1InstitutdeRechercheInterdisciplinaireenSciencesSociales,UniversitéParis-Dauphine,Paris, Franceand 2CentreofAfricanStudies,UniversityofEdinburgh,Edinburgh,UK

Emails: james-christopher.mizes@dauphine.psl.eu,kevin.donovan@ed.ac.uk

In2016,thecityofCapeTownhostedthefourteenthannualmeetingoftheAfrican CapitalMarketsConference.Eachyear,theconferenceassembles ‘Africansovereigns, corporates,regulators,localandinternationalinvestors,andfinancialserviceproviderswithinterestinfosteringthediversityofinvestmentandfundingoptions vialocalcapitalmarkets’ (IMN 2016).Theconferencebeganin2002and,atthetime, limiteditsgeographicfocustocapitalmarketsinSouthAfrica.Butin2012,theconferenceshifteditsapproachto ‘includeallofAfrica’ andtoemphasizea ‘particular focusonemergingmarketsinSub-SaharanAfrica’ (ibid.).Indeed,itsexpandinggeographicfocusaccompaniedanimportanttransformationinAfricancapitalatthe time:agrowingnumberofstockexchangesandprivateequityfirmswerespringing upacrossthecontinent,andagrowingnumberofAfricaninvestors,governmentsand firmswerestartingtousethem.

TheriseofAfricancapitalmarketsisanimportantfeatureofglobalfinanceinthe newmillennium.AlthoughEuro-Americandevelopmentinstitutionscontinuetooffer financialproductsacrossthecontinent,theseinstitutionshavetransformedhowthey understandtheproblemofeconomicdevelopmentandarenowproposinganewgenerationofsolutionstoit.Inthepasttwentyyears,internationalaidorganizations haveincreasinglyturnedtowardsAfricanstockmarkets,ratingsagenciesandcommercialbankstofinanceprojectsacrosssectors.Butthecontinent’sprivatesectorhas beenmoreforcefullyleadingthisexpansionbyintroducingnewwaystomeasurerisk, newdebtinstruments,andnewrolesforgovernmentintheregulationofanemerging financialindustry.ThisshifthasbeensimilarlyencouragedbyAfricaninvestors’ increasingopennesstofinancialassetsdenominatedinlocalcurrenciesandissued byAfricangovernmentsandfirms.FromfuturesmarketstoBitcoin,sovereignbonds tocreditscores,thecontinent – andespeciallyitsleadingcitiessuchasAbidjan, Nairobi,LagosandJohannesburg – ishometoaproliferationofsuchfinancialdevices. Buttheprecisecausesandconsequencesofthistransformationarenotyetclear.

Forcritics,thegrowthofcapitalinvestmentacrossthecontinentisanother instanceofaglobalformoffinancializationinwhichEuro-Americancapitalisonce againforcingAfricanstatesintodebtdependency(Kvangraven etal. 2021).Fromthis perspective,theexpansionofsovereignbondissuancesonEuropeanandAmerican ©TheAuthor(s),2022.PublishedbyCambridgeUniversityPressonbehalfoftheInternationalAfricanInstitute

stockexchangesisunderstoodasashiftin – butcontinuationof – olderformsof Africa’seconomicsubordinationanddependence.Theextentofthis ‘financialdeepening’ issuchthatStiglitzandRashid(2013)issuedawarningthatAfricansovereign debtwasatanhistorichighandthatpaymentsfromthesebondsweresooncoming due.Thiswas,intheirview,aharbingerofanewroundofsovereigndefaultsechoing thoseofpriordecades.Suchaconcernwasonlyheightenedasthisissuewenttopress amidstincreaseddebtdistressdue,inpart,toforeigninvestorspullingcapitaloutof theglobalSouthinresponsetointerestratechangesinEuro-America.Othershave pointedtotheroleofAmericancreditagenciesinrubberstampingrecklessborrowingandthereforeincentivizingaloomingfinancialcatastrophe(Chelwa 2020).And DanielaGabor(2021)hascoinedatermtosummarizethisseriesofnefariousevents: the ‘WallStreetConsensus’.AccordingtoGabor,globaldevelopmentbanksaretoday workingin ‘technocraticforumsawayfrompublicscrutiny’ to ‘enlist’ statesto ‘assumethedemandrisk’ onnewfinancialassets –‘de-risking’ forthebenefitofprivateinstitutionalinvestors(ibid.:440–7).

YetmanyAfricanofficials,professionalsandinvestorsunderstandfinancein starklydifferentterms.Intheirvision,capitalmarketsarepartofanewchapter ofAfricanhistoryinwhicheconomicself-determinationisachievedthroughtheharnessingofmoneythathaslongbeencontrolledbyforeignfinanciers.Ratherthana pernicioustrend,itisanopportunitytoputAfricanmoneytoworkforAfricans.Itis anaspirationthatisoftenexplicitlypan-African.Forexample,theAfricanUnion envisionsitsfinancialfutureintermsofAfricancapitalmarkets,andcreditrating agenciesandbanksacrossthecontinenthavelongunderstoodtheirmarketspace asdistinctively ‘pan-African’.Formanyofthesefinancialactors,theaimistowrest developmentplanningandcapitalallocationawayfromEuro-Americanfinancial institutionsandputtheminAfricanhands(Mizes 2016).Here,capitalmarkets,currencyswapsandfinancialaccountingappearnotasaformofdependence,butasa pathwaytoindependenceandsovereignty(MbengMezui 2017).Inotherwords,many ofthesetransformationsmaynothavemuchtodowith ‘WallStreet’,noristhereany global ‘ consensus ’ onhowtoorganizeandexpandAfricancapitalanditsmarkets.

Thisspecialissuemovesbeyondtheseduellingviews.Ratherthancelebrateor denouncetheseongoingfinancialtransformations,thearticlescollectedheretake financeinAfricaasafieldofanthropologicalinquiry.Theyinvestigatethesocial worldsoffinance,itstechnicaldevices,andthemundanemannerinwhichforms ofcapitalarebeingcomposed.Theyforegroundthemoraldisagreementsoverthe emerginginfrastructuresofAfricancapitalmarkets,andtheyanalysehowthese debatestakeshapearoundadiverserangeofspecificfinancialdevices:privatization, creditscoring,shareholderassociations,foreignexchangeregulationsandbankbailouts.Inplaceofbroadpredictionsontheinevitablefalloutsoffinance,ourcontributorsexplorenewmodesofpopularandprofessionalreasoningaboutfinancein AfricabyAfricans,andtheirspecificstrugglesoverhowtoknow,valueandmanage capital.

Whilethisissuedrawsonexemplarycasesfromacrossthecontinent,italsoanalysesadistinctlyglobaltransformation.Scholarsoffinancehavepreviouslyfocused theiranalysison ‘commandandcontrolcenters’ locatedin ‘globalcities’ suchas Tokyo,LondonandNewYork(Sassen 1991).Fromthisperspective,financialcentres are ‘global’ inthesensethattheirinfluenceextendsoutwardtostructuresocialand

economiclifeacrosstheworld.Intheseapproaches,placessuchasAbidjanandAccra aresubjecttothevicissitudesandpoweroffinancialactors – hedgefunds,consulting firms,insurancecompanies,creditratingagencies – largelylocatedoutsidethecontinentandlookingfornewinvestmentopportunitieswithinit(seeMawdsley 2018; Ouma 2020b;Roitman 2021).Asaresult,theactivitiesandaspirationsofAfricansparticipatinginthecontinent’sownfinancialindustryhavelargelyrecededfromscholarlyview.

