Looking O

_ó=p~ê~=qÜçãI mea

illhfkd=lrqW=^`olpp=qeb=^qi^kqf`

e waters of the Atlantic stretch hundreds of miles from the nearest landmass in North America to Bermuda’s limestone shores. In the case of Canada, there are around 800 miles from the world’s second largest country to Bermuda, one of the world’s smallest, measuring only twenty-one square miles. People have long crossed this distance, creating both a tangible and intangible heritage, an example of which is the history of Canadian artists in Bermuda. For almost two hundred years, Canadian artists have looked out from their local context, their eyes drawn to the alluring beauty and fascinating culture and history of Bermuda. Yet, while scholarship has considered the relationship between Canadian artists and the Caribbean, another popular destination with Canadian travellers and artists, no comprehensive study or exhibition has been dedicated to the history of these artists and their time in Bermuda 1 Why did they travel, how did they arrive, and what was their artistic response to such a novel and unique context, both within easy reach of their home and yet geographically and aesthetically a world away?

e distance between Bermuda and Canada belies a long history of shared economic, social, colonial and cultural interests. From its early history, Bermuda was a transport hub between Canada and further points in the Caribbean, facilitating constant ows of people and important resources such as salt and sh. Following American Independence, Bermuda and Halifax were both garrisoned and provisioned with new dockyards by the British Royal Navy to service economic and military operations in the Atlantic. During this era, many of the earliest signi cant depictions of Bermuda were created by individuals either serving in or associated with the Royal Navy.2 e rst known works of art depicting Bermuda by a Canadian were created in the 1850s by James Colquhoun Cogswell, of Halifax. It is un known why he travelled to Bermuda, but his watercolour views of the island largely feature Hamilton, a once-sleepy harbour and now Bermuda’s capital, which boomed in the nineteenth century in response to the shift of the island’s naval activities west. Bermuda and Canada’s naval connection persisted into the twentieth century with the Canadian Forces Station Bermuda at Daniel’s Head, where Canadian landscapist and war artist C. Anthony Law rst experienced the island in the 1960s before his return to paint in the 1990s.3

Most Canadians came to Bermuda after the advent of modern tourist amenities on the island, a transformation which began in the late nineteenth century and continued throughout

the twentieth century; and it was a traveller by way of Canada who helped to set this transformation in motion. Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyle, sixth child of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, served as Viceregal Consort of Canada between 1878 and 1884. Al though she dutifully performed her role, Louise had “quite literally never warmed to Ottawa” and sought out warmer winter destinations during her nal years in Canada.4 She spent the winter of 1883 in Bermuda, travelling on HMS Dido from Charleston, South Carolina. A talented artist, Louise made watercolour paintings of the island which capture its lush, emerald foliage and turquoise water. Coverage of Louise’s visit in publications like e New York Times helped spark interest in Bermuda as a destination among North Americans.5

Many Canadian artists first arrived in Bermuda as tourists during the heyday of Ber mudian tourism in the twentieth century but, like Louise, were inspired by the island’s scenery to create art both during and after their sojourns. While the tourist trade was always proportionally dominated by Americans, a sizeable subsect of twentieth-century travellers were Canadian.6 ey could travel to Bermuda via the Canadian National Steamships’ eet of “Lady Boats,” which operated on the route from 1928 to 1952 (with an interruption during the Second World War). e Lady Boats again linked Canada to destinations in the Caribbean, passing through Bermuda on their voyages. The modern era of travel between Canada and Bermuda has been dominated by the aeroplane, with early ight services provided by Trans-Canada Airlines (now Air Canada). e convenience of modern air travel meant that tourists and artists alike could become repeat travellers, creating longer-lasting relationships with the island and larger bodies of work depicting it.

e logistical links between Canada and Bermuda have naturally in uenced which artists visited and worked on the island. Points of departure were largely in Canada’s Central and Eastern Provinces, meaning that most travellers hailed from these areas. e cost associated with travel also meant that artists who worked in Bermuda were often independently wealthy or at a point in their careers to a ord the trip. e history of Canadian artists in Bermuda will therefore never be comprehensive of the full breadth of Canadian art, al though it does relate to important movements and junctures. Many Canadian artists visited Bermuda during the twentieth century, a period which was crucial for Canada both in the expansion of the country’s aesthetic horizons and in the advent of a truly “national” school of art. By making art outside of Canada, artists both informed and challenged these aspects of Canadian visual culture. e following sections supplement the historical links between Bermuda and Canada by considering which artistic practices and perspectives Canadian artists brought to Bermuda, as well as how their experiences in Bermuda may have changed them. In doing so, we can see not just how Bermuda appeared in works by Canadian artists, but also how it in turn informed their practice and vision and dovetailed with the development of twentieth-century Canadian art.

illhfkd=lrqW=clo=`lilro=^ka=cloj

Canadian artists began to frequent Bermuda in considerable numbers in the early twentieth century, which was also the period when Canadian art experienced a blossoming signi cant in both national and international scope. While the period from 1900 to 1930 was crucial in establishing a national visual iconography in Canada, it was also the time when legions of young Canadian artists left the country to study in international art schools, particularly those in Europe.7 ey returned with an exposure to cutting-edge modern art style such as Post-Impressionism and Expressionism, which helped to define Canada’s own visual lan guage.8 Movements such as the Group of Seven, a collective of Canadian painters who worked and displayed together between 1920 and 1933, were interested in how modern art could help to de ne the Canadian landscape. Other contemporaneous Canadian artists, such as James Wilson Morrice and John Goodwin Lyman, were more fundamentally in vested in the aesthetic possibilities of styles such as Post-Impressionism, and especially its use of colour and light to structure form. us, for Morrice and Lyman as well as many other modern artists, travel outside of Canada to destinations saturated with colour and bathed in light was an important way to nd inspiration and to innovate. Both painters sought out novel colours and forms in foreign locales such as France, North Africa, the Caribbean and, in Lyman’s case, Bermuda. Lyman was among the rst in a long line of twentieth-century Canadian artists whose search for aesthetic inspiration rst brought them to—or sometimes brought them back to the subject of—Bermuda. Artists as diverse as Jack Bush, Isabel McLaughlin and Paterson Ewen have taken a unique view of Bermuda’s particular colours and forms, leaving a history of aesthetic engagement which mirrors not only their own evolving styles but also the changing scope of Canadian artistic expression over the twentieth century.

John Lyman and his wife Corinne rst arrived in Bermuda on October 13, 1913, their visit following closely in the wake of two exhibitions of Lyman’s paintings in Montreal, which were heavily criticised by Canada’s conservative press.9 Needing an escape, Lyman accepted an invitation from his uncle and aunt, James and Anna Morgan, who were the new proprietors of the Bermudian estate, Southlands. Lyman employed his short stint in architectural training by supervising building works at Southlands, which prompted him to become interested in Bermudian vernacular architecture. He was driven to document the island’s period structures and created the rst manuscript exploring Bermuda’s architectural and furniture arts heritage, entitled “ e Old Bermudas.”10 Lyman appreciated what he saw as Bermuda’s organic architecture, comprised of essential forms and arising from a utilitarian response to the island’s unique climate and geography.

Uncertain about his future as an artist, Lyman painted only a small number of works in Bermuda during his visits between 1913 and 1918, but those he did complete, such as St. George’s, Bermuda (Century Plant), 1914 (Fig. 1), show his zeal for Bermuda’s built heritage. In the foreground, a century plant (Agave americana) towers over St. George’s, Bermuda’s oldest permanent settlement. Faced with dense development on the historic waterfront, Lyman concentrated on the shifting geometry of the structures while using a subtle coral colour, common to many of his Bermuda paintings and inspired by the island’s light, to transform them into a nearly cohesive block.11 e planar faces of the buildings

cáÖK=N

gçÜå=dççÇïáå=ióã~å NUUSÓNVST

píK=dÉçêÖÉÛëI=_ÉêãìÇ~ E`Éåíìêó=mä~åíFI=NVNQ

láä=çå=Å~åî~ë= ON=ñ=ORNLQ áåK dáÑí=çÑ=íÜÉ= _ÉêãìÇ~=^êíïçêâë= cçìåÇ~íáçåI=NVVT

cáÖK=O

gçÜå=dççÇïáå=ióã~å NUUSÓNVST _ÉêãìÇ~=i~åÇëÅ~éÉI NVRU

láä=çå=Å~åî~ë

NS=ñ=OQ=áåK lå=äç~å=Ñêçã= qçã=_ìííÉêÑáÉäÇI=NVVQ

are mirrored in the formal treatment of the environment, with large expanses of harbour, sea and sky depicted as mostly uninterrupted blocks of colour, save for two spindly black sailing ships. In this painting, it is clear how Bermuda’s unique architecture and environmental conditions encouraged Lyman to further re ne his visual and formal language, even in the face of doubt over his continued future as an artist.12

