step

The artist Haegue Yang, with whom I had the honor of conversing (1), described the work I saw as opposing forces that cancel each other out — that the heat lamps were canceled and opposed by the fans, that the red lights above which pulsed down and created small striped shadows on the floor opposed the blinds of varying shapes and angles that filled the gallery space. I said I didn’t understand the role of the drum set in the corner and she said “it plays a very important role.” The drum set produced a white light when played. I thought it was representative of the creative in humanity. Rainier Maria Rilke compares the role of the poet in society to the boatswain on a rowboat — the boatswain calls out the stroke to the rowers so they will pull together; he advises; and cheers them with his song. Black Elk asks why listen to me: I am not the strongest warrior nor the most capable chief. I was a child, living as part of an in-tact civilization and I saw its end after 12,000 years as an adult. “It is the story of all life that is… good to tell.”

Allan Kaprow, upon whom this book is based formally, includes his context of many other artists and shows himself to be one facet of a movement: an ephemeral movement. I am a solitary creature. I know some things about myself and others are as opaque to me as they are obvious to you. At first I wanted to make a portfolio. Then I wanted something I could leave behind and so be known by my peers. Then I thought this book was for me to know who I am and that it bears witness to a way of thinking about things and the world — as an art practice. How long will I practice? I may stop tomorrow or never. It’s hard to know.

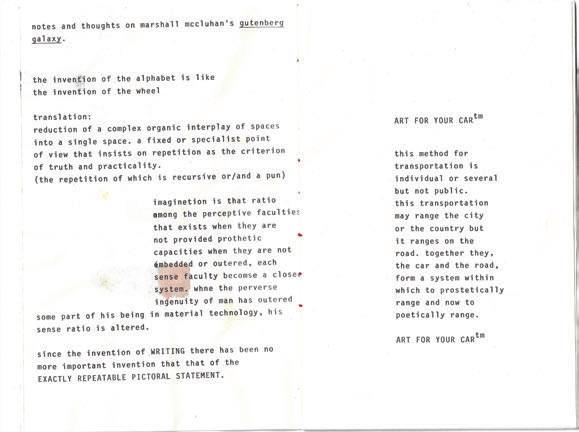

In the book The Information by James Gleick, he says we are moving to the information age. First there was the oral age, and then the written age and now the digital age. The Oral Age corresponds to the age of myth, the nomad, the lithic, the barter: fire. Then came the Written Age: farmed, moneyed: metal in coins, metal in weapons, metal in moveable type. We are now at the cusp of the Digital Age: space-bound, crypto: adhesive.

1 - at the show “Shifting the Silence,” (San Francisco MOMA May 2022)

2 - Rilke, Rainer Maria, Lettres à Un jeune poète, Paris, Le Seuil, 1992

3 - Neihardt, John G. Black Elk Speaks, Nebraska, University of Nebraska, 2014

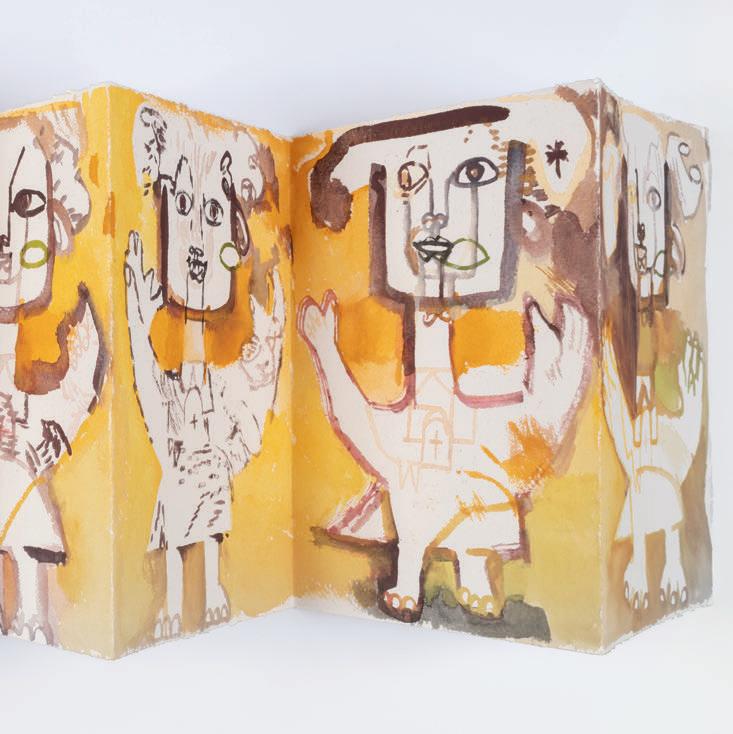

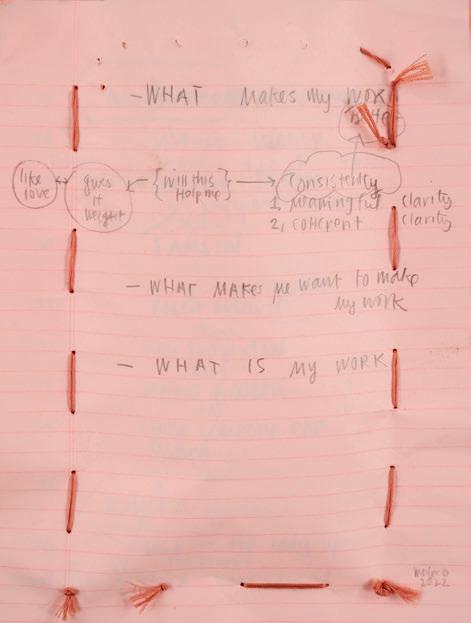

Even someone well versed in contemporary art might well ask, “What the heck is Mary Conrad (aka Marfeco) up to?” If you think too hard to try and place her work art historically or even understand it in some kind of coherent sequence, you are liable to get lost and end up someplace irrelevant. As Mary notes in her Preface to this book, “I am a solitary creature.” She does not waste time reflecting others, nor does she even hanker for an audience. Her generous acknowledgement of inspirations—from the Impressionists to the architectural historian Kenneth Frampton and the conceptual artist Silvia Kolbowski, et al—is not intended as a key to understanding her work. There can be no consistent thread among her works nor between her practice and that of others because Mary’s work is so profoundly situational. One recent work attempted to derive a symbol for the state of being “here now.” In a sense, all of her work takes on this challenge, perhaps not so explicitly, but in the way that Mary boldly gathers from the present moment and her immediate surroundings what is needed to make art.

While this so-fresh-as-to-be-almost-incomprehensible quality pervades her work, there is also a more overtly knowing dimension, one which helps to shape her objects and direct her focus: it is the dimension of a civilized person at the edge of apocalypse, a person who can ask, “What is Shakespeare in a time of climate change?” For Mary, thinkers of the past including Shakespeare, Homer, and Marx, each provide a road along which to travel into knowledge and awareness. Yet, as one particular series demonstrates, the road is never the thing and to the degree that we attend to one, we miss the other. So, even as she praises “voices from the past,” those who have, “been there before you and paved the way,” Mary understands her antecedents’ limit: in the end, when it comes time to make her own art, Mary takes her eyes off the road. This is brave and rare.

One of the first works I saw of Mary’s was based on the broken windows in a barn she saw by the side of the road. I think she must have found the patterns of positive and negative space formally compelling (which they are…resembling some kind of symbolic lexicon or code), yet this image also opened up to her a universe of poetic making. The beauty of the image forestalls the melancholy of entropy, even as this work,

and others it inspired, situate the artist at the crux of life’s energies, as the observer of moments where fabrication and disintegration, transparency and opaqueness, wholeness and fragmentariness resolve. Her works concerning trash and packaging resonate with similar attention and insight.

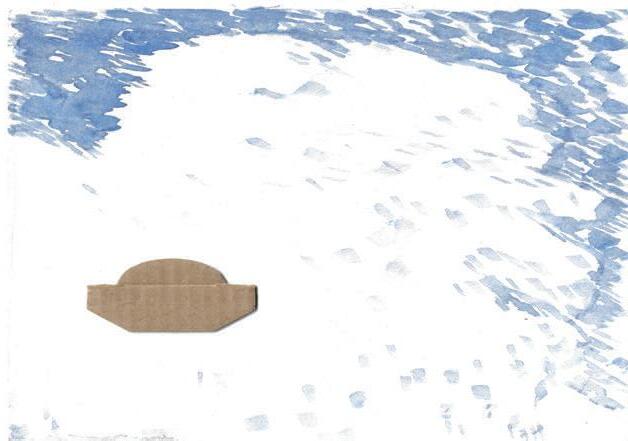

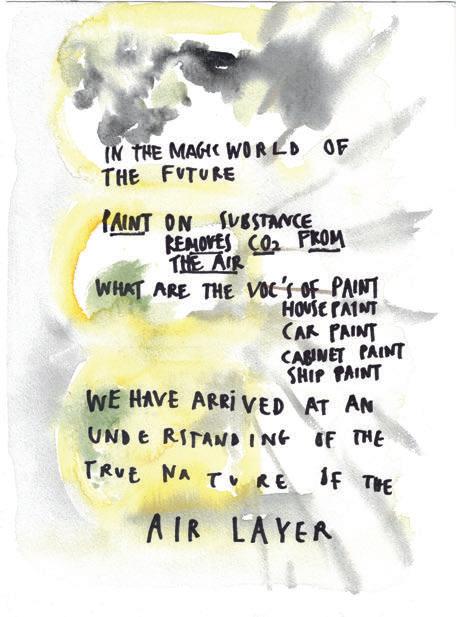

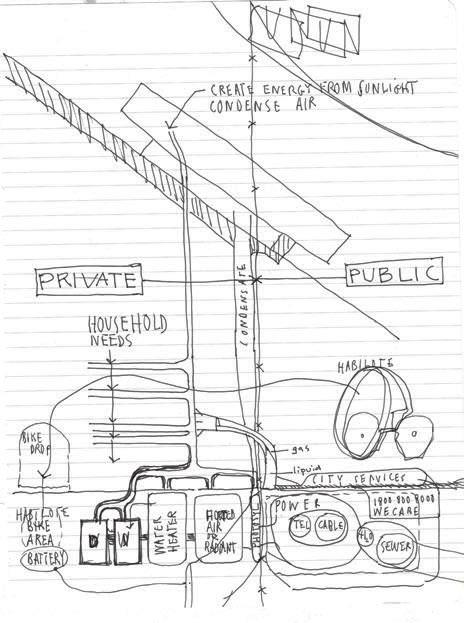

Later, I was bemused to see Mary embark on a mission to create “art for your car,” and, a few years later, intrigued by her effort to create a company that would manufacture and market a system that enables the extraction of CO2 from the air. These projects took her farther and farther from the art world’s orbit. Not that she cared. Mary is an art world of one, a vortex of feeling, concern, and resolve.

Although it may be beside the point to situate Mary’s practice in an art historical continuum, there are certain artists with whom she shares a fierce independence, conceptual approach to materials, and laser-like focus on the present. Among these, I would mention Bas Jan Ader, Gordon MattaClark, and David Hammons. Each of these artists defied convention not out of some Dadaistic need to shock the bourgeoisie, but because their sense of the present required them to act in certain ways, to make things that supported the weight of the moment, and to think of art not primarily as something to show and sell but as an aspect of life.

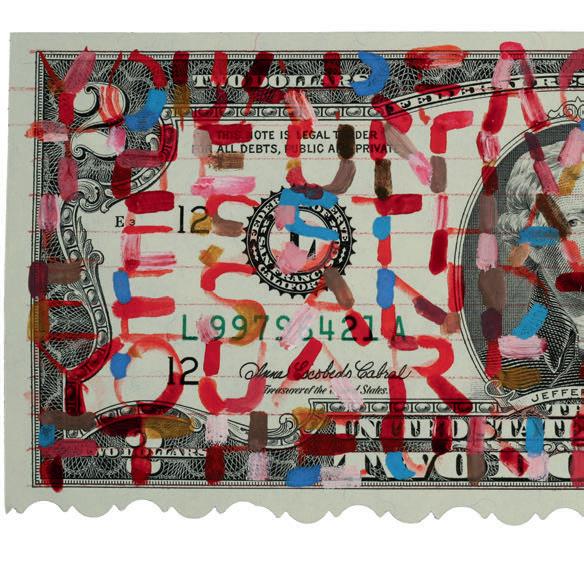

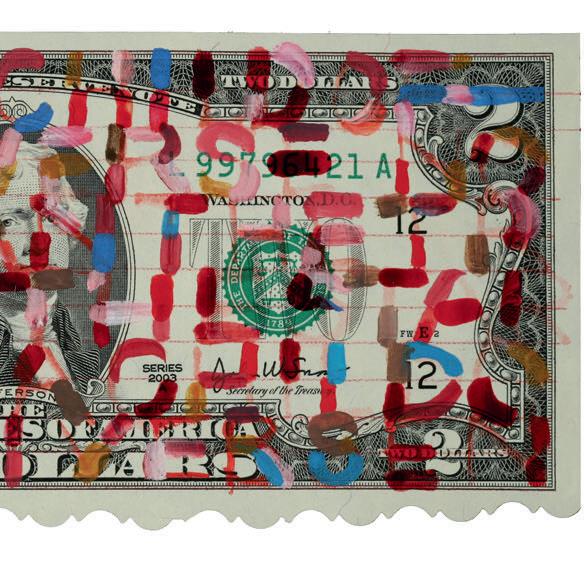

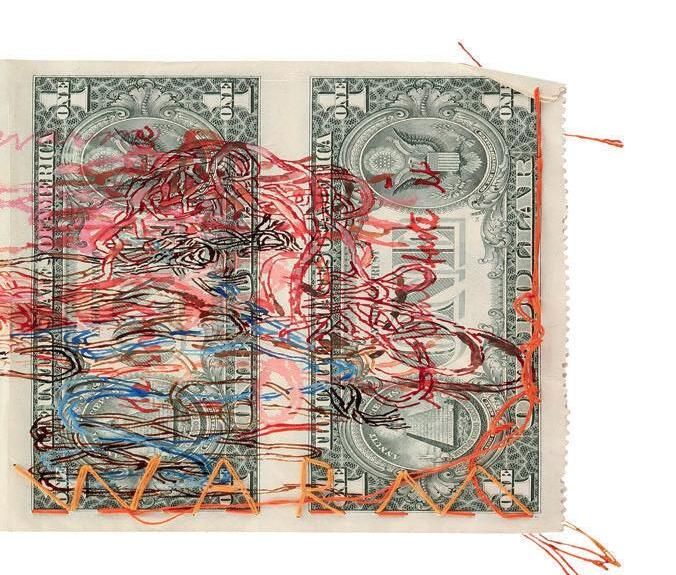

One of the topics Mary has been interested in recently is fungibility, the ability of one thing to be interchanged with another thing of the same type. The likeness of commodities is the basis of economy, of currency, and of any system of commercial exchange. Yet, as she notes, this system collapses as soon as it becomes personal. Nothing is the same as anything else as soon as it has the ability to trigger memory, emotion, or poetry. Mary, who has always lived in the present, also struggles in her art on behalf of the uniqueness of things.

