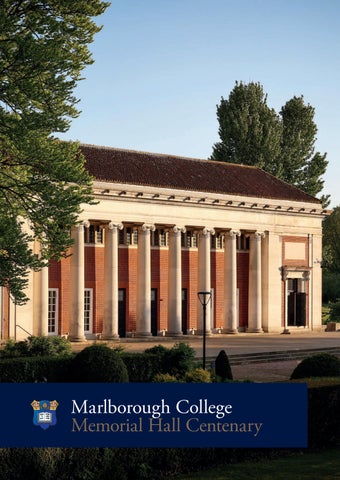

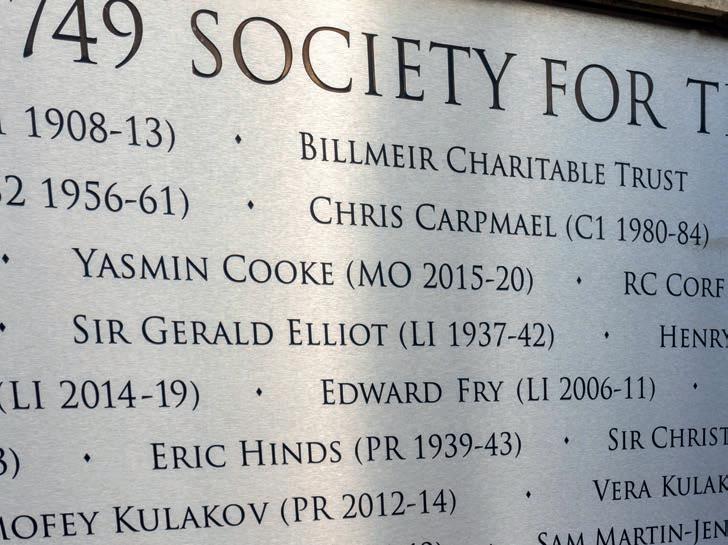

One hundred years ago Marlborough College’s Memorial Hall was completed. This book describes how the 749 former pupils and staff who lost their lives in the First World War have been remembered, and how a noble building emerged out of the grief felt by the bereaved.

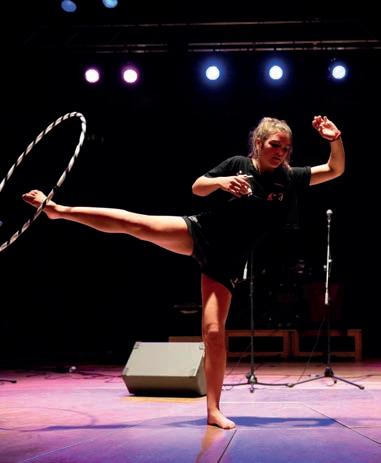

The form of the building, the process of recording those who had died, and the financial difficulties presented by the scale of the work resulted in many challenges. The Memorial Hall honours the fallen but at the same time it celebrates life. It was designed to be of practical use to the school as well as a solemn reminder of the war. These pages give an account of some of the activities and events which have taken place within its walls.

The Memorial Hall reflected the ambition and strength of Marlborough’s community in the way that it underlined the importance of duty and service. It was the result of the great initiative shown by so many to honour the fallen and console a generation which had lost so much. William Newton, the Old Marlburian architect, designed a building which speaks so eloquently about the need for order and reflection in the post war years. Its reinterpretation of classicism also embraced new technology. Since the Hall’s restoration in 2018, commemorating the hundredth year of the ending of the conflict, it has come to be regarded as a world-class concert hall and auditorium.

Marlborough is so fortunate in its architectural heritage, and this building is particularly valuable because the messages which it conveyed in 1925 are still expressed today: the importance of community, ambition, service and initiative are embedded as the College’s four key values. The Memorial Hall, with its location planned so carefully by the Chapel, serves to remind everybody at Marlborough what should be learned from the past and how life should be lived today.

Louise Moelwyn-Hughes Master (2018- )

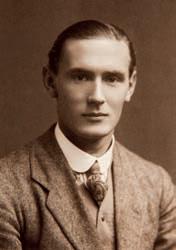

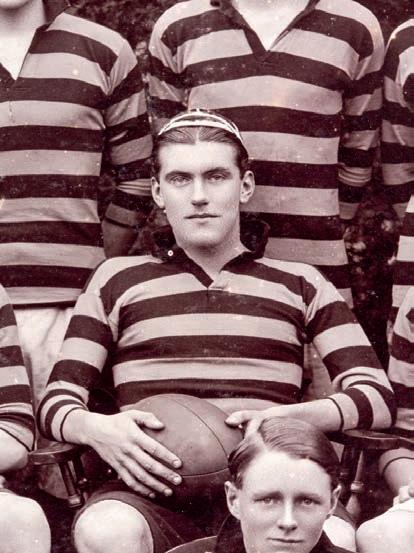

Leslie Richmond (PR 1902-05) was the first Old Marlburian to die in the First World War. His photograph in the Roll of Honour shows a fine young man in the uniform of a lieutenant in the Gordon Highlanders. We know little more about him other than that he came from Crieff in Scotland and was in the XV in 1904. He was killed in action during the retreat from Mons on 23rd August 1914 at the age of twenty-six.

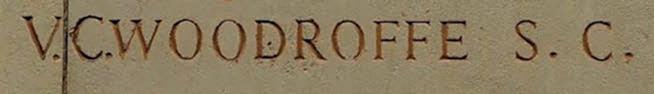

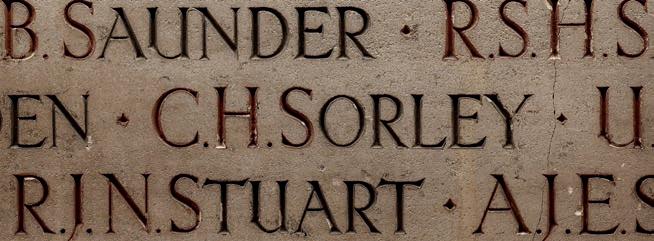

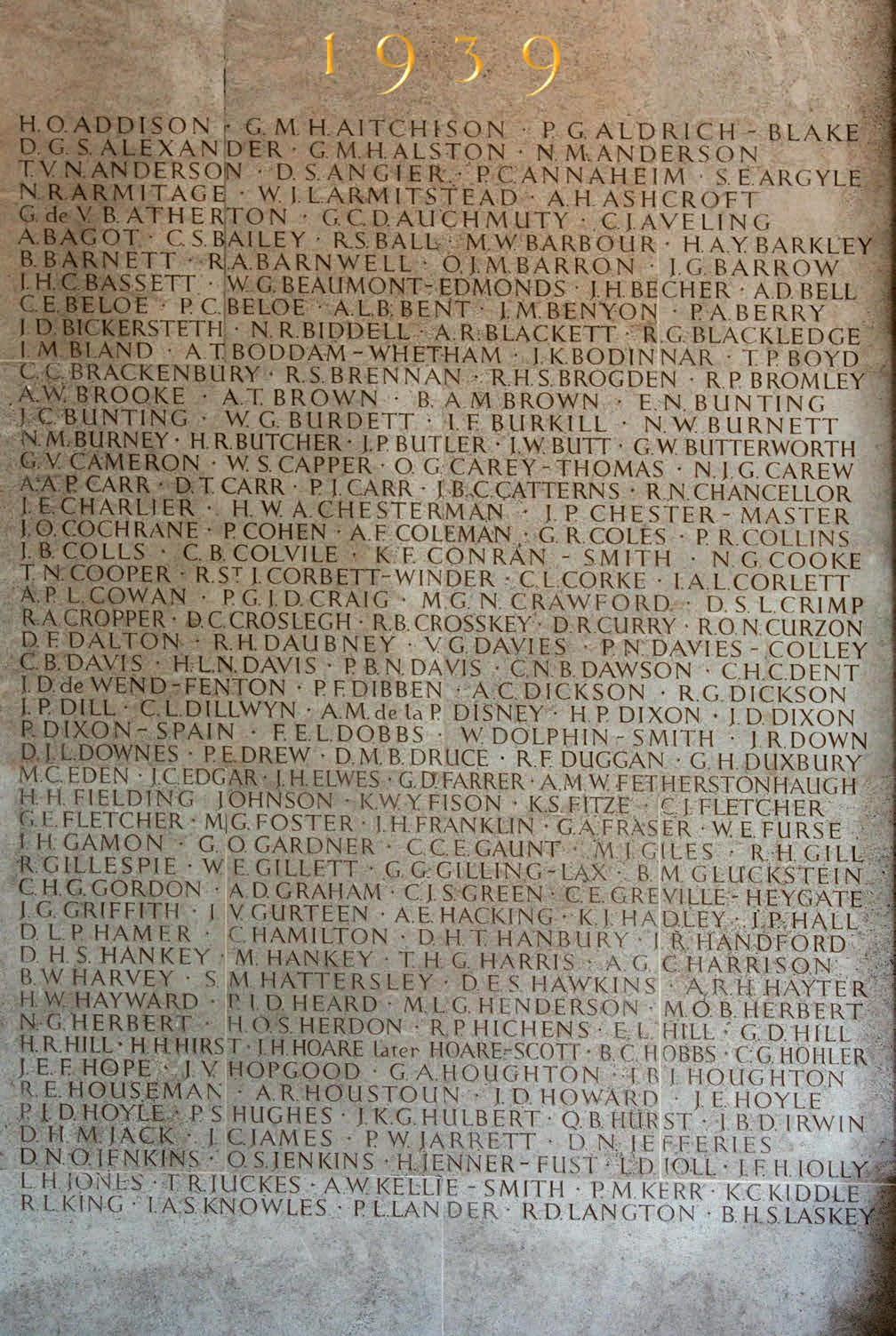

There were to follow 748 more former pupils and members of staff (teaching and non-teaching) who were to ‘make the ultimate sacrifice’, as the language of the time often put it. Their names, expertly carved along the back wall of the Memorial Hall, ‘cut in Ancaster stone by Mr Lawrence Turner (C1 1877-81), and faintly tinted grey and red’ (as described by Darcy Braddell in The Architectural Review of June 1925), are the simplest of memorials. Yet behind each name lies a person and a story, some as in the case of Leslie Richmond only thinly known, others more fully lauded and remembered.

First row left to right:

Leslie Richmond (PR 1902-05)

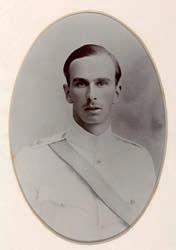

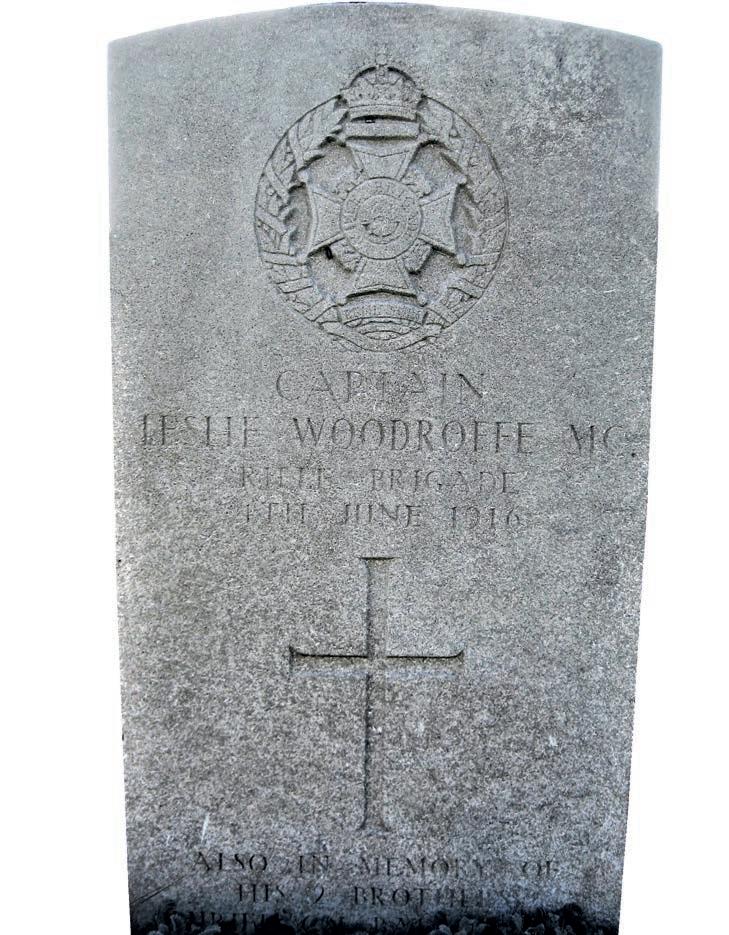

Sidney Woodroffe (B1 1908-14)

Kenneth Woodroffe (B1 1906-12)

Second row left to right:

Leslie Woodroffe (B1 1898-1904)

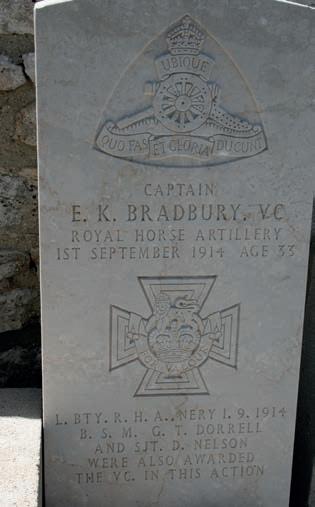

Edward Bradbury (SU 1894-98)

Keith Rae (CR 1912)

Third row left to right: Freeman Atkey (CR 1908)

Harold Roseveare (B3 1908-14)

Charles Hamilton Sorley (C1 1908-13)

Fourth row left to right: Bob Giffard (CO 1898-01)

Guy Devitt (LI 1906-10)

Jack Lambert (CO 1906-08)

Sydney Giffard (CO 1903-07)

Fifth row left to right: Edmund Giffard (CO 1901-05)

Francis Dodgson (B3 1904-07)

Hugh Butterworth (C2 1899-04)

Charles Prangley (C1 1911-15)

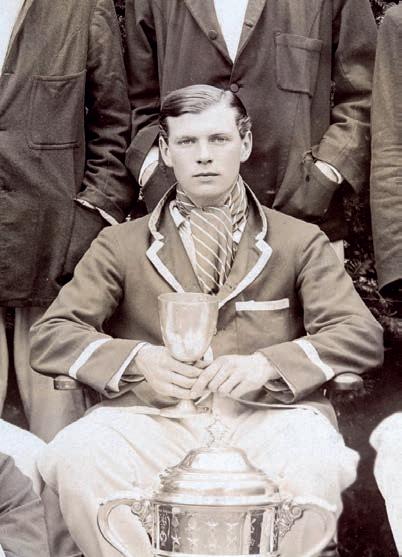

Best known perhaps are the Woodroffe brothers, three remarkable young men who served their school and then their country with considerable honour and bravery. All three were Senior Prefect, performed with great credit in all major College sports teams and in the Officers’ Training Corps (OTC), and won scholarships to Oxbridge. For his part in the fighting at Hooge on the outskirts of Ypres on 30th July 1915, Sidney (B1 1908-14) was to be posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. In the early hours of that day the Germans pushed the British back to their second line of trenches in the

first recorded use of flame-throwers. At the heart of the British defence of this position was nineteen-year-old Second Lieutenant Sidney Woodroffe of the 8th Battalion, Rifle Brigade, in command of two platoons. After close-quarter fighting which lasted most of the morning it was only weight of numbers that forced the British to retreat.

Under intense fire Sidney succeeded in bringing what was left of his men back safely across almost 200 yards of open ground, and down a heavily shelled communication trench. He then led them back again in

a counterattack with inadequate artillery cover and against a German position that provided the enemy with a dominant field of fire. Despite these odds Sidney managed to get some of his men to the German barbed wire in front of their trenches, only to be shot in his attempt to cut that wire to facilitate the attack. In his tribute, the Master concluded with these words: ‘A finer and more manly gentleman Marlborough has not bred, and his name will shine in letters of gold on her roll of fame.’

The eldest of the three, Leslie (B1 1898-1904), who had become a schoolmaster at Shrewsbury, was severely wounded in the same action, but returned to the front less than a year later, only to die of shell-fire wounds on 4th June 1916. Of Kenneth (B1 1906-12), the middle one of the three, who was the first to die, killed in action in the attack on Aubers Ridge in May 1915, it was said in tributes in The Marlburian that ‘Few boys combined so many gifts of scholastic ability, athletic prowess and personality. Open, genial and unassuming, yet with the power and will to assert himself in School and House, he was a great force here’. The same could have been said of both Sidney and Leslie. On the news of Leslie’s death The Marlburian reported: ‘The sympathy of the whole Marlburian world will go out to Mr and Mrs Woodroffe in this final loss; they offered all and alas! they have lost all.’

Sidney was one of three Old Marlburians to be awarded the Victoria Cross in this war. One, Charles Foss, survived the war and went on to become aide-de-camp to King George V before retiring, and then Colonel commanding the Bedfordshire Army Cadet Force (ACF) during the Second World War. The other posthumous Victoria Cross was awarded to Edward Bradbury (SU 1894-98) – the citation barely does justice to the remarkable bravery of this man: ‘for gallantry and ability in organising the defence of L Battery against heavy odds at Nery’. On 31st August 1914 the brigade to which L Battery was attached found itself heavily outnumbered against a surprise German attack. Shouting

‘Come on! Who’s for the guns?’ Bradbury led the charge out of cover into the open to bring the guns of L Battery into action. Among the men who joined Bradbury at the guns was Lieutenant Jack Giffard (CO 1898-1901). The Germans had twelve guns bombarding the village, but the fire from Bradbury’s gun (soon the sole surviving one) was so severe and accurate that soon all the German guns were ranged on that one weapon, affording the British cavalry enough respite to organise themselves for defence and counterattack. Bradbury continued firing an estimated 160 rounds before reinforcements arrived, despite losing both his legs. He died from his wounds that same day and is buried in the village cemetery at Nery.

In the same action that Sidney Woodroffe died, Keith Rae also lost his life. Keith was one of six beaks who died in the war. This twentyfive-year-old scholar of Balliol College Oxford had arrived to teach at Marlborough only two years before the outbreak of war. Imbued with a strong sense of Christian socialism, his faith clearly sustained him through the challenges he faced out on the front. In a letter he wrote to fellow member of Common Room chaplain Ernest Crosse only a couple of months before he died he describes attending to two wounded comrades ‘under a rain of shells’ as ‘the happiest moment of my life. We were all just on the brink of the next world’. A victim of the Germans’ liquid fire attack that

initiated the action at Hooge on 30th July 1915, a memorial to him that stands on the edge of the Sanctuary Wood cemetery describes him as ‘Christ’s faithful soldier and servant unto his life’s end’. As with so many young men, former pupils or teachers, the idealism of youth was scant protection against the horrors of the industrialised warfare they were facing in this conflict.

Another scholar on the staff, this time from Pembroke College Cambridge, was Freeman Atkey, who arrived to teach at Marlborough in 1908. Described by his old tutor as ‘the best pupil I ever had at Pembroke’, he was the first beak to recognise the genius of Charles Sorley. Freeman agonised over joining the Army in September 1914 but found contentment in the comradeship of the trenches. Like many volunteer officers, he worried about proving himself in a setting so alien to his nature, but his coolness when in danger was never in doubt. He was killed by a sniper’s bullet a few days after the start of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916 and was much mourned by those he served with: ‘his loss is regretted by every officer and man in the battalion. He was absolutely fearless’. Sorley described him as ‘the sanest, humanest man in Common Room’, yet another rich talent snuffed out in his prime.

