T H E M A G A Z I N E O F T H E G E O R G E C . M A R S H A L L F O U N DAT I O N H o w C h u r c h i l l a n d M a r s h a l l Wa g e d Wa r M a r s h a l l a n d t h e E a r l y Co l d Wa r G e o r g e C . M a r s h a l l , S e c r e t a r y o f D e f e n s e M a r s h a l l i n R e v i e w T h e L a s t Wo r d S U M M E R 2 0 1 9 V O L . 5 , N O . 1

p h o t o c r e d i t G e o r g e C M a r s h a l R e s e a r c h L i b r a r y

Features

How Churchill waged war with Marshall: The view from 10 Downing Street

By Allen Packwood, MPhil (Cantab) FRHistS

4

Pack wood draws upon Sir Winston Churchill’s own papers and related collections from the Churchill Archives Centre to examine the challenges and tensions behind Prime M inister Winston Churchill ’s and G eneral G eorge C. M arshall ’s war time relationship “A key difference bet ween Churchill and Marshall,” Pack wood stated, “is Churchill is in office and fighting the Second World War for more than two years before Pearl Harbor.”

Marshall and the Early Cold War

By Melvyn P Leffler, Ph D

12

Leffler explores George C. Marshall’s role in decisively shaping the contours of the early Cold War and how, by employing strategic insights from World War II, Marshall shrewdly assessed the threat posed by the Soviet Union, set priorities, and designed the strategy that established America’s preponderant position in the international arena. Dr. Leffler also assesses Marshall’s enduring Cold War legac y.

George C. Marshall, Secretary of Defense 1950-1951 20

By Allan R Millett, Ph D

Millett discusses Secretar y of Defense George C Marshall’s coalition of civilian and militar y defense officials that suppor ted the State Depar tment and President Truman’s determination to limit the Korean War and their common goals of establishing a firm national commitment to strategic nuclear deterrence and for warding collec tive defense Dr M illett examines how Marshall and his associates succeeded in achieving these goals despite the opposition of a group of isolationists and “Asia First ” members of Congress.

S U M M E R 2 0 1 9

V O L. 5, N O. 1

M A R S H A L L is the membership magazine of the G eorge C. M arshall Foundation. We encourage reproduction and use of ar ticles contained herein, with per mission. Direc t cor respondence and requests to the G eorge C. M arshall Foundation, P.O. Box 1600, Lexington, VA 24450.

Telephone: 540-463-7103

Website: w w w m a r s h a l l f o u n d a t i o n o r g

Membership information is available on our webs i te. Yo u r m e m b e r s h i p s u p p o r t s p ro gra m s a n d a c t i v i t i e s d u r i n g yo u r m e m b e r s h i p ye a r B y renewing your membership, you help us perpetuate the legac y of the man President Harr y Truman called “the great one of the age.” As the keeper of the flame, the Marshall Foundation preser ves and co m m u n i c ate s t h e re m a r k a b l e s to r y o f t h e l i fe and times of George C Marshall and his contemporaries. I t has become a unique, national treasure wor th protec ting at all costs That ’s why your membership is so impor tant.

We gratefully acknowledge financial suppor t from FedEx and from Clifford Miller Yonce and The Miller Fo u n d a t i o n f o r u n d e r w r i t i n g t h e co s t s a s s o c i a te d with production of this issue.

Contributors: Russ Fletcher, Allen Pack wood, Melvyn Leffler, Allan Millett, David Hein, John Wranek , Paul Barron, and Cathy DeSilvey D

•

• Legac y Series on the Road: FDR and Marshall: The Men Who Saved D -Day

• Calendar for the Legac y Series

30 Marshall Shor ts

• Marshall Awards to be presented in November

• Best New Books

32 The Last Word

Front cover image: This photograph on the cover is Secretar y of State George C Marshall leaving a press conference at the Moscow Hotel The photo is from the Marshall-Winn Collection, taken by photographer

Thomas McAvoy for LIFE magazine, April 1947

M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G

e p a r t m e n t s

Welcome

Marshall

3

26

in Review

David Hein reviews Steil’s new book

28 Marshall Legac y Series

welcome

It is my sincere pleasure to welcome you to the Summer 2019 edition of Marshall One of the true pleasures of my role as Acting President is interacting with and getting to know the many scholars who conduct research and lecture at our librar y.

In this edition, you will hear from three of them First, Allen Packwood, who heads the Churchill Archives Centre and is a Fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge, presents us with a view of the Churchill-Marshall relationship from Winston Churchill’s perspective e relationship between the men was respectful but tense in its early stages due to differences in strategic outlook. However, with the passage of time and the change in Marshall’s role from chief army officer to leading diplomat, Churchill’s view of Marshall’s abilities evolved significantly. Second, renowned Cold War scholar Dr. Melvyn Leffler develops a portrait of Marshall as a nuanced strategist, someone who not only helped initiate the Cold War but also played a leading part in the planning that ultimately won it. And third, our nation’s foremost expert on the Korean War, Dr. Allan Millett, writes about the short but highly consequential tenure of Marshall as Secretar y of Defense, perhaps the most challenging of the three major positions that he held in public ser vice. Marshall played a critical role in establishing NATO, shaping the Universal Militar y Training and Ser vice Act and bolstering support for the Truman administration’s global security policy in the MacArthur-Far East hearings I wish to thank Mr Packwood, Dr Leffler and Dr Millett for their efforts in producing these delightful and highly informative essays for our magazine and for their enduring support of the Foundation

In closing, I feel compelled to comment on the photograph on our front cover. Since “George Marshall and the Cold War” has been the predominant theme of this year ’ s Legacy Series lectures, it seems particularly appropriate to lead with this image of Secretar y of State Marshall exiting a meeting at Hotel Moscow in winter 1947 It was on the night of April 15th of that year that Marshall had his fateful meeting with Stalin in the Kremlin ere he concluded that the Soviets intended to thwart at all costs U S initiatives to stabilize and revitalize the economies of wartorn Europe Ambassador Robert Murphy later claimed, “It was the Moscow Conference which really rang down the Iron Curtain ” Soon thereaer the Cold War would move to full throttle

I am both happy and proud to report that much of the information that follows draws from materials held in our archives, the preser vation of which is allowed by your continuing generous financial support ank you, and enjoy this edition of Marshall

Cordially,

Russ Fletcher, Acting President

Russ Fletcher, Acting President

S U M M E R 2 0 1 9 3

“Churchill… advocated a policy of gradual persuasion by his team when dealing with the Americans, likening it to ‘the dripping of water on a stone.’”

4 M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G

p h o t o c r e d t G e o r g e C . M a r s h a l R e s e a r c h L i b r a r y

How Churchill waged war with Marshall: The View from 10 Downing Street

BY A L L E N PAC K W O O D, M P H

(

N TA B ) F R H I S T S

In the fourth volume of his war memoirs, published in 1951, Churchill describes his reaction to a document drafted by General Marshall: I t e x c i t e d m y a d m i r a t i o n . H i t h e r t o I h a d t h o u g h t o f

M a r s h a l l a s a r u g g e d s o l d i e r a n d a m a g n i f i c e n t o r g a n i s e r a n d

b u i l d e r o f a r m i e s … . B u t n o w I s a w t h a t h e w a s a s t a t e s m a n w i t h a p e n e t r a t i n g a n d c o m m a n d i n g v i e w o f t h e w h o l e s c e n e .

It is a quote that was published with the benefit of hindsight, aer the storm of war had passed, and once Marshall had indeed established himself as a great figure on the world stage. Churchill was no doubt keen to emphasize that he had foreseen the qualities that had assured the general’s rise to secretar y of state

e reputations of both Churchill and Marshall were now secure. eir postwar correspondence is largely warm, friendly and personal: congratulations on birthdays, promotions and honors, and exchanges of gis, such as the painting of the Atlas Mountains that Winston (now back in 10 Downing Street) presented to the general in 1953 Marshall held his major post war offices between 1947 and 1951, when Churchill was out of office, and was then in retirement during Churchill’s second premiership. ey settled into a rhythm of friendship and mutual admiration, untroubled by the complications of representing competing national interests

is had not a lways b e en t he c as e dur ing t he S e cond World War, however Churchill might choose to spin it.

In 1947, his friends like Averell Harriman had to go on the offensive against suggestions in the American press that Winston had opposed the selection of Marshall as the President’s preferred commander for operation O verlord, the Allied return to France in 1944. e problem was that Churchill could not simply give a straight negative to this allegation.

…Harriman had to go on the offensive against suggestions in the American press that Winston had opposed the selection of Marshall as the President’s preferred commander for operation Overlord.

