Whispers of Morality:

The Influence of Ethics in Architecture throughout History

Design Research (M) 2024 - Stage 2 Submission

Group 3.1 – Muneeb Khatri & Marco (Byungjin) Kim

‘Design always presents itself as serving the human but its real ambition is to redesign the human. The history of design is therefore a history of evolving conceptions of the human. To talk about design is to talk about the state of our species.’ (Columnia and Wigley, 2016)

‘The promise of good design is to produce good humans.’ (Columnia and Wigley, 2016)

2

Introduction

Ethical Values are the Driving Factors that Shape the Design of Modern Architecture

Ethical Architecture Leads to More Positive Behaviour of Users than Unethical Architecture

Conclusion

Bibliography

3 Contents Summary 4 5 6 10 14 15

Summary

The relationship between architecture and human experience is an important concept for all architects to design a successful space. Within the practising field, there is an ongoing debate between prioritising ethical design of architecture against the aesthetics of architecture. We argue that ethical values are the driving factors that shape the design of a modern building. We also argue that ethical architecture produces positive behaviours between users and is capable of correcting a person’s behaviour. This leads to the conclusion that ethical values are indispensable, and ethically designed architecture will naturally attract aesthetic beauty and produce good people from within.

100

4

words

Introduction

Architecture is an artistic discipline which shapes our built environment and influences human behaviour, societal values, and emotional wellbeing. The ethical dimension of architecture, which intertwines with its aesthetic and functional aspects, is critical in understanding its influence on social function. This article aims to explore the relationship between ethics and architecture. The ethical influence of architecture is evident in how buildings shape human behaviour and emotions. This influence builds on from Chapter 7 of the book ‘Are We Human’ by extending the argument that ‘good design aims to produce good humans’.1

Historically, architecture has been primarily associated with aesthetics, focusing on beauty, and form. To the notion form follows function. However, as Maurice Lagueux and Karsten Harries argue, the ethical

responsibilities of architects extend beyond only aesthetics.2 They argue that architectural ethics are internal to the discipline, requiring solutions that address both aesthetic and ethical challenges although internally as will be explored. This perspective highlights the unique position of architecture in creating environments that foster positive and successful communities, enhance well-being, and reflect societal values. Also, by exploring how ethical and aesthetic considerations are connected uniquely, why it is crucial for architects to embrace this integrated approach and how it supports the notion that good designs do in fact assist in inducing good behaviour in humans.

1. Beatrize Colomina and Mark Wigley, 2016, Are we Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design. Zürich: Lars Mülller Publishers. Lucas, Ray. 2016, Research Methods for Architecture. London: Laurence King Publishing.

2. Maurice Lagueux, 2004, ‘Philosophical Forum, Ethics vs. Aesthetics in Architecture’, PhD thesis Dissertation, University of Montreal, 1-20.

217 words

5

Figure 1 - Architect’s Dilenma between Aesthetics vs Ethics (Koh, 2017)

Ethical Values are the Driving Factors that Shape the Design of Modern Architecture

History of Ethics

Philosophy of ethics was questioned and articulated further by Greek philosopher Aristotle. who emphasised good life and its connection on virtue of character. 3 Rather than relying on strict laws, Aristotle’s theory of ethics relied upon taking the right courses of action in a particular situation.4 Aristotle’s theory of ethics then evolved into systems known as utilitarianism and deontology. According to utilitarianism, the right course of action would benefit more people or society.5 Jeremy Bentham (17481832), considered as the father of utilitarianism summarises the principle as ‘greatest pleasure for the greatest number’.6 The significance of utilitarianism is that it is often used to formulate laws and legislations to serve the state to benefit society.7 Roots of utilitarian architecture started in Bauhaus School by Walter Gropius in 1919, stressing the importance of mass production, finding efficient and cost-effective methods of producing buildings for society was comparable to Bentham’s utilitarian mindset.8 Contrasting to the consequential type of ethics of utilitarianism, deontology states, everyone has a moral obligation to act in a certain way, and an action is considered righteous if it honors the obligation.9 German philosopher Immanuel Kant was associated with the principles of deontology, subjecting types of actions rather than incidental actions, therefore it was often used in codes of conduct for architects to ensure the correct and professional practice of the profession.10 302 words

302 words

3. Gisela Striker, 1987, Greek Ethics and Moral Theory, The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, https://tannerlectures.utah.edu/_resources/documents/a-to-z/s/Striker88.pdf.