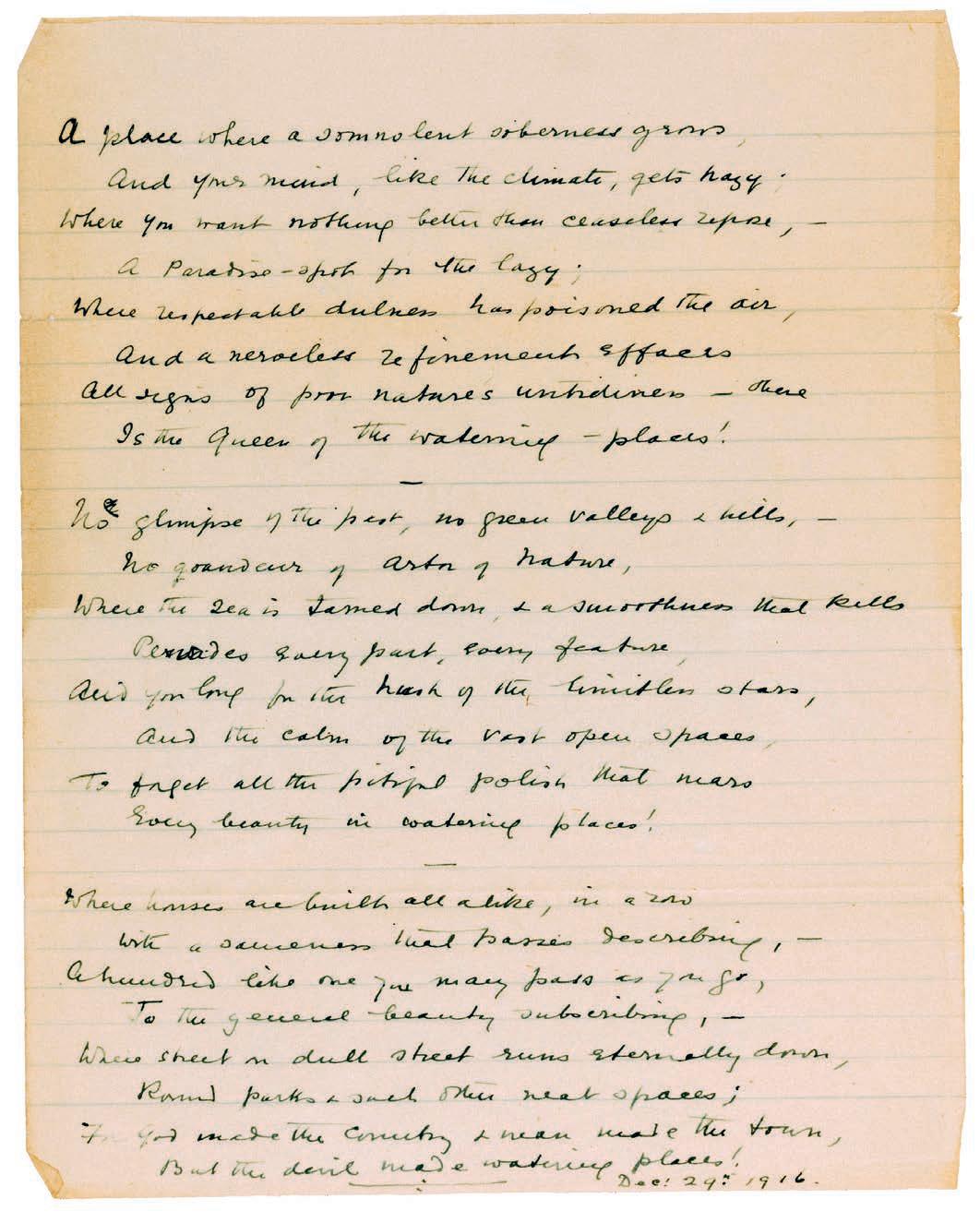

Charles Hamilton Sorley (C1 1908-13) himself had died some ten months before Atkey, killed in action on 13th October 1915 during the Battle of Loos. It is ironic that Marlborough’s greatest war poet should have died in one of the most pointless campaigns of a war whose pointlessness he had already depicted in his poetry. Lamented by Robert Graves as ‘one of the three poets of importance killed during the war’, Charles could be the awkward, maverick schoolboy genius, teasing beaks and Master, yet he mostly enjoyed idiosyncratic Edwardian Marlborough. Although he met his death aged only twenty, his letters and poems often display an extraordinarily mature judgement, alongside an innocent, youthful, impatient exuberance, as the letter he wrote to the Master of Marlborough less than a fortnight before his death shows:

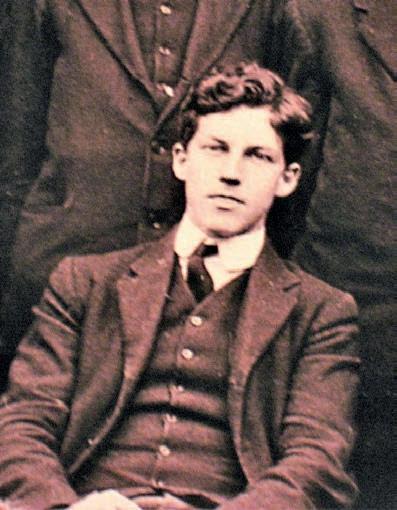

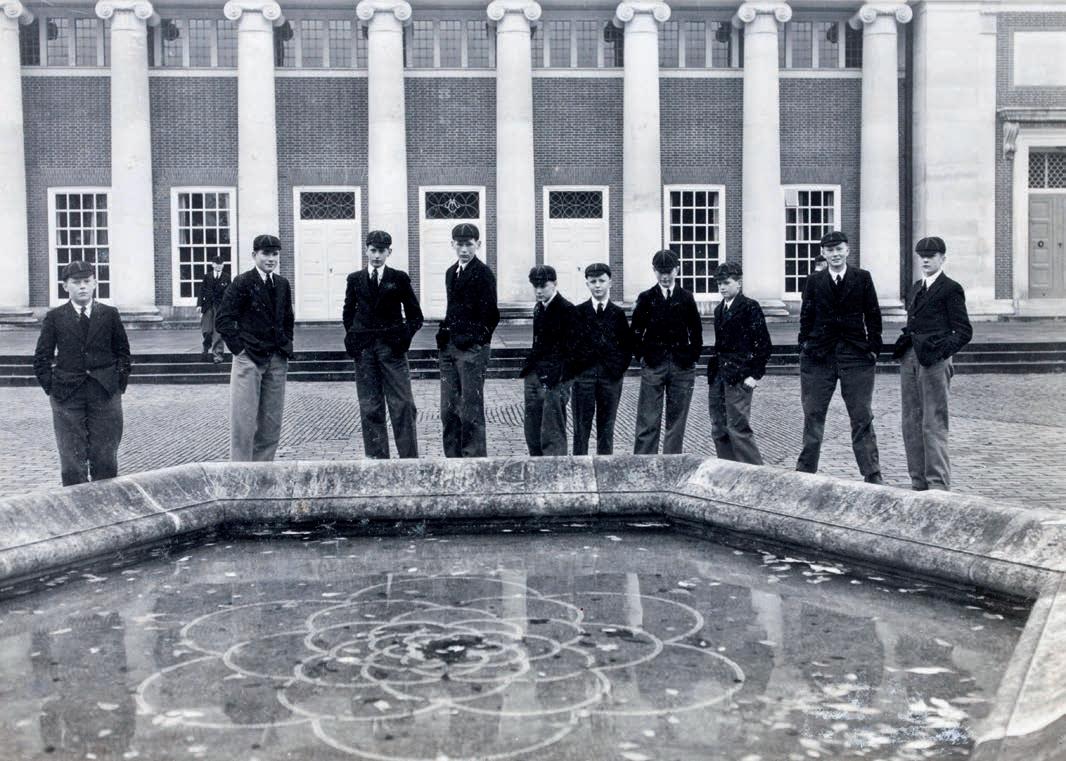

Above: Sorley in the Sixth Form

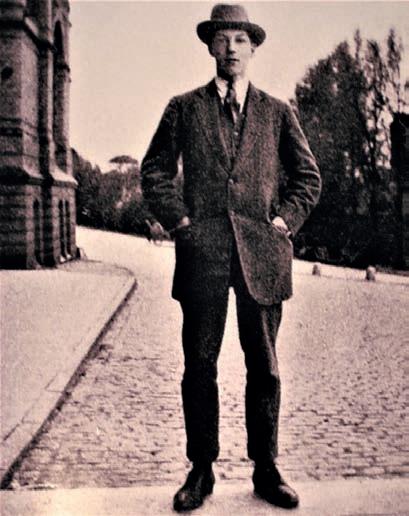

Right: Sorley after leaving College studying in Germany

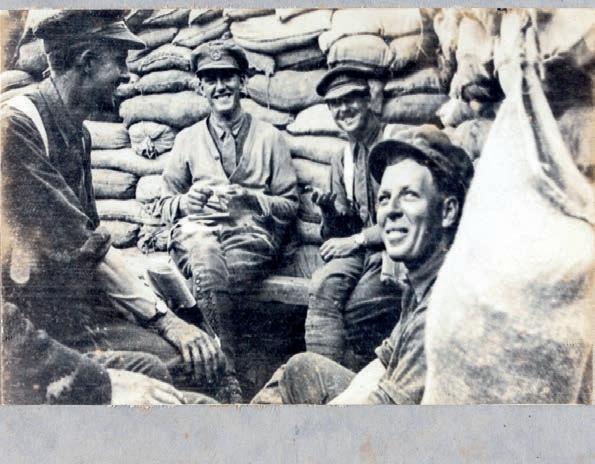

Below: Sorley at Camp (seated second from right)

I have just time (or rather paper, for that is at present more valuable than time) enough to send a reply to your welcome letter which arrived with the bacon. The chess players are no longer waiting so infernal long between their moves. And the patient pawns are all in the movement, hourly expecting further advances – whether to be taken or reach the back lines and be queened. ‘Tis sweet, this pawn-being: there are no cares, no doubts: wherefore no regrets.

Later that month that same Master, having heard of Charles’ death leading his company in the attack, was writing in eulogistic terms of his ‘rich, glowing personality, his vivid imagination and his power of interpreting it in words, his originality, his intense human sympathy, his high ideals and his lovableness’. The pain and sorrow that those back in Marlborough must have felt as the list of names grew weekly is hard to imagine. In addition to the Master, there would be other beaks with close links to those who were now dying in increasingly greater numbers. Imagine the anguish of a Housemaster such as John

O’Regan (B3 1907-12) mourning the loss of a quarter of the boys who passed through his House during the five years of his housemastership. In a poem, To Those of My House Who Have Fallen in the War, published in The Marlburian in June 1917, he tried to come to terms with the shadows which now filled his room:

Stars that now shine high in Heaven above me, Set by God there, for you heard His call; Stars, you to the end shall light my pathway Through the night which comes to one and all.

Likewise, John Bain (CR 1878-19), Classical scholar, poet and Master in Charge of the Army Class, who penned over 100 verse tributes to all those who were killed whom he had taught or he considered close friends. They make poignant reading, such as the tribute he paid to Charles Sorley (Scholar, Downs Lover and Poet) after the latter’s death at Loos in October 1915:

Sweet, singing voice from oversea, Lover of Marlborough and her Downs, Sure now thy Spirit, wandering free, Is hovering near the Toun of Touns

There where the bents and grasses wave And winds roar round the Hoary Post –No wormy earth, no gloomy grave

Shall hold thy homing eager ghost.

And Sorley himself paid poetic tribute to the young man who had been his contemporary at Marlborough, Sidney Woodroffe, In Memoriam SCW VC :

There is no fitter end than this. No need is now to yearn nor sigh.

We know the glory that is his, A glory that can never die. Surely we knew it long before, Knew all along that he was made

For a swift radiant morning, for A sacrificing swift night-shade.

And Woodroffe also found himself mourning the death of his predecessor as Senior Prefect in a tribute paid to Harold Roseveare (B3 1908-14) published in The Marlburian:

Never shallow, always loyal, considerate and affectionate, his friendship was such as is rarely found …. In all our sorrow, we cannot but envy him. All too short though it was, his life, if any can, can truthfully be said to have touched perfection. A happier boy one cannot imagine.

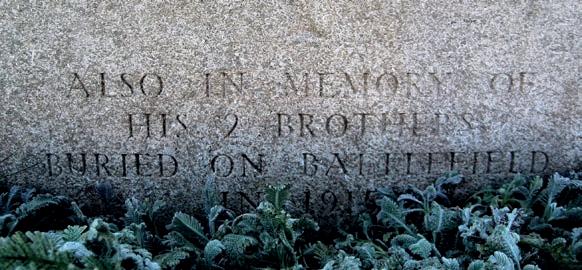

Another Marlburian family to suffer losses similar to the Woodroffes’ was the Giffard family, who lived at Lockeridge House a few miles to the west of Marlborough. Five of the six sons of Henry and Cecilia Giffard attended Marlborough College, three of whom were to die in the war. The first to be killed was field gunner Bob (CO 1898-01), serving as aide-de-camp to Major General SH Lomax, who was killed when the chateau being used as the headquarters building at Hooge was destroyed by German shellfire at the end of October 1914. It was this very ruin that was to become the focus of the fierce fighting in the summer of 1915 that was to take the lives of Sidney Woodroffe, Keith Rae, Guy Devitt (LI 1906-10) and Jack Lambert (CO 1906-08).

Bob’s younger brother Sydney (CO 1903-07) was also a gunner and took part in the Gallipoli landings in the early summer of 1915, where he found himself in charge of a battery after his commanding officer had been killed. Early in the morning of May 2nd, Sydney ‘was standing up in his dugout looking for targets and had just turned round to say that he couldn’t see any Turks, when a rifle bullet hit him in the left temple’. He was taken back to the beach, where his wound was dressed, but he died on a hospital ship that evening and is buried overlooking that same beach at the Lancashire Landing Cemetery.

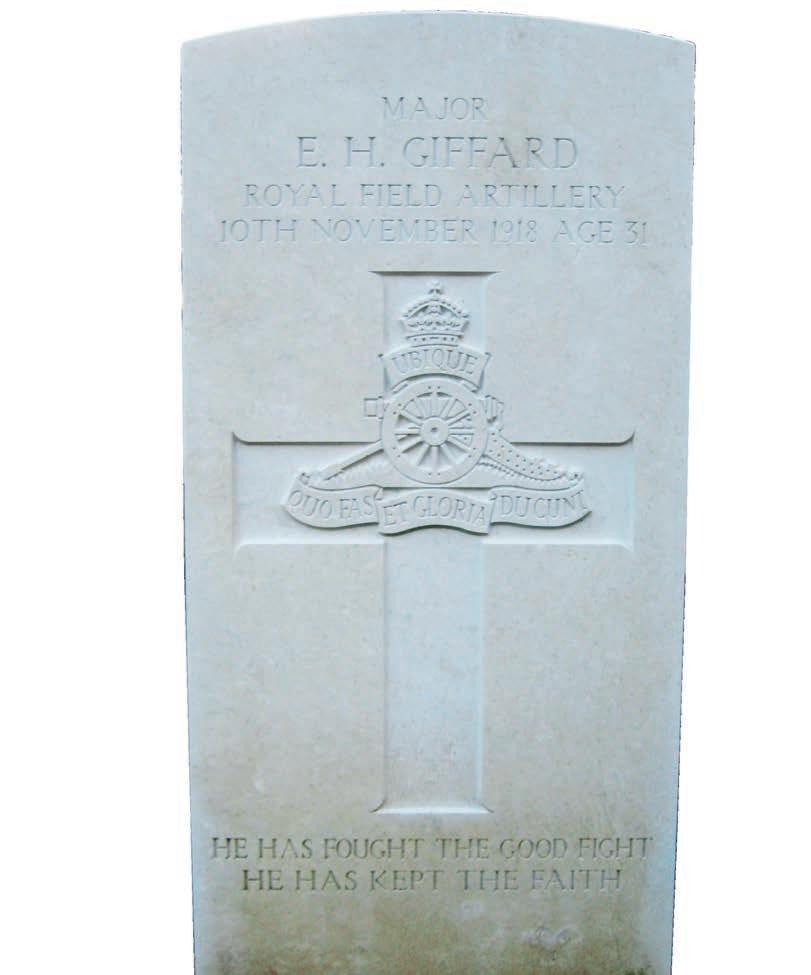

The third to die, tragically only one day before the signing of the Armistice in November 1918, was Eddie (CO 1901-05). He also trained as a field gunner and served as a major in command of a battery for two years almost continuously, until dying of wounds on 10th November 1918. Shortly before his death, Eddie had noted in his diary that he thought the Germans were giving up the fight. One of his friends wrote memorably of his service that it exemplified ‘the spirit of willing endurance’. There is a rather heartening postscript to this Giffard story in that the youngest brother, Walter, who was unable to serve alongside his brothers, having lost the lower part of his left leg in a shooting accident as a boy, became a balloon observer in the Royal Flying Corps so that he could be useful to his brother gunners.

Like Keith Rae, who has his own individual memorial on the edge of the Sanctuary Wood cemetery outside Ypres, Francis (known as Toby) Dodgson (B3 1904-07) also has his own memorial in the middle of a cornfield on the edge of the village of Contalmaison. It marks the spot where Toby died during the early days of the Battle of the Somme. Toby had just got engaged to Marjorie, the sister of his great friend Humphrey Secretan, and their letters are full of plans for their wedding. Toby is first reported as missing, but later that month Marjorie’s worst fears were confirmed in a letter from the Battalion’s commanding officer. The story does not quite end there, however. Another Marlburian contemporary of Toby and Humphrey, Charles Fair, meets and falls in love with Marjorie. They marry on 18th September 1917, and shortly afterwards the story comes full circle. By the end of the year Charles is back at the front

line and on 4th December writes to Marjorie: ‘I forgot to tell you that, in my wild chase after the Battalion, I passed within half a mile of Toby’s grave. It may have been a little fanciful but, as I passed the village, I raised my hand in salute because I owe him you, darling, and nothing can ever repay that debt to his memory.’

Young men dying in the prime of life is the common factor in so many of the stories that lie behind the names along the back wall of the Memorial Hall, none perhaps more so than the story of Hugh Butterworth (C2 1899-04). ‘I, H M Butterworth, a man of peace, possessed of few virtues, but rather a good off-drive, am sitting in a very narrow packed trench, about to take part in one of the biggest battles in History.’ So wrote Hugh on 16th June 1915, in one of his many letters to his great friend John Allen. This particular battle may not have turned out to be ‘the big one’ for Hugh, but there is no doubt that he was correct in his

estimation of his sporting skills. He represented both Marlborough and Oxford University at cricket, racquets, football and hockey and was a brilliant athlete. An injury prevented him from fulfilling his potential, but when family circumstances took him to New Zealand he turned to coaching all sports to the young pupils at the Collegiate School, Wanganui. When war broke out, he returned to England out of a sense of duty to play his part.