Feeling artistically reinvigorated by his visits to Bermuda and the end of the First World War, in 1918 Lyman embarked on a long period of painting in Europe and North Africa, where the blocky, light-rendered forms of his Bermuda paintings persisted as a notable aes thetic motif, and particularly in his North African paintings. 13 Lyman resettled in Ca nada only in 1931, almost twenty years after his rejection by the Canadian press and his rst visit to Bermuda. Lyman saw Canada’s art climate as too sentimental and inwardly focused, and set to work reawakening the country’s interest in the fundamentals of form, line and colour through teaching and advocacy.14 In 1939 he founded the Contemporary Arts Society, which promoted the principles of formalism and aesthetic cosmopolitanism and led to the birth of Montreal-based abstract art movements such as Les Automatistes.15 Lyman retired in 1957, taking advantage of his free time to travel again. He visited Bermuda in winter 1957/58, producing deeply beautiful views of the island such as Bermuda Landscape, 1958 (Fig. 2). In this painting, a solitary gure is depicted gazing in contemplation across the water. While the accord between the coral colour of the architecture and the gure’s out t shows Lyman continuing to appreciate the island’s unique colours and forms, it is also easy to imagine him re ecting on his own history of visual and personal experience in Bermuda during what was his last visit. By looking out from the Canadian national context and escaping his critics in the 1910s, Lyman was able not only to revolutionise his own aesthetic practice but also to set in motion the range of visual and personal experience which would help him direct the path of Canadian art upon his return to the country. In the 1930s, Lyman helped to galvanise many artists who felt marginalised by Canadian art’s emphasis on the national landscape. By the time of Lyman’s return to Canada in 1931, André Biéler had spent almost a decade depicting Quebec’s rural communities through a modernist lens. Prior to this, Biéler honed his artistic approach in several locations, including Florida, New York, Switzerland and, for an important period, Bermuda. Biéler was born in Switzerland but moved to Montreal with his family in 1908. He enlisted in the Canadian Army and served in Europe during the First World War, where his unit was gassed in 1917. After his return to Canada, Biéler found it necessary to seek warmer climates for recovery, and in 1919 he travelled with his mother to Florida. Blanche Biéler encouraged her son’s love of art and, after studying under Harry Davis Fluhart at Stetson University in Deland, he enrolled in the Art Students’ League Summer School in Woodstock, New York, where he met George Bellows, studied under Charles Rosen and Eugene Speicher and was im mersed in a milieu which promoted modernist artistic theories and techniques. 16 Im portantly, Roger Fry’s Vision and Design , which championed modernism and Paul Cé zanne’s importance to contemporary painting, was published in 1920 and caused a sensation among Woodstock’s instructors and students alike.17

Ill health again drove Biéler to search for a warmer winter climate. He chose Bermuda, where he lived and painted from February to April 1921. In Bermuda, Biéler put into

practice the techniques and theories he had learned at Woodstock. Hamilton, 1921 (Fig. 3 ) is one of Biéler’s most successful e orts to mirror Woodstock’s “Cézanne-oriented teaching” by emulating the eminent artist’s use of taches, or at, unblended touches of paint. In this outlook from Red Hole in Paget to Hamilton, Biéler formally explored Bermuda’s variegated shoreside environment, where sand, grass and water meet.18 e bent cedars and colours of the land have some of the appearance of Cézanne’s paintings of the Provençal countryside, while the watery pastel shading of the buildings and sky are distinctly reminiscent of Bermuda, and particularly a Bermudian sunrise. Front Street, 1921 (Fig. 4 ) is another view of Hamilton, in which Biéler again employed the tache technique for the sky, boats and buildings, but also used bright, contrasting drops of colour, in the style of Pointillism, for the water. During his stay in Bermuda, Biéler painted alongside Daniel Putnam Brinley, an American artist who helped organise the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art (commonly known as the Armory Show). His companionship and support undoubtedly made the island an even more enriching environment for the young artist’s development, and it is arguable that the great number of modern artists who visited Bermuda in the early twentieth century made it an arts colony to compare to Woodstock and even Provincetown in terms of opportunities for artists to gather and share theories or techniques.19 A further episode of ill health impacted Biéler and forced his departure from Bermuda, but he would

cáÖK=P ^åÇê¨=_á¨äÉê NUVSÓNVUV e~ãáäíçåI=NVON láä=çå=Å~åî~ëI= ãçìåíÉÇ=çå=Äç~êÇ= NRNLO=ñ=NVNLQ=áåK lå=äç~å=Ñêçã=íÜÉ= _ÉêãìÇá~å~=cçìåÇ~íáçå çÑ=`~å~Ç~I=OMMQ

cáÖK=Q

^åÇê¨=_á¨äÉê

NUVSÓNVUV

cêçåí=píêÉÉíI=NVON

láä=çå=Å~åî~ë

NRNLO=ñ=NVNLQ=áåK

mìêÅÜ~ëÉI=áå=ãÉãçêó=çÑ

páê=a~îáÇ=dáÄÄçåëI=OMMO

cáÖK=R

`Ü~êäÉë=cê~ëÉê=`çãÑçêí

NVMMÓVQ

qÜáêÇ=eçäÉI=jáÇ=lÅÉ~å

`äìÄI=NVTU

láä=çå=Å~åî~ë

NVNLQ=ñ=ORNLO=áåK

lå=äç~å=Ñêçã=íÜÉ= _ÉêãìÇá~å~=cçìåÇ~íáçå

çÑ=`~å~Ç~I=OMMO

illhfkd=lrqW=`~å~Çá~å=^êíáëíë=áå=_ÉêãìÇ~

continue to employ the formal skills he honed on the island throughout his career, com bining them with Canadian subject matter from 1926 onwards in his distinctive blend of modernist regionalism.

For Biéler, formal exploration prefaced his later emphasis on local scenes and culture, but for other artists this evolution travelled in the opposite direction. is is certainly the case for Jack Bush, one of Canada’s foremost abstract artists. Bush studied under Charles Fraser Comfort, a Toronto painter and muralist who also worked in Bermuda in the 1970s. Comfort’s use of bold and sharply de ned forms and colours—as seen in his moody, high contrast paintings of Bermuda’s South Shore ( ird Hole, Mid Ocean Club, 1978, Fig. 5)— was an important in uence on the development of Bush’s painting, but it was his contact with American abstraction which would de nitively tip him into the most celebrated period of his career. Following his marriage to Mabel Teakle on September 3, 1934, Bush spent his honeymoon in Bermuda, during which he made an artistic excursion to Bermuda’s East End and painted at least three small watercolour scenes: Fort St. Catherine, Bermuda, 1934, Old Maid’s Lane, 1934, and St. George’s, Bermuda, 1934 (Fig. 6 ).20 ese studies of everyday Bermudian life and scenery are distinctly direct and realistic, from the aged walls of historic St. George’s to the sun-dappled rocks of Gates Bay.

Bush returned to the subject of Bermuda in 1939, creating two larger and more formally

cáÖK=S g~Åâ=_ìëÜ NVMVÓTT píK=dÉçêÖÉÛëI=_ÉêãìÇ~I NVPQ

t~íÉêÅçäçìê=çå=é~éÉê= TNLQ=ñ=UNLO=áåK

dáÑí=çÑ=pçãÉêë= oÉ~äíóI=NVUU

cáÖK=T

g~Åâ=_ìëÜ

NVMVÓTT

eçìëÉ=~åÇ=cáÖìêÉI= píK=dÉçêÖÉÛëI=NVPV

t~íÉêÅçäçìê=çå=é~éÉê NUNLO=ñ=OQ=áåK

mìêÅÜ~ëÉ=ã~ÇÉ= éçëëáÄäÉ=Äó=íÜÉ=içåÇçå j~ê~íÜçåI=NVUV

experimental compositions.21 Painted in his Toronto home studio, House and Figure, St. George’s, 1939 (Fig. 7 ) is an evident revisiting of the 1934 watercolour, St. George’s, Bermuda. In this version, Bush simplified and flattened his earlier view of a typical Bermudian dwell ing. e wooden door has been replaced by a grey rectangular form which echoes across the façade, while Bush created another repeating pattern by extending the stonework of the wall. e house’s newly sharp angles are complimented by clear, contrasting colours, such as the deep cobalt of the sky. Most glaringly, Bush swapped the man and small child in the 1934 watercolour for two gures, whose stark colouration, stacked positioning and odd, angular poses delineate them as a product of Bush’s studio. While it is unknown whether Bush saw a woman bearing oranges in person—this being a common practice in the early twentieth century—saw images (a noted autochrome photograph by Karl Struss shows a woman carrying fruit in such a way), or worked from his imagination, the inclusion of the gure is hinged around the formal e ects of such a swap compared to the 1934 painting.22

