From

10

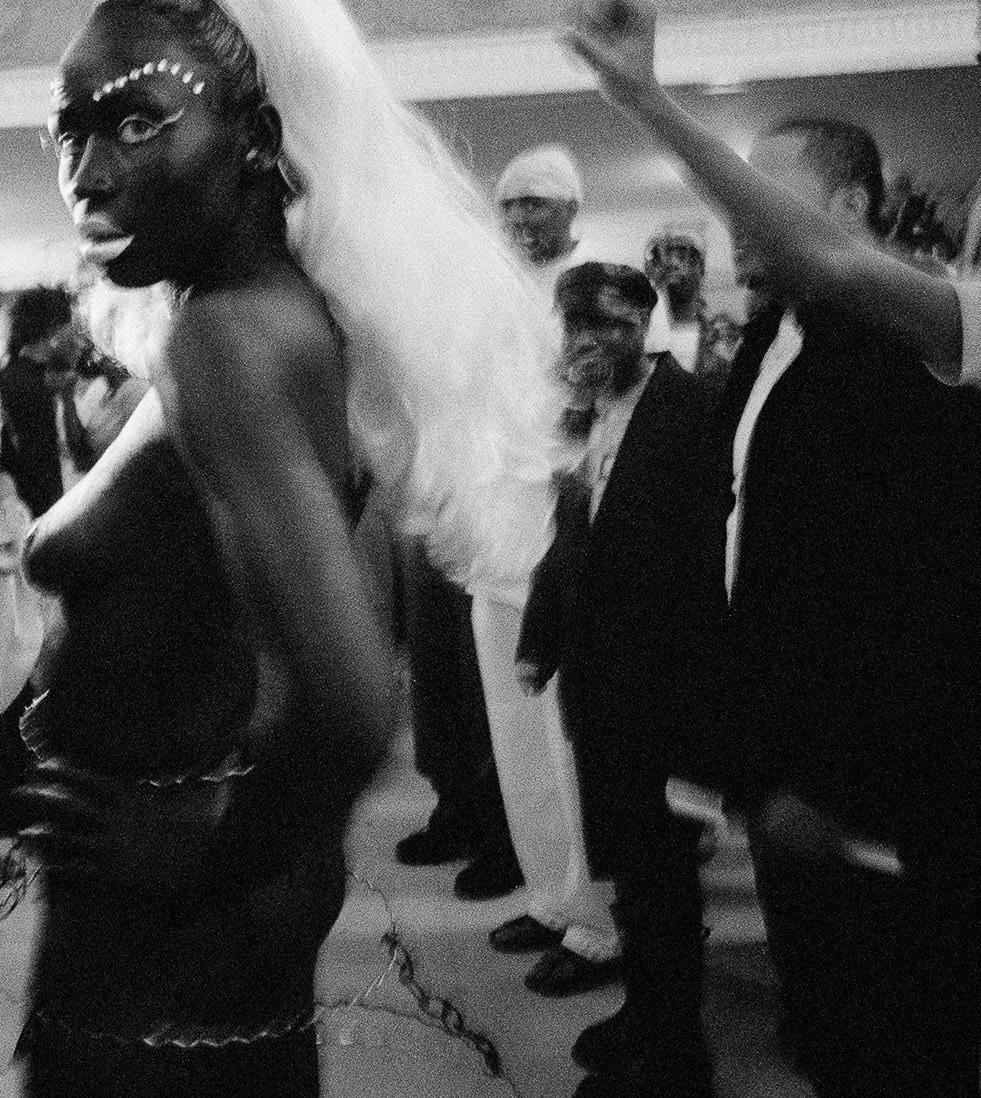

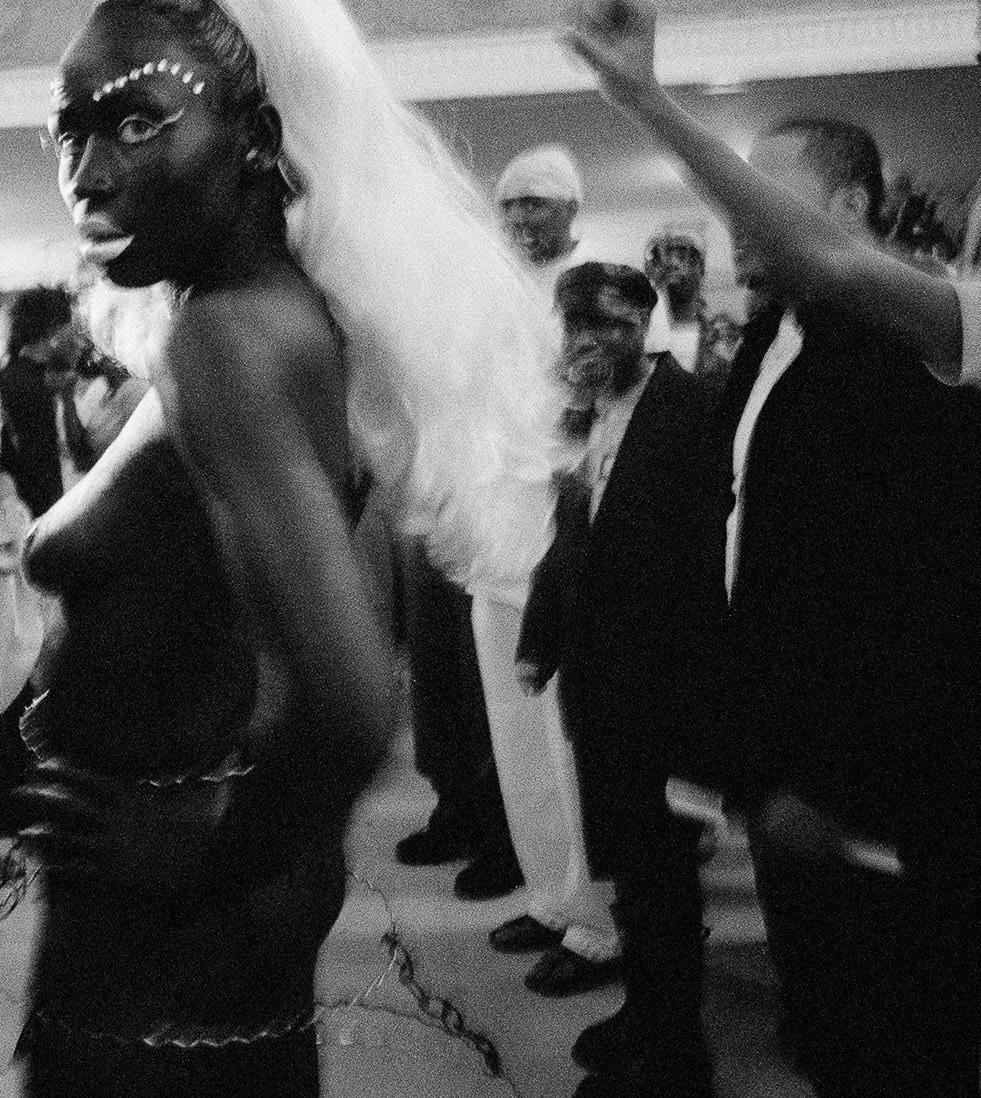

Groovy disco ball retro saturday night bee. Unknown author From the book “Legendary: Inside the House Ballroom Scene”. Gerard H. Gaskin

the book “Legendary: Inside the House Ballroom Scene”. Gerard H. Gaskin

11

Vanessa Mizhari serving face. From the book “Legendary: Inside the House Ballroom Scene”. Gerard H. Gaskin

Baby at the Tony Andrea and Eric Ball, Brooklyn, New York City, 2000. Gerard H. Gaskin

(Ed.)

Mariana Braga

14

Mariana Braga

Preface

Prejudice, discrimination, and racism are, unfor tunately, very common and still current subjects nowadays, as well as topics related to gender identity and fight for equal rights. Vogue, a dance originated in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City, was created in the 1960s by Afro and Latin American members of the LGBTQIA+ community, with the purpose of deconstructing cer tain preconceived ideas and opening some minds about issues that are still so contemporary, such as racism, homophobia, or transphobia.

The present book aims to explore the sub ject of vogue and ballroom scene, the underground subculture to which it belongs. An anthology or edited volume that seeks to bring together not only a collection of texts considered essential to the understanding of ballroom culture, but also a selection of images that resume and illustrate the movement from the time of its conception to its rise to mainstream culture.

Developed as a research project in the con text of the Master's Degree in Graphic Design and Editorial Projects, of the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Porto and having as advisor Professor Rui Paulo Vitorino dos Santos, the purpose of this project is to be a compilation of material from different sources which best summarize and explain the ballroom movement. For that we have chosen a bunch of authors who, in our opinion, best describe vogue and its subculture. Since the goal was to faithfully represent this subculture, it was important that this selection included authors who belong to the ballroom, LGBTQIA+ and/or Afro-Latin American community.

