T H E

M A R I N

L A W Y E R

T H E

M A R I N

L A W Y E R

Lead Editor: Robyn Christo

Guest Editors: Nestor Schnasse & Scott Buell

Creative Director: Aariel Nigam

2025 Officers

President: Kristine Fowler Cirby

President-Elect: Thomas M. McInerney

Treasurer: Neusha N Ghaedi

Secretary: Robyn B Christo

Past President: Scott Buell

5 Year Past President: Matt White

Board of Directors

2025

Elisha J Yang

Lucie C Hollingsworth

Morgan H Daly

Nestor Schnasse

Shanti Eagle

2026

Christine O’Hanlon

Ingrid L Carbone

Marisa R. Chaves

Marrianne S. Taleghani

Roni D. Pomerantz

2027

Adrea S Tencer

Emily B Harrington

Paul Burglin

Sarah B. Anker

R. Wesley Pratt

Executive Director

Julie Cervetto

Membership & Events Manager

Denise Belli

Client Relations Chair

David M Zeff

The Marin Lawyer is published by The Marin County Bar Association 101 Lucas Valley Road, Suite 326 San Rafael, CA 94903 (415) 499-1314 info@marinbar org marinbar org

5 | Editor’s Introduction

ROBYN

B. CHRISTO, ESQ.

8 | 2025 President’s Message: The Rule of Law: The Quiet Framework that Holds us All Together KRISTINE FOWLER CIRBY

10 | The Rule of Law as a Central “Pillar” of Judicial Conduct

HON JAMES M. SCHURZ

18 | What We Choose When We Choose Each Other

ELIZABETH BOHANNON

21 | The Lawyer as Revolutionary: Protecting the Independent Judiciary

DAVID F. FEINGOLD

25 | A Call to Action to Champion the Rule of Law and to Support an Independent Judiciary

LEN RIFKIND

30 | Is This Normal? MOLLY COHEN PHIPPS

33 | Why AI Training Should Fall Outside Copyright’s Domain: A Legal Analysis

MARC HOAG

55 | Three Poems by Karen Poppy KAREN POPPY

59 | Non-Profit Spotlight: Canal Alliance: Supporting Latinos and Immigrants in Marin County Since 1982 NESTOR SCHNASSE

Robyn B. Christo, Esq.

We chose "The Rule of Law" as our theme for this issue because it feels urgent and personal right now. The pieces in this issue reflect a legal profession grappling with challenges that feel different from anything we've faced before. Our contributors aren't just writing about abstract constitutional principles—they're wrestling with whether those principles will survive intact

Judge James Schurz opens with a thoughtful piece on judicial conduct that draws from California's leading judicial ethics authority. His analysis of what Supreme Court justices have been saying about judicial independence lately is both scholarly and sobering. When sitting justices feel compelled to defend the legitimacy of their own branch of government, we're clearly in uncharted territory

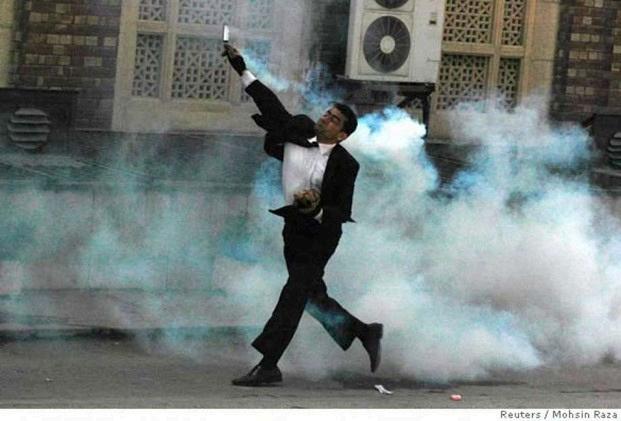

David Feingold's call for lawyers to think of themselves as revolutionaries might sound dramatic, but his comparison to Pakistani lawyers literally fighting in the streets to defend judicial independence makes his point. His question is uncomfortable but necessary: What are we willing to do to protect what we say we value?

Len Rifkind takes a more systematic approach, cataloging recent executive actions and their constitutional implications. His piece reads like a legal brief prepared for the historical record meticulous, comprehensive, and deeply concerning The action steps he outlines aren't theoretical; they're practical suggestions for lawyers who want to do something beyond just talking about these issues.

Elizabeth Bohannon's piece about her grandparents' escape from Soviet-occupied Hungary hits differently when you consider what's happening today Her family's story choosing to flee authoritarianism even when it meant leaving everything behind serves as both historical context and contemporary warning. Sometimes the most powerful legal arguments come from lived experience.

And then there s Molly Cohen Phipps, the law student who cuts through all our learned discourse with a simple question: "Is this normal?" Her perspective is valuable because she sees clearly what those of us deeper in practice might overlook or dismiss as "just politics."

This issue also includes Marc Hoag's detailed analysis of AI copyright law a reminder that the rule of law must evolve to handle new techno-

logical challenges without losing its core principles. His argument that AI training should fall entirely outside copyright's domain shows how legal thinking needs to adapt while staying grounded in established doctrine.

Nestor Schnasse's profile of Canal Alliance shows how these constitutional concerns affect our local community. His documentation of how current immigration enforcement has created a climate of fear in Marin's Latino community reminds us that constitutional principles only matter if they actually protect real people facing real problems.

Even Karen Poppy's poetry speaks to our theme. Her poem "El Salvador-CECOT" uses the metaphor of safety coffins to suggest we need to "pull the cord" and "ring the bell" when we see injustice. As we head into Pride Month and approach Juneteenth, her words about survival and belonging under the law feel especially relevant.

The legislative threat that prompted several of these pieces Section 70302 of the "One Big Beautiful Bill Act" would prohibit federal courts from enforcing contempt citations without posted security. It sounds technical, but it's designed to gut judicial authority in civil rights cases in which judges typically waive the bond equirement. The practical effect would be to

render court orders meaningless government officials could simply ignore injunctions knowing they face no real enforcement mechanism. That's not reform; that's dismantling.

What strikes me about all these contributions is that none of our writers have given up. They're not just documenting problems they're fighting for solutions. They understand that the rule of law isn't self-executing. It requires constant maintenance by people who care enough to do the work.

President Kristine Fowler Cirby puts it well in her message: "Now is the time to speak up and step up. The Rule of Law depends on us."

These pieces suggest she's right. The question is whether we're listening.

The Editor

Robyn B Christo, Esq is a founding partner of Epstein Holtzapple Christo LLP, a womenowned boutique probate firm based in Marin County EHC represents clients in complex administrations and high stakes litigation including high stakes disputes over trusts, estates, powers of attorney, guardianships,

d elder financial abuse matters. Robyn is a fierce advocate for access to justice and civility in the practice of law She currently serves as Secretary of the Marin County Bar Association Board of Directors

Kristine Fowler Cirby

As attorneys, we invoke the Rule of Law often sometimes as a rallying cry, other times as a shield.

But what does it really mean?

In its most basic form, the Rule of Law means that no one is above the law and everyone is protected by it. It means decisions are based on facts and legal principles, not politics, status, or whim. It’s the quiet, often invisible framework that supports our democracy, our rights, and our profession.

In a time when public trust in institutions is fraying and polarization is growing, our responsibility to uphold these principles becomes even more urgent. Reaffirming our commitment to the Rule of Law is not just symbolic it’s essential.

As attorneys in California, we have all taken an oath “to support the Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of the State of California, and to faithfully discharge the duties of an attorney and counselor at law to the best of our knowledge and ability.” This oath is a solemn reminder of the role we play in upholding justice and the Rule of Law.

We have a duty, as members of the legal profession, to step forward when foundational principles are threatened. The Constitution. Due process. Separation of powers. These are not partisan concepts. They are the bedrock of a just society and they rely on us for their continued strength.

But our commitment doesn’t end in the courtroom. It shows up in the way we mentor new attorneys, advocate for those with no voice, engage in civil discourse, and lead in our communities. Every action we take to support fairness, access, and integrity in the legal system helps ensure this framework survives for future generations.

This issue of The Marin Lawyer features reflections and stories from members of our local bar who are doing just that living these values in real time, in real ways. I encourage you to read their words, take a moment to reflect, and recognize the role each of us plays.

As we head into summer, let this be a time not just to rest but to recommit. To the law. To one another. And to the promise that justice must be accessible, impartial, and resilient.

Now is the time to speak up and step up. The Rule of Law depends on us.

With gratitude and resolve,

Kristine Fowler Cirby President, Marin County Bar Association

Kristine Fowler Cirby s a family law attorney with over 30 years of experience In 2019, she established her family law firm in Larkspur, handling all types of family law cases, including divorce, custody, domestic violence, and support matters. Throughout her career, Kris has advocated for victims of domestic

violence, immigrants, and low-income families Kris was formerly the Executive Director at Family & Children’s Law Center She currently serves on the board of Community Violence Solutions. Kris previously held leadership roles with the Marin County Law Library and Marin Women's Commission In 2021, Kris received the Marin Trial Lawyers Association’s President’s Award

Hon. James M. Schurz, Superior Court of California, County of Marin

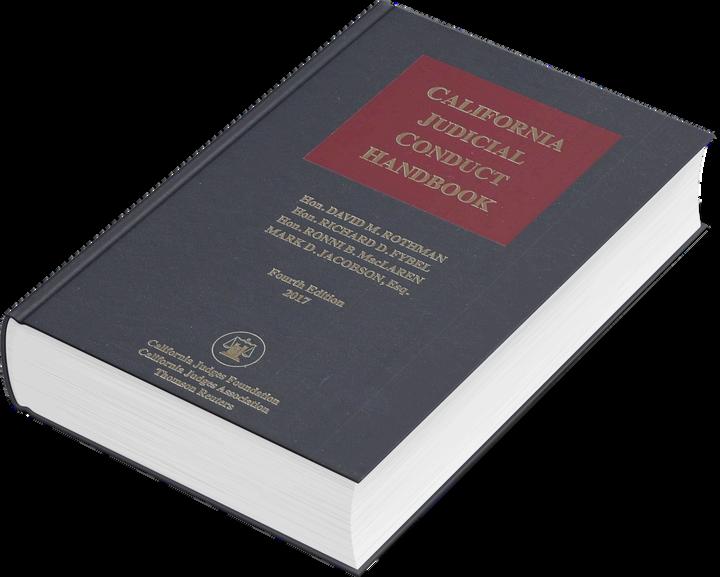

The first package to arrive in the mail following my appointment to the Marin Superior Court was Judge David Rothman’s treatise, The California Judicial Conduct Handbook. Weighing in at 971 pages, it is a formidable piece of scholarship. It landed on our doorstep two weeks before the judicial robe from academicapparel.com arrived and posed a far more significant challenge in terms of preparing for my new job.

Rothman’s book is in every judge’s chambers throughout the state. It has been the definitive source for ethics guidance for California judges since it appeared in 1990. The stated purpose of the book is to assist judges in the performance of their duties. And “most important, [provide] a basis for an understanding of the essence of what being a judge is about.” (Rothman at 4.) This is a tall order

Central to Rothman’s exercise is the application of the rule of law as a central “pillar” to the integrity of judicial decision making. This foundational principle is in the news a lot lately, with at least three Supreme Court justices weighing in on the importance of judicial independence and its relationship to the rule of law. Reflecting on the comments of our nation’s highest judges, it is helpful to consider their observations both what is said and what is left unspoken within the context of California’s leading judicial ethicist.

Rothman sees adherence to the rule of law through an ethical lens. Deviation from it poses a distinct danger that erodes public confidence in judicial institutions and undermines our participatory democracy. “Judges are not in courtrooms to make up the rules as they go along ” (Rothman at 23.) Rather, judges are to be guardians of the formal and procedural elements that comprise the rule of law. This is necessary both for the parties who appear in our courts as well as for the preservation of our modern social order. (Rothman at 24.)

So, what does Rothman’s text tell us about the proper judicial response to our current legal environment and the repeated verbal attacks directed at federal district court judges? Quite a lot, it turns out.

First, Rothman admonishes judges not to offer public comment on any pending case in any court. (California Code of Judicial Ethics, Canon 3B (9).) That is a broad prohibition. The roots of this restriction are found throughout the California Code of Judicial Ethics. Canons 1 and 2 require judges to maintain public confidence in the judiciary, while Canon 2A forbids judges from making “statements, whether public or nonpublic,

that commit the judge with respect to cases, controversies, or issues that are likely to come before the courts or that are inconsistent with the impartial performance of the adjudicative duties of judicial office.” Further, Canon 4 requires judges to conduct themselves outside the courtroom so “as to minimize the risk of conflict with judicial obligations.

The proper functioning of our courts depends on judicial officers following these restrictions. Central to this idea is that public trust in our courts is contingent on an impartial judiciary. As the Advisory Committee commentary to Canon 1 recognizes, “[a]lthough judges should be independent, they must comply with the law and the provisions of this code. Public confidence in the impartiality of the judiciary is maintained by the adherence of each judge to this responsibility. Conversely, violations of this code diminish public confidence in the judiciary and thereby do injury to the system of government under law.”

At the same time, judges are urged to communicate with the public about the importance of preserving judicial independence and the role of the rule of law in our legal system and our democracy.1

Faced with these competing directives, Chief Justice John Roberts’ 2024 Year End Report on the Federal Judiciary, Justice Sonia Sotomayor remarks at Georgetown Law Center, and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s recent address to the First Circuit Judicial Conference entitled Preserving Judicial Independence and the Rule of Law provide us with valuable illustrations of how judges are to balance these twin obligations. And

as members of the legal profession, the justices’ observations provide us with meaningful insight into the relationship between judicial independence and the rule of law. Finally, Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Sotomayor and Jackson provide guidance to members of the legal profession on our collective responsibility to preserve and protect the rule of law in American society.

Our second president, John Adams, articulated the general concept of the rule of law as “ a government of laws, not of men. ” Thomas Paine in Common Sense popularized this idea, imploring his countrymen, “In America, the law is king. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other.” Today, the Administrative Office of the United States Courts defines the rule of law as “ a principle under which all persons, institutions, and entities are accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced, independently adjudicated, and consistent with international human rights principles.”

See, Conversation with Patricia Guerrero, Public Policy Institute of California, November 3, 2023 at 30:14 (www.ppic.org/event/a-conversation-with-chief-justice-of-california-patricia-guerrero/). See also, Cal. Code Jud. Ethics, Canon 4B, Advisory Committee Commentary (“As a judicial officer and person specially learned in the law, a judge is in a unique position to contribute to the improvement of the law, the legal system, and the administration of justice []”). 1

The rule of law has been subject to varying definitions by social theorists, but it is generally understood to comprise formal and procedural elements structuring the way a community is governed. The formal elements require that law is: (1) general (applying equally to all persons), (2) public (available as public knowledge to persons subject to it), (3) prospective (promulgated in advance of people’s responsibility to comply), (4) intelligible (such that persons are able to comprehend what the law requires), (5) consistent (similar cases are treated similarly), (6) practicable (so that persons can comply), (7) stable (such that persons are able to fashion their behavior), and (8) congruent (with other rules and dictates).2

constitutional rights of all before the court, including self-represented persons. ” (Rothman at 24.) It is a broad legal checklist.

The procedural elements of the rule of law concern the processes by which the law is administered. Central to these procedural aspects is: (1) a hearing, (2) before an independent and impartial tribunal, that is (3) required to administer legal norms based on evidence (4) involving parties who possess the right to counsel, (5) the right to be present, (6) the right to confront witnesses, and (7) the right to present evidence and argument. Within this structure, judicial independence is a generally accepted prerequisite to the rule of law. Rothman adopts this general framework and provides a helpful operational definition: “Observing the rule of law involves the fair application of the federal and state constitutions, statutes, case law, rules of court, the Code of Judicial Ethics, and other laws, ensuring the

2

Judicial independence for Rothman “does not mean freedom from constraints of the law.” Rather, judicial independence ensures that decisions “ are not influenced by political considerations, public opinion, the need to be popular, fear of losing an election or the desire to curry favor with the powerful.” (Rothman at 24.) Judicial independence also does not mean that judicial decisions should be insulated from criticism. See Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 24 (1958) (Frankfurter, J., concurring) (“Criticism need not be stilled. Active obstruction or defiance is barred.”) Criticism of judicial reasoning is part of a healthy democracy. But judicial independence requires that judges rule independently in each case in a manner the judge believes the law requires. Verbal attacks on individual judges designed to intimidate judges to rule a certain way are, within this framework, attacks on the rule of law.

Judicial independence and its relationship to the rule of law was the dominant theme of Chief Justice Roberts’ Year End Report. The Chief Justice observed: “Our political system and economic strength depend on the rule of law.” (Roberts, 2024 Year End Report on the Federal Judiciary, at 8.) The rule of law, in turn, is predicated on an independent judiciary. Quoting his predecessor Chief Justice Rehnquist, Chief Justice Roberts explained, the “Constitution protects judicial independence not to benefit judges, but to promote the rule of law.” (Roberts at 3.)

For a more complete discussion of these elements see, L. Fuller, The Morality of Law, Yale University Press (1964); HLA Hart, The Concept of Law, 3d ed. Oxford Clarendon Press (2012); and J. Rawls, A Theory of Justice, Harvard Univ. Press (1999) at pp. 206-13.

And yet, Chief Justice Roberts warns the rule of law is under attack. Observing that vigorous debate and criticism of judicial decisions are inevitable and foster a more robust democracy, the Chief Justice dedicates the bulk of his report to addressing the current threats to judicial independence and the rule of law. “I feel compelled to address four areas of illegitimate activity that, in my view, do threaten the independence of judges on which the rule of law depends: (1) violence, (2) intimidation, (3) disinformation, and (4) threats to defy lawfully entered judgments.” (Roberts at 5.)

Focusing on the threats of the political branches’ open defiance of court orders, Chief Justice Roberts is candid: “judicial independence is undermined unless the other branches are firm in their responsibility to enforce the court’s decrees.” (Roberts at 8.) He cautions that “[w]ithin the past few years, however, elected officials from across the political spectrum have raised the specter of open disregard for federal court rulings. These dangerous suggestions, however sporadic, must be soundly rejected.” (Roberts at 8.)

Roberts is offering both a warning and a plea. He highlights the fragility of the rule of law within the current political environment and our information ecosystem. He acknowledges that judges must stay in “ our assigned areas of responsibility.” (Roberts at p. 9.) And he expresses optimism that judges and the other branches of government will achieve the “successful cooperation” essential to our nation’s success. Central to this enterprise is respect for judicial independence and the rule of law.

Chief Justice Roberts repeated these themes in remarks at a judicial event in Buffalo, New York on May 7. “Impeachment is not how you register disagreement with decisions,” Roberts observed. Speaking to the broader function of judges in our system of government, Roberts explained: “[t]his job is obviously to decide cases, but in the course of that, to check the excesses of Congress or the executive, and that does require a degree of independence.”

Justice Sotomayor’s Remarks at Georgetown University Law Center (March 2025)

Speaking to law students and faculty at Georgetown, Justice Sotomayor opened by defining the rule of law. After referencing the definition in Black’s Law Dictionary, she adopted a framing that she found more satisfying from the World Justice Project: “[t]he rule of law is a durable system of laws, institutions, norms, and community commitment that delivers four universal principles: accountability, just law, open government, and accessible and impartial justice.” By “just law” she adopted the following explanation “the law is clear, publicized, and stable and is applied evenly. It ensures human rights as well as property, contract, and procedural rights.”

around a sense of ethics” “ a commitment by the society to abide by certain norms that are fundamental to our existence.”

Justice Sotomayor then posed the question: “what is the right thing that law should be aspiring to accomplish?” She observed that in the present moment there are a lot of questions about what are our “ common norms. ” And there is urgency for us to align on a set of shared values. “Once we lose our common norms, we ’ ve lost the rule of law completely.” Having posed the central question, Justice Sotomayor answered it: our courts must be (1) “fearlessly independent,” (2) “protective of rights,” and (3) “ ensure that the state is respectful of both.” Then, as if to emphasize this last point, the Justice added: “We have to demand that all others respect both of these principles.”

Without reference to any of the specific statements directed at federal or state judges, Justice Sotomayor was keenly sensitive to the current political environment: “[m]ore than ever, we have to get up and explain and repeat and explain again why judicial independence is critical to everyone ’ s freedom.” And, reflecting on the subject, Justice Sotomayor urged that we identify the principles and values that are incorporated into our conception of the rule of law. These principles, in turn, must “revolve

Justice Sotomayor takes as a starting point that the independence of the judiciary must be unqualified. Further, the role and function of the courts, as a co-equal branch of government, must be respected by others. And like her colleague Chief Justice Roberts, she views establishing these precepts as a collective responsibility of the legal profession.

Justice Jackson’s Address to the First Circuit Judicial Conference (May 2025)

Finally, Justice Jackson’s remarks on judicial independence and the rule of law provide the most detailed recent examination from our Supreme Court justices. Her address captured the attention of the national press. The New York Times headline proclaimed: Attacks on Judges Undermine Democracy, Warns Justice Jackson. (Perez Sanchez, NY Times, May 1, 2025) The Justice offered a nuanced and thoughtful explanation of the importance of judicial independence and its relationship to the rule of law in our system of government.

Justice Jackson opened her remarks by addressing the “elephant in the room. ” Namely, “the relentless attacks and disregard and disparagement that judges around the country are now facing on a daily basis.” But rather than focus on a specific case, defend a particular judge or respond to a particular verbal accusation, Justice Jackson addressed the social dimension of this dynamic.

Justice Jackson observed: “[a] society in which judges are routinely made to fear for their own safety or their own livelihood due to their decisions is one that has substantially departed from the norms of behavior that govern in a democratic system.” She explained: “[a]ttacks on judicial independence are how countries that are not free, not fair, and not rule-of-law oriented operate.”

Justice Jackson then expanded on this theme: “having an independent judiciary defined as judges who are ‘indifferent to improper pressure ’ and ‘determined to decide each case according to the law’ is one of the key ingredients that makes our free, fair, and law-centered society work.”

Justice Jackson highlights the consequences of verbal attacks on individual federal district court judges within a values-based social order. She is further sensitive to the broader systemic impact. “The attacks are also not isolated incidents; that is, they impact more than just the individual judges who are being targeted. Rather, the threats and the harassment are attacks on our democracy on our system of government. And they ultimately risk undermining our Constitution and the rule of law.”

So, what are judges supposed to do in the current environment to ensure judicial independence is preserved? Justice Jackson offers two suggestions.

First, judges should engage with others about what we do and our role in defending the Constitution and the rule of law. Second, judges need to remind ourselves of the “ core values that guide us in our daily work.”

Here, Justice Jackson sounds a lot like Judge Rothman. Rothman admonishes California judges: “[w]e need not be reminded of the fragility of the rule of law when public confidence is shaken, or the degree to which public confidence in public institutions has deteriorated in recent times. Articulation of the moral principles and values to which the judicial institution binds itself should serve to encourage public confidence in that institution, and respect for its decisions.” (Rothman at 24.) Stated differently, Rothman urges California judges to speak, write, and participate in activities promoting the rule of law by articulating the “moral principles and values” that define our system of justice. Underscoring the same themes as Justice Sotomayor, Judge Rothman emphasizes that this articulation should, in turn, be designed to promote public confidence in our judicial system.

Chief Justice Roberts, Justices Sotomayor and Jackson, and Judge Rothman further acknowledge the fragility of the rule of law in a society where public confidence in the judicial system is shaken. This issue is of increasing urgency as favorable views of our Supreme Court continue to be close to historic lows.3

Here in Marin County, the Superior Court’s moral principles and values are set out in our mission: “To ensure fair and equal access to justice and serve the public with dignity and respect.” The core moral principles guiding our courts include equality, fairness, accessibility, judicial impartiality, and respect for human dignity. And central to this mission is fidelity to the rule of law. It is a commitment to each person who appears in our courts that they are afforded the fair application of the state and federal constitutions, statutes, case law, and rules of court. We don’t make up the rules as we go along

For Rothman, adherence to the rule of law is a central “pillar” to judicial decision making. More broadly, it is vital to the American ethos. It is an animating force in our collective, intuitive sense of ordered liberty. As Justice Ruth Bader

Ginsberg wrote, an independent judiciary is “essential to the rule of law in any land,” yet it “is vulnerable to assault; it can be shattered if the society law exists to serve does not take care to assure its preservation.” As judges, lawyers, and public citizens committed to the quality of justice in our country, we are called by these times to reaffirm our adherence to the rule of law. And we are summoned to recommit ourselves to the moral principles that define our judicial institution.

4

As Justice Jackson reminded her colleagues in the First Circuit, “[o]ther judges have faced challenges like the ones we face today and have prevailed.” Now it is our turn.

Judge James Schurz was appointed to the Marin bench in 2024 He earned a Juris Doctor degree from the University of California, Berkeley School of Law and Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts degrees in European History from Stanford University Schurz, a San Francisco resident, has worked at the Morrison Foerster law firm since 1998, according to the governor’s office He has a law degree from the University of California at Berkeley and was a California S preme Co rt clerk from 1989 to 1990

3

Pew Research Center, Favorable Views of Supreme Court Remain Near Historic Low (August 4, 2024) (Fewer than half of Americans (47%) express a favorable opinion of the court. And just 24% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents view the Supreme Court favorably) at www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/08/08/favorable-viewsof-supreme-court-remain-near-historic-low/

4

R.B. Ginsburg, Remarks on Judicial Independence, Conference of American Judges Association, 2006.

Elizabeth Bohannon

My grandparents stared out the window of their fourth-story apartment, looking down on the streets of Budapest. Blood still stained the pavement. Bouquets marked the places where the dead had fallen. Bullet holes pockmarked the buildings. The air hung heavy with the smell of smashed hope.

It was 1956. The Iron Curtain was rising. The Soviets were sealing borders, erecting walls to trap citizens. My grandparents faced a choice: flee now or risk never seeing their son again.

Their only child - my father - had escaped five years earlier. They had already lived through Nazi and Soviet occupations. They’d huddled in basements while bullets rained overhead, watched friends disappear, and had seen neighbors turn on each other. When students rose up in protest, they dared to hope. But the tanks rolled in. The students fell. It became clear: no one was coming. Not America. Not the West. Not anyone.

They didn’t leave for safety. Safety was long gone. They left for love, for the hope of reunion. Whatever unknowns lay ahead, they refused to die on one side of the world while their son lived on the other.

This choice shaped our family’s understanding of freedom, belonging, and the price of authoritarianism. It also shaped mine.

My father embraced America’s melting pot with pride, believing assimilation was the price of inclusion. My grandfather, once a prominent surgeon, gave up his status and rebuilt a life. For him, the transplant took. My grandmother, however, mourned. She missed her family and friends, but also grieved a culture slipping through her fingers. She came to believe that sameness was safety, and that difference was dangerous.

I chose my own path. I married outside my race and raised two multiracial daughters in Marin. Where my grandmother saw risk in difference, I discovered richness. Where she feared otherness, I found connection.

It hasn’t always been easy. Bridging difference is messy. But in those moments when we stretch to understand one another, a new perspective opens. A possibility we hadn’t seen before. A future we might choose together.

This isn’t just my family’s story. It’s America’s. And right now, fascist rhetoric is dominating political discourse on the MAGA right. Old hatreds are being repackaged as patriotism. Authoritarianism is being marketed as strength. History is repeating itself in real time.

We attorneys must defend the rule of law, certainly, but the judicial branch is not merely a system of rules. It’s the promise that no one is above those rules, and that everyone belongs under their protection. When we take a stand for the rule of law, we stand for each other, our community. Our people. All of us.

Real democracy isn’t built on sameness. It’s built on the radical act of choosing to stay at the table, especially when we don’t agree. It’s built on the idea that we can be different and still belong to one another.

The questions in front of us now are these: What do we choose, and who do we become when we choose each other?

Professional coach, attorney, mediator, speaker, and facilitator with deep expertise in labor and employment law, professional coaching, and conflict management In her latest venture, Co lab Coaching & Legal Services, Elizabeth Bohannon applies knowledge, experience, skills and accumulated wisdom to transform lives and workplaces through coaching (professional, team, and conflict coaching)

She collaborates with individuals and teams to identify and overcome obstacles, build resilience, unlock their power, experience the satisfaction of conscious choice, build calm, respectful relationships and reach their full potential

GENERAL MEMBERSHIP

SOCIAL (IN PERSON) Thursday, August 7th 5:00 PM - 6:30 PM Thirsty Thursday

GENERAL MEMBERSHIP

SOCIAL (IN PERSON) Sunday, August 24th 11:30 AM-3:00 PM

1.0 GENERAL CLE

SAVE THE DATE: MCBA End-ofSummer Members Picnic

Marin Trial Lawyers Association (MTLA) JUDGES DINNER Tuesday, September 9th 6:00 PM-9:00 PM Peacock Gap Clubhouse

CALIFORNIA COASTAL CLEAN UP (IN PERSON) Saturday, September 20th 9:00 AM-12:00 PM MCBA Community Service Day

David F. Feingold

The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary in the same hands … may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny. James Madison, Federalist Paper No. 47, 1778

Without an independent judiciary… all the reservations of particular rights or privileges would amount to nothing. Alexander Hamilton, the Federalist No. 78, 1778

How often do you think of yourself as a revolutionary? If the answer is not very often, you should, more often. Especially now.

We have a chief executive of the United States who has mounted an unprecedented attack on our independent judiciary. To the extent these attacks are successful, it will largely be due to the fact that, as founding Father Alexander Hamilton noted, the judiciary is the weakest branch as it has "neither sword nor purse".

his statements on a conservative podcast in 2021 suggesting that Trump, if reelected, should fire every midlevel bureaucrat and every civil servant in “the administrative state” and when the Courts try to stop him, that he should “ … stand before the country like Andrew Jackson did and say: ‘The chief justice has made his ruling. Now let him enforce it’”. Mr. Ward asked him if this was still his view. His one word answer was “Yup.”

In April of 2025, Columbia Law Professor Thomas Schmidt, in an article in The Atlantic titled “The Supreme Court has no Army,” [argued] that the authority and independence of the Supreme Court, and by extension every lower court, depends entirely on the vigilance of the American people.

An independent judiciary is one that is free to uphold the rule of law without prejudice against or favoritism toward special interests, political or otherwise. When the system is attacked, it has to be defended. Yet it is not (generally) the courts and the judges who can or will provide that defense, as they are restricted in their ability to respond (by codes of judicial ethics?). This restriction is important to ensure the dignity of justice system, prevent interference with pending cases, and to keep the judicial system independent of political pressures. So who is uniquely suited (pun intended) to defend the independence of the judiciary?

In 2007 I recall being riveted by the images of Pakistani lawyers protesting the government’s suspension of the chief justice of Pakistan's Supreme Court, who had defied the authoritarian government’s actions. The actions included corruptly privatizing government-owned industries, and disappearing citizens without due process. One such image accompanies this article.

The protests escalated, and in November of 2007 there was a nationwide crackdown on lawyers, which included a raid on the Lahore High Court Bar Association in which police baton-charged and threw tear gas into the premises, and then arrested over 800 lawyers. The “Black Coat Protests” expanded as welldressed lawyers took to the streets and refused to back down. In the end the protests, also known as “the Lawyers Movement,” were successful in having the chief justice reinstated.

Lawyers in lands with authoritarian governments have often looked to the United States for inspiration to defend their own fledgling judicial systems. The best among them know how critical it is to have a system of government with checks and balances, and how an independent judicial system is the best protection against tyranny. In Pakistan, at least in 2007, they were willing to, quite literally, fight to protect it.

In pre-revolutionary Boston, it was the lawyers in the upstart colonies who were the leaders in demanding liberty and justice from the British. Thomas Gage, commander in chief of British forces in the early days of the revolution, made it clear in a 1765 letter to the King that “the lawyers are the Source from whence the clamors have flowed in every Province.”

Can we ultimately be the source from where the clamor will flow? Will we be? Or perhaps the better question is, must we be?

I hope that we American lawyers will not find ourselves lobbing tear gas back toward police lines in a desperate fight for justice and the rule of law. I really do. It seems unthinkable. It would be unprecedented. But then again, what we are facing today is unthinkable. And it is unprecedented.

For me, I will keep the image of the black-suited lawyer in Pakistan in mind as I do what I can, when I can, to fight for our independent judiciary.

David F Feingold is a partner at Ragghianti Freitas LLP, where he practices real estate and construction law, with a focus on common interest developments He also enjoys serving as a mediator and helping real people solve real problems Dave is a former Reserve Police Officer with the San Rafael Police Department and was President of the MCBA in 2003 This is an update of an article he published in the Marin Lawyer in 2019

Len Rifkind

President Trump and his administration through its policies and executive orders enacted in its first 100 days represent an unprecedented assault against the rule of law, an open attack on the foundational concept of an independent judiciary, resulting in a hemorrhage of our constitutional system by seeking to disembowel a co-equal branch of our constitutional republic--the judiciary-- by reducing or eliminating due process and equal protection. Recent Trump administration executive orders, policies and pronouncements have resulted in xenophobia against judges who may rule against the administration policies, and against lawyers who represent unfavorable clients, resulting in making all of us less free and therefore less safe. For example, recently the Trump Administration sought to impeach a judge because of an unfavorable ruling rather than seeking the normative remedy of appeal, resulting in a rare and pointed rebuke by Chief Justice John Roberts of President Trump. The Trump administration has expanded its attacks on the rule of law by also seeking to intimidate law firms and attorneys and chill advocacy of clients unpopular with the administration contrary to First and Sixth Amendment rights to freedom of speech and right to counsel, respectively. The Trump Administration even arrested a state court judge in Wisconsin charged with obstruction of justice in connection with an ICE effort to deport a party appearing in an unrelated court matter.

The public must be informed of the administration’s authoritarian tilt, and educated that judges must follow the law, not public opinion or political preference. Representation by counsel of choice with due process are constitutional bedrocks of our constitutional system for the

past 249 years. The United States is not any country; it is a beacon of light to all the peoples of the Earth as the one place where the rule of law, due process and equal protection apply to all its residents, citizens or not. In direct conflict with these inalienable rights, please consider the following partial summary of President Trump’s recent executive orders:

Seek mass deportations and use of the Alien Enemies Act of 1789 to detain and deport immigrants without due process, including extrajudicial rendition of 238 persons in the U.S., of Venezuelan descent to an El Salvadoran prison in defiance of a federal court order.

Deploy the military for border security in violation of the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, which generally prevents the President from using the military as a domestic police force.

Revoke affirmative action and all DEI programs, and openly use the Justice Department to attack any and all businesses, educational organizations and people who do not comply.

Withdraw from the Paris Agreement on climate change.

Declare a national emergency to prioritize production of fossil fuels.

Create the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE).

Withdraw from the World Health Organization.

Implement a federal hiring freeze.

My effort here is not to politicize these issues, as President Trump fairly won the 2024 election and similarly fairly lost the 2020 election, but rather for our bar members to decide for themselves if a policy enacted by Executive Order supports the rule of law and/or attacks an independent judiciary, and whether the executive orders and policies are constitutional. We have a duty as officers of the court to speak up, speak out, and speak with zealous advocacy on these issues which do not conform with the Constitution, the rule of law, which cannot stand with an independent judiciary having the ability to interpret the law.

In the next few months, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear a number of key cases on these very issues of dire constitutional import. These cases include: A challenge to Executive Order 14160, which seeks to end birthright citizenship for children born in the U.S. to undocumented immigrants; Deportation of Venezuelan immigrants to a Salvadoran prison without

due process; Elimination of collective bargaining rights for federal employees; Dismissal of FTC commissioners in violation of US Supreme Court precedent and bipartisan structure mandated by law; Whether President Trump is immune from prosecution for attempting to overturn the 2020 election results; Review of a law enacted as part of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, making it a felony to corruptly obstruct, influence or impede an official proceeding, as it may apply against

defendants associated with the 2021 U.S. Capitol attack for attempting to obstruct that year’s Electoral College vote count, as well as it may apply to President Donald Trump for alleged activities to obstruct that election.

Never in the history of our country has so much depended in large measure on our Chief Justice to fulfill his constitutional mandate to support the rule of law, and lead the third branch of government, the judiciary, to perform its fundamental core function to interpret policies and executive orders promulgated almost daily by the Trump Administration. We note, there is not a single piece of legislation that President Trump has managed to pass, but rather, our country faces an onslaught of executive orders, reflecting the whims of a single person, not the collective judgment of two branches of government, legislative and executive, which appear to be literally under the control of President Trump Our country desperately needs the Judicial Branch to fulfill its constitutional duty to interpret the law without undue interference. Our judiciary cannot do that without the support of members of the bar; it is our duty for the sake of our constitutional democracy to stand shoulder to shoulder with the bench in support of the rule of law and an independent judiciary unafraid to interpret the law.

Public Advocacy. As stated at a recent conference of U.S. District Judges, “silence on the part of the bar means acquiescence.” National, state and local bar associations have released public statements rejecting federal governmental action that punishes lawyers and law firms who represent certain unfavorable clients or punish judges who rule in certain ways. The ABA publicly rebuked the Trump administration for stating judges can be impeached over unfavorable rulings. Members of the bar have the training, knowledge and skill to educate the public that an existential threat to democracy has been unleashed by the Trump administration in its first 100 days with more than 1300 days remaining in President Trump’s term. Speak up and make yourselves heard at every level of government and public discourse that our 249year-old constitutional democracy and its norms of three equal co-branches of government supporting the rule of law, due process, equal protection, and an independent judiciary to protect those precious rights.

Write letters to local newspapers.

Author op-ed articles.

Post on social media.

Communicate with family, friends, and neighbors.

Write open letters to your clients.

Write letters to your elected representatives at the local, state, and federal levels.

Support amicus curiae brief writing efforts by various non-profits seeking to protect the rule of law.

Support and join peaceful protests at the local, state, and national levels.

Participate in a one-day strike in the United States, ‘A Day Without Lawyers,’ who strike in support of an independent judiciary and the rule of law.

Challenge illegal executive orders. Provide pro bono legal services for all adversely affected by unconstitutional Trump administration policies.

Actively support bar leadership at the local, state and national levels by volunteering your time and talent.

Contact and write letters to local, state and federal representatives so our elected leaders hear the immutable and irrefutable objection by the bar to Trump administration policies that attack the rule of law, an independent judiciary, and our fundamental constitutional rights to due process and equal protection.

In conclusion, we are at an inflection point in history. In the 1930’s in the middle of the Great Depression, President Roosevelt in his first 100 days passed 15 pieces legislation that became the New Deal, led us out of what had been the worst economic downturn in our Country’s history, to victory in World War II, and resulted in 80 years of prosperity, peace and economic growth unrivaled in the history of the world.

Now in just a few short months, the world order as we have known it as Americans, is changing, and it is not changing for the better. We cherish our Constitution, as appropriately amended over time because it provides the fundamental framework for our inherent freedoms as reflected in the Bill of Rights. Members of the bar, stand up and be counted, your written and advocacy skills have rarely been needed as much as they are now to support the rule of law and an independent judiciary to weather the storm of the current administration.

Len Rifkind has been a California licensed attorney for 37 years and is the principal of the Rifkind Law & Mediation PC, with practice areas in real property transactions and related litigation Len serves as a neutral for Resolution Remedies, LLC, and Of Counsel to the law firm DeMartini, Walker & Ghaedi, LLP He has been selected to Superlawyers, Northern California Real Estate Law (2012-2024) Previously Len served as a past president of the Marin County Bar Association (2005), served on the Larkspur City Council from 2009-2013, Mayor in 2012, and president of the Marin County Council of Mayors and City Councilmembers in 2013 Len is also a principal and general counsel with Grand Partners, LLC, a real estate development company specializing in acquiring and stabilizing environmentally contaminated commercial properties

MCBA LEADERSHIP CIRCLE MCBA LEADERSHIP CIRCLE

Scott Buell Scott Buell

Buell Law & Mediation

Buell Law & Mediation

Peter Kleinbrodt

Peter Kleinbrodt

Freitas

Molly Cohen Phipps

A fascinating detail about being a student is the awareness that one’s perspective is widening. On one hand, you may know the shape of what lies ahead on your learning journey. You have a map. You’ve talked to other travelers. You’ve heard about the destination. There are enough reasons compelling you to go that you’ve packed and embarked on the journey. But no matter how prepared you are or think you are nothing is the same as actually walking that trail and finding your own personal understanding along the way.

A fascinating detail about being a student is the awareness that one’s perspective is widening. On one hand, you may know the shape of what lies ahead on your learning journey. You have a map. You’ve talked to other travelers. You’ve heard about the destination. There are enough reasons compelling you to go that you’ve packed and embarked on the journey. But no matter how prepared you are or think you are nothing is the same as actually walking that trail and finding your own personal understanding along the way.

I am finding this truer as a law school student than during any other stage of my personal or professional education. And I am deeply curious: Is the amount of national legal activity, attention, and challenge appearing in American news today “normal?”

It would be silly to think that my own perceptions and awareness aren’t changing. One

reason I’ve always been drawn to law is the general understanding that it supports our society at large. I find it both profound and fascinating to be able to directly identify my doctrinal subjects throughout everyday life. (Sure, we have protections, but what is an unreasonable search or seizure anyway? Also, contracts are everywhere.)

Still, there has been a major surprise. I thought most of the interesting landmarks along this hike were going to be visible from the trail towards legal education. I expected that a steady focus on legal areas of concern was natural for those who have either already reached my destination, or who picked up the right tools or interest along the way to know how to look for it. Instead, there seems to be a bombardment of legal issues and questions to the broader public on a near daily basis. Headlines are plentiful, grandiose, and looming trailside. No need for binoculars to glean legal news events are being broadcast on billboards that rise higher than the forest I’m hiking through.

On one hand, I’ve heard it said that each generation faces its own wave of major issues and social concerns. It can be natural for one to think the present day is “the worst it’s ever been.” But at the same time, I struggle with reactions to warning signs that seem to be dismissive.

The news broadcasts several iterations of “showdowns” between our judicial and executive branches. Topics at issue include immigration, access to information safeguarded by legislative branches, and DEI. To my only partially trained eye, there seem to be tactical attempts by one branch to reach a particular goal that could jeopardize the entire system.

A micro example presented itself over a weekend. I started assigned reading for my upcoming Professional Responsibility Course, which includes my first foray into the 2024 American Bar Association Model Rules of Professional Conduct. The preamble introduces the responsibilities of a lawyer to uphold the legal process alongside their duty to challenge. A sentence I would not have dwelled on previously is the guidance to “demonstrate respect for the legal system and for those who serve it, including judges, other lawyers and public officials ” (Dzienkowski, John S. Dzienkowski's Professional Responsibility, Standards, Rules, and Statutes, 2024-2025. Available from: West Academic, West Academic Publishing, 2024.)

I recall reading a month ago about the Justice Department’s attempts to circumnavigate a federal judge’s response requirements to, and oversight of, an immigration issue. (Feuer, Alan. “Administration’s Details on Deportation Flights ‘Woefully Insufficient,’ Judge Says.” New York Times, March 20, 2025. Later this weekend, I catch up on news and encounter the headline, “Attacks on Judges Undermine Democracy, Warns Justice Jackson.” (Pérez Sánchez, Laura. “Attacks on Judges Undermine Democracy, Warns Justice Jackson.” New York Times, May 1, 2025.

Returning to metaphor, I am eagerly packing my gear for the next leg of my hike towards my legal education. Map forgotten in my hand, I stare up

at a trail-side landmark visible to the untrained eye from miles away from this hiking path. A quote shared by one of my professors rolls through my head; I think of John W. Davis’s commentary on the role of lawyers, in that “ we smooth out difficulties; we relieve stress; we correct mistakes; we take up other men ’ s burdens and by our efforts we make possible the peaceful lives of men in a peaceful state.”

All I know is that certain calls to action now resonate more than I could have imagined. The ABA’s Model Rules clearly present the indispensability of the public’s knowledgeable confidence in the justice system and law. Lawyers must act to support the public’s understanding, because “legal institutions in a constitutional democracy depend on popular participation and support to maintain their authority” (Dzienkowski, John S. Supra).

I embrace that I don’t yet have the years of experience and awareness to properly contextualize the current moment. I can only ask is this normal?

Molly Cohen Phipps is the Head of People with local manufacturer, EO Products Her previous background includes fifteen years in hospitality with multistate projects, management company transitions, and new property openings Molly’s passion for service, community, and stewardship drive her work in

s/HR. She has just completed her 1L year at ege of Law.

Marc Hoag

Acknowledgements:

This paper was a personal passion project of mine for the last three months, so I am immensely grateful to those of you who contributed your input, support, and above all, motivation to keep going. First and foremost, a huge and heartfelt thank you to Stanford University’s Mark Lemley for your time and generosity; your incisive and substantive feedback didn’t just validate my thesis, but sharpened it. Not to state the obvious, but I’d love to meet up some time in Palo Alto. Nancy Rapoport, thank you for your thoughtful edits and comments to the first draft of my paper; you provided the first glimmer that I was perhaps onto something and had to keep going. To Scott Buell and the Marin County Bar Association, thank you for your serendipitous invitation to author an article for The Marin Lawyer just as I happened to be putting the finishing touches on this paper and looking for a place to get it published. Finally, thank you to my wife Crina Hoag for your boundless love and support, and to our 3 year old for keeping us giggling day and night; I love you both.

-Marc May 22, 2025

Author’s Note:

Shortly before this paper went to press, the U.S. Copyright Office released the pre-publication draft of the third installment in its Generative AI Training Report. The report seems to validate, at least in part, much of my central technical arguments, i.e., that AI training “involves creating a statistical model” and “will often be transformative.” However, the Office assumes applicability of copyright law to AI training as a foundational matter and analyzes the issue chiefly through a fair use lens. While my paper diverges on this fundamental point – arguing that AI training should fall entirely outside copyright’s domain –the Copyright Office’s technical observations 1

about the nature of AI training align well with, and indeed reinforce, my premises and fair use analysis developed below. And yes, while I of course leveraged AI (specifically GC ai and ChatGPT o3 and 4.5) for brainstorming and proofreading, all analysis and final copy remain entirely my own. 2

U.S. Copyright Office, Copyright and Artificial Intelligence, Part 3: Generative AI Training, Pre-Publication Version (May 2025), https://www.copyright.gov/ai/Copyright-and-Artificial-Intelligence-Part-3-Generative-AI-Training-ReportPre-Publication-Version.pdf 1 https://getgc.ai 2

This paper examines artificial intelligence (“AI”) models known as generative pre-trained transformers (“GPTs”), which we refer to as “generative AI” or “gen AI.” Familiar examples include OpenAI’s ChatGPT, xAI’s Grok, Google’s Gemini, and Anthropic’s Claude.

Here, “models” refers to large language models (“LLMs”) trained on vast troves of scraped internet material – material that, as set forth below, is neither “copied” nor “fixed” in the copyright sense under 17 U.S.C. §101; or, even if it is, occurs without volition of the AI developers themselves.

For this discussion, “AI,” “models,” and “LLMs” are synonymous unless stated otherwise. Likewise, “scraping” and “training” are treated as integrated steps in crafting an LLM.

“End users” or similar refers to individuals or companies that use various AI products.

Finally, “input” and “output” refer, respectively, to the user’s “prompting” of an AI model which produces a response, be it written text, voice, music, video, sound, or otherwise.

Infringement

The argument that training generative AI models necessarily infringes on copyright is the easy, default view to accept; arguing the alternative is neither trivial nor popular. (Fortunately, however, the views in this paper are in good scholarly company, as demonstrated throughout.)

In contrast, generative models that produce images, video, music, or voice rely on architectures – such as diffusion models, GANs, or transformer variants – distinct from GPTbased text models. Though the core logic presented here applies broadly – and we even discuss briefly the same with respect to the training of AI image generation tools – AI training and generation of non-text media involve distinct technical specifics that raise additional considerations beyond the scope of this paper.

As we await a decision in the pivotal New York Times Co. v. Microsoft Corp. (No. 1:23-cv-11195 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 27, 2023)) – colloquially, NYT v. OpenAI – courts around the world are similarly grappling with whether AI training – scraping the entire internet to train models like OpenAI’s ChatGPT – infringes on creators’ copyrights. UK and French publishers’ and authors’ recent lawsuits against Meta, and numerous other cases brought by visual artists and content creators worldwide all share a common premise: that copyright law necessarily applies to AI training in the first place. 3,4

This paper challenges that foundational assumption. Rather than merely examining whether AI training constitutes fair use or otherwise qualifies as non-infringing under existing copyright frameworks, the question is reframed:

Whether AI training, in general, falls entirely outside copyright law’s domain?

https://www.dataguidance.com/news/uk-org-files-complaint-against-meta-use-data-ai

3 https://www.reuters.com/technology/artificial-intelligence/french-publishers-authors-file-lawsuit-against-meta-aicase-2025-03-12

NYT v. OpenAI, likely to be the landmark decision that establishes the precedent for how companies can train their AI models, exemplifies the growing tension between traditional copyright frameworks and emerging AI technologies, raising issues that transcend national boundaries. In fact, the rapid, global proliferation of AI requires a unified fabric of interoperable rules and policies, and not the cobbled together, thus far incompatible patchwork of regulations currently evolving in parallel around the world.5

The international landscape offers instructive context for this US debate. The UK government recently proposed a copyright framework allowing AI companies to train models on copyrighted materials unless rights holders actively opt out. This has sparked controversy, with critics arguing it undermines copyright protections and violates international agreements like the Berne Convention. 6 7

The Berne Convention, a foundational copyright treaty, enshrines the principle that copyrighted works are protected without formalities, meaning creators shouldn’t need to take additional steps to prevent unauthorized use. Some legal experts contend that the UK’s opt-out system effectively introduces such a formality – by requiring creators to proactively safeguard their rights –potentially conflicting with the treaty’s standards and regulatory intent.

Interestingly, the EU Copyright Directive takes a similar approach, permitting AI training on copyrighted materials unless rights holders opt out. However, the EU system provides more explicit mechanisms for managing and enforcing these opt-outs, such as machine-readable reservations, clear national implementation guidelines, and structured stakeholder dialogue. These features offer a more balanced framework, arguably aligning better with international norms and drawing less criticism than the UK’s broader, less defined proposal. 8

These international approaches, details of which are beyond the scope of this paper, provide valuable context for US courts and policymakers grappling with similar questions. However, as this paper seeks to demonstrate, the fundamental nature of AI training should render these regulatory debates largely moot, and fall outside copyright’s domain entirely.

MEMBER NATIONS OF THE BERNE CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF LITERARY AND ARTISTIC WORKS

MEMBER NATIONS OF THE BERNE CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF LITERARY AND ARTISTIC WORKS

5 https://www.publishers.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Legal-Opinion-of-Nicholas-Caddick-KC-BerneConvention.pdf

I have been developing the framework for just such an organization called AI SIGMA: The AI Standards Institute for Global Machine Alignment. To learn more, please visit https://aisigma.org

6 Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, Sept. 9, 1886, as revised at Paris on July 24, 1971 and amended in 1979, S. Treaty Doc. No. 99-27 (1986)

8

7 Directive (EU) 2019/790 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC, 2019 O.J. (L 130) 92.

The entire discussion over whether AI model training constitutes copyright infringement is based on a category error, a fundamental mischaracterization and wholesale misunderstanding of what AI models actually do with training data. Discussions have improperly started with the question of infringement, when they should first begin with examining the threshold applicability of copyright law to this novel technological process.

This analysis attacks the scope question – i.e., whether training itself creates an infringing derivative work – but it does not discard the fair use defense; indeed, if courts insist on misclassifying training as “copying,” then the fair use fallback remains essential.

Crucially, copyright law defines “copies” as “material objects... in which a work is fixed by any method... and from which the work can be... reproduced,” and a work is “fixed” only when its embodiment is “sufficiently permanent or stable to permit it to be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than transitory duration.” 9

For an activity to potentially infringe copyright, it must first meet the threshold requirement of creating “copies” in a legal sense. AI training fundamentally fails to meet this basic requirement because AI models do not store or reproduce copyrighted works in, or from, a fixed

9

17 U.SC. §101

or otherwise directly retrievable manner. Or, if it does, such “copying” or “memorization” occurs without the volition of AI developers (infra.). Simply put, when an end user interacts with an AI model, he or she cannot directly access the training material. Instead, the user provides a prompt, and the model generates an original –i.e., wholly novel – output based on its own “reasoning,” and not by searching and reproducing stored content like Google’s Search index.

Copyright law already accommodates large-scale uses, like library digitization, Google Books, and image indexing, without redefining what constitutes a copy So any rebuttals leveraging a discussion of the scale of AI training misses the point entirely: it’s not about degree, but rather about if; and here, the question itself presupposes a legal framework that simply doesn’t apply.

Geoffrey Hinton – the “Godfather of AI” – 2024 Nobel Prize winner for his foundational discoveries and inventions that have enabled machine learning with artificial neural networks, has said that “[neural nets] don’t pastiche together text they’ve read on the web because they’re not storing any text. They’re storing … weights and generating things.” 10 11

10 Hinton, G. (2023, October 27). Will digital intelligence replace biological intelligence? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iHCeAotHZa4

Linguists amongst you will note that, ironically, “pastiche” means to imitate a style, which AI certainly does, and not, as implied here, to stitch together otherwise disparate fragments of text. However, Hinton was quoting someone else simply to make the point that, in fact, there is no such surgical splicing together of stored content that happens when querying the LLM of a generative AI system.

An AI model doesn’t query a stored index or database of content when prompted, precisely because such content is not in fact stored anywhere. Instead, it generates output based on probabilities encoded in the trained model’s “weights,” numerical parameters that represent the strength of connections between artificial neurons.

In practical terms, the final trained AI model is essentially a “next word predictor,” identifying patterns from the training materials without storing or retrieving them. The US Copyright Office likewise noted that machine learning involves “creating a statistical model” as opposed to verbatim copying to a fixed medium any scraped material.12

During training, an AI system processes vast datasets but does not retain the actual content. It extracts statistical relationships, not fixed expressions, and once training is complete, the original data is effectively discarded. The end user never interacts with the training data directly because the model that remains is a wholly separate, new entity.

This is why an AI model cannot recall or directly retrieve training data. What emerges from this process is not a “copy” in any meaningful legal sense but a system that truly generates novel outputs. Without reproduction, distribution, or the creation of a derivative work, there is no infringement.

Sag (2025) likewise observes that “trained AI models do not replicate the expressive details of

their training datasets; instead, they distill general patterns, abstractions, and insights from that training data.”

Samuelson (2023) leverages a similar argument for AI models that train on images such as Stability AI that “contain[] an extremely large number of parameters that mathematically represent concepts embodied in the training data, but the images as such are not embodied in its model.” 14

This statistical nature of AI training is precisely what accounts for the infamous, and random, AI “hallucinations” or “confabulations.” These occur because AI outputs are based on probabilistic patterns, and not on fixed, retrievable data stored in an index or database, which would yield the kind of certainty one would expect from direct reproduction.

Think of it like a chef learning to cook by reading many recipes: the chef doesn’t memorize or reproduce the recipes verbatim but develops an understanding of flavor combinations and cooking techniques. What remains in the neural network after training is analogous to the chef’s intuition and skill, not a collection of recipes that can be queried verbatim.

12

USCO, Generative AI Training Report, Part III

Sag, Matthew. Copyright and the AI Action Plan. (Mar. 20, 2025), 13 https://matthewsag.com/copyright-and-the-ai-action-plan

14

Samuelson, Pamela. Generative AI Meets Copyright, 381 Science 158, 159 (2023), https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adi 0656

This is not to encourage the strawman that humans learn like AI – even if we accept that such learning is indeed similar in kind, the difference in degree is so vastly disparate that any sincere argument along these lines is irrelevant – rather, it’s evidence that neural networks transform source training materials and leave no truly “fixed” “copies” behind.

Implicitly, therefore, copyright law should not apply to the ingestion and transformation of expressions into abstract statistical patterns, nor to the temporary or ephemeral storage of information in non-volatile media.

So unless one is prepared to rewrite and reimagine entirely the very essence of what copyright infringement means, and, simultaneously, to redefine what it means to “copy” a thing in a “fixed” fashion, then it is clear from this analysis that the learned process of training an LLM, without more, cannot be considered copying with respect to copyright infringement concerns.

“Regurgitating” the Memorization Question Memorization – “regurgitation” of scraped content verbatim – can indeed occur unintentionally with all AI models. This is a probabilistic fluke; a bug, not a feature. Such memorization stems from statistical overlaps, not the intentional storage or retrieval of fixed copies; it’s akin to a human unintentionally recalling a phrase, not distributing a work.

Research on a predecessor to current models –OpenAI’s GPT-2 – as demonstrated by Carlini et al. , underscored this reality. They noted, “[w]e are able to extract hundreds of verbatim text sequences from the model’s training data.”

15 16 17

Subsequent research, including findings from Nasr et al. , likewise verified this phenomenon, and in some cases observed that larger LLMs can exhibit memorization rates 150 times greater than smaller models.

Lemley et al. (2025) refine this point. They tested 13 open-weight models with 56 books from the Books3 dataset and found that while Meta AI’s LLAMA 3.1 70B can indeed encode nearly an entire popular book (in this instance, Harry Potter and 1984) “almost entirely,” the largest models don’t memorize most books either in whole or in part.18

Bracha (2024) stresses that “The GenAI training process is equivalent to a type of learning that has always been permitted under modern copyright: a process of extraction of meta-information from

15 Nasr, M., Hoory, S., Feder, A., Hassidim, A., Matias, Y., Najafi, A., Ribeiro, M. T., Segal, A., Shokri, R., Slonim, N., & Weinberger, K. (2023). Scalable Extraction of Training Data from (Production) Language Models. arXiv:2311.17035 [cs.CL]

Carlini, N., Tramer, F., Wallace, E., Jagielski, M., Herbert-Voss, A., Lee, K., Roberts, A., Brown, T., Song, D., Erlingsson, U., Oprea, A., & Raffel, C. (2021). Extracting Training Data from Large Language Models. arXiv:2012.07805 [cs.CR]

16 Id. 17

18

Mark A. Lemley et al., Extracting Memorized Pieces of (Copyrighted) Books from Open-Weight Language Models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.12546 (Apr. 18 2025).

expressive works that then enables the production of new and different expression. The only difference is that machine learning incidentally involves physical reproduction … of a physical object … from which no human would ever access the expressive content of the work…. Focusing on this difference to label an otherwise allowed activity of learning as infringing is succumbing to a fallacy of physicalism.” 19

Grimmelmann and Cooper (2024), despite advancing an opposing argument, conveniently define precisely for us that memorization occurs when “(1) it is possible to reconstruct from the model (2) a near exact copy of (3) a substantial portion of (4) that specific piece of training data.” They continue to “distinguish memorization from ‘extraction’” (user-intended generation of a nearexact copy) both “from ‘regurgitation’” (the generation of a near-exact copy even without user intent) and “from ‘reconstruction’” (the generation of a near-exact copy from the model by any means).20

It is undisputed that any technological system can be coerced (or “tortured”) or otherwise manipulated to produce an unlawful or otherwise improper result. However, the same research demonstrates that the generated output is coaxed from the manipulation of stored probabilities, and not because the original training material has been copied into a fixed (i.e., non-volatile) medium and directly accessed. Instead, what is stored are abstract statistical patterns encoded as weights, not retrievable copies of the source material.

Moreover, multiple additional factors reinforce this conclusion, further demonstrating why AI training, without more, does not result in copyright infringement. First, verbatim reproduction of training content is extremely rare in modern AI systems, particularly in the absence of deliberate, targeted prompting to produce such results 22

On the other hand, they also take issue with Bracha and contend that “expression and information can be transformed during learning, but they can also be copied directly into model parameters – and the amount that one deems ‘copied’ depends on one ’ s chosen metric for memorization.” 21

Second, AI developers are implementing safeguards to further reduce such memorization and regurgitation, including techniques like differential privacy, dataset cleaning, and deduplication, in an attempt to reduce such errors. Grimmelmann and Cooper seem to concede as much, i.e., that “not all learning is memorization: much of what generative-AI models do involves generalizing from large amounts of training data, not just memorizing individual pieces of it.” 23

Bracha, Copyright in the Age of Machine Production, 38 Harv. J.L. & Tech. 1 (2024).

19 Cooper, A. Feder & Grimmelmann, James. The Files Are in the Computer: On Copyright, Memorization, and Generative AI, 99 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. (forthcoming 2024), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm ?abstract id=4757069

20 Id. 21

While this discussion focuses on text-based models, it is worth noting that “verbatim” reproduction is inherently a linguistic concept – it applies strictly to words and exact textual matches. For other media types (e.g., music, images, video), similarity may be measured differently, often requiring subjective analysis or technical methods like pixelmatching, waveform comparison, or style analysis. This paper does not attempt to address those distinctions.

23

22 Grimmelmann and Cooper (2024)

Third, even if memorization occurs, it reflects incidental retention – an unintended side effect of the training process, not volitional copying (see infra.) – since extracting it demands specific, often unnatural prompting, potentially involving exploitative techniques that may in any event surely violate an AI provider’s Terms of Service, and is entirely unrelated to the training process. Finally, the fact that such extreme efforts are required to coerce (or “torture”) an AI into regurgitating training material verbatim further proves that AI training is fundamentally different from indexing content – such as Google Search –and resembles reverse engineering, a practice also commonly proscribed by companies’ Terms of Service.

There is also the question of “intent” – did you mean to copy – and the separate question of “volition” – did you in fact cause the copy? You can intend to copy yet never do so; conversely, if a copy is made, liability attaches whether or not you meant it.24,25

Courts have thus consistently required volition –but not intent – for direct infringement where automated systems lacked the necessary volitional element: “In the case of a VCR, it seems clear … that the operator of the VCR, the person who actually presses the button to make the recording, supplies the necessary element of volition, not the person who manufactures, maintains, or, if distinct from the operator, owns the machine.” 26

So even if memorization is argued as a necessary step in the training process, copyright law

requires not just that there was an act of copying, but crucially, that there was a volitional act that directly caused that copying, wholly ignoring any concerns about intent.

The point is that when AI developers train their various AI systems’ models, they take no volitional act to cause the models to memorize specific content; any memorization and resulting “regurgitation” of verbatim content is an unintended statistical artifact of the training process, or caused by the end user, and not a volitional copying action.

Simply put, the developers of ChatGPT (etc.) did not, of their own volition, design the product to cause memorization and regurgitation of copyrighted material; on the contrary, it is extremely difficult to produce copyrighted material verbatim. (As of this writing, I cannot prompt ChatGPT, for instance, to create images of Darth Vader. Although the image generation process begins in earnest, it soon aborts with the error message “I’m sorry, but I can’t help with that.”)

For a fantastic discussion on volition, see Lackman, Eleanor M. & Sholder, Scott J. The Role of Volition in Evaluating Direct Copyright Infringement Claims Against Technology Providers, 22 BRIGHT IDEAS (N.Y. State Bar Ass’n) 3 (Winter 2013), https://cdas.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Volition-Article-PDF.pdf

24 Religious Technology Center v. Netcom On-Line Communication Services, Inc., 907 F. Supp 1361 (1995)

26

25 Cartoon Network LP, LLLP v. CSC Holdings, Inc., 536 F.3d 121 (2d Cir. 2008), CoStar Group v. LoopNet, 373 F.3d 544 (2004)