The Atonement In Historical Review

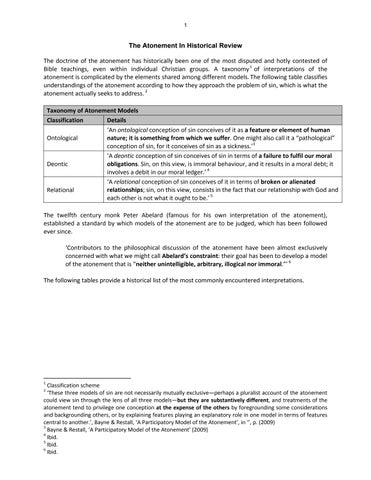

The doctrine of the atonement has historically been one of the most disputed and hotly contested of Bible teachings, even within individual Christian groups. A taxonomy 1 of interpretations of the atonement is complicated by the elements shared among different models. The following table classifies understandings of the atonement according to how they approach the problem of sin, which is what the atonement actually seeks to address. 2

Taxonomy of Atonement Models

Classification

Ontological

Deontic

Relational

Details

‘An ontological conception of sin conceives of it as a feature or element of human nature; it is something from which we suffer One might also call it a “pathological” conception of sin, for it conceives of sin as a sickness.’3

‘A deontic conception of sin conceives of sin in terms of a failure to fulfil our moral obligations Sin, on this view, is immoral behaviour, and it results in a moral debt; it involves a debit in our moral ledger.’ 4

‘A relational conception of sin conceives of it in terms of broken or alienated relationships; sin, on this view, consists in the fact that our relationship with God and each other is not what it ought to be.’ 5

The twelfth century monk Peter Abelard (famous for his own interpretation of the atonement), established a standard by which models of the atonement are to be judged, which has been followed ever since.

‘Contributors to the philosophical discussion of the atonement have been almost exclusively concerned with what we might call Abelard’s constraint: their goal has been to develop a model of the atonement that is “neither unintelligible, arbitrary, illogical nor immoral.”’ 6

The following tables provide a historical list of the most commonly encountered interpretations.

1 Classification scheme

2 ‘These three models of sin are not necessarily mutually exclusive—perhaps a pluralist account of the atonement could view sin through the lens of all three models—but they are substantively different, and treatments of the atonement tend to privilege one conception at the expense of the others by foregrounding some considerations and backgrounding others, or by explaining features playing an explanatory role in one model in terms of features central to another.’, Bayne & Restall, ‘A Participatory Model of the Atonement’, in ‘’, p. (2009)

3 Bayne & Restall, ‘A Participatory Model of the Atonement’ (2009)

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

Models of the Atonement

Model Representative (governmental, exemplary, or participatory)7

Details

Taxonomy Ontological

Originated with Clement of Rome (fl. 96),8 though commonly attributed to Peter Abelard (d. 1142), who developed it in considerable detail in his opposition to the satisfaction model of Anselm.9 For Abelard, the key element is the participation of the Christian in the life of Christ, who stands as the representative of how Christians should life. This in turn makes salvation dependent on participation in the life of Christ.10

Unlike the other models, this was founded on the concept that the purpose of the atonement was to reconcile humanity to God by changing the moral attitude of the sinner towards God, not the attitude of God towards the sinner. No penalty was inflicted, no substitution made.11 12 However, contrary to what has been claimed, Abelard’s model was not entirely ‘subjective’, as he believed a truly objective event took place as a result of the crucifixion.13

This model was adopted widely among the Socinians, Polish Brethren, Anabaptists, and other Radical Reformers. It became particularly popular among Unitarians. The eighteenth century Unitarian and scientist Joseph Priestley argued that this was the original Biblical teaching, and claimed it was present in the writings of some of the early Christian expositors.

7 These three models share considerable overlap, though the participatory contains an element unique to itself

8 ‘You see, dear friends, the kind of pattern that has been given to us For if the Lord so humbled himself, what should we do, who through him have come under the yoke of his grace?’

9 'For example, Hastings Rashdall praised Abelard lavishly for at last stating the doctrine of the Atonement "in a way which had nothing unintelligible, arbitrary, illogical, or immoral about it" ‐ precisely because Abelard was an exemplarist and eschewed such bizarre notions as penal substitution and the ransom paid to the devil.', Williams, Sin, Grace, and Redemption', p. 259

10 'Bernard believes that the Atonement was made 'once for all' on Calvary, Abelard that atonement is a process which depends on each individual and his loyalty to Christ:', Murrary, 'Abelard and St Bernard: A study in twelfth century 'modernism'', p. 87 (1967)

11 'Like Anselm, Abelard rejected any idea of Jesus' death as debt paid to God's honor. He further disliked the stress on God's judgment required in the satisfaction theory and objected to the fact that it seemed to picture a change in God's attitude toward the sinner, after he or she accepted Jesus' death on their behalf.', Weaver, 'The nonviolent atonement', p. 18 (2001)

12 'For Abelard, the problem of atonement was not how to change an offended God's mind toward the sinner, but how to bring sinful humankind to see that the God they perceived as harsh and judgmental was actually loving. Thus for Abelard, Jesus died as the demonstration of God's love. And the actual change that results from that loving death is not in God but in the subjective consciousness of the sinners, who repent and cease their rebellion against God and turn toward God.', ibid., p. 18

13 'Abelard includes multiple references to Romans 5:5‐8 and 8:35‐38, John 3:16 and 15:13, as well as 1 John 4:19. Therefore, the charge against Abelard that atonement has been reduced to an idea, or that nothing happens, really does not apply. Something does happen that changes the course of history; the love of God is revealed for Jew and Gentile in Jesus Christ This demonstration of love is an objective event. The theory is not completely reduced to the subjective response of humanity.', Schmiechen, 'Saving power: theories of atonement and forms of the church', p. 294 (2005

Models of the Atonement Model Recapitulation

Details

Taxonomy Ontological

Originated with Irenaeus (d. 202).14 15 This somewhat complicated model depended partly on the idea of Jesus as God, the earliest to do so. 16 17 However, Irenaeus also included in his interpretation an element of the moral influence model, emphasizing Christ’s life as an example, and the necessity of the Christian’s participation in the life of Christ.18

14 ‘When the Son of God was incarnate and made man, he recapitulated—or summed up—in himself the long line of the human race. In so doing he obtained salvation for us in a brief and complete way, so that what we had lost in Adam—that is, to be according to the image and likeness of God—we could recover in Jesus Christ.’

15 ‘Jesus Christ came to save all humanity through means of himself—all, I say, who through him are born again to God—infants, children, boys, young men and old. Therefore, he passed through every age, becoming an infant for infants, thus sanctifying infants; a child for children, thus, sanctifying those who are of this age (at the same time becoming an example of holiness, righteousness and submission); a young man for youths, becoming an example to young men and thus sanctifying them for the Lord. Similarly, he was an old man for old men, that he might be a perfect master for all, not merely in regard to setting forth the truth but also in regard to age, sanctifying at the same time the aged also, and becoming an example to them as well.’

16 'Some interpretations focus on the fact of God incarnating in flesh, and so on the saving effect of the life of Jesus. These approaches often coincide with the important early Christian doctrine of theōsis preserved by Eastern Orthodoxy and now being gradually rediscovered by Western theology. This is the notion, well expressed by Irenaeus, that, 'Jesus Christ became what we are in order that we might become what he himself is." This is a concept of salvation history "culminating in the deification of believing humanity." The Son came to rescue, even to re‐divinize, human nature. By coming into a human body, God had permeated human life, and this creates a potential for spiritualizing the race. This is part of Irenaeus' theory of "recapitulation" that states that Christ recapitulated human life in himself, living through, and sanctifiying, each phase of human life. Recapitulation means that the divine Son salvaged each phase of human life by his living through it. The living of this life had the effect of remaking human life itself, of restoring the potential for union with God.', Finlan, 'Problems With Atonement: the Origins of, and Controversy About, the Atonement Doctrine', pp. 120‐121 (2005)

17 'Irenaeus, stressing the Pauline parallelism between Adam and Christ, emphasized that adam was the originator of a disobedient race, and Christ inaugurated a new redeemed humanity. Central to his thinking was an idea he calls "recapitulation." He writes, "God recapitulated in Himself the ancient formation of man and woman, that He might kill sin, deprive death of its power and vivify humanity." Here the entire race is represented in Jesus. Just as all humans were somehow present in Adam, so they can be present in the second Adam.', Green & Baker, 'Recovering the Scandal of the Cross: Atonement in New Testament and Contemporary Contexts', p. 119 (2000)