Authors such as Thad Morgan, an African-American writer and digital producer; Tim Lawrence, a writer and DJ who used to frequent New York's nightlife in the 1990s; Joey Levenson, a non-binary and queer writer; Lola Ogunnaike, an African-American journalist; Sandra Guzman a pioneering Indigenous Caribbean born storytel ler, culture writer, and documentary filmmaker; Julianne Escobedo Sheperd, a Xicana writer, reporter and editor; Sophie-Yukiko Hasters, a

writer and dancer from the House of St. Laurent; Kenya Hunt, an African-American writer, editor, author and creative consultant; Benji Hart, an edu cator, artist, and abolitionist; Michael Roberson, a member of the Haus of Maison-Margiela; and Stephaun Elite Wallace, a Ballroom Icon of The Legendary House of Blahnik, to name a few.

In addition to this variety of authors, this book has an introduction written by me, the edi tor. Besides the introduction, which in a few words aims to explain what this dance and respective subculture are, this anthology also includes a brief history and genealogy of vogue, as well as chapters where its different styles, associated problems, personalities, and places where it was (and continues to be) practiced are presented. At the end, it also features a list of terminologies, categories, as well as places, houses and perso nalities related to this culture.

Through a point of view of a graphic desig ner, that is at the same time author and editor, the main purpose of this artifact is to affirm the role of graphic design as a tool that enhances different views on what may be considered marginal, sub culture, or counterculture, through a publication that gives it visibility and values the plurality of its manifestations and its members, from a collection of texts and images that we consider fundamental to understand the history and the importance of the movement in the present.

15

2022

Deep in Vogue

Elements of Vogue

References

16 Index Love

Message

is the

Mariana Braga

Thad Morgan

Tim Lawrence

Philippe from Barcelona Dance

Joey Levenson

Andy Thomas

Tim Lawrence

Lola Ogunnaike

Terry Monaghan / Sandra Guzman

Julianne Escobedo Shepherd

Gran Varones

Miss Rosen / Brittany Natale

Allyn Gaestel / Sophie-Yukiko Hasters / Juule Kay

Kenya Hunt / Daphne Milner / Rachel Hahn

Jocelyn Silver / Michelle Lhooq / Benji Hart and Michael Roberson

Mariana Braga

Stephaun Elite Wallace Mariana Braga

Introduction

× History

× Genealogy

Vogue and Waacking NYC and the Ballroom Scene

On the Dancefloor Vogue Tracks

Willi Ninja, the Godfather of Vogue Into the Mainstream Vogue Styles

The AIDS Crisis The Club Kids Vogue Around the World Vogue Into Fashion American Vogue Today

Terminology

Categories

Listing

× Ballrooms

× Clubs

× Houses

× Personalities – DJ’s Photographers – Main Personalities

Bibliography

30 36 44 52 66 92 102 108 122 130 136 160 184 210 244 248 256 256 256 256 257 257 257 258 268

17

20

Love is the

Message

20

21

Introduction

Vogue, which is also referred to as voguing, is a dance style created by young Afro and Latin American, members of the Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Queer 1 Intersex Asexual Plus (LGBTQIA+) community, mainly transgender women and gay men, in Harlem, New York City. This style became popular in the nineties of the twentieth century, mainly due to Madonna's single Vogue (1990) and Jennie Livingston's documen tary Paris Is Burning (1991).

Its origin is still considered slightly unclear, with opinions that differ regarding the place and year of its appearance. Tim Lawrence (2018), in the introduction of the book Voguing and the House of Ballroom Scene of New York City 198992, mentions that vogue started from the drag queens2 ritual of throwing "shade" (p.5) in other words, from their habit of subtly insulting each other. According to David DePino, the alternate DJ at Paradise Garage3 and the DJ of the House of Xtravaganza4:

'It all started at an after-hours club called Footsteps on 2nd Avenue and 14th Street, [...] Paris Dupree was there and a bunch of these black queens were throwing shade at each other. Paris had a Vogue magazine in her bag, and while she was dancing, she took it out, opened it up to a page where a model was posing and then stopped in that pose on the beat. Then she turned to the next page and stopped in the new pose, again on the beat.' The provocation was returned in kind. 'Another queen came up and did another pose in front of Paris, and then Paris went in front of her and did another pose,' adds DePino. 'This was all shade-they were trying to make a prettier pose than each other-and it soon caught on at the balls. At first, they called it posing and then, because it started from Vogue magazine, they called it voguing' (as cited in Lawrence, 2018, p. 5).

Another possible explanation for its origin is that it was created by the homosexual inmates of Rickers Island prison in New York, 'who exchan ged shade and poses as a way of whiling away the hours' (Lawrence, 2018, p. 5). According to Kevin Ultra Omni, a veteran of the ballroom scene, "Maybe they didn't have a name for it, but that's what they were doing, or so it's said " (as cited in Lawrence, 2018, p. 5). As described in this same text, Omni acknowledges Paris as the pioneer of the style, but he believes that it existed in some other form through other people, as he also argues that many of the poses have their origins in African art and Egyptian hieroglyphics (idem).

An alternative genealogy of vogue, des cribed by Thad Morgan (2021), refers to the end of the 19th century, when in Harlem, at Hamilton Lodge No. 710 drag balls were held. These drag balls were events where drag queens, usually men dressed as women, but also the opposite, would compete to achieve miss titles. These events were more than mere competitions, a spectator of the Hamilton Lodge Ball described them as spaces "for a grand jamboree of dancing, love making, display, rivalry, drinking, and advertisement"(as cited in Contributors, 2012).

Their contestants were quite eclectic in eth nicity, gender and sexual orientation, however men who dressed as women were the main attraction (Morgan, 2021). Although these pageants were interracial, white contestants were generally favo red (idem). For this same reason, in the early 1970s, Crystal LaBeija, a black transgender woman, who used to participate in these drag balls, influenced by her friend Lottie LaBeija, decided to create her own ball. With her first ball also came the first house, the House of LaBeija, with Crystal as mother5 (ibidem), despite Tim Lawrence descri bing Marcel Christian as the possible creator of the first black ball in 1962 (Lawrence, 2018, p. 5). There are also those who argue ano ther version regarding the creation of the first house, Kevin Ultra Omni believes that it was called Brooklyn Ladies, was created in 1970 by Miss

23

2022

Paris, Pepper and Lottie and that House of LaBeija was only founded in 1977 by Pepper and Lottie, with Crystal assuming the mother role and Pepper assuming the same role in 1982 (Omni, as cited in Regnault, 2018, p. 61).

In the article Queens and queers: The rise of drag ball culture in the 1920s (2016), Oliver Stabbe states that in the beginning, despite their popularity, drag balls were considered illegal and immoral by most of society. However, since the 1920s they have gained visibility and started to attract heterosexual audiences as well, although strai ght artists, writers and ball appreciators outside the lgbt community frequented these spectacles due to their renowned reputation.

From the beginning, the ballroom scene, an expression com monly used to refer to the subculture to which vogue belongs, has emerged as an inclusive space, not only for people belonging to queer, black and Latino communities, but also for those who respect it and who recognize it as a space for family and self-expression. Chantal Regnault is a Parisian photographer who documented through photography ballroom culture from the late 1980s to the early 1990s. According to Joey Levenson (2021), despite being a straight cisgender woman, Chantal was welcomed, encouraged, and admired by vogue dancers and by the ballroom family.

Vogue is a very eclectic style, as it is formed by a fusion of the most diverse influences, from urban dances to classical and contemporary ballet or even African art. "Hieroglyphics, Olympic gymnastics, and Asian culture, mixed with the greats, like Fred Astaire", are described by Messy Nessy in the article Meet the Godfather of Voguing (2018) as the influences of Willi Ninja, a young dancer of Afro-Latin descent, proclaimed the godfather of vogue. For this very reason, and since it is a style that was born in an urban and underground context, it is understandable that there is no clear definition when it comes to the exact moment of its creation. It's possible that all the stories that try to date the appearance of the style are real and that the creation of this dance didn't have an exact moment, but a bunch of contemporary events that justify it.

1. Gender identity or sexual orientation that is not considered traditional, normative or majority (Priberam Dictionary, n.d.).

2. A person who ostentatiously dresses in feminine clothes, uses make-up in an extravagant way, is very expressive in his or her gestures and normally presents himself or herself as an artist in shows, parties, concerts, etc. (Dicio, n.d.).

3. The Paradise Garage, also known as "the Garage" or "Gay-rage", was a New York City nightclub notable in the history of dance and pop music, as well as to LGBT and nightclub culture. Founded in 1977 by its sole proprietor Michael Brody it was initially located in a building at 84 King Street in the SoHo neighborhood. It operated until 1987 and featured notable resident DJ Larry Levan ("Paradise Garage", n.d.).

4. Founded in 1982 by Hector Valle, a homosexual of Puerto Rican descent, House of Xtravaganza is one of the best known and oldest houses of the New York underground ballroom scene, still active to this day. Its members, of predominantly Latino origin, are renowned for their cultural influence in the domains of dance, music, visual arts, nightlife, fashion, and community activism. Today they continue to be represented by the media and travel the world as ambassadors of the vogue and ballroom scene ("House of Xtravaganza", n.d.).

5. The role of mother is the role played by the member of the house who has the function of managing the family and responsibility for its descendants, also referred to as children.

