Socio-EconomicReview(2008) 6,703–731

AdvanceAccesspublicationAugust26,2008

Socio-EconomicReview(2008) 6,703–731

AdvanceAccesspublicationAugust26,2008

doi:10.1093/ser/mwn016

MaxWeberProgramme,EuropeanUniversityInstitute(EUI),VillaLaFonte,SanDomenicodiFiesole,Italy

Correspondence:stephanie.mudge@eui.eu;stephaniemudge@gmail.com

Neo-liberalismisanoft-invokedbutill-definedconceptinthesocialsciences.This articleconceptualizesneo-liberalismasa suigeneris ideologicalsystembornof struggleandcollaborationinthreeworlds:intellectual,bureaucraticandpolitical. Emphasizingneo-liberalism’sthird‘face’,itarguesthatafailuretograspneo-liberalismasapoliticalformimposestwolimitationsonunderstandingitseffects:(i) fosteringanimplicitassumptionthatEuropeanpoliticalelitesare‘naturally’ opposedtotheimplementationofneo-liberalpolicies;and(ii)tendingtopreemptinquiryintoanunsettlingfact—namely,thatthemosteffectiveadvocates ofpoliciesunderstoodasneo-liberalinWesternEurope(andbeyond)have oftenbeeneliteswhoaresympatheticto,orarerepresentativesof,theleft andcentre-left.Giventhatsocialdemocraticpoliticswereuniquelypowerfulin WesternEuropeformuchofthepost-warperiod,neo-liberalismwithinthemainstreampartiesoftheEuropeanleftdeservesparticularattention.

Keywords: liberalism,neo-liberalism,economicthought,institutionalism, politicaleconomy

JELclassification: A14sociologyofeconomics,B2historyofeconomicthought since1925,F59internationalrelationsandinternationalpoliticaleconomy

Inthe1990s,politicalobserversbegantonotethedemise,forbetterorforworse, ofpoliticsasweknewit.InthewordsofCrouch(1997,p.352),themainstream partiesoftheleftcametolive‘inapoliticalworldwhichisnotoftheir making’1—aworldwhoseverystructureisantitheticaltothegoalsandprinciples ofsocialdemocracy.Agrowingsociologicalliteraturetracesaninternationalturn towardsfreemarketsfromthe1970s,placingparticularemphasisontheproductionandexportofthe‘Washingtonconsensus’fromNorthtoCentraland

1 CrouchrefersheretotheBritishNewLabourvictoryin1997,comparingitwithChurchill’s Conservatives’victoryin1951.

# TheAuthor2008.PublishedbyOxfordUniversityPressandtheSocietyfortheAdvancementofSocio-Economics. Allrightsreserved.ForPermissions,pleaseemail:journals.permissions@oxfordjournals.org.

SouthAmerica(CampbellandPedersen,2001;DezalayandGarth,2002; Fourcade-GourinchasandBabb,2002;Babb,2004;Massey etal.,2006).Focusing ontheWest,specialistsincomparativepoliticscitethedeclineofpartisanidentitieswithintheelectoratesofrichdemocracies,theriseofprofessionalpolitical partiesthatdonotadhereto‘old’ideologicaldivides,andthewaningsignificance ofpartisangovernmentasapredictorofmacroeconomicpolicychoices(Boix, 2000;DaltonandWattenberg,2002;Fiorina,2002).2 Meanwhile,asyntheticliteraturedrawingfromthe‘institutionalisms’ineconomics,politicalscienceand sociologyemphasizestheglobalspreadofideasasacentralexplanatoryfactor behindthediffusionof(neo)liberalpolicies(Henisz etal.,2005;Dobbin etal., 2007;QuinnandToyoda,2007).

Thesestrandsofanalysisstrikeacommonchord:theemergenceofanewlandscapeinwhichfamiliarpoliticalcategorieshaveshiftingmeaningsandpartisanshiphasunpredictablepolicyimplications.Howdowemakesenseof‘old’ politicalcategoriesinaneo-liberalage?Thisarticlecontributestothescholarship onthisquestionbydevelopingahistoricallygrounded,tripartiteconceptofneoliberalism:asanintellectual–professionalproject,arepertoireofpoliciesanda formofpolitics.Addressingaconceptualgapintheexistingliterature,Ifocus specificallyonneo-liberalism’spoliticalface.

Thearticlemakesthreemainarguments.First,neo-liberalismisa suigeneris ideologicalsystembornofhistoricalprocessesofstruggleandcollaborationinthree worlds:intellectual,bureaucraticandpolitical.Neo-liberalism,inotherwords, hasthreeinterconnected‘faces’:

(i)Neo-liberalism’s intellectualface isdistinguishedby(a)itsAnglo-Americananchoredtransnationality;(b)itshistoricalgestationwithintheinstitutions ofwelfarecapitalismandtheColdWardivideand(c)anunadulterated emphasisonthe(disembedded)marketasthesourceandarbiterof humanfreedoms.

(ii)Its bureaucraticface isexpressedinstatepolicy:liberalization,deregulation, privatization,depoliticizationandmonetarism.Thisfamilyofreformsis targetedatpromotingunfetteredcompetitionbygettingthestateoutof thebusinessesofownershipandgettingpoliticiansoutofthebusinessof dirigiste-styleeconomicmanagement.Neoliberalpoliciesalsoaimto‘desacralize’institutionsthathadformerlybeenprotectedfromtheforcesof privatemarketcompetition,suchaseducationandhealthcare.

2 Thepersistenceofpartisanship’sdeclineisamatterofdispute(Hetherington,2001).

(iii)Its politicalface isanewmarket-centric‘politics’—strugglesoverpolitical authoritythatshareaparticularideologicalcentreor,inotherwords,are underpinnedbyanunquestioned‘commonsense’.Ontheelitelevel,3 neoliberalpoliticsisboundedbycertainnotionsaboutthestate’sresponsibilities(tounleashmarketforceswhereverpossible)andthelocusofstate authority(tolimitthereachofpoliticaldecision-making).Theyalso tendtobeorientedtowardscertainconstituencies(business,financeand white-collarprofessionals)overothers(tradeunions,especially).

Second,Iarguethatafailuretograspneo-liberalism’sintersectionwithpoliticsimposesseriouslimitationsonasocialscientificgraspofitseffects.Thethree facesofneo-liberalismshareacommonanddistinctiveideologicalcore:the elevationofthemarket—understoodasanon-political,non-cultural,machinelikeentity—overallothermodesoforganization.Neo-liberalisminthisdistinctiveformwasarticulatedintheintellectualfieldlongagobutwasdiscredited duringtheWorldWars;itre-emergedinmainstreamintellectualandpolitical lifesincethe1970swithlittleregardfor‘old’partydistinctionsornational boundaries.

Thethirdargumentextendsfromthesecond:atendencytofocusonpolitics inAnglo-liberalcountriesorstrictlywithintheranksofthepoliticalrightlikely missesmostofthe‘action’.Theneo-liberalerawasbornfromaprevioushegemonicageinwhichpoliticswereboundedbywelfarist,statistandKeynesiansystems ofthought:whatcouldbetermed‘socialdemocraticpolitics’.Thispriorpolitical formwasparticularlydominantinWesternEurope,givingrisetosomeofthe mostextensivewelfareinstitutionstheworldhasknown.Giventheirhistorical startingpointasthebeatingheartofsocialdemocraticpolitics,neo-liberalism inthepoliticsofthemainstreampartiesoftheEuropeanleftdeservesspecial attention.

Neo-liberalismisanoft-usedtermthatcanmeanmanydifferentthings.For CampbellandPedersen(2001)neo-liberalismis:

[A]heterogeneoussetofinstitutionsconsistingofvariousideas,social andeconomicpolicies,andwaysoforganizingpoliticalandeconomic activity .Ideally,itincludes formalinstitutions,suchasminimalist welfare-state,taxation,andbusinessregulationprograms;flexible

3 Althoughthisdiscussionfocusesonpoliticalelites,neo-liberalpoliticsfeaturesamuchbroaderarray ofactors—interestgroups,grassrootsorganizations,non-partypoliticalorganizations,andsoforth— operatingonlocal,nationalandinternationallevels(Evans,2005;Prasad,2006;Martin,2008).

labormarketsanddecentralizedcapital–laborrelationsunencumbered bystrongunionsandcollectivebargaining;andtheabsenceofbarriers tointernationalcapitalmobility.Itincludesinstitutionalized normative principles favoringfree-marketsolutionstoeconomicproblems,rather thanbargainingorindicativeplanning,andadedicationtocontrolling inflationevenattheexpenseoffullemployment.Itincludesinstitutionalized cognitiveprinciples,notablyadeep,taken-for-grantedbeliefin neoclassicaleconomics.(CampbellandPederson,2001,p.5,emphasis added)

Theinstitutionalistdefinitionofneo-liberalismprovidesausefulstartingpoint, butitlackshistoricityandparsimony.Athoroughdefinitionshouldidentify neo-liberalisminhistoricalterms,specifyingitsoriginsandhighlightingwhat differentiatesitfromitsantecedents.Whatsitsatneo-liberalism’score?

AddingahistoricalbasistoCampbellandPedersen’sdefinition,neo-liberalism isdefinedhereas anideologicalsystemthatholdsthe‘market’sacred,bornwithin the‘human’orsocialsciencesandrefinedinanetworkofAnglo-American-centric knowledgeproducers,expressedindifferentwayswithintheinstitutionsofthe postwarnation-stateandtheirpoliticalfields (Bourdieu,1992,1994,2005; BourdieuandWacquant,1992).Neo-liberalismisrootedinamoralproject, articulatedinthelanguageofeconomics,thatpraises‘themoralbenefitsof marketsociety’andidentifies‘marketsasanecessaryconditionforfreedomin otheraspectsoflife’(FourcadeandHealy,2007,p.287).ThisconceptionofneoliberalismfitssquarelywithDurkheimianperspectivesthattreatmarket-making asaprocessbywhich‘moralcategories’—thatis,thesacredandtheprofane—‘are formed,contested,andtransformed’(FourcadeandHealy,2007,p.301).4 As Durkheim(2001[1912])argued,itispreciselybecauseofan‘essentiallyreligious faith’insciencethatitsconcepts—inthiscase,thenotionofafree-standing,apolitical,machine-like‘market’—exertmoralforce(2001[1912],pp.208,439).

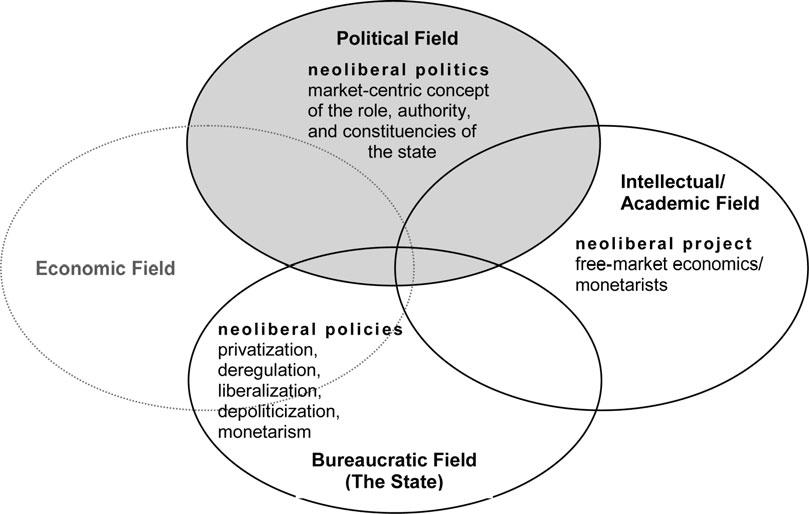

Thedefinitionalsohighlightsthefactthatneo-liberalismhasdistinctive modesandexpressions.ItexistsasanAnglo-centricintellectual–professional projectofprimarilyeconomicacademicandnon-academicknowledgeproducers andother‘newclass’actors(KingandSzele ´ nyi,2004),asetofpoliciesextended viathebureaucraciesoftheformerwelfarestateandasetofmarket-centricpoliticalorientationsthatstructurestherhetoricalparametersofpoliticalcontest (Figure1).

