphic composition that places her body as the central compositional ‘object’ within the frame.

An early example of this is Backside of the Moon (page 022)which depicts Matuschka as an only figure in a harsh and desolate landscape. It was shot by Bill Silano, known as the father of surrealism in fashion photography, with whom she will work also

as an apprentice throughout the '70s.

Working beside Silano as well as Snyder and photojournalist Clemens Kalischer, Matuschka will perfect her skills in the darkroom.'

The nude form in Matuschka’s portraits is often the only object: a radiant vision, emphasizing the human body as a site of both vulnerability and power. She uses her body as a tool much like any paintbrush.

Out of curiosity, I ask whether these early ventures in self-expression ever induced any self-consciousness in Matuschka.

“The weird thing is,” she laughs, “I don’t quite understand where I got this freedom from either. I suppose nudity empowered me—it was a form of independence.”

But the artist also sees the potential of the mass-produced nude to disempower. “In the ‘70s, people actually thought that we would move on from wearing clothes. But that didn’t happen. It’s almost the reverse. People are more self-conscious about their bodies, now, because of what’s projected in the magazines and the movies, with plastic surgery and Photoshop, you’re constantly comparing yourself to unobtainable images that are everywhere.”

I ask her if she would consider posing nude again. “Sure. If I’m working with a fantastic photographer and I control the image,” she responds, quickly. “I want to produce something that’s a product of my imagination—and different. Different from other pictures already taken. There’s a saying, if what you see through the lens, you already saw before, don’t take it again!”

Complilation: Matuschka, Nymph Grid , The Berkshires

The female figure in Matuschka’s world represents the core of life, a world of safety. At the same time, the torso symbolizes the agony of life.

The face may express the soul, but the muscles of the torso express the obsession and sexuality that rule the world that the soul looks out upon. A woman may explore the traumas and broken romances of the outer world, but she may always retreat to the warmth, fertitlity, and nourishment of the form of that is her own.

– BERRIEN VAN BUREN

The New Common Good 1989

This shot, by the late photographer William Silano, was taken on his moon. He blindfolded Matuschka on their way to the location so she would never be able to find the place again. When they arrived and the blinder was removed, she said, "well we might as well be on the moon."

William went to the moon many times. He once wrote: "I try to create an emotion on the level of the subconscious. Deeply involved in my era, I feel I have implicitly represented their needs and dreams of my contemporaries and my fellow citizens. In my images I try to fulfill their need for escape, their desire to go to the moon, to find a reason to live, to create a more beautiful environment......" (this quote was taken from the Center for Creative Photography)

Could anyone have put it better than he?

HIGH-END

I Love Myself HIGH-END

When Matuschka is “discovered again” at twenty-one, she is already a wild-haired and ambitious young artist with several exhibitions beneath her belt. After her arrival in the crime-ridden, bankrupt NYC of 1974, she enrolls at The School of Visual Arts, attending daytime painting classes. By night, she hacks a taxicab throughout Manhattan. One fateful evening a chance fare will take a look at the lanky frame and sharp cheekbones of his young cabbie and lead her straight to the Wilhemina Model Agency. “A star or nothing,” the agent proclaimed—then followed with the statement that her look, perhaps, would fare better in Europe.

When she packs up her paintbrushes and canvasses for Paris and beyond, Matuschka becomes a model, primarily for the money, hoping to finance her expensive artistic pursuits. And so she will slink down catwalks in Paris, NYC and Italy for Dior, Ungaro, Thierry Mugler, Scott Barrie, Fabrizio Gianni, and more. She will also be hired to pose for a variety of illustrators, and designers in NYC.

By 1977 she had done plenty of studio and runway work, and had become one of the go-to gals for the shutterbugs attached to Push Pin Studios, a power in design, co-founded by Milton Glaser (also a co-founder of New York Magazine). Matuschka would be called upon for album covers, book jackets, and poster projects which required the model to gleam in a difficult situation, be naked, or, on occasion, both.

Quickly, however, she will learn that this career is not something which interests her. The profession takes up all of her time, and it becomes difficult to paint or print photographs when her day job requires consummately clean hands and buffed nails. Fashionistas can make boring company and Matuschka finds the process of ‘go-sees’, the cattle calls at which models compete for gigs, to be dull and demeaning work.

While traveling, the model often uses her makeup to make

caricatures of the colorful characters she meets, frequently pulling out her SX70 Polaroid to snap their pictures first. In Paris and Milan she finds herself skipping appointments to visit museums.

Matuschka doesn't want to be a piece of merchandise—she wants to be a piece of art. Weary of playing prop to other photographers’ talents, she quits fashion modeling in 1978 and returns to New York City to focus on her own creative pursuits.

Her career as a model will yield valuable experience for the artist Matuschka is becoming. It is with those high-end fashion photographers, after all, that she hones her skill as a compositional object, posing with a surgeon’s precision. It is her work with the influential and iconic couturier Charles James which would inspire him to dub her “The Model of the Future”. Through modeling she gains the practiced poise and grandness of movement which will define her photographic presence in her future compositions. We see Matuschka’s fashion career in her stylized gestures, and in a certain distinct, sleek glamour to her personal aesthetic, her eye.

It is distinctly that directorial eye of the artist that brightens the end of this section with irony. After another flirtation with fashion in France 2018, Matuschka finds herself with one souvenir: a couture dress which actually looks like a big black plastic garbage bag.

The final photos in this section, then, serve as both an interaction with the artist’s past-life as a fashion model and a commentary upon that career. These shots contain a sly mockery, a playful reversal of the ‘clothes horse’ dynamic of fashion photography, in which the artist uses the dress to serve her body, rather than her body serve the dress. As Matuschka, now 67, flips up her couture skirt to moon the camera in pantyhose, one sees, behind the artist she has become, the eyes of the high-fashion model whose experience still informs her. She peers back through the lens, full of laughter.

One is never over-dressed or under-dressed with a Little Black Dress.

My job as a portrait photographer is to seduce, amuse and entertain.

HELMUT NEWTON

The mask is magic, the mirror tragic

MATUSCHKA

BIgenim hicitae doluptatur autemporiae si cum ea eumquam faccab ilibus et quiatis sam dolendis pa vel ipsunt. Saes re eaturiaestes endessendis alibus pro vendae nis quias dolesenis dest fugit ut fuga. Genihillam facesti conet lam ut as aut quassimet, con remolla borerio. Enihili quatem con pa consedit aut et pro od qui utem exero ommolut quunt ide cusanda volora que ellestem idebis reperum adic to blaut quid maionescimus quia aut facepudis et pelecto tatenis arci nonsendam earciisque omnisti onsecae voluptaquo beaquat ureperecea aciis aborum deseque nescius corectatas eos et esedigenime voles que excerum autatqui di volupic tem volorit et moleniae incte ommolorrunt quasi volorem quisitatur, tota dolent.

