Article

Politics,PovertyandtheChurchinan‘AgeofAusterity’

ChrisShannahan*andStephanieDenningCentreforTrust,PeaceandSocialRelations,CoventryUniversity,CoventryCV12TL,UK

* Correspondence:ac0971@coventry.ac.uk

Abstract: The‘AgeofAusterity’hasrupturedthesocialfabricofcontemporaryBritain.Arisingfrom ourthree-yearLifeontheBreadlineproject,thisarticlerepresentsthefirstfieldwork-ledanalysisof themultidimensionalnatureofausterity-agepovertybyacademictheologiansintheUK.Thearticle analysestheimpactthatausterityhashadonChristianresponsestopovertyandinequalityinthe UK.Wedrawonoursixethnographiccasestudiesandinterviewresponsesfromover120national andregionalChurchleaderstoexemplifythefourapproachestotheChristianengagementwith povertythatweidentifiedduringourresearch:‘caring’,‘campaigningandadvocacy’,‘enterprise’ and‘communitybuilding’.WearguethattheChurchneedstograspthesystemic,multidimensional andviolentnatureofpovertyinordertorealisethepotentialembeddedinitsextensivesocialcapital andfulfilitsgoalof‘transformingstructuralinjustice’.ThepapershowsthattheChurchremains nervousofmovingbeyondwelfare-basedresponsestopovertyandsuggeststhatnoneoftheexisting approachescanforcepovertyintoretreatuntiltheChurchre-imaginesitselfasaliberativemovement thatembodiesGod’spreferentialoptionforthepoorineveryaspectofitslifeandpractice.

Keywords: austerity;inequality;Christianity;Church;poverty;politicaltheology;socialaction

1.Introduction

Citation: Shannahan,Chris,and StephanieDenning.2023.Politics, PovertyandtheChurchinan‘Ageof Austerity’. Religions 14:59. https:// doi.org/10.3390/rel14010059

AcademicEditor:JeffreyHaynes

Received:25September2022

Revised:21December2022

Accepted:22December2022

Published:29December2022

Copyright: ©2022bytheauthors. LicenseeMDPI,Basel,Switzerland. Thisarticleisanopenaccessarticle distributedunderthetermsand conditionsoftheCreativeCommons Attribution(CCBY)license(https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ 4.0/).

Followingthe2010UKGeneralElectionPrimeMinisterDavidCameroninsistedthat austeritywasaneconomicnecessity.Everyoneneededtomakesacrifices.However,the austeritypoliciesthattheCameron-ledCoalitionGovernmentintroducedwerelargely targetedatpeoplewhowerealreadyleftoutorleftbehind.Therolethatfaithgroupshave playedinrespondingtoausterityagepovertyhasbeenextensivelyanalysedwithinthe socialsciencesbutrarelyexploredwithintheology.Theologianshaveengagedwidelywith povertyandinequalityindifferenttimesandplaces,asseen,forexample,intheemergence ofliberationtheologyinLatinAmericabut,todate,therehavebeennoextensiveor empiricallybasedtheologicalanalysesofthemultidimensionalnatureofpovertyand theunequalimpactofausteritypoliciesintheUKsincethe2008globalfinancialcrash. Theperfectstormofstructuralinjustice,theunequalimpactofausterity,theCOVID-19 pandemicandthecurrent‘costoflivingcrisis’raisescrucialquestionsabouttheroleof theologyinaneracharacterisedbydeepeningpovertyandgrowinginequality.Thispaper providesanexampleoftheinterdisciplinarycontextualtheologyofpovertyweargueis neededinthefaceofseeminglyunendingausterity.

DrawingonprimarydatafromourLifeontheBreadlineresearchproject,weargue thattheologiansintheUKneedtodevelopamorenuancedunderstandingofthemultidimensionalandsystemicnatureofpoverty.WerecognisethelonghistoryofChristian responsestourbanpovertyintheUKstretchingbacktotheChristianSocialistmovement inthenineteenthcentury(BradstockandRowland 2002).Furthermore,weacknowledge thehistoricexperienceofausterityamongstBlackandBrownBritons(Beckford 2004)and therootsofthecontemporaryexperienceofpovertyandinequalityintheThatcheryearsof theearly1980s(Whiteside 2016).However,inthispaper,welimitouranalysistoChristian actiononpovertyduringthe‘AgeofAusterity’thatfollowedthe2008globalfinancial crisis,asevidencedinourLifeontheBreadlineresearch.WesuggestthattheChurchneeds

toembraceare-imaginedvisionofitselfasaliberativesocialmovementifitistorealise thepotentialembeddedinitsenduringsocialcapitalandplayakeyroleinturningback theswellingtideofausteritypoverty.

Povertyismultidimensional.Onlyamultifacetedresponsecanadequatelyaddress suchcomplexity.Povertydamagesindividualsandcommunities.Itenactsmultipleforms ofpsychological,existential,economic,structuralandculturalviolence.Consequently, responsestotheviolenceofpovertymustcombineindividualisedsupport(meetingurgent pastoralneeds,empoweringindividualsandenablingenterprise)andcommunalelements (campaigning,advocacyandcommunitybuilding).Critically,acredibleChristianresponse tomultidimensionalpovertyneedstobegroundedinthefundamentalvaluesofliberation theologyandembodytheconvictionthatGodhasapreferentialoptionforthepoorand marginalised.WhilstthispaperarisesfromaUKcontextthechallengesweposeand insightswesharewillresonatewithpeopleseekingtotransformstructuralinjusticein comparablesocietiesacrosstheGlobalNorth.1

2.SurveyingtheTheologicalLandscapeandSituatingThisPaper

2.1.APictureofPoverty

In2020justover14.5millionpeoplewerelivinginpovertyintheUK.Government Ministershaveregularlylaudedworkastherouteoutofpoverty,buttheInstituteforPublic PolicyResearchfoundthatin2021approximately11.7millionofthe14.5millionpeoplein povertywereinpaidemployment.Duringthe2020–2021COVID-19pandemic700,000peoplewerepushedfurtherbelowthepovertyline.Furthermore,theResolutionFoundation suggeststhat,becauseoftheongoing‘costoflivingcrisis’,afurther1.3millionpeoplewere forcedintopovertyduring2022(Belletal. 2022).Suchpovertyismultidimensionaland people’sexperienceofitvariesandisshapedbytheirsociallocation.However,todate theologicalanalyseshavebeenlargelyone-dimensionalandlackedextendedempirical engagement.Theologiansneedtograpplewiththreeinterconnectedchallengesiftheyare tomeetthechallengeposedbyausteritypoverty.

First,itisimportanttocritiquetheindividualisingofpovertybysuccessiveBritish governmentswhohaveattributedittoso-calledmoralinadequacy,ratherthanstructural injustice.Followingthe1997GeneralElectiontheBlairLabourgovernmentplacedaclear focusonstructuralinjustice.ThiswasevidencedintheestablishmentoftheSocialExclusion Unitin1997,theintroductionofaNationalMinimumWagein1999andthecreationofmore than3000SureStartchildren’scentresinsociallyexcludedneighbourhoods.However,as theNewLabourdecadeprogressedpovertywasincreasinglydepictedas“pathological ratherthanendemic”(Levitas 2005,p.7).Asimilarlymoralisticnarrativewasarticulatedby ConservativeChancellorGeorgeOsbornein2012,soonaftertheWelfareReformActpassed intolaw.Osbornedividedpeopleinpovertyinto,‘strivers’workinghardtoprovidefor theirfamilies,and‘skivers’happylivingonBenefits.2 ThisdiscourseechoestheVictorian dichotomyofthe‘deserving’and‘undeserving’poor.Inherexplorationofthis“moral categorizationofpeopleinpoverty”,Muerschallengesthebinarylogicthatunderpinsthis dichotomy,arguingthatobjectifyingpeoplemakesiteasiertoimposeausteritypolicies withoutwrestlingwiththeexistentialandethicalquestionstheyraise(Muers 2021,p.42). Povertymustbeseenasasystemicchallengeifitistobedefeated. Gutiérrez (1974,p.175), thepioneerofliberationtheology,describespovertyasaformofsystemicsin—“asocial, historicalfact”.Suchsin,heargues,“isevidentinoppressivestructures astherootofa situationofinjustice”(Gutiérrez 1974,p.175).WithinourLifeontheBreadlinecasestudy focusingonChristianresponsestothe2017GrenfellTowerfireinNorthKensingtonthe systemicnatureofpoverty,inequalityandhousingjusticewasparticularlyapparent.

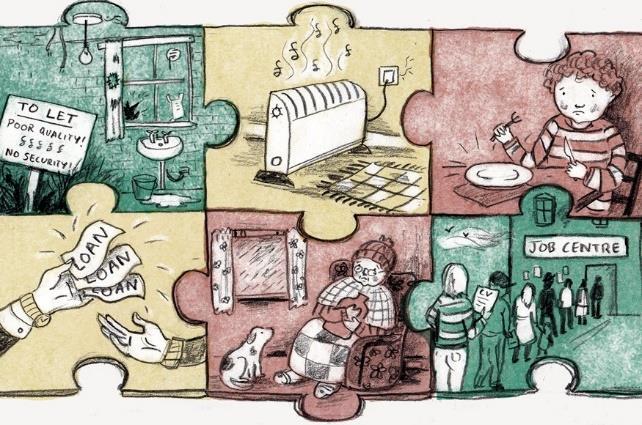

Second,asBethWaters’LifeontheBreadlineimageinFigure 1 belowremindsus, povertyismultidimensional.Foodpoverty,poorhousing,fuelpoverty,personaldebt,child poverty,holidayhunger,lowpayandinsecureemploymentconvergeinanausterityage perfectstorm.Christiansocialactionandtheologicalanalyses,however,oftenaddressjust onepieceofthepovertyjigsaw.

Second, as Beth Waters’ Life on the Breadline image in Figure 1 below reminds us, poverty is multidimensional. Food poverty, poor housing, fuel poverty, personal debt, child poverty, holiday hunger, low pay and insecure employment converge in an austerity age perfect storm. Christian social action and theological analyses, however, often address just one piece of the poverty jigsaw.

Figure1. ‘TheJigsawofPoverty’byLifeontheBreadlineartistBethWaters,2018.

The first generation of liberation theologians grasped the interconnected nature of poverty as Gutiérrez (1988, p. xxi) makes plain: “Poverty [means] … lack of food and housing, the inability to attend properly to health and educational needs, the exploitation of workers, permanent unemployment, the lack of respect for one’s human dignity”. A shift in theological method to focus on the multidimensional nature of poverty and the plurality of our experience is necessary if we are to fashion the kind of holistic analysis of poverty that is needed after a decade of austerity.

Thefirstgenerationofliberationtheologiansgraspedtheinterconnectednatureof povertyas Gutiérrez (1988,p.xxi)makesplain:“Poverty[means] ... lackoffoodand housing,theinabilitytoattendproperlytohealthandeducationalneeds,theexploitation ofworkers,permanentunemployment,thelackofrespectforone’shumandignity”.A shiftintheologicalmethodtofocusonthemultidimensionalnatureofpovertyandthe pluralityofourexperienceisnecessaryifwearetofashionthekindofholisticanalysisof povertythatisneededafteradecadeofausterity.