In House and Figure, we see some of the earliest hints of Bush’s immense skill in colour and abstraction. e precocity of Bush’s early watercolours has, in hindsight, been recognised by art historians, who note in them the “characteristic con gurations, ways of juxtaposing colours, typical ‘Bush’ shapes” which populate his later paintings.23 In watercolour, Bush found the freest expression of his compulsion to essential colour and form; and it is not coincidental that watercolour is also the medium Clement Greenberg advised him to base

his oil paintings on in further re ning and attening his forms during their rst meeting in 1957.24 In reworking his more naturalistic 1934 painting of Bermuda, Bush’s focus was on creating an appealing play between colour and form, with Bermuda as his test subject. Bush spent only a short period in Bermuda but left behind an intriguing record of artistic inspiration. Other artists, such as Isabel McLaughlin, have a longer history of engagement. McLaughlin was a key artist in Toronto’s modern art community and the first female president of the Canadian Group of Painters, an o shoot of the Group of Seven founded in 1933. She began travelling to Bermuda in the 1930s and continued to visit into the 1960s, staying at Cedar Lodge, her family’s substantial property which was purchased by her motor tycoon father R. S. McLaughlin in 1936. McLaughlin was chie y interested in nature and had a keen eye for pattern and design informed by both her own distinctive style and by popular compositional theories such as Dynamic Symmetry, which she studied under Emil Bisttram.25 In Harbour Road, c. 1950s (Fig. 8 ), a large work on paper which depicts a view from Harbour Road onto islands in the Great Sound, a large tree gures prominently in the composition, but it is the scale of the leaves—dropped from the Monstera deliciosa plant, a stalwart of Bermudian roadsides—which is most daring. ey dominate not only the faintly sketched gures but also the houses and the road itself. In addition, the hills appear more Canadian in scale than Bermudian. Despite these jarring breaks, the composition is still balanced and the forms easily ow between one another, for instance from the lines of the Bermuda roof to the ripples in the water. McLaughlin’s unique perspective on both art and Bermuda, developed over many trips to the island, could at once completely transform

cáÖK=U fë~ÄÉä=jÅi~ìÖÜäáå NVMPÓOMMO e~êÄçìê=oç~ÇI=ÅK=NVRMë t~íÉêÅçäçìê=~åÇ= Öê~éÜáíÉ=çå=é~éÉê OM=ñ=OS=áåK dáÑí=çÑ=a~îáÇ= ^ìê~åÇíI=OMMU

cáÖK=V

fë~ÄÉä=jÅi~ìÖÜäáå NVMPÓOMMO

q~ìí=p~áäëI=NVSN

láä=çå=Å~åî~ë

OU=ñ=PS=áåK

lå=äç~å=Ñêçã=íÜÉ= _ÉêãìÇá~å~=cçìåÇ~íáçå çÑ=`~å~Ç~I=OMMM

a local scene while also bringing into focus the forms which de ne the island’s landscape. McLaughlin’s visits to Bermuda branch an important stylistic shift in art. By the 1940s, abstraction was again becoming an important force, upending the focus on the national landscape and on regional scenes in both Canada and the United States. McLaughlin also experimented with abstraction, encouraged to do so by Alexandra Luke, her relative via marriage and a member of one of Canada’s most important abstract art movements, the Painters Eleven. She created several highly abstract works, including one based on Bermuda subject matter. Taut Sails, 1961 (Fig. 9 ) is a depiction of a traditional Bermuda regatta. McLaughlin transformed the breglass-hulled Sun sh boats, popular in the 1960s and ’70s, into stacked, triangular shapes oating on a highly abstracted water pattern, with the ripples like the boats depicted as repeating geometric forms. A more naturalistic view of a Sun sh regatta, entitled Bermuda Sails, 1961, was apparently a favourite of McLaughlin’s father, who featured an image of it on his 1961 Christmas card.26 McLaughlin’s easy transition between abstracted and representational views of the same subject shows her versatility as an artist, as well as how Bermudian imagery inspired her in an evolving and multifaceted manner. Abstraction continued to in uence the tenor of Canadian art in the 1960s and ’70s, al though at the same time new and established artists alike were also beginning to em brace lm, installation and conceptual art practices. Often, these explorations in new media allowed artists to take a novel view of traditional subjects, as was the case for Paterson Ewen’s mixed media and gouged plywood “canvases,” which he began creating in the 1970s. ese works were landscapes in the most untraditional sense, exploring nature through its phenomena or looking beyond the earth at the cosmos. While Ewen is known

for his large-scale, mixed media or plywood works, he also continued to make works on paper throughout his career, including a lesser-known body of works on paper made in Bermuda in the 1990s.

Ewen began visiting Bermuda with his wife, Mary Handford, in the 1980s. ey largely stayed at Coral Beach and Tennis Club, a storied centre of Bermuda tourism located on the South Shore.27 Ewen brought materials on their visits, including watercolour paint and handmade paper. A portion of the works he created during his visits depict the South Shore view from Coral Beach, with glistening sea and sky and, in the case of Whale Sighting, 1999 (Fig. 10 ), a migrating humpback whale. e inclusion of a gure, even as a distant form, is relatively individual in Ewen’s work, showing his unique reaction to Bermuda’s environment and scenery.28 e island’s visual di erence from Canada alone was inspiring to Ewen, who called Bermuda “heavenly with colour”; and his enjoyment of such is evident in the u y, candy-coloured clouds and jewel-toned water of his seascapes.29 Ewen’s use of brilliant colour in his Bermuda works is particularly marked, given that during this period he was restricting the use of colour in his gouged plywood canvases.30 at said, his Bermuda watercolours still conceptually tie to his larger practise, something which becomes apparent when looking at the celestial-themed works he made in Bermuda, for instance Bermuda Moon, 1994 (private collection). While the moon was a common theme in Ewen’s work, it also aligns that he depicted Bermuda’s moon given his interest in environmental systems, of which the moon and the tides form an important one.

cáÖK=NM m~íÉêëçå=bïÉå NVORÓOMMO

tÜ~äÉ=páÖÜíáåÖI=NVVV t~íÉêÅçäçìê=çå=é~éÉê NNPLQ=ñ=NPNLO=áåK dáÑí=çÑ=j~êó=e~åÇÑçêÇI ïáÑÉ=çÑ=íÜÉ=~êíáëíI=OMMQ

cáÖK=NN

`Ü~êäÉë=dê~Ü~ã=bäáçí

NVNOÓQM

qêÉÉJäáåÉÇ=`çîÉI=ÅK=NVPMë

láä=çå=Äç~êÇ

NNPLQ=ñ=NRNLO=áåK

mìêÅÜ~ëÉI=OMMR

Ewen’s translation of Bermuda’s colours introduces a contemporary element to the long history of Canadian artists’ formal investigations of Bermuda’s distinct scenery, taking it from Post-Impressionist painting through to abstraction and nally to conceptual art. rough the discussed artworks, we see not only a variety of distinctly Bermudian colours and forms, but also how these elements have been interpreted by a range of Canadian artists whose practises are completely individual while also typifying aesthetic trends and debates of their time. The next section investigates the connections between people, as well as between people and place, through the emphasis on the national landscape and portraiture in twentieth-century Canadian art, and how this both adhered and transformed in a Ber mudian context.

illhfkd=lrqW=lk=mblmib=^ka=mi^`b e landscape gures prominently in Canadian art, and this stature has meant its depiction in a plethora of forms. e interpretation of landscape presented by artists such as Lyman, McLaughlin and Ewen, who usually focused primarily on colours, forms and light, can be contrasted to one which has loomed largest in the national imagination, namely the de piction of the Canadian landscape pioneered by Tom omson and the Group of Seven in the period between 1910 and 1933. eir paintings married a Post-Impressionist aesthetic with a focus on what they believed de ned not just Canadian art but Canadians as a whole: speci cally, the “wilderness” landscape of Canada’s North Country.31 In this way, the Group of Seven’s paintings are arguably as much about the national vision of Canada—its ideals,

culture and politics—as the landscape itself, and set a precedent in Canadian art for both nationally-minded landscape painting and for probing explorations of the connection between Canada’s people and its places.32 Naturally, this approach was largely focused on Canada itself, although many Canadian artists also created art abroad, taking their interest in place and identity, via both landscape and portraiture, with them. In considering almost a century of art made by Canadian artists in Bermuda, we can see how this aspect of Canadian cultural and artistic history translated to Bermuda, a foreign and unique context.

Members of the Group of Seven helped set the tone as early as the 1910s for symbolically and nationally signi cant landscapes. Given this purview, it follows that they focused on Canada during the period from 1920 to 1933, when the Group was active. J. E. H. MacDonald, a founding member of the Group of Seven, was one of the few noted as venturing far from Canada’s borders to paint. Recovering from a stroke and in need of rest and warmer weather, he took the RMS Lady Drake in January 1932 in the direction of Barbados, stopping brie y in Bermuda. Sketchbooks from his journey document his impressions of the island, which he likened to Canada in several ways: the colour of the sea, for instance, was a “Lake Ontario blue,” and he compared a large rubber tree to plants in a Toronto sunroom.33 MacDonald made a small sketch of Bermuda in pencil from the ship, which depicted its low, densely vegetated hills, and re ected in his notes that “Bermuda from the sea frequently resembles the shores of Lake Superior or Labrador.”34 Unlike his paintings of Barbados, where he depicted the palm trees, coastal views and island dwellings which distinguish the tropical island from Canada, MacDonald was more taken with Bermuda’s similarities to Canada than its di erences. MacDonald’s impressions of Bermuda were not transformed into paint before his death in November 1932, an especially unfortunate turn given the artist’s immediate aesthetic and personal identi cation with the island.

