The Things Are .

Quixotic Editions

way

The Things Are .

(What I think about when I think about architecture - from Air to Zombies.)

Every book about architecture is a form of fiction.

This book was designed and produced with the kind support of Provencher_Roy, which is not responsible for its content.

Quixotic Editions , Ottawa 2025

First published in hard copy as a limited edition.

The Way Things Are

Martin Tite

Introduction

Martin Tite

‘I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means.’ Joan Didion

‘I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means.’

Introduction

I wrote a book . This sounds preposterous to me, but there you go…

Joan Didion

‘I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means.’ Joan Didion

I wrote it because it pleased me to do so, or maybe for the reasons noted by Joan Didion. But also because it felt necessary to do so, and you are reading this because it felt necessary to actualize these thoughts by sharing them.

I wrote a book . This sounds preposterous to me, but there you go…

I wrote it because it pleased me to do so, or maybe for the reasons noted by Joan Didion. But also because it felt necessary to do so, and you are reading this because it felt necessary to actualize these thoughts by sharing them.

There are no particular claims to originality, as I know the ground covered here will have been felt or observed by most practitioners of architecture and written about by others. I hope the subjects are presented in an interesting way that can be enjoyed because it is well written, in the same way I read the restaurant reviews in The New Yorker.

There are no particular claims to originality, as I know the ground covered here will have been felt or observed by most practitioners of architecture and written about by others. I hope the subjects are presented in an interesting way that can be enjoyed because it is well written, in the same way I read the restaurant reviews in The New Yorker.

Having collected this writing in bits and pieces over time, I realized that this diary of confessions, thoughts and remembrances all relate to the ‘operating conditions’ of architecture; and that together they constitute a map describing the phenomena of architectur al culture at this moment . Not as it was, not as we think it should be, not as we wish it would be, but as it seems to be now.

Maybe as well, because design is dead, writing is a way to make an architectural statement that doesn’t depend on desig n , at this moment when knowing how to design (in the ways

Having collected this writing in bits and pieces over time, I realized that this diary of confessions, thoughts and remembrances all relate to the ‘operating conditions’ of architecture; and that together they constitute a map describing the phenomena of architectur al culture at this moment . Not as it was, not as we think it should be, not as we wish it would be, but as it seems to be now.

Maybe as well, because design is dead, writing is a way to make an architectural statement that doesn’t depend on desig n , at this moment when knowing how to design (in the ways

Martin Tite

alized that this diary of confessions, thoughts and remembrances all relate to the ‘operating conditions’ of architecture; and that together they constitute a map describing the phenomena of architectur al culture at this moment . Not as it was, not as we think it should be, not as we wish it would be, but as it seems to be now.

Maybe as well, because design is dead, writing is a way to make an architectural statement that doesn’t depend on desig n , at this moment when knowing how to design (in the ways

The Way Things Are we do) seems to be an impediment to doing what is necessary in architecture

And, finally, I have stopped pining to be the kind of architect that I simply can’t be in this time and place. Instead - this book is what I can do - here and now

Martin Tite 2020 - 2025

The Way Things Are a

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Air

When you think about it, buildings are mostly air. They look solid from the outside, but they are in fact honeycombs designed to encapsulate volumes of air that people can fit inside of. Like a space capsule!

Some architectures make something of this fact, with lots of glass, exposed floor slabs and the like; facades that are skins stretched over a structure; like a soap bubble. Some architectures are essentially cellular, as in traditional load bearing wall construction. But in both cases, they are still mostly air.

Very rarely, architectures have no air, as in the case of temples and monuments. They are solid; and inhabitation of these buildings consists of climbing them, like pre-Columbian temples in Mexico and Central America. Or they are almost solid, like Egyptian pyramids pierced with passages and chambers.

Sometimes the air in a building is delimited by an overhanging roof or courtyard walls that claim a territory of air; an invisible force-field that you can only feel.

For us, today, the practical point of creating all of these volumes of air and delimiting their bounds with something solid is that building volumes delineate legally definable areas, conditioned to moderate the environment, and leased or sold, or supportive of the agendas of institutions.

So that the value of architecture is, in large part, based on the volume of air the building captures. Like the way a container is

Martin Tite The Way Things Are

really about the space it creates, rather than its sides; this compared to our collective fixation on what the vessel looks like in lieu of what it can hold.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Alex and Tony

On the occasion of the death of Tony Griffiths. Tony died last week, and Alex died 5 years ago. They had a lot in common.

• They grew up as architects in London, working together for a time at Powell and Moya.

• They both emigrated to Canada and came to Ottawa, for different reasons.

• They thought that teaching architecture was a noble profession.

• They were never able to accept the idea that a poorly made building was acceptable in any way and continued to think of Europe as a place where high quality buildings were possible - compared to ‘North American crap’.

• They didn’t pay much attention to money - because they felt that what we were doing was more important than making money.

• They thought that people were more important than money.

• They thought poetry was something valuable and worth knowing.

• They thought highly of art and artists - as people that could show you things and touched what was important in life.

• They were passionate.

• They believed in things and fought for the architecture they believed in.

• They were principled.

• They helped other architects who were sometimes their competitors.

• They believed in the profession and made significant contributions to the profession through volunteer work .

• They spoke up for the things they believed in.

• They were not calculating in their opinions.

• They thought that architects had a special role to make the world a better place.

• They worked best for people that had the same outlooks.

• They managed to make a place in practice that survived and succeeded in spite of a generalized hostility to their values.

• They often saw a commission as a battle against the mediocre.

• They valued handmade drawings, and beautifully made things.

• They admired youthful innovators.

• They saw the practice as a kind of family.

• They were against the corporatization of the profession.

• They enjoyed laughter in the office.

These kinds of architects aren’t around anymore.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Always already an architect

I somehow stumbled into this profession but I was always already an architect.

Insights and feelings from childhood make my becoming an architect seemingly inevitable in hindsight.

My first aesthetic experience. Driving up a mountain with my father on a gravel road to the top where a radar dome was located. This was 1962. Everything absolutely new and white and as foreign to its setting as the moon lander at Tranquility Base. All around hills for as far as I could see - all covered in trees - evergreens - so green - without sign of human effect. And somehow that feeling of the gravel road, the long view, and the pure white walls, and the white geodesic dome and the silence - all of that experience never forgotten - why?

And the fascination with making spaces that could be inhabited. Snow forts, tents, hiding places amongst tall reeds; and building steps and platforms between the towers of drying wood at my uncles’ lumber mill. And being fascinated by the idea of a tree house as big as a house - with platforms, and trunks and views of the world around. And Lego... making models of houses and imagining how you go from one place to another.

And the B asilica in St. John’s - seemingly a whole world cont ained inside; arcaded spaces mysterious and with purpose that I didn’t understand but felt. The feeling of being completely alone in this space of exploration.

A warm summer evening, I am probably 3 years old. I wake up and go to my parents’ bedroom. They’re not there. I go downstairs looking for them - not there either. I conclude that they must be outside - so I leave the house from the front door - looking around - going to the back of the house - looking around. Lying in the damp grass, waiting - it’s quiet - maybe a train in the distance, the streetlights. A feeling that is full of the mysterious quality of being alive, being a witness to what is, alone but not afraid at all.

And being fascinated by the spaces between things - the point where chemistry becomes biology.

And always being interested in many different things; science, art, landscapes, ships.

And the German pavilion at EXPO 67 - a thing like no other.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Architects and Engineers

Some of my best friends are engineers!

We work hand in hand - but we’re very different.