Third,povertyisanumbingformofviolencethatisembeddedinpolicies,economic structuresandculturalpractices(Shannahan 2018,p.243ff).OurGrenfellTowerandB30 Foodbankcasestudieshighlightthecollectivetraumaenduredduringthe‘AgeofAusterity’. Gutiérrez (1974,p.289)discussestheexistentialnatureofsuchdamage:“Material povertyisasub-humansituation tobepoormeanstobeexploitedbyothers notto knowyouareaperson”.Inasimilarvein Tamez (1982,p.12)suggeststhatpovertyleads tothe“degradationofthehumanbeing,aseizureofthedivineimageinaperson”,what Galtung (1969, 1990)calledstructuralviolence. CooperandWhyte (2017,p.1)suggest thatausterityhad,“devastatinglyviolentconsequences”and PowersandRakopoulos (2019,pp.1–12)arguethattheresultingpovertywasaformof“slowviolence”.Theterm “slowviolence”originatesin Nixon’s(2011)examinationoftheincrementaland,often hidden,violencethatenvironmentaldamagecausestohumancommunity.However,we suggest,with PowersandRakopoulos (2019)and CooperandWhyte (2017)thattheterm alsocapturesthepersistentbutoftenhiddendamagewroughtbyGovernmentpolicysince the2010GeneralElectionandthegrindingtraumaofausterity-agepoverty.

Third, poverty is a numbing form of violence that is embedded in policies, economic structures and cultural practices (Shannahan 2018, p. 243ff). Our Grenfell Tower and B30 Foodbank case studies highlight the collective trauma endured during the ‘Age of Austerity’. Gutiérrez (1974, p. 289) discusses the existential nature of such damage: “Material poverty is a sub-human situation … to be poor means to be exploited by others … not to know you are a person”. In a similar vein Tamez (1982, p. 12) suggests that poverty leads to the “degradation of the human being, a seizure of the divine image in a person”, what Galtung (1969, 1990) called structural violence. Cooper and Whyte (2017, p. 1) suggest that austerity had, “devastatingly violent consequences” and Powers and Rakopoulos (2019, pp. 1–12) argue that the resulting poverty was a form of “slow violence”. The term “slow violence” originates in Nixon’s (2011) examination of the incremental and, often hidden, violence that environmental damage causes to human community. However, we suggest, with Powers and Rakopoulos (2019) and Cooper and Whyte (2017) that the term also captures the persistent but often hidden damage wrought by Government policy since the 2010 General Election and the grinding trauma of austerity-age poverty.

2.2.AllinThisTogether?

2.2. All in This Together?

In 2018 Conservative Chancellor, Phillip Hammond acknowledged that austerity had been a political choice, rather than an economic necessity.3 The introduction of austerity policies reflected a broader depiction of state-based solutions to social problems as barriers to entrepreneurship and competition, which were framed as the drivers of social mobility. Such ideological touchstones formed the backdrop for the ‘Age of Austerity’, a term first used by David Cameron in a 2009 speech intended to contrast fiscal prudence with what he called irresponsible spending (Evans and Walker 2020).4 Both Cameron and George Osbourne went on to make frequent references to the ’Age of Austerity’. By 2018

In2018ConservativeChancellor,PhillipHammondacknowledgedthatausterityhad beenapoliticalchoice,ratherthananeconomicnecessity.3 Theintroductionofausterity policiesreflectedabroaderdepictionofstate-basedsolutionstosocialproblemsasbarriers toentrepreneurshipandcompetition,whichwereframedasthedriversofsocialmobility. Suchideologicaltouchstonesformedthebackdropforthe‘AgeofAusterity’,atermfirst usedbyDavidCameronina2009speechintendedtocontrastfiscalprudencewithwhat hecalledirresponsiblespending(EvansandWalker 2020).4 BothCameronandGeorge Osbournewentontomakefrequentreferencestothe’AgeofAusterity’.By2018welfare spendinghadbeencutby25%andin2022averagewagesremainedlowerthanbeforethe 2008financialcrash.Furthermore,thenumberofpeopleemployedonzero-hourscontracts rosefrom168,000in2010to1,000,000in2020.ChildBenefitwasfrozenin2011andin2012 theWelfareReformActintroducedtheBedroomTaxwhichreducedpeople’sbenefitsby 25%iftheyhadasparebedroom.UniversalCreditcombinedsixpre-existingbenefitsand beganitsnationalroll-outin2014.WhilstChancellorGeorgeOsborneclaimedthat“we

areallinthistogether”,theburdenofausterityhasfallenmostheavilyonpeoplewho werealreadyhurting.Inhis2018visittotheUKtheUNSpecialRapporteuronextreme povertyandhumanrightsobservedthat,“thepoor,women,ethnicminorities,children, singleparentsandpeoplewithdisabilities”hadbeenhitfarharderthanothergroupsby austeritypolicies(Alston 2018,p.18).

Onaverage,austerityhitwomenharderthanmen,partlybecauseofthegendered divisionoflabourinrelationtochild-care(Hall 2018).Consequently,theclosureof600children’sSureStartcentresbetween2010and2019impactedmoreheavilyonwomenthan men.Youngadultswerehitharderthanolderpeople(Edmistonetal. 2017).The2017Social AttitudesSurveyfoundthat17%ofin-work18–25-year-oldswereonprecariousflexible hourcontracts,comparedto5%of36–65-year-olds(Kelleyetal. 2018).Austerityaffected childrenmorethanadults.Between2014and2020thenumberofchildrenlivinginpoverty grewfrom3.8millionto4.3million(HirschandStone 2021).Furthermore,austerityhit childrenfromsomeethnicgroupsharderthanothers.The RunnymedeTrust (2018,p.2) reportsthat,whereas26%ofWhitechildrenwerelivinginpovertyin2018,thisfigurerose to41%forchildrenofdualheritage,47%forBlackBritishchildren,54%amongstchildrenof Pakistaniheritageand60%forchildrenofBangladeshiheritage.Afteradecadeofausterity, theFoodFoundationfoundthatthenumberofchildrenlivinginhomesexperiencingfood insecuritygrewby5%to2.6millioninthefirsthalfof2022alone.5 Disabledpeoplehave beenharderhitbyausteritythanpeoplewithoutdisabilities,asseeninthenewPersonal IndependencePaymentsassessments.Between2013and2018justover160,000people failedworkcapabilityassessmentswhichwerelateroverturnedatappeal.Evenaccess tothebenefitsystemisnotequal.Forexample,thedigitalnatureofUniversalCredit implicitlyexcludespeoplewithlittleaccesstotheinternet(Denning 2019).

Astheimpactofadecadeofausterity,COVID-19andthe‘costoflivingcrisis’have converged,lifehascontinuedtogetharderforthosealreadyleftoutorleftbehind.SuccessiveChancellors,PhillipHammond(October2018)andSajidJavid(September2019) claimedthatausteritypolicieswereending.6 However,theTrussellTrustreportedthat theyhandedout33%morefoodparcelsin2020–2021thanin2019–2020.Furthermore,the Trustnotedthatthegovernment’sreductionofUniversalCreditpaymentsby£20in2021 waslikelytoforcemorepeopletorelyonfoodbanks.7 Thispredictionwasborneoutand betweenApril2021andMarch2022thenumberoffoodparcelsdistributedbytheTrussell Trustincreasedbyafurther14%to2.1million.Theunequalimpactofausterityandthe multidimensionalcharacterofpovertyposekeychallengesforpeopleoffaithcommitted toegalitarianvisionsofthecommongood.BeforeweturntoourLifeontheBreadline researchitisimportanttosummarisekeydebateswithinthesocialsciencesandtheology abouttheroleoftheChurchinrespondingtocontemporarypoverty.

2.3.LiteratureReview—Theology,PovertyandtheRoleofFaithinthePublicSphere

Theliteratureexploringthisdebatewithinthesocialsciencesandcontemporary theologyistooextensivetosummariseinasinglepaper.Consequently,weconfineour reflectionheretoabriefsummaryoffourkeythemes—theroleoffaithinthepublicsphere; faithgroupsengagementwithpovertyduringtheAgeofAusterity;theemergenceofpublic theologyandtherelevanceofCommonGoodteachinginrelationtoChurchengagement withpovertyandthechangingfocusofliberationtheologyinrecentdecades.

2.3.1.TheRoleofFaithinthePublicSphere

In1985theArchbishopofCanterbury’sCommissiononUrbanPriorityAreaspublishedtheirFaithintheCityreport,whichcritiquedtheThatchergovernment’ssocial policiesfordeepeningtheearly1980srecession(ArchbishopofCanterbury’sCommission onUrbanPriorityAreas 1985).Thereport“causedapoliticalstorm”(Dinham 2008,p.2166) andexemplifiedthe‘advocacy’traditionofChristiansocialactiontowhichwepointin thispaper.FaithintheCityrepresentedamomentofprophetictruth-tellingbytheChurch ofEnglandbutGovernmentMinisterslabelledit“pureMarxisttheology”.Thestorm

surroundingthereportexemplifiedabroadersecularistnarrativethatsoughttorestrict religiontotheprivatesphere.

Thesecularismoftwentiethcenturyresearchintoreligion(Weber 1930; Wilson 1966; Berger 1967)wasgraduallydisplacedbyamorenuancedpostsecularperspective(Habermas 2006, 2008; Toftetal. 2011; Casanova 2012)thatrecognisedthatreligionhadnot retreatedtotheprivatesphere,butbecomeincreasinglyvisibleinthepublicrealm(Hoelzl andWard 2008). Dinhametal. (2009,p.1)notedthat“Academics,policymakersandpractitionersaregrapplingwiththeemphaticreturnoffaithtothepublictable”.Inthiscontext, thewaysinwhichfaithgroupsusedtheirenduringsocialcapitalassumedarenewed politicalimportanceandstimulatedgrowingacademicdiscussion(Berger 1997,p.972ff; Baker 2007; Bretherton 2010, 2015; Dinhametal. 2009; BeaumontandCloke 2012; Baker andSkinner 2014; Clokeetal. 2019; Shannahan 2014).From1997onwardssuccessivePrime Ministers,TonyBlair,GordonBrownandDavidCameron,notedthepoliticalsignificance theenduringsocialcapitaloffaithgroupsinlocalneighbourhoodsacrosstheUK. Itwasagainstthisbackdropthattheecumenical FaithfulCities report(Commissionon UrbanLifeandFaith 2006)waspublishedin2006.Asuccessortothe FaithintheCity report, FaithfulCities trodamoreconsensuallinethanitspredecessor,andsoughttonegotiatea spaceforfaithinthepublicsphereandtheworldofsocialpolicy. Bretherton (2011,p.253) suggeststhat“wearegoingthroughaperiodofde-constructionandre-constructionin whichperennialquestionsabouttherelationshipbetweenreligiousandpoliticalauthority arebeingaskedagain”.ForBrethertonthisre-negotiationcanposethreetemptations.First, theChurchcanbetemptedtomuteitsownvoiceandbecome‘co-opted’asaninformal partnerofgovernment.Second,theChurchcanbedrawnintoa‘communalism’thateither pitsdifferentfaithgroupsagainstoneanotherorreducesthepublicroleoffaithtofostering communitycohesion.Third,theChurchcanallowitselftobe‘commodified’.Writingof civicengagementamongstBlackPentecostalchurches, Beckford (2004,pp.8–10)argues that,inspiteofitssocialcapitalinurbancommunities,theBlackChurchoftenresists engagingincivilsocietypoliticsbecauseithasbeen“scaredout”tothesuburbs,“bought out”bygrantsthatfunditscommunityworkor“soldout”to“acrudemixofotherworldly spiritualityandthis-worldlymaterialismthroughproblematicprosperitydoctrinesthat leadinto...aselfishfaith”.

Inthethirty-sevenyearssinceFaithintheCity’spublication,theculturalandpolitical backdroptotheengagementoftheChurchinthepublicspherehasbeentransformed. However,thecharityversuspoliticsdilemmahasnotleftus.Thechallengestowhich BeckfordandBrethertonpointinrelationtotheChurch’sengagementwithausterity-age povertybecameevidentduringLifeontheBreadline.

