26 minute read

‘A Small College Man’: George Gabriel Stokes and Pembroke College

A ‘Small-College Man’: George Gabriel Stokes and Pembroke College, Cambridge

Jayne Ringrose

Advertisement

This paper was originally delivered at the Stokes 200 Conference at Pembroke College on 17 September 2019. I should like to thank the organizers of the conference, Professor Silvana Cardoso and Professor Julyan Cartwright, and especially Dr Christopher Ness, Fellow of Pembroke College, for help with preparing the original presentation. Mr Matthew Mellor, Fellows’ Steward at the College kindly gave permission for me to quote from the Parlour wine books. I am grateful to the Master and Fellows of Pembroke College Cambridge for permission to cite and quote from the College Archives, and to my successor as College Archivist, Mrs Elizabeth Ennion-Smith and to the College Librarian, Ms Genny Grim for facilitating this and for much other help. I am likewise grateful to the Syndics of Cambridge University Library and to the Superintendent of the Manuscripts Reading Room, Mr Frank Bowles and his staff for much assistance. Finally I owe a debt of gratitude to Dr Mark McCartney, Dr Elisabeth Leedham-Green, Professor David B. Wilson and Mrs Julia Wilson, and the Reverend Margaret Widdess.

Introduction

According to the Cambridge University Calendar (1837, 193–197), when George Gabriel Stokes first came up to Pembroke College, there were 40 undergraduates, plus two sizars,1 in addition to the Master, Gilbert Ainslie, and 12 Fellows (there were two vacancies and two Bye-fellows),2 while according to the University Calendar of 1902–03 (708–720), there were 13 foundation fellowships but over 240 undergraduates.

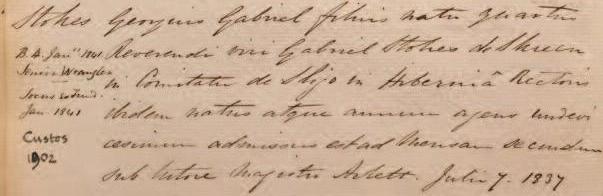

Stokes became a member of Pembroke on 7 July 1837, when his name appears in the admissions book (in Latin) as follows:3

Stokes, George Gabriel, fourth son of the Reverend Gabriel Stokes, Rector of Skreen in county Sligo in Ireland, born there, and having reached his nineteenth year [i.e. aged eighteen], was admitted to the second [undergraduate] table under the Tutor, Mr Arlett, 7 July 1837

His contemporary John Power, reforming and modernising Master from 1870–80, had been admitted less than a month earlier. There were eighteen entrants in all that year. This article traces Stokes’s occasionally chequered connection with Pembroke College from his Admission to his death in the Mastership in 1903.

What did Stokes see at Pembroke when he got off the coach which had brought him from Birmingham en route from Bristol?4 Not what the modern fresher sees today. The fourteenth-century gateway opened into a tiny enclosed medieval court, one of the smallest in the University, the site formed of the two original strips of land given by the Foundress to her College in the fourteenth century.5

On the right, the south side, was a medieval range which included the old Master’s Lodge, its eighteenth century extensions stretching beyond the present range towards the Chapel. Straight ahead was the College Hall, smaller than the one we know today, and again dating back to the fourteenth century. Both Hall and south range were to disappear during Stokes’s time at Pembroke. Of the Old Court, only the north range, with the College Library, (now the Old Library) some sets of rooms and the buttery were to remain.

The second court, approached through the screens between the Hall and the kitchen, was originally known as New Court, now Ivy Court. Beyond it lay the Orchard, with Ridley’s Walk, traditionally associated with the Protestant Martyr and Master Nicholas Ridley and leading to an historic tennis court, to the bowling green, and, to the north east of New Court, the Sphere. This was a planetarium built by the Master Roger Long (held office 1733–70), famed for his eccentricities such as the water velocipede upon which he rode round the pond in his garden. The stars were represented by holes in the metal of the Sphere, which was turned by a handle, originally operated by his servant Richard Dunthorne, and the interior seated thirty spectators.