Inallitsmodes,neo-liberalismisbuiltonasingle,fundamentalprinciple: thesuperiorityofindividualized,market-basedcompetitionoverothermodes

4 Oneconomicsasmoralphilosophyandtheology,seeHausmanandMcPherson(2006)andNelson (2001).

Mudge:whatisneo-liberalism?707

oforganization.Thisbasicprincipleisthehallmarkofneo-liberalthought—one witholdrootsthatlaypartlyinAngloeconomicsandpartlyinGermanschoolsof liberalism.

Thisarticledelineatesneo-liberalism’sthreefaceswithanemphasisonthe third:neo-liberalpolitics.DrawingfromBourdieu’snotionofthepolitical field,theterm‘politics’denotesaparticularkindofsocialterrain:abounded spaceofstruggleoverpoliticalpowerthatisstructuredbyrulesofaccess, whereresourcesaredifferentiallydistributedamongplayersandthesetoflegitimatepositionsonquestionsofgovernmentisconstrained—thatis,somepoliticalpositionsarebeyondtheboundariesoflegitimatediscourseinanygiventime andplace.Forthisreason,theworldofpoliticalpossibilitiesisonlypartially subjecttopoliticalactors’manipulation.Inpolitics,then,themostinfluential kindofpowerisdefinitional:thosewiththeabilitytodefinepoliticalproblems andtherangeofpossiblesolutionsexertauniqueinfluence.

Thisdoesnotmeanthatpoliticalactorsexertdefinitionalauthorityspontaneously.Neo-liberalpoliticsexpressesasystemofthoughtthatoriginated outsideofpolitics.5 Inotherwords,politicalelitesmaywellexertpowersofdefinitionbydrawing—consciouslyornot—onideologicalsystemsarticulatedin non-politicalspaces.

5 Myargumentthatsymbolicresourcesareoftenproducedoutsideofthepoliticalfieldcontrastswith theinstitutionalistperspectivethattheconstellationofinstitutions,actorsandorganizationsthat makeupapoliticalfieldconstitutesthemainbreedinggroundforsymbolicresources(‘cultural frames’;Stone-SweetandSandholtz,1999;Stone-Sweet etal.,2001).

Figure1 Neo-liberalism’sthreefaces.Asanintellectual–professionalproject,neo-liberalismis‘neo’inthreesenses: (i)itssimultaneoustransnationalityandanchoringinAnglo-Americanacademe; (ii)itshistoricallyspecificgestationwithinwelfarecapitalismandtheCold Wardivide(thatis,asaresponsetotheemergenceofwelfarecapitalisminthe North,ahegemonicsocialdemocraticdiscourseandpoliticalandintellectualdivisionsproducedbytheColdWar;Esping-Andersen,1990;LemkeandMarks, 1992;Sassoon,1996,1997;BockmanandEyal,2002;Bockman,2007;Therborn, 2007)and(iii)itsunadulteratedemphasisonthemarketasthesourceandarbiter ofrights,rewardsandfreedoms—and,byextension,itsmarkeddisdainfor politics,bureaucraciesandthewelfariststate.

Neo-liberalism’sintellectual‘face’isremarkableinpartforitstrans-and supra-nationality—thatis,itslociinactivitiesandorganizationalformsthat laybeyondtheboundariesofthenation-state—andforitsgeographicalanchoringwithinAnglo-Americanacademe.Asubstantial‘hegemonicproject’literature emphasizestransnationalnetworksofactivistsandfree-marketthinktanks, right-wingpoliticalelitesandtheChicago-basedfree-marketbranchof Anglo-Americaneconomicsaskeyforcesbehindneo-liberalism’sascendance (Smith,1993;Cockett,1995;Valdes,1995;Kelly,1997;BourdieuandWacquant, 1999;Weyland,1999;BockmanandEyal,2002;DezalayandGarth,2002;Babb, 2004;Kay,2007;Power,2005).7 Thesearetheactorsthataremosteasilyunderstood,incertainterms,as‘neoliberals’.

Inadditiontoengagingindirectpoliticalaction,neo-liberalintellectualsprovidedsymbolicresourcestopoliticalelitesintheformofexplanationsforthefailuresofKeynesiananddevelopmentalpoliciesandanewsetofrecommendations foreconomicrecovery.Theseresourcesweredeployedtovaryingeffectvia governmentsandorganizationsthatwerewellsituatedtoexertcoerciveandnormativepressuresataninternationallevel:theAmericangovernment(orrich

6 Ipair‘intellectual’with‘professional’heretohighlightthefactthatintellectualsarenotmerely purveyorsofparticularepistemes;theyarealsoembeddedindisciplinaryprofessions,whichhave interestsandcompetitivedynamicsoftheirown(Abbott,1988;DezalayandGarth,2002).

7 Someoftheseworksdrawonfieldtheory—whichischaracterized,amongotherthings,byanexplicit rejectionofmechanistic,‘pinball’formsofexplanation(Martin,2003).Fieldtheory‘purportsto explainchangesinthestatesofsomeelements[ ]butneednotappealtochangesinstatesof otherelements(i.e.,“causes”)’,wherechangeisnotproducedbecauseofobjects‘whamminginto oneanother’butratherbecauseof‘aninteractionbetweenthefieldandtheexistingstatesofthe elements’(2003,pp.4,7).

‘core’countriesingeneral),theOECD,theEuropeanUnion,theInternational MonetaryFund(IMF)andtheWorldBank(DezalayandGarth,2002; Hanley etal.,2002;Stiglitz,2002;Massey etal.,2006;Dobbin etal.,2007).8

Neo-liberalism’stransformationfromamarginalizedsetofintellectualconvictionsintoafull-blownhegemonicforcebeganwitheconomiccrisis,which weakenedexistinggovernmentsandrenderedpoliticalelitesamenabletoadifferentsystemofthought.Economicstressestookholdfromthemid-1960s(Harvey, 1989,2005),butthesourceofadecisiveendtotheprosperityofthepost-warera camein1973,whentheOPEC9 countriesrestrictedoutputandpromptedafivefoldincreaseinthepriceofoil(Prasad,2006).Asthecostsofproducingdomestic goodsrose,sodidbothinflationandunemployment—adevelopment,termed ‘stagflation’,thatdefiedKeynesianunderstandingsofhoweconomicsystems workedandfosterednewstrugglesoverpoliticalauthority.

Thesymbolicresourcesfromwhichmanyprotagonistsinthesenewstruggles drewwereAnglo-Americaninorigin,providedbyaparticularbranchofknowledgeproducerswithprofessionalinvestmentsoftheirown.Existingliteratureon thispointlaysouttheAmerica-centrismofneo-liberaleconomicthinkingintwo steps:(i)thepoliticallegitimationandprofessionalelevation(withineconomics) offreemarketthoughtviathedirectinterventionsofAmericanandU.S.-trained economistsinreformprojectsinLatinAmerica,and(ii)theinternationalization oftheeconomicsprofession(partlyviaEuropeanintegration)andthesolidificationofakindofprofessionallicensingpowerwithinAmericanacademe(Dezalay andGarth,2002;Fourcade,2006).

DezalayandGarthhighlighttheimportanceofthestructurallyanalogouspositionsofneoclassicaleconomistsintheUnitedStatesandLatinAmericaduring theKeynesianera.MarginalizedinboththeNorthandtheSouth,free-market economistsformedan‘unholyalliance’withconservativeRepublicans,media andbusinesspeopleand‘invested’internationallyinnewpoliticalprojects. AprimeexamplehereistheArnoldHarberger’s(oftheUniversityofChicago) useofUSAIDassistanceandphilanthropicfoundationstoinvestinforeigneconomicsdepartments,suchastheCatholicUniversityinSantiago,Chile,homeofthe infamous‘ChicagoBoys’.Chicago’ssoutherncounterpartsusedsimilarmeansto gaininfluence:buildingtieswiththemediaandeconomistsintheUnitedStates toaccruepowerintheirhomecountries.This‘madeforaremarkablestoryof

8 ThereisdisagreementonthequestionoftheimpactofIMFconditionality.Morebroadly,some questionhegemonicanalysesonthegroundsthattheyfail‘tomodeltheprecisemechanismof diffusionortoconsideralternativemechanisms’(Dobbin etal.,2007,p.457).Itisunclearthat field-orientedexplanationscanbefairlycritiquedwithintheframeworkofmechanisticanalysis (seepriorfootnote).

9 OrganizationofPetroleumExportingCountries.

exportandimport,whichthenhelpedtobuildthecredibilityoftheemerging Washingtonconsensus’(DezalayandGarth,2002,p.46).

OnceChicago-trainedeconomistswereabletotakecreditforanewpolitical consensusoneconomicmanagement,they‘movedseamlesslytowardthenew focusoninstitutionsandthestate:theso-calledmovebeyondtheWashington consensus’(DezalayandGarth,2002,p.47).Simultaneouslyembeddedin positionsofstatepowerandintheinternational‘marketofexpertise’,theylegitimatedtheirnewpowerfulpositionsbothfromwithoutandfromwithin.Theend resultwasthat:

[T]hecriteriaforlegitimateexpertisearesetaccordingtotheinternationalmarketcenteredintheUnitedStates.Thereisanewhierarchy thatplaceseliteU.S.professionalsatthetop[...]andwithineach countrythereisalsoatwo-tierprofessionalhierarchy.Thereisa cosmopolitaneliteandanincreasinglyprovincializedmassof professionalsinlaw,economicsandotherfields.(Dezalayand Garth,2002,p.57)

Fourcade(2006)placesarelatedemphasisontheAmerican-centrismofan increasinglyinternationalizedeconomicsprofession.Shearguesthattheinternationalizationofeconomicsisimportant;first,becauseoftheuniquesymbolic poweritbestowsuponeconomists‘toreconstructsocietiesaccordingtotheprinciplesofthedominanteconomicideology’(Fourcade,2006,p.157).Second, ‘thesetransformations[...]feedbackintotheprofessionalizationandsocialdefinitionofeconomistsworldwide’(ibid).Whileeconomicsdoesnothaveaformal, closedlicensingsystem,itsinternationalizationasaprofessionhastendedto workaccordingtostandardsandpracticesdefinedinthetransatlanticworld, especiallyintheUnitedStates.TheeffectisthatAmericangraduateandprofessionalschoolsprimarily,andEuropeanschoolssecondarily,function‘aselite licensinginstitutionsformuchoftherestoftheworld’,producinginternational convergenceintheeconomicsprofessionaroundAnglo-Americanprofessional standardsasifitwerealicensedfield(Fourcade,2006,p.152).

