Società Oftalmologi Universitari

President

Leonardo Mastropasqua

Società Oftalmologi Universitari

President

Leonardo Mastropasqua

Board Members

Aragona Pasquale – Bonini Stefano – Boscia Francesco – Donati Simone Fontana Luigi – Gandolfi Stefano – Manni Gianluca – Marchini Giorgio

Mastropasqua Rodolfo – Miglior Stefano – Nardi Marco – Nicolò Massimo

Nubile Mario – Nucci Carlo – Nucci Paolo – Simonelli Francesca

Staurenghi Giovanni – Tognetto Daniele – Vinciguerra Paolo

Chapter Editors

G. Alessio

T. Avitabile

F. Bandello

M.A.Blasi

F. Boscia

P. Carpineto

A. Carta

P. Lanzetta

L. Mastropasqua

R. Mastropasqua

E. Midena

M. Nicolò

P. Nucci

S. Rizzo

F. Simonelli

G. Staurenghi

G. Virgili

Fabiano Gruppo Editoriale

© Copyright 2024

Publisher:

FGE srl - Fabiano Gruppo Editoriale

Editorial office: Strada 4 Milano Fiori, Palazzo Q7 – 20089 Rozzano (MI) – Italy Ph. +39 0141 1706694 – info@fgeditore.it – www.fgeditore.it

Printing: FGE srl - Fabiano Gruppo Editoriale

This publication was made possible thanks to the unconditional contribution of:

The Authors and the Editor decline any responsability for any errors in the text. All rights reserved. Reproduction of this book - total or partial - is strictly forbidden.

ISBN 978-88-31256-70-4

Printed in: December 2024 Sy9_25

It is with great pleasure and honor that I present, on behalf of the Board Members, the first edition of the Ophthalmology Up-To-Date Textbook edited by the University Italian Society of Ophthalmology (SOU). The aspiration of this book is to be a repository of knowledge and provide doctors with an up-to-date, organized and systematic approach to the visual system. This opera is thought to be useful in the daily practice of any ophthalmologist, but also to act as a guide for the general learning of the young ophthalmologists and trainees. The text is supported by a rich iconography with essential bibliography for further insights, and each chapter provides both basic descriptions and more in-detail knowledge in the various topics treated throughout the book. This publication is divided into three compact but complete volumes that will covering the majority of routine ophthalmological practice. In this first volume, dedicated to the dissertation of clinical pathologies, the different sections will be focused on the “Basics in ophthalmology” (from the anatomy of the eye to clinical refraction), “Diseases of the external eye and orbit”, “Pathologies of the anterior segment of the eye” and “Glaucoma and diseases of the uveal tract”. In the following volume the “diseases affecting the posterior segment of the eye”, “pediatric-and neuro-ophthalmology”, “genetic diseases, ocular oncology and correlations between systemic disorders and the eye” will be covered. The last volume of the opera will be dedicated to a complete description of “Instrumental diagnosis, imaging and technology in ophthalmology” and will contain specific and vast sections dedicated to therapeutics including “Laser and surgical procedures in ophthalmology”. It is belief of all the Authors, whom I personally thank for the great effort and work done in producing the chapters of this textbook, that these three volumes can provide an excellent study basis for ophthalmologists in training, (and also for the most experienced doctors) integrating their learning and skills during the clinical work and the surgical experiences, always suggesting to update their knowledge with the essential study of recent research papers and review monographs. I hope that the readers will enjoy and be stimulated by our ophthalmology textbook.

Section 1 Basics in ophthalmology

Section 2 Diseases of the external eye and orbit

Section 3 Diseases of the anterior segment of the eye

Section 4 Glaucoma and diseases of the uveal tract

Section 5 Vitreous and retina

Section 6 Neuro-ophthalmology, pediatrics and injuries

Section 7 Genetic diseases and neoplasia of the eye

Volume 3 Next publishing

Section 8 Instrumental diagnosis, imaging and technology in ophthalmology

Section 9 Ocular therapeutics, lasers and surgery in ophthalmology

Agbeanda Aharrh-Gnama

Ophthalmology Clinic, Department of Medicine and Science of Ageing, University “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara, Chieti

Giovanni Alessio

Department of Translational Biomedicine Neuroscience, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Bari

Ludovica Alonzo

Department of Neurosciences, Psychology, Drug Research, and Child Health, Eye Clinic, University of Florence, AOU Careggi, Florence

Teresio Avitabile

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Catania

Daniela Bacherini

Department of Neurosciences, Psychology, Drug Research, and Child Health, Eye Clinic, University of Florence, AOU Careggi, Florence

Francesco Bandello

School of Medicine, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University - Department of Ophthalmology, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan

Maria Antonietta Blasi

Ophthalmology Department, Catholic University “Sacro Cuore”, Rome

Francesco Boscia

Department of Translational Biomedicine Neuroscience, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Bari

Giacomo Boscia

Department of Translational Biomedicine Neuroscience, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Bari

Arturo Carta

Ophthalmology Unit, University of Parma

Paolo Carpineto

Ophthalmology Clinic, Department of Medicine and Science of Ageing, University “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara, Chieti

Niccolò Castellino

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Catania

Carlo Catti

DiNOGMI, Clinica Oculistica, University of Genoa

Luca Cerino

Ophthalmology Clinic, Department of Medicine and Science of Ageing, University “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara, Chieti

Maria Vittoria Cicinelli

School of Medicine, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University - Department of Ophthalmology, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan

Lorenzo Cifarelli

Department of Neurosciences, Psychology, Drug Research, and Child Health, Eye Clinic, University of Florence, AOU Careggi, Florence

Federico Corvi

Eye Clinic, Department of Biomedical and Clinical Science “Luigi Sacco”, Sacco Hospital, University of Milan

Ciro Costagliola

Department of Neurosciences, Reproductive Sciences and Dentistry. University of Naples Federico II, Naples

Rossella D’Aloisio

Ophthalmology Clinic, Department of Medicine and Science of Ageing, University “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara, Chieti

Francesco Di Bin

Department of Medicine, Ophthalmology, University of Udine

Francesco Dragotto

Department of Neurosciences, Psychology, Drug Research, and Child Health, Eye Clinic, University of Florence, AOU Careggi, Florence

Roberta Farci

Ophthalmology Service, Centre Hospitalier de Perpignan, France

Luisa Frizziero

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Padova

Fabrizio Giansanti

Department of Neurosciences, Psychology, Drug Research, and Child Health, Eye Clinic, University of Florence

Federico Giannuzzi

Ophthalmology Department, Catholic University “Sacro Cuore”, Rome

Matteo Gironi

Ophthalmology Clinic, Department of Medicine and Science of Ageing, University “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara, Chieti

Carla Iafigliola

Ophthalmology Clinic, Department of Medicine and Science of Ageing, University “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara, Chieti

Paolo Lanzetta

Department of Medicine, Ophthalmology, University of Udine

Rosangela Lattanzio

School of Medicine, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University - Department of Ophthalmology, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan

Andrea Lazzerini

Institute of Ophthalmology-University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena

Andrea Lembo

Eye Clinic University “Statale of Milan”, Milan

Arturo Licata

Ophthalmology Clinic, Department of Medicine and Science of Ageing, University “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara, Chieti

Celeste Limoli

Eye Clinic University “Statale of Milan”, Milan

Leonardo Mastropasqua

Ophthalmology Clinic, Department of Medicine and Science of Ageing, University “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara, Chieti

Rodolfo Mastropasqua

Ophthalmology Clinic, Department of Medicine and Science of Ageing, University “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara, Chieti

Edoardo Midena

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Padova – IRCCS Bietti Foundation, Rome

Giulia Midena

IRCCS Bietti Foundation, Rome

Massimo Nicolò

Eye Clinic University of Genoa

Paolo Nucci

Eye Clinic University “Statale of Milan”, Milan

Monica Maria Pagliara

Ophthalmology Department, Catholic University “Sacro Cuore”, Romee

Corrado Pizzo

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Catania

Pasquale Puzo

Department of Translational Biomedicine Neuroscience, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Bari

Stanislao Rizzo

Ophthalmology Department, Catholic University “Sacro Cuore”, Rome

Anna Romano

Ophthalmology Clinic, Department of Medicine and Science of Ageing, University “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara, Chieti

Leopoldo Rubinato

Department of Medicine - Ophthalmology, University of Udine

Marialudovica Ruggeri

Ophthalmology Clinic, Department of Medicine and Science of Ageing, University “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara, Chieti

Maria Grazia Sammarco

Ophthalmology Department, Catholic University “Sacro Cuore”, Rome

Valentina Sarao

Department of Medicine - Ophthalmology, University of Udine

Giancarlo Sborgia

Department of Translational Biomedicine Neuroscience, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Bari

Francesco Semeraro

Department of Medical and Surgical Specialties, Radiological Sciences, and Public Health, Ophthalmology Clinic, University of Brescia

Francesca Simonelli

Multidisciplinary Department of Medical, Surgical and Dental Specialities, Università della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Naples

Giovanni Staurenghi

Eye Clinic, Department of Biomedical and Clinical Science “Luigi Sacco”, University of Milan

Francesco Testa

Multidisciplinary Department of Medical, Surgical and Dental Specialities, Università della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Naples

Beatrice Tombolini

School of Medicine, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University - Department of Ophthalmology, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan

Lisa Toto

Ophthalmology Clinic, Department of Medicine and Science of Ageing, University “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara, Chieti

Lorenzo Vannozzi

Department of Neurosciences, Psychology, Drug Research, and Child Health, Eye Clinic, University of Florence, AOU Careggi, Florence

Daniele Veritti

Department of Medicine - Ophthalmology, University of Udine

Gianni Virgili

Department of Neurosciences, Psychology, Drug Research, and Child Health, Eye Clinic, University of Florence, AOU Careggi, Florence

2

Section 5 Vitreous and retina

Age-related macular degeneration and other causes of macular neovascularization pag. 13

Retinal vascular disease: diabetic retinopathy pag. 29

Retinal vascular diseases associated with cardiovascular and other systemic diseases pag. 51

Retinal infections and toxicity pag. 75

Choroidal diseases and inflammation pag. 99

Retinal infections pag. 117

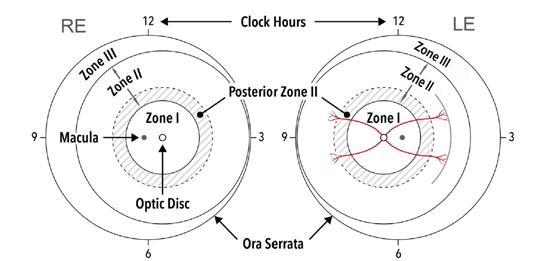

Retinopathy of prematurity pag. 139

Posterior vitreous detachment and vitreous hemorrhage pag. 155

Vitreo-macular traction syndrome pag. 169

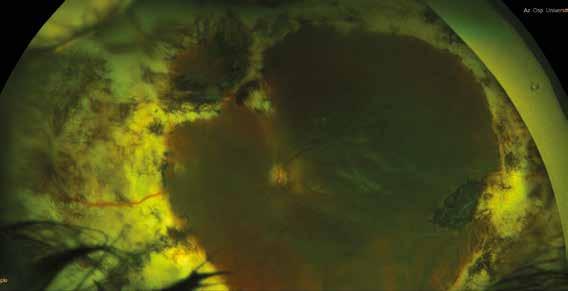

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment pag. 181

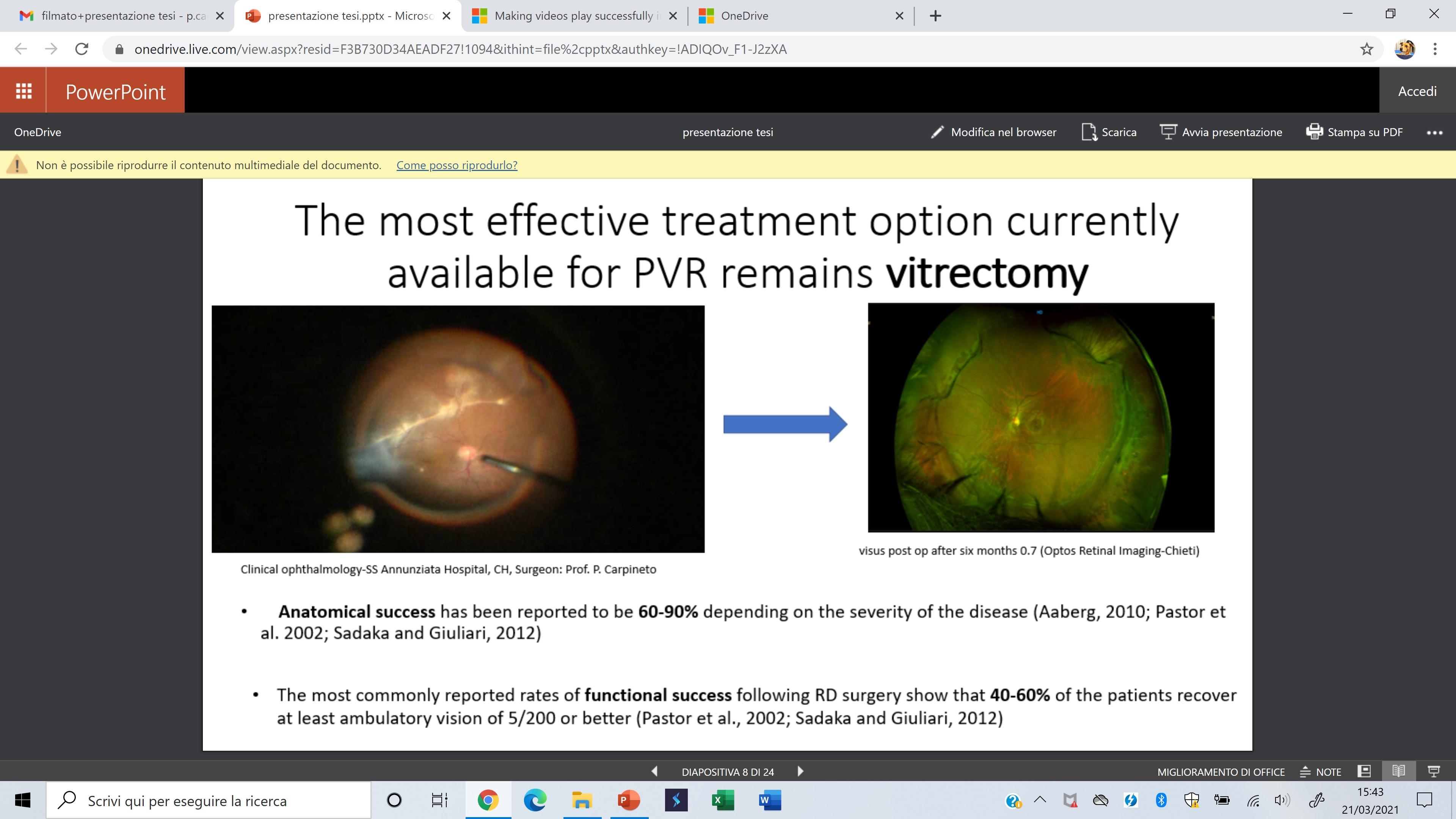

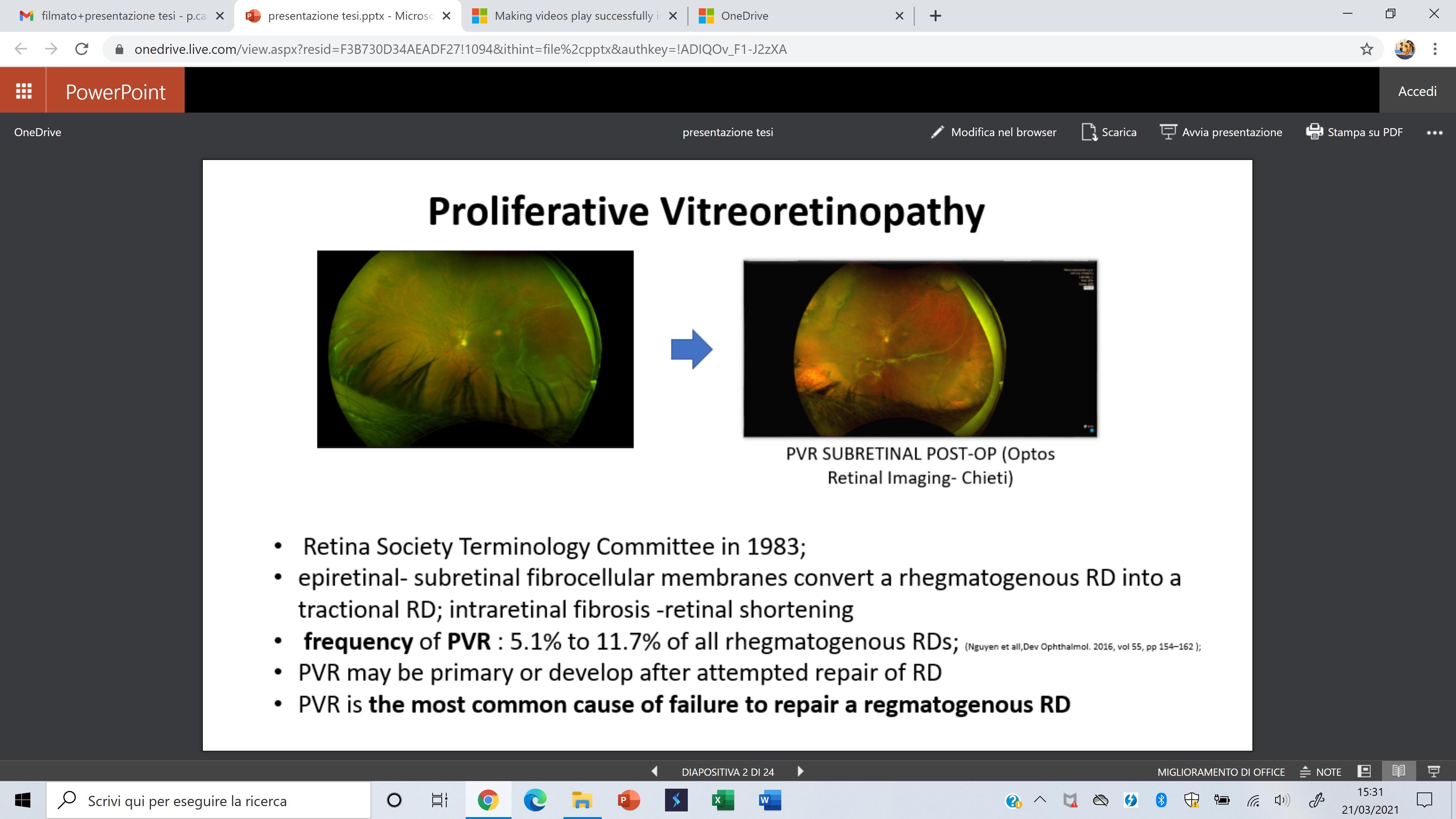

Proliferative vitreoretinopathy pag. 189

Section 6 Neuro-ophthalmology, pediatrics and injuries

Neuro-ophthalmology pag. 207

Pediatric ophthalmology, refractive errors and amblyopia pag. 249

Ocular injuries pag. 265

Systemic ophthalmology pag. 275

Section 7 Genetic diseases and neoplasia of the eye

Clinical genetics of the eye pag. 289

Anterior segment tumors pag. 301

Posterior segment intraocular tumors pag. 313

Diseases of the retina

Diseases of the Vitreous, vitreo-retinal interface and retinal detachment

Federico Corvi, Giovanni Staurenghi

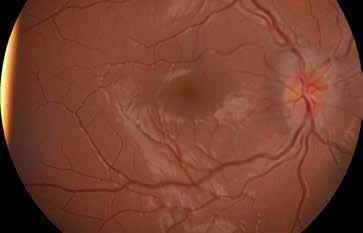

Macular neovascularization (MNV) is the invasion of abnormal vascular tissue into the retina, particularly the outer retina, the subretinal space, or the sub-retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) space, in various combinations.1 The presence of neovascularization is a pathologic process that could be associated with intraretinal and/or subretinal fluid, hemorrhages and concurrent vision loss. At the same time, MNV can be considered both evidence of an advanced stage of the pathological process as well and a protective ocular response aimed at improving oxygen and nutrient supply to the outer retina and RPE.2

The most common cause of MNV is age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and MNV lesions are classified into three different subtypes based on their anatomical location.