Ballroom legends of Atlanta’s underground voguing scene, 2018. Christian Cody

Mariana Braga

Ballroom legend of Atlanta’s underground voguing scene, 2018. Christian Cody

24

Willi Ninja. By: Andrew Eccles

Barbara Tucker. By: Andrew Eccles

By: Andrew Eccles

Willi Ninja. By: Andrew Eccles

Barbara Tucker. By: Andrew Eccles

By: Andrew Eccles

Bravo Lafortune and Barbara Tucker.

Bravo Lafortune and Barbara Tucker.

Bravo Lafortune. By: Andrew Eccles

Bravo Lafortune. By: Andrew Eccles

30

Archie Burnett. By: Andrew Eccles

31

Archie Burnett, Bravo Lafortune, Barbara Tucker and Willi Ninja. By: Andrew Eccles

32 ×

History Thad Morgan

Drag performers competing on stage during a beauty contest. Miss Manhattan, Miss New York, Miss Delaware County, Miss Brooklyn, and Miss Fire Island. New York, February 20, 1967. Fred W. McDarrah

In the early 1970s, Black and Latinx gay, trans and queer people developed a thriving subculture in house balls, where they could express themselves freely and find acceptance within a margina lized community. It was here where the world of drag pageantry, which often favored white contestants, evolved into competitions that spanned a variety of categories, including “vogue” battles. All these events can trace their origins as far back as the late 1800s.

Harlem’s Hamilton Lodge No. 710 hosted regular drag balls during the post-Civil War era. Attendees varied in race, gender, and sex — with some women taking part by wearing men’s clothes — but the main attractions were female impersonators who showed off their gowns and bodies to a panel of judges as if they were in typical fashion pageants.

As these balls continued for decades, they grew in popu larity — and notoriety. By the early 20th century, drag balls were considered illegal and taboo to the outside world. That drove the competitions underground (and undoubtedly added to their appeal). Spectators for drag balls expanded from “a few courageous spec tators” in the 1800s, to thousands by the 1930s, according to a collection of essays about the balls at the New York Public Library.

The growing freedom and expression of Black culture during the Harlem Renaissance also fueled the burgeoning drag ball scene into the 1920s. The era not only allowed African American artists — from painters and authors to dancers and musicians — to expe riment with and reinvent their crafts, it also saw popular Black artists experience and explore gender, sex and sexuality like never before. “Langston Hughes has gone on the record, talking about his expe riences attending events where men were dressed as women, and all of that,” says Julian Kevon Glover, assistant professor of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies and Dance and Choreography at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Although drag balls were interracial at the Hamilton Lodge, prejudices were still at play. Judges generally favored white, Eurocentric features. It wasn’t until 1936 — 69 years after their first ball, with an attendance of 8,000 spectators — that a Black contestant took home the top prize for the first time. As the balls expanded to other major cities in the early to mid-20th century, racial bias in judging continued.

When a white contestant, Miss Philadelphia Rachel Harlow, took the crown in the 1967 Miss All-America Camp Beauty Pageant, Black contestant Crystal LaBeija, representing Manhattan, claimed the judges had discriminated against Black and Latinx contestants and that the pageant was rigged. “She can’t help it. Because you’re beautiful and young, you deserve to have the best in life, but you

33

HISTORY 2021

34

Crystal LaBeija (left) in a still from The Queen (1968), directed by Frank Simon. Grove Press/Photofest

Thad Morgan

didn’t deserve… I didn’t say she’s not beautiful, but she wasn’t looking beautiful tonight,” LaBeija said about Harlow’s crowning.

LaBeija refused to participate in other drag pageants, but she didn’t exit the ballroom scene altogether. In the early 1970s, Harlem drag queen Lottie LaBeija convinced Crystal to promote her own ball. Crystal agreed, and the House of LaBeija — the first ever ballroom “house” — was born, with Crystal at the helm as the “mother.”

From its inception, ballroom houses offe red security for Black and Latinx queer, gay and trans people. These houses became more like families than teams, led by house “mothers” or house “fathers” to guide and groom their house “children” for the world.

“In ballroom, houses offer the primary infrastructure upon which the scene is built,” explains Glover. “It provides the basic kind of kinship struc ture, and demonstrates alternative possibilities for what kinship can look like. Moving away from this reliance on one's biological family, and complica ting ideas of a family of choice.”

Crystal and Lottie went on to host the first house ball in Harlem in the early 1970s, entitling it “Crystal & Lottie LaBeija presents the first annual House of LaBeija Ball.” The ball, designed exclu sively for Black and Latinx trans, gay and queer people, was a success. The house ball and the House of Labeija inspired many other prominent figures in the ballroom world to create houses of their own throughout the 1970s and beyond.

“Other trans women — some of them would never call themselves trans — the Pepper LaBeija, the Dorian Corey… Houses begin to be named after these women,” says Michael Roberson, resident of the Center for Race, Religion and Economic Democracy (CRRED) and founder of the House of Marison-Margiela.

House ballroom further differentiated from drag balls in 1973, when Erskine Christian became the first gay man to compete, according to Roberson. This signified a shift from trans women and female-presenting people in house ballroom

to the inclusion of gay men and male-presenting people in houses and house ballroom. “And you begin to see the shift again from mother-children to mother-father-children, so men begin to parti cipate. And so, ballroom morphs from drag ball to a house ball,” Roberson says.

Instead of the pageant-style of competition in drag balls, house balls held competitions between houses by categories. Categories range from face (the judging of a house mem bers’ beauty) to body (the appreciation of a house members’ curves), to runway, to performances including vogue.

Vogue is a type of improvisational dance inspired by the poses of models in fashion maga zines. The dance style originated within the world of gay and trans Black people, but its exact origins remain unclear. According to Roberson, some believe that Paris Dupree — a pioneer in the house ballroom scene — created vogue, while others believe that it was created by a Black gay or trans person in the New York City jail complex at Rikers Island. Willi Ninja, another legendary member of the house ball community, has also been referred to as the “Godfather of Voguing.” Regardless of its creator, the art form had another name before it was called vogue.

“Really, vogue was called pop, dip and spin,” explains Roberson. “And it's in relationship to break dancing. But when people who were double jointed, who were acrobatic, started putting that in their vogues, then they wanted to call it a new way of voguing, and call pop, dip and spin, old way.”

This “old way” of pop, dip and spin vogue dates back to the 1970s and 1980s. Then other elements of the dance were ushered in during the early 1990s, to form two new types of vogue dan cing, called “new way” and “vogue fem.”

While new way is characterized by precise movement of the arms, wrists and hands, vogue fem is broken down into either fast, angular move ments or much slower, sensual and deliberate movements. The five fundamental elements of vogue fem include hands, catwalk, duckwalk,

35

2021 HISTORY

spins and dips (which are often erroneously refer red to as “shablams” or “death drops”) and floor performance, according to Glover.

Willi Ninja described voguing as a way of throwing shade, or criticizing, opponents on the dance floor, in the 1990 documentary “Paris is Burning.” But, beyond a dance style and competition, voguing came to represent much more. “Voguing is very much about telling one's story through movement... And that for me, because of who is doing it, is very much an act of resistance to an entire world that not only tells us that our lives are devoid of meaning, but also tells us that we have nothing to contribute,” says Glover. “It's a kind of resistance, an embodied kind of resistance, to these cultural messages. To say, ‘No, I have a story to tell, and my story is going to be so convincing, that in this particular atmosphere you're going to be able to clearly understand what it is that I'm saying.”

Voguing as a form of expression became more mainstream with the release of media like Madonna’s song, “Vogue” and the documen tary, “Paris is Burning,” released in 1990 and 1991, respectively. Madonna’s “Vogue” paid tribute to ballroom and featured voguers such as José Gutierez Xtravaganza and Luis Camacho Xtravaganza in the video. However, Madonna was accused of culturally appropriating a culture that she had no claim to and turning a rich history of vogue into a fad.

“Paris is Burning” took viewers directly inside the ballroom scene. Filmmaker Jennie Livingston began filming the events after seeing people voguing in New York City’s West Village. The film is often referenced within the LGBTQ+ community and beyond. The ballroom term “throwing shade” was even added to MerriamWebster’s dictionary in 2017. But Livingston, as a queer white woman, has been accused of enabling cultural appropriation through her documentation of house balls. Several participants in the docu mentary also threatened to sue after not receiving compensation following the success of the film.

Glimpses of ballroom culture continued to permeate mainstream spaces more prominently since the early 1990s, through television series such as RuPaul’s Drag Race, which premiered in 2009; the MTV series America’s Best Dance Crew, featuring trans Black voguer Leiomy Maldonado in 2009; and Ryan Murphy’s Pose in 2019, which featured a scripted take on the house ballroom scene and included the most trans actors in tele vision history.

Glover says they expect ballroom culture to continue to evolve as a vital element of the Black queer community — and periodically influence broader audiences. “I think about ballroom as being a whale,” Glover says. “It primarily dwells deep, deep, deep in the ocean. But there are moments when the scene comes up for air and emerges through the water, making a splash within the popular culture scene before returning to the oceans depths while those on the surface feel its ripples for quite some time.”

