Tamar Saraseh

Martin A Bradley

TR Udayakumar

Eric Peris

K F Choy

Ozer Toraman

Otto Djaya

Ram Singh Urveti

Elias Yamani Ismail

Tamar Saraseh

Martin A Bradley

TR Udayakumar

Eric Peris

K F Choy

Ozer Toraman

Otto Djaya

Ram Singh Urveti

Elias Yamani Ismail

Image

Image

A quick word

Editor’s comments.

Tamar Saraseh

Indonesian artist.

Object - ivity

B/W photography by Martin A Bradley.

p46

p30 Tropical Exhibition by Singapore’s National Gallery.

p58

p80

Haunting insights

Indian artist TR Udayakumar

p90

Leaf

B/W photography by Eric Peris and K.F Choy

Nyonyah

Penang’s glorious Pinang Peranakan Mansion

p118

Preparing For Singapore Art Week

The Ocean in my Heart

Turkish artist Ozer Toraman

p154

p166

It’s 2024.

The Blue Lotus magazine is in its 13th year.

From Singapore to Malaysia, India and Indonesia, this magazine continues to cover arts and cultures across Asia.

Thank you, as always, for being here and reading this magazine. Do come back to future issues or take a look at past ones on ISSUU.

Submissions are encouraged to be sent to martinabradley@gmail.com for consideration

Take care and stay safe

Martin (Martin A Bradley, Founding Editor)

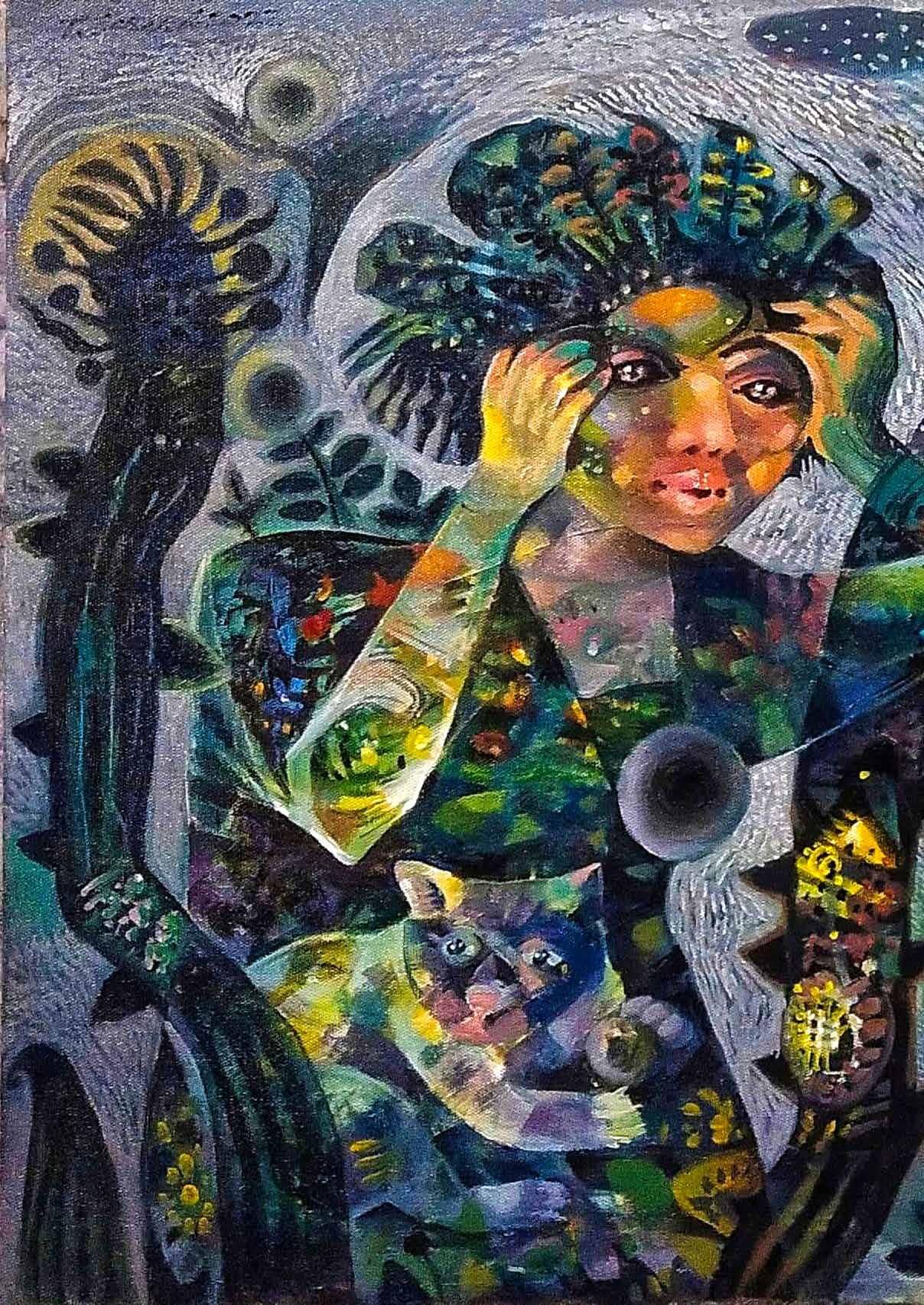

Tamar Saraseh

Tamar Saraseh

Indonesian artist Tamar Saraseh captivates us with his heavily, at times Chagal-like, symbolist imagery. Painting from Saroka village in the Saronggi District, of Sumenep Regency , in East Java Province, Indonesia, the artist reveals his creative response to life about within and without him. Of this he mentions…

“Art is part of a reflection of my gratitude for the blessings of the life that God has given me. Time and the noise of events, both physically and mentally, that take place in it are fragments of values that quietly settle in the space of intuition. These values better represent the inner side of universal human experience and are more interesting to me than highlighting purely artificial cultural forms. That is often very limited by certain demographic areas. Ideas that people might encounter in the artistic composition of my paintings are symbols of these value fragments, although of course, their meaning remains subjective.

The objects of my choice, visually, appear to experience a distortion of the normality of reality, and the background atmosphere which is sometimes illusory. This could be a reflection of my subconscious tendencies about other worlds that I experience, in relation to my daily spiritual experiences as the consequences of the concept of life flow.”

Having graduated from the Visual Art at State University of Malang (Universitas Negeri Malang) East Java, Indonesia, Tamar Saraseh uses subjects close to him and his cultural background. Painting with acrylic on canvas, his works include images of rabbits (possibly a passive principle of the cosmos, manifesting in relaxation, fluidity, calm, and contemplation), cacti (a re-occurring theme of resilience throughout his oeuvre), prayer, the cultural artefact of the ‘kris’ (a ritualistic, spiritual, and symbolic knife) and life in general, within nature, around the artist.

We are men

Admittedly influenced by the ‘Surrealism’ of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray, Bradley has created his imagery largely in Europe and Asia, over four decades.

He has put aside his heavier Canon, Minolta and ancient Pratika cameras in favour of a ‘smart phone’ camera. It is portable and easily accessibility when capturing images on the fly.

