Exploring outdoor gear design with BEN GUTHRIE

drew

I grew up in Seattle, not far from campus. I was always drawn to making things, building with Legos, spending time in woodshop and taking things apart just to see how they worked. When I first got to UW, I actually started in engineering because I liked math and the technical side of building. But after a few quarters, I realized I missed the creative, expressive part of making. I took some architecture classes next, which got me back into drawing and thinking about proportions and structure. But what really clicked for me was an art class DES 166 where we had to build a stool out of one piece of cardboard, no glue or fasteners. I remember being completely absorbed in that project. That’s when it hit me, this is what I wanted to do. That’s when I found industrial design.

What were the most valuable things you learned during your time in the UW design program?

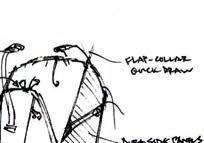

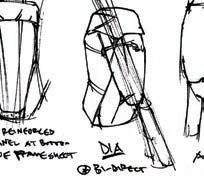

There were a few lessons that really stuck with me. The first was the importance of sketching, not just for making things look good, but as a tool for communicating ideas quickly. You don’t need to be creating perfect renderings; you’re showing how you think. The second was understanding the process, learning to respect research and iteration. In school, I didn’t always love the early research phases, but later I realized that’s where all the insights come from. If you skip that, your design has no foundation. And finally, critiques were huge. They were intimidating at first, but learning how to take feedback, and how to give it constructively, made me a better collaborator. That’s something I still rely on today. It’s how we push ideas forward.

"It may sound obvious, but getting the hard skills down is very important."

What were the strategies you used to look for work after graduation?

When I graduated in 2009, it wasn’t the best timing. It was the height of the recession, and competition for design jobs was fierce. Eventually I pushed through and made it, but it was rough for a while. I poured a lot of effort into my portfolio, which can feel like a neverending project. I made sure each piece had a clear focus highlighting a particular skill or showing range, and tried to make every project tell a story, because that makes your work much more engaging to present. Once everything was ready, I got out there and started meeting people.

How did you get your opportunity at Smart Design?

I tried to keep things casual when reaching out about design jobs. At an IDSA event, I met Allan from Smart Design, who encouraged me to send over my portfolio and teaser. He later emailed back saying “Great work!”, which was huge for me. I also connected with another Smart designer, UW alum Shannon Fong, through LinkedIn. We met for coffee, and she gave me really helpful portfolio feedback. Thanks to both of them, I was invited to interview for Smart’s next internship. The interview was low-key since I’d already met them—I walked through my portfolio, shared a small model I’d made, and the whole team was incredibly welcoming. Afterward, I sent a thank-you note with a funny illustration of some terrified potatoes staring at an OXO peeler—a little nod to one of Smart Design’s iconic products.

supporting automotive clients like Toyota and Tesla. I became the “go-to sketch guy” in brainstorms, quickly visualizing ideas and learning a ton from the engineers about materials, manufacturing, and how to design plastic parts efficiently. After about a year, my boss left to start what eventually became Fathom and brought me and a few others with him. At Fathom, I wore a lot of hats— leading product design while also handling branding, and visual identity work. One of the best parts of Fathom was the prototyping setup: a full woodshop, spray booth, multiple 3D printers, and a desktop injection-molding press. Having all those tools taught me a lot about fast, hands-on iteration.

devoted to outdoor gear, especially bags. There’s a the industry, and write critical reviews of new products. I emailed the authors there, and asked how I could learn how to design soft goods. When they wrote back, they said there was really no specific school or resources to learn

great blog called Carryology—they interview designers in how to design bags. Essentially, their response was, “You just have to learn on the job.” That was disappointing—I was really hoping for some book they could recommend or something. So I just tried to immerse myself fully in the world of soft goods. I bought a sewing machine, and a copy of “Sewing for Dummies.” I started sketching sleeping bags and other cut and sew type products.

and told me they liked my skills and thinking, but were

I got a message through my Coroflot portfolio asking if I was interested in a full-time equipment design contract role at The North Face. I honestly thought it was spam at first, but it turned out to be completely legit—the person who wrote me is now my current boss. I went in for an interview a few days later, but I didn’t get the position. They were upfront concerned about my limited soft-goods experience. Still, the conversation was great, and they gave me valuable feedback on how to strengthen my portfolio and projects. I took all of that to heart—updated my work, added more projects, and kept in touch. Six or seven months later, I reached back out, and they happened to be hiring for another contract role. I interviewed again, and this time I got it. I was so stoked—this was the moment I’d been working toward. I finally broke into the industry.

Have you worked on other products besides backpacks?

but I wanted to bring

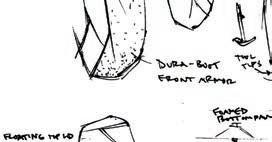

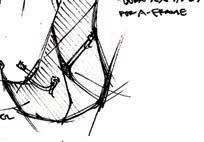

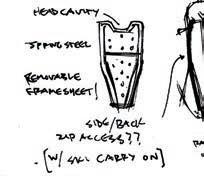

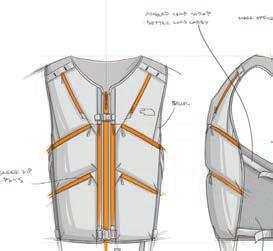

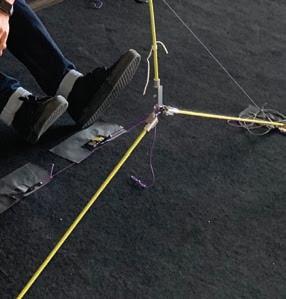

This is still within Equipment, some of my prior hard goods experience to the table and show people at The North Face what I was capable of making. So I started sketching and modeling out custom hard goods—trims that go on the bags like zipper pulls, buckles, cord locks, etc. The next season that zipper pull was adopted by a bunch of the apparel departments and put on all kinds of jackets. It was very inspiring to see it spread across the entire North Face brand. In Snow Sports I worked on jackets and bibs for ski patrols and mountain guides. But my main project was designing a new ABS safety vest for backcountry skiing and snowboarding. If you get caught in an avalanche, you can pull a little trigger on the vest. Airbags inside the vest inflate and help you float to the top of the avalanche so you don’t get buried alive.

