MARTUMILI ARTISTS

Martu are the traditional owners of a large part of the remote western desert region of Western Australia. Their ancestral land includes much of the Great Sandy, Little Sandy and Gibson Deserts as well as the Karlamilyi National Park. Across their Country, Martu share common languages, law and culture.

Presented by

Proudly supported by

For artwork sales and enquiries, please contact mmasales@eastpilbara.wa.gov.au or visit www.martumili.com.au

The words kujungka and kujungkarrini hold a special place in the heart of the Martu community. Kujungka means ‘as one’ or ‘together,’ while kujungkarrini reflects the actions of coming together in unity.

These powerful concepts also frame how the Martu want to collaborate with non-Martu people; Martu aim to develop partnerships founded on mutual respect, understanding, and equality. They want to work side by side as equals, blending unique skills and learning from one another.

Martumili Artists and Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa are both organisations that work with and for Martu, each playing an important role in different but complementary areas. Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa runs cultural, environmental, and social programs essential for preserving Martu traditions and knowledge, protecting the environment, and addressing social issues. Martumili focuses on cultivating the artistic talents of the Martu people, ensuring their rich artistic and cultural heritage is showcased and appreciated both locally and globally.

A future grounded in a strong cultural identity and continued connection to Country is essential for Martu people. Through their joint efforts, Martumili and Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa ensure that Martu culture, knowledge, and connection to Country are not only preserved but also celebrated and integrated into everyday life.

Kujungka is the third exhibition in the Martumili and Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa joint project Warrarnku Ninti (knowledge of Country), following Mirrka (2023) and Waru (2022), and features a soundscape created from Tura and Martumili’s Kulininpalaju project. Culminating as a series of theme-based arts and cultural bush camps with distinct exhibition outcomes, this partnership gives future generations the chance to engage with nuanced Martu knowledge systems through new artistic mediums with pride, knowledge, and confidence.

Artwork sales and enquiries

Please contact mmasales@eastpilbara.wa.gov.au or visit the website www.martumili.com.au

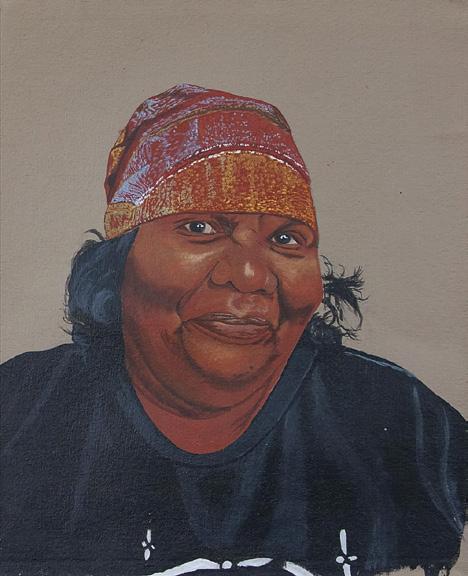

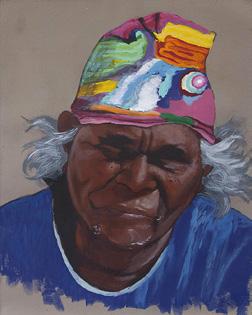

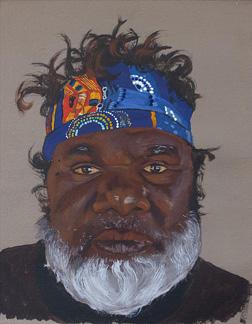

[3] Owen John Biljabu, Judith Anya Samson, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 36 x 46 cm, 24-517

[4] Kathleen Maree Sorensen, Lunki (witchetty grub), 2024, acrylic on canvas, 91 x 91 cm, 24-200

[7] May Mayiwalku (May Wokka) Chapman, Mukunyjarra, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 30 x 30cm, 23-1085

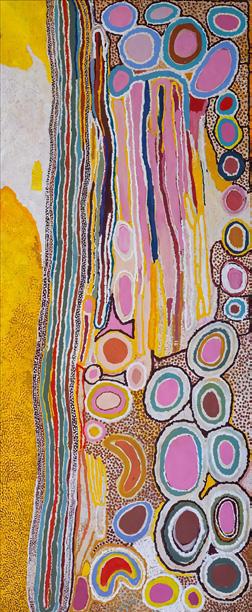

[1] Jakayu Biljabu (dec.) and Gladys Kuru Bidu, Untitled, 2022, acrylic on linen, 124 x 298 cm, 22-1681

[2] Noreena Kadibil, Sandalwood tree and Bush Medicine, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 46 x 61 cm, 24-468