Architects tend to make their concerns on a project as big and complicated as the client will tolerate. Engineers tend to make their concerns as small as can be calculated with certainty.

Architects have wants - that sometimes conflict with the wants of clients. Engineers just want to get the job done.

Architects want to be famous. Engineers don’t think about that.

Architects are activists. Engineers are usually passive - they react to a technical challenge posited by others (and when they are more than passive calculators, they irritate architects).

Clients don’t challenge engineers - because clients don’t understand the math. Architects’ math is grade 8 level and ‘anyone’ can judge architecture.

Engineers are more or less satisfied with their professional lot in life. Architects are always more or less dissatisfied.

Engineers are all about things that are practical. Architects ’ worst failing is being impractical.

Engineers can be dispassionate about the work and free from design ego. This is a position to be envied.

Architecture or revolution

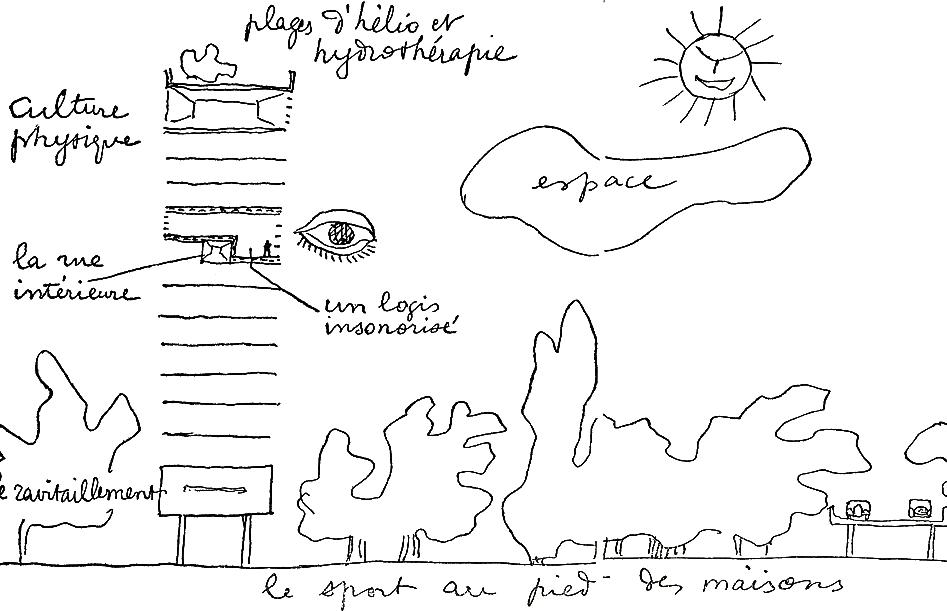

When Le Corbusier said ‘architecture or revolution’ he identified a profound fact, that there is a relationship between architecture and society. But for Le Corbusier, instead of architecture being a product of a social/political realm, the social/political realm is a product of architecture!

Someone once told me that if you want to change your work you need to change where you work.

Architecture is conditioned by its environment. Certain kinds of architecture are possible in New York, but not possible in Ottawa. And the reverse is true. These conditions are external to architecture; the imperative of profitability, the systems that govern architecture, the strictures of professional associations, zoning by-laws, client base, cultural outlooks, etc.

The kind of architect I am and the kind of architect I have been made into is, in part, a function of the fact that I work in Ottawa. Actions that have been successful in Ottawa (success being repeatable) have continued and others have not survived to be repeated.

I don’t want to denigrate the agency of the individual architect or firm, or the possibility that there can be exceptions to the rule, but the overarching fact of an environment exerts a constant force on architectural practices in that environment.

Environment is not entirely a phenomenon of physical location, for example, there is a cultural environment that the ‘big-name’

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

firms practice in, made up of client groups that seek to obtain status for their projects by hiring signature architects to create novelties, hence BIG.

If we want to change architecture, we have to change the environmental conditions for architecture. This might mean political action or fulminating revolutions that will alter the conditions that precede architecture. There are examples where this has happened; the sustainable design movement, and the regulations of the built environment that enabled accessibility.

Small revolutions in architecture are possible and necessary and achieved incrementally.

The Way Things Are

Art and Architecture

Art and Architecture

Architecture is plumbing. Richard Serra

Architecture is plumbing. Richard Serra

The American sculptor Richard Serra has abruptly pulled out of a project to design a massive and much-debated Holocaust memorial in Berlin. Mr. Serra, who had joined with the American architect Peter Eisenmann to submit a design that was strongly favored by Germany's Chancellor, Helmut Kohl, said he had quit for ''personal and professional reasons'' that ''had nothing to do the merits of the project.’ New York Times, June 4, 1998

The American sculptor Richard Serra has abruptly pulled out of a project to design a massive and much-debated Holocaust memorial in Berlin. Mr. Serra, who had joined with the American architect Peter Eisenmann to submit a design that was strongly favored by Germany's Chancellor, Helmut Kohl, said he had quit for ''personal and professional reasons'' that ''had nothing to do the merits of the project.’ New York Times, June 4, 1998

Sometimes architects aspire to be artists, and sometimes artists want to make architecture, and sometimes the two of them shouldn’t get mixed up with each other.

Sometimes architects aspire to be artists, and sometimes artists want to make architecture, and sometimes the two of them shouldn’t get mixed up with each other.

Maybe because I am an architect, it seems to me that architecture is often a companion of art; as either a subject, the situation for making art (the studio), the places for displaying art, or art practices that create spaces and places.

Maybe because I am an architect, it seems to me that architecture is often a companion of art; as either a subject, the situation for making art (the studio), the places for displaying art, or art practices that create spaces and places.

There are any number of significant exceptions to this notion of art’s companionship with architecture (Offhand I can’t think of any work by Picasso that encounters architecture.) but it seems that, for many artists, architecture is present in some way.

There are any number of significant exceptions to this notion of art’s companionship with architecture (Offhand I can’t think of any work by Picasso that encounters architecture.) but it seems that, for many artists, architecture is present in some way.

I am thinking of people like:

I am thinking of people like:

• Ed Rushea, who inspired Robert Venturi,

• Ed Ruscha, who inspired Robert Venturi,

• And obvious examples like Richard Serra who created conditions that are architectural (because they involve the relationship of the body to space),

• And obvious examples like Richard Serra who created conditions that are architectural (because they involve the relationship of the body to space),

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Or the application of art practices to the design of buildings - like Vito Acconti,

Or the work of Christo and Jeanne-Claude,

Or the photography of Bernd and Hilla Becher,

Or the building projects Donald Judd made in Marfa Texas,

Or Andy Warhol’s movie of the Empire State Building,

Or Gordon Matta-Clark’s actions,

Or Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty,

Or Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés,

Or the paper spaces of Thomas Demand,

Or ‘City’ by Michael Heizer,

And the work of James Turrell,

And there are many others….

Now, to be sure, an artist’s engagement with architecture rarely includes grappling with the multitude of ways of thinking and making that architecture involves. And so, almost always, artist’s idea of architecture is selective, almost never dealing with plumbing, or other practicalities of accommodation and durability and cost and weather tightness and engineering that are associated with building projects larger than gazebos. In this regard, perhaps Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s work comes closest to the condition of architecture, given the machinations of engineering, public meetings, financing and approvals his work attracted.

So, while architecture is a kindred of art, it is only so in some limited and specific ways. Art is not architecture, as architecture is not art.