4. Striker, 1987.

5. Muel Kaptein and Johan Wempe, “Three General Theories of Ethics and the Integrative Role of Integrity Theory”, SSRN Electronic Journal, 54-102 (January 2003): 1-37.

6. Kaptein and Wempe, 2003, 1-37.

7. Kaptein and Wempe, 2003, 1-37.

8. Geoffrey Sayre-McCord, “Hume and the Bauhaus theory of ethics” , Midwest Studies in Philosophy 20 (1996): 280-298.

9. Kaptein and Wempe, 2003, 11.

10. Kaptein and Wempe, 2003, 13.

6

Figure 2 - Symbolising Architecture is for Humans i.e by us, for us (Eyck, 1959)

Ethical Dimensions in Architecture

Research by Maurice Lagueux highlights the interdependence of ethics and architecture, explaining why architects must solve ethical problems internally, focusing on aesthetic solutions applicable to ethical challenges rather than seeking guidance from philosophical ethics. Karsten Harries, The Ethical Function of Architecture contributed to this topic, argues that architecture’s highest function is to provide authentic dwelling and create conditions for community life, making its ethical function crucial for success.11 Unlike other arts, architecture’s success is intertwined with solving ethical problems due to its impact on human behaviour and values. Ethical problems in architecture are internal, requiring solutions that address both aesthetic and ethical challenges, highlighting the close relation between ethical and aesthetic values in architectural works. In a chapter entitled ‘The Ethical fallacy’ of his classic book The Architecture of Humanism, denounced the Ruskinian moralisation of architectural choices, which, according to him, should remain purely aesthetic and technical.12 Now it is not a rejection of ethical considerations as he concludes his chapter on the ethical fallacy by strongly emphasised the close relation between ethical and aesthetic values: ‘There is, in fact, a true, not a false, analogy between ethical and aesthetic values: the correspondence between them may even amount to an identity’.13 It is argued whether there is room for ethics in architecture other than its internal requirements. Otherwise, how would it be possible to distinguish architecture from engineering?14

Architecture has the capacity to induce people with varied emotions which make them more or less hopeful, empowered, communicative,

tranquil, and potentially democratic, or depressing, oppressed, sad, revolting, and violent.15 This hints that the building of an architect can influence human behaviour and values. Adding to this, a painting or literature may be considered a masterpiece of sublime beauty even if it provokes discomfort to its viewers, however a building may hardly be considered beautiful if it induces the very same result.

To illustrate this further, The Holocaust Museum in Washington by James Ingo Freed and the Jewish Museum in Berlin by Daniel Libeskind were recognised for their depressing and sad effects, but this is the exact effect that it was deemed morally acceptable for this particular architectural structure.16 Now if these museums were built with a different approach, of providing a comfortable experience for their users, the designers would come under fire for failing to evoke the acceptable moral feelings. There is a grey line in which architecture poses as an ethical debate, although it is necessary that ethical problems are the internal part of the issues that an architect must solve in order to achieve the success of their art aesthetically.

11. Maurice Lagueux, 2004, 15-16

12. Scott, Geoffrey, 1974, The Architecture of Humanism. A Study in the History of Taste, (London, W. W. Norton & co) 115-125

13. Scott, Geoffrey, 1974, 125

14. Maurice Lagueux, 2004, 14-15

15. Maurice Lagueux, 2004, 6-8

16. Maurice Lagueux, 2004, 6-9

7

This is the first time that discussions on ethics and aesthetics in the practising field have become an issue, since the 19th century.17 Essentially, it is significant of meeting the users wants and needs in respect to the moral and aesthetic driven standards. Medieval architects were interested in creating designs that for the purpose of visual pleasure which to them meant ethical. John Ruskin, an influential philosopher, expressed the notion of what is beautiful and what is good through a quasi-identity of the two values by adding another, the truth.18 Ruskin was soulfully faithful to the truth because deception is a sin. An architect that purposely hides structural supports to hint that a building stands by itself when it does not, or fake supports without a role. Ends up deceiving honest people, and discredits architecture.19 Hence, mediaeval, and baroque architects are harshly critiqued as it deceives people on purpose. For Ruskin, these aesthetic values could not be seperated from ethical values due to their idea that architecture was transforming their time of their world in which their social community evolved. 20

