Religious Research Association, Inc.

Rethinking the Reasonableness of the Religious Right

Author(s): Clyde Wilcox, Ted G. Jelen and Sharon Linzey

Source: ReviewofReligiousResearch, Vol. 36, No. 3 (Mar., 1995), pp. 263-276

Published by: Religious Research Association, Inc.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3511534

Accessed: 27-04-2016 09:10 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

ReligiousResearchAssociation,Inc.,Springerare collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access toReviewofReligiousResearch

RETHINKING THE REASONABLENESS OF THE RELIGIOUS RIGHT

Clyde Wilcox

Georgetown University

Ted G. Jelen

Illinois Benedictine College

Sharon Linzey

Seattle Pacific University

Review of Religious Research, Vol. 36, No. 3 (March, 1995)

Using a sample of members of Moral Majority, we compare two general explanations of activism within the organization: "pathological" theories, which posit a connection between personal deficiencies and conservative political activism, and "representational" theories, in which supporters of right-wing organizations are thought to be motivated primarily by unrepresented policy preferences. We find much stronger support for the representational view and offer several possible explanations for this finding.

The resurgence of religiously-motivated political activity which characterized the decade of the 1980s raised a number of important normative questions. Indeed, the reassertion of religious values in the political arena was accompanied by arguments that fervent religious belief is something of a dangerous stranger to democratic politics. Religious values are thought by some to be private and nonnegotiable, and therefore inappropriate in the public sphere of politics (see Greenawalt, 1988, for an account of permissible and impermissible uses of religion in politics). Strong religious beliefs are thought to be associated with, and perhaps causally related to, personality disorders incompatible with democratic civility. For example, a recent work on the politics of abortion has suggested that there exists an intimate connection between Christian fundamentalism and a propensity to commit violent acts (Blanchard and Prewitt, 1993).

In this study our purpose is twofold. We examine the attitudes and beliefs of members of a religiously distinctive political organization to address the following questions: First, do such organizations include members with psychologically or socially pathological characteristics? Second, are such characteristics associated with level of political activity within the organization? Are the most "maladjusted" members the most active, or is participation somehow related to more "civil" attitudes and behaviors?

When the Christian Right of the 1950s crusaded against communism, scholars were quick to posit pathological theories to explain support for these organizations. Those who supported the Christian Right were variously accused of being authoritarian, dogmatic, alienated, anxious about their social status, moti-

vated by feelings of inadequacy, of projecting their self-hatred outward, and of being motivated by other non-political factors (see, for example, the essays in Bell, 1963). In part, this emphasis on social and psychological strain as explanations of support for the Right may have been a function of the ideology of some of the groups of the secular right. For example, members of the John Birch Society held that recent American history, and indeed most world history in the past few centuries, had been dominated by the Illuminati.

When the Moral Majority, Christian Voice, and Religious Roundtable were formed in the late 1970s, and when Marion (Pat) Robertson ran for president in 1988, scholars took a somewhat different view. Although some have argued that support for the Christian Right was fueled by hatred for outgroups (Jelen, 1991), most scholars focused their explanations on political beliefs and religious doctrine (Wilcox, 1991; Green and Guth, 1988; Johnson, Tamney and Burton, 1989; Sigelman, Wilcox and Buell, 1987). Support for the Christian Right was seen as reasonable in two distinct senses; it was not attributable to personality disorders, and it represented support for political organizations that sought to enact the political agenda of their supporters. In this respect, support for organizations of the Christian Right was not considered to be substantially different from support for other political organizations. Recent explanations of Christian Right support have emphasized the apparent representativenss of such organizations, rather than attributing pathological characteristics to their supporters, and several analysts have strongly suggested that it is policy preferences, rather than personal inadequacies, that account for religiously-motivated political activity generally (Simpson, 1983; 1985b, Page and Clelland, 1978). While there have been methodological disputes over specific operationalizations of Christian Right support (Sigelman and Presser, 1988; Simpson, 1988), there is little dispute about the issue basis of religiously conservative political activity (Sigelman, Wilcox, and Buell, 1987).

The question of whether organizations on the "extreme" political right are to be considered manifestations in individual or social maladies, or whether such organizations are relatively benign interests groups which represent previously unrepresented preferences, is thus an intriguing one, with no obvious answer. Scholars interested in the sociology of knowledge might be tempted to speculate that the appeal of pathological explanations for "right-wing extremism" has faded as memories of the Third Reich have receded, or that pejorative characterizations of constitutionally-protected beliefs and values have become less intellectually respectable. To paraphrase E. E. Schattschneider, we are less willing to "flunk" large groups of the American population. Nevertheless, the relative importance of pathological and representational sources of support for the Christian Right, or for any organization, is ultimately an empirical question, which we address in this study.

THEORETICAL CONCERNS

Several pathological explanations for support for the Christian Right were advanced by scholars in the 1950s and later. First, some scholars argued that support for the religious right resulted from personality disorders. Support for

the right was said be occasioned by authoritarianism, dogmatism, cognitive rigidity, strongmindedness, or projection of personal inadequacies onto political outgroups (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Stanford, 1950; Rohter, 1969; Elms, 1969; Chesler and Schmuck, 1969; McEvoy, 1971).

Second, support for the Right has frequently been explained as a function of alienation. This variant on the broad concept of alienation held that mass society had created many rootless citizens with few attachments to society. These citizens were easily recruited by right-wing groups, who offered belonging, friendship, and security (Rohter, 1969; Conover and Gray, 1981; Abcarian and Stanach, 1965). Membership in a right-wing group allowed previously alienated individuals to feel more worthwhile and more valuable.