If I think back, it seems that the phenomena of the artist as architect might be a feature of art of the last 60 or 70 years. Certainly landscapes, cityscapes, buildings and interiors are historically, in themselves, an important subject for painting and graphics, when not being the setting for renderings of Kings and Queens and dignitaries and families and angels and the denizens of paintings by Edward Hopper. And historically, figures such as Michelangelo practiced in both domains, but I don’t think artists thought about architecture/environments as something they would make or comment on as artists until maybe sometime around Kurt Schweitzer’s “Merzbau”,1923-37, or the gallery installation by Marcel Duchamp, “Sixteen Miles of String”, 1942, which can be seen as examples of some sort of collective realization of the potential of art to explore the condition of person in environment.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Assholes

I would have been a more ‘successful’ architect if I had been more of an asshole.

But it’s just not in me to be the kind of person that forces my will and wants onto a client - to the detriment of my career.

Those headstrong, I don’t give a shit what you want, bridge burning, alienating, misery making, demanding, insulting architects that operate with a bullheaded tenacity, sometimes get some pretty good stuff done – compared to what my ‘easy to get along with’ accommodations yield.

There are some architects that see a project as a battle between their wants and everyone that might thwart those wants. Conflict as design process. And this strategy sort of works for them. The work is ‘pure’ and garners awards and speaks to the personality of ‘the famous architect,’ who gets then more work out of this strategy.

But in my experience, there’s lots of times when the creative tension with the client makes the solution better than I would have made myself. And oddly, the more I honour the specifics of a project, the more it looks like a work from my hand.

I have had the unpleasant experience of encountering the occasional architect/asshole. And I’ve got to say they give me the creeps – and they’re always awful to work with! The odd thing is that these assholes are typically very successful - which is puzzling as I can’t imagine who on earth can stand working with

them - or pay them money for the opportunity to hang around them through the design process.

But I suppose there are clients that simply don’t care about that, or they are assholes themselves and can understand and identify with the unwholesome motivations of the asshole.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Authorship in architecture

Neil Armstrong was always very clear that the achievement he participated in was not his, but rather the product of the work of thousands.

But we continue to pretend (for some reason, marketing?) that architecture is the product of singular genius, contrary to the reality that it is typically the product of thousands of people, and processes, and all sorts of conventions and methods.

Some architecture is ‘supposed’ to be the product of a genius. After all, that’s what museums and other status seeking entities are buying. But the vast majority of buildings are the result of forces and mechanisms completely separate from the ‘author’ and to think of them as the product of an author is a kind of blindness, and not very useful.

The credit roll ending movies is the way authorship in building production actually works. The producers, directors, show runners, actors, best boys, craft services, etc.; all have analogous existences in the practice of architecture.

Design can also be a sort of relay race, moving from the napkin sketch to the preliminary design to design development, to contract documents, to construction, to commissioning, handing off from person to person as the work progresses; each stage authored by a different person or team.

And the increasing number of specializations in architecture makes authorship even less clear. Lighting, acoustics, building

code, door hardware, envelope, security, programming, sust ainability, heritage, law, spec writing, BIM, interiors, campus planning, project management, (I could go on….) occupy a territory once exclusively held by architects. Every one of them has a degree of agency in the design. Over time, there has been a progressive devolution of building authorship from the individual towards a network of areas of expertise that come together to realize a building, and then dissolve.

I think that ‘I’ designed the building, that ‘I’ was its author, but really what occurred was different from that. (Buddhists know that there is no ‘I’.) My actions were conditioned by environment, including history, the indoctrinations of architectural culture, the things we think we know. If this was not the case, I would be able to design something completely independent of these environmental conditions. But I can’t. As much as Christopher Wren couldn’t design the Barcelona Pavilion.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Autobiography of a building

I came into being – I don’t know how or why.

Water was my constant enemy. I shielded myself from it as I was able, and for the most part I was successful. But the threat was always there. Water was always able to find a way to penetrate my defenses and so my insides and outsides suffered stains and rust and various degradations in its wake.

I was always at risk of other calamities – being set on fire, tossed around by winds or shaken to my core by the movement of the earth I stood on.

Over time, I suffered various amputations and extensions –which altered my personality as much as a lobotomy might. But I was also cared for and sometimes loved.

They would make me whole, the beings that occupied my inside. I needed them as much as they needed me.

The Way Things Are

cho i ces

The Way Things Are

Choices

Design is a matter of making choices. For even a modestly scaled project, a design involves thousands of choices, the size and arrangement of spaces, the finishing of the door hardware, the make-up of the roof, the selection of the toilet, etc. I can tell you from experience, it’s exhausting! And amongst the thousands of choices made, a few are bound to be wrong, either discovered during construction – or by the occupant post-construction.

The odd predicament of design is that we must make choices in the absence of a logical path towards arriving at a conclusion. And the design process is full of non sequiturs; for example, we might need to choose between good windows or an elevator.

There is almost no way of knowing if the choices we make are right or wrong. If we’re lucky we realize wrong choices have led to a dead end, if we’re not lucky, they get built.

There is a kind of designer that is self - assured, and confident in their choices . They take their wants and ideas to be selfevidently correct because they themselves thought of them. They will use expressions like, ‘it seems to me that….’, or ‘I wanted to ….’. In these cases, the design is really about the mentality of the designer. Design as the product of the irrational. Interior designers are comfortable in this realm.

There is another kind of designer that feels the need to distance themselves from their choices. And to argue that the design is a pure consequence of factors external to the designer. A lot of

Tite

Martin Tite

modernist architecture was about this logic of design. Design as a product of the rational.

And there is a kind of hybrid designer that has their wants, but achieves them by stealth, wrapping up choices in the cloak of reason. A lot of so-called ‘high-tech’ architecture was like this, where apparently rational thinking somehow inevitably ended up making something that looked really cool.

These comments are not a criticism of these architects or kinds of architecture, but rather a taxonomy of the procedures enabling design.

The Way Things Are

Collaboration is a word architects use to make everyone feel good about obeying them.

Colour in architecture

Architecture has always had a tangled relationship with colour – which is often nervously considered by architects because it has the power to obfuscate form (like spangle painting of battleships) . Form is presumed to be the actual stuff of architecture - factual and objective compared to perceptual and subjective. (Interestingly, Le Corbusier employed colour throughout his oeuvre – for example the chapels at La Tourette – which is not surprising since his architecture always considered subjective experience.)

One of the reasons that modern architects had ‘a hard time’ with colour was that the books promulgating ‘the modern movement’ mostly used black and white pictures so - for ‘second’ and ‘third’ generation modernists - colour wasn’t part of the mental landscape of ‘good design’. Colour was also ideological and associated with ‘honestly’ portraying the ‘nature of materials’. This meant that individual functional elements (wall, structure, roof, glazing etc.) were distinctly hued and ‘coded’ according to the material used for each function. This logic in contrast to the use of decorative materials – like wallpaper.

I visited my friends’ project (Atelier Big City) and realized that they used colour as an integral part of architecture, in service of tectonic identity. This being different from:

• colour as a consequence of material (green copper, red brick, buff stone, grey concrete, silver shingles etc.

• colour as a choice for a building (Mies using black or white)

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

• colour forced on the architect (the way that some materials like spandrel glass don’t have a ‘natural’ colour –forcing the architect to pick one)

• colour applied after the fact of design and construction (the way that any number of brutalist buildings have been brutalized by paint!)

Looking at most cityscapes, the pallet of most buildings sits in a range between the buff/grey tones of stone and concrete to dull brick reds and browns. This compared to the thrilling moment when buildings are, for a few weeks, bright green or pink because of the colour of sheathing or insulation. I wonder what cities would look like if every building was permanently so coloured –and I wonder what would have happened if by some quirk of physics concrete was – say – lavender.