36

Thad Morgan

Magazine photos of drag queens preparing for a performance in the “Female Mimics,” volume 5, issue 3, from 1974. This magazine covered drag culture, detailed new hotspots for performances, and gave amateur performers tips on makeup, clothes, and more. Photos from the museum’s LGBTQ collection

37

2021 HISTORY

Harlem nightclub dancers, 1937. Aaron Siskind

× Genealogy

Paris Dupree, the drag who created the ball “Paris Is Burning”, from which the iconic documentary drew its name, poses during a phoshoot for the 1995 COLOURS Organization calendar. Dupree grew up in Philadelphia and later moved to New York. The COLOURS Organization

38

Tim Lawrence

Growing out of the drag queen ritual of throwing “shade”, or subtly insulting another queen, voguing can be traced back to the early 1970s. “It all started at an after-hours club called Footsteps on 2nd Avenue and 14th Street,” says David DePino, the alternate DJ at the Paradise Garage, and a DJ for the House of Xtravaganza, the first all-Latin drag house. “Paris Dupree was there, and a bunch of these black queens were throwing shade at each other. Paris had a Vogue magazine in her bag, and while she was dancing, she took it out, opened it up to a page where a model was posing and then stopped in that pose on the beat. Then she turned to the next page and stopped in the new pose, again on the beat.” The provocation was returned in kind. “Another queen came up and did another pose in front of Paris, and then Paris went in front of her and did another pose,” adds DePino. “This was all shade—they were trying to make a prettier pose than each other—and it soon caught on at the balls. At first, they called it posing and then, because it started from Vogue magazine, they called it voguing.”

An alternative genealogy has it that the dance style was forged by the black gay inmates of Rickers Island, a New York City jail, who exchanged shade and poses as a way of whiling away the hours. “Maybe they didn’t have a name for it, but that’s what they were doing, or so it’s said,” comments Kevin Ultra Omni, head of the House of Omni and a veteran of the scene. “I know Paris was an early pioneer of voguing. But I believe that vogue existed in some other form through other people as well. I also think that a lot of voguing poses come from African art and Egyptian hieroglyphics.”

Taking their moves into New York’s disco theques and bars, voguers steered clear of the centre of the floor, where the concentration of dancing bodies would be at its most concentrated and the intensity of the party felt at its strongest. Instead, they headed to the periphery of the floor, or even a back-room area, where they would find more space to execute their moves and, perhaps more importantly, enjoy the kind of space that

would enable them to see and be seen. The honing of skills continued on the West Side Piers, where drag queens hung out in houses, or extended non -nuclear families that were organized by mothers and fathers who would take care of their children and help them prepare for drag balls. Held once a month, the balls were extravagant affairs that enabled houses to compete with one another across a range of categories. The emphasis placed on dressing, walking, and posing also meant they doubled as a place where drag queens further honed their voguing skills.

One of the earliest discotheques to attract a black gay crowd, Better Days contained a main dance floor where the legendary Tee Scott played a mix of hardened funk and disco, and a back room, where dancers would head if they fancied a break or a spot of cruising or a chance to dance the hustle. It was there that Omni noticed voguers modelling in front of what might have been an ima ginary mirror, styling and posing in time with the music, turning a hat sideways before bringing it back, and pivoting with grace, “all to the beat”. “I met Paris in 1975,” says Omni, “and I remember her in Better Days, posing on the back dance floor and throwing shade.”

Having focused on striking poses as if they were fashion models, voguers began to introduce contorted, jerky, slicing moves into their repertoire after they became familiar with the swift, angular movements of Bruce Lee and his co-stars while working trade inside Times Square’s porn cine mas, or heading there after a night’s work to get some rest. “Hand movements, posture, attitude and presence were most important,” Willi Ninja, the founding mother of the House of Ninja, com mented in 1994. “Then people started doing splits, and Hector [Xtravaganza] and I started disloca ting our arms and doing what they now call ‘arm clicking’, where you’re dislocating the arms and doing cartwheels and aerials. And then I began combining martial arts movies.”

Ninja, who also took inspiration from the Asian neighborhood where he grew up, adds: “The

39

Tim Lawrence 2014

Vogue Cover, July 1, 1967. From the Vogue Magazine Archive

dance takes on many forms. It combines a little technical dance, from, say, jazz and ballet, with acrobatics. As for my own form, it has as much to do with watching Indian and martial arts movies and fashion shows and putting bits and pieces together. There’s Latin base, which is the flowing movements, and then there’s the African base, which is the hard, strong, blocking and clicking.”

The outlook of voguers was improbably close to those of the breakers who started to hone their style in the Bronx in the second half of the 1970s. Both sets of dancers developed their skills through a mix of competition, athleticism, and an impulse to be noticed rather than to blend into the crowd (the aim of most partygoers of the era). In addition, the voguing technique of throwing shade was matched by the breaker turn to burning, or the miming of miming attacks and insults. But while both sets of dancers were committed to “keeping it real”, their understanding of what that involved contrasted radi cally, for while hip hop realness was grounded in the idea of urban authenticity, voguers viewed it as an ability to pass as someone they weren’t, or to perform drag effectively. Moreover, the societal status of the sexual preferences that underscored these differences led breakers to dance in public settings, often in broad daylight, while voguers headed to the abandoned piers or the clandestine spaces of gay-driven dance venues and drag balls.

The article “Fashion to Enjoy - the Price Is Right - the Girls Is Cher”. November 1, 1969. From the Vogue Magazine Archive

The article “Looks We Love Right Now in U.S. Fabrics”. January 15, 1969. From the Vogue Magazine Archive

40

Tim Lawrence

41 2014 Tim Lawrence

Deep in

Vogue

44

45

Vogue and Waacking

46

Philippe

Tyrone 'The Bone' Proctor belong to the first generation of Waackers that came out in L.A. in the early 70's. He was a member of the 'Outrageous Waack Dancers' with Jeffrey Daniel, Jody Watley, Sharon Hill, Cleveland Moses Jr and Kirt Washington. Tyrone is one of the last of the pioneers who named this dance style. This is a great honor an opportunity to spend some time with him to clarify some points about waacking while answering a few questions.

'How, when and where did the 'Waacking' style was born?'

'Waacking came from the gay community in the early 70's on the West Coast and it evolved from what the gay community was doing all along. At this time no one could imagine that this dance would be so popular as it is today. The dance was mainly danced by The Black and Spanish Community. It evolved from two things, Drag Queens performing, and Still Pictures and Musicals of old Females Stars from the 1920's to the 60's icons like: Greta Garbo's, Rita Haywards, and Marilyn Monroe to name a few.

The word from what I remember, came from me when I was describing the movement, I always told the people that when you wanted to move, you had to 'Waack' your arm, Jeffrey Daniels then told me that we had to put 2 a 's instead of one because we didn’t want to get it confused with the word 'wack' in English, means some thing that is not good. This way with 2 a 's we gave this word could have an all-other meaning.

47

Tyrone Proctor and dance partner Sharon Hill. By: Jeffrey Daniel

n.d. Barcelona Dance

Early 70s in the gay clubs were: The Paradise Ballroom, Gino's 1, Gino's 2, The Other Side, The Gas Station to name a few, where lots of dancers could be seen doing the style that will be called later Waacking or Punking. Some of these dancers would appear on Soul Train's. The dance moves you would see in the clubs would always end up on 'Soul Train'.

To name some of the first generation: Lamont Peterson, Blinky, Micky, Andrew Frank, David Vincent, Arthur, Tinker, John Pickett, Gary Keys, Dewayne Hargrave, Billy Goodson, Billy Starr, Lonnie (gymnastics), Abe Clark, Michael Angelo, and many, many more...'.

'What is 'Punking'?'

'To make a long story short, punking is a straight person's version of Waacking. Outside of the locker Tony Basil, there were a few straight people going to gay clubs and literally sit and watch them do the dance and while they were doing that it ena bled them to perfectionate the dance themselves.

There was a difference in the way the dan cers would dress: About the dress, Andrew would wear big, oversized Jackets to add more movement to Waacking. Arthur would like to wear high boots with his pants inside the boots. Tinker would like to wear tight shirts with short sleeves roll up or just cut off. The Women of Soul train would wear high heels and full skirts so when they turn the skirt would fly up to the beat.

Punking, the dancers would dress up like in the 40’s with high wasted baggy pants, tight shirt with big hats. Also, the Waacking style was a lot more emotional. Punking is more smooth and precision orientated.

'Is there a link between 'Locking' & 'Waacking'?'

'Many people think that Waacking started with Locking, and this is not true. You have to unders tand the climate back then, Waacking was danced by people who were not socially tolerated, it came with a different music style: the Disco. The Waacking scene was underground, and nothing came out mostly because people would be label led as 'gay'.

Tyrone believes That when the Gay Community abandoned Waacking in the late 70's that same time people were being introduce to a dance called Locking and some of the people who had been teaching Locking were also teaching Punking at the same time.

All my respect and love to Don Campbell for creating the 'Locking style' that had such a prolific influence on the dance scene. The Lockers were all straight guys but they had respect for gay peo ple. I admire them all of them. Actually Scooby-Doo taught me how to Lock.

Thanks to Toni Basil, dancer like: Andrew, Lonnie, Billy, and Tinker at Gino's were so good that they ended up dancing with celebrities like Diana Ross. Some of the members of "The Outrageous Waack Dancers" were in the group "Shalamar", Jeffrey Daniel and Jody Watley.

'Tell us about your best experiences?'