For, as he explained in his private corresp ondence, w hile he had not b een against Marshall

is article is a summar y of the author’s lecture for the “Friends” in High Places sequence delivered in November 2018 You can watch Mr Packwood’s talk as well as other Legacy Series lectures on our YouTube channel

5 S U M M E R 2 0 1 9

I L

C A

Winston Churchill, British Prime Minister, pauses in front of 10 Downing Street to give the “ V sign” of Victor y, 1943.

p h o t o c r e d t r o m t h e c o e c t o n s o t h e I m p e r i a l W a r M u s e u m s

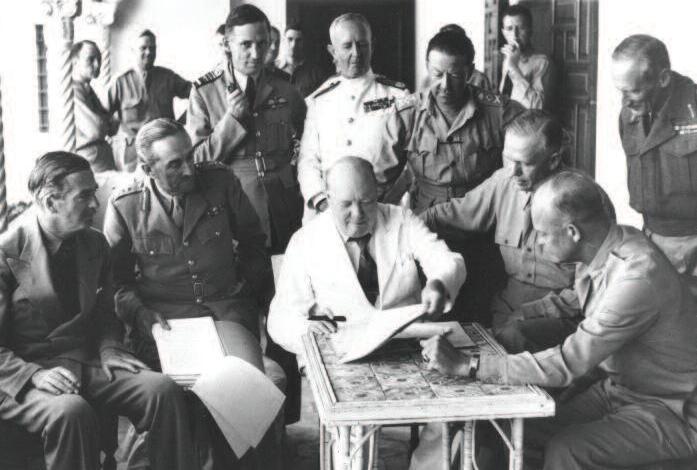

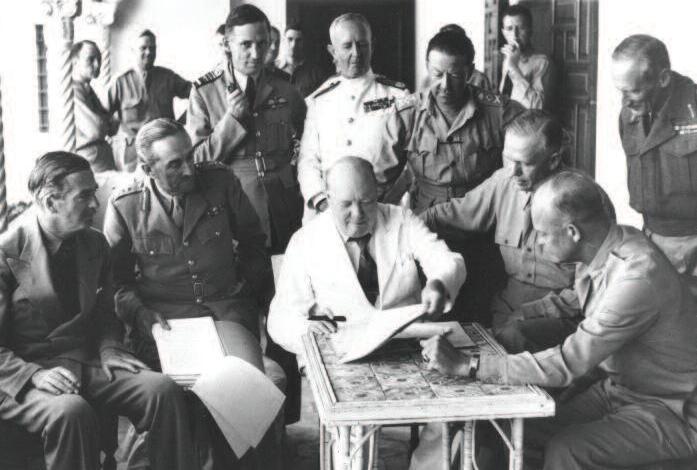

Opposite page: A planning conference at Allied Force Headquarters, 1943.

commanding O verlord, he had b een against a suggestion by Ro os e velt that Marshall mig ht become a Supreme C ommander in the European eatre and take responsibility for the largely British armies in Italy as well as those forces crossing the Channel. Such a suggestion went to the heart of arguments that had been raging between the British and Americans since 1942, over where the Germans should be fought and who should control the Mediterranean (both during the war and aer wards). It is a debate that had its origins in British strateg y prior to Pearl Harbor.

He had famously promised the British people victory –‘victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror’ –but how was he going to deliver it?

C hurchil l b e came Pr ime Minister on 10 May 1940, t he ver y day that Hitler launched his blitzkrieg offensive against France and the Low C ountries. Neither he nor any of his inner circle cou ld have ant icip ate d how quick ly t he mi lit ar y situ at ion would deteriorate. He had famously promised the British people victor y –‘victor y at all costs, victor y in spite of all terror’ – but how was he going to deliver it?

From S eptember 1940 London was hammered by the Blitz e city was bombed for seventysix nights, excepting only 2 November. No one knew whether a modern city could sur vive such a sustained and heavy bombardment from the air. Churchill visited the bomb sites. “‘Give it ‘ em back,’ they cried, and ‘Let them have it too ’ I under took for thw ith to see that their w ishes were carried out…” But the question was how?

6 M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G

General Marshall with Prime Minister Churchill on a trip to Salisbur y Plains during London Conference (April 15, 1942)

p h o t o c r e d i : G e o r g e C M a r s h a l R e s e a r c h L b r a r y

Br it ain cou ld not fig ht in France, other than via small-scale commando op erat ions or Sp e ci a l O p erat ions

E xe c ut ive guer r i l l a raids (b ot h of which Churchill encouraged)

e enemy cou ld b e b omb e d, and Churchill started authorizing bombing raids from the moment he was in D owning St re et, but Br it ain lacke d c ap acit y, w hi le t he G er mans cou ld hit t he Br it ish Isles far more e asi ly and effectively.

e one t he at re w here C hurchi l l cou ld t a ke t he fig ht to t he enemy, where he did have troops and a fleet, was t he Me diter rane an esp e ci a l ly once the Italians were in the war As a lifelong Imp er i a list he was not ready to cede the British position in Malta and Eg ypt and Palestine, but he also knew the area well and chose it as a viable battleground His decision was a logical one, but it carried huge implications: It was always going to be difficult to get out especially once the Germans moved down, as they inevitably did into Yugoslavia and Greece

Moreover, resources diverted to the Mediterranean had to be at the expense of other theatres. General Dill as Chief of the British Imperial General Staff (CIGS) argued strongly for the reinforcement of Singapore, reminding Churchill that it had been their polic y to guarantee the defense of Australia and New Z ealand (something Churchill himself had signed up to in the past) but the Prime Minister now argued that Britain had to fight the actual war in front of her, not the hypothetical battle that may not come. And besides, he reasoned, if the Japanese tried to attack in the Far East they would have to go through the American Pacific Fleet, which therefore ultimately guaranteed British security. e Japanese came to the same conclusion and provided their own answer!

Britain could fight in the Mediterranean and maybe preser ve her own position, but Churchill knew that he still ne e de d t he supp or t of t he Unite d St ates if u lt imate v ic tor y and t he defe at of Hit ler were to b e achie ve d

General

From the moment he became Prime Minister, he began a concerted charm offensive, …

“No lover ever studied every whim of his mistress as I did those of President Roosevelt.”

From the moment he became Prime Minister, he began a concerted charm offensive, conducted publicly in speeches and broadcasts, and privately by letter, telegram and private emissar y As he told his private secretar y, Jock C olville, “No lover ever studied ever y whim of his mistress as I did those of President Roosevelt.” At the height of

7 S U M M E R 2 0 1 9

p h o t o c r e d t G e o r g e C M a r s h a l R e s e a r c h L b a r y

Marshall inspects a device that looks like a camera while Prime Minister Churchill looks on during their visit to Salisbur y Plains (April 15, 1942)

Prime Minister Winston S Churchill obser ves a demonstration by the parachute troops at For t Jackson, South Carolina, on June 24, 1942 Left to right: General George C Marshall, Field Marshal Sir John Dill, Prime Minister Churchill, Secretar y of War Henr y L Stimson, Major General Rober t L Eichelberger, and General Sir Alan Brooke

the Battle of Britain, he likened improving Anglo-American relations to the mighty Mississippi, rolling on ‘full flood, inexorable, irresistible, benignant, to broader lands and better days’.

Luckily General Marshall was in agreement. Nazi Germany was the strongest enemy and must be defeated first.

Aer Pearl Harbor, he may indeed have slept the sleep of the saved, but he was also ver y quick to cross the Atlantic and meet with Roosevelt, determined to steer the administration into a Europ e-first p olic y. Luck i ly, G enera l Marsha l l was in ag re ement. Nazi G er many was t he st rongest enemy and must b e defe ate d first. S o far s o go o d, but of cours e Marsha l l a ls o b elie ve d t hat Nazi G er many was b est defe ate d in France by br ing ing sup er ior mig ht against t he g re atest concent rat ion of enemy forces C hurchi l l was a lre ady fig ht ing in t he Mediterranean and could not afford to lose Eg ypt to Rommel. He was only too aware that the Germans had b eaten the British in Nor way, France and Greece, and his own studies of histor y and of the horrors of the First World War had led him and the British Chiefs of Staff to the conclusion that the Allies should fight a peripheral war, on as many fronts as possible, while building up their forces. He did not oppose an assault in France per se, but he did oppose it in isolation and worried about the consequences of it being made too soon

On 8 April, Marshall arrived in London with a letter from Roosevelt: What Harr y and Geo. Marshall w ill tell you about has my hear t & mind in it. Your people & mine demand the establishment of a front to draw off pressure on the Russians, & these peoples are w ise enough to see that the Russians are today killing more Germans & destroy ing more equipment than you and I put together.

ough couched in the President’s informal style, this short and simple message marked the opening shot in what would become a long and complex war of words between the Americans and British on the nature and timing of a second front in western Europe.

Marshall now put his cards on the table. e secret memorandum that he and Hopkins handed over outlined his plan for future operations in western Europe It began with the unambiguous

8 M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G

p h o t o c r e d t G e o r g e C M a r s h a R e s e a r c h L i b r a r y

st atement t hat “Wester n Europ e is favore d as t he t he at re in w hich to st age t he first maj or offensive by the United States and Great Britain rough France passes our shortest route to the heart of Germany.” In eleven pages of typescript it proposed the combined British-American landing of forty-eight divisions on the continent in 1943. is was to be preceded by the buildup of forces and the heavy raiding of the French coast, and was accompanied by contingency plans for a possible “ emergency ” landing in France in 1942 in the event of either a Russian or German collapse on the eastern front.

The problem facing the British was that they could not afford to reject outright the American plan and alienate the President.