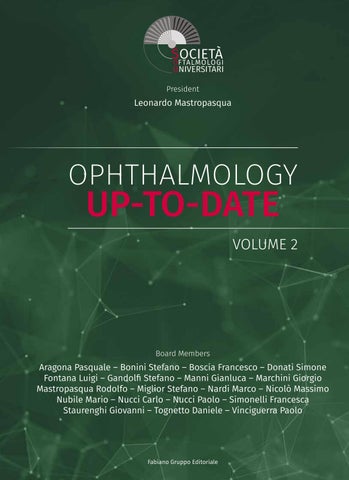

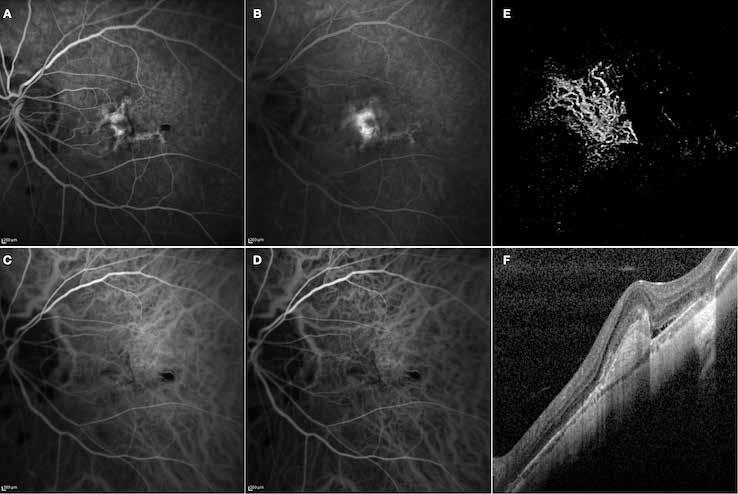

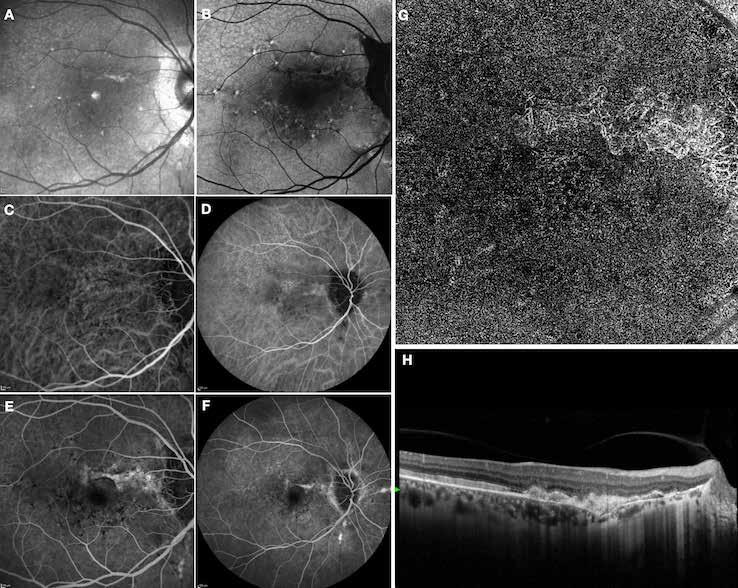

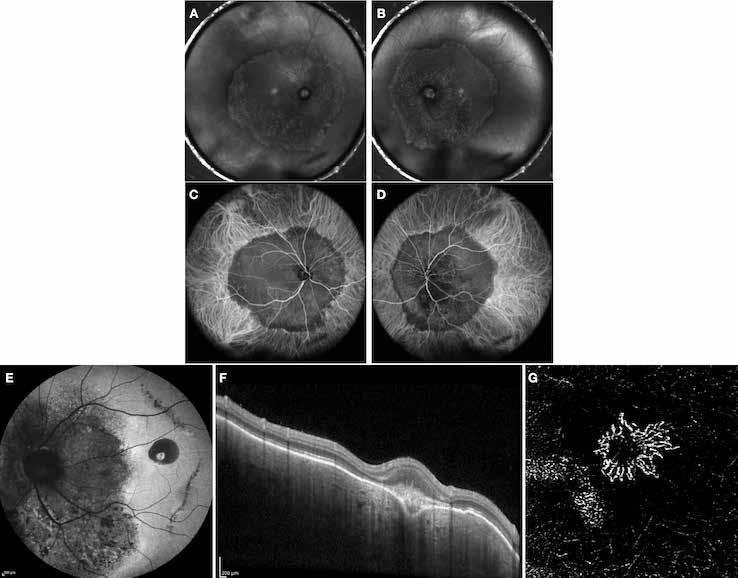

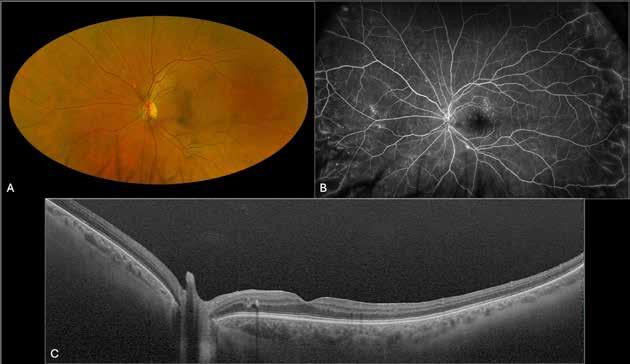

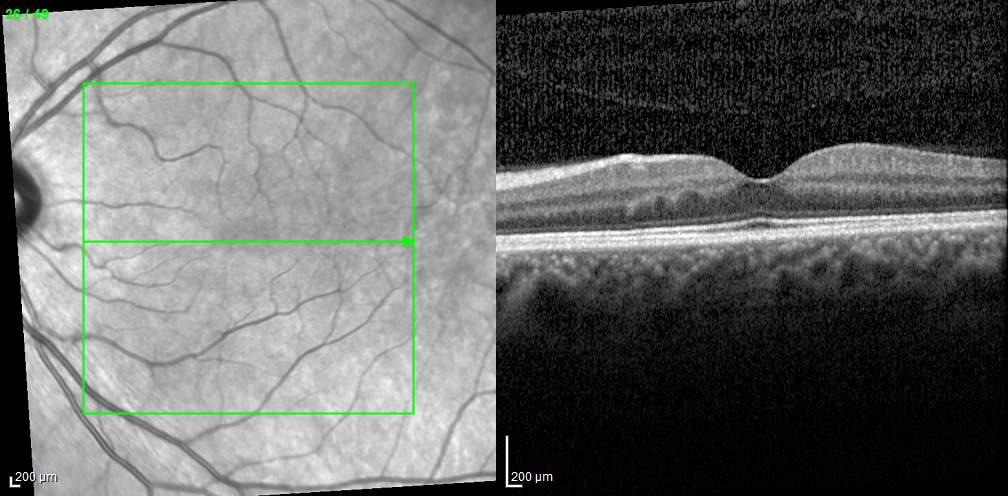

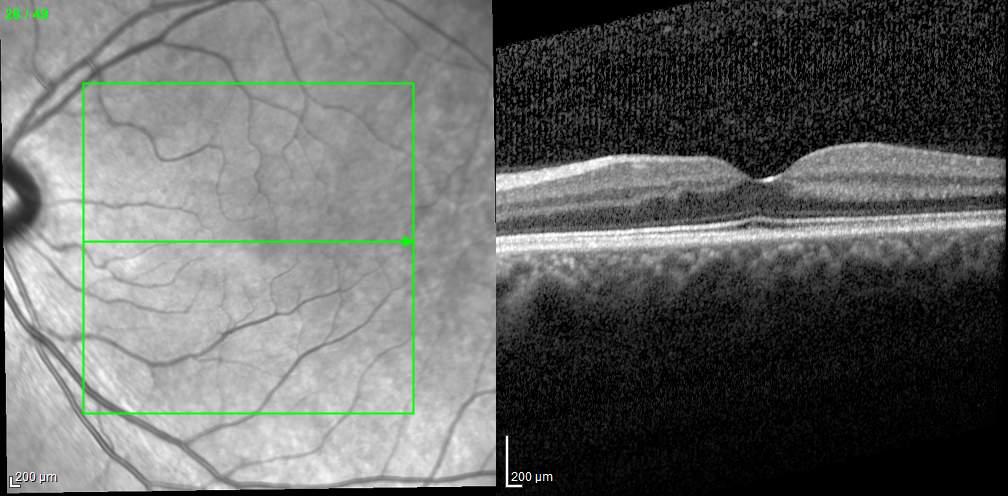

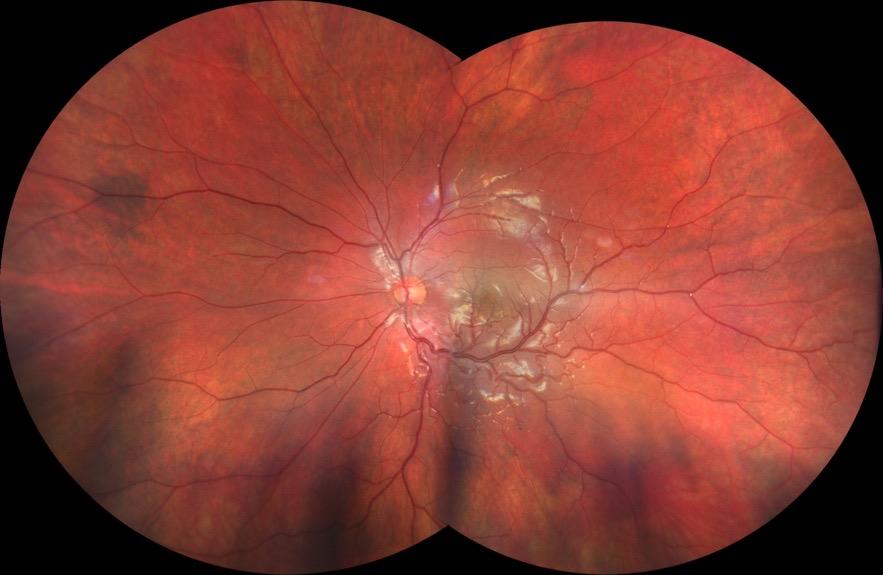

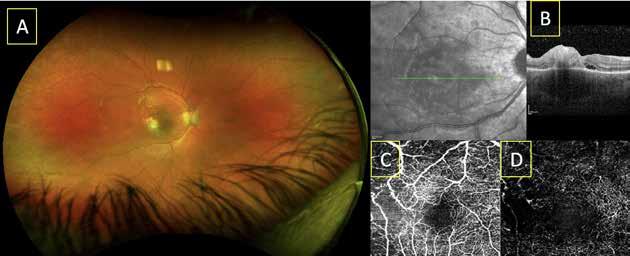

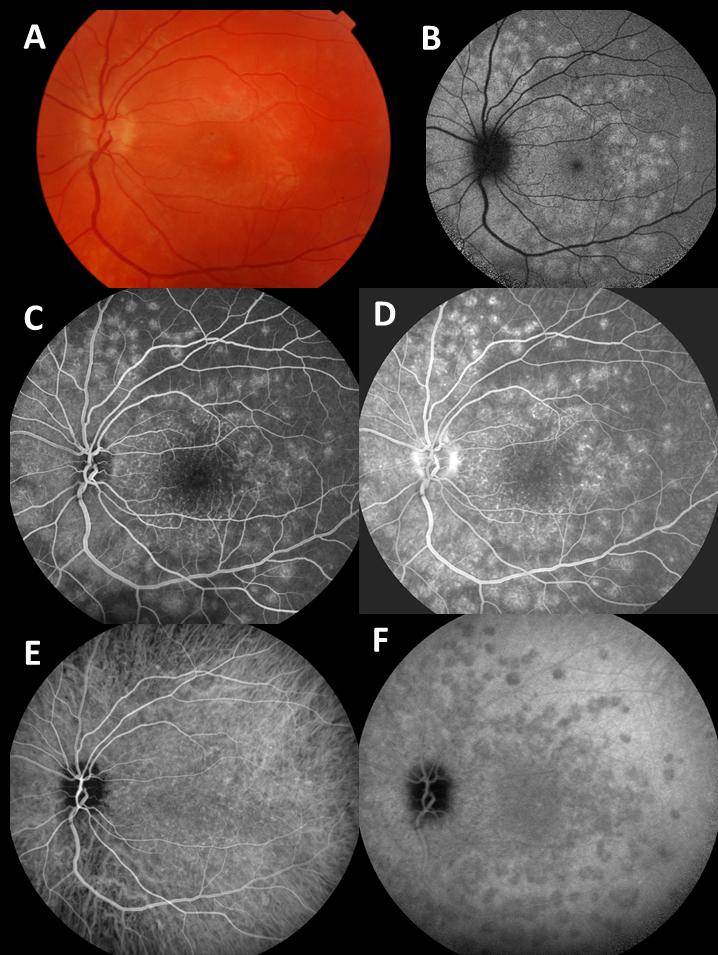

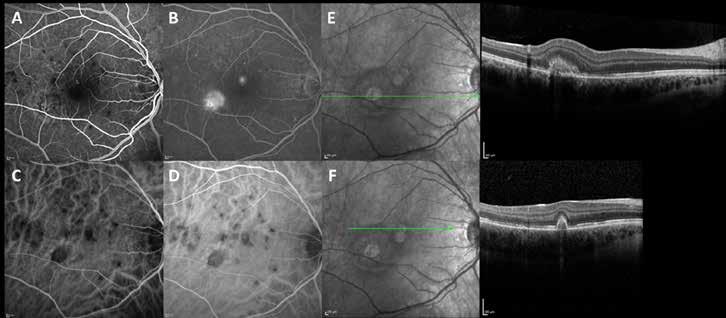

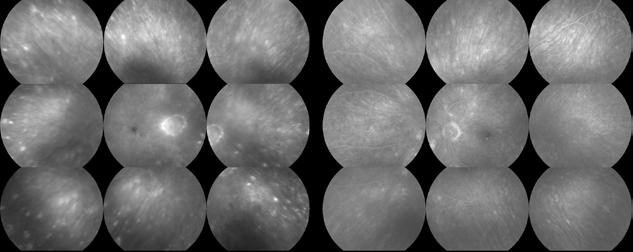

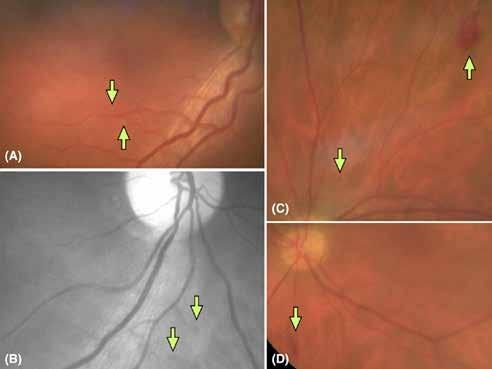

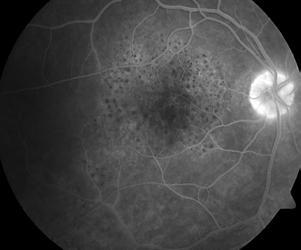

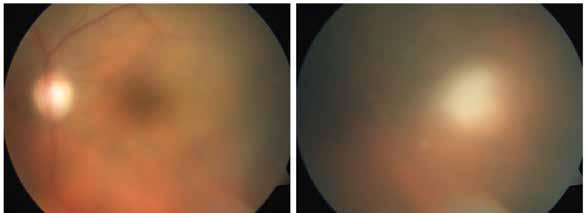

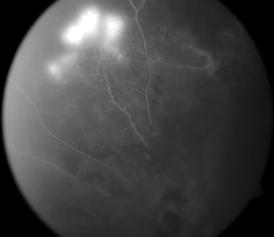

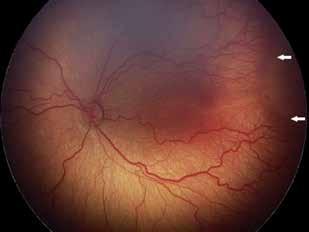

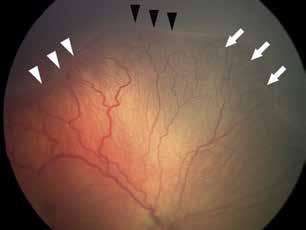

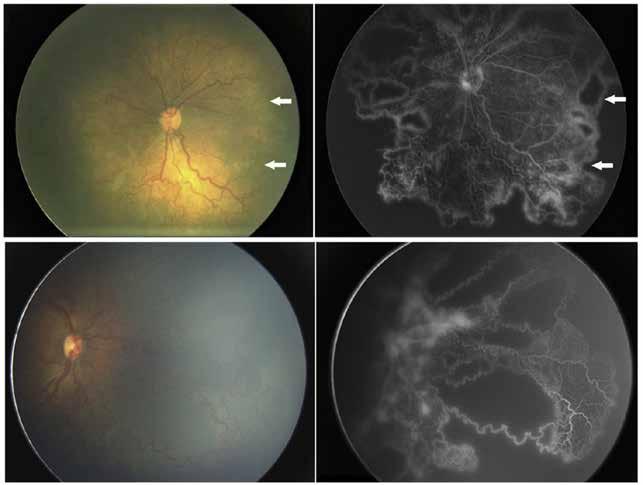

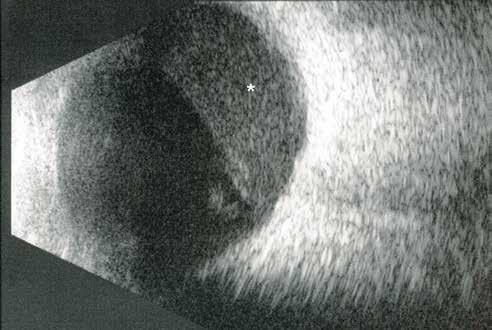

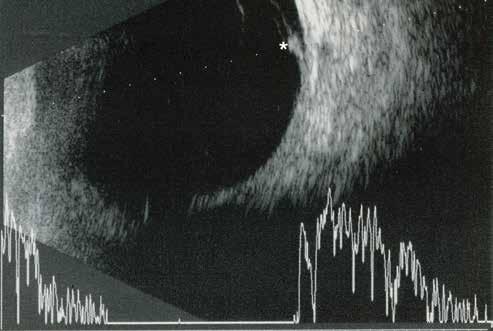

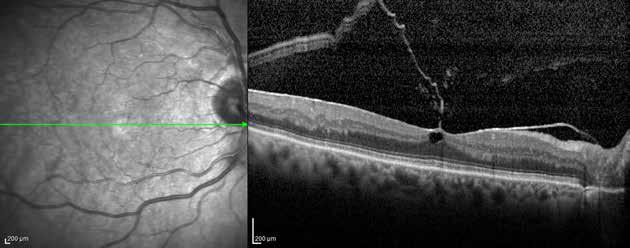

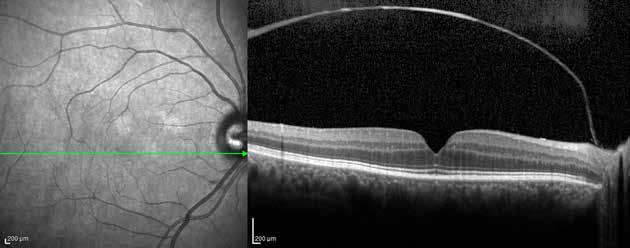

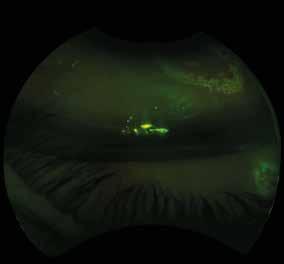

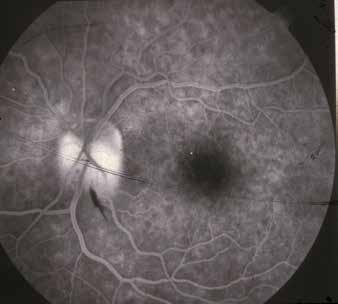

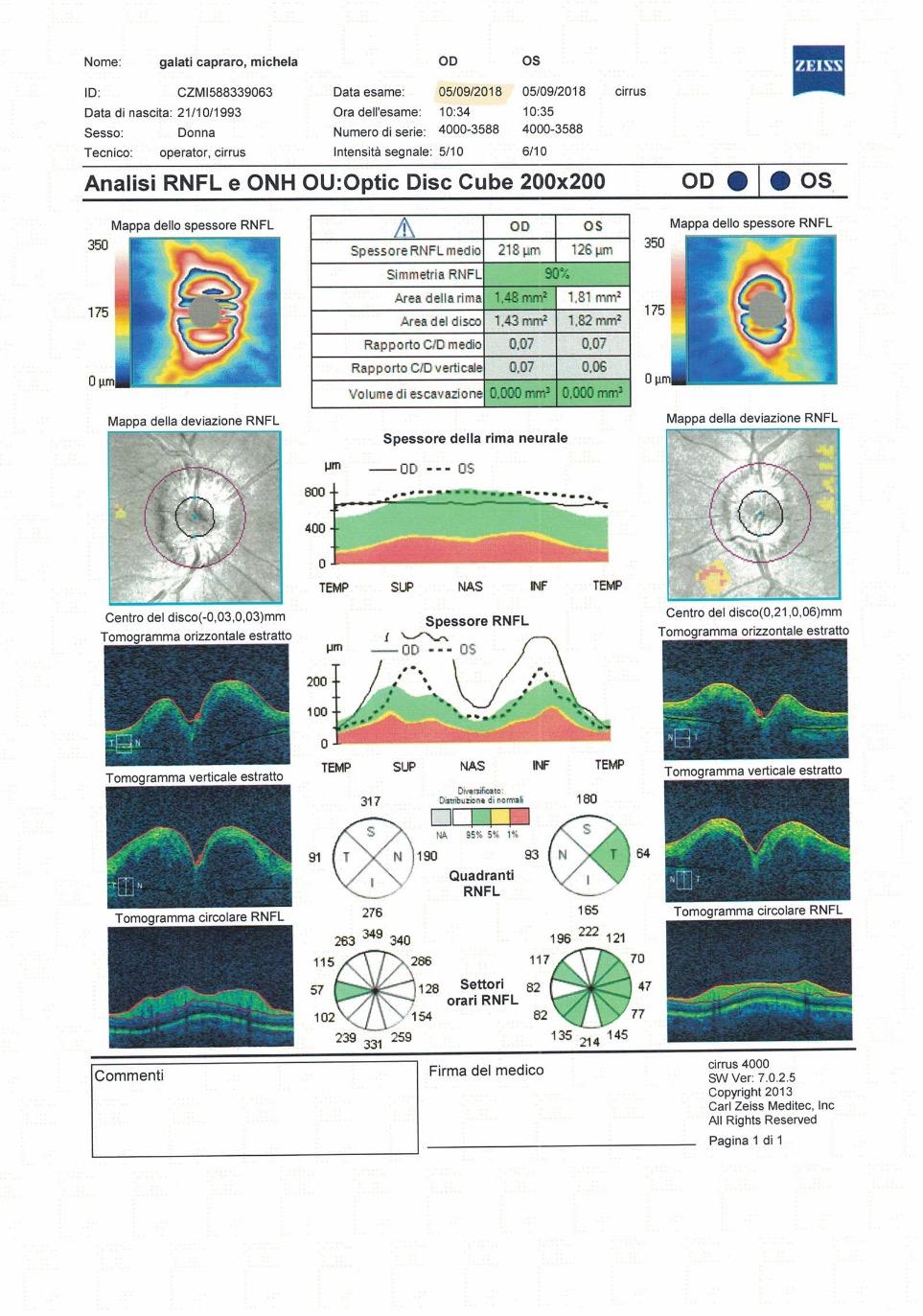

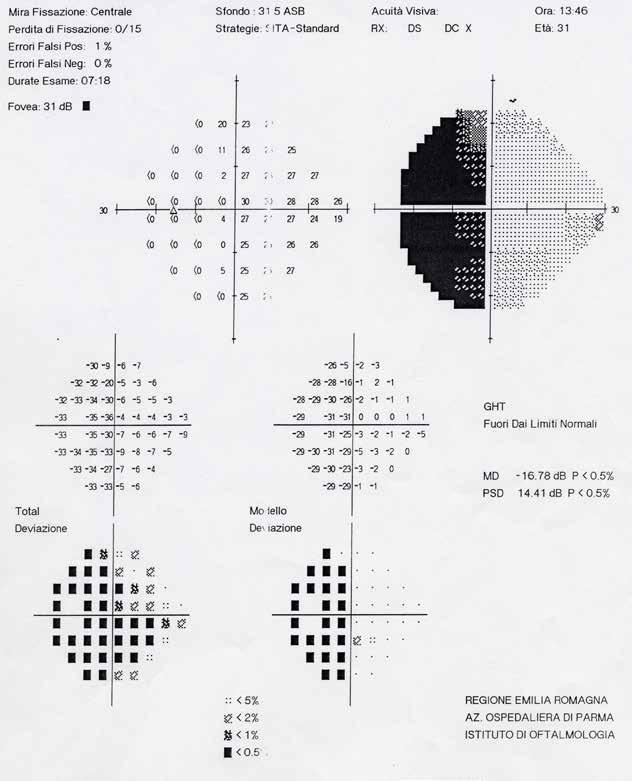

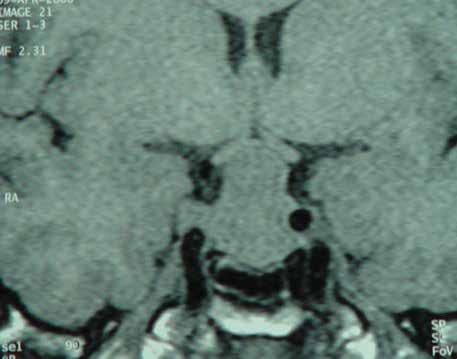

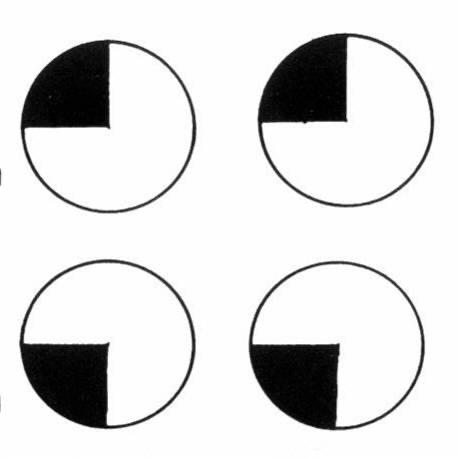

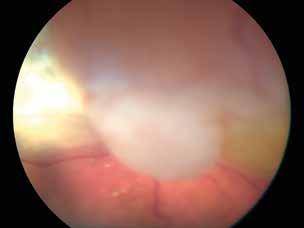

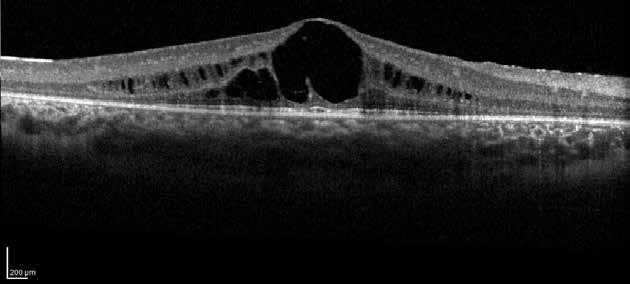

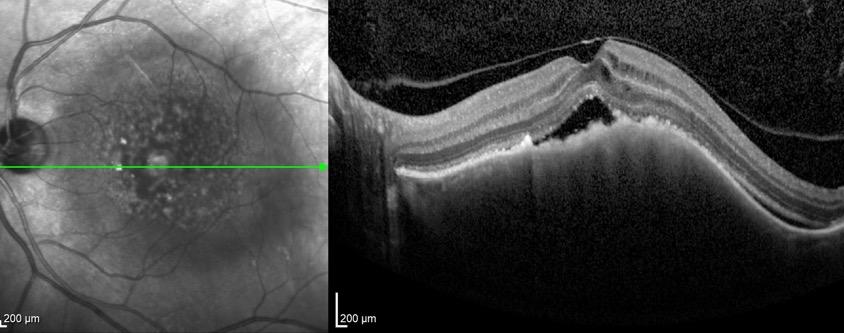

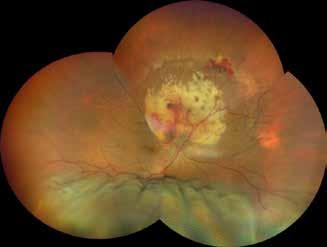

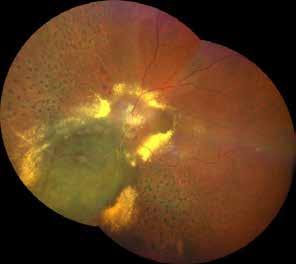

Type 1 MNV is characterized by the growth of vessels from the choriocapillaris into the subRPE space. On fluorescein angiography (FA), Type 1 MNV commonly presents late leakage of undetermined source, defined as areas of leakage at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium in the late phase of the angiogram without well-demarcated areas of hyperfluorescence in the early phase of