Compliance

In order to be built, every design must be compliant.

Designs that are non-compliant do not get built.

Compliance has many dimensions:

• Compliance with functional requirements (such as the area and organization of spaces or the provisions of various fitments),

• Compliance with social expectations (houses are ‘supposed’ to have three bedrooms, a kitchen and living room and 1.5 baths and look like houses),

• Compliance with the financial means of the client,

• Compliance with laws and regulations,

• Compliance with contemporary aesthetic standards,

• Compliance with architectural mores regarding ‘good design’ (the way architecture is ‘supposed’ to be),

• Compliance with physics (gravity, material strengths, flow dynamics etc.),

• Compliance with the whims of important people,

• Compliance with the capacities and norms of the construction industry,

• Compliance with the ideology of the entity that is sponsoring the building.

I could go on.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

In a sense then, a building is a model of the conditions within which it came to be. And its realization is a validation of these conditions. The authority of the fact of a building’s existence and its physical presence asserts the legitimacy of these conditions.

In this way, buildings are fundamentally conservative, because they validate the status quo of power structures and the networks controlling building production.

Of course, compliance is sensible and practical, and it makes life as an architect a lot easier. I am struck though by the unquestioning willingness of some practicing architects to simply comply with whatever strictures are placed on them. This is not surprising for old architects invested in the status quo and with bills to pay, but puzzling in young architects who decline their opportunity to be revolutionaries.

We can compare our contemporary conservatism to the tendency of previous generations of architects to resist compliance. This was done through writing, exhibitions, paper architecture (as it was called), hypothetical projects and the occasional experimental building (supported by an ‘enlightened’ client with a willingness to put money into a building the likes of which never seen before in the hope of realizing a situation not possible by complying with accepted norms). In this later case I am thinking of Paolo Solari/Arcosanti, the Eames house, early Foster projects, Stirling’s Olivetti building and the like, but that rebellion is over.

Resistance against compliance is possible but typically marginal. It still happens today, but is largely a performative gesture, without any expectation of provoking actual change.

Consciousness

Consciousness is a consequence of lived experience.

Lived experience is (partly) a consequence of the situations and conditions engendered by architecture.

Architecture is a device that constructs states of consciousness.

Control (my way or the highway)

Our architecture is infected with the ambition to achieve perfection (compared to the Chinese idea that 80% right is economically optimal because of the effect of diminishing returns).

One of the occupational hazards of being an architect is the habit of continuously and perpetually searching for flaws whenever observing a building; the unresolved detail, a lack of consideration, shoddy workmanship, and the like; which make it hard to simply enjoy what is right about a building.

The ideal of perfection (the expertly resolved detail, the smooth and unblemished surfaces, the elegance of the plan, and the like; endlessly strived for, and almost impossible to achieve) comes along with the need of the architect to have complete and absolute control of the architecture of their building.

Control over the design

Control over its detailing

Control over its inhabitation (through the selection of furniture for example)

Control of the presentation of the architecture

Control of the narrative about the project

This logic of control extends into the photography of architecture, where the image is perfectly balanced, the light and shadows artful, nothing is misplaced, and elements extraneous to the message of the image are eliminated; the children’s toys,

the unwashed dishes, the laundry etc. (Our idea of ‘good architecture’ is, in part, an idea about good photography.)

For some architects, being in a position of control is the most appealing thing about the profession. The controlling personality is common in a certain kind of architect, necessary to realize the singularity of vision that makes a project notable. Consequently, the egotistical, demanding, unreasonable, architect is often a creature of ‘good design’.

But, to have absolutely everything in a building conform to the way it’s ‘supposed to be’ when it’s finally built is an extraordinarily difficult thing to do. Our instruments of control are remarkably crude, some drawings and specifications for a completely unique assemblage of parts, the exact like of which ha s never been realized, sponsored by someone most concerned about time and cost, designed by a team that may not share the same goals, put out to tender and awarded to the lowest bidder, with trades that are competent, or not, while trying to ensure your firm doesn’t go bankrupt. This is not a recipe for success! Like trying to paint a miniature with a mop.

I have been practicing for decades and I’m still not good at achieving perfection! But then again, is perfection worth aspiring to?

Perfection also means the elimination of the contingent, the arbitrary, the temporary, and the accidental, which are in fact necessary features of life.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Craft

Crafted things are almost always beautiful and if they are not, they are at least interesting to contemplate.

In an economy dominated by machine made things, hand crafted things are mostly seen today in shops that sell expensive amusements - divorced from the ordinary use value / economic logic that objects commonly have For example, the ceramic piece that can’t practically hold anything and is difficult to clean - priced 500 times what a bowl might cost in a shopping centre.

There is a category of architecture that has been entranced by the idea of craft – the unique, material focused, perfectly resolved work that aspires to be a beautifully crafted building. I am thinking here of architects such as Shim-Sutcliffe or Tod Williams/ Billie Tsien and the like.

Architects’ idea of craft is limited to what they can conceive of during the design phase, so when we talk about craft in architecture, it is as if craft is entirely the domain of the designer’s interest in finicky details and beautiful materials, rather than the capacity of a trade to execute - or the potential of trade’s craft skills to contribute to the project.

And what never gets reported about beautifully crafted buildings is that they are extremely expensive. Expensive to build and expensive to operate and expensive to design. ( A well - known architect told me that he realized to his horror that the fees that he charges for custom houses are about the same, on a square foot basis, as what most people expect to pay for a house.)

I’m conflicted. On one hand, “What an amazing and wonderful building !” On the other hand, “ Is this really where money should go?”

The Way Things Are

decadence decadence

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Decadence

It must be a legacy of Catholic guilt - but I’m very uncomfortable with the endless proliferation of magazine spreads on luxury houses and apartments. The bespoke projects that require years of attention by teams of expert designers engaged at an enormous cost, flown in to attend to the site wherever it might be, and budgeted at 10 or 20 or 100 times more than a ‘typical dwelling’ might cost. (Curiously – these bespoke projects rarely possess original thinking. The same beautiful, glassy, woody, concrete, exposed structure, nice-millwork, Architectural Digest stuff that keeps circling us like the great pacific plastic dump.)

At some point – I think this is undeniable – the cost and intellectual labour that goes into an architectural project slides into decadence. It’s just wrong - isn’t it?

Maybe luxury houses might be ‘forgiven’ for their cost when they somehow advance the culture of architecture - or teach us about some hitherto unknown formal invention - or achieve the status of WORK OF ART - or their beauty alone justifies their existence, or if they serve as a testing ground for ideas that might have more general value

But we’re architects - we like nice stuff, and we admire the boldness of clients and the skill of their architects, and the capacity of a building industry to realize these amazing fripperies. And we enjoy the audacious. And we are titillated by t he unconventional. Most buildings aren’t extraordinary - nor can they be - and maybe they shouldn’t be. But we get bored with all of that.

Design as commodity

There used to be something called a ‘nickel plan’, which was a simple plan diagram that would show how program could be accommodated on a floor plate, with a fee based – you guessed it – on five cents a square foot. This is design as commodity.

There are two poles to design - as we understand it today. The kind that is customized, ‘innovative’, expensive, unique, that we typically think of as ‘architecture’; and the kind that applies standardized solutions using proven and familiar technologies, cost effective and representative of common practice, that we think of as ‘not-architecture’ or just ‘building’.

The former is taught in schools, the latter is not.