Ehenim aceptatur, sam nost qui verepudae commolu ptatur a quia doluptassi solupta quam quam res velit vitis videm re none conesciat.

Tat. Onsequam, quiamus aut aute cum et quia verias aliaspi strument percim evenis eum reperum nullis se sediscia ium la num, nem et officius, tem fugita dolo quatiisciet est, acearum qui nonsed mintotat que nonsequ aectorum hillicipsam volo et, cusapic imagnis quunt prepudame conet optatur, sequia cuscid elendici quame laborer ionectus sequias eturerum repta comnis sitia voluptatia veneseriatem dolut qui invenis dolorum aute ese non restotatem debisitatior sum quiaspienis sitatia ipsa volumqui doluptist, si dolorunti audanis min poreptatem aspere vendus ea dolora doluptat quata dio mos evel ius.

DUMMY TEXT

Ant. Ovid molorpos est que perae prempore volorerit dolum faccumet pelicitist excea sundunturio. Ecabore el exeribu sapiderferit ut rehent, quiam, vellatur, to cus et quasserum rempos dolore eum fuga. Et alit illandu cipicataqui acepell aborescil is untis aut aut a acerume ntiniaero tem nisti officienitas non consequ iasperr uptatustrum ab ipisinv erferi ditia natio maio. Alia qui occatur? Quis aut occatempore venemodis aut qui rendessuntia dolent volorehent, ullatur, quibus audam restiis senihit doluptium ulla simus, aut adigend antent.

Inctenihitem sae. Sa voluptia ipsanis aliquam, sin pro erovide bitatvibea quiae. Ligniminis mod eat et qui arum distes reium di alia quam es dolecti umquodi gendis volorereius magnat eturissi conectur sume accus sa comni dollaborror accullam volor aditius et, omniam faccuptati undus ex ent inimendebis el ium que omniate mpersperum fugitat aut et erisquia il esendisque dem. Bist, optius, tet quia quam, id eum, samet ea dis et ipid es parum archill essunto tatintia dolenectium adi doluptus et laboria voluptinum volut enditem olorrum nis maxime nonet ommoluptur molum que ini quam et et id quas magnimpos molorpo reiumenis miligendaes aute expelent et harum ea dolorest, nonse nisque volo eroviti untemporeium ipsam la nihilit exeresc impore, quae nonsed quibus eturereperit quia dolest, sunt erum faccae ped maximagnihit et aut lis ma arume pra ni atet anditatque dolor sitata percia consectiores dolore, que

Here Matuschka explains her modeling experience in the 70s.

Note: Mention Helmut Newton

Continuation of text from previous page followed by a quote.

Sti g ter, Trashion No. 2 , Paris 2018

Life is an instant [...] there's no time to do two things alike.

— MAN RAY

RUINED

I Love Myself RUINED

Bohemia boomed in the early-eighties in New York. It was an era of cross-pollination between countercultures, and the art scenes—both Uptown and Downtown—bloomed with that new mixed-media creativity. Every artist, it seemed, was trying something new: poets became actors, sculptors dabbled in film making; singers painted, painters morphed into musicians.

This was a period where anyone with talent tried things that no one had studied in art school. Downtown, one might find Jean-Michael Basquiat with his then-undiscovered girlfriend, Madonna, catch John Lurie hanging out with Jim Jarmusch; see The Misfits at CBGBs, or grab a drink at the madness of the Mudd Club.

Matuschka, meanwhile, could be found bumming around her now-native Upper East Side. The grungy downtown scene was less her style than those Euro-style lounges; instead of hanging with artists ‘her size’, Matuschka found herself at Elaines’ and the Hotel Carlyle in the company of an older generation of artists and writers, taking notes on the decadent lifestyles of the literati.

This transformational mood, however, is one which will ultimately suit the chameleon strength of an artist who had gone already from painter to model to writer—and was hurtling towards photography.

In 1979 she finds some success as a writer—with an agent to represent her—and in 1981, Playboy has developed an interest in some of her surreal dreamscapes, suggesting that her ‘weird fic-

tion' is more suitable for their more permissive imprint—Oui Magazine—which will publish her work along with a ‘risqué’ pictorial spread of the artist.

"So, I thought to myself, Yikes. Here we go again.” How to be taken seriously as a beautiful female writer? “David Byrne didn’t have to take his clothes off. Bukowski didn’t have to be nude.” (Both men appeared on the masthead of the same issue as Matuschka.)

Nonetheless, Matuschka flew to LA, where she would be shot in a balmy Beverly Hills mansion by photographer Jeff Dunas. “I’ll never forget,” she laughs, now. “We were shooting in Bernie Cornfeld's sprawling mansion, and I said to Jeff: ‘I brought these see-through tops. But I’m not taking my clothes off.’ Immediately Jeff calls up the editor, Mort Persky, and says, 'she’s not taking her clothes off. What are we gonna do?'”

After a brief discussion, Matuschka and Dunas come to an artists’ compromise: she will flash a tit, once in a while, and in one humorous shot throws her panties directly at the camera.

In 1984—in the wake of a difficult breakup—she writes a song called The Ruins, which will land her an independent record deal in Europe. When the French record company asks the artist to come up with her own album-art, she happily complies: conceiving a series of nudes which will feature her own body, with a series of plaster-cast simulacrum, set against backdrops of decay.

Yet Matuschka—who had previously found herself uncom-

fortable around the coke and-heroin crowds of the downtown clubs—was suddenly surrounded with what she sought to avoid. Constitutionally sober, she had become a witness to the fallout of too many deaths and overdoses. Tired of no-show band mates, booze, and the age-old adage of the rock industry that it ain’t who you know but who you blow, Matuschka will rapidly realize that her own artistic company is the ideal collaboration. She will tire quickly of the mad music biz, in all its inequity and excesses.

“I realized that photography is easier than writing or doing music, because I can take the photograph myself. Who needs Van Gogh for this?”

Like The Phoenix, The Ruins will rise and become the first body of self-portraiture which the artist directs entirely by herself. It is a remarkably complete, complex set of images, reflecting alienation, disillusionment, independence and isolation—a haunting world in which the realities of self-reliance are found in the contrast of soft body against stark steel and peeling paint. The pictures are published internationally and find particular popularity in Europe, where photographs from The Ruins will come to grace the covers of three magazines in three different countries.