MacDonald’s death in 1932 heralded the end of the Group of Seven, after which its members began to travel and take in more subjects outside of Canada. Associates of the Group of Seven, who exhibited with them prior to the disbandment of the collective, began to visit Bermuda during the 1930s, giving insight into how the aesthetic of the movement could cohere to the Bermudian context. In 1931, at the age of 19, Charles Graham Eliot displayed a Canadian landscape in the nal Group of Seven exhibition, which was held at the Art Gallery of Toronto.35 Tree-lined Cove, c. 1930s (Fig. 11.), one of several small oil sketches from Eliot’s trip to Bermuda, perhaps best depicts what MacDonald saw of Canada in the island, with its calm body of water lled with rocks and surrounded by nature. MacDonald largely saw Bermuda from the water which, much like the Canadian wilderness, stretches for endless miles and often represents an uninterrupted vista. Yet, exploring and painting in Bermuda also means being faced with the sheer density of the landscape, something Eliot responded to in his paintings. Most notably, Railway Bridge, c. 1930s (Fig. 12 ) uses the impasto painting technique and rhythmic forms typical of Toronto painters in the 1920s and ’30s to depict the sturdy structure of the Bermuda Railway crossing at Flatts Village. is view, which contains transport, ora and domestic dwellings all at once, shows how nature and human development exist in close quarters in Bermuda, distinguishing it from the archetypal Canadian wilderness landscape and necessitating that artists painting in the style of the Group of Seven take a di erent approach to their subjects.

cáÖK=NO

`Ü~êäÉë=dê~Ü~ã=bäáçí

NVNOÓQM

o~áäï~ó=_êáÇÖÉI=ÅK=NVPMë

láä=çå=Äç~êÇ

NNPLQ=ñ=NRNLO=áåK

mìêÅÜ~ëÉI=OMMR

cáÖK=NP

vîçååÉ=jÅh~ÖìÉ eçìëëÉê

NUVTÓNVVS

máåâ=`çíí~ÖÉI=NVPT

láä=çå=Äç~êÇ

NO=ñ=NT=áåK

mìêÅÜ~ëÉI=OMMR

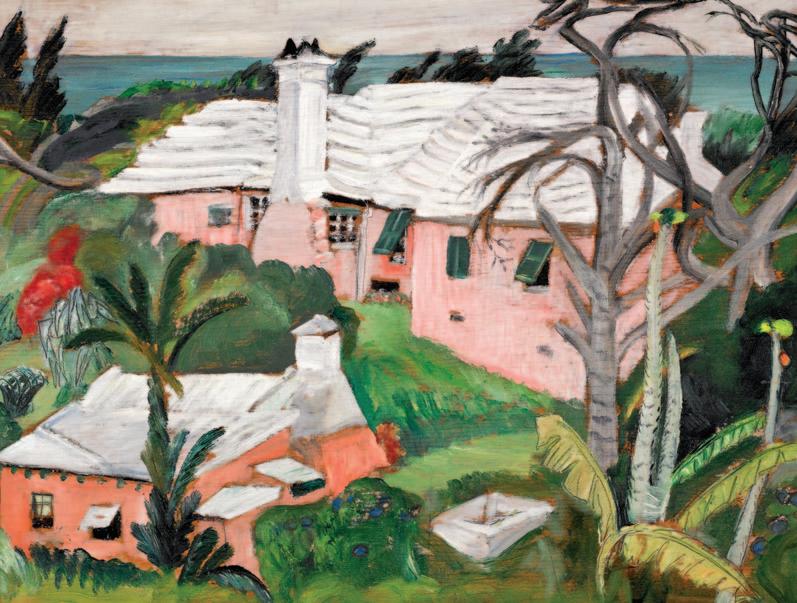

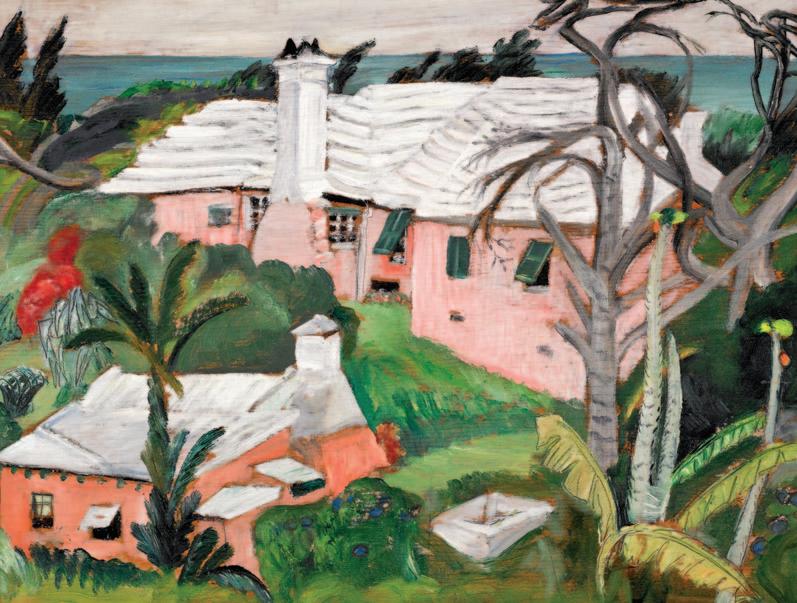

In 1937 Yvonne McKague Housser, another key artist associated with the Group of Seven, visited Bermuda, arriving shortly after the death of her husband, Group of Seven historian Frederick Boughton Housser. She stayed at Cedar Lodge with fellow artists McLaughlin—who was a long-time friend since their meeting at the Ontario College of Art in 1925—Prudence Heward and Audrey Taylor. McKague Housser painted a notable view of the guest house at Cedar Lodge (Bermuda, 1937, e Robert McLaughlin Gallery), in which drying clothes and towels draped over garden furniture suggest the atmosphere of camaraderie and ease among the artists, and a dense canopy of endemic Bermuda cedar trees encloses and shields the bucolic setting. Her interest in the intersections between nature and the built environment, most associated with paintings such as Cobalt, 1931 (National Gallery of Canada), which depicts a then-failing mining town set in Northern Ontario, further extended to other Bermudian sites. Pink Cottage, 1937 (Fig. 13) shows two dwellings in a lush, seaside setting. e use of dynamic lines and billowy forms creates a sense of movement which is not isolated to the dense foliage—even the houses seem to sway with the high Atlantic wind. e open shutters on the two structures also give a sense of movement and life, indicating that there are inhabitants behind the stone facades. As with her view of the guest house at Cedar Lodge, McKague Housser often included signs of life in her paintings, showing her latent fascination with the people who occupied the places she painted. She explored this fascination in more depth in Bermuda, where she painted House, Bermuda, 1937, which included a Black Bermudian family in front of their home. 36 McKague Housser’s work from 1936 onwards increasingly included figures, in cluding sketches and paintings made in Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago in the 1940s and ’50s, where she often concentrated on the local population. e Group of Seven painted largely unpeopled landscapes, a choice linked in recent scholarship to the terra nullius rhetoric of colonialist expansion, which framed the land as virgin territory despite existing First Nations settlements.37 us, painting people could be both politically and artistically transgressive in Canadian art during the early twentieth century—although, when the subjects were marginalised persons or people of colour, equally imbued with issues of race and class. Opposed to but also in conversation with their Toronto counterparts, the artistic community of Montreal often concentrated on images of everyday life, for instance André Biéler’s form of modernist regionalism, which highlighted the province’s rural communities. Many of the key Montreal artists of the 1920s, such as Edwin Holgate, Adrien Hébert, Mabel May, Lilias Torrance Newton and Prudence Heward, were members of e Beaver Hall Group (1920–22), a short-lived but in uential modernist collective which is renowned both for its inclusion of female artists and for fostering an interest in the human subject, especially portraiture. 38 While the resultant portraits were sometimes of intimates or other gures in the Montreal community, they also took a more symbolic form, associated with the larger strand of regionalism running through art of the period, in which individuals became representative of communities or were associated with a place.