***

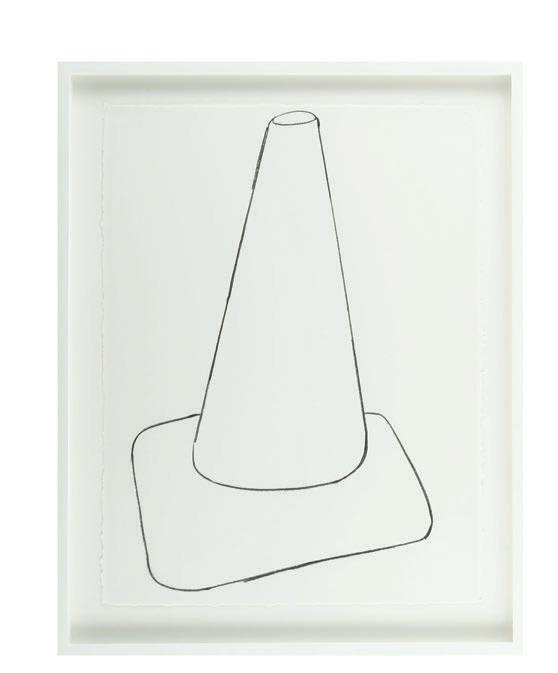

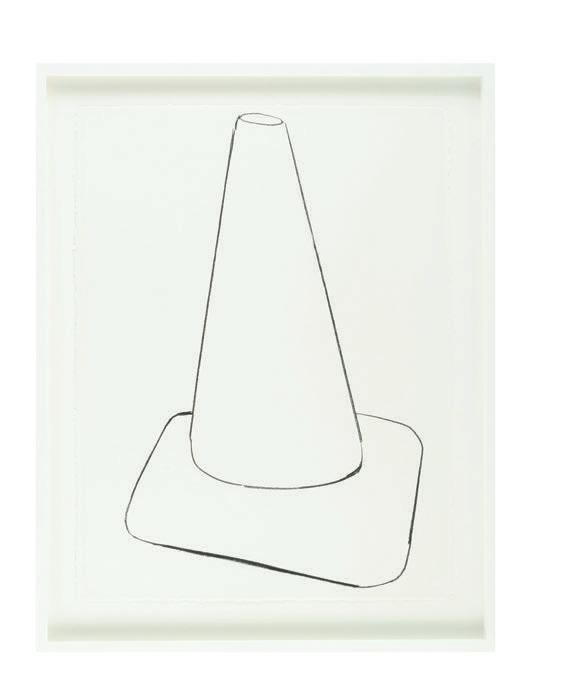

Looking at books, looking around and growing older, I have developed a lexicon as an artist: traffic cones, abstract shapes, colors, garbage, plastic sheeting, acrylic plexiglas, sewing, embroidery thread, currency, light from a source like neon or fluorescent tubes, painting, sketching, watercolor photographs, sharpies, tape, stickers, cardboard, postage, and, yes, books books books.

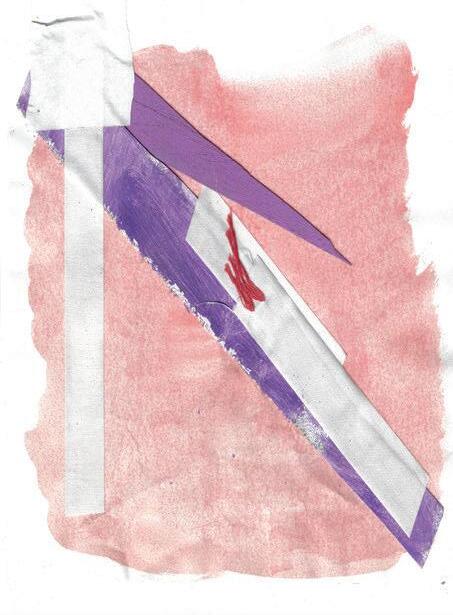

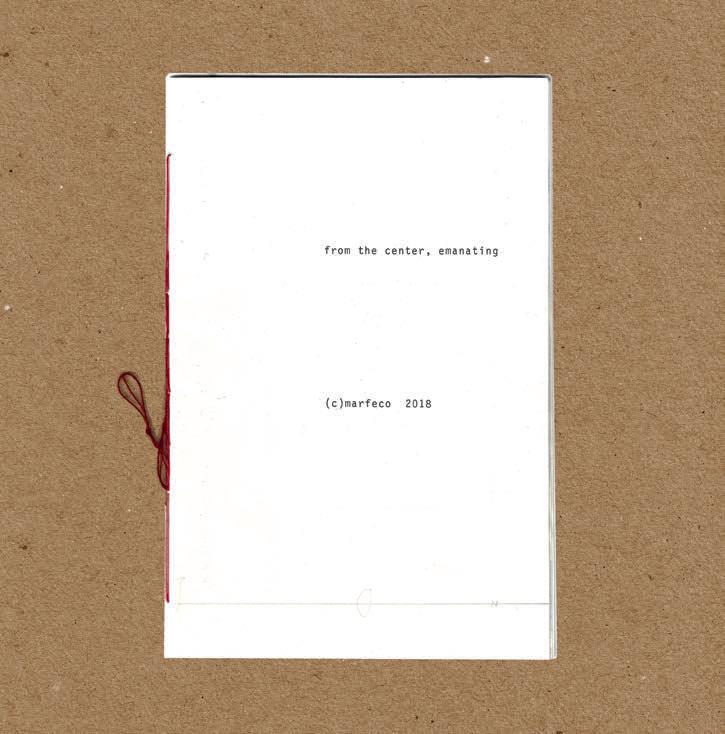

From the Center, Emanating, 2018, pencil, embroidery thread, watercolor on watercolor paper, 8 ½ x 5 ½ inches

From the Center, Emanating, 2018, pencil, embroidery thread, watercolor on watercolor paper, 8 ½ x 5 ½ inches

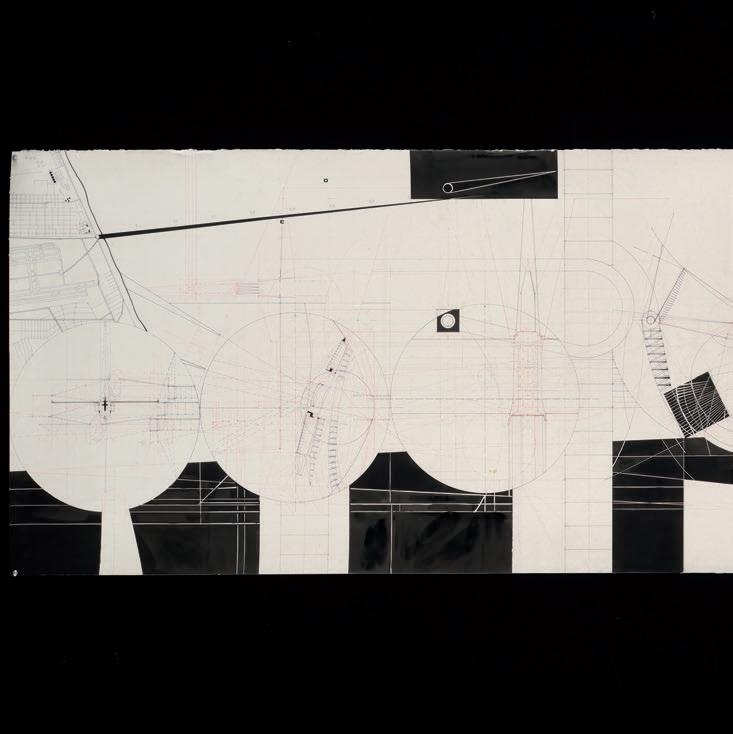

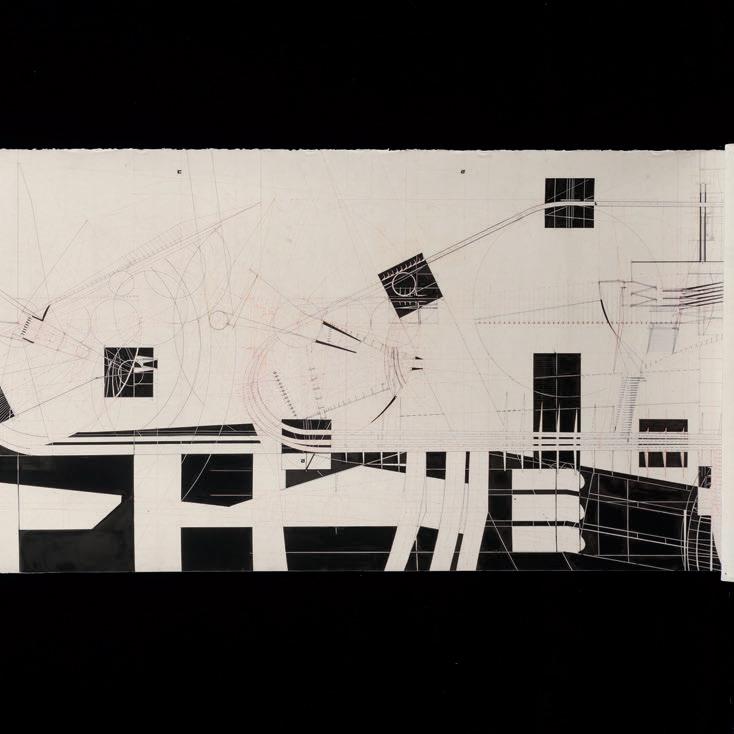

I placed out of biology at university, and so I took drawing classes at the art school. By the time it came to take bio classes, I had forgotten everything so I switched. Then I graduated and what was I going to do? So I applied to graduate school. I studied architecture at the GSAPP, Columbia University. The first year syllabus was put together by Steven Holl. It was its second year being taught, so they had worked out the kinks, but didn’t know what they wanted to see. I had Liz Diller as my second semester professor. It was a moment I will always cherish and her insistence on the conceptual capacity for whatever you chose to use to make had a big impact on me. It was a fantastic education. I worked for Ken Frampton, but more importantly, I audited his class. I took art classes across the way and I took an art history class on Matisse with Jack Flam.

One of the universe’s great gifts to me was that I loved being a mother.

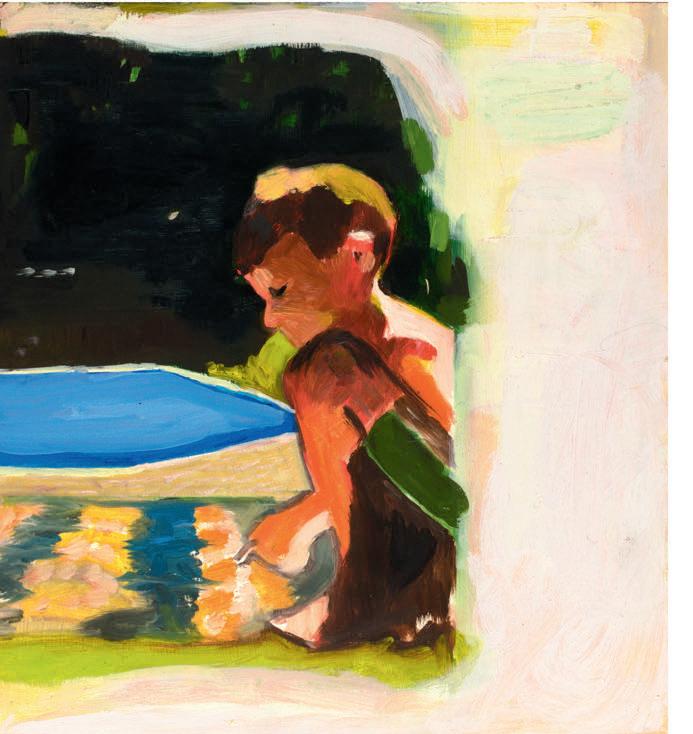

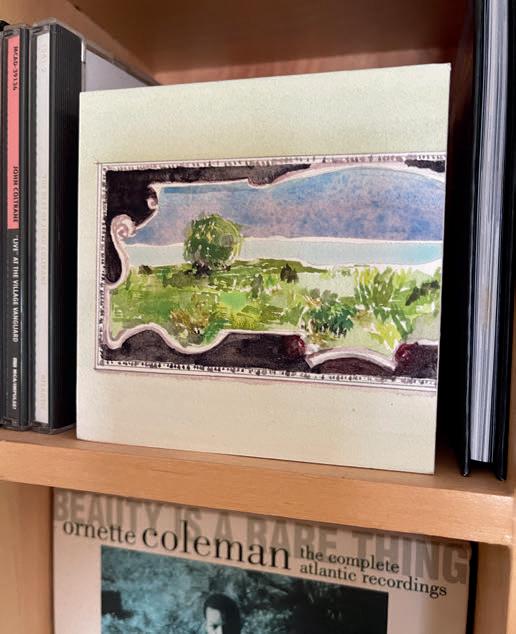

In Martha’s Vineyard at Robbie’s House, By the Pool (diptych), 2002, oil on Masonite, 17 x 31 inches

In Martha’s Vineyard at Robbie’s House, By the Pool (diptych), 2002, oil on Masonite, 17 x 31 inches

Once nature decided it would have sexual reproduction, (as opposed to asexual reproduction, like a virus, using mutation to change the genetic code) then there is by definition a male and a female: one who fertilizes the egg and one who holds the egg.