'The first one was when I arrived in L.A., it was on Tuesday September the 22 1972 at 10h22pm, it was milestone in my life. As soon as I arrived, I was immediately become friends with the Soul Train gang. I met Little Jo Chism who took me to all the clubs and to the Paradise Ballroom in L.A. where I first saw "Posing" dancing.

Tyrone Proctor and dance partner Sharon Hill on the set of Soul Train. In its early days, most Soul Train dancers were local high

school students who attended Dorsey, Locke, and Crenshaw. They became the nation’s trendsetters but their only

payment was a chicken dinner and Coca Cola. Los Angeles, 1976. Photo by: Bruce W. Talamon

48

Philippe

49 n.d. Barcelona

Dance

The second high light of my life was to have the chance to enter Soul Train as a dancer the same year and to tour with Don Cornelius and the Soul Train gang with famous groups such as Eddie Kendricks, The 'Whispers and the Monents'.

I would like to say that thanks to Soul Train because many dance styles came out to public such as Locking, Popping and Waacking and all this was made popular from this one show. The dance moves of John Travolta in Saturday Night fever were directly taken from the Soul Train Show (Locking and Waacking).

Another highlight of my life as dancer was to be meet Sharon Hill as my dancing partner, we won a national contest dancing together. Also, another highlight was to be able to travel to Japan with the 'Outrageous Waack Dancers' including

Tammy, Cleveland Moses, Kirtland Washington, Sherry Green and myself. At this time, I think only "The Lockers" and a group called "Something Special" had been there.

My other following great experience was to go to New York and to be part of a group called "Breed of Motion" which was the first "Waacking" singing group including the late great Willie Ninja.

After that, Jodie Watley called me in New York asking me to do the music video in Paris cal led 'Still a Thrill' and that was actually the first music video ever to incorporate "Waacking". Then from there I had the opportunity to choreograph ano ther music video from Taylor Dane 'Tell It to My Heart' which is the first video ever to have Voguing in it (1987).

'How were the castings organized to appear in Soul Train?'

'The were auditions in a recreation center in L.A on a Saturday. The teen coordinator at this time was called Pam Brown, she would come with Don Cornellius (the Creator and Host) a week before the TV show and would pick up some dancers passing through a Soul Train line set up for the audition. The people who were selected would be listed on the TV studio's guest list. If your name was not on the list, you couldn't get into the dance studio. We taped the show one weekend a month they would tape 2 shows on the Saturday and 2 on Sunday.

'Where did you get your name Tyrone 'The Bone' Proctor?'

'This is actually Don Cornelius from Soul Train who called me 'The Bone' because I was very thin at this time.

'What came first Waacking or Voguing?'

'The first was Posing, I still remember them playing the track "Papa Was a Rolling Stone", on each

50

Philippe

'boom' of the track the dancers were doing a dif ferent Pose, you could see all these dancers on Posing, this was phenomenal, then Waacking and then Voguing. They all have a common point, they come from the gay community. On the straight commu nity you would have the Funk and Soul which evolving to the Hip Hop meanwhile on the gay community you would have Waacking with Disco that was popularized in the early 70s it also evol ving to Voguing with House Music the early 80s. Both styles had syllables that were seen in the gay community before they were set as dance forms. The big difference between Disco and House is the BPM (Beat Per Minute) is that Disco was a lot faster (approx. 127-145bpm) than House (approx. 112-121bpm) and the content is different, in the Disco you have a lot of horns and violins and other instruments that you interpret with the dance. Voguing is more concentrating, more com petitive, angular and a less emotional. Voguing was popularized through the medium of Super Models such as Iman, Beverly Johnson, Janet Dickinson, Grace Jones, Pat Cleveland, you had all these girls that would be on a runaway walking up and down. The gay community would emulate that on the street, pretending to be these super models. The Egyptian culture had a big influence on vogueing. Also remember of Willie Ninja that was watching a lot of Kung Fu movies and would apply some of the moves in his Vogue style of dancing.

'How did you start teaching Waacking?'

'It's actually Jeffrey Daniels who initially told me that I should start teaching Waacking when he was in Osaka Japan in 1991. Then Brian Green kept asking me to teach Waacking. I was reluctant but he insisted so I started doing it. I am one of the last of the living pioneers and with the Resurgence of Waacking. I am extremely lucky and honored to have met in my lifetime some of the greatest dancers in human history.

'People call you the creator of the Waacking, do you agree with this?'

'I appreciate that, but I can't take credit for it. It's very difficult say who created Waacking because it came from different minds, and it was a variation of different styles. I put a name 'Waack' so people could understand the movement. My part is to secure dancers such as Lamont Peterson, Blinky, Micky, Andrew Frank, David Vincent, Arthur, Tinker, John Pickett, Gary Keys, Dewayne Hargrave, Billy Goodson, Billy Starr, Lonnie (gymnastics), Abe Clark, Michael Angelo, and many, many more, because many are no longer with us.

I want everybody to know who were the real Pioneers in this dance form called "Waacking" I just loved the dance and loved to see young people dancing it. I just can say that I am honored and humble that people would remember me that I was there. But you also have people like Anna Sanchez, Angel Pioneer and Toni Basil who came a little bit after me but still are a valuable source of informa tion on Waacking and Punking.'

'Is there anything you would like to add?'

I always tell people that they need to follow their dream because their dream should set them free. Aus, Shake, Eva, they are like my babies, I love you guys! Just keep growing what you're doing!

Thank you for this interview, Tyrone, it's been a pleasure to meet you!

51

Leonard Jones, Jeffrey Daniel, Tyrone Procter and Jody Watley. 1975, for Right On! Magazine

n.d. Barcelona

Dance

52

53

Jody Watley with Tyrone Proctor in the official music video of her single "Still A Thrill", 1987.

NYC and the Ballroom Scene

54

Joey Levenson

Between 1989 and 1992 in New York City, French photographer Chantal Regnault had her entire outlook on life changed. She dis covered, in all its prime glory, Harlem’s house ballroom scene. It was a culture that had evolved from the long-established pageantry of drag queen balls, a parade of gender fluidity and expression by way of competition and aesthetics. Entrenched into the folds of cosmo politan life since the turn of the 20th Century, balls – as they came to be known – were spaces for the non-conforming queer community to flourish as a heterosexual society set out to diminish them. It was Harlem drag queens Crystal LaBeija and Lottie, in 1972, who recognized that the drag queen balls and pageants were no lon ger satisfying nor appreciating them as Black queens, and so they divested from the drag balls to create “houses”: kinship networks founded not on blood but on relational aspects of their identity. Quickly, young Black queer people of New York City flocked to find a community that had been lacking for so long. And with the advent of houses came a more youthful, performance-orientated energy. Classical “cross-dressing” drags with feathers and beads became secondary, and the art of posing and performing now coined as “voguing” came first.

By the late 80s, voguing had taken off, and runway cate gories in the ballroom were everything. At the same time, the spunky and audacious pho tographer Chantal was reading about their advent in The Village Voice, a famous New York based magazine which had a strong advocacy for gay rights. Chantal was relatively new to the country and was looking for inspiration in her larger-than-life appetite for culture, scanning through magazines such as Voice and New York

55

Luis, Danny, Jose and David Ian Xtravaganza, 1989. Chantal Regnault

2021 It's

Nice That

Native. When we speak with her, she’s full of joy about her time in the city. “I can understand everything better now,” she tells It’s Nice That. “It was a special point in the culture.” Born in France, there was simply nothing like this in Paris, where Chantal came from. For the young upstart, “it was incredible” to arrive in New York City and find such a glamorous, powerful community that was thriving despite the forces against them. Wide-scale violence and AIDS were the two looming specters, the latter of which had already ravished much of the queer community by 1988. “During the AIDS crisis, all the gay clubs had closed down because people were dying left and right,” she recalls. “And suddenly I was discovering ballroom, which was thriving underground as it always had.” At that time, the balls were almost exclusively attended by Black queer people, but Chantal bore witness to the rise of many Hispanic houses, and even one white house, all of which congregated to create a gender diverse community of its own.

Instinctively taking her camera to the first ball she attended, Chantal found herself with tones of eager ballroom participants wanting their picture taken by her. She was hooked and returned monthly to every ball across the city. Yet still, she points out how she gets questions on her ability to do so even to this day. A heterosexual cisgender woman at these balls was incredibly uncommon, and today, even less so. “It was 30 years ago, and there was not so much questioning about how legitimate you were a part of the community or how legitimate you were to photograph them,” Chantal explains. On this note, her tone never waivers into criticism of politics. Instead, she speaks with a brazen clarity and focus that is much like her photographic prowess. “From the beginning, I was always very con siderate to how they felt and how they wanted to be photographed, that I was not there to bother them.” With such a cool-cat appro ach, Chantal was welcomed, encouraged, and fawned over by the voguers and ballroom family. “I realized not only did I not bother them, but I became part of the scene because I was a photographer, and any glamour girl loves a photographer,” she laughs. “And of course, I was French, and there was this whole mythology of France and glamour, so I was the French photographer.”