In general, architects feel like they are ‘doing architecture’ when they are working on the expensive bits of a building, and simply grinding away on standard solutions for the parts of the building that should be as cheap as possible - say the loading docks or the janitor’s closets - that are virtually identical no matter the building. In this later case, design becomes a commodity because there is no particular reason to select one designer or another, except cost and some basic reassurance that the architect knows what they are doing.

Every building employs elements of ‘architecture’ and ‘commodity design’. For example, the elaborate lobby that creates an image for the apartment building that is otherwise totally generic. Or the museum project that uses a conventional roof assembly. Or the warehouse that, despite its prosaic nature, is somehow infected with architecture.

The Way Things Are

In the former case of ‘architecture’, professional fees are relatively high; as necessitated by the need to spend lots of time doing product research, the cost of developing and testing dozens of options, the embracement of complexity, and detailing everything to a high level. In the latter case of ‘commodity design’, professional fees are relatively low, and design work trends towards standard solutions that are well understood by the construction industry.

Commoditization has entered the procurement of professional services – so that we regularly see requests for proposals that consider fee as 30% or 50% or even 100% of the evaluation. And while this is dispiriting to architects, because it says that we don’t add anything of value to a project, it is perhaps an accurate model of the client’s outlook. The client doesn’t need or want ‘architecture’.

And it seems worth noting that there is generally more money for the architects ‘doing architecture’ rather than doing ‘commodity design’. And I wonder how much of the continual striving to make ‘architecture’, that most architects are burdened with, is also a way to achieve strategic objectives outside of the project, or architecture itself, making more money, establishing and maintaining brand, developing the portfolio for the office, achieving some notoriety/status, etc.

Design is dead

I am bored with the predictability of even the very best architecture we make. The ‘interesting moves’, the promise of a wonderful world, the skill of the execution.

Design is dead. Of course as a practical matter there will be a continuing need for buildings and objects to be configured to suit various demands. But what I mean here is that design as a force for liberation or becoming has been supplanted by design as signal. A signal of the presence of the designer. A signal of taste. A signal of status. A signal within culture by the players in the game. A disguise of the reality of a project. Forms that are designed to be ogled by people ignorant of architecture (a populism of a sort).

Design used to be the solution. Now it’s the problem.

By this I mean that there is something wrong with the way architectural design culture is currently configured or at least as it is popularly represented. ‘Design’ per se, is no longer the prime affective plane for architecture – having been taken over by various crisis – environmental, social (housing), medical (COVID) –that have impacted architecture in profound ways outside of what we traditionally think of as the territory of ‘design’.

The culture of design - as currently configured - is problematic in a way that threatens its legitimacy as a practice. Design is no longer a challenging or enabling force in culture; but rather now, amid these crises, a plaything for bored architects, or a spectacle, or the validation of the status quo. Design is no longer a

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

subject for civil engagement or the result of intelligent thinking - but rather the action of a personality who isn’t interested in me, and who I in turn couldn’t care less about.

We attend to various dimensions of architecture, ‘good design’, sustainable design and the like, and sometimes we advocate for social justice in architecture. But these are fragmentary and reactive to conditions ‘outside’ of architecture (is there an inside?).

All of these ‘good’ and ‘interesting’ and socially responsible architects, and the architecture they make, seem to me in some way irrelevant to this moment.

We operate with comfortable presumptions that make things easy for everyone involved, the designer, the client, the builder, the authority, etc. Everyone. We exist in a system of thinking. We are largely unaware of this fact of our mentality, and therefore unable to act on it.

But further, the way our design culture is configured is part of the indoctrination I assimilated about how to think about architecture. And so, I am disabled from any ability to ‘get past’ design, as much as a writer can’t get past words.

Am I saying I don’t want to be an architect anymore?

Dirt

Buildings are made from dirt, or rather, they are made from things extracted from dirt. Stone, mud, lime, iron, silica turned into glass, limestone into cement, and the trees that grow in dirt that give us wood.

Vegetable mineral animal. Buildings come from the first two but almost never from the later. (Although I remember being amazed to hear of Siberians using the tusks of woolly mammoths to build dwellings, and Philip Johnston’s bathroom finished in leather.)

Buildings are remarkably crude - at least as material artifactscompared to the sophistication that we see in contemporary technologies. The chips that will hold a million transistors. The promise of quantum computing. The incredible works measured in the size of atoms. All the things created in laboratories and clean rooms, whose existence is almost invisible to lived experience.

This represents a great divergence from a time when construction technologies were on par with those of science and engineering.

So, what to make of this dumb stuff we mush around with our hands? Unlike the most sophisticated technologies we have, the stuff made from dirt still has the ability to configure the way our bodies situate themselves in a place.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Do-gooders

Q. Did you think we were going to change the world? A. Yes

We were trained to be ‘do -gooders’; people that understood things (the importance of context, the history of architecture, the social value of design etc.) and as a result could and would act correctly and do good in the world.

And once we got into practice, we tried and tried, every time, and over and over, to ‘do the right thing’; even if our clients didn’t want us to.

This ethic of doing the very best you can for the good of the world - is somehow embedded in the idea of being an architect. Every project a chance to make the world better through the means presented by the opportunity of the project. T his ‘do - gooder’ ethic i s related to William Morris , echoing into the present.

In some projects there’s no expectation that the building should make things better ( at least in the way architects want ) and maybe there’s something to learn here - but it’s a scary notion! If we aren’t doing ‘good’, are we doing ‘bad’?

Certainly, for many practices and for most projects, the question of ‘the good’ in a project is what the client thinks the good is; making a profit, complying with regulations, creating useable space, or complying with social expectations as necessary for the building to be accepted. There are many rebuttals to this line of thinking, but these are typically in the territory of the

‘demonstration project’ or acts of subsidized design charity. But the occasional school in Africa designed and realized with good intentions will not alter the fundamental geometry of the production of building construction in that part of the world, nor the need for education there.

Notwithstanding all this - I can’t imagine not being a ‘do-gooder’ architect. It’s the way I think about things.

There is a class of types of architecture that don’t concern themselves with doing good, namely the formalisms that are about giving expression to an abstract design idea, or an intellectually interesting proposition. This outlook on architecture has resided with any number of architects, whose design practices are, on the surface, unrelated; the New York Five, Aldo Rossi, Herzog & de Meuron, Valerio Olgiat and others, where architecture is an autonomous/self-referential practice, in some ways independent of time or place - which is liberating, but is it good?

Dream Home

What a strange idea. As if somehow this aspiration - sometimes realized - exists somewhere other than waking reality.

How many times have stories about the dream home been repeated? The story of the dream home occupied for a matter of a year or two - or not at all. Or the story of the dream home built for love Or the story of the dream home that becomes an obsession. Or the dream home that’s a comical rebuttal to the idea of perfection (leaky roofs, cold rooms, hot rooms, doors that won’t open or close, the battle that Edith Farnsworth had with Mies).

The dream home occupies the territory of imaginary places. Where, for once, everything is good and right forever, where the home somehow meets your every want, where you are finally at peace, where you finally get the good thing s you deserve , where you become yourself ; all in all , a stand - in for heaven, another imaginary place.

The dream home is never a typical apartment, or one half of a duplex. It is almost always in a remote location (or at least a location that is very private) - away from the possibility of interference from neighbors. So, dream homes are often built on islands of land, preferably actual islands, or hundreds of feet above the street. Remoteness, to be able to be completely alone, seems to come along with the notion of the dream home.