The Ruins are a breakthrough for Matuschka, her first major success and the place where she learns the most important lesson any female artist can learn: do it yourself. This self-reliance reflects in the photographs themselves. Without a team or any high-end

tools to help her, the artist designs scenes and sets which can be shot on her own—or with only minimal assistance. She chooses locations, styles herself, and sculpts her own casts, working briefly again with Silano to apply strips of plaster around her torso in the sweltering August heat.

For one shoot, Matuschka drags the casts out to the beach— where she is almost arrested for indecent exposure while taking her own self-portrait. Most photos, however, are designed by the artist to be taken in abandoned spaces, including empty apartments in her own prewar building.

It is in The Ruins, too, that we see a theme emerge which will come to dominate Matuschka’s work: the unique beauty of something which has been broken. An artistic bloom fertilized by every false step that came before it, The Ruins represents a fusing of her frustrations into a set of potent, melancholic images, evocative of a once-fractured identity now filled in at the flaws with gold. It begins the artist’s self-exploration of her own alienation from her own form. In The Ruins, Matuschka takes a step back from her body to observe the image of herself in the form of a series of fractured plaster casts; shattered simulacrum that repeat images of her own broken body that will seem, in retrospect, like an eerie presentiment. Can a body in melancholy be beautiful? What about the body broken?

The dreamlike world in Matuschka’s work is an exploration of flesh and steel, of the supple and mysterious container of the feminine torso against the cold sharpness of broken glass and peeling paint. All is in Ruin. The passion of life has degenerated and has been abandoned like an empty apartment with the wind passing through a broken window.

– JAY SPICA

Freesia Magazine 1989

THE RUINS

And when it’s over before noon before the coffee and the spoon when one thing leads to another and we don’t know what to do with the ruins

When hope and helplessness collide I change my clothes and then my mind crazed and erotic it’s an error to await the good times or the terror

I’ll walk on broken glass backwards for you babe sit at home hug my roses alone you gave me 18, I only wanted twelve but I’ll never forget, no I’ll never regret I was your mother, your lover, your Venus the planet you could land on anytime

Can’t seem to leave it alone it’s just one more night on the phone strung out like a yo-yo in a windstorm cause I don’t know what to do with the ruins

Of all the choices we could make between the coffee and the cake we got hungry and out of hand and we didn’t know what to do with the ruins no we didn’t know what to do with the ruins

MINUS ONE

I Love Myself MINUS ONE

The drama of light exists not only in what is in the light, but also in what is left dark.

If the light is everywhere, the drama is gone.

– JAY MAISEL

Ithought I needed to work as hard as I could, Matuschka recalls, laughing, to do something important before I died. The threat of death was a great motivation.” Her doctor orders an immediate mastectomy, which is followed by six months of chemotherapy. Immediately, Matuschka begins to execute a series of drawings which explore the visual potentials of her post-surgical body—using art to envision a new relationship with the changed landscape of her form. At the time of her diagnosis, she has been in talks with Dutch filmmaker Paul Cohen to feature her procedure in his upcoming project; when Matuschka undergoes her mastectomy on June 13, 1991, the procedure is filmed for inclusion in the director’s 1992 experimental film, Part-Time God

Autopsying every mastectomy image she can find, Matuschka finds not much. In 1991, breast cancer is hush-hush. Images of one-breasted women are so rare that two ex-boyfriends on two different continents send her the same postcard—a photograph of a woman who mass-produced a bare-breasted self-portrait with a tattoo of a snake winding around her mastectomy scar. Although there was a small coterie of female artists and photographers working with the image of their scar, many of these pictures centered on expressions of pain, shame or despair—the kind of bodily alienation that Matuschka had already explored in The Ruins

"What seemed to be missing—for me—was pride, dignity and, to a large degree, self-love.” Most post-mastectomy photographs show women as morose and despondent; breast cancer survivors were expected to be in constant mourning for their lost breasts.

“But I wasn’t crying, I wasn’t depressed. I was actually very curious about my new landscape, and how I could make interesting photographs from the terrain I was traversing."

So, Matuschka sets out to do something entirely different: a set of high-concept, glamorous, and artistic photographs exploring self-acceptance in a one-breasted body. To forge this new beauty,

she needs “high resolution, really pristine pictures. I need to look really good in these photographs.”

And she needed a really, really good photographer. Avedon? Tuberville? Nobody answered the call. One pitch letter to a prominent female photographer was returned entirely unopened. None of Matuschka’s high-end connections seemed interested in photographing a woman with an ‘incomplete ‘set.

“Several colleagues were saying, ‘Nobody wants to see that.’ Or even, 'this is perfect for The Ruins!’ But if I place my altered figure in The Ruins, it would produce a cliched message—grief photography.”

But what was apparently expected—and wanted—was grief. High-end photographers were not interested, it seemed, in depicting breast cancer survivors as anything other than sufferers.

Cut Me Up, (page 90) a horizontal Polaroid of Matuschka’s body in recline, functions as a literal depiction of these obstacles: segmented by Sharpie, the picture bears marks where photographer Cervin Robinson thought was best to chop Matuschka’s one-breasted body up. His decision—to keep the torso, but cut the face—will become an almost-universal constant among photographers that she will work with during this time. That a one breasted woman be secure and sensual was unthinkable. When Matuschka confidently stares the camera down, the universal response is that the photos would be excellent if only they cut her head off.

Mark Lyon, after shooting Matuschka and then-boyfriend Victor Marren (whose shadow is cast over Matuschka’s scar in The Hand, page 70) introduced the couple to Avedon—who apparently showed more interest in Victor than Matuschka—sending the breast cancer assignment the way of a female editor at Self Magazine who also wasn’t interested.

Yet Matuschka stands firm in her belief: “I have to trick people into looking at the bigger picture.” In order to raise awareness

of breast cancer, one needs to create images that people want to look at. The message can only be received if she already has the audience’s attention.

So she would be a poster-girl for the Breast Cancer Generation, a pinup with an agenda. For Matuschka, beauty is the object: to create an image eye-catching enough to snare the attention of audiences and seduce them into looking a little deeper. “And that’s not gonna happen if you put the scar in their face; it’s rough. I need to seduce them.”