Today, Chantal still plays into the chic, Parisian artist arche type. She doesn’t mince words about anything, including the recurrent times when she gives her dues and respect to the peo ple who these photos are all about. “The ballroom was the trans culture at the time,” she says. “The central character was the ‘femme queen’.” In Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York City 1989-92, a book that collects a host of Chantal’s work at the balls and interviews with its legendary figures, the character of the

57

2021 It's

Dee Legacy at the House of LaBeija Ball, Tracks, 1990. Chantal Regnault

Nice That

“femme queen” is seen time and time again. In reality, “femme queen” was a category for the balls, not a character. It denoted transgender women of the houses who could seemingly “pass” as cis gender, which at the time Chantal brushes off as “simply the culture.” It wasn’t just the femme queen who Chantal noticed as the key figure of the ball, however. “New house mother Pepper LaBejija opened it to kids who were fresh from breakdan cing in the neighborhood and came on the scene,” she adds. “And Pepper was a real butch queen up in pumps.” Pepper, in fact, went on to become a renowned figure of the ballroom largely in part to her role in the widely successful cult classic film Paris is Burning, a documentary from the 1990s

which took voguing and ballroom to a cinematic level (for better or for worse).

But how did an average night of photogra phing the balls usually shakedown for Chantal? With each house preparing head-to-toe looks for different categories, runway presentations, and voguing battles, Chantal recalls how often there was a lot going on at all times. It was “little by little” that she learned to master her photogra phic domain over the balls. At the start, she would capture the houses as they walked the runway or vogued against one another, trying to be as flattering as possible. “It was not very beautiful to photograph them where it was badly lit,” she says, now well-tuned to the demands of a glamour girl.

58

Denise Pendavis, House of Omni Ball, Tracks, 1989. Chantal Regnault

Modavia Labeija and Angie Xtravaganza in the background, backstage of A Night of Fabulous Fakes and Voguing Competition, Apollo, Harlem, 1990. Chantal Regnault

Joey Levenson

59 2021

It's Nice That

Armed with her Nikon S-3, Chantal had to adapt to the low-budget setting of the high-glamour balls. “I wanted to use a flash for the color, because often those warehouses the house mothers (Dorian Corey, Paris Dupree, Pepper LaBeija, and Angie Xtravaganza) rented were not really nice, and they paid for them out of their own pockets.” But still, Chantal underlines just how incredible it was to be immersed in their atmosphere. “It was magic, it was completely magic,” she says with a glint of ecstasy in her voice. It’s an emotive pull to the voguers that reads clearly in her pictures: every image is electric, alive, loving, and tender. They veer away from voyeurism, and function comple tely as an uplifting platform to a community that embraced Chantal with such loving arms. Being a 40-year-old heterosexual foreigner in the midst of the ballroom atmosphere seems as if it would be dauntingly out of place. Yet for Chantal, it was nothing of the sort. “I would often go backstage, and it was like being backstage in a theatre,” she recalls. “All the characters, the models were there and trying to collect the money at the door, and everyone was in the toilets, and the hallways, putting on makeup, wigs, getting ready, being late.” It was a frantic, exciting atmosphere that Chantal often tried to capture, to much avail. She’d show up before the ball began and stay right up until its closing doors – “often at 6, 7, 9 am.” By the 90s, Chantal was no longer a spectator with a camera. She was the ballroom community’s hono rary photographer-in-residence, a friend, and a loyal asset. The photography had become a way to reaffirm an etched-out ballroom fantasy: that each member was a grandiose, modelesque, and wealthy uptown woman. “I believed in their fantasy because it would make you feel really good,” she admits. Here, Chantal errs on the defence, a tone that indicates her fierce loyalty to the community remains the same even decades later. “There was no nightlife, and we were thinking about all the people we were losing from AIDS,” she explains. “So suddenly walking into the ballroom was like another world where everybody laughs again.”

For that time, it was needed. The AIDS pandemic was mocked and belittled by the United States government, despite killing more men than the Vietnam war. Finding strength from their peers was a remedy for queers everywhere. “At the balls, there was always laughing, it was very joyous,”

60

Joey Levenson

Chantal says in one particularly emotional moment of clarity. “I want to point out, please, that it was extremely joyful.” Recently, the Kunsthal Museum in Rotterdam opened up a brand-new exhibition that surveyed the visual history of ballroom. Naturally, Chantal’s work was featured prominently. She was more than happy to participate in building the exhibition and attending its opening gala – but most

It's Nice That

61

Whitney Elite Garcon, Ira Ebony Aphrodite, Stewart LaBeija, Chris LaBeija Revlon, Ivan Adonis Chanel, Jamal Adonis Milan, and Ronald LaBeija, Best Face Jourdan Ball NJ, 1989. Chantal Regnault

2021

62

House of LaBeija, 1989. Chantal Regnault

Willi Ninja, 1989. Chantal Regnault

Joey Levenson

importantly, she was overjoyed that more people around Europe could see the photographs she had lovingly taken of her friends back in New York. But how did Chantal manage to be so prolific? “I decided very early on to photograph them all in the way they wanted to be seen,” Chantal explains. “It was very important, and I never tried to catch them half-done or with their make-up not ready or somewhat tired or with their wig on the side, you know? I wasn’t interested in going to that place at all.” She speaks as if this is a given fact, a decision that was never up for debate. As the ballroom participants picked up on Chantal’s eager cooperative and collaborative spirit, they began to willfully direct her: “can you take this photo like this?” became “shoot me like this!” which became “I want to be in this pose.” It made sense, considering ballroom was all about the Black queer and trans community reclaiming an agency of glamour that had been robbed from them in the outside world. “It was all about looking beautiful and real in there,” Chantal explains. “Outside the balls, a lot of them had no money and were living dangerously.” Rather simply, Chantal facilitated a space for beauty and realness within her lens for them all to flourish in.

Eventually, she settled on using black-and-white as her go-to, something that became her “thing,” as she nonchalantly recalls. Whilst Chantal simply chalks it up to being an “inspiring” medium, one can’t help but notice how the black-and-white of each picture brings the ballroom community into a deeply artistic realm – some thing they readily deserve. Off the back of these photos, Chantal built solid friendships with house mothers, voguers, drag queens, butch and femme queens. Soon, she was being invited back to their houses, tapped for photoshoots, and so on. One particular time, she had the likes of legendary voguer Willie Ninja (of Madonna’s Vogue fame) in a rented studio, giving her direction on how to build his portfolio. “I did the studio shots so I could have more control, but I let them have it all,” Chantal laughs. “I would do very little direction on the shoots. Just free, go with it. They loved it, and it made them feel more like professional performers.” By the end of a day’s worth of studio shooting, both Chantal and her model could walk away with a sizable professional-looking portfolio. The studio shots show another side to the figures of ballroom, as people who were infinitely capable of making art simply by the graphic shapes of their bodies. In their twisted and contorted poses, they are akin to statues of ancient divinity. “I wanted them to be supermodels,” Chantal adds. “They were the first Black models.”

Since so much time has passed, Chantal has grown increa singly astute about her time in New York. Whilst she does reminisce fondly about the balls, nothing is seen through a rose-tinted

63

2021 It's Nice That

spectacle. As we go through each picture, she’s reminded of those who have passed, of which she plainly says, “is a lot.” Yet with every year gone, Chantal still finds joy in what remains. “To my surprise, and my delight in a way, I was not fully aware of how important my pictures would become as an archive,” she explains. “I knew it was something special and beautiful and that's why I wanted to document it. But I was not fully aware of the importance of what I was doing.” She pauses here, as if to be careful with her emotions. “Now, only 30 years later, we can see the implications.”

As mainstream attention to ballroom has come and gone – Malcolm MacLaren, Madonna, Pose, Legendary – time shows that voguing has always been a commodity to some. During the 1990s, it was “an explosion” when “seemingly everyone” discovered ballroom at the same time. Yet, she’s

adamant that the exposure didn’t damage the community. “They persevered with or without the mainstream,” she says. Instead, this particu lar epoch wound up helping them “The world of fashion – which was also decimated by AIDS – had the idea to throw an AIDS benefit ball,” Chantal tells us. “This was the Love Ball, May 1989, with Susanne Bartsch and RuPaul, which I attended and photographed.” From then on, the benefit balls rapidly raised consciousness within the ballroom on how AIDS was affecting them. “The Gay Men’s Health Crisis created the Latex Ball in 1990 with the ballroom scene, because they needed it,” Chantal adds. “Ballroom was mostly Black and Hispanic and working class, and a lot of them were completely unaware of what was happening and treatment and protection.”

With such a wealth of knowledge, intelli gence, and compassion on the LGBTQIA+ community, it’s hard to think Chantal simply star ted all this “because it was fun.” A simple trip to a ballroom she saw advertised in 1988 ended in a complete re-routing of her life, even when she left New York City to settle in Haiti in the mid-90s, just as ballroom was really taking off into mainstream stardom. She left with no idea just how important her role as the photographer had really been. “There was no photographer following it at the time. Now, everybody’s a photographer,” she quips. “Now, there are almost as many photogra phers as participants at the ball.” Even in the midst of providing a canny observation on the evolution of contemporary voguing, Chantal still manages to find time to bring it back to the very people this is all about: the ballroom community. “I know the mainstream looks at something at one point and they don’t look at it at another, but through it all, the culture will never die,” she says.