& I am not only female, but a female mammal.

With this reproductive apparatus: hormones, gestation, lactation.

& there is culture too.

But if you are lucky, the building of the future’s human concerns and priorities.

Alphabets are a convenient, traditional, widely-understood

that people communicate with one another through written language.

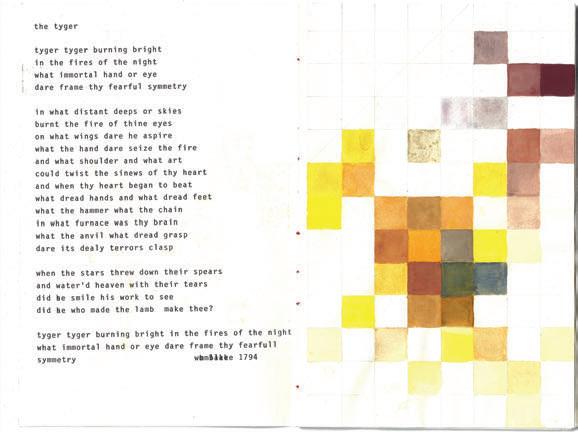

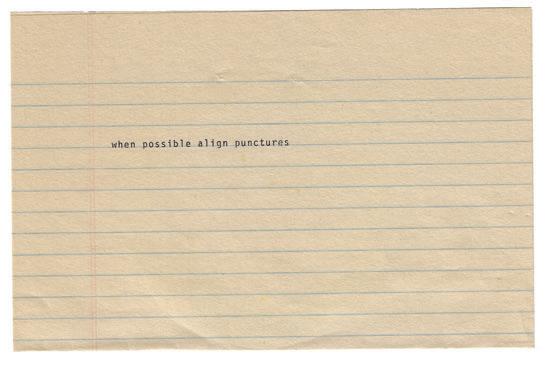

I was working in the shipyard. I had sublet a studio for $160 per month from another artist named Patricia Diart. She described her practice: she would put on a man’s suit and go to various parts of the city - say the beach - and perform various actions like walking into the water fully clothed carrying her briefcase, pouring sand on her head. I went home and marveled to my husband that we were on a continuum, that we did the same work. After 4 months, she wanted it back, but the landlord of the building who worked upstairs gilding frames, told me of another space he had available. You had to enter it through someone else’s space and it was the fire exit aka smoking lounge for the building, but it was mine for the taking. Every morning I went to my studio. After dropping the kids off at school and getting coffee at Farleys, I’d arrive and change into my painting clothes. Then I would walk the dog on the deserted beach through the deserted shipyard. The dereliction of the man-made environment; buildings that had been boarded up, paint peeling and supposedly radiation under the ground: a superfund site. I came across a pair of windows with broken glass. Like the portals of old gothic cathedrals, or the ten commandments, or an endpaper with an Arthur Rackham illustration (1) Then I would listen to the same piece of music (2) and walk around my space. What was I making? What did I care about? What were my artistic concerns and methods? What story was I telling? Even now it is one of my ways: make marks and think. The method of communicating has been vastly enlarged by books. Voices from the past, from faraway, at a pace that makes sense for you, within the discipline that you’d like to know more about: books, alphabets, writing. The road is another, physical experience akin to language, to writing. Someone has been there before you and paved the way. It is determining where you go. Alphabets, roads, symbols, the periodic table of elements, the human need to codify, to put in order - from where I stand now, these are my concerns. The earliest form of writing that I know of is Assyrian cuneiform and it’s actually a form of mathematics, of accounting, of keeping track of how many cows or sheep you have. If you have a lot of cows, you put them in barns and so the letters “AB” is a cowhouse. (3)

I used sewing to talk about being the female of the species: quilting, a wife. Penelope making Odysseus’ shirts and waiting while the male went to war. Being pregnant. Being traded for two sheep. As I continue to be female, even though I can no longer bear children, sewing is part of my lexicon as an artist.

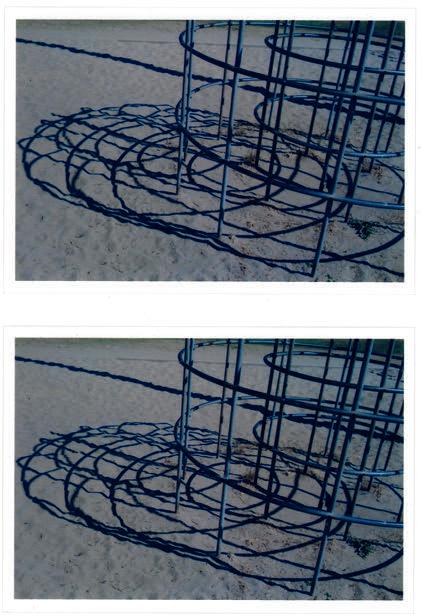

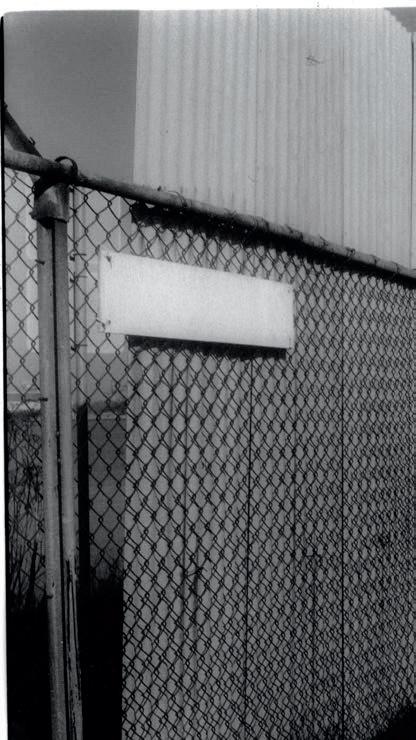

Fence on Potrero, 2005, photograph, 6 x 4 inches

Fence on Potrero, 2005, photograph, 6 x 4 inches

Walking in an arroyo, I mistake a rock in the distance for a person, which on approach emptied of him, denser than a mirage.

I fear an object can be negated by thinking, as it remains in sight.

Though I say, “It’s basalt shaped like a man,” his menace is seamless.

- Mei-Mei BerssenbruggeMary Conrad saw a building on the side of the road. Its windows were missing shards of glass.

It is a nondescript building, the most distinct feature just a faded ochre slab of wood framed by a white barn door.

Above the moment of color sit dark windows, painted by absence. In the places where the reflective paneling is broken, an opacity is arranged by shadow geometry. It’s the blackest of blacks, one which cannot be created, can only be made through removal.

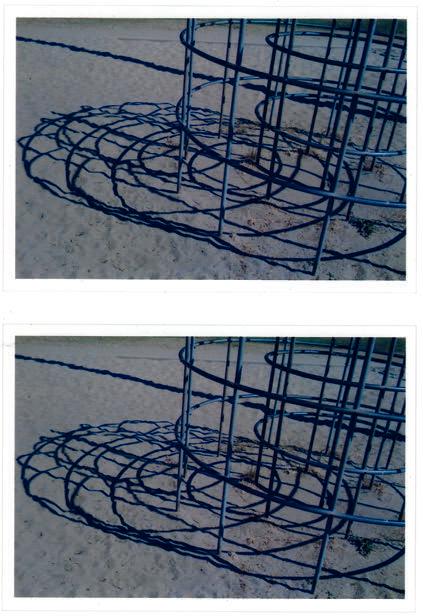

Timothy Morton: “A mesh consists of relationships between crisscrossing strands of metal and gaps between the strands. Meshes are potent metaphors for the strange interconnectedness of things, an interconnectedness that does not allow for perfect, lossless transmission of information, but is instead full of gaps and absences.”

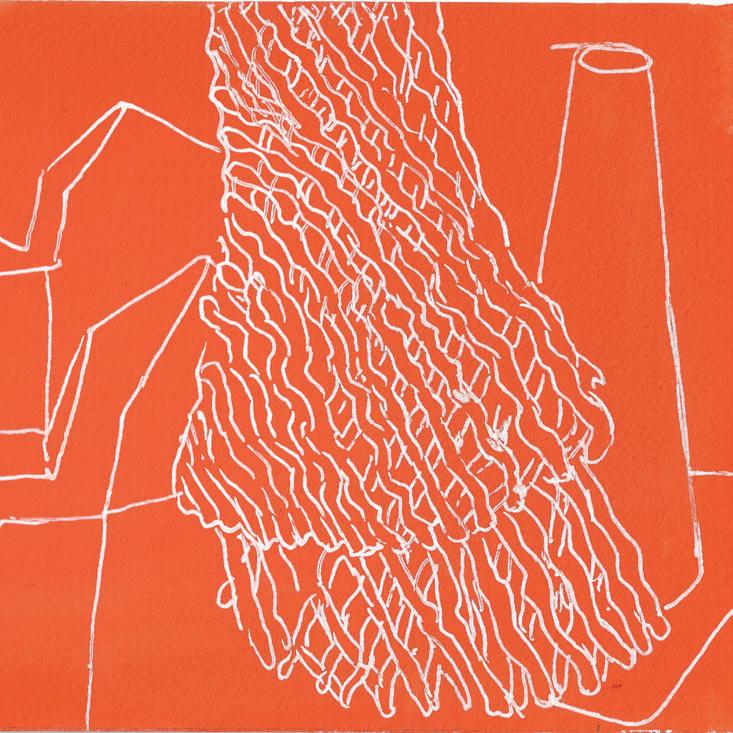

With the brush, and an architect’s set of questions, Conrad is often painting the mesh.

For Morton, the mesh is primarily a way to think about nature. Well not nature, nature is already a word humans created to mount an artificial division between ourselves and the world we live in. The mesh is a way of thinking about the tangible presence of environment, and rather than othering it, holding it in active entanglement.

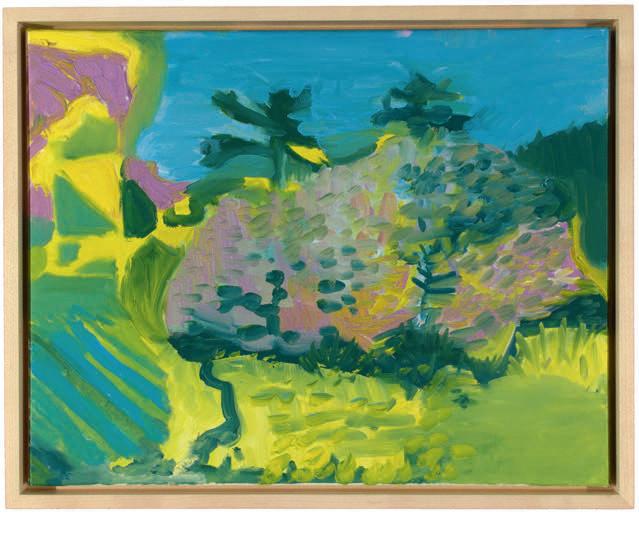

Mary Conrad’s garden is difficult for those accustomed to landscaped nature to discern. Her beds of native plants exist outside of strict boundary, easily cascading into the ‘unmaintained’ wild that creeps over and under the idea of private property. Looking at her garden, we understand her practice.

Chimes at Midnight, a film based on a play, was in many ways Orson Welles’ first dramatic undertaking, carried-over from a three and a half hour adaptation of Shakespeare that he put together as a teenager at the Todd School for Boys. When reworking the theatrical production for film, Welles cut out all true soliloquies and refused to shoot any scene in which he’d have to be on camera alone. Apparently he suffered from loneliness, missed the company of the stage and its audience. He also drank often, cut rehearsals, and refused to memorize the script. The resulting work, perhaps the best work of his career, is fragmented and abstracted, broken over and given in to emotion.