[3] Roxanne Anderson, Untitled, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 61 x 91 cm, 24-431

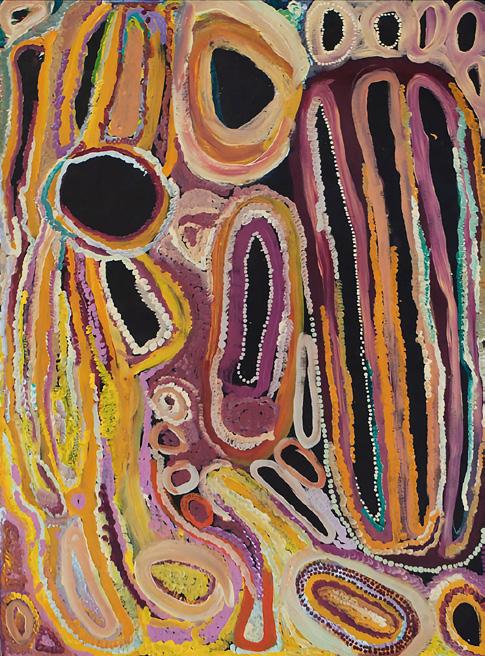

[4] Bugai Whyoulter, Wantili (Warntili, Canning Stock Route Well 25), 2023, acrylic on linen, 200 x 300cm, 23-205

[5] Nancy Nyanjilpayi (Ngarnjapayi) Chapman and Mayika Chapman, Nyayartakujarra (Ngayarta Kujarra, Lake Dora), 2023, acrylic on canvas, 76 x 121 cm, 23-288

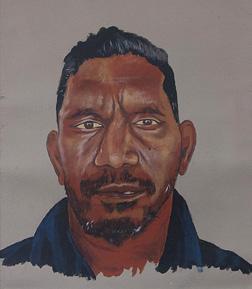

[6] Owen John Biljabu, Cyril Whyoulter, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 36 x 46 cm, 24-516

[7] Lily Jatarr Long, Untitled, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 30 x 30cm, 24-144

“ We would walk together, hunting as we went.” Yikartu Bumba

During the pujiman (traditional, desert dwelling) era, Martu traversed large distances annually in small, kin-based bands. Movement through their territorial areas by foot was dictated by seasonal changes and cultural obligations, staged from water source to water source, and sustained by hunting and gathering bush tucker. Typically, groups would travel together for a time before arranging to meet further along at another camp site. When they arrived at the meeting place, they would light a large waru (fire) to signal their location. In this way, intimate familial and social connections were maintained across the vast Western Desert.

In the extremely harsh desert environment, survival depended on working kujungka (all together as one) to share knowledge of and physically maintain Country. Intimate knowledge of the physical and cultural properties of one’s ngurra (home Country, camp), along with the responsibility to care for it, was passed down over generations through experience and in Jukurrpa (Dreamtime) narratives as communicated in ceremony, dance, song, and art.

The Martu structure and function of walytja (family) is perhaps the clearest manifestation of the Martu concept of kujungka (all together as one). The Martu four-section kinship system, established by the Jukurrpa (Dreaming) ancestors, determines a person’s belonging to either the Purungu, Milangka, Panaka or Karrimarra skin group. This system not only defines relationships but also establishes a framework for expectations and obligations, extending the importance of family far beyond blood or marriage ties. Family encompasses all relationships within the community, forming a network crucial to survival during the pujiman (traditional, desert dwelling) era that remains fundamental in every aspect of Martu life today.

[1] Elizabeth Toby, Waterhole, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 30 x 30 cm, 231088

[2] Sylvia Wilson, Wilson Sisters, 2023, acrylic on linen, 91 x 91 cm, 23-944

[3] Azaniah Burton, Wirlarra (Wilarra), 2024, acrylic on canvas, 46 x 36 cm, 24-448

[4] Owen John Biljabu, Clifton Girgiba, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 36 x 46 cm, 24-519

[5] Nola Ngalangka Taylor and Jenny Butt, Mirrka season, 2023, acrylic on linen, 76 x 122 cm, 23-972a

[6] Gladys Kuru Bidu, Minyarra/Jaliirpa/ Jurnta (Bush Onion), 2024, acrylic on linen, 30 x 30 cm, 24-410

[7] Natasha Williams, Bush Tucker and Wild Flowers, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 91 x 121 cm, 24-420

[8] Muuki Taylor, Kulyakartu, 2023, acrylic on Belle Arti Gesso panel, 50cm x 60cm, 24-473

“ Young and old gotta do ‘im together. Old people gotta learn the young fellas about that place, Country. Martumili (belonging to Martu).” Wokka Taylor (dec.)