2.3.2.PublicTheology—FaithandtheCommonGood ScottandCavanaugh (2004,p.1)suggestthat“Theologyispoliticallyimportant andthosewhoengageineithertheologyorpoliticsignorethisfactattheirperil”.As socialscientistshavere-framedtheiranalysesofsecularisationinrecentdecades,political theologianshaveexploredthenatureoffaith-basedengagementincivilsocietypolitics. Theterm‘politicaltheology’originatesintheworkoftheNaziapologistCarlSchmitt. However,theexplorationoftheintersectionbetweentheology,politicaldiscourseand religiouspracticeismostcloselylinkedwiththeexplorationoftherelationshipbetween oppression,hopeandpoliticalpraxisbyJ.B. Metz (1969),Dorothy Soëlle (1993)andJürgen Moltmann (1967)andliberationtheology,whichbegantoemergeinthelate1960s. Politicaltheology’syoungercousin,publictheology,hasarisenasapostsecularand postmodernsocialcontractisemergingwithinwhichfaith-basedengagementinthepoliticsofcivilsocietyhasbecomecommon-place.Theterm“publictheology”,whichwas initiallycoinedby Marty (1974,pp.332–59),needsclarificationbeforeconsideringitsusein discussionabouttheroleoffaithinthepublicsphereintheUK. Stackhouse (2004,p.284ff) suggeststhatthetermresonateswithashiftfromstate-centredtocivilsocietyfocusedframingsofthepublicsphere. Graham (2013,p.xvi)suggeststhatpublictheologyrepresents,

“aquestforanewvoicein apublicdebatethatismorefragmented,moreglobaland moredisparate”thaneverbefore. Stackhouse (2004,p.284)and Lee (2015,p.44)bothnote thatpublictheologyisaconsciousattempttofashionamodeloftheologicaldiscoursethat resourcesthebuildingofaninclusivepostsecularvisionofthecommongood.

TherootsofcommongoodthinkingarefoundinthecanonofEuropeanphilosophy, asfarbackastheworkofAristotle.As Hollenbach (2002,p.4ff)notes,whilstthetermitself maynothavebeenwidelyused,theconceptofthecommongoodwasafeatureofChristian theologicaldiscourseasfarbackasthethirteenthcenturyCE,astheworkofAquinas attests,andformedanimportantaspectofearlyJesuitpracticeinthesixteenthcentury. TheCatholicSocialTeachingtraditionthatoriginateswithPopeLeoXIII’s1891encyclical RerumNovarum (Rowlands 2018, 2021)alignedatheologicalvisionofthecommongood withanethicalcommitmenttodefeatingpoverty(PopeLeoXIII 1891,para.42).Morethan acenturylater,RomanCatholicBishopsinEnglandreturnedtosuchthinkingaheadofthe 2010UKGeneralElection,suggestingthat—“Thecommongoodreferstowhatbelongs toeveryonebyvirtueoftheircommonhumanity ... Thecommongoodisabouthowto livewelltogether ... Attheheartofthecommongoodsolidarityacknowledgesthatall areresponsibleforall”(BishopsConferenceofEnglandandWales 2010,p.8).Writing intheyearofthefinancialcrash Bedford-Strohm (2008,pp.144–62)arguedthatpublic theologyprovidestheChurchwithameansofarticulatingamodelofthecommongood thatispremisedonGod’sPreferentialOptionforthePoor.However, Hollenbach (2002, p.19ff)remindsusoftheneedtointerrogatetheextenttowhichpoliticalandtheological appealstothecommongoodcolludewithorchallengestructuralinjustice.

DuringLifeontheBreadline,manyoftheChurchleaderswithwhomwespokeidentifiedavisionofthecommongoodthatisshapedbyacommitmenttoGod’sPreferential OptionforthePoorasthebasisfortheirdenomination’sengagementwithcontemporary poverty.Thisemphasiswasalsoevidentinourethnographiccasestudies.However,we suggestthatitisalsoimportanttorecognisethatade-politicisedframingofthecommon goodasthebasisforChristianengagementwithausterity-agepovertywillleavestructural injusticeintact(Dorrien 1990,p.4ff).Inthefaceofsystemicinjusticeandpersistentausterity shouldtheChurchuseitssocialcapitaltofeedthehungryandclothethenakedortoagitate forstructuralchange?

2.3.3.TheologyandFaith-BasedEngagementwithAusterity-AgePoverty

Whereasresearchersfromthesocialscienceshaveextensivelyanalysedthewaysthat faith-basedorganisationshaverespondedtoausterity-agepovertythisisnotathemethat hasbeenwidelyconsideredwithintheology,therebyaddingtothecontributionthatthis papercanmaketothisdiscussion.However,itwouldbeuntruetosuggestthattheologians havecompletelyignoredUKpovertyoverthelastdecade.Fourstrandsofthistheological discussionareimportanttonote.

First,therenewedvisibilityoffaithinthepublicspherehasraisedquestionsaboutthe motivationthatshapesChristianengagementwithpovertyandthenatureandpurposeof theologicaldiscourseinanAgeofAusterity. Bradstock (2010,p.135ff)arguesthat,duetoits longstandingethicalengagementwiththechallengesofbuildinginclusivesocietieswithin whichallpeoplecanflourish,theologycanofferavaluablecritiqueoftheassumptions thatunderpinausterity-ageeconomics.Bradstock’sworkinvitesus,toreflectafreshonthe valuesthatdroveadecadeofausterity. GastonandShakespeare (2010,p.793ff)commenton theemergentBigSocietyinitiativeheraldedbythethenPrimeMinisterDavidCameron.On thebasisoftheirconvictionthat“Jesusstandsinsolidaritywiththosewhohavenothing” (GastonandShakespeare 2010,p.800)GastonandShakespearearguethatChristianshave atheologicalresponsibilitytochallengetheeconomicandethicalbasisforausterity—“to resistthelureoftheBigSocietyandtoworkinsteadwiththosewhoresistthecutstojobs andservicesandseekwithotherstobuildamovementforaradicalsocialalternative” (GastonandShakespeare 2010,p.801).

Second,aclutchofpapershavereflectedonfoodpoverty,and,inparticular,onfoodbanksassitesoffaith-basedactivism. Cameron (2014)affirmstheimmediatepastoral valueofthefoodbankresponsetopoverty.Shesuggests,however,thattheChurch’s wholeheartedsupportforthefoodbankmodelrunstheriskofunconsciouslycolluding withunjustausteritypoliciesandmaskingdeeperstructuralinjustice. Allen (2016)and Pemberton (2018, 2020)haveengagedinadialogueabouttheintersectionbetweentheology,austerityandfoodbankresponsestopoverty.Usingthefoodbanktoexemplifyhis argument, Allen (2016)critiquesthetwodominantapproachestoChristiansocialaction— charitablegivingandcampaigningforsocialjustice.ForAllen,acharitableapproach confirmsasymmetricpowerrelationsandfostersalevelofdependencythatinhibitsthe agencyofpeoplelivinginpoverty.Equally,for Allen (2016),asocialjusticemodelremains confinedwithinthehegemonicparametersofcapitalism.Instead, Allen (2016)argues,the Churchneedstomodelpatternsofinclusivefellowship,mutualityandhospitalitythat fosterthecreationofnewpatternsofsocialrelations. Pemberton (2018,p.2)arguesthat Allen’sconclusionis‘insufficientlyradical’.IncontrasttoAllen, Pemberton (2018)suggests thattheChurchshouldengagewiththeeconomyandthestate.Aligninghisargumentwith theworkofgeographerssuchasAndrew Williamsetal. (2016)onfaith-basedsocialaction, Pembertonarguesthatfoodbankshavepotentialtoactastransformativepoliticalspaces. Third,thelastdecadehasgivenrisetoasmallnumberoftheologicalpapers,exploring theperfectstormcausedbytheinterrelationbetweenwhat Jones (2019,p.154)calls“welfarestateretrenchment”,risinglevelsofhomelessness,housinginjusticeandtheimpactof austeritypoliciesonalreadymarginalisedcommunities.WritingaboutChristianresponses tothe2017GrenfellTowerfire, Shannahan (2022,p.269)arguesthatthetragedy“symbolizesthecrueltyofthe‘ageofausterity’thatfollowedtheglobalfinancialcrash”.Both Jones (2019)and Shannahan (2022)demonstratetheimportanceoffieldworkwithincontemporarypoliticaltheologyandillustratetheneedtobroadentheologicaldiscussionsabout austerity-agepovertybeyondthefoodbank. Shannahan (2022,p.275ff)arguestheneedto understandgrindingausterity-agepovertyasaformofunresolvedcollectivetrauma. Jones (2019,p.154)drawsourattentiontotherelationalandexistentialimpactsofpovertyand thewaysinwhichthesecanundermineChristianappealstothecommongood—“Thereis aprofoundethicalandtheologicalchallengetothecommongoodintheuncomfortable realitythatsomemembersofsocietyhavesuchlowexpectationsandaspirations”.

Fourth,asmallnumberoftheologiansintheUKhavedrawnontheexperienceof austerity-agepovertytoreflectonthenatureandpurposeofChristiancommunityand witness.Writingaboutachurch-basedcoldweathershelterinLondonandthebroader workofSalvationArmyhostelsforthehomeless Duce (2013)and Button (2018)arguethe needtore-framethinkingaboutChristianresponsestohomelessnessaroundanethicof hospitalityandmutualwell-being.Arisingfromhisministryonanoutercityestatein Birmingham, Barrett (2018)considershowthedevelopmentofaradicallyreceptivemodel ofecclesiologyshapedbyanethicofsolidaritycanenablecommunitybuildingintheface ofstructuralinjustice.

Werecognisethevalueofsuchtheologicalanalyses,butsuggestthatnonehave engagedinanyextendedempiricaldepthwiththemultidimensionaldynamicsofausterity. TheologyintheUK,therefore,isstilltorespondinsustaineddepthtothecriticalchallenge embodiedbyausterity-agepoverty.

2.3.4.TheChangingFocusofLiberationTheology

TheinfluenceofLatinAmericanliberationtheologyhasbeenimmense,sinceitsemergenceinthelate1960sandearly1970s.MostoftheChurchleaderswithwhomwespoke duringLifeontheBreadlineidentifiedthefoundationaltheologicalvaluesofliberation theologyastheethicalbasisfortheirdenomination’sengagementwithcontemporary poverty.Wehavealreadynotedthewaysinwhichtheworkofliberationtheologianslike GutiérrezandTamezcanenrichourunderstandingofthesystemicandviolentnatureof austerity-agepoverty.GiventheabidinginfluenceoftheclaimthatGodhasaPreferential

OptionforthePooritisimportanttocommentbrieflyonthedevelopmentofliberation theologyandtoconsideritsrelevanceintheUKhalfacenturyafterGutiérrez’publication ofitsseminalfoundingtextATheologyofLiberation.