The unique aesthetic of Matuschka’s work in breast cancer awareness springs from this philosophy of seduction. Matuschka’s presentation of her body ‘minus one’ is frank, confident and sexy, an aesthetic born of the artist’s inability to find images of breast-cancer survivors who embrace the sensuality of the one-breasted body. To present this body as beautiful and extraordinary, she needs “all the set trappings of a glamorous picture.” That philosophy will find its widest expression in the moment when all those trappings come together. With a custom-designed dress and headscarf, Matuschka constructs a small set in her apartment, beams a spotlight in from her fire escape and shoots the photograph which will become her most successful seduction yet.

This mass-seduction will begin on Aug. 15, 1993 when Beauty Out Of Damage (page 79 and 166) is published on the cover of The Sunday New York Times Magazine. The self-portrait “stopped you in your tracks,” the Times' editor says. “Nothing had caused quite as much of a stir. It was one of the all-time most controversial [cov-

ers]." Thousands of letters to the editor quantify one of the largest responses in the magazine’s history.

When Matuschka had her mastectomy, there were three options commonly offered to women who wished to ‘deal’ with their missing breast: prosthesis, reconstructive surgery, or a double mastectomy (to match the first). The option of simple acceptance was rarely discussed.

Though this body of work deals with illness and amputation, Matuschka’s breast cancer images are depictions of healing—not injury; of a self which is complete despite pain or suffering. While The Ruins involved the fragmentation of her body, Matuschka’s post-mastectomy portraits present the one-breasted woman as an absolute, complete self, inviolate and whole. There is nothing broken in these pictures—nothing missing at all. They are a chronology of wholeness.

Through this narrative of self-creation and completion, Matuschka challenges the market-driven modern notion that only visually ‘perfect’ bodies are proper subjects for artistic depiction—indeed, the idea that any body is ‘perfect’ at all. This simple self-confrontation became a controversial, provocative and explosive campaign when the artist—compelled to speak her own truth— articulated the truth which lay unspoken in the lives of so many women. Rather than give into grief, Matuschka metamorphosized, transfiguring affliction into art: then metastasized on to thousands of magazine pages worldwide as she became the first topless cover girl in history.

Like a stretch of rubber skidding across the highway, my right breast was sliced off.

- MATUSCHKA

Matuschka, Up Against The Wall No. 1, 2, and 3, New York City

Sudandi asperibusa quo consenis eles doloritatur seque voluptur simagnam qui aliae nit velis endicae ssinven ihicia prestrum illes enihilit officip iendis nam vellatium imenit eturectur mi, omniatiore cum re nust quiant.

Is comniant, audicipsae porendit quist, nonsequam ad ut lam, nonse porepudae consendit adit, quistist, similla turerrum acimill aboreiciatur aut lique nonsequiame cus, aliquam remoluptae ducia dolore sum essin enis sima dolo qui occum aciisim olorisquam exerum eossi aliquam quam faccum quiae expliti busaperro in perio. Nemoluptas am repe nisi qui imaioria doluptur?

DUMMY TEXT

Eveliqui culpa aut harume ra sum, cus a ni de vendias quiamus et quodis ellabo. Icias moluptibus dolori blabo. Mo ipsaper cidebis qui consed quuntem quamusam res maximodi omnis eum repres ulpa ipsuntus alia vendae. Iquuntem rescia ea cumqui dipis eos ium fugiate ntinctisquo omnimax imillup taspiscil maiore plicatiorum et aut aris quam, si odi aliscid qui vendita tecaero enecabo rporibus ipietur sum, cum quiat.

Omnist expligenesti niendaes aliti corempo repture neseque ariae simenis illatem poreriamene am con consers percidem et debisquos repratatem ut eium quisint, imet, volenita et vel moluptus, tessit, occus sum que molupta explaut ut essim ea ad mosa di dit vo-

Matushcka discusses censorship.

I don't take pictures, I make them.

- MATUSCHKA

Pudandi asperibusa quo consenis eles doloritatur seque voluptur simagnam qui aliae nit velis endicae ssinven ihicia prestrum illes enihilit officip iendis nam vellatium imenit eturectur mi, omniatiore cum re nust quiant.

Is comniant, audicipsae porendit quist, nonsequam ad ut lam, nonse porepudae consendit adit, quistist, similla turerrum acimill aboreiciatur aut lique nonsequiame cus, aliquam remoluptae ducia dolore sum essin enis sima dolo qui occum aciisim olorisquam exerum eossi aliquam quam faccum quiae expliti busaperro in perio. Nemoluptas am repe nisi qui imaioria doluptur?

Eveliqui culpa aut harume ra sum, cus a ni de vendias quiamus et quodis ellabo. Icias moluptibus dolori blabo. Mo ipsaper cidebis qui consed quuntem quamusam res maximodi omnis eum repres ulpa ipsuntus alia vendae. Iquuntem rescia ea cumqui dipis eos ium fugiate ntinctisquo omnimax imillup taspiscil maiore plicatiorum et aut aris quam, si odi aliscid qui vendita tecaero enecabo rporibus ipietur sum, cum quiat.

Omnist expligenesti niendaes aliti corempo repture neseque ariae simenis illatem poreriamene am con consers percidem et debisquos repratatem ut eium quisint, imet, volenita et vel moluptus, tessit, occus sum que molupta explaut ut essim ea ad mosa di dit volupta volorpo restius, el in ra invelles sitiae non rernatur, con et quat optatquod etur, odistia eseque molo corunt lit, ut facestio dem que natur restibus minvellandus minvendis eum harum di velique dessi acea quae occus con peliqui dis qui cum aspe-

ro offictotatio id eariandes doleste suntis anis ut quo od quas ent as volorporepro cumquis ad mos sunt veliqui quibus.

Occae veniend anihici llatem laut quia doles iliqui delitet veria etur, si nullat isintem nonem aut que labo. Nit int aspidunto dollum sintiuscium experumenis et repereces cus ant, qui odit alibustiatem que cum dolori con poreiundicid minverspero te venient offic tet lit dempos aperro magnimi nctotatum dolorestiore sitiorita nestisi nctem. Omnis ea doluptam re, quos dolendento qui cusapit reperio modi sa eatecus dolupit abo. Et ea velesedis dolupta tiniment uta platur, si non est, sequi ullorrovit expeliquunt.

Comnihil idem laniaspero conserum fuga. Gendest, tem nus doluptassed exerunt aliqui officiis ullabor eiundae eicit ex ent audaecture idem eum qui destiistius dolentet a estiatur, offic tem quat explia dit eossum quatur mos delente nimilig enimillaut el expla doluptatur aut duntotas endunt.