Inits‘project’form,neo-liberalismcanbeunderstoodasaninterconnectedsetof counter-hegemonicpoliticalandintellectualstruggles(DezalayandGarth,1998, 2002,2006;TelesandKenney,2008).Itgestatedwithinaperiodmarkedbythe riseofSovietcommunism,theriseofthewelfarestateinWesterndemocracies (thefabled‘GoldenAge’;Esping-Andersen,1997,1999)andthedominanceof Keynesian-styleapproachestomacroeconomicmanagement(Hall,1989).Politically,theprojectwassupportedbyconservativeswhowere‘frustratedbywhat

theybelievedwereinternationalnetworksofleftistexpertswhopreachedand thenimplementedschemesforgovernmentexpansion’(TelesandKenney, 2008,p.136).Intheintellectualrealm,itgrewfromasimilarunderstandingof Keynesianerapoliticsasdefinedbyanessentiallysocialistimpulsethatwould, onewayoranother,pavethewaytototalitarianism.

Thisstorycouldbeelaboratedatlength,butabriefaccountmakesthecase. TheDepressionandtheWorldWarsfosteredabroaddebateamongelites,and particularlyintellectuals,seekingtoexplainEurope’scivilizationalbreakdown andprescribeapathforre-building.Withinthiscontext,theAustrianeconomist FriedrichvonHayekbecamethecharismaticcentreofanetworkof laissezfaire thinkers—agroupsetapartbyitsrejectionofthewidelyacceptedargument thatcapitalismrunamokwastherootcauseofEurope’scollapse.Marginalized frominfluenceinmainstreampoliticsintheearlypost-warperiod,this‘small andexclusivegroupofpassionateadvocates—mainlyeconomists,historians andphilosophers—builtanintellectualsanctuaryinSwitzerland:theMont PelerinSociety.10 TheSocietyfirstmetin1947undertheauspicesof Hayek—itsfirstpresident—andhismentorLudvigvonMises(Harvey,2005, pp.19–20).11

Inhisseminalwork TheRoadtoSerfdom (Hayek,1994[1944])—dedicatedto the‘socialistsofallparties’—HayekarguedthatbothSoviet-stylecentralized economicplanningand‘theextensiveredistributionofincomesthroughtaxation andtheinstitutionsofthewelfarestate’wouldhavethesameauthoritarian result—although‘moreslowly,directlyandimperfectly’(ibid,p.xxiii)inthe caseofWesterndemocracies.Writtenbetween1940and1943outof,in Hayek’swords,an‘annoyancewiththecompletemisinterpretationinEnglish “progressive”circleswiththecharacteroftheNazimovement’, Serfdom was apoliticalinterventionmeanttocorrecttendenciestoequateNazismwithcapitalistexcesses—thatis,arefutationoftheclaimthattheriseoffascismwasprompted by‘thedyinggaspofafailedcapitalistsystem’(Hayek,1994[1944],p.xxi).

Serfdom wasalsodirectlyinspiredbythestirringsoftheBritishwelfarestate. HayekinitiallycomposeditsbasicargumentinamemotoSirWilliamBeveridge, thedirectoroftheLondonSchoolofEconomics,intheearly1930s

10 http://www.montpelerin.org/home.cfm.ThefirstmeetingoftheSocietyhad36participants. Harvey(2005,p.20)notesthatfortheMontPelerinSociety’smembers,‘[t]heneo-liberallabel signaledtheiradherencetothosefreemarketprinciplesofneo-classicaleconomicsthathad emergedinthesecondhalfofthenineteenthcentury(thankstotheworksofAlfredMarshall, WilliamStanleyJevons,andLeonWalras)todisplacetheclassicaltheoriesofAdamSmith,David Ricardo,and,ofcourse,KarlMarx’.

11 Inthe1920s,HayekworkedasvonMises’studentinVienna,andwasteachingattheUniversityof LondonwhenHitlercametopowerin1933.

(Hayek1994[1944]).Beveridge,undeterredbyHayek’sarguments,authoredthe famous1942BeveridgeReport,whicharticulatedwhatwouldbecomethebasic principlesofBritishwelfareinthepost-warperiod.12 Frustratedbyhisinability toinfluencepoliticalcurrentsinBritain,13 Hayekandhiscolleagueshelpedto createatransatlanticfree-marketmovementthatcross-cuttheacademicandnonacademicworlds.ThinkersinvolvedintheworkoftheMontPelerinSociety,for instance,werealsoinvolvedintheestablishment,legitimationandproliferation oftwointerconnectednetworksofassociatedfree-marketthinktanks.

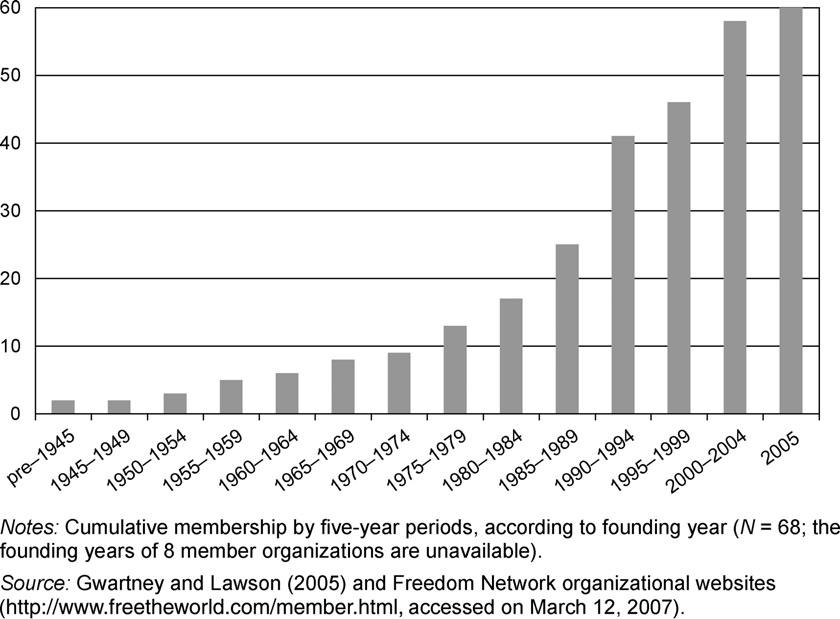

SirAntonyFisherstandsoutamongthevarioussignificantfiguresinvolvedin thiseffort.FisherreportedlymetHayekattheLSEin1945,whereHayekadvised himto‘avoidpoliticsandreachtheintellectualswithreasonedargument’.14 Hayek’sadviceinspiredFishertoestablishtheInstituteofEconomicAffairs (IEA)inLondonin1955‘toexplainfree-marketideastothepublic,including politicians,students,journalists,businessmen,academicsandanyoneinterested inpublicpolicy’.15 Inthe1970s,Fisherwouldbecomeacentralforcebehindthe establishmentoffree-marketorganizations,linkingtheIEAwithnewandexisting organizationsinothercountriesviaatleasttwoNorthAmericanorganizational nodes.OnewastheFraserInstituteinVancouver(foundedin1974bythe CanadianbusinessmanPatBoyle;Cockett,1995),nowthecentreofthe‘Freedom Network’(Figure2;Gunderson,1989;GwartneyandLawson,2005,2007).16

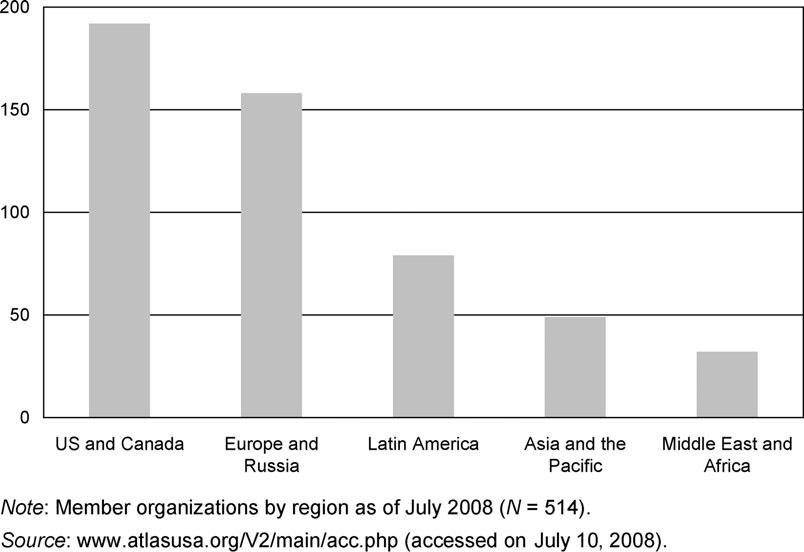

Asecond,largernetworkdevelopedaroundtheAtlasEconomicResearch Foundation,17 establishedbyFisherin1981inArlington,VA.Morethan500 AtlasFoundationmemberorganizationsexistedbytheyear2008,ranging acrossmostregionsoftheworld(Figure3).

12 Hayekremarkedinhis1956prefaceto Serfdom that‘itwasalreadyfairlyobviousthatEngland herselfwaslikelytoexperimentafterthewarwiththesamekindofpolicieswhichIwasconvinced hadcontributedsomuchtodestroylibertyelsewhere’(Hayek,1994[1944],p.xxviii).

13 Thoughheintended Serfdom asawarningto‘thesocialistintelligentsiaofEngland’,Hayekfounda warmerreceptionintheUnitedStates.In1938,hisargumentswerepublishedinthe Contemporary Review andlaterappearedasa‘PublicPolicyPamphlet’byProfessorHarryG.Gideonseatthe UniversityofChicago(Hayek,1994[1944],pp.xxvii–xxvii).

14 Source:http://www.iea.org.uk/record.jsp?type ¼ page&ID ¼ 24,accessedonFebruary13,2007.

15 Source:http://www.iea.org.uk/record.jsp?type ¼ page&ID ¼ 24,accessedonFebruary13,2007.

16 TheFraserInstituteisaffiliatedwithsevenNobelLaureateeconomistsandhashostedMontPelerin Societymeetingsonatleastthreeoccasions:1983,1992and1999(FraserInstitute,2004).Fraser’s sevenassociatedNobelLaureatestogetheraccountforthepresidenciesofalmosthalfoftheMont PelerinSociety’syearsofexistence.

17 FisherestablishedtheAtlasEconomicResearchFoundationasanorganizationalnodefor internationalfree-marketorganizationsandameansofcollectinganddisseminatingfundingfrom privateandcorporatedonors. 712Thestateoftheart

Figure2 Thefreedomnetworkasof2005.

Figure3 AtlasEconomicResearchFoundationanditsmemberorganizations.

Thepoliticaleffectsofthesekindsofknowledge-producingorganizationsare receivingincreasingattention(Medvetz,2007).Theirinfluencedependson relationshipswithpoliticalpartiesandthestate,nottomentioncompetition

714Thestateoftheart

withorganizationalchallengers.18 Nonetheless,thefactoftheirproliferationis indicativeofthebreadthofneo-liberalism’sinternationalreachasanintellectual andprofessionalproject.