Third, support for the Right has been frequently linked to social status strain. In periods when some social groups rapidly advance in social status while others decline, status anxiety may occur. Even in more stable times, those citizens with discrepant social status locators may experience anxiety, for they perceive their status as a function of their highest locator, while at least some others view them in terms of their lowest locator. Thus those who are anxious about their social status seek to support right-wing organizations, who offer populist attacks on the status structure while legitimating the hoarding of personal wealth (Lipset and Raab, 1981; Trow, 1959; Rush, 1967; McEvoy, 1971; Rohter, 1969).

The general hypothesis that support for Christian Right organizations is occasioned by individual pathologies has not fared particularly well when faced with empirical tests. Wilcox (1989) found that pathological explanations of support for the Christian Right were generally not supported among a mass sample, and that policy preferences were much stronger predictors of such support. Similarly, several studies (Conover, 1983; Wood and Hughes, 1984; Simpson, 1985a) have failed to discern an empirical connection between status discontent and support for socially conservative positions and movements, although Wald, Owen, and Hill (1989a) have suggested that the status discontent variable performs much better when measured subjectively (do people feel as if their status has been undervalued) than when measured with "objective" demographic measures.

Finally, there has been little evidence that support for right-wing movements is directly linked to authoritarianism. Wald, Owen, and Hill (1989b) have shown that support for the right has been linked to values that involve deference to (especially religious) authority (see also Bruce, 1988). The concept of "authority-mindedness," as developed by Wald and colleagues, is subtly but importantly different from authoritarianism. Although authoritarianism implies a personality drive to behave in an "aggressive, domineering, and destructive way toward people" (1989b:94), authority mindedness is a ideological commitment to the value of obedience. In this latter formulation, fundamentalists might support the Moral Majority because their religious leaders asked them to, but there would be limits to their obedience to religious authority. While the measures of authoritarianism (such as the different variants of the F-scale) typically emphasize relations between people, Wald, Owen, and Hill's concept of authority-mindedness involves relations between individual people and a presumed inerrant source of authority (in the case of doctrinally conservative Protestants, the Bible). The commitment to obedience in this latter formulation is normative and ideological, rather than being driven by personality characteristics (indeed,

authority-mindedness, in contrast to authoritarianism, is likely to be domainspecific). When the effects of authority-mindedness on support for the Christian Right are compared with those of authoritarianism, the former variable is a much stronger predictor of Christian Right support. Bruce (1988) posits a similar concept, but locates it within a certain cognitive style. In Wald's et.al. formulation, authority-mindedness is an ideological commitment, rather than a pathological personality disorder.

Thus, recent empirical studies have cast doubt on the empirical link between pathological psychological characteristics and support for "extremist" right-wing organizations. However, such studies have suffered from data limitations beyond the control of the authors. The work of Wilcox (1989) is based on national sample surveys, and few if any are actual members, while Wald, Owen, and Hill rely on a sample of church members from a southern community. Since much research has suggested that support for the Christian Right has never been particularly widespread among the general population, nor among doctrinally conservative Christians (Buell and Sigelman, 1985, 1987; Wilcox, 1987; Sigelman, Wilcox, and Buell, 1987; Jelen, 1993), it may be that studies based on large samples of general populations underestimate the effects of personality characteristics on Christian Right support. That is, it is possible that people indicating "support" for organizations such as Moral Majority on a survey instrument may not evince personality disorders, but that activist members of such organizations (who would be difficult to identify in large probability samples) might possess such personality traits. Indeed, Page and Clelland (1978: 96) speculate that the correlates of activism in religiously conservative organizations and movements might be quite different from the variables which occasion verbal support for such activity. Passive "support" is certainly conceptually distinguishable from active membership or participation, and little research has been done in recent years to identify the characteristics of such activists. Our purpose in this study is to compare the effects of pathological personality traits and policy preferences on activism in the most well-know Christian Right organization of the 1980s: Moral Majority.

THE DATA

Our data come from a mail survey of the members of the Indiana Moral Majority conducted in 1983 and a smaller survey of members of the Arkansas Moral Majority. Random samples were drawn from a list of lay donors and clergy. The response rate for the survey was 48%, providing us with 162 surveys from Indiana: 116 members and 46 clergy. The Arkansas survey was a pre-test for the survey instrument and was drawn from a purposive sample. It yielded 25 respondents.' We have combined these two samples, although in every analysis below we have looked for significant differences between respondents in each state (Georgianna, 1989).

The sample on which this study is based thus deviates from the normal canons of probability sampling in a number of respects. Our respondents are drawn entirely from the membership of Moral Majority, and from two relatively rural states. However, given the nature of our research question, the unrepresentativeness of our sample may represent something of a strength. More systemat-

ic samples of larger populations have revealed scant empirical relationships between pathological characteristics and Christian Right support. By contrast, our sample represents a small group of highly committed actual members of Moral Majority. We thus regard our research as a very stringent test of the pathology-support hypothesis. If any connection at all exists between these two variables, we should discern it here.

The questionnaire contained a number of items that are useful in assessing some of these pathological explanations for activism in the Moral Majority, and others to examine theological and political sources of activism. The question wording and scale construction are detailed in the Appendix. Since our sample consists entirely of Moral Majority members, our dependent variable is the level of activism in the Moral Majority. Of course, these data cannot be used to determine whether these factors influenced membership in Moral Majority, since we have no comparable data for the general population. We can, however, estimate the level of authoritarianism, status anxiety, and other sources of strain in the Moral Majority membership. In the end, we will use these data to predict activism in the Moral Majority, and offer some thoughts on the strengths of "pathological" and "representational" accounts of the Religious Right.