Stokes the undergraduate

Stokes’s Tutor was Henry Arlett, who in 1837 was combining the Office of Tutor with that of Treasurer and President (that is, Vice-Master). He was to influence Stokes’s life and career almost up to his death in 1869. Stokes quickly established himself academically. The College held an internal examination every summer. As is well known, Stokes was beaten in his first year by John Sykes, a future Fellow and civil servant who obtained 325 marks in classics (well below Stokes’s 377) but 524 in maths while Stokes only managed 481. Stokes soon recovered however, and in his third year in 1840, obtained 1,421 marks in Mathematics and the Greek Testament. Sykes got 986 and Power 715.

Meanwhile, he was mopping up scholarships, which could be held at Pembroke in plurality. Stokes held a foundation scholarship from 1838 to the end of his third year. He also collected for example in his third year a Senior Greek scholarship (Power only got a junior Greek) and an Ipswich Scholarship.6 Like other students, Stokes dined daily in Hall, the scholars sitting at the same table as the rest of the students. Chapel was compulsory twice on Sundays at 9.30 am and 6.00 pm;7 it was compulsory once on other days at 7 am or 6.00 pm. Gilbert

Ainslie, Master 1828–70 was Vice Chancellor in 1836–37 and laid the foundation stone of the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1837. Stokes would have seen the building going up in his undergraduate years and later.

Stokes passed the previous examination (in his day a compulsory examination for all students on one of the gospels in Greek, a Greek and a Latin classical text and Paley’s Evidences of Christianity). This was held in the fifth term with the chance of a re-take the following October; it was geared mainly to pass men, that is, those aiming no higher than ordinary degrees.

The final major hurdle was the Tripos or Senate House examination, taken in January, often in freezing conditions. The American Charles Astor Bristed, who came up to Trinity in 1840, could not bring himself to notice the Senior Wrangler of 1841 as anything other than a ‘Small-College man’, though he conceded that such a triumph was an unusual occurrence, and remarked that the mathematical examination that year was very difficult and played havoc with candidates’ expectations.

First election to a Fellowship

Stokes was immediately elected to his Fellowship on 23 January, and was admitted to this in the Chapel. He dined for the last time at the second table on the fifth week of the Lent Quarter 1841, and for the first time at the Fellows’ table, on the sixth week of the Lent Quarter. But where exactly was Stokes’s room? By the time intelligible records of rooms begin in 1870, Stokes had long moved out of College into Lensfield Cottage backing on to the site of the modern Scott Polar Research Institute in Lensfield Road. College tradition asserts that as a young don he occupied the high gabled room with gothic windows, which now overlooks Trumpington Street on the outside and, it was said, fitted it up as a physics laboratory. This room is medieval in origin and may be the ‘magna camera’ or ‘big chamber’ which is mentioned in the earliest College property records.8 Until the late nineteenth century it formed the extreme end of the subsequently demolished south range, and it is just possible that other rooms were associated with it.

For Stokes, these were the years of the entries in the parlour wine books which record bottles of wine presented in settlement of bets, or as forfeits for misdemeanours. Unlike the case with modern wine books, the nature of the misdemeanour is described but there is no account of exactly who was there. Thus, on 30 October 1847, Mr Stokes bets Mr Power that Pratt of Caius was second Wrangler. (John Henry Pratt afterwards Archdeacon of Calcutta and a physicist, was third Wrangler in 1833.) On 2 November, Mr Stokes paid a bottle on being appointed moderator (Senior examiner). On 14 May 1848, Mr Stokes is fined a bottle of wine for spilling Mr Sykes’s claret. On 13 June 1848, Mr Stokes broke a wine glass; on 7 November 1848, Mr Stokes is fined a bottle of wine for tearing The Times.