18 'Although Irenaeus plugs transactional terms like ransom, propitiation, and redemption into this framework, they mainly describe the problem; they do not provide the content of the recapitulation idea. Not atonement, but restoration and re‐enabled participation in divinity are the pillars of recapitulation. Irenaeus reasons that it was necessary for God to become human and to slay sin so that it would be a human who was slaying sin, but this is just part of a controlling concept of rescue and restoration. The goal for humans is participation in the divine: as he goes on to say in that section, the only way that humanity might "participate in incorruption" is by being "united with God."', ibid., p. 121

Models of the Atonement

Model Penal substitution

Details

Taxonomy Deontic

Most commonly considered to have originated with Tertullian (d. 220). God inflicted on Christ the punishment humanity earned for sin. Christ thus bore the punishment instead of us (substitution). This view is found in various forms in the writings of many early Christian expositors,19 and Athanasius and Augustine developed it in some detail.20

This became the leading model of the atonement in Christian thought (at least in the West, and until Anselm’s satisfaction model), and was adopted by the Reformers, for whom it was the essential foundation of salvation by faith alone without the participation of human works. It remains the most popular model within Protestantism, especially among churches of the Reformed tradition.

Model Ransom/Christus Victor21

Details

Taxonomy Ontological

Originated with Origen (d. 254), though it should be noted Origen’s expositions of the atonement were not consistent, and sometimes even contained elements of participation and moral influence. According to the ransom model humanity was held under the power of the devil, until Christ offered the devil his own life and body in exchange for those he held, thus ransoming us by taking our place (substitution). Christ tricked the devil however, ransoming humanity but also taking back both his life and body. Developed further by Gregory of Nyssa, some forms of ransom argumentation are found in the writings of a number of early Christian expositors.22

Model Satisfaction

Taxonomy Deontic Details

Originated with Anselm of Canterbury (d. 1109). Anselm viewed sin against God as equivalent to the transgression of a feudal lord’s honor, which demanded ‘satisfaction’ in the form of repayment. In a form of substitution, Christ vicariously paid the price of God’s satisfaction on behalf of all humanity. 23

19 Eusebius, Hilary of Poitiers, Athanasius, Gregory of Nazianzus, Ambrose of Milan, John Chrysostom, Augustine, Cyril of Alexandria, Gelasius of Cyzicus, Gregory the Great

20 ‘It was necessary that the debt owed by everyone should be paid, and this debt owed was the death of all people. For this particular reason, Jesus Christ came among us…. He offered up his sacrifice on behalf of all people. He yielded his temple—that is, his body—to death in the place of everyone. And so it was that two wonderful things came to pass at the same time: The death of all people was accomplished in the Lord’s body, and death and corruption were completely done away with by reason of the Word that was united with it. For death was necessary, and death must be suffered on behalf of all, so that the debt owed by all might be paid.’

21 Another form of ransom model, indicating Christ’s victory over the devil

22 Irenaeus, Tertullian, John Chrysostom, Athanasius, Augustine, John of Damascus (though not as the main theme of their interpretations)

23 ‘As long as he does not repay what he has taken away, he remains in a state of guilt And it is not sufficient merely to repay what has been taken away: rather, he ought to pay back more than he took, in proportion to the insult which he has inflicted…. One should observe that when someone repays what he has unlawfully stolen, what he is under an obligation to give is not the same as what it would be possible to demand from him, were it not that he had seized the other person’s property. Therefore, everyone who sins is under an obligation to repay to God the honor which he has violently taken from him, and this is the satisfaction which every sinner is obliged to give to God.’

Historic agreement

Historically, few doctrines have enjoyed such widespread agreement within Christendom as the penal substitution view of the atonement. However, sufficient evidence exists to demonstrate that the ‘representative’ or ‘participatory’ understanding of the atonement was held from an early date, and it is to this view that modern theological scholarship is returning.

The Early Christian Era: First century to Seventh Century

Beliefs concerning the atonement in the early Christian era have been contested, due in part to the lack of systematic treatment by most writers and the ambiguity of language used by many of them. Often a particular explanation of the atonement will contain a range of different elements, some of which are used in different explanations.

For example, Ignatius described Christ’s sacrifice as an example,24 yet also included other themes in his exposition of the subject. Interpretations of the atonement as ransom, substitution, or penalty are found in the majority of the early Christian writers, such as Eusebius,25 Gregory of Nazianzus,26 Basil of Caesarea,27 Chrysostom,28 Cyril of Alexandria,29 Cyril of Jerusalem,30 Nestorius,31 Hilary of Poitiers,32 Ambrosiaster,33 Augustine,34 Leo the Great,35 and Gregory the Great.36 At this early stage the focus was still largely on representation, not substitution.37

24 ‘It serves as an example of obedience (Ign Rom. 2:2).’, Bromiley, ‘Atone; Atonement’, in Bromiley (ed.), ‘International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia’, volume 1, p. 355 (1992 ed.)

25 ‘Among other Eastern fathers, Eusebius of Caesarea stressed the vicarious aspect. Christ bore the punishment, retribution, or curse in our stead (Demonsfratio evangelica 10.1).’, ibid., p. 355

26 ‘Gregory of Nazianzus attempts a new version of the ransom understanding in which the ransom is paid to the Father rather than the devil, but he does not seem to see how this can be carried through with consistency (Oratio 45.22).’, ibid., p. 356

27 ‘Basil of Caesarea repeats the same thought in Epistula 261.2, though he can describe Christ quite definitely as an equivalent for us all (In Ps. 68.6).’, ibid., p. 356

28 ‘Chrysostom in a much fuller analysis presents the same idea: “Christ hath paid down more than we owe” (Homiliae in Rom. 10.3). He emphasizes the universal character of Christ’s death; it is equal “to the death of us all” (Hom in Hebr. 17.2). He tries to find illustrations for the transfer of liability, e.g., a king giving his son for a bandit (Hom in 2 Cor. 11.4). The injustice of Christ’s death counterbalances the justice of our own condemnation, so that freedom is secured for the guilty (Hom in Ioann. 62.2f).’, ibid., p. 356

29 ‘Cyril of Alexandria strongly holds that in Christ’s flesh an equivalent is paid “for the flesh of us all” (De recta fide 21). He describes this payment as a punishment (De incarnatione 27). In answer to the possible objection that only the man Jesus died, he replies that by virtue of the enhypostasis the one person of Jesus Christ died, so that His death has the scope and efficacy of that of the eternal Son (ch 16).’, ibid., p. 356

30 ‘Cyril of Jerusalem again alludes to the trick on the devil, but a more interesting concept is that the righteousness of Christ is more than adequate to counterbalance the sin of man: “We did not sin so much as he who laid down his life for us did righteously” (Catechesis 13.33).’, ibid., p. 356

31 ‘It is interesting that Cyril’s great rival, Nestorius of Constantinople, also spoke of Christ paying our penalty “by substitution for our death.”’, ibid., p. 356

32 ‘In Hilary the penal aspect received attention (in Ps. 53.12).’, ibid., p. 356

33 ‘Ambrosiaster also espoused the ransom view, the main point being that the unjust treatment of Christ is to be set over against our just bondage, so that the devil forfeits all claim and has to let us go (in Col. 2.15).’

34 ‘He sees not merely the payment of a debt whereby the release of justly held debtors is secured, but also the vicarious suffering of a penalty.’, ibid., p. 356

35 ‘Leo combines restoration by Christ’s incarnation with the concept of his righteousness counterbalancing our sin (Sermo 22.4).’, ibid., p. 356

36 ‘Gregory the Great uses the category of penalty: Christ suffers without guilt the penalty of our sins (Moral. xiii.30, 34).’, ibid., p. 356

37 ‘The general patristic teaching is that Christ is our representative, not our substitute; and that the effect of His

Despite this variety the earliest explicit interpretation of the atonement by a Christian writer is Clement of Rome’s exemplary/participatory view. He saw the atonement as an expression of love not anger, 38and its effect as transformative in the life of the Christian moved to participate in Christ’s example.39

sufferings, His perfect obedience, and His resurrection extends to the whole of humanity and beyond.’, ODCC

38 ‘Because of the love he had for us, Jesus Christ our Lord, in accordance with God’s will, gave his blood for us, and his flesh for our flesh, and his life for our lives.’