FINDINGS

Pathological Sources ofActivism in the Moral Majority

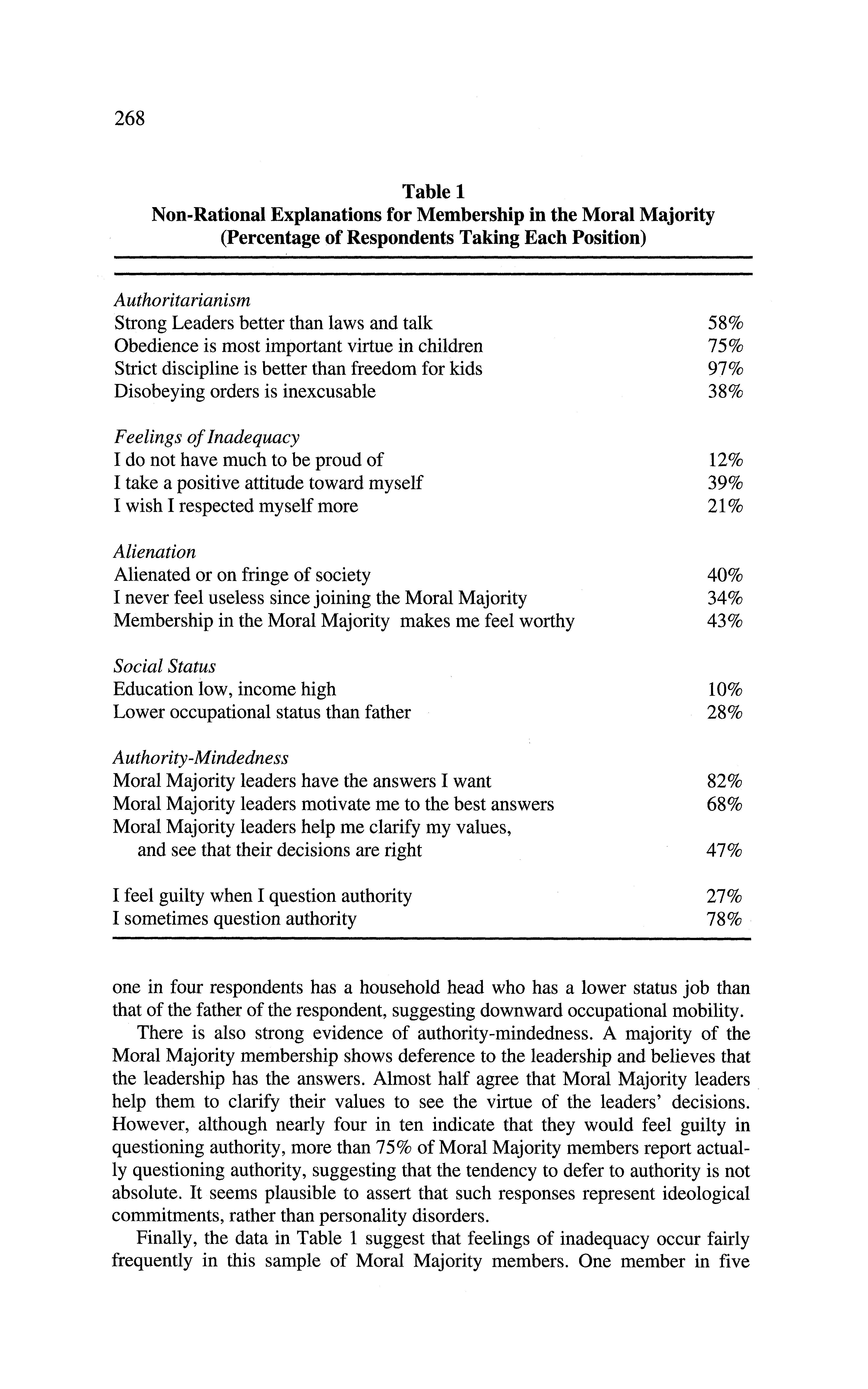

In Table 1, we show the percentage of respondents who took positions consistent with the various pathological explanations for support for the Christian Right. There is strong evidence of authoritarianism among Moral Majority members, with a majority believing in the value of strong leaders rather than laws, nearly one in four agreeing that disobeying orders is inexcusable, and a majority believing in strict discipline for children. Beliefs about parental discipline are important components of fundamentalist religious doctrine (usually traced to a passage in Proverbs 23:13 about sparing the rod and spoiling children), so that belief in strict discipline for children is not necessarily a sign of an authoritarian personality. Yet the other two items yield some evidence that members of the Moral Majority were somewhat authoritarian.

There is also evidence of alienation among Moral Majority members. Fully 40% said that they felt alienated from or on the fringe of society. Several others indicated that their membership in the Moral Majority helped them feel more useful and worthy. A substantial portion of members were not active in other organizations (not shown), suggesting marginal ties to other social institutions. For these respondents, membership in Moral Majority is an exception to a general pattern of social isolation.