Meanwhile, Stokes served as Praelector in 1845, presenting students for degrees in the Senate House, and was Bursar (assistant Treasurer) in 1846 and 1847. This would suggest involvement with the celebrations for the five hundredth anniversary of the founding of the College in 1847. In 1849 he of

course became Lucasian Professor of Mathematics. And yet the College, described by one former undergraduate as a ‘Caravansera of idlesse’9 seemed to be declining, especially in numbers, reaching its nadir (during Stokes’s absence from the Fellowship) when Edward London Pincott came on 18 October 1858, only to leave the College and go to Caius after keeping five days of residence, the only entrant of his year.

Marriage and the University Commission of 1850

As is well known, Stokes forfeited his Fellowship upon his marriage. As various dates have been given for this, it should be noted that the marriage took place on 4 July 1857. The Master Gilbert Ainslie, preoccupied with the University of Cambridge Act of 1856 wrote from Hall Garth in Lancashire: on 6 October 1856: ‘My dear Stokes, Altho’ I cannot say that I am sorry that you should have determined to lead a married rather than a single life, I am truly sorry to think that you will have ceased to be a Fellow of my College’. He went on: ‘I think you happy in escaping some of the changes which the new Act will bring upon us’.10 Henry Arlett, Stokes’s former Tutor wrote on 18 November: ‘We hope you have chosen the better part and will be as happy as you deserve to be but the Old House can ill afford to lose you and there is a general wish that it were possible to keep you one of us still. At present I am sorry to say no progress has been made towards a Statute to enable a married Professor to retain his Fellowship and if it ever pass it will be in the teeth of considerable opposition only by a compulsory enactment of the Commissioners’.11

Why, therefore, given Stokes’s evident popularity with the Fellows of Pembroke did it happen that, after the College received new statutes in 1861 allowing married Professors to retain their Fellowships in certain circumstances, was it a further full six years before Stokes was re-elected to his Fellowship on 22May 1867?

It is not possible to say for certain, but there may be a clue in Stokes’s involvement with University Reform. Right up until the middle of the nineteenth century, the University of Cambridge had still been running largely on the Elizabethan statutes of 1570. Privileges were entrenched and there was little possibility of change to meet modern requirements, most notably the growth of the under-endowed University as distinct from the wealthy Colleges. A Royal Commission (‘the Graham Commission’; see note 7 above) was appointed in 1850 to inquire into the two ancient universities. The Commission’s report resulted in the Cambridge University Act of 1856. For the purposes of this article, the main thing is that the Act set up Statutory Commissioners, to oversee the revision of the statutes of the University and Colleges. The Act permitted the Colleges to reform their own statutes. For the most part, they did not do so, and the Commissioners accordingly exercised their power to frame statutes for the Colleges. This, it may be imagined caused enormous disagreement and rancour amongst the Colleges (and indeed the University reformers). Stokes, needing to supplement his meagre income from the Lucasian Professorship, became an assistant secretary to the Commissioners in 1859, and found himself facing the

opposition of the Fellows of his own College. The last straw was the proposal that the College should contribute a part of its revenue to the funding of the University. In their reply to the Commissioners of 14 December 1859 addressed to ‘G. G. Stokes Esq’ by name, as Secretary to the Cambridge University Commissioners, and indeed signed by Henry Arlett, now the President (Ainslie the Master having withdrawn altogether), the Fellows made it clear that they could hardly be expected to consent to this innovatory proposal, which they regarded, like the Commission itself, with deep suspicion.12

Re-election to a Fellowship

The statutes which the College eventually received in 1861 dipped a toe, so to speak, in the waters of a married Fellowship. Henceforth up to two married Fellows could be elected, either Professors in the University on an income of less than £80 a year, or else men distinguished in learning or science. Thus John Couch Adams was able to marry in 1863 and retain his Fellowship. The College records are silent as to why Stokes was not re-elected to his Fellowship at the first opportunity, The actual date of his re-election was 22 May 1867. This date should be noted carefully. So many sources, including Stokes’s Times obituary and his entry in the Encyclopaedia Britannica say that it happened in 1869.13

Stokes was elected together with Mr Lambert (third wrangler the same year)14 and they were forthwith admitted in the Chapel. The ten Fellows who signed the register included men like John Power and Charles Searle who were to change the face of the College. Stokes, who attended College meetings assiduously, was to give them quiet support. It looks like a pivotal moment. Stokes may have felt this himself: we find him giving a bottle in Parlour on 23 March 1868, in honour of the birth of a daughter,15 exactly ten months after his re-election, which he learned in response to subsequent enquiry was as a man distinguished in science rather than as an under-remunerated Professor.