Following on a revelation in the early 1920s when infleunce of socialism and modernist architects were inspired by the calling to improve the social world. In recognition of famous architects, Mies Van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and Gropeus became of service that architects were bestowed upon a duty to improve through better buildings of life of its inhabitants.21 It was evident that improvement of social life ‘through the structure of the house’ to be seen clearly with the naked eye, as it is of ethical progression. Now, to the 20th century were modernist architects claiming their position to the development of architecture adapted to their time was a moral duty. This rejection of traditional architecture was a notion to clean the architectural world and improve the life of its users ultimately.22 Watkin states: ‘A building must be beautiful when seen from outside if it reflects all these qualities. The architect who achieves this task becomes

a creator of an ethical and social character; the people who use the building for any purpose, are brought to a better behaviour in their mutual dealings and relationship with each other. (Watkin, 1984, p. 40;)’23

888 words

17. Maurice Lagueux, 2004, 9-10

18. John Ruskin, 1903, The Seven Lamps Of Architecture Volume III, (London, New York, Longmans Green and Co) 20-49 https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content assets/ documents/ruskin/8SevenLampsofArchitecture.pdf

19. John Ruskin, 1903, 20-34

20. Maurice Lagueux, 2004, 10-14

21. Maurice Lagueux, 2004, 11-13

22. Maurice Lagueux, 2004, 10-15

23. Maurice Lagueux, 2004, 12

8

Figure 3 - Amalagation of buildings hiding the core structure i.e aesthetic pleasure only (Vivas, 2022)

Ethical Duties of an Architect

The function of architecture is experienced with the moving body, like when one approaches a building, to walk by it. Or around it? perhaps enter it and walk down the hall or aisle, up some stairs, maybe open the door to different spaces, open a window and look outside. Michael Fried, says it allows observers to recognise that they themselves are establishing relationships as they approach the object from various positions under different light and spatial context.24 The example follows the church of its natural symbolism of light, that of which is intertwined with space giving meaning to function.25 The role of an architect involves obligations not just of technical competence. The architect addresses clients’ needs through the built environment and helps protects the user. It is to resolve demands and take on ethical dilemmas of the building by mediating between public and private demands. To negotiate a balance between authentic public concerns and the private needs is at the soul of the architect’s duty.26

The expression of the Zeitgeist, of the “spirit of the age” came from the notion that said architects had not taken advantage of modern construction techniques. I.e. the use of steel and concrete structures, glass panels. This allows for free planning, green roofs, and unusual shapes. With time it was a lazy refusal of one’s duty to find the best ethical and aesthetic solutions to the problems raised by modern living. It was tempting to draw the conclusion that modernist architects had an ethical obligation to ensure that their designs complied with the demands of the time, if their moral mission was to improve people’s lives through innovations that enabled the creation of a built environment that kept pace with the development of other spheres of human existence.27

Craig Delancy, a professor in the university of New York, says, the assets obtained from the topographical “footprint” of the population envisaged to use the building would comprise a more comprehensive metric.28 Concerns include the source of the material, its cost and renewability, the building’s lifespan in relation to its cost, whether the design is appropriate for the site

and surroundings.29 This can follow an architect’s duty to ensure the safety of its ecological habitat in which the building resides, focusing on maximising ecological benefits, for example, a tree is an ideal structure of nature. The architect will also want to design so that the health of the local environment as whole is improved.

In a list format, there is the practising architect’s duty of 21st century: to begin there is the framework and goals of the brief, to inform and determine the site & location of the building, to resolve the organisation of space and relations of activities and needs, to advise and make decision of the selection of materials, to advise and coordinate a consult with interested peoples and affected communities.30 Then comes the tendering, negotiation and establishment of the construction and legislation contract, then to finally observe the construction of the building ensuring its compliance with the design documentation intentions.31

629 words

24. Karsten Harries, 1998, The Ethical Function of Architecture, (Massachusetts, New Directions Publishing Corp) 1-26, 214-222. https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=1hCo61dbB6QC&oi=fnd&pg= PR8&dq=how+ethics+in+architecture+has+evolved+over+time&ots=lWvS1dm_dX&sig=ZA65WGSNR 7eXhJpurLQoamUravY#v=snippet&q=michael%20fried&f=false