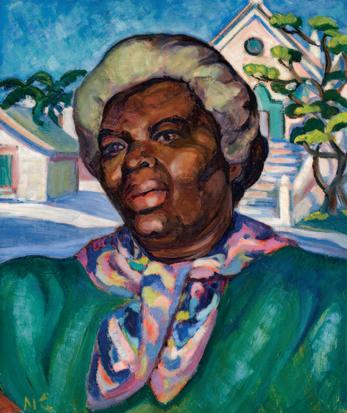

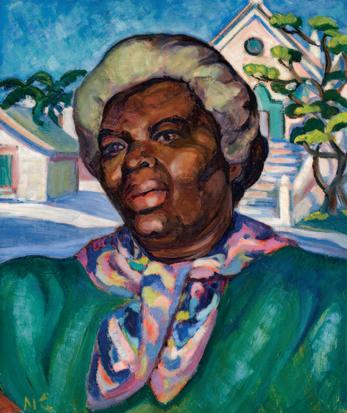

Prudence Heward, an Anglo-Montreal artist who was a member of e Beaver Hall Group and best known for her portraits of women, also travelled to Bermuda with McLaughlin, McKague Housser and Audrey Taylor. She produced two portraits in response

cáÖK=NQ

kçê~=cK=bK=`çääóÉê NUVUÓNVTV

píK=mÉíÉêÛë=`ÜìêÅÜI=píK

dÉçêÖÉÛëI=_ÉêãìÇ~I=NVOV

láä=çå=Äç~êÇ

VNLQ=ñ=NP=áåK

lå=äç~å=Ñêçã=íÜÉ=

_ÉêãìÇá~å~=cçìåÇ~íáçå çÑ=`~å~Ç~I=OMNO

to her trip which, while thoughtful and formally sophisticated, also encapsulate issues of class and race at play not just in Heward’s relationship to Bermuda but also that of other visiting artists during this period. Hester, 1937 (Agnes Etherington Art Centre), a portrait of a nude woman in a verdant, exotic landscape, was modelled on sketches of local models Heward made in Bermuda, if not painted during her trip to the island.39 Art historians have commented on Heward’s portraits of models of colour, highlighting the ambivalence between Heward’s nuanced take on the subject and the unbalanced power dynamic between a white artist and a model of colour, as well as the problematic gaze of a primarily white audience on the nude form of the model, especially when placed in a “tropical” setting.40 e racial implications of McKague Housser’s West Indian and Bermuda paintings have also been noted, showing the complexities at play in creating these cross-cultural depictions of people and place at the time and in reading these works today.41

Heward and other Canadian artists often used their trips to Bermuda and other destinations to make sketches that informed paintings on their return to Canada, which is ironically true of the more outwardly Bermudian of Heward’s two Bermuda portraits, Clytie, 1938 ( e Robert McLaughlin Gallery), which depicts a well-dressed girl in a Bermuda setting identi able by the white-roofed house and stone wall draped with a blossoming morning glory vine.42 Nora F. E. Collyer, another artist associated with e Beaver Hall Group, also used paintings created in Bermuda to inform a portrait, although with a more signi cant delay. Collyer visited Bermuda in 1929 with fellow Beaver Hall artist Sarah Robertson. While on the island, her attention was manifestly drawn to St. Peter’s Church, the oldest Anglican church in continual use in the Americas, which she painted as a small oil sketch

(St. Peter’s Church, St. George’s, Bermuda, 1929, Fig. 14 ). Twenty- one years later, in 19 50, Collyer submitted a quarter-length portrait of a woman in front of St. Peter’s Church, entitled Alberta, c . 1949–50 (Fig. 15 ), to the Group Show of Women Painters at the Montreal Museum of Fine Art.43 e view of the church mirrors the 1929 painting but with small changes, such as the re moval of the clocktower to create a better compositional balance between the gure and the background. There is an overt identification be tween the sitter and the setting, not just in her dress—the formality of which indicates church attendance—but also in her expression, which makes her appear absorbed by otherworldly matters. Why Collyer, better known for her landscapes, completed this portrait with such a delay between initial inspiration and nal conception is unknown, but it is possible that the prospect of exhibiting in a group show of female artists made her want to explore a female subject.

Other Canadian artists, such as Dorothy Austin Stevens, preferred to work with local models and to nish their works on site, which gave them the unique opportunity to engage more directly with the island and its residents. Stevens visited Bermuda in 1946, completing three portraits of children and numerous city views, for instance Street Scene, Bermuda,

cáÖK=NR kçê~=cK=bK=`çääóÉê NUVUÓNVTV ^äÄÉêí~I=ÅK=NVQVÓRM láä=çå=Å~åî~ë=Äç~êÇ OQ=ñ=OM=áåK lå=äç~å=Ñêçã= ~=éêáî~íÉ=ÅçääÉÅíáçå

cáÖK=NS açêçíÜó=^ìëíáå=píÉîÉåë NUUUÓNVSS píêÉÉí=pÅÉåÉI=_ÉêãìÇ~I NVQS láä=çå=Äç~êÇ NU=ñ=OQ=áåK lå=äç~å=Ñêçã=íÜÉ= _ÉêãìÇá~å~=cçìåÇ~íáçå çÑ=`~å~Ç~I=OMMP

cáÖK=NT

gçÜå=eçääáë=h~ìÑã~åå NVPTÓ

içï=qáÇÉI=OMMP

^ÅêóäáÅ=çå=Å~åî~ë

OQ=ñ=PM=áåK

dáÑí=çÑ=íÜÉ=^êíáëí=

C=Üáë=ïáÑÉ=oçñóI=OMMU

1946 ( Fig. 16 ), which also featured children at play. She created enough artwork in Ber muda to merit an exhibition at a local department store, A. S. Cooper & Sons, in its art shop and gallery. e show was reviewed in e Royal Gazette by “Humbert”—Gabrielle Humbert, a German artist and resident of Bermuda who also painted portraits and local scenes.44 Humbert celebrated Stevens’ exhibition as an inspiration to residents and artists alike, and it is possible that it led to her own exhibition in A. S. Cooper’s the following month.45 Stevens’ earlier paintings inspired by travel abroad, such as Coloured Nude, 1930, have been critiqued by art historians as reductive and exoticising.46 Her Bermuda works are more realistic and, while consistent with an outsider’s view of place, consider locations and local subjects beyond the scope of many visiting artists. Following the repatriation of Street Scene, Bermuda, a search by Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art for the children in the image revealed them as Carlton and Milicent Wilkinson, and the fact that Mr. Wilkinson still remembered the day Stevens asked the brother and sister to pose for her painting.47 Whatever Stevens’ intentions for her paintings, they took on new and enriched meaning when presented to the local population of Bermuda both at the time of their creation and almost sixty years later.

One of the most important Canadian artists in terms of local impact is sculptor Evelyn Fay “Byllee” Lang (1908–66). Lang was born in Didsbury, Alberta. She studied at the Winnipeg School of Art and lived in Europe before mounting tensions brought her back to Canada in 1936. Like Stevens, Lang also travelled to Bermuda in the mid-1940s but, instead of returning to Canada, she decided to make the island her home for the next

cáÖK=NU

gçëÉéÜ=jçåâ NVMUÓVM _êÉ~âÉêëI=_ÉêãìÇ~I= ÅK=NVRV

láä=çå=Å~åî~ë

NNNLQ=ñ=NRNLO=áåK dáÑí=çÑ=aÉÄçê~Ü= _ìííÉêÑáÉäÇI=OMMO

cáÖK=NV

gçå=p~ë~âá NVTPÓ jáÇJjçêåáåÖ=~í=íÜÉ açÅâó~êÇI=NVVS

láä=çå=Äç~êÇ

SNLO=ñ=UPLQ=áåK mìêÅÜ~ëÉI=NVVS

twenty years. She also found her footing at A. S. Cooper’s, where she was granted a small studio space by brothers Sir Gilbert and Arthur Cooper and worked in the window dressing department. She opened her own studio, which quickly became a “gathering place for artists of the day.”48 Lang had already founded an art school in Winnipeg, and so naturally became an educator and mentor for Bermudian artists, including Vivienne Gardner, Carlos Dowling, Elizabeth Ann Trott and Emma Ingham Donouk. Signi cantly, she ignored the colour bar laws which enforced segregation across Bermudian society by teaching mixed-race art classes. Her most important commission was the reredos, or altar screen, for Bermuda’s Anglican Cathedral in Hamilton, which would occupy her for the last decade of her life. Her expertise as a sculptor is shown in the delicate modelling of the faces of Christ and saints, for which she controversially used local models.49 She also created more playful works, such as a dancing pig with an amusingly human face in the collection of the National Museum of Bermuda (Pig Statuette, c. 1960).