Inthisissue,weplacethegeographyofAfricanfinancetodayinadifferentframe: ourapproachlinkstheflowofAfricanfinancialexpertisetotheflowofmoneyin,out andacrossthecontinent(cf.MontagneandOrtiz 2013),flowsthattogetherconstitute – andcanpotentiallyreconfigure – Africa’sroleinthe ‘worldsystem’.Weanalysehow Africanprofessionalsaretranslatingfinancialdevicesfromoutsidethecontinentto fitthemoraldilemmas,politicalstylesandeconomicpracticesfoundwithinit(Ong andCollier 2007;Guyer 2004).Manyoftheseprofessionalsareclaimingtoharness capitaltomeetAfricanneedsandopposeWesterncontrolofAfrica’sfuture.They oftenexplicitlyframetheseclaimsintheidiomofpan-Africancommerce.Asaresult, themoralvisionofaunitary ‘Africa’ isonceagainemergingasawaytoframeefforts atpromotingintra-Africanexchangeandreversingtheglobalflowofwealthoutof thecontinent.Atstakeinthisreversalistherelocationof ‘commandandcontrol’ centresfromLondonandNewYorktotheemergingfinancialcentresinAfrica’scities. ThefutureofAfricancapitalisfarfromcertain;indeed,financialanalyststhemselves ‘oftenfailtopredictthecorrectfuturedevelopmentsoffinancialmarkets’ (Leins 2018:4).Thearticlescollectedinthisissueof Africa provideinsightintothe diverselocationsinwhichthisfutureisbeingmadeanddisputed.Inthisintroductory article,webringawide-anglelenstotheserecenttransformationsandthenear futuresofAfricanfinancethattheyanticipate.Why,forsomany,hasAfricanpolitical liberationbecomeataskoffinancialengineering?AndwhyhavesomeAfricans’ aspirationsfordevelopmenttodayreturnedtoapromotionof ‘indigenous’ and ‘domestic’ finance?Toaddressthesequestions,webuildonourownethnographicresearch, readingsofkeyprogrammatictexts,analysesofrelatedscholarship,andthearticles collectedinthisissue.Withtheseresources,wesketchouthowtheproblemof Africaneconomicdevelopmentisbeingreframedtoday.Yetwealsoexaminethelimitsofthisreframingandthepotentiallycalamitousconsequencesofwhichmanycriticsarealreadytakingnote.

Priortocolonialism,inmuchofAfrica,systemsofproductionreliedmoreondomestic labour,tributaryexchangeandenslavedpeoplethanontheexploitationoffreewage labourers.However,capital – inthesenseofmoneyinvestedincommercialactivities thatareexpectedtocreatemorewealth – predatesthearrivalofEuropeanmerchants, slavetradersandcolonists.Therewaswidespreadprofit-orientedmerchantactivity, includingamongNorthAfricanandSaharantraders(Iliffe 1983:4–7)andlivelyoceanic exchangefromtheentrepôtsoftheSwahiliCoast(Austen 1987:58–60).When EuropeansbeganarrivinginAtlanticAfrica,theyencounteredmercantileenclaves whereIslamicsystemsofcredit,cowrieshellsandsilverwereused.Peopledrewon avarietyofformsofcredit,includingtherotatingYoruba esusu groups, Nanemei

Akpee usedbyGawomentraders,billsofexchange,orloansfromlandlordsandrulers (Austin 1993:101–5).OntheIndianOceanlittoral,prolificformsoflendingfacilitated thetradeindates,pearls,clovesandivory,aswellastheformationofa ‘multi-ethnic andmulti-confessionalcommercialsociety’ (Bishara 2017:59).

Yetwealthwasnotalwayscashorcommodity.Priortocolonization,Africans tendedtoplacevalueonfollowersanddependantsratherthanaccumulatingcapital asanenduringandfungibleformofwealth(GuyerandBelinga 1995).Inpart,this wasduetothepaucityoflabourcomparedwithlandinlargepartsoftheregionand becausemoneywasnotwidelystandardizedandrarelycentralizedinitsissuance.As aresult,wealthwasstoredinnon-pecuniary forms:landandlivestock,pre-eminently. Whilesomemoneydidreachgeneralpurposestanding(Hopkins 1973:70),moreemblematicwasthemultiplicityofmonies,valuedfor theirparticularmeaningsandaffordances: fromcoppermanillasandironbarstotextilesandbeads(GuyerandPallaver 2018).

Inmanycases,theviolentdisruptionsandeconomictransformationsofEuropean interventionsledtowidespreadlossofwealth.InsouthernandeasternAfrica,for example,livestockdiseaseandpurposefulcullingeliminatedhugestoresofsuch wealth.SettlerenclosureoflandandstatelimitsonAfricanagrarianproductionlikewiseinhibitedwidespreadcommodityproduction,letalonecapitalaccumulation (Kanogo 1987).AndinAtlanticAfrica,hardcurrencies(thatretainedvalueovertime) wereexported.Asaresult,capitalaccumulationbecameevermoreheavilyconcentratedinotherworldregions,suchthatbytheearlynineteenthcenturyAtlantic Africa’saccesstocapitalwasataseveredisadvantage(Green 2020).

Similarly,wagelabourandinvestmentinindustrialproductionexpandedonlyin fitsandstartsacrossthecontinent.Theywereoftenconcentratedininfrastructural corridors,commercialhubsandexportenclaves.Productionforthemarketremained dependentonexistingformsofdomesticproductionandthelabourofwomenand socialjuniors(Meillassoux 1981).CurrencieswereapotentformofgovernmentalcontroloverAfricans(Mwangi 2001),butcolonialeconomieswereoftenrackedbyvolatility,underminingconfidenceintheirproductivecapacities.Theimperial enforcementof ‘customary’ landregimesandderogatoryviewsofAfricanacumen combinedtoimpedelendingtofarmers(CowenandShenton 1991).Evenwhenmetropolitanproponentsof ‘soundfinance’ werecompelledtosupportdevelopmental investmentsinthecolonies,outputwasfrustratinglylimited.Viableindustrieswere few,andAfricanactivismoftenunsettledtheplansofgovernmentofficials.InKenya, forinstance,theMauMaurebellionjeopardizeddevelopmentspendingand ‘threatenedthefiscalstabilityofthecolony’ (Tignor 1998:330).

ThishelpsexplainthelackofcommercialcreditinmostAfricancolonies.Unlike, forinstance, ‘Britain’sveiledprotectorate’ inEgypt,whichsawastupendousincreasein banklendingdirectlytopeasant farmersintheearly1900s(Jakes 2020:84–112),financial servicesweremorelimitedincoloniessouthoftheSahara.Somelucrativeproductssuch asAsantecocoaattractedconsiderablecredit(intheformofadvancesandmortgages), frombothEuropeanandAfricanlenders(Austin 2005).BarclaysDCO(Dominion,Colonial andOverseas),theStandardBankofSouthAfricaandtheBankofBritishWestAfrica openedbranchesinmanyBritishcolonies, yetwhatcredittheyprovidedwasfocused ontheimportofBritishgoodsandtheexportofrawmaterials(Zwanenbergand King 1975:280–1).Theirloanswereshort-term,expensiveandfocusedonexpatriates (andsometimescommercialminorities,suchasEastAfrica’sSouthAsianpopulation).

WhilebankersoftendeemedAfricansunfitasborrowers(Uche 1996)andsettlers werewaryofnativecompetition,theconservativeturninimperialgovernanceadded anotherimpedimentaspaternalisticrulesandworriesaboutdisintegratingtradition blockedcommercialfinancetoAfricans(Shipton 2010:30–5).Colonialstatefinancing wasequallylacking,inpartduetotheexistenceofcurrencyboardsthatsubordinated colonialcurrenciestoBritishsterlingandtheFrenchfranc.Onlyinthewaningdaysof empiredidcurrencyboardsreceivetheauthoritytoofferseasonalcropfinancing,and eventhentheypursueditcautiously.Asaresult,bankingandcurrencywereobjects ofpopularfrustration,especiallyasdemandsforpoliticalindependencemergedwith economicaspirations(Donovan 2018).

Withindependence,manyAfricannationstatesbegancreatingtheirownbanks,their ownstockexchangesandtheirowncurrencies.Acrossthecontinent,postcolonial statesendeavouredtocraftpoliciesandinstitutionsthatwouldharnesscitizens’ labour,naturalresourcesandinternationaltradeinthedirectionof ‘economic independence’ (Ghai 1973;Getachew 2019).Asourcontributorsdiscuss,parastatal banksissuedcreditto ‘indigenous’ entrepreneursand,beginninginthe1970s,countriesprivatizedlargepublicservicestojumpstarttheirownnewlymintedstock exchanges.Yetwithinthisbroadpostcolonialvision,criticismsanddivisions emerged.Amarket-ledliberation,forexample,clashedwiththeideaofAfricansocialismandthecontinentalrealignmentstakingplacealongsidetheglobalColdWar.In manycases,EuropeancontroloverAfrica’sfinancialandmonetaryinstitutionspersistedlongafterformalpoliticalcontrolended(Gadha etal. 2021) – thisiswhat KwameNkrumah(1965)diagnosedas ‘neo-colonialism’ .

