The Seeds of Financialization: Some Social and Economic Considerations from the Past

Elise M. Dermineur“As soon as the land of any country has all become private property, the landlords, like all other men, love to reap where they never sowed, and demand a rent even for its natural produce.”

AdamSmith, the Wealth of Nations

Since the crisis of 2008, there has been an academic and even a public interest in capitalism, its functioning – or rather its malfunctioning – its ethics and its future. Many since Adam Smith have attempted to define, explain and justify capitalism

In this presentation, I would like to discuss one aspect of capitalism – financial capitalism and its origins. I focus especially on the eighteenth century, a period characterized by both an intensification in financial exchange and the development of financial markets. We know that medieval and Renaissance bankers and merchants used financial instruments – and credit in particular – in order to make a profit. The Medici in Florence or the Fugger in Augsburg, to cite only but a few, could be labelled capitalists. Here, I am interested in the growing early “financialization” of the economy, that is when men and women began to change their attitudes and practices towards financial markets on a huge scale

At that time, the norms of the moral economy began to transform and subsequently changed into a more individualistic form of exchange. The anthropologist David Graeber suggests that men and women in preindustrial communities practised “everyday communism”. This concept refers to the solidarity and norms of cooperation existing among agents when it comes to the structure and organization of traditional communities before financial capitalism, from the management of common lands to neighbourly and daily mutual assistance. For Graeber, loans between private individuals obeyed rules of fairness, solidarity and

cooperation. With the emergence of capitalism, “everyday communism” disappeared to the benefit of “impersonal arithmetic”. Graeber argues that “impersonal arithmetic” was oriented towards profit making and the de-personification of exchange. It took place at some point in time, ending the reign of traditional exchange and replacing it with our modern practices.1 He does not, however, elaborate much on the conditions of this shift nor does he nuance the picture While in theory such a shift took place, it did not happen overnight. There were multiple vectors of change, often interrelated and complex. In this presentation, I would like to show, first, how solidarity, cooperation and fairness shaped early financial markets and secondly, I would like to highlight some of the critical elements that made this shift possible. My research is primarily focused on western Europe and France in particular but the results of this study could be applied elsewhere.

I. The Early Modern Credit Market: Social and Economic Characteristics

In preindustrial Europe, most financial transactions took place in inner circles and were sustained through strong norms of collaboration, fairness, and solidarity. Craig Muldrew estimates that nearly 90% of transactions in early modern England were carried out on credit.2

In France, before the proliferation of banks, the volume of mortgage debt equalled 10% of GDP in 1807.3 No doubt, viable financial markets existed long before the emergence of modern banking institutions in the nineteenth century. A chronic shortage of money as a medium of exchange made credit essential in daily transactions. The financial markets remained, however, for the most part local, hermetic and highly embedded in social systems.

1 David Graeber, Debt: The First 5,000 Years (Brooklyn, N.Y.: Melville House, 2011). Pp 14.

2 Craig Muldrew, The Economy of Obligation: The Culture of Credit and Social Relations in Early Modern England (Palgrave Macmillan, 1998).

3 Hoffman, Philip T., Gilles Postel-Vinay, and Jean-Laurent Rosenthal. “Entry, Information, and Financial Development: A Century of Competition between French Banks and Notaries.” Explorations in Economic History, 11, 2012. pp. 40 ff.