There is some evidence of social status concerns as well. Although we have no measures of status anxiety, we identified those respondents who were a standard deviation above the mean on income and a standard deviation below the mean on education. This particular pair of discrepant status locators is one that has been most frequently posited to lead to support for the Right.2 Only one in ten Moral Majority members are status inconsistent in this way. However, more than

Table 1

Non-Rational Explanations for Membership in the Moral Majority (Percentage of Respondents Taking Each Position)

Authoritarianism

Strong Leaders better than laws and talk 58%

Obedience is most important virtue in children 75%

Strict discipline is better than freedom for kids 97%

Disobeying orders is inexcusable 38%

Feelings of Inadequacy

Alienation

Alienated or on fringe of society

Social Status

Authority-Mindedness

Moral Majority leaders have the answers I want 82%

Moral Majority leaders motivate me to the best answers 68%

Moral Majority leaders help me clarify my values, and see that their decisions are right 47%

I feel guilty when I question authority

I sometimes question authority

one in four respondents has a household head who has a lower status job than that of the father of the respondent, suggesting downward occupational mobility. There is also strong evidence of authority-mindedness. A majority of the Moral Majority membership shows deference to the leadership and believes that the leadership has the answers. Almost half agree that Moral Majority leaders help them to clarify their values to see the virtue of the leaders' decisions. However, although nearly four in ten indicate that they would feel guilty in questioning authority, more than 75% of Moral Majority members report actually questioning authority, suggesting that the tendency to defer to authority is not absolute. It seems plausible to assert that such responses represent ideological commitments, rather than personality disorders.

Finally, the data in Table 1 suggest that feelings of inadequacy occur fairly frequently in this sample of Moral Majority members. One member in five

reports wishing that she/he had more self-respect, while one in ten agreed with the stronger statement that "I do not have much to be proud of." Further, only 40% of members reports having a positive attitude toward oneself. While only minorities agree with the first two statements, it is perhaps noteworthy that a majority do not report having positive self-images. Although we have no means of determining whether these marginal distributions are unusual (relative to the general population), our results do suggest that such feelings of inadequacy are not uncommon in the membership of Moral Majority.

While it is not clear how distinctive Moral Majority members are from the American population at large, it seems clear that such "pathological" characteristics are well represented among our sample. While we are unable to provide a comparison with other populations, the marginal distributions of these variables suggest the possibility that, to some extent, affiliation with Moral Majority may have been occasioned by the personal deficiencies of potential members

Representational Explanations for Moral Majority Participation

The data in Table 1 suggest that a sizable minority of members in the Indiana and Arkansas Moral Majority chapters may have been motivated by personality characteristics, alienation, social status concerns, or cognitive style. Of course, many of those who show personality characteristics or cognitive styles that fit the various pathological explanations of Moral Majority membership may ultimately support the organization for other, non-pathological reasons. In particular, they may support the Moral Majority because the organization espouses their religious doctrinal views or their political positions. Moral Majority affiliation may indeed supplement more conventional channels of political representation.