Afternationalindependence,commodityboomsincertaincountriesbroughtyears ofcommercialsuccessandadecidedlyunequaldistributionofitsmonetarygains (Arrighi 2002;Jerven 2014).Thequestionofdependencyloomedlarge,yetinsome casescapitalistproductionexpandedatthehandsoftheAfricanbourgeoisie. Oftenthiswasfurtheredbymoreorlessexplicitdrivesto ‘Africanize’ industry, includingthebankingsector(Bamba 2020).InKenya,thisbourgeoisieovercamea smalldomesticmarketandlowagriculturalproductivitytoestablishthemselves ascentralactorsinthelocalcompositionofAfricancapital(Swainson 1977). Similarly,inSenegal,Islamicleadersaccommodatedtheexport-orientedgrowthof thelocalpeanutindustryandtransformeditintoacosmopolitannetworkofmerchantsthatpersiststothisday(Diouf 2000).Nigerianentrepreneursexpandednot onlyinimport–exportindustriesandinagriculture,butinsectorssuchastransport, bankingandpackagedfoods(Forrest 1994).Thiscross-continentalsampleofferssubstantialreasontounderstandthattechniquesforthecompositionandcirculationof Africancapitalhavelongbeencreativelyinventedandrepurposedacrossthe continent.

The1980schallengedsuchaconception.Theendofpost-independencegrowthin the1970spromptedanewwaveofreflectionontheproblemofdevelopment.The OrganisationofAfricanUnity(OAU)publishedthe LagosPlan (1980),condemning the ‘exploitationarisingfromcolonialism,racism,andapartheid’ (ibid.:5)andadvancinginitsplace ‘afar-reachingregionalapproachbasedprimarilyoncollectiveself-

reliance’ (ibid.:4).Intra-Africantradeandthe ‘mobilisationofdomesticfinancial resources ’ (ibid.:69)emergedaskeyleversofthisresponsetotheinheritedproblems ofAfrica’sunderdevelopment.Incontrast,theWorldBankpublishedthenowfamous ‘BergReport’ (WorldBank 1981),whichsubsequentlysettheintellectualagendafor addressingthecontinent’ s ‘economicdevelopmentproblems’ byforcefullyforegroundingthedevelopmentofexport-orientedagricultureasa ‘preludetoindustrialization’ (ibid.:1–6).Anditreplacedthe LagosPlan’svisionofeconomicself-reliance anddomesticfinancewithacallforadoublingoftheworld’saidtoAfrica – aidoverwhelminglyconstitutedbydirectloansfromEuro-Americandevelopmentbanks.

Bundledtogetherwithanowfamiliarsetofpoliciesfocusedontradeliberalization andfiscalausterity,theseloansremainedfordecadesthedominantdevicewithwhich Africangovernmentsaccessedcapitaland,insomecases,thisfocusonpublicdebt largelyreplacedexistingdevelopmentprogrammesfocusedonlendingtoprivate enterprises(Ducastel 2019).Criticspointedtotheongoingfailureofstructuraladjustmentpoliciestoaddressthestagnationthatbothreportsidentifiedasasourceof profoundconcern – but,ofcourse,inradicallydifferentterms:oneasasteptowards ‘liberation’ andtheothertoaddressAfrica’ s ‘economiccrisis’ .

Bytheendofthetwentiethcentury,scholarsanddevelopmentexpertsconsolidatedafocusonthishistoricallyspecificframingofAfricaneconomicproblems. Criticsandadvocatesalikeunderstoodthisproblemintermsofthedynamicsofinternationalaid,extractiveexportsectorsandthequestionof ‘ access ’ inwhatcametobe knownas ‘theinformalsector’.Andtheyconceptualizedcapitalassomethingthatwas eitherinvestedfromoutsidethecontinentorextractedfromit.Amongmanyscholars,thereremainedanoverwhelmingviewthatsupposedlyglobalcapitalhadsimply bypassedriskyAfricaninvestmentsandejectedmuchofthecontinentfromitsglobal flows.Wheresuchcapitaldidre-routetowardsthecontinent,therewasashared sensethatitwastobefoundbeyondthecityofficesandbranchesofAfrica’sbanks andstockexchanges.InJamesFerguson’sinfluentialphrasing, ‘capitaldoesnot “flow” fromNewYorktoAngola’soilfields,orfromLondontoGhana’sgoldmines;ithops, neatlyskippingovermostofwhatliesbetween’ (2006:38).

Inthenewmillennium,therehasemergedarenewedframingofAfricaneconomic developmentthatisrevivingoldpan-Africanconcernswitheconomicindependence, sovereigntyandintra-continentalexchange.Andtodaythereisamovementof investors,officials,firmsandconsumersfashioningfinanceintoasignificantsector acrosstheAfricancontinent.Thegrowthofthissectorislinked,inpart,tothefinancialcrisisof2007–08andtheresultingsuppressionoffinancialreturnsacrossEuroAmerica(Aryeetey 2009).Thesubsequentsearchforreturnselsewhereencourageda newwaveofinvestmentinAfricanandother ‘emergingmarkets’.Itwasalsolinkedto thediscursiveshifttoward ‘AfricaRising’,inwhichthecontinent’smiddleclasswas framedasagrowingsourceofnewinvestmentopportunities.AsRoitman(2021)demonstrates,thisnotionwaspushedbytheEuro-Americanfinancialindustry’saspirationsforfrontiermarkets.ButitalsoemergedfromAfricanentrepreneursadvancing conceptssuchas ‘Africapitalism’,inwhichprivatesectorinitiativeisunderstoodtobe thepathtoeconomicprosperityandsocialwealth(Amaeshi etal. 2018).

Theexcitementsurrounding ‘AfricaRising’ and ‘Africapitalism’ hasbeenwidely criticizedforitsocclusionoftheongoingimportanceofcommodityprices,thelimits toindustrializationonthecontinent,thewaninggainsinGDP,andfortakinginspirationfromdeeplyunequalEuropeaninstitutions(Rodrik 2018;Sylla 2014;Ouma 2020a).Yetratherthandismissordenouncesuchaspirations,weunderstandthem asimportantelementsinahistoricallyspecificreframingoftheproblemof Africaneconomicdevelopment.Inthismoment,Africanfinancialinstitutionsare seizingonacriticalshiftinglobalfinance – itsmorals,itsaims,itstechniques,its geography – toreviveapan-Africanpoliticalvisionfirstarticulatedintheyearsprior to ‘debtdependency’ .

Inthepasttwodecades,thefinanciallandscapehaschangeddramatically.African nationstatesbegandrawingonanarrayofnewcreditfacilities.Theywelcomedan immenseexpansionofChinesefinancialinvestmentandlending,which,by2013,had surpassedthecombinedoutstandingloansofthefivelargestdevelopmentbanks (Dobbs etal. 2013).Chinaisnottheonlysignificantchange:between2006and2014, fourteenAfricanstatesissuedforeign-denominatedbondsforthefirsttime,amounting toUS$15billion(GevorkyanandKvangraven 2016:721).Withlowerreturnsavailablein Euro-Americanmarketsafter2008,internationalbanksarekeentoadvancesuchloans. Africanfinanceministries,fortheirpart,arehappytodrawondebtthatlackstheconditionsofdevelopmentbankborrowingandisoftencheaperandlongertermthan bondsintheirowncurrencies.Yet,by2019,theborrowingbingewasraisingredflags, andtheCovid-19slowdownsonlyexacerbatedthehighwireactofremainingfiscally dependentonhighlyvolatileprimaryresourceexports(Chelwa 2020).

Analysesofmicrofinancehaverevealedasimilarfinancialtrajectory.Once groundedinasocialmissiontoprovideaccesstocreditforindividualsexcludedfrom traditionalbanklending,microfinanceinstitutionsmovedtowardsamorelimited focusonfinancialreturnsforinvestors(Guérin 2015).ManyofthelargestmicrofinanceinstitutionsintheglobalSoutharepubliclylistingsharesonstockexchanges acrosstheworld,fromNewYorktoNairobi.Andinresponsetothistrend,microfinanceinstitutionsareinvestingintheimprovementoftheircreditscoringmethodologiestoensuremorepredictableandprofitablereturns(seeOpalo,thisissue).

TheWorldBankhasreactedtothisnewfinanciallandscapebyreconceptualizing itsownroleindevelopmentfinance.And,assomecommentatorshaveobserved,the shifttowardsthe ‘knowledgebank’– astoreofexpertise,ratherthanmoney – has alsomeantlettinggoofmuchofthecontroloverdevelopmentplanningitonce enjoyed.Thus,theBank’snewloanprogrammesclaimtoeasemanyofitsformerly stringentstandardsbyrelying ‘onclientstoidentifyexpectedresultsofaprogram’ ratherthanbankofficials(Runde 2015).Theseexpertshavealsoturnedtocapital marketsasawaytobridgethenew ‘financinggap’,anapproachthattheBankhelped popularizeinitsagenda-settingreport FromBillionstoTrillions (WorldBank 2015).In thisreframingofdevelopmentlending,WorldBankprojectspreparegovernmentsto improvetheircreditratings – theseratingsarethoughttoreducethecostoflending andtoopenupaccesstoanewpoolofcapitallocatedintheworld’sgrowingnumber ofstockexchanges.