The Battle of Bellewaarde Ridge raged for most of the summer of 1915, into the autumn and beyond. It was one of those many situations around Ypres throughout 1915-1917 where both sides quite literally slogged it out against each other to no particular purpose and with few tangible results. Into this cauldron stepped Hugh, bringing with him that love of life which characterises his every word and act. On 15th September Hugh writes: ‘We expect to lose about half the battalion and practically all the officers. I put the betting on my own survival at about three to one against, but it is all luck and I’ve got a sort of habit of scrambling through things.’ Hugh died ten days later. Earlier in July he had written: ‘I’m not particularly afraid of death, but I dislike the thought of dying because I enjoy life so much. I fancy that when we warriors fetch up at the Final Enquiry they’ll say, “Where did you perform?” We shall reply: “Ypres salient.” They’ll answer, “Pass, friend,” and we shall stroll along to the sound of trumpets and sackbuts.’

Ten years younger than Hugh and still at school when war broke out, Charles Prangley (C1 1911-15), or ‘Doox’ as he was known at school, does not appear to have had much ability in sports, but he showed an early interest in the Army, and by the time that he left in 1915 he had attained the rank of second lieutenant. He gained a commission in the Lincolnshire Regiment and was ordered to report to Tynemouth for training. His arrival in France coincided with the Battle of the Somme, and he was thrown into combat straight away. He died on Monday, 25th September 1916, on the opening day of the Battle of

Morval, one of the 174 officers and men of the Regiment lost that day, being killed instantaneously by a shell splinter. After his death, his former headmaster wrote of him:

‘I picture the boy, as I write, slight, delicate, refined, with a certain wistfulness in his eyes; in appearance, he was little more than a child, but he had a man’s soul and did a man’s deeds.’

Doox is also commemorated in a most remarkable illuminated missal, decorated in his memory by a friend of the family, who was commissioned by his father, Rector

of St Mary’s in Bexwell, Norfolk. The calligraphy is astonishing, but the real beauty lies in the decoration, which appears on every page and tells the short life of Doox. On the dedication page appear the coats of arms of Marlborough and Jesus College, the badge of the Lincolnshire Regiment and the banner of France. On subsequent pages, there follow drawings of the font at which Doox was baptised; of St Mary’s, Bexwell; of St Margaret’s, Lowestoft, which Doox would have attended from his preparatory school; of Marlborough College Chapel; of Jesus College, where he had secured a place; and entwined within ears of wheat, grapes and vines is the name Doox. The cover of the book is of wood taken from a tree in the rectory garden, and, most poignant of all, on the front cover is a gold cross formed from his mother’s wedding ring.

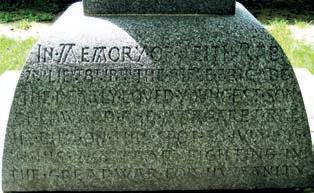

Not every one of the 749 Old Marlburians who died in the war left such a rich legacy, but each and every one is individually remembered and honoured in the hall that was built to commemorate them, and in the Roll of Honour. The inscription at the base of a white cross raised in memory of Doox on the boundary of Bexwell parish serves as an appropriate epitaph for all of them, and a message to us 100 years on:

All that we had we gave All that was ours to give Freely surrendered all That you in peace might live. In trench and field and many seas we lie We who in dying shall not ever die If only you in honour of the slain Shall surely see we did not die in vain.

David Du Croz (CR 1996-07) former Head of History

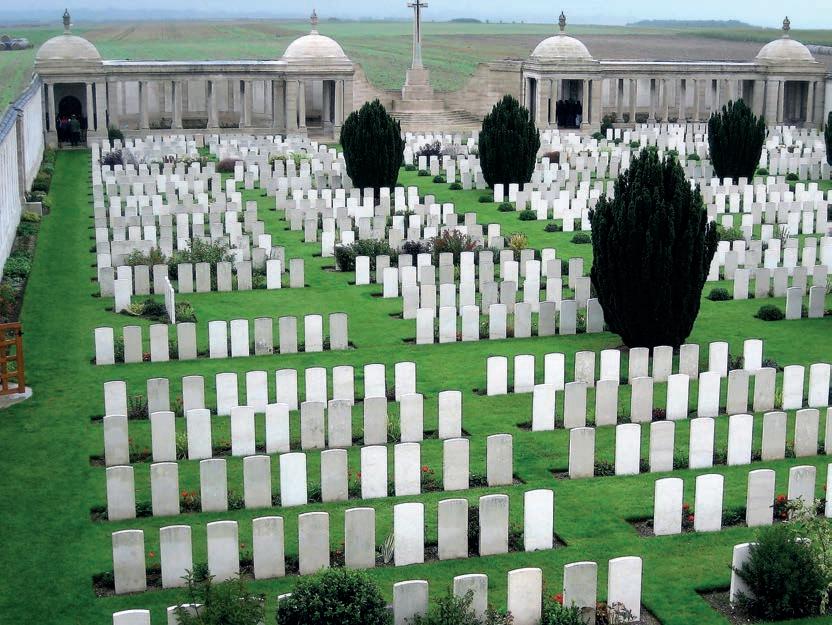

Long before the First World War came to an end, ways of commemorating the fallen were already being discussed widely. The total loss of lives in the British Empire was well over a million, and the social and psychological damage caused found a healing expression in a desire to make memorials to honour those who had died.

There were uncertainties after the war regarding both the financial outlook and the availability of construction materials, but many ambitious projects were commenced. Most other forms of building project ceased and the architectural profession, with little other work available, produced a rich array of ideas to honour the lives that had been lost. Apart from regimental and Boer War memorials, war memorials were, as Clive Aslet has observed, a previously unknown building type, and ‘with no precedent to follow, the memorials to the dead – along with the ceremonies that went with them – had to be invented afresh’.

Schools comparable to Marlborough each lost approximately the same number of former pupils as the size of their annual pupil community. Almost one in five of those who enlisted died. Across the country, innumerable crosses, gateways, obelisks, panels, plaques, statues and windows tell the story of the fallen, and some schools erected

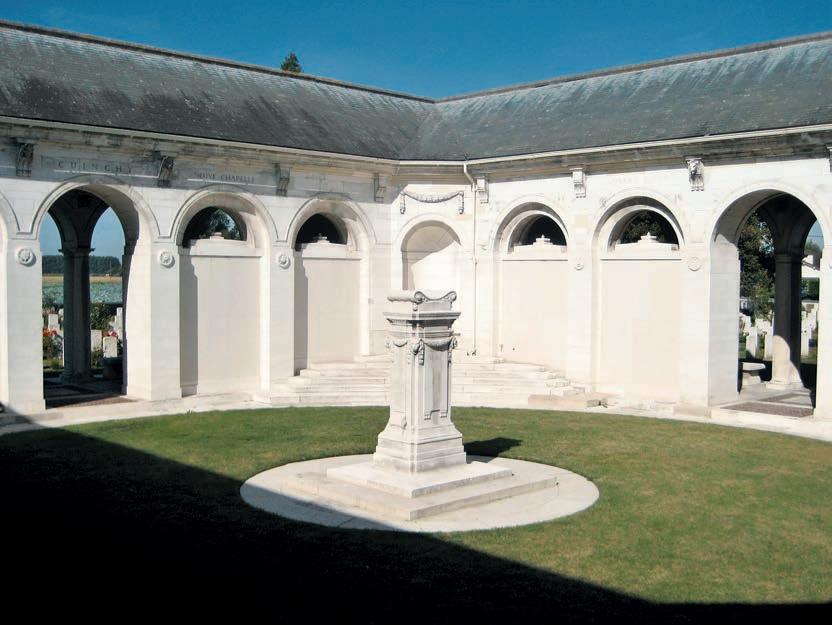

commemorative buildings which, in addition to being important reflections of the catastrophe, are remarkable works of art and architecture. Collectively, they form an important part of the nation’s heritage, but they are not as wellknown as they should be, even although many of them were the work of the country’s most famous architects. Perhaps the finest of these memorials is Winchester College’s cloister of 1924 completed to designs by Sir Herbert Baker, the great imperial architect who had collaborated with Edwin Lutyens at New Delhi and with work for the Commonwealth war cemeteries. Baker’s fine neo-Jacobean war memorial building for Harrow was

completed in 1926, while Haileybury waited until 1932 before Baker’s great domed dining hall was finished. The largest memorial in the country was Charterhouse’s Albi Cathedral-inspired chapel, completed to designs by Giles Gilbert Scott in 1927. Numerous other fine memorial chapels were also built, for example, at Barnard Castle, Bishop’s Stortford, Bromsgrove, Dean Close, Ellesmere, Monkton Combe, Durham, Oundle, Oakham and Sutton Valence. Many existing chapels were enhanced, notably those belonging to Brighton, Epsom, Rossall, Sherborne, Tonbridge and Wellington, and above all Lancing, where the famous chapel acquired a 100-foot-long cloister to designs by Temple Moore.

Cheltenham College and Sedbergh also built cloisters. At Rugby, Sir Charles Nicholson built an impressive vaulted memorial chapel in pale stone to stand beside the main chapel. Ernest Newton added a richly decorated octagonal memorial shrine to the chapel at Uppingham, in addition to designing the school’s fine memorial hall. Clifton and Radley erected noble memorial gateways by Charles Holden and Thomas Graham Jackson, and the beautiful library by Ernest Gimson was completed at Bedales. Eton’s memorial consisted of bursaries, a great wall of bronze plaques and the Libro d’oro in the memorial chapel, which records the 1,158 boys and masters who died.

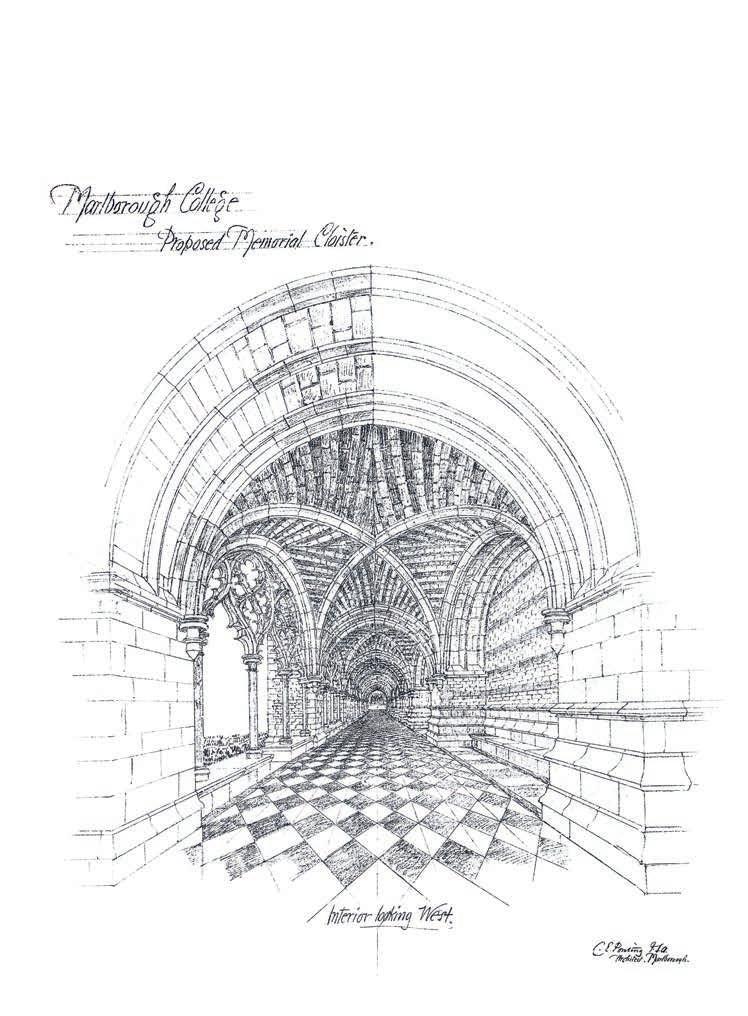

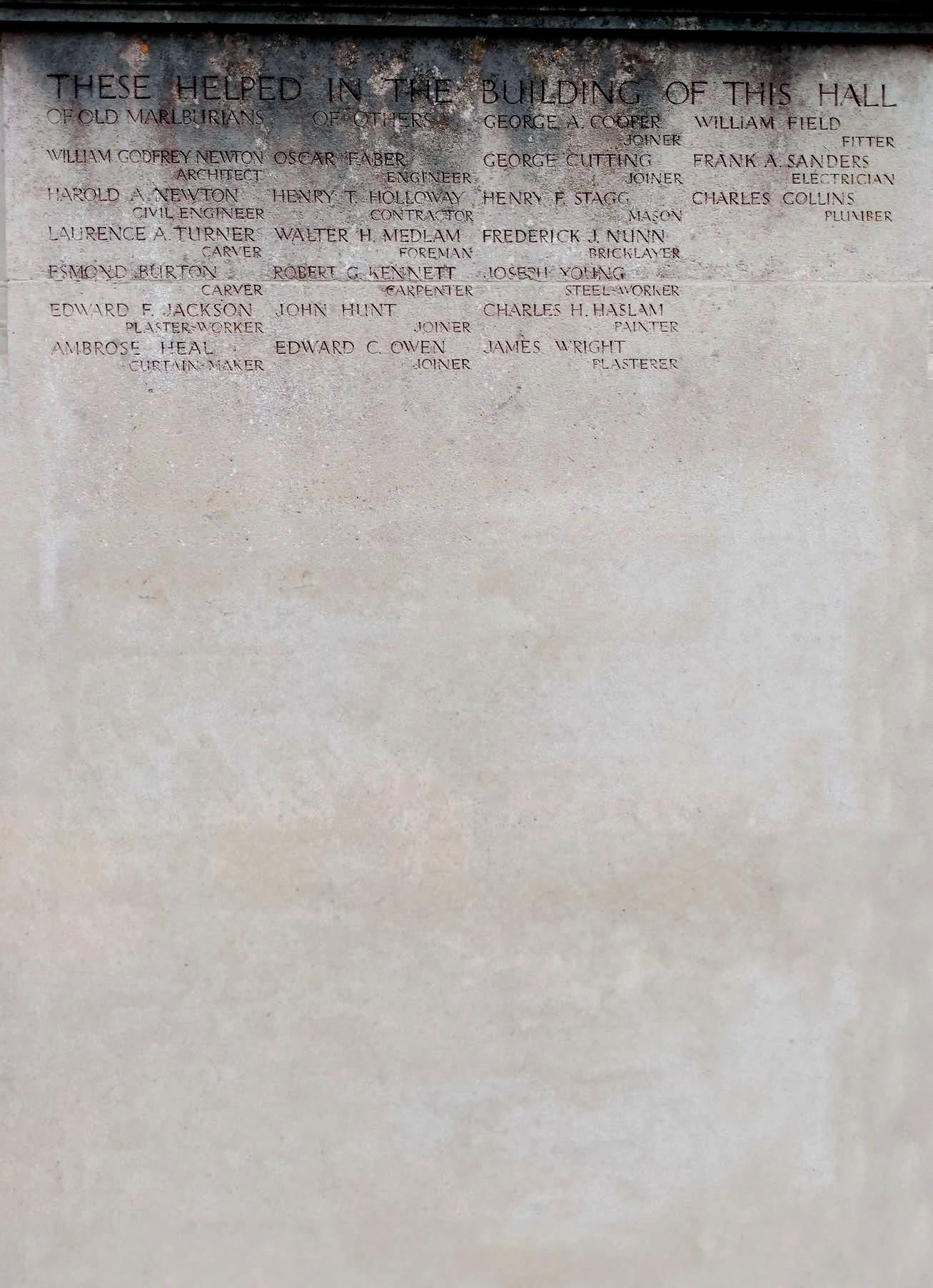

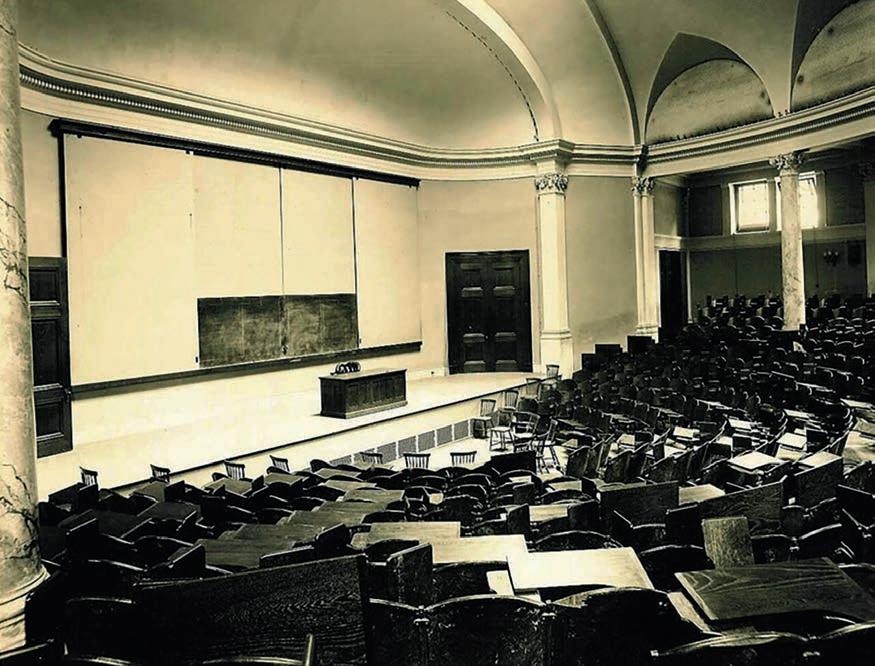

Apart from Eton, no school suffered more casualties than Marlborough. The loss of 749 lives resulted in a sense of urgency to commemorate the fallen and, before this dreadful total was reached, in April 1917, a meeting of Old Marlburians agreed there should be a memorial building and a fund for the education of the children of Marlburians who had died in the war. Consideration was given to a cloister to designs by Charles Edwin Ponting, a distinguished local architect who had already worked for the College. This would have run along the south side of the Chapel, and it was noted that the building’s original architects, George Frederick Bodley and Thomas Garner, had considered a cloister here. There was even some discussion about establishing a clubhouse in London where Old Marlburians could meet. However, in October 1919, a committee met at the Central Hall, Westminster and voted 149-1 in favour of a speech hall. Many schools debated whether a memorial should have any function beyond remembering the dead, and

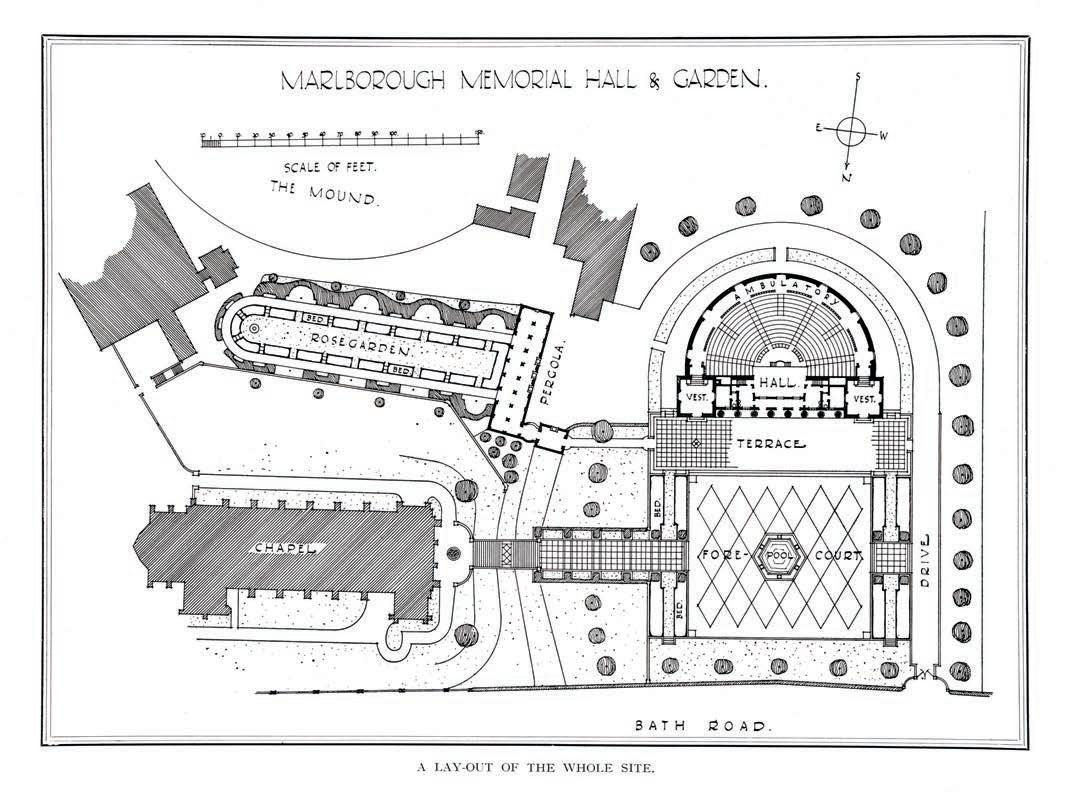

serve no utilitarian purpose at all, but the feeling at Marlborough was that any memorial should help to make the school a better place and there was a need for an assembly hall. There was ‘a strong preference for a Hall in the Amphitheatre style’, and it was felt the architecture should in some way to reflect the design of the C House, the early eighteenthcentury mansion in which the school had started in 1843. The committee also chose the site described as ‘the

water meadow below the chapel adjoining the Bath Road’. Just before the war this site had been rejected as a site for a new boarding house because of the challenges presented by building on a site with such a problematic water table, but it was felt that the difficulties presented could be solved by new developments in construction technology. Facing considerable financial uncertainties, the process of raising funds for a worthy memorial building began.