39 ‘You see, dear friends, the kind of pattern that has been given to us. For if the Lord so humbled himself, what should we do, who through him have come under the yoke of his grace?’

Historic Believers In Representative, Exemplary, Or Participatory Atonement

fl. 96 Clement of Rome Exemplary, participatory40 41 42 43 44

d. c. 215 Clement of Alexandria Exemplary45 46 47

d. 254 Origen48 Ransom, exemplary, participatory49 50 51 52

d. 330 Arnobius the Elder Exemplary53

40 ‘It is also a moving demonstration of love (1Clem 7:4).’, Bromiley, ‘Atone; Atonement’, in Bromiley (ed.), ‘International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia’, volume 1, p. 355 (1992 ed.)

41 ‘In the epistle of Clement of Rome to the Corinthians there are two passages, each of which strikes a single note, and strikes it most impressively. In the first the blood of Christ is the real possibility of human penitence. Human penitence — not vicarious penitence only in man's stead, but reality of penitence in man himself: this is its beauty, its joy, its preciousness, in the presence of God. It has " won for the whole world the grace of penitence."’, Moberly, ‘Atonement and Personality’, p. 236 (1907)

42 ‘In the other passage, the one thing that is absolutely clear is that the passion of Jesus Christ was all love, love beyond human conceiving, the love of God Himself. There is not a whisper here of anger, or vengeance. It is simply the unplumbed mystery of love.’, ibid., p. 326

43 ‘Here it is quite clear that Clement regards the Cross as central in the work of Atonement, and as resting upon God's love as its motive cause. And the result of this display of love is to turn us into the way of truth and righteousness, making us sons of God.’, Greensted, ‘A Short History of the doctrine of the Atonement’, p. 12 (1920)

44 'By emphasizing Christ’s work for our repentance, he underpins the moral influence theory.' , Park, 'Triune Atonement: Christ's Healing for Sinners, Victims, and the Whole Creation', p. 18 (2009)

45 ‘On the Alexandrian side Clement points out that the life of Christ equals the world in value (Quis dives salvetur? 37). Its main force, however, seems to be as an example.’, Bromiley, ‘Atone; Atonement’, in Bromiley (ed.), ‘International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia’, volume 1, p. 355 (1992 ed.)

46 ‘The concept of punishment occurs, but it is presented as educative rather than penal (i.8.70).’, ibid., p. 355

47 ‘It will be observed, that the obedience of Christ is the point here chiefly dwelt upon, and to which the victory over the evil one and our redemption is ascribed.’, Oxenham, ‘The Catholic doctrine of the atonement: an historical inquiry into its development in the Church’, p. 24 (1865)

48 Origen’s expositions of the atonement were varied, and appear not to have been completely systematic; however, although he was responsible for the ransom model, his writings also speak of the atonement as exemplary or participatory (what is important is not that Origen held to a fully articulated exemplary or participatory model, but that he preserved these elements in his exposition of the atonement)

49 ‘In most of his references to the atonement Origen repeats early patristic phrases or ideas, including propitiation (comm in Rom. 3.8) and punishment (comm in Joannem 28.19). Christ’s death also has value as an example (Contra Celsum iii.2.8), and it is as exemplary rather than imputed that the righteousness of Christ saves.’, Bromiley, ‘Atone; Atonement’, in Bromiley (ed.), ‘International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia’, volume 1, p. 355 (1992 ed.)

50 ‘The power of Christ’s death to evoke a response of love also occurs (4.10). In addition to the death of Christ and faith, works are necessary to salvation (4.11).’, ibid., p. 355

51 ‘The suffering of Christ, in which we too have mystical fellowship, is like awakening of new life in us. It is not merely a penalty, but a true chastisement. And so it is that Origen, with the piacular aspect of Atonement in his mind, can call it a purging or cleansing of our sin. The chastening of God works a real change upon our hearts, and by Christ's example we are enabled to see that this chastisement is sent by God's love, and not by His wrath, and to accept it thankfully.’, Greensted, ‘A Short History of the doctrine of the Atonement’, p. 67 (1920)

52 ‘Such language as this quite outweighs the objectionable features of the Ransom theory as stated by Origen, while at the same time avoiding the danger of over‐statement along the lines of vicarious punishment We may notice, finally, that Origen sometimes uses phrases which suggest the Moral theory:

Even apart from the value for all of His death on behalf of men. He showed men how they ought to die for righteousness' sake,’, ibid., p. 67

53 ‘Arnobius, like many others, quoted Isa. 53, but with an emphasis on the exemplary side (Inst. Divin. 4.24f).’, Bromiley, ‘Atone; Atonement’, in Bromiley (ed.), ‘International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia’, volume 1, p. 356

The Medieval Era, Middle Ages, and Modern Christian Era: Eighth century to Eighteenth Century

Various models competed for support during this time, with competition between Anselm’s satisfaction theory and Abelard’s moral influence theory being the most prominent in the twelfth century. Peter Lombard’s model is known for its incoherent attempt to reconcile competing theories, symptomatic of struggles over the doctrine during this time, 54 though he included a significant exemplary and participatory component. Anselm’s model predominated however, and became the standard interpretation from the late medieval era to the Reformation.

The concept of penal substitution became essential for Reformation theology, enabling a single legal satisfaction ‘once, for all’ which eliminated the need for intervention by Church rituals and indulgences on the one hand, and the need for human involvement in the process of salvation on the other. 55 Heavy emphasis was placed on the wrath of God, and the need for violent appeasement of His displeasure with sin. 56 As a result, penal substitution became the standard atonement paradigm for succeeding Reformation groups down to the twentieth century, 57 though unorthodox groups such as the Anabaptists and Socinians rejected it for exemplary or participatory models.58 59 60 The Catholic Church was also influenced by penal substitution. 61 (1992 ed.)

54 'Peter Lombard accumulated and tried to reconcile the most widely divergent opinions. He expresses the view that the death of Jesus was both a ransom paid to the devil and a manifestation of love.', Sabatier, 'The Doctrine of the Atonement: And Its Historical Evolution and Religion; and, Religion and Modern Culture ', p. 75 (1904)

55 ‘The Magisterial Reformers made penal expiation central and set forth the once‐for‐all, finished work of the cross as the foundation of justification by faith alone Luther preached it with unprecedented force (under the influence of Gal. 3); he taught that the satisfaction of divine justice and the propitiation of God’s wrath is the basis of our deliverance from sin, death, and the devil (Eißler 128–29). Calvin marshaled the biblical evidence (Isa. 53 as a key).’, DITB

56 ‘The Reformers introduced another view of the atonement, generally called the penal substitutionary theory In some ways, it was similar to Anselm’s satisfaction theory, but with this major difference: Instead of grounding the atonement in the honor of God—that of which God had been robbed by the sin of humanity—the Reformers grounded it in the justice of God Because he is holy, God hates sin with wrathful anger and acts against it by condemning and punishing sin. Thus, an eternal penalty must be paid for sin. Humanity could not atone for its own sin, but Christ did: as the substitute for humanity, he died as a sacrifice to pay the penalty, suffered the divine wrath against sin, and removed its condemnation forever.’, Allison, ‘History of the Doctrine of the Atonement’, Southern Baptist Journal of Theology ( 11.2.11), 2007)

57 'The penal substitutionary view has come to characterize the standard Reformed/Calvinist approach to the atonement.', Beilby, Boyd, & Eddy (eds.), ‘The Nature of the Atonement: Four Views’, p. 17 (2006)

58 ‘Although this theory became the standard view of the atonement among Protestants, it did not go unchallenged. The heretical Socinians developed a view similar in some ways to Abelard’s moral influence theory; it is called the example theory of the atonement Like Abelard’s position, it rejected the idea that God, because he is just, punishes sin by meting out judgment 72 Indeed, for Faustus Socinus, founder of the movement, justice leading to punishment, and mercy leading to forgiveness, are completely contradictory. Thus, if Jesus Christ suffered punishment to satisfy the justice of God, there can be no mercy leading to forgiveness.’, Allison, ‘History of the Doctrine of the Atonement’, Southern Baptist Journal of Theology ( 11.2.13), 2007)

59 ‘While Anabaptists stressed Christ’s example in the way of martyrdom, Luther’s and Calvin’s doctrine of atonement became the heart of the evangelical message, and its so‐called “crucicentrism,” down, for example, to John Stott.’, DITB

60 'And they insist that Christ's atonement requires following in his footsteps and conforming one's own will to the divine', Roth & Stayer, ‘A companion to Anabaptism and spiritualism, 1521‐1700’, p. 268 (2007); a comment on an Anabaptist list of articles of faith

61 ‘Until the middle of the twentieth century, Roman Catholics also commonly held penal substitution as one element in complex theologies.’, DITB

Historic Believers In Representative, Exemplary, Or Participatory Atonement Date

1080‐c.1147

d. 1142

1100‐1160

Robert Pullan62 Exemplary 63

Peter Abelard

Peter Lombard

1265‐1308 Duns Scotus

62 Also known as Pullen, Pullan or Pully

Exemplary, participatory 646566

Exemplary, participatory 67 68 69

Exemplary 70 71 72 73

63 ‘Appeal might be made to a thinker like the English theologian Robert Pullan, who rejected the ransom view and in good Abelardian fashion stressed the noetic aspect that Christ “by the greatness of the price” made known to us “the greatness of his love and of our sin” (Sent. viii.4.13).’, Bromiley, ‘Atone; Atonement’, in Bromiley (ed.), ‘International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia’, volume 1, p. 357 (1992 ed.)