Ainslie died in 1870. His successor as Master –and Stokes’s friend and contemporary –John Power was a man with a plan. He and Searle set to work rapidly to revive the College, at the same time appointing Stokes as President (the equivalent of Vice-Master) in 1874.

The College is transformed

The remainder of the century saw a total transformation of Pembroke in terms of buildings and numbers. For what follows, I summarize from the excellent account by Pembroke’s architectural historian, the late Peter Meadows.16 Alfred Waterhouse was appointed as architect, and planned the entire rebuilding of the College. The red buildings on Trumpington Street were the first to go up in 1871–72, providing three staircases of accommodation.

Then, significantly for further developments, a new Master’s Lodge was built for Power in 1873. A new Lodge meant freedom to demolish the old Lodge, a predominantly 18th century building connected with the medieval south range, which was removed too, leaving the vista which we now see from within the College Gate across to the Chapel. This left the old Hall with its two stories above,

standing rather forlorn, and Waterhouse was eager to pull it down. This the Fellows consented to in 1875, provoking a storm of controversy in the Press and by letter, in which Stokes’s friend, Edmund Venables, now Precentor of Lincoln Cathedral took a leading part albeit unsuccessfully. Waterhouse’s Hall, the one which eventually provided a backdrop for Stokes’ Jubilee celebrations, was a single story building, with a rather gaunt interior. Beyond it was the Combination Room, which was to be opened out in the next century as the present High Table area with its (currently) three long tables.

Meanwhile Waterhouse swept on, designing a new Library in 1877–1878. The destruction of the Old Library, which the Fellows voted to approve in 1878 was prevented only by the Fellows’ replacing Waterhouse with George Gilbert Scott, Jr to re-consider the Trumpington Street frontage (now more or less what we see today), the Old Library (which he preserved as a matter of conscience) and the Chapel which he extended very sympathetically to take the increased numbers of undergraduates. Pembroke also owes New Court (1881) to him.

These buildings are the best evidence we have of the College’s expansion as numbers of undergraduates increased, mostly from the public schools and many of them pass-men taking ordinary degrees.

Elder statesman in College and University

The expansion of Pembroke coincided with the second Royal Commission on the Universities set up in 1872. The resulting Universities of Oxford and Cambridge Act of 1877, like the earlier one, created Statutory Commissioners to make statutes for the University and Colleges. This time, Stokes, once a lowly assistant secretary to the earlier Commissioners, was one of the seven Statutory Commissioners named in the Act, alongside others among the Great and the Good, such as the Lord Chief Justice, also Professor J. B. Lightfoot, soon to be the toweringly great Bishop of Durham and Lord Rayleigh. In their work, the origins of the twentieth century University can be perceived.

At the same time, Stokes was playing his part as a Fellow of Pembroke, taking part in the meetings which led to the drawing up of the new College statutes granted in 1881. Sadly he was not elected Master in 1880, to Lord Kelvin’s17 regret. He remained President, deputising for Searle, the Master as required. Stokes himself was a trustee of the College Mission and was involved in the appointment of Charles Freer Andrews (better known afterwards as a friend and colleague of Gandhi) as missioner in Walworth.18 Again, we find him at a College meeting on Saturday 19 October 1897 joining with other Fellows in attempting to persuade the Master Dr Searle, already seriously depressed, not to resign over the playing of Sunday Golf at the North Surrey Golf Club on a College Estate at Norbury.19 As late as a College meeting on 10 October 1900 Stokes, with others, was asked to consider and report on ‘the introduction of the electric light’ in the Chapel and in the Hall. They were still discussing it in July 1902.20