25. Karsten Harries, 1998, 1-30

26. Tom Spector, 2001, The Ethical Architect: The Dilemma of Contemporary Practice (New York, Published Princeton Architectural Press) 3-20. https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=EZ_9YllZjC8C& oi=fnd&pg=PT4&dq=ethical+duties+of+an+architect&ots=pM23k3VS6r&sig=4MrlWBfJi5bFUCQIzcK 2oVb6iAg#v=onepage&q=mediating%20between%20public&f=false

27. Maurice Lagueux, 2004, 11-15

28. Craig Delancey, 2004, ‘Architecture Can Save The World: Building and Environmental Ethics’, published Thesis, State University of New York at Oswego, 2-5 https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/228037399_Architecture_Can_Save_the_World_Building_and_Environmental_Ethics

29. Craig Delancey, 2004, 4-5

30. Jessamine Fraser, Andrew B, Megan B, Charles W, 2023, ‘Ethics, Care, and he Architect’s Responsibility to Society and Environment’, published PhD Research Paper, University of Technology New Zealand, 2-5 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374375627_Ethics_Care_and_the_Architect's_Responsibility_ to_Society_and_Environment

31. Nicholas Ray, 2005, Architecture and Its Ethical Dilemmas, (New York, CRC Press LLC) 4-6, 9-15, 3944, 133-143 https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/adelaide/reader.action?docID=308698

9

Ethical Architecture Produces More Positive Behaviour of Users than Unethical Architecture

Traditional Attemps of Correcting Behaviour Through Incarceration

During the early 20th century, Erving Goffman, considered by some as the most influential American sociologist, conceptualised prison as total institutions that take full control of an inmates’ individual life.32 It emphasised on strictness and absolute separation from the outside world. Subsequently, French philosopher Michel Foucault, who addresses the relationship between power and knowledge, suggested surveillance has become a part of everyday life in the Western society from the 20th century and in prisons.33 It has become a form of power, a trap of visibility, that can control human behaviour.34

During the mid-20th century, the American philosophical approach to incarceration and corrective behaviour focused on deterrence, incapacitation, and retribution.35 Deterrence approach utilises the fear of punishment and pain to reduce or prevent wrongful activity, provoking the desire to avoid harsh punishments.36 Incapacitation is often appealed with habitual offenders, to detain them on long term sentences which deplete the system’s resources, ultimately due to the inability to achieve rehabilitation, resulting in a system accomplishing only incapacitation, rendering the individual stricken.37 Retribution is the philosophy that follows The Bible passage ‘And thine eye for eye, tooth for tooth’, where the punishment is motivated by justice.38 Retribution system implies citizens enter a societal contract with the state for protection, and if the societal contract is broken, the state has the right to impose punishment.39 These traditional methods of correcting behaviour through incarceration was used for traditional prison architecture and was often considered unethical due to its harsh conditions and failed to reduce reincarceration rates.40

348 words

32. Erving Goffman, 1962, Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates (New York: Anchor Books) 4.

33. Michel Foucault, 1995, Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison (New York: Vintage Books) 200.

34. Foucault, 1995, 200.

35. Rachel O’Connor, 2014, ‘The United States Prison System: A Comparative Analysis’ published PhD thesis Dissertation, University of South Florida, 3-10.

36. O’Connor, 2014, 3-10.

37. O’Connor, 2014, 3-10.

38. O’Connor, 2014, 3-10.

39. O’Connor, 2014, 6.

40. Erik Olin Wright, 1973, San Quentin Prison: A Portrait of Contradictions (New York: Harper Colophon Books) 57,70,71,72.

Figure 4 - Inside San Quentin Prison, Traditional Model for Correcting Behaviour. (Chan, 2020)