64 ‘Abelard is known as the pioneer of the subjective, moral influence, view (though he did express the objective and penal one when commenting on Rom. 4:25; as quoted by Tobias Eißler 124n30).’, DITB

65 ‘Abelard, too, rejected the ransom view, but apart from some conventional references to satisfaction, he followed a very different line. The main point for him was the teaching of Christ and the response it evoked. Christ became man in order that He might enlighten the world by His wisdom and excite it to love for Himself (Ep. ad Rom., Opera [ed Cousin], II, 207). His death was both a lesson and also an example. Its intended effect was the kindling of a responsive gratitude and love which “should not be afraid to endure anything for his sake” (pp. 766f). When the sinner was stimulated to amendment of life in this way, God could remit eternal punishment in virtue of the conversion rather than any objective or external equivalent (p. 628). The work of Christ was thus a demonstration of divine love which removed the obstacle between God and man, not by a work for man, but by the effect in him.’, Bromiley, ‘Atone; Atonement’, in Bromiley (ed.), ‘International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia’, volume 1, p. 357 (1992 ed.)

66 ‘P. *Abelard, on the other hand, sought the explanation in terms of love. Christ’s atoning death was effective primarily as the final proof of a love for man which evoked a response of love in the sinner. This break with tradition, too radical to meet with much acceptance, was violently criticized by St *Bernard.’, ODCC

67 'Peter Lombard, though far from having Anselm's vision, is almost equally explicit in tracing the moral element in the sacrifice of Christ's death', Williams, 'Broadchalke Sermon‐Essays on Nature, Mediation, Atonement, Absolution, Etc', p. 254 (1867)

68 'The cross has always been proclaimed as sheer initiation, unconditional commitment, the "weakness" of compassion: and yet indissociably, at the very same moment, a formidable mimetic power of identification and transformation. As Peter Lombard, a twelfth‐century theologian, wrote:

So great a pledge of love having been given us we too are moved and kindled to love God who did such great things for us; and by this we are justified, that is, being loosened from our sins we are made just. The death of Christ therefore justifies us, inasmuch as through it charity is excited in our hearts.', Bartlett, 'Cross purposes: the violent grammar of Christian atonement', p. 221 (2001)

69 ‘But a more representative treatment is that of Lombard, who combines several aspects Thus a ransom is paid and the devil is caught as in a mousetrap (Sermo i.30.2). Yet Christ’s death is also seen from the standpoint of satisfaction or merit (Sent. iii.18.2). It exerts a moral influence too, for by it we “are moved and kindled to love God who did such great things for us” (19.1).’, Bromiley, ‘Atone; Atonement’, in Bromiley (ed.), ‘International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia’, volume 1, p. 357 (1992 ed.)

70 ‘A third general group of theories is known as the moral‐influence theory. Its roots, though not its completed form, go back to Duns Scotus (d.1308) (qv).’, Colby & Williams (eds.), ‘The New International Encyclopaedia’, volume 2, p. (1930)

71 ‘Thus Scotus did not see that Christ’s death was a punishment or that God’s justice necessarily demanded it. He could regard it as in fact a (nonsubstitutionary) satisfaction, but only because God in love freely willed to accept it as such (a doctrine known as acceptilation). Nor did it have to be infinite in scope but merely sufficient to merit initial grace for man, for which implicit faith was enough on man’s part.’, ibid., p. 357

72 ‘There is, however, no hint that Scotus accepts any sort of penal theory of the atonement here.’, Cross, ‘Duns Scotus’, p. 205 (1999)

73 ‘Already at the end of the 16th cent and the beginning of the 17th, various schools were foreshadowing things to

Historic Believers In Representative, Exemplary, Or Participatory Atonement

Date

d. 1562

Laelius Socinus

Exemplary 74 75 76 1527‐1700 Anabaptists Exemplary 77

come with their reductions. Grotius, for instance, abandoned true satisfaction for a new and juridical form of Scotus’ “acceptilation.” Since law and punishment are enactments, Grotius argued, God is not tied to them (Defensio fidei [1614], III, 60, 110). Salvation is by relaxation of the law, not satisfaction (311). This is not abrogation, for the interests of moral government must not be harmed (V). Instead, God accepts Christ’s death as a nominal equivalent, a quid pro quo (VI). This is pure mercy, but God gives and accepts a ransom in which the deliverer bears something similar to the penalty, and the evil consequences of relaxation are thus averted (VI, VIII, IX). Although Grotius denies that this is formally acceptilation, and there are obvious differences, it amounts in fact to very much the same thing.’, ibid., p. 358

74 ‘Socinianism went even further, opening the door to the fully developed subjective understanding that has dominated liberal Protestantism. Like Grotius, Socinus argued that justice is not essential It depends, as mercy also does, on God’s will (Praelectiones theologicae [1609], XVI). A doctrine of satisfaction makes the mistake of upholding justice at the expense of mercy (XVIII). In any case, substitution is impossible for Socinus, since punishment is personal. At the most, only a substitute for the penalty might be offered (XVIII). It is to be argued against penal satisfaction (a) that Christ’s death was not eternal (loccit), (b) that Christ’s obedience cannot be vicarious, since he also owed obedience (loccit), (c) that imputation by faith is self‐contradictory (De Christo Servatore [1594], IV, 3), and (d) that satisfaction destroys sanctification (loccit). Atonement is secured instead by penitence and a will to obey. The role of Christ’s death is that of an example of obedience.’, ibid., p. 358

75 ‘In reaction against the exaggerations of this ‘penal theory’ arose the doctrine, first defended by the Socinians, which denied the objective efficacy of the Cross and looked upon the death of Christ as primarily an example to His followers Notable modern exponents of this view in England were B. *Jowett and H. *Rashdall.’, ODCC

76 ‘Indeed, for Faustus Socinus, founder of the movement, justice leading to punishment, and mercy leading to forgiveness, are completely contradictory. Thus, if Jesus Christ suffered punishment to satisfy the justice of God, there can be no mercy leading to forgiveness. However, we know that God is merciful. This means that he forgives sin without demanding that his justice is satisfied. This is possible because divine justice and mercy are a matter of the will, and so God can simply choose not to exercise his justice:

There is no such justice in God that absolutely and inexorably requires that sin is punished and that God himself cannot repudiate. There is a kind of justice that we are accustomed to call by this name and that is seen only in punishment of sin. But the Scriptures by no means dignify this with the name of justice; rather, they call it wrath or anger. Thus, they are greatly in error who, deceived by the common use of the word justice, suppose that justice in this sense is a perpetual attribute of God and affirm that it is infinite 73

Because God could choose not to exercise his justice, he willed to exercise his mercy instead. Therefore, Christ did not have to offer himself as a satisfaction to God. As Socinus argued, “Why should God have willed to kill his innocent Son by a cruel and damnable death when there was no need of satisfaction? If this were the way, both the generosity of God would perish and we would invent for ourselves a God who is base and sordid.”74 Socinianism also maintained that Jesus was an unusually holy man who was equipped with the power of God, but who was not God himself. It pointed to this powerful example of virtue and integrity in the life of Jesus as the model for all humanity to follow. The crowning moment of his exemplary life was Jesus’ death, the supreme act of obedience Thus, by his life and death, Jesus provides a wonderful example that moves people to break with their sins and live holy lives: “Christ takes away sins because by heavenly promises he attracts and is strong to move all people to repentance, by which sins are destroyed. He draws all who have not lost hope to leave their sins and zealously to embrace righteousness and holiness.”75’, Allison, ‘History of the Doctrine of the Atonement’, Southern Baptist Journal of Theology ( 11.2.13), 2007