In January 1894 the Dean, James Bethune-Baker wrote enclosing the Chapel card, and adding ‘I should be so glad if you could possibly give us three or four short addresses next term on some of the subjects in which you can speak as no

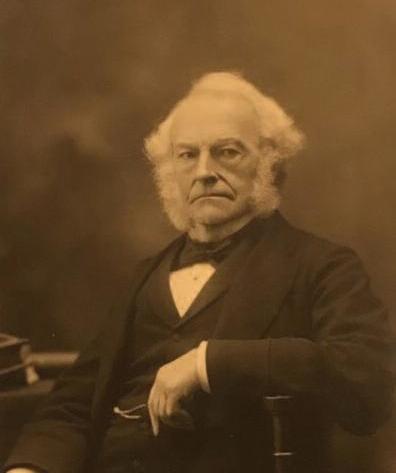

one else can; for example a few points of the relationship between Christianity and Physical Science’.21 Stokes was already known to some of the undergraduates as ‘The angel Gabriel’ as with majestic countenance he read the lesson in chapel on Sunday evenings.22 The letter sent by the Fellows to the sculptor Hamo Thorneycroft on 6 February 1897 asking him if he would undertake a bust of Stokes referred to the latter’s ‘finely chiselled features’.23

Jubilee as Lucasian Professor

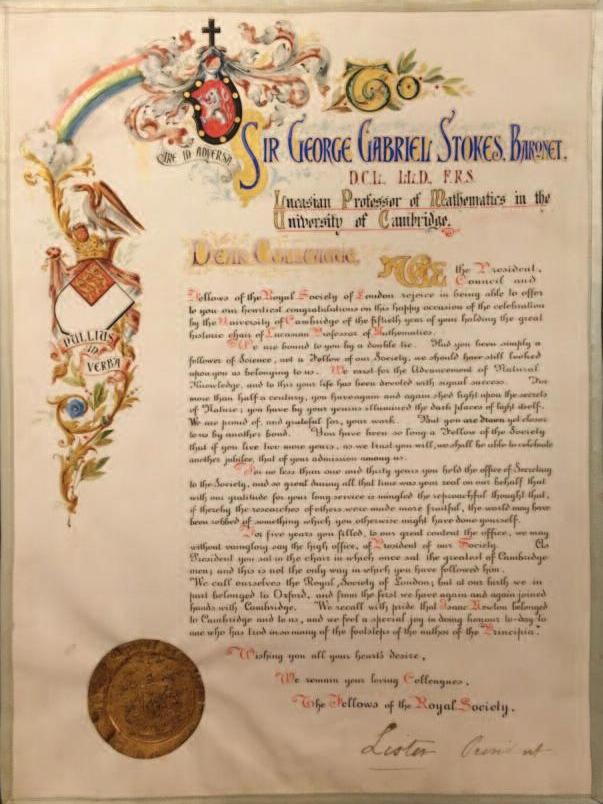

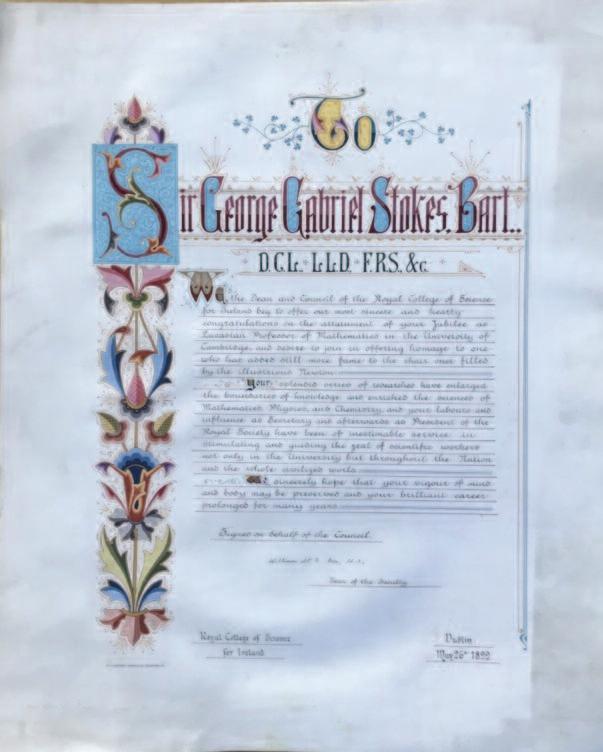

The bust and its copy were presented to Pembroke College and to the University at the reception held in the Fitzwilliam Museum on the evening of the first day of Stokes’s Golden Jubilee as Lucasian Professor, on Thursday 1 June 1899, attended by a thousand people at which Lord Kelvin spoke.24