the angiogram that would explain the leakage. It may also appear as fibrovascular pigment epithelial detachment, defined as areas of irregular retinal pigment epithelium elevation detectable on stereoscopic angiography. As a result, Type 1 MNV was originally termed occult neovascularization.3 Indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) should be used to visualize part of the vascular structure but it often reveals only late staining of the lesion, referred to as a plaque.4 (Figure 1)

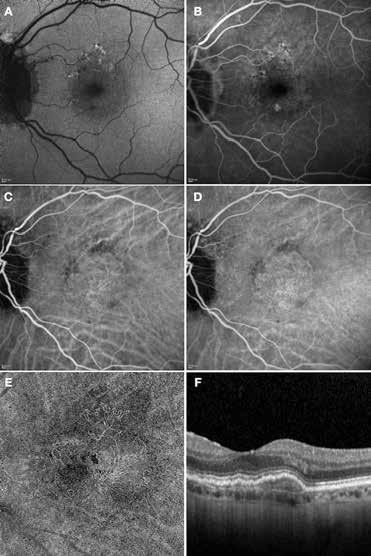

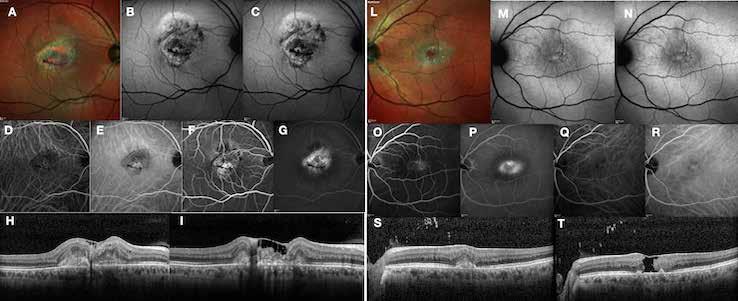

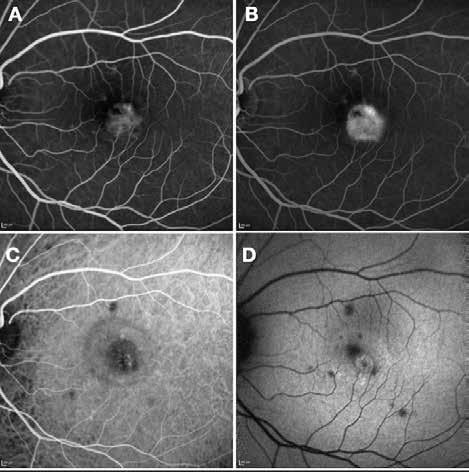

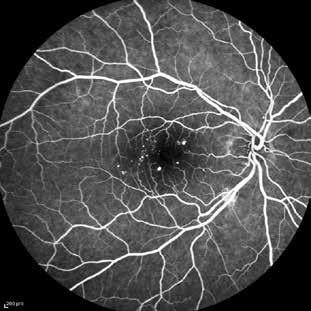

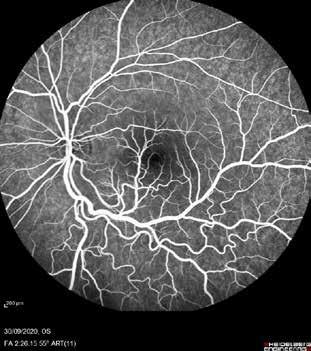

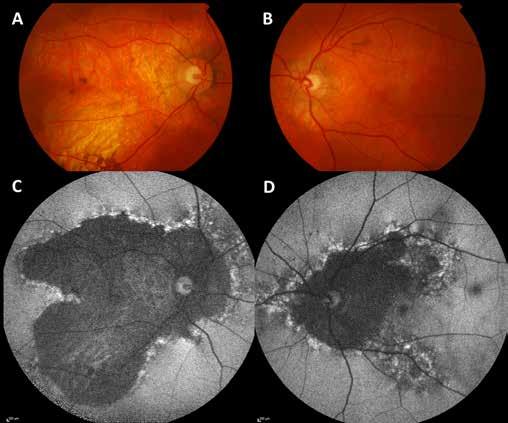

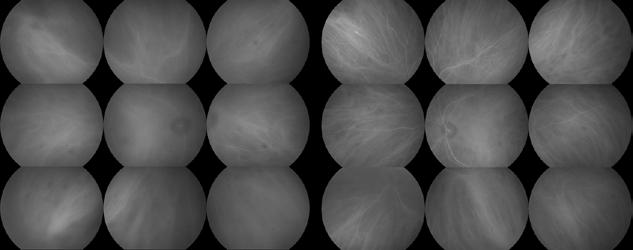

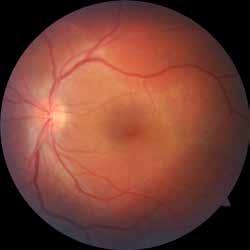

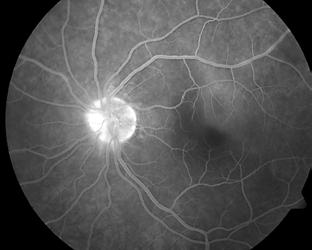

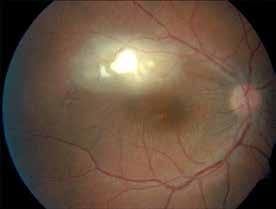

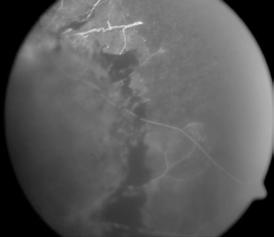

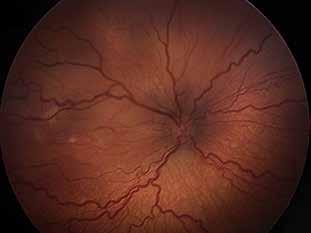

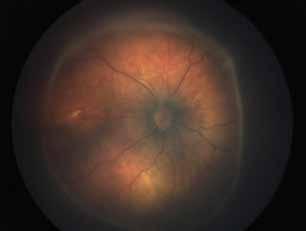

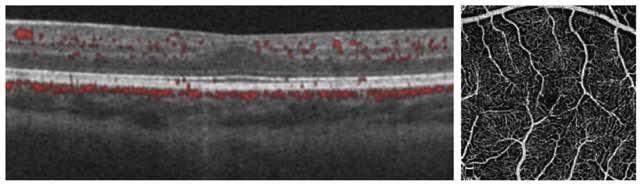

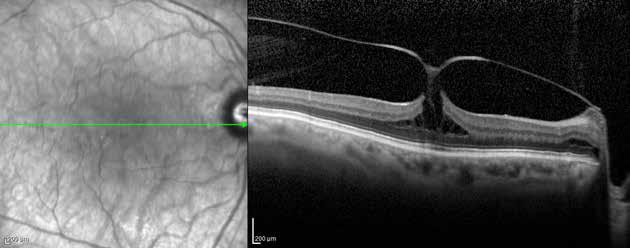

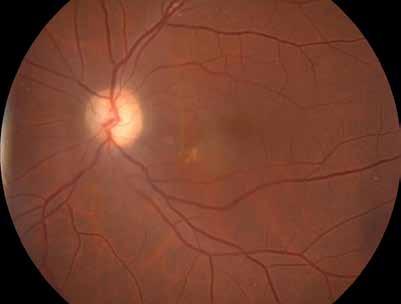

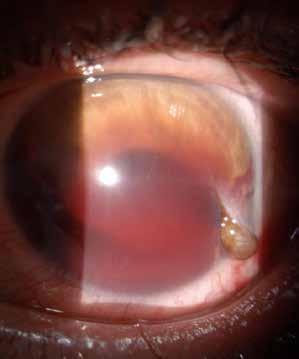

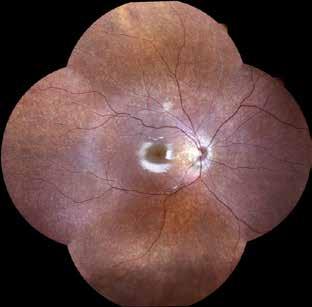

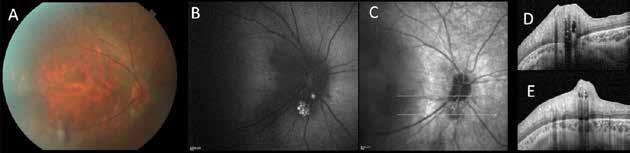

Type 2 MNV refers to the proliferation of new vessels originating from the choroid into the subretinal space. These vessels penetrate through the sub-RPE, making the subretinal portion the dominant component of the pathological process in Type 2 neovascularization. On FA, these lesions are usually “well-defined” as they present a well-demarcated area of hyperfluorescence in the early phase of the angiogram, followed by progressive dye pooling in the overlying subsensory retinal space during the late phase. (Figure 2)