OutsideoftheUnitedStates,free-marketthinktanksprobablyplayedaspecialrole withinthesocialspacescreatedbytheColdWardivide—thatis,inadditiontothe obviousroleofprovidingasupplyofneoliberalexpertiseafter1989.19 Onthebasis ofastudyattheCenterfortheStudyofEconomicandSocialProblems(CESES)20 inMilan,Bockman(2007)arguesthatneo-liberalthoughtgrewoutof‘liminal spaces’betweencommunismandcapitalism,particularlyafterStalin’sdeathin 1953.SheshowsthatneitherthefoundersnortheparticipantsinCESESactivities hadstrongorconsistentanti-communistidentities(2007,pp.349–350).21 AssemblingthinkerswhoseorientationsdidnotfitneatlyoneithersideoftheIron Curtain,theCESESprovidedacrucialspaceinwhichknowledgeproducers sharedknowledgeaboutcapitalismandthesocialistexperiment.Echoingearlier arguments(withGilEyal)astotheroleofsocialistcountriesasalaboratoryfor economicknowledge(BockmanandEyal,2002),Bockmanhighlightsthatthe CESESbecameoneofmanysitesofknowledgeproductionthatwereessentialfor neo-liberalism’sreachintotheranksofexpertprofessionalsandpoliticalelites.

Conceivingofneo-liberalismasasemi-religiousprojectrecallsPolanyi’s discussionofthe‘liberalcreed’asasemi-religiousbeliefsystem(Polanyi,2001 [1944]).Here,‘neo’referstoarevivalofasetofideasdatingtoeighteenthandnineteenth-centuryEngland,re-tooledtofittheinstitutionsandpoliticsof thelatepost-warenvironmentandupdatedwiththeconceptsandtechnologies

18 Forinstance,agroupofAmericanintellectualandpoliticalfiguresestablishedtheEconomicPolicy Institutein1986‘tobroadenthediscussionabouteconomicpolicytoincludetheinterestsoflow-and middle-incomeworkers’.ItsfoundersincludedRobertReich,aunion-friendlyAmericanthinkerwho wouldlaterbecomePresidentClinton’sSecretaryofLabor(Greenhouse,1993;http://www.epi.org/ content.cfm/about,accessedonJune24,2008).

19 Cockett(1995)notesthattherapidlyexpandingAtlasnetworkmeantthat‘[w]hentheBerlinWall camedownin1989,therewasanarmyofcommitted,internationaleconomicliberalsrearedinthe Hayekiantradition,armedwithclipboardsandportablephones,waitingtomoveintoEastern EuropeandthedisintegratingSovietUniontoconverttheirailingeconomies’(1995,p.307).

20 Createdin1964byConfindustria,theprimaryassociationrepresentingItalianprivateindustry.

21 Bockmancritiquesatendencyto‘assumeomnipotentactivists,whohaveclearright-wingidentities andsuccessfullyspreadalreadypackagedright-wingorpro-capitalistideologyorpropaganda.These accountsalsoassumeclearlyidentifiablerecipientsofthispropaganda—eitherotheractivistsornaıve victims—whohearthemessageofneo-liberalismclearly,areconverted,andhavenoothercompeting economicorpoliticalideas’(Bockman,2007,p.344).

ofanincreasinglycompetitiveandmathematicaleconomicsprofession(Block, 2001;BlockandSomers,2003,2005;Krippner etal.,2004;Young,2005).

Neo-liberalismisdistinctivewithrespecttootherliberalismsinitsdriveto breakthe‘market’looseinconceptualtermsandelevateittoalevel above politics—thatis,tofreeitfrompoliticalinterventionsofanykind.22 Itsrejection ofthemarket’sembeddednesscontrastsinparticularwithContinentalordoliberalism(Friedrich,1955),whichwasprobablythesiteofthefirstselfproclaimed‘neo-liberals’,nottomentionthefirstarticulationsofa‘thirdway’ betweentotalitarianismand laissezfaire. 23 Significantly,ordo-liberalismwasa historicistschoolofthoughtinwhichHayekwasoriginallyrootedbefore breakingoffonamorestarkly laissezfaire trajectory.24

Ordo-liberalsviewedeconomicdynamicsas‘“embedded”inpolitics’ (Friedrich,1955,p.511).WilhelmRopke,oneoftheschool’scentralfigures, emphaticallyrejectedthenotionthatthemarketis‘a selfdependent process whirringawayautomatically’(Ropke1996[1948],pp.31–32).25 Though opposedtocentralplanning(subvention),ordo-liberalsbelievedthatgovernment interventionswereeconomicnecessities:

Thekeysloganisthe‘socialmarketeconomy’(sozialeMarktwirtschaft), aneconomywhichisdefinitely‘free’,ascomparedwithadirectedand plannedeconomy,butwhichissubjectedtocontrols,preferablyin strictlylegalform,designedtopreventtheconcentrationofeconomic power,whetherthroughcartels,trusts,orgiantenterprise.Opposedto allandeverykindofsubvention[...]theproponentsofthe‘social marketeconomy’callforgovernmentalinterventiononlyforthe purposeofhasteningimpendingchangesbyfacilitatingthem. (Friedrich,1955,p.511)

22 Thisconceptualbreakisrootedintheperspectivethat‘marketsconstitutethebestpossible arrangementforthesatisfactionofindividualneedsandtheefficientallocationofresources’, harkeningfromSmithandWalras(FourcadeandHealy,2007).

23 Inthe1950s,theFreiburgSchoolwashometoordo-liberalism,andwas‘personifiedinthefigureof theFederalRepublic’sdynamicministerofeconomics,LudwigErhard’(Friedrich,1955, pp.509–510).

24 Hayekwasatonepointlistedontheordo-liberals’editorialboard(Friedrich,1955,p.509).He brokewithordo-liberalismon,amongotherquestions,whethercapitalismwasaself-destructive andinherentlypolarizingforce,andthereforetobeblamedfortheWorldWars.

25 The‘cardinalfaultoftheoldliberalcapitalisticthought’wastoforgetthat‘mankindarenotmerely competitors,producers,menofbusiness,membersofunions,shareholders,saversandinvestors,but aresimplyhumanbeingswhodonotliveonbreadalone’(Ropke,1996[1948],pp.31–32). Mudge:whatisneo-liberalism?715

Ordo-liberalscalledfor‘measuresa ndinstitutionswhichprovidecompetition’in‘awell-consideredmoralandlegalframework’,supportedby ‘astrongandimpartialgovernment’(Ro pke,1996[1948],p.28).Theyalso calledfor‘structuralpolicy’inthespiritof‘economichumanism’,26 undoingmonopoliesandpromoting‘anameliorationofthehardshipsand trialsoftheweakerelementsinsociety’ina‘policywhichcanbedescribed inthecatchphrases“deproletarianisation”andeconomicdecentralization’ (Ro pke,1996[1948],p.30).

Neo-liberalism’sideologicaldistinctivenessisidentifiableinthemissionsof internationalpoliticalorganizations,whichmarkthepoliticalinstitutionalizationofdominantschoolsofeconomicthought.Threeemergedintheearly post-warperiod:theCentristDemocratInternational(CDI),foundedin 1961to‘expandinternationalcooperationbetweenChristiandemocratic partiesandpromotetheformationofnewparties’(Szajkowski,2005);the LiberalInternational(LI),foundedin1947inOxford,UK;theSocialistInternational(SI),foundedin1951inFrankfurt—originatingfromtheFirstand SecondInternationals(1864–1876and1889).TheLI’sformationexpressed theordo-liberalschool’spoliticalreach,whichspanned‘Scandinavia,thelow Countries,[...]FranceandItaly’intheearlypost-warperiod(Friedrich, 1955,pp.509–510).Neo-liberalism,meanwhile,wasinternationalizedofficiallyin1983withtheestablishmentoftheInternationalDemocratUnion (IDU)inLondon—informallydubbingitselfthe‘FreedomInternational’. MargaretThatcher(UK),GeorgeH.W.Bush(UnitedStates),JacquesChirac (France)andHelmutKohl(Germany),amongothers,jointlyestablished theIDU.

ThelinebetweentheLIandtheIDUisdistinct.AsshowninTable1,theLI emphasizesmarketsalongwiththemesofcommunity,povertyandsocial justice;itoutlinesnocomprehensivetheoryoftheindividualorofhumanity, butinsteademphasizestheinstitutionalconditionsforfreedomandawariness ofmonopolyandtheconcentrationofpower.Incomparison,themoremarketcentricandindividualisticbentoftheIDUisunmistakable.Inits2005Washingtondeclaration,issuedatthePartyLeaders’MeetinginWashington,DC,theIDU describesitselfintermsofthecorevaluesofneo-liberalism—freeenterprise, freetrade,privateproperty,democracy,anindependentjudiciaryandlimited government—butdoesnotechotheLI’sconcernswithcommunity,poverty, multilateralismortheconcentrationofpower.

Thesemi-religiouselementofneo-liberalismisnotableintheIDU’sclaimsto theuniversalityofitsvisionandagraspofthespiritualessentialsofhuman

26 HereferswithadmirationtothereformsofChiangKai-ShekinChinaandRooseveltintheUnited States(Ropke,1996[1948],p.30).

Table1 MissionstatementsoftheLiberalInternational(LI)andtheInternationalDemocratUnion (IDU)

LI(foundedin1947)IDU(foundedin1983)

Liberalsarecommittedtobuildandsafeguard free,fairandopensocieties,inwhichthey seektobalancethefundamentalvaluesof liberty,equalityandcommunity,andinwhich no-oneisenslavedbypoverty,ignoranceor conformity.

Liberalschampionthefreedom,dignityand well-beingofindividuals.

Weacknowledgeandrespecttherightto freedomofconscienceandtherightof everyonetodeveloptheirtalentstothefull.

Weaimtodispersepower,tofosterdiversity andtonurturecreativity.

Thefreedomtobecreativeandinnovativecan onlybesustainedbyamarketeconomy,butit mustbeamarketthatofferspeoplereal choices.

Thismeansthatwewantneitheramarket wherefreedomislimitedbymonopoliesoran economydisassociatedfromtheinterestsof thepoorandofthecommunityasawhole. Liberalsareoptimisticatheartandtrustthe peoplewhilerecognizingtheneedtobe alwaysvigilantofthoseinpower.

(Source:www.liberal-international.org, accessedonDecember1, 2005)a

Wearethepartiesofthecentreandcentre right,ofChristianDemocracyandof conservatism.

Wereflecttheworld’sdiversityandpossess unityinthevalueswechampion.

Ourcommonvisionisoffree,justand compassionatesocieties.

Weappreciatethevalueoftraditionand inheritedwisdom.

Wevaluefreelyelectedgovernments,the market-basedeconomyandlibertyforour citizens.

Wewillprotectourpeoplefromthosewho preachhateandplantodestroyourwayof life.

Freeenterprise,freetradeandprivate propertyarethecorner-stonesoffreeideas andcreativityaswellasmaterialwell-being.

Webelieveinjustice,withanindependent judiciary.

Webelieveindemocracy,inlimited governmentandinastrongcivicsociety. Weseetheseasuniversalideas.

Athirstforfreedomisnotapeculiartraitof peoplefromofanyonecontinent,region, nation,raceorreligion—itisademandfor allhumanity.