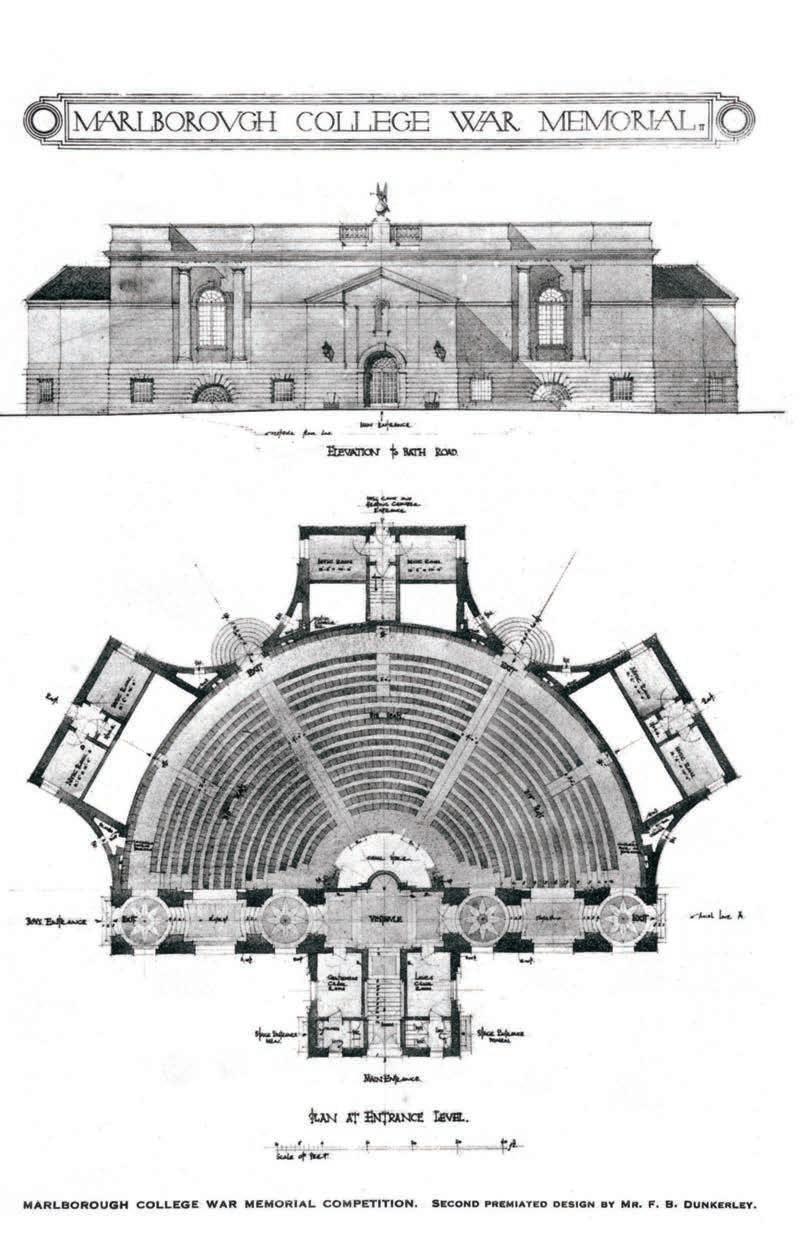

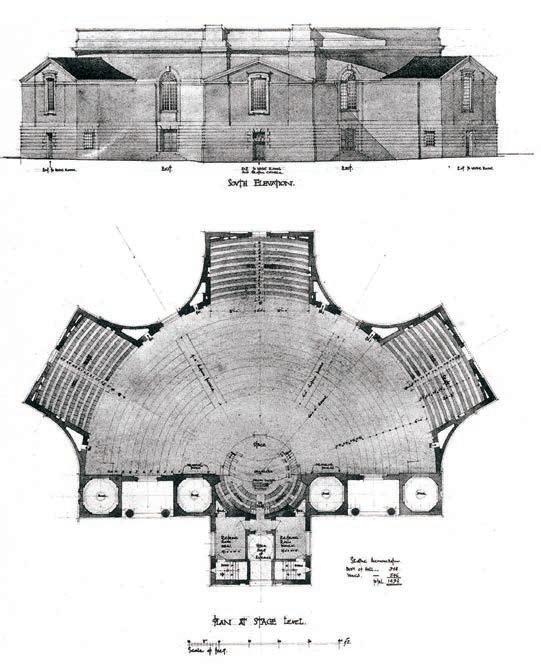

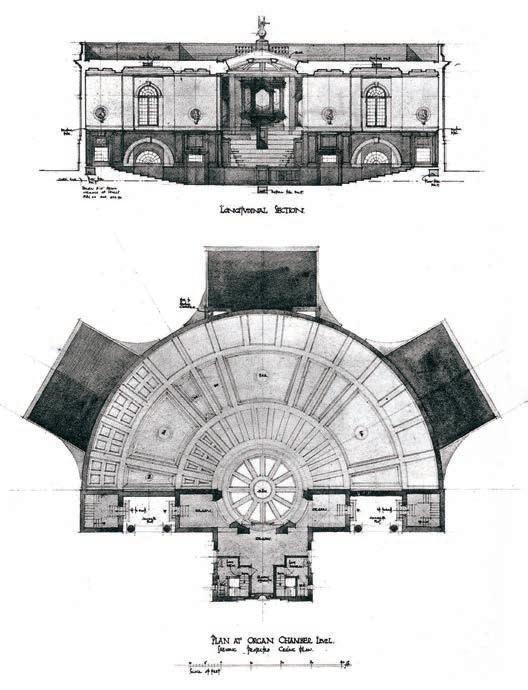

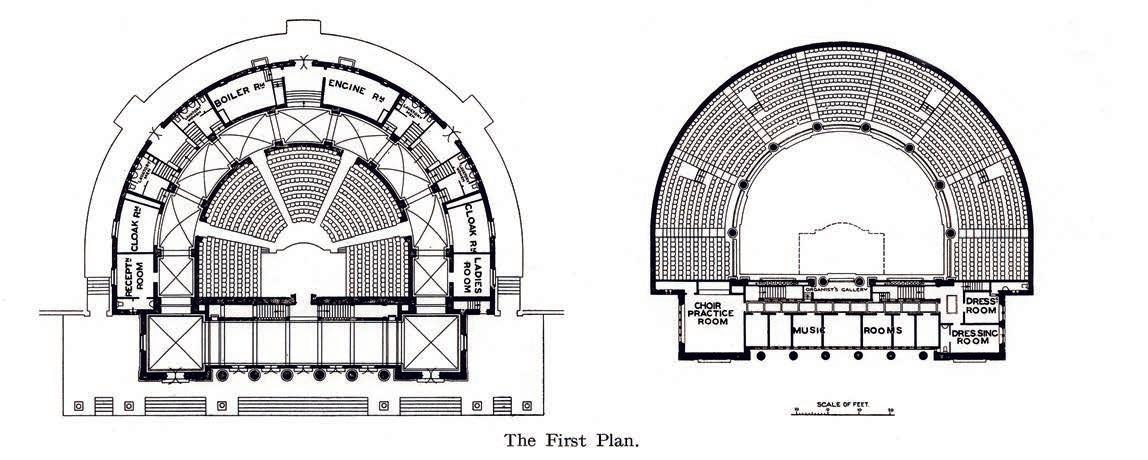

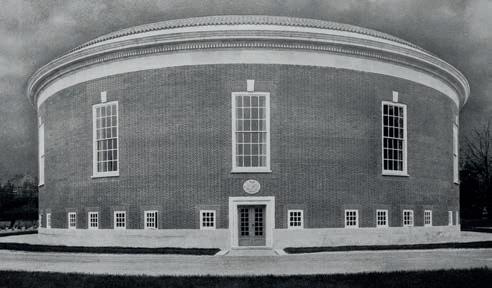

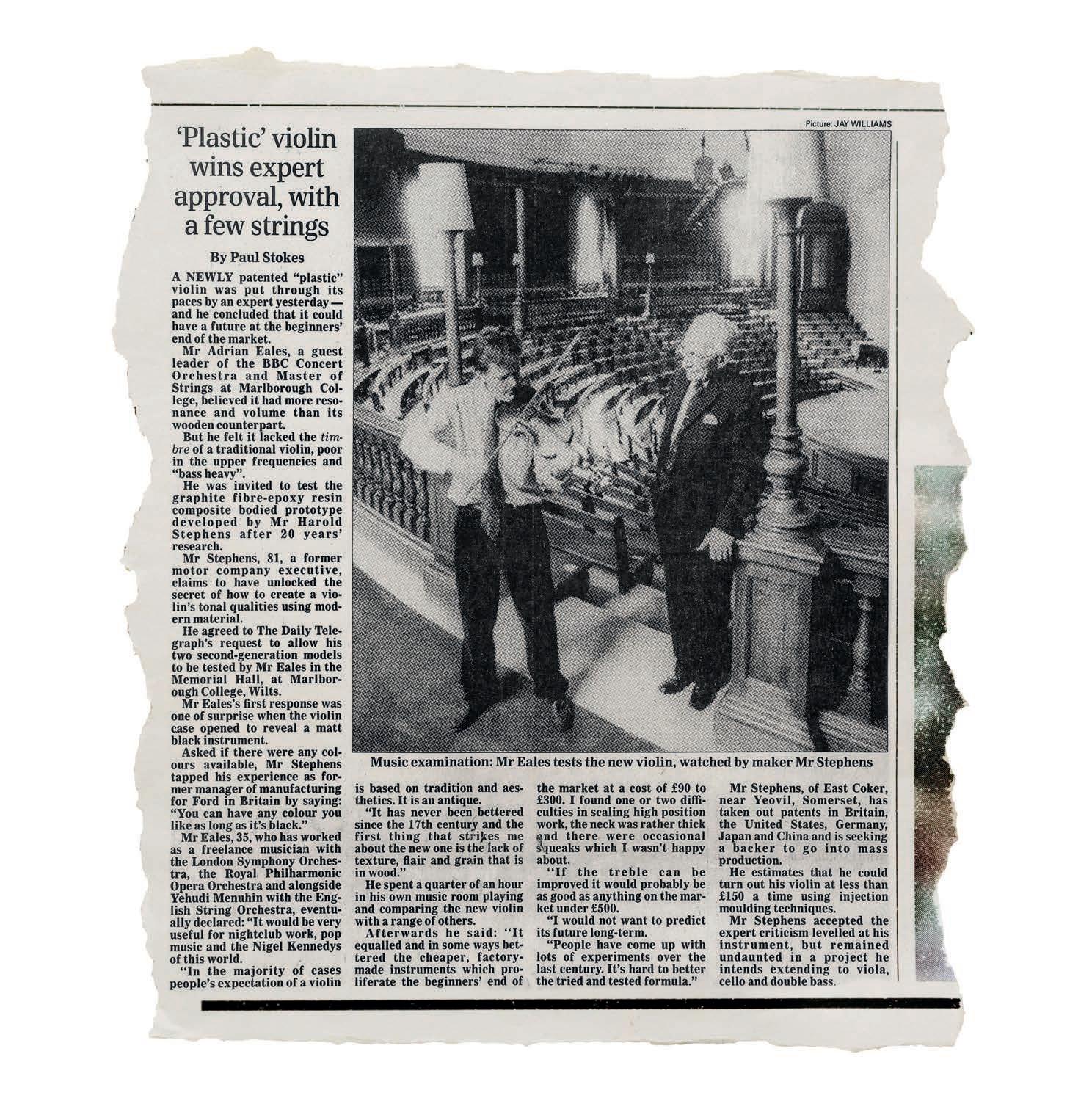

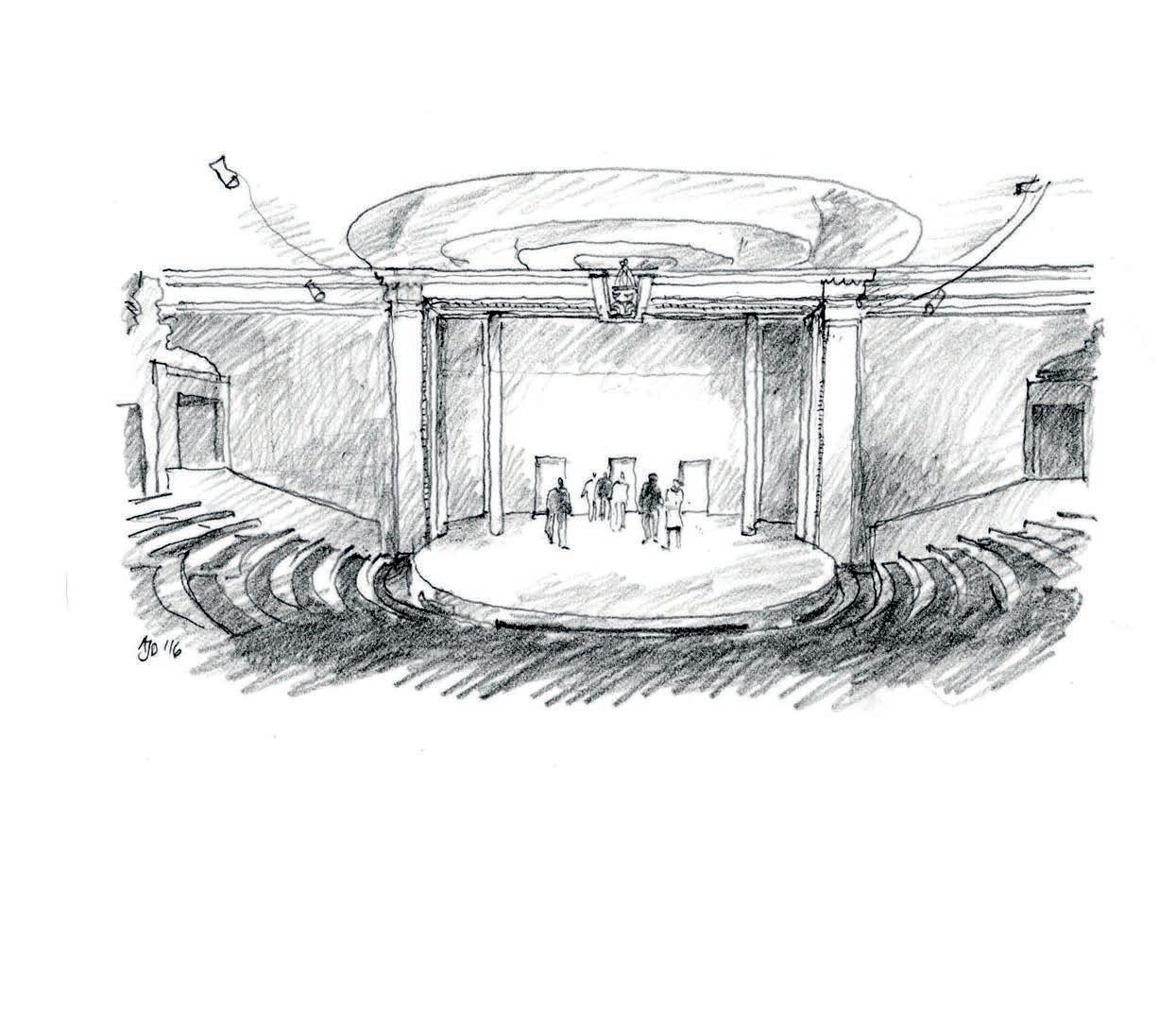

The Master, Cyril Norwood (CR 1916-25), and Ernest Burrell Baggallay (SU 1891-96), Honorary Secretary of the Marlburian Club, decided that the architect of the Hall should be an Old Marlburian, and appointed Royal Institute of British Architects President John William Simpson, future co-architect of the former Wembley Stadium, to assess the competition. To narrow the field, Simpson picked a selection of architects, who were invited to submit plans by 14th August 1920. The runner up was a design by the Manchester-based practice of Frank Dunkerley (CO 1883-85). His building was an amphitheatre with a circular stage, which was flanked by oak memorial panels and overlooked by an organ chamber. A shallow dome formed the central part of the roof and there were three radiating transepts with coffered barrel vaults. Dunkerley’s splendid design was illustrated and described in The Builder in April 1921, but the building would have been close to the Bath Road and blocked the view to the west from the Chapel, and it was felt that this vista should be preserved. Among the other designs

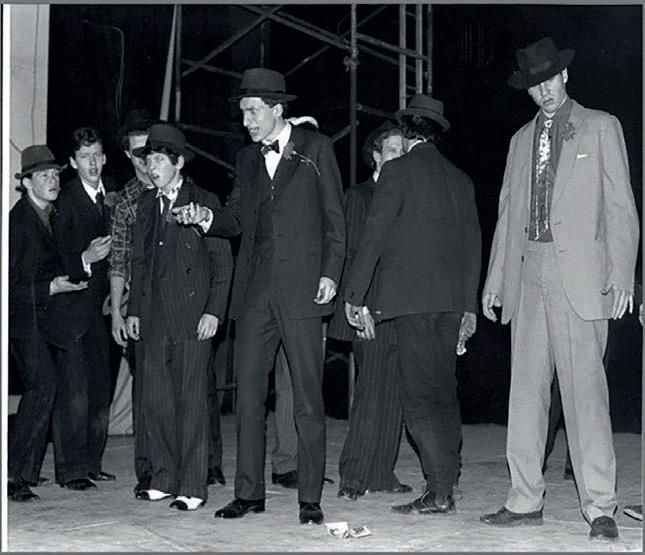

considered in the competition, one had a semicircular frontage towards the road, and another had a low-proportioned dome. The committee had no doubt favoured the amphitheatre form because of its suitability for speeches and assemblies and because of its associations with the Classical world, which was so prominent in the school’s curriculum. There are two interesting examples of this building type in other schools: The Speech Room of 1871 at Harrow, a fine semi-circular hall designed by the great Victorian architect William Burges, which combines Classical theatre with the romantic language of the Gothic revival; and the outdoor theatre at Bradfield known as the ‘Greeker’ – inspired by Frank Benson’s June 1880 Oxford production of the Agamemnon of Aeschylus – which was built in a disused chalk pit in 1890 as the result of an initiative of the headmaster, Herbert Gray.