The poet C.A. Conrad uses ritual when writing. He opens himself to the presence of otherness, to the otherness of other people, as Emmanuel Levinas would say, hoping to be totally possessed by encounter. In the poet’s collection While Standing in Line for Death, he includes works written during a period he spent embodying the perspective of endangered songbirds. Writing under the moniker of regional bluebirds, finches or thrushes, he emailed strangers with bibliographical, light introductions. As he slowly built trust, the librarian or elementary school teacher tone adopted in early exchanges would shift into one of extreme vitriol and rebuke. Beautiful poems of indignation and extreme feeling then take form.

An excerpt from C.A. Conrad’s For the Feral Splendor that Remains: earth might be interesting to a visitor one day chewing parsley and cilantro together is for me where forest meets meadow in a future life would we like to fall in love with the world as it is with no recollection of the beauty we destroy today

To see the world and represent it with precision means to willfully lose your sense of individuality. In many of Conrad’s works, we see elements of found language and imagery. Much like the readymades of the surrealists, or the work of conceptual artists, her practice is grounded in attention to the existing world. Or, to quote the artist, on “ form which hovers on abstraction / abstraction which hovers on form.” In this way, she’s almost recycling art, demonstrating that contemporary representation is more about directing the gaze than constructing reality. It’s all already there.

Just after Orson Welles arrived in London to film The Third Man, weeks late and with a put-on cough, an exasperated Carol Reed lost him in the underground subway system. With crew in place, the lights carefully describing the scene, and the director coercing his own phobia of underground spaces, Welles bore a smile of bemused malevolence and took off. From the shadows, his voice echoed a demand that Reed keep shooting. And after several minutes he reappeared, thrashing through an underground river, finding perfect illumination beneath a dark cascade of gutter water. He let some invisible weight crash him to his knees, and then slowly as if under a spell, put up his hands. This improvisational, almost compulsory instinct to submit himself to the environment became the film’s most important moment. It’s “art” in the mesh.

The painter Joan Mitchell has said it was primarily the wind that she was trying to paint, that without the wind she’d never have become a painter. Many of the things artists say about their own work feels obtuse or hard to grasp. This registers immediately true. It teaches you how to look at her work, In which feeling and movement are intricately enmeshed.

An artist’s primary occupation should be sensitivity.

Mary Conrad said that it was in the moment she stopped on the side of the road to look at the absence of light defined by shattered glass in a barn’s window that she began to make art. Her consideration at that moment, and throughout her practice, is one attuned to gaps and absences, to the crisscrossing of materials, to keeping the invisible in mind.

***

Theadora Walsh is a writer and video artist from San Francisco who makes moving texts, essays, and curation. She works with the physicality of language and the tension between speech and its documentation. Her writings can be found in Gulf Coast, Los Angeles Review of Books, BOMB, SFMOMA Open Space, Apogee, Artforum, Art in America, and elsewhere.

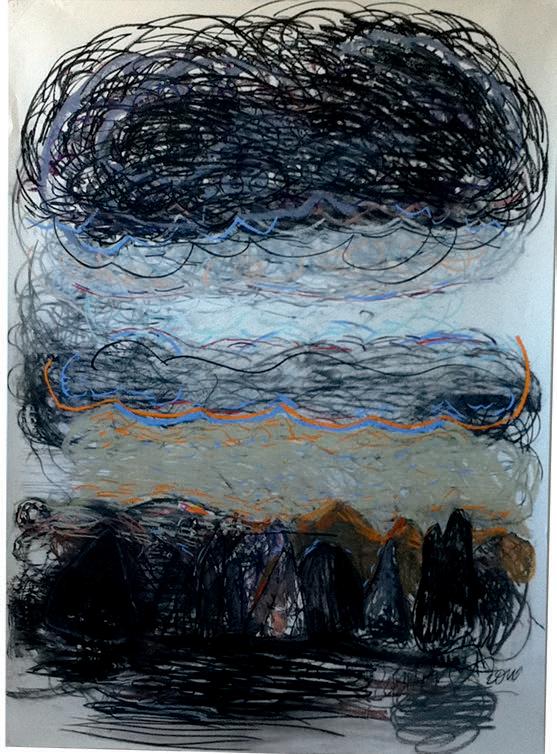

Violet and Ochre, 2018, oil on canvas, 72 x 120 inches; installed at Gospel Flats Farmstand Gallery

Violet and Ochre, 2018, oil on canvas, 72 x 120 inches; installed at Gospel Flats Farmstand Gallery

Roberta Smith wrote about “the human need for mark-making.” There have always been artists – writers, musicians, painters - as long as there have been people.

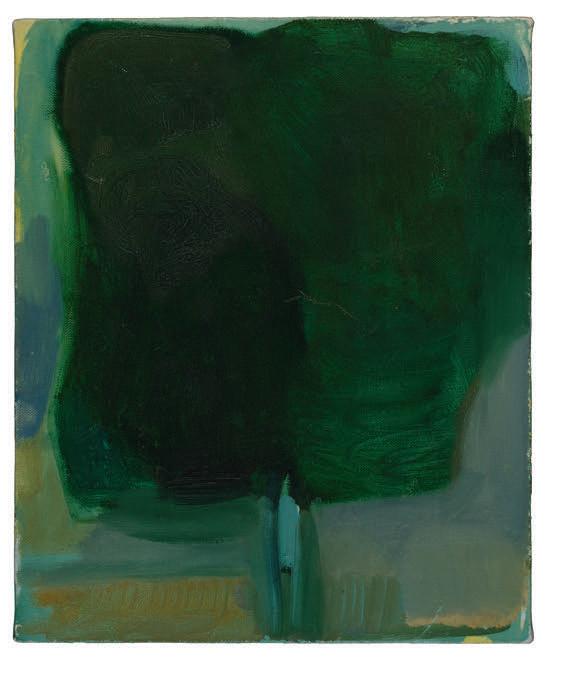

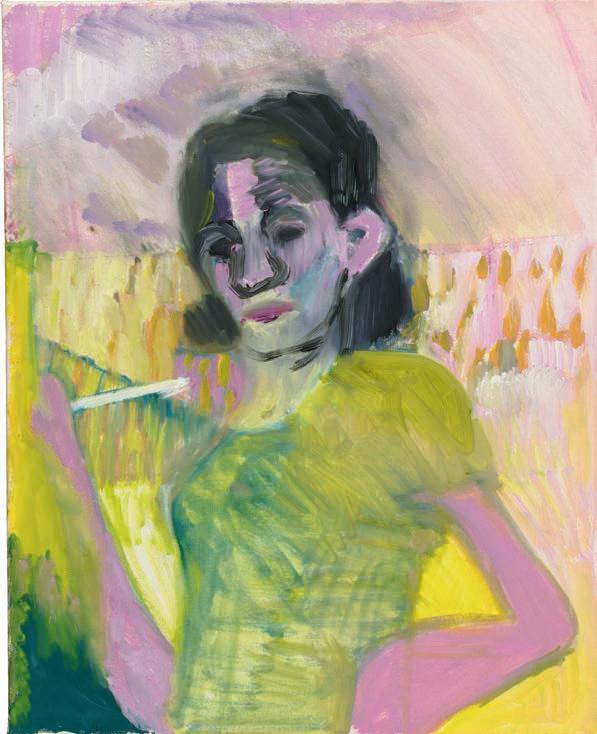

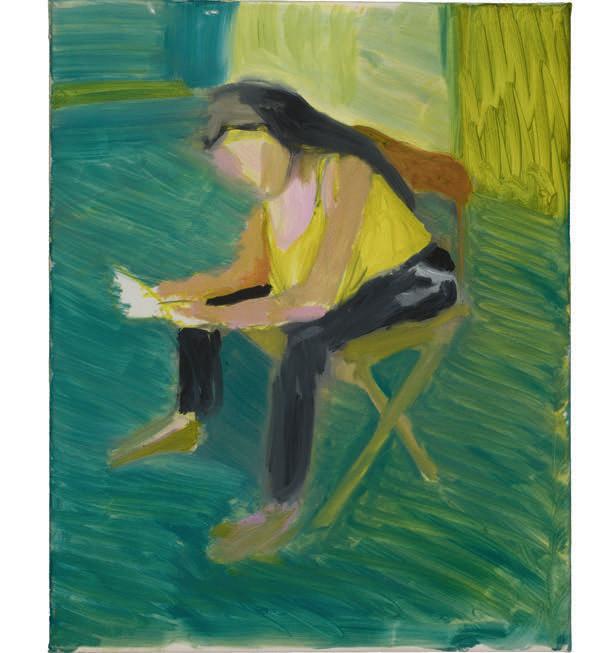

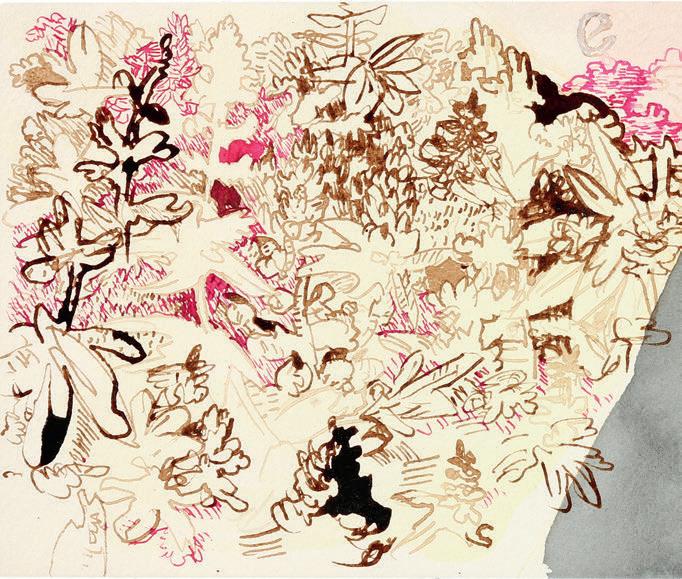

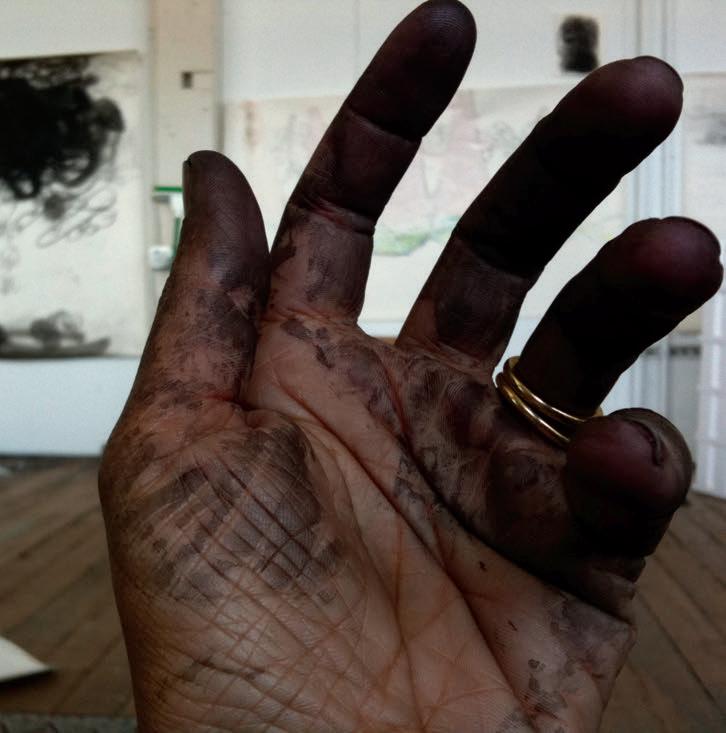

For Mary Conrad, painting is an exploration of sight. The artist, who was trained in early life as a biologist, is enamored with the function of seeing and the ways we process visual information. While the majority of Conrad’s work is highly cerebral and systems-based, her paintings offer a grounded analysis into one of our universal and foundational truths – our ability to see. She uses painting as a method of thinking and a tool to shift from her mind into her body. This is a crucial step in information processing that allows the artist to bring forth nascent creativity. It is through the act of seeing that she moves out of her mind space into the physical realm.

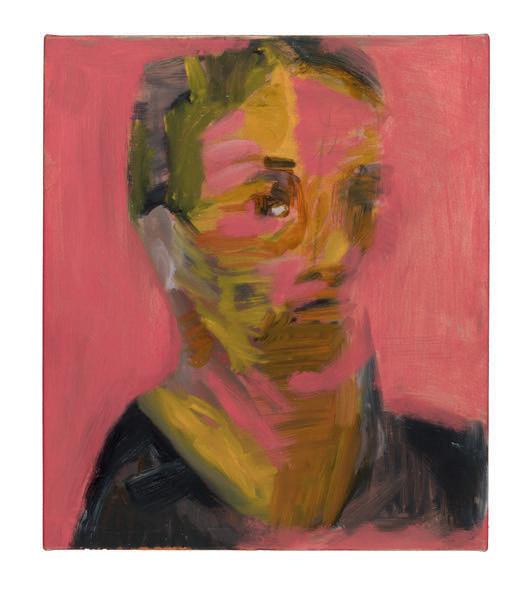

The artist often muses on the pleasure in seeing and is fascinated by the mysterious and wonderfilled mechanisms behind the act of sight. Viewing most of her experience through a scientific lens, the artist thinks about the eye as an organ – its intake of light as wavelengths, the processing of color, and our brains’ ability to make sense of what we see. Philosophically, she views seeing as a kind of a magic – defined by the liminal space between knowing and not knowing. That is why, as she describes, the world is magical to children, who are in continuous awe of their surroundings as they attempt to make sense of their experience. Conrad remarks on walking through the Impressionist rooms at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the delight in seeing the quality of color, the use of light, the textures and shape. Conrad’s work is influenced by painters like Paul Cézanne who, like his Impressionist peers, are able to paint not only what they see, but what they feel, in an exploration of our spectacular and uncanny ability to observe and enjoy.