On the following day came the morning congregation at the Senate House, with the presentation of the addresses. Stokes together with The Vice-Chancellor, The Master of Downing, sat side by side on the dais. The Registrary read out the names of the Universities and other bodies, and of their representatives. These handed their addresses to the Vice-Chancellor who handed them to Stokes. Lord Lister, the President of the Royal Society lost his glasses, and according to the Cambridge Review ‘The floor of the Senate House was bright with coloured gowns

and uniforms and the whole scene was dignified, impressive and worthy of the occasion’. There was scarcely time for the luncheon for 400 at Downing.

The second session in the Senate House during the afternoon saw the presentation of the gold medal of the University of Cambridge and the conferment of honorary degrees. Later on there was a garden party at Pembroke, where the band was good and the ices superb, and the Medals and addresses were displayed in the Hall. The final dinner that evening in the Hall of Trinity began very late. In one of the speeches, the Master of Trinity, Henry Montagu Butler revealed that the reason that Stokes was never at Trinity was that he had been refused admission by the then Master, the formidable Dr Wordsworth, the brother of the poet, who was accordingly described as ‘A man of a thousand virtues and one crime, in spite of which he strangely died in his bed’.

Mastership and death

Dr Searle, the Master, who had been in an invalid chair throughout the Jubilee proceedings, died in July 1902. On the day of the funeral, 1 August, the Fellows drafted a letter inviting Stokes to be ‘a Candidate for the Mastership’. They wrote: ‘We desire that the College should have the distinction of having your name as Master associated with it and we feel that it is in the best interests of the College that you should undertake the duties of the Office’.25 They offered to grant exemption from residence in the Lodge and even hinted at a future building scheme which might include a new Master’s Lodge.

So on 12 August 1902 Stokes became Master for the last six months of his life, during which time he was in increasingly poor health. He lived with his daughter Isabella and her husband Dr Laurence Humphry in their house ‘Lensfield’, roughly on the site of the steps of the present chemistry laboratories. There he was to die on 1 February 1903.

The coffin rested in the College Chapel of Pembroke on the night before the funeral. On the following day, Thursday 5 February, it was carried round three sides of the court, as is customary for a Master, accompanied by the hymns ‘On the resurrection morning’ and ‘O God our help in ages past’, to the College gate, whence it was taken up to Great St Mary’s Church. Various University and other

dignitaries had assembled in the Senate House to join the procession. The Dean of Pembroke, Bethune-Baker, officiated according to the Book of Common Prayer, together with Stokes’s Vicar from St Paul’s, the Revd H P Stokes. The Bishop of Exeter, Dr H E Ryle, soon to be translated to the See of Winchester, also took part. At the end, to the singing of Bishop Walsham How’s great hymn “For all the Saints” a procession formed up with carriages and followers on foot to go from Great St Mary’s to the Parish burial Ground of St Paul’s Church in the Mill Road cemetery.26

Let it never be said that the College has no monument to him. The central light of the East window of the Chapel depicting the Crucifixion flanked by the Foundress, Marie de St Pol Countess of Pembroke, and Bishop Matthew Wren, donor of the Chapel. was given in his memory by his daughter Isabella, in 1906. It was designed by her brother-in-law, G W Humphry. The College also added the two lights, one on either side, depicting Pembroke benefactors. There is an inscription below and to the left of the Foundress largely hidden by the pediment above the altarpiece: ‘In piam memoriam Georgii Gabriel Stokes posuit filia’ (His daughter placed this in pious memory of George Gabriel Stokes). 27