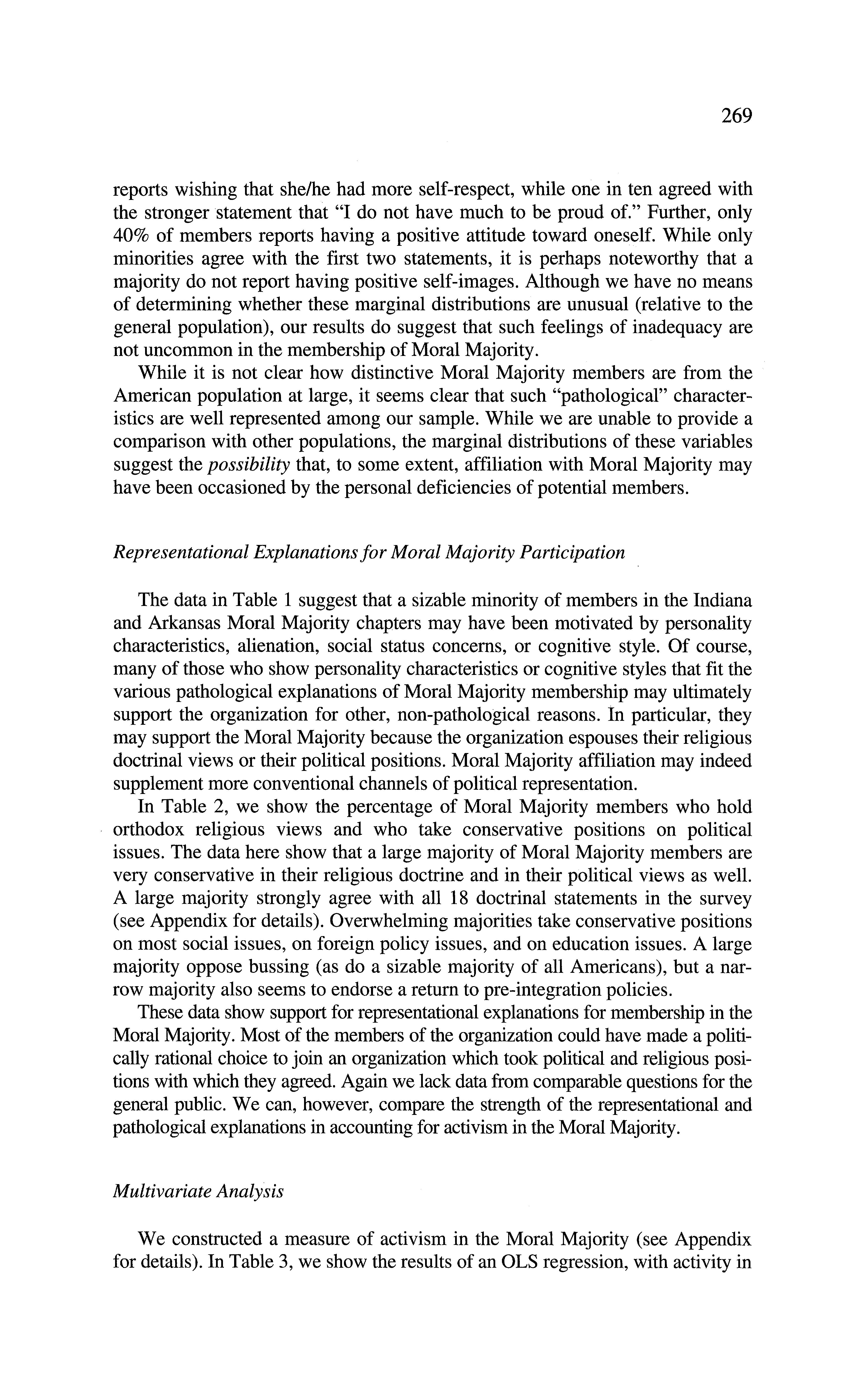

In Table 2, we show the percentage of Moral Majority members who hold orthodox religious views and who take conservative positions on political issues. The data here show that a large majority of Moral Majority members are very conservative in their religious doctrine and in their political views as well. A large majority strongly agree with all 18 doctrinal statements in the survey (see Appendix for details). Overwhelming majorities take conservative positions on most social issues, on foreign policy issues, and on education issues. A large majority oppose bussing (as do a sizable majority of all Americans), but a narrow majority also seems to endorse a return to pre-integration policies.

These data show support for representational explanations for membership in the Moral Majority. Most of the members of the organization could have made a politically rational choice to join an organization which took political and religious positions with which they agreed. Again we lack data from comparable questions for the general public. We can, however, compare the strength of the representational and pathological explanations in accounting for activism in the Moral Majority.

Multivariate Analysis

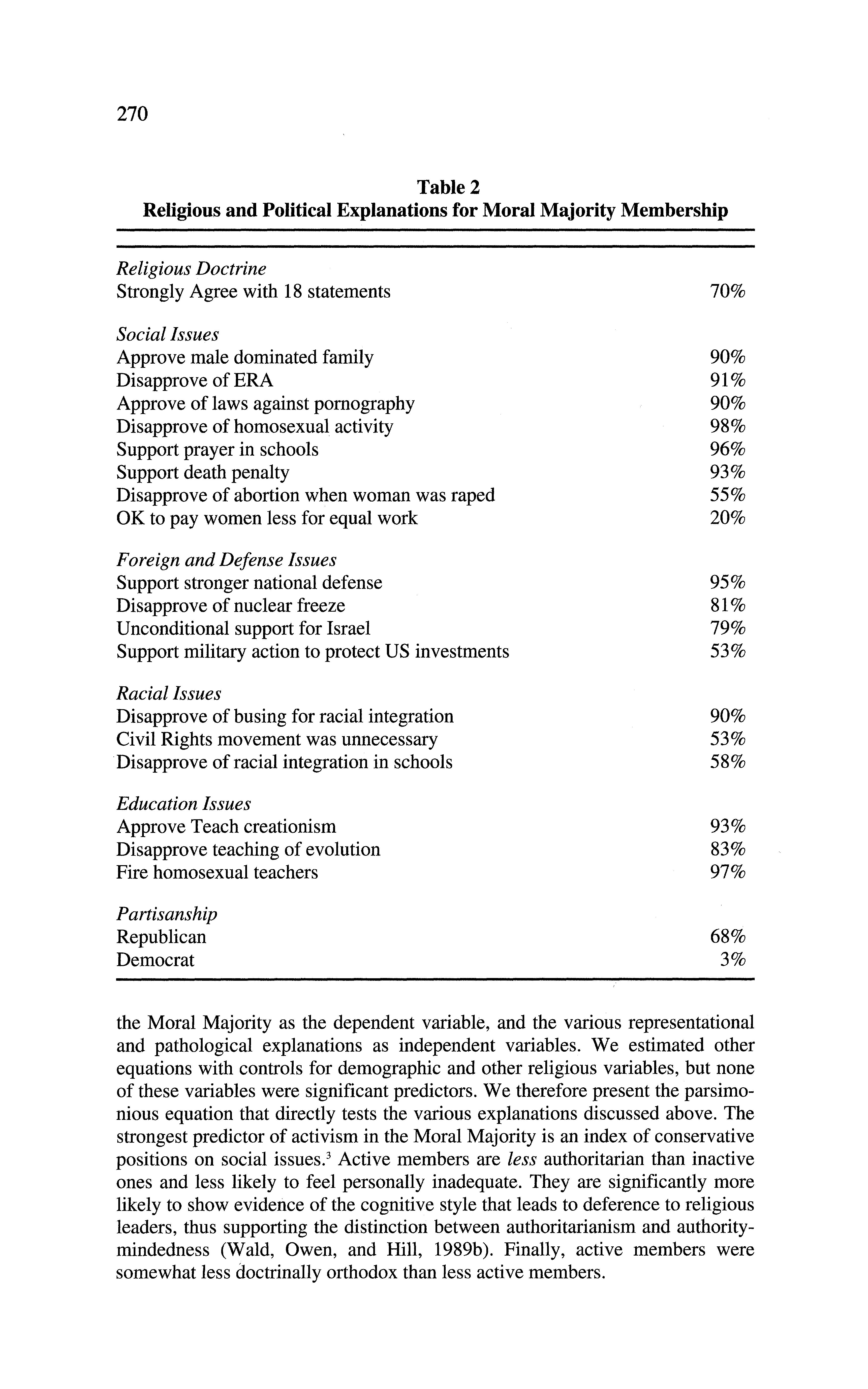

We constructed a measure of activism in the Moral Majority (see Appendix for details). In Table 3, we show the results of an OLS regression, with activity in