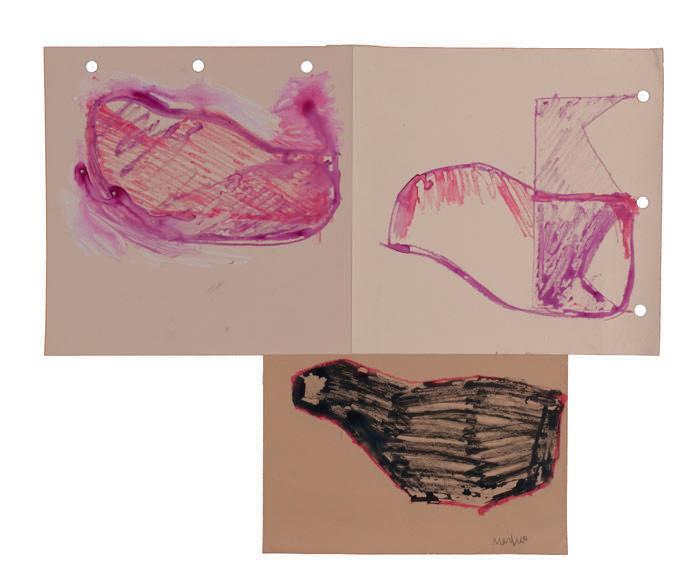

At the genesis of Conrad’s painting process, she is visually struck by something so moving that it becomes a catalyst for a series of subsequent investigations. Sometimes she will take a photograph or create a sketch as she slates her painting. Each expression is a way to see the subject new. She explores her love of artist materials, like Arches Watercolor Paper, Kremer and Blockx paints, and Conté crayons, that root her in physicality and allow her to watch as her vision unfolds under different mediums. Whether a sketch on toothed papers or saturated paint on canvas or board, every iteration becomes a variance in sight that brings Conrad one step closer to who she is and what she wants to say.

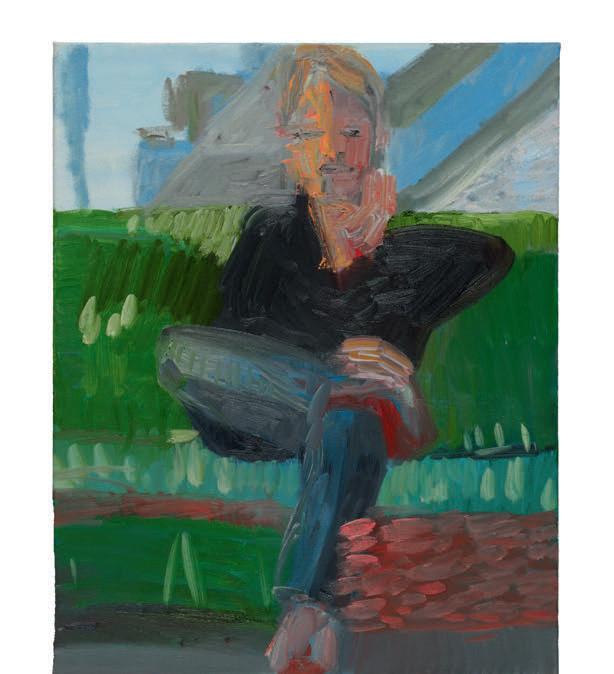

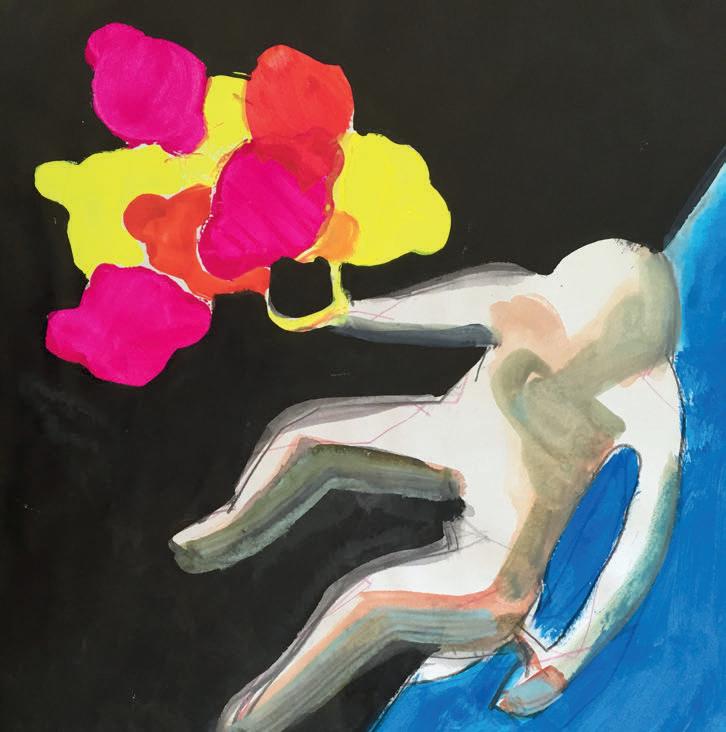

Her subject matter includes Impressionistic interpretations of lush gardens and tall trees, intimate portraits of her family and friends, or large canvases of shapes and colors that fill the walls of her studio. Her subject matter is two-fold, working in both figuration and abstracted compositions. In her figurative work, she chooses loved ones to paint in ecstatic color. In Tony, Conrad paints her husband in loose expression, a beloved figure softening into the lilac sky and natural landscape behind him. The piece is curious, like it is exploring a secret that only the artist and her partner know. She sees not only the physicality of her sitter but the magic and unknowingness that’s present between them.

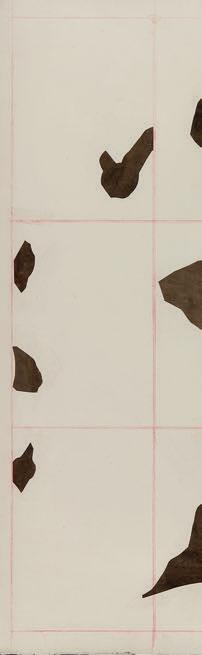

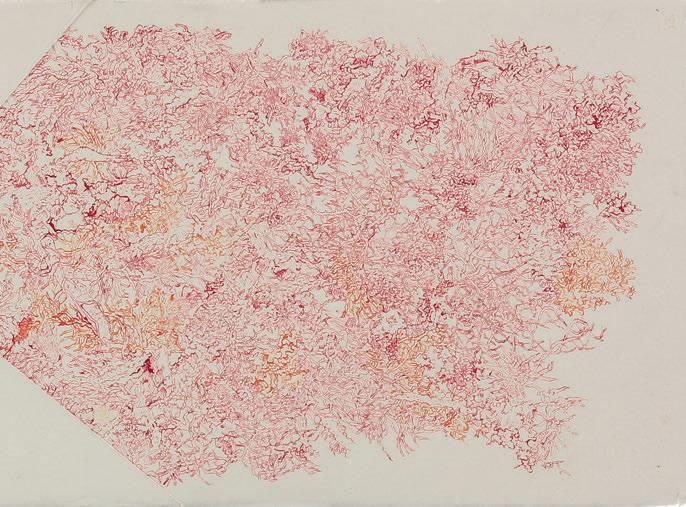

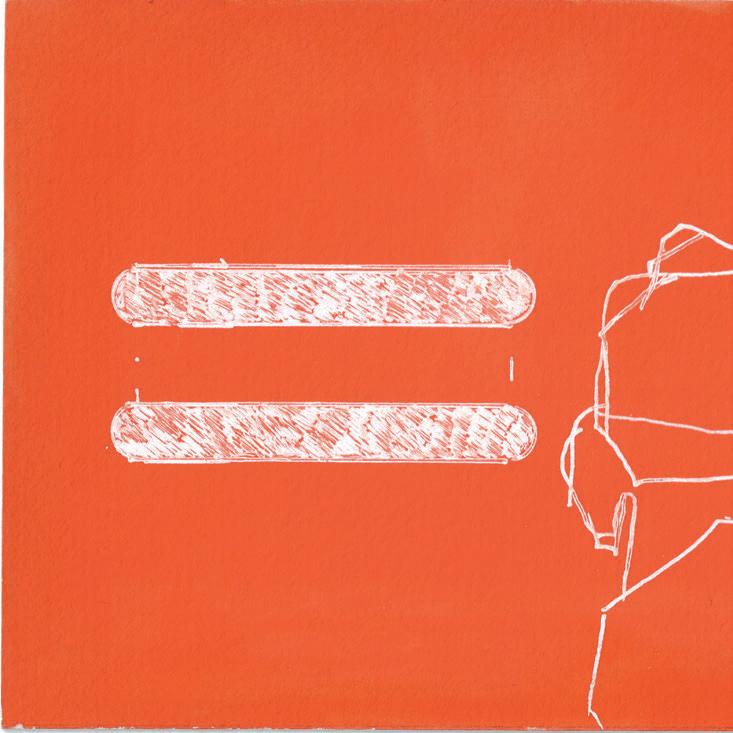

Some of Conrad’s work reaches even further into abstraction. But because she lives and thinks in a very concrete world, she chooses to anchor even her most abstract pieces in something tangible and, oftentimes, universal. In her Alphabets series, she explores her fascination with language and alphabets as shape, form, and meaning. Marked in her oeuvre by grids containing amorphous shapes, the series uses visual cadence and repetitive gestures to navigate the act of pattern-seeking and the

process of turning visual information into something coherent and significant. She uses the ambiguous forms to mimic our continuous search for meaning, a process that humans have labored over since the dawn of the species. It is the suggestion of a story, rendered in contained, rhythmic space and abstract marks, that elicits a curiosity in the viewer to make sense of its message. As if bringing us back to our preverbal state, we experience the phenomenon of trying to know.

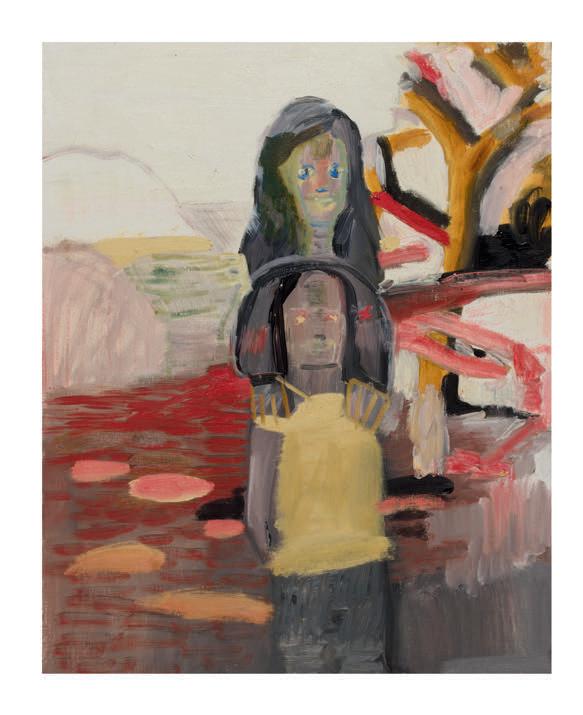

Conrad’s sculptural work is highly conceptual, often centering existential theory and societal infrastructure with a focus on the ways humans have built and engage with their environment. She is heavily influenced by climate change and uses her mathematical and architectural background to inform much of her work on the subject. Though this part of her practice is disparate from her paintings, she applies the same exact care to it as she would a portrait of a loved one and uses her painting practice to guide her into attention to the larger systems at play. She says, “I’m a painter like Rauschenberg is a painter,” who skillfully blurred the lines between painting, mixed media, and sculpture while maintaining a conceptual centrum. Conrad similarly frees herself from one medium as she examines the ways in which macro-systems and our inherent drives influence our collective experience and our dynamic need to progress. Like in In Martha’s Vineyard at Robbie’s, By the Pool, a diptych of her two sons who are long since grown, the artist witnesses stages of development and their potentials through attentive observation. We find the same sense of intimacy and responsibility applied both to kin and collective alike, taking care of whatever subject she chooses.

Whether abstract or figurative, there is this sense of intimacy, curiosity, and awe in each work as she explores different aspects of our humanness. The love of her subjects and of seeing and understanding are omnipresent, and, above all, there is an overwhelming sense of care. This is the core of Conrad’s work – an ability to mother; to pay attention to, to understand, to soothe, and help grow. Most importantly, it is Conrad’s work to see.

Calder Anderson is a writer and artist living in Oakland, California. Her interest lies in the intersection of psychology and art as well as consciousness and spirituality. She is well-versed in the fine art world, previously holding positions at Hosfelt Gallery and Pace Gallery in Palo Alto.

In a world of glowy things and trash, there is humor and identity

In physics, the observer effect describes the disturbance of a system by the act of observation. Artists manifest this effect through their work, by transforming the meaning of objects and in doing so recalibrating the signifiers of the system they inhabit.