The images shown here are without the use of ‘filters’, rendered simply in black and white.

National Art Gallery Singapore

18 November 2023 – 24 March 2024

City Hall Wing, Level 3, Singtel Special Exhibition Gallery and various locations around National Gallery Singapore

The advertising material explains that this is an exhibition

“Comprising over 200 paintings, sculptures, drawings, performances and sensorial installations, Tropical spans the 20th century, tracing how artists from both regions challenged conventions and fostered solidarities, defiantly reclaiming their place within the story of art.”

Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, was a well advertised exhibition. I had particularly wanted to see it even though the entry fee (S$25) was astronomical for foreign visitors (the equivalent of five breakfasts in Singapore. I dare not count how many in Malaysia).

An aside: I had studied Latin American art for my first Masters (Art History & Theory) under the illustrious Dawn Ades (CBE, author and participant in ‘Art in Latin America: The Modern Era, 1820-1980’, book and exhibition). Plus I have spent the past two decades promoting South and South East Asian arts, hence my interest was piqued by the idea of this particular Singaporean exhibition drawing some sort of parallel(s) between South East Asia and Latin America.

Having bit the proverbial bullet re the entrance fee, I have to agree that the enterprise was entirely worth while. Held over several well constructed rooms, the collection - Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, and its presentation of items, was quite astonishing. While the exhibition was visually stunning, put together to good effect and superbly lit, the theoretical side seemed rather tentative, arbitrary

and thrown together.

I did have the thought how did the term ‘Latin America’ (coined by French economist Michel Chevalier in the 1850s) with its disparate countries ever ‘come together’ (as claimed by one panel in the exhibition) with ‘Southeast Asia’ (term first used in 1839 by American pastor Howard Malcolm in his book Travels in SouthEastern Asia), other than with association with artists such as the Colombian Fernando Botero, whose multiple sculptures grace various venues across Singapore, but is not mentioned in the exhibition.

Also not mentioned in ‘Tropical’, was the (admittedly tenuous) link to Mexico and Malaya with the writings of Gene Z Hanrahan (‘The Communist Struggle in Malaya’, and Documents on the Mexican Revolution. Vol. I’), concurrently displayed in another exhibition (Singapore Art Museum ‘SAM’, titled HI Tzu Nyen: Time and the Tiger’ [Reflections on Asia by the critical acclaimed Singaporean artist Ho Tzu Nyen]).

In the National Gallery’s ‘Tropical’ exhibition, paintings were, in places, marshalled together (in neat rows) greeting visitors with a conjured sense of history and of ‘Modernism’. The main gallery gave the artworks the dignity to be seen on their own, but together, with names and data on the reverse. This proved handy not just for seeing the works unencumbered, but also good for photography.

Despite there being much in that first gallery (on floor three of the National Gallery), there

was never a sense of being crammed. That is to say that the display was visually well thought out, visually appealing and, to some extent, informative. Not just in the first gallery, but the ‘Tropical’ exhibition design, overall, had the appearance of being professional and intriguing.

However, to make the claim that the exhibition spanned the 20th century, might be a slight exaggeration. In reality, there had been a distinct concentration on the early years of that century, with a hint that this particular art journey had begun with the French artist (Eugène Henri Paul) Gauguin, in the later part of the 19th century. This, for me, provoked a debate regarding JeanJacques Rousseau and his idealised ‘Noble Savage’ and the notion of Indigenism. While, as a working hypothesis, that belief may have been helpful for the ‘Tropical’ exhibition, one reality suggests that Latin American artists (like the Mexican Diego Rivera), had been directly influenced by Pablo Picasso (whom he had met and befriended in Paris) and, initially, ‘Cubism’, rather than Gauguin. Another Mexican artist, (and fellow communist) David Alfaro Siqueiros, along with Rivera (et al) was part of ‘The Mexican Renaissance’, but Siqueiros had disagreed with Rivera’s leaning towards what Siqueiros explained was a folklorism’ approach to indigenous peoples, believing Rivera to be pandering to tourism.

Back to the first exhibition section of ‘Tropical’ - "The Myth Of The Lazy Native”, seemingly drawn from the seminal book ‘The Myth of the Lazy Native: A Study of the Image of the Malays, Filipinos and Javanese from the 16th to the 20th Century and Its Function in the Ideology of Colonial Capitalism’, by Syed Hussein Alatas (1977). In that book Alatas posits a Colonial mis-reading of the mind-sets and ‘cultures’ of indigenous peoples’ in comparison with the colonial ‘White Anglo-Saxon Protestant’ (WASP)

perspectives. Though, to be honest, perhaps Alatas’s later work ‘The Captive Mind and Creative Development’ might have been more relevant. For that is where Alatas cites a difficulty with a still extant ‘inner’ captivity arising from colonial conditioning.

In the ‘Tropical’ exhibition, one initial (large) painting from The Philippines (Mother Nature’s Bounty Harvest, 1935: a collaboration between three renowned Filipino artists, Victorio C Edades, Galo B Ocampo and Carlos ‘Botong’ Francisco, aka the ‘Triumvirate of Philippine modernism’) dominated that first exhibition gallery and, tentatively at least, intended to draw parallels with Paul Gauguin’s Tahitian style. Opposite ‘Mother Nature’s Bounty Harvest’ hung ‘Pobre Pescador’ (Poor Fisherman) a 1896 work by Paul Gauguin, thus making connections to an imagined visual heritage. "Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? Indeed.”

On the other hand, I did wonder why, when ‘Tropical’ is to all intents and purposes an exhibition concerning Latin America and Southeast Asia, is South Asia, that is to say India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh (East India aka East Pakistan) included into South East Asia?

Was this another example of a desperation to reveal alliances where none actually existed? If, and I do say if, South Asian artists were to be included in such an exhibition, then surely including Quamrul Hassan and Bhutan Khakhar, yet leaving out artists like Amrita Sher-Gil (the first Indian artist to bring back a ‘School of Paris’ style to India and Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin (who, because of the partition of India, went on to found Dhaka’s best known art school), beggars belief. Those inclusions and exclusions seem so very arbitrarily.

Instead, if the exhibition had been brave enough, it might even have mentioned the French Surrealist (and communist) Andre Breton (who visited Mexico in 1938 and 1940 and stayed with member of the Mexican Communist Party, Frida Kahlo) and his communist interactions with various factions, in what is now known as Latin America.

Now, sadly, on to the exhibition’s catalogue (a whopping SG$ 54), of which I have concerns. Considering the large price-tag why is the catalogue ‘Tropical’ (“published in conjunction with Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, an exhibition organised by the National Gallery Singapore, 18 November 2023 - 21st March 2024”), so dire?