Itisalsothefoundinginspirationforthe InternationalDemocratUnion.

(Source:IDU2005:2)b

aTheLIalsoemphasizesmultilateralismandtherightsofnationalandethnicminorities.Fromits1997 manifesto:‘Webelievethattheconditionsofindividuallibertyincludetheruleoflaw,equalaccesstoafulland variededucation,freedomofspeech,association,andaccesstoinformation,equalrightsandopportunitiesfor womenandmen,toleranceofdiversity,socialinclusion,thepromotionofprivateenterpriseandofopportunitiesforemployment.Webelievethatcivilsocietyandconstitutionaldemocracyprovidethemostjustand stablebasisforpoliticalorder. Webelievethataneconomybasedonfreemarketrulesleadstothemost efficientdistributionofwealthandresources,encouragesinnovation,andpromotesflexibility.Webelieve thatclosecooperationamongdemocraticsocietiesthroughglobalandregionalorganisations,withinthe frameworkofinternationallaw,ofrespectforhumanrights,therightsofnationalandethnicminorities, andofasharedcommitmenttoeconomicdevelopmentworldwide,isthenecessaryfoundationforworld peaceandforeconomicandenvironmentalsustainability’.

bThisdeclarationwaskindlysenttomebytheIDUinresponsetoanemailrequestformoreinformationabout theorganization.

nature(thatis,individuals’‘thirstforfreedom’).27 Thisechoestheimplicitreligiosityin,forinstance,JosephStiglitz’accountofIMFeconomistsas‘market fundamentalists’(Stiglitz,2002);MargaretThatcher’sfamous1974announcement,whilepullingHayek’s TheConstitutionofLiberty (Hayek,1978[1960]) outofherbriefcaseintheBritishHouseofCommons,that‘thisiswhatwe believein’;andthesemi-evangelicaltoneofMiltonFriedman’sarticulationof marketsasthesourceandarbiterofhumanfreedoms(FriedmanandFriedman, 1980).

5.Neo-liberalism’sbureaucraticface

Neo-liberalpolicyexistsasarepertoireorpackage—asetofreformsjointlytargeted,fromtheneo-liberalperspective,atpromotingunfetteredcompetitionby gettingthestateoutofthebusinessesofownership,preventingpoliticiansfrom pursuing dirigiste-styleeconomicmanagement,andintroducingmarket(or market-like)competitioninpreviously‘sacred’institutionalspaces(aprime exampleispubliceducation).28 Note,however,thatamutuallyexclusivedistinctionbetweenmarketandstateunderpinstheneo-liberalideaof‘freeing’the market—anotionthathaslongbeencriticizedineconomicsociology(Krippner andAlvarez,2007).29 Neo-liberalism’spolicyexpressionsaretermedasits ‘bureaucraticface’inordertodrawattentiontotheirnecessarybaseswithin thebureaucraciesofthestate.ThisisinlinewiththePolanyianinsightthatneoliberalreformsdonotimply‘retrenchment’oreliminationofstatebureaucracies (Cerny,1993;Vogel,1996;Krippner,2007).Rather,theyimplythecreation,one mightsay,ofthe‘neo-liberalstate’(Brown,2003).

Bythe1990s,theneo-liberalpolicyrepertoireappearedintightlydefined incarnations,asinJohnWilliamson’snow-famousdelineationofthe‘termsof theWashingtonconsensus’(Williamson,1990,1993).Therepertoirehasfive maincomponents:the privatization ofpublicfirms;the separationofregulatory authority fromtheexecutivebranch—whichincludesthecreationofapolitically independentcentralbank;the depoliticization ofeconomicregulationby

27 Mypointisnotthata‘thirstforfreedom’isnotahumaninstinct,butratherthattheIDUdefines freedominaparticularway.Consider,forinstance,thenon-economicnotionarticulatedinFDR’s famous1941‘fourfreedoms’speech:freedomfromwant,freedomofworship,freedomofspeech andfreedomfromfear(Roosevelt,1941).

28 IntheUnitedStates,oneofthemoststrikingpoliticalseachangesintheneo-liberalerawasthe legitimationofargumentsfortheintroductionofmarket-likecompetitionintopubliceducation— articulatedbyhigh-profileeconomistsandpoliticalscientists,includingMiltonFriedman,John ChubbandTerryMoe(FriedmanandFriedman,1980;ChubbandMoe,1990).

29 Ithankananonymousreviewerforhighlightingthispoint.

Mudge:whatisneo-liberalism?719

insulatingregulatoryauthoritiesfrompoliticalinfluenceandthe liberalization of thedomesticandinternationaleconomybyopeningmarketstomultipleservice providers(Henisz etal.,2005).Tothis,weshouldalsoadd monetarism or,in otherwords,themanipulationofthesupplyofmoneyratherthandemand managementviafiscalintervention.30

Thespreadofneo-liberalpolicyiswellestablishedempirically,thoughtemporalandgeographicvariationsaremattersofexplanatorydebate.Inworld-level datapresentedbySimmons etal. (2006),privatizationandfinancialopenness acceleratedmarkedlyfromthelate1980s,followingtheS-shapedcurvethatis typicalofdiffusion-typeprocesses.WesternEuropeanandNorthAmerican countriessurgedtowardstotalfinancialopennessstartinginthelate1980s; LatinAmericaandEasternEuropemovedsimilarly(thoughlessdramatically) intheearly1990s.PrivatizationacceleratedinEasternEuropeinthe1990s and,surprisingly,intheMiddleEastandNorthAfrica.Bytheearly2000s,variationontheseindicatorsacrossallcountriesreachedanall-timelow.Likewise, Henisz etal. (2005)emphasizeabroad,internationalliberalizingtrend, particularlyininfrastructureindustriesthatwereformerlypredominantly state-owned(telecommunications,electricity,water,sanitationandtransportation;p.871).31 QuinnandToyoda(2007)trackageneralincreaseintheopennessofcapitalandcurrentaccountsfor82countriesfromthe1980sonward,32 arguingthatglobalanddomesticideologiesplayindependentcausalrolesin thediffusionoffinancialliberalizationbyalteringtheincentivesandopportunitiesfacedbygovernmentofficials.

Muchscholarshiponmoderncapitalismscaststhelastdecadesofthetwentiethcenturyasanewpoliticalera(Hall,1989;Esping-Andersen,1990,1994, 1997;Steinmo etal. ,1992;Pierson,1994,1996;HallandSoskice,2001). Formerlymarginalizedfree-marketthoughtenjoyedapoliticalrevival, 33

30 Oneimplicationofmonetaristpolicymakingisastrongemphasisonbudgetaryrestraintandamove awayfromcounter-cyclicalpublicspending.

31 Henisz etal.’sanalysisdiffersfromothers,inpart,becausetheyemphasizefourkindsoftrendsas partofapackageofoptions(‘jointadoption’):privatizationofstate-ownedfirms;separationof regulatoryauthorityfromtheexecutivebranch;depoliticization;liberalization(2005,pp.871–872).

32 Liberaleconomicreformshadapoliticalcomplementintheformofa‘thirdwave’of democratizationinformerlynon-democraticcountries.

33 Hayekrosefromrelativeobscuritytointernationalprominenceintheearlyyearsofthe‘new politics’,winningtheNobelPrizein1974.

markingtheriseofanewsetof‘cognitivecategorieswithwhicheconomic andpoliticalactorscometoapprehendtheworld’(FourcadeandBabb, 2002,p.534). 34

Bythe1990s,someunderstoodneo-liberalism’swidespreadmanifestations as‘proof’ofitsontologicalunassailability.In1993,Williamsonhimselfmade ananalogybetweenneo-liberalism’scorepropositionsandthebeliefthat ‘theEarthisflat’(Williamson,1993).Identifyinghimselfas‘leftofcentre’,he questionedwhetheralternativeeconomicphilosophiesshouldhavepolitical representationatall:

Itwouldberidiculoustoarguethatasamatterofprincipleeveryconceivablepointofviewshouldberepresentedbyamainstreampolitical party.Noonefeelsthatpoliticaldebateisconstrainedbecauseno partyinsiststhattheEarthisflat.[...]Theuniversalconvergence seemstometobeinsomesensetheeconomicequivalentofthese (hopefully)no-longer-politicalissues.Untilsucheconomicgood senseisgenerallyaccepted,thenitspromotionmustbeapoliticalpriority.Butthesooneritwinsgeneralacceptanceandcanberemoved frommainstreampoliticaldebate,thebetterforallconcerned. ... [T]hesuperioreconomicperformanceofcountriesthatestablish andmaintainoutward-orientedmarketeconomiessubjecttomacroeconomicdisciplineisessentiallyapositivequestion.Theproofmay notbequiteasconclusiveastheproofthattheEarthisnotflat,butit issufficientlywellestablishedastogivesensiblepeoplebetterthings todowiththeirtimethantochallengeitsveracity.(Williamson, 1993,p.1330)

Williamson’spositiveclaimsastothesuperioreconomicperformanceof ‘neo-liberalized’economiesandhisnormativeclaimsastothenon-sensibility ofpoliticalalternativesarecontestable,butthisisbeyondthescopeofthe presentdiscussion.Rather,whatisinterestingishissimultaneousrecognition andsanctificationofare-centringofpoliticalspaceonaneweconomicphilosophy.DrawingfromtheworkofMeyerandRowan(1991,p.41),neo-liberalism canbeunderstoodhereasa‘setofmythsembeddedintheinstitutional environment’thattendstoanchorpoliticalactors’orientations.Itisprecisely thisre-centringthatmarkstheriseofneo-liberalpolitics.

34 CampbellandPedersen(2001)describetheriseofneo-liberalismasasetof‘institutionalchangeson ascalenotseensincetheimmediateaftermathoftheSecondWorldWarandaprojectthathas attemptedtotransformsomeofthemostbasicpoliticalandeconomicsettlementsofthepostwar era’(2001,p.1).

Somescholarshiptendstografttheterm‘neo-liberal’uncomfortablyontoold politicaldistinctions—implicitlyreservingthelabelforpartiesoftheright, withemphasisonAnglo-Saxoncountries.Thetermisoftenusedtoinvoke AmericanRepublicansorBritishConservatives—followingthehistoricalprototypesembodiedinthefiguresofRonaldReaganandMargaretThatcher.35 Yet,asnotedinliteratureonthe‘thirdway’andalimitedcriticalscholarship onEuropeanintegration,neo-liberalismreacheswellbeyondnationallybound politicsanddoesnotmeshneatlywithright–leftdistinctions(Dezalayand Garth,1998;Holmes,2000;Green-Pedersen etal.,2001;CafrunyandRyder, 2003;vanApeldoorn etal.,2003;Hay,2004).

Again,thiscouldbeelaboratedatlength,butabriefaccountwillsuffice.In theUnitedStates,the‘neo-liberal’moniker,reportedlycoinedby Washington Monthly editorCharlesPeters,wasgivenformina1983conferenceofacademics andprofessionals(teachers,lawyers,journalistsandacademics)sympathetic totheDemocraticParty(Farrell,1983).Thiswasoneofvariousforathat helpedtosolidifyamarket-friendlypoliticalmovementstirringamongthe Democrats—theriseofa‘newphilosophy’thatsoughttobreakwiththe party’spastby,amongotherthings,shiftingeconomicpolicypriorities‘away fromanemphasisonredistributionandtowardanemphasisonthetwingoals ofrestoringgrowthandopportunity’(Hale,1995,p.211).In1985,thisneoliberaldriftwithintheDemocraticPartyculminatedwiththeestablishmentof theDemocraticLeadershipCouncil(DLC)—theorganizationalbasisfrom whichtheClintonswouldlaterrisetopoliticalpower.