in Equipment, mostly focused on bags and backpacks. But my first project ended up being a redesign of their stuff sacks. Stores like REI didn’t have room to display full tents and sleeping bags, so customers only saw plain sacks with tiny labels. I changed the sack to a triangular shape so it stacked better, added clear graphics showing what was inside, and included feature callouts and fabric swatches— all while staying under an eighty-cent cost constraint. We even used leftover scrap fabric for the handles. After that, I moved into backpack design full time. I worked on everything from back-to-school daypacks to sleek urban packs and heritage-inspired styles. Eventually, I transitioned into technical packs, which became my favorite—lightweight, performance-driven designs for hiking and climbing. One of the best parts of working on technical gear was collaborating with TNF athletes. We’d give them prototypes to take on expeditions, and they’d come back with brutally honest feedback—sometimes the packs were shredded, sometimes they loved them but wanted specific tweaks. That direct athlete input made the design process incredibly authentic and added real credibility to the products.

Can you describe your typical day as a design director?

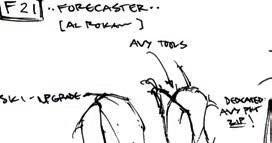

Typically, at the beginning of a season, the product managers and the product director on my team will figure out what new products we should design for the next season. For example, they’ll want to redesign a few of our commuting daypacks, or they’ll want to add new packs for traveling. The product folks are merchants—they study the markets and manage the product line. They write initial briefs that the entire Equipment Team will discuss back and forth for a few weeks. Then, we have a big kick-off called the “Hoe-Down.” After the Hoe-Down, at the beginning of the design process, we have a lot of brainstorm meetings across departments. We really like to meet with designers from footwear and apparel. They’ll often have a direction that they are excited about. Their ideas might inspire us to do something new or change our own direction a bit.

How do brand values guide your design decisions?

You’ve worked in both consultancies and in-house teams—how do they differ, and what do you enjoy about each?

I started my career in consultancies, and that turned out to be a great foundation. In the consultancy world, you get exposed to a huge variety of projects, products, timelines, and disciplines. The pace is fast, and you learn a ton in a very short period of time. That breadth helped me figure out what I actually liked working on—I found myself drawn to tangible products I could understand, use, and connect with, which is part of what led me toward outdoor gear and equipment design. Working in-house is a very different experience. You usually have more control over the work, more ownership of the product, and you’re not constantly adjusting to client demands. The pace is still busy, but not as intense as consultancy timelines. Coming from fast-paced studios set me up well I entered in-house teams with a wide range of skills and the ability to move quickly. Both environments have their pros: consultancies give you massive exposure and rapid learning, while in-house roles offer deeper focus, more stability, and, in the outdoor industry at least, a more relaxed culture. For me, the combination of both has shaped a career path I’m really grateful for.

Hardwear and The North Face, the biggest difference comes down to scale and how that impacts design. The North Face is a massive global brand, which means roles are highly specialized—every small function has a dedicated person handling it. Mountain Hardwear, on the other hand, is much smaller, so the team is leaner, and everyone wears multiple hats. Decisions feel more collaborative, and there’s a stronger sense of ownership over the work. In terms of brand ethos, The North Face originally focused heavily on creating the best technical products, which aligned closely with my own design philosophy. Over time, however, the focus shifted toward revenue-driven, high-volume products, sometimes at the expense of technical innovation. Mountain Hardwear, by contrast, still embodies that original technical-first ethos, there’s a clear commitment to making best-in-class products in every category. That makes it easier to design authentically, ensuring the products truly reflect the brand’s identity.

actually a really interesting challenge. For example, if you remove one sense, like sight, how can someone still navigate and use a product intuitively? Take a tent: how

zipper pull to open the outer door instead of the inner mesh door? We’ve started thinking about these tactile and sensory cues more intentionally—like incorporating haptic feedback, so you can feel the click of a buckle or snap, or using texture and material contrast to communicate

compartment might have a distinct feel compared to the smaller pocket zippers, allowing someone to know what

design process—especially during ideation and review— about how we can design with disability in mind. It’s might a person without eyesight identify the correct function. In a backpack, the zipper pull for the main they’re grabbing without ever looking.

“Design is a process, and I’m grateful I learned that

early in my career.”

Do you have any advice for UW design students?

Find the time and make the effort to do extra stuff outside of the curriculum and the classwork that you’re already doing. Enter design competitions—it’s extremely helpful if you can get some honors and put that on your resume. Go to portfolio reviews. Be part of the local design community, that’s how you meet people and learn more about the professional design scene outside of school. This can lead to interviews and internships. It always helps if you meet someone in person—as opposed to emailing a stranger, that’s just a shot in the dark. Get an internship while you’re still in school. I had a really great internship in the summer between my junior and senior year—I worked at Built Design in Everett. We designed snowboard bindings for local outdoor companies like K2 and Ride. It was really cool to be a part of that process, and at the end, I had good projects that I could add to my portfolio. The more you know about the other disciplines and everything involved in a product, the better you’ll be equipped to design in the future.