1 A sizar was originally a poor student who performed menial services in the College, such as waiting at table, in return for reduced fees. There was no stigma attached to this. By Stokes’s day this had become a kind of minor scholarship or exhibition. 2 A Bye-Fellowship was a kind of Minor Fellowship, with a fixed salary, not on the Foundation. Such might be compared with senior research studentships today; residence was not required. 3 Pembroke College Archives College MS E beta Page 104 ‘Stokes, Georgii Gabriel filius natu quartus Reverendi viri Gabriel Stokes de Skreen in comitatu de Sligo in Hibernia Rectoris ibidem natus atque annum agens undevicesimum admissus est ad mensam secundam sub tutore Magistri Arlett Julii 7 1837’. Marginal annotations record his graduation as BA and Senior Wrangler and election to a foundation Fellowship in January 1841 and to the Mastership in 1902. 4 The information about Stokes’s journey to Cambridge and many other details comes from the unpublished biographical Memoir of George Gabriel Stokes by Henry Paine Stokes (no relation), Vicar of Stokes’s Parish Church, St Paul’s Church Cambridge, Cambridge University Library MS Add 8699. 5/1. 5 Marie de St Pol, Countess of Pembroke. The original foundation Charter is dated Christmas Eve 1347. 6 Scholarships, like examination results, were recorded in the examination book, and also in the College register, under the respective years. By this period, the historic names of the scholarships were not held to be of great significance. The College Register, Pembroke College Archives, College Manuscript B Beta 7–9 records in the second part (Beta 8) on p156 the election on Tuesday 13 June 1838 of Stokes to a foundation scholarship at the end of his first year, which he retained for the rest of his undergraduate career; p 169 records his election on 29 May 1839 to a Parkin and Bowes scholarship in his second year; College MS B epsilon 1 (College Register vol 10), records on p 12 Stokes’s election to a Watts senior Scholarship for Greek and an Ipswich Scholarship on 9 June 1840. Stokes’s Greek was exemplary, but he would not have fulfilled the schooling qualifications for the Parkin and Bowes or the Ipswich scholarships had they been required. 7 This information comes from the account of the College supplied to the Graham Commissioners by the Master, Gilbert Ainslie in Report of the Commissioners appointed to