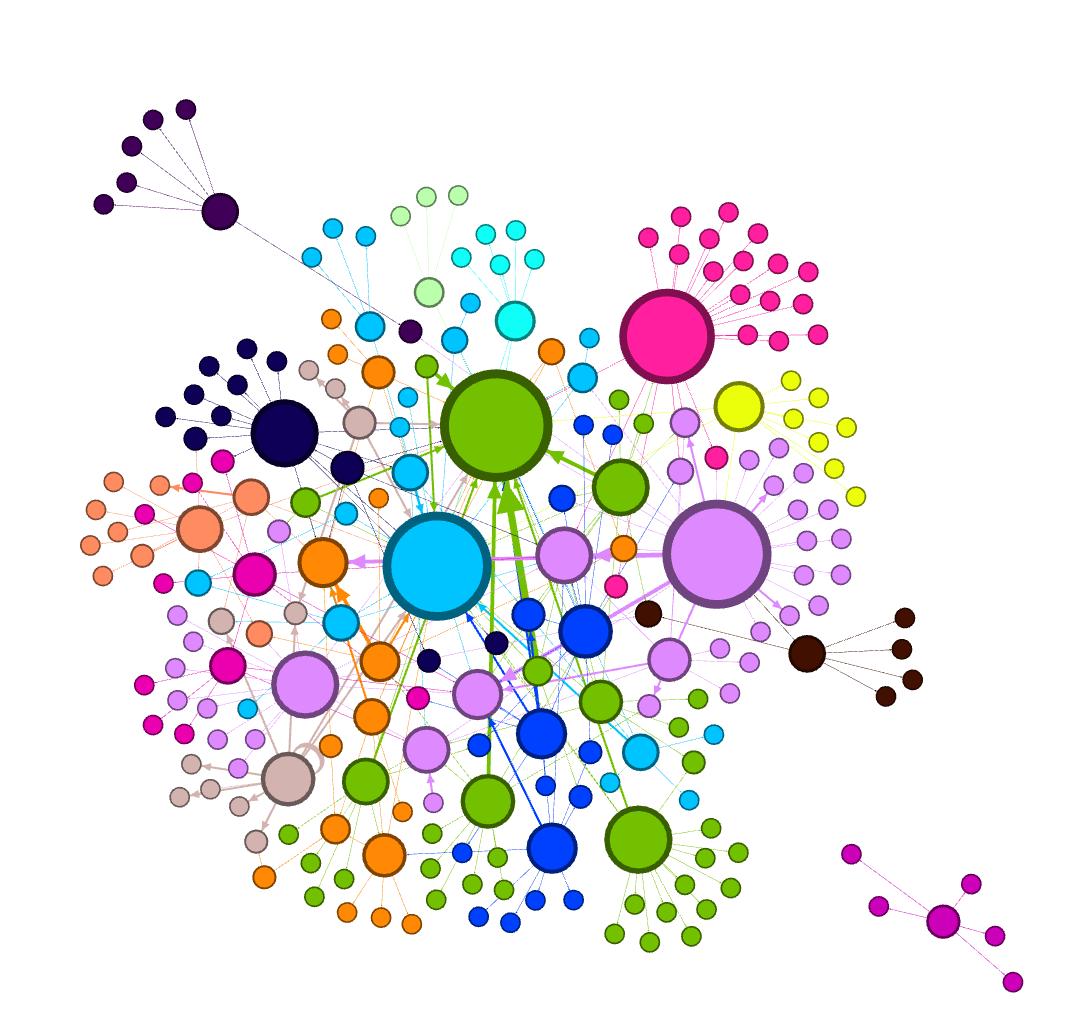

Early financial markets were characterized by exchanges that were autonomous from the State . Before the second half of the eighteenth century, most of private loan transactions took place without much institutional intercession. State institutions did provide some facilities for the conclusion of contracts (notaries in France, Spain, Italy for instance) and their enforcement (courts, in most Western regions), but regulation was otherwise largely absent. The parties to the contracts were generally members of the same community and without much disparity in their bargaining power. In fact, these credit markets were quite closed and narrow, not characterized by competitive forces and not transparent (see Figure 1). At the same time, credit relationships were embedded in a tightly-knit social context, making them subject to a social discipline – quite apart from a legal and market discipline.

Figure 1 Networks of creditors and debtors in Lepuix, 1700-1789. Each node represents one agent. Nodes are weighted according to their degree (i.e. number of connections). Based on 57 probates, 226 nodes, 326 edges.