The problem facing the British was that the y could not af ford to reject outright the American plan and alienate the President. Yet, if implemented in full, it would mean t hat all Br itish and Amer ican ef for t would b e fo c us ed on a retur n to France. Br itish reinforcements and Amer ican supplies to t he Mediter rane an would have to b e cur tailed, with the result that all there might b e lost, while the British were als o relying on s ome American activity in the Far E ast to pre vent fur ther Japanes e incursions towards India.

And how were American forces to get to Britain and then to France? Marshall admitted to the UK Defense C ommittee that “the main difficulties would be found in providing the requisite tonnage, the landing cra, the aircra and the natural escorts.”

From the British perspective, this meant that no landing in force could realistically be contemplated in 1942, and that losses would be incurred in other theatres during the long delay while forces for a cross Channel assault were built up in the United Kingdom.

Yet Churchill led his colleagues in “cordially accepting the plan,” noting “that there was complete unanimity on the framework” and that, “ e two nations would march ahead together in a noble brotherhood of arms. ” His one and important caveat, and a justification he would use for reopening the issue, was that “it was essential to carr y on the defens e of India and the Middle E ast.” But this did not stop him f rom inter pret ing defens e as offens e and simultaneously pushing the British theatre commander General Auchinleck to take action in the Western Desert. Indeed, he now needed a victor y there more than ever to demonstrate to t he Amer ic ans t he va lue of his Me diter rane an st rateg y, and to eliminate R ommel w hi le American reinforcements and supplies could still be diverted to Cairo

“The two nations would march ahead together in a noble brotherhood of arms. ” His one and important caveat, …, was that “it was essential to carry on the defence of India and the Middle East.”

Churchill’s preference, now endorsed by his colleagues, was for an operation against French North Africa, not least because “ a threat to Rommel’s rear might cause the Axis considerable embarrassment ” Matters came to a head when General Marshall returned to London in July e Chiefs of Staff argued against his plan for an autumn landing on the Cherbourg Peninsula, and then, working with the Prime Minister, presented a united front to the War Cabinet, who dutifully expressed themselves opposed to the American plan for 1942 and in favor of multiple landings on the North African coast. It was the Americans who now blinked. R ather than risk

9 S U M M E R 2 0 1 9

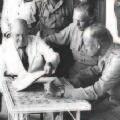

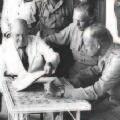

A planning conference at Allied Force Headquarters, left to right: Sir Anthony Eden, Sir Alan Brooke, Air Chief Marshal Tedder, Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, General Alexander, General Marshall, General Eisenhower and General Montgomery

Mr Churchill is in the center (April 6, 1943)

a breach so early in the alliance, Marshall and Roosevelt agreed to delay European operations and give priority to the Mediterranean. In this, they were almost certainly influenced by their own need to divert increasing resources to the Far E ast

And so round one went to Churchill, and ended in Operation Torch and the landings in North Africa. Round two began at the Casablanca C onference in Januar y 1943.

e British arrived with a clear idea of what future joint strateg y should be e diar y of Ian Jacob, one of Churchill’s party, records that:

… our v ie w s we re de f inite at any rate s o far a s the Medite r ranean ve rsu s Nor the r n Euro p e w a s c on c e r n e d . T h e ar g um e nt s in fav our of e x pl oit ing su c c e ss in Nor t h Af r ica by at tacking “the unde rbelly of the Ax i s ” we re , it s ee med to u s , ove r whelming. T he more we looked at Nor the r n France the less one liked it w ith the forces likely to be available in 1 9 4 3 in the U K . T hes e forces would be small for a “ s econd f ront,” and the rate at which the y could be put a shore wa s s e ve rely limited by the lack of landing c raf t.

Churchill recognized that these complex issues would take time to work through, and advocated a polic y of gradual persuasion by his team when dealing with the Americans, likening it to “the dripping of water on a stone.”

e initial Chiefs of Staff discussions proved difficult. Yet, with the help of Field Marshal Dill, w ho had flow n in f rom t he Joint C hiefs of St aff C ommitte e in Washington, and k ne w t he positions of those on both sides of the table, a consensus on future operations was reached by Monday 18 Januar y. e next operations would be the capture of Sicily, while at the same time preparing forces and assembling landing cra in England “for a thrust across the Channel in the event that the German strength in France decreases, either through withdrawal of her troops or because of an internal collapse.” It seemed to be a complete acceptance of the British strateg y and Brooke “could hardly believe our luck ”

10 M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G

p h o t o c r e d t G e o r g e C M a r s h a R e s e a r c h L b r a r y

In agreeing to the continuation of the Mediterranean strategy, the Americans were acknowledging that they did not have all of the resources to meet their existing obligations in North Africa, undertake their favored offensives in the Pacific and simultaneously attack in France. Yet in committing to an attack on Sicily they were also, temporarily at least, further denuding any operation in France of such cra and thereby effectively shelving the plan for any quick offensive or lodgement across the Channel. e “Second Front” in northern Europe had been put back yet again.

Was this an example of perfidious Albion? Of the wicked British tricking the Americans into a strateg y they did not endorse? e truth is surely that strateg y and polic y was thoroughly debated and that in the end both Churchill and Marshall and their respective staffs recognized the advantages and the inevitability of an incremental strateg y that took the fight to the enemy while allowing the Allies to build up their resources North Africa led to Italy, but it remained American polic y to attack in France as soon as this was really viable, and at the Tehran C onference in Novemb er 1943 R o os e velt and Marsha l l dug in, ably supp or te d by St a lin, and Churchill had to accept the curtailment of his Mediterranean strateg y

He did not do so easily. En route to the conference at Malta, he gave a “long tirade on evils of Americans” and felt inclined to say, “all right if you won’t play with us in the Mediterranean we won’t play with you in the English Channel ” And when he complained to Clementine about how terrible it was “fighting with both hands tied behind one ’ s back,” she was wise enough to caution “patience and magnanimity,” reminding him of his saying “that the only worse thing than Allies is not having Allies ”

L ater he would state:

ere I sat with the great Russian bear on one side of me with paws outstretched, and, on the other side, the great American buffalo, and between the two sat the poor little English donkey, who was the only one, the only one of the three, who knew the right way home.

Marshall’s perspective would have been somewhat different His professionalism meant that he never succumbed to Churchill’s courtship, even while forging a rather “special relationship.”

Allen Packwood is a Fellow of Churchill College, Ca m b r i d g e, a n d t h e D i re c to r o f t h e C h u rc h i l l Arc h i ve s Ce nt re. Al l e n wa s co - c u rato r o f

“Churchill and the Great Republic,” a Librar y of Co n gre s s ex h i b i t i o n , a n d o f “C h u rc h i l l : Th e Powe r o f Wo rd s,” a d i s p l ay at t h e M o rg a n L i b ra r y i n N e w Yo r k . H e h a s a l s o o rg a n i ze d m a ny e ve nt s a n d l e c t u re s, i n c l u d i n g t h e s u cce s s f u l co n fe re n ce o n “ Th e Co l d Wa r a n d i t s

Legac y,” at Churchill College in 2009 He is the a u t h o r o f H ow C hu rc h i l l Wa g e d Wa r : Th e M o s t Challenging D ecisions of the S econd World War, and has lectured extensively on Churchill in the United K ingdom and the United States.

11 S U M M E R 2 0 1 9

If Marshall’s actions and calculations contributed to the onset of the Cold War, his more enduring legacy was the architecture that eventually won the Cold War.

M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G p h o t o c r e d t G e o r g e C M a r s h a l l R e s e a r c h L i b r a r y

Marshall and the Early Cold War

BY M E LV Y N P. L E F F L E R, P H.D.

To g r a s p t h e C o l d Wa r yo u m u s t e x a m i n e i t s g e o p o l i t i c a l , e c o n o m i c , a n d i d e o l o g i c a l r o o t s. Yo u n e e d t o s t u d y u n d e r l y i n g s t r u c t u r e s a n d i d e a s. T h e y h e l p t o i l l u m i n a t e p e r c e p t i o n s o f threat and opportunity. To grasp the Cold War – both its origins

a n d i t s e n d – yo u a l s o m u s t s t u d y h u m a n a g e n c y, t h e r o l e s o f

k e y l e a d e r s, l i k e H a r r y S . Tr u m a n a n d J o s i f S t a l i n , l i k e Ro n a l d

Re a g a n a n d M i k h a i l G o r b a c h e v.

In terms of personal agency, my argument is that no single leader exercised more influence on the origins and evolution of the Cold War than did George C Marshall He played a key role in catalyzing the Cold War He also established the strategic architecture that eventually won the Cold War

I will develop these points by first illuminating the geopolitical, e conomic, and ide olog ic a l cross c ur rents t hat existe d in t he midd le 1940s, w hen World War II ende d and t he C old War began to take shape.

…no single leader exercised more influence on the origins and evolution of the Cold War than did George Marshall

In terms of the distribution of p ower at the end of World War II, the United States was the singular global power. Europe was devastated, and Soviet armies occupied half of the continent. Germany was defeated, devastated, and divided into four occupation zones. In western Europe, France, B elgium, Holland, and their neighbors were weakened and demoralized aer years of o cc up at ion by and col l ab orat ion w it h t he Nazis e Unite d Kingdom was v ic tor ious, but financially emasculated and struggling with nationalist movements in key parts of the empire. China, too, was despoiled by the war and engulfed in civil war. Japan was defeated, destroyed, and occupied by U S troops In parts of southeast Asia, the Middle E ast, and Africa, European empires were beginning to erode as revolutionar y nationalist movements gained traction.