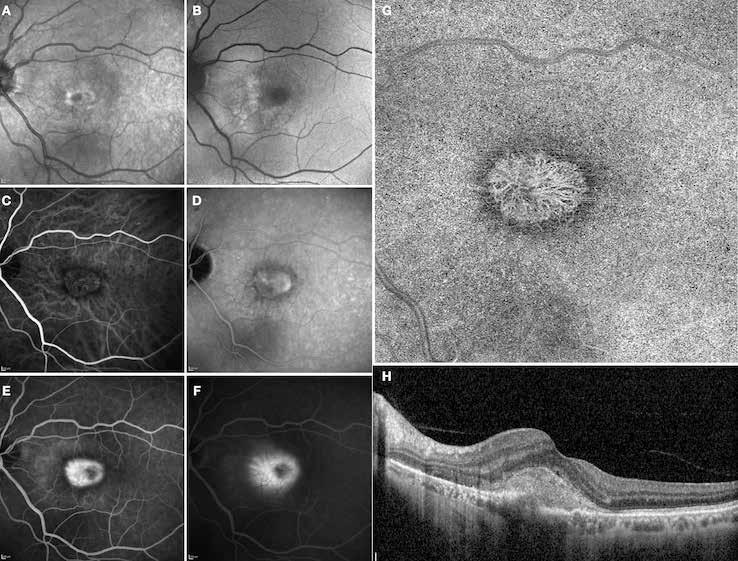

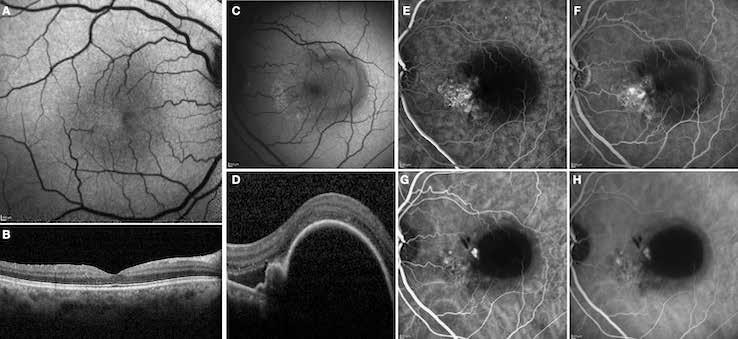

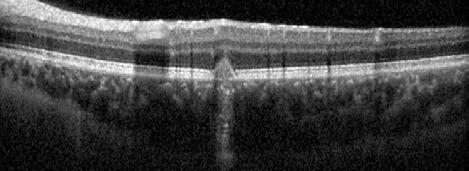

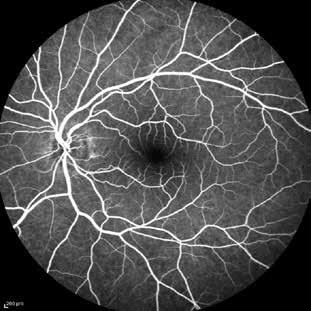

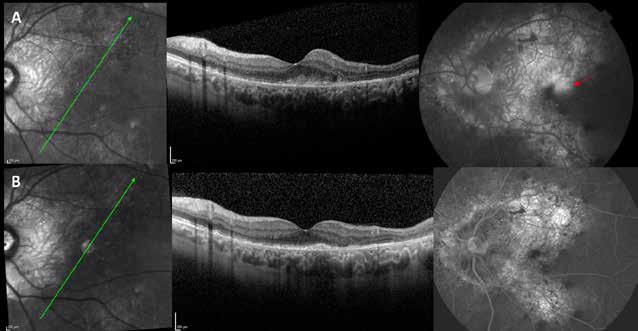

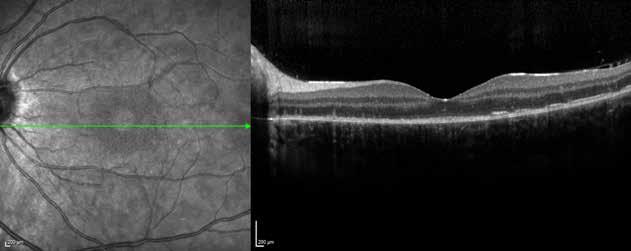

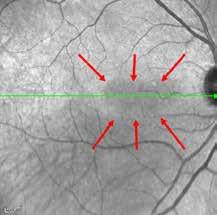

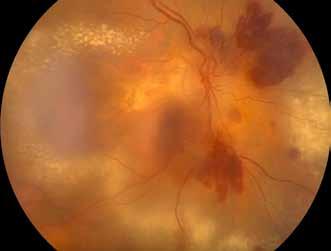

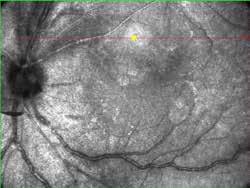

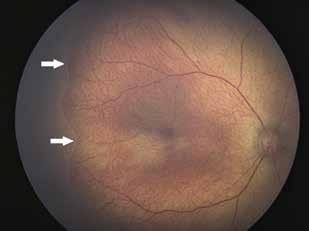

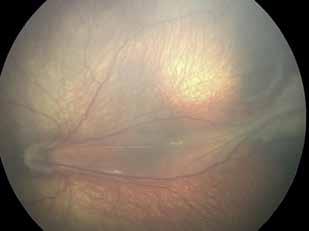

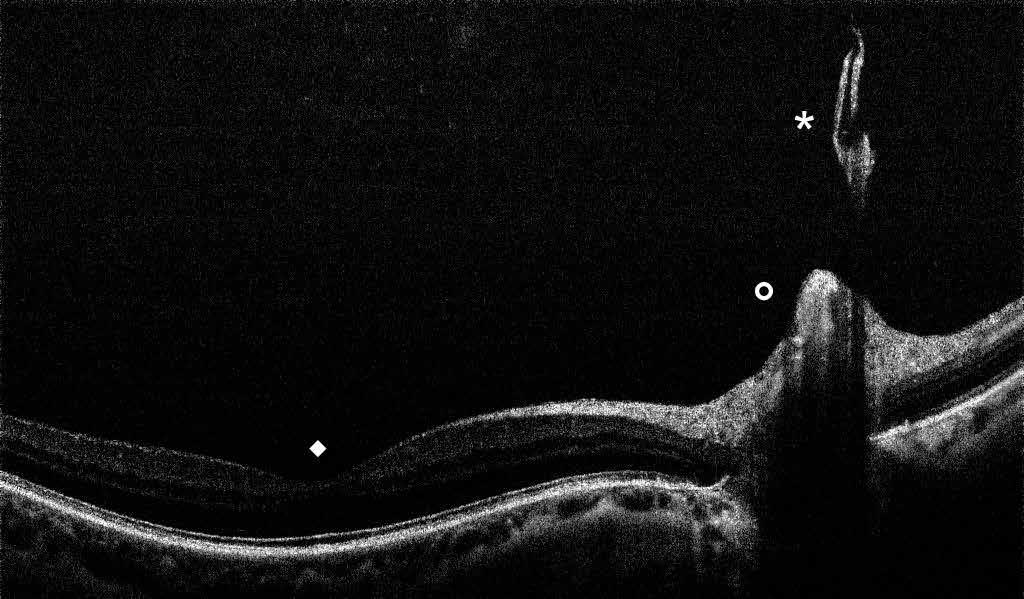

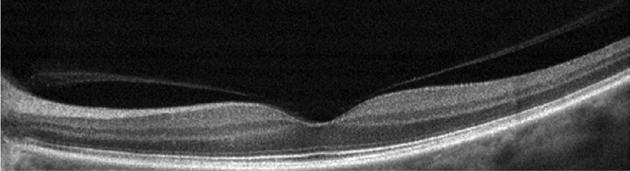

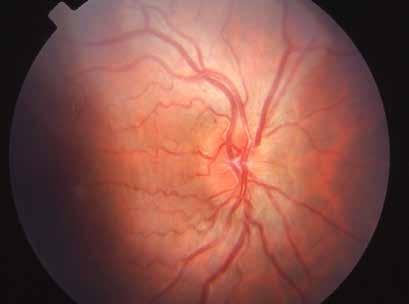

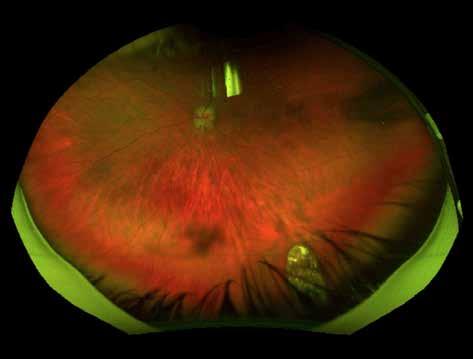

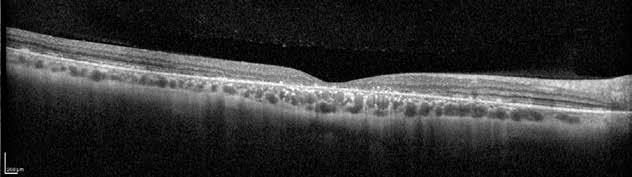

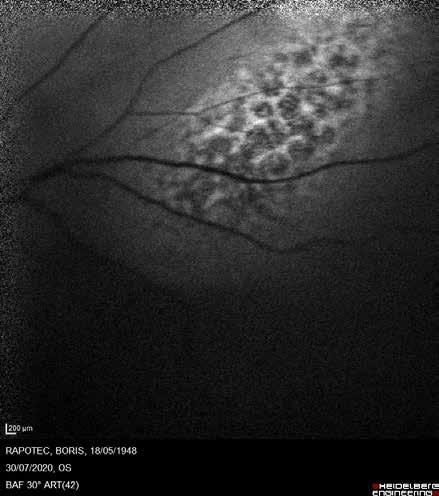

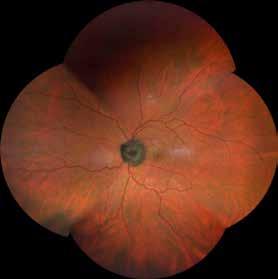

Type 3 MNV refers to the growth of vessels from the retinal circulation toward the outer retina. It is believed that vascular proliferation begins in the deep retinal capillary plexus, with the growth vector extending toward the outer retina. On FA and ICGA, Type 3 MNV appears as a hyperfluorescent intraretinal vascular complex with leakage in the late phases of the examination. Late-phase leakage ion ICGA is a unique feature of MNV lesions. Since these lesions originate from the retinal circulation, they never arise within the foveal avascular zone. Instead, they develop near its edge or at a variable distance from it, typically from the terminal portions of third-order arterioles and venules.5 (Figure 3)

Over the years, different hypotheses based on histopathologic data and clinical studies have been proposed to explain the different origins of MNV sub-types in AMD.6–8 In particular, studies have demonstrated choriocapillaris impairment in the context of late AMD, suggesting a key role in the pathogenesis of MNV. Specifically, several histopathologic studies have shown

1. Multimodal imaging of Type 1 macular neovascularization. Fundus autofluorescence (A) showing fine alteration of retinal pigment epithelium. Late phase (B) of fluorescein angiography revealing pinpoints of hyperfluorescence. Both early (C) and late phases (D) of indocyanine green angiography reveal a central hyperfluorescent zone, indicative of type 1 macular neovascularization, consistent with optical coherence tomography angiography (E). Optical coherence tomography displaying a shallow irregular elevation of retinal pigment epithelium (F).

that choriocapillaris density decreases as AMD severity increases.9,10 The advent of OCTA has provided the opportunity to observe the choriocapillaris in-vivo and quantitatively analyze flow deficits. For this reason, choriocapillaris imaging and analysis using OCTA has become one of the hottest topics in recent years.11–15 Several studies have reported a progressive reduction in blood flow in the choroid and choriocapillaris during the progression of AMD. In particular, in neovascular AMD, several studies have observed a dark ring surrounding type 1 MNV. 16,17 It has been hypothesized that this “dark-halo” may result from the mechanical compression of the underlying inner choroid due to the exudative changes leading to inner choroidal ischemia. Alternatively, it may represent a vascular steal phenomenon caused by diverted flow through the neovascular membrane.16,18–21 The choriocapillaris immediately sur-

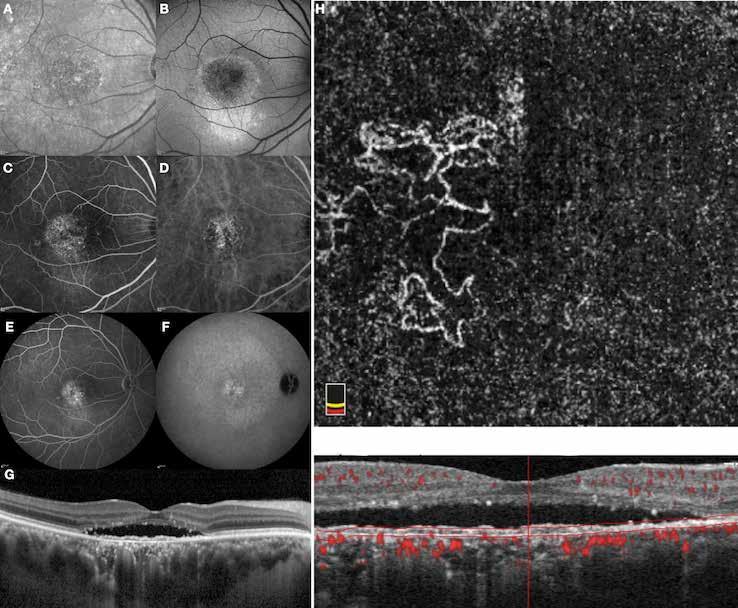

Figure 2. Multimodal imaging of Type 2 macular neovascularization. Infrared reflectance (A) and fundus autofluorescence (B) revealing abnormalities of retinal pigment epithelium. Early and late phase of indocyanine green angiography (C and D) and fluorescein angiography (E and F) showing a well-defined neovascular network. Optical coherence tomography angiography (G) displaying the neovascular network. Optical coherence tomography (H) showing the neovascularization above the retinal pigment epithelium with disorganization of the overlying inner segment/outer segment junction.

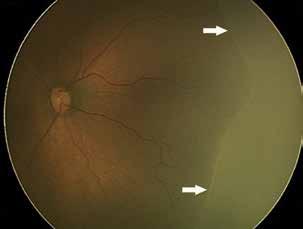

rounding MNV shows greater flow deficits compared to other areas of the macula. This perilesional dark halo in treatment-naïve eyes suggests that RPE hypoxia caused by choriocapillaris disruptions may drive the release of VEGF and the development of MNV.9,17,20,22 As initially hypothesized, patients with MNV may exhibit more localized choriocapillaris impairment, with greater reserve to guide the angiogenesis process, while eyes with atrophic AMD may show more diffuse choriocapillaris lesions, setting the stage for progressive tissue loss as opposed to neovascularization.23,24 Moreover, it has been observed that the choriocapillaris in the peripheral macula differs depending on the MNV subtype, with severe impairment in Type 3 MNV eyes compared to Type 1/2 MNV eyes.25 The widespread choriocapillaris impairment in Type 3 MNV eyes may also explain why these eyes are more prone to developing atrophy compared to Type 1 MNV eyes. However, MNV can also be secondary to other conditions such as high myopia. 26 In pathologic myopia, the progressive posterior segment elongation and deformation may lead to mechanical stress on the retina, causing an imbalance between pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors, resulting in myopic MNV.27–30 Supporting this, the presence of lacquer cracks has been shown to be a predisposing factor for the development of myopic MNV. 28–30 To

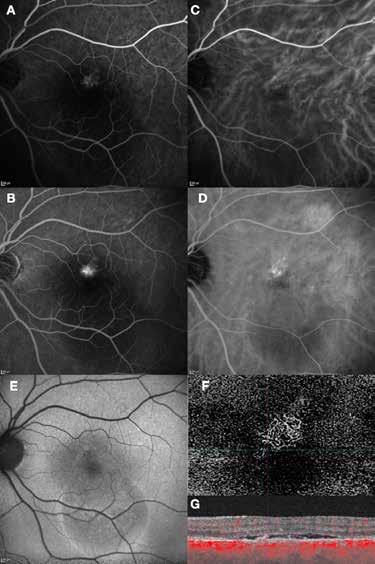

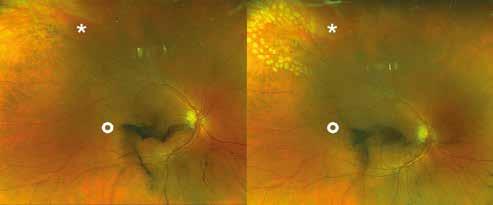

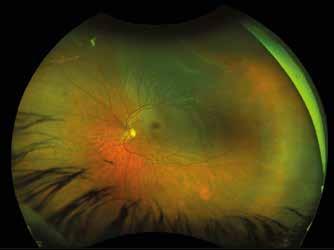

Figure 3. Two examples of Type 3 macular neovascularization. In the first case, Indocyanine green angiography (B) and fluorescein angiography revealing the Type 3 macular neovascularization (arrowhead). Optical coherence tomography (C) showing the detachment of retinal pigment epithelium with the hyperreflective material related to the neovascularization. In the second case, optical coherence tomography (E) showing the intraretinal hyperreflective material related to the neovascularization with intraretinal fluid. Fundus autofluorescence (F) showing abnormalities of retinal pigment epithelium. Optical coherence tomography angiography (G) showing the neovascular lesion.

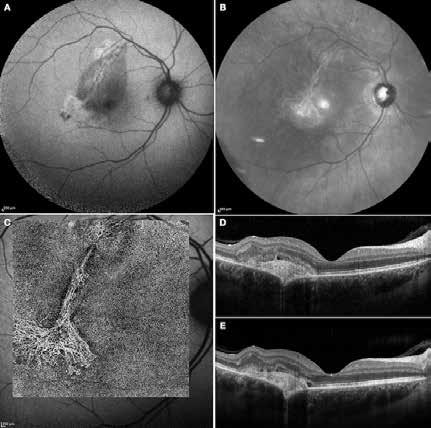

Figure 4. Multimodal imaging of Type 2 macular neovascularization secondary to pathologic myopia.