The infrastructure for concluding and enforcing credit contracts, in early modern rural France and elsewhere in Europe, consisted of an institutionalized credit market that co-existed with an informal channel for extending credit. In the case of informal credit exchanges, many small credit transactions still elude us, either because they were not archived or because they were verbal agreements between parties.4 We can track some of these transactions (often called “contrat sous seing privés”) with the help of probate inventories. As a matter of fact, probate inventories are the only source available in Sweden with which to track early informal credit transactions. As the amounts exchanged were typically small, they did not necessarily require the official seal of the notary for the promise to be enforced. Creditor and borrower often knew each other and were bound either by family ties or by geographical or social proximity, if not all three, and often avoided the burden of registering their transaction.5 These exchanges allowed for greater negotiating flexibility regarding contractual terms, including, and especially, interest rates.6 Private parties contracting in this way could negotiate interest rates higher than the legal ceiling.7 Many of these informal loans were in fact deferred payments in a rural economy where cash was still scarce. In these contracts, guarantees could be included, but this appears to have been rare While it is difficult to assess the volume of exchange in informal credit, it is safe to assume, based on the examination of probate inventories, that

4 Ulrich Pfister calls these loans “à la main” Ulrich Pfister, “Le petit crédit rural en Suisse aux XVIe-XVIIIe siècles”. Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 49, 6 (1994), pp. 1339-1357. 1342

5 See Elise Dermineur. “Trust, Norms of Cooperation, and the Rural Credit Market in Eighteenth-Century France.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 45, no. 4 (2015): 485–506, also Jon Elster, ‘Norms’ in Peter Hedström and Peter Bearman (eds), Oxford Handbook of Analytical Sociology (OUP 2009) 197.

6 An interest rate superior to 5% was legally considered usurious. The legal cap for notarized loans was 5%, with the exception of the years 1766-1770 when it was 4%.

7 The question of interest rates is interesting. On one hand, it is certain that most contracts, either institutionalized or informal, comprised an interest. Men and women did rarely extend capital for free. Profit seeking was probably not the main concern. Instead, creditors charged an interest because of the uncertainties of reimbursement; in this sense the interest worked as a premium in the contract. On the other hand, the interest rate could not legally exceed 5% in most of the eighteenth century. Merchant capitalist ventures could easily reached a profit of 15-20% in comparison.

most small transactions used the informal channel before the second half of the eighteenth century.8

Institutionalized market (notary; agreements between private individuals)

Informal market (oral and private agreements)

Credit market

Public credit market

The notary also recorded other deeds and contracts such as probates, sales, wills, donations, and not only credit transactions. While his role was critical in guiding individuals and helping them to choose from among several credit instruments, the notary’s input should not be overestimated, especially in rural areas. In fact, individuals resorted to the notary mostly to have their deed engrossed to ensure legal validity.9 The great variety of conditions and terms of agreement to be observed in these deeds indicates that parties negotiated their contracts before arriving at the notary’s office. In large cities, notaries acted as brokers, but in small traditional communities with tight-knit social structures, credit was more of a personal and moral matter. Even with respect to such contracts, the notary did help to standardize contracts

8 Other channels of credit operated at the margins of the institutionalized credit market. Religious institutions (abbeys, convents, Mons pietatis) could extend credit and recorded the transactions in their own account books. Parish wards also extended credit. Religious institutions offered only annuities contracts, the only type of contract that was not usurious in essence. Lending and borrowing therefore existed through different channels, fulfilling different functions, meaning that the alternate circuits did not typically compete with each other.

9 Chris Briggs notes the same for medieval England. Briggs, Chris. “Introduction: Law Courts, Contracts and Rural Society in Europe, 1200–1600.” Continuity and Change 29, no. 01 (2014): 3–18.

and throughout the eighteenth century; as resort to notaries increased, we can note a tendency towards greater uniformity of contracts through assimilation and habits of practice.

In cases of dispute, the local judge summoned the parties to appear at court, assessed the validity of the contract and requested its terms be enforced. If the debtor fell short of resources and could not meet the terms of payment, the judge ordered foreclosure and an auction of the debtor’s assets. This process often proved to be quite long and costly. The judge could nominate an external party – a mediator – to help the parties reach a consensus and avoid foreclosure. In fact, many lawsuits stopped after the first hearing at court and parties preferred to resume talks and negotiations privately. We could argue that a summons to court for the first hearing was a means to publicly shame bad debtors. It acted as a tool to publicize a bad debtor.

Despite the fact that most deeds specified a short-term deadline, in practice, however, it took longer for borrowers to repay – therefore the initial length specified in the contract mattered very little. As a result, some loans were renewed either informally or formally.10 Some of these loans were not renewed before the notary, as this would have meant an additional transaction cost.11 But most were simply “rolled over”, as long as the interest was paid. Some of these loans could roll over to several generations, resulting in much indebtedness.