American power was unmatched e United States had a strategic sphere of influence in L atin America and a worldwide system of militar y bases e U S Navy controlled the oceans e United States monopolized the occupations of Japan and of Korea, south of the 38th parallel.

U.S. Marines were in north China. U.S. militar y officials ran a key zone inside Germany and

is article is a summar y of the author’s lecture for the Winter’s Coming: e Cold War sequence delivered in January 2019 You can watch Dr Leffler’s talk as well as other Legacy Series lectures on our YouTube channel

Opposite page:

General George C Marshall attends an evening event held during the Moscow Foreign Minister's Conference

13 S U M M E R 2 0 1 9

exercised much influence over the course of events in the entire countr y With its strategic Air Force and a monopoly of atomic weapons, the United States could potentially devastate any adversar y. Notwithstanding the rapid demobilization of its forces, the United States was the only global militar y power, possessing incomparable strategic he coupled with the ability to deploy forces almost anywhere

e United States was not only militarily preponderant; it also enjoyed unparalleled prosperity and wealth. Worries were plentiful about another depression, but America’s relative economic strength was staggering e United States had two-thirds of the world’s gold reser ves, fiy percent of its manufacturing capacity, fiy percent of its shipping, and three-quarters of its invested capital. e GDP of the United States was three times the size of the USSR and five times the size of the United Kingdom

In comparison to the United States, the Soviet Union was weak.

As a result of the war the country was economically devastated and demographically decimated.

In comparison to the United States, the Soviet Union was weak. As a result of the war the countr y was economically devastated and demographically decimated Twenty-five to 27 million citizens of the Soviet Union perished during the war. e Nazis destroyed 1,700 cities and towns; the y demolished 6 million buildings and 31,000 factories; the y wrecked 61 large p ower stations and 3,000 oil wells; the y dismantled 31,000 miles of railroad track and ruined 90,000 bridges; they slaughtered 17 million head of cattle, 20 million hogs, and 27 million sheep U S intelligence estimated that it would take 15 years for the Soviet Union to overcome its manpower losses, 10 years to compensate for its deficiencies in technicians, 5 to 10 years to build a strategic air force, 15 to 25 years to build a navy, 10 years to rebuild its railroad lines, and 5 to 10 years to develop an atomic bomb

e impact of the war on western Europe economically was not so severe as in S oviet Russia, but it was bad. France, B elgium, Holland, and Italy faced a huge task of reconstruction. ey faced grave shortages of food and fuel, and they lacked the dollars to import the resources they needed most Germany, moreover, was economically prostrate Militar y authorities there (and in Jap an) fo c us e d on demi lit ar izat ion and refor m, not on e conomic rehabi lit at ion. When Assistant S ecretar y of War John McCloy visited central Europe in April 1945, he wrote back to Washington: “ ere is a complete economic, social, and political collapse going on in central Europe, the extent of which is unparalleled in histor y. ”

In sum, the international economy was in precarious shape. It was warped by war, fragmented by exchange controls, quotas, and barter agreements, and haunted by memories of the Great Depression of the 1930s.

e economic dislocation, coupled with social miser y, catalyzed ideological conflict It is not an overstatement to say that liberal capitalism was in serious disrepute almost ever ywhere (except, of course, the United States). Capitalism was blamed for the two world wars and the long depression. Pe oples e ver y w here ye ar ne d for refor m, a p oint t hat Amer ic an offici a ls f u l ly grasped Assistant Secretar y of State Dean Acheson told a congressional committee in the summer of 1945: “ ey [the peoples of the world] have suffered so much that they will demand

14 M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G

John McCloy

p h o t o c r e d t G e o g e C M a r s h a l R e s e a r c h L b r a r y

Dean Acheson

that this whole business of state control and state interference shall be pushed further and further ” In France and Italy, the C ommunist Party garnered 35-45 percent of the popular vote; in B elgium, Denmark, Nor way, and Holland about ten percent.

Where communists did not compete effectively, socialists did In the United Kingdom, voters in July 1945 threw Winston Churchill out of power and elected the Labour Party Clement Attlee, the new prime minister, and his followers moved rapidly to nationalize key industries and institute the welfare state. At the same time, Mar xism-Leninism resonated widely among revolutionar y nationalist leaders in Africa and Asia Mar xism-Leninism rationalized away their countries’ backwardness and blamed it on imperial exploitation. Meanwhile, Stalinist Russia embodied a model of national planning that seemed to promise quick modernization and militar y strength.

e peculiar matrix of postwar circumstances conjured up great fear in the United States e United States was incredibly powerful yet vulnerable. Aer all, the S oviet militar y dominated half of Europe. In France and Italy, Communist parties seemed on the cusp of victor y. In Greece, royalists battled communists for control of the countr y In China, civil war meant the communists might emerge victorious and grab power. In Asia, European empires were collapsing. In Germany and Japan, occupation authorities maintained order, but uncertainty about the future was portentous Would U S troops remain? If they le, might Germany and Japan gravitate, however slowly, into an orbit dominated by the Kremlin or its minions?

Harr y S. Truman faced formidable challenges. He had inherited the presidenc y on Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death in April 1945 Roosevelt had never confided in him Truman, more than anyone, grasped his own inadequacies when it came to foreign affairs. “Pray for me now, ” he exclaimed as he took office. Moreover, Truman wanted to focus on domestic priorities as the war came to an end Tr uman chos e James F Byr nes, a for mer f r iend f rom t he S enate and clos e war t ime adv is er to R o os e velt, to b e his s e cret ar y of st ate, but s o on lost confidence in him. roug hout 1945 and 1946, t he inexp er ience d and ins e c ure president conf ronte d massive strikes, spiraling inflation, and espionage scandals “Had enough? ” was the Republican campaign slogan in the 1946 congressional elections Republican candidates wanted to lower taxes, cut spending, raise tariffs, and hunt for domestic spies. ey displayed little interest in foreign affairs, reconstruction abroad, or aid to war-torn countries. ey won an over whelming victor y in the ’46 elections and gained control of both houses of Congress, the first time since the 1920s

In t his context Tr uman tur ne d to G enera l Marshall, arguably the most respected man in t he count r y at t he t ime Marsha l l had been the architect of victor y in World War II and, aer a brief retirement, had b owed to Truman’s wishes and had ser ved as a special presidential emissar y to China throughout 1946 seeking to mediate between the communists and nationalists. Tr ying to form a coalition government and end the civil war, Marshall l argely fai le d but displ aye d a ke en insig ht into t he limits of Amer ic an p ower and gar nere d Truman’s respect and gratitude. e president shrewdly understood that nobody would be a better candidate than Marshall for the position of secretar y of state.

The president shrewdly understood that nobody would be a better candidate than Marshall for the position of secretary of state.

15 S U M M E R 2 0 1 9

Harr y S Truman

p h o t o c r e d t G e o r g e C M a r s h a R e s e a r c h L i b r a r y p h o t o c r e d t G e o r g e C M a r s h a R e s e a r c h L i b r a y

Clement Attlee

U S Secretar y of State George C Marshall, British Foreign Secretar y Ernest Bevin, French Foreign Minister

Georges Bidault, and Russian Foreign Minister Vyacheslav

M Molotov at the Moscow Foreign Minister ’s Conference in March 1947

Marshall s canned the geop olitical and economic lands c ap e and s aw an a l ar ming pic ture e S ov iets were consolidating power in Hungar y and Poland and exerting pressure on Iran and Turke y. In wester n Europ e he witnessed economic paralysis, especially as heavy snows and frigid temperatures struck the continent and exacerbated coal shortages. In the western zones of Germany and in Jap an, o cc up at ion p olicies were flounder ing Civ i l conflic t rage d in Gre e ce and C hina. e Br it ish announced that financial exigencies would force them to withdraw their militar y presence in the eastern Mediterrane an. Me anw hile, C ommunist par ties in France and Italy gained momentum. And when Marshall met Stalin at a foreig n ministers conference in Mos cow in Apr i l 1947 t he s e cret ar y of st ate cou ld s e e t hat t he S ov iet dictator’s confidence was growing notwithstanding his calm demeanor and collaborative rhetoric.

Face d w it h mu lt iple cha l lenges, Marsha l l de velop e d a st rateg ic concept It was simple and derivative. e United States must not allow any adversar y to gain control of the preponderant resources of Europe and Asia. When an enemy or coalition of adversaries gained such dominance, they could mobilize immense capabilities to challenge American interests, wage war, and fight the United States. at, aer all, had been the overriding lesson of dealing with the Axis powers during World War II.

With this strategic concept in his mind, Marshall assessed the threats facing the United States Marshall believed that the Kremlin was not likely to gain preponderance through premeditated mi lit ar y ag g ression. Marsha l l c a lc u l ate d t hat St a lin wou ld s e ek to c apit a lize on e conomic setbacks and social miser y He judged that Stalin was patient, calculating, careful, and opportunistic. e Soviet dictator, Marshall thought, would use communist parties to exploit capitalist vulnerabilities.

