https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02359-y

Eve of extinction

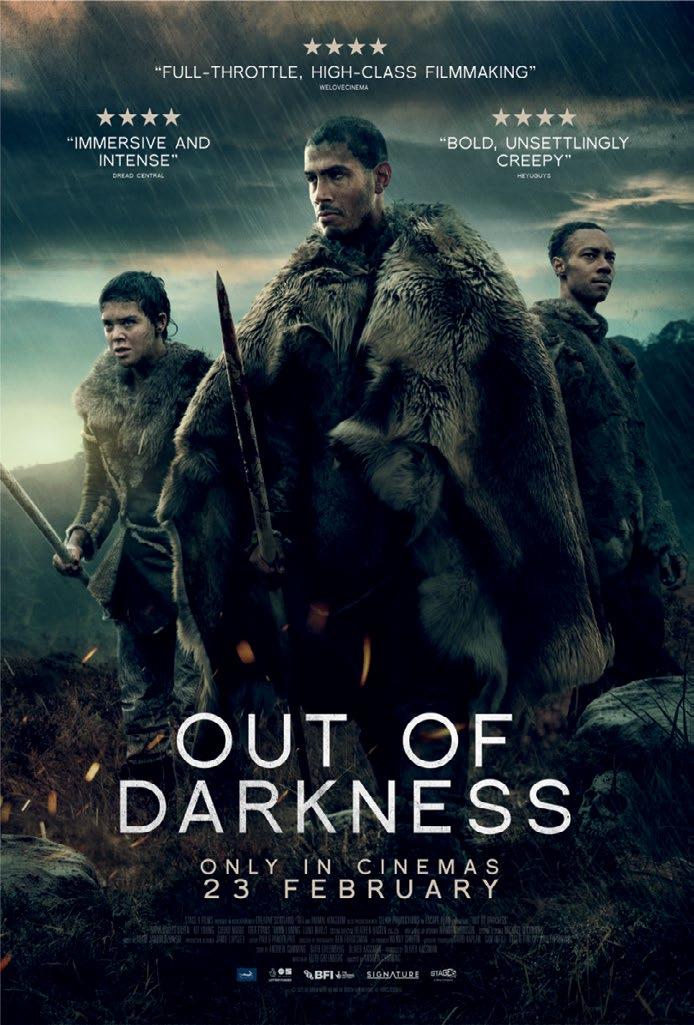

Set 45,000 years ago, Out of Darkness begins with a band of six modern humans (Homo sapiens) telling stories by firelight. Subtly, this opening scene reflects current palaeoanthropological theory by establishing fire as a leading character in the human story — providing warmth in glacial landscapes; light for evening storytelling; and a defence against unseen threats. But there is “danger in bringing light to dark places”, explains Odal, the group’s spiritual leader. “You might find out what lies in the darkness.”

It is clear from the outset that Out of Darkness is no ordinary survivalist thriller. It transcends the genre, leaning heavily on Platonic philosophy while criticizing self-serving narratives of settler colonialism and organized religion (at times more subtly than others — two of the leads are Adem and Eva, with Adem declaring early on that “I am the light”). The filmmakers also collaborated closely with an archaeologist (R. Dinnis, University of Aberdeen) and a linguist (D. Andersson, Umeå University). The intent was to enhance the authenticity of their film, but they achieved something altogether fresh and original at the same time: a horror film that entertains and educates simultaneously.

Exemplifying this commitment is the bold decision to script the dialogue in ‘Tola’, a language that was invented for the film. Tola combines Arabic with Basque (Euskera), and draws on research that recognizes Euskera as the oldest living European language. A language isolate, Euskera has been spoken for at least 12,000 years1, which long pre-dates the origin of Indo-European languages about 8,100 years ago2. Its distinctiveness — even when combined with the familiar rhythms of modern Arabic — gives Tola a grammar and phonology that will be unfamiliar to most viewers.