A further commonly observed term relates to guarantees, as expected given the delayed nature of exchange in credit contracts and the risk of loss of capital. It is worth underlining the fact that in the local credit markets examined, a good reputation as an honest person – having

10 The rise of debt litigations in the eighteenth century indicates the difficulty borrowers had in repaying their debt on time.

11 D. P. Waddilove, “Mortgages in the Early-Modern Court of Chancery” (Cambridge University, 2014).

credit – was perhaps the most important form of security for the lender. A good reputation for trustworthiness mattered a great deal and enabled the debtor not only to find credit more easily but also to put fewer guarantees on the deed.12 In small rural communities, key information about a person’s reputation was relatively easy to come by, thanks to high degree of social proximity (see Figure 1). Despite such prior acquaintance, some information regarding a borrower’s assets, capacities, reputation, and prior engagements (such as mortgaged assets with other creditors) could be missing. Moreover, repayment could also be hindered, delayed or become impossible because of unexpected conditions and external factors. Therefore, loan contracts often included guarantees, such as a specific mortgage in the form of land, livestock, real estate property such as houses, or simply in the form of a general mortgage of all the borrower’s goods (“tous ses biens meubles et immeubles”). A co-signer might also be added to the deed. In the studied sample, collateral in the form of specific plots of land dominated the guarantees offered until the middle of the eighteenth century. We can posit that the specific plots added to the deed as collateral had been negotiated and chosen by the parties beforehand and likely without the intermediation of the notary.13

In sum, before the second half of the eighteenth century, early modern credit contracts demonstrate a high degree of flexibility for the parties on at least three levels. First, parties could negotiate the terms of their agreement beforehand and could skirt around the standardized or legally-imposed interest rate limit. Secondly, parties had the possibility to

12 On reputation and the different meanings of credit see especially Haru Crowston, Clare. “Credit and the Metanarrative of Modernity”. French Historical Studies 34, no 1 (2011): 7-19.

13 Pledging a particular plot to the deed might have been a form of emotional commitment by the borrower. Historians have argued that in partible inheritance regions, peasants were not attached to specific plots but rather to the notion of possession. While this argument sounds reasonable, engaging a particular plot of land, perhaps inherited, perhaps bought, in a risky and uncertain credit transaction could have had emotional significance.

soften contractual repayment terms through tacit “rolling over”, whereby each side was satisfied with the on-going agreement. Finally, a degree of flexibility existed regarding the guarantees backing loans and the function of such guarantees. Apart from providing an alternative return, also to avoid forfeiture of their lands, borrowers could offer the payment of interest in kind.

II. The Shift and the Seeds of financialization?

a. A market in full expansion

One of the main features of local credit markets in the Old Regime resided in their dynamism. In the seventeenth and eighteenth century, credit activities intensified throughout early modern Europe. This is true for major cities like Paris, for example, but also for rural areas (Hoffman et alii, 1999, 76). Not only did the number of notarized transactions increase –especially after 1770 – but the volume of exchange also intensified. Was this increase the result of a certain economic dynamism requiring capital for entrepreneurial ventures or was it an investment strategy on the part of lenders? Or was it simply the result of a switch from informal transactions to institutionalized agreements? It is difficult to obtain clear estimations regarding the informal credit market. Probate inventories are the best source to evaluate the stocks of informal loans. Unfortunately, there is a huge discrepancy between regions regarding the number of people who actually had a probate written at their death.

The growth became visible after 1720, and more particularly in the second half of the eighteenth century. From 1750 to the French Revolution, the credit market in Paris grew by +3,75% annually in terms of volume. In the countryside around Albi, it grew by +1,86%

annually.14 In the south of Alsace, the volume of exchange was multiplied by 7,5 in 60 years. Both prices and population increased by 0,3% annually in eighteenth-century France.15

Therefore, the increase in prices cannot justify the dynamism of credit markets in the eighteenth century.16 Hoffman and his colleagues argue that notaries increasingly came to play a key role in intermediation, providing essential information and trust to investors, which thus explains this growth. This argument is certainly part of the answer. But the emergence of a new category of creditors played a critical role as well.