Meanwhile, Marshall reorganized the Department of State and created a Polic y Planning Staff He s ele c te d G e orge F. Kennan to he ad it. Kennan, one of t he b est Krem linolog ists in t he American foreign ser vice had ser ved in Russia aer Roosevelt opened the U.S. embassy in 1934, and returned to Moscow at the end of the war He wrote the famous “long telegram” in Februar y 1946, arguing that the United States had to contain the growth of S oviet power and communist influence. Like Marshall, Kennan believed that the Kremlin wanted to exploit the West’s weaknesses Like Marshall, Kennan intuited that Stalin respected U S strength and would seek to avoid war. Like Marshall, Kennan grasped both the utility and limits of American power.

Along with Kennan, Marshall set priorities. Marshall determined that western Europe, western Germany, and Japan were most consequential for U S interests He made another critical decision: he resolved that economic aid to key countries was more important than militar y rearmament.

16 M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G

p h o t o c e d i : G e o r g e C M a r s h a l R e s e a r c h L b a r y

p h o t o c r e d i : G e o r g e C M a r s h a l R e s e a r c h L b r a r y

George Kennan

Delineating clear priorities, Marshall hoped to undercut support for communist parties and decided on aid for economic reconstruction in western Europe what became known as the Marshall Plan. As part of the program, he delineated steps to boost coal production in western G er many, li t he le vels of p er missible indust r i a l pro duc t ion, and put t he e conomy of t he western zones on a self-sustaining basis. Along with these economic plans, he aimed to unif y t he wester n zones and for m a prov isiona l gover nment w hat wou ld b e come t he Fe dera l R epublic of G er many, or West G er many Marsha l l a ls o insiste d on mutu al s elf-help and collaboration among the recipient nations of U S aid and he envisioned much greater economic integration of t he demo cratic p olities in wester n Europ e. At t he s ame time, he supp or ted a re c a librat ion of t ac t ics in Jap an, est ablishing e conomic rehabi lit at ion as a more imp or t ant priority than political and institutional reform

…use American wealth and power to overcome vulnerabilities that the Soviet Union could exploit; prevent Soviet Russia from gaining control of Europe and Asia, directly or indirectly…

To implement his foreign polic y plans, Marshall grasped the need to mobilize domestic support e secretar y of state was not happy with the president’s blatant anti-communist rhetoric He wante d to f rame Amer ic an init i at ives in more upli ing tones. He skillfully established a constructive relationship with the Republican leader in the S enate on foreign polic y matters, Ar t hur Vandenb erg . D espite p o or he a lt h, Marsha l l t ravele d around the countr y, addressing audiences and seeking support for a foreign aid program that surpassed anything in the American experience and that initially garnered widespread criticism for its costs and inflat ionar y implicat ions. Marsha l l felt confident t hat Amer icans w ho had ser ved overseas and had just returned home from a terrible war would come to understand the ne e d for e conomic and humanit ar i an aid, t he pur p os e of w hich was to re v ive demo crat ic polities in Europe, thwart the growth of another form of totalitarianism, and avoid another war during which American soldiers would have to die far from American shores.

Marshall’s strategic calculus was clear : use American wealth and power to overcome vulnerabilities that the Soviet Union could exploit; prevent Soviet Russia from gaining control of Europe and Asia, directly or indirectly ; create incentives for key countries to work together on behalf of shared values and interests, for example, open and non-discriminator y trade, the free flow of capital, and individual freedom Marshall liked to tell American audiences that they were deceiving themselves if they thought that individual liberty, representative government, and a marketplace economy would be safe at home if they disappeared abroad.

17 S U M M E R 2 0 1 9

p h o t o c r e d t G e o r g e C M a r s h a l R e s e a r c h L i b r a r y

President Harr y Truman signs the Economic Cooperation Act on April 3, 1948, granting $13 billion in aid to 17 European nations

From left to right:

On Nov 29, 1948, President Harr y S Truman and Secretar y of State George C Marshall meet with Paul G Hoffman, the first administrator of the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA), and W Averell Harriman the ECA’s Special Representative in Paris,

Marshall’s strategic calculus meant accepting tradeoffs. e secretar y of state recognized that his actions would be regarded as provocative in the Kremlin. He knew that Stalin would see U.S. initiatives as threatening Rebuilding western Germany and offering aid to eastern Europe, as the Marshall Plan initially did, threatened the most vital interests of the USSR. Only three years aer the most devastating war in Russian histor y, only three years aer his countr y had been occupied and devastated, the Americans were seeking to penetrate Stalin’s immediate sphere of influence and rebuild his most formidable foe. Germany, Stalin said again and again, would revive, attack, and endanger the security of the Soviet Union.

Marshall foresaw that Stalin would react to his initiatives Marshall anticipated the coup in Czechoslovakia and was not surprised by the blockade of B erlin. But he wagered that Stalin would not take militar y action against American forces, that the S oviet dictator would b e deterred by his knowledge that the Americans had the atomic bomb and a strategic air force Basically, Marshall knew that Stalin was not stupid; he knew that Stalin realized the Soviet Union would be vanquished in a full-scale conflict.

The secretary of state coupled his strategic wisdom with empathy, insight, and flexibility.

Yet Marshall also realized that American insistence on the revival of west German industr y and the formation of a provisional government would alarm friends in western Europe as well as enemies in t he Krem lin. e s e cret ar y of st ate couple d his st rateg ic w is dom w it h emp at hy, insig ht, and flexibi lit y Marshall’s British friends told him repeatedly that the French were horrified by Anglo-American actions in Germany. From France’s p ersp e c t ive, rebui lding wester n G er many mig ht provoke war with the S oviet Union in the short run or might lead to the revival of independent German power in the long run. In either case, French security seemed endangered. e French would not go along without guarantees of their security.

Marshall, therefore, supported militar y aid to France and staff talks with the French to prepare for a militar y emergenc y should it occur. Most of all, Marshall agreed to formal militar y guarantees and strategic commitments if they were indisp ensable to reassure France and garner French collab oration in the overall recover y program regarding western G ermany In other words, Marshall grasped French fears European fears and accepted long-term commitments, the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty and the beginnings of the NATO alliance. Such peacetime commitments were unprecedented in American histor y

18 M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G

p h o t o c r e d t G e o g e C M a r s h a l R e s e a r c h L b r a r y

Marshall cast a huge imprint on the early C old War In fact, he help ed catalyze the Cold War. e Marshall Plan was a turning point in postwar Soviet-American relations. Stalin saw it as a threat, as he did the rebuilding of western G ermany. Marshall and his colleagues understood that they constituted threats, likely to wors en a C old War that already was brewing. e “whole Berlin crisis,” wrote Army Chief of Staff Omar Bradle y, “has arisen as a result of two actions on the part of the western powers. ese actions are (1) implementation of the decisions…on G ermany and (2) institution of currenc y reform (in western Germany) ” e negative costs of these initiatives, Marshall calculated, were acceptable given the dangers of inaction. e prospective benefits the recovery of western Germany and western Europe far outweighed the liabilities, that is, a Cold War with the Kremlin.

If Marshall’s actions and calculations contributed to the onset of the Cold War, his more enduring legacy was the architecture that eventually won the Cold War. He focused on the reconstruction of western Germany, western Europe, and Japan and linking them in alliances with the United States He supported key nations that he hoped would embrace American values and interests, if not immediately, at least in the long run. ese included open markets, the free flow of capital, the elimination of exchange controls, low tariffs, and respect for individual freedom.

Marshall calculated that the Kremlin would defer to American power Like Kennan, he also b elie ved t hat w hen t he Kremlin re alized it could no longer exploit vulnerabilities, it would engage in constructive negotiations. is aspiration was not realized for four decades, but now t hat it happ ene d to a lmost e ver yone ’ s amazement we c an more f u l ly appre ci ate G e orge Marsha l l’s abi lit ies as a C old War st rateg ist: he p oss ess e d a coherent st rateg ic concept; he assessed risks incisively ; he set priorities and grasped the limits of American power ; he linked means and ends; he understood the fears of friends and the motives of adversaries; he recognized the need for bipartisan consensus at home; he worried about the excesses of rhetorical anti-communism; he grasped the importance of open trade, multilateralism, and alliances; and he accepted the bitter tradeoffs that inhered in making tough decisions

No one le a more enduring imprint on the C old War than did George C. Marshall.

M e l v y n P Le ffl e r i s t h e Ed wa rd Ste t t i n i u s Professor of American H istor y at the Universit y

o f Vi rgi n i a a n d t h e a u t h o r o f awa rd -w i n n i n g

b o o k s, i n c l u d i n g A Pre p o n d e ra n ce o f Powe r :

N a t i o n a l S e c u r i t y, t h e Tr u m a n Ad m i n i s t ra t i o n ,

and the Cold War and For the S oul of Mank ind: the United States, the S oviet Union, and the Cold War. Most recently he published Safeguarding D e m o c ra t i c Ca p i t a l i s m : U S Fo re i g n Po l i c y a n d National S ecurit y, 1920-2015.