10

Ethical Architecture and its Relationship with Human Well-being and Behaviour

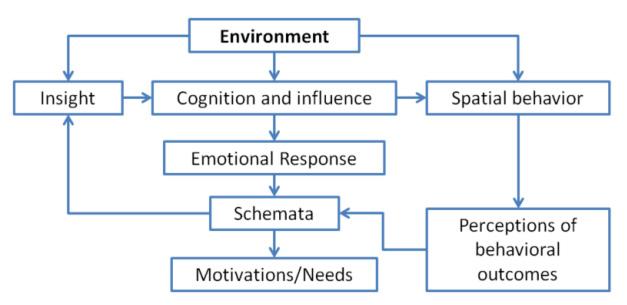

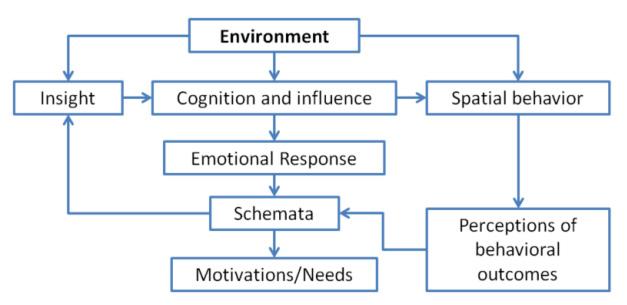

Moneim stated that natural elements dictate the human experience within architecture and pointed out that user’s behaviour, thoughts, and feelings can be influenced by the building environment, suggesting why the traditional ways of correcting behavour through incarceration was not effective.41 He shows that the fundamentals of human behaviour first start from the environment it is in, branching into cognitive influence, emotional response, which leads to motivation and action.42

Professor Philippe from McGill University also stated that given a substantial proportion of average person’s life is spent indoors, it is imperative for architects to understand the architectural features and design elements that have direct correlation with the function, health, wellbeing, and behaviour of human beings.43 Ethics and moral obligations of modern architects may lead to creation of buildings with quality level of comfort for the users.44 Margarete claimed that this shortcoming of design elements can often cause psychosomatic symptoms as well as physical discomfort, leading to undesirable

behaviours.45 This correlation was demonstrated through the recent COVID 19 pandemics, where many employees were forced to work from home. Consequently, there was a rapid increase in mental illness such as depression, anxiety, stress, and abnormal behaviours.46 This was coherent with the study findings by Paulina, where inferior and ill-conceived factors of architectural design stimulate psychosomatic illness, encourage exhaustion and physical anxiety, leading to aggressive behaviour.47 As Winston Churchill stated that ‘We shape our buildings, and afterwards our building shape us’.48

Philip’s study of architectural stimuli on human psychology and physiology found that visual stimuli such as light have direct correlation with human physiology and biological responses of the body.49 Research found that sufficient exposure to light was crucial for well-being, as it improved sleep efficiency during night, reduced symptoms of seasonal affective disorders, and improved vitality and mental health.50

41. Sahar Alharbi, Hind Basaad, “The Impact of Indoor, Outdoor and Urban Architecture on Human Psychology,” Civil Engineering and Architecture, vol. 10, No. 3A, 132–137 (2022) DOI: 10.13189/ cea.2022.101317.

42. Alharbi and Bassaad, 2022, 132-137.

43. Philippe St-Jean, Osborne Grant Clark and Michael Jemtrud, “A review of the effects of architectural stsimuli on human psychology and physiology,” Building and Environment, vol. 219 (2022) DOI: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109182.

44. St-Jean et al, 2022.

45. Alharbi and Basaad, 2022, 133.

46. Alharbi and Basaad, 2022, 133.

47. Paulina Šujanová, Monika Rychtáriková, Tiago Sotto Mayor, and Aaffan Hyder, “A healthy, energyefficient and comfortable indoor environment”, A review, Energies, Vol. 12, No, 8 (2019) DOI: 10.3390/ en12081414

48. Deborah Winslow, “We Shape Our Buildings and Afterwards Our Buildings Shape Us’: Interpreting Architectural Evolution in a Sinhalese Village”, Alternative Pathways to Complexity: A Collection of Essays on Architecture, Economics, Power, and Cross-Cultural Analysis, 239–56. University Press of Colorado (2016) http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1hch803.16.

49. St-Jean et al, 2022.

50. St-Jean et al, 2022.

11

Figure 5 - Diagram: Fundamentals of Human Behaviour through the Environment (Alharbi, 2022)

In addition, evidence suggests that light has a direct influence on cognitive performance and mood, which dictates the behaviour of an individual, data showing as little as 20 minutes of exposure to lights can improve a person’s mood and cognitive function throughout the day.51

Color is another element that directly influences user well-being. According to Coburn et al, people are likely to experience a bad mood and higher level of stress when being inside a room painted in dull color.52 Although it is important to note that not every individual reacts the same way towards a particular visual stimulus, as one person may prefer what the other does not, which could have an adverse effect.53 The effect of color is mostly correlated with the association people have with specific colors that influence their psychological state and behaviour. Study results from Valdez and Mehrabian showed bright and lighter colors facilitated a more peaceful, pleasant, and less dominating atmosphere for the occupants.54