Binding Martu kujungka (all together as one) by the very definition of the group is the Country which they share. They are the traditional owners of the land stretching from the Great Sandy Desert in the north to Wiluna in the south. Through walytja (family), intimate knowledge of the physical and cultural properties of one’s ngurra (home Country, camp), and the responsibility to care for it is passed down over generations. This tradition continues today through land management practices such as small patch waru (fire) burning, clearing waterholes, managing invasive fauna and monitoring threatened species. All of these practices are performed as part of Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa’s (KJ) ranger activities. Ranger work is highly respected by the community as it involves caring for and maintaining connection to Country.

Jakayu Biljabu (dec.) and Corban Bamba Clause Williams, Untitled, 2021, acrylic on linen, 121 x 91 cm, 21-410

[7] Judith Anya Samson, Tuwa (sandhills) in Puntawarri, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 30 x 30 cm, 24-142

“ The old people, they sit down and paint and tell stories of the old days, and we listen and learn.” Corban Clause Williams

In Martu culture, social and cultural connectedness are symbolically expressed and strengthened through the practices of artmaking, whereby depictions of shared ngurra (home Country, camp) and Jukurrpa (Dreaming) narratives are created.

Although Martu have painted on rock walls, their bodies, and sand for millennia, acrylic painting on canvas is a relatively recent practice in the Western Desert region. Martumili Artists was established In 2006, and has since grown into one of the most recognised Aboriginal art centres in Australia. Today, many artists work in its facilities in Parnpajinya (Newman), Punmu, Parnngurr, Kunawarritji, Jigalong, Irrungadji (Nullagine), and Warralong.

The practice of collaboration lies at the core of the Martu artmaking practice. Martumili Artists are most known for their large collaborative works — but collaboration also takes place at a more fundamental level within the group. The act of painting is itself a social and cultural practice that brings people together. The senior artists pass on knowledge to the younger generation through storytelling, teaching, and mentoring. This process not only preserves important cultural information but also ensures that the younger generation remains connected to their heritage, reinforcing the Martu value of kujungka (all together as one).

[2]

[3]

[4] Owen

[5]

Written by Philip Samartzis, Sound Artist and Lead Facilitator of Kulininpalaju

Produced by Tura in partnership with Martumili Artists and supported by BHP and RMIT School of Art

The soundscape circulating within the Kujungka exhibition features a collection of recordings made with and by the communities of Parnpajinya, Jigalong, Parnngurr, Punmu, and Kunawarritji. These recordings have been collated over the past four years as part of the Kulininpalaju project, a long-term creative collaboration between Martumili Artists and Tura, which explores sound as a medium for sharing Country. Its production is informed by many conversations with people who shared knowledge, insights, and a deep curiosity about the sounds and spaces that occupy a vast stretch of land comprising one of Earth’s oldest blocks of continental crust dating back more than three billion years.

Underscoring the vivid expressions of landscapes, objects, animals and people, are sound recordings made of many of the locations represented in paint such as the springs and waterholes of Lake Dora, and the sand dunes, clay pans and spinifex that surround Punmu. Sounding across these distant places and their lively communities are the voices of excited children, troop carriers, dogs barking, and windmills and fences creaking and rattling with each gust of wind. Kujungka is the coming together of all the natural and human elements that shape the experience of space and place.

The widely distributed Martu community populates a rugged landscape comprising abundant wildlife and natural attributes shaped by extreme climate and weather. While the days are marked by the sound of human activity, the nights are eerily filled with the call of frogs and insects, and the high frequency pulse of the leaf nosed bat. At sunrise, assorted birdcall penetrates the expansive desert landscape including the wedge tail eagle, whistling kite, Australian reed warbler, spinifex pigeon, finch and little grassbird. While the vista of red sand, rocky domes, spinifex, and ghost gums suggest little has changed, the amorphous sound of heavy industry, and the succession of vehicles and trains moving across the horizon are indicators of a transformed landscape.

Kulininpalaju is a long-term creative program partnership between Tura and Martumili Artists (MMA), supported by BHP and RMIT School of Art. Tura’s ongoing programs are supported by the Australian Government through Creative Australia, its principal arts investment and advisory body and the Western Australian State Government through the Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries.

Sound is ever present and available through the materials, people and spaces that make up this beautiful place. Tracing the many sounds of the Pilbara provides a way to consider complex social and environmental dynamics and interactions in the production of new narratives and access points. Sound artists play an increasingly vital role in observing and recording the tension between climate, landscape, technology, and human action, to demonstrate the interconnectedness of things. The recordings afford audiences a chance to experience remote and remarkable places and their communities through different aesthetic forms, and immersive and affective encounters.