77 'Obviously not all Anabaptists would subscribe to a radical critique of sacrificial atonement, much less endorse all of the views expressed under this section. Anabaptism, like other traditions, is diverse. Yet ever since the sixteenth century, this movement has suspected Luther, Calvin, and their heirs of compromising with Catholic theology (for instance, in its juridical emphasis) and practive (Christendom). Unlike the so‐called magesterial Reformation, the Radical Reformation gave pride of place to discipleship and the imitation of Christ rather than to justification and union with Christ.', Horton, 'Lord and servant: a covenant Christology', p. 184 (2005)

Scholarly agreement

The majority interpretation of penal substitution came under sustained attack during the nineteenth century.78 The assault continued throughout the twentieth century,79 80 with the result that the theory lost considerable support among theologians over the last thirty years. While a significant number of theologians abandoning it have been liberal,81 in the twenty first century there is an increasing recognition among even conservative theologians that at the very least there is something badly wrong with traditional penal substitution,82 and that the most the original Biblical teaching is best understood as participatory.83 84 85

A particularly strongly sustained scholarly argument for participatory atonement appeared in an article written in 2007 and published in 2008.86

78 'The character of the needed reform became more and more clear : Christian thought must be brought over from the point of view of law to that of the conscience, it must be raised from legality to morality Those even who wished to adhere as far as possible to the tradition of the past, tried to find a new foundation for the doctrine of substitution in the moral fact of solidarity. They gave up justifying the expiatory condemnation of Christ on the plea that divine justice must be satisfied; they were content to insist upon the organic bond which united the Son of man with the whole race. This method of argumentation, the first sketch of which was given by Ch. Secretan, and which was powerfully developed by so many orators, among whom should be mentioned E. Bersier, Ed. de Pressense, and Ch. Bois, has the advantage of being modem; but it remains to be seen whether, from a logical point of view, the argument does not ruin the ancient edifice it was destined to support.', Sabatier, 'The Doctrine of the Atonement: And Its Historical Evolution and Religion; and, Religion and Modern Culture ', pp. 92‐93 (1904)

79 ‘But new challenges to the position arose in the modern period and were accepted by more and more churches Able apologists for the penal substitutionary view also defended and developed that position against these new theories.’, Allison, ‘History of the Doctrine of the Atonement’, Southern Baptist Journal of Theology ( 11.2.15), 2007)

80 'On much the same basis articulated by Abelard, nineteenth‐and early twentieth‐century Protestant liberals advocated a version of moral influence theory over against the satisfaction theory of fundamentalism and evangelicalism A primary example is Horace Bushnell's use of satisfaction terminology to argue for a moral influence theory of atonement.', Weaver, 'The nonviolent atonement', p. 19 (2001)

81 ‘In the wake of Socinian attacks, Protestant liberalism and Catholic modernism rejected objective theories, especially penal substitution The “heretical” anthropology of R. Girard has reinforced the trend. Radical feminists have expressed the strongest possible aversion.’, DITB

82 ‘In the twenty‐first century, the doctrine of the atonement has come under fierce attack Particularly singled out for criticism is the penal‐substitutionary theory because, according to its detractors, it privileges one (outmoded) metaphor of the atonement, it fosters passivity in the face of evil and oppression, and it even encourages child abuse. Some evangelicals, disturbed by these criticisms, have sought to revise the traditional doctrine. Many evangelicals, however, rehearse and defend the penal substitutionary model.’, Allison, ‘History of the Doctrine of the Atonement’, Southern Baptist Journal of Theology ( 11.2.16‐17), 2007)

83 ‘In the Roman Church, after the critique by Sabourin and Lyonnet and under the climate created by Teilhard de Chardin and Rahner, few scholars of note, if any, have maintained it K. Barth again proclaimed that Christ was “the Judge judged in our stead” but expressly repudiated the doctrine that he was so punished as to spare us death and to “satisfy” the demands of wrath (CD IV/1, §59/2, fine print after about 40 percent of the section). In their later writings Moltmann and Pannenberg have come closer to evangelical language. However, Moltmann denies that God’s wrath was appeased (25–26), and Pannenberg, despite strong statements of penal substitution (425–27), claims that “the reconciling death of Christ is not a payment that Christ made to God in place of others” (429; 448, against “satisfaction”).’, DITB

84 'Sanders goes so far as to argue that "the purpose of Christ's death [for Paul is ] that Christians may participate in it, not that their sins may be atoned for.".', Finlan, 'The background and content of Paul's cultic atonement metaphors', p. 117 (2004)

85 'Sanders combines the participationist passages with those that mention "dying to the law" and argues that it is not so much atonement, as it is “sharing in christ's death" that brings salvation.', ibid., p, 117

86 Restall & Bayne, ‘A Participatory Model of the Atonement’, in Nagasawa & Erik Wielenberg (eds.), ‘New Waves in

This article not only directed systematic criticism towards traditional ‘orthodox’ understandings of the atonement, it also presented a well developed participatory model. The following table summarizes the article’s criticisms of traditional interpretations of the atonement.

Model Criticism

Satisfaction

Substitution

Penal substitution

Ransom

Exemplary

Does not address the atonement from a relational point of view, and introduces a problematic characterization of God;87 88 the underlying problem of human nature is not addressed89

It is logically incoherent that God wanted a sacrifice, but substituted Himself in place of those He forgave,90 and logically incoherent that God only appeared to make a sacrifice which cost Him;91 this would mean no genuine sacrifice was involved, and that the apparent cost was in reality deceptive92

It is logically and morally incoherent that God punished God for the sins of others93

Does not address the atonement from a relational point of view, and introduces a problematic characterization of God94

Pure exemplary models fail to explain the fundamental purpose of Christ’s death, other than as an example,95 and fail to address sin ontologically96

Philosophy of Religion’, pp. 150‐166 (2008)

87 ‘The surest sign that a marriage or friendship is in trouble is when the participants start invoking their rights, or calling attention to their partner’s obligations Friends do indeed have obligations to each other, but it is not in the nature of friendship for friends to call attention to such obligations.’

88 ‘What does God’s forgiveness cost God? Does God have to struggle to overcome feelings of anger and resentment towards us? That doesn’t sound like the God of the New Testament – a God whose very essence is love and whose nature it is to always show mercy. Why can’t God simply decide to forgive us? What exactly is the price that God must pay, and to whom must it be paid? What are the consequences of the wrong that we have done to God, and how does Christ’s death and resurrection reveal them?’

89 ‘None of this is to say that talk of obligations and duties can play no role for someone who takes sin to be a primarily ontological problem. It is merely to say that such talk does not get to the heart of the problem. The signs that the sick need a doctor are the symptoms of the illness.’

90 ‘Why was the sacrifice that Christ paid to God enormously pleasing to him? If it were sacrifice alone that God desired, why must God incarnate make that sacrifice? Why couldn’t someone else make the sacrifice?’

91 ‘It is easy for God to obtain salvation, but God doesn’t want us to think that it is easy It is important for us that our salvation appears to cost God much, for otherwise we will take it for granted. Since God can not or will not deceive, God must then obtain our salvation in a costly manner.’

92 ‘one ought to wonder about a God who makes a process that is not intrinsically costly appear to be so’

93 ‘The idea that God might punish God for a debt owed to God is a strange one Is God punishing Godself? That seems pathological Is God the Father punishing God the Son? That seems sadistic.’

94 ‘Although the ransom model continues to have adherents (Taliaferro 1988) the criticisms of the model are well known and we will say little about it here.’

95 ‘Campbell captures the problem here well:

A meaningless or trivial death cannot reveal love: it reveals nothing – except perhaps foolishness. If I drive my car at high speed into a brick wall, loudly proclaiming my love for all humanity, my surviving family would probably wonder how I had left my senses, not how extraordinarily loving my gesture was (Campbell 1994: 239). The problem, in a nutshell, is that the exemplary model needs to be able to characterize Christ’s death as accomplishing something in and of itself, apart from its inspirational value.’