1730-1739 1740-1749 1750-1759 1760-1769 1770-1779 1780-1789

Volume of exchange in Paris

Volume of exchange Florimont

Volume of exchange in Delle

Figure 2 Volume of exchange in the private credit markets in Delle, Florimont and Paris

b. New investors

The expertise of notaries certainly contributed to reassuring creditors in a volatile and unpredictable market. In this context, newcomers to the credit markets appeared. In the south of Alsace, from the 1730s to the 1760s, the data show that peasants represented 65% of total

14 Postel-Vinay, Gilles. La terre et l’argent l’agriculture et le crédit en France du XVIIIe au début du XXe siècle Paris: Albin Michel, 1997. Pp134.

15 Gilles Postel-Vinay, La terre et l’argent l’agriculture et le crédit en France du XVIIIe au début du XXe siècle (Paris: Albin Michel, 1997). Pp134.

16 Philip-T. Hoffman, Gilles Postel-Vinay, and Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, Des marchés sans prix. : Une économie politique du crédit à Paris, 1660-1870 (Paris: Editions de l’Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, 2001). PP 127-128.

creditors, while in the last decade of the Old Regime they represented only 35% of creditors.17

The new investors came from an emerging rural bourgeoisie, from the liberal professions (administration related, retailers and merchants) and the growing category of seigneurial agents (judges, clerks, etc).18 In the 1730s, these together lent nearly 21,8% of the volume exchanged (with 40% by peasants), while in the last decade of the Old Regime, they lent together 50,3% of the total volume (21,8% by peasants). It is interesting to note that the local nobility lost ground and did not engage in private lending in the late eighteenth century

CREDITORS

Table 1 Creditors socio-professional categories

17 Loans registered by the notary rarely specified the occupations of debtors, largely because most of them were peasants. The rate of professions known for creditors was much higher, around 60%. See also Rosenthal, JeanLaurent. “Rural Credit Markets and Aggregate Shocks” 291

18 Among such creditors, only a handful had good information on potential borrowers, such as the seigneurial judges or agents.

The new group of investors, coming from a different socio-professional category than the peasants, had different goals, financial strategies and expectations, which did not match the traditional pattern of stability, cooperation and norms of reciprocity of the peasants. They did not have strong ties to their debtors. They did not belong to the same family, nor to the same socio-professional category, and in some cases did not even live in the same village. Hoffman has noted the same pattern in Paris where 46% of creditors and borrowers shared strong ties in the 1660s, but only 31% in the 1780s.19 In the seigneurie of Delle, the percentage of strong ties between lenders and borrowers also decreased throughout the eighteenth century. It is worth mentioning that women tended to extend credit to people in their immediate circle –neighbours and family members – consistently throughout the eighteenth century. Only women belonging to higher socio-professional groups extended loans to strangers.

19 Philip T. Hoffman and Gilles Postel-Vinay, “Information and Economic History: How the Credit Market in Old Regime Paris Forces Us to Rethink...,” American Historical Review 104, no. 1 (February 1999): 69-94. Pp83

Table 2 The Taiclet and Lacombe families’ investments throughout the eighteenth century

This new group of investors had an increasingly greater saving capacity but also fewer ties to land. Their primary aim was to make a profit, thanks to the annual return of their investment.

c. How can we explain the growing interest of the middling sort for the credit market?

Throughout early modern Europe, the tendency appeared to be the same. In most regions, not only did the credit market become increasingly dynamic, but the middling sort progressively invested their savings and capital in that market. As Hoffman suggests, the development of intermediation and the role of notaries might have reassured lenders and facilitated exchange and contact

The increasing appetite of middling investors for the credit market could also be explained by two parallel developments: the uncertainties pertaining to the land market on the one hand and the development of financial markets on the other, accompanied by a greater monetization of the economy First, demographic pressure, coupled with fragmentation of land due to partible

20 Postel-Vinay, pp 61

inheritance, increased the competition for land and boosted prices. It is possible that middling investors did not wish to compete with wealthy farmers for land. In Delle, for example, the Taiclet family did not seem to take part in the land market. In other regions, credit and investment in the land market went hand in hand as a strategy to spread risk.21 (The Taiclet family spread the risk by lending to several individuals). Secondly, bad weather and poor harvests made the land market highly unpredictable.22 The costs associated with collecting rents and dealing with payment in kind could also have been discouraging to investors. In the same vein, the transaction costs associated with the financial investment could have been less important than win the case of land – provided the chosen borrower did not default.