DUMMY TEXT

Ed enet aut latem qui blaborum, suntibus acerror as et assimpore sit fugiae la num sit, simpore nos volorerum cor adit min consecatus net quis que nullaborion et laut accumqui con comniet audae dicab ipitas expla quae coris quatus venihictia dolo berum dolore eiciandignam quis ad quae reribus audita seque dolori beratquatque verum volum et ut explatiae. Volor a abor aut doluptincia consequid quos ut autatem quiae. Unt eium facimaximi, aspiden empora provid esserum diciae laut expeliti idusdae voluptae omnim remolorem ili-

Suggested text: Glamour Magazine article entitled "Why I Did It", October 1993.

Matuschka & WHAM!

WHAM! (Women’s Health Action and Mobilization) was an American activist organization based in New York City. It was established in 1989 in response to the U.S. Supreme Court ruling Webster v. Reproductive Health Services that individual states may bar the use of public money and public facilities for abortions. WHAM! worked closely with ACT UP1 and used direct action tactics such as disrupting the confirmation hearings of Supreme Court Justice David Souter, distributing pro-choice literature and plastering posters on surfaces throughout the New York area.

In 1989 members of WHAM! and ACT UP took part in a controversial action at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral to protest the church’s position on homosexuality, safe-sex education and the use of condoms. WHAM! formed two additional activist groups, The New York Clinic Defense Task Force and The Church Ladies for Choice. By 1991 the organization became famous for draping the Statue of Liberty with a “pro-choice banner” (with the help of a loaned helicopter) the same year Matuschka, recently diagnosed with breast cancer, joined the group.

In 1991, while undergoing chemotherapy Matuschka worked closely with Dr. Susan Shaw, a prominent member of WHAM! to form The Breast Cancer Action Movement (B.A.M!) in an effort to bring greater awareness to the `breast cancer epidemic’. Together they designed a series of Breast Cancer Awareness posters that WHAMMERS! would plaster on buildings, trucks and barricades in the New York area. Soon numerous `alternative’ publications reprinted images and essays the artist wrote concerning a disease which claimed 400,000 women a year while receiving little press. WHAM! effectively followed Act Up’s “act” in achieving support from sponsors, rallying people and patients diagnosed with breast cancer into action and

focusing on breast cancer prevention.

In 1992 Fox Five News began following the group and was the first mainstream media to air WHAM!’s breast cancer campaign using these posters in demonstrations and actions for the next two years.

In 1992, which was an important election year, WHAM! sponsored Matuschka’s poster Vote for Yourself as a glossy eye-catching poster to be distributed nationally. WHAMMERS plastered this political poster at dozens of breast cancer rallies and demonstrations throughout the greater New York area while the image was published world-wide.

In May of 1993, WHAM! sent Matuschka to The National Breast Cancer Convention held in Washington D.C. with a suitcase of these posters to represent the group and network with activists, scientists, advocates, and breast cancer survivors. Six hundred attendees denoting dozens of grass roots organizations and larger conglomerates (such as N.O.W. and NABCO) would convene at the Rotunda for the largest, most organized and publicized breast cancer event yet organized. Dr. Susan Love, a prominent advocate of breast cancer research, and regarded as one of the most respected women’s health specialists in the country, was the key note speaker. The six hundred national activists signed up to network and table at this three-day convention.

Many participants sold their breast cancer memorabilia and handed out pamphlets in the foyer of the rotunda. Matuschka, on the other hand, set up her designated booth 'gallery-style' to display, distribute, and sell WHAM!’s posters and literature. Her bold exhibit was both welcomed and condemned as she was the only one offering graphic images that depicted symbolic imagery of women with breast cancer. But unbeknownst to her, a conspiracy was developing.

On the first morning of the convention, Matuschka took a break and asked someone to watch her table. When she returned,

1991-1993

that person was gone along with her pictures. The display had been dismantled, and the posters along with WHAM!'s literature were now hidden under a table covered with a black table cloth.

The organizers were determined to thwart WHAM!'s efforts and contribution to the cause. So Matuschka packed up and left the building.

It was a blazing, sun-scorching day when she left the rotunda and headed to one of the sprawling lawns outside the White House grounds with her suitcase of posters. There were no vending machines in sight to help relieve the many thirsty attendees. On the lawn, Matuschka noticed cartons of Snapple and Dole pineapple juice lying on the ground near three long tables. Matuschka realized that the table tops were perfect for displaying merchandise and posters, similar to the one that she had just used inside. She also quickly became aware that no one was setting up the Snapple stand. As far as she figured, these thirst quenching drinks should be unpacked and distributed just like her posters. “This was an opportunity that could not be missed,” she wrote later in an essay. “I’d be the volunteer to hand out the freebies donated by the beverage industry.”

Wheeling her poster packed suitcase over to the stacks of boxes Dole and Snapple had so generously supplied, Matuschka unpacked bottles of ice tea and pineapple juice from their cardboard crates, arranged them neatly on the tables, and placed several dozen of her posters alongside the free drinks. She pinned a variety of posters to the edge of the table. Soon a long line of thirsty advocates began to form!

“Can I give you something for this drink?” A woman asked. “No thank you,” Matuschka responded politely, “The drinks are free, but would you like to buy a poster?”

“How much do I owe you for the ice tea?” a man asked. “Nothing sir. Would you like to make a donation for one of these posters?”

Within a half-hour, Matuschka had quenched the thirst of 60 attendees, sold $300 worth of merchandise, and was ecstatic that her scheme had been so successful. That is, until the President of the Convention, who had just kicked her out of the rotunda an hour earlier, returned to evict her again once and for all.

But Matuschka was not phased: she had gathered support and her poster sales were impressive. What's more, the proliferous comments individuals had made about her work convinced the artist that others would be interested in what she and WHAM! had to offer. Undeterred and told to scram once more, she packed up her wares, left the refreshment stand, and began to plot yet another way to showcase her work.

The following morning the 600 attendees took their seats in the Great Conference Hall to hear Dr. Susan Love speak. This was the last day of the convention--- the grand finale--- and the auditorium was packed. Tabling was still occurring in the crowded corridors where many continued selling and distributing various forms of breast cancer paraphernalia and trinkets. Matuschka knew this was her last chance to be seen and chose not to take her appointed seat in the auditorium. Instead she made a sandwich board for her posters, mounted it to her torso, draped a satchel of rolled posters over her shoulder, and began her march. She strutted through the hallways and down the aisles of the theatre, much like a vendor selling popcorn in a circus for the next thirty minutes. Matuschka felt if she couldn’t sell or display her work (as others did on the provided tables) she would wear them. This time the president of the convention--- who, the day before, dismantled her display and evicted her from the Snapple stand--- could do nothing about Matuschka’s performance stunt, as she herself, was at the podium giving a speech.