In many ways, ballroom taught Chantal more than just how to photograph. It taught her how to live. When I ask her what it all means to her, she pauses for a while. “It taught me so much,” she finally replies, quietly. “You have to cross some lines to understand others.” From the beginning,

64

Joey Levenson

Chantal always knew her photography was a way to understand others. It was a way for her to appreciate difference, not observe it. “I wanted to understand who they were,” she explains. “But in the end, it taught me so much about how dif ficult of a life they all lead outside the ball.” Even though Chantal’s ballroom photographs situate themselves in the realm of happiness, community, and togetherness, she knows beneath all the fro zen scenes of smiles and laughter was an endless pool of strength and courage from all the Black queer and trans members of the ballroom. “Even within the gay world, they were ostracized and demonized,” she says. She speaks passionately, slipping back into the “mother” figure she took on when she was first photographing the ballroom,

when young performers flocked to her as one of the eldest people in the room. Overall, it’s clear a lot has stayed with Chantal through these pictures. Through memories of laughter and fun are memo ries that remind her of the reality of the violence, structural or personal, that the ballroom commu nity encountered. “To me, it was the epitome of injustice. The epitome of humiliation of another human being. And there was so much danger, especially for the femme queens,” Chantal says. “And it's not over.”

65

“The Revlon Boys” from left to right Jerome, Tony and Stewart, Central Park, 1989. Chantal Regnault

2021

Legendary Modavia LaBeija back from the Ball at “A” train early morning, 1991. By: Chantal Regnault

It's Nice That

66

67

From the book “Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York City 1989–1992”. Chantal Regnault

On the Dancefloor

68

Andy Thomas

One of the few DJs to sit in for Larry Levan at Paradise Garage, David DePino began his Tuesday night sessions at the Chelsea club Tracks in 1986. It was at Tracks that voguers from the ballroom community in Harlem and Brooklyn brought their competitive artistry into down town dance culture. By transporting the battles of the ballrooms into a downtown club, Tracks became a launching pad for many voguers who would later make Sound Factory their home in the early ’90s.

David DePino had been there at the birth of disco, dancing at David Mancuso’s first Loft parties on Broadway and working behind the bar at Francis Grasso’s Sanctuary at the dawn of the ’70s. He met Larry Levan at a Brooklyn club where DePino worked called Broadway, through Levan’s then-boyfriend Mario Deserio. At the time, Levan was cementing his reputation as a DJ at Reade Street. When owner Michael Brody was forced to close the club, it was DePino who found the new space that would become the Paradise Garage.

“I knew Reade Street had closed and one day I was hanging out on Christopher Street with some friends,” DePino says from his home in New York. “We saw a bunch of cop cars going down 8th Avenue, so we followed them, and it was a raid on this gay cruising area. We made a left turn down King Street and I said to my friend, ‘This looks familiar,’ and he said, ‘Didn’t we come here once to a party?’ And I said, ‘Yes, that’s right, it was that club Chameleon. Oh my God – I know Larry’s looking for a club.’ So, I wrote down the name, address, and phone number, then went back to Brooklyn and gave it to Mario to give to Larry.”

A hairdresser by trade, DePino got his first job in New York’s nascent dance culture through Judy Weinstein’s Record Pool. “While I was on vacation from my hair salon, Judy had got rid of her co-worker at the Record Pool. And so, she asked me to help her for a week until she found a replacement,” DePino says. “A week turned into two weeks, which turned into three weeks, and so on, until I stopped hairdressing and started working full-time at the Record Pool.”

With the move from Reade Street to King Street, DePino became part of the inner sanctum at Paradise Garage. “I worked there from the very beginning,” he says. “I was a good friend of Larry’s and used to work at the door by the DJ booth for the VIP section.” By 1985, Levan’s hectic production schedule meant he was often camped out late in the studio and delayed in getting to the club. “Larry started getting really, really busy in the recording studio, and so around midnight he’d call me up and ask me to put a reel-to-reel tape on. That was fine, as the club didn’t really get crowded until around 3 AM. When it became a more regular thing, I would also put

69

The Paradise Garage dance floor. Bill Bernstein from Disco: The Bill Bernstein Photographs (Reel Art Press)

2016 Red Bull Music Academy

70

Walter, Gilbert and Henry on the roof deck. From the closing party of Paradise Garage. New York, September 26, 1987. By: Tina Paul

71

72

Michele Saunders dancing, Paradise Garage, 1987. By: Tina Paull

73

74

Larry Levan, Liz Torres, and Jessie Lee Jones, Paradise Garage, 1987. By: Tina Paull

75

a record on, as people started getting bored with the same music.”

Through his job at the Record Pool, DePino had first access to many of the tracks that would become underground classics at the club. “Because I worked at the Record Pool I would bring Larry’s new records for that week,” he says. “So, what I would do early on was play the good records, so the crowd heard them for the first time. Then, if Larry was there early and was walking around, playing with the speakers or lighting, he would say, ‘Play the new records you brought in,’ or ‘Play the dub version,’ so he could hear how it sounded. So that’s how it started for me.”

Opening in 1985 at 531 W. 19th Street in Chelsea, Tracks New York was part of a franchise of clubs across the country owned by Marty Chernoff, linked to Tracks D.C in Washington. Chernoff brou ght in Michael Fesco (from Manhattan’s gay mecca the Flamingo) to run the club, and that’s when Tracks really made its mark on New York nightlife. It was soon open seven nights a week, 24 hours a day on the weekend. DJs who spun there included Terry Sherman and Warren Gluck from the Saint, as well as Steve Fabus from San Francisco’s I-Beam and Trocadero Transfer. Similar to the Saint, one of New York’s other legendary ’80s gay club, Tracks was initially frequented predominately by a crowd far removed from the black and Latino dancefloors of Paradise Garage and Better Days. “Before I started there, Tracks was a very white gay club,” says DePino. “It was mainly a kind of Hi-NRG sound there, and not the heavy black music I was playing or hearing at the Garage.”

DePino got his break at Tracks in 1986 through a friend he knew from the Record Pool. “A girl called Freddie Taylor, head of the one-stop Pearl Music (and Pearl Distributors Inc.), was friendly with someone at Tracks. She told me that the club was looking to bring in another DJ, and would I be interested? At the time, as well as sitting in for Larry at the Garage I was doing some teeny, little guest spots here and there. I said to Freddie that I hadn’t played a whole night before. But she convinced me to give it a try.”

Taylor spoke to Marty Chernoff, who suggested DePino could start on a Tuesday night. “My first night there was a Fat Tuesday Mardi Gras party, and I had about 40 people there. And the club held, like, 2,000,” recalls DePino. “So, I thought to myself, ‘This isn’t really going to go well.’ But they said they would give me a month to see if I could build it up.”

Conscious that few of the people on the scene knew that he was behind the new Tuesday night session at Tracks, DePino asked Marty Chernoff if they could print up some business cards. “I really wanted people to know that it was my party, so I had about 1,000 cards printed up that said this was a complimentary invitation from

76

Larry Levan during his decade-long residence at the Paradise Garage. Photo by: Bill Bernstein

Andy Thomas

David DePino. And I went all over town handing out these cards to every good-looking person I could find that went to clubs. So the next week I got another 50 people. Out of respect, I never promo ted at the Garage or looked to bring that crowd to Tracks. But it was such a cool, good-looking crowd I attracted that everyone started talking about it. Then, on the third week, there was an extra 100 people, and so on until at the end of the month I had, like, 500 coming. So, they said they were going to continue the Tuesday nights, and that is how my night at Tracks started. After two months I had 1,000 people, then after three months it was mobbed every Tuesday.”

David DePino’s residency at Tracks was one of the first successful midweek club nights in the history of New York club culture. “It changed the course of New York nightlife,” he says. “Clubs of that size only ever worked on a Friday or Saturday

until then. The places that opened in the week typically held about 50 or maybe 100 people, or there were bars with jukeboxes. Better Days was the only place that opened midweek. But if you had 200 people in Better Days you had a good party. Tracks held 2,000, and I had that every Tuesday.” With that capacity and its prime location in the gay hub of Chelsea, it was the perfect space for DePino to build his own night. “It was a great club,” he says. “It had a really big dancefloor and a little stage area. Then it had a second upstairs room where Danny Krivit and George Morel would play on alternate weeks. And it also had a roof deck. The Tracks soundsystem was also really nice, although it wasn’t like the Garage. We would tweak it, though, because the black crowd that I had liked a much more bassier sound than the white crowd who were there the rest of the week. So, we would raise the bass on the amps

77

2016 Red

Bull Music Academy

for Tuesdays, then they would lower them for the other nights.”

Like the many future DJs who danced at Paradise Garage, DePino had listened and learned from a master. “The way Larry made me feel on the dancefloor and how he made me lose my mind and to feel free to express myself, that is what I wanted to do to people. So, I tried to follow what Larry did in that way, but I knew I had to be myself and find my own voice,” says DePino. “Larry always told me, ‘The crowd are coming to hear what you love, and your job is to make them love it, too.’ He’d tell me, ‘Don’t give in to playing what they think they want to hear. They can go to a regular 9 – 4 club to hear that commercial stuff that they are playing on the radio.’ So, he’d tell me to play what I believed in. But he also taught me that it wasn’t about you as a DJ having a good time – it’s about making the people on the floor enjoy and feel part of the house party that you are throwing. And to always take them on a journey.”