The winner of the competition for the Hall, chosen in December 1920, was William Godfrey Newton (C1 1899-04), the son of the

celebrated Arts and Crafts architect Ernest Newton. To begin with, the designs for the Hall were under the name of Ernest’s practice. In many ways William was the ideal architect for Marlborough. He had helped with the memorial building work at Uppingham which his father had commenced in the last years of his life, and he completed the work there after his father died in January 1922. He was an architect who had experienced the war, having served in the Artists Rifles and been awarded the Military Cross. Like his father, he valued teamwork and the importance of careful attention to detail, and he enjoyed a distinguished career producing fine buildings for schools such as Aldenham, Bradfield, Radley and, above all, Merchant Taylors’ School, which moved to a new site at Northwood in 1933. He also became a well-known writer because of his work as editor of The Architectural Review, and he befriended some well-known artists during his professorship at the Royal College of Art, notably Eric Ravilious, who helped with the work at Merchant Taylors’.

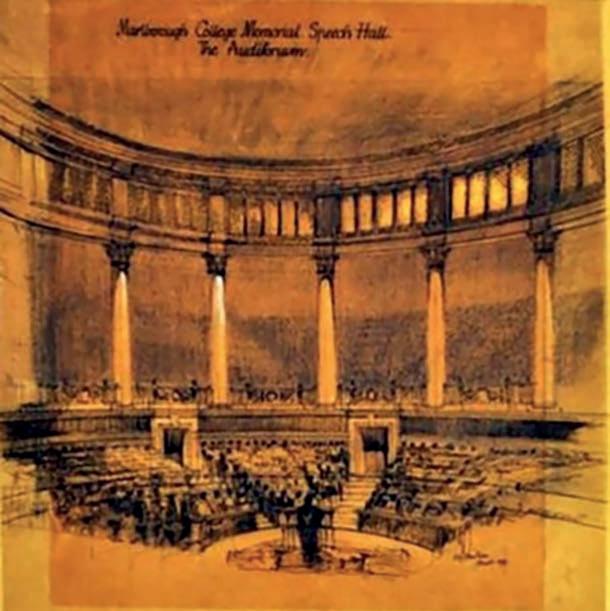

For the Marlborough work, Newton gathered a group of craftsmen and builders, including the Old Marlburians Ambrose Heal (LSch 1885-87), Laurence Turner (C1 1877-81) and Esmond Burton (C3 1899-01). Heal was the distinguished early-twentiethcentury furniture maker whose family founded the eponymous store, and Turner was a celebrated mason and restorer of country houses who became president of the Art Workers’ Guild. Burton, another member of this famous guild, had learned his considerable skills as a stonemason from Turner. On the western wall of the Hall there is a tablet with the inscribed names of those who were involved in executing Newton’s building: all were deemed equal. Heal is described simply as a draper and Turner and Burton as carvers.

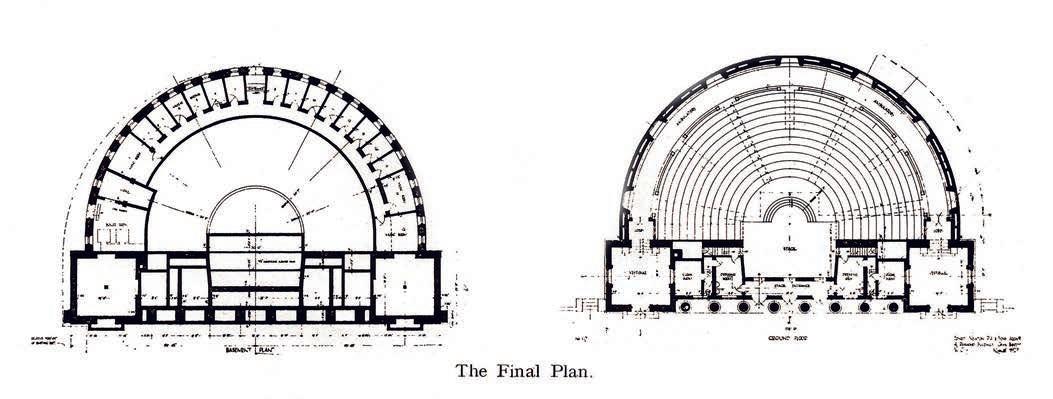

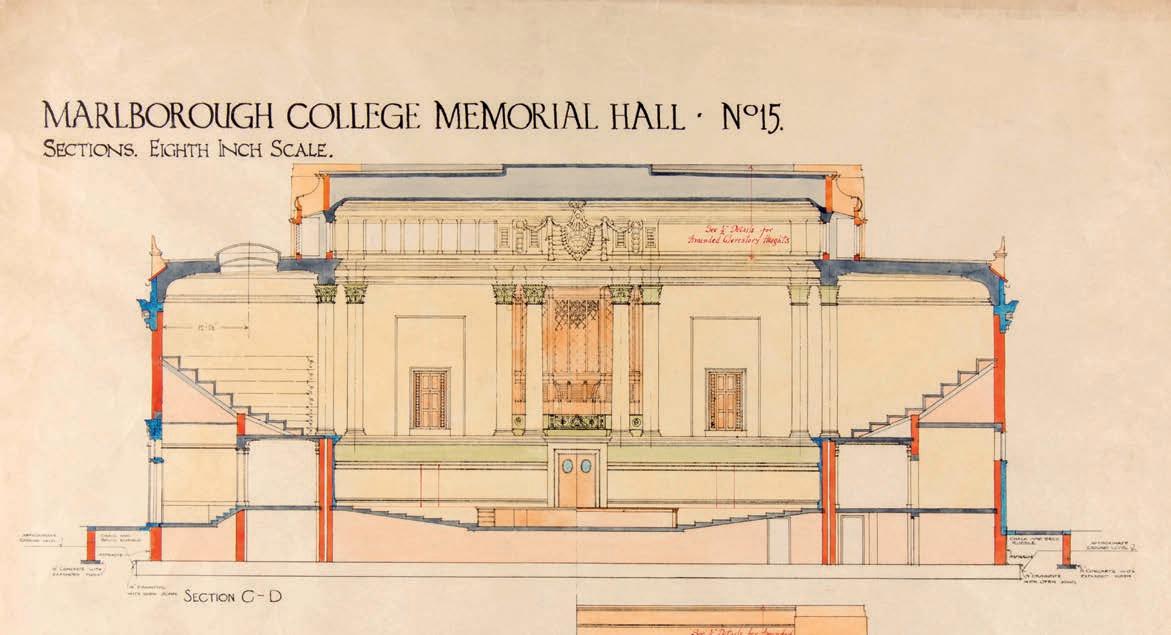

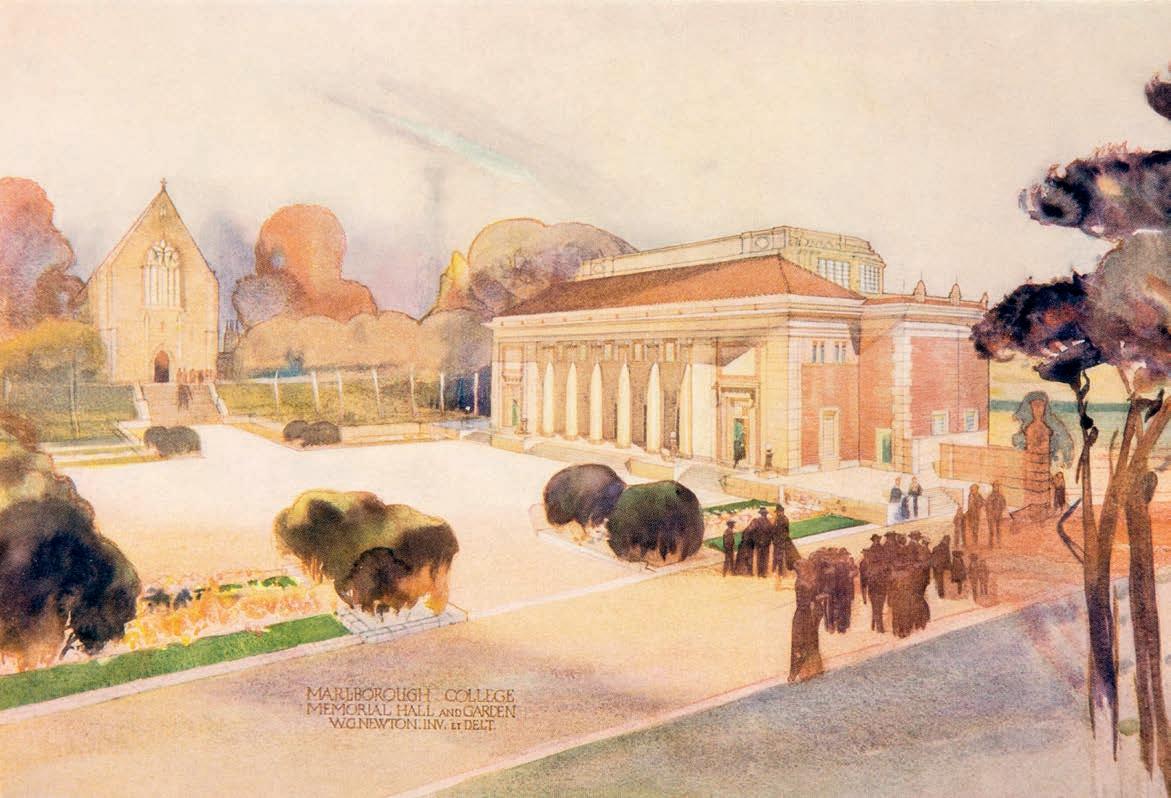

Newton’s first design for the speech hall was very ambitious, with seating for 1,500, a great columned ambulatory, a Baroque-inspired screen above the stage and a band of high clerestory windows above the auditorium. There was no proscenium arch because the building was not intended for theatrical performances. The ambulatory’s projecting walls framed the building’s northern façade with its six great columns, and a parapet which marked the level of the clerestory windows arose above the tiled roof. The Hall’s Classicism and its entrance front, set well back from the Bath Road, were designed to contrast with and complement the Gothic Chapel, which stands on the raised site above the Hall. To tackle the problems presented by the watery site and the construction of the concrete raft that the building required, Newton worked with Oscar Faber, the influential pioneering structural engineer, and his own elder brother, Harold Newton (C1 1896-00), a civil engineer.

Initially, the total cost of the work was estimated at £100,000, but it was believed that building costs would fall and the appeal for funds was delayed by a year. However, the costs did not fall as much as anticipated, with the re-estimated cost of the scheme being £70,000. It became clear that a simpler design

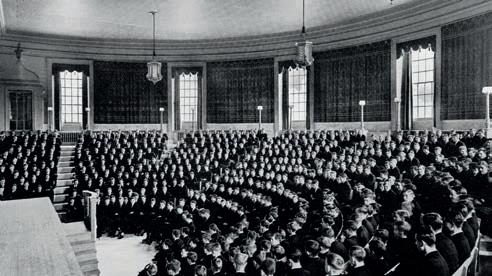

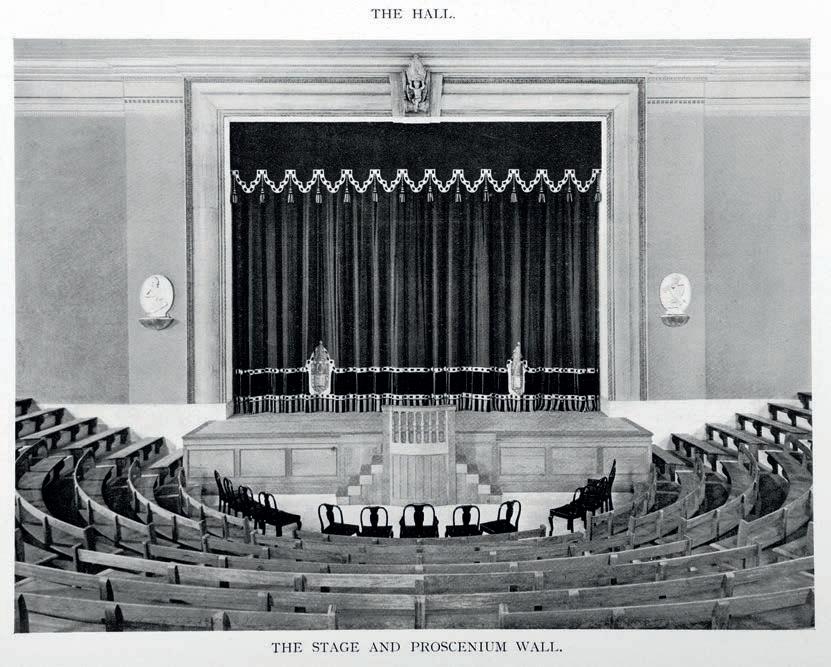

was necessary, but rather than commencing afresh, the plans were whittled down with great skill, so that in the finished building there was, as a critic observed, no trace to be seen of the pruning knife. Newton faced considerable challenges and disappointments as he worked on plans for the smaller building. He also had to manage an extended brief. As well as being a speech hall and a concert hall with rehearsal rooms, the building now had to be suitable for theatrical productions. A second design was replaced by a third, but the backstage arrangements remained awkward. It was hoped that the new building would seat 1,150, and there were discussions about whether the average boy required a 14-inch or 16-inch sitting space. In the end, when packed, the Hall could seat just over 1,000.

At Prize Day in 1922, Norwood declared that the cost of the building would be in the region of £40,000, although only £30,000 had been raised by that time. Regardless of the considerable worries about funding, work proceeded, and Norwood declared that the community was building ‘in faith’. In the end, this revised building cost £53,000. Today, the changes of course and the risks taken in the Hall’s construction seem remarkable, but they underline the great sense of urgency which drove

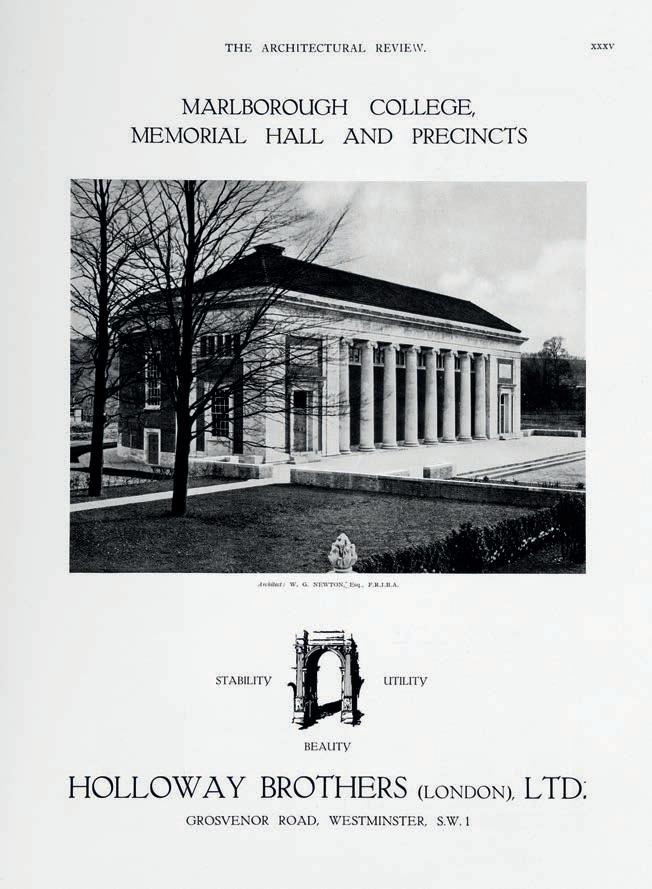

this work. The Memorial Hall was supposed to be opened in the autumn of 1924, and several celebrities were asked to be at the ceremony, including Marshal Foch. However, on 21st July, just two months before the great day, the committee responsible for building the Hall was alerted by Newton that the building appeared to be sinking, and cracks had appeared in some walls. When the design was changed it had been supposed that the lighter building would be secure on the foundations that had been intended for the grander first design, even though the weight distribution differed. The new design had been inspected and all was deemed to be well but now, to avert disaster, piles had to be sunk quickly on the southern side of the building and horizontal girders were inserted beneath it to assist the concrete raft on which the building rested, adding another £2,600 to the cost. Somehow, most of this sum was recovered by through making economies and Newton charged no fees for his work. The construction of the Hall must have tested the expertise of the distinguished contactors, Holloway Bothers of London, a leading company specialising in large-scale building and heavy civil engineering work, which was responsible for many important projects, such as the rebuilding of the Old Bailey and the Bank of England.

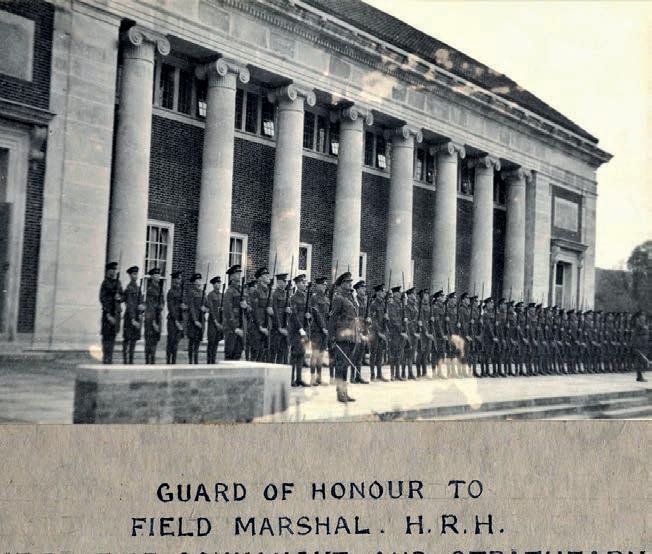

At last, the work was completed, and on 23rd May 1925 the Hall was opened by the Duke of Connaught and Strathearn. The legacy of the altered design and some of the original plans have lingered on in Marlborough’s oral history. Even in recent times, Old Marlburians have expressed a belief that the original plan was for a circular building, and the story of the building sinking was once well known. The occasional flooding of the basement has reminded the school that water is an important feature of the ancient site surrounding the neighbouring Neolithic Mound.