Social Issues

Foreign and Defense Issues

Racial Issues

the Moral Majority as the dependent variable, and the various representational and pathological explanations as independent variables. We estimated other equations with controls for demographic and other religious variables, but none of these variables were significant predictors. We therefore present the parsimonious equation that directly tests the various explanations discussed above. The strongest predictor of activism in the Moral Majority is an index of conservative positions on social issues. Active members are less authoritarian than inactive ones and less likely to feel personally inadequate. They are significantly more likely to show evidence of the cognitive style that leads to deference to religious leaders, thus supporting the distinction between authoritarianism and authoritymindedness (Wald, Owen, and Hill, 1989b). Finally, active members were somewhat less doctrinally orthodox than less active members.

Table 3

Multivariate Results

Moral Majority Activism as Dependent Variable

Feelings of Inadequacy -.16* Alienation .07

Status Concerns -.05

Authority Mindedness .24**

Religious Doctrine -.23**

Social Issue Positions .30**

Defense Issue Positions .10

Racial Issue Positions -.10

Education Issue Positons -.04

Partisanship .07

N = 135 R2 = .17

Standardized regression coefficients. *p<.05; **p<.01.

DISCUSSION

The marginal distributions reported in Table 1 suggest the possibility that socially pathological characteristics are related to recruitment into Moral Majority. While we are handicapped by the lack of comparable data for a nonmember population, our results suggest that such people are not uncommon in the Indiana and Arkansas branches of the organization. However, the multivariate data suggest that activism in the Moral Majority was not generally attributable to pathological sources. The single strongest predictor of support was a set of conservative positions on social issues. Moreover, two of the personality explanations are negatively associated with activism. The only hint of a personality-based explanation for activism was the positive relationship between authority mindedness and organizational activity. However, it is not clear that such a relationship should be regarded as pathological. Active members were more likely to indicate that they followed the leadership of Moral Majority officials. Our contextual information suggests that these leaders were primarily local pastors, who urged their members to activity. These data suggest that the Moral Majority in Indiana and Arkansas recruited fundamentalists who agreed with the organization's positions on social issues, and who may have been recruited at the urging of their clergy. We conclude that activism in the Moral Majority was a politically and religiously rational response to an organization that occupied the interstitial zone between doctrinally orthodox religion and conservative politics. This finding, of course, confirms the earlier work of

Simpson (1985b), Page and Clelland (1978) and Wood and Hughes (1984) in a much more stringent setting. Indeed, our results suggest that the variables which account for activity in religiously-conservative political organizations are not qualitatively different from those which predict more passive membership or support.

It is interesting that authoritarianism and feelings of inadequacy are significantly associated with inactivity in the Moral Majority. All political organizations attract some less well-adjusted members, and this study suggests that the Moral Majority may have kept such members at the margins. It is also interesting that the most doctrinally orthodox were less active. Other analysis (not shown) suggests that the most doctrinally conservative members were the most troubled by the mixture of religion and politics that the Moral Majority endorsed, and therefore may have kept their involvement to a minimum

Finally, it may be that psychological pathologies are reduced by the act of political participation itself. The hypothesis that participation in public affairs has an educative effect has a long, distinguished pedigree (see Tocqueville, 1945; Bachrach, 1967; and Pateman, 1970; for an analysis of religiously based activists, see Jelen and Wilcox, 1992). The social interaction in which active participants engage may alleviate some of the personal shortcomings which may have occasioned membership in the first place. A generation ago, Prothro and Grigg (1960) suggested that we need not fear citizens with undemocratic tendencies in our midst, since people holding such undemocratic values were relatively unlikely to participate in politics. The results of this study confirm that possibility and also suggest that participation itself may domesticate some of the pathological characteristics of the Christian Right.

NOTES

We would like to express our gratitude to D. Paul Johnson and several anonymous reviewers for insightful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

1. The Arkansas respondents represented a convenience sample, originally intended simply to pretest the survey instrument. Therefore, a response rate was not calculated.

2. In its original formulation, status inconsistency and anxiety was thought to lead merely to extreme behavior and attitudes. It has been linked in various studies to rightwing behavior, left-wing behavior, alcoholism, seeing flying saucers, and many other extreme behaviors. See Bruce (1988) for a critique of the concept.

3. Since the skewed marginals reported in Table 2 are likely to depress the relationship between social issue position and Moral Majority activism, it seems likely that the equation in Table 3 underestimates the magnitude of that relationship.

REFERENCES

Abcarian, G. and S. Stanage

1965 "Alienation and the Radical Right." Journal of Politics 27:776-795. Adorno, T.E., E. Frenkel-Brunswik, D. Levinson, and N. Sanford

1950 The Authoritarian Personality. New York: Harper. Bachrach, Peter

1967 The Theory of Democratic Elitism: A Critique. Boston: Little, Brown. Bell, Daniel

1963 The Radical Right. New York: Doubleday.

Bruce, Steve

1988 The Rise and Fall of the New Christian Right. New York: Oxford University Press.

Buell, Emmett and Lee Sigelman

1985 "An Army That Meets Every Sunday? Popular Support for the Moral Majority." Social Science Quarterly 66:426-434.

Buell, Emmett and Lee Sigelman

1987 "A Second Look at 'Popular Support for the Moral Majority: A Second Look," Social Science Quarterly 68:167-169.