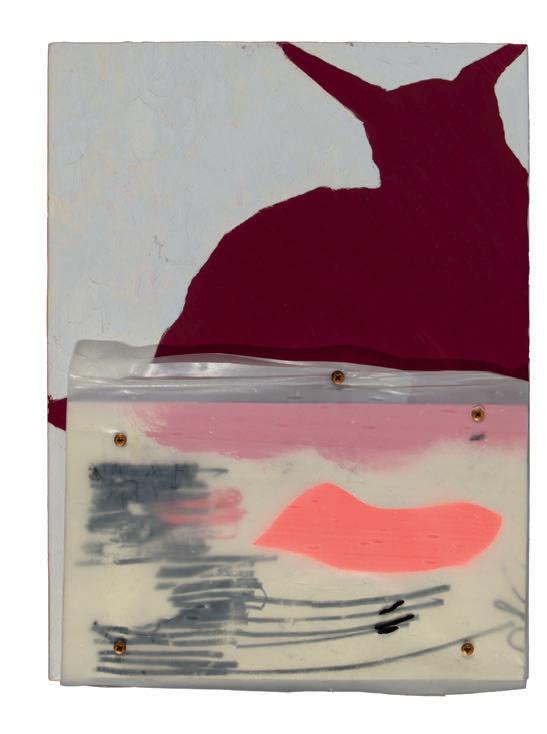

Mary Fernando Conrad illuminates the combinatorial valences stored within the vernacular materials that constitute our everyday experiences of the world. Through this career-long exploration, Conrad provokes the viewer to reconsider their understanding of the relationship between the mundane and the profound, the act of making and the clarity of seeing. At the core, Conrad’s art impels the transmutation of meaning, as the observer enters into a dialogue with the observed and resets the system they both occupy.

Mary Fernando Conrad draws upon her lived experiences as a working artist, a trained architect, a systems thinker, and a transnational diasporic (im)migrant woman to shape her practice. She is an investigator and connector of cultures, places of origin, structural hierarchies, and insights shaped by her unique perspective to deconstruct the relationship between objects and the meanings they signify. Through her inquiry, she calls into question the perceived permanence of constructed materials and draws significance from the implications of their ephemerality. What emerges is an appreciation for the unexpected humor and subverted identity contained within them.

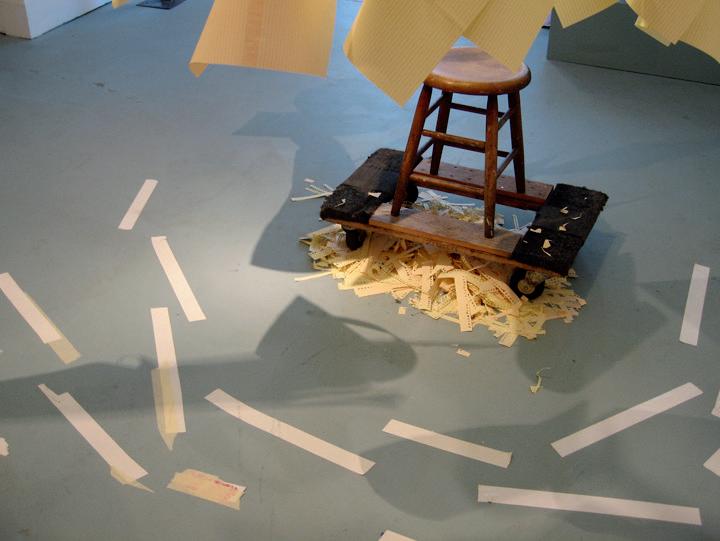

Conrad elucidates the latent meanings that attend to the physical forms of the commonplace. In her work, we are made to see the ways that shape, structure and time interplay to suggest metaphorical states, suggestive of states and places of passage and solitude. The external forms of everyday materials, when combined, create a language that subverts the viewer’s expectations. Objects once valued for the acquisition of experience deliver a considered experience of acquisition.

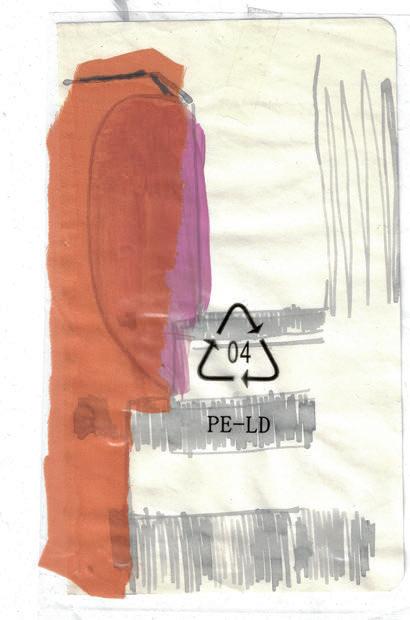

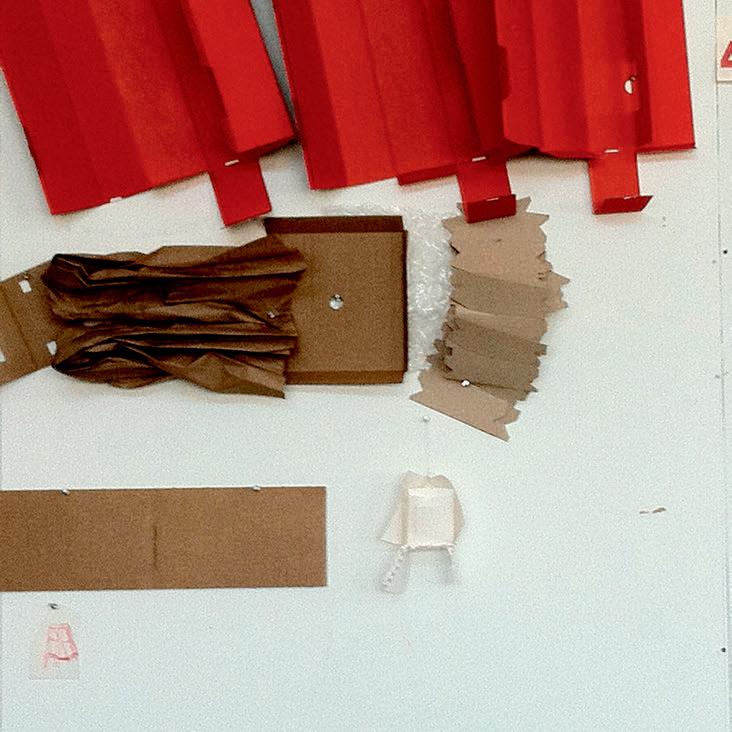

Working with familiar materials such as plastic sheeting, polystyrene packaging, cardboard, and neon signage, Conrad elevates what would otherwise be seen as merely the detritus of modern society into new constructs that carry a striking beauty all their own. It is an aesthetic transformation of that which is so readily overlooked in our material culture, that reminds us of the latent potential in even the most humble object to engender pause, reflection, and the realization of new meanings.

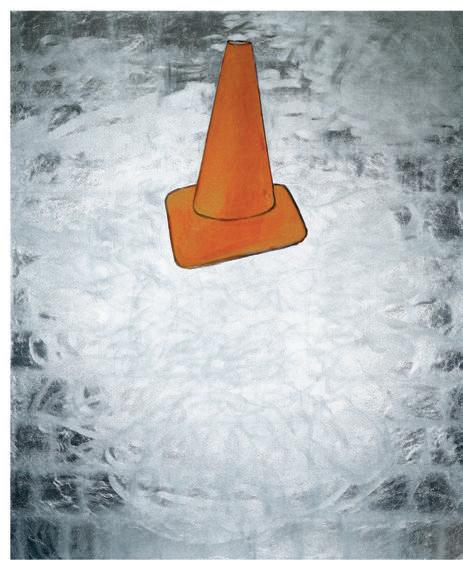

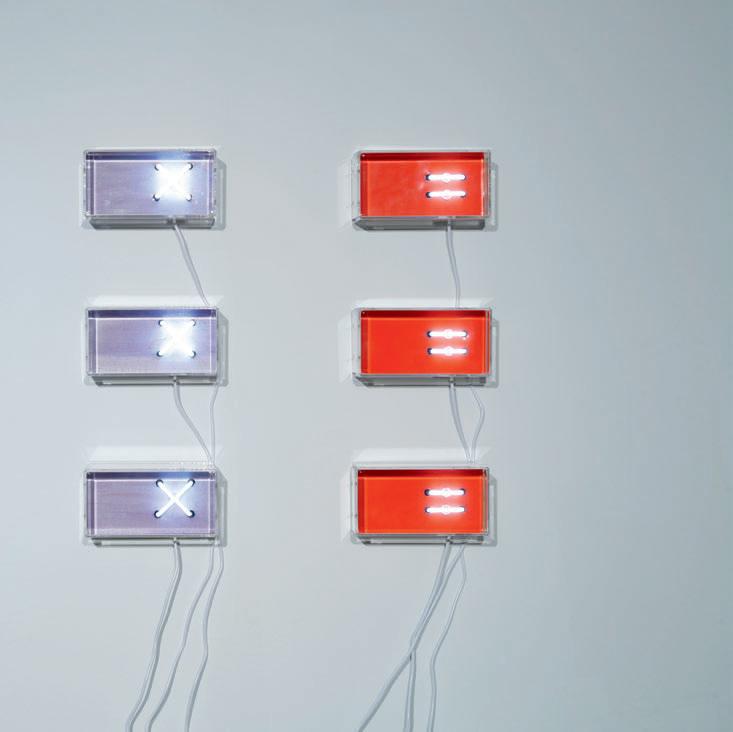

The large-scale works Ground Control, Common Carrier, Vapor Trail, and Airport Hotel (2011) combine plastic containers and found objects, backlit to emit an ethereal glow, which suggests organic connections even as they suggest the presence of artifacts from another civilization. Array, Drastic Plastic, and Sunrise Sunset (2009) are smaller-scale electric works in which neon bricks emanate an artificial light that signifies coded communications from a society wholly given over to the embrace of technology. In the painting Violet Float (2009), Conrad represents an orange traffic cone rendered above a violet background, delineating the absence of man and transmitting what is perhaps a warning of the illusion of activity and progress.

Mary Conrad’s body of work invites us to reconsider our relationship to the manufactured world and to see again with fresh eyes the layers of meaning that imbue even that which would normally be discarded. Through her provocative,

nuanced, and formally challenging creations, Conrad introduces concepts of decay, renewal, inner travel, and outer manifestations of a world where the observer and observed intersect in emergent systems of culture.

***

Katya Min worked with Mary Conrad on her solo exhibit Immaterial, (October 6th - November 18th, 2011) as the curator and director of IcTus Projects, an experimental gallery space in the Mission district SF.

The exhibition comprised of a series of large-scale mixed media installations, small- and large-scale sculptures, neon signage, and drawings, including acrylic-covered boxes, drawings, and sewn plastic sheeting. Against the gallery’s back wall, four striking, amorphous assemblages, Ground Control, Common Carrier, Vapor Trail, and Airport Hotel (all work 2011), were backlit to reveal contents that seemed to glow under the light. Drayage and Palette, two drawings on paper, reiterated those organic shapes and vivid colors, and Wheres, a grid of small acrylic boxes filled with wood, plaster, and string, Conrad provoked the viewer to take a closer, more inquisitive look at the social edifices surrounding us. Conrad suggested that an understanding of a world of pre-packaged alarm and debris can only come from an inquiry into that which is so familiar as to be ignored.

Excerpt from Immaterial curatorial statement:

“What would have been incomprehensible marvels to past generations, we now absorb, process and ignore as we move ever faster through the culmination of this digital age. With each season the waves lap higher and the tides scatter these temporary edifices erected so purposefully a minute ago. It is the irony of living in a world where mass production dominates that what has become most disposable is our attention.

Mary Fernando Conrad reconnoiters the spaces between making and seeing, in the context of this tension between the signifiers of our systems and we who populate them. By focusing our attention on the meaning carried within even the everyday objects -- mundane, glorious, shifting points of civilization -- Conrad restores the gift of consciousness. A salve and a shield, tools to materialize the dreams ahead.”

***

Katya Min is an independent curator based in the Bay Area and currently is the co-director of SEE(d) Artists Series, which cultivates connections and meaningful exchanges between artists and arts supporters. Min was the Curator of Public Programs at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (YBCA) from 2011 to 2018. Katya has led a range of programs, including the social context exhibition series for emerging Bay Area artists in the Room for Big Ideas (2012-2016); the monthly Converge series; a presentations of participatory workshops, social installations, and performative art, and YBCA Arts & Ideas Festivals, and other public programs related to YBCA’s visual arts exhibitions.

I was interested in packaging. When Katya Min visited my studio in the shipyard in 2010, I had drawings on plastic sheeting as art work on the wall. I had a multi-colored packaging display pinned to the wall. Packaging is the part not needed to make sure that the thing that was desired makes it to where it’s going. Art handlers wrap artworks in plastic and bubble wrap. I’m interested in packaging and also garbage: what is not needed by me, by a society. In the time between when Katya Min came to see me and the show, I had made what I still consider some of my best work: sewn plastic sheeting backlit by sign-makers plastic. The sign-makers’ plastic was 4 feet by 8 feet — the size of a sheet of plywood — and the sewn pieces were like dry cleaner bags or medical X-rays so that the effect was somewhat retail since the gallery was a store. The aesthetic has been described as the shadow thrown by a glass coffee table which I like since I’m interested in derivatives (in the calculus or mathematical sense). I had Phil the carpenter build the wood structure that held the sign-makers plastic.

I became interested in human codification, in the human search for meaning.