Spatial configuration was also found to influence individual well-being and behaviour. Spacious rooms with larger windows and openings that allowed better connectivity between indoor and outdoor are more likely to provide positive moods, emotions, and physiological effects.55 Contrastingly, enclosed spaces often triggered the cingulate gyrus of occupant’s brain, which stimulates fear and stress. As a result, avoidance behaviours were shown in enclosed spaces, while this could also trigger a sense of dominating behaviours by others.56

Connection with nature has not only shown to improve physical and mental wellbeing, but also helps to reduce criminal behaviours. Numerous research has found that views of nature were correlated with improved recovery and pain relief for many patients in the hospital.57 In addition, connection with nature also improves blood pressure, anxiety, fatigue and eases a positive emotional state.58 Surprisingly, a recent study from Human Environment Research Laboratory at the University of Illanois revealed that increases in greeneries were associated with

lower violence, aggression, and criminal behaviours.59 According to S. Kaplan, this is likely due to lowering of mental fatigue by nature, as one outcome of mental fatigue is outburst of anger and violence.60

The architectural elements affecting human well-being and behaviours laid down by many including Philip’s study is parallel to the ethical duties of an architect. This accumulation of sources indicates that an architect’s ethical duties often lead to influencing the user’s well-being and behaviours. Hence, these sources suggests that ethically designed architecture leads to a positive change in human well-being and behaviour.

1033 words

51. Sarah Laxhmi Chellappa, Gordijn Marijke, and Christian Cajochen, “Can light make us bright? Effects of light on cognition and sleep”, Progress in brain research 190 (2011): 119-133.

52. Semiha Ergan, Ahmed Radwan, Zhengbo Zou, Hua-an Tseng, and Xue Han, “Quantifying human experience in architectural spaces with integrated virtual reality and body sensor networks”, Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering, vol. 33, No. 2 (2019) DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)CP.1943-5487.0000812

53. Ergan et al, 2011, 119-133.

54. Patricia Valdez, and Albert Mehrabian, “Effects of color on emotions”, Journal of experimental psychology: General 123, no. 4 (1994): 394.

55. Ergan et al, 2019.

56. Oshin Vartanian et al, “Architectural design and the brain: Effects of ceiling height and perceived enclosure on beauty judgments and approach-avoidance decisions”, Journal of environmental psychology 41 (2015): 10-18. DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.11.006

57. St-Jean et al, 2022.

58. St-Jean et al, 2022.

59. Frances E Kuo and William C. Sullivan, “Environment and crime in the inner city: Does vegetation reduce crime?”, Environment and behavior 33, no. 3 (2001): 343-367.

60. Kuo and Sullivan, 2001, 343-367.

12

Case Study - World’s Most Ethical Prison (Halden Prison)

During the early 21st century, Norwegian penal philosophy focused on rehabilitating inmates through ethical and humane treatment and a ‘guiding principle of normality’. Norwegians believe in restorative justice and that prison’s sole punishment is the loss of liberty, recreating a life outside of prison, allowing the offenders to remedy their behaviour on their own initiatives.61 Halden prison, a 75-acre facility strayed away from the traditional static security and focuses on dynamic security measures which means no bars, inmates have freedom of movement, kitchens fully equipped with sharp objects, and friendships between guards, which is contrasting with traditional prison designs.62

dense forest, which helps to create a peaceful and serene atmosphere all while being a maximum security ‘campus’.64 The buildings are made of fired brick, untreated wood, and galvanized steel with large windows while the open spaces are similar to a university campus rather than a prison. The spatial configuration of the prison design has incorporated a biophilic approach with natural light infiltration, materials and patterns that evoke the natural world, views of the outdoors through the windows, and opportunities for direct contact with nature. This is to promote psychological wellbeing, reduce stress and improve cognitive functioning. Its design is to reflect a humane prison, one where the architecture isn’t part of the punishment.65 Despite costing an average of 3 times more for each prisoner compared to traditional prisons, its reduction in recidivism resulted in a lower overall cost, proving ethically designed architecture are more effective in correcting behaviour.66

358 words

61. Ryan Berger, 2016, ‘Kriminalomsorgen: A Look at the World’s Most Humane Prison System in Norway’ Dissertation thesis, Duke University, School of Law, 1-20.