At the opening of the Hall, Norwood commented that words had been used sparingly in the decoration because it was felt that the language of inscriptions was bound to become out of date. Therefore, it had been decided there should be just one word, ‘Remember’, over the lintel of the entrance doors. He praised the simplicity and beauty of the scheme and explained the unified nature of the work with its numerous components:

Our Memorial begins immediately as you step through the great West door of the chapel, and its ideal is carved on the stone of Remembrance at your feet, ‘Let us make earth a garden in which the deeds of the valiant may blossom and bear fruit.’ You stand there and you look to the west and the setting sun … and you have the whole, the great steps, the forecourt, the terrace, the hall itself and the garden beneath your feet, a hallowed acre, over which the chapel presides, and of which it is an integral part. It was in order that our most sacred building might be exactly there that we undertook the great labour of raising this hall on a site which was difficult and insecure: now that by the skill of our architect and the engineers we have succeeded, it seems to have been well worth doing.

The original ‘stone of remembrance’ described by Norwood eroded, partly because palm crosses used to be burnt on top of it in preparation for use at Ash Wednesday in the following year. It was replaced in 1991 by wall-mounted roundels at the top of the Chapel steps, close to the site of the old stone.

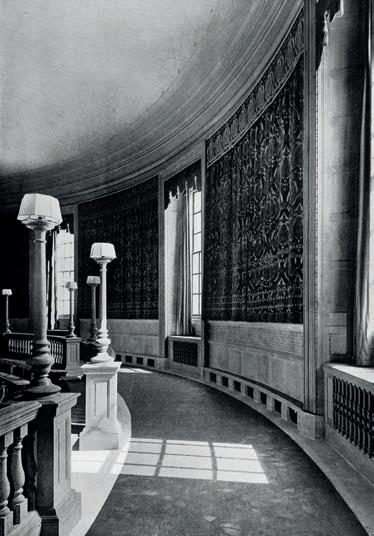

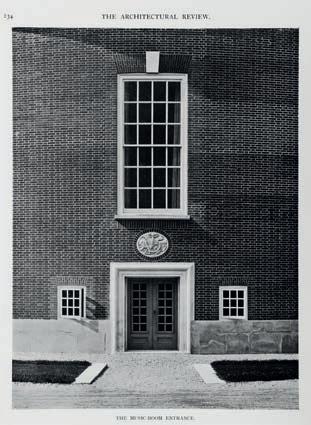

The Hall, as built, may be less spectacular than the first design, but it is an impressive building in a form of stripped Classicism, a style which became popular in the years between the wars. This architecture rejected overblown turn-of-the-century taste and reflected the desire for order and stability in the inter-war years. At its best it can be an imaginative, refined and pared-down reinvention of Classicism, but it was also appropriated by totalitarian regimes in the 1930s, with overpowering results. Newton’s interpretation of Classical grammar presents a striking spectacle to travellers passing by the College on the A4, but although it is imposing, the Hall also speaks of restraint. The north front is red brick with stone dressings, with closed end bays, which were deliberately left free of ornament or inscriptions. These frame a loggia of eight giant plain Portland stone columns (replacing the six of the original design) with fluted Ionic capitals surmounted by a parapet, with a cornice which reflects Newton’s understanding of the language of Classicism. The fine two-inch bricks used by Newton result in rich wall surfaces that accentuate the use of stone in the building. The semicircular southern wall of brick is punctuated by the seven tall windows of the auditorium, the square windows of the basement and a southern entrance, which was later given a second entrance reached by twin staircases. At their summit the stairs are adorned by an oval panel of stone carved musical instruments, which was once placed in the wall immediately above the south door.

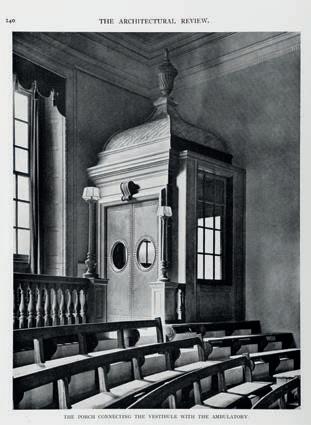

The Hall can be entered through three central doorways, which lead to the area behind the stage, but the main entrances are through the stone-walled foyers with shallow saucer-domed ceilings to the east and west, followed by glazed wooden gazebo-like lobbies, with the western one containing the cabinet which

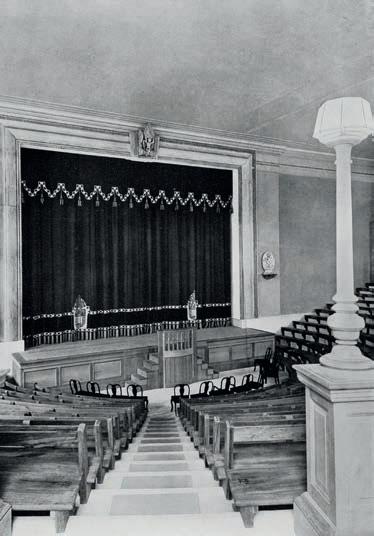

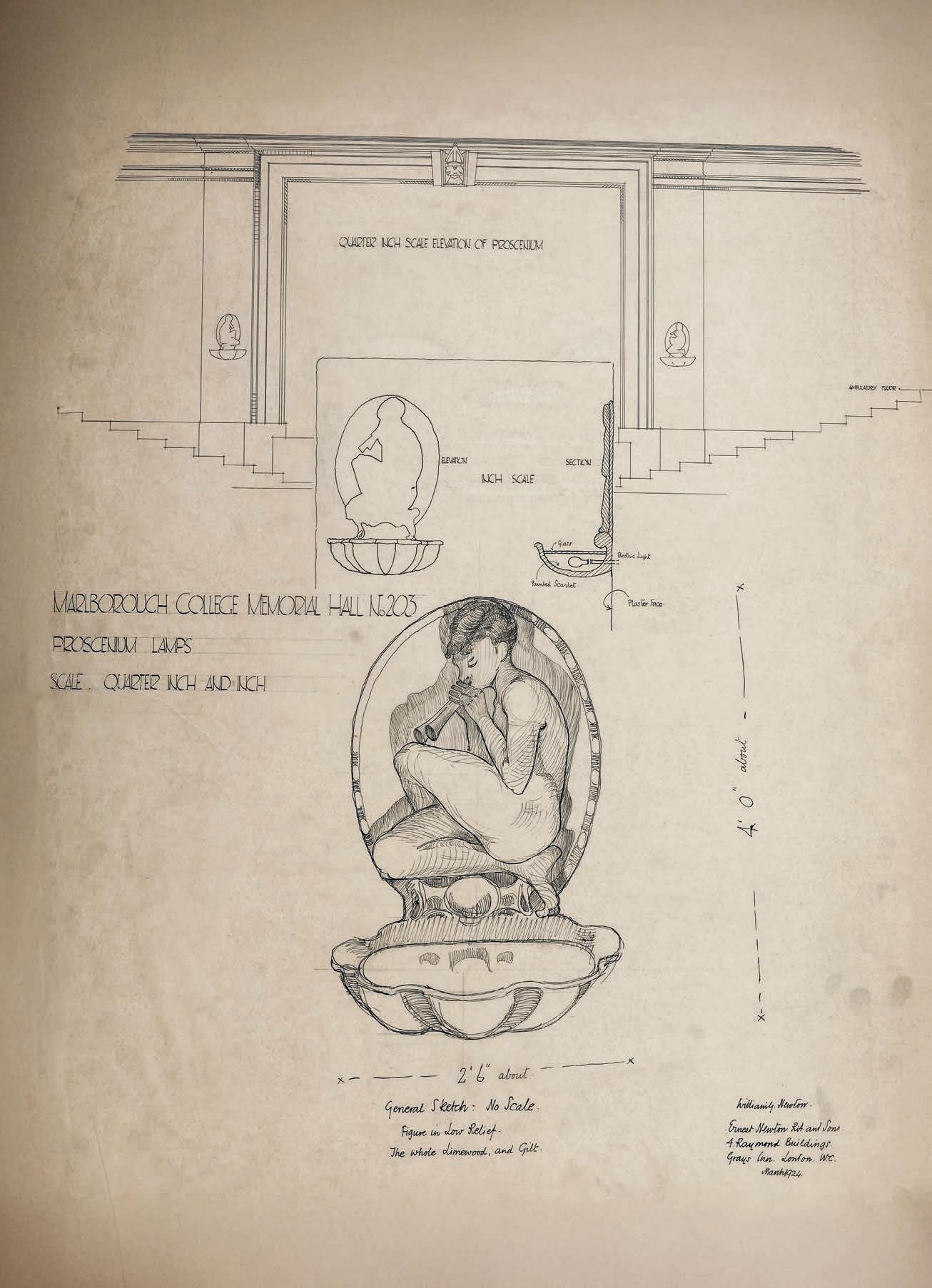

holds the Roll of Honour. This western foyer also contains the names of those who lost their lives in more recent wars. The auditorium, based on the plan of a Roman theatre, contains seating in Indian Silver Greywood (cushioned and upholstered in recent times), which radiates upwards and away from the stage. The audience is embraced by the surrounding semicircular ambulatory, which has the names of the fallen inscribed alphabetically, tinted in grey and red, on its Ancaster stone dado wall. This fine work was undertaken by Laurence Turner, who had once worked for G F Bodley, the Chapel’s architect. His other Marlborough-related work is the gravestone at Kelmscott for William Morris (Aa 1848-51). A cork floor served to silence footsteps and make this area a place for quiet meditation. The stage and the flanking white walls were austere and plain, apart from the contrast provided by the relatively small Art Deco figures made by Phoebe Stabler which adorned the gold uplighters.

Stabler became well known for her ceramic figures, although she also used metalwork, enamel and wood. Her contributions to the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley in 1924 were particularly well received. These two lights, with their stylised depictions of a faun and a boy, added a theatrical touch to the interior, but they seemed at odds with the architecture and were removed when the Hall was remodelled in 2018, as were the stage curtains and arras wall hangings that used to adorn the walls and windows of the ambulatory. The keystone of the original proscenium arch, made by Esmond Burton (C3 1899-01), took the form of a plaster cherub presenting the arms of the College. This was concealed when the stage area was rearranged.

Newton’s original gilded wood pendant lanterns above the auditorium, which provided an almost oriental accent, also helped to relieve the plainness of the interior. In a lavish seventeen-page review in The Architectural Review of June

1925, the architect Darcy Braddell wrote that these lanterns were complemented by a line of standard lamps with small shades, which in his eyes represented the ‘ghost’ of the previous plan’s great columns. It was observed that the seven tall windows admitted the changing light in the auditorium ‘like some great sundial throughout the day’. To the north of the Hall, the evening light of the setting sun would be reflected in the hexagonal blue and gold mosaic floored pool which once existed at the centre of the sunken diamond patterned brick paved plaza, at the point where the axis-lines of the Hall and the Chapel meet. Unfortunately, the pool and its fountain proved to be problematic, and it is now a flower bed surrounded by six large planters, which mark the six-year period between the outbreak of the war and the Treaty of Versailles.

Gavin Stamp has described how during the years between the wars

many architects were influenced by developments in the United States, where Classical architecture had become increasingly sophisticated and refined because many Americans had been trained rigorously at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and given a structured form of education which did not exist in England. This expertise presented an enticing world to the profession in Britain. Leading figures became fascinated by how buildings were created on the other side of the Atlantic, with the understanding shown there regarding the language of the Classicism, steel-frame construction, and the panache of Art Deco. Newton’s experience as editor of The Architectural Review made him aware of what was being undertaken in America and his own work was influenced by this knowledge. The architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner commented that the Memorial Hall comes as near to the American campus style of the same

years as anything this side of the Atlantic. Charles Saumarez Smith (C1 1967-71), former Director of the National Gallery and Chief Executive of the Royal Academy of Art, observed that Newton was able to use the language of Classicism ‘with confidence, not in a doctrinaire way, but as a natural part of a tradition in exactly the way as the architects of equivalent buildings and schools and universities in the United States, as at Harvard, where the Fogg Art Museum, where I later studied, is identical in style and date’.

The Fogg Art Museum building was also completed in 1925, in an elegant Georgian style resembling Newton’s work, by Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch and Abbott. It is an extraordinary coincidence that the earlier lecture hall at the museum of 1892-95, by the well-known architect Richard Morris Hunt, was so similar in plan to Newton’s Marlborough work, although it had a domed roof which

resulted in problems. This building became infamous for its untameable resonance, and the research undertaken on sound in this room by Wallace Clement Sabine in the final years of the nineteenth century provided the foundation for the science of room acoustics. Improvements were made in the lecture hall, but eventually it was demolished in 1973. Sabine’s work influenced Newton’s design at Marlborough, resulting in the relative lowness and flatness of the roof and the flexible acoustic arrangements facilitated by Ambrose Heal’s wall hangings. Complex studies by Sabine of the Hunt building’s sound problems attracted the attention of Jack Diamond, the architect who was responsible for restoring the Memorial Hall in 2018 and improving the way sound carries in the comparable but acoustically less problematic semicircular auditorium. Newton is one of the relatively unsung architectural talents of the years between the wars who could work in numerous styles and adopt new building techniques. Pevsner appreciated the telling contrast between the refined Classicism of Newton’s Hall and his pioneering Modern Movement shuttered concrete and Crittall-windowed science laboratories built less than ten years later, right next door to the Hall. In Bridget Cherry and

John Newman’s book entitled Nikolaus Pevsner. The Best Buildings of England (1986), an anthology of 101 of Pevsner’s most illuminating architectural descriptions, Newton’s buildings at Marlborough are chosen to introduce the section on the 1930s.

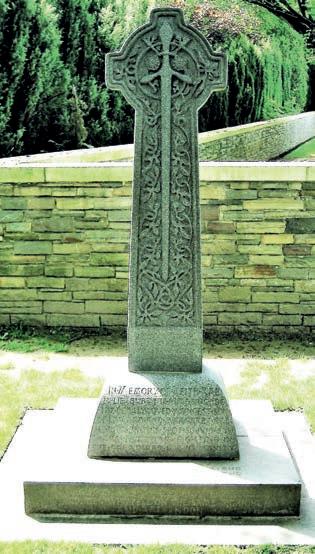

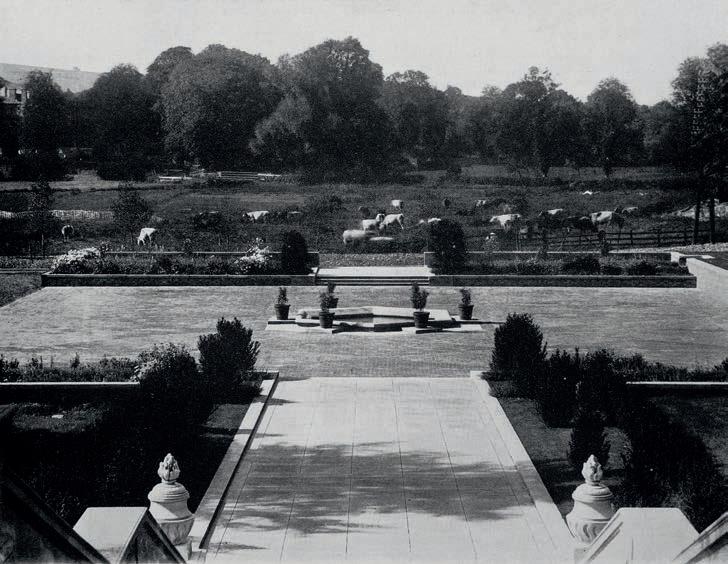

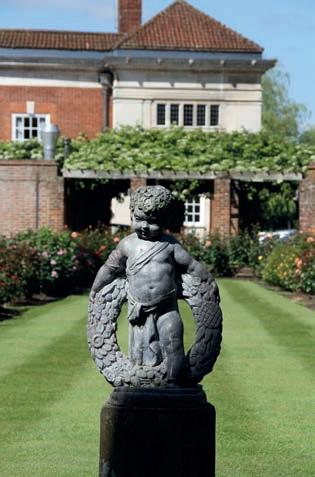

As Norwood had explained in 1925, the memorial to the fallen extends beyond the Hall, embracing the court in front of the building, the Chapel and the garden to the east. A Celtic cross was erected to the north of the Chapel’s east end in memory of the nine members of staff who had lost their lives in the war, and an orchard of cherry trees was planted to the south of the Hall, but with the construction of the science laboratories, only one tree survives.

The design of the Memorial Garden itself was proposed by Newton along with his designs for the Hall, with the former providing a sacred way to the Hall. The work was funded by Herbert Leaf, a member of Common Room between 1877 and 1907, who returned to teach in the last two years of the war when staffing shortages caused such difficulties. He was one of the school’s greatest benefactors, donating over £30,000, providing both the college and the town of Marlborough with electricity, and a substantial sum to help with the construction of the Hall. He wished the garden to be a quiet place where

fallen Old Marlburians could be remembered, but he also wanted it to be a memorial to his wife, Rose, who had died in 1922. She is also remembered by a plaque in the Hall, where the music rehearsal rooms were dedicated to her. There were plans for more gardens to the west of the Hall, where ‘a benefactor (had) presented the water meadow on the far side of the Hall so that one day a winter garden may be carried out’.

Newton designed the Rose Garden, together with a pergola and a gatehouse on the site of what had previously been the home of the

former laundry of 1847 and a stable block. Because of the shortages of building materials, bricks and timber from the buildings on the site were recycled, and Newton wrote that ‘practically the only materials required are tiles for the roof of the Gate House’. The foundations of the western half of the laundry became the foundations and floor of the pergola. Newton’s design shows the 150-foot-long and 15-foot-wide lawn, surrounded by seven pairs of rose beds and a pathway. The whole is surrounded by architecturally shaped yew hedges, with spaces for borders and wooden benches. The small lead figure on its stone base at the east

end is shown in the final plan of May 1924. Newton also devised the planting scheme with the help of fellow Old Marlburian Arthur William Hill (HB 1890-94)), Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. Moving eastwards from the pergola, in paired beds the roses changed from white to cream, lemon, soft orange, yellow blush, apricot and pink, culminating in red roses around the small statue. The borders within the hedges were planted with pinks, lavender and lilies. Wisteria, clematis, jasmine and hydrangea climbed the pergola at the west end of the garden.

One of the approaches into this garden used to be through the gatehouse, which bears a fine inscription in Greek: this elegiac couplet translates to ‘We lie all over the world, but in this garden we walk again as fellow pupils with those who remember the fallen’.

Fred Kottler (C2 2016-20), a recent Senior Prefect, wrote an essay on the ‘reception’ of Classics in the thought and literature of the First World War. He asked an Oxford don who specialises in lyric poetry his opinion about this inscription. He felt it was not by Pindar, as had been thought, or indeed by any Classical Greek writer, but he believed it may have been the work of a beak. It was, in fact, Howard Brentnall (CR 1903-44), who did so much work exploring the site of the royal castle which once occupied the site on and around the great Neolithic Mound to the south of the garden. The inscription was intended to give consolation to those who lost friends and family in the war. The impossibility of recovering bodies from the battlefields is, to a degree, assuaged by the thought that they are still present with the living ‘in this garden’ and with their school friends who had survived; they relive their life at Marlborough once again.

Of particular interest is the word ΣΥΜΦΟΙΤΩΜΕΝ, which means we walk together as pupils. There is a sense of walking side-by-side in learning, conversation and companionship. ΚΕΙΜΕΘΑ, ‘we lie’, evokes precisely the language of fallen heroes in the Iliad; great, noble men who have nobly fallen.