Sketch, 2010, porcelain, fabric, plastic sheeting, embroidery thread, Canaletto reproduction from the Norton Simon Museum, Sharpie, cold storage mailer, 10 x 8 inches

Sketch, 2010, porcelain, fabric, plastic sheeting, embroidery thread, Canaletto reproduction from the Norton Simon Museum, Sharpie, cold storage mailer, 10 x 8 inches

Sketch, 2010, cardboard, vegetable elastics, fabric, Canaletto reproduction from the Norton Simon Museum, cold storage silvered cardboard. 9 ¾ x 7 ½ inches

Sketch, 2010, cardboard, vegetable elastics, fabric, Canaletto reproduction from the Norton Simon Museum, cold storage silvered cardboard. 9 ¾ x 7 ½ inches

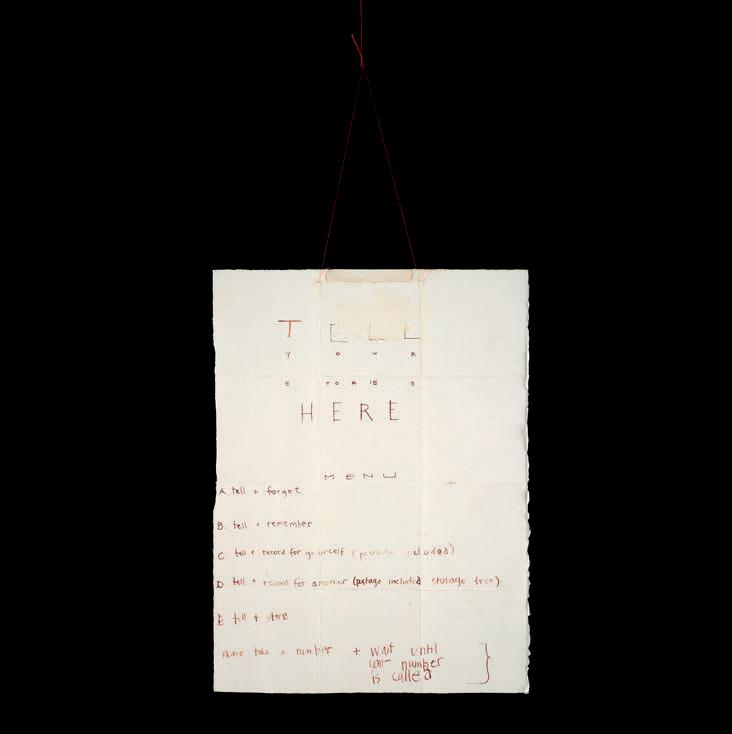

Laurie Lazer and Darryl Smith gave me my first show. I would pick Laurie up and we’d go to breakfast and it was always the most amazing conversation. We’d go to Hayes Valley and sit outside. You could eat well and it was affordable. They gave me a show at 509 Ellis/ Luggage Store Annex that has now become Little Swim Gallery. It was a storefront, with a backdoor to the community garden they’d created, the Tenderloin National Forest. I made a forest of stories that you walked through - driver’s licenses and job applications are a kind of story you tell about yourself. I used the furniture I found on the site to make a reading area and an interrogation stool of received knowledge; a picnic table in the middle of the store to be the history we all make as we chat. And finally, toward the back of the store, giving out on to the community garden, was an open mike and I would invite people from the community to say what they had to say. Over the open mike was a pink neon sign made by Amy Palms at Neonworks that said “Tell Your Stories Here”. The show was called “Sell Your Stories Here” and usually neon, brought into art by Bruce Nauman, is the language of commerce. The Luggage Store Gallery acquired it, showed it in their 20th Anniversary Show and later sold it to an owner of Twitter. His wife was one of my earliest supporters.

We went to Maine with the kids the summer after my dad died, to see my father’s sister. Driving around there, you could either see the road or the forest but not both. The road or the view.

Actuarial tables list $100 for each finger lost, and $500 for a thumb. $2500 if it’s both thumbs. But what if it’s your thumb. The notion of fungibility is that one thing is like another for the purposes of exchange. One bag of wheat is like another, and so you can trade in wheat. Hence the Halle de Blé. Where is the limit in our society?

It’s still an issue in which I am deeply interested. At the time, I became interested in the fungibility of land: things that are fungible, and things that are not, like family members, like the story you tell yourself about who you are.

I became interested in traffic cones as being a proto-alphabetical sign of alarm and of government.

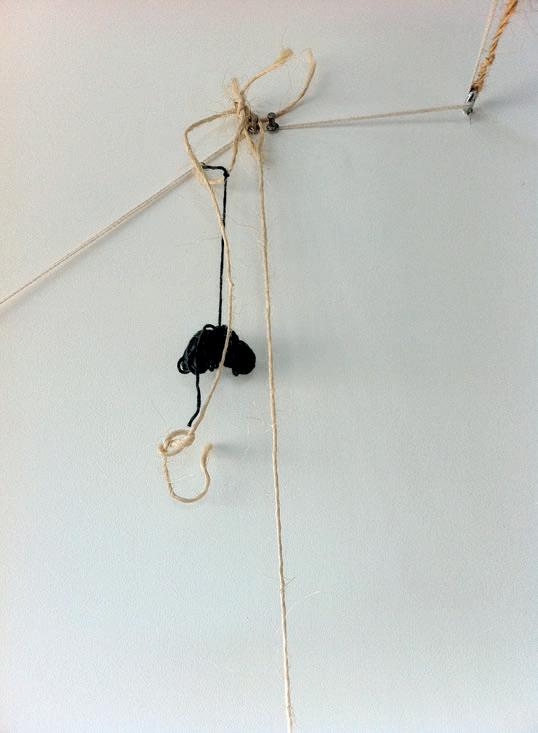

Lapidary Terrarium, 2009, twine, tape, plastic sheeting, bicycle wheel, dimensions variable

Studio View, Hunter’s Point, CA, 2008

Lapidary Terrarium, 2009, twine, tape, plastic sheeting, bicycle wheel, dimensions variable

Studio View, Hunter’s Point, CA, 2008

I was interested in private language and public language.

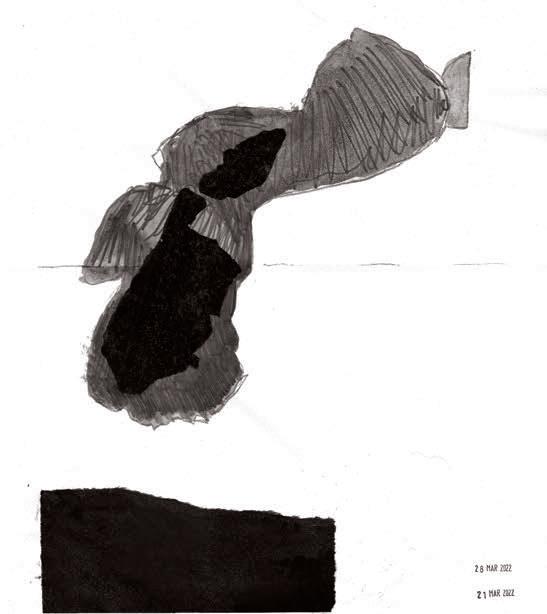

(Here) = (Now) Study I, 2009, pencil, paper, gouache on watercolor paper, 10 x 5 inches

(Here) = (Now) Study I, 2009, pencil, paper, gouache on watercolor paper, 10 x 5 inches

(Here) = (Now) Study IX, 2009, pencil, paper, gouache on watercolor paper, 10 x 5 inches

(Here) = (Now) Study IX, 2009, pencil, paper, gouache on watercolor paper, 10 x 5 inches

I think of a tag or graffiti as writing or a sign saying ‘I am here.’

I had the paper; I had the charcoal and I made these all at once, in a rush.

Studio View, Hunter’s Point, CA, 2010

Studio View, Hunter’s Point, CA, 2010

Studio View, Hunter’s Point, CA, 2010

Studio View, Hunter’s Point, CA, 2010

I won. & because I won, I am right.

I am stronger (it goes without saying, since I won) (Did I tell you I won?) So I dictate the rules, how things get done, who is in charge.

I won the civil war. I won the vote. I won the argument.

You are wrong. You are not right. You tried to win against me & You lost.

So now, I have to be careful of you. You need to be managed & I have to keep my eye on you.

06 Nov 2020

© marfeco 2020

Don’t go to jail in the summer

Lazy grape shadows drape Onto the ground.

Pulsing and buzzing, drifting and drowsing Tiny violences or minor transgressions Deep cold dank spaces under the house Can wait.

Don’t go to jail in the springtime

If you don’t pay attention One day it’s all sticks and stones And the next it’s pale green. It skips right by you if you miss it And suddenly that hot blue plate Flattens into white and you’ve got to wear it.

And don’t give me that crap about winter Just stay with me here

And we can watch movies on the computer and sleep a lot. Clothes are bigger and we can eat too And even if we aren’t sleeping, we don’t have to do Anything.

21 July 2019

© marfeco 2022Title-less Spotted and piebald together I hide Under the sofa And dream of the tides That will carry away Spoils and toils - carry away the loaded weight.

Root vegetables rotting Summer fruits spent Fishheads silvered with Fur, the glistening is glorious the future Is furious, show me Show me the shore.

It is my hope that nothing occurs 100% and that my best chance of being the .001% that is unaffected or improved by a changing climate is a deep understanding of the land where I am. I garden.

Consider the barber, the body, waxing, shaving. Consider toileting habits, grooming habits, aesthetically choosing yourself: you are choosing the environment and you are gardening. Consider your body a landscape.

Exercise is a grey zone because it is also in the mind. Sports Psychology.

What to plant, when to plant. The California Floristic Province, bay area natives, Point Reyes natives; nurseries; many plants cannot be purchased at nurseries. Consider the restoration garden as described by Judith Larner Lowry, the Bradford sisters and M. Kat Andersen.

Archaeology is a grey zone because it is also in the imagination. Fire Prevention.

So much of what is planted takes its final shape in the future. Does what is planted conserve water in a way that protects the land in the future? Does all land, all the earth over, change in the same way?

The future is a grey zone because it is also in the mind and in the imagination.

Every decision about what to plant and when to mow is made based on the capacity of the land to hold and keep water. Because life needs water on our planet (elsewhere, I don’t know). What does life want? Life wants more life. In the garden you decide between life and death. I wanted a garden that would feed the soil, feed something. It’s not about feeding me-that was too inconvenient and what? I might end up with kale and an apple; salad herbs. But I could be a force for good in the garden, I could feed the soil, feed the land, feed the flora and fauna. I could have what Judith Larner Lowry calls a restoration garden. I learned a lot about plants and gardens and soil. My list of sources included local arboretums, native plant societies and their nurseries. There is quite a lot written about the California Floristic Province but there are plants from the Bay Area and even plants that only occur in Point Reyes. I strongly favored the Point Reyes natives where I could.

The climate is changing. That’s a gardening fact.

Can some areas “get better” while others get “worse”?

For example, can the the Inverness Ridge become a rainforest?

As the world gets hotter, does it also get dryer? Where does that water go? How is water attracted? Water is ‘social’; water is attracted to the existence of water (water is hydrophilic - think about leaks).

We know that plants form communities — Why? What are they giving each other that can support our goals? PH? For example —do native plant communities tend to more basic soils (serpentine), whereas non-native have learned to thrive in more acidic soils and thus are more able to thrive with pollution.

We know that certain plants use a (slightly) more powerful form of photosynthesis. These plants include English Ivy. Is there less English ivy in 2021 because of the initial impact of covid (changed human activity) on the environment?

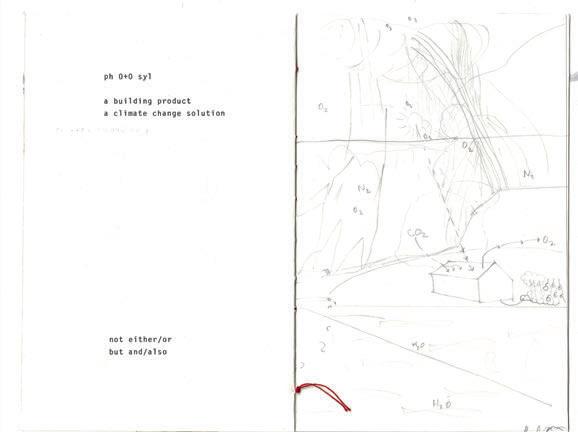

And what about artificial photosynthesis? Terra-forming and pulling CO2 out of the air?

CO2 only exists as less than 1% of the air (it’s 78% Nitrogen and 20 or so % Oxygen -The question isn’t ‘is this a hoax’ (can 1% be impacting us this way) but why CO2 is the homeostatic mechanism.

My garden began with three tryings from the work of four women: From the Bradbury sisters in Australia, who weeded the wild, the trying that things can improve where I am.

From Judith Larner Lowry, who researched the plants and ecology of the place that she was, the trying that place can be made, and I can live in that place.

From M. Kat Anderson, whose response to John Muir saying “oh, California is like a garden” was “it IS a garden – it’s been gardened by the original peoples” the trying that human wisdom exists and I can learn from it.

The existing buildings had an ambition to architecture. The sub-authors of Christopher Alexander’s book, A Pattern Language, had built the building and we were the fourth owners. As this was one of the first buildings the architects had built out of school, it had the usual student mistakes. It was considered as a volume, but not as a space. It had an excellent entry sequence, and looked great from the street, but then it petered out. There were also problems associated with the building being postmodern, modern being “a machine for living.” Post-modern is a point of view where the inhabitants drive the design. The people for whom it had been built, were recluses and had horses. They didn’t seem to want to go outside. The only guest room was hard by the front door as if to say, if you need to leave in the middle of the night, and without saying goodbye, it’s ok with us. There were only two ways of getting out of the building: the front door and the solid wood kitchen door. The windows were small and idiosyncratic. It was like being in the belly of a whale.