96 ‘The New Testament does present Christ as a model of self‐sacrificial love, but it doesn’t suggest that our primary problem is a lack of such models, nor does it suggest that we are ignorant of the costs of sin. Instead, it suggests that our sinful nature puts us at odds with each other and with God.’

The argument the article makes for participatory atonement is summarized in the following table.

A Participatory Model of the Atonement Aspect Details

Taxonomy

Efficacy

Consequence

Paul’s taxonomy of the atonement is ontological and relational, addressing both the source of sin (human nature), and its effect (a breach of human‐divine relations)97

Paul observes that the reborn believer addresses sin by participating in the life of Christ98

Paul relates the atonement directly to the formation of a participatory community in Christ99

A recent paper examining Paul’s use of the Greek word hilastērion (traditionally translated ‘propitiation’), makes the point that theologically biased interpretations of this word have resulted in inaccurate interpretations of the atonement as taught by Paul. 100 The author explains how the linguistic evidence has been misunderstood, resulting in the hilastērion being interpreted as a sacrificial victim when the word never had such a meaning.101

The most relevant linguistic evidence demonstrates that throughout the first century the word was mainly used either of the ‘mercy seat’ on the Ark of the Covenant, or as votive offerings to appease pagan gods.

‘In fact, there are only two main applications of the term ἱ゜αστήヾιο` up though the middle of the second century AD It can designate (1) the golden ‘mercy seat’ or ת〇ר‐פּーכּ on top of Israel’s ark of the covenant (LXX Pentateuch; Heb. 9:5; six times in Philo); or (2) durable votive offerings to the pagan deities, generally ἀ`αθή´ατα (cf. LSJ s.v. ἱ゜αστήヾιος II.2). (There are also minor extensions of the Pentateuchal use in the prophets: cf. Ezk. 43:14, 17, 20; Am. 9:1.)’102

97 ‘Instead, the passage portrays Paul as focused on ontological and relational matters.’

98 ‘How does participation deal with sin? According to Paul, our change of identity liberates us from sin: since we are no longer bound by (or under the sway of ) sin, we are free to participate in a restored relationship with God. In fact, Paul seems to think that we in some way participate in Christ’s relationship with God (cf. Romans 6:8–11: the Christian is “alive to God in Christ Jesus”).’

99 ‘Participatory language also infuses Paul’s conception of the Church, which he describes as the body of Christ. Paul describes the Spirit as marrying the Christian to Christ so that “the two become one flesh” (Rom. 7: 1‐4; I Cor. 6:15‐18).’

100 ‘Unfortunately, past studies of ἱλαστήριον have often allowed theological considerations to overshadow lexicography. Hence it was the doctrine of propitiation rather than the actual occurrences of the term ἱ゜αστήヾιο` in ancient sources that dominated the English‐language discussion of Romans 3:25 in the twentieth century.’, Bailey, ‘Jesus as the Mercy Seat: The Semantics and Theology of Paul’s Use of Hilasterion in Romans 3:25’, Tyndale Bulletin (51.1.155), 2000

101 ‘Additional mistakes can be made by ignoring the available linguistic evidence. Since Paul elsewhere compares Jesus to an animal victim, as for example in Romans 8:3, where the phrase ヽεヾὶ ἁ´αヾτίας is standard Septuagintal language for the Levitical ‘sin offering’ or תא―טּーח (cf. NRSV mg.), many have mistakenly concluded that similar victim language must be present in Romans 3:25. Jesus is said to be a ἱ゜αστήヾιο`; he is also said to have shed his blood Therefore, it is commonly assumed that a ἱ゜αστήヾιο` in the ancient world must have been something that could shed its blood, i.e. a sacrificial victim (‘sacrifice of atonement’, NIV; NRSV). This, too, fits the immediate context. But it is a false syllogism, since it assumes that the meaning of ἱ゜αστήヾιο` can be determined by the meaning of ‘blood’, and is moreover supported by no external evidence: ἱ゜αστήヾιο` never denotes an animal victim in any known source.’, ibid., p. 156

102 Ibid., p. 156

The latter use was common among the Greeks, but is also found in first century Jewish literature,103 where as in the Greek literature it can be understood as a gift for the purpose of appeasement. However, considerable difficulty results from applying this meaning to the use of hilastērion by Paul, since the ‘gift’ in question (Christ), is actually presented by God Himself.104

More relevant is the understanding of hilasterion as the mercy seat, an understanding which has lexical support, 105 106 and Biblical evidence.

‘By contrast, a more specialised allusion to the biblical ‘mercy seat’ (which is not a gift to the gods) does fit Paul’s context, with plenty of support from lexicography (cf. LXX Pentateuch). Paul focuses on ‘the law and the prophets’ and then more particularly on the Song of Moses in Exodus 15. The combination of God’s righteousness and redemption in Exodus 15:13 (ὡδηήγηjαな kῇ δすせαすοjύνῃ jου k摂ν そα折ν jου kοῦkον, ὃν ἐそυkとώjω) closely parallels Romans 3:24 (δすせαす折ω and ἀποそύkとωjすな).

Furthermore, Exodus 15:17 promises that the exodus would lead to a new, ideal sanctuary established by God himself. God’s open setting out of Jesus as the new ἱそαjkήとすον —the centre of the sanctuary and focus of both the revelation of God (Ex. 25:22; Lv. 16:2; Nu. 7:89) and atonement for sin (Leviticus 16)—fulfils this tradition.’ 107

103 ‘The application of ἱそαjkήとすον to Greek votive offerings was the normal or mainstream use in the first century AD While generally pagan, it is also reflected in Jewish sources such as Josephus Ant. 16.182 and 4 Maccabees 17:22 (see below).’, ibid., p, 156

104 ‘Yet no one has ever succeeded in showing how God is supposed to have presented humanity (or himself?) with a gift that people normally presented to the gods. Moreover, the mainstream use of ἱそαjkήとすον finds no parallel in ‘the law and the prophets’ to which Paul appeals (Rom. 3:21).’, ibid., p. 157

105 ‘Applying the biblical sense of ἱそαjkήとすον to Jesus in this theologically pregnant way would not have been entirely unprecedented for Paul, since Philo thought of the mercy seat as jύたβοそοち kῆな ἵそiω kοῦ しiοῦ hυちάたiωな, ‘a symbol of the gracious power of God’ (Mos 2.96; cf. Fug 100).’, ibid., p. 157

106 ‘The old objection that Paul cannot have alluded to ‘the’ well‐known ἱそαjkήとすον of the Pentateuch without using the Greek definite article is baseless, since Philo clearly uses anarthrous ἱそαjkήとすοち to refer to the mercy seat (Mos. 2.95, 97; Fug. 100).’, ibid., p. 158

107 Ibid., p. 157

Current criticism of traditional interpretations

Interest in historic alternatives to penal substitution has increased, and the interpretations of Abelard and the Socinians have received renewed attention. Significantly, support for a participatory understanding of the atonement has increased, especially in reaction to the violent nature of traditional penal substitution. 108 109 It is increasingly understood that a change was required not in God, but in those who sinned against Him.110

Likewise, the irrelevance of penal substitution to the life of the believer has been identified as a serious weakness in this theory.111 112 Even more importantly, penal substitution fails to explain the formation of the ecclesia, a body of believers who participate together other in the life, death, and resurrection of Christ.113

Significantly, modern theologians have realized that traditional readings of the atonement (typically the penal substitution model adopted by the Reformers), have historically been the cause of serious spiritual dysfunction, and even gross physical violence.

In terms of spiritual dysfunction, it has been realized that substitutionary interpretations of the atonement separate Christ’s death so completely from the believer that it has little or nothing to do with their lives. This was historically seen as an advantage by the Reformers, since it gave credence to the concept of salvation by faith alone without works, but is now seen as an artificial isolation of Christ from those he came to save which renders the atonement virtually irrelevant in the daily life of the Christian.