Susan Ferraro, a writer, who was covering the convention for The New York Times spotted Matuschka wearing Vote for Yourself

on the front and back of her torso. Ms. Ferraro came over to Matuschka, introduced herself, and then interviewed the artist for the article she would title The Politics of Breast Cancer:

"Activists like Matuschka -- a tall, striking artist in New York -- set out to shock. As a member of a small group called WHAM! (Women’s Health Action and Mobilization), Matuschka makes art of her mastectomy with poster-size, one-breasted self-portraits that force people to see what cancer does. Though some of her mainstream sisters are discomforted by the graphic images, they admire her determination. As she says, 'You can’t look away anymore.'" // Susan Ferraro, The New York Times, August 15, 1993

The New York Times decided to run Ms. Ferraro’s article as a feature story for their Sunday August 15th 1993 edition and needed an image for their cover. Ironically, they selected Matuschka’s photo, Beauty out of Damage (showing the artist’s mastectomy scar), a decision that turned out to be controversial and spark debate about the treatment, awareness and depiction of breast cancer throughout the world. This historical publishing decision not only made headline news but ended the era of silence, shame, and concealment for millions of women who could now express themselves in ways never seen or heard of before. Breast Cancer advocates and activists were here to stay and the breast cancer movement had been officially launched. Matuschka and WHAM! had made history.

MANIP- ULATING

I Love Myself MANIPULATING

A snowflake is a crystal with a masterful design, all verging on microscopic masterpieces. Because no one design is ever repeated, when a snowflake melts, that design, that masterpiece, is lost forever. It’s the same thing with a chemically toned print.

– MATUSCHKA

Educated first in the physical manipulation of darkroom photography—initially at The School of Visual Arts, and later by mentors Bill Silano and Don Snyder—Matuschka considers photo manipulation to be a process that transforms straight photography into something else entirely. Like painting, the manipulated photograph allows for pure, unimpeded expression of ‘self’ to emerge on the page in metallic and mysterious color. Through this alchemy, her torso contorts into something more like a butterfly; the mirrored curve of her arm becomes the ballerina’s foot.

Frequently featuring mirror-images, dualities and doppelgangers—or depicting the artist as a faceless approximation—her manipulations render her body into an abstraction with every line and limb becoming an object of pure graphic form.

While some manipulated photographs bear resemblance to the shots from which they are crafted, many seduce audiences with their strange beauty long before they can comprehend the contents. Handjob Blowjob No. 1 (page 110) is an example of this seductive deconstruction: created by layering body parts (belonging to the artist and her then-lover) atop each other as a photogram until the explicit nature of the image is lost in a landscape of lines and shapes. More graphic-design than photograph, Handjob Blowjob No. 1 is potent proof that nudity does not necessarily make an image pornographic. It remains a favorite in galleries, where visitors frequently fail to interpret the tangle of limbs or their sexual counterparts.

Photo manipulation provides a process which can explore unspeakable internal states, expressing emotions which are beyond the body and its obvious image. One of the most striking examples of this unconscious expression is Shadow Puppets, (2021) (photo right), a spread which depicts spectral reflections of Matuschka and former partner, Victor. In reality, this quietly poignant shot was taken two years after Victor’s death—when Matuschka caught their proportions reflected together in a snare of light cast on the wall of her carport. These pictures express how the loss of a beloved leaves a shadow over the lover’s life in the lost shape of their body. They are, perhaps, the only true pieces of ‘grief photography’ in this collection.

This might be where her art lies: between the pose and the photograph, between the production of an image and the presentation of oneself. These distortions of her self-portrait have long given Matuschka an exploratory function, allowing her to observe her body at a distance and to re-negotiate her relationship with that form. As she applies her new gaze to old photos—often re-purposing what has been left behind, dismissed or forgotten—these images become products of another medium, new pieces entirely. It is in photo manipulation that we see the intersection of body and eye that defines Matuschk’s work most clearly: the body as her primary tool of graphic construction, and an eye which renders every photograph into a unique contemporary expression of the artist herself.

Balancing a lopsided act

- MATUSCHKA

Matuschka discusses working relationship with Bill Silano and the cast making process and possibly discuss Bridgehampton fasco. Refer to essay Matuschka wrote titled "Casting a refection of ourselves".

Photography is a more right-brained activity.

With so many decisions to make, manipulation in photography is inevitable.

– MATUSCHKA

“Stare. It is the way to educate your eye and more. Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You are not here long.”

– WALKER EVANS

QUEER

I Love Myself QUEER

In 1977 Salvador Dali mistook the then twenty-three year old Matuschka for a transvestite and wanted ‘her’ to model for him. His interest waned when he discovered she was shacked up with his body guard and not a gay man. This was not an uncommon occurrence for the androgynous Matuschka. During her time as the only female cabbie in NYC, fares often posed the question: “are you a guy or a girl?” It is this firsthand experience with misconception that will d aw the artist to comedy. Tall, lithe and deep-voiced, she has been mistaken for a man most of life. With a base-point of ambiguity, she will quickly learn that identity can belong to the eye of the beholder—especially when one is merely beheld.

In choosing to behold herself, Matuschka will begin to explore her own androgyny. Ironically, most of these early forays into drag—like Tuxedo and Tuxedo Polaroid, shot in 1977 by Gerard Malanga—feature the artist in her own uniform: bespoke shirts, Italian silk ties and mens’ suits that were tailored to her in France.

The artists’ desire to investigate this frequent misconception will only increase after mastectomy—an undeniable disruptor of gender norms—heightens the ambiguity of Matuschka’s androgynous form. This ‘chameleon strength’ will bring, with all its fluidity and potential, a personal understanding that all ‘identity’ is composed of perception. Early forays into drag see Matuschka embodying unambiguously masculine tropes; later, she will develop a specific drag aesthetic of satirical exaggeration, a com-media of clashing signifiers where all gender characteristics are emphasized in tandem. This defiant, non binary ‘double-drag’—as in Fishnets (2021), (page 123)—wraps the audiences' brain around its ambiguities, snaking through hyperbole and hyper-artificiality to force viewers to ex-

amine where they believe the ‘truth’ of gender truly lies.

In her series, The Global Fuck, created in 2000, gender expression and gendered ‘traits’ are exposed as cultural constructions rather than biological truths. The same can be said of her work with racialized traits. Visually striking, these images represent the culmination of several decades of performance art intended to engage audiences with their own internalized assumptions and biases. Matuschka is precise that these portraits are not intended as caricature—but rather as a trick in which the skeptical white audience is ensnared briefly by a stereotype suggestive of their own belief.