We lived differently than them. We wanted friends and family to visit and if you couldn’t go hide in your room, then you couldn’t be part of the party. We wanted the inside to be on a continuum with the outside and I was a gardener. We wanted the house to participate in the big views, so we wanted to change the windows. Yes it was still a nudie colony, but that now meant outdoor bathrooms where you could experience your body in a different way than in the city. Yes the kitchen table was still the dining table, but that now meant a table for festivities as well as a work table. My husband and my dog and I stayed in the stable while the house was being worked on. Paul Discoe, an ordained Buddhist minister, turned the stable into a bedroom. Pete Humphrey, who worked on the house, taught me so much about being an artist. Pete who would say to me, “it sounds like you don’t know enough about that yet.” Or he’d say to me, ”you know what you want. So that’s what we’ll do.” Pete taught me about patience and getting it right.

“I had the opportunity to build a house for myself. When I was done, it was time to put in the hedges and I waited for the rain to plant. I waited and I waited. I waited and I panicked. I waited and I was sad.

The rain didn’t come that year. Later in the year, things began to die. The landscape changed. It was droopy, grey and barren; lost and creepy to look at, like a burnt-out house and I looked up at the solar panels. I was still mad, perplexed, and I just thought: why can’t those solar panels also take in carbon dioxide or whatever is causing this problem.

In the basement of her home-turned-studio in uptown San Francisco, Mary Fernando Conrad is pinning a thick yellow wire to an old drawer. She is getting ready for her upcoming exhibition, titled “What is Shakespeare in a time of climate change.”

Nature bats last.

At first I thought I could start-up a start-up. I know I’m not a CEO but I thought I could hire someone. This is the biggest story of our time, and we, you and I, have no say in it. There is no consumer product. So I wanted to make a consumer product.

At first I thought I could harness the power of the city. In the city where I live, the building department mandates copper pipes, seismic upgrades, even monies put aside for art if you spend enough. And cities have competences — they have water treatment plants and airports. You have gas and water piped into your house or apartment, and sewage goes out. What about carbon dioxide? Isn’t it just another waste product?

If CO2 was causing all this mayhem, how about removing CO2? Photosynthesis absorbs CO2 from the air. Photosynthesis is how plants grow, and it forms the basis of all non-vegetal life. It’s a very simple equation: 6CO2 + 6H2O = C6H12O6 + 6O2. Could we have a form of artificial photosynthesis?

Over time, when I could not get anyone interested in the ideas, it changed me. This was not the solution anyone was looking for: the world had other crises and didn’t have time to take this one seriously. Climate change as a concept was not even taken seriously by our government.

Now I am hoping that what I call “radical localism” will allow me and mine to survive. I don’t know about you and yours anymore. Some days this is a very serious business. Other days are other days.

The Met was entire education: the Impressionist rooms, the medieval rooms, museums in New York The Frick, The Moma, The Whitney, The Morgan Library 1980-83

Einstein at the Beach, down the street, & that I didn’t see1984

Velasquez at the Met 1989

Basquiat at the Whitney 1994

Velasquez at the Prado, 1995

Lee Bontecue in LA 2003

Rauschenberg at the Met 2008

The Tony Feher that I bought and look at 2012

The Gabriel Orozco that I bought and look at 2022

The Tauba Auerbach that I bought for Tony and look at, 2012

The Jim Campbell that Tony bought and I look at,1997

One moment you don’t know the work, and then the next instant, your whole life has changed.

Albert Blankert, Vermeer of Delft, Phaidon Oxford, 1978 1979, New York

Abrams, et all, Norton Anthology of English Literature Volume Two, Norton New York 1978 1980, New York

FM Godfrey, Italian Architecture Up To 1750, Alec Trianti London, 1971 1983, New York

Marcia Tucker et al., Art After Modernism Rethinking Representation, Godine Boston, 1984 1984 New York

Michael Doran, Conversations with Cezanne, UC Press, Berkeley, 2001 1984, New York

Frank Lloyd Wright, Drawings and Plans of Frank Lloyd Wright The Early Period 1983-1909, Dover Publications, Inc New York, 1983 1985, Massachusetts

Paul Letarouilly, Edifices de Rome Modernes, Princeton Architectural Press, Princeton, 1982 1986, Massachusetts

Le Corbusier et P. Jeanneret, Le Corbusier 1929-1934, Les Editions d’Architecture, Zurich 1964 1986 New York

William Seitz, The Art of Assemblage, Museum of Modern Art 1961 1987, New York

Barbara Rose, Rauschenberg, Vintage Contemporary Artists Originals New York, 1987 1988, New York

Peter Schjedahl, David Salle, Vintage Contemporary Artists Originals, New York, 1987 1988 New York

MOCA Chicago, Gordon Matta-Clark, A Retrospective, MOCA Chicago, 1985 1988, New York

Robert Tucker, The Marx-Engels Reader, W.W. Norton New York London, 1978 1988, New York

Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture A Critical History, Thames and Hudson London, 1985 1989 New York

Boesiger and Girsberger, Le Corbusier 1910-1965, Les Editions d’Architecture, Zurich 1986 1988 New York

Wulf Herzogenrath, Bauhaus 50 Years, Royal Academy of Arts London, 1968 1989 New York

Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass, Penguin Books New York London Toronto 1989 New York

Wallace Stevens, The Collected Poems, First Vintage Books Edition, 1982 1989 New York

Jacques Lucan, OMA - Rem Koolhaas, Electra Moniteur, Milan Paris, 1990 1990 New York

Christian de Portzamparc, Urban Situations, AD Galerie Ma New York 1991 1991 Paris

Maria Glisson Marcel Broodthaers, Moi Aussi Je me suis demandé si ne ne pouvais vendre quelque chase et réussir dans la vie, editions Jeu de Paume, 1991

1993 Jakarta

Jonathan Brown, Velasquez, Painter and Courtier, Yale University Press,

New Haven and London, 1986 1993 Jakarta

Elizabeth Sussman, On the Passage of a few people through a rather brief moment in time: The Situationist International 1957-1972, MIT Press Cambridge London, 1990 1993 Jakarta

John Elderfield, Matisse: A Retrospective, Moma New York, 1992 1994 Jakarta

D’Harnoncourt and McShine, Marcel Duchamp LHOOQ, Prestel 1989 1998, San Francisco

Meyer Schapiro, Cézanne, Harry N Abrams New York, 1998 1998 San Francisco

Ludman, Joan, Fairfield Porter: A catalogue raisonnée of Paintings, Watercolors and Pastels, Hudson Hills Press, New York, 2001 2003 San Francisco

Robert Smithson, Le Paysage Entropique 1960-1973, Musées de MarseillesRéunion des musées nationaux, 1994 2005, San Francisco

Tony Godfrey, Conceptual Art, Phaidon London, 1998 2006, San Francisco

Paul Schimmel, Robert Rauschenberg Combines, MOCA Steidl Los Angeles, 2005 2006 San Francisco

Jane Livingston, The Paintings of Joan Mitchell, Whitney, Abrams UC, Berkeley 2002 2007 San Francisco

Yves-Alain Bois, Robert Rauschenberg Cardboards and Related Pieces, Yale University Press New Haven London, 2007 2007 San Francisco

Aaron Rose, Beautiful Losers, DAP Iconoclast, 2004 2007 San Francisco

Norden, Danto, Sarah Sze, Abrams New York, 2007 2008, San Francisco

Wendy Weitman, Books Prints and Things Kiki Smith, Moma New York, 2004 2008, San Francisco

Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto, A Norton Critical Edition New York, 1988 2009 San Francisco

Dr. Theodore Kacynski, Industrial Society and It’s Future, Self-Published/ Amazon Seattle, 1995 2009, San Francisco

Kunstmuseum Bern, Deep Blues Bill Traylor 1854-1948 Yale University Press New Haven, 2004 2013 San Francisco

Bill Traylor Drawings from the High Museum of Art, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts 2013 San Francisco

Peter Benson, Philip Guston Roma, Hatje Cantz Ostfildern, 2010 2014 San Francisco

James Gleick, The Information, Pantheon Books New York, 2011 2019 San Francisco

Patricia Phillips, Mierle Laderman Ukeles Maintenance Art, Prestel Munich London, 2016 2019 San Francisco

Max Haiven, Art After Money, Money After Art, Pluto Press London, 2018 2020, San Francisco

Allan Kaprow, Assemblages Environments, Happenings, Abrams New York, 1961 2021 San Francisco

The practice…is a continual frustration, but the study is a constant delight.

My husband Tony

My kids Harry & Xa

My dogs: Dodo, Nabuko and Ibbi (ok, so they are not people)

Gale Pryor, Diana Kellogg, Lindy Roy Lee Ann Daly, Vivian Walsh, Judy Bernhard I love you.

When Masako Miki came to my studio on 46th ave and said there’s so much talent here.

When Ann Hatch came to my studio in the shipyard and she was central to it all.

When Clare Rojas came to my studio and said no one ever has to visit your studio, you know.

Barry McGee who believed in me.

Laurie and Darryl who also believed in me.

Robert McCarter, who was the first time I felt believed in.

Pete Humphrey who believed in me.

Rufus Blunk who knew what I was talking about.

Ken Frampton and Silvia Kolbowski who were inspiring

Dustin Fosnot who is also an artist.

Katya Min, ‘who is fiery’ said Phil the carpenter, and who believed in me.

Larry Rinder who believed in me.

Phil Black and Brigitte Sandquist who believed in me.

Elliott Barnes, Meiling and Francois, Anne Steichen

Peter & Natasha Rive

Sabrina Buell

Marialidia Marcotulli aka Mollie aka Doc Mols

One moment you don’t know that person, and then the next instant, your life has changed.

Many people believe that in this age, art is dead…Artists themselves are beginning to lose their confidence. They don’t know whether they’re doing something that still has value in this day and age where social problems are so vital and critical. I wondered myself about this. Why am I still an artist?

Creating is just as simple and artless a thing to do as destroying. Everyone on the earth has creativity… The job of an artist is not to destroy, but to change the value of things. And by doing that, artists/the artist can change the world…

…Artist’s revalue.

Y.O. Cannes Film Festival

From: This is Not Here Exh. cat.,

Reprinted Yoko Ono, The Museum of Modern (F)art, New York 1971

From pages 62-65 and adapted.

Yoko Ono

This Room Moves at the Same Speed as the Clouds Exhibition Catalogue, Kunsthaus Zurich 4 March - 29 May 2022

1961 B. Baltimore Maryland USA

1965 Goes to kindergarten in New Rochelle, New York

1966 Moves to Ceylon

1972 Returns to USA

1979 Attends Cornell University as a Biology Student

1983 Graduates Cornell University B. A. English Literature cum laude. Moves to New York

1984 Attends GSD, Harvard University

1987 Attends GSAPP Columbia University

1990 Graduates GSAPP M. Arch Awarded Kinne Traveling Scholarship to study Carlo Scarpa

1991 Meet Tony Conrad, Works for Christian de Portzamparc

1992 Marries Tony Conrad

1993 Works for Architecture Studio on the European Parliament at Strasbourg, Moves to Indonesia

1994 Harry is born

1996 Xa is born

1997 Moves to San Francisco

2001 Takes Painting class at SFAI

2002 Studio in the Shipyard

2004 Renovates Sixth Ave

2005 Joins Southern Exposure Board under Courtney Fink

2007 Sell Your Stories Here 509 Ellis/ Luggage Store Annex, San Francisco

2008 Fungible Michael Rosenthal Gallery, San Francisco

2009 Lapidary Terrarium Michael Rosenthal Gallery San Francisco

2011 Immaterial Ictus Gallery, San Francisco

2012 Moves Studio to 702 Earl Street

2014 Joins Board of Berkeley Art Museum Pacific Film Archives under Larry Rinder

2015 Rebuilds Drakes Summit Road house

2016 Becomes interested in climate change

2017 Moves studio to 879 46th Avenue

2018 What is Shakespeare in a Time of Climate Change, Great Highway Gallery, San Francisco

2019 Moves studio to 48 Cook Street

2020 Covid. Works at Drakes Summit Road

2021 Violet and Ochre and There are Two of Them, Gospel Flats Farmstand Gallery, Bolinas

2022 (*) making a book

Shirlee Muriel Levin Lang went to the Chicago Art Institute to hear Allan Kaprow speak.

There were three people at a big table on the stage discussing the Happening. What is a Happening? Allan Kaprow was asked too. He answered by hoisting a heavy suitcase from his side onto the table and he opened it, spilling the contents into the audience.

Shirlee came home and told her son, Richard. She said someone in the audience said,” Allan Kaprow has lost his marbles.”

Richard said to me, “my gift to you is that image of marbles everywhere, in your head.”

It is also my gift to you.

Thank you to my husband and to my kids. Thank you to Doc Mols & Calder, without whom this book is not possible.

Thank you to my stardust friend (the one who prefers to be outside the milky way, which means being in another galaxy all together, when near can be found in the space of Leo above the gravitational pull).

credits

Design: Fernanda Steinmann Studio

Fonts: Helvetica Neue and Letter Gothic Std

Printing: Edition One, Richmond, CA

Photography: Alex Artz, John Wilson White, David W. Anderson, Almac

First Edition 50 copies

ISBN 979-8-88831-610-8

© marfeco 2022. All rights reserved.