CriticshavefocusedontheexpansionofAfricanEurobonds,sovereigndebtand theintegrationofmicrofinanceintoEuro-Americancapitalmarkets.Theyseeinthese trendsthepotentialforpowerfulinstitutionalinvestorssuchasBlackrocktobegin

negotiatingthetermsofloansandtheirloomingdefault(e.g.Gabor 2021).Indeed,the typesoffinanceemerginginAfricatodaycanbevolatile,extractiveandpredatory; capitalisunevenlyavailableandcouldusherinforeigninstitutionalinvestorsasnew andmorepredatorycreditorstoAfrica’seffortsateconomicdevelopment.Yetthere isnodoubtthat,fromLagostoNairobi,JohannesburgtoDakar,thereisalsoanewfoundsenseofopportunityaccompanyingthisbroaderfinancialshift – itisanorientationtowardsthefutureandanoutward-facingdispositionthatisnotnegatedby ongoingvolatility,precarityandinequality.Anumberofthearticlescollectedhere documentthisfuture-orientedexcitementasasocialfact,productiveofnewsocial relations,personalethicsandcommercialdealings(cf.GoldstoneandObarrio 2016).Muchofthisenergyandactivityisfuelledbyyoungerurbanprofessionals, ofteneducatedabroadandworkinginindustriesrangingfrominformationtechnologytoaccountingandfinance.

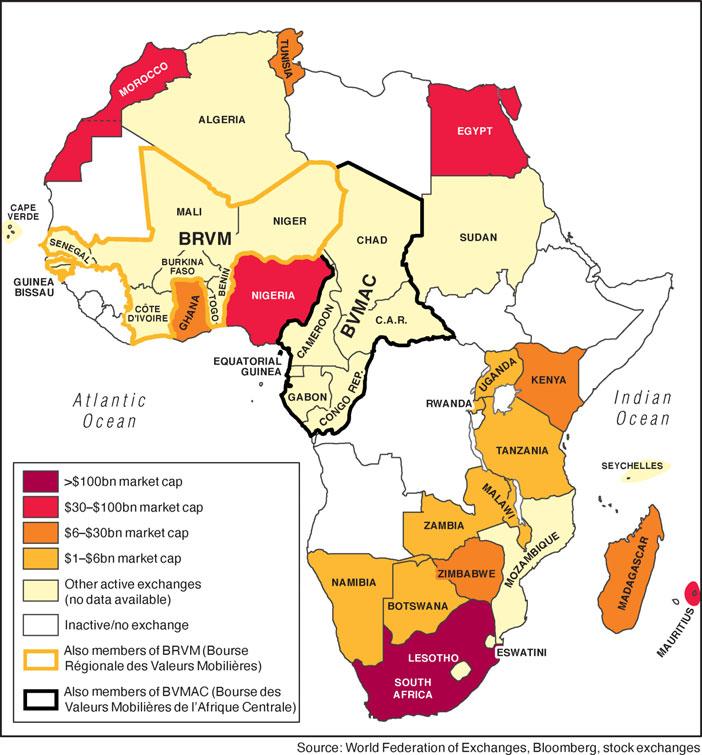

Fortheseactors, African capital, African creditratingsand African stockexchanges areunderstoodtobeapoliticallyviablealternativetothemorefamiliarEurobonds –sovereigndebtsecuritiesissuedonAmericanorEuropeanstockexchanges – onwhich mostscholarsandglobalcommentatorshavefocusedtheircriticalattention.They accompanyasignificantinstitutionalshift:between1990and2009,thenumberof stockexchangesonthecontinentgrewfromfivetoeighteen(Andrianaivoand Yartey 2010).Inthefollowingyears,Africancorporationssteadilyincreasedtheir issuanceofequityonstockmarkets,fromatotalofapproximatelyUS$5.5billion inissuancesin2011toUS$12.7billionin2015 – anincreaseof44percent (PricewaterhouseCoopers 2016).Asaresult,byDecember2015Africanexchanges hadamarketcapitalizationofapproximatelyUS$1trillion,with23percentresiding inexchangesoutsideSouthAfrica(ibid.).Whileholdingscanbeconcentratedinthe portfoliosoflargeinstitutionalinvestors,tradersandpolicymakersacrossthecontinentalsoworktomakeshareholdingapopularactivity:frominvestmenttrainingto promotionalcampaigns,thestockmarketisofferedtocitizensasameansofachievingtheirowngoalsandcontributingtocollectivewealth(seeMizes,thisissue).

Formanygovernments,privatizationwasameanswithwhichtoestablishthefirst generationofAfricanstockmarkets.Inthe1970s,theCôted’Ivoiregovernmentissued certaintaxrebatesintheformofvoucherstopurchaseassetsonwhatwasthencalled theAbidjanStockExchange(Mizes,thisissue).Later,ZambiaandTanzaniaboth establishedaprivatizationtrustfundthatpurchasedandheldhalfoftheoriginalissuanceoffmarkettobesoldlateratasteepdiscounttolocalinvestors.Suchinitiatives servedmanypurposes,fromnationalprestigeto ‘politicalcover’ forpotentially unpopularprivatizations(KennyandMoss 1998).EastAfrica’slargestbourse,in Nairobi,hasexpandedtoaconsiderabledegreethroughthesaleofoncepublicentitiestoprivateshareholders.Forinstance,sharesofthetelecommunicationscompany Safaricom – onceadepartmentofgovernment – arenowthemostvaluablestockat theNairobiSecuritiesExchange.

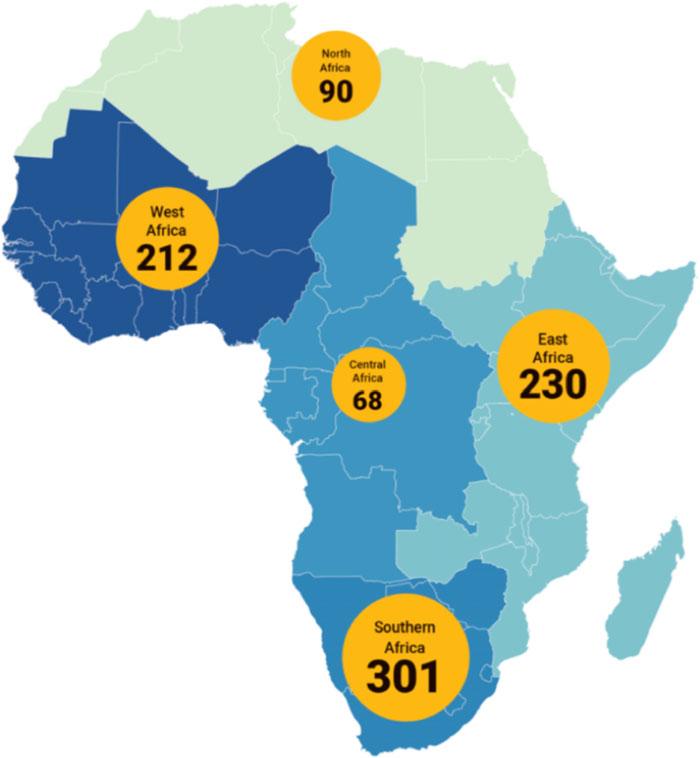

Stockmarketsarenotalone;thecontinent’sprivateequitymarketssimilarly appeartobeontherise.AsokoInsight,aNairobi-basedfirmspecializingindata andconsultancyservicesforAfrica’sprivatesector,recentlyassertedthatthecontinentisnowhometo ‘over400privateequity,venturecapitalandassetmanagement firms’ (Withagen 2021).Thegeographicspreadoftheirinvestmentsisunsurprising, withSouthAfrica,Nigeria,Kenya,MauritiusandEgyptfiguringastheleadinghubs.

Thefocusoftheirinvestmentsisalsounsurprising:financialserviceandinformation technologywerethetopinvestmentsectorsin2020(ibid.).ConsultantsatAsoko laudedtheUS$3.3billioninprivateequityinvestmentin2020,despiteitshalfbillion declinefromthepreviousyear – adeclinelargelyattributedtotheCovid-19pandemic.Whatisremarkableaboutsuchdescriptivestatisticsisnotonlythesizeof theinvestmenttheydescribe,buttheirexistence:consultingfirmsonthecontinent haveonlyinthepastdecadebegunpublishingthesenumbersashighlystylized graphicdisplaysinAfrica’sbusinesssectormedia.Suchfactscirculateaswindin thesailsofcapitalmarkets,enticingnewparticipantsandpotentiallycementing thelegitimacyofthisburgeoningindustry.