enquire into the State, Discipline, Studies, and Revenues of the University and Colleges of Cambridge; together with the Evidence…, (Parliamentary papers, 1852–53) HC xliv [1559]: evidence, separately paginated from the Report, 319, 323; it was known as the Graham Commission after its Chairman, John Graham, Bishop of Chester. 8 The room with its pointed gable appears in the centre of the Trumpington Street street frontage in every illustration of the exterior of the College. The suggestion that the room was the magna camera was made by Sir Ellis Minns, President of the College (and archivist) in an article ‘The yearly rose’, Pembroke College Cambridge Annual Gazette 26 (1952),13–15. 9 See Thompson, Wayside Thoughts, Being a Series of Desultory Essays on Education (1868), 94–99: ‘I still had the mathematical lecture-room to fall back on. I had but to strike the rock in faith and streams of science would well out. I went to a garret in the further quadrangle, The ceiling sloped very uncomfortably down to the ground, some panes in the window were broken and a dismal fire gave out a little smoky warmth … After lectures we would breakfast; some few of us would do an hour or two’s reading. At noon there would be a meeting for luncheon, and we would enjoy a tankard of good ale and a few comfortable pipes; we would then take a long constitutional or play at cricket or row upon the narrow winding river; we would dine at four; retire to a singular mélange of pipes, fruit and premature port wine, the chapel bell would summon us at six; after chapel we would retire to billiards and return to a pleasant whist party at ten, where sandwiches and illimitable stores of ale and pipes would keep us in good humour until very early hours’. 10 Gilbert Ainslie to Stokes, 6 October 1856 (Cambridge University Library MS Add 7656, A 242). 11 Henry Arlett to Stokes 18 November ?1867 (Cambridge University Library MS Add 7656, A 803). 12 Pembroke College Archives, papers relating to statutes and the Royal Commission, Reply of the Fellows of Pembroke College Cambridge to the remarks of the Commissioners, page 3: under Chapter 4 of the proposed new statutes ‘Payment for University purposes’ they wrote ‘The statute proposed by the Commissioners under this head is one of such great importance that the Fellows respectfully submit that they can hardly be expected to consent to its enactment till its intention and probable effect are better understood’. This was surely putting it mildly. 13 The Times 2 February 1903 p 7; Encyclopaedia Britannica 11th ed (New York 1910–11) Vol 25 p 951 Stokes, Sir George Gabriel, describes it as twelve years after his marriage of 1857. 14 Carlton John Lambert, third Wrangler 1867, afterwards Professor of Mathematics at the Royal Naval College Greenwich. 15 This was Dora Susanna, who sadly died in infancy. 16 See Grimstone, Pembroke College Cambridge: A Celebration (Cambridge: Pembroke College, 1997), ch 6. 17 ‘I am very sorry you are not Master of Pembroke. … I felt sure that you would be elected and hoped much that you would consent to accept the office’. Kelvin to Stokes, 28 November 1880 in David B. Wilson, The Correspondence between Sir George Gabriel Stokes and Sir William Thomson, Baron Kelvin of Largs vol. 2 1870–1901 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990, 514). Searle succeeded Power as Master, and accordingly continued the College’s policy of expansion in numbers. 18 Searle to Stokes, 6 March (probably) 1896 Cambridge University Library MS Add 7656, S323. The year is not given but Andrews arrived in Walworth in April 1896. 19 Pembroke College Archives, Notes relating to College meetings, 1896–1904 (unpaginated). 20 ibid.

21 Bethune-Baker to Stokes, 18 January 1894; Cambridge University Library MS Add 7656, B 345. 22 Stokes was ‘a man whose personal faith so shone forth that the undergraduates called him, and not in mockery “the Angel Gabriel”’: Benarsidas Chaturvedi and Marjorie Sykes, Charles Freer Andrews: A Narrative (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1949, 15). 23 The correspondence with Thorneycroft is preserved in the College Archives with other material relating to works of art in College. 24 For what follows see the unsigned account “News of the week and notes” Cambridge Review 20, 7 June 1899, 382–383; also Cambridge University Reporter 29 no 40 (1898–99), 6June 1899, 1016–22. College Treasury accounts record that the total cost to the College of the proceedings came to £206 15s 6d; the cost of hiring the Band of the Royal Artillery came to £28 15s 0d, tents, etc. from Messrs Eaden Lilley came to £12 19s 0d and a mysterious £3 was spent on police.(Pembroke College Archives, College MS M alpha 11 Treasury Accounts vol 11, 1889–1910, unpaginated). 25 The letter with related material is preserved in Pembroke College Archives, Notes relating to College meetings, 1896–1904 (unpaginated). 26 The Order of service is preserved in the papers of H P Stokes, Vicar of St Paul’s Church Cambridge University Library MS Add 8699. 4/1/1. These papers as a whole, which I have consulted extensively, include a detailed memoir of Stokes, his scientific achievements, and his religious and ethical views. The funeral was also reported in detail on the Cambridge Daily News 6 February 1903. This is reproduced on the website of the Cambridge Mill Road Cemetery (http://millroadcemetery.org.uk/mrc2015/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Stokesfuneral_report.pdf and http://millroadcemetery.org.uk/stokes-george-gabriel/). The correct date of the burial is 5 February. The hymn ‘For All the Saints’, not mentioned in the Daily News report, would most likely have been sung to the tune ‘Sarum’ by Sir Joseph Barnby. Vaughan Williams’s better known ‘Sine Nomine’, written for the English Hymnal was not published until 1906. 27 A fitting inscription: Isabella contributed a memoir of her father to the first volume of J.Larmor (ed) Memoir and Scientific Correspondence of George Gabriel Stokes, 2 volumes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1907).