With the expansion of Bermuda’s artistic community and its art associations in the mid-twentieth century—a development encapsulated by the o cial establishment of the Bermuda Society of Arts in 1956—artists from Canada and the US alike found new op portunities to meet and interact with Bermudian artists. As well as her work on the reredros, Lang exhibited at the BSoA alongside leading local artists such as Charles Lloyd Tucker, who was a pallbearer at her funeral.50 She also worked alongside another important gure of Bermuda’s artistic community, John Hollis Kaufmann, to design dance costumes for Bermuda Musical and Dramatic Society productions.51 Kaufmann is also Canadian, although he moved to Bermuda as an adolescent. He returned to Canada to study with the likes of Arthur Lismer, John Lyman and Richard Jack, before beginning to paint and exhibit in Bermuda in the 1950s.52 Kaufmann’s seascapes, such as Low Tide, 2003 (Fig. 17 ), are characterised by their subtle variations of blues and pinks and represent an ever-shifting view of Bermuda’s most constant companion, the sea. Kaufmann’s career-long interest in portraying Bermuda’s waters was in part inspired by fellow Canadian artist Joseph Monk, whose paintings Kaufmann saw exhibited while only a teenager and who he befriended during the older artist’s time in Bermuda.53 Monk visited the island often in the late 1950s and early 1960s, painting moody seascapes such as Breakers, Bermuda, c. 1959 (Fig. 18 ) and exhibiting them with the BSoA.54 e high point of Bermuda’s tourism industry followed the close of the Second World War and led to an explosion of visitors to the island, among whom gured many Canadians.55 e ease of modern air transport as well as the plethora of hotels and amenities also meant many artists became repeat visitors, whose frequent contact with Bermuda led to large bodies of work which demonstrate a familiarity and appreciation for the island and its residents. For instance, Canadian portraitist Bernard Aimé Poulin visited Bermuda frequently from the 1960s, and the island has become a key subject in his work. As well as portraits of important Bermudian gures such as Premier Dame Jennifer Smith and Dame Lois Browne-Evans, Poulin has made hundreds of paintings of Bermuda’s cultural particularity, for instance the island’s history of sailing as well as its natural beauty. His familiarity with the island has also led him to capture unique landscape scenes such as e Natural Arches, Bermuda , 2003 (Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art), which shows the treasured

land mark only days before it was destroyed by Hurricane Fabian in September that year. omas (Tom) Roberts and Edward B. (Ted) Pulford frequented Bermuda in the second half of the twentieth century, creating nuanced and varied images of the island in a realistic style characteristic of Canadian landscape painting in the late twentieth century—for instance, the “Maritime Realism” of Mount Allison University, where Pulford taught scores of artists such as Mary Pratt and future Bermuda visitor Roger Savage. Jon Sasaki, another graduate of Mount Allison, also travelled to Bermuda in 1996. Fresh o his university studies and inspired by the works of the Group of Seven and their response to the local landscape, his Bermuda paintings were made at various sites on the island, such as Hamilton and Dockyard. While painting Mid-Morning at the Dockyard , 1996 ( Fig. 19 ), Sasaki en countered the founder of Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art, Tom Butter eld, another Canadian-trained artist who acquired three of his paintings—the rst signi cant sale for the burgeoning artist of his work.56 Sasaki has enjoyed a celebrated career notable for his work in multiple fields, but especially for site-specific installations which, like landscape painting, consider the relationship between viewer and place. He re ects fondly on his experience painting in Bermuda and considers these works as part of his trajectory. 57 Works by Poulin and Sasaki bring the Bermudian history of Canadian land scape painting and portraiture during the twentieth century full circle, showing the continued importance of place and identity to Canadian art but also the new means of capturing and analysing these topics, many of which purposely exceed the nationalist focus of the early twentieth century and explore new points of contact fostered by travel, expan sion of institutional frameworks and increased interest in cross-cultural dialogue between Canada and Bermuda and its artists.

illhfkd=clot^oaW=`^k^af^k=^oqfpqp=fk=_bojra^I=OMMMÓmobpbkq

Over the course of the twentieth century, Canadians artists travelled to Bermuda for reasons as unique as each individual, including leisure, health, local connections or professional opportunities. Either on island or back in their studios, they created art which demonstrated the visual and cultural particularities of Bermuda while also reflecting contemporary con cerns and trends in Canadian visual culture. roughout this same period, Bermuda’s own art world developed to o er more venues and opportunities to foster local talent and to draw visiting artists, including institutions of display. In the second half of the twentieth century, an interest in gathering the diverse range of works by artists, both local and inter national, who have depicted Bermuda led to the establishment of local collections, including that of the Masterworks Foundation, founded by Tom Butter eld in 1987. Since 2008, this multifaceted collection has been housed in the island’s first purpose-built mu seum, Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art. Artworks by Canadian artists have been added to this collection via purchase, loan and donation, with the support of the Bermudiana Foundation of Canada of particular note. Today, the museum’s collection of more than one hundred and fty works of art by Canadian artists comprises the largest collection of its kind in Bermuda, spreading knowledge of Canadian visual culture among Bermuda’s resident population and the many visitors of all nationalities who visit the island and the museum.

cáÖK=OM

gçÜå=e~êíã~å

NVRMÓ

sáÉï=Ñêçã=dáÄÄë=eáääI OMMR

láä=çå=Å~åî~ë= SS=ñ=SM=áåK

dáÑí=çÑ=íÜÉ=^êíáëíI=OMMR

cáÖK=ON

mÜáä=_ÉêÖÉêëçå

NVQTÓ

_ÉêãìÇ~=páÖÜíáåÖë=fuI OMMM

mÜçíçÖê~éÜI=`JqóéÉ

NR=ñ=NR=áåK

dáÑí=çÑ=íÜÉ=^êíáëíI=OMMM illhfkd=lrqW=`~å~Çá~å=^êíáëíë=áå=_ÉêãìÇ~

Since 2000, more than one hundred works by Canadian artists have joined Masterworks Museum’s Permanent Collection, including pieces by Canadian contemporary artists who have visited Bermuda in the last twenty years. e result has been the deepening of the Collection through the addition of important historic works and through the diversi cation of media and perspectives typical of twenty- rst century art. Canadian artists of today are nding new ways to work within the realms of landscape and portraiture while re ecting contemporary attitudes and concerns, seen for instance in Bermuda works by John Hartman. Paintings from his 2005 visit to the island, such as View from Gibbs Hill, 2005 (Fig. 20 ), feature aerial views looking out over Bermuda, particularly Ireland Island (the site of Bermuda’s historic Dockyard) and the South Shore. The bold colours and impasto painting technique of Hartman’s works situates them within the larger aesthetics of both Canadian abstraction and landscape painting, while their novel, bird’s-eye viewpoint nuances this heritage and introduces environmentalism as a concern. Hartman’s aerial landscapes bridge the understanding of place between humans and nature by presenting the viewer a unique way to situate themselves in the world and to see the physical systems and relationships which tie it together.

Not content just to collect past works, Masterworks has also directly supported con temporary art and artists in Bermuda, particularly with the establishment of the Mas terworks Artist in Residence Programme in April 1997. Visiting artists from around the world have been housed with studio facilities for three-month periods in Dockyard and St. George’s. Acclaimed Canadian photographer Phil Bergerson participated in the res idency programme in 2000 at Dockyard, which he made his main subject. In the re sultant series, called “Bermuda Sightings,” Bergerson revealed the unseen side of the otherwise busy cultural centre and cruise ship terminal. Acting as both photographer and archaeologist, he excavated an abandoned site, sifting through its remnants and capturing images such as Bermuda Sightings IX, 2000 (Fig. 21 ), which shows how signs of life and culture both decay and persist with neglect or abandonment. Another Canadian artist who elected to work with discarded materials as part of her Masterworks residency is MarieDe nise Douyon. Born in Haiti, Douyon has lived and worked in Canada since 1990. During her 2008 residency, she collected debris washed ashore on Bermuda’s beaches and used it to create sculptures which she called “Afrikeco Art.” A process of assemblage, these sculptures use Bermuda’s material world in a unique way. Douyon also painted a series of portraits of a woman she befriended during her residency, continuing the long tradition of portraiture by Canadian artists in Bermuda but adding an important new dimension of friendship and camaraderie between artist and subject to this history ( e Road of Need, 2008, Fig. 22 ). Other Canadian artists such as Nicole Peña, Adrian Baker and Ted Michener have taken part in Masterworks’ Artists in Residence Programme, and it is the continuing goal of Masterworks to support artists in creating new works of art inspired by Bermuda. e works of Hartman, Bergerson and Douyon are examples of how contemporary Canadian artists are working within the traditions of Canadian art while actively nuancing its history and pushing its boundaries. Added to this history is the tradition of Canadian artists visiting and creating art in Bermuda, a manifestly attractive and convenient desti nation which has welcomed Canadian artists in their most triumphant and turbulent

cáÖK=OO j~êáÉJaÉåáëÉ=açìóçå

NVRTÓ

qÜÉ=oç~Ç=çÑ=kÉÉÇI=OMMU

láä=çå=ã~êáåÉ=éäóïççÇI

OONLO=ñ=OONLO=áåK

dáÑí=çÑ=qçã=_ìííÉêÑáÉäÇI

OMMU

times. For the many Canadian artists who have visited Bermuda, perspective and place were key factors in the creation of their artworks inspired by the island, both in terms of the aesthetic perspectives they brought with them and in the inspiration they gained from a new visual and cultural experience of place. The display of the resultant artworks in Bermuda gives them a second opportunity to act as a bridge between these two distant but often connected countries. Just as Canadian artists have “looked out” on Bermuda, creating aesthetic and personal links bridging a vast ocean, we may also look back to look forward, and ask what the next years will bring for the continuing relationship between Bermuda and Canada as well as the artists who choose to work between them. n

1 For a study of the history of Canadian artists in the Caribbean, see: Elizabeth Cadiz Topp, Endless Summer: Canadian Artists in the Caribbean, 1988, Ontario: e McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

2 Early artists associated with the British Royal Navy who left behind a substantial artistic record in clude George Tobin and omas O’Brien Mills Driver. Rosemary Jones (ed.), Masterworks at 25, 2012, Bermuda: Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art, 18.