Victorio C. Edades, Bulul at Babee

Victorio C. Edades, Bulul at Babee

Carlos ‘Botong’ Francisco, Courtship ritual

Carlos ‘Botong’ Francisco, Courtship ritual

Pratuang Emjaroen, The Orchardman’s Smile

Pratuang Emjaroen, The Orchardman’s Smile

Semsar Siahaan, Beautiful villa

Semsar Siahaan, Beautiful villa

Why does said catalogue use a difficult to read text font? The whole catalogue is an unimaginable case of form not following function. Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius would be turning in his grave. One of the first things you learn when studying graphic design is that communication must take precedence over style. In the ‘Tropical’ catalogue frequently text sentences are far to long, or of a too large or too small font size to be easily read. Text needs room to breathe. Sadly the text in ‘Tropical’, by Shabbir Hussain Mustafa, suffers heavily from a lack of breathing room and presents as too solid a block to warrant attention. Whereas the Malay emboldened and italic text, on pages 15 - 17, shouts too loudly to attract. From there on, the inconsistency of text size and line size (such as on page 91 etcetera) demonstrates either a total disrespect for the reader or a simple arrogance of the designer, editor and all who were responsible for the catalogue publishing.

I idly wondered, was the catalogue designer(s) just aping Dada or Fluxus, for no particular reason? It’s simply not good enough National Gallery. The catalogue design does not appear to connect with the overall design of the ‘Tropical’ exhibition, its posters et al.

While the exhibition was visually stunning, put together to good effect and superbly lit, the theoretical side seemed rather tentative thrown together. Overall, despite niggling concerns regarding intent, and the “tentative, arbitrary and thrown together” nature of this brave enterprise, I enjoyed the exhibition ‘Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America’.

However, I did get the distinct feeling that there was a desperation to prove something unprovable, to forge connections which were never actually present. While, quite independently, there were movements and individuals pushing back against various leaders of society, in various countries in regions now become known as Latin America, and Southeast Asia, there had not been a joint venture to do so. It also could be argued that colonialism did not stop in the 20th C, and that Alatas’ notion of the ‘captive mind’ is ever present in fresh colonising forces, particularly from the US of A and Middle Eastern countries, who have exported their mindsets as countless others have before them, but in more covert ways.

Ed

Roberto Feleo, The Retablo of Bantacay

Roberto Feleo, The Retablo of Bantacay

Sutra Gallery

Sutra Gallery

Sutra Gallery

Sutra Gallery

For most people, when they hear, or read, the term ‘Peranakan’, they might immediately think of the ‘Nyonya’ cuisine and the richness of its flavours, scents, and indeed the tastes.

In her book ‘The Penang Nyonya Cookbook’ (Marshall Cavendish Cuisine, 2009) Cecilia Tan suggests that these dishes (among many) might give some notion of the Nyonya style of cooking… “Purut Ikan (a delicacy made from preserved fish stomach), Bosomboh (a crispy salad tossed in a thick sauce), Salted Fish Branda, Penang Rojak and Nyonyan Prawn Congee”. Ultimately, Nyonya cuisine is ‘fusion food’ long before that term existed. Within Nyonya cuisine is a unique blend of Chinese, Malay and, in the case of Penang, Thai influences too.

Aside from the cuisine aspect, you may recall the slightly exotic terms Baba-Nyonya, or ‘Straits Chinese’, then stop and start to consider what these terms mean, and why are they so deeply embedded into the cultures of Malaysia. I know that I did…

It just so happened that I was in Penang for a few days. By chance, as I was wandering around the backstreets of George Town, taking photos of architecture like Charles Geoffrey Boutcher’s Art Deco facade of the OCBC Bank, on Beach Street (his 1938 facade replaced the original 1880s façade, with a dull grey finish known as ‘Shanghai plaster’). It was then, nearby, in Church Street, that I came across the splendour that is the Pinang Peranakan Mansion. According to ‘Wikipedia’, that magnificent building is

“…a museum dedicated to Penang's Peranakan heritage. The museum itself is housed within a distinctive green-hued mansion at Church Street, George Town, which once served as the residence and

office of a 19th-century Chinese tycoon, Chung Keng Quee.” Penang is seen, by some, to be one of the ‘northern’ Malaysian centres for ‘Peranakan’ or Baba-Nyonya culture.

Then who were/are the Peranakans the BabaNyonyas, the Straits Chinese?

In the preface to her book ‘A Nyonya in Texas’ (Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2007) Professor Lee Su Kim explains “The Peranakan culture is a rare and beautiful blend of two cultures—Malay and Chinese—in a fascinating synthesis with elements of Javanese, Batak, Siamese, British and Portuguese cultures.”

Further, Malacca’s Baba & Nyonya Museum suggests that…

“Some folklores suggest that Peranakan roots in Malaya began with a princess from China who married a local prince. Historically however the term Peranakan was used to refer to a number of different ethnic and cultural groups in Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore. The root word for Peranakan comes from the Malay and Indonesian word ‘anak’, or child, referring to locally born descendants.”

Elsewhere, we are informed that the word ‘Baba’ (as in Baba-Nyonya) may have been a Malay generic term for Chinese who were born in Malaya’s Straits Settlements, which could have its roots in Hindu/Sanskrit/Persian and an honorific meaning father or grandfather. The term ‘Nyonya’, on the other hand, may have come from Java, from Dutch, or might have its origins in the Malay and meaning ‘auntie’. The term ‘Straits Chinese’ would have literally meant Chinese descendants born within the Straits Settlements, which were, according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica “former British

crown colony on the Strait of Malacca, comprising four trade centres, Penang, Singapore, Malacca, and Labuan, established or taken over by the British East India Company”.

Historically, Peranakans/Straits Chinese/BabaNyonyas were descendants of the male seafarers who sailed from Southern China (Nanyang) to the Nusantara (Malay Archipelago). Being male, and without Chinese women (who were then restricted from travelling abroad), these men married local woman. While some like to date back these intermarriages to the 10th century, maybe even back to Chinese visiting or living in the ancient port of the Bujang Valley (7th century), one focal point seems to have been the visits of the Chinese explorer Admiral Zheng He (Cheng Ho), between 1405-1433AD, and his crew.

Another explanation remarks that in the year 1459, Chinese princess Hang Li Po (or Hang Liu), was sent by the Chinese emperor to marry the Malacca Sultan Mansur Shah (who ruled between 1459 and 1477). The princess came with her entourage of five hundred male servants and a few hundred handmaidens, who eventually settled in what is now known as the ‘Bukit Cina’, area of Malacca.

Penang’s glorious Pinang Peranakan Mansion (or Hai Kee Chan/Sea Remembrance Hall), was not founded by the Baba-Nyonyas or their descendants, but was built by a leader of a famous triad (gang), one Kapitan Cina (leader of the local Chinese community) Chung Keng Kwee, who won the plot of land in a fight with the leader of another triad, Ghee Hin. That mansion, once derelict, was restored and has since become a vast repository of Baba-Nyonya culture, revealing fabrics, furniture, jewellery (et al) related to that culture, and a sheer joy for me to visit.

Ed

Tanjong Pagar

Distripark multidisciplinary arts cluster

Singapore

“Singapore Art Week (SAW) represents the unity and pride of a diverse and vibrant arts community in Singapore.”

By chance, I was in Singapore approximately one week before the start of Singapore’s 12th ‘Art Week’ (aka SAW). Preparations had been underway, and I had a classic opportunity of witnessing the emergence of some of 2024’s exhibitions, from their naissance.