62. Lilli Fisher, 2016, ‘Prison Nature Social Structure’, blog, https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/ blog/2016/08/prison-nature-social-structure/, accessed 2nd April 2024.

63. Yvonne Jewkes, Dominique M, 2022, The Palgrave Handbook of Prison Design (Switzerland, Palgrave Macmillan) 679-695.

64. Jewkes, 2022, 679-695.

65. Jewkes, 2022, 679-689.

66. Berger, 2016, 18-20.

According to Berit Johnsen, prison design in Nordic countries also focuses on green outdoor spaces more than prison design in Anglophone countries.63 Halden is a collection of buildings contained inside a tall curving wall, situated within a natural landscape, surrounded by a

13

Figure 6 - Halden Prison, The Ethical Model for Correcting Behaviour. (Gordon, 2019)

Conclusion

The article consensus that the connection between ethics and aesthetics in architecture have determined over time a crucial requirement in creating spaces that enhance human well-being and foster an emotional value to its users. This notion is explored by Maurice Lagueux and Karsten Harries that the ethical challenges are internal to the practice requiring solutions to integrate aesthetic beauty with moral responsibility. Adding to the conclusion, that ethical considerations are indispensable in architecture, making sure they are not only pleasing to look at, therefore ethical values are the driving factor that shapes the built environment today.

Ethical architecture has shown to have direct correlation with human well-being and behaviour. Traditional attempts at correcting behaviour through unethical and harsh architecture that deters, incapacitates and retributes was shown to have failed. With ethical architecture designs that consider elements such as natural light exposure, colors, spacious configurations, and views of nature were shown to have affected the user’s moods and behaviour. This theory was shown through a case study of Norway’ss most ethical and humane prison and comparison of its recidivism rates with traditional architectures that are considered unethical.

186 words

14

Bibliography & Image Credits

1. Adamu Chan, 2020, ‘The View From Inside San Quentin State Prison’, https://www.mttamcollege.edu/slate-the-view-from-inside-san-quentin-state-prison/.

2. Aldo Van Eyck, Otterlo Circles Diagram, 1959, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Aldo-van-Eyck-Otterlo-Circles-Diagram-1959-Aldo-van-Eyck-Writings-Francis-Strauven_ fig1_304996602 Accessed 30th May 2024.

3. Alex Gordon, 2019, ‘Norway’s Humane Prisons’, https://prwolfprints.com/2019/09/norways-humane-prisons/.

4. Alharbi Sahar & Basaad Hind. “The Impact of Indoor, Outdoor and Urban Architecture on Human Psychology”.

5. Beatrize Colomina and Mark Wigley. 2016. Are we Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design. Zürich: Lars Mülller Publishers. Lucas, Ray. 2016. Research Methods for Architecture. London: Laurence King Publishing.

6. Berger Ryan, 2016, Kriminalomsorgen: A Look at the World’s Most Humane Prison System in Norway. Dissertation thesis Duke University. School of Law. 1-20.

7. Chellappa Sarah Laxhmi, Marijke Gordijn, and Cajochen Christian. “Can light make us bright? Effects of light on cognition and sleep”. Progress in brain research 190 (2011): 119-133.

8. Civil Engineering and Architecture, vol. 10, No. 3A, 132–137 (2022) DOI: 10.13189/cea.2022.101317.

9. Delancey, C. (2004). “Architecture Can Save The World: Building and Environmental Ethics”, Published Thesis Dissertation. State University of New York at Oswego. 2-5.

10. Diego Vivas, Brutalism in Lima: Ethical and Aesthetic Essays, 2022, https://www.archdaily.com/983453/brutalism-in-lima-ethical-and-aesthetic-essays Accessed 30th May 2024.

11. Ergan Semiha, Radwan Ahmed, Zou Zhengbo, Tseng Hua-an, and Han Xue. “Quantifying human experience in architectural spaces with integrated virtual reality and body sensor networks”. Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering, vol. 33, No. 2 (2019) DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)CP.1943-5487.0000812.

12. Fisher Lilli. 2016. Prison Nature Social Structure. Blog. https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/blog/2016/08/prison-nature-social-structure/. accessed 30 May 2024.

13. Foucault Michel. 1995, Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. New York: Vintage Books.

14. Foucault, M. (1995). Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. New York: Vintage Books.

15. Grönegräs Maximilian, ‘International Differences in Prison Architecture: What the United States Can Learn from Germany’, MaRBLe: 2, vol 4 (2019) 85.