TherehassometimesbeenatendencytotreatLatinAmericanliberationtheology asafixedsetofideasthatcanbeimportedwholesaleintowidelydifferentsituations—a product,ratherthanaprocess.Liberationtheology,accordingtoRowland,“isnotabody ofknowledgethatcanbelearntbutawayofunderstandingGodinthemidstofhistory” (BennettandGowler 2012,p.8).Consequently,whilstthetermwasfirstadoptedbythe CatholicBishopsofLatinAmericainMedellinin1968,thetheologicalargumentthatGod hasaPreferentialOptionforthePoorisasrelevantinausterityBritainasitwasintheLatin AmericanChurchbecauseliberationtheologydoesnotrepresent“detachedreflectionon Scriptureandtraditionbutthepresentlifeofshantytownsandlandstruggles”(Rowland 1999,pp.2–3). Gutiérrez (1974,p.302)summarises,“Thepoordeservepreferencenot becausetheyaremorallyorreligiouslybetterthanothersbutbecauseGodisGod,inwhose eyesthe‘lastarefirst’”.Intheyearsfollowingtheemergenceofliberationtheologyattempts weremadetoembeditsideasintheUK,notleastintheworkofJohn Vincent (1986)at theUrbanTheologyUnit.However,manyoftheseearlyattemptstoarticulateaBritish liberationtheologydidnottakesufficientaccountoftheneedtoadoptacriticalapproach tocontextualisingitstheologicalmethodologyintoadramaticallydifferentsocio-cultural context(Shannahan 2010).

Acriticalengagementwithliberationtheology’scorevaluesandmethodologyis essentialifitspotentialistoberealisedasatheologicalforceforsocialchangeinbreadline Britain.ThemovementthatbeganinLatinAmericawithitsoverridingfocusoneconomic povertyandsocialclasshasevolvedasithasemergedindifferentcontextsinrelationtoa diverserangeofliberationstruggles.Thepedagogicalandphilosophicalrootsofliberation theologyintheworkofPaulo Freire (1970)pavedthewayforatheologicalengagement withmultipleformsofoppressioninadiverserangeofcontexts. Freire’s(1970)focus ontheimportanceofconscientisationofthemultidimensionalcausesofoppressionas thefirststepinthedevelopmentofthestruggleforliberationformedthebasis,notonly forthearticulationofliberationtheologyinLatinAmericabutalsofortheemergence ofawide-rangeoftheologiesofliberationinothercontexts.TheearliestformsofLatin Americanliberationtheologycanbecritiquedforneglectingotherformsofoppression andthewaysinwhichtheircombinedimpactcandeepentheexperienceofpoverty.The historyofstruggleforracialjusticewithintheBlackChurchanditsconfluencewiththe USCivilRightsandBlackPowermovementsgaverisetotheBlackliberationtheology exemplifiedbytheworkofJames Cone (1975)intheUSandRobert Beckford (1998)and Anthony Reddie (2008)intheUK.Comingtobirthatasimilartimefeministandwomanist liberationtheologiescritiquedtheneglectofgenderbyLatinAmericanandNorthAmerican liberationtheologiansandplacedwomen’sexperienceofoppressionandthecombined impactofsexismandracismattheheartoftheologicalmethodology,asseen,forexample, intheworkofRosemary Radford-Ruether (1983)andJacquelyn Grant (1989).Athird arenaofstrugglewithinwhichthetheologicalfoundationsofliberationtheologyhave beendeployedrelatestosexuality,theexperienceofhomophobiaandthedevelopmentof liberativeQueeridentities,asillustratedbytheworkofMarcella Althaus-Reid (2002).In recentdecades,thecorevaluesofliberationtheologyhavebeenbroughtintodialoguewith arangeofstrugglesforsocialjusticeandinrelationtobroaderpostcolonialmovements (Sugirtharajah 1991; Pui-Lan 2021).

WhilstitsinitialstimuluswasthepovertyandinequalityofLatinAmericathephilosophicalthrustofliberationtheologyhasgivenitalifebeyonditsinitialcontext,ensuring, wesuggest,itsongoingrelevanceinbreadlineBritaininthetwenty-firstcentury.ItsassertionthatGodhasaPreferentialOptionforthePooranditscommitmenttoamodelof theologicalanalysisthatarisesfromandprioritisesthevoiceofthosewhohavebeenleft outorleftbehindresonateduringanAgeofAusterity.However, Petrella (2006)reminds usthattheworldinwhichthefirstgenerationofliberationtheologianswrotehasbeen

transformed.TheColdWarandstate-centricstrugglesofthe1970sand1980shavefaded fromview.Strugglesforsocialjusticeareincreasinglymultidimensionalandlivedoutin thecontextofadiverseandarguablypostmodernandpostsecularcivilsociety. Petrella (2006,p.11ff)arguesthatliberationtheologyneedstore-defineitselfinrelationtoanew worldandanewcentury.WithinthispaperandourbroaderLifeontheBreadlineresearch,wearguethattheAgeofAusterityprovidesliberationtheologywiththisnewarena ofstruggle.

3.Methodology

LifeontheBreadlinewasthefirstempiricalprojectledbyacademictheologiansin theUKtoanalysethemultidimensionalimpactofthe‘AgeofAusterity’onChristian responsestocontemporarypoverty.Ourinterdisciplinaryresearchdrewpoliticaltheology andthesocialsciencesintoacriticaldialogue.Adoptingatriangulatedqualitativeapproach between2018and2021combiningethnographiccasestudies,focusgroups,semi-structured interviewsandanonlinesurvey,webuiltthemostextensivetheologicalevidence-baseto dateontheChristianengagementwithcontemporarypovertyintheUK.8

WeinterviewedsixteennationalChurchleadersfromthirteennationalChurchesinthe UK,defininganationalChurchasadenominationthatadherestotheChristiandoctrine oftheTrinityandthathasaclearnationalpresenceinmorethanonegeographiccity orregionintheUK,andinturndefinedanationalChurchleaderasaseniorleaderin theirdenomination.Thesein-depth,semi-structuredinterviewslastedapproximatelyforty minutes,andChurchesnotrepresentedeitherturneddownaninterviewrequestordid notrespond.Next,weundertookanonlinesurveyin2019with104regionalChurch leadersfromseventeennationalChurchesacrosstheUK;aregionalleaderbeingdefinedin relationtothegeographicareasusedinnationalChurchstructures.Thesurveycoveredthe respondent’sroleandbackground,theirunderstandingofpoverty,theirChurch’sresponse topoverty,andtheirthoughtsonpovertyinrelationtotheGovernment.The104regional leadersrespondedtothesurveyinvitationfromthe375regionalleaderswhowereinvited toparticipate.AsthereisnodefinitivelistofnationalorregionalChurchleaders,thiswas subjecttoinformationthatwasavailablein2019.

Finally,between2019and2021weundertooksixethnographiccasestudiesacross London,Birmingham,andManchester—NottingHillMethodistChurchandPowerthe FightinLondon,B30FoodbankandHodgeHillChurchinBirmingham,andChurch ActiononPovertyandInspireCentreinManchester.Thesecasestudieswerechosento focusonChristianresponsestopovertyinthreeofthelargestcitiesintheUK,toaddress varyingaspectsofpovertyandtoreflecttherangeofChristianresponsestopovertyin theUK.Eachcasestudyinvolvedoneoftheresearchteamspendingtimeparticipating withandobservingactivitiesrunbythecasestudyandkeepingnotesofobservationsand reflections.Aspartofeachcasestudyinterviewswerecarriedoutwithstaff/volunteers andclients/localresidents,andwherepossible(subjecttotheCOVID-19pandemic)focus groupswerearrangedwhichincludeddiscussingphotosthatparticipantshadtakenof theirlocalcommunities.Interviewandfocusgroupparticipantswereselectedbasedon openinvitationsfromtheresearchersinthefieldtopeoplewhotheymetateachofthe casestudies.

Intheologicaltermsthispaper,liketheLifeontheBreadlinestudyfromwhichitarises, isanexampleofliberativecontextualtheology.Wedonotattempttoforgeasystematic theologyofausterity-agepoverty.Rather,wedrawonthemethodologyfoundwithin contextualtheology(Bevans 1992; Schreiter 1985; Pears 2010)toframethedialoguewe establishbetweenprimarydata,thesocialsciencesandtheology.

4.Discussion

4.1.MappingChristianResponsestoAusterity-AgePoverty

DuringourfieldworkfourbroadapproachestoChristianengagementwithpoverty becameevident:‘caring’,‘campaigningandadvocacy’,‘enterprise’,and‘community

building’.Theseapproachesarefluidandevolvingand,onoccasions,mergeintoeach other.TheydonotrepresentarigidtypologynortheentiretyofChristianresponses topovertyintheUK.Nevertheless,theseapproaches,identifiedduringourfieldwork, reflectarangeofwell-establishedChristianapproachestosocialethicsandresponsesto poverty.Theseapproachesexemplifyarangeofecclesiologicalperspectivesandframe theroleoftheChurchinthepublicsphereindifferingways.However,allfourarticulate theneedforchangeinoneormoreofthefollowingareas.Thechangeenvisagedcan focusonindividualsinrelationtopersonalempowermentandresistingandovercoming stigmatisingpoliticaldiscoursesabouttheplaceswelive.Itcanrelatetoindividualspiritual changeinthecontextofworshiporinrelationtopersonalbeliefsabouttheimplications ofBiblicalteachingonpoverty.Alternatively,suchchangecanrelatetothenatureof congregationallife,therolelocalchurchesplayinthepublicsphere,theimpactthatsocial actioninrelationtopovertyhasonotherareasofchurchlifeandonunderstandingsof mission,forexample.Third,suchchangecanrelate,primarilytotheroletheChurch playsinactivelyseekingtobringaboutstructuraleconomicandpoliticalchange,locally ornationallyasameansofembodyingtheChurch’scallingto“transformstructuresof injustice”.Arisingfromourexperienceduringfieldwork,thispaperarguesthattheChurch needstorecognisetheneedfortransformativechangeatindividual,congregationaland systemiclevelsasitseekstorespondtothemultidimensionalcrisisofausterity-agepoverty.

4.1.1.A‘Caring’ResponsetoPovertyintheUK

ThemostwidelyadoptedChristianresponsetoausterity-agepovertythatweencounteredduringourresearchreflectsa‘caring’socialethicandtheemphasisonloving ourneighbourintheteachingofJesus(seeJohn13:34–35,Matthew22:39andMatthew 5:43).Thiswelfare-basedtraditionwastheapproachmostwidelycitedinournational ChurchleaderinterviewsandregionalChurchleaders’survey.Weacknowledgethatin historictermstheChurchintheUKplayedaroleinmaintaininganunequalstatusquo andjustifyingpovertyasanexpressionofGod’swill.This,atleastinpart,stimulatedthe emergenceofliberationtheologyinLatinAmericainthe1970s.

Duringthe‘AgeofAusterity’asstatutoryauthoritieswithdrewlocalchurcheswere keyplayersinthedevelopmentof‘caring’responsestogrowingpoverty.Thevalueofsuch apastoralresponseisimmensebutthetemptationtoframethisapproachasinherently apoliticalwouldbeamistake.AswediscoveredduringLifeontheBreadlineitremains thecasethatmanyChurchleadersframewelfare-based‘caring’responsestopovertyas expressionsofanethicalcommitmentto‘lovingyourneighbour’,ratherthaninterventions inthepoliticalarena.However,ourresearchimpliesanalternativeconclusion.Inthe faceofpersistentausteritypoliciesthatundermine,notjustthecommongood,butalso thewellbeingofindividuals,theconsciousprioritisingofpeopleforcedintopovertyasa resultofGovernmentpoliciesrepresentsanimplicitinterventioninthepoliticalsphere. Theinterconnectionbetweenthepersonal,thepoliticalandtherelationalwithin‘caring’ responsestopovertyisemphasisedwithinfeministpoliticaltheoryandsocialgeography asdemonstrated,forexamplein Hall’s(2020)workonausteritypolitics

Anexampledrawnfromourfieldworkmakesthisclear.TheChristianinvolvement infoodbanksexemplifiesthe‘caring’response,asillustratedbyourcasestudyoftheB30 FoodbankinSouthBirmingham.AclientatB30Foodbankreflected: “Thisisamazing, itreallyis,Idon’tknowwhatIwouldbedoingwithoutthisplace.Ireallydon’t” (Interview 2019).9 InLent2014anecumenicalgroupofChurchleaderswrotetoPrimeMinisterDavid Cameron,arguingthathisgovernment’spolicieshadforcedarapidlygrowingnumberof peopletorelyonfoodbankstosurvive.10 Thisactionexemplifiedafusionofthe‘caring’ ethicandthe‘advocacy’approachtochallengingpovertytowhichwereferbelow.A fewweekslaterinhisEastersermonJustinWelby,theArchbishopofCanterbury,saidhe sensedthepresenceoftheRisenChristinfoodbanks,describingvolunteersasprophetic witnessestotheEasterGospelofGod’ssolidaritywithpeoplelivinginpoverty.11 However,

B30volunteerswereambivalentaboutfoodbanks—“arewejustpaperingoverthecracks?” (Interview2019).