The dream home idea also seems bound up with the idea of luxury - or a certain idea of luxury. The large, the expansive, the

showy, the costly, the perfectly realized. A modest and affordable apartment, no matter how well it is designed, can be loved, but it’s never a ‘dream home’.

The idea of house in popular culture is tied up with the wish that somehow the house will be a dream home, as manifest by the pitiful advertisements in newspapers that suggest that each and every one of those track houses contains some part of the essence of the dream home, or the contests offering as a winning prize ‘your very own dream home!’

The Way Things Are

efficiency

The Way Things Are Martin

Tite

Efficiency

Not to denigrate the real ways that different contemporary cultures promote building projects and engage with architecture, but you would think that different political and economic systems (say American, Russian, Chinese, or those of other democracies and dictatorships) would engender substantively different kinds of architecture, as different as vertebrates are to invertebrates, but they don’t.

They are all bound together with a logic of efficiency, and technologies that are international in scope and application. In some fundamental way , they are all the same because they are all rooted in realizing the most economically efficient way to achieve a practical end. Of course, there are exceptions – for example when decorum or marketing considerations demand conspicuous ‘waste’ - or when a client wants to elevate their status by patronizing the list of 40 or 50 ‘signature’ architects hawking their wares around the globe. But for the most part the key design driver is cost efficiency , which tends to push designs into shoe boxes (decorated as need be - as Robert Venturi observed).

This ideology of efficiency infects ‘common sense’ views about the ways buildings should be. (‘Wasted space’ is a common phrase that carries this presumption.) It is self-evident to most that ‘efficiency’ is good, and ‘inefficiency’ is bad. That it is not only stupid to be inefficient - it is also somehow profoundly wrong.

This ideology also ties into the logic of commercial development whose purpose is to make profit or the logic of public works

Martin Tite The Way Things Are

which demand that limited financial resources be husbanded with care. A climate of scarcity that demands we get ‘bang for your buck’.

I am not arguing that we ‘waste’ money. But for an ethic of architecture that understands cost efficiency as a practical requirement of architecture, rather than the purpose of architecture.

And looking forward, we are heading to a future of ultimate efficiency that removes the slowness and desires and pleasures of human labour – software deciding what should be built, software deciding how it should be designed, robots producing buildings – all untouched by human hands.

Our ultimate desire is for the world to proceed without the necessity of our presence.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Everyone’s a teacher

Architecture is a team sport.

It requires a diversity of skills, knowledge and kinds of intelligence, and ages too.

When I was in school, the faculty at the school of architecture seemed invested in being authorities, whose authority rested in age or education. They spoke - we listened.

I don’t feel that way. To me , a n architectural practice is like a baseball team where the roles of the team members are very different - but each one is essential to the success of the team.

And of course, it’s commonplace that the younger you are the more savvy you have regarding software - the great leveling where the old depend on the young.

As a principal in my firm, I enjoy the capacity of each person in the office to contribute to our collective enterprise, but also each person’s ability to be a teacher for all.

It could be simply a matter of knowing more about a project than anyone else does, it could be a matter of showing others how to engage with clients, it could be leadership by example (the person that comes in on a weekend without being asked), it could be a kind and friendly attitude brought to a business that is often tough.

And we should be prepared to admit that others – outside of ‘the fold’ of architecture – can be teachers too . The client that challenges you – the ‘civilian’ from the public that has a fresh perspective.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Expensive paint

A colleague once referred to the application of different kinds of facade treatment on a building as ‘expensive paint’. This was a smart observation of the recent tendency to animate facades with arbitrary fragments of building fabric.

The design strategy I am describing is the form of decoration that uses fragments of the stuff buildings are made of to animate designs (rather than the decorative programs employed in premodern design) a chuck of curtain wall here – some metal cladding there – brick elsewhere. It’s also decoration of a purposeful aimlessness that attempts to simulate the effects of time, seeking the pleasing variety of traditional urban environments.

Of course, the purpose of all this frenetic ‘animation’ is to disguise the fact that the offices are all the same, the apartments are all the same and that our buildings are fundamentally about multiplying the value of real estate.

This phenomena of ‘expensive paint’ exists because we lack design vocabulary (based on tradition or pragmatism) that will enable the ordering an otherwise flat façade in a satisfying manner; compared to pre-modern architectures based on tradition, load bearing elements and materials that - at least to some degree - were inherent to expression.

Older buildings had decorative ‘programs’ that developed a coherence of beginning and middle and end; or moods solemn, glorious, calm, playful, restrained or exuberant; or with allegorical/symbolic resonance through reference to tradition or nature;

often organized through the principle of symmetry. This was a serious task, not a matter of throwing stuff at an elevation. But it also depended (my untested hypothesis) on a collective that could ‘read’ architecture; compar ed to our current situation; which understands the meaning of architecture to be found in deviation from shoe-box buildings.

The curious thing about these buildings using ‘expensive paint’ is that they appropriate the actu ality of the tectonics of architecture, walls, structure, encl osure, openings (that used to be based on ‘facts’ or ‘function’) and apply them randomly, thereby divorced from use value. This design strategy is a parody of architecture where the appearance of things is exaggerated to effect. For example, sunshades applied to opaque portions of facades.

This all is enabled by the contemporary logic of detailing. A rain screen over an airspace can be metal, wood, glass, brick; anything you like. There’s almost nothing in principles of decorum or the technical requirements of a facade design that tells you what it should look like. A wad of brick can be applied to the 40th floor of an office building if that’s what you want to do. It’s just a rain screen.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Extract from a (failed) proposal

for the rehabilitation of the Carleton University School of Architecture (Building 22)

We will be working with people that will be passionate about this project, in part because they are architects, in part because they are students of architecture, in part because the stakeholders that use the building have universally understood the positive effect that the design of the original school has had on the culture of learning and life in the school.

In this context the conversations will be charged and perhaps have a political dimension.

The design matters in a profound way to life and learning at the school - and the prospect of altering the status quo comes with the risk of ‘not getting it right’ or destroying the attributes that have make the school an icon to several generations.

The project has the exciting potential to re-vivify the building facility in ways which will positively impact the culture and pedagogy of the school as much as the original Carmen Corneil design did.

Part of the work should be directed towards the question of the value of restoring features of the original building, such as its original lighting, or concrete surfaces marked by paint. Building 22 was fragile in some senses, and vulnerable to changes that compromised the character and quality of the environment, perhaps in part because the industrial expression of the building

was mis-understood to be a evidence that ‘design’ was not a concern because the building was apparently utilitarian, and perhaps as a mark of the relative status of the school of architecture within the administration of the university.

Building 22 is grounded in ethics. An ethic about the beauty of the ordinary. An ethic about frankness of expression that grounded the building into the reality of how buildings are made. An ethic about fostering community and the street as the nexus of community. An ethic about spontaneous use, happy accidents, impromptu meetings. An ethic about the project of a building making the spaces around it better. An ethic about enabling connections. An ethic that says that exposing the ‘truth’ about construction is a moral obligation.

These ethics are also perhaps the evidence of a way of thinking - but one whose origins are from the past. Life and architecture have changed in 50 years. We are compelled and obligated to test the validity of the values the school was designed around. Are they universal and timeless? If not, how should we update them?

A humble attitude will be required by those contemplating changing the design of the school - which offers so many lessons to generations of students and practitioners.

The project will be a time to raise and address questions. The original design envisaged a program built around day lit studios with drafting boards. If these conditions no longer exist as they were, what is the idea of a studio today?