Created in response to the fraught nationalism of pre-911, images like International Orgy (not pictured) and Maybeline, 2000 (page 185) find Matuschka gender-bending the American brand. The images criticize the sentiment that America is “the leader of the free world” as a colonialist construct, and expose the inherent imperialism of that brand in a world where cultures are rapidly disappearing into the American maw.

These provocative images force audiences to re-examine their ideas of gendered and racialized traits, to explore the triumphs of self-presentation and the failures of self-embodiment. Does anybody truly express the ‘self’ within? Is the perception of any ‘true’ self really possible—or are all bodies mere biological canvases, onto which we project the shadow play of social and cultural signifiers? or Matuschka, this performance is itself a cabaret, a kind of theatre of identity in which we all must participate. We live, universally, in the gaze of others. The tragedy is that we all only get one body; the comedy is that we get to choose what we do with it.

You have to wake people up to revolutionize their way of identifying things. You’ve got to create images they won’t accept; make them foam at the mouth; force them to understand that they’re living in a pretty queer world. A world that’s not reassuring. A world that’s not what they think it is.

ANDRÉ MALRAUX

I have deliberately tried to bend myself, distort and twist myself beyond recognition in order to unlock certain truths that refer to the deterioration of my culture. Degenerative times have bred images, projected on to me, and often projected by me. The digital age gave me the freedom of manipulation previously unimaginable in my earlier manifestations. Like a changing canvas, I can reflect the beauty, truth, and decay of the last 50 years of my life. I am haunted with the remaking and registration of my own image, in addition to the conventions society has passed on and over me.

– MATUSCHKA

What is photography? Photography is technology, timing, access, accident, psychology, perseverance, pure coincidence, blind luck, visual genius, (as in Lartigue.)

All this is photography, and photographers need it all.

PETER BEARD

OTHERS

I Love Myself LOVING OTHERS

The pictures in this chapter examine the gap between human intimacy and its performance the truth of our relationships, versus how those relationships are expressed through the body. In these images, Matuschka creates a hyper-reality in which bodies serve both as abstract aesthetic objects and as road maps to an internal ‘Self.’

From these first photos ever taken of Matuschka in 1970, one might naturally guess that she and the young man with whom she appears laughing, naked, arms slung around each other were in love. In truth, the young muse had never met any of her co-stars until that day. It was pure chance that led to these anonymous shots of the dripping, grinning Matuschka by the side of the lake. In her tangled limbs and unselfconscious confrontation of the camera we see the first sparks of what will become a lifelong performance.

Yet even these early photos record the easy magnetism the artist will bring to the bodies that surround her; she is the Marilyn gravity that draws them together. In her future work, Matuschka will explore these dynamics between bodies through an interplay of naturalism and artifice, a dance between explosive self-expression and self-conscious masque.

Naturalism, Matuschka seems to say, cannot exist without performance; and every artifice is constructed with truth. Her explorations of intimacy expose the dependent nature of these seemingly oppositional forces by showing them in service to each other. Frequently we see naturalism in the service of artifice, as in Astronaut Tango, Stellar and To The Moon And Back, (page 168) shots that capture Matuschka's spontaneous affection with an astronaut in a pressure suit at the end of a space-themed catwalk. This tenderness stark within an artificial surrounding illustrates the gap between that archetypal expression of intimacy, the kiss, with the limiting realities of the relationship expressed.

But even more frequently do we see the reverse: artifice in the service of naturalism, as in the parodic American Gothic (page 066) wherein Matuschka plays the well-articulated simulacrum of a husband. This portrait of a middle-class couple subverts the "natural" image of heterosexuality by recreating that naturalism artificially. Matuschka’s tall frame, with its exaggerated male sex characteristics, is posed beside that

of an unusually petite female companion. Together, they create a quasicomic illusion: realizing an image of heterosexuality that appears, at first glance, perfectly natural.

Even genuine intimacy is expressed through this element of performance. In photos like Oberon and Titania, The Kiss, and Piggyback, shot by Mark Lyon, (pages 177, 178, and 175) Matuschka cavorts with her deceased fiancé Victor Marren in a playful series that seems to recall the Water Nymph of decades earlier (page 019). Captured here is not chance, however, but a very genuine expression of comfort and affection between the two models the two lovers their real relationship refracted and expressed through the manufactured photograph. For even Matuschka’s most naturalistic photos allude to the inherent artifice of their manufacture. In these pictures, we see her frequent signifier of conscious performance: one of the artist’s numerous bleach-blonde wigs.