Itbecameclearduringourresearchthatthe‘caring’approachwillnotenablethe ChurchtofulfilitscommitmentwithintheMarksofMissionto‘transformstructural injustice’,unlessitmovesbeyondpastoralcaretoagitateforsystemiceconomicchange, astheTrussellTrust,thelargestChristianproviderofUKfoodbanksrecognises.12 During the1980sand1990sChristiandenominationsintheUKreflectedontheirsenseofpurpose andunderstandingofmission.In2000,theBritishMethodistConferenceadopted’Our Calling’—fourcommitmentsthatsummarisedaMethodistunderstandingofChristian teachingandmission.WithinthestatementitwassuggestedthatMethodistsarecalled to”begoodneighbourstopeopleinneedandchallengeinjustice”.13 WhilstMethodism’s ‘OurCalling’soughttobroadenunderstandingsofmissionithastendedtoplacean overwhelmingemphasisonwelfare-oriented’service’initspublications,resourcesfor localchurchesandpromotionofitswork,ratherthanproactively’challenginginjustice’. In2021theMethodistChurchestablishedits‘WalkingwithMicah’initiative,whichhas soughttoarticulateaclearertheologicalandmissiologicalunderstandingofthecalling to’challengeinjustice’.However,itisthe’MarksofMission’,whichfirstemergedfrom theAnglicanConsultativeCouncilin1984thathave,arguably,hadawiderinfluenceon ChristianengagementwithpovertyintheUK. Zink (2017,p.144)suggestedthatthey“have attainedanomnipresencewithinAnglicanandEpiscopalthinking”.TheMarksofMission havealsoinfluencedthethoughtandpracticeofecumenicalbodiessuchasChurches TogetherinBritainandIreland,whichincludesmorethanfortyChristiandenominations, aswellasbeingadoptedbyotherdenominationssuchastheChurchofScotland.14 The reachofthe’MarksofMission’isextensiveandecumenical,addingtotheirsignificance asasummaryofcontemporarymissiologicalthinkingintheUK.Consequently,their inclusionofcampaigningforstructuralchangeasakeyfeatureofChristianmissionhas thepotentialtoinfluencesocialactionwithinawiderangeofdenominations.Asthe fourthMarkofMissionnotesacentralaspectofChristianmissionisto,“seektotransform unjuststructuresinsociety”.Weask,therefore,iftheChurchneedstoadoptamore theologicallyradical’campaigning’approachtoausterity-agepovertyinitsattemptto challengestructuralinjustice.

4.1.2.A‘CampaigningandAdvocacy’ResponsetoPovertyintheUK

The‘campaigningandadvocacy’responsetoausteritypovertyistheinheritorofa longstandingtheologicalandecclesiologicaltraditionthatemphasisestheprimacyofsocial justiceoverwelfare.ThisapproachfocuseslargelyonthestructuralimplicationsofGod’s preferentialoptionforthepoor.Thistraditiondatesbackmanycenturiesasexemplifiedby theearlyFranciscansandAnabaptists,theLevellers,theTolpuddleMartyrs,theVictorian ChristianSocialistsandLatinAmericanliberationtheology(BradstockandRowland 2002). Whilst,liketheologiesofthecommongood,liberationtheologyisinfluencedbyCatholic SocialTeaching,pioneeringfigureslike Gutiérrez (1974)interpretedtheassertionofGod’s preferentialoptionforthepoorinamorepoliticallyradicalmanner. Petrella (2006),however,cautionsagainstrecyclingatheologicalmovementthatwasacontextualresponseto thetwentiethcenturyparticularitiesofLatinAmerica.Wesuggest,however,aswenoted aboveinSection 2.3.4,thattheperfectstormofpre-existinginequality,austerityandthe ongoing‘costoflivingcrisis’presentanewarenaofstrugglewithinwhichthefoundational methodsandvaluesofliberationtheologycanresourcetheChurchinBritainto‘transform structuresofinjustice’.

LifeontheBreadlineuncoveredmanyexamplesofthisapproachtopoverty.Here,we highlighttwoofourcasestudies.First,drawingonitsnationwidesupporterbase,Church ActiononPovertyinitiatedandledtheEndHungerUKcampaignbetween2016and 2019.ThisreflectedChurchAction’scommitmenttochallengingstructuralinjustice,asour interviewwithLiamPurcellshows—“Weneedtotalkabouttherootcausesofpoverty It’snot enoughtodolocalsocialaction” (Interview2020).EndHungerdrewsupportfromChurches

acrosstheUKandalmostfortyChristianNGOsandexemplifiedthekindofconcerted actionneededto‘transformstructuralinjustice’(Lambie-Mumfordetal. 2019).By2020 thecampaignhadhelpedtosecuremoregovernmentfundingforprojectstacklingholiday hunger,aU-turninrelationtocutstoUniversalCreditand,in2021,theintroductionofa governmentalassessmentoflevelsoffoodinsecurity.15 Second,theworkoftheRevdMike Long(MinisteratNottingHillMethodistChurch)withthehomelessnesscharityShelter followingthe2017GrenfellTowerfire,exemplifiestheprophetictraditionofspeakingtruth topower.Intheconclusionto Shelter’s(2019) BuildingforourFuture report,Longargued thatsocialhousinghadbeen“devaluedandneglected”bysuccessiveUKgovernments andinsistedthat“everyone,nomattertheirincome,deservesadecentplacetolive ... The timeforthegovernmenttoactisnow”(Shelter 2019,p.5).

ManyoftheChurchleaderswhoparticipatedinLifeontheBreadlineemphasised theChurch’scommitmenttochallengingsystemicsinand‘transformingunjuststructures’.16 Speakingaboutthecollectivetraumaofadecadeofausteritypolicies,RevdMicky Youngson,formerPresidentoftheBritishMethodistConferencesaid:

JohnWesleysuggestedthatthereasontherichdon’thelpthepoorisbecausetheydon’t spendanytimewiththem Ithinkthere’sacontinuinglackthathasgotworsewith thislatestgovernmentofempathy,ofunderstandingofwhatitmeanstoliveonthe breadline,tomakethatcanofspamlasttwomeals.(Interview2020)

InasimilarveinRevdDrRichardFraseroftheChurchofScotlandsuggestedthat“the failingsofthesystemthatledtothefinancialcrisisof2008havebeenpaidforbythepoorestin society”.HearguedthattheChurchneedstomovebeyonda “stickingplaster” response topoverty.ForFraser “ourcampaigningis drivenbyourreadingoftheGospelanda recognitionthatJesushadaparticularbiastothepoorandtothepeoplewhowereinhabitingthe marginsofsociety” (Interview2020).ThiscommitmenttoembodyGod’spreferentialoption forthepoor—transformingstructuralinjustice,aswellasmeetingtheimmediateneeds ofthehomelessandthehungry—hasmajorimplicationsfortheChurch’sengagement withausterity-agepoverty.However,ourinterviewswithChurchleadersillustratean ambivalencetowardssocialactionthatisintendedtostimulatestructuraleconomicand politicalchange.WhilstsomeChurchleaderscalledtheneedto‘transformstructural injustice’a“gospelimperative”,otherswerenervousaboutmovingfromcharitableactivities intomoreexplicitlypoliticalaction.ABaptistChurchleaderfromNorthernEngland summarised, “Respondingtopovertyisprioritisedasanactofservingothersorofferinghospitality. Campaigningandadvocacyaremorepoliticalandthereforemaybeseenastoopartisan”(Survey 2020).DuringLifeontheBreadlinesomenationalandregionalChurchleadersexpressed anuncertaintyaboutengagingincivilsocietypolitics.Here,however,thisBaptistleader reflectedafearoftheChurchbeingperceivedasbeingengagedinPartypolitics.

ArelatedChristianapproachtopovertythatweencounteredduringLifeonthe Breadlinefocuseson‘advocacy’.ThepracticeofChurchleadersspeakingtruthtopower isnotnew.Asfarbackas1942ArchbishopWilliamTemple’s ChristianityandSocialOrder challengedpolicymakerstoforgeanewinclusivesocialcontract.FortyyearslaterChurch ofEnglandBishopsexemplifiedsuchprophetictruth-tellingintheir1985 FaithintheCity reportwhichcritiquedMargaretThatcher’ssocialpoliciesfordeepeningpovertyand fuellinginequality.In2013ArchbishopofCanterbury,JustinWelby,arguedthat2012 s WelfareReformBillwouldentrenchdamaginglevelsofpovertyandinequality.Morethan fortyChurchleaderssignedanopenletterin2014critiquingthegovernment’swelfare reformsandinthe2015theecumenicalJointPublicIssuesTeam(representingtheMethodist Church,theBaptistChurch,theUnitedReformedChurch,theQuakersandtheChurchof Scotland)challengedthegovernmenttore-thinkitsausterityagenda(JointPublicIssues Team 2015).17

OurLifeontheBreadlinefieldworkillustratedtheongoingimportanceofChristian anti-poverty‘advocacy’,butalsoitsproblematicnature.Sinceits2019formationbyBen Lindsay,PowertheFighthasfocusedonthegrowingproblemofseriousyouthviolence inLondonthathasarisenfromtheinterconnectionofpre-existingpovertyanddeepcuts

toyouthandchildren’sserviceprovision.PowertheFighthasdrawnonanallianceof evangelicalandPentecostalchurchestosupportitsworkwithyoungpeopleimpacted byknifecrime,providecommunitybuildingtrainingandagitateforstructuralchange. Asaresult,PowertheFighthasbeenabletoadvocateonbehalfofsociallyexcluded youngpeople,theirfamiliesandcommunitiesaspartoftheMayorofLondon’sViolence ReductionUnit.

TheviewsthattheChurchleadersweinterviewedsharedabout‘advocacy’seemedto reflectthesizeofdifferentdenominationsandtheirlinkstotheStatemorethantheological disagreement.Aminorityexpressednervousnessabouttheroleoffaithgroupsinthe publicsphereandbeingperceivedas‘political’.AChurchofGodofProphecyBishop fromtheNorthofEnglandhighlightedthisproblem—“Ourtheology,whichfocuseslesson earthlymatters,contributestousnotfullygraspingtheissuesathand” (Survey2020).However, themostseniorWelshAnglicanleader,theArchbishopofWalestoldusthat,“TheChurch hasaduty ... tospeakuponbehalfofpeoplewhoareunjustlytreated ... Therewillalwaysbe thosewhosayit’snothingtodowithusbut,frankly,theyarewrong” (Interview2020).The Rt.RevPaulButler,BishopofDurham,illustratedthewayinwhichChurchofEngland Bishopscanexercisethisministryof‘advocacy’inParliamentbecausetheyareleaders oftheEstablishedChurch.ForBishopPaul,whospeaksonWelfareintheHouseof Lords,thishasenabledhimtoputhisbeliefthat “Jesuswasalwaysonthesideofthepoor” (Interview2020)intopracticebychallengingGovernmentMinisterstoreformUniversal Credit.DrNicolaBrady,GeneralSecretaryoftheIrishCouncilofChurches,reflecteda similarsentiment,suggestingthattheChurchhasaresponsibilitytopubliclychallenge “thestigma” surroundinghomelessnessand “giveleadershipinhighlightingstructuralissues andworkingforamorejustandcompassionatesociety” (Interview2020).