U S Secretar y of State Marshall and Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov at the Moscow Foreign Minister ’s Conference in March 1947

19 S U M M E R 2 0 1 9

p h o o c r e d t G e o r g e C M a r s h a R e s e a r c h L i b r a r y

The measure of Marshall’s accomplishments lies in the fact that he is the only U.S. Secretary of Defense to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G

p h o t o c r e d i t : G e o r g e C M a r s h a l R e s e a r c h L b r a r y

George C. Marshall, Secretary of Defense 1950-1951

BY A L L A N R. M I L L E T T, P H.D.

In his third major appointment as steward of America’s international security, George C. Marshall provided patient, focused leadership for the national mobilization to rebuild the nation’s armed forces in 19501951. In his one year of ser vice as secretar y of defense, Marshall built the foundation of the Department of Defense that still exists.

Although the Korean War created the emergenc y that convinced President Harr y S. Truman to bring Marshall back into his administration, the secretar y of defense focused on the defense of Europe He also presided over a three-fold increase in defense spending and a similar expansion of the armed forces from 1.5 million to 2.1 million by 1951. Following the recommend at ions of NSC 68, he gave t he Unite d St ates mi lit ar y options besides nuclear war on the S oviet Union

Becoming secretar y of defense may have been Marshall’s greatest challenge, more demanding than being wartime chief of staff for the Army of the United States, or postwar secretar y of state. He j oi ne d an administration of d e cl i n i ng p owe r and p opu l ar it y, we a ke ne d by domestic hysteria about communism and divided over economic policy and racial integration e Congress had split into three factions over foreign policy that crossed party lines: collective security internationalists who supported NATO as the deterrent to Soviet imperialism; unilateralists who thought that Asia was the central battleground of the Cold War; and isolationists who wanted no “entangling alliances” and believed that threatening nuclear war was an adequate national strategy.

He joined an administration of declining power and popularity, weakened by domestic hysteria about communism and divided over economic policy and racial integration.

is article is based on Mark A. Stoler and Daniel D. Holt, eds., e Papers of George C. Marshall, Volume 7, October 1949–October 1959 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), as well as on the Rober t A Lovett Papers, Yale University Librar y. Doris M. Condit, History of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Volume 2, e Test of War, 1950–1953 (Washington, D C: Office of the S ecretar y of Defense, 1988), is an essential source So is Forrest Pogue, George C Marshall: Statesman, 1945–1959 (New York: Viking,1987)

21 S U M M E R 2 0 1 9

left: Dr. Allan Millett discusses Marshall and the Korean War: 1950-1951 at the Pogue Auditorium of the George C. Marshall Foundation on March 21, 2019.

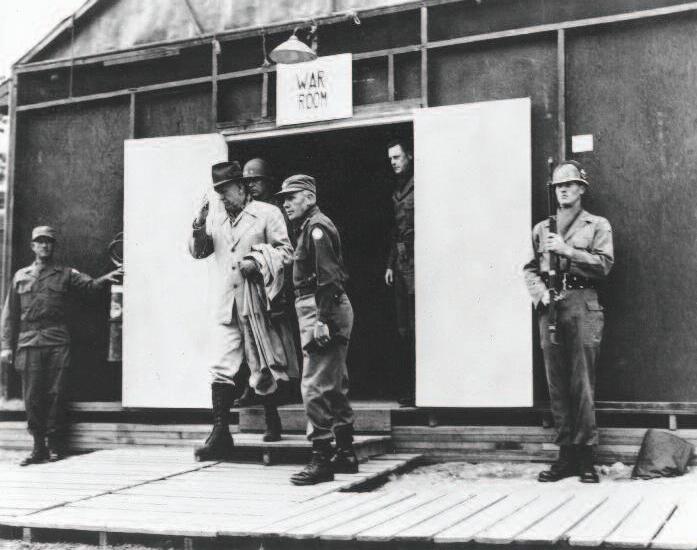

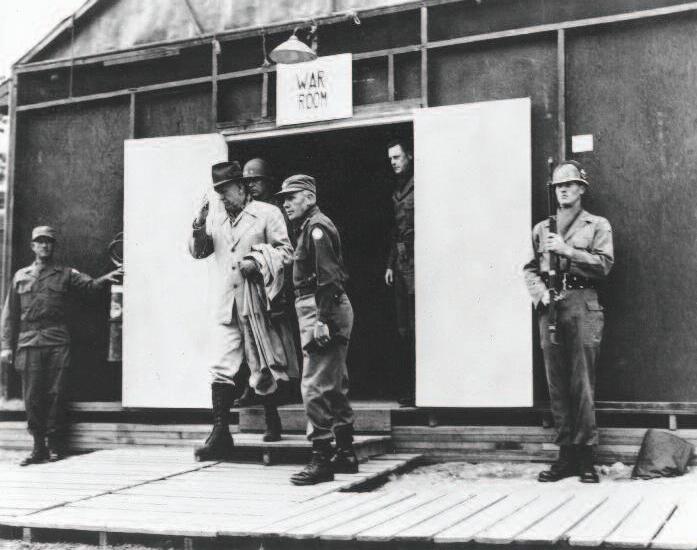

Opposite page: Secretary of Defense George C Marshall and LTG William M Hoge, June 8, 1951

p h o t o c r e d i t G e o g e C M a r s h a l R e s e a c h L b r a r y

Secretar y of Defense George C Marshall emerges from X Corps War Room on the Central Korean Front accompanied by LTG Edward M Almond (right), CG, X Corps, and LTG James Van Fleet (rear), CG, 8th U S Army

Marshall faced a C ongress that did not admire him as much as President Truman did He also kne w t hat le ading Republican memb ers held him resp onsible a long wit h S e cret ar y of St ate Dean Acheson for the “loss” of nationalist China and the growing threat of the S oviet Union. e vote on his confirmation as secretar y of defense, which required a one-time exception to a provision of the National Security Act of 1947 that barred retired generals from being secretar y of defense, showed that Marshall faced a hostile minority in C ongress. One hundred sixteen s enators and repres ent at ives vote d against Marsha l l’s app oint ment. As s e cret ar y, Marsha l l worked ver y hard on Congressional relations, testifying sixteen times on key defense legislation He stayed in constant contact with leaders of both parties.

During his year in office, he played a crucial role in establishing a NATO military establishment led by an American, General Dwight D. Eisenhower,

Although Marshall guided the Depar tment of Defense’s management of t he Kore an War t hroug h t he Nat iona l S ecurity C ouncil, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the StateDefense coordinating committee, his interest and activity fo c us e d on g lob a l col le c t ive, convent iona l defens e

During his year in office, he played a crucial role in establishing a NATO militar y establishment, led by an American, General D wight D. Eisenhower. He t hen won cong ressiona l approva l of bui lding t he Amer ic an g round forces in Germany from two to six divisions and creating the U.S. Air Forces Europe. He pushed for ward negot i at ions in NATO for G er man mi lit ar y p ar t icip at ion. Marsha l l foug ht for t he

22

M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G

p h o t o c r e d i : G e o r g e C M a r s h a l R e s e a r c h L b r a r y

restructuring and expansion of aid to foreign armed forces. He accepted congressional demands to rearm the Chines e nationalists, but extrac ted supp or t for the creation of a ne w Japanes e militar y establishment (“police reser ve”) of 75,000 members, enlarged to 254,799 by 1960 and officered by former officers of the imperial armed forces. He supported the peace treaty with Japan and the mutual security agreement that followed He endorsed the creation of the Mutual S e c ur it y Agenc y (1951) to co ordinate e conomic and mi lit ar y foreig n aid and t he Office of Defense Mobilization (1950) to revive the defense industr y.

In an area dear to his heart, a national system of compulsor y militar y ser vice, Marshall did not get his way, but the compromise he fashioned in the Universal Militar y Training (UMT) and S er vice Ac t (SA) ( June 1951) s er ve d wel l enoug h unt i l t he 1970s. A champion of univers a l militar y training, Marshall believed a large peacetime army, backed by a large ground forces res er ve, held t he ke y to successf u l deter rence of t he S oviet Union. It was not a viable concept. is army of mi l lions cou ld not deploy b e yond t he wester n hemisphere in t ime to influence a shor t war w it h t he USSR or communist China. Marshall understo o d this problem, which shaped the eventual compromise. He also argued that universal conscription built national identity as it did in Israel and Switzerland He also believed that further development of the UMT and SA would lead to greater citizen participation in the armed forces.

George C Marshall, Secretar y of Defense, converses with LTG Edward M Almond, CG, X Corps, at the Corps Airstrip after inspecting United Nations troops of the Central Korean Front

In an area dear to his heart, a national system of compulsory military service, Marshall did not get his way,

e eventual manpower polic y aer 1951 fused the S elective S er vice System (the dra) and reser ve forces manning, but at the expense of the active duty army e active duty armed forces

23 S U M M E R 2 0 1 9

p h o t o c e d i : G e o r g e C M a r s h a l R e s e a r c h L b r a r y

X Corps Commander

LTG Edward M.