Closertotheconcernsofmanycitizens,thecontinentisalsohometoahostof consumerfinancialnovelties.Kenya’sM-Pesaquicklyexpandedtoanational

Figure2. Mapofprivateequity,venturecapitalandassetmanagementfirmsinAfricabyregion.

Source:AsokoInsight(Withagen 2021).

phenomenonafterits2007launchandisnowamodelforusingmobilephonestosend andreceivemoney(Park 2020).WhileM-Pesaconsolidatedadomesticremittance market,subsequentinvestmentsinotherenterprisesarenowdirectedatcreating theinfrastructureforinternationalmoneytransferandnewapproachestoregulating it(seeNing,thisissue).Diasporaremittanceshavegrownenormouslyandhave becomeasignificantenoughsourceofcapitaltocapturetheattentionofgovernments.WhileEthiopia’sfirstissuanceof ‘diasporabonds’ in2007fellshortofexpectations,Nigeria’ssuccessfulissuancein2017raisedUS$300millionforthe government’sinfrastructuralambitionsandwasoversubscribedby130percent (Benson 2019).

Therehasalsobeenanincreaseinintra-Africantrade.Whilemostpaymentson thecontinentremaindenominatedinUSdollars,thesepaymentshavedecreased

fromarateof51.1percentin2013to45.1percentin2017 – asix-pointdeclinecelebratedbytheAfricanDevelopmentBank(SWIFT 2018:3).Initsplace,currenciessuchas WestAfrica’sfrancCFAandtheSouthAfricanrandwereonasteadyincline.Industry analystsalsoforegroundtherelatedtrendoftheincreasingimportance ofintra-Africantradesuchthat ‘almost20%ofallcross-bordercommercialpayments sentbyAfricanBanksnowremainwithinthecontinent,upfrom16.7%in2017’ (ibid.: 4).Suchanincreaseis,ofcourse,aresultofAfricansfocusingtheirmonetaryexchanges onfamilial,commercialandconsumerpaymentswithinthecontinent.Butthese paymentsalsofigureasacentralelementinabroadervisionofpan-Africanintracontinentalexchange.

In2020,theAfricanUnionanticipatedtheinauguralimplementationoftheAfrican ContinentalFreeTradeAgreement(ACFTA),whichwilleliminate90percentofthe existingtariffsoninter-continentalexchangeofgoodsand,eventually,services (MooreandKenewendo 2020).Aspartofthisagreement,ahostofAfricaninstitutions arethussupportingthedevelopmentofthePan-AfricanPaymentandSettlement Platform,whichisanticipatedtofacilitatethecross-borderexchangesalreadyontherise acrossmuchofthecontinent.Crucialtothesetransformationsarethepan-Africanbanks, whicharealreadyleadingthemarketinfacilitatingsuchpaymentsandpositioningthemselvesasthelargeststoresofAfrica’smonetarywealth.Ecobank,forexample,claimsto haveexpandeditsinvestmentbankingoperationsby50percentperannumforthelast fiveyears.Indeed,wheresovereignbondsandprivatizationshavepreviouslydominated theassetsavailableforpurchaseonAfricanstockexchanges,Africa’sbanksaretoday takingstepstowardsexpandingthelistingofprivatefirmsandincreasingtheintegration ofcommercialbanksavingsandcapitalmarkets.

Andyet,atthesametimein2020,newinvestmentinAfrica’sequitycapitalmarketswasatadecadelow.Farfromtheheadydaysof2015anditsnearlyUS$13billion innewcorporateinvestment,theCovid-19pandemichadreducedthecontinent’ s issuancestoaroundUS$5billion(PricewaterhouseCoopers 2021).Butevenwith theslumpinnewequityissuances,anewroleforcapitalmarketsemerged:asanovel financialinfrastructurethroughwhichgovernmentscouldissue ‘pandemicrecovery bonds’ inlieuof – orinadditionto – assistancefromforeigngovernmentsandEuroAmericandevelopmentbanks.InMay2021,forexample,theMaliangovernment issueditsthirdrecoverybond(obligationderelance)ontheWestAfricanStock ExchangeinresponsetotheCovid-19pandemic.AndtheAfricanDevelopment Bankhassimilarlyturnedtocapitalmarkets – albeitoutsideAfricaontheLondon StockExchange – tofunditsownpandemicrecoverybonds(Yount-André 2021). Thesestepsremaintentativeandpreliminary,buttheyareneverthelessexemplaryofareformattedunderstandingoftheroleoffinanceinAfrica’spoliticsof development.Interpretivescholarshavemostlyavoidedthesetopics,cedingthe studyofcapitalmarketstoeconomicsanddevelopmentstudies.Yetsuchadisciplinarydivisionfurthersaviewoffinanceasabstractanddisembeddedfromsocialrelations,ethicalpracticesandeverydayactivity.Andwhileaflurryofwhitepapersand policyreportshavebeguntoanalysethequantitativeincreaseofsuchfinancialtransactions,thereissignificantlylesspublicandscholarlyattentiontohowmanyofthe actorsadvancingthisshiftinAfricancapitalaredrawingonthehistoriesofsolidarity, stateformationandpopularmoralitythatfirstemergedintheearlyyearsfollowing independence.Inotherwords,thereisanimmensesocialuniverseofordinarylabour, 550JamesChristopherMizesandKevinP.Donovan

newtechnologiesandcollectiveaspirationgoingintocomposingAfricancapitaltoday.

Hautefinanceparlebas

Butwhatdoesitmeanto ‘ compose ’ capital(cf.Guyer 2016)?Andwheredoessucha compositiontakeplace?Thearticlescollectedinthisissueof Africa buildonthenotion of ‘capitalization’,aconceptthatdrawsattentiontothearrayofdevices,institutions, proceduresandpoliticsthroughwhichcapitalismobilized.Ifcapitalis ‘valueinmotion’ (Harvey 2020),thenatstakeincapitalizationishowthatmotionisinaugurated,propelledandsustained.Thereis,inotherwords,considerablelabour – living,immaterial, affective,technicalandlegal – requiredforcapitalization,andthegoalofthispartissue istodepictsomeofthemanifoldwaysinwhichAfricansarepursuingit.

‘Capitalization’ hasatechnicalmeaningforfinancialaccountants:expectedfuture profitsadjustedforrisksanddiscountedintheirpresentvalue.Thediscountingof capitalduetoitsexpectedfuturevaluecanbetracedbacktofourteenth-century Italianmerchantswho ‘allowedcustomerstopre-paytheirbillsata “discount”’ (NitzanandBichler 2009:155).Theydidthisbecauseitgavethemcertaintyofpaymentinthepresentratherthanriskingtheirclientsdefaultingontheirdebtsinthe future.Discountingmeantthemerchantsreceivedlessmoneythantheywouldotherwise,butitprovidedcertainty.Andthisnotionofdiscountingremainsanimportant elementoffinancialexchangetoday: ‘discountedcashflow’ isoneofthemostwidely usedmethodsoffinancialvaluationacrosstheworld.

Putanotherway,anyenterpriseplanningforthefuturefacesuncertaintyabout whatmightbefallitsrevenuestreams – thismeansthatthereisatrade-offbetween whatitcanearntodayandwhatitmightearntomorrow. ‘Capitalization’ isawayto calculatethepresentvalueoftheserevenuestreamsgiventheirpotentialfuturevalue. Inthissense,capitalizationisanaccountingpracticethatguidestheallocationofwealth: itallowsaccountantstocalculatethecostsandreturnsofanassetoverthe extended courseofitsuse,andtoestimatethefuturevalueofthatasset.Today,capitalizationisan enormouslyinfluentialpracticeguidingnotonlybankersbutalsonon-financialcorporationsandstates:calculatingcapitalizationallowsinvestorstoevaluate firmsasassets andpotentiallyleveragethisequityintonewroundsofcapitalinvestment. Assuch,capitalizationisoneofthemostsignificantcategoriesoffinancialreasonthat hasemerged alongside – andmadepossible – thegrowthofthefinancialindustrytoday.

IntheUSA,anewwaveofcriticalreflectiononcapitalmarketsswelledaroundthe 2007–08crisis,andregulatoryauthoritiesandacademicsaliketookupthefamiliar taskofmakingsenseofaneconomyin ‘crisis’ (Roitman 2013).Initsscholarlyform, capitalizationthusemergedas ‘theconstantsearchingout,ortheconstructionof, newassetstreams’ (LeyshonandThrift 2007:98).Here,financeisnotunderstood toworkthroughungroundedspeculation,butisinsteadfoundedon ‘somekindof collateral ::: thatusuallyturnsouttobeintheformoffixedassetsthatwillyield apredictableincomestream’ (ibid.:99).Insuchcases,determining ‘earningpower’–theexpectedrateofreturnonaninvestment – isfundamental,andcapitalizationis theconceptualcategorythatrendersthisfuturecapacitycalculable(Muniesa etal. 2017:31).Itiswiththeknowledgeofthisincomestreamthatfinancierscanleverage

552JamesChristopherMizesandKevinP.Donovan

theirposition,borrowingandengineeringthespeculativeexercisesthatcapture headlinesandhavetodayamassedagrowingcrowdofglobalcritics.