Fluorescein angiography (A and B) showing the Type 2 macular neovascularization as an hyperfluorescent area that become more intense with moderate leakage in the late phase. Indocyanine green angiography (C and D) and optical coherence tomography angiography (E) revealing the neovascular network. Optical coherence tomography (F) showing the subretinal hyperreflective material corresponding to the neovascular lesion with subretinal fluid.

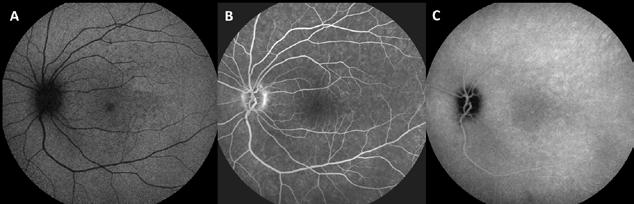

Figure 5. Multimodal imaging of Type 1 macular neovascularization secondary to central serous chorioretinopathy. Infrared reflectance (A) and fundus autofluorescence (B) revealing abnormalities of retinal pigment epithelium. Fluorescein angiography (C and D) showing pinpoints of hyperfluorescence. Indocyanine green angiography (E and F) displaying a central hyperfluorescent zone suggesting the increase choroidal hyperpermeability. Optical coherence tomography (G) showing the shallow irregular retinal pigment epithelium elevation with subretinal fluid. Optical coherence tomography angiography (H) revealing the neovascular network.

diagnose myopic MNV, a multimodal imaging approach based on fundus biomicroscopy, FA, ICGA, OCT and OCTA is recommended. Most myopic MNVs present as Type 2 lesions, and the number of anti-VEGF injections required for myopic MNV is generally lower than those required for AMD.31,32 (Figure 4)

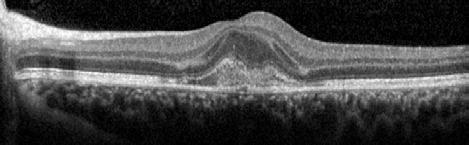

MNV may also develop in patients with central serous chorioretinopathy. In this condition, the pathogenesis of MNV is not yet fully understood. It is known that it can occur after laser photocoagulation or photodynamic therapy as a compensatory response to treatment; however, MNV may also develop in cases without history of laser treatment. In these cases, MNV may develop in a manner similar to AMD, where the rupture of Bruch’s membrane due to chronic RPE changes and long-standing serous pigment epithelium detachment allows for the growth of Type 1 neovascularization.33–36 (Figure 6)

It should be noted that MNV may develop in cases without evidence of chronic subretinal fluid, AMD changes, or other degenerative changes. These patients are often diagnosed with neovascularization from an unknown or idiopathic etiology. However, MNV typically grows above focal areas of choroidal thickening and dilated choroidal vessels. The dilation of cho-

Figure 6. Multimodal imaging of Type 1 macular neovascularization secondary to central serous chorioretinopathy. Fluorescein angiography (A and B) showing pinpoints of hyperfluorescence with leakage in the late phase. Indocyanine green angiography (C and D) displaying the central hyperfluorescent area and the adiacent area of choridal hyperpermeability. Fundus autofluorescence (E) revealing abnormalities of retinal pigment epithelium. The en face of optical coherence tomography angiography (F) showing the neovascular network and the B-scan displaying the shallow irregular retinal pigment epithelium elevation with subretinal fluid (G).

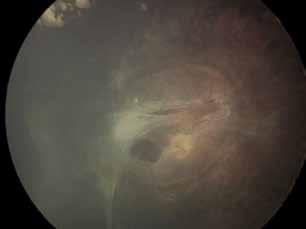

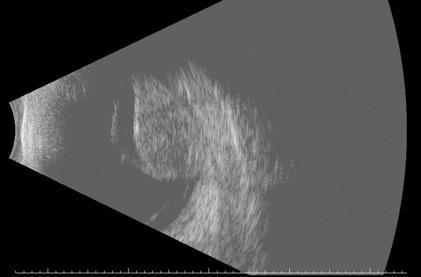

roidal vessel can lead to the obliteration of the choriocapillaris and Sattler’s layer, along with concomitant focal RPE alterations, which contribute to the development of MNV.36 The main challenge in these cases is distinguish whether the presence of subretinal fluid is the result of MNV or choroidal hyperpermeability. Imaging techniques can provide valuable insights, but anti-VEGF treatments are the main way to assess the activity status of MNV. Choroidal rupture is a rare but serious complication that occurs in ocular trauma. The rupture typically involves the RPE, Bruch’s membrane, and the choriocapillaris, resulting in visual loss due to macular involvement or the development of MNV.37 The configuration of MNV typically

Figure 7. Multimodal imaging of Type 2 macular neovascularization secondary to choroidal rupture. Blue autofluorescence (A) and infrared reflectance (B) showing the linear change in the retinal pigment epithelium. Optical coherence tomography angiography (C) displaying the choroidal rupture as a regular line of severe choriocapillary rarefaction and a well-defined neovascular network (open arrowheads). Optical coherence tomography (D and E) revealing the rupture of retinal pigment epithelium, Bruch’s membrane and choriocapillaris with subretinal hyperreflective material and subretinal fluid cystoid space.

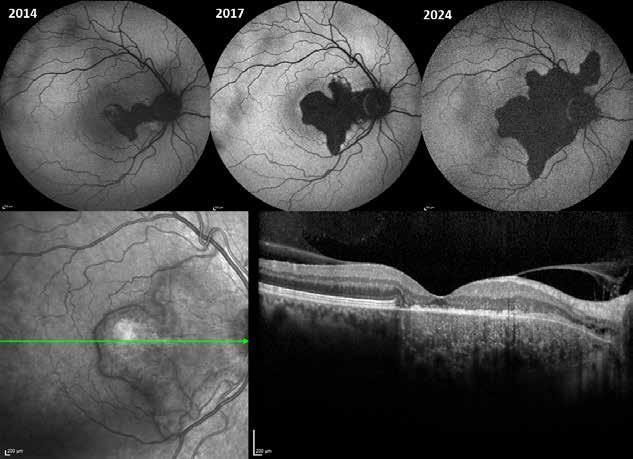

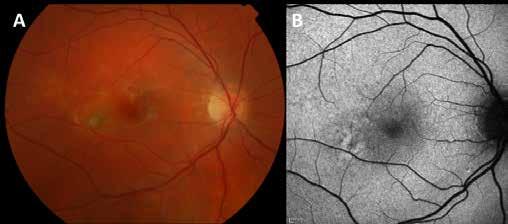

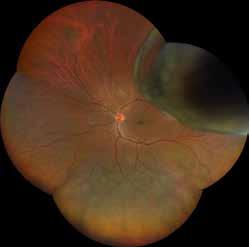

follows the spatial profile of the choroidal rupture, although in some cases, MNV originates from the rupture and grows laterally without specific correlation to the shape of the Bruch’s membrane break.38 (Figure 7) Similarly, patients with angioid streaks are predisposed to developing MNV. (Figure 8) Angioid streaks appear as irregular, bilateral, narrow, and jagged lines extending from the margin of the optic disc. They result from crack-like breaks in Bruch’s membrane, which is structurally abnormal, making these areas prone to localized ruptures. This process may occur spontaneously or could be secondary to even mild blunt trauma.39 The incidence of MNV ranges from 42% to 86%, and it can manifest bilaterally, often asymmetrically, in up to 71% of cases.40 Higher percentages of MNV have been found in larger and longer lesions, with even higher risk of development when the streaks are located within one disc diameter from the center of the posterior pole.41 MNV in angioid streaks is characterized by frequent recurrence in fact, even after years of inactive disease, new neovascular lesions can arise from a pre-existing lesion or as new area of neovascularization distant from the original lesion.39

Type 2 macular telangiectasia is a bilateral condition of unknown cause, characterized by alterations in the macular capillary network and neurosensory atrophy.42 This condition is as-

Figure 8. Multimodal imaging of Type 2 macular neovascularization secondary to angioid streaks. Infrared reflectance (A) and blue autofluorescence (B) revealing the fundus alterations secondary to angioid streaks. Indocyanine green angiography (C and D) and fluorescein angiography (E and F) showing an hyperfluorescent area that become more intense in the late phase as Type 2 neovascularization. Optical coherence tomography angiography showing the macular neovascularization with a define network that closely followed the trajectory of angioid streak (G). Optical coherence tomography displaying the area of atrophy retinal pigment epithelium changes with the neovascular tissue above the retinal pigment epithelium (H).

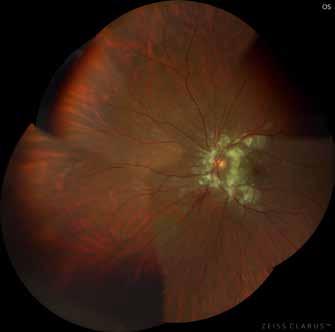

sociated with various retinal changes, such as blunting or lack of foveolar reflex, reduced retinal transparency, crystalline deposits, mild capillary ectasia, slightly dilated venules, foveal atrophy, lamellar or full-thickness macular holes and neovascular complexes.42-44 Neovascular lesions appear to be different from MNV in AMD. They seem to originate from the retinal vasculature, but can access the subretinal space and may develop a retinal-choroidal anastomosis. Sometimes, the membranes resemble markedly ectatic capillaries, which could represent a retinal-retinal anastomosis.43,45,46 The development of a neovascular lesion may occur at an advanced stage of the pathological process and lead to frequent vision loss. Neovascular lesions are associated with macular edema, subretinal hemorrhages before progressing to a cicatricial and fibrotic stage. (Figure 9 and 10). Therefore, intervention may potentially be beneficial in the early stages of the disease.46

Macular neovascularization may also occur in the context of intraocular tumors such as choroidal nevi and choroidal osteoma. The choroidal nevus is the most common intraocular tu-

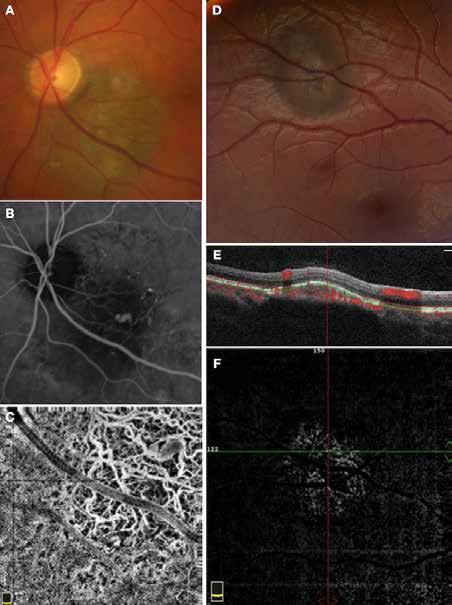

Figure 9. Multimodal imaging of bilateral macular neovascularization and idiopathic macular telangiectasia. MultiColor image (A) revealing the hemorrhage at the posterior pole and the dilated telangiectatic perifoveal vessels. Blue and green fundus autofluorescence (B and C) showing the retinal pigment epithelium changes. Indocyanine green angiography (D and E) and fluorescein angiography (F and G) displaying the macular neovascularization with leakage in the late phase. OCT (H and I) showing the outer retinal atrophy, the subretinal hyperreflective material and the internal changes related to the Müller cell degeneration. MultiColor image (L) revealing the dilated telangiectatic perifoveal vessels and the multiple golden crystalline refractile deposits. Blue and green fundus autofluorescence (M and N) showing the retinal pigment epithelium changes with the loss of macular pigment. Fluorescein angiography (O and P) and indocyanine green angiography (Q and R) displaying the macular neovascularization. OCT (S and T) revealing the outer retinal atrophy, the subretinal hyperreflective material and the full thickness macular hole due to the Müller cell degeneration.

Figure 10. Multimodal imaging of macular neovascularization and idiopathic macular telangiectasia. Blue fundus autofluorescence (A and C) showing the retinal pigment epithelium changes with the loss of macular pigment and the dilated telangiectatic perifoveal vessels. OCT (B) showing a preserved foveal contour without changes in the retinal layers. OCT (D) revealing a large retinal pigment epithelium detachment with a lobular appearance. Fluorescein angiography (E and F) and indocyanine green angiography (G and H) displaying the polypoidal macular neovascularization.

Figure 11. Multimodal imaging of choroidal nevi complicated by neovascularization. Fundus photography (A) revealing the peripapillary choroidal nevus. Indocyanine green angiography (B) and optical coherence tomography angiography (C) showing the polypoidal neovascularization. Fundus photography (D) revealing the choroidal nevus along the superior temporal vascular arcade. Optical coherence tomography (E) displaying flow signal within the sub-retinal pigment epithelium detachment. Optical coherence tomography angiography showing the Type 1 neovascularization (F).

mor and can be identified in approximately 6.5% of eyes as a flat or slightly elevated, well-defined mass, ranging in color from brown to gray, located deep within the retina.47,48 These lesions are benign in nature, with a low potential for visual loss or growth into melanoma.48,49

Predictive factors for central visual loss over time include the primary location of the lesion and secondary changes in overlying retina and RPE, including foveal edema, subretinal fluid, RPE detachment, orange pigment and MNV formation.50-52 Recognizing the characteristics of MNV associated with a choroidal nevus is important, as it can easily be misinterpreted as a sign of malignant transformation into melanoma. The diagnosis of MNV related to the nevus

Figure 12. Multimodal imaging of choroidal osteoma complicated by neovascularization. Infrared reflectance (A and B) showing the peripapillary lesions and indocyanine green angiography (C and D) revealing the hypofluorescent area of bilateral choroidal osteoma. In the left eye, blue fundus autofluorescence (E) showing a temporal hypoautofluorescent area related to and optical coherence tomography angiography (C) showing the polypoidal neovascularization. Fundus photography (D) revealing the choroidal nevus along the superior temporal vascular arcade. Optical coherence tomography (E) displaying flow signal within the sub-retinal pigment epithelium detachment. Optical coherence tomography angiography showing the Type 1 neovascularization (F).

is typically performed with multimodal imaging, including OCT, ICGA, FA and OCTA, to assess the location and size of the MNV in relation to the nevus and the fovea, and plan the appropriate treatment.52 (Figure 11) MNV may occur also in the context of choroidal osteoma.53 Choroidal osteoma is a rare, benign ossifying tumor of the choroid of unknown etiology. MNV is a significant cause of vision loss in patients with choroidal osteoma, and it has been reported to develop in 31% of affected eyes within 10 years.54,55 The mechanism though which MNV develops is primarily considered to be the disruption of the RPE with thinning of Bruch’s membrane and the choriocapillaris, that allows for the concurrent growth of underlying new choroidal vessels, or the osteoma itself may have extensions of the neovascular membrane.56,57 (Figure 12) Various treatments for MNV associated with choroidal osteoma have been explored, including laser photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, transpupillary thermotherapy, surgical excision and anti-VEGF therapy..58-60 For extrafoveal tumors, serial intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy should be administered

Figure 13. Multimodal imaging of macular neovascularization and punctate inner choroidopathy.

Fluorescein angiography (A and B) and indocyanine green angiography (C) showing the macular neovascularization with leakage in the late phase (B). Fundus autofluorescence (D) displaying the atrophic changes of the outer retina and retinal pigment epithelium. OCT showing the subretinal hyperreflective material related to the macular neovascularization and the spot subretinal hyperreflective material with the cone of hypertransmission.

monthly until control is achieved, followed by consolidation with photodynamic therapy. For subfoveal disease, monthly intravitreal anti-VEGF injections are recommended until control is established, with a treat-and-extend approach to minimize treatment burden. Photodynamic therapy should generally be avoided in cases of subfoveal MNV, as photoreceptor loss due to decalcification may result in limited visual acuity. Most patients with choroidal osteoma can be managed with observation the treatment criteria outlined above apply only in cases of active MNV.60

MNV may develop as a complication of chorioretinal inflammation. In this context, MNV may be the first presenting sign of posterior uveitis or may develop in patients with a prior diagnosis.61 MNV can occur in a wide range of uveitis cases, including both infectious and non-infectious etiologies. Distinguishing inflammatory MNV from other forms may be useful due to the implications for managing both the condition and the associated uveitis. The proposed mechanism for the development of inflammatory MNV involves focal disruption of the RPE caused by infection or inflammation, which leads to growth and invasion of new vessels into the outer retinal space.62,63 The most common cause of inflammatory MNV is punctate inner choroidopathy. Other conditions that may be complicated by the development of MNV include multifocal choroiditis, serpiginous choroiditis, presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome, toxoplasma retinochoroiditis, and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease.64 In this context, a detailed patient anamnesis and multimodal imaging analysis, including the recently introduced OCTA technology, are highly valuable for diagnosing and managing inflammatory MNV. Central vision loss due to MNV compromises patients’ ability to engage in certain types of work and daily activities. Considering that uveitis often affects individuals of working age, inflammatory MNV frequently impacts patients during their most productive and active years.64 Patients with inflammatory MNV exhibit some differences compared to other conditions such as AMD. In AMD, MNV can present as Type 1, Type 2 or Type 3 lesions, while the inflammatory MNV typically manifests as Type 2 lesions.65,66 In AMD, MNV is usually subfoveal and associated with the presence of drusen, pigmentary changes, and RPE abnormalities, while in inflammatory MNV, the RPE is often intact. Moreover, inflammatory MNV lesions are highly focal and may respond to fewer injections compared to AMD patients, who often require ongoing VEGF suppression with multiple injections.67 In patients with inflammatory MNV, inflammation drives lesion development, and with adequate inflammation control, the neovascular drive may subside. Management of the underlying uveitis typically involves systemic steroids or steroid-sparing immunosuppressive therapy, combined with the MNV management requiring anti-vascular growth factor agents, with or without concurrent anti-inflammatory and/or corticosteroid therapy.

References

1. Spaide RF, Jaffe GJ, Sarraf D, et al. Consensus Nomenclature for Reporting Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Data: Consensus on Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Nomenclature Study Group. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(5):616-636. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.11.004

2. Grossniklaus HE, Green WR. Choroidal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(3):496-503. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2003.09.042

3. JD G. Stereoscopic Atlas of Macular Diseases. 4th ed. St.; 1997.

4. Yannuzzi LA, Slakter JS, Sorenson JA, Guyer DR, Orlock DA. Digital indocyanine green videoangiography and choroidal neovascularization. Retina. 1992;12(3):191-223.

5. Freund KB, Zweifel SA, Engelbert M. Edirorial: Do we need a new classification for choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration? Retina. 2010;30(9):1333-1349. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181e7976b

6. Yannuzzi LA, Negrão S, Iida T, et al. Retinal angiomatous proliferation in age-related macular degeneration. 2001. Retina. 2012;32 Suppl 1:416-434.