OtherChurchleadersdoubtedtheirabilitytoinfluencegovernmentausteritypolicies. Somesuggestedthattheirdenominationwastoosmallfortheirvoicetobeheard.The SeniorPastoroftheChurchoftheCherubimandSeraphim,PastorAdegoke,reflectedthis view—“ ... Smallerchurcheshavenovoice.Itisdifficultforustodemandprotestsoramarch toDowningStreet” (Interview2020).AsimilarperspectivewasexpressedbyJohnFulton, ModeratoroftheUnitedFreeChurchofScotland—“We’reasmalldenomination.Whyshould thegovernmentbebotheredaboutanythingthatcomesfromus?IftheChurchofEnglandorthe ChurchofScotlandmakeanoisethey’rebigenoughtohaveclout ” (Interview2020).Other Churchleadersarguedthatthe “governmentisnotinterestedintheviewsofordinarypeople, stilllesstheChurch” (regionalleader,ChurchofScotland,Interview2020).RevdAndrew Lunn,ChairoftheManchesterandStockportDistrictoftheMethodistChurch,expresseda similarview, “Thecurrentgovernmenttakeadoctrinaireapproachandseemunwillingtohear criticismorchallenge” (Survey2020).MostregionalChurchleadersspokeoftheimportance andeffectivenessofnetworkedsocialaction.AregionalleaderfromtheChurchofScotland recognisedtheprogressivepotentialoftheChurch’senduringsocialcapital—“UKchurches togetherhaveamembershiplargeenoughtoexertpressureongovernment” (Survey2020).A centralquestion,therefore,ishowtheChurchusesitssocialcapitalinrelationtoausterity poverty.ThesecommentsfromsomeofthenationalandregionalChurchleaderswespoke toduringLifeontheBreadlineexemplifybroaderhistoricandcontemporarydebatesabout theextenttowhichtheChurchshouldmovebeyondwelfare-basedresponsestopovertyto aproactiveengagementincivilsocietypoliticsintendedtofacilitatestructuralchange.

4.1.3.An‘Enterprise’ResponsetoPovertyintheUK

ThethirdapproachtoChristianengagementwithpovertythatwasrevealedduring LifeontheBreadlinerevolvesaroundsocialandbusinessenterprise.WefoundthisresponsetobemostcommonamongstevangelicalandPentecostalchurches.The‘enterprise’ approachischaracterisedbyanindividualisticself-helpethicwherebytheChurch’sroleis toempowerandenableindividualstodeveloptheircreativepotentialandbusinesstalents tobuildasocialorbusinessenterprise.LifeontheBreadlineresearcherRobertBeckford identified“arangeofenterpriseprojectswithinAfricanCaribbeanheritagechurches”

whichhavearisenfrom“economicresiliencetothedisproportionateimpactoffluctuations intheeconomiccycle”onBlackBritons(Beckfordetal. 2022,p.43).Beckfordcitestwoexamplesfromourfieldwork.First,henotestheworkofDrKarlGeorgeattheNewJerusalem ChurchinBirminghamwhich“promotesanenterpriseculturewithinthecongregation” thatisintendedto“buildfinancialresilienceandresourceamongstchurchmembers” (Beckfordetal. 2022,p.43).Second,BeckfordcitesthePentecostalCreditUnionwhichwas establishedbytheNewTestamentChurchofGodtoprovidepeoplewithanaffordable meansofsavingtheirwayoutofpovertyanddevelopingsmallbusinesseswithstart-up loans.Beckfordsuggeststhatbothexampleshaveenabledgreater“financialresilience” (Beckfordetal. 2022,p.43)withinmarginalisedcommunities.However,Beckfordnotes thatthe‘enterprise’approachcanalsobecritiquedasa“promotionofneo-liberaleconomic thought,which,ironically,hashadadverseconsequencesforBlackcommunitiesinBritain” (Beckfordetal. 2022,p.43).

OurcasestudywithInspireCentreinLevenshulme,Manchester,alsoincludedaspects ofan‘enterprise’approach.InspireCentreisasocialenterpriseandcommunitycentre establishedin2010withtheinvolvementofInspireChurch,aUnitedReformedChurch. Thechurchcontinuestobeinvolved,butstaffandvolunteersattheCentrearepeopleofany andnofaith.InspireCentrehostsavarietyofactivitiesincludingtheircafé whichserves cheap,nutritiousfoodandincudesapay-it-on-schemeforpeoplewhocannotaffordmeals orhotdrinks.EdCox,thefounderofInspireandMinisteratInspireChurchexplained theirapproach:

... aplacewherepeoplefromdifferentbackgroundscancometogetherinordertolive morewholelives ... it’saresponsetohowdowelivetogetherinaneighbourhood,rather thanhowarewegoingtohelppoorpeople.(Interview2020)

Theirapproachthereforeemphasisedwell-beingthrough‘enterprise’ratherthanpoverty language.Thisoverlapswiththe‘communitybuilding’approach,andcontraststhetopdownapproachesmorecommonlyfoundin‘caring’approachestopoverty.

4.1.4.A‘CommunityBuilding’ResponsetoPovertyintheUK

ThefinalapproachtoChristianengagementwithausterity-agepovertythatweidentifiedduringLifeontheBreadlinerevolvesaround‘communitybuilding’andself-sufficiency. Otherapproachestoengagingwithpovertycanfallpreytoatop-downmodelofsocial actionandtheadoptionofdecontextualisedexternalinterventions.The‘communitybuilding’approachischaracterisedbybottom-up,inside-outcommunitydevelopmentand,as RevdAlBarrettfromHodgeHillnoted,the “avoidanceofrescuerlanguage” (Interview2020). Thismeanssuchanapproachisnotalwayslabelledasa‘poverty’response.

Asset-BasedCommunityDevelopment(ABCD)exemplifiesthisapproachandwas usedbyourcasestudyofHodgeHillChurchandlocalresidentsinEastBirmingham.The originsofABCDarefoundintheworkofKretzmannandMcKnightintheUSA.Arising fromtheirresearchintocommunitybuildinginpoorneighbourhoods, Kretzmannand McKnight (1993)arguedforanewmodelofcommunitydevelopmentthatinvertedthe assumptionofdeficit-basedapproaches.ABCDbeginsbyidentifyingtheassetsalready presentinsociallyexcludedcommunities,arguingthatsustainablechangereliesonbottomuplong-termcommunitybuilding,ratherthantop-downshort-terminterventionsthatare premisedontheneedtosolveproblems.HodgeHill’sABCDapproachtoausterity-age povertyrevolvesaroundacommitmenttolong-termcommunitybuildingthatisinformed byanincarnationalecclesiologyofpresenceandsolidarityaswayofovercomingwhat vicarRevdDrAlBarrettcalled “adeficitinempathy” (Interview2020).Localresident Allannahexplained “Ibelieveinbuildingpeopleup” (Focusgroup,Interview2020).The FirsandBromfordestateinHodgeHillcouldbedepictedasa‘problem’neighbourhood— oneofthe10%mostmultiplydeprivedinEnglandandWales.18 However,theABCD adoptedbyHodgeHillChurchinitsStreetConnecting,OpenDoorCommunityandWorth Unlimitedchildren’sandyouthworkpaintsamoreholisticpictureofaneconomically poorneighbourhoodthatisresourcerichbecauseoftheassetsofpeople’sgifts,skillsand

experience(Denningetal. 2021). Russel (2016)suggeststhatABCDliberatesbecauseit beginswithwhatisstronginacommunity,ratherthanwhatiswrong.Localresident andvolunteerinHodgeHill,Sahra,suggestedthat: “peopleinthisareacannotdoenoughfor you” (Interview2020).HodgeHill’suseofABCDgaverisetoaninitiativecalledStreet Connectingwhichstrivestosubvertthenegativeself-imageoflocalpeoplethatresulted fromtheinternalisationofthestigmatisingnarrativethatdepictedtheneighbourhood inanegativelight—fullof“scroungers” and “theundeservingpoor”.Challengingwhat Barrettcalledthe “povertyofrelationships” andthe “povertyofidentity” (Interview2020) StreetConnectorsintroduceneighbourstoeachotherasafirststepinenhancingagency, fosteringapoliticsofempathyandasharedcommitmenttobuildingcommunity.Street ConnectorandlocalresidentClareexplainedthatshewantedto “lookatthegoodinthearea” (Focusgroup,Interview2020).ABCDseekstofosteramoreinclusivecommunitywithin whichasenseofthecommongoodisbuiltfromtheinside-out.

Asecondexampleofa‘communitybuilding’approachisdrawnfromChurchAction onPoverty.Aspartofitscommitmenttoenablingthedignity,agencyandpowerofpeople livinginpovertyChurchActionhassupportedthedevelopmentofsmallSelfReliant groupswhosemembersmeet,saveanddevelopideasforalocalsocialenterprise.This approachtoengagingwithpovertyaimstofosteranethicofsharingbyencouraging differentSelfReliantgroupstomeetoccasionallytosharegoodpractice.19

4.2.TheStrengthsandWeaknessesofResponsestoPovertyintheUK

LifeontheBreadlinerepresentsoneofthemostextensiveempiricalstudiesbyacademictheologiansofChristianengagementwithausterity-agepovertyintheUKsincethe 2008financialcrash.Wedonotclaimthattheapproacheswehavediscussedrepresent theonlyformsofChristianengagementwithausterity-agepoverty.Rather,ourfocus inthispaper,hasbeenonthoseapproachesthatwereevidentduringourLifeonthe Breadlineresearch.Aswenotedabove,theseapproachesshouldnotbeseenasfixed idealtypes,norshouldouranalysisbeviewedasaformaltypology.Theseapproaches overlap,convergeanddivergeovertime.Nevertheless,wesuggesttheyreflectdifferingtheological,ecclesiologicalandmissiologicalemphases.These‘caring’,‘campaigning andadvocacy’,‘enterprise’and‘communitybuilding’approachestopovertyareclearly identifiedwithinourcasestudiesandChurchleaders’interviewsandsurvey.Thispaper representsthefirstempiricallybasedtheologicalanalysisofthisbreadthofChristianengagementwithcontemporarypovertyandthecapacityoftheseapproachestotransform structuralinjustice.