And what of the question of profit and interest rates? On the one hand, it is certain that most contracts in early modern Europe, either institutionalized or informal, comprised some sort of interest. Men and women rarely extended capital for free. At the time, profit seeking was probably not the main concern. Instead, creditors charged interest because of the uncertainties of reimbursement; in this sense interest worked as a premium in the contract. On the other hand, the interest rate could not legally exceed 5% over most of the eighteenth century.

Merchant capitalist ventures could easily reach a profit of 15-20% in comparison. For the middling sort with a savings capacity, a profit of 5% in addition to increasing political power within the community was not only within their reach but also desirable.

d. The emergence of new creditors in the credit market had several consequences

21 See Postel Vinay pp 61. In Gaillac, the Lacombe family invested in both the credit market and the land market.

22 There was a total of 16 significant famines in the eighteenth century in France. This number excludes the multitude of local famines here and there throughout the kingdom. 1693-1694: Grande Famine, an estimated number of 1.3 and 1.5 million French people died according to Emmanuel Leroy Ladurie. Not limited to France, the end of the 17th century was particularly deadly for starving population around the Baltic and Scotland. 1709-1710: another Grande Famine

First, there was a shift in contracting practices. Indeed, the nature of guarantees in loan contracts changed, a sign of a greater distrust on the part of creditors. In the first half of the eighteenth century borrowers usually pledged specific plots of land, subsequently they pledged their entire present and future goods without mention of any specific piece of land.23 The specific plot of land mortgaged in the loans did not necessarily match the value of the capital borrowed. It was either far superior to it (which could indicate lack of trust on the lender’s part) or inferior to the capital borrowed (which might indicate perhaps that the land was used to pay interest in kind). In fact, mortgaged assets were frequently used as a form of introducing payments in kind that could skirt around the limits imposed on the payable nominal interest or replace cash in periods of scarcity. These diverse arrangements were much more common before the 1760s, with numerous contractual variations and specificities Borrowers and lenders enjoyed apparently greater latitude of action in structuring loan transactions compared to the situation in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Additionally, a possible explanation for the drop in land mortgages includes the fact that most land may have already been mortgaged, an information deficit difficult for new investors to overcome. Further, the new creditors, not being farmers themselves, did not wish to deal with land and land would have been difficult to sell if auctioned in a difficult economic context. 24 Creditors did not wish peasants to use pledged land to pay interest in kind.25 In a further indicator of distrust, third party co-signers were also added in large numbers to deeds, so that while in the 1730s only 15% of the contracts mentioned the presence of an external guarantor, in the last decade of the century this proportion reached about 54% of the contracts signed.

23 The pledge of a specific piece of land before 1760 appears in more than 50% of the contracts, while subsequently such pledges dropped precipitously to less than 3%.

24 Before the French Revolution, there was no register for mortgages, though notaries could provide information about mortgaged land to clients if needed.

25 Holderness has shown that eviction of tenant farmers was not very common. B. A. Holderness, “Credit in a Rural Community 1600-1800” Midland History, 3 (1975): 94-116.

The increase in the resort to guarantors was not only as a source of repayment in case of default, but also for the guarantor’s role in enforcing repayment, as part of a social mechanism of incitement, cooperation and coercion among peers that could yield better results compared to external coercion.

1730-1739

1740-1749

1750-1759

External guarantor in Delle

External guarantor in Florimont

1760-1769

1770-1779

Specific land mortgaged in Delle

1780-1789

Specific land mortgaged in Florimont

Figure 3 Evolution of guarantees offered in loan contract, 1730-1789, expressed in %

Secondly, it is also notable that the number of married couples who borrowed money increased throughout the same period from 22% of the total amount in 1730-1739 to almost 50% in 1780-1789, meaning that men progressively attached their wives’ names to deeds and fewer men borrowed alone in the credit market. Married women’s holdings in the form of dowry, cash, or inherited property became a source of additional guarantee eyed by creditors.26 Moreover, repayment could be sought by turning to the widow for her share of the debt, in the case of her husband’s death, as she was legally liable for half of the loan, a much more efficient process and security than turning to several heirs.