Chesler, M. and R. Schmuck

1969 "Social Psychological Characteristics of Superpatriots." in R. Schoenberger (ed.), The American Right Wing. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Conover, Pamela

1983 "The Mobilization of the New Right: A Test of Various Explanations," Western Political Quarterly 36:632-649.

Conover, Pamela and Virginia Gray

1981 "Political Activists and Conflict over Abortion and the ERA." Presented at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Cincinnati. Elms, Alan

1969 "Psychological Factors in Right-Wing Extremism." in R. Schoenberger (ed.), The American Right Wing. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Georgianna, Sharon Linzey

1989 The Moral Majority and Fundamentalism: Plausibility and Dissonance. Lewiston, ME: Edwin Mellen Press.

Green, John and James Guth

1988 "The Christian Right in the Republican Party: The Case of Pat Robertson's Supporters." Journal of Politics 50:150-165.

Jelen, Ted G.

1991 The Political Mobilization of Religious Belief. New York: Praeger.

Jelen, Ted G.

1993 "The Political Consequences of Religious Group Attitudes," Journal of Politics 55:178-190.

Jelen, Ted G. and Clyde Wilcox

1992 "The Effects of Religious Self-Identifications on Support for the New Christian Right: An Analysis of Political Activists," Social Science Journal 29:199-210.

Johnson, Stephen, Ronald Burton, and Joseph Tamney

1989 "Pat Robertson: Who Supported his Candidacy for President?" Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 28:387-399.

Lipset, Seymour Martin, and Earl Raab

1978 The Politics of Unreason. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McEvoy, J.

1971 Radicals or Conservatives? The Contemporary American Right. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Pateman, Carol

1970 Participation and Democratic Theory. London: Cambridge University Press.

Prothro, James and Charles Grigg

1960 "Fundamental Principles of Democracy: Bases of Agreement and Disagreement." Journal of Politics 22:276-294.

Rohter, Ira

1969 "Social Psychological Determinants of Radical Rightism." Schoenberger (ed.), The American Right Wing. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Rush, Gary

1967 "Status Consistency and Right Wing Extremism." American Sociological Review 32:86-92.

Sigelman, Lee, Emmett Buell, and Clyde Wilcox

1987 "An Unchanged Minority: Popular Support for the Moral Majority in 1980

and 1984." Social Science Quarterly 876-884.

Tocqueville, Alexis de

1945 Democracy in America 2 vols. Phillips Bradley, editor. New York: Vintage Books. Trow, Martin

1959 Right Wing Radicalism and Political Intolerance. Doctoral dissertation, Columbia University.

Wald, Kenneth D., Samuel Hill, and Dennis E. Owen

1989a "Evangelical Politics and Status Issues," Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 28:1-16.

Wald, Kenneth, Samuel Hill, and Dennis Owen

1989b "Habits of the Mind? The Problem of Authority in the New Christian Right." in Ted G. Jelen (ed.), Religion and Political Behavior in the United States. New York: Praeger.

Wilcox, Clyde

1987 "Popular Support for the Moral Majority in 1980: A Second Look," Social Science Quarterly 68:157-167.

Wilcox, Clyde

1989 "Popular Support for the New Christian Right," Social Science Journal 26:55-63.

Wilcox, Clyde

1991 God's Warriors: The Christian Right in 20th Century America. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Wilcox, Clyde, Ted Jelen, and Sharon Linzey

1991 "Reluctant Warriors: Premillenialism and Politics in the Moral Majority." Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 30:245-258.

Wood, Michael and Michael Hughes

1984 "The Moral Basis of Moral Reform: Status Discontent vs. Culture and Socialization as Explanations of Anti-pornography Social Movement Adherence," American Sociological Review 49:86-99.

APPENDIX

Question Wordings and Reliabilities (All items either strongly agree to strongly disagree, or strongly approve to strongly disapprove, unless otherwise indicated.)

Authoritarianism

A few strong leaders could make this country better than all the laws and talk. One of the most important things children should learn is when to disobey authority (item reverse coded).

In the long run, it is better for our country if young people are allowed a great deal of personal freedom and are not strictly disciplined (item reverse coded). Obedience and respect for authority are the most important virtues children should learn.

Disobeying an order is one thing you can't excuse.

Alpha=.60

Feelings of Inadequacy

I feel that I am a person of worth. (item reverse coded).

I feel that I do not have much to be proud of.

I wish I could have more respect for myself. I certainly feel useless at times.

Alpha=.72

Alienation

How do you feel about your relationship to society?

a.) thoroughly integrated

b.) somewhat integrated

c.) on the fringe of society

d.) alienated

The Moral Majority has made me feel more worthy. Since joining the Moral Majority, I never feel useless.

Alpha=.61

Social Status Concerns

Scale constructed from two items:

Normalized income - normalized education

Normalized head of household job status - normalized father's status

gamma=.55

Authority Mindedness

The leaders of the Moral Majority have the answers I want and I am grateful for those answers.

As a member of the Moral Majority, I must sometimes go along with decisions made by the leaders that I do not like.

The Moral Majority's leaders help me clarify my values so that I can see that their decisions are right.

Alpha=.72

Religious Doctrine

Jesus is the Divine Son of God and I have no doubts about it.

There is a life beyond death.

The Devil actually exists.

God answers prayer.

Christ resurrected from the dead.

Christ ascended into heaven.

God created the world and its inhabitants in six 24-hour days.

Jesus was born of a Virgin.

The Second Coming of Christ could happen at any time.

The state of the world will become so bad that most of the world will welcome the Anti-Christ when he comes to power with "solutions."

If we have a problem, we can go to the Bible for an answer.

The Bible is literally true.