BeforeexaminingthechallengesandopportunitiesfacingtheChurchasitresponds todeepeninglevelsofpoverty,wesummarisethestrengthsandweaknessesofexisting approaches.‘Caring’approachesaddressimmediateneedandreflectapoliticsofempathy andcommunitybuildingthatchallengestheculturalnarrativesdemonisingpeoplein poverty.However,whilstsuchperson-centredformsofChristiansocialactionfeedand clothemillionsofpeopleintheUK,thiswelfare-basedapproachdoesnothavethecapacity to‘transformstructuralinjustice’becauseofanabidingreluctancetoengageproactivelyand consistentlyinactivismintendedtostimulatestructuraleconomicchange.‘Campaigning’ approachesembodyGod’spreferentialoptionforthepoorandadeterminationtofulfil thecallingintheMarksofMissionto‘transformstructuralinjustice’.Aswenoted,this approach,oftencombinedwith‘advocacy,’representsaneffectivemeansofagitatingfor systemicchangessuchastheintroductionofareallivingwageorreformstoUniversal Credit.However,such‘campaigning’canreflectadisengagedtop-downmodelofactivism thatisdrivenbyactivistsorChurchleaders,ratherthanpeoplewithlivedexperience ofpoverty.Furthermorethis‘campaigning’approachcanneglecttheneedforcultural andspiritualchangetoaccompanysystemicreform.Wehavesuggestedthat‘advocacy’ hasprovedapowerfulmeansofspeakingtruthtopowerbyChurchleadersoverthelast decade.However,someofourparticipantshavearguedthattheadvocacyofChurch leaderscanreflectalackofeverydayengagementwiththerawrealitiesofausterity.It

canenergisethesupportersofnetworkssuchasChurchActiononPovertyandtheJoint PublicIssuesTeambutitcanalsobeanapproachnotavailabletosmallerdenominations thathavenotieswithestablishment.Wehavearguedthat‘enterprise’approachescan enablepeopletodevelopnewskillsandrealisetheirentrepreneurialpotential.However, thisapproachisoftenhighlyindividualised,liftingindividualsoutofpovertybutleaving structuralinjusticeuntouched.Finally,the‘communitybuilding’approachfostersgreater agency,empowerscommunitiesfromthebottom-up,challengestheperceivedneedfor external‘rescuers’andforgesadeeperrelationalpoliticsofempathy.However,unlessitis combinedwiththe‘campaigningandadvocacy’modelofaction‘communitybuilding’can lackthecapacitytogeneratewiderstructuralchange.

TheapproachestotheChristianengagementwithpovertythatweidentifiedduring LifeontheBreadlineallhavetheirstrengthsbutnoneengagesufficientlywiththewaysin whichpre-existinginequalitiesandsociallocationimpactonourexperienceofmultidimensionalpovertytohealthetraumaticdamageitwreaksand“transformstructuralinjustice”. AmoreintegratedChristianresponsetocontemporarypovertyisneededthatdrawsonthe strengthsoftheapproacheswehavedescribedinincreasinglyinterconnectedways.Only anapproachthatrecognisestheneedforconscientisation,individualempowerment,the immediatecareforpeopleinpovertyandaboldtranslationofacommitmenttoGod’sPreferentialOptionforthePoorfromChurchleadersintosustainedgrassrootsactionintended to‘transformstructuralinjustice’canbegintoforceausterity-agepovertyintoretreat.Life ontheBreadlinehasillustratedtheprogressivepotentialoftheChurch’senduringsocial capital.Sucharesource,aswehaveshown,hasimmenseliberativepotential.Thetime hascomefortherenewalofavisionofChristiancommunityasaninclusivegrassroots liberativemovementthatembodiesGod’spreferentialoptionforthepoorineveryaspect ofitslife.HowcanaChurcharisethatcanliveuptothiscommitment?

4.3.TheChurch’sMomentofTruth—ChallengesandOpportunities

Theterm‘costoflivingcrisis’runstheriskoftrivialisingdebilitatingpovertyand decouplingitfromsystemicpatternsofinequalityandstructuralinjustice.Whenaddedto thecombinedeffectsofadecadeoftraumatisingausterityandtheCOVID-19pandemic, 2022’s‘costoflivingcrisis’is,wesuggest,betterviewedascapitalism’sperfectstorm. ThisstructuralandexistentialcrisisrepresentsapivotalmomentfortheChurch.Wehave suggestedthattheChurchhasbeeninthefrontlineofresponsestodeepeningpoverty andinequalityduringthe‘AgeofAusterity’andarguedtheneedforanewconversation aboutecclesiology.WhatdoesitmeantobetheChurchinthefaceofdeep-seatedstructural injusticeandwhatformshouldChristiansocialactionwhenthecommongoodisconsistentlyundermined?Inrespondingtothesequestions,theChurchneedstoengagewith fourchallengesdrawnfromourLifeontheBreadlineresearchasitre-imaginesChristian communityatthiscriticalmoment.

First,theChurchretainsadeepreservoiroflocalisedsocialcapitalinneighbourhoods acrosstheUK.SoonafterHitlerrosetopowerin1933DietrichBonhoefferaskedwhether theChurchshouldbecontentto“bandageupthewoundsofthebrokenbeneaththewheels ofinjustice”orbewillingtoram“aspokeintothewheelitself”(Bethge 1995,pp.316–17). OurresearchposesasimilarchallengetotheChurchinitsresponsetoausterity-agepoverty. Shapedbyanegalitarianvisionofthecommongoodthatispremisedontheteachingof JesusandtheHebrewProphets,istheChurchreadytoram“aspoke”intothe“wheel”of structuralinjusticeorwillitbecontentto“bandageupthewounds”ofthosetraumatised byausterity-agepoverty?Whilstwehaveidentifiedexamplesofanti-povertyactivism thatembodyGod’spreferentialoptionforthepoor,ourresearchhighlightsanongoing nervousnessonthepartofmanyChurchleadersabouttheuseoftheChurch’ssocialcapital to‘transformstructuralinjustice’.

Second,ourresearchsuggeststhatwhilstpovertyismultidimensionalandourexperienceofitisinterconnected,theChurch’sresponseisoftenone-dimensionalasaBaptist MinisterfromYorkshireimplied—“Povertyiscomplex ... [but]mostchurches ... lackabigger

pictureoftheinfluencesandchangeswhichaffectpoverty” (Survey2020).Theologicalanalyses ofcontemporarypovertyhaveoftenfocusedexclusivelyonfoodpoverty,therebyignoring theinterrelationofotheraspectsofmarginalisationsuchasfuelpoverty,homelessness,low pay,periodpoverty,personaldebtandpoorhousing.However,wehaveshowntheneed foranunderstandingofthemultidimensionalnatureofpovertythatresonatesinausterity ageBritainwheregovernmentpolicyhascompoundedtheeffectsofmultiplepre-existing formsofmarginalisationandinequality.Thispaperarguesthatonlyaninterconnected responsetoausteritycanresourcemodelsofChristianactivismthathavethepotentialto defeatthemultidimensionalviolenceofpoverty.InourLifeontheBreadlineinterviews, theRt.RevdPaulButler,theAnglicanBishopofDurham(Interview2020),NicolaJones (Interview2020)oftheIrishCouncilofChurches,MartinCharlesworth(Interview2020) ofJubileePlusandRevdMickyYoungson(Interview2020),theformerPresidentofthe BritishMethodistConferenceallacknowledgedthattheChurchneedstoadoptsucha mindsetifitistoaddressthemultidimensionaldamagecausedbysystemicpoverty.B30 Foodbankillustratestheneedtocultivateamatrixmindset,policyagendaandtheological methodology.ThecorepurposeofB30istorespondtothescourgeoffoodpovertyand insecurity.However,volunteersrecognisedthedangerofrespondingtofoodpovertyin isolationfromotherformsofsocialexclusion.Whenclientsvisitthefoodbank,theyreceive adviceandsignpostinginrelationtohousing,legalmatters,benefitsandfuelpoverty. WhilstB30Foodbankcannotmeetalloftheseneedsthereisarecognitionthatathree-day foodparcelisoflimitedvalueiftheclientcannotheatthefoodbecausetheyarenotableto paytheirgasbillandthatfuelpovertycanbeworsenedinpoorqualityhousing,whichin turncandamagephysicalandmentalhealth.

Third,LifeontheBreadlinehighlightedthetensionbetweentheChurch’scommitment toanegalitarianvisionofthecommongoodandalackofeverydayengagementwiththe traumaticrealitiesofausterity-agepoverty.OurB30casestudyrevealsthesenseofstolen potentialandrepressedshameofdependingonfoodparcels.StuartwasaclientatB30 andsummarisedinarticulateterms—“Povertyaffectspeople’smoods.Everybodyseemstobe miserable,depressed,anxious,worried,alotofdebt,strugglingforfoodand thebasicsoflife” (Interview2019).OurHodgeHillcasestudyexemplifiestheculturalviolencetowhich Galtung (1990)points.AsRevdAlBarrettnoted,theneighbourhoodfeltlikeaforgotten estateformanyyearsandwasdismissedinpejorativeterms.Suchdisempoweringcultural violencerobbedlocalpeopleoftheirsenseofself-worthbystigmatisingtheFirsand Bromfordestate.Thelong-termABCDofHodgeHillChurchandthesolidarityofNotting HillMethodistChurchwiththetraumaoftheGrenfellTowerfireexemplifyanengaged long-termbottom-upmodelofChristiansocialactionthatthatisrootedintherawrealities ofausterityagepoverty.Despitethis,oursurveyandinterviewsofnationalChurchleaders suggestthat,whilstlocalchurchesarekeentosupportpeoplelivinginpoverty,theyare oftendisengagedfromtheeverydayrealitiesofausterity.AChurchofScotlandsurvey respondentsummarised, “Christianscarebut ... areisolatedfromtheworsteffectsofextreme poverty” (Survey2020).RevdMickyYoungson,theformerPresidentoftheBritishMethodist Conference,toldusthat “Theproblemiswe’relessincommunitiesofabjectneedthanwearein morecomfortablecommunities” (Interview2020).TheBishopofDurhamnotedthat “Partof thestarkrealityofausterityisthatthoseofuswhoareonmiddleorhigherincomeshavehardly noticed” (Interview2020)andaUnitedReformedChurchsurveyrespondentfromtheSouth ofEnglandsuggestedthat “ onaveragecongregationalmembersarerelativelycomfortableand tendtoseetheissuesasmorepersonalthanstructural” (Survey2020).Thechallengeofengaged activismrelatestothreemodesofChristiansocialaction,eachofwhicharticulatestheneed forchangeeventhoughtheprocessandnatureofculturaltransformationisenvisagedin significantlydifferentterms.First,thereisaninstitutionalisedmodelofChurchandthe strategictop-downinterventionsandthe‘advocacy’ofnationalChurchleadersthatwe pointedtoabove.Thisapproachreflectsadistancefromeverydayausterity,awell-meaning butdisengagedecclesiologyandthekindofoutsider “rescuerlanguage” thatRevdAlBarrett fromHodgeHillChurchbemoaned(Interview2020).Second,wenotedacontrasting

bottom-upapproachwhichreflectedanecclesiologycharacterisedbydeep-seatedlongtermengagementwiththeeverydayrealitiesofausterity-agepoverty.InHodgeHillthis wasevidencedinauseofABCDandinNottingHillinrelationtosolidaritywithpeople traumatisedbytheGrenfellTowerfireandongoinghousinginjustice.Third,weuncovered ahybridmodelofChurchthatcombinedelementsoftop-downandbottom-upapproaches withinafluidandgeographicallydispersednetworkmotivatedbyacommoncommitment totheassertionthatinastructurallyunjustsocietyGodnecessarilyhasaPreferential OptiontothePoor.SuchanapproachenvisionsChurchasafluidsocialmovementrather thanasolidinstitution.TheworkofChurchActiononPovertycasestudyexemplifies thisapproach.