How similar was the soundtrack at Tracks to the Garage? “I would say I played about 80% of the same records,” says DePino. “I would play all the classics I heard at the Garage, of course. But there were another 20% of records with a very particular kind of high-intensity sound, much fas ter than Larry was playing at the Garage. And that was when the whole vogue thing really started in the nightclub.”

While voguing was pioneered at the balls in Harlem, it had started to infiltrate Manhattan’s black and Hispanic gay clubs in the late ’70s. One of the clubs where voguing was first seen was Better Days, although Paradise Garage also had its fair share. In the introduction to the Soul Jazz book Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York City 1989-92, DePino explained how the Garage became a second home to the various Houses in the early ’80s. “Before you knew it, a lot of the ball kids were hanging out at the Garage. In one corner there’d be the LaBeijas, and in another there’d be the Duprees, and so on.”

It was at the Garage that David DePino

was introduced to perhaps the most famous of all the houses. “I became friendly with the House of Xtravaganza at the Garage in about 1983,” he says. “They were a new House [formed in 1982 as the House of Extravaganza by Hector Valle] and they asked me to play for them as their DJ at their first ball at the Elks Lodge in Harlem. That’s when I became an Xtravaganza [member]. At that time, the balls used to start at five in the morning on Sunday. So, I left the Garage, and Larry gave me a little stack of records that only he had that were about to come out. I took them to the ball and mixed-up records that would usually be played for each category with other records you would hear at the Garage. I’d never been to a ball before, so I didn’t know there were certain records for each category; I really didn’t know the procedures. So in-between each category, when normally it would be quiet in the ballroom, I would carry on playing records. And the ball went crazy, with everyone jumping out of the seats dancing. That gave me the idea that you could combine dancing along with the balls, and that is what we did at Tracks.”

Karl Xtravaganza joined the House in 1986 and worked as a bartender at Tracks. “Ballroom and Tracks collided at just the right moment, and David DePino was the catalyst for it,” he says. “In the late ’80s, Elks Lodge in Harlem, the traditio nal ballroom home for many years, was no longer available to host balls. At the same time, Chi Chi Valenti and Donald Suggs were putting a spotlight on the ballrooms in articles for the Village Voice, Details, The Face, and other publications. It was David DePino who got the management of Tracks to agree to host their first ball. That allowed the balls to move downtown just when awareness of the ballroom subculture was starting to spread.”

The first of these balls to be held at Tracks was the House of Xtravaganza’s Black & White Ball in 1988, hosted by DePino and David Ian Xtravaganza. “After the ball was over, I started playing records and we moved all the chairs and tables out of the way. And the voguers all started to dance until six in the morning,” recalls DePino.

78

Andy Thomas

79

Better Days, 1979. Better Days was a young, gay African-American and Latin crowd, where DJ pioneer Tee Scott played the records.

By: Bill Bernstein 2016

Red Bull Music Academy

Studio 54 DJ Booth, 1979. Bill Bernstein from the book "Disco: The Bill Bernstein Photographs" (Reel Art Press)

Studio 54 Moon and Spoon, 1978. Bill Bernstein from the book "Disco: The Bill Bernstein Photographs" (Reel Art Press)

Studio 54 and Cadillac, 1979. Bill Bernstein from the book "Disco: The Bill Bernstein Photographs" (Reel Art Press)

“Then, I guess I became known as the ball DJ. Everyone who was throwing balls at the time wanted to hire me. Soon other houses star ted to also do balls at Tracks, and I was also the DJ for those events.”

After attending an Xtravaganza ball at Tracks in 1989 and witnessing a moment of silence for one of their members, Susanne Bartsch was so moved she created the Love Ball. Held at Roseland Ballroom in Harlem in 1989, the huge event raised over two million dollars to fight AIDS, with DePino spinning next to Johnny Dynell. Other legendary balls to be held at Tracks included the House of Xtravaganza’s Red, White & Blue Ball, the Autumn in New York IV, hosted by Avis Pendavis in 1988, the House of Omni’s Obsession in 1989, the House of Africa United Nations Ball in 1988 and Paris is Burning IX, one of a series of balls hosted by Paris Dupree (from the House of Dupree, one of the original houses). Those balls gave their name to the 1990 film by Jenny Livingston, which featured extensive interviews with House Mother Angie Xtravaganza as well as showing a young Jose Xtravaganza in a vogue battle.

80

Andy Thomas

It was Tuesday nights at Tracks that the houses really brought the full intensity and creati vity of voguing from the ballrooms into the clubs of Manhattan. “The ball kids came to the Garage, but it wasn’t really a place where the voguers compe ted in a major way,” DePino says. “But at Tracks the whole voguing community came down, and that was the first club where you really saw circles and vogue battles.” Karl Xtravaganza was one of those to follow DePino to Tracks from the Garage, and he agrees with the DJ: “There were other clubs where ballroom kids would gather and battle, such as Midtown 43 and Better Days. But Tracks was the first club that put the vogue battles front-an d-center, and really catered to the ballroom kids.” DePino explains how his style of playing changed in response to the voguers: “I started to

play a much harder, gayer sound to match their voguing. They were really into the sounds with a kind of sharp stab to them, so it could be a cymbal crash, a horn or a heavy drum, just something that they could land their vogue poses on. There just happened to be quite a few records like that in the ’80s. And they would have these little 30-second sections with those sounds in. So I would take two copies of the same record and cut them up, and keep playing that part of the record over and over again.”

DePino would watch closely as the different houses competed on the floor and created his own soundtrack to the performance. “You’d get cons tant battles at Tracks with the LaBeijas battling against the Duprees or the Pendavis against the Xtravaganzas,” he recalls. “I would notice when a

81

2016 Red

Bull Music Academy

82

Andy Thomas

battle was starting, and I would play five or six records in a row that I knew they liked to vogue to. They would create their own runway and at the end of the battle the whole crowd would cheer. It was incredible, 2,000 people cheering, putting their hands up and going crazy. Even the people who weren’t really part of the vogue scene would stop and watch. It was like a mini-show within the night.”

Upstairs, where Danny Krivit split DJing time with George Morel, another type of show would be unfolding. “What also came around during the Tracks period was that they had a runway,” remembers Krivit. “I focused on creating an atmosphere, and one of the things I was focusing on was making montages of movies, and a lot of fashion footage. In doing so, this runway thing went off into a new phase. It wasn’t just voguing. There was this new, younger group of people following this video element and emulating the supermo dels.” Karl Xtravaganza recalls that “Upstairs was more of a lounge area with a pool table, bar and smaller dancefloor and video screens. They would screen runway shows on the video screens – which was just perfect as a backdrop for kids imitating poses from fashion magazines and doing their runway walk across the dancefloor.”

The ultimate anthem of the pre-1990 “Old Way” voguers was MFSB’s “Love Is the Message.” In an interview for Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York City 1989-92, Muhammad Omni of the House of Omni explained how “the jazz breaks fluctuated so much you could find a lot of moves to do off that song.” Other big Old Way tracks DePino remembers spinning included “Ooh, I Love It (Love Break) (Shep Pettibone Mix)” by the Salsoul Orchestra, George Kranz’s “Din Daa Daa,” “Let’s Go (Don’t U Want Some More)” by Fast Eddie, The Todd Terry Project’s “Bango (To The Batmobile),” Royal House’s “Can You Party” and Ralphi Rosario’s “You Used to Hold Me.” “I would say my style was very high-intensity,” says DePino. “We used to open at 8 until 6. I would keep it uptempo all night until around 4, when I would go downtempo for an hour or so, playing classics. Then for the last hour I would pump it up again.”

By the late 1980s, the first tailor-made vogue tracks appeared, including DePino’s own “Elements of Vogue,” co-produced with fellow House of Xtravaganza members David Ian Xtravaganza and Johnny Dynell. “Among the Houses that compete in, or ‘walk’ these balls, the six-year-old Latin House of Xtravaganza is feared and respected for its thousand trophies and fierce family pride,” wrote Chi Chi Valenti in the sleevenotes to the 1989 release. “House MC David Ian Xtravaganza is but one of a galaxy of stars, from house parent Mother Angie and Father David to Jose Xtravaganza.” Later to become House Father of Xtravaganza, Jose would become one of the most famous voguers of all time when he appeared in the video

Red Bull Music Academy

83

Daryl, Richie Mercado, Leslie Macayza, Judi MeMuro, Duglas Coleman and John Howard. Photograph from the closing party of Paradise Garage. New York, September 26, 1987. By: Tina Paul

2016

for Madonna’s 1990 hit single “Vogue” and on her Blond Ambition world tour with Luis Xtravaganza.

After “Elements of Vogue,” DePino pro duced a handful of tracks, including Danny Xtravaganza’s “Love the Life You Live” on Nu Groove. “I was offered a lot but only did a few things, because I knew where my strength was, and that was in playing to the crowd and making people have fun,” he says. “At the time, people were putting DJs into the studio whether they knew what they were doing or not. And I didn’t want to do that. But all those years going into the studio with Larry, I do regret never really paying attention to what he was doing. I do kick myself in the ass for not sitting there and learning, because I had a great teacher there.”