Almond takes the wheel of his jeep to take Secretar y of Defense George C. Marshall and GEN Matthew B. Ridgway, CINCUNC, to a special briefing at X Corps HQ, Central Front, Korea.

would fill the ranks with volunteers, attracted by patriotic appeals and financial rewards, with conscription used to fill the places volunteers didn't. e dra boards of “friends and neighbors” would choose the draees by categories of physical fitness, dependenc y, trainability, and likely adjustment to ser vice life e system sought young men, single, physically fit, high school graduates, and eighteen years of age or older If they could qualif y, they could avoid army ser vice by enlisting in the Air Force, Navy, or Marine C orps, which offered more excitement and more job training (in theor y) Army ser vice as a conscript, however, was one or two years shorter Army and Air Force National Guard units as well as reser ve units of all the ser vices profited most under the new law. By enlisting in a reser ve unit, young males could avoid the dra or dra-coerced volunteering A reser vist might have an eight-year ser vice obligation, but he (or she) could still pursue a civilian occupation with little interruption for periodic training e system did allow the expansion of Ready Reser ve forces, but it did not solve equity-of-risk issues or produce immediate combat-ready ground forces for foreign deployment.

Marshall, of course, could not ignore his role in super vising the militar y commitment to S outh Korea. He marched in step with the Tr uman administration and G eneral Douglas MacAr thur until the Chines e inter vention, Novemb er-Decemb er 1950 Although he followed S ecretar y of State Aches on ’ s leadership, he approved of the Inchon landing as a way to end the Nor th

24 M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G

p h o t o c r e d i t G e o r g e C M a r s h a R e s e a r c h L b r a r y

Korean invasion and the decision to unif y Korea by force under UN sanction by an of fensive f rom t he 38t h Para l lel to t he Ya lu r iver When C hina entere d t he war, Marsha l l accepte d a return to the original war aim, to pres er ve the Republic of Korea, a p osition he shared with Aches on and the Joint Chiefs of Staff ( JCS). Douglas MacAr thur said there was “ no substitute for victor y, ” meaning his victor y, which was def ined by the defeat of the Chines e army and any S ov i e t forc e s t hat got i n t he w ay. His p owe rs of prophe c y i n d e cl i ne, Ma c Ar t hu r t he n waged a four-month campaign through the Republican press and C ongress to blo ck the administration’s commitment to a negotiated s ettlement

Marsha l l and t he JCS had ample exp osure to MacAr thur’s lifelong habit of reinter preting his orders to suit hims elf Once Marsha l l was conv ince d by G enerals J. L awton C ollins (U.S. Ar my Chief of St aff ) and Matthew B. Ridg way that the Eighth Army was not on t he verge of anot her B at aan or D un k irk, Marsha l l sided with Acheson and W. Averell Harriman, Truman’s national security advisor, in confronting MacArthur’s public criticism of the administration’s “defeatist” strateg y Although Marshall and the JCS reluctantly agreed that Truman had ample reason to relieve MacArthur, they cautioned Truman to treat the C ommander-in-Chief United Nations C ommand – C ommander-in-Chief Far E ast C ommand (CINCUNC-CINCFE) with respect and let him make his case openly to C ongress, however unpleasant the hearings would be Marshall became the leading witness in the MacAr thur-Far E ast hearings by the S enate, and he showed great patience and credibility in his explanation of the administration’s global security polic y. It was his finest public appearance.

…he showed great patience and credibility in his explanation of the administration’s global security policy. It was his finest public appearance.

Marsha l l remaine d a “Europ e First” champion unt i l his de at h in 1959 His hand-picke d successor, Robert A. Lovett, continued to concentrate on NATO defense. Truman even had to caution Lovett about meeting the Eighth Army’s ammunition needs, but with Marshall protégés, Ridg way and General Mark W Clark running the war as CINCUNC-CINCFE, the president need not have worried.

e measure of Marshall’s accomplishments lies in the fact that he is the only U.S. secretar y of defense to receive the Nobel Peace Prize

Dr Allan R M illett is the Stephen E Ambrose Professor of H istor y at the Universit y of New Or leans. He is a specialist of inter national stature on the histor y of the Korean War. Dr. M illett has published many essays, ar ticles, enc yclopedia entries and commentaries on the Korean War and is the author of the t wo -

volume histor y The War for Korea I n addition to his own work , M illett ser ved as an editorial consultant for the Ministr y of Defense, Republic of Korea, for the revised and translated threevolume Korean official histor y, The Korean War, for which he arranged an American edition

25 S U M M E R 2 0 1 9

i n r e v i e w

Dr Benn Steil is senior fellow and director of international economics, as well as the official historian in residence, at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York He is also the founding editor of I ntern a t io n a l Fi nan ce , a scholarly economics journal; lead writer of the Council’s GeoGraphics economics blog; and creator of four web-based interactives track ing Global Monetar y Policy, Global Imbalances, Sovereign Risk, and Central Bank Currency

Swaps He received his MPhil and DPhil (PhD) in economics from Nuffield College, Oxford He also holds a BSc in economics summa cum laude from the Whar ton School of the University of Pennsylvania

By Benn Steil

A Council on Foreign Relations Book.

New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018

Maps Tables Illustrations Cast of Characters

Notes. Bibliography. Index. Pp. xii, 608.

Review by David Hein, Ph.D.

Members of the George C. Marshall Foundation scarcely need to be reminded that General Marshall is principally renowned for two giant works: building the armed forces of the United States to join with allies and defeat the Axis powers (1939–1945), and leading the effort to devise, pass, and implement the European Recovery Program (ERP) or Marshall Plan (1947–1949) When Marshall became the first soldier to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, most observers assumed it was for the latter, the program for peace which would prevent another war, while the awardee himself believed that the prize was given for the former, the preparation for war which would achieve a just peace

In any event, as ever yone knows, the Marshall Plan, together with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, was hugely important in laying the foundation of the democratic order over succeeding decades At the same time, howe ver, anyone who has studied the Europ ean Recover y Program knows that this undertaking is susceptible of a variety of interpretations of both its aim and its effectiveness. Even its core inter pretive metaphor is contested: although s ometimes called an economic pump-primer, s ometimes termed an industrial lubricant, ERP monies also resembled a

vaccine or, perhaps better, an injection of carefully targeted stem cells: grants, loans and counterpart funds stimulated host bodies to develop their natural powers of resistance.

Yes, the Marshall Plan was highly complex and thus is conceptually hard to grasp, let alone write about clearly and comprehensively But the author of the book under review is up to the task Benn Steil is senior fellow and director of international economics at the Council on Foreign Relations. is professional connection is significant: research assistants have helped Steil produce a work that incorporates German as well as American archival data, sophisticated economic reports and analyses, Russian-language materials, and translations from Czech, Serbian and other sources. In addition, CFR policy experts were on hand to offer counsel.

Notwithstanding this useful support, Steil’s writing carries the conviction of one man, its author, in both its thesis and its tone. In prose that is lively and engaging Steil knows exactly how much time to spend on weighty subjects the author sets forth the histor y of the European Recover y Program as an episode of the C old War ; and he is right to do so e Marshall Plan supported both wartime allies and former enemies in pursuit of the larger geopolitical strategy of containment Famously elaborated by George Kennan, the Marshallappointed chief of the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff, containment policy sought to defend the U.S. national interest by reinforcing independent centers of power in Europe and Asia which could defy the Soviet Union

26 M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G T H E M A R S H A L L P L A N: DAW N O F T H E CO L D WA R

In his new histor y, Steil’s aim is, in his words, to situate “the Marshall Plan more directly at the center of the emerging Cold War than earlier accounts, highlighting the seriousness with which Stalin treated the threat it represented to his new, hard-won buffer zone in central and eastern Europe” (p xii) At the end of World War II, Stalin in another of his strategic errors believed that Americans would pursue the course they had followed aer the Great War : withdraw from Europe and probably even allow Germany to become a weak, pastoralized, neutral countr y, providing ongoing reparations that would help the Soviets to rebuild their own industr y and infrastructure.

Instead, the ERP represented something quite different: the challenge of an ongoing, strategically committed U.S. presence economic, but to some degree psychological, cultural, and political, too in western Europe e linchpin of this reconstruction would be a western Germany that was both reindustrialized and capitalist, at the center of a western Europe that was capitalist, economically integrated, democratic, dynamic, and hopeful. As Steil emphasizes, “In many ways, the [C old War] conflict was about Germany…. e creation of a strong, independent West Germany, integrated into a robust West European economic and North Atlantic security architecture, represented a fundamental departure in policy from the late FDR years, one without which it is difficult now to imagine a peaceful end to the Cold War on American terms” (p. 356).

is book’s back matter is quite useful, as well. It includes a cast of characters of all the ERP’s key players as well as politicians and scholars, an app endix of imp or tant sp eeches by

Truman and Marshall, and another appendix of macro economic indicators real output, inflation, budget deficits, government debt, and current accounts for the period 1946 to 1955 Additional supplements provide maps and counterpart-fund balances.

In sum, B enn Steil’s Marshall Plan is an original, reliable exercis e in p olitical, diplomatic and economic histor y It offers both accurate des cription and judicious ass essment of a program that is not just an artifact of histor y but a continually thought-provoking venture in foreign policy which effectively combined liberal internationalism and defensive realism. Strongly recommended, this b o ok should b e anyone ’ s premier go-to s ource on the European Recover y Program.

David Hein, Ph D , is a senior fellow at the George C Marshall Foundation and the author, most recently, of “At 70: Rethinking the Marshall Plan,” in Providence: A Journal of Christianity and

A merican Foreign Polic y (Fall 2018), and of “George C Marshall: Exemplar of Lived Burkean Conser vatism,” in the Intercollegiate Review (Spring 2019).