The use of Tola creates a curious tension. It ‘others’ our Palaeolithic predecessors while conferring in-group membership — having language is to be ‘like us’ according to Heron, Adem’s 11-year-old son. Many palaeoanthropologists would agree, viewing language as a criticalfactorintheriseandspreadofH.sapiens (including our expansion into northern Europe about 45,000 years ago)3. The hypothesized advantages of language are expressed throughout the film, and illustrate key moments of

identity and status, culture and storytelling, deception and revelation. But language can break bonds as much as it strengthens them, and the tightknit group begins to fracture.

An unknown horror —an ‘animal’, ‘demon’ or ‘monster’ — has begun tracking them.

The inhospitable setting only enhances the menace. Scottish director A. Cumming chose the stark mountains of the Gairloch coastline in north-west Scotland to create a barren, hostile landscape — but only for the uninitiated. This eerie sensation is magnified by the stunning cinematography of B. Fordesman and the beautiful, if haunting, score by A. Janota Bzowski, who used replica bone flutes and other Palaeolithic instruments. The result is exquisite and sets a new standard for the horror genre.

[Spoiler alert — skip to the final paragraph to avoid detailed plot discussion]. Gairloch was well chosen. Some researchers view rugged mountainous terrain as the principal habitat and stronghold of Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), and to explain both their limb proportions4 and terminal presence in Europe5 — albeit not in Scotland: there is currently no

evidence for hominins in Scotland until after the Last Glacial Maximum. The final act unfolds in three pivotal moments that begin with the humans’ discovery of Neanderthals among them. This revelation reverses the roles of hunter and hunted, and it impels the humans to track their quarry towards a distant cave.

Initially, we see the Neanderthals’ cave in darkness and shadow, as a setting for deadly conflict, but then it reveals unmistakable signs of domestic life (including evidence of controlled fire and symbolic culture). It also reveals a tragic misunderstanding. The climax of the film is a defining moment that reveals and denies the Neanderthals’ humanity, along with a human reaction that is both inhumane and all too familiar.

For Darwin, controlled fire was “the greatest [discovery] made by man, excepting language”, and it is natural to ask whether Neanderthals possessed these same abilities. It is a topic of enduring debate at a tipping point, with mounting evidence of hearth fires6, spoken language7 and symbolic culture8. These findings are reshaping our view of Neanderthals, and their integration into Out of Darkness is an outstanding example of how the combination of science and art can elevate and enrich the stories we tell. At the same time, the film ends by touching on novel themes for most horror films: enlightenment, colonization and indigeneity. Indeed, the final scene seems intended as a subversive interpretation of Plato’s ‘Allegory of the Cave’. In Platonic philosophy, the enlightened human being — with privileged access to fire and language — would have a moral obligation to enter caves and take those imprisoned inside ‘out of darkness’, and to do so by force if necessary. But what if the darkness is created by our own intolerance? If the Anthropocene is an epoch of extinction, then Out of Darkness implies that it may have started 45,000 years ago with the elimination of H. neanderthalensis. The film raises the question: what if we are the monsters in a horror story of our own making?

Reviewed by Catherine Hobaiter 1 & Nathaniel J. Dominy 2

1University of St Andrews, St Andrews, UK. 2Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA.

e-mail: clh42@st-andrews.ac.uk; nathaniel.j.dominy@dartmouth.edu

Books & arts

Published online: 26 February 2024

References

1. Trask, R. L. The History of Basque (Routledge, 1997).

2. Heggarty, P. et al. Science 381, eabg0818 (2023).

3. Mylopotamitaki, D. et al. Nature 626, 341–346 (2024).

4. Higgins, R. W. & Ruff, C. B. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 146, 336–345 (2011).

5. Henry, D. O., Belmaker, M. & Bergin, S. M. Quat. Int. 435, 94–105 (2017).

6. Allué, E. et al. in Updating Neanderthals: Understanding Behavioural Complexity in the Late Middle Palaeolithic (eds Romagnoli, F. et al.) 227–249 (Academic, 2022).

7. Dediu, D. & Levinson, S. C. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 21, 49–55 (2018).

8. Nielsen, M., Langley, M. C., Shipton, C. & Kapitány, R. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 375, 20190424 (2020).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.