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Judging the past by the standards of the present is unreasonable. Building 22 comes from an era of cheap energy and ignorance of the impending climate crisis. The risk of achieving the sensible goal of improved energy efficiency for Building 22 is the potential to destroy the cultural value of the building artifact and the (still) novel character of the building that attracts and retains students.

The design emerged as well from the 1960’s, a time that was willing to take risks, desirous of challenging orthodoxies, expansive and optimistic. The school is evidence of that time. What is the right attitude today? Is it possible to have one?

The project is about potentials. The latent potentials inherent to the structure and building fabric, the potential to integrate forward looking technologies to support the work and living environment of the school, the potential to create new and exciting approaches, the potential for our studies to precipitate gifting and financial support by founders, the potential to align the facility design (conceived as a building for baby boomers) to the needs and ambitions of today’s generation, the potential to realize aspects of the building (such as the clerestory window over the street, originally conceived but not executed), the potential to right some wrongs that have been imposed ad hoc on the building over 50 years of inhabitation, the potential for the project to integrate itself with the students own studies on the building, the potential for students to learn from our work and our work processes and the potential that we will learn by working with students and faculty.

The situation/opportunity is inherently challenging - in an exciting way. We need to attend simultaneously to urbanism, building technologies, spatial requirements, the ideology of expression of architectural technology, the rehabilitation of a significant piece of architecture, the social/political dynamic of working with the university administration, faculty, students and other stakeholders, the need to plan for phased implementation, the need for solutions to align with a viable financial model, and the obligation for the design to be a statement about architecture that specifically addresses itself to architects and students of architecture.

There are fascinating opportunities for the project to actively engage with the learning that students do - in fact this is essential. The school building was conceived of as a platform for learning about architecture and this rehabilitation project is an opportunity to be a platform to learn about engagement, the design processes (which we intend to make transparent to students - perhaps they can be invited to attend coordination meetings which would ordinarily be held in camera), contemporary building systems, sustainability, and heritage rehabilitation.

The idea of the ‘unfinished’ building that is open to change and the agency of students is important. It raises the question of how to rehabilitate a heritage building whose ethic was based on the need to be an open-ended solution - the school never ‘finished’ or embalmed in a fixed state - but a continuing cultural/pedagogical project. The idea of extending this ethic forward and enabling the active occupation by students and faculty will be crucial. So, the building is an armature, and this attitude may be the beginnings of an idea of what is to be done.

The Way Things Are f

fam oussss

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Famous architects

Thinking about the ‘famous’ architects that I have had occasion to meet…

They almost always - at some point in the conversation - note that they have just won an award or that they are on track to win one. It seems odd - surely - after all their success they don’t need the validation of another award - but they seem to. I find it touching that they put any stock at all in these things.

It bears noting that one does not become a ‘famous architect’ by accident - or simply with talent. You must want to be famous - as much as an athlete must want to win a gold medal at the Olympics. 80-hour work weeks - tireless self-promotion - speaking at conferences - endless miles in airplanes - bad hotel food - getting published - social media... It’s a lot of work! But work that doesn’t have much to do with the value of being an architect.

To me at least, this striving for power within the culture of architecture is demeaning to architecture itself. As if you and your wants are more important than architecture. And you willingly participate in the charade that maintains your status; where ambitions for oneself swamp whatever ambitions you might have ever had for architecture.

Maybe these ‘blindnesses’ are a prerequisite to becoming a ‘famous ’architect. If they understood the futility of this game, would they still play it? If they understood that their building was after all, really, and only, just a building, would they be so invested in it being exactly the way they want it?

What are famous architects like?

• They are sometimes quite incurious about other architects. Their thinking and their practices are totally centred on themselves and what they personally think about architecture. Is self-centredness necessary to join the pantheon of the great ones? I don’t think so. The very best architects are fans of lots of other architects.

• They sometimes see themselves as the heroes of the story.

• They see everything through the lens of architecture. As if everything can be understood as a kind of architecture. Bu t there is a strange innocence to the fact they are incapable of seeing otherwise.

• Some of them are cynical manipulators - I am sad to say.

• Some of them are true and earnest believers, thinking that they have somehow found ‘the right way’ - not understanding (or maybe they do) that the only reason they get work is because social or political decorum demands that they – or another of their type - be hired to conjure a bobble for the edification / entertainment / seduction of their audience.

• They are always supported by a variety of un-famous ‘backroom’ players. But they rarely speak of them as collaborators or contributors.

Those of us who have been in the profession long enough, know who these ‘back-room’ players are - and we give them the complete and deserved respect that comes from the fact that:

• They have to be highly skilled to somehow realize these projects.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

• They have to be highly skilled to somehow realize these projects.

• They go about this work without the slightest hope of personal recognition.

These ‘un-famous’ people give honour to the profession.

First job after school

At my interview for my first job after school:

Barry (trying to make me less nervous): “We have a minimum height requirement.”

Me: Too nervous to laugh.

At the same interview.

Barry: 'What salary are you looking for?'

Me: "Well, Alex Rankin is paying a classmate $10 an hour." Barry offers me $8 and I gladly accept it.

Me trying to help Gord - insisting that I could detail a window into a wall. Gord fixing it after my attempt.

Barry gave me a small addition to do. One day the owners call up. I t doesn’t look like the picture!” Anxious call with the builder, Al Bateman, I think. We go to the site. Barry looks at the roof line and then gets up on the roof with a chain saw and cuts back the offending part, assuring the owners it will look fine. In the car on the way back, Barry explaining to me the fundamentals of the geometry of sloping roofs. No anger.

Working with Gord in the little space we shared. Me incessantly complaining about how messed up everything was in practice. Gord explaining to me that the sharp edges in school get rounded in practice.

Barry giving me a series of tasks to complete at city hall - assuming - wrongly - that I have a grasp of the workings of plan examiners and the planning branch. At that moment City staff were

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

in some temporary space - I think on Nicholas street - and they were faced with a somewhat clueless kid asking questions that he didn’t understand. Then me coming back to the office…

Barry: Did you get x?

Me: No.

Barry: Did you see y?

Me: No, he wasn’t there.

Barry: What about z?

Me: I’m not sure.

Barry: They’re on Nicholas?

Me: I went to the right building!

Barry: Laughter.

Me working on the site plan for Rideau Gate. There are two surveys and at some point, I discover that the survey I was using was the wrong one. Barry calling the client and explaining. Lesson learned.

Some small little thing comes into the office. I think a fluff up of a pizza place entrance. Me screwing up somehow but excusing myself because ‘it’s not an important job’. Barry: "Every job is an important job."

Nancy suddenly softening when she found out that I had a tumor that I needed to go to the hospital for. “Are you okay hon?”

Found Design

Why is it the designs we find always seem better than the designs we decide to do? Why is it that some designer’s favorite things are not designed?

I am thinking of the way modernist architects were inspired by designs free from the guile of culture and felt to be perfect because of this; The Bell helicopter in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Frank G ehr y wondering why the tract houses looked so good before they were finished, Jim Stirling referencing images of warehouses, Le Corbusier and grain elevators, etc.

The appealing and exciting naturalism of modernism seems to come from the possibility of a direct connection to the world as it is, untainted by any want to style, an authenticity that came from the way things are.

Compare to the present moment, where designs are anchored by the wants of the designer as author, or, alternatively, the product of ‘objective’ analysis that no matter how ‘objective’ somehow always leads to a design more or less conventional in their application of design principles, design organization and styling.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Frank

It’s odd to me, these quibbles about Frank Gehry’s stuff. He is who he is, he does the things he does. The work is completely enmeshed with him as a person. The thing that I enjoy about his architecture is the way the work is the product of a completely unique sensibility . Only Frank does Frank. And in a way, if you don’t like the work, you don’t like him. Maybe this is why a reporter got the one finger salute!