26 See Dermineur, Elise M. “Female Peasants, Patriarchy, and the Credit Market in Eighteenth-Century France”. Proceedings of the Western Society for French History 37 (2009): 61-84.

Thirdly, with the emergence of a new group of investors, the amount of debt litigation at the local court increased, which tends to indicate not only growing indebtedness but also the impatience of new creditors. (see Table 4) (The growing percentage of debt litigation turned the judge not only into an expert but also into a defender of property rights and capital).

Table 3 Default cases at the local court in the seigneurie of Delle and Florimont, 16801785 (D: Delle, F: Florimont)

Pressing charges for repayment of a debt did not necessarily include seizing the debtor’s goods – a long process; it was also a strategy to reach the co-signer. In case of default, the legal procedure could be long and highly uncertain for investors, not least because of possible competition from other lenders, in which case the judge would have to estimate the seniority of the debt between various creditors. Expropriation per se remained exceptional and almost non-existent throughout the eighteenth century.27 Thus, the time lost and the uncertainty in recovering their capital likely discouraged creditors from accepting land mortgages. Already mortgaged, charged with annuities, uncertainty concerning land yields and harvest, high transaction costs, and fear of payment of interest in kind pushed creditors to ask for greater guarantees that would give them easier access to cash. While land remained a critical asset for peasants for production and survival, as the new category of creditors disregarded it for cash, bartering and flexible arrangements concerning the payment of interest were relegated to the

27 Gilles Postel-Vinay, La terre et l’argent l’agriculture et le crédit en France du XVIIIe au début du XXe siècle. Paris: Albin Michel, 1997. 33

background. The moral economy and contracting practices reflecting the strong norms of cooperation that were characteristic of early modern rural communities were thus challenged.

Fourthly, even in such a context, asking for justice at the local court constituted the last – and most extreme – resort available to creditors. Resort to the court notified the wider community of the existence of the dispute and, as such, the law court proceedings publicised and disseminated information, as the action to press charges and to bring the conflict into the public arena pushed the parties to expose their grievances.28 In practice, most litigation stopped after the first hearing, during which the judge recognized the validity of the lender’s claim and condemned the borrower to reimburse. But with the emergence of new investors, the social and political function of the court came into sharper relief. Claiming a debt due at court had more to do with the exercise of social and political power and not only financial reasoning. The likelihood of recovering the capital invested was often low for the creditor. However, having credit and a good reputation constituted critical business vectors, which were important to defend for both lenders and borrowers. As I have already suggested, claiming a debt at court was a form of shaming mechanism, serving an information function by altering the credit reputation of a borrower. Additionally, seizing their assets – if any were available – would often lead to the debtor’s bankruptcy.29 Litigation, then, often served another purpose in which humiliation, intimidation and honour played an important background role and through which investors asserted a form of power

28 See Daniel Lord Smail, The Consumption of Justice: Emotions, Publicity, and Legal Culture in Marseille, 1264-1423. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003).

29 Imprisonment for indebtedness had slowly regressed and was no longer the norm in the seventeenth and eighteenth century.

Finally, we cannot exclude that through credit, the middling members of society increased their social capital and their political power within their community through a network of obligés.

CONCLUSION

Traditional local credit markets, such as those in early modern France, featured norms of solidarity, fairness and cooperation and allowed its agents considerable input regarding the terms of their agreement, either before contracting and/or afterwards. But structural changes in the middle of the eighteenth century, such as an increase in credit activities, drawing on the power and profitability of such exchanges, and the appearance of new investors, affected the social and legal norms and nature of these markets. The gradual and eventually far greater resort to external parties – such as the notary and the local court – to handle and manage financial transactions remodelled these institutions into specialized and indisputable experts. Not only did their expertise gradually appear incontestable but they also helped to standardize contracts and legal norms. Private credit markets shifted from an institution in which input and flexibility prevailed to a more rigid institution in which rules and rigour applied, driven by the requirements of new investors. Here we have seen the seeds of Financialization, which bore fruit in a rigidity that still prevails today.