Fourth,ourresearchhighlightedanambivalenttensionwithinChristianresponses topoverty.AlmostalloftheregionalandnationalChurchleaderswhomweinterviewed suggestedthatchallengingpovertyrepresentsacoreGospelvalue.However,formost, thisstoppedshortofthesustaineddenunciationofinequalityandinjusticewithinthe teachingoftheHebrewProphetsandtheministryofJesus.AMethodistleaderfrom theNorthofEnglandarguedthat,whilstthenationalChurchhascommitteditselfto ‘transformstructuralinjustice’,withinmanylocalcongregations “Thereisasensethatit isstilltheindividual’sfaultiftheyarepoor” (Survey2020).Wehaveshownthatthereisa needtomovebeyondawelfare-based‘caring’modelofChristiansocialactionthatfailsto ‘campaign’forsystemiceconomicchangetoreflectGod’spreferentialoptionforthepoor. LifeontheBreadlinehasshonealightontheimmensevalueofChristianengagementwith austerityagepovertybutinthispaperwehavearguedthattheChurchneedstopoliticise itsempatheticsocialactionandmovebeyondatheologyofgoodintentions.RevdMicky Youngson,pinpointedthechallenge: “There’satheologicalgapbetweenlovingmyneighbour andchallengingCaesar” (Interview2020).NowisthetimefortheChurchtoovercomeits nervousnessandchallengeCaesar.

5.Conclusions

InthispaperwehavedrawnonqualitativedatafromourLifeontheBreadline research,aswellasamultidisciplinaryrangeoftheologicalandsocialscienceliteratureto analyseChristianresponsestotherupturingofthesocialfabricofBritishsocietyduring the‘AgeofAusterity’.OuranalysisemergesfromfieldworkintheUKbutcanprovide practitionersandpolicymakersindifferentbutcomparablecontextswiththreevaluable insights.Wehavearguedthatthedepthofcontemporarypovertyandsystemicinjustice fromthe‘AgeofAusterity’,COVID-19impoverishmentandtheongoing‘costofliving crisis’whensetalongsidetheChurch’senduringsocialcapitalintheUKplacesusata watershedmoment.Indoingsowehaveconsideredthreequestionsthatneedtoshapethe Church’sresponsetothischallenge.

First,wasausterityapoliticalchoiceoraneconomicnecessityandwastheburdenof austerityborneequally?Wehavearguedthatausteritywasapoliticalchoiceratherthan aneconomicnecessity.Austeritypolicieshavedeepenedpovertyandincreasedinequality overthelastdecade.ThisbecameabundantlyclearduringLifeontheBreadline.In ourprojectsurveymostoftheregionalChurchleadersfromEngland,NorthernIreland, ScotlandandWalessuggestedthatausteritypolicieshadbeentargetedprimarilyatpeople andcommunitieswhowerealreadysociallyexcluded.RevdDrRichardFraserfromthe ChurchofScotlandsuggested: “thepoorestinsocietyhave hadtopayforthemisdemeanours ofthoseinpower” (Interview2020).OurGrenfellTower,B30Foodbank,HodgeHillChurch andPowertheFightcasestudieshavehighlightedthetraumaticdamage,economicand existentialinsecurity,debilitatingstigmaandexclusionfromcivilsocietythatausterity policieshavecausedoverthelastdecade.AB30Foodbankclientmadethepointclearly, “Peoplearekillingthemselvesyouknowbab I’vecontemplatedit.Whystrugglelikethisfor anotherten,fifteenyears?” (Samantha,Interview2019).Contrarytopoliticalassertionsand theteachingwithinsomeconservativeevangelicalChristiantraditions,povertyiscaused bysystemicinjusticeandnotindividualfailings.

Second,whatstepsneedtobetakentodevelopmoreholisticandmultifacetedunderstandingsofausterity-agepoverty?Inthispaperwehavecritiquedthetendencywithin governmentpolicy,Church-basedsocialactionandtheologytorespondtopovertyin reductionistterms.Wehavedemonstratedthatsuchapproachesfailtograspthemultidimensionalandinterwovennatureofausterityagepoverty,andarguedthatunderstanding ofpovertyasaformofdirect,culturalandstructuralviolencecanfostermoreeffective actionandanalysis.Wehaveshownthatitwillonlybepossibletodevelopamoreholistic understandingthatcanresourcetheworkofallwhoseekto‘transformstructuralinjustice’ ifwegraspandengagewithourinterconnectedexperienceofmultidimensionalpoverty.

Finally,whatimplicationsdoesausterityhavefortheself-understandingandpractice oftheChurchandwhatformshouldChristiansocialactiontakewhenthecommongood isconsistentlyunderminedbygovernment?DuringLifeontheBreadline,weidentified fourbroadoverlappingChristianresponsestoausterity-agepoverty.Thispaperbrings theseapproachestogetherwithinamatrixofChristiananti-povertyactionforthefirst time,enablingthemostholisticfieldwork-ledanalysistodatebytheologiansintheUK. Wehavediscussedthetheologicalfoundationsandimpactof‘caring’,‘campaigningand advocacy’,‘enterprise’and‘communitybuilding’modelsofChristiansocialactionand shownhowtheseapproachescanshiftandconvergeovertime.Wehavearguedthatno singleapproachcanresourcethekindofintegratedChristiansocialactionneededtoheal thedamagedonebymultidimensionalpoverty.Inclosing,wemakefoursuggestions. First,theChurchneedstocommititselftocollaborativeandsustainedactioninthepublic spherethatisexplicitlyaimedattransforming“structuralinjustice”.Onlybyovercoming itsnervousnessaboutpoliticalactionwilltheChurchrealisethefullliberativepotential thatisembeddedinitsextensivesocialcapital.Second,todothisthereisaneedto movebeyondthecurrentwelfare-basedmodelofChristiansocialactiontoassertaclear PreferentialOptionforthePoorastheonlycrediblebasisforagenuinelyegalitarian visionofthecommongoodinthefaceofstructuralinjustice.Third,suchre-imagined ChristiansocialactionneedstoberootedinarenewedvisionofChristiancommunity. TheChurchneedstobecomeafluidsocialmovementthatisdeeplyengagedwiththe everydayrealitiesofstructuralinjustice,ratherthanacaringbutdisengagedinstitution thatstrugglestoshakeitselffreefromahierarchicalmodeloforganisationandpractice. Fourth,iftheChurchistoplayakeyroleinbeating-backausteritypovertyitneedsto becharacterisedbyacommitmenttoenhancingtheagencyofthosewhohavebeensidelinedordisempowered.Avital,butoftenoverlooked,steponthisjourneyrelatestothe existentialdamagecausedbypoliticalortheologicalnarrativesthatdemeanpeoplelivingin poverty,blamingtheirmarginalisationontheirowninadequacyorlackoffaithratherthan systemicinjustice.TheChurchneedstochallengesuchtraumatisingculturalviolenceand reinforcethecentralChristianbeliefthatallpeopleareofequalworthbecauseeveryperson ismadeintheimageofthesameGod.Suchaprocessofconscientisationisanessential firstactinthebattletodefeatthehegemonicjustificationofausterity-agepovertyand ‘transformstructuralinjustice’.Povertyismultidimensional.Onlyamultifacetedresponse bytheChurchcanmeetsuchcomplexity.Thetraumatisingviolenceofpovertydamages individualsandcommunities.Consequently,theChurch’sresponsemusttakemultiple forms,addressingindividualneed(pastorallysensitivecaringresponsestoimmediate need,empoweringindividualsandenablingenterprise)andcommunal(campaigning, advocacyandcommunitybuilding).Aboveall,theChurch’sresponsetocontemporary povertymustbegroundedthefundamentalvaluesofliberationtheologyandactively embodyacommitmenttoGod’spreferentialoptionforthepoorandmarginalised.Thisis amomentoftruthfortheChurchinbreadlineBritain.Nowisthetimeforaction.

AuthorContributions: Conceptualization,C.S.andS.D.;methodology,C.S.andS.D.;formalanalysis, C.S.andS.D.;investigation,S.D.;writing—originaldraft,C.S.andS.D.;writing—reviewandediting, C.S.andS.D.;visualization,S.D.;projectadministration,C.S.;fundingacquisition,C.S.Allauthors havereadandagreedtothepublishedversionofthemanuscript.

Funding: ThisresearchwasfundedbytheEconomicandSocialResearchCouncil,grantnumber ES/R006555/1.

InstitutionalReviewBoardStatement: TheLifeontheBreadlineresearchprojectwasconducted inaccordancewiththeDeclarationofHelsinki,andapprovedbytheResearchEthicsCommitteeof CoventryUniversity(protocolcodeP47441anddateofapproval:13August2019).

InformedConsentStatement: AllLifeontheBreadlineparticipantsgavetheinformedconsentfor quotationsfromtheirinterviewsorsurveyresponsestobeusedinpublicationsarisingfromthe project.Participantswhoarenamedgavetheirwrittenpermission.

DataAvailabilityStatement: FurtherdetailsabouttheLifeontheBreadlineprojectuponwhichthis paperisbasedcanbefoundat https://breadlineresearch.coventry.ac.uk,accessed26July2022.

Acknowledgments: Whilstthispaperwaswrittensolelybytheauthors,werecogniseandacknowledgethecolleagueshiporourLifeontheBreadlineCo-Investigators,RobertBeckfordandPeterScott. ConflictsofInterest: Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictofinterest.

Notes

1 Furtherdetailsthe2018–2021‘LifeontheBreadline’researchproject,whichwasfundedbytheEconomicandSocialResearch Councilcanbefoundat https://breadlineresearch.coventry.ac.uk accessed1December2018.

2 Wintour,P.2April2013,‘WelfareReforms:Wewillmakeworkpay,saysGeorgeOsborne’. TheGuardian, https://www. theguardian.com/politics/2013/apr/02/george-osborne-work-welfare-tax,accessed13July2021.

3 PhillipHammond,EvidencetotheTreasuryCommittee,HouseofCommons,5November2018, http://data.parliament. uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/treasury-committee/budget-2018/oral/92275.html,accessed 1May2021.

4 DeborahSummers,26April2009.DavidCameronWarnsofNew’AgeofAusterity’, TheGuardian https://www.theguardian. com/politics/2009/apr/26/david-cameron-conservative-economic-policy1,accessed26July2022.

5 Website https://foodfoundation.org.uk/press-release/millions-adults-missing-meals-cost-living-crisis-bites,accessed16June2022.

6 DanSabbaghandPhillipInman.29October2018.‘Hammondsaysendofausterityisinsight’, TheGuardian https://www. theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/oct/29/hammond-claims-hard-work-paid-off-end-of-austerity-in-sight-budget,accessed 20June2022andDearbailJordan.4September2019.‘ChancellorSajidJaviddeclaresendofausterity.’BBCNews, https: //www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-49577250,accessed20June2022.

7 MillionsofPeopleturntoFoodbanksinlatestevidenceoffoodinsecurity,29July2021, https://www.trusselltrust.org/2021/07/ 29/millions-of-people-turn-to-food-banks-in-latest-evidence-of-food-insecurity/,accessed29July2021.

8 Allfieldworkparticipantsandintervieweeswhosenamesareusedgavetheirexplicitconsenttobenamed.

9 (Interview2019/2020)and(Survey2020)inthefollowingtextrefertotheinterviewsandsurveysperformedintheLifeonthe Breadlineresearchindifferentyears.

10 NicholasWatt,20February2014.‘BishopsBlameDavidCameronforFoodbankCrisis’, TheGuardian, https://www.theguardian. com/politics/2014/feb/20/bishops-blame-cameron-food-bank-crisis,accessed22June2022.

11 EasterSermonofArchbishopofCanterbury,20April2014, https://anglican.ink/2014/04/20/easter-sermon-of-the-archbishopof-canterbury-2/,accessed22June2022.

12 See https://www.trusselltrust.org/what-we-do/research-advocacy/,accessed23June2022.

13 https://www.methodist.org.uk/about-us/the-methodist-church/our-calling/,accessed26July2022.

14 https://ctbi.org.uk/ and https://www.churchofscotland.org.uk/about-us/the-faith-action-plan,accessed26July2022.