16. Harries, K. (1998). The Ethical Function of Architecture, (Massachusetts, New Directions Publishing Corp) 1-26, 214-222.

17. Jessamine F. Andrew B, Megan B, Charles W. (2023). ‘Ethics, Care, and he Architect’s Responsibility to Society and Environment’, published PhD Research Paper, University of Technology New Zealand, 2-5.

18. Jewkes Yvonne. 2022. The Palgrave Handbook of Prison Design (Switzerland, Palgrave Macmillan) 679-695.

19. Kaptein Muel and Wempe Johan. “Three General Theories of Ethics and the Integrative Role of Integrity Theory”. SSRN Electronic Journal, 54-102 (January 2003): 1-37. https://www. researchgate.net/profile/Muel-Kaptein/publication/330683871_Three_General_Theories_of_Ethics_and_the_Integrative_Role_of_Integrity_Theory/links/65c74cee79007454976c38c6/ Three-General-Theories-of-Ethics-and-the-Integrative-Role-of-Integrity-Theory.pdf.

20. Kuo Frances and Sullivan William. “Environment and crime in the inner city: Does vegetation reduce crime?”. Environment and behavior 33, no. 3 (2001): 343-367.

21. Maurice, L. (2004). ‘Philosophical Forum, Ethics vs. Aesthetics in Architecture’, PhD thesis Dissertation, University of Montreal, 1-20.

22. O’Connor Rachel. 2014. The United States Prison System: A Comparative Analysis. published PhD thesis Dissertation. University of South Florida.

23. Raphael Koh, Gallery Representation, 2017, https://medium.com/profolio/improve-your-gallery-game-f34c84a0fd5c Accessed 30th May 2024

24. Ray, N. (2005). Architecture and Its Ethical Dilemmas, (New York, CRC Press LLC) 4-6, 9-15, 39-44, 133-143.

25. Ruskin, J. (1903). The Seven Lamps Of Architecture Volume III, (London, New York, Longmans Green and Co) 20-49.

26. Sayre-McCord Geoffrey. “Hume and the Bauhaus theory of ethics”, Midwest Studies in Philosophy 20 (1996): 280-298.

27. Scott, G. (1974). The Architecture of Humanism. A Study in the History of Taste, (London, W. W. Norton & co) 115-125.

28. Spector, T. (2001). The Ethical Architect: The Dilemma of Contemporary Practice (New York, Published Princeton Architectural Press) 3-20.

29. Šujanová Paulina, Rychtáriková Monika, Mayor Tiago Sotto, and Hyder Aaffan. “A healthy, energy-efficient and comfortable indoor environment”. A review, Energies, Vol. 12, No, 8 (2019) DOI: 10.3390/en12081414.

30. Valdez Patricia, and Mehrabian Albert. “Effects of color on emotions”. Journal of experimental psychology: General 123, no. 4 (1994): 394.

31. Winslow Deborah. “We Shape Our Buildings and Afterwards Our Buildings Shape Us’: Interpreting Architectural Evolution in a Sinhalese Village”. Alternative Pathways to Complexity: A Collection of Essays on Architecture, Economics, Power, and Cross-Cultural Analysis, 239–56. University Press of Colorado (2016) http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1hch803.16.

32. Wright Erik Olin. 1973. San Quentin Prison: A Portrait of Contradictions (New York: Harper Colophon Books).

33. Zifferblatt M. Steven, ‘Architecture and Human Behavior: Toward Increased Understanding of a Functional Relationship’, Education Technology: 12, vol 8 (1972) 54-57.

15

Checklist:

Adhered to the word limit in the summary and the article.

Inserted the main quote by C+W on the inside of the front cover.

Followed the 5-sentence template in writing of the summary.

Inserted word count of the summary.

Inserted word count of the article.

Adhered to the prescribed number of spreads.

Adhered to the prescribed number of images.

Researched and cited the required number of sources.

Uploaded PDF file on issuu.com and provided active link on the from cover.

Inserted the checklist on the back cover.

Uploaded final PDF file on MyUni and Box.

Uploaded final Black+Blue word file on MyUni and Box.

Student 1 Student 2

Name: Muneeb Ahmed Khatri - a1768469

Name: Byungjin (Marco) Kim - a1706266