There is a real Hell.

An 'Anti-Christ" will rule on Earth some day as the Bible says. It is important for Christians to tell others about Christ.

Ever since the fall of man, God's people have had to struggle with a sinful nature.

Miracles actually happen.

Born-again Christians will be resurrected as the Bible says.

Alpha=.79

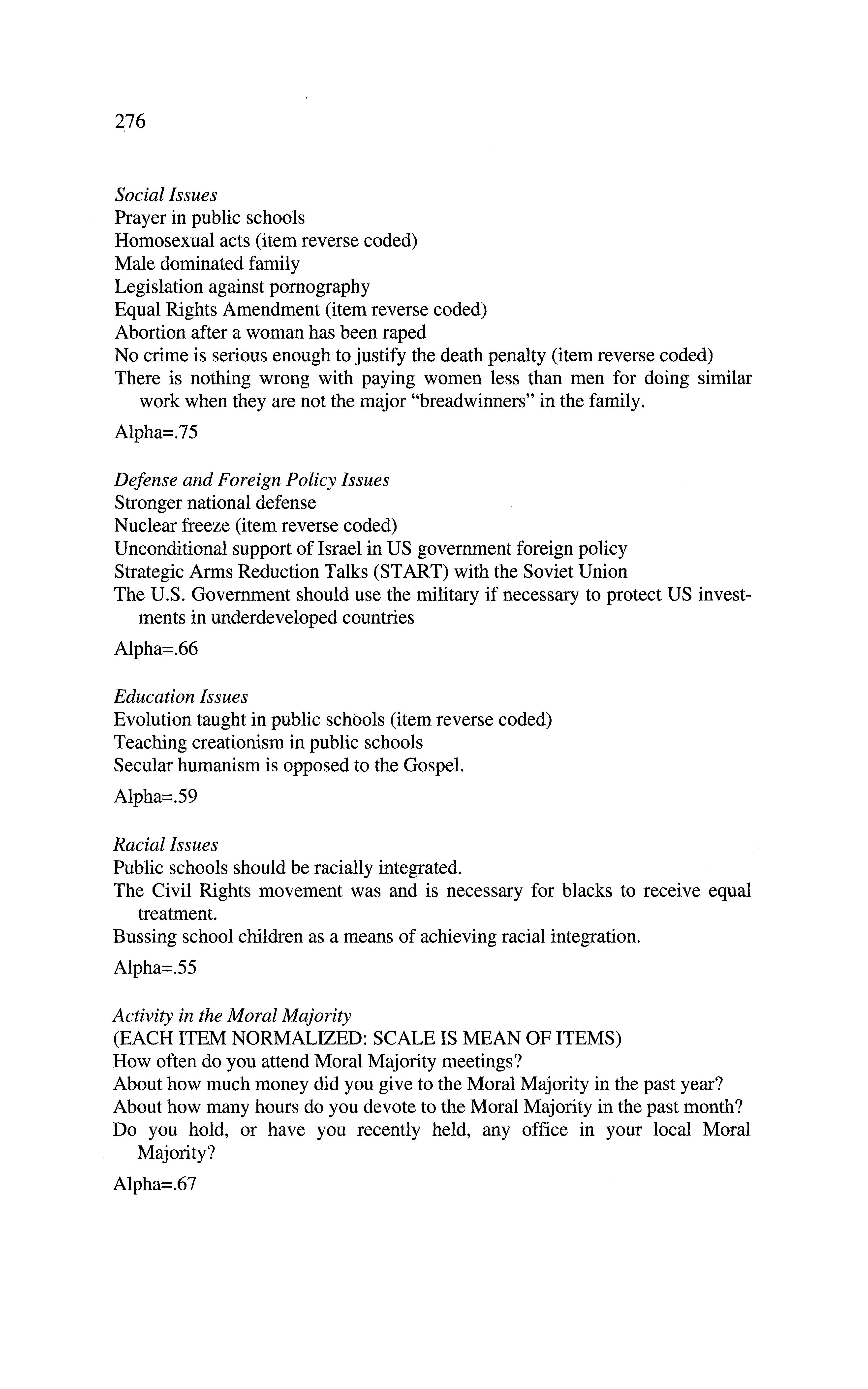

Social Issues

Prayer in public schools

Homosexual acts (item reverse coded)

Male dominated family

Legislation against pornography

Equal Rights Amendment (item reverse coded)

Abortion after a woman has been raped

No crime is serious enough to justify the death penalty (item reverse coded)

There is nothing wrong with paying women less than men for doing similar work when they are not the major "breadwinners" in the family.

Alpha=.75

Defense and Foreign Policy Issues

Stronger national defense

Nuclear freeze (item reverse coded)

Unconditional support of Israel in US government foreign policy

Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START) with the Soviet Union

The U.S. Government should use the military if necessary to protect US investments in underdeveloped countries

Alpha=.66

Education Issues

Evolution taught in public schools (item reverse coded)

Teaching creationism in public schools

Secular humanism is opposed to the Gospel.

Alpha=.59

Racial Issues

Public schools should be racially integrated.

The Civil Rights movement was and is necessary for blacks to receive equal treatment.

Bussing school children as a means of achieving racial integration.

Alpha=.55

Activity in the Moral Majority

(EACH ITEM NORMALIZED: SCALE IS MEAN OF ITEMS)

How often do you attend Moral Majority meetings?

About how much money did you give to the Moral Majority in the past year?

About how many hours do you devote to the Moral Majority in the past month?

Do you hold, or have you recently held, any office in your local Moral Majority?

Alpha=.67