Butassetsdonotsimplyexist.Rather,theyarecomposedthroughhighlyspecific constellationsoflabour,law,infrastructure,accountingandrhetoric(Birchand Muniesa 2020).Capital,inotherwords,isanachievement.So,ouranalyticaltask istounderstandhowculturalvalues,socialrelationsandtheexerciseofdiverse andoftencompetingformsofpowerarrangethemselvessothatcapitalization becomesapossible,knowableandcontroversialthingintheworld.Africanistanthropology,ofcourse,haslongexcelledatthissortofanalysisofvalueandwealth: whethertheimportanceofaestheticandaffectivejudgementsofNuercattle (Evans-Pritchard 1940),thecommunalboundingofspheresofexchange(Bohannan 1955),thenegotiationofcross-culturalformsofsocialvalue(Pietz 1985),orthedistributionofresourcesbasedonsocialrank(Guyer 2004),theiconicstudiesinthis traditionareconcernedwiththemannerinwhichputatively ‘cultural’ commitments shapewealth,exchangeandproduction.

Morerecentworkinthistraditionattendstotheproliferationofconsumerfinance acrossthecontinent.Anthropologistsemphasizehowsupposedabstractionssuchas ‘capital’ or ‘credit’ areembeddedwithinpopularethicsandtransformedthroughconsumerbehaviour.SibelKusimba(2021),forinstance,locatesthesuccessofKenya’ s breakthroughmobilemoneyservice,M-Pesa,withinthecountry’sextendedkinship networks.Growingindebtednesshasbeenaparticularfocusofstudy,withanthropologistsdemonstratingnotonlyhowpredatorylendingfuelsdispossessionandsubordination,butalsohowfinanceisitselfdependentuponpopularpracticesandvalues (Elyachar 2005).Whetheritisaspirationsforeducationandconsumptionamong SouthAfrica’spost-apartheidmiddleclass(James 2014),ordesirestosecureagood death(Bähre 2020),noveltechniquesofindebtednessdonotstandapartfromlongstandinghistoriesandcultures.

Yetthisscholarshipcontinuestoworkonanunspokendivisionoflabour:economistsanalyse ‘highfinance’ whileanthropologistsattendtoeconomiclife ‘from below’ (HullandJames 2012:1).Theemergenceoftheideaofthe ‘informalsector’–and,later,the ‘populareconomy’– isacaseinpoint:economicanthropologists advancedthis ‘sector’ astheappropriatedomainofethnographicinquiry(Hart 1973).ThishaslongbeenheldupasanempiricalcontrasttothemistakenassumptionsofexpatriatedevelopmenteconomistsabouteconomiclifeinAfrica(Ferguson 1994).Anthropologistshavearguedthattheuniversalizingtendencyofeconomists hasoverlookedruralinequality,theextendednatureofAfricanhouseholds,and theroleofwomeninproduction(Hill 1986).Theresulthasbeenadisciplinarydivide: ethnographywasthoughttobetheappropriatemethodwithwhichtowitnessand experience ‘thirdworld’ bazaars;andeconometricsemergedasamethodthateconomistsemployedtoanalyseaseeminglydifferentuniverseofeconomicphenomena.1

1 Morerecently,someeconomistshaverecognizedtheneedforeconometricapproachesthatincorporateanthropologicalinsights.Forinstance,giventhatthe ‘household’ istheunitatthecoreofmany economicmodels,theculturallydistinctwaysinwhichfamiliesareorganizedhavereceivedsomeattentionbyquantitativeandformalistscholars.CelestinMonga(2017)goesfurther,callingfor ‘postmacroeconomics’,anapproachfocusedonthelimitsofmathematics,thepluralityofhumanmotivations andinterests,andtheutilityofvarioustypesofdata.

Amonganthropologists,thecommitmenttothisdichotomycontinuestoshape understandingsofthe ‘ opaque ’ economictransformationsofcapital’ s ‘violenceof abstraction’ (ComaroffandComaroff 1999).Here,thefinancialindustryappearsless asanobjectofstudythanasaspectrehoveringinthebackgroundandproducing superstructuralformations – xenophobia,witchcraftor419scams – onlytheeffects ofwhichareavailableforethnographicanalysis.

TheavoidanceofhighfinancebyAfricananthropologyreflectsasensenotonly thatitisirrelevanttomostAfricans’ livesbutthattheindustryisarealmofabstract uniformity,unavailabletosocio-culturalanalysis.Yetinrecentyears,anthropologists workingelsewhereintheworldhavesuccessfullychallengedsuchdivisionsand openeduptheeliteuniverseoffinancetoanthropologicalinquiry.Theyhaveoffered anewperspectiveonthe(im)moralaspirationsofstockexchangetradersthemselves (Ho 2009)andthetechnicalandperformativeworkoffinancialanalystsandcorporate lawyers(Riles 2011).Indoingso,theyhaveshownthatsupposedly ‘global’ financeis theresultofemplacedactivitiesandequipment:aderivativesmarketforcorn,for example,existsthroughtheembodiedactivitiesoftradersinanoffice,communicatingthroughparticularinfrastructuresandsocializedhabits(see,forexample, MacKenzie 2008:8–37).AndasDaromirRudnyckyj(2018)argues,theseextantfinancialconfigurationsarecontinuallyincompetitionwithemergingfinancialcentresin theglobalSouth.Inshort,thesescholarshavereframedhighfinanceasalegitimate objectofanthropologicalinquiryataglobalscale.YetAfricahasmadelittleappearanceintheseanalyses.

NewerapproachesdooffersomeinsightsforAfricancapitalanditsinstruments (BreckenridgeandJames 2021).StefanOuma(2016:84),forinstance,adoptsan approachtothe ‘operationsofcapital’ thatdescribesthe ‘socio-legalandtechnical architecture’ throughwhichAfricanagricultureisconverted ‘intoanalternativeasset class’.Suchanapproachfocusesontheworkittakestocreateandsustaincapital,as wellasitsfrictionsandtensions.Otherapproachesfocusmoreontheprofessional legitimacyofexpertsdoingthiswork,whetherAfricaneconomistsorbureaucrats. AccordingtoBéatriceHibouandBorisSamuel(2011:12),macro-economictechniques emergedinAfricaalongsidetheexpansionofitsdevelopmentalstates,leadingupto andintheyearsfollowingnationalindependence.Yetbeyonddocumentingthesimpleappearanceofsuchtechniques,theirapproachto ‘macroéconomieparlebas’ (macroeconomyfrombelow)drawsattentiontotheuniverseofsocialrelations andstrugglesamongeconomicexpertsthatexists ‘behindthefrozen,etherealimage of[macro-economic]statistics’ (ibid.:13).Whilemanyofthesetechniquesremainthe jurisdictionofgovernmentalexpertsandtheirstrategiesforadvancingnational economicdevelopment(Samuel 2011),therealsoexistsauniverseof ‘politicsbeyond thestate’ (ibid.:9)inwhichcreditratings(Vallée 2011)andunregulatedcredit markets(Guyer etal. 2011)arethemselvesconsequentialformsofmacro-economic government ‘parlebas’ .

Thearticlescollectedinthispartissueof Africa complementthisapproachbycentringourcollectiveanalysisonwhatcanbehelpfullytermed ‘hautefinanceparlebas’ (highfinancefrombelow).Withthisapproach,weaimtofurtherelucidatethediverse devicesoffinancialgovernancethatareconstitutingthenetworkoffinancialinfrastructuresappearingacrossAfricatoday.Thecontributionstothiscollectiontakethe perspectiveoftheinvestors,analysts,entrepreneurs,regulators,bankersand

technocratstaskedwithrealizingthisnewapproachtoeconomicdevelopment,an approachoftenexplicitlylinkedtoAfricancapitalizationandliberation.Here,particularculturalunderstandingsoffinancearefarmorethanatooltolegitimize,accommodateanddomesticateEuro-Americancapitalflows.Asthearticlescollectedhere emphasize,long-standingvisionsofAfricaneconomicdevelopmentshapethecreationofassetsandtheircompositionintoAfricancapitaltoday.