27 S U M M E R 2 0 1 9

ERP in Action: The Netherlands

Winter’s Coming: The Cold War

FDR and Marshall: e Men Who Saved D-Day Bestselling author and award-winning biographer Nigel Hamilton gave a special presentation of the George C Marshall Foundation’s Legac y S eries at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture in Richmond, Virginia, on Tuesday evening, May 14, 2019. e program was the first Legac y S eries event held in Richmond and celebrated the publication of Nigel Hamilton’s new book, the final volume of a monumental trilog y on FDR as commander-in-chief.

On June 6th, we celebrated the 75th anniversar y of the D-Day landings at Normandy, a masterstroke of strateg y and planning, the execution of which would result in the end of war in Europ e, a shor t, but br utal, ele ven months later. Today, little is known or rememb ered of the stiff British resistance to O verlord, and of the fact that the great invasion

came ver y clos e to ne ver taking place e Prime Minister, ne ver a b elie ver in such an invasion, remained in favor of fighting further in the Mediterranean; in Italy ; in the Do decanes e Islands; the Dardanelles; in Rome; in the B alkans any where but Normandy is led to p erhaps the greatest strategic crisis of World War II with General Marshall, the U S Army Chief of Staff, nobly agreeing to b e us ed by President Frank lin Roosevelt as a pawn, in order to meet and defeat Churchill’s imp ending “showdown,” as Churchill called it. For without the British, D-Day could not be mounted

Based on his new book, War and Peace: FDR’s Final O dy ss e y , Hamilton shared the stor y of how two men, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall, ensured that the great invasion did take place, thereby hastening an end to Europe’s long nightmare

28 M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G

Nigel Hamilton

Photo by Nick Hamilton

p h o o c r e d t G e o r g e C M a r s h a R e s e a r c h L i b r a r y

General George C Marshall and President Franklin D Roosevelt at the Casablanca Conference in Casablanca, French Morocco, January 1943

Spy Pilot: Francis Gar y Powers, the U-2 Incident, and a C ontroversial C old War L egac y

Francis Gar y Powers, Jr continued the Winter’s Coming sequence of the Marshall Legacy Series with an interesting lecture on his new book Spy Pilot: Francis Gar y Powers, the U-2 Incident, and a Controversial Cold War Legacy on May 23 in Gillis eater at VMI’s C enter for L eadership and Ethics. In his lecture, Mr Powers discussed the Cold War, the U-2 Incident, and the controversy that surrounded his father following the May 1, 1960 sho otdown of the CIA U-2 spy plane he was piloting is was one of the most infamous incidents of the Cold War and caused a severe setback in U.S. – Soviet relations.

Francis Gar y Powers, Jr , is Chairman Emeritus and Founder of e C old War Museum. He is the author of Letters from a Soviet Prison and Spy Pilot. Mr. Powers appears regularly on C-SPAN, t he Histor y C hannel, Dis cover y, and A&E.

An Evening w ith Mark

C line: Stories of E s c ap e from E ast Germany

Mark Cline concluded the Winter’s Coming sequence of the Legacy Series on June 20 with an enter taining dis cussion of the most memorable es cap es f rom E ast G ermany over the B erlin Wall

Between 1949 and 1961, over two million East G ermans fled into West G ermany through West B erlin By August 1961 an average of 2,000 E ast G ermans were crossing into the West e ver y day To stop the exo dus, S oviet leader Nikita K hr ushche v recommended to E ast G ermany that it blo ck access to West B erlin. On the night of August 12, 1961, because of a decree passed by the East German

Volkskammer (People’s Chamber), the border b etween E ast and West B erlin was clos ed “Sho ck workers” f rom E ast G ermany and Russia sealed off the border with a barrier o barbed wire and light fencing that eventually b ecame a complex s eries of wall, for tified fences, gun positions and watchtowers heavily guarded and patrolled. In the end, the B erlin Wall was 96 miles (155 km) long, and the average height of the concrete wall was 11.8 feet (3 60 m)

Francis Gary Powers, Jr

O ver the cours e of the Wall’s existence, according to official sources, 133 people were confirmed killed tr ying to cross into West Berlin, while a victims’ group puts the number at over 200 dead ere were also some 5,000 successful escapes into West B erlin.

Mark Cline is a sp eaker, stor yteller, actor, and entertainer. He is well known for his involvement in activities and attractions in Rockbridge County, Virginia.

e Man for All S eason s Sequence of the L egac y Series kicks off on July 25

e Man for All Seasons sequence will explore asp ects of G eorge C Marshall’s life that are oen overshadowed by his monumental achievements as chief of staff and secretar y of state, including his time as a cadet at the Virginia Militar y Institute, his tenure as President of the American Red Cross, and his chairmanship of the American Battle Monuments C ommission. Although less wellknown, Marshall’s exp eriences in thes e p ositions provide valuable insights into Marshall’s development as a leader and public ser vant as well as further highlight the extent of his contributions to the U.S. and the world.

L e g a c y S e r i e s

S C H E D U L E

e Man for All Seasons

July 2019 –June 2020

The Man for All Seasons Exhibition opens on

September 1, 2019

July 25

Thomas H Conner discusses George Marshall and the American Battlefield Monuments Commission

August 29

Gerald M Pops discusses George Marshall and Israel

September 26

David L Roll discusses George Marshall: Defender of the Republic

To see the lineup for the rest of the Marshall Legacy Series, go to our website

O u r L e g a c y S e r i e s p r e s e n t a t i o n s c a n b e v i e w e d o n t h e Fo u n d a t i o n’s Yo uTu b e c h a n n e l t h a t i s a c c e s s i b l e f r o m t h e w e b s i t e 29 S U M M E R 2 0 1 9

Two Distinguished Americans to Receive Marshall Foundation Awards on November 11

Madeleine K Albright, former U S Secretar y of State, will receive the George C. Marshall Foundation Award, and David Rub enstein, C o - Fou n d e r an d C o - C E O of T h e C ar l y l e Group, will receive the G eorge C. Marshall Foundation Humanitarian Award

Dr. Albright will be recognized for her career of distinguished public ser vice in the tradition

of George C. Marshall, for her dignity and integrity, for her de votion to f ree and democratic institutions, and for promoting the economic development which allows these institutions to flourish Mr Rubenstein will be recognized for his philanthropic supp or t of educational initiatives in Washington, D.C. public s cho ols, at Duke University, and at other institutions of higher learning, as well as for his tireless efforts to preser ve and render more accessible the histor y of our republic

30 M A R S H A L L F O U N D A T I O N O R G S H O R T S

p h o t o c r e d i t s G e o r g e C M a s h a l R e s e a r c h L b a r y

is black-tie gala event will be held at the National Por trait Galler y and Smiths onian American Art Museum in Washington, D C

e evening will begin with a reception at 6:30 p m and brings together foreign and U S dignitaries, government officials, business leaders, and friends and trustees of the George C. Marshall Foundation to honor thes e two distinguished Americans

e Marshall Foundation exists to ensure the example of leadership and character offered by General George C. Marshall will be known to mi l lions of p e ople in t he 21st centur y Sp ons or s h ip s f rom t h i s e ve nt w i l l s upp or t ou r e du c at i on a l m i s s i on n at i on a l l y an d inter nat iona l ly

For more information about this event, please contact Leigh McFaddin at 540.463.7103 ext. 138 or mcfaddinlh@marshallfoundation.org.

George Marshall: Defender of the Republic

By David L. Roll (Dutton Caliber, 2019)

War and Peace: FDR's Final Odyssey : D-Day to Yalta, 1943–1945 (FDR at War) By Nigel Hamilton (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019)

War and Remembrance: e Stor y of the American Battle Monuments Commission By omas H. C onner ; Foreword by James S cott Wheeler. (University Press of Kentucky, 2018)

31 S U M M E R 2 0 1 9 N E W B O O K S A B O U T O R I N C LU D I N G M A R S H A L L

p h o t o c r e d i t s T m o t h y G r e e n fi e l dS a n d e r s

Far left, top: Madeleine Albright, Far left, bottom: David Rubenstein; left: National Portrait Galler y and Smithsonian American Ar t Museum in Washington, DC

the last word

c o u n t r y h a s p r o g r e s s e d a l o n g w a y t o w a r d m a t u r i t y … . To d a y t h e y

f a c e a n o t h e r i m p o r t a n t d e c i s i o n ,

p o s s i b l y t h e m o s t f a r - r e a c h i n g i n

i m p o r t a n c e o f a l l — t h e N o r t h A t -

p h o o c r e d t G e o r g e C M a r s h a R e s e a r c h L i b r a r y A m e r i c a n s “ a r e s o m e t i m e s s t i l l i n c l i n e d , I f e a r, t o p l a c e u n d u e r e l i a n c e o n t h e s h e l t e r i n g v a l u e s o f [ t h e p r o t e c t i v e s h i e l d s o f t h e A t l a n t i c a n d P a c i f i c o c e a n s ] … . I n t h e l a s t t e n y e a r s , p u b l i c o p i n i o n i n t h i s

l a n t i c Tr e a t y … . T h i s t r e a t y i s o n e o f t h e m o s t d e t e r m i n e d s t e p s t h e