The gatehouse was designed to form a link with the axis of the terrace in front of the Hall and the Rose Garden. It constitutes a form of propylaeum, a building which marks the transition from a secular to a religious area. In addition to being a war memorial, it is now a museum dedicated to the history of the Mound, which might have been erected as a form of memorial 4,000 years ago. It is fitting that this building, with its inscription by Brentnall, now reaches out across many centuries and helps to explain the great and enduring mystery of the garden’s other immediate neighbour.

The change of architectural gears presented by Newton’s Memorial Hall and his Modern Movement

laboratories is matched by the dramatic contrast between the Hall, the Neolithic Mound and Bodley and Garner’s soaring Gothic Chapel, reached by the sweeping flight of steps. With their decorative ornamental lion heads, urns with flaming finials and flanking clipped box hedges, Newton’s steps provide an almost Hollywood-like note to this symbolic link between the secular and the spiritual worlds represented by these buildings. The Hall and its surroundings speak of the importance of duty, sacrifice, service, love and remembrance. They also reflect the great determination and vision of those who had survived the conflict to make sure that the 749 who died were never forgotten. In his 1925 article in The Architectural Review,

Darcy Braddell concluded: ‘Here in fact is a holy precinct. The chapel on its mound, the quiet garden, the empty space of the great brick forecourt, the memorial hall itself, all combine for one purpose. They are monuments to youth not death.’ The complexity of the whole site, with all its orchestrated messages, architectural diversity and history, make it a special place and one which all visitors and members of the Marlborough community should learn from, revere and treasure.

Dr Niall Hamilton (CR 1985- ) former Head of History of Art, former Director of Admissions

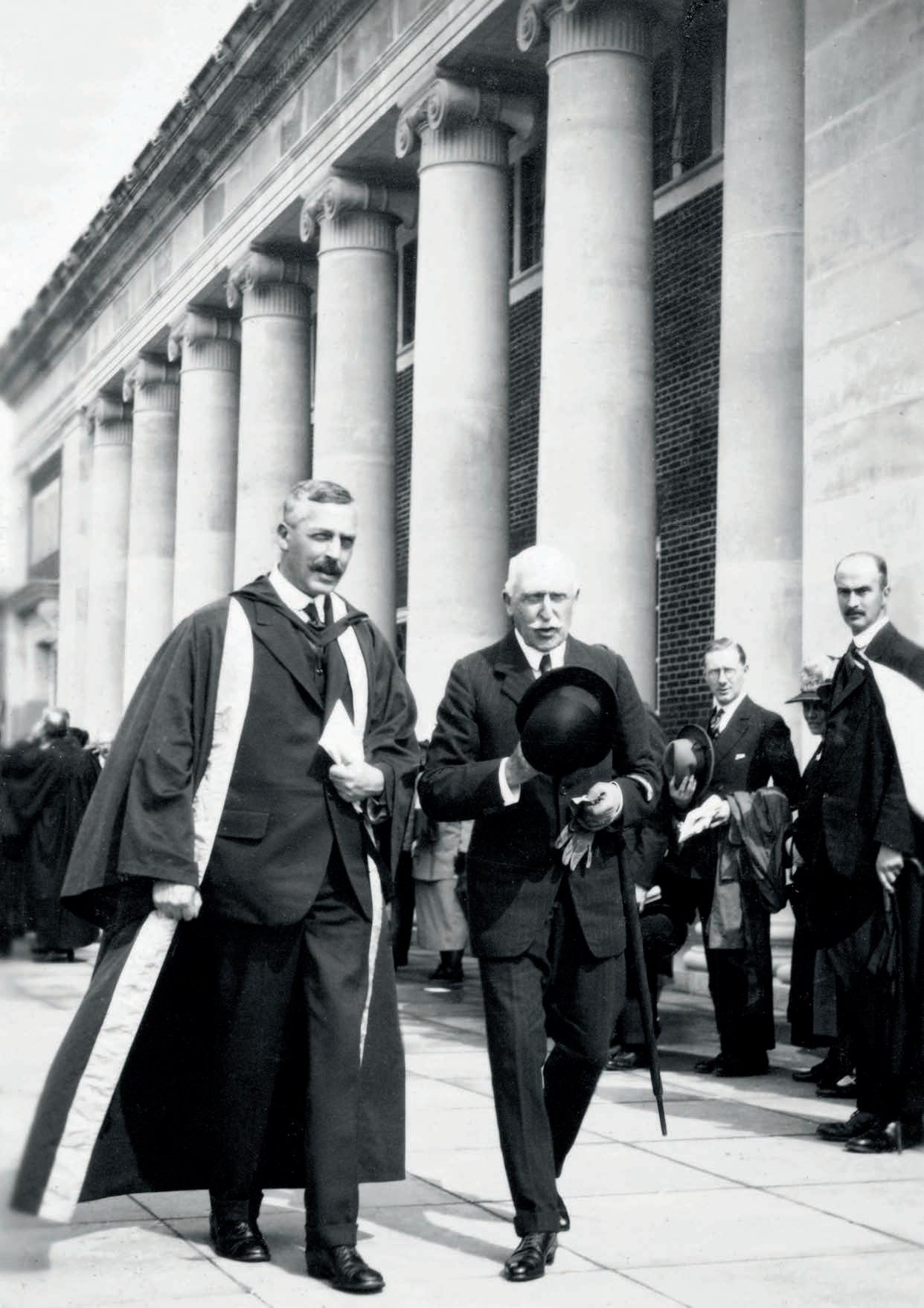

Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, 1st Baronet, GCB, DSO (LI 1877-80) remains the most eminent soldier to have attended Marlborough.

A veteran of several of Victoria’s colonial wars, and an officer during the Boer War, Wilson became Chief of the Imperial General Staff in 1918 – effectively head of the British Army – and in 1919, Field Marshal. He played a major part in the First World War, organizing the British Expeditionary Force in 1914, acting as chief liaison officer with the French Army throughout the war (he was a fluent French-speaker), and heading the Eastern Command from 1917. In addition, Sir Henry served as Commandant of the Staff College, chief military advisor to the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, and was awarded the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath, and Grand Cross of the Légion d’Honneur, among many other decorations. Yet, despite his public and military duties, Sir Henry remained devoted to his old school, and stepped forward to chair the committee that devised and planned the College’s Memorial Hall, presiding over its inaugural meeting at Westminster Central Hall in October 1919. In the following year, Sir Henry assumed the Presidency of the Old Marlburian Club, and once slipped away from an international summit at Chequers to attend Old Marlburian Day.

In the spring of 1922, the College invited Sir Henry to unveil Marlborough’s Roll of Honour. This was set for Old Marlburian Day, Saturday 8th July; however, two weeks before he was due to visit, Sir Henry was assassinated on the doorstep of his home in Belgravia. He had just returned by public transport from unveiling the war memorial at Liverpool Street Station, and was easily identifiable in his field marshal’s uniform to the two IRA gunmen waiting for him on the street outside. Sir Henry, a proud Ulsterman, had been recently elected as a Unionist MP in the government of Northern Ireland, sufficient grounds to make him a target for Republican violence. His assassination was greeted with utter disbelief: this was the most high-profile political assassination since that of Prime Minister Spencer

Perceval in 1812. It also had farreaching consequences: Sir Henry’s murder set in motion events leading to the outbreak of the Irish Civil War six days later, prompting some historians to dub Sir Henry’s killing as ‘Ireland’s Sarajevo’. Sir Henry was granted a state funeral, and thousands lined the rainy streets of London on Monday 1st July to witness the cortege bearing his body on a gun carriage to St Paul’s Cathedral for burial with full military honours.

The sense of loss at Marlborough was particularly acute, and members of the Old Marlburian Club moved quickly to gather funds for a posthumous portrait of their former President with the intention that it should be donated to the College for display in the new Memorial Hall. The portrait was unveiled on Old Marlburian Day, Saturday 27th October 1923 by Sir Henry’s widow, Lady Wilson, in a ceremony held in the Memorial Library’s Reading Room. After speeches from Sir Humphry Rolleston and the Master, Lady Wilson laid a framed set of ribbons from her husband’s medals at the foot of the portrait. It was intended that both portrait and ribbons should be transferred over to the Hall on the building’s completion.

To carry out the commission, the Club approached the rising star of British portrait painting, Oswald Birley (1880-1952), a man with his own distinguished war record as recipient of the Military Cross. In stylistic descent from John Singer Sargent, William Orpen, and John Lavery, Birley became the leading society portrait painter of the inter war years, and, in 1949, like Orpen and Lavery before him, he was knighted for his services. Birley regularly painted official and private portraits of the Royal Family, including George V, Queen Mary, George VI, Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, Elizabeth II, Prince Philip, and the Earl Mountbatten; he also painted Prime Ministers Baldwin, Chamberlain, Attlee, and Churchill

– the latter in several portraits – and figures in the armed forces, Church, and judiciary. Prominent men and women from many quarters, from mayors to marchionesses, company directors to debutantes, sat for Birley in the next decades, even after he lost an eye in a training accident with the Home Guard in 1941. His reputation stood high in the United States, and Birley painted numerous American tycoons and their families, among them Andrew Mellon, J P Morgan and Henry Huntingdon, as well as world leaders, such as Dwight D Eisenhower and Mahatma Gandhi – his portrait of the latter still hangs in the Indian Parliament.

In his commission for the Old Marlburian Club, Birley presents Sir Henry seated side-on to the viewer, perched cross-legged on a stone ledge, and looking down with an expression between the stern and the avuncular. He is in uniform with his field marshal’s insignia on his shoulder, ‘walking out’ stick under

his arm, and cap on the ledge behind him. With tact, Birley casts the right side of the face in shadow, masking the disfigurement Sir Henry suffered from a wound to the eye sustained in Burma in the 1880s. It is testament to Birley’s skill that he achieves such a living presence based only on photographs and his own professional judgement. But the process was not straightforward: Birley trialled his ideas in two full-sized, highly finished oil sketches. One of these is today held at the Defence Academy in Shrivenham, the modern-day counterpart of the Staff College that Sir Henry headed as Commandant. The other was presented by Marlborough College to Belfast Corporation in 1931, and today hangs in the Lord Mayor’s Corridor at Belfast City Hall.

Dr Simon McKeown (CR 2009- ) Head of History of Art (2011- )

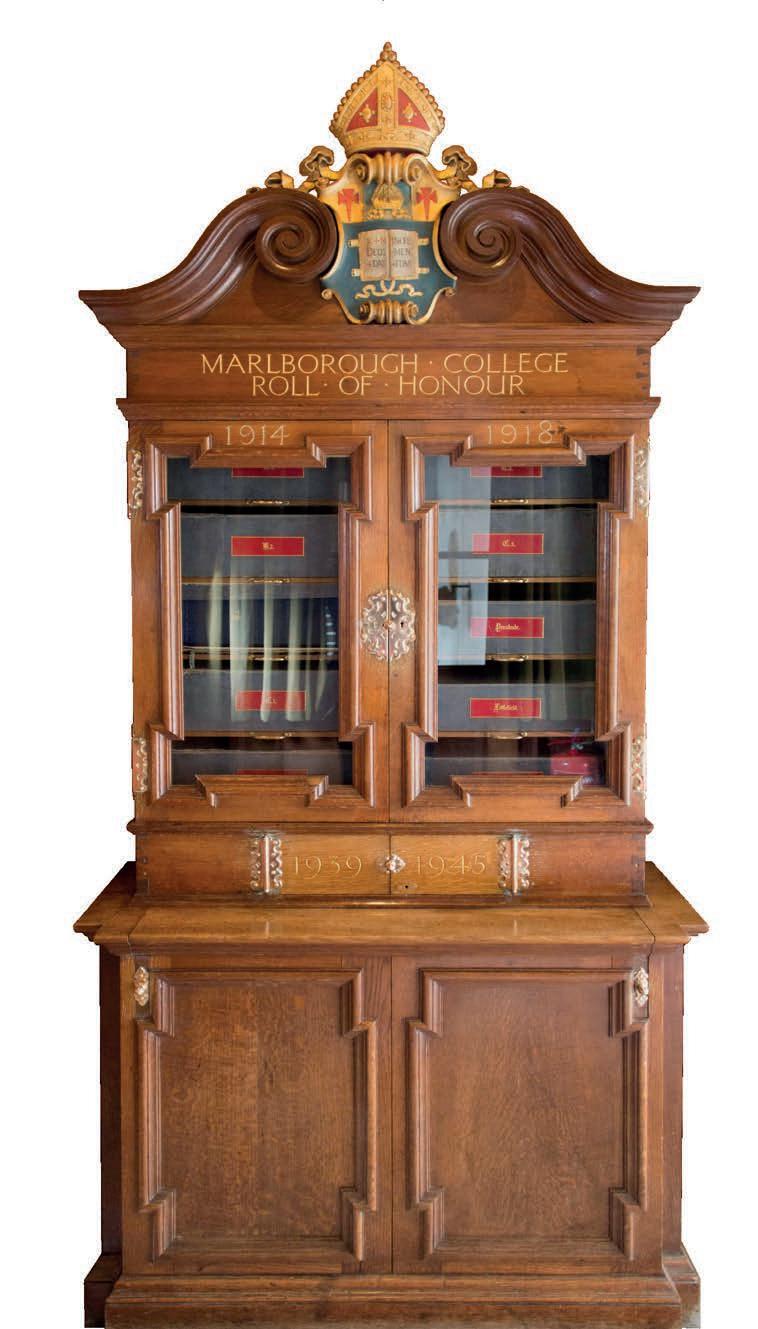

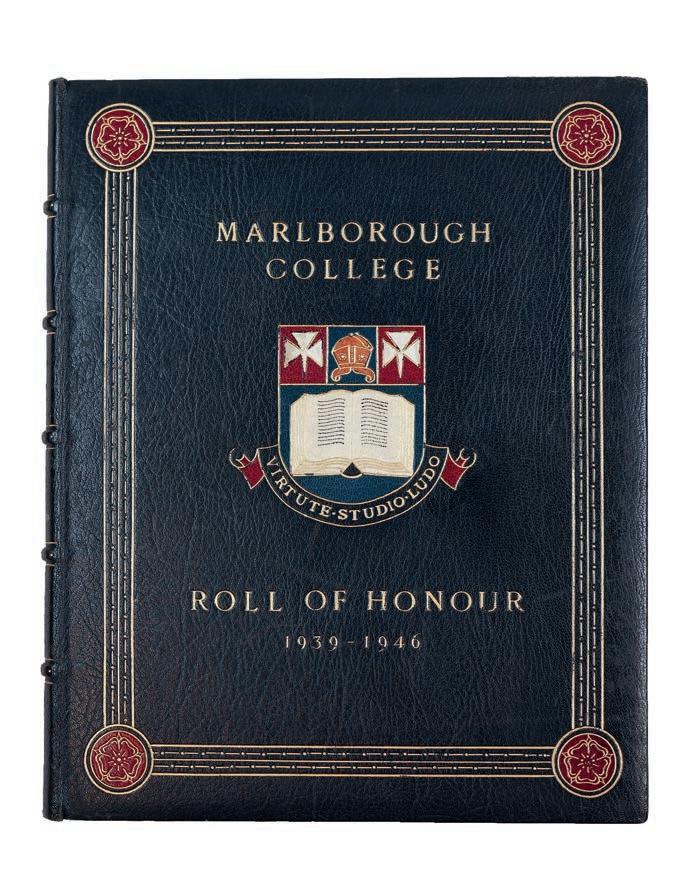

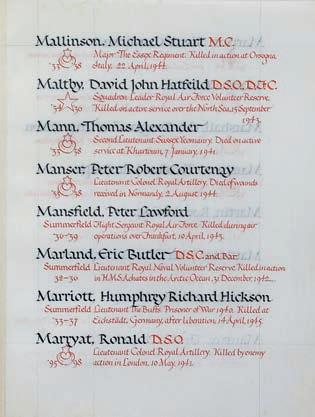

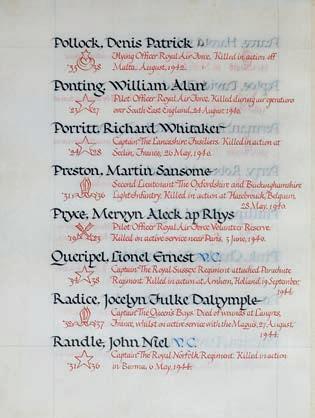

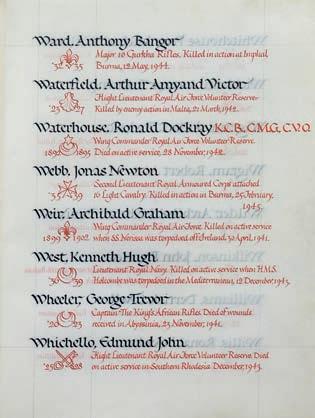

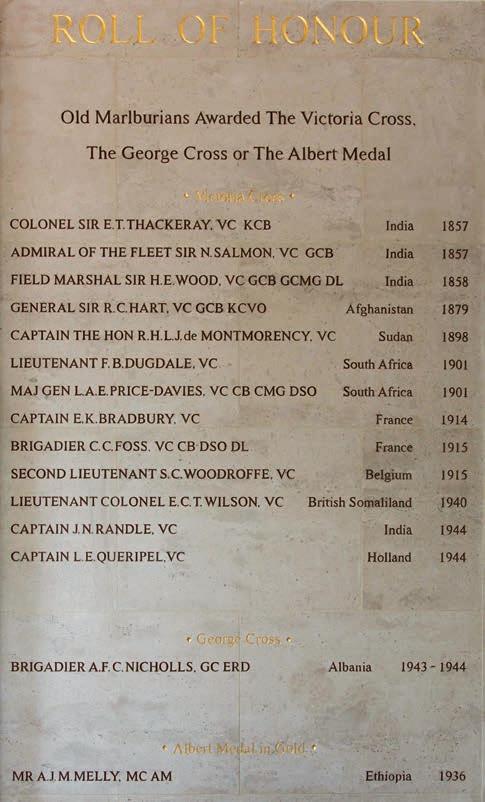

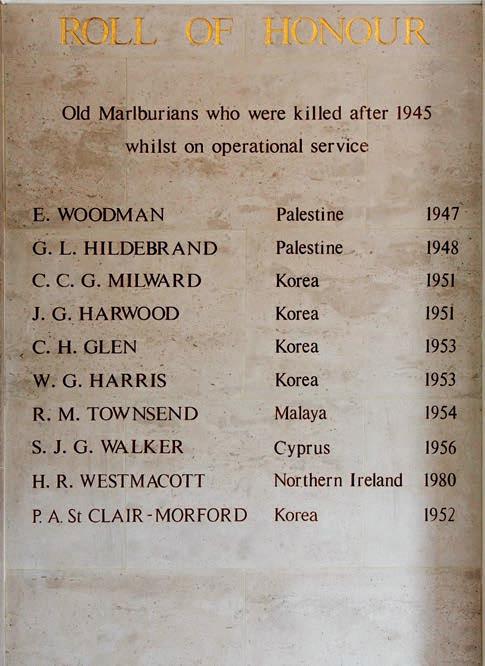

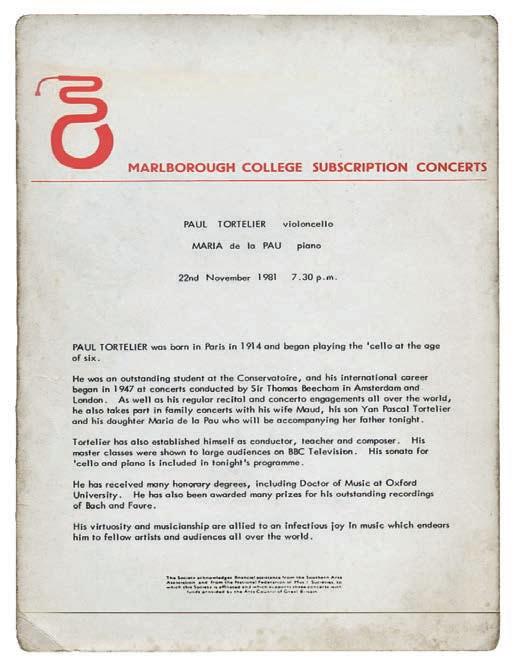

The Marlborough College Roll of Honour holds a uniquely important place within the Memorial Hall. It records the names and photographs of Old Marlburians and Assistant Masters who perished in the First and Second World Wars, and so great was the College’s loss that the roll runs to eleven large folio volumes: ten for the Great War, and one for the 1939-1945 conflict. Nine of the volumes are organised by College houses – C1, C2, C3, B1, B2, B3, Cotton, Littlefield and Preshute – with another for Summerfield, the Junior Houses and Assistant Masters.