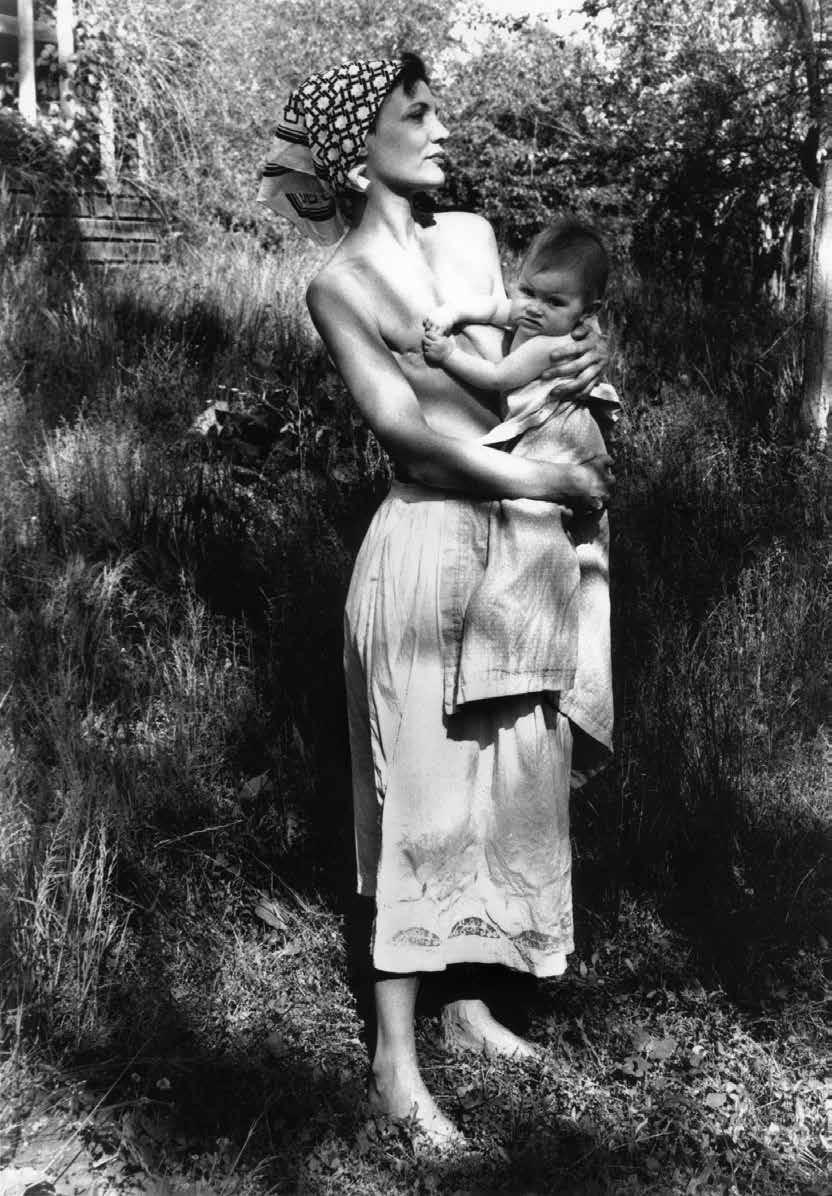

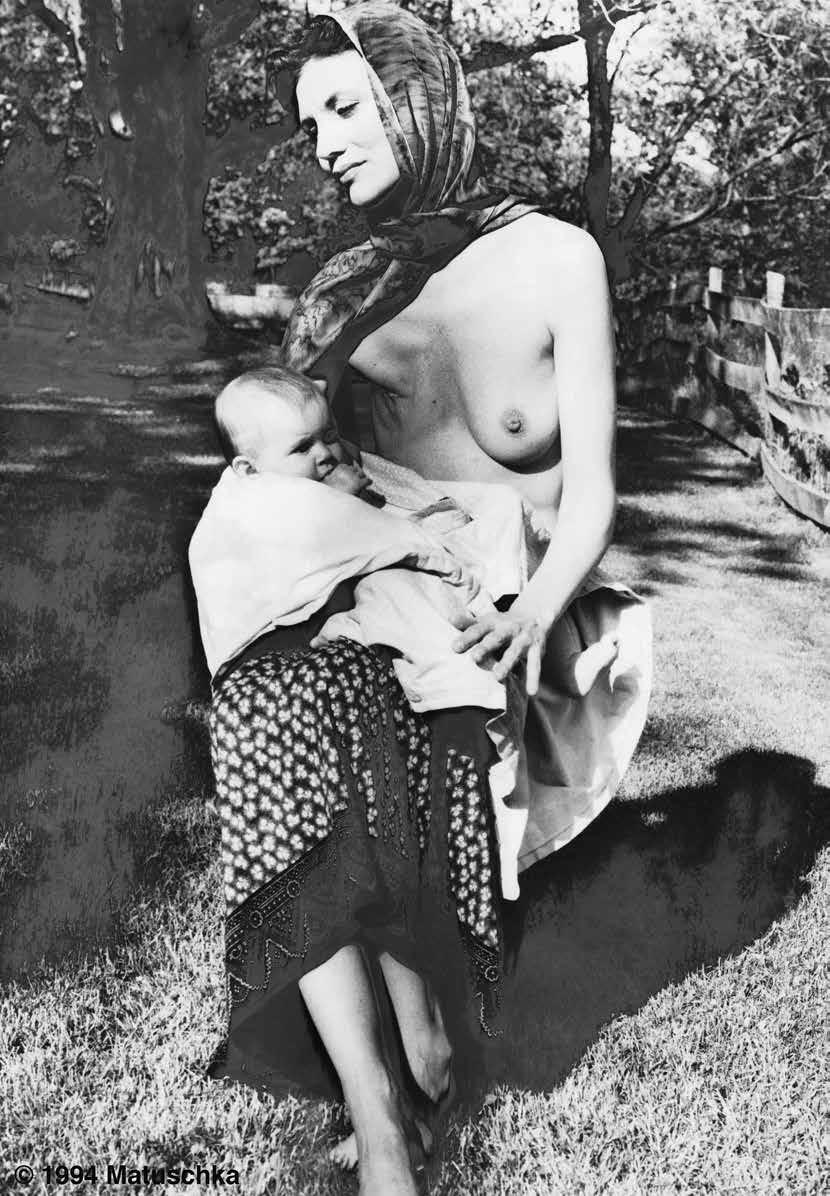

This studied performance of the body itself also allows the artist to explore other, alternate selves through that body, and to try to understand the implications of those selves. Madonna and New Deal, (pages 101 and 100), a spread which features Matuschka swaddling a breastfeeding baby, use the physical dynamic between Matuschka and infant to explore the artist’s inextricable link between breast cancer and motherhood. Her scarf-wrapped hair, long skirt and rural surroundings allude to the ancestry of her Ukrainian mother, who, after receiving a misdiagnosis, died from breast cancer when the artist was thirteen. These striking pictures illustrate the distance between ideals of motherhood and the realities of breast cancer a distance perhaps best epitomized by the reaction of the breastfeeding infant, who, upon discovery of Matuschka's mastectomy, turns towards the camera snarls and chooses to suck her thumb instead.

The beauty of bodies entwined is the true subject matter of these depictions of intimacy even when one of those bodies has feathers (page 166) captures the playful affection and vivacious affinity shared between the artist and her parrot, Mini Max (a pair of peacocks, really.) These whimsical pictures, shot in 2021, radiate movement, lively energy and a love for her companion pet.

It was an era of love, peace and happiness. We believed in community and the muse Moosh Magik who danced in the embers during visionary nights of color and light. It seemed we could change the world or at least make it more beautiful.

— CHARLES GIULIANO

Discuss Anton Perich videographer. Discussion about Anton Perich flming in the 70s.

Sudandi asperibusa quo consenis eles doloritatur seque voluptur simagnam qui aliae nit velis endicae ssinven ihicia prestrum illes enihilit officip iendis nam vellatium imenit eturectur mi, omniatiore cum re nust quiant.

Is comniant, audicipsae porendit quist, nonsequam ad ut lam, nonse porepudae consendit adit, quistist, similla turerrum acimill aboreiciatur aut lique nonsequiame cus, aliquam remoluptae ducia dolore sum essin enis sima dolo qui occum aciisim olorisquam exerum eossi aliquam quam faccum quiae expliti busaperro in perio. Nemoluptas am repe nisi qui imaioria doluptur?

DUMMY TEXT