The‘neo-liberal’monikerdidnothavestablemeaninginworldsbeyondthe Americanone,butAmericanneo-liberalsnonethelesshadEuropeanparallels. Inthe1990s,NewLabour’s‘thirdway’politicsweremarkedbyanacceptance oftheconstraintsofeconomicglobalization,arejectionof‘old’binaries(right versusleft;stateversusmarket;capitalversuslabour),adecidedlypositiveorientationtowardsbusinessandfinanceandanewarticulationofcollectiveinterest inindividualisticterms(Leys,1997).Bycentury’send,thisnewbrandofleftism reachedwellintotherestofEurope:inGermany,theNetherlands,Portugal,

35 SeeWoolley’sanalysisofmonetaristeconomistsandAmericanpoliticalconservativesduringthe Reaganyears(Woolley,1982).Prasad’sdiscussionofneo-liberalisminFrancefocusesonparties andpoliticsoftherightanddiscussestheFrenchleft’spartialembraceofneo-liberalideasonlyin the1990s—aspartofitscommitmenttotheGrowthandStabilityPact(1996);intheAmerican case,shefocusesexclusivelyontheReagan–Bushyears(Prasad,2005).Sheidentifiestheperiod between1990and2005asthe‘consolidation’phaseofneo-liberalism,inwhich‘thecomingof EuropeanunificationstrengthenedthehandofEuropeanneo-liberalsinwaysthatremaintobe workedout’,butleavestheidentityofEuropeanneo-liberalsundefined.

722Thestateoftheart

Sweden,Denmark,ItalyandBelgium,leftistleadersespousedmorederegulated labourmarketsandhighlightedthenecessitiesofadaptationtomarketforces.

Thiswasnotmererhetoric.IntheUnitedStates,PresidentClintonsigneda 1996billthat‘endedwelfareasweknewit’;intheUK,TonyBlairtouted public–privatepartnershipsandoversawtheintroductionoftuitionfees in1997;centre–leftgovernmentsinGermanyandtheNetherlandspursued deregulatorylabourmarketreformsinthe1990sandearly2000s(Visserand Hemerijck,1997;Esping-Andersen,2002).InSweden,‘ThirdRoad’social democratsledthechargetoderegulatefinancialmarketsin1985–1986,phased outexchangecontrols,pushedthroughreductionsinmarginalincometax ratesin1989–1990andappliedformembershipintheEuropeanCommunity (Pontusson1992,1994).

Thetransatlanticappearanceofmarket-friendlyleftswasnocoincidence: continuingalongtraditionofexchangeofpoliticalideas(Rueschemeyer andSkocpol,1996;Rodgers,1998), 36 theirpolicyprioritieswerecrystallized andextendedviaathickeningnetworkofpoliticalconnectionswithin Europe,ontheonehand,andbetweenEuropeandtheUnitedStatesonthe other—botheffects,inpart,ofEuropeanintegration.Bytheyear2000,the ‘neo-liberalized’leftsstartedtolookmoreandmorelikeaninternationalpoliticalmovement.Recognizingthisbroadreach,theAmericanProgressivePolicy Institute(PPI)—thethinktankarmoftheDLC—pronouncedthe‘thirdway’ in1999tobe‘themostrapidlygrowinginternationalpoliticalmovementin theworld,andtherisingtideinthecentre–leftpoliticalpartiesthroughout Europe’.37

6.2Neo-liberalismattheintersectionoftheintellectualandthepolitical Ideologicalsystemshaveanexistencethatisexternaltopoliticspartlybecause theyareborninspacesthatmaynotbepolitical.Theriseofanewsetofideologicalforcesis,inotherwords,aninstitutionalphenomenoninandofitself;itmay berootedinnon-politicalrealmsofstruggleandcollaboration.Theserealms mightbeunderstoodasbelongingtothe‘culturalfield’—thatis,socialspaces inwhichactorsareengagedinstrugglesoverauthoritativeclaimstotruthand meaning:religion,art,literatureandjournalism,the‘human’sciences.Ideological

36 ThecaseoftheAmericanProgressivePartyisaparticularlyinterestingtestamenttotheformative influencesoftransatlanticexchangeinpoliticallife(Davis,1964).

37 http://www.ndol.org/ndol_ci.cfm?kaid ¼ 128&subid ¼ 185&contentid ¼ 880,accessedonDecember 5,2006.TheDLCmadethispronouncementtomarkanApril1999‘roundtablediscussion’that includedFirstLadyHillaryRodhamClintonandDLCPresidentAlFrom.ItfeaturedTonyBlair, GerhardSchroeder,WimKokandMassimoD’Alema.Theroundtablewasasecondfollow-upto aninitialmeetingbetweenHillaryClintonandTonyBlairthattookplacein1997.

systemsemergingoutofthesespacesintersectwithpoliticsbecauseofthehybrid intellectual–politicalrolesplayedby‘knowledge-bearing’elites(Rueschemeyer andSkocpol,1996).

Despiteneo-liberalism’spervasiveness,thereisatendencytoconstrueitnarrowlyinbothpoliticalandgeographicalterms.Geographically,neo-liberalismis oftenconflatedwithAnglo-Americanpolitics,implyingthatContinentaland NorthernEuropeanpoliticalelitesare‘naturally’opposedtotheimplementation ofneo-liberalpolicies.Politically,thereisaproblematictendencytoconflateneoliberalismwiththepoliticalright.Yetafailuretograsptheriseofneo-liberalismas anideologicalsystembornoutsideofpoliticsimposesarbitraryanalyticalblinders onquestionsofneo-liberalism’spoliticaleffects.ThatcherandReaganwere undoubtedlyneo-liberalism’smosthigh-profilechampionsinthe1980s,butthe truthwasthatneo-liberalorientationshaveenteredintomainstreampolitics sincethe1970swithoutregardforoldpartisandividesornationalboundaries.38 Thoughtheyfeaturedimportantvariations,inthe1990stheriseofmarket-friendly politicsacrossthepoliticalspectrumbecameanunmistakablephenomenon.

Morespecifically,theconflationofneo-liberalismwithAnglo-American ‘rightism’impedesasocialscientificgraspofthenatureanddynamicsofthe ‘newpolitics’intwoways.First,thetendencytoconflateneo-liberalismwith Anglo-AmericanpoliticsimpliesthatContinentalandNorthernEuropeanpoliticalelitesareintrinsicallyopposedtotheimplementationofneo-liberalpolicies. Thishassometruthtoit,giventheentrenchmentofwelfaristtraditionsin Europe—butitisaclaimthatshouldbeevaluatedempiricallyratherthan takenasagiven.Second,ablindnesstoneo-liberalismasaforcethatcross-cuts ‘old’ideologicaldividesinright–leftpoliticstendstopre-emptsocialscientific inquiryintoanas-yetunexplainedhistoricalphenomenon:thatthemosteffectiveadvocatesofpoliciesunderstoodasneo-liberalinWesternEurope(and beyond)haveoftenbeenpoliticalandintellectualeliteswhoaresympathetic to,orarerepresentativesof,theleftandcentre–left.39

Thepointhereissimple:neo-liberalpoliticsdeservesthesameanalytical attentionasneo-liberalism’sothertwofaces.Partofthiseffortmustbethe rethinkingofthemeaningofneo-liberalismitself,consideringitseffectsasa

38 Cox(2001)notesthat‘thereisnopatternthatdistinguishesleftfromrightduringtheperiodof retrenchment.Thus,right-winggovernmentsinsomecountrieshavefoundtheireffortstoretrench frustratedbypublicopposition,whereasleft-winggovernmentsinothercountrieshavemanagedto enactdramaticreforms’.

39 Levy(2001)discussesLionelJospin’sprivatizationsandhisdecisiontorecastratherthanrepealthe 1997ThomasLaw,whichfosteredtheprivatizationofpensionfunds.Heargues(rightly)thatthe Frenchleftsoughttoadaptneo-liberalpolicyreformsalongprogressivelines—butthisdoesnot addressthebasicquestionofwhatproducedandlegitimatedneo-liberalprinciplesinthefirstplace.

generalforceintersectingwithpoliticalliferegardlessofsocialdemocratic traditionsornationalboundaries.

Theconceptualizationofneo-liberalismisacentralpointofconfusioninunderstandingsofpoliticsandpolicymakingsincethe1970s.Thisarticleseekstoshed somelightonthisissuebydefiningneo-liberalismanddelineatingthehallmarks ofitsthree‘faces’.Ratherthaninquiringintoneo-liberalismasasingular‘thing’, thetri-partiteconceptionofferedhereallowsustoaddressneo-liberalism’scoherencebydealingwithitsdifferentfacesseparately.

Neo-liberalism’smostcoherentface—thatis,theclosestneo-liberalismcomes toaself-conscious,organizedandlogicallycoherentproject—isitsintellectual–professionalone.Underpinnedbyawell-troddensystemofeconomicthought andafaithinthepromiseof‘themarket’,intellectual–professionalneoliberalism’sadvancebyself-consciousknowledge-producingelitesconstitutesa simultaneouslymoral,politicalandprofessionalproject.Thecoherenceofthis faceisprobablyattributabletoitsmarginalizationfrommainstreampolitics and,consequently,itslonggestationintheintellectualfield.Itisalsoattributable toitslocuswithineconomics,wellnotedforbeinguniquelyinternationalized, rationalizedandpoliticallyinfluentialrelativetootherbranchesofthehuman sciences(Fourcade,2006).

Ontheotherhand,neo-liberalism’sexpressionsinpolicyandpoliticsareproducedattheintersectionoftheintellectual,politicalandbureaucraticrealms, generatingnotoneneo-liberalismbutmany neo-liberalisms.Theseexpressions arenotcoherentinthesenseofproducingidenticalpoliticallanguagesandpolicies,buttheyareanchoredbythesamecommonsense:theautonomousforceof themarket;thesuperiorityofmarketormarket-likecompetitionoverbureaucraciesasamechanismfortheallocationofresources.Thisdoesnotmeanthatall politicaleliteshavefullyacceptedthesepositions;itmeans,simply,thattheyhave difficultyarticulatingalternativesandstillretainingmainstreampoliticallegitimacy.Stateddifferently,itmeansthatpoliticalelitesofallstripesmust contendwiththebasicquestionof‘howmuchmarket’,asopposedtothe Keynesianeraquestionof‘howmuchstate’.