‘All too often the cross is treated as something of importance in relation to the initiation or inauguration of the Christian life, but that which exercises no subsequent influence over that life.’114

‘The title of this address reflects the contemporary view of the cross held by many Christians.” it is too far away, a completed transaction, a past event having little to do with our Christian identity and practice.’115

108 'According to Anthony Bartlett, the New Testament has no place for wrath and its propitiation. Thus the atonement can only be "saved" if it is stripped of its "violent" implications.', Horton, 'Lord and servant: a covenant Christology', p. 184 (2005)

109 'The most outspoken champion in this century of the "moral influence" theory has probably been Dr. Hastings Rashdall, whose 1915 Bampton Lectures were published under the title The Idea of Atonement in Christian Theology. He insisted that a choice had to be made between Anselm's objective and Abelard's subjective understandings of the atonement, and there was no question in his mind that Abelard was correct For according to Jesus, Rashdall maintained, the only condition of salvation was repentance: "the truly penitent man who confesses his sin to God receives instant forgiveness."', Stott & McGrath, 'The Cross of Christ', p. 214 (2006)

110 ‘Thus in this view, the work of the cross affects a change in us, rather than in God Horace Bushnell revived this view of the atonement in the nineteenth century. He regarded sin as a type of sickness from which we must be healed.’, Kuhns, ‘Atonement and Violence’, Quodlibet Journal (5.4), October 2003

111 ‘First, this theory emphasizes Christ’s death as a sacrifice of propitiation that turns away God’s wrath, almost to neglect of any immediate consequence of Christ’s death for the daily life of the believer.’, ibid.

112 ‘If some of the other theories are weak in not showing why Jesus had to die, this theory, as it is sometimes expounded, fails to adequately show why Jesus spent so much time teaching and calling people to follow him.’, ibid.

113 ‘The church, both universal and in each congregation, is the earthly, contemporary expression of that new race. Too often, I am afraid, this is neglected in our preaching about the atonement and what it means for us.’, ibid.

114 McGrath, ‘The Mystery of the Cross’, p. 187 (1988)

115 Marshall, ‘On A Hill Too Far Away?: Reclaiming The Cross as the Critical Interpretive Principle of the Christian

The detrimental effect this has on the spiritual life of the believer has been described in extremely blunt terms by contemporary theologians.

'The worst‐case scenario can be seen in all of the men and women who early in life made some decision to "believe in Jesus and his cross." They raised their hand at a youth rally to "accept Christ." or they walked down the aisle when the preacher gave the altar call to "get saved." Yet now they live their life no differently than the person who never made a profession of faith in the Lord Jesus.’116

The result is a life which is little different to that of the unbeliever, and is justified by the assurance of an atonement which freed the individual from any participation in the life of Christ.117 118 Theologian Dallas Willard is one of a number of theologians who have identified the doctrine of penal substitution as the direct cause of this spiritually irresponsible response to the gospel. 119 120

The doctrine of ‘eternal security’, which is dependent completely on the concept of penal substitution, has been identified as causing a spiritual malaise which results in a careless and lax attitude to actually living the life of Christ.121 122

Life’, Review and Expositor (91.2.248), 1994

116 Wakabayashi, ‘Kingdom Come: How Jesus Wants to Change the World’, p. 133 (2003)

117 ‘While there may be tinges of guilt at how their life looks right now, they hold the assurance deep in their heart that their destiny in heaven is secured. After all, they believe that Jesus died for them, and they indicated that with a raised hand, a walk down the aisle, a "sinner's prayer." Therefore, they believe that their sins are forgiven ‐ past, present, future.', ibid., p. 133

118 ‘The cross is indeed, “on a hill too far away,” irrelevant to what we may be facing now. It’s a matter of personal salvation. It has no meaning to how one lives.’, Kuhns, ‘Atonement and Violence’, Quodlibet Journal (5.4), October 2003

119 ‘He notes that if we ask the 74 percent of Americans who say they have made a commitment to Jesus Christ what the Christian gospel is, you will probably be told that Jesus died to pay for our sins that if we will only believe he did this, we will go to heaven when we die. This summarizes very well the popular understanding of the penal substitutionary theory of the atonement Incredibly, this leads many Christians to believe, “that God for some unfathomable reason, just thinks it appropriate to transfer credit from Chrsit’s merit account to ours, and to wipe out our sin debt, upon inspecting our mind and finding that we believe a particular theory of the atonement to be true‐even if we trust everything but God in all other matters that concern us.”’, ibid., p. 4

120 ‘Soelle does not criticize the substitutionary model out of a vestige of liberal theology’s optimistic view of humanity; she clearly speaks about the bondage of sin and its power in the lives of contemporary persons. Her concern, rather, is that Christ’s death interpreted as substitution so accents satisfying the demands of God’s justice (a transaction completed all at once) that the justified Christian’s new way of life is virtually ignored. She is correct in this assertion.’, Marshall, ‘On A Hill Too Far Away?: Reclaiming The Cross as the Critical Interpretive Principle of the Christian Life’, Review and Expositor (91.2.251), 1994

121 ‘By calling our doctrine “Once saved, always saved,” we have lulled many damned souls into a state of deception. The phrase is absolutely true but comes across to the average person like this: “Once saved, you can live as unholy a life as you please and still go to heaven.” That notion is untrue.’, Eliff, ‘Revival And The Unregenerate Church Member’, RAR (8.2.56), 1999

122 ‘The problem with the doctrine of “eternal security” (“once saved, always saved, no matter what you do!”) is that it is focused on our past decisions without regard for the present or the future This leads to a false assurance. In stark contrast, Paul’s understanding of perseverance is focused squarely on trusting God in the present and the future, in confirmation of, but also in disregard for the past (Php 3:12–16). Though there may be many valleys, true faith and its good works will not die, since, by definition, they are an essential part of the gift of God (Eph 2:8). Moreover, genuine assurance is based on objective evidence: upon real repentance and a growing “obedience of faith” (Eph 2:10).’, Hafemen, in ‘The SBJT Forum: What Are the Biblical and Practical Implications of the Doctrine of Assurance?’, SBJT (2.1.70), 1998)

Evangelicals themselves have realized that their specific doctrinal understanding of the atonement has had real life behavioral effects which are completely unspiritual. The doctrine of penal substitution has separated Christ significantly from those he came to save, 123 with dramatically negative effects for the life of the Christian.124 125 This is not news to our community; we have been saying this for years.

As noted previously, concern has also been expressed by modern theologians that the doctrine of penal substitution has historically justified and encouraged Christian acts of physical violence.126

‘I am especially horrified at the amount of blood that Christians have spilled in the name of God, even killing each other. Christians killing Christians under the banner of the cross of the One they confess is the Prince of Peace. Something is terribly wrong. I have wondered if part of the problem might not be in our theology of and preaching about the atonement.’ 127

'In Girard's assessment, however, Christian theology through the ages has all too often slipped back into an endorsement of sacred violence by encouraging the (re)interpretation of Jesus' death in sacrificial terms and the like.

Thus, similar to feminist and liberationalist critiques, Girard's work suggests that traditional "objective" atonement theories (see below) have contributed to the sacralization of violence within the Christian tradition (for interaction with Girard's thought, see Swartley; Vanhoozer).'128

This view has understandably met with resistance from defenders of the orthodox view, with misunderstanding of the traditional teaching being blamed for the violence which resulted.129 Scholarly support for participatory atonement, however, is both widespread and increasing.

123 ‘However, I do fear that many of the formulations of the significance of Christ’s death have not sufficiently involved those for whom Christ died.’, Marshall, ‘On A Hill Too Far Away?: Reclaiming The Cross as the Critical Interpretive Principle of the Christian Life’, Review and Expositor (91.2.251), 1994

124 ‘In a different direction, contemporary theologians have suggested that some views of atonement scandalize unnecessarily; in particular, that certain forms of the substitutionary view of atonement have contributed to ethical passivity.’, ibid., p. 250

125 ‘Further, in following this tradition that goes back to the Reformation, one is tempted to believe all suffering has already been obtained in Christ; it is finished. “Jesus Paid It All!” Such a view, Soelle maintains, leads to a “suffering‐free” religion with little ethical sensitivity.’, ibid., p. 251

126 'In short: its critics charge the penal substitution view with surreptitiously legitimating violence in the name of justice.', Vanhoover, ‘The drama of doctrine: a canonical‐linguistic approach to Christian theology’, p. 382 (2005); Vanhoover argues against this view

127 Kuhns, ‘Atonement and Violence’, Quodlibet Journal (5.4), October 2003

128 Eddy & Beilby, ‘Atonement’, in Dymess, Kärkkäinen & Martinez (eds.), ‘Global Dictionary of Theology: A Resource for the Worldwide Church’, p. 85 (2008)