A Singaporean friend had mentioned that I should seek out Tanjong Pagar Distripark, at 39 Keppel Road in the Tanjong Pagar (‘Cape of Stakes’. A reference to wooden fishing traps, using stakes), area of Singapore, to witness Singapore’s latest arts endeavour.

Singapore’s National Arts Council (NAC) had been looking into collaborations with tenants of one particular warehouse building in Keppel Road. That ambition was to develop yet another Singaporean arts hub, alongside the respective and respected Singapore Art Museum and the impressive National Gallery Singapore. The endeavour followed on from Gillman Barracks (9 Lock Rd), a Singaporean ‘arts cluster’ opened in 2012.

I had been confused. My ‘Grab’ driver had been confused. He’d dropped me at what appeared to a Singaporean ‘Harbour Front’ warehouse, at 39, Keppel Road, Tanjong Pagar.

I had looked around, feeling as if I were a character written by Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. There had been wooden palettes stacked outside a large building, and no clear means of ingress.

Not knowing how to gain entry I’d wandered inside through what appeared to be an industrial PVC Strip Curtain. Low and behold I had gained access into an area with two dimensional works of art on the walls, and various three dimensional

pieces dotted about. I, clearly, was in some sort of art gallery.

There had been no external signage to demonstrate what the place was. The mystery was exciting, while simultaneously being uninformative and bloody annoying.

Was it the ‘right’ place?

I had quickly realised that the whole space was some sort of work-in-progress. No name to the gallery/galleries was evident. There had been no labels associated with objects, no textual information. No delineation between artists had been present. I had stumbled into another (perhaps green) world (with Brian Eno playing in my head).

I wandered freely (like a proverbial, though plainly lost, cloud). I had been unchallenged and taking photographs. It wasn’t until after, when I was exiting through the only door which I thought led to a ‘Grab’ pick-up place, that I was challenged. A young lady repeated that I shouldn’t be there, and that the place was dangerous for me. Maybe she was right.

Earlier, before my accompanied exit from Tanjong Pagar Distripark, I had stumbled my way around the huge building, missing much I am certain. I had been in and out of lifts, bypassing small businesses and art galleries (closed and preparing for the main event - Singapore Art Week). It was frustrating to be so close, and yet so far away, from the emerging displays in the galleries. Frustrating too to be unable to discover any sort of cafe, or meeting-and-greeting place. A place to sit and gather my thoughts over a coffee would have been welcome. But none came my

One gallery (39+), although also busy with display construction, allowed me access and encouraged me to take photos and chat, briefly.

Elsewhere within that ‘Borg’ like cube, sat a slightly displaced SAM (Singapore Art Museum) which normally existed at Bras Basah Road and Queen Street, but are closed for redevelopment. Sadly, by the time that I had paid SG$ 5 (Standard Senior entry price) to get in, my senses were already reaching overload.

The various video presentations, and their accompanying audio, became too much for my poor ageing ears. I couldn’t complete my tour. I nipped out for relative peace and quiet. It was then that I had sorely felt the absence of any kind of place to sit and reflect.

I called a ‘Grab’, and exited back to the latterly infamous ‘red light’ district of Singapore’s Geylang.

And the wooden palettes? Either protective fortifications against those barbarians who are known to be at the gates, or an homage to the American artist Liz Glynn and her ‘The archaeology of another possible future’.

Ed

Özer Toraman ( b.1989 ) is a painter living between Istanbul and Berlin. He is known for his unique approach to landscape and portraiture, which sits between the figurative and the imaginary. Using photographs that he has taken while travelling the world as inspiration, Toraman creates works that are ‘windows’ to another realm. The artist’s signature use of flat colour planes, combined with meticulously detailed features, shuns fixed meaning and invites viewers to impart personal significance onto each scene. The Ocean in my Heart, invites viewers into a world where imagined landscapes blend with reality. Inspired by photographs taken in different countries around the world, Toraman’s paintings combine the imagined with the figurative, creating what the artist considers to be windows to another realm.

Strolling figures and idyllic beach scenes become surreal in their isolation, while languid grassy picnics and intimate portraits become untethered to the limits of reality. Through his focus on beach and sea-side scenes, Toraman’s recent series draws on both his own travels and connection with the ocean, as well as the geography of Singapore itself. His palette is particularly fitting in that he opts for pastel hues as an instinctive link to his own childhood memories, with blue being particularly dominant across his works. For Toraman, blue allows him to “dream without limits,” and further positions these vignettes as windows or glimpses into a dream-scape.

Tari tayub

Tari tayub

It was his 1988 oil ‘Pertunjukan Seni Sunda’ that first captivated us and which we acquired in 2009. In the painting, musicians perform a traditional ‘Sunda dance’ with grace and sensuality, in their concentration to support the dancers and reward the audience. The energy of the dancers is palpable - yet the dancers are outside the canvas and connected to it only by the painter’s magic!

Otto Djaya was of a Sundanese family of old nobility and little wealth. The family lived in the historically important Banten region on the western tip of Java and near to Jakarta, known then as Batavia. Batavia was the capital of the Netherlands East Indies, a vast Dutch colony in South Asia until 1949.

Raised in the Sundanese/Javanese culture and in the Dutch language, his father a civil servant of the Dutch colonial administration, Otto Djaya was privileged to have access to education reserved by the Dutch for the Javanese elite. He was introduced to painting and joined painting classes in school at the age of twelve. Painting possessed him and became a destination and his life.

A staunch nationalist, Otto Djaya’s life was engaged, eventful, and complex; his abstract figurative paintings were formidable in narrating stories of the past and the present of the Javanese people and of Java, with Bali intermezzos. In fact, from the 1940s and into the 1980s, his paintings were frequently reflective of Hindu-Javanese convention that again were a component of Malayan-Polynesian culture that dwells in Java and Bali to this day. 1940s - 1950s paintings by Otto Djaya, and his older brother Agus Djaya

(1913-1993), heralded Indonesia’s independence of the Netherlands and the struggle to obtain and to develop it. The forces and violence of the myths they expressed in their paintings were a form of artistic resistance during political upheaval that, at the time, celebrated the revolutionary spirit of Indonesian youth who revolted and went to war against their colonial masters. The visual language and aesthetics of the culture were believed to have communing and empowering effect in the struggle for independence.1 While the Djaya brothers with their works proposed this artistic direction for Indonesian modern art, their peers generally painted expressionism of a different inspiration.

The war and revolution that Otto Djaya experienced first-hand during 1943-1946 remains vivid and basic in his paintings even as he painted war and revolutionary themes from memory much later in his life. Unfortunately, of his early paintings we know only of a few outside of museums and similar environments. Throughout his life Otto Djaya got new ideas to expand on motifs he had painted in the past as well as he repeated motifs and ideas he had painted in the past, after modernizing and improving them. He frequently received requests for paintings similar to his paintings that had become a part of the Presidential Collection of Sukarno and of the collections of other dignitaries and collectors.

In 1938, at age 21, Otto Djaya joined Persagi, a newly organized group in Batavia of two dozen or so young indigenous painters. Sindusudarsono (S.) Sudjojono (19138 1986) was Persagi’s articulate and fiery secretary and spokesman; Persagi’s chairman Agus Djaya,

Otto’s older brother by three years, was debonair and extrovert and good at networking. Otto, ordinary Persagi member, was reserved, earnest, and a romantic-inclined-to-be-humoristic.