TheAfricanCapitalMarketsConferencewithwhichweopenedthisarticleisexemplaryofthesortsoffinancialtransformationsappearingonthegroundacrossthe continenttoday – andinthepagesofthisissue.In2016,wearrivedinCapeTown totakestockofhowonecornerofAfrica’sfinancialuniversewasmakingsenseof thesetransformations,andhowcapitalmarketactorsthemselvessoughttoadvance orrestrainthem.Althoughtheconferencewasheldinoneofthecontinent’smost raciallyexclusiveenclaves,itneverthelessexemplifiedan aspiration forpanAfricancapitalization.Manyofitspanelswerebilledasanexplorationofcapital growth ‘throughoutAfrica’ oroftheimpactofglobalchanges ‘acrossthecontinent’ . Eveniffewofthesecouldtrulyreckonwithsuchanambitiousremit – whetheronthe daisorinmoreinformalconversationsatlunch,oncigarettebreaksorinthetrade showhall – thevisionofacontinent-widemarketservedasbothaconcretegoalanda legitimatingdevice.

Despitetheseaspirations,theconferenceisareminderofthecontinent’ s unevenfinancialgeography:SouthAfricahaslongseemedinaclassofitsown, andevensignificanthubssuchasNairobiorLagoscanseemaworldapartfrom theeconomicrealitiesafewhoursaway.Whereconversationattheconference explicitlyexpandedbeyondnationalborders,thedifficultiesofdoingsowereevident. Consider,forexample,theloneroundtablefocusedexplicitlyontheproblemof integratingAfrica’sdiversecapitalmarkets.GatheringtogetherstockexchangeexecutivesfromSenegal,Namibia,KenyaandSouthAfrica,theroundtableaimedat ‘improvinginter-marketcollaborationandtransparency’ acrossthecontinent.And thehostbeganbyposingseveralintroductoryquestions: ‘Whatisnecessarytofoster greater standardizationamongemergingAfricancapitalmarkets?Whatrolecan thevariouslocalexchangesandpan-Africanassociationsplay?’

Toelaboratethisvisionofpan-Africanintegration,theseexecutivesturnedtoa discussionofsomeofthemoremundanetechnicalaspectsofsecuritiesmarkets. Theyposedthequestion:whatisthe ‘requisitefinancialinfrastructure’ neededto drivethisintegration?Foryears,thesestockmarketshadsoughttoincreasethe cross-listingandinter-marketexchangeoffinancialassetsinordertoexpandtheir liquidityand,inturn,theamountofcapitalflowingthroughtheirexchanges.While theyhadalreadyintegratedtheirdigitalplatforms,tradingacrossbordersremained limited.AccordingtotheCEOoftheNamibianStockExchange,thetroublewasalack of ‘socialinfrastructure’:brokerssimplydidnotknowortrustoneanother.Industry conferenceswereonewaytobuildmoreconfidenceandstrongerrelationships betweenbrokersandexecutivesacrosscontinentalborders.

Atstakefortheseexecutiveswas,inpart,capitalization.Beyondaplatformfor tradingassets,stockmarketsarethemselvescompaniesseekingtoincreasetheir

ownreturnsandexpandtheirmarketcapitalization.Butwhatisnotimmediatelyevidentishowintra-Africanintegrationcametobeanimportantframewithinwhichto advancesuchcapitalization.Iftheproblemweresimplyoneofliquidityandcapital flow,forexample,thenattractingforeigninvestorsfromoutsidethecontinentmight beamoresuitableapproach.Yetalongsideanarrayofpan-Africanofficials,these executivesareturningtowardsotherlocationsacrossthecontinenttocompose andcirculatethefinancialassetsthattheirstockmarketsneedtogrowandsurvive inagloballycompetitiveindustry.

Thisspecialissuereflectsthissenseofgeographicindeterminacy.Seenfromthe perspectiveofGDPfiguresorstockvaluations,nationaleconomiessuchasSouth Africa,NigeriaandKenyamaycapturetheattentionofjournalistsandscholars. ButJohannesburg,LagosandNairobifadeinpredominancewhenseenfromtheperspectiveoffinanciersseekinganewfrontier,orfromtheperspectiveofaccountants inLomé(Opalo,thisissue)andbankersinBrazzavilletryingtosecuretheirownprofessionalfutures(Ning,thisissue).Inotherwords,ratherthanhewingtoobviouscartographiesofAfricancapital,thecontributionstothisissueanalysetoday’ s unexpectedeffervescenceofcapitalizationacrossAfricafromlocationsinwhichsuch techniquesarenotyet – butmayonedaybe – amoralandfinancialnorm.

Consider,forexample,thecaseofprivatizationinEthiopia(Collins,thisissue). Ethiopianofficialshaveresistedthecontinentaltrendtowardspubliclisting:there isnonationalstockmarketandprivatizationremainsselective.Yetthepastdecades haveseenanegotiated – ratherthanforeclosed – processofrenderingpublicentities intoprivateones.TheEthiopianstate’slegitimacydependsonsuccessfuldevelopmentaloutcomes,butitisalsocognizantoftherisksofsurrenderingtoprivateactors theabilitytocommandresources.Selectiveprivatization,therefore,providesameans ofgeneratingrevenuethatcanberepurposedforotherdomains,suchasinfrastructure orindustryorfortheanticipatedconstructionofEthiopia’sownnationalstockmarket. Doingsoisnotmerelyadrytechnicalmatterofaccounting.AsChristinaTekeCollins analyses,PrimeMinisterAbiyfashionsitasaprojectof medemer,anAmharicwordfor ‘comingtogether’ or ‘ synergy ’ thattodaygesturesalsotoeconomicopenness.

PrivatizationinCôted’Ivoireisalsoinvestedwithsimilarmoralsignificance – itis linkedtoapost-independencevisionofeconomicself-sufficiencyandgrowth.Inline withthisvision,nationalleadersinthe1970screatedastockexchangeastheirpreferredvehiclefortheprivatizationofpublicassets.Today,anorganizationofsmall shareholders(petitsporteurs)ontheRegionalStockExchangeofWestAfrica(LaBourse RégionaledesValeursMobilièresdel’Afriquedel’OuestorBRVM)isadvocatingfora returntothemoralvaluesthatguidedsuchreforms:theyadvancewiderstockmarket participationnotsomuchasastrategyofeconomicdevelopment,butasoneofmoral reformationoftheeconomy(Mizes,thisissue).FrustratedbythecaptureofcommercialreturnsbyAfricanandEuropeanelites,the petitsporteurs envisionamorewidely distributedequitymarketasameansofdiscipliningunaccountableelitesthrough transparency.The petitsporteurs seecommercialandmoralvalueincapitalmarkets, andtheytakestepstoreformulatefinancialinstrumentstomaximizethem.

TherefashioningofsuchdevicesisalsoatstakeinTogo,wherethelendingindustryishometodivergentideasandpracticesofestablishingcreditworthinessand managingrisk(Opalo,thisissue).FunderssuchastheWorldBankhavesupported theexpansionofcreditbureausthatgatherandstandardizefinancialhistoriesin

556JamesChristopherMizesandKevinP.Donovan

ordertodetermineassessmentsofcreditworthiness.Theresultingcreditscoresare promissorytechniques,offeringameanstoknowthefuturelikelihoodofrepayment byindividuals.Theyarealsomeanttoendinformationasymmetriesthataresaidto keepcreditexpensiveandexclusive.Incontrasttotheseideasofriskmanagement, theloanofficersattheLomésavingsandcreditcooperativewhereVanessaWatters Opaloworkedthinkthatrepaymentisonlypossiblethroughwhattheycallthe ‘real work’ ofinterviewingclientsandvisitingtheirhomes.These ‘relationalformsof assurance ’ worknotthroughthetranslationofpastbehavioursintofuturepredictionsbutratherinthehereandnow,adaptingtovolatilecircumstances.

Riskscomeinmanyforms.InGhana,Anna-RiikkaKauppinen(thisissue)explores howatangleofriskswasinterpretedthroughalonghistoryofeconomicnationalism andnewerinstrumentsoffinancialengineering.BetweenAugust2017andJanuary 2019,theGhanaianstatetookovernine ‘indigenousbanks’.Workinginoneofthese banks,Kauppinentracksthevaluesattachedtoindigeneity,showinghowpoliticians, bankersandcitizensaspiredtoeconomicsovereignty – anotionassociatedwith KwameNkrumahbutthatassumednewsignificanceinaneraofeconomicliberalization.Itwasnotthequantitativeaccumulationofcapitalthatwasatstakesomuchas thequalitativeharnessingofcapitalasGhanaian,whilebankers,regulatorsandcitizensdebatedtheethicsoffinancialreform.Itisthroughthiscombinationoffinancial instruments,encountersanddiscontentthatthemoralcategoryof ‘indigenousbank’ cametoaffectfinancialflowsinGhana.