129 'In attempting to relate orthodoxy to the modern situation and the challenge of liberationist theologies, some authors question the connection that is made between orthodoxy and violence. Richard Mou studies Reformist Theology from this perspective, and concludes that, while there is much violence in Reformist/Calvinist history, it cannot be explained with reference to a Reformed doctrine of atonement if properly understood (2003:164).', Bergen, 'Reading ritual: Leviticus in postmodern culture', p. 103 (2005)

Scholarly Support for Participatory Atonement

Date Quotation

1994 ‘The central thesis of this lecture now comes into view. I contend that the work of the cross is not completed until we participate in it.’130

‘Paul’s understanding of the Christian’s participation in the cross of Christ is foundational.’ 131

‘Christ’s love, according to Kenneth Grayston, “is his action in dying not chiefly as a martyr—not solely as our representative—but as our forerunner, to show the way that all must go.”42 In other words, the death and resurrection of Christ “are saving events insofar as Christians participate in them.”43’ 132

2001 'Reno says that, in this account, Milbank accords the activity of "interpretive creativity" an indispensable role in the act of atonement itself, which thereby gives rise to the idea of "participatory atonement."'133

2003 ‘Let me adapt a statement from Marshall: atonement as exclusively God’s work, precluding human participation, is an over simplification. Atonement as the gracious act of God, for sin and thereby doing for us what we cannot do for ourselves, must be joined by that which only we can do.’ 134

‘These verses highlight that our salvation involves coordinated effort between God and us.’ 135

2004 'For example, Hastings Rashdall praised Abelard lavishly for at last stating the doctrine of the Atonement "in a way which had nothing unintelligible, arbitrary, illogical, or immoral about it" ‐ precisely because Abelard was an exemplarist and eschewed such bizarre notions as penal substitution and the ransom paid to the devil.'136

2004 ‘Participation is a constant theme with Paul. The believer must offer up his whole self as a living sacrifice (Rom 12:1; 6:13)…’137

2005 'Abelard includes multiple references to Romans 5:5‐8 and 8:35‐38, John 3:16 and 15:13, as well as 1 John 4:19. Therefore, the charge against Abelard that atonement has been reduced to an idea, or that nothing happens, really does not apply Something does happen that changes the course of history; the love of God is revealed for Jew and Gentile in Jesus Christ This demonstration of love is an objective event. The theory is not completely reduced to the subjective response of humanity.'138

130 Marshall, ‘On A Hill Too Far Away?: Reclaiming The Cross as the Critical Interpretive Principle of the Christian Life’, Review and Expositor (91.2.251), 1994

131 Ibid., p. 252

132 Ibid., p. 252

133 Hyman, 'The Predicament of Postmodern Theology: Radical Orthodoxy or Nihilist Textualism?', p. 87 (2001)

134 Kuhns, ‘Atonement and Violence’, Quodlibet Journal (5.4), October 2003

135 Ibid.

136 Williams, Sin, grace, and redemption', in Brower & Guilfoy (eds.), 'The Cambridge companion to Abelard', p. 259 (2004)

137 Finlan, ‘The background and content of Paul's cultic atonement metaphors’, p. 118 (2004)

138 Schmiechen, 'Saving power: theories of atonement and forms of the church', p. 294 (2005)

Scholarly Support for Participatory Atonement

Date Quotation

2005 'Abelard paid attention to certain aspects of salvation that had been neglected for centuries He saw that real forgiveness had to mean "making the sinner better," but objective theories of atonement did not suggest that the sinner is saved at all Abelard put the emphasis back on the whole of Christ's life, not just its tragic end.'139

'Both Luther and Calvin present a dramatic and frightening scenario of divine violence restrained by divine mercy, but a mercy that had to be mediated through violence.'140

2006 ‘Paul had no thought of conversion to Christ somehow independent of the cross. Participation in Christ always included participation in his death.’141

‘For the moment, however, we may observe one corollary. That is, the inadequacy of the word “substitution” to describe what Paul was teaching in all this. Despite its much favoured pedigree, “substitution” tells only half the story. There is, of course, an important element of Jesus taking the place of others – that, after all, is at the heart of the sacrificial metaphor.

But Paul's teaching is not that Christ dies "in the place of" others so that they escape death (as the logic of "substitution" implies).86 It is rather that Christ's sharing their death makes it possible for them to share his death.

“Representation” is not an adequate single‐word description, nor particularly “participation” or “participatory event”. But at least they help convey the sense of a continuing identification with Christ in, through, and beyond his death, which, as we shall see, is fundamental to Paul’s soteriology.’ 142

2009 '…emphasis upon the practice of accepting forgiveness and extending it to one another, a participatory atonement if you will.'143

2009 'Participatory atonement: we become reconciled to God by participating in Jesus' path of death and resurrection' 144

'Rather than substitutionary atonement, Mark speaks of participatory atonement. We are called not simply to believe that Jesus has done it for us, but to participate in his passion. That is the way of becoming "at one" with God.'145

2009 'And (from the vantage point of the mystery itself), the character of the God/world relationship is understood to be participatory, not transactional. If God does it all, we do nothing If we do something, God's sovereign power is compromised.

In a participatory model, but contrast, God does it all and we are fully included in the doing of God. And not as puppets are we fully included, but as creatures created by the Creator God to be creative. It is we who contribute something, we who are artists participating in the artistry of God.'146

139 Finlan, 'Problems With Atonement: the Origins of, and Controversy About, the Atonement Doctrine', pp. 74‐75 (2005)

140 Ibid., pp. 75‐76

141 Dunn, ‘The Theology of Paul the Apostle’, p. 410 (2006)

142 Ibid., p. 223

143 Steere, 'Rediscovering Confession: A Constructive Practice of Forgiveness' p. 227 (2009)

144 Borg, 'Conversations with Scripture: The Gospel of Mark', p. 81 (2009)

145 Ibid., p. 81

146 Rigby, '"Beautiful Playing": Motlmann, Barth, and the Work of the Christian', in McCormack & Bender (eds.), 'Theology as Conversation: The Significance of Dialogue in Historical and Contemporary Theology: A Festschrift for

Scholarly Support for Participatory Atonement

Date Quotation

2009 'Could Abelard, who rejected crusading and the compensatory understanding of Christ's death, guide us today to such a nonviolent theory of atonement?'147

'…the Abelardian model contains truths effective in guiding us today to a nonviolent theory of atonement.'148

Traditional theologians view with alarm the changing understanding of the atonement within evangelical thought, with its rejection of penal substitution and an emphasis on participation,149 and rightly identify it as the renewal of a historical interpretation rather than a complete novelty,150 an interpretation recognized to date at least as early as Abelard.151 Though much has been written by traditionalists in response, at present a coherent defense of the traditional doctrine is still lacking.152

Daniel L. Migliore', p. 114 (2009)

147 Love, 'In Search of a Non‐Violent Atonement Theory: Are Abelard and Girard a Help, or a Problem?', in ibid., p. 197

148 Ibid., p. 197

149 ‘Above all, the new‐model god never demands any payment for sin as a condition of forgiveness According to the new‐model view, if Christ suffered for our sins, it was only in the sense that he “absorb[ed] our sin and its consequences”—certainly not that He received any divinely‐inflicted punishment on our behalf at the cross. He merely became a partaker with us in the human problem of pain and suffering.’, MacArthur, ‘Open Theism’s Attack On The Atonement’, Masters Seminary Journal (12.1.5), 2000

150 ‘In fact, the “new‐model”“ innovations described in Robert Brow’s 1990 article—and the distinctive principles of open theism, including the open theist’s view of the atonement—are by no means a “new model.” They all smack of Socinianism, a heresy that flourished in the 16th century.’, ibid., p. 7

151 ‘A close contemporary of Anselm, Peter Abelard, responded with a view of the atonement that is virtually the same as the view held by some of the leading modern open theists According to Abelard, God’s justice is subjugated to His love. He demands no payment for sin. Instead, the redeeming value of Christ’s death consisted in the power of the loving example He left for sinners to follow. This view is sometimes called the moral influence theory of the atonement. Abelard’s view was later adopted and refined by the Socinians in the 16th century (as discussed above).’, ibid., p. 10

152 ‘As a very general first point, it is possible to say that there is no consensus on how to preserve satisfaction atonement. And further, the diverse and mutually contradictory strategies might indicate that the preeiminent concern of these writers is more to defend satisfaction by any means available than to ask whether satisfaction atonement truly reflects biblical understandings of the life and work of Christ.', Weaver, 'The nonviolent atonement', p. 195 (2001)