Persagi members, generally well educated locally and nationalists by outlook, protested the discrimination of indigenous painters that prevailed at the elite level in the Netherlands East Indies. Persagi was coherent as was Sudjojono’s

Dutch painters were encouraged and supported whereas indigenous painters were not. In the context of colonial policy, the painter was Dutch when his/her father was Dutch originally. Dutch painters outnumbered indigenous painters and the elite advice for the indigenous painters was to ‘return to planting rice’. This was not a good starting point from which Indonesian painters could aspire to participate in the development of Indonesian fine art.

eloquence: do away with colonial baggage as far as the fine art was concerned. Paintings by the colony’s embedded Dutch painters and by visiting artists tended to portray a tranquil and beautiful land, Mooi Indië, the beautiful Indies. The genre was centuries old. It was market and souvenir oriented, popular with the elite in both the East Indies and in the Netherlands. A few indigenous painters followed the style that was in commercial demand. However,

Nevertheless, the Persagi painters were inspired and exhorted by S. Sudjojono to portray the reality in the colony: the subsistence conditions most of the population lived under in the cities and in the agricultural fields; peasants endured hard and often cruel conditions. Direction, supervision and enforcement were by Dutch officials. The operating system required the intervention of local feudal chiefs and their courts, prepared

to be brutal when necessary, and for which the Dutch took little or no responsibility.

The Persagi painters sought out realism firstly relating to life on Java. This left room for abstract elements; the new painting style was individual and nationalistic, some saw it as social realism, others saw it as Indonesian expressionism. Sometimes it was exaggerated, as was the Mooi Indië style it professed to be protesting.

Nationalistic sentiment, anti-colonialism, was growing rapidly in the population in the 1930s.

had facilitated the politicization of Indonesians down to the village level giving the nationalist leaders a political voice. Japan’s destruction of the Dutch colonial regime and the facilitation of Indonesian nationalism created the conditions 9 for the proclamation of independence for Indonesia within days of the Japanese surrender.

This helped increase the enthusiasm with which the indigenous painters confronted the low status the Dutch art elite in Batavia afforded the new painting style. By then recognition and support of the new expressionism was growing among the people. Four years after Persagi’s formation earth shaking changes occurred in the Colony. In March 1942 World War II in the Pacific reached the shores of the Netherlands East Indies. The Netherlands East Indies surrendered to Japan. Japan’s military occupation of the East Indies ended in August 1945. In the meantime Japan

On 17 August 1945, national leaders Sukarno and Hatta declared a Republic of Indonesia, independent of the Netherlands. Indonesians revolted when the Netherlands administration and armed forces returned to reclaim the colony with the help of their British allies and forced the Indonesian government out of Jakarta to Yogyakarta. The Revolutionary War had begun. Immediately Japan surrendered, Otto Djaya had gone to join the indigenous paramilitary youth force, Pemuda, in the revolution against the Dutch for an independent Republic of Indonesia.

The Japanese military had previously trained and organized selected Indonesian volunteers for the future defence of Java: to keep the Dutch from retaking the colony. Otto Djaya was among

the selected volunteers, trained to command a company. He fought in battles south of Jakarta, at Sukabumi, against the advancing British and Dutch forces. The 9-12 December 1945 battle at Bojong Kokosan halted the tank supported advance. Otto Djaya and his command fought in that battle.

The British forces had withdrawn from Indonesia by November 1946.2 Otto Djaya had by then resigned his military role to resume painting,

to capitulate and finally grant independence to Indonesia.

In the middle of 1947 Otto and Agus Djaya, Agus with family, sailed from Jakarta to Amsterdam on the s/s “Nieuw Holland”. They brought along with them on the ship 170 paintings and other Java related cultural art items, representing their recent works and their private collections to exhibit and to sell. They were going to show the new wave of Indonesian expressionism painting

now of the emerging Indonesian army in front line activities. He showed paintings from the front line at a solo exhibition at the National Museum in Jakarta in 1946. In 1947 he and brother Agus exhibited together in Jakarta on at least one occasion.

In 1946 the war of revolution was turning partially into a war of diplomacy. It was to be the end of 1949 before the Netherlands were forced

in the Netherlands - at a time when similar expressionistic ideas had only just sprouted in Europe and USA and were still to surface in South and East Asia, outside of Indonesia.

How the brothers’ two-and-a-half year sojourn in the Netherlands was arranged and paid for is unclear, but it seems clear that it was a mission at the behest of the Sukarno-Hatta government; Sukarno, especially, wished to show off to the

Netherlanders what indigenous Indonesian artists had achieved. Also, his government sought to gain insight in sentiments and pro- and anti-independence lobbying in the Netherlands’ capital, Amsterdam, and to try and influence the direction of negotiations.

an acclaimed painter, was an intelligence officer with the rank of colonel in National Intelligence, a section of the Department of Defence.

At Sukarno’s request, the Netherlands East Indies government by Governor-General Van Mook (1884-1965), agreed to send the Djaya brothers to Amsterdam for art studies at academy level and

The Djaya brothers seemed the ideal team for such a mission at the time. Both spoke Dutch fluently. Otto had become a recognised progressive painter, with military training and battle experience in the War of Revolution and rank of major; his older brother, Agus, already

to try to arrange exhibitions and promote the fine art expressionism by indigenous Indonesian artists. The two received Malino grants. National Intelligence raised funds for Agus Djaya’s intelligence portion of the mission. There is no evidence that the Netherlands East Indies

government and Governor-General Van Mook were aware of this blend.

The Djaya party arrived in the Amsterdam in June 1947, Otto and Agus carrying accreditations as cultural envoys, and enrolled as guest students at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten. Further, Agus Djaya carried an accreditation by President Sukarno for viewing painting collections and acquire paintings and another accreditation as a representative of Indonesian news publication “Merdeka”, a publication founded by BM Diah. B.M. Diah was one of the dozen or so Indonesians seen standing behind Sukarno in his house during his proclamation of independence on 17 August 1945. Soon after

Sandberg.

Buda maya

Buda maya

arrival Otto Djaya registered for philosophy classes at the Gemeentelijk University. Few data exist at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten about the Djaya brothers, as if they were seldom there. Their painting studios while in the Netherlands appear to have been in private houses, perhaps the houses wherein they stayed during the years in Amsterdam.

At the invitation of the Stedelijk Museum the Djaya brothers showed their work there at a solo exhibition that opened on 10 October 1947, the catalogue cover designed in red and white, the colours of the flag of the Republic of Indonesia, as agreed with the head of the Stedelijk, Willem

Otto Djaya’s painting career covered the sunset of colonial times, war, revolution and independence for Indonesia, and two longlasting autocratic regimes and the transition to democracy. In fact, in the macro perspective of fine art and painters in Indonesia, the years 1937-1965 were especially fertile. We can say that the impetus by Persagi, the occupation by Japan, the revolution against the return of Dutch sovereignty, and the Sukarno years and politics, combined to catapult Indonesian fine art into a world class phenomenon, aesthetically and technically on par with the modern art of economically advanced Western nations, and in a class of its own among Asian peer nations.