Howdoweunderstandandanalyseneo-liberalpoliticsinEuropeancontexts withstrongsocialistandsocialdemocratictraditions?Ratherthantakingpolitical elites’ownaccountsatfacevalue,apropermappingofpolitical‘neo-liberalisms’ shouldattendcloselytoinstitutionalconnectionsbetweenexperts,political actorsandstatebureaucracies.Onemightexpectthat,wherestatesaremore exposedtoanddependentonforeigncapitalandexpertise,neo-liberalism looksmorecoherent:think,forinstance,ofthe‘Washingtonconsensus’for

countriesoftheSouth,or‘shocktherapy’forthepost-CommunistEast. Athoroughmappingof‘neo-liberalisms’shouldalsotrace‘feedback’from therealmsofpolicyandpoliticsbackintotheintellectualfield,inwhichthe proliferationofpoliciesandpoliticaldiscoursesbecomefodderfornewscholarly articulations(likeWilliamson’s‘Washingtonconsensus’),whichthenhelpto crystallizethephenomenatheyclaimtomerelyobserve.

Byextension,weshouldexpectthatneo-liberalpoliticswouldlookfundamentallydifferentinrich,welfaristcountries,foratleasttworeasons.First,internationalorganizationsandforeignexpertisesexertambiguousinfluencesin, say,thedecisionofGermanpoliticalelitestopursuelabourmarketde-regulation. Thisdoesnotmeanthattheyplaynoroleatall,butratherthatassessing theirinvolvementrequiresthinkingcarefullyabouttheinstitutionalspecificities ofthecaseathand.AsecondsourceofdifferenceintheproductionofWestern ‘neo-liberalisms’islessobvious,butprobablymorecrucial:whereastheintersectionoftheintellectualandthepoliticalintheSouthandEastispopulatedby knowledge-producersrootedinWesternformsofexpertise,richWestern countriesareboththesourcesandtheobjectsofscholarlyinterventions.This constitutesasignificantwrinkleinourgazeontheintersectionoftheintellectual andthepoliticalinrichcountries,necessitatingadeeplyreflexivemodeof analysis:Westernscholarswouldhavetoturntheiranalyticalgazeonthemselves, assessingtheirownandtheirpeers’politicalroles.Thismaybeaprimaryreason that,asthisarticlehasargued,ourgraspofneo-liberalism’sexpressions isprobablyweakest inrichWesterndemocracies—andparticularlythosewithstrong socialdemocratictraditions.

TheauthorthanksPeterMairforhelpfulcommentsonanearlierversionofthis paper.TheauthoralsothanksSvenSteinmo,NeilFligstein,SamLucas,Margaret Weir,MarionFourcade,IsaacMartin,BasakKus,TomMedvetz,Brigitte LeNormand,DavidMcCourt,myfellowMaxWeberFellows,andthreeanonymousreviewersforthe Socio-EconomicReview forcommentaryandcritical insights.SupportwasprovidedbytheMaxWeberProgrammeoftheEuropean UniversityInstitute(EUI),aswellastheSurveyResearchCenter,theInstitute forResearchonLaborandEmploymentandtheDepartmentofSociologyat theUniversityofCalifornia,Berkeley.

References

Abbott,A.(1988) TheSystemofProfessions:AnEssayontheDivisionofExpertLabor, Chicago,IL,UniversityofChicagoPress. Mudge:whatisneo-liberalism?725

Babb,S.(2004) ManagingMexico:EconomistsfromNationalismtoNeoliberalism, Princeton,NJ,PrincetonUniversityPress.

Block,F.(2001)‘Introduction’.InPolanyi,K.(ed) TheGreatTransformation:ThePolitical andEconomicOriginsofOurTime,Boston,MA,BeaconPress,pp.pxviii–xxxviii.

Block,F.andSomers,M.(2003)‘IntheShadowofSpeenhamland:SocialPolicyandthe OldPoorLaw’, PoliticsandSociety, 31,283–323.

Block,F.andSomers,M.R.(2005)‘FromPovertytoPerversity:Ideas,Markets,andInstitutionsover200YearsofWelfareDebate’, AmericanSociologicalReview, 70,260–287.

Bockman,J.(2007)‘TheOriginsofNeoliberalismbetweenSovietSocialismandWestern Capitalism:“Agalaxywithoutborders”’, TheoryandSociety, 36,343–371.

Bockman,J.andEyal,G.(2002)‘EasternEuropeasaLaboratoryforEconomicKnowledge: TheTransnationalRootsofNeoliberalism’, AmericanJournalofSociology, 108,310–352.

Boix,C.(2000)‘PartisanGovernments,theInternationalEconomy,andMacroeconomic PoliciesinAdvancedNations,1960–93’, WorldPolitics, 53,38–73.

Bourdieu,P.(1992) TheLogicofPractice,Stanford,CA,StanfordUniversityPress.

Bourdieu,P.(1994)‘RethinkingtheState:GenesisandStructureoftheBureaucraticField’, SociologicalTheory, 12,1–18.

Bourdieu,P.(2005) TheSocialStructuresoftheEconomy,Cambridge,UKandMalden,MA, PolityPress.

Bourdieu,P.andWacquant,L.(1992) AnInvitationtoReflexiveSociology,Chicago,IL, UniversityofChicagoPress.

Bourdieu,P.andWacquant,L.(1999)‘OntheCunningofImperialistReason’, Theory, CultureandSociety, 16,41–58.

Brown,W.(2003)‘Neo-liberalismandtheEndofLiberalDemocracy’, TheoryandEvent, 7,accessedathttp://muse.jhu.edu/journals/theory_and_event/v007/7.1brown.html onJuly8,2008.

Cafruny,A.W.andRyder,M.(eds)(2003) ARuinedFortress?NeoliberalHegemonyand TransformationinEurope,Oxford,UK,Rowman&Littlefield.

Campbell,J.L.andPedersen,O.K.(eds)(2001) TheRiseofNeoliberalismandInstitutional Analysis,Princeton,NJ,PrincetonUniversityPress.

Cerny,P.G.(1993) FinanceandWorldPolitics:Markets,Regimes,andStatesinthePosthegemonicEra,Aldershot,Hants,UKandBrookfield,VT,EdwardElgar.

Chubb,J.E.andMoe,T.M.(1990) Politics,MarketsandAmerica’sSchools,Washington, DC,BrookingsInstitutionPress.

Cockett,R.(1995) ThinkingtheUnthinkable:Think-TanksandtheEconomicCounterRevolution,1931–1983,London,HarperCollins.

Cox,R.H.(2001)‘TheSocialConstructionofanImperative:WhyWelfareReform HappenedinDenmarkandtheNetherlandsbutNotinGermany’, WorldPolitics, 53, 463–498.

Crouch,C.(1997)‘TheTermsoftheNeo-liberalConsensus’, ThePoliticalQuarterly, 68, 352–360.

Dalton,R.J.andWattenberg,M.P.(eds)(2002) PartiesWithoutPartisans:PoliticalChange inAdvancedIndustrialDemocracies,Oxford,UK,OxfordUniversityPress.

Davis,A.F.(1964)‘SocialWorkersandtheProgressiveParty’, TheAmericanHistorical Review, 69,671–688.

Dezalay,Y.andGarth,B.(1998)‘SociologyoftheHegemonyofNeoliberalism’, Actesdela RechercheenSciencesSociales, 121,3–22.

Dezalay,Y.andGarth,B.(2002) TheInternationalizationofPalaceWars:Lawyers,Economists,andtheContesttoTransformLatinAmericanStates,Chicago,IL,andLondon, UniversityofChicagoPress.

Dezalay,Y.andGarth,B.(2006)‘TheNationalUsagesofaGlobalScience:TheInternationalDiffusionofNewEconomicParadigmsasBothHegemonicStrategyand ProfessionalStakeswithintheNationalFieldsofReproductionofStateElites’, Sociologie DuTravail, 48,308–329.

Dobbin,F.,Simmons,B.andGarrett,G.(2007)‘TheGlobalDiffusionofPublicPolicies: SocialConstruction,Coercion,Competition,orLearning?’, AnnualReviewofSociology, 33,449–472.

Durkheim,E.(2001[1912]) TheElementaryFormsofReligiousLife,Oxford,UK,and NewYork,OxfordUniversityPress.

Esping-Andersen,G.(1990) TheThreeWorldsofWelfareCapitalism,Princeton,NJ, PrincetonUniversityPress.

Esping-Andersen,G.(1994)‘WelfareStatesandtheEconomy’.InSmelser,N. andSwedberg,R.(eds) TheHandbookofEconomicSociology,Princeton,NJ,Russell SageFoundation.

Esping-Andersen,G.(1997)‘AftertheGoldenAge?WelfareStateDilemmasinaGlobal Economy’.InEsping-Andersen,G.(ed) WelfareStatesinTransition:NationalAdaptationsinGlobalEconomies,London,Sage,pp.1–32.

Esping-Andersen,G.(1999) TheSocialFoundationsofPostindustrialEconomies,Oxford, UK,OxfordUniversityPress.

Esping-Andersen,G.(ed)(2002) WhyWeNeedaNewWelfareState,Oxford,UK,Oxford UniversityPress.

Evans,P.(2005)‘CounterhegemonicGlobalization:TransnationalSocialMovementsinthe ContemporaryGlobalEconomy’.InJanoski,T.,Alford,R.R.andHicks,A.M.(eds) The HandbookofPoliticalSociology,Cambridge,UK,CambridgeUniversityPress.

Farrell,W.E.(1983,October24)‘“Neoliberals”inNeedofConstituents’, TheNewYork Times,NewYork,NY,p.8.

Fiorina,M.P.(2002)‘PartiesandPartisanship:A40-YearRetrospective’, PoliticalBehavior, 24,93–115.

Fourcade,M.(2006)‘TheConstructionofaGlobalProfession:TheTransnationalization ofEconomics’, AmericanJournalofSociology, 112,145–194.

Fourcade-Gourinchas,M.andBabb,S.L.(2002)‘TheRebirthoftheLiberalCreed:Paths toNeoliberalisminFourCountries’, AmericanJournalofSociology, 108,533–579.

Fourcade,M.andHealy,K.(2007)‘MoralViewsofMarketSociety’, AnnualReviewof Sociology, 33,285–311.

FraserInstitute(2004)‘TheFraserInstituteat30:ARetrospective’,Vancouver,BC,The FraserInstitute.

Friedman,M.andFriedman,D.R.(1980) FreetoChoose:APersonalStatement,London, SeckerandWarburg.

Friedrich,C.J.(1955)‘ThePoliticalThoughtofNeo-Liberalism’, AmericanPoliticalScience Review, 49,509–525.

Greenhouse,S.(1993January10)‘TheNewPresidency:TheLaborDepartment;Nominee DevotedYearsToRehearsingforRole’, TheNewYorkTimes,NewYork,NY,Sunday,Late Edition—Final,Section1;p.18;Column1;NationalDesk.

Green-Pedersen,C.,vanKersbergen,K.andHemerijck,A.(2001)‘Neo-liberalism,the “thirdway”orWhat?RecentSocialDemocraticWelfarePoliciesinDenmarkandthe Netherlands’, JournalofEuropeanPublicPolicy, 8,307–325.

Gunderson,M.(1989)‘Review:Freedom,DemocracyandEconomicWelfare,editedby MichaelA.Walker,Vancouver,theFraserInstitute,1988’, RelationsIndustrielles, 44, 465–466.

Gwartney,J.(2007)‘EconomicFreedomoftheWorld:2007AnnualReport’,accessedat http://www.freetheworld.com/datasets_efw.htmlonJuly8,2008.