Ofcourse,fewinGhanawantedanythinglikeautarky.Inadvocatingeconomicsovereignty,theywereadvocatingforaversionofcontrolovertheallocationofcapital ontimelinesandatpricesthatwouldservethenation.Thenation,though,ishardly coterminouswiththeterritory – whetheritbethroughcross-bordercommercialnetworks,regionalmonetaryunionsordiasporaremittances.RundongNing(thisissue) turnsourattentiontothesedynamicsinastudyoftraders,foreignexchangeand centralbankregulationinCongo(Brazzaville).Howdoesastateregulatemonetary flowswithintheconfinesofthefrancCFAregime?Ningarguesthatitcomesdownto formalities – namely,thepaperformsthatmustaccompanyrequestsforforeigncurrencies.Paperwork,heargues,isnotsomuchabouttheconveyanceofinformationas itisaboutslowingdowndemandforforeigncurrency.Requiringnewformalities allowsthecentralbanktoindirectlyaffectthecostofforeignexchangeandthespeed withwhichitcirculates.Adjustingthesechannelswasacentralmeansofgoverning moneyintheaftermathofadropinoilprices.However,thecentralbankcannotact unilaterally:instead,itmustcreativelyrepurposepaperworkrequiredofChineseand Levantinemerchantswho,inturn,themselvescreatetheirownwaystoadjustthese bureaucratic ‘valves’.Theresultisasetoffinancialflowsshapedbymultipleinterests, technologiesandnorms.

Takentogether,thearticlesinthisissuerevealtheemergingdynamicsofAfrican capitalization.Thereare,inshort,immenseanddiversefieldsofpoliticalandcultural engagementsurroundingAfricancapitalizationtoday.Theyarelocatedinthecontested constructionofthevariousdevicesandpracticesthatmay – ormaynot – cometo constituteanintegrated,independentnetworkoffinancialinfrastructuresfitfor Africanaspirations.

Acknowledgements.WearegratefulforthesupportofWaleAdebanwi,whooriginallyinvitedusto submitthiscollection.ManythanksgoaswelltoJanetRoitmanandHannahAppelfortheirgenerous engagementwithearlyversionsofthearticlescollectedhere.Ouranonymousreviewersofferedcrucial guidancethroughtheeditorialprocess,forwhichwearethankful.ThanksalsotoBorisSamuelforhis support,inspirationandthoughtfulsuggestionsaswecomposedthisintroduction.Andfinally,weare especiallygratefultothecontributorstothisissueforofferingusthechancetothinkthroughourmaterialtogether.

References

Amaeshi,K.,A.OkupeandU.Idemudia(2018) Africapitalism:rethinkingtheroleofbusinessinAfrica Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress. Andrianaivo,M.andC.A.Yartey(2010) ‘UnderstandingthegrowthofAfricanfinancialmarkets’ , African DevelopmentReview 22(3):394–418.

Arrighi,G.(2002) ‘TheAfricancrisis’ , NewLeftReview 15:5–36.

Aryeetey,E.(2009) ‘TheglobalfinancialcrisisanddomesticresourcemobilizationinAfrica’.African DevelopmentBankGroupWorkingPaper101.Tunis:AfricanDevelopmentBank.

Austen,R.A.(1987) AfricanEconomicHistory:internaldevelopmentandexternaldependency.London:James Currey.

Austin,G.(1993) ‘IndigenouscreditinstitutionsinWestAfrica, c.1750–c.1960’ inG.AustinandK.Sugihara (eds), LocalSuppliersofCreditintheThirdWorld,1750–1960.London:PalgraveMacmillan.

Austin,G.(2005) Labour,LandandCapitalinGhana:fromslaverytofreelabourinAsante,1807–1956.Rochester NY:UniversityofRochesterPress.

Bähre,E.(2020) IroniesofSolidarity:insuranceandfinancializationofkinshipinSouthAfrica.London:Zed Books.

Bamba,A.B.(2020) ‘DisplacingtheFrench?Ivoriandevelopmentandthequestionofeconomicdecolonization,1946–1975’ inV.DimierandS.Stockwell(eds), TheBusinessofDevelopmentinPostcolonialAfrica. Cambridge:PalgraveMacmillan.

Benson,J.(2019) ‘HowbondsaimedattheAfricandiasporacanraisecrucialfundsforAfrica’ , African Arguments,10July <https://africanarguments.org/2019/07/10/how-bonds-aimed-at-the-diasporacan-raise-crucial-funds-for-africa/>. Birch,K.andF.Muniesa(2020) Assetization:turningthingsintoassetsintechnoscientificcapitalism.Cambridge MA:MITPress.

Bishara,F.A.(2017) ASeaofDebt:lawandeconomiclifeinthewesternIndianOcean,1780–1950.Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress. Bohannan,P.(1955) ‘SomeprinciplesofexchangeandinvestmentamongtheTiv’ , AmericanAnthropologist 57(1):60–70.

Breckenridge,K.andD.James(2021) ‘Recentringthemargins:theorizingAfricancapitalismafter50 years ’ , EconomyandSociety 50(1):1–8. Chelwa,G.(2020) ‘ChinablamedforZambia’sdebt,buttheWest’sbanksandagenciesenabledit’ , Mail&Guardian,18November <https://mg.co.za/africa/2020-11-18-china-blamed-for-zambias-debtbut-the-wests-banks-and-agencies-enabled-it/>. Comaroff,J.andJ.L.Comaroff(1999) ‘Occulteconomiesandtheviolenceofabstraction:notesfromthe SouthAfricanpostcolony’ , AmericanEthnologist 26(2):279–303. Cowen,M.P.andR.W.Shenton(1991) ‘Bankers,peasants,andlandinBritishWestAfrica1905–37’ , Journal ofPeasantStudies 19(1):26–58. Diouf,M.(2000) ‘TheSenegaleseMuridtradediasporaandthemakingofavernacularcosmopolitanism’ , PublicCulture 12(3):679–702.

Dobbs,R.,N.LeungandS.Lund(2013) ‘China’srisingstatureinglobalfinance’ , McKinseyQuarterly,July. Donovan,K.(2018) ‘Sovereignscales:frontiersofvalueinEastAfrica’.PhDdissertation,Universityof Michigan.

Ducastel,A.(2019) ‘Unebanquecommelesautres?’ , ActesdelaRechercheenSciencesSociales 229(4):34–45. Elyachar,J.(2005) MarketsofDispossession:NGOs,economicdevelopment,andthestateinCairo.DurhamNC: DukeUniversityPress.

558JamesChristopherMizesandKevinP.Donovan

Evans-Pritchard,E.E.(1940) TheNuer:adescriptionofthemodesoflivelihoodandpoliticalinstitutionsofa Niloticpeople.Oxford:ClarendonPress.

Ferguson,J.(1994) TheAnti-PoliticsMachine: ‘development,’ depoliticization,andbureaucraticpowerinLesotho. MinneapolisMN:UniversityofMinnesotaPress.

Ferguson,J.(2006) GlobalShadows:Africaintheneoliberalworldorder.DurhamNC:DukeUniversityPress. Forrest,T.(1994) TheAdvanceofAfricanCapital:thegrowthofNigerianprivateenterprise.Edinburgh: EdinburghUniversityPress.

Gabor,D.(2021) ‘TheWallStreetconsensus’ , DevelopmentandChange 52(3):429–59.

Gadha,M.B.,F.Kaboub,K.Koddenbrock,I.MahmoudandN.S.Sylla(2021) EconomicandMonetary Sovereigntyin21stCenturyAfrica.London:PlutoPress.

Getachew,A.(2019) WorldmakingafterEmpire:theriseandfallofself-determination.PrincetonNJ:Princeton UniversityPress.

Gevorkyan,A.V.andI.H.Kvangraven(2016) ‘AssessingrecentdeterminantsofborrowingcostsinsubSaharanAfrica’ , ReviewofDevelopmentEconomics 20(4):721–38.

Ghai,D.(1973) EconomicIndependenceinAfrica.Nairobi:KenyaLiteratureBureau.

Goldstone,B.andJ.Obarrio(2016) AfricanFutures:essaysoncrisis,emergence,andpossibility.ChicagoILand London:UniversityofChicagoPress.

Green,T.(2020) AFistfulofShells:WestAfricafromtheriseoftheslavetradetotheageofrevolution.London: PenguinBooks.

Guérin,I.(2015) LaMicrofinanceetsesdérives:emanciper,disