16 minute read

Cambridge – Jayne Ringrose Art Gifts to the Pembroke Shahnameh Centre Firuza Abdullaeva-Melville

Art Gifts to the Pembroke Shahnameh Centre

Firuza Abdullaeva-Melville

Advertisement

This is a sequel to the essay in the 2020 Gazette on the millennium of the death of Abu’lQasim Ferdowsi, author of the legendary Shahnameh. I would like to acknowledge our special gratitude for the very generous gifts, on top of the initial foundation endowment received from Ms Bita Daryabari, which the Pembroke Shahnameh Centre has already received during its relatively short life. These presents which we started to acquire from the very first day of our existence prove that the activities we offer, the vision we have and the direction we are moving towards are in great demand and appreciated by those who care about Persian culture in the West, and especially in the UK. The nature of the gifts shows that it is recognised in the outside world as the Centre where art and culture is valued and promoted at a particularly high level, successfully standing in line with more established Cambridge art institutions in Cambridge.

On the occasion of its first jubilee the Pembroke Centre accepted with much gratitude several generous gifts, which were added to its collection of important Persian artefacts, established on the day of its inauguration on 24 May 2014.

From Ali Javad The Shahriah Shanameh

The Shahriar Shahnameh was offered by Ali Akbar Javad, whose friendship was established in 2014 at Harvard. Ali Javad, a private collector, businessman and screenwriter who migrated to the USA in 1975, resides in Washington D.C. He donated his unique manuscript, which he suggested to the Centre be named the ‘Shahriar Shahnama’ in memory of his late brother Dr Shahriar Javad, who had passed away less than two months earlier.

The manuscript is interesting due to both its artistic characteristics and provenance, which shows that it found its way to America most likely after it was sold at Quaritch in London in 1901. According to the ex librises on its flyleaves, the book was in the possession of several American owners, including Lowell M. Palmer Weicker Sr. (1903–1978), governor of Connecticut and Mrs Elizabeth RobertsonMiller-Weicker-Fondaras, wealthy heiress and famous socialite of New York and Paris (1916–2012), who established academic scholarships in honour of her three husbands. Elizabeth spent quite a long time in France

Fig.1 King Kay Kavus ascending the sky on his flying machine with four eagles used as engine. He is shooting an arrow which is returned to him by angel who covers the arrow with the blood of fish. Shahriar Shahnameh, Iran, early 17th century

with her second husband and became a serious propagandist of French culture in the USA, especially thanks to her most generous annual Bastille Balls that she organised in New York. She was awarded the Legion d’Honneur for her services to France.

This manuscript, lacking its colophon, can nevertheless be dated to the first half of the 17th century, for the characteristic features of its illustrations and calligraphy, which both seem to have been produced at the same time.

It contains 32 miniature paintings, generally in reasonable condition, though often quite abraded and revealing some later retouching. The paintings regularly break out of the text and picture frame, and employ a variety of different stepped formats.

The illustration programme of the manuscript has quite a regular list of episodes, frequently illustrated in other copies of the Shahnameh. There is even a painting depicting the introduction scene –Ferdowsi presenting his poem to Sultan Mahmud in the garden of his palace in Ghazna. However, Rostam’s seventh and most important labour, when he kills the White Demon, is missing.

Perhaps it disappeared before or during the time when the manuscript was rebound; the order of its folia was seriously disturbed and the pages were trimmed to fit the new lacquer binding produced in typical Qajar fashion. Both the outside and inside covers of the papier maché binding are decorated with floral designs and two important scenes from the Shahnama: Rostam kills Sohrab and Rostam kills Isfandiyar. Similarly, the Qajar binding decorated with the battle scenes depicting Rostam killing Isfandiyar and Rostam killing Ashkabus replaced the original one of the manuscripts produced in 1651 for Shah ‘Abbas II (Dorn 333), now in the National Library of Russia, St Petersburg.

There is, however, another mystery: in the Quaritch sale catalogue of 1901 in the entry dedicated to this manuscript it is mentioned that it had 30 miniature paintings. The copy in its current state has 32 pictures and some of them are either missing or misplaced: a few pages bear the traces of pigments from the paintings that were on the opposite pages, which are not there anymore. A more precise conclusion will be made when a more thorough study of the text of the whole manuscript is completed.

Fig. 2 Ex libris of Lowell M. Palmer Weicker Sr. (1903–1978), governor of Connecticut who was one of the owners of the manuscript

Siyavush carpet

For the fifth anniversary of the existence of the centre, Ali Javad presented to the Pembroke Centre a figurative Shahnameh carpet and a portrait of Abbas Mirza.

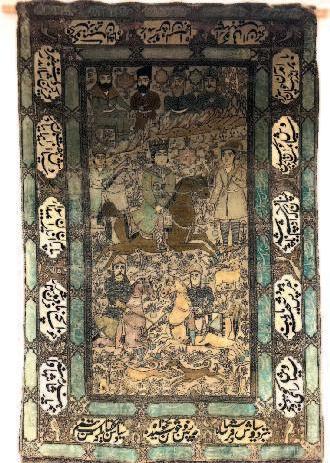

The carpet (136 ¥ 208 cm in size) of Mohtasham-style from Kashan depicts a story from the Shahnameh. It is made of wool and cotton with silk trimming. The carpet was produced at the end of the 19th –beginning of the 20th century. A similar piece was auctioned at the Christie’s sale on 26 April 2018 in London.

The scene describes the Iranian Prince Siyavush playing polo at the court of his Turanian host King Afrasiyab, seated with his jealous Fig 3 Iranian Prince Siyavush playing polo at the brother Garsivaz at the top of the court ofTuranian King Afrasiyab, Muhtashamstyle scene. The text in the surrounding carpet, wool and silk, 136 x 208 cm, Kashan, frame runs clockwise in three bands late 19th early 20th century working outwards from the centre and contains many interesting variations on the standard version of the epic.

Portrait of Abbas Mirza

Abbas Mirza (1789–1833) was the favourite son of Fath Ali Shah (1772–1834), Crown Prince of Qajar dynasty and the Head of the Shah’s Foreign Office. He never became the Shah as he died a year before his father. However, his personal influence on the policy of Persia during one of the most troublesome periods of its history, the so-called Great Game is impossible to overestimate. The first peak of the Great Game period, also called the Tournament of Shadows, fell at the beginning of the 19th century, when after the defeat of Napoleon the world was left only with two superpowers, Great Britain and Russia. Their rivalry was seen most of all in the Middle East, especially Persia, which was considered to be a buffer zone between the growing Russian Empire with the Crimea, the Caucasus and parts of Central Asia, and the British territories in India. The rivalry did not have the features of open military conflict between the two empires but the competition penetrated all spheres of interaction at political, diplomatic, and economic levels.

The portrait is on one hand quite traditional in early Qajar art, when Persian painters started to actively use the techniques of European visual art, namely oil on canvas. The features of the Prince at his early age are rather generic and standard, however, the background and the horizontal layout is quite unusual:

the head and shoulder portrait is put in the middle of the ‘carpet’ ornament surrounding Abbas Mirza dressed in full gear in his princely crown and bejewelled jacket. It seems that a whole series of such portraits was produced: several others were sold recently at a London auction.

Fig. 4 Portrait of Abbas Mirza in his early age, Iran, late 19th century

Fig. 5 Ali Javad presents to Firuza Melville the portrait of Abbas Mirza for the Shahnameh Centre during his visit to Pembroke in September 2019

From the Gharavi family

The Simurgh Shahnameh

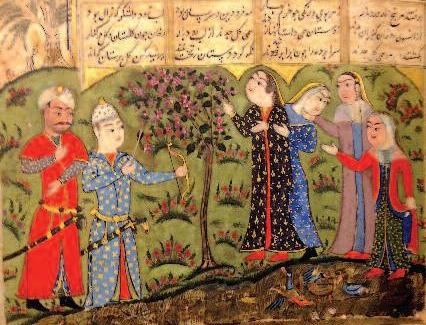

The Pembroke Centre accepted another copy of the Shahnameh on loan from Ameneh, Reza and Sara Gharavi of Toronto and Tehran. The manuscript was called the Simurgh Shahnameh by their late father in whose memory they dedicated their offer. It is originally an early-mid 15th-century manuscript, containing 489 folios and approximately 54,000 verses. The manuscript includes 50 pages of ornamentation and 27 narrative illustrations. The copy is nor signed nor dated but remains a handsome volume, despite the rather heavy overpainting, evidently done in India.

Fig. 6 Princess Rudaba meets knight Zal during the a duck shoot. Simurgh Shahnameh, Iran, earlymid 15th century

Cama Shahnameh

On the kind offer of the same Gharavi family the Centre keeps on loan four folia from the exceptionally precious 14th-century Shahnameh copy, which is known as the Cama manuscript due to its original location in the K.R. Cama Institute in Mumbai. Ameneh Gharavi brought this manuscript from Toronto in memory of her father Dr Mehdi Gharavi, who served as cultural attache in India.

In very poor condition, these pages are the only ones whose whereabouts and existence are currently known. The manuscript is undated but certainly a very early copy of the text and one of a small group of manuscripts almost certainly illustrated in the first decades of the 14th century, probably in Shiraz.

Fig. 7 Execution of knight Faramarz, son of Rostam by Prince Bahman, son of Isfandiyar who was killed by Rostam. Shahnameh by Ferdowsi, Iran, 14th century

From Alexander Ross

A pair of exceptional Khatamkari armchairs are a part of the Centre’s collection, on loan from Alexander Ross in memory of his late mother, Dr Pourandokht Pirayesh, author of the bilingual Perso-German book of translations of the 12thcentury Persian Classics Rose and Nightingale, introduced by Abdul Hussein Zarrinkoub. Alexander was educated in film and business at the universities of Heidelberg, Cambridge, Paris, London and UEA.

The chairs were commissioned by Alexander Ross’s grandfather Hassan Pirayesh from the same artisan who had made a similar set for Reza Shah in around 1938. He believes that the other set remains in the Niavaran Palace. As part of the set there was a desk with the signature of the maker; however, it was sold at auction several years ago. Kh¯atamkari (or khatambandi) is a traditional Persian technique of inlaying. It is a version of marquetry where artefacts are made by decorating the surface of wooden objects with delicate pieces of wood, bone and gilt metal fragments precisely-cut intricate geometric patterns. Designing of inlaid articles is tremendously laborious process. Sometimes to produce a square inch of such ornament a master should produce more than 400 tiny pieces to be put together as an intricate mosaic. The popularity of this technique reached its peak during the Safavid period.

Fig. 8 Kh¯atamkariarmchair, Iran, late 1930s

From Ali Sarikhani

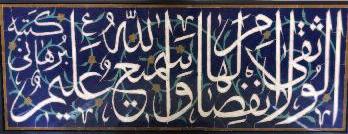

The Centre’s collection includes Qur’anic verse in polychrome tile (kashikari) technique donated by Ali Sarikhani. The large panel of tiles comprising the second part of the verse No 256 from the Second Su-rah Al-Baqara (The Cow): ‘Let there be no compulsion in religion: Truth stands out clear from Error: whoever rejects evil and believes in Allah hath grasped the most trustworthy hand-hold, that never breaks. And Allah heareth and knoweth all things’. The panel was commissioned from master craftsmen from Isfahan as part of the set of tiles to decorate the entrance of the Sarikhani Museum of Persian and Islamic art.

From Veronica Shimanovskaya

The Pembroke Shahnameh Centre possesses several art works by Veronica Shimanovskaya, curator of most of the Centre’s exhibitions. She is a St Petersburg born international artist, and independent curator, educated at Harvard and University of East London (PhD), currently based in San Francisco Bay Area, where she is a founder and a CEO of Ephemereye, a digital platform that supports video art and artists.

Painting of Princess Manizheh

Shimanovskaya in her monumental painting offers her interpretation of the story of the Turanian Princess Manizheh who fell in love with the Iranian knight Bizhan and sacrificed everything for the sake of her love.

Her version deeply contrasts with the traditional depiction of one of the crucial episodes of the Persian Romeo and Juliet story: when Bizhan was exposed in Manizheh’s chambers and was incarcerated in a pit. In many cases he is the only one who is depicted as suffering from separation from his beloved and sitting in inhuman conditions. In Shimanovskya’s rather feminist painting it is the reverse: we can see only Manizheh, who came to visit her beloved Bizhan. In fact the spectator is presented as Bizhan, sitting in the pit, punished and suffering but invisible. Bringing Manizheh into spotlight and hiding Bizhan, Shimanovskaya restores the justice of the real protagonist of the ancient story. For centuries her role of a Princess who was capable of sacrificing comfort and wealth for her love was completely ignored. The main focus was always on Bizhan and sometimes his rescuer, Rostam, who were recognised as the main heroes of the story.

Sculpture of King Zahhak

Shimanovskaya’s interpretation of Zahhak shifts the attention of the narrative from human empathy — of which king Zahhak was incapable after Ahriman implicated him in his scheme of self indulgence, avarice, and gluttony — to the concept of love, of which Zahhak became

Fig. 10 Princess Manizheh by Veronica Shimanovskaya, oil on canvas, London, 2014 Fig 11 King Zahhak tormented by his snakes by Veronica Shimanovskaya, bronze, London, 2015.

incapable and unable to give to his wives when two serpents sprung up from his shoulders. Veronica’s sense of irony guided her decision to turn the serpents into Zahhak’s arms and rendered him unable to hug anyone or even comfort himself, as he had nothing with which to do so but two vicious snakes.

From Sergey Feofanov

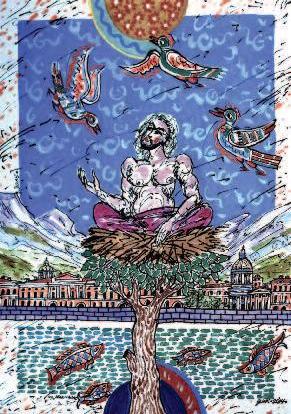

Sergey Feofanov (b. 1950), a renowned painter, ceramist, animator and theatre and stage designer, Member of the Russian Fine Arts Academy and the National Artists Society, has been invited to design performances in various theatres in Russia, Germany, Georgia, Japan and India.

Feofanov has donated to the Centre two ceramic versions of his Simurghs, a mythical bird that is the eternal patron of the main legendary Iranian hero Rostam. Feofanov presented one for the inauguration of the Centre and the second for its third anniversary. Both chamottes were a part of his Simurgh series, which were presented at his blockbuster personal exhibition in the Russian Fine Arts Academy in Moscow. His large in size ‘Ferdowsi flying on the Simurgh’ has much in common with the monument to the poet produced by Abo’l-Hasan Seddighi and Hasan-Ali Vaziri in 1933. The sculpture was lost; however, Feofanov miraculously managed to recreate the original idea, having never seen SeddighiVaziri’s Ferdowsi riding the Simurgh. What is even more notable is that Feofanov’s source of inspiration was mainly the 14th-century star-shaped tiles excavated in the historical site of the Tahkt-e Sulayman in northern Iran, which has been perceived as the melting pot of various cultural and artistic traditions which were represented in the archaeological complex dating from the preIslamic past until the Mongol invasion.

Figs. 12 and 13 ‘Ferdowsi flying on the Simurgh’ by Sergey Feofanov, chamotte and gold, Moscow, 2014

From Vyacheslav Zabelin (VIK)

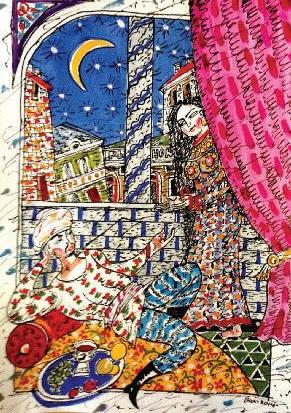

Three graphic art works have been given to our Centre in the memory of Vyacheslav Zabelin (29 October 1953 – 16 February 2016) (‘VIK’) by his widow Olga Zabelina .

VIK was a non-conformist artist and poet. He was born in Mongolia and educated in Leningrad in Serov Art College. For many years he was working as a conservator in the Peterhoff Museum, and stage designer in the Alexander Theatre and the Demeni Puppet Theatre. From the early 1970s he became an active member of the Leningrad group of non-conformist artists.

All three pieces of his Shahnameh series has a strong Petersburg flavour. He illustrated three episodes: ‘Rostam and Tahmina’, ‘Zal and Rudaba’ and ‘Zal in the Simurgh’s nest’. All of them combine the traditional iconography of medieval manuscript illustration of these famous episodes with Petersburg’s specific architectural features, like the Neva embankment, or St Isaac’s Cathedral – all depicted in his strikingly recognisable manner.

Worthy of special note is his interpretation of the visit of the Turanian Princess Tahmineh to the Iranian knight Rostam in his bedchamber during the night, offering herself to become the mother of his child during his stay in her castle. In so far as VIK read the episode in Russian translation from Tajik, his interpretation of the ancient story was influenced by his perception of the Tajik labour migrants in St Petersburg who are involved mainly in the market trade. Thus his Rostam and Tahmineh are not medieval Persian aristocrats but local grocers in a big European city.

Fig. 14 Zal in the Simurgh’s nest by Fig. 15 Rostam and Tahmineh by Vyacheslav Zabelin, pencil, and watercolour Vyacheslav Zabelin, pencil and watercolour on paper, St Petersburg, 2015 on paper, St Petersburg, 2015

From Irina Volkodaeva

Professor Irina Volkodaeva is the Head of Department of Design of Urban environment at the University of Design in Moscow. She presented this Manizheh porcelain doll to the Centre after the exhibition of her series of historical reconstructions of various epochs and nations. When Volkodaeva decided to create her version of Manizheh, she chose to present a young lady in the costume of the early Qajar period with which she became familiar through the masterpieces of Qajar art, especially portraits of harem ladies in the collections of the Oriental Museum in Moscow and the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg.

From Hamid-Reza Ghelichkhani

Dr Hamid-Reza Ghelichkhani is a one of the most prominent Iranian calligraphers of our times who is not only a practitioner but also a well-known specialist in Persian and Perso-Indian literature and calligraphy. Dr Ghelichkhani produced his calligraphic pieces when he was staying at Cambridge as a visiting scholar during Michaelmas 2013 being attached to the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, where he was also conducting Persian calligraphy workshops.

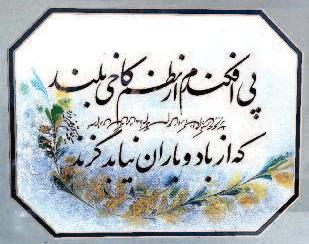

His calligraphies presented to our Centre contain excerpts from the Shahnameh. One of them reproduces a double verse (bayt) from the finale of the poem, which many contemporary Iranians perceive as the motto of its author and the essence of his whole magnum opus:

I have constructed a palace out of my verse

That will never be destroyed by the wind or rain

I shall not die – these seeds I’ve sown will save [My name and reputation from the grave] (dedicated to Dr Firuza Melville)

Fig. 16 Manizheh by Irina Volkodaeva, porcelain, fabric, turquoise beads, Moscow, 2016