7. Chen L, Li M, Messinger JD, Ferrara D, Curcio CA, Freund KB. Recognizing Atrophy and Mixed-Type Neovascularization in Age-Related Macular Degeneration Via Clinicopathologic Correlation. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020;9(8):8. doi:10.1167/tvst.9.8.8

8. Curcio CA, Balaratnasingam C, Messinger JD, Yannuzzi LA, Freund KB. Correlation of Type 1 Neovascularization Associated With Acquired Vitelliform Lesion in the Setting of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(5):10241033.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.08.001

9. Bhutto I, Lutty G. Understanding age-related macular degeneration (AMD): relationships between the photoreceptor/retinal pigment epithelium/Bruch’s membrane/choriocapillaris complex. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33(4):295-317. doi:10.1016/j. mam.2012.04.005

10. Biesemeier A, Taubitz T, Julien S, Yoeruek E, Schraermeyer U. Choriocapillaris breakdown precedes retinal degeneration in age-related macular degeneration. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(11):2562-2573. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.05.003

11. Scharf J, Corradetti G, Corvi F, Sadda S, Sarraf D. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography of the Choriocapillaris in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J Clin Med. 2021;10(4). doi:10.3390/jcm10040751

12. Corvi F, Su L, Sadda SR. Evaluation of the inner choroid using OCT angiography. Eye (Lond). 2021;35(1):110-120. doi:10.1038/ s41433-020-01217-y

13. Chu Z, Zhang Q, Gregori G, Rosenfeld PJ, Wang RK. Guidelines for imaging the choriocapillaris using OCT angiography. Am J Ophthalmol. Published online September 2020. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2020.08.045

14. Corvi F, Tiosano L, Corradetti G, et al. CHORIOCAPILLARIS FLOW DEFICITS AS A RISK FACTOR FOR PROGRESSION OF AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION. Retina. 2021;41(4):686-693. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002990

15. Corvi F, Corradetti G, Sadda SR. Correlation between the Angiographic Choriocapillaris and the Structural Inner Choroid. Curr Eye Res. 2021;46(6):871-877. doi:10.1080/02713683.2020.1846756

16. Inoue M, Jung JJ, Balaratnasingam C, et al. A Comparison Between Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography and Fluorescein Angiography for the Imaging of Type 1 Neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(9):OCT314-23. doi:10.1167/ iovs.15-18900

17. Jia Y, Bailey ST, Wilson DJ, et al. Quantitative optical coherence tomography angiography of choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(7):1435-1444. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.01.034

18. Forster JC, Harriss-Phillips WM, Douglass MJ, Bezak E. A review of the development of tumor vasculature and its effects on the tumor microenvironment. Hypoxia (Auckland, NZ). 2017;5:21-32. doi:10.2147/HP.S133231

19. Rispoli M, Savastano MC, Lumbroso B. Quantitative Vascular Density Changes in Choriocapillaris Around CNV After Anti-VEGF Treatment: Dark Halo. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2018;49(12):918-924. doi:10.3928/23258160-2018120302

20. Scharf JM, Corradetti G, Alagorie AR, et al. Choriocapillaris Flow Deficits and Treatment-Naïve Macular Neovascularization Secondary to Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020;61(11):11. doi:10.1167/iovs.61.11.11

21. Alagorie AR, Verma A, Nassisi M, et al. QUANTITATIVE ASSESSMENT OF CHORIOCAPILLARIS FLOW DEFICITS SURROUNDING CHOROIDAL NEOVASCULAR MEMBRANES. Retina. Published online July 2020. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002878

22. Moult E, Choi W, Waheed NK, et al. Ultrahigh-speed swept-source OCT angiography in exudative AMD. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2014;45(6):496-505. doi:10.3928/23258160-20141118-03

23. Alagorie AR, Verma A, Nassisi M, Sadda SR. Quantitative Assessment of Choriocapillaris Flow Deficits in Eyes with Advanced Age-Related Macular Degeneration Versus Healthy Eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;205:132-139. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2019.04.037

24. Corvi F, Corradetti G, Tiosano L, McLaughlin JA, Lee TK, Sadda SR. Topography of choriocapillaris flow deficit predicts development of neovascularization or atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol = Albr von Graefes Arch fur Klin und Exp Ophthalmol. Published online April 2021. doi:10.1007/s00417-021-05167-3

25. Corvi F, Cozzi M, Corradetti G, Staurenghi G, Sarraf D, Sadda SR. Quantitative assessment of choriocapillaris flow deficits in eyes with macular neovascularization. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol = Albr von Graefes Arch fur Klin und Exp Ophthalmol. Published online January 2021. doi:10.1007/s00417-020-05056-1

26. Ferris FL 3rd, Fine SL, Hyman L. Age-related macular degeneration and blindness due to neovascular maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill 1960). 1984;102(11):1640-1642. doi:10.1001/archopht.1984.01040031330019

27. Seko Y, Seko Y, Fujikura H, Pang J, Tokoro T, Shimokawa H. Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor after application of mechanical stress to retinal pigment epithelium of the rat in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(13):3287-3291.

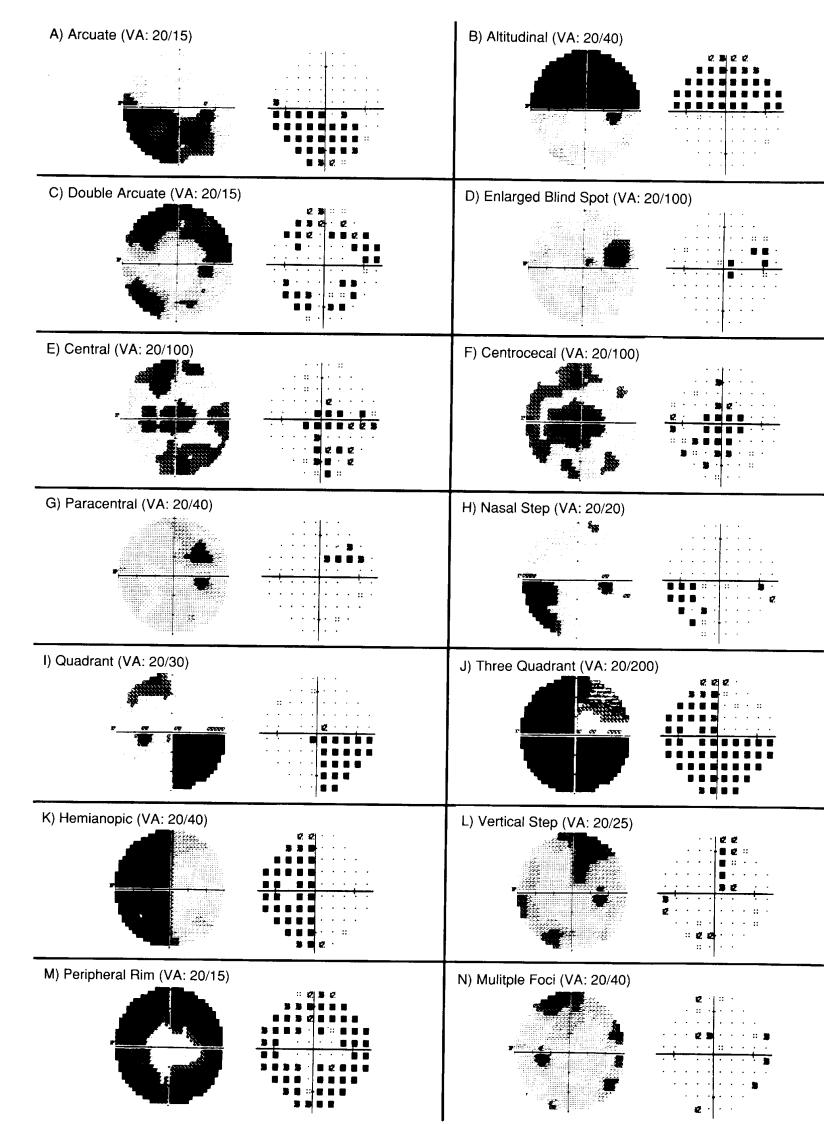

28. Ohno-Matsui K, Shimada N, Yasuzumi K, et al. Long-term development of significant visual field defects in highly myopic eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(2):256-265.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2011.01.052

29. Ohno-Matsui K, Ito M, Tokoro T. Subretinal bleeding without choroidal neovascularization in pathologic myopia. A sign of new lacquer crack formation. Retina. 1996;16(3):196-202. doi:10.1097/00006982-199616030-00003

30. Querques G, Corvi F, Balaratnasingam C, et al. Lacquer Cracks and Perforating Scleral Vessels in Pathologic Myopia: A Possible Causal Relationship. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(4). doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.07.017

31. Photodynamic therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in pathologic myopia with verteporfin. 1-year results of a randomized clinical trial--VIP report no. 1. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(5):841-852. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00544-9

32. Wolf S, Balciuniene VJ, Laganovska G, et al. RADIANCE: a randomized controlled study of ranibizumab in patients with choroidal neovascularization secondary to pathologic myopia. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(3):682-92.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.10.023

33. Ergun E, Tittl M, Stur M. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin in subfoveal choroidal neovascularization secondary to

Age-related macular degeneration and other causes of macular neovascularization

central serous chorioretinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill 1960). 2004;122(1):37-41. doi:10.1001/archopht.122.1.37

34. Cakir M, Cekiç O, Yilmaz OF. Photodynamic therapy for iatrogenic CNV due to laser photocoagulation in central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmic surgery, lasers imaging Off J Int Soc Imaging Eye. 2009;40(4):405-408. doi:10.3928/1542887720096030-10

35. Zayit-Soudry S, Moroz I, Loewenstein A. Retinal Pigment Epithelial Detachment. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(3):227-243. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.02.008

36. Pang CE, Freund KB. Pachychoroid neovasculopathy. Retina. 2015;35(1):1-9. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000000331

37. Ament CS, Zacks DN, Lane AM, et al. Predictors of visual outcome and choroidal neovascular membrane formation after traumatic choroidal rupture. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill 1960). 2006;124(7):957-966. doi:10.1001/archopht.124.7.957

38. Preziosa C, Corvi F, Pellegrini M, Bochicchio S, Rosar AP, Staurenghi G. OPTICAL COHERENCE TOMOGRAPHY ANGIOGRAPHY FINDINGS IN A CASE OF CHOROIDAL NEOVASCULARIZATION SECONDARY TO TRAUMATIC CHOROIDAL RUPTURE. Retin cases & Br reports. 2020;14(4). doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000000704

39. Chatziralli I, Saitakis G, Dimitriou E, et al. ANGIOID STREAKS: A Comprehensive Review From Pathophysiology to Treatment. Retina. 2019;39(1):1-11. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002327

40. Shah M, Amoaku WMK. Intravitreal ranibizumab for the treatment of choroidal neovascularisation secondary to angioid streaks. Eye (Lond). 2012;26(9):1194-1198. doi:10.1038/eye.2012.116

41. Mansour AM, Ansari NH, Shields JA, Annesley WHJ, Cronin CM, Stock EL. Evolution of angioid streaks. Ophthalmol J Int d’ophtalmologie Int J Ophthalmol Zeitschrift fur Augenheilkd. 1993;207(2):57-61. doi:10.1159/000310407

42. Charbel Issa P, Gillies MC, Chew EY, et al. Macular telangiectasia type 2. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2013;34:49-77. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.11.002

43. Gass JD, Blodi BA. Idiopathic juxtafoveolar retinal telangiectasis. Update of classification and follow-up study. Ophthalmology. 1993;100(10):1536-1546.

44. Charbel Issa P, Scholl HPN, Gaudric A, et al. Macular full-thickness and lamellar holes in association with type 2 idiopathic macular telangiectasia. Eye (Lond). 2009;23(2):435-441. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6703003

45. Davidorf FH, Pressman MD, Chambers RB. Juxtafoveal telangiectasis-a name change? Retina. 2004;24(3):474-478. doi:10.1097/00006982-200406000-00028

46. Engelbrecht NE, Aaberg TMJ, Sung J, Lewis M Lou. Neovascular membranes associated with idiopathic juxtafoveolar telangiectasis. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill 1960). 2002;120(3):320-324. doi:10.1001/archopht.120.3.320

47. Sumich P, Mitchell P, Wang JJ. Choroidal nevi in a white population: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill 1960). 1998;116(5):645-650. doi:10.1001/archopht.116.5.645

48. Shields CL, Furuta M, Mashayekhi A, et al. Clinical spectrum of choroidal nevi based on age at presentation in 3422 consecutive eyes. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(3):546-552.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.07.009

49. Qiu M, Shields CL. Choroidal Nevus in the United States Adult Population: Racial Disparities and Associated Factors in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(10):2071-2083. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.06.008

50. Shields CL, Furuta M, Mashayekhi A, et al. Visual acuity in 3422 consecutive eyes with choroidal nevus. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill 1960). 2007;125(11):1501-1507. doi:10.1001/archopht.125.11.1501

51. Waltman DD, Gitter KA, Yannuzzi L, Schatz H. Choroidal neovascularization associated with choroidal nevi. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;85(5 Pt 1):704-710. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77109-0

52. Pellegrini M, Corvi F, Say EAT, Shields CL, Staurenghi G. OPTICAL COHERENCE TOMOGRAPHY ANGIOGRAPHY FEATURES OF CHOROIDAL NEOVASCULARIZATION ASSOCIATED WITH CHOROIDAL NEVUS. Retina. 2018;38(7):1338-1346. doi:10.1097/ IAE.0000000000001730

53. Kadrmas EF, Weiter JJ. Choroidal osteoma. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1997;37(4):171-182. doi:10.1097/00004397-199703740-00015

54. Alameddine RM, Mansour AM, Kahtani E. Review of choroidal osteomas. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2014;21(3):244-250. doi:10.4103/0974-9233.134686

55. Shields CL, Sun H, Demirci H, Shields JA. Factors predictive of tumor growth, tumor decalcification, choroidal neovascularization, and visual outcome in 74 eyes with choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill 1960). 2005;123(12):1658-1666. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.12.1658

56. Shields CL, Shields JA, Augsburger JJ. Choroidal osteoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988;33(1):17-27. doi:10.1016/0039-6257(88)90069-0

57. Foster BS, Fernandez-Suntay JP, Dryja TP, Jakobiec FA, D’Amico DJ. Clinicopathologic reports, case reports, and small case series: surgical removal and histopathologic findings of a subfoveal neovascular membrane associated with choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill 1960). 2003;121(2):273-276. doi:10.1001/archopht.121.2.273

58. Blaise P, Duchateau E, Comhaire Y, Rakic J-M. Improvement of visual acuity after photodynamic therapy for choroidal neovascularization in choroidal osteoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2005;83(4):515-516. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00479.x

59. Shukla D, Tanawade RG, Ramasamy K. Transpupillary thermotherapy for subfoveal choroidal neovascular membrane in choroidal osteoma. Eye (Lond). 2006;20(7):845-847. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6702016

60. Khan MA, DeCroos FC, Storey PP, Shields JA, Garg SJ, Shields CL. Outcomes of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in the management of choroidal neovascularization associated with choroidal osteoma. Retina. 2014;34(9):1750-1756. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000000187

61. Agarwal A, Invernizzi A, Singh RB, et al. An update on inflammatory choroidal neovascularization: epidemiology, multimodal imaging, and management. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2018;8(1):13. doi:10.1186/s12348-018-0155-6

62. Gass JD. Pathogenesis of tears of the retinal pigment epithelium. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68(8):513-519. doi:10.1136/bjo.68.8.513

63. Grossniklaus HE, Gass JD. Clinicopathologic correlations of surgically excised type 1 and type 2 submacular choroidal neovascular membranes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126(1):59-69. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00145-7

64. Baxter SL, Pistilli M, Pujari SS, et al. Risk of choroidal neovascularization among the uveitides. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156(3):468-477.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2013.04.040

65. Told R, Sacu S, Hecht A, et al. Comparison of SD-Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography and Indocyanine Green Angiography in Type 1 and 2 Neovascular Age-related Macular Degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(6):2393-2400. doi:10.1167/iovs.17-22902

66. Corvi F, Cozzi M, Barbolini E, et al. COMPARISON BETWEEN SEVERAL OPTICAL COHERENCE TOMOGRAPHY ANGIOGRAPHY DEVICES AND INDOCYANINE GREEN ANGIOGRAPHY OF CHOROIDAL NEOVASCULARIZATION. Retina. 2020;40(5):873-880. doi:10.1097/ IAE.0000000000002471

67. Ba J, Peng R-S, Xu D, et al. Intravitreal anti-VEGF injections for treating wet age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:5397-5405. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S86269

Beatrice Tombolini, Maria Vittoria Cicinelli, Rosangela Lattanzio, Francesco Bandello

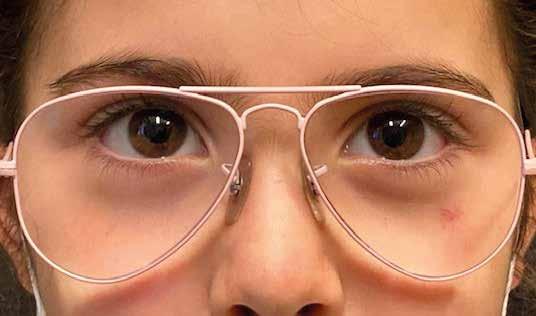

Introduction

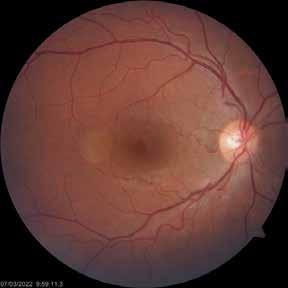

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the most common ocular manifestation of diabetes and the leading cause of blindness among the working-age population in industrialized countries. (1) Clinically, DR is classified as non-proliferative (NPDR) and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), based on the development of anomalous new blood vessels on the retina, optic disc, or iris. Late-stage complications are vitreous hemorrhages, tractional retinal detachment, and neovascular glaucoma. However, the most prevalent cause of vision loss is diabetic macular edema (DME), which may affect all stages of the disease. (2)

Early identification of DR is crucial since symptoms become noticeable only in severe cases. Nowadays, screening procedures employ modern technologies (multimodal imaging, telemedicine, artificial intelligence) to prevent DR-related blindness. (3)

So far, therapeutic management has dramatically changed, shifting from laser photocoagulation being the benchmark treatment to the latest formulations of antiangiogenic intravitreal and slow-release corticosteroid implants. (4)

This chapter provides a comprehensive and up-to-date overview of the epidemiological and clinical characterization of diabetic retinopathy, focusing on its diagnostic, screening, and therapeutic management.