Gwartney,J.andLawson,R.(2005)‘EconomicFreedomoftheWorld:2005Annual Report’,Vancouver,BC,TheFraserInstitute,accessedathttp://www.freetheworld. com/datasets_efw.htmlonJuly8,2008.

Hale,J.F.(1995)‘TheMakingoftheNewDemocrats’, PoliticalScienceQuarterly, 110, 207–232.

Hall,P.(ed)(1989) ThePoliticalPowerofEconomicIdeas:KeynesianismacrossNations, Cambridge,MA,HarvardUniversityPress.

Hall,P.A.andSoskice,D.(2001) VarietiesofCapitalism:TheInstitutionalFoundationsof ComparativeAdvantage,Oxford,UK,OxfordUniversityPress.

Hanley,E.,King,L.andJanos,I.T.(2002)‘TheState,InternationalAgencies,andPropertyTransformationinPostcommunistHungary’, AmericanJournalofSociology, 108, 129–167.

Harvey,D.(1989) TheConditionofPostmodernity,Oxford,UK,BasilBlackwell.

Harvey,D.(2005) ABriefHistoryofNeoliberalism,Oxford,UK,OxfordUniversityPress.

Hausman,D.H.andMcPherson,M.(2006) EconomicAnalysis,MoralPhilosophyand PublicPolicy,2ndedn,Cambridge,UK,CambridgeUniversityPress.

Hay,C.(2004)‘TheNormalizingRoleofRationalistAssumptionsintheInstitutional EmbeddingofNeoliberalism’, EconomyandSociety, 33,500–527.

Hayek,F.A.(1978[1960]) TheConstitutionofLiberty,Chicago,IL,UniversityofChicago Press.

Hayek,F.A.(1994[1944]) TheRoadtoSerfdom.FiftiethAnniversaryEdition,Chicago,IL, UniversityofChicagoPress.

Hayek,F.A.(2007[1944]) TheRoadtoSerfdom:TextandDocuments—TheDefinitive Edition,Chicago,IL,UniversityofChicagoPress.

Henisz,W.J.,Zelner,B.A.andGuillen,M.F.(2005)‘TheWorldwideDiffusionofMarketorientedInfrastructureReform,1977–1999’, AmericanSociologicalReview, 70,871–897.

Hetherington,M.J.(2001)‘ResurgentMassPartisanship:TheRoleofElitePolarization’, AmericanPoliticalScienceReview, 95,619–631.

Holmes,D.R.(2000) IntegralEurope:Fast-Capitalism,MulticulturalismandNeofascism, Princeton,NJ,andOxford,UK,PrincetonUniversityPress.

IDU(2005)‘WashingtonDeclaration’,July18,Washington,DC.

Kay,C.(2007)‘FromPinochettothe“ThirdWay”:NeoliberalismandSocialTransformationinChile’, JournalofLatinAmericanStudies, 39,412–413.

Kelly,J.L.(1997) BringingtheMarketBackin:ThePoliticalRevitalizationofMarket Liberalism,NewYork,NewYorkUniversityPress.

King,L.P.andSzele ´ nyi,I.(2004) TheoriesoftheNewClass:IntellectualsandPower, Minneapolis,MN,UniversityofMinnesotaPress.

Krippner,G.R.(2007)‘TheMakingofUSMonetaryPolicy:CentralBankTransparency andtheNeoliberalDilemma’, TheoryandSociety, 36,477–513.

Krippner,G.R.andAlvarez,A.S.(2007)‘EmbeddednessandtheIntellectualProjectsof EconomicSociology’, AnnualReviewofSociology, 33,219–240.

Krippner,G.,Granovetter,M.,Block,F.,Biggart,N.,Beamish,T.,Hsing,Y.T.,Hart,G., Arrighi,G.,Mendell,M.,Hall,J.,Burawoy,M.,Vogel,S.andO’Riain,S.(2004) ‘PolanyiSymposium:AConversationonEmbeddedness’, Socio-EconomicReview, 2, 109–135.

Lemke,C.andMarks,G.(1992) TheCrisisofSocialisminEurope,Durham,NC,Duke UniversityPress.

Levy,J.D.(2001)‘PartisanPoliticsandWelfareAdjustment:TheCaseofFrance’, Journalof EuropeanPublicPolicy, 8,265–285.

Leys,C.(1997)‘TheBritishLabourPartysince1989’.InSassoon,D.(ed) LookingLeft. EuropeanSocialismaftertheColdWar,LondonandNewYork,IBTaurisPublishers. Martin,J.L.(2003)‘WhatisFieldTheory?’, AmericanJournalofSociology, 109,1–49.

Martin,I.(2008) ThePermanentTaxRevolt:HowthePropertyTaxTransformedAmerican Politics,Stanford,CA,StanfordUniversityPress.

Massey,D.S.,Sanchez,R.M.andBehrman,J.R.(2006)‘OfMythsandMarkets’, The AnnalsoftheAmericanAcademyofPoliticalandSocialScience, 606,8–31.

Medvetz,T.(2007) ThinkTanksandtheProductionofPolicyKnowledgeinAmerica, UnpublishedPhDDissertation,Berkeley,CA,UniversityofCalifornia.

Meyer,J.W.andRowan,B.(1991)‘InstitutionalizedOrganizations:FormalStructureas MythandCeremony’.InPowell,W.P.andDiMaggio,P.J.(eds) TheNewInstitutionalism inOrganizationalAnalysis,Chicago,IL,UniversityofChicagoPress,pp.41–62.

Nelson,R.H.(2001) EconomicsasReligion:FromSamuelsontoChicagoandBeyond,State College,PA,PennsylvaniaStateUniversityPress.

Pierson,P.(1994) DismantlingtheWelfareState,Cambridge,UK,CambridgeUniversity Press.

Pierson,P.(1996)‘TheNewPoliticsoftheWelfareState’, WorldPolitics, 48,143–179.

Polanyi,K.(2001[1944]) TheGreatTransformation:ThePoliticalandEconomicOriginsof OurTime,Boston,MA,BeaconPress.

Pontusson,J.(1992) TheLimitsofSocialDemocracy:InvestmentPoliticsinSweden,Ithaca, NY,CornellUniversityPress.

Pontusson,J.(1994)‘Sweden:AftertheGoldenAge’.InAnderson,P.andCamiller,P.(eds) MappingtheWestEuropeanLeft,London,Verso,pp.23–54.

Power,M.(2005)‘VictimsoftheChileanMiracle:WorkersandNeoliberalisminthe PinochetEra,1973–2002’, LatinAmericanPoliticsandSociety, 47,199–203.

Prasad,M.(2006) ThePoliticsofFreeMarkets:TheRiseofNeoliberalEconomicPoliciesin Britain,France,GermanyandtheUnitedStates,Chicago,IL,UniversityofChicagoPress.

Quinn,D.P.andToyoda,A.M.(2007)‘IdeologyandVoterPreferencesasDeterminantsof FinancialGlobalization’, AmericanJournalofPoliticalScience, 51,344–363.

Rodgers,D.T.(1998) AtlanticCrossings:SocialPoliticsinaProgressiveAge,Cambridge, MA,HarvardUniversityPress.

Roosevelt,F.D.(1941) AnnualAddresstoCongress,HydePark,NY,FranklinD.Roosevelt PresidentialLibraryandMuseum.

Ro ¨ pke,W.(1996[1948]) TheMoralFoundationsofCivilSociety,NewBrunswick,NJ,and London,TransactionPublishers.

Rueschemeyer,D.andSkocpol,T.(1996) States,SocialKnowledgeandtheOriginsof ModernSocialPolicies,Princeton,NJ,andNewYork,PrincetonUniversityPressand theRussellSageFoundation.

Sassoon,D.(1996) SocialDemocracyattheHeartofEurope,London,InstituteforPublic PolicyResearch.

Sassoon,D.(ed)(1997) LookingLeft:EuropeanSocialismaftertheColdWar,London, NewYork,Rome,IBTaurisPublishersandTheGramsciFoundation.

Simmons,B.A.,Dobbin,F.andGarrett,G.(2006)‘Introduction:TheInternational DiffusionofLiberalism’, InternationalOrganization, 60,781–810.

Smith,J.A.(1993) TheIdeaBrokers:ThinkTanksandTheRiseofTheNewPolicyElite, NewYork,TheFreePress.

Steinmo,S.,Thelen,K.andLongstreth,F.(eds)(1992) StructuringPolitics:Historical InstitutionalisminComparativePerspective,Cambridge,UK,CambridgeUniversity Press.

Stiglitz,J.E.(2002) GlobalizationandItsDiscontents,NewYorkandLondon,W.W.Norton andCompany.

Stone-Sweet,A.andSandholtz,W.(eds)(1999) EuropeanIntegrationandSupranational Governance,Oxford,UK,OxfordUniversityPress.

Stone-Sweet,A.,Sandholtz,W.andFligstein,N.(eds)(2001) TheInstitutionalizationof Europe,Oxford,UK,OxfordUniversityPress.

Szajkowski,B.(ed)(2005) PoliticalPartiesoftheWorld,London,JohnHarperPublishing Inc.

Teles,S.andKenney,D.A.(2008)‘SpreadingtheWord:TheDiffusionofAmericanConservatisminEuropeandBeyond’.InKopstein,J.andSteinmo,S.(eds) GrowingApart? AmericaandEuropeinthe21stCentury,Cambridge,UK,andNewYork,Cambridge UniversityPress.

Therborn,G.(2007)‘AfterDialectics:RadicalSocialTheoryinaPost-CommunistWorld’, NewLeftReview, 43,63–114.

Valdes,J.G.(1995) Pinochet’sEconomists:TheChicagoSchoolinChile,Cambridge,UK, CambridgeUniversityPress.

vanApeldoorn,B.,Overbeek,H.andRyner,M.(2003)‘TheoriesofEuropeanIntegration: ACritique’.InCafruny,A.W.andRyner,M.(eds) ARuinedFortress?NeoliberalHegemonyandTransformationinEurope,Oxford,UK,RowmanandLittlefield,pp.17–46.

Visser,J.andHemerijck,A.(1997) ADutchMiracle:JobGrowth,WelfareReform CorporatismintheNetherlands,Amsterdam,AmsterdamUniversityPress.

Vogel,S.K.(1996) FreerMarkets,MoreRules:RegulatoryReforminAdvancedIndustrial Countries,Ithaca,NY,andLondon,CornellUniversityPress.

Weyland,K.(1999)‘NeoliberalPopulisminLatinAmericaandEasternEurope’, ComparativePolitics, 31,379–401.

Williamson,J.(1990)‘WhatWashingtonMeansbyPolicyReform’.InWilliamson,J.(ed) LatinAmericanAdjustment:HowMuchHasHappened?,Washington,DC,Institutefor InternationalEconomics.

Williamson,J.(1993)‘Democracyandthe“WashingtonConsensus”’, WorldDevelopment, 21,1329–1336.

Woolley,J.T.(1982)‘MonetaristsandthePoliticsofMonetaryPolicy’, Annalsofthe AmericanAcademyofPoliticalandSocialScience, 459,148–160.

Young,C.(2005)‘ThePolitics,MathematicsandMoralityofEconomics:AReviewEssay onRobertNelson’sEconomicsasReligion’, Socio-EconomicReview, 3,161–172. Mudge:whatisneo-liberalism?731