3 Pat Jessup, “C. Anthony Law and ‘An Artists Paradise,’” 2009, Master’s Dissertation, Saint Mary’s University, 188, 136.

4 Duncan McDowall, Another World: Bermuda and the Rise of Modern Tourism , 1999, London and Bas ingstoke: MacMillan Education Ltd., 28–31.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid, 99.

7 As with many North American artists of the period, the Parisian academies, such as the Académie Julian and the Académie Colarossi, were well tra cked by Canadian artists. Examples of Canadian artists who studied in Paris include John Lyman, Emily Carr, Emily Coonan, Randolph S. Hewton, Isabel McLaughlin and Prudence Heward, to name only a few. Another popular European study destination was Berlin, where Lawren S. Harris studied from 1904–07. Some artists chose to study in the US, for instance David S. Milne at the Art Students League in New York and Anne Savage at the Minneapolis School of Art. Joan Murray, e Birth of the Modern: Post-Impressionism in Canada, 1900–1920, 2001, Oshawa: e Robert McLaughlin Gallery, 42–142.

8 Of the artistic movements that Canadian artists were exposed to, one of the most influential was un doubtedly Post-Impressionism, a term which groups a range of artists such as Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse, who had a primary interest in the structuring relationship between col our and form. For a history of the influence of Post-Impressionism on Canadian art, see: Murray, e Birth of the Modern

9 Linda Abend, Duncan McDowall & Edward Harris (eds.), John Lyman’s e Old Bermudas: A Study of Bermuda’s Vernacular Architecture, 2023, Bermuda: e National Museum of Bermuda Press, 6.

10 This manuscript is now reproduced in full in The Old Bermudas e original manuscript is held at the Bibliothèque nationale et Archives nationales du Quebec in Montreal (Fonds John Lyman ID#523256).

11 Michèle Grandbois, “Morrice and Lyman: e Light of Exile,” in: Morrice and Lyman in the Com pany of Matisse, 2014, Ontario: Fire y Books Ltd, 67.

12 John Lyman’s e Old Bermudas, 9.

13 For instance, Tunisian paintings such as Hammamet (1920, Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec), featured on page 67 of Morrice and Lyman in the Company of Matisse

14 Charles C. Hill, Canadian Painting in the Thirties , 1975, Ottawa: The National Gallery of Ca nada, 125–6.

15 Ibid., 132.

16 Frances K. Smith, David Karel, Ted Biéler & Philippe Baylaucq (eds.), André Biéler: An Artist’s Life and Times, 2006, Ontario, Canada: Fire y Books, Ltd., 43–47.

17 Ibid., 44.

18 Ibid

19 Ibid

20 Information quoted from a conversation with art historian and author of the Bush catalogue raisonné, Dr. Sarah Stanners, August 18, 2023.

21 Ibid. Although currently untraced, Bush created another 1939 Bermuda watercolour based on Old Maid’s Lane

22 The noted work is: Karl Struss, Woman with Bananas and Oranges, 1913, modern colour print, Collection of Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art (00108).

23 Karen Wilkin, Jack Bush on Paper, 1985, Toronto: e Ko er Gallery, 9.

24 Charles W. Millard, “Jack Bush,” in: e Hudson Review, vol. 24, no. 1 (Spring 1971), 145; Marc Meyer and Sarah Stanners (eds.), Jack Bush, 2014, Ottawa: e National Gallery of Canada, 63–66.

25 Joan Murray, Isabel McLaughlin: Recollections , 1982, Oshawa: e Robert McLaughlin Gallery, 20.

26 Isabel McLaughlin Collection, Gift of David Aurandt (2008), Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art.

27 Information quoted from a conversation with Mary Handford, October 23, 2023.

28 Matthew Teitelbaum (ed.), Paterson Ewen, 1996, Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 81.

29 Renée Huang, “Palettes in Paradise,” e Globe and Mail, March 21, 2001.

30 Paterson Ewen, 81.

31 For a recent exploration of the relationship be tween the Group of Seven and the landscapes of Canada’s North Country, as well as how they perpet uated and pioneered certain ideas of “North,”

see: Martina Weinhart (ed.), Magnetic North: Imag ining Canada in Painting 1910–1940, 2021, Munich: Prestel.

32 For a history of the Group of Seven and how they became associated with Canada and Canadian identity, see: Charles C. Hill, e Group of Seven: Art for a Nation, 1995, Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada.

33 Endless Summer, 25.

34 Ibid.

35 “Catalogue of an Exhibition of Seascapes and Water-Fronts by Contemporary Artists and An Ex hibition by the Group of Seven,” December 1931, e Art Gallery of Toronto, 5.

36 House, Bermuda, 1937 is described in: Alicia Boutilier, “Mapping an Artist’s Identity: the Life, Work and Writing of Yvonne McKague Housser,” 1998, Master’s esis, Carleton University, 155.

37 Magnetic North, 17.

38 Jacques des Rochers and Brian Foss (eds.), 1920s Modernism in Montreal: e Beaver Hall Group, 2015, Montreal and London: e Montreal Museum of Fine Arts/Black Dog Publishing, 218–32.

39 “Hester,” Agnes Etherington Art Centre, agnes.queensu.ca/explore/collections/object/hester/, accessed February 12, 2024.

40 For discussion of issues of race in Heward’s portraits, see: Julia Skelly, Prudence Heward: Life & Work, 2016, Toronto: Art Canada Institute, 30–32. For information on Heward’s hiring of models for her portraits, see: Barbara Meadowcraft, Painting Friends: The Beaver Hall Women Painters , 1999, Montreal: Vehicule Press, 120–21.

41 “Mapping an Artist’s Identity,” 159–73.

42 As revealed by McLaughlin, who owned the

painting, Heward employed a model in Toronto and used studies made in Bermuda to inform the background of the painting. Joan Murray, Part I: The Isabel McLaughlin Gift, 1987, Oshawa: e Robert McLaughlin Gallery, 27.

43 e Gazette (Montreal), May 6, 1950, 22.

44 Gabrielle Humbert, “Dorothy Stevens ARCA: An Appreciation of Her Exhibition,” The Royal Gazette, September 21, 1946, 6.

45 e Royal Gazette, October 1, 1946, 2.

46 Charmaine Nelson, “Coloured Nude: Fetishization, Disguise, Dichotomy,” RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review, vol. 22, no. 1/2, 1995, 97–107.

47 “Readers Solve Picture Puzzle,” e Royal Gazette, February 28, 2003.

48 Bermuda National Gallery, “Byllee Lang 1908–1966,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xc7QvNdJ-aE

49 Ibid

50 “Big Cathedral Funeral for Noted Sculptress,” e Royal Gazette, December 7, 1966, 10.

51 “Evelyn Fay ‘Byllee’ Lang,” Bermuda Biographies, www.bermudabiographies.bm/Biographies/Biography -Byllee%20Lang.html, accessed February 12, 2024.

52 Jonathan Land Evans, Bermuda in Painted Rep resentation, 2022, 425–46.

53 Brian Flon, “John Hollis Kaufmann,” e Lusher Gallery, lushergallery.com/john-kaufmann-breakingwave, accessed February 12, 2024.

54 Bermuda in Painted Representation, 410–11.

55 Another World, 182.

56 Information related in conversation with Jon Sasaki on January 3, 2024.

57 Ibid

illhfkd=lrqW=`^k^af^k=^oqfpqp=fk=_bojra^

Aleen Aked

1907–2003

Bay Island/Bailey’s Bay, c. 1936 Oil on board

9 1/2 x 12 1/2 in.

Gift of Joe & Claire Smetana, 2003

Bermuda Scene, 1930 Oil on board

111/4 x 15 1/4 in.

Gift of Joe & Claire Smetana, 2004

Cedar Tree, c. 1930 Oil on canvas 14 x 17 in.

Gift of Joe & Claire Smetana, 2004

North Shore, c. 1930s Oil on canvas, 18 x 22 in.

Gift of Joe & Claire Smetana, 2004

Summer Cottage, 1936 Oil on board

11 x 15 1/4 in.

Gift of Joe & Claire Smetana, 2004

Frank Drummond (F. D.) Allison 1883–1951

Beach with Rocks, c. 1935–37 Oil on board

211/2 x 25 in.

Purchase, 1989

Cottage, Bermuda, c. 1935–37

Watercolour on paper

13 1/4 x 13 in.

Purchase, 1989

South Shore, c. 1935–37 Oil on board

113/8 x 15 1/8 in.

Gift of Deborah Butter eld, 1995

St. George’s, 1935 Oil on board

10 1/2 x 14 1/4 in.

Gift of Mrs. Dudley Butter eld, 1991

Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll 1848–1939

Foot of the Lane, 1883

Watercolour on watercolour board

13 x 18 3/4 in

On loan from Tom & Gill Butter eld

Lilies, 1883

Watercolour on paper

14 1/2 x 21 in.

On loan from an anonymous donor

Adrian Baker 1955–

Gombey Drummers, 2009

Acrylic on canvas 20 x 26 in.