The prevalence of diabetes is steadily and undoubtedly rising worldwide. It is estimated that by 2045 diabetes will affect 783 million people aged 20 to 79, representing 12.2% of the global adult population.(5) Similarly, its global prevalence and disease burden are expected to increase significantly, reaching 130 million by 2030, and further rising to 161 million by 2045. This trend is attributed to several factors, including growing global prevalence of diabetes, lifestyle changes, and aging of the global population. Concurrently, a geographic shift is becoming evident. Projections by 2030 suggest that DR prevalence will grow at comparatively modest rates (10.8-18.0%) in traditionally affluent areas (North America and Europe), while in middle- and low-income regions (Western Pacific, South and Central America, Asia, Africa, Middle East and North Africa), these rates will be substantially higher (20.6-47.2%). The most recent meta-analysis (2020-2021) estimated a global prevalence of DR at 103 million (22.3% of DM population). (6) In Europe, the prevalence of DR was slightly below global values (18.8%). In 2016, the number of Italian diabetic patients reached 3.5 million (5.5% of total population), with one-third aged 65 and above. So far, there is no national data on the prevalence and incidence of legal blindness in patients with diabetes or DR, although available data are consistent with European reports. (7)

The incidence of diabetic retinopathy may vary based on insulin dependence, with a higher frequency in type 1 rather than type 2 diabetes (39-59% vs 3.8-38.6%, respectively). (8) The most

Diabetes Control and Complications Trial

DCCT

Follow-up study to the DCCT titled Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications EDIC

Diabetic Retinopathy Study

Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study

Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy

Diabetic Retinopathy Vitrectomy Study

Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes

Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network

United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study

Table 1. Studies (from 1970 to nowadays) about risk factors and natural history of DR.

DRS

ETDRS

WESDR

DRVS

FIELD

DRCR.net

UKPDS

important risk factors for the onset and progression of DR include longer diabetes duration, higher levels of glycated hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] , male sex, and higher blood pressure. (9)

The studies that have investigated the risk factors and the natural history of DR from 1970 to the present are listed in Table 1.

Pathogenesis and classification

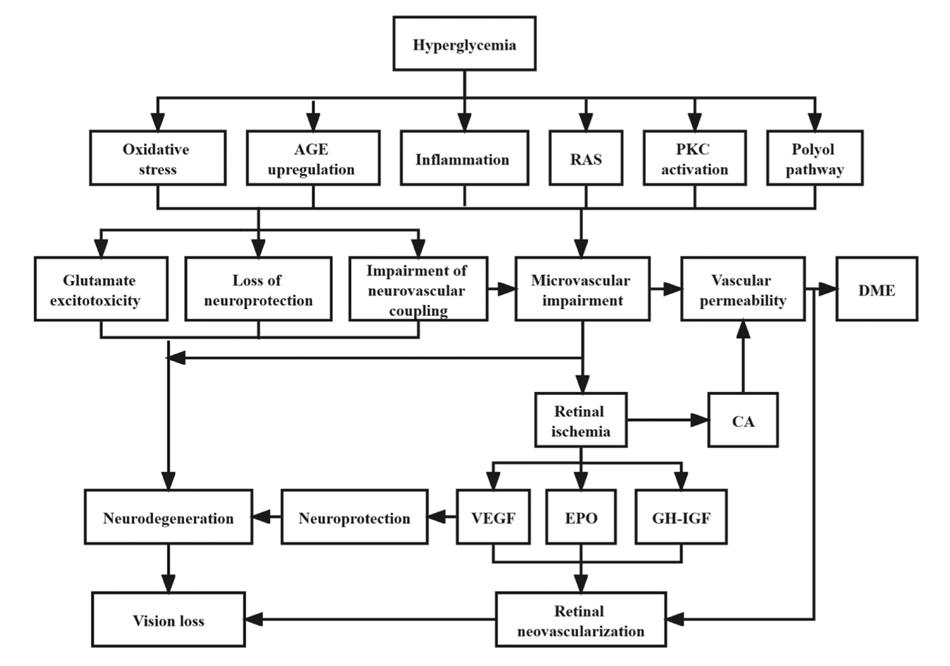

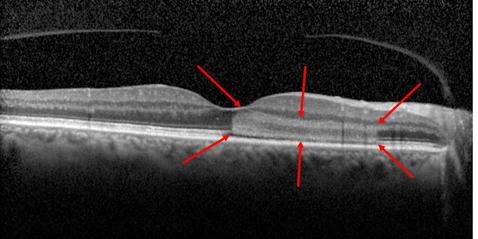

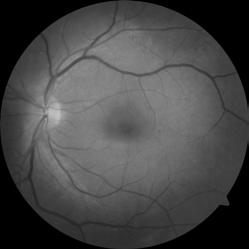

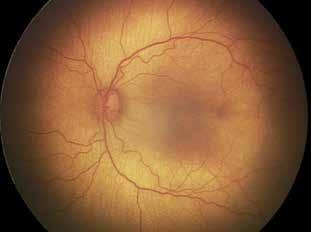

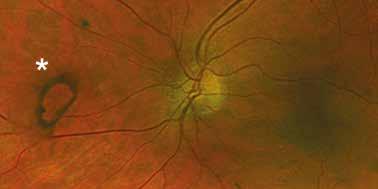

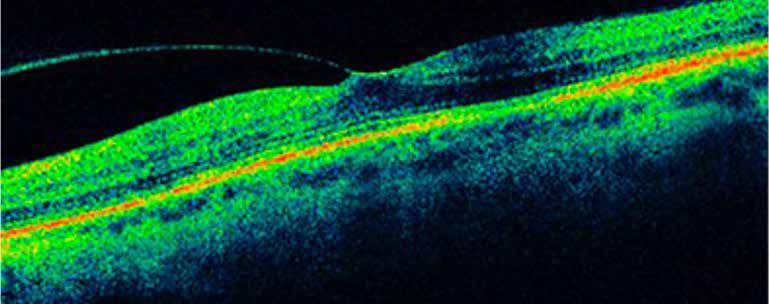

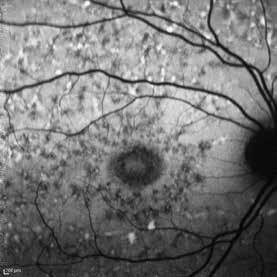

The pathogenesis of DR and DME is complex (Figure 1). Chronic hyperglycemia may activate metabolic pathways (e.g. polyol, protein kinase C, advanced glycosylation end products,

Figure 1. Summary of etiopathogenetic pathways in DR and DME (Courtesy of Yang Z et al. Front Endocrinol [Lausanne], 2022)

[AGEs]), cellular processes (oxidative stress), neuroinflammation, and the renin-angiotensin system. Increasing evidence indicates that the traditional view of DR as purely microvascular disease is inaccurate, since retinal neurodegeneration occurs concurrently or even precedes vascular damage in the early stages, without detectable DR. The imbalance between upregulated neurotoxic (e.g. glutamate) and downregulated neurotrophic (e.g. pigment epithelium-derived factor, PEDF) mediators lead to apoptosis and reactive gliosis, resulting in retinal ganglion cell layer (GCL) and nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thinning. To counteract this process, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other mediators (erythropoietin, insulin-like growth factor, growth hormone, and angiopoietin) are overexpressed, linking neurodegeneration to neurovascular unit impairment and breakdown of the inner blood–retina barrier (BRB).

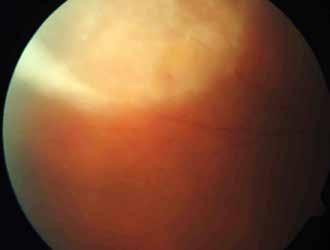

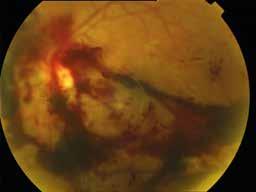

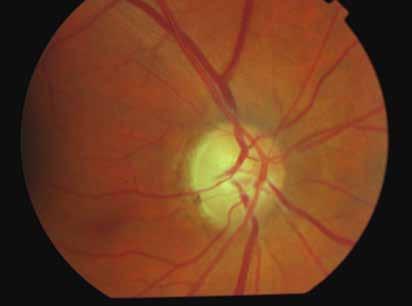

Early non-proliferative microvascular damage includes thickening of the basement membrane, disruptions of the tight junctions and loss of pericyte clinically corresponding to microaneurysms and intraretinal hemorrhages (dot, blot, flamed-shaped). Subsequently, hypoxia and capillary occlusion are favored by the predominance of vasoconstrictors agents and maladaptive vascular remodeling. Thus, severe NPDR displays retinal ischemia starting from periphery towards the macula (diabetic macular ischemia, [DMI]), retinal infarction (cotton wool spots), dilated capillaries and shunts between arteries and veins (intraretinal microvascular abnormalities, [IRMA]) and anomalous veins (dilated, tortuous and irregular in caliber). In late stages of PDR, the hypoxic environment creates an imbalance of angiogenic (e.g. VEGF) over anti-angiogenic (e.g. PEDF) mediators, resulting in neovascularization (NV) sprouting on the optic disc (NVD), the retina, the iris and the angle (neovascular glaucoma). Due to their structural weakness, these new vessels are more likely to bleed spontaneously (vitreous and preretinal hemorrhage), and adhere to the vitreous body. Over time, adventitial fibrotic component develops and contracts, forming epiretinal membranes (ERM), vitreomacular traction (VMT), and ultimately tractional retinal detachment. (2,3) Notably, DME may occur during both NPDR and PDR. DME manifests as retinal thickening due to the accumulation of intraretinal fluid and/or extracellular lipid leakage (hard exudates) in the outer plexiform layer. Several mechanisms, including VEGF, have been proposed, all converging on the internal breakdown of the BRB due to increased capillary permeability and vascular leakage (10) Additionally, vitr-

Disease severity level

No apparent DR (level 10)

Mild NPDR (level 20)

Moderate NPDR (levels 47-35)

Severe NPDR (1-2-4 rule) (level 53)

PDR (levels 85-60)

Findigns observable upon dilated ophthalmoscopy

No abnormalities

Microaneurysms only

More than just microaneurism, but less than severe NPDR:

– retinal hemorrhages;

– hard hexudates;

– cotton wool spots;

No signs of PDR & any of the following:

– ≥ 20 intraretinal hemorrhages in each of 4 quadrants;

– Definite venous beading in ≥ 2 quadrants;

– Prominent IRMA in ≥ 1 quadrant;

≥ 1 of following signs:

– Neovascularization;

– Vitreous/preretinal hemorrhages;

Table 2. International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy (ICDR) severity scale of DR. (20) Abbreviations: IRMA intraretinal microvascular abnormalities; NPDR non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR proliferative diabetic retinopathy

eomacular interface abnormalities (ERM, VMT, and macular hole) may be detected in chronic DME. (11) Furthermore, diabetes may also impact on the choroidal vasculature (diabetic choroidopathy), mainly affecting the choriocapillaris by vascular dropout and vessel tortuosity. (12–14) Interestingly, alterations in the choroidal vasculature may precede the onset of DR. (15,16)

Several clinical classifications of DR and DME have been proposed. Color fundus photographs (CFP) have been used to classify DR since early grading systems (e.g. Hammersmith and Airlie House). (3) The ETDRS severity scale classified individual fundus lesions on stereoscopic 7-field 30° CFP, thereby quantifying the overall retinopathy severity in 14 levels (10-85). (17) Despite being “the gold standard” classification, its clinical use has been restricted to research settings due to its complexity. (18) The WESDR study group proposed an alternative system, assigning severity levels (1-7) based on the most severe DR across all 7 photographic fields. (19)

Today, the International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy (ICDR) severity scale, developed from ETDRS and WESDR models and based on ophthalmoscopy, is the most commonly used classification in daily clinical practice (Table 2). (20)

Notably, DRS trial classified PDR as “high-risk”, as the patient, if not treated urgently, is at high risk of severe visual loss, based on presence of 3 of following features:

Neovascularization of disc (NVD) larger than one-third to one-fourth disc diameter;

NVD smaller than one-third to one-fourth disc diameter with vitreous/pre-retinal hemorrhage;

Neovascularization of elsewhere (NVE) with vitreous/pre-retinal hemorrhage (21,22)

Multimodal imaging findings and biomarkers

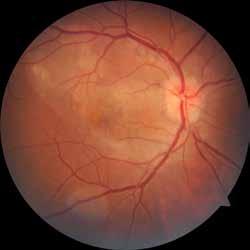

Traditionally, the gold-standard diagnostic methods for DR and DME were CFP and fluorescein angiography (FA). Recently, multimodal imaging approaches also revolutionized the diagnosis and management of DR and DME through application of non-invasive modalities, including OCT, OCT angiography (OCT-A), ultra-wide field (UWF) techniques (retinography, FA, OCT,

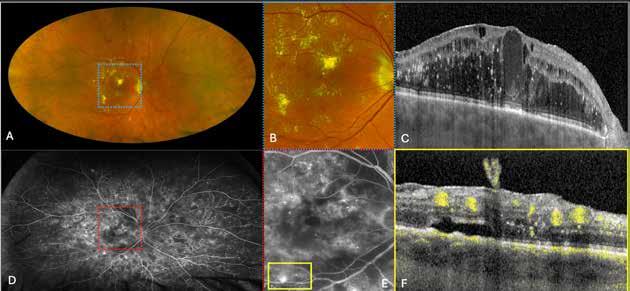

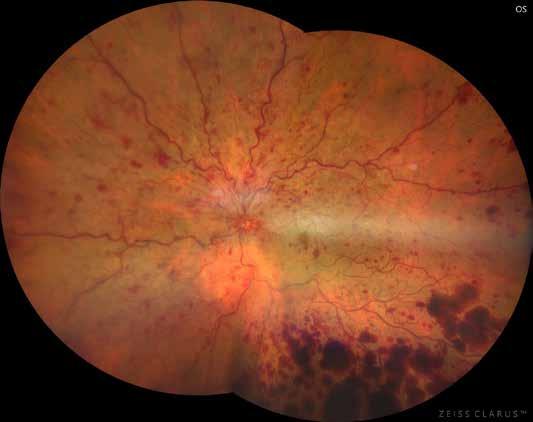

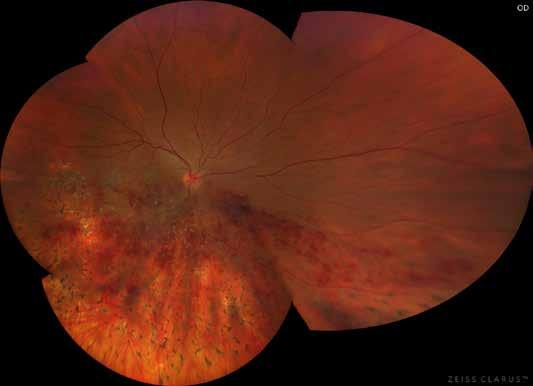

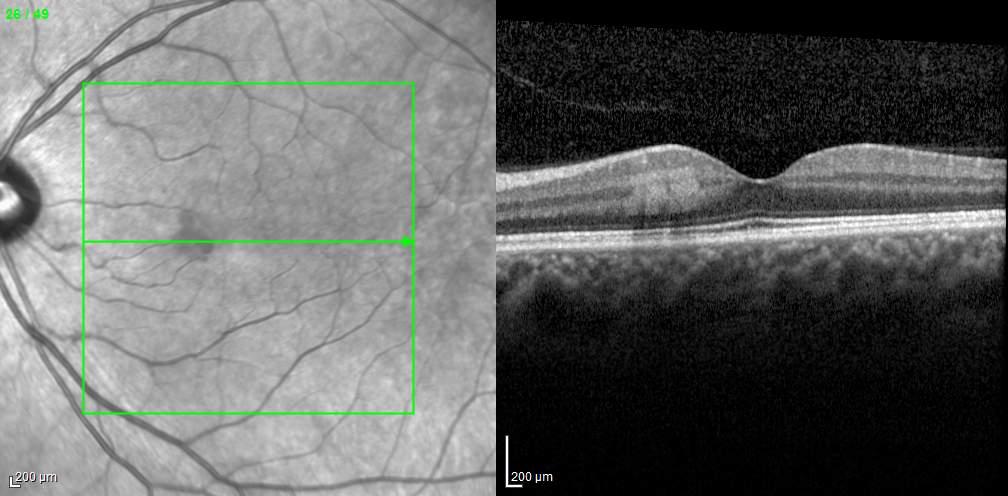

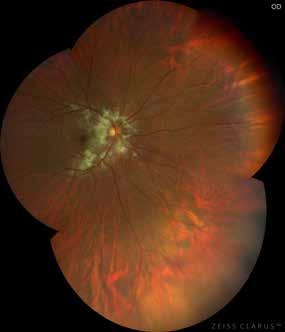

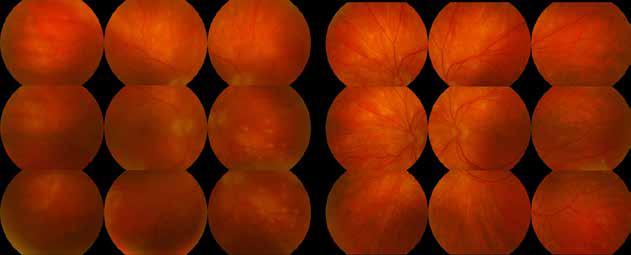

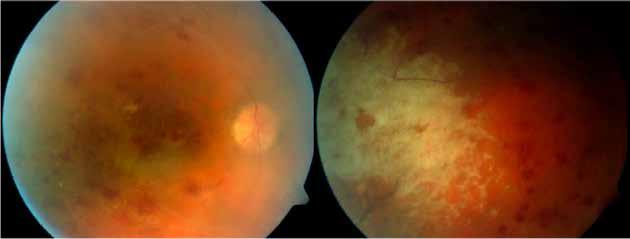

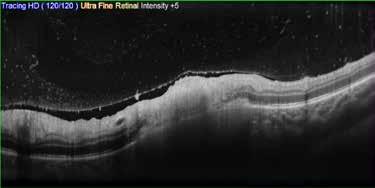

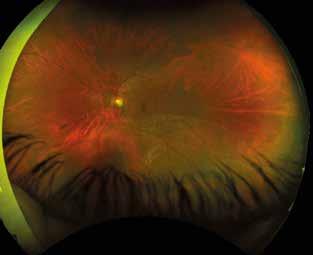

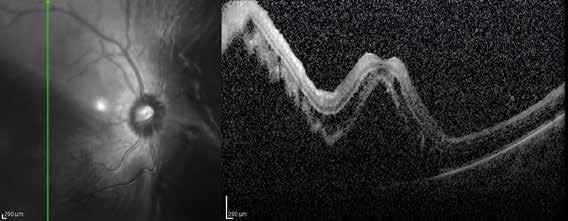

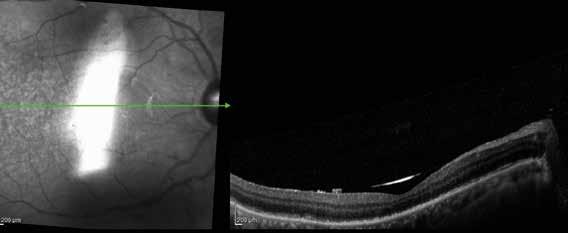

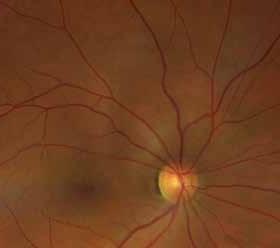

Figure 2. Multimodal imaging of right eye of a male diabetic patient affected by PDR and DME. 2A-B) UWF pseudocolor retinography (Optos Silverstone, Optos, UK) and corresponding magnification of macular region showing diffuse hard exudates and intraretinal hemorrages; 2C) OCT (Heidelberg Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering Inc., Germany) displaying diffuse center-involving DME; 2D-E) Late phase UWF FA (Optos Silverstone, Optos, UK) and corresponding magnification of macular region presenting extense breakdown of BRB with perivascular leakage and non-perfusion areas, pooling effect compatible with MA and masking effect due to pre-retinal hemorrhages. Two leakage spots associated to possible NVs close to inferior vascular arcade; 2F) 3x3 B-scan OCT-A (Zeiss PLEX Elite 9000, Carl Zeiss, Germany) showing flow signal within pre-retinal NV.