To expect that he is going to change somehow in response to criticism seems wrongheaded. If you want him to change his design approach, you’re asking him to change his own humanity.

He seems authentically himself as a person and an architect and I think his work achieves an authenticity because of this fact.

His work is often about a feeling, a sort of interior narrative. Things that make you wonder and imagine.

They have personalities. The chunky forms, the shimmering surfaces, the joy of materials, the oddly matter-of-fact treatment of certain elements, the whirling sheets and complex geometries, the compositions of forms… all come together in a way that only he can do.

And he is endearingly open about things, the screw - ups, the clients, the budgets. Maybe because he’s sort of untouchable? Us mortals are not able to say these things out loud.

While the notion of ‘schools’ or tendencies in architectural thought seems to have dissolved, I don’t see any evidence of a school of design following on from Frank Gehry the way that the ‘heroes’ of modernism, left in their wake hundreds of acolytes emulating ‘the masters’. It is almost impossible to imagine Ghery’s firm continuing in any meaningful way following his passing. He is sui generis. There are no followers. His unique design sensibility seemed to come out of nowhere, except maybe the character of Frank Ghery or Los Angeles itself.

Great architects are the ones that show us new ways of making architecture, and by that measure Frank Gehry is a great architect.

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

From the extraordinary to the ordinary

It’s really kind of inevitable, that every firm founded by a design leader seems to suffer.

Amongst ‘good’ architects, the identity of the firm is traditionally synonymous with the identity of the design leader. Witness the examples of Rem Koolha a s, R ichard Meier, Zaha Hadid , Norman Foster, Richard Rogers (Whereas many contemporary firms are now named in ways that speak to themselves as corporate entities independent of individuals, firms with names like Core or UN Studio.)

Within the past decade or so, many of these ‘name’ firms have gone through a transition from the absolute control of their namesake founders to a more widely held responsibility for design within the eponymous firms that have corporatized their practices. This is a practical feature of the transition from the small firm doing ‘interesting’ work to the large firm, doing perhaps less interesting work that is infinitely more ambitious in scale and requires the discipline of management structures to operate effectively and profitably.

This pattern of transition is also necessitated by the fact that people don’t live forever, and because the ‘name’ firms need to migrate to a dispersed ownership in order to attract and retain competent senior architects. Unlike firms such as that operated by Le Corbusier which vanished with the death of the sole owner.

In some cases, design leadership has passed on to a new design leader, in other cases design leadership has become diversified amongst a wider retinue of leaders - often operating with some autonomy, notably in the case of OMA.

A pattern of these transitions is that design quality tends to drift from the extraordinary towards normal sensible ordinary professional competency, or rote repetition of past successes, as it is diluted by the weakening influence of the living personality of ‘the master’. In the worst cases, the architecture parodies the work that the firm became known for.

Clearly the hand of ‘the master’ matters to some firms and is not readily transferable. (This contradicts the assertion, held by people that think about management, that all we need is a good process to create good results.) This is a problem when the subjective quality of the design firm’s work is bound up with the subjective character of the aforementioned persons.

The three letter firms (HOK, IBI, SOM, HDR, KPF) and the like (Gensler, Perkins & Will etc.) do not suffer this condition because they were never really about the qualities or character of an individual design personality - with the design leadership in these companies - founded in the first instance as partnerships - widely distributed and readily replaceable with equivalent competencies. In these firms ‘the designer’ (3 or 4 steps below the CEO) Is brought out like a trained bear to perform and to assure the client that ‘good design’ is at work, proven by the ample application of ‘features’ extraneous to the actual purpose of the building, supported and validated by the narratives

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

‘ the designer ’ c oncocts, populated by ‘ inspiration s’ a nd diagrams that coerce acceptance by making the solution appear necessary and inevitable.

Fuck all

As a student, everything seemed to be a kind of architecture or had some parallel to architecture. Obviously, this outlook had a lot to do with my own myopias and complete immersion in the school environment.

Notwithstanding my personal and lifelong commitment to architecture, I came to realize that there are many things in the world, many truly important things, that have fuck all to do with architecture. Say for example, the love of a mother for a child.

And, as well, I came to realize that my ideas about architecture were very different from the many people I engaged with. I saw every project through the lens of making a ‘good’ design - or at least one that was sufficiently different from the norm that it would hold my interest.

I thought everyone should already know that design was important (and that the ones that didn’t were somehow ignorant or morally defective) , and slowly realized that others thought other considerations were equally or more important, and that these outlooks were entirely reasonable and valid; the cost that made the building affordable, the schedule that demanded the project be ready on time, or other considerations that meant that my design wants often really truly had fuck all to do with the actual drivers of the project.

The Way Things Are

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Gold plated toilets

I remember a colleague remarking on the dilapidated condition of a federal minister’s office. It was a relic of the 1970’s, because each new minister was afraid to be criticized for the cost of a renovation; the attention the subject would attract inversely proportional to its cost

Buildings are very expensive. But most people don’t understand how expensive they are. We regularly embark on projects that cost one hundred million dollars and more - which is amazing compared to my daily life that is concerned about paying more than $100 for a nice meal.

I remember as a recent graduate being shocked at the thought of a cost of $100 a square foot for a house, imagining a room covered in 100-dollar bills spaced 12 inches apart. And today that rate is comically low. Even a modest home requires decades of work to pay off, and while the press is a-twitter with the cost of big - budget movies, there’s probably 4 or 5 similarly costly building projects going on at any time in my mid-sized city.

I understand why our public clients are nervous about endorsing projects that cost anything more than the cheapest conceivable first cost for a structure that complies with code. Almost every time they do so, someone will say it costs too much, the press will leap on it, and politicians get asked awkward questions. The result is a fear of the quality that a well-made building costs, and endless discussions within the bureaucracy on how to ‘message’ initiatives so as to avoid criticism.

This problem seems to be mostly a feature of projects that are of a scale that most people can understand. A service building on a nationally significant site for $8 million - all costs included - a horror! (Meanwhile civil engineering projects that cost 100 times as much and go 50% over budget get done without notice or comment.)

Public buildings are the playthings of politicians trying to score points - enabled by a ‘gotcha’ press that enjoys this sort of thing because it attracts eyeballs. (One of the most common tropes in the popular press’s relationship to architecture is the story about overspending on publicly funded construction.) The irony is also that the public bodies that care about culture and design and the public servants that want to do well for citizens are the ones that get the grief. So, we are in this absurd condition where no good deed in architecture is unpunished.

The Way Things Are

The Way Things Are Martin Tite

Handmade drawings

It will be difficult for many to comprehend how we actually accomplished this, but until about 1990 we made all our drawings by hand, aided by a variety of tools and mechanical devices.

This craft-based production of drawings (each a unique original that had to be safeguarded because it was simply the only one there was) has been entirely replaced by our current regime of infinite reproducibility, changeability, and transmissibility, accompanying a logic of ‘information management’ as design.

Making drawings by hand came along with a whole retinue of devices that constituted a universe of things of architecture that are no longer needed, but that I still miss.

Set squares (transparent plastic triangles, in colours clear or orange).

French curves with fascinating geometries.

Scales of various increments that came in various three-sided rules that had six scales (1:100/1:10, 1:50/1:25, 1:20/1:5 for example). These would usually be marked by the owners’ initials, because we were expected to supply all of our own drafting tools, like trades people.

Adjustable set squares.