Gift of the Artist, 2009

Phil Bergerson 1947–

Bermuda Sightings IX, 2000

Photograph, C-Type 15 x 15 in.

Gift of the Artist, 2000

André Biéler 1896–1989

Front Street, 1921 Oil on canvas

15 1/2 x 19 1/4 in.

Purchase, in memory of Sir David Gibbons, 2002

Hamilton, 1921

Oil on canvas, mounted on board

15 1/2 x 19 1/4 in.

On loan from the Bermudiana Foundation of Canada, 2004

Jack Bush 1909–77

Fort St. Catherine, Bermuda, 1934

Watercolour on paper

7 3/8 x 9 1/8 in.

Gift of Mr. & Mrs. Hunter ompson, 1988

Old Maid’s Lane, 1934

Watercolour on paper

8 1/2 x 7 1/4 in.

Gift of George & Martha Butter eld, 1988

St. George’s, Bermuda, 1934

Watercolour on paper

7 1/4 x 8 1/2 in.

Gift of Somers Realty, 1988

House and Figure, St. George’s, 1939

Watercolour on paper

18 1/2 x 24 in.

Purchase made possible by the London Marathon, 1989

Tom Butter eld 1948–

Dinghy Race, 1988

Photograph, Gum Bichromate

12 x 15 in.

On loan from Tom Butter eld, 2000

Nora F. E. Collyer

1898–1979

Bermuda, c. 1929

Ink on paper

6 3/4 x 6 3/4 in.

On loan from a private collection

St. George, Bermuda, c. 1929

Ink on paper

6 1/4 x 7 in.

On loan from a private collection

St. Peter’s Church, St. George’s, Bermuda, 1929

Oil on board

9 1/4 x 13 in.

On loan from the Bermudiana Foundation of Canada, 2012

Alberta, c. 1949/50

Oil on canvas board

24 x 20 in.

On loan from a private collection

Charles Fraser Comfort 1900–94

Jackman’s Cove, 1978

Oil on canvas

19 1/4 x 25 1/2 in.

Gift of Ian & Jenette MacDonald, 2011

Pirates’ Cove, Tucker’s Town, Bermuda, 1978

Oil on canvas

12 x 16 in.

Purchase, 2003

ird Hole, Mid Ocean Club, 1978

Oil on canvas

19 1/4 x 25 1/2 in.

On loan from the Bermudiana Foundation of Canada, 2002

Eva Brook Donly 1867–1941

Southlands, 1916

Gouache on paper

10 3/8 x 14 1/4 in.

Purchase, 1989

Marie-Denise Douyon 1957–

e Road of Need, 2008

Oil on marine plywood

22 1/2 x 22 1/2 in.

Gift of Tom Butter eld, 2008

Charles Graham Eliot 1912–40

Railway Bridge, c. 1930s

Oil on board

11 3/4 x 15 1/2 in.

Purchase, 2005

Tree-lined Cove, c. 1930s

Oil on board

11 3/4 x 15 1/2 in.

Purchase, 2005

Paterson Ewen 1925–2002

Whale Sighting, 1999

Watercolour on paper 11 3/4 x 13 1/2 in.

Gift of Mary Handford, wife of the Artist, 2004

K. M. Graham 1913–2008

Bermuda, c. 1983

Acrylic & pastel on paper 11 x 15 in.

Gift of Karen Hendrick, 2011

Mari Hill Harpur 1949–

One Holstein and Spirit of Bermuda, 2010

Modern photograph 14 x 18 in.

Gift of the Artist, 2010

John Hartman 1950–

Bermuda, 2006

Oil on canvas

30 x 36 in.

On loan from the Bermudiana Foundation of Canada, 2006

View from Gibbs Hill, 2005

Oil on canvas

66 x 60 in.

Gift of the Artist, 2005

Yvonne McKague Housser 1897–1996

Bermuda Tree, 1937

Oil on board

151/2 x 121/2 in.

Purchase, 2005

Fly Fish Replete, 1937

Oil on board 18 x 24 in.

Purchase, 2005

Pink Cottage, 1937 Oil on board 12 x 17 in.

Purchase, 2005

John Hollis Kaufmann 1937–

Low Tide, 2003

Acrylic on canvas 24 x 30 in.

Gift of the Artist & his wife Roxy, 2008

Karen Kulyk 1950–

Looking Over, 1997

Acrylic on canvas

231/4 x 17 3/4 in.

Gift of the Artist, 1997

C. Anthony Law 1916–96

House on the Hill, Church Bay, 1992 Oil on board

131/4 x 15 3/4 in.

Gift of Jane Law, in memory of the Artist, 1998

Mr. Melon’s Garden, Church Bay, Southampton, 1996

Oil on board

131/4 x 15 3/4 in

Gift of Jane Law, in memory of the Artist, 1998

Alexandra Luke 1901–67

Bermuda Dock, c. 1938 Oil on board

9 x 12 in.

Gift of the McLaughlin Family, 2013

Garden and Tree, c. 1938

Watercolour on paper 81/2 x 111/2 in.

Gift of the McLaughlin Family, 2014

John Goodwin Lyman 1886–1967

St. George’s, Bermuda (Century Plant), 1914 Oil on canvas 21 x 25 1/4 in.

Gift of e Bermuda Artworks Foundation, 1997

Bermuda Landscape, 1958 Oil on canvas 16 x 24 in.

On loan from Tom Butter eld, 1994

North Shore Warwick II, 1958 Oil on canvas board 10 x 16 in.

On loan from the Bermudiana Foundation of Canada, 2013

Isabel McLaughlin 1903–2002

Chinese Hats, 1948 Oil on canvas 25 x 25 in.

Purchase, 2000, dedicated to Scott Cooper

Taut Sails, 1961 Oil on canvas 28 x 36 in.

On loan from the Bermudiana Foundation of Canada, 2000

In Isabel McLaughlin: Finding Form:

Harbour Road, c. 1950s Watercolour and graphite on paper 20 x 26 in.

Gift of David Aurandt, 2008

Ted Michener 1941–

Ocean Sails Shop, 2015 Oil on canvas

15 1/2 x 19 1/2

Gift of the Artist, 2015

Joseph Monk 1908–90

Breakers, Bermuda, c. 1959 Oil on canvas

111/4 x 15 1/2 in.

Gift of Deborah Butter eld, 2002

Nicole Peña 1970–

e ree Muses, 2002

Acrylic on canvas

34 x 351/2 in.

Gift of the Artist, 2002

Edward B. (Ted) Pulford 1914–94

Admiralty Cove, 1983

Watercolour on paper 14 x 211/2 in

Purchase, 2000

Dockyard from Spanish Point, 1983

Watercolour on paper 14 x 211/2 in.

Gift of Mount Allison Alumni, in memory of Ted Pulford & Maurice Terceira, 1998

omas (Tom) Roberts 1908–98

Banana Beach, 1979

Watercolour on paper 12 x 16 in.

On loan from the Bermudiana Foundation of Canada, 2006

Spring Day, Gibbs Hill Lighthouse, Bermuda, 1982

Oil on board 16 x 12 in.

On loan from the Bermudiana Foundation of Canada, 2006

The Woolen Shop, 1982 Oil on board 111/2 x 151/2 in.

Purchase, 2001

Jon Sasaki 1973–

Mid-Afternoon on East Broadway, 1996 Oil on board

6 1/2 x 8 3/4 in.

Purchase, 1996

Mid-Morning at the Dockyard, 1996 Oil on board

6 1/2 x 8 3/4 in.

Purchase, 1996

View from the Bench, 1996 Oil on board, 6 1/2 x 8 3/4 in.

Purchase, 1996

Roger Savage 1941–

Scaling Fish, Burchall Cove, Bermuda, 2002

Watercolour on paper 12 x 16 in.

Gift of the Artist, 2002

Dorothy Austin Stevens 1888–1966

Street Scene, 1946 Oil on canvas 15 1/2 x 20 in.

Gift of Bob Stranahan, 2012

Street Scene, Bermuda, 1946 Oil on board 18 x 24 in.

On loan from the Bermudiana Foundation of Canada, 2003

Frederick Bourchier Taylor 1906–87

Bermudian Head, 1955 Oil on board 12 x 9 in.

Gift of Terrill & Michael Drew, 2015

_ÉêãìÇ~=_çí~åáÅ~ä=d~êÇÉåë NUP=pçìíÜ=oç~Ç as=MQ

_ÉêãìÇ~

ïïïKã~ëíÉêïçêâëÄÉêãìÇ~KçêÖ

]ã~ëíÉêïçêâëãìëÉìã

]ã~ëíÉêïçêâëãìëÉìã

]ã~ëíÉêïçêâëãìëÉìã

`çîÉê=áã~ÖÉW=fë~ÄÉä=jÅi~ìÖÜäáå=ENVMPÓOMMOF e~êÄçìê=oç~ÇI=ÅK=NVRMë=EaÉí~áäF

_~Åâ=ÅçîÉê=áã~ÖÉW=gçÜå=dççÇïáå=ióã~å=ENUUSÓNVSTF

_ÉêãìÇ~=i~åÇëÅ~éÉI=NVRU