Otto Djaya projected realism by narrating folk myths, traditions, celebrations, work, leisure, and romantic moments in the mundane lives of the Javanese people.

Otto Djaya was a non-conformist artist who defined a reflective and personal aesthetic of his own, never following any art fashions. Even in his paintings from memory-of-war-and- revolution events he witnessed first-hand he painted vivid yet basic motifs when his peers preferred large canvasses.

Otto Djaya was a storyteller. The attraction of an Otto Djaya painting derives from a combination of the mystery the work transmits, the story itself, whether of myths or traditions, His painting technique and colour palette. His canvasses lavish viewers with romantic renditions and anecdotes from the changing society of the Republic of Indonesia, Java especially, since the 1940s and until his death six decades later.

Otto Djaya’s brush-stroke had by now become distinctive and rarely failed to generate recognition and emotional response, pleasure or surprise. Deeply analytical of humanity, including of his own, he synthesized myths, traditions, natural beauty, and satire, and did not mind to caricature himself.

Otto Djaya’s focus was the Javanese and he explored, expressed and integrated the spiritual and mundane lives of the Javanese people through sixty years of history that shaped modern Indonesia. His paintings were easy to understand even if they frequently featured the mythical, godly Punakawan, the sons of Semar: Gareng, Petruk and Bagong, to interact with the story and the viewer, leaving interpretation to the imagination of the viewer and his/her familiarity with the Punakawan.

Otto Djaya did not live long enough to witness an Indonesian president being elected by popular vote for the first time in 2004, but in his wisdom he must have sensed it was about to happen when he passed away in 2002.

Otto Djaya was a romantic, a dreamer; humble and respected. He did not promote his noble ancestry and privileged youth to try to better his position in life. His painting career sustained his family, never made him wealthy. Having fought in the war of independence, his art, his family and Islam made life meaningful to him. Otto Djaya, the romantic, had apparently become cynical of politics early on his life’s journey. His dislike of politics led him to keep a distance to national politics and political affiliations throughout his life, unlike several of his artist

peers. His stance may have saved his career, and even his life, in the turmoil of the regime transition from Sukarno to Suharto beginning in the latter part of the 1960s. Perhaps as a result of his neutral orientation in politics, which was unusual at the time, Otto Djaya did not obtain one or more supporting collectors in political and private circles.

Otto Djaya is less of an enigma now, in 2019, three years after the comprehensive Otto Djaya 2016 Centennial Exhibition at the wonderful Galeri Nasional Indonesia Jakarta that attracted much media attention and 4,000+ visitors during the eight days the exhibition was open to the public. The Centennial also surfaced additional information.

Otto Djaya remains a famous and acclaimed son of Banten and a genuine Indonesian artist who deserves to become a legend strongly grounded forever in the history of art in Indonesia.

Otto Djaya and his art were taken for granted during most of his life, but the bohème that he was and deep thinker that be became brought him to the arena of public acclaim.

It would have given us great satisfaction to have been able to meet him in person and to thank him for the pleasure of his paintings that we have viewed. But that was not to be. Now our journey of discovery and chronicling about Otto Djaya has come to an end. Trails turn cold after one hundred years. The environment is conducive to paintings perishing due to the past condition of paints, boards, paper, canvasses and framing, and less-than-ideal storage conditions by succeeding generations of owners. Nevertheless, our journey returned us much inspiration and pleasure as we managed to locate and meet with the extended family of Otto Djaya and Agus Djaya, studio helpers, eyewitnesses, art academicians and historians, and the friendly staff of institutional and media archives, auction houses, museums, and libraries in Indonesia and the Netherlands, who, we would like to believe, share with us in applauding Otto Djaya and his

story-telling.

Our special thank yous to old friends the Hans Tabalujan family for enabling us to realize our concept of combining the Otto Djaya chronicles with the visual splendour of some of Otto Djaya’s best works. And to Didier Hamel, friend, art connoisseur and historian, author, (our) publisher, and gallerist in Jakarta, who fired us up initially and contributed immensely to our motivation, research discipline, insights, and the completion of the first Otto Djaya book, on time for the Centennial in 2016; and to Amir Sidharta, friend, art connoisseur, historian, researcher, auctioneer, source of field information and sound advice - and son of Myra Sidharta, our friend, who was a young eyewitness to Amsterdam in 1947 and the Djaya brothers’ first residence there.

Text from the ‘Book of Otto Djaya’ by Inge-Marie Holst and Hans Peter Holst, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, June 2019.

The writers’ new book about Otto Djaya is imminent.

Ram Singh Urveti was born in 1970, in Madhya Pradesh, India. His works are exhibited in India and abroad, and have received several awards. His books include the co-authored “The Night Life of Trees” and “Sun and Moon” among others, published from Tara Books. His painting themes are broad, including tribal life, rituals, myth and folklore.

Ram Singh Urveti has been working in The Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGRMS) for the past 17 years. His first love is trees, appearing throughout his works. A folder concerning his trees has been published by the Adivasi Lok Kala Academy, Bhopal.

His style represents Gond Art, which is the painting of Pardhan Gonds, the indigenous people living near Madhya Pradesh, in Central India.

In the past, Pardhan Gond people would sing invocations to the divine beings in nature, along with a stringed instrument called a ‘Bana’. They were also the storytellers of the villages, educating younger generations about mythology and culture. Gond art originates in the wall decoration made in their houses as a part of daily life.

Gond art is characterised by mythical as well as folkloric motifs passed down, floral as well as faunal motifs, patterned designs. Gond art has been introduced to many museums.

A bird surrounded by foliage

A bird surrounded by foliage

The Venice Biennale is the most important and historic event in the global calendar of art events that take place in the city of Venice, Italy. This event is certainly special for me as I have been invited as a speaker representative from Southeast Asia to be part of the 'abaakwaad' event held from 22 to 25 April 2022 at the seminar hall, Cultural Center Don Orione Artigianelli, Venice, Italy. The dialogue program known as 'Current Gathering' brings together conversation on indigenous art by those who create, curate and write about it. This event is a partnership with 'The Sámi Pavilion: Aabaakwad 2022' as part of the main component of this historic event in the 59th edition of the Venice Biennale. For the first time, it features artwork by three artists from the Sámi indigenous community, Pauliina Feodoroff, Máret Ánne Sara and Anders Sunna.

The Norwegian government has given honour to them as representatives to the Venice Biennale this year. The 'aabaakwad' program, which carries the meaning 'It clears after a storm', is an annual event that was established in 2018. 'The Sámi Pavilion: Aabaakwad 2022' is a joint venture with the Nordic Pavilion, Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), Office of Contemporary Art Norway (OCA). It actively gathers more than 70 artists, curators and thinkers from the participation of '39 First Nations' and Eight Nations has participated in this event. The 'aabaakwad' initiative is a gathering that alternates annually between Toronto and international venues, showcasing dynamic dialogue examining themes, materials and experiences in indigenous art practice globally.