A further volume listing names from the Second World War was added to the Roll in 1951. Each of the volumes is enclosed within a buckram clam-case and bound in blindstamped blue morocco with the house name and College arms impressed in gold on the upper board. The inner boards are lined with ivory moire, or watered silk, framed by rich gold tooling. Inside the volume, the Roll presents the names of the dead with a short entry detailing their service and circumstances of death. In most cases, the names are accompanied by a photograph of the deceased, usually in military uniform. The names are ordered by date of enrolment into the College, and all texts are calligraphed in an elegant copperplate script.

The motive force behind this great enterprise was Freke D Williams (C3 1871-73), partner in the legal firm of Fladgate and Coy, the College’s London solicitors. In the foreword to each volume, Williams states that he was moved to perpetuate the memory of ‘Marlburians who served in the Great War by sea, by land, and in the air, and, with the single object of helping the British Empire in its hour of need, gave their lives for their country’. He relates how he had

begun to collate his information in the autumn of 1914 by approaching ‘parents, widows, or other near relations’ for details of their loved ones’ war service. Doubtless Williams’s research was facilitated by reference to the ‘Roll of Honour’ that appeared in each issue of The Marlburian magazine throughout the war years, and which was subsequently published under separate cover in 1919 and 1920. He would also have benefited from the work of George Bell Routledge (C2 1877-80), editor of the Marlborough College Register, who appealed for information concerning military service for inclusion in the Register ’s seventh edition of 1920. Disappointingly, Williams does not record the name of the calligrapher he engaged to indite the entries with unerring skill; nor does he document the craftsmen responsible for collating and binding the volumes themselves.

The ten volumes of the Roll are kept within a handsome cabinet that stands in the western lobby of the Memorial Hall. There, behind glazed double doors fitted with high-lustre brass escutcheons, the individual volumes rest in their clam-cases on open-fronted drawers, while the

eleventh volume, that for the 19391945 names, lies within an enclosed recess below. The cabinet itself is in the Baroque style and is surmounted by a broken pediment terminating in elaborate scroll volutes. Within the pediment nestles the College arms tinctured and crested by the bishop’s mitre accoutred with particularly animated ribbons, or lappets. We know that the cabinet was designed by William Newton (C1 1899-04), but it remains unclear who executed his plans. The most probable candidate is Laurence Turner (C1 1877-81), carver of the names in stone along the rear wall of the Hall. Turner was also a proficient worker in wood, and we know that he provided the cabinet with its carved crest and incised inscriptions; it was Turner, too, who took charge of arranging the display of the cabinet when it was delivered to the College in 1922. The cabinet was subsequently altered in 1950-1951 with repairs carried out on water damage to the lower case, the fitting of new ironmongery, and a partial rebuild of the waist to accommodate the 1939-1945 Roll. The renovation was carried out by the London architect and furniture designer, Roderick Eustace Enthoven (1900-1985).

The Roll of Honour was completed almost three years before the opening of the Memorial Hall, and the College authorities pondered over where it should be housed until the Hall was ready to receive it.

The Bursar, Major John Archibald Davenport, elected for the Bradleian, a choice that stirred Turner to protest that the Roll would ‘look very much lost there’, and that the cabinet’s style would jar with the room’s ‘chimneypieces [which are] coarse in detail and rather gross in character.’ Turner’s arguments did not prevail, and it was in the Bradleian that the College Roll of Honour was unveiled in a ceremony staged on Old Marlburian Day, Saturday 8th July 1922 – also the occasion when the newly completed Rose Garden was officially opened. Alas, it turned

out to be a more sombre occasion than anticipated. For one thing, the weather played havoc with the programme, rendering the formal opening of the Garden a total washout. Instead of the Bishop of London, Arthur Winnington-Ingram (B1 1871-76), dedicating the Garden from a platform ‘gaily bedecked with flags’, he was forced to keep within the shelter of the Chapel while the rain lashed the windows. But also overshadowing the mood of the day was a keen awareness that a dignitary was absent from the programme. Sir Henry Wilson (LI 1877-80) had been asked to dedicate both the Garden and Roll of Honour: now, just a week after his funeral in London, his place was taken by Paul, 3rd Baron Methuen, a member of Council.

Understandably, Lord Methuen’s speech, delivered inside the Bradleian, was much preoccupied with the loss of Sir Henry, who ‘like Wolfe, like Nelson, like Gordon, and like Kitchener, died in the uniform to which he did so much honour.’ But Lord Methuen also acknowledged the dead listed in the Roll before him, assigning their courage to the values they had learned at Marlborough, construing that ‘public schools produced that chivalry which we had in the war, and which our enemy had not. When we went to our public schools we learnt to obey, and when we left our public schools we knew how to command.’ With that, Lord Methuen concluded ‘I now unveil this memorial to the seven hundred men who have carried the honour of Marlborough throughout this war,

and God be with them!’ After a word of thanks, the Master, Dr Norwood (CR 1916-25), invited Old Marlburian, Sir Edward Thackeray (B1 1845-50), cousin of the novelist, to give a brief salutation. Sir Edward, recipient of the Victoria Cross for valour under ‘heavy musketry’ during the 1857 Indian Mutiny, had been witness to a truly different age of warfare.

The cabinet containing the Roll of Honour was subsequently moved from the Bradleian to the Memorial Hall ahead of the grand opening by the Duke of Connaught in May 1925. It was for many years placed in the Hall’s ambulatory amid the names of the 749, before taking up its current place in the western lobby in 1951. In 2014, the College published online a digitised edition of the Roll of Honour to observe the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War. Thus, through modern means, the College seeks to stand by its promise to ‘Remember’ the names of those inscribed within the Roll of Honour. They can be viewed at: https://archive.marlboroughcollege.org.

Dr Simon McKeown (CR 2009- )

Head of History of Art (2011- )

The College is part of an extraordinary tradition of writers, including celebrated war poets who are remembered as much for the skill of their poetry as for their shocking depiction of the conflict, which was at odds with what patriotic supporters of the First World War believed it should be.

There are three names carved into the wall of the ambulatory of the Memorial Hall which offer a poignant insight into the poetry of the First World War and the profoundly significant contribution of Old Marlburian writers on the literature that the conflict inspired: C H Sorley (C1 1908-13), A C V De Candole (C3 1911-16) and H W Sassoon (CO 1902-04).

Few deaths illustrate the loss of creative and literary potential as demonstrably as that of Charles Hamilton Sorley, shot dead by a sniper at the Battle of Loos in October 1915. Fellow war poet Robert Graves, who was also involved in the battle, emphasised Sorley’s talent, and the significance of the loss, in his autobiography, Goodbye to All That : ‘it had been another dud show chiefly notorious for the death of Charles Sorley, a twenty-year-old captain in the Suffolks, one of the three poets of importance killed during the war’ (the other two were Isaac Rosenberg and Wilfred Owen).

Described posthumously by the Master of Marlborough, with whom he corresponded from the trenches, as with a ‘rich, glowing personality, his vivid imagination and his power of interpreting it in words, his originality, his intense human sympathy, his high ideals and his lovableness’, Sorley was, ironically, a great admirer of Germany and was on holiday in the country, exploring German culture and literature, when war broke out. He was a reluctant but popular and well-regarded soldier who wrote affectionately about his alma mater from the front, particularly in correspondence with his former teacher, the legendary John Bain (CR 1879-19). There is a sense of nostalgic yearning for his old school and the peaceful days of academia when he writes in July 1915 ‘I have not brought my Odyssey with me here across the sea’, which finishes as below:

This from the battered trenches—rough, Jingling and tedious enough.

And so I sign myself to you:

One, who some crooked pathways knew Round Bedwyn: who could scarcely leave

The Downs on a December eve: Was at his happiest in shorts,

And got—not many good reports!

Small skill of rhyming in his hand—

But you’ll forgive—you’ll understand.

We can forgive the youthful sentimentality in Sorley’s early poetry when it blossoms into the power and poignancy of his more mature work; inspired by the frustrations and suffering he witnessed in the trenches and on the battlefields. His work is never as nihilistic as that of some of his contemporaries, but he explores the contradictions of the war with a deft lyricism, as seen in the sonnet below.

Such, such is Death: no triumph: no defeat: Only an empty pail, a slate rubbed clean, A merciful putting away of what has been.

And this we know: Death is not Life, effete, Life crushed, the broken pail. We who have seen So marvellous things know well the end not yet.

Victor and vanquished are a-one in death: Coward and brave: friend, foe. Ghosts do not say, “Come, what was your record when you drew breath?”

But a big blot has hid each yesterday So poor, so manifestly incomplete.

And your bright Promise, withered long and sped, Is touched, stirs, rises, opens and grows sweet And blossoms and is you, when you are dead.

His brilliant and shocking poem When You See Millions of the Mouthless Dead , found in his kitbag when they recovered his body from the bleak battlefield, anticipates the modernist response to the horrors and chaos of the war with its unremembered ‘spook’ – anticipating Eliot’s ghostly figures marching across London Bridge in the opening of The Waste Land .

When you see millions of the mouthless dead

Across your dreams in pale battalions go,

Say not soft things as other men have said, That you’ll remember. For you need not so.

Give them not praise. For, deaf, how should they know It is not curses heaped on each gashed head?

Nor tears. Their blind eyes see not your tears flow. Nor honour. It is easy to be dead.

Say only this, “They are dead.” Then add thereto, “Yet many a better one has died before.”

Then, scanning all the o’ercrowded mass, should you

Perceive one face that you loved heretofore, It is a spook. None wears the face you knew.

Great death has made all his for evermore.

Sorley, along with other poets of the war, ensured that the young dead did not remain ‘mouthless’. It is the portrayal of the suffering and futility of the Great War from the poets such as Sorley that is foremost in the popular consciousness over one hundred years later.

The least well-known of Marlborough’s war poets is Alec de Candole, a prize-winning scholar, he intended to study Theology at Cambridge before taking Holy Orders, but with war raging in Europe, he enlisted with the 4th Wiltshire Regiment in 1916. De Candole was only twenty-one when he met his death in France during a bombing raid on 3rd September 1918, a few weeks short of the Armistice.

His poems were first brought to public attention through small publications sponsored by his devoted parents in his honour. De Candole also wrote a small book entitled The Faith of a Subaltern, which was published posthumously by the Cambridge University Press.

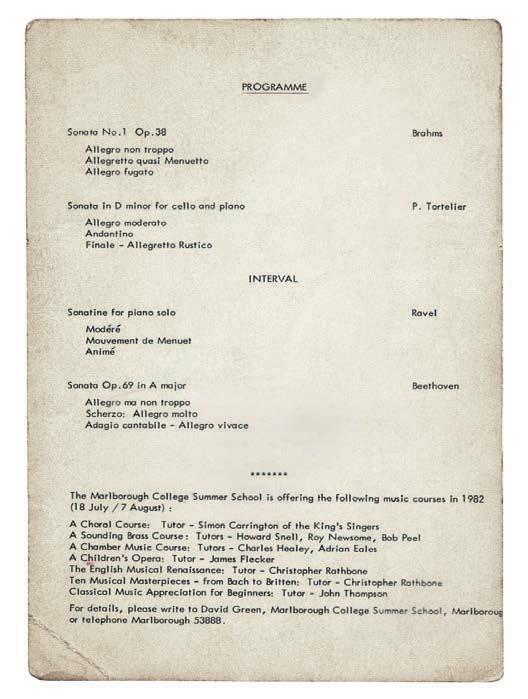

In 2020, a Shell pupil – by happy coincidence also a C3 boy – working on a research task in the Memorial Library unearthed an unpublished manuscript poem by de Candole tucked into the personal copy of his poems that once belonged to his mother. It is written on tissue-thin paper, seemingly transcribed in his mother’s hand and dated 1916. De Candole’s grieving parents attended the opening of the Memorial Hall in 1925 and continued to publish his works long after his death.

The original manuscript of the poem is shown on page 46.

The original unpublished manuscript of a poem

The name Sassoon echoes across the decades in terms of Marlborough College and the First World War. It is not Siegfried (CO 1902-04) who is commemorated in the Memorial Hall, he survived the war, but his brother Hamo. It is through Hamo that we can see the distinct sides of the famous poet, his younger brother. At the outbreak of the war, Siegfried enthusiastically joined the Sussex Yeomanry (and later the Royal Welch Fusiliers) and followed his beloved brother to the front. However, Hamo was killed during the action at Gallipoli shortly before Siegfried arrived in France. Siegfried’s early war poetry reflects a stoic and patriotic response to Hamo’s death, but this respectful tone towards the sacrifices of the war would not last:

Give me your hand, my brother, search my face: Look in these eyes lest I should think of shame;

For we have made an end of all things base.

Siegfried Sassoon was an extraordinarily brave soldier who was loved by his men; he won the Military Cross for bringing back a wounded comrade under heavy fire and was even recommended for the Victoria Cross for capturing a German trench single-handed. He was dubbed ‘Mad Jack’ for his reckless disregard for his own safety, which may well have been a response to his brother’s death.

However, as with Sorley, and despite being such a well-regarded and decorated soldier, Sassoon went on to write vivid and terrifying portrayals of life in the trenches. Sassoon’s war diaries – written from the front lines – included his detailed observation of the first days of the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

July 1st 1916:

7.30: Last night was cloudless & starry & still – the bombardment went on steadily. We had breakfast at 6 – the morning is brilliantly fine – after a mist early. Since 6.30 there has been hell let loose. The air vibrates with the incessant din – the whole earth shakes & rocks & throbs – It is one continuous roar – machine-guns tap & rattle – bullets whistling over head – small fry quite outdone by the gangs of hooligan-shells that dash over to rend the German lines with their demolition parties.

7.45: Our men advancing steadily to the 1st line. A haze of smoke drifting across the landscape – brilliant sunshine. Some Yorkshires on our left watching the show and cheering as if at a football match. The noise as bad as ever.

9.30: Came back to dug-out and had a shave. Just been out to have another look. The 21st Division are still going across the open on the left, apparently with no casualties. The sun flashes on bayonets and the tiny figures advance steadily and disappear behind the mounds of trench debris.

9.50: The smoke drifts across our front on a south-east wind, just a breeze. The birds seem bewildered: I saw a lark start to go up, and flutter along as if he thought better of it. Others were fluttering above the trench with querulous cries, weak on the wing.

10.05: I am looking at a sunlit picture of Hell. And still the haze shakes the yellow charlock, and the poppies glow below Crawley ridge where a few Hun shells have fallen lately. Manchesters are sending forward a few scouts. A bayonet glitters.

From about 1916, Sassoon’s opinions about the war changed and he began to see it as pointless and futile. This is reflected in his satirical poem The General, which was probably written with his commander – MajorGeneral Sir Reginald Pinney, whom Sassoon did not approve of – in mind.

“Good-morning, good-morning!” the General said When we met him last week on our way to the line. Now the soldiers he smiled at are most of ‘em dead, And we’re cursing his staff for incompetent swine.

“He’s a cheery old card,” grunted Harry to Jack As they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack. But he did for them both by his plan of attack.

At a more serious level, when home on leave, Sassoon wrote a protest pamphlet that came to wide public attention when it was read out in Parliament and published in The Times on 31st July 1917, the same day that the British began the Battle of Passchendaele.

Finished with the War: A Soldier’s Declaration

I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority, because I believe that the War is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it. I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers. I believe that this War, on which I entered as a war of defence and liberation, has now become a war of aggression and conquest. I believe that the purpose for which I and my fellow soldiers entered upon this war should have been so clearly stated as to have made it impossible to change them, and that, had this been done, the objects which actuated us would now be attainable by negotiation.

I have seen and endured the sufferings of the troops, and I can no longer be a party to prolong these sufferings for ends which I believe to be evil and unjust.

I am not protesting against the conduct of the war, but against the political errors and insincerities for which the fighting men are being sacrificed. On behalf of those who are suffering now I make this protest against the deception which is being practised on them;

https://net.lib.byu.edu/english/wwi/influence/ssprotest.html

This protest caused significant public embarrassment for the government and supporters of the war, which at that time was the vast majority. Not supporting the war was considered unpatriotic at best, treacherous at worst. Sassoon’s background and war record made him a very influential figure and troublesome. In order to hide him away from publicity, he was invalided out of the army, supposedly as a victim of shell shock. He was hidden away and forced to be treated at Craiglockhart Hospital in Edinburgh where he met another poet, the young Wilfred Owen, on whom he would have a profound impact in terms of attitudes to both the war and poetry.

Sassoon wrote many powerful poems illustrating the suffering and futility of the war. This is epitomised in Attack, a staple of British classrooms, which was first published in his 1918 collection Counter-Attack and Other Poems. The poem offers a bleak and unflinching look at the horrors of combat, making no attempt to mythologise its subject or create a sense of heroism. The final image of the struggling figure of hope floundering in the mud of the trenches descends into a desperate, unpoetic plea for a cessation of the destruction and chaos.

At dawn the ridge emerges massed and dun

In the wild purple of the glow’ring sun, Smouldering through spouts of drifting smoke that shroud

The menacing scarred slope; and, one by one, Tanks creep and topple forward to the wire. The barrage roars and lifts. Then, clumsily bowed With bombs and guns and shovels and battle-gear, Men jostle and climb to meet the bristling fire.

Lines of grey, muttering faces, masked with fear, They leave their trenches, going over the top, While time ticks blank and busy on their wrists, And hope, with furtive eyes and grappling fists, Flounders in mud. O Jesus, make it stop!

Sassoon returned to the front lines, even though he had stopped believing in the validity and point of the war. He was torn by dilemma and guilt, but he felt he had to return to his brothers-in-arms, even though he had publicly spoken out against a war that he believed was futile. He was eventually invalided out of the war –as he states in his war diary, he ‘got a sniper’s bullet through the shoulder’.

Along with other war poets, Sassoon’s poems were not widely known in the immediate aftermath of the war and there was a lack of public appetite for the true horrors of the trenches. However, from the 1920s onwards the war poets have been regarded as the authentic voice of the fighting solider of the First World War. Sassoon went on to enjoy success as a writer of prose works, and lived in rural Wiltshire, much engaged with hunting and other country pursuits. He survived, but many others, including Sorley, de Candole and Wilfred Owen, did not and died as young men with their potential unfulfilled.