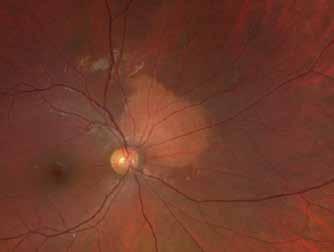

Figure 3. Multimodal imaging of a male diabetic patient affected by PDR and DME that has already been treated by incomplete laser photocoagulation therapy. 3A) UWF pseudocolor retinography displaying hard exudates and intraretinal hemorrhages within vascular arcades and peripheral laser photocoagulation therapy; 3B) UWF SS-OCT showing focal center-involving DME; 3C) Late phase UWF FA (describing mild BRB disruption with 2 leakage areas compatible with NV along inferior vascular arcade; 3D) 15x15 En-face WF-SS-OCTA presenting FAZ enlargement, diffuse capillary drop-out and temporal mid-peripheral retinal nonperfusion areas, and two pathological vascular networks associated to NVs.

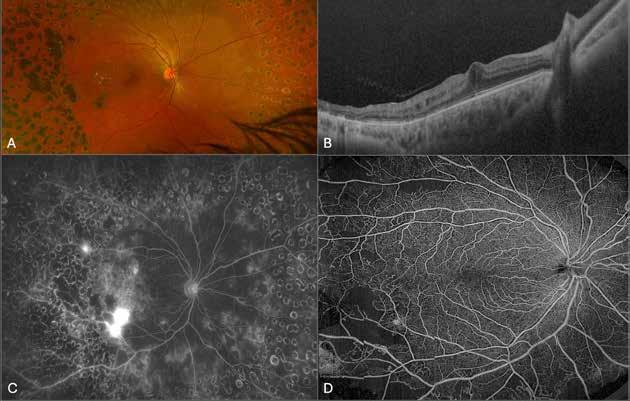

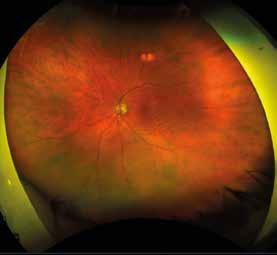

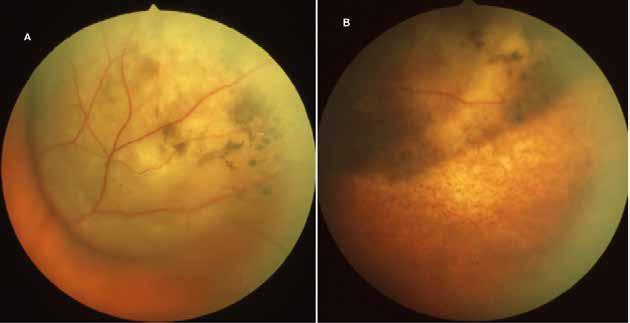

Figure 4. Multimodal imaging of a female diabetic patient affected by PDR that has already undergone complete laser photocoagulation treatment. 4A) UWF pseudocolor retinography showing complete laser photocoagulation treatment until vascular arcades; 4B-C) 12x12 and 4E-F) en-face WF-SS-OCTA of diabetic patient (4B, 4E) presenting FAZ enlargement, diffuse capillary drop-out and inferior mid-peripheral retinal nonperfusion areas, as compared to healthy patient (4C, 4F; 4D) Late phase UWF FA displaying diffuse BRB breakdwon, with perivascular leakage and non-perfusion areas.

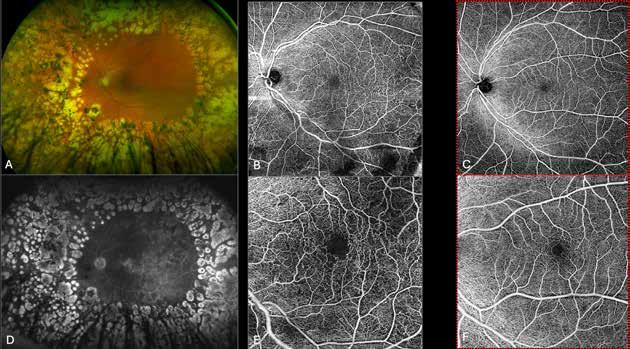

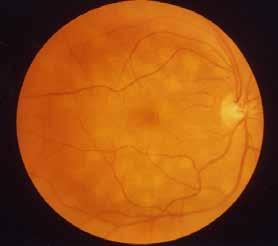

5. Multimodal imaging of a

diabetic patient affected by

5A) UWF pseudocolor retinography showing some hard exudates within and outside vascular arcades; 5B) Late phase UWF FA presenting far peripheral BRB rupture, with associated perivascular leakage and retinal ischemia, and diffuse pooling effect within telengectasic vessels; 5C) UWF SS-OCT, displaying some hard exudates close to optic disc.

OCT-A) (Figures 2-5).

For many decades, color fundus photography has been crucial for the diagnosing and management of diabetic retinopathy. The ETDRS 7 standard fields protocol, considered the gold standard, uses a traditional fundus camera to capture 30° of the retinal surface at a time, combining seven images in fixed position (4 around the optic nerve, 3 across the macula). However, 7SF displayed several drawbacks, including the need of highly skilled operators and a fully collaborative patient, the necessary mydriasis, and the inability to simultaneously image the entire retina. (23) In addition, a single 45° CFP scan provides data from only 15% of the retinal surface area, whereas 7SF covers central 90° posteriori region, corresponding to less than 30% of the total retina. (24)

The pseudocolor UWF imaging provides a single-shot field of at least 110° field of view anterior to the vortex vein ampullae in all four quadrants, with no need of mydriasis or contact lenses. Nonetheless, many commercials systems capture up to 200°. (25) About 82% of the total retinal surface is detected, although photomontage may cover almost all retina. (26) UWF retinography has shown a substantial agreement in assessing DR severity, but with a higher detection rate (10%) compared to the 7SF gold-standard. (27) This increased sensitivity may be due to predominantly peripheral lesions (PPLs), corresponding to anomalies (e.g. retinal hemorrhage/MA, IRMA and NVE) located outside the 7SF in more than 30% cases. Among these lesions, hemorrhages/MA were predominant PPL. (28) The presence and extent of PPLs may show a prognostic significance, raising the risk of DR progression. In addition, UWF retinography reduces the percentage of ungradable images by more than 70% and decreases image assessment time by 25%. (29,30) Exploring the peripheral retina

employing UWF imaging may offer useful data for DR progression and classification. However, how this data might be integrated into a new DR classification remains unclear. (3)

Fluorescein angiography can detect different vascular manifestations of DR, such as microaneurysms (MAs), venous beading, BRB impairment, IRMAs, NVs and non-perfusion areas. Specifically, MAs appear as circular hyperfluorescent pinpoints both in the early and late FA phases. Blood–retinal barrier breakdown appears as a diffuse, late-stage hyperfluorescent signal consistent with leakage. IRMAs are tortuous intraretinal vascular abnormalities associated with minimal or no leakage on FA. Retinal NVs may be identified as hyperfluorescent regions with late-stage leakage. Therefore, FA alone may not be sufficient to distinguish small and faintly leaking NVs from IRMAs. Non-perfused regions appear as early hyperfluorescent areas surrounded by large hyperfluorescent retinal vessels. (31) The presence of DMI on FA images is defined as the presence of capillaries and/or arterioles alterations in the macular region, particularly in the fovea. (32) It is important to note that several studies employing FA have demonstrated that DMI tends to aggravate throughout the different stages of DR. (20)

Angiographic evaluation of peripheral retina plays a key role in the screening, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of DR. (33) Wide-field and UWF fluorescein angiography systems have been employed to overcome diagnostic pitfalls of traditional FA, demonstrating several advantages. First, UWFA reveals more retinal surface, peripheral non-perfusion areas, NV, and panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) laser treatments. (34,35) Thus, UWF-FA may better predict DR progression compared to the 7SF, as increased non-perfusion areas on UWF-FA are associated with the presence of PPL. (36,37) Secondly, UWFA ha introduced new qualitative angiographic biomarkers, including white dots and peripheral vascular leakage (PVL). In detail, white dots represent capillary nonperfusion signs without angiographic evidence that have been linked to DR severity. (38) Additionally, UWFA has introduced new qualitative angiographic biomarkers, including white spots and peripheral vascular leakage (PVL). Specifically, white spots indicate areas of capillary non-perfusion without clear angiographic evidence, which have been linked to the severity of DR. (38) On UWFA, PVL corresponds to late leakage, reflecting impairment of BRB in the setting of acute DR. It has been postulated that VEGF upregulation may cause NV growth and BRB disruption both in macular and peripheral retina, leading to macular leakage and PVL, respectively. (39) UWFA introduced novel quantitative biomarkers, such as ischemic index (ISI), defined as ratio between nonperfused areas and total retinal surface, [48] and retinal vascular bed area (RVBA), which calculates area and density occupied by the vessels on binarized UWF-FA images. (40) ISI has been associated with the presence and severity of DME, (41,42) DMI, (43) recurrence of vitreous hemorrhage following vitrectomy (44) and oxygen saturation of retinal arteries. RVBA was found to be correlated with worsening DR severity and presence/absence of DME, but its role as a prognostic metric is unclear. (40) Other quantitative angiographic biomarkers include hemorrhages/MAs count. (45) UWFA also displays a role in DR therapeutic management. With UWFA it is possible to guide targeted laser photocoagulation (TRP) and selectively treat ischemic areas while sparing the perfused retina. For this reason TRP reduces common side effects of standard PRP (e.g. visual acuity reduction, visual field constriction), with similar efficacy in NV regression but less effect on CST. (46,47)

OCT allows the evaluation of a variety of quantitative and qualitative retinal biomarkers in DR and DME (Table 3). Quantitative parameters include central subfoveal thickness (CST) and macular volume. (48) However, the value of CST in a clinical setting is debated, since its cor-

Retinal quantitative parameters

CST Average thickness of the central 1 mm macula centred on the fovea

Macular volume

Retinal qualitative parameters

DRIL

ELM, EZ, IZ integrity

HRF

Average thickness in the 9 paracentral subfields (central subfield, 4 inner subfields and 4 outer subfields) divided by grid area

Indistinguishable boundaries between ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer complex, inner nuclear layer and outer plexiform layer. Assessed on the central 1000 μm

ELM, EZ and IZ are the first, second and third hyperreflective bands, respectively, of the four outer most layers on OCT. Integrity is assessed on the central 1000 μm

Circumscribed hyperreflective foci with similar reflectivity to the RPE layer, absence of back shadowing and <30 μm diameter. Located between the internal limiting membrane and retinal pigment epithelium. Number of HRF is manually counted within the 1500 μm of fovea

Choroidal quantitative parameters

Subfoveal choroidal thickness

CVI

Distance between outer edge of RPE to inner sclera in the subfoveal region

Ratio of luminal area to total circumscribed subfoveal choroidal area in the central 1.5 mm centred on fovea. It is calculated based on binarized OCT images into light and dark pixels

Choroidal quantitative parameters

HCF

Circumscribed hyperreflective foci with reflectivity equal to or higher than that of retinal pigment epithelium, located outer to the retinal pigment epithelium. Number of HCF is manually counted within the 1500 μm of fovea

Table 3. Summary of quantitative and qualitative retinal and choroidal OCT biomarker of DR and DME. (53)

Abbreviations: CST: central subfield thickness; CVI: choroidal vascularity index; DRIL: disorganization of retinal inner layers; ELM: external limiting zone; EZ: ellipsoid zone; HCF: hyperreflective choroidal foci; HRF: hyperreflective retinal foci; IZ: interdigitation zone.

relation with low VA is surprisingly low. (49) A reduction of RNFL and GCL was described in patients affected by DR, as well as in diabetic patients before onset of DR, compared with healthy controls. (48) This biomarker is thought to express diabetic retinal neurodegeneration. (50–52) Conversely, qualitative features are the disorganization of retinal inner layers (DRIL), the disruption of photoreceptors layers such as external limiting membrane (ELM),ellipsoid zone (EZ),interdigitation zone (IZ), and intraretinal hyper-reflective foci (HRF). (53) Some of these tomographic parameters showed prognostic value. HRF (54) and DRIL (55) have been associated with an increase in the progression of DR. Conversely, disruption of ELM (56) and EZ (57) have been related to visual acuity outcomes. Notably, some groups proposed OCT-based classification systems for DME. (58,59)

The European School for Advanced Studies in Ophthalmology (ESASO) classified DME in 4 stages (early, advanced, severe DME and atrophic maculopathy) based on seven OCT quantitative/qualitative biomarkers (TCED-HFV protocol) (Table 4), suggesting a possible progression through different stages of severity. (58)

Beyond diabetic maculopathy, OCT reveals several lesions occurring in the setting of either NPDR (e.g. hard exudates, MA, cotton-wool spots) or PDR (e.g. NV, hemorrhage). (23) Furthermore, subfoveal choroidal thickness (SFCT), choroidal vascularity index (CVI) and hyperreflective choroidal foci (HCF) are imaging markers of diabetic choroidopathy. Conflicting evidence

Thickening (T)

Cysts (C)

EZ and/or ELM status (E)

DRIL (D)

Hyperreflective foci (H)

Subretinal fluid (F)

Vitreoretinal relationship (V)

0 Less than %10 increase above upper normal values

1 More than %10 but less than %30 increase above upper normal values

2 More than %30 increase above upper normal values

0 Absent

1 Mild

2 Moderate

3 Severe

0 Intact

1 Disrupted

2 Absent

0 Absent

1 Present

30 < 0

30 < 1

0 Absent

1 Present

0 Absence of any visivle adhesion or traction between vitreous cortex and retina

1 IVD

2 PVD

3 VMT

4 ERM

Table 4. ESASO OCT-based grading (TCED-HFV protocol) of DME (58) Abbreviations: EZ: ellipsoid zone; ELM: external limiting membrane; DRIL: disorganization of the inner retinal layers; IVD: incomplete posterior vitreous detachment; PVD: posterior vitreous detachment; VMT: vitreomacular traction; ERM: epiretinal membrane.

reported both reduced and increased choroidal thickness in relation to DR and DME severity. (53) CVI may be more compromised in advanced stages of DR and based on different topographic distributions (macular and peripheral), with lower values in macular regions than mid-peripheral regions. (60)

Little evidence about retinal and choroidal anomalies in DR has been produced using UWF SS-OCT. Approximately 24% of IRMA has been found to be NVE, whereas 9% of NVE was found in uncommon areas. Overall, 25% of eyes reported a change in DR severity.. (61) Diabetic choroidopathy was assessed over different DR stages in terms of choroidal vascular index, comparing these calculations with corresponding on SS-OCT. By comparing agreement between two devices in CVI values, a fair correlation was found between macular measurements, but caution was recommended in extreme CVI assessment. (60) Further studies are required to expand current literature on this novel modality.

OCT-A grants in-vivo depth-resolved images of retinal and choroidal vessels, which provide additional diagnostic information over FA. (62,63) OCT-A detects capillary abnormalities (non-perfusion areas, MA, IRMA), venous loop, and NV. (64–69) Retinal nonperfusion may be suspected as well-defined hyporeflective regions surrounded by irregular capillaries. Inter-

estingly, detection rate of non-perfusion areas is higher on OCT-A than FA (64), but similar to values of UWF-FA. (70) OCT-A permits identification and characterization of MA that FA would not reveal. (66) As compared to FA, OCT-A efficiently discriminates between IRMA or NV, based on their topography. In details, while IRMA is totally localized within ischemic retinal regions, NV protrudes into the vitreous. (66,67) OCT angiography may differentiate NV activity according to its morphology. (69) OCT-A parameter of non-perfusion is traditionally the morphology of foveal avascular zone (FAZ), that in diabetic patients is usually enlarged and irregular due to ischemic damage. Conflicting evidence debates about which retinal capillary plexus is primarily affected. (71,72) Nonetheless, wide variability in FAZ size among healthy and diabetic subjects has limited its accuracy in DR. (15) For this reason, several quantitative metrics of retinal perfusion have been introduced, including vessel density (VD), vessel length density (VLD), vessel tortuosity (VT), fractal dimension (FD). (70,73) To provide a better representation on OCT-A of ischemia, several authors proposed a threshold to identify hypoxic tissue, based on distance to the nearest blood vessel (geographic perfusion deficit, [GPD]). (74) Recently, GPD did correlate better with the nonperfusion on UWF-FA, and both these imaging modalities were comparable in detecting clinically referable DR. (70) OCT-A displayed a CC impairment in DR that has been associated with outer damages. (75)

OCT-A has been advocated as screening test to detect early microcirculatory disturbances (FAZ anomalies, reduced VD) in diabetic patient with no detectable DR. (76,77)

Many of these quantitative parameters have related to stage of DR and probability of progression in manifest DR and DME. (78) As examples, both FAZ area and VD have been correlated to visual acuity, (79,80) whereas an higher CC flow deficit has associated to DR progression. (81) Several artifacts could affect this modality: OCT-A devices are limited in the detection of flow, which is slower than a specific threshold (“undetectable flow”). To overcome this limitation, a variable interscan time analysis (VISTA) algorithm was developed. (71) Similarly, flattening the data in a segmented two-dimensional volume may result in flow overestimation, and thus misinterpretation of diabetic vascular anomalies (MA).

WF swept-source OCT-A (WF SS-OCT-A) has been employed in the assessment of DR. Although WF-OCTA has significantly expanded the field of view of macular OCT-A using montage, the detected area is smaller than other UWF modalities (80% vs. 110-200%) that still represent the gold-standard in diagnostic techniques. (40,72) WF-OCT-A provided some advantages in identification of neovascularizations and non-perfusion areas in comparison to other UWF techniques. In details, NV detection rate was similar or higher (>95%) than UWFA independent of reader because of vitreoretinal interface slab, (82-86) despite contrasting evidences. (87,88) Areas of nonperfusion detection on UWF-FA co-localized with areas of nonperfusion on WF-OCTA, although the latter detected significantly greater ischemia. (89,90) Some authors demonstrated the utility of combining different UWF technologies (OCT, OCT-A, retinography), with reported superior results. (91,92) Furthermore, quantitative biomarkers of early retinal and choroidal involvement in diabetic patients have been calculated by using WF-OCT-A, including SCP VD (93) and mid-stromal VD (94,95). UWF OCT-A also provided new qualitative biomarker of peripheral retinal ischemia, including retinal venous loops. (96) A recent staging system based on WFSS-OCT-A included subclinical alterations (reduced VD) together with traditional DR vascular anomalies (MA, areas of non-capillary perfusion, venous beading, IRMA), also differentiating among active and quiescent NV. (97)

Articial intelligence (AI)