On April 24, at precisely 1.30pm, the culminating event of The Sámi Pavilion: Aabaakwad 2022'. The most awaited dialogue program, 'Current Gathering', begins after moderator Wanda Nanibush introduced the ‘Narrative Healing’ segment on the panel. Among them were myself, Elias Yamani Ismail (Malaysia), Wesley Shaw (Australia), Darlene Naponse (Canada), Nanobah Becker (America) and Matti Aikio (Findlandicely 1.30pm, the culminating event of The Sámi Pavilion: Aabaakwad 2022'. The most awaited dialogue program, 'Current Gathering', begins after moderator Wanda Nanibush introduced the ‘Narrative Healing’ segment on the panel. Among them were myself, Elias Yamani Ismail (Malaysia), Wesley Shaw (Australia), Darlene Naponse (Canada), Nanobah Becker (America) and Matti Aikio ( Finland). I was given the honour to open the dialogue and closing the ceremony at the event. The atmosphere of the hall seemed keen to hear what I wanted to say in conjunction with the prestigious event. I began by explaining that my talk today is presented in a chronological

manner. My wish and hope are to take the audience with me on a journey to a beautiful paradise, calm and peaceful world. But I had to warn the audience that the serenity of this realm will not remain calm forever, it will be hit by a mighty wave that changes everything. The first image of the presentation on the slide are the word 'Tanahair' and the line below it with the word 'Sundaland'. While in the background, coconut trees are visible with picturesque images with idealistic compositions of beach-front images facing the mirage of the sea. The audience was in awe of the beauty of the scenery...I surprised them by asking the audience questions: "Do any of you here know about Sundaland?’ The hall was silent, surprised and stunned,, then I continued my talk by stating I come from this land 'Sundaland' or ‘Pentas Sunda’ a place full of magic even uncanny that has been forgotten lost in our memory of consciousness.

The discussion topic of that day was 'Narrative Healing'. I explained that my talk will be divided into three parts, namely 'Prelude, Act of Healing, and Art practice & Self-healing'. On the second part of my slide was a map of the Southeast Asian region as we know it today. I told the audience that these regional lands had been seized and colonised by colonial powers. This tragedy impacted the communities shifting our world view, which I term the emergence of a new paradigm as the 'White World', has changed many civilisations in the world today. I emphasise the concept of 'Tanahair' which means that the lands in this region are not separated by the sea that surrounds them. But it was successfully separated by colonial western powers such as Portugal, the Netherlands, Britain, Spain, France and America. This effect still continues and now the countries in Southeast Asia continue to fail to unite. It results in the existence of nation states and are bound by the agendas of their respective countries.

As I relate to the topic of 'Narrative Healing' in the final part of my presentation on 'Prelude, Act of healing, and Art practice & Self-healing'. The audience were focused on the image of the slide that was displayed. It's an image taken from above that shows the environment of the city of Kuala Lumpur. The words 'Past, Present and Future: Moving Forward' were shown in the image. I reminded the audience again that the image of a beautiful land with coconut trees and a view of the beach has now changed. In this section I begin to share about 'Art practice & Self-healing'. As I confidently, assert to the audience, we can reflect on the history in the past of what has happened to this land and its inhabitants.

The narrative has been written instead of longing of the past. I told the audience, it’s how we choose to change and navigate to move forward. I explained to the audience that I tried to relate to the discussion within this context. I am now here and I was born and growing up around the environment of this city. Certainly, there are various factors that differentiate me from the previous community that had lived in this area with those who exist now. However, as a artist present and now, I am part of a continuity of knowledge and understanding of this environment. It is proven that the people in this region have high craftsmanship skills, reliance and indigenous knowledge born from the Malay World that managed to utilize natural science from its environment to benefit the people living in this environment. Furthermore, I as an artist, certainly do not easily

burden myself with challenges or obstacles when the desire to create arises.

In discussing my work title ‘Pembinaan Semula No.3’ and 'Icarus', obviously, the materials I use to build my artworks come from different approaches and to non-conventional materials. However, it reminded me that the tradition of craftsmanship and improvisational practices that has long been practiced here by the people of this land here cannot be lost. The initial work, titled ‘Pembinaan Semula No.3’ was produced by weaving a used tape measure paired with a plastic ruler with cut-out stencil lettered and numbered surfaces. This purpose to reuse or reproduce two used industrial materials succeeds in bringing out a juxtapose, contrast and a new meaning that is certainly not a 'recycle' method that is more geared towards application.

The foundation that I put forward here are influenced by the understanding of the concept of 'bricolage' a term introduced by an anthropologist named Claude Lévi-Strauss. Personally, I think this concept is closely related to the motivation of individuals who had nothing. Then how the individual is able to overcome resource limitations with the goal of being creative by using wisdom and creativity to adapt in building creations or improvising and problem solving. In the next image is a sculptural piece titled 'Icarus', 2014 that takes inspiration from Greek mythology. In this work, I combined two different materials, namely an industrial car door with natural materials such as rattan, which are built by hand into a structure. There are several contradictory or contrasting aspects to this work but it is successfully harmonised to create a new manifestation of creation.

On the next slide of my presentation I showed the audience a series of drawings titled 'Kajian No.3' that I produced in 2016. I mention that I would like to start a new body of work but it isn’t necessarily similar to the one I did in 2016 but somehow, there was a continuity in the idea avoiding me from repeating. It has to grow. As I explained when this series of drawings was produced, the nation was under a state of restricted movement due to the pandemic during 2021. The uncertainty of the situation has affected me a lot of impact on my well-being, so I consider this method of drawing to be part of the recovery to give focus, discipline and purpose to myself. I did some process of experimenting first before fully committing to this new body of work. Initially, I tried using different types of pens and surfaces to produce these drawings. After successfully finding a suitable pen to use in the course of this body of work, I started painting on an A5 sized soft-covered sketchbook. Then I started to switch to A4 sized sketchbooks mostly for the 'speculative drawings' that I had built up before. Every morning I would prepare at least one drawing and then I would take pictures to share with some of my close circle of friends. My intentions are to get responses and comments from them to further improve the drawings and explore new ideas. Some of them suggested changing the pen colour, paper colour and so on. I told the audience this was the first time this series of drawings were shown at the presentation at the seminar hall of Don Orione Cultural Center, Venice, Italy.

1. https://aabaakwad.com/homepage/

2. ‘Narrative Healing’, for panellist information aabaakwad.com/current-gathering/(Mei 1, 2022)

3. Sejarah Tamadun Alam Melayu-Asal Usul melayu, Induknya Di Benua Sunda by Zaharah Sulaiman, Wan Hashim Wan the dan NIk Hassan Shuhaimi Abdul Rahman, 2016. Sundaland: Tracing The Cradle of Civilisations oleh Dhani Irwanto, 2019.

4. Elias Yamani Ismail, “Extending Ideas: Understanding Bricolage Perspectives and Phenomenon,” Journal of Applied Arts Vol. 1 (1): 11-14.

Is 5am morning or night? It was dark outside. Does that have a bearing on that dilemma? I'm not sure.

I'd not been to Ipoh (Perak, Malaysia) since my old mate Jules had flown over to visit his father's grave in God⁶s Little Acre, Batu Gajah. That was way back in 2017. It's now 2024. Jules has since joined his father, not in Perak but in whichever haven old white lovers of Asia go to when they die.

At the start of the journey, and in my naivety, I had expected some Bogartian quip, perhaps regarding buckling up, bumpy rides and whistling, but no. This was Malaysia. Different culture.

In total, it took just over two hours and a half to transverse the Malaysian North/South Highway, then the back roads, from Kuala Lumpur to Ipoh. We’d edged alongside the undulating mountain range which dissects the Malay Archipelago (the Titiwangsa Mountains), oil palm plantations and, in-car conversations which had, inevitability, revolved around food and kopi (coffee). Both of which Ipoh is famous for. Round about the halfway mark, we lapsed into silence with only the music from the car’s tyres accompanying our journey.

By 7am, and just outside of Tajung Malim, the day was thinking about dawning. Roadside trees were silhouetted as we passed countless long distance haulers making their way up country. The distant mountains had gained little roseate clouds, like hats. Maybe I was excited, or just bored, but I fancied myself jumping up and down like some animated donkey and shouting “are we there yet?”. We weren't.

A cloud covered mountain guided us through romantically morning mists harbouring coconut and banana trees, at Sungka. Then through to Sitiawan, Perak, for breakfast at a rural ‘kopitiam’ at Nan Wah Kopitiam (1976). For those unfamiliar with the term, a kopitiam is in Malaysia is usually referred specifically to Chinese coffee shops; food is usually exclusively Malaysian Chinese cuisine. I opted for Mee Rebus, a kind of Indian ‘mee’ or noodle, with a thick, spicy sauce, accompanied by a local coffee (with condensed milk, because of the robusta beans’ tartness).

“Rebus in Malay means “to blanch”, thus mee rebus refers to “blanched noodles”. Yellow noodles are blanched, and then flavoured with a thick gravy. Locally known as kuah, the gravy is a rich broth of grago (tiny shrimps), flour, sugar and salt. To enhance its flavour, herbs and spices such as lemongrass, ginger and shallots are added to the mix along with meats such as mutton, prawns, ikan bilis (dried anchovies) and even flower crabs.”

It was there, eating, as is the Malaysian way, that I first met the rest of the party I was, ostensibly, travelling to Ipoh with.

As you will be aware, Chinese New Year (CNY) is a big deal in Asia. For some it lasts for fifteen days, and involves trips (such as the trip to Ipoh) to family and ancestral homelands. Aside from the other aspects of travel, like car or public transport, camaraderie, gambling and drinking, for Malaysians food takes on a specific importance. Hence the multiple venues on that day (and the next) of journeying to Bougainvillea

Mee Rebus at Nan Wah Kopitiam, Setiawan, Perak

Mee Rebus at Nan Wah Kopitiam, Setiawan, Perak

Chang Jiang White Coffee

Chang Jiang White Coffee

City (Ipoh), also known for its ‘Pomelo Girls’, ‘Concubine Lane' and for being the setting for Chinese films like ‘Lust, Caution’ (featuring Tony Leung Chiu Wai and Wang Lee Hom, and directed by Ang Lee).

The Nan Wah Kopitiam was just the beginning. Next was Chang Jiang White Coffee (c.1970s), a ‘kopitiam’ where various beverages and snacks (conducive to being in an oldy worldy eatery) were subsequently ordered and consumed. Included, was something called a ‘Wangher Crossover’, which seems to be another term for ‘Cham’ (the Hokkien word for a blend of tea and coffee, aka ‘Kopi Cham’ or ‘Tea Cham’) and thought to originate in Malaysia.

In the evening we’d stocked up on biscuits and dried snacks (including ‘Mini Seaweed Biscuit’, ‘Fimen Crispy Cuttlefish’, ‘Master Looi Soft and Crunchy Chicken Biscuit’ and Yat Fat Crispy Chicken Biscuits’) from the ‘Sin Weng Fai Peanut Candy Shop’. That was after deliciously dining on ‘baby octopus in soy sauce’, ‘Braised chicken’s feet’, ‘deep-fried chicken wings’, ‘Braised eggs and Tau Foo in soy sauce, two different black sauce noodle dishes (Yu Kong Hor and Hokkien Fried Noodle), and a final (somewhat larger and whiter, Kung Fu Chow) noodle dish at Sun Tuck Kee (noodle shop).

The following day, after some mild night-time gambling and beer drinking, we ate breakfast at one of the (if not the) oldest kopitiam in Malaysia - Sin Yoon Loong (established in 1937, and not to be confused with the eldest Railway Coffee Shop - Kluang Rail Coffee, 1938). Sin Yoon Loong had continued to be promoted as the creator of the now famous ‘Ipoh White Coffee’ (coffee beans roasted with [Planta] palm oil margarine, and the coffee served with condensed milk, hence its whiteness). Sadly, that old ‘kopi shop’ (that I knew during my seven year sojourn in Perak), had rested on its laurels, and really didn’t deserve its acclaimed reputation.

We had been looking for a Tau Foo Fah restaurant (Tau Foo Fah [or douhua] is a Chinese dessert

made with very soft tofu, and eaten with a clear sweet syrup). It was closed on the day we were there. Instead, we stumbled upon Concubine Lane, Ipoh, (see above). While once romantically decaying, that lane had been spruced up and crammed with quite inconsequential little garish shops selling just about everything you might never need (like things not at all appertaining to dinosaurs, and which glowed in the dark). The old glamour of the lane had long since disappeared. It, and Ipoh, seemingly had joined the worse aspects of its fellow Malaysian cities (such as Malacca and Penang) in its mistaken Disneyfication quest for the tourist dollar, while in reality destroying any semblance of the romance it may have once had.

And so, back to back to Kuala Lumpur (well, Puchong, Selangor but close enough), and more food along the way. Fish this time.

In and around Kuala Lumpur we can find just about anything Ipoh may have once been able to offer food-wise, without the long car journey. Why car when there is a train between Kuala Lumpur and Ipoh? Because all Electric Train Service (ETS, inter-city higher-speed rail) railway tickets were sold out long before our journey.

Ed

Fish at Lan Je restaurant, Rawang, Selangor

Fish at Lan Je restaurant, Rawang, Selangor

Martin Bradley is the author of a collection of poetryRemembering Whiteness and Other Poems (2012, Bougainvillea Press); a charity travelogue - A Story of Colours of Cambodia, which he also designed (2012, EverDay and Educare); a collection of his writings for various magazines called Buffalo and Breadfruit (2012, Monsoon Book)s; an art book for the Philippine artist Toro, called Uniquely Toro (2013), which he also designed, also has written a history of pharmacy for Malaysia, The Journey and Beyond (2014, Caring Pharmacy).

Martin has written two books about Modern Chinese Art with Chinese artist Luo Qi, Luo Qi and Calligraphyism and Commentary by Humanists Canada and China (2017 and 2022), and has had his book about Bangladesh artist Farida Zaman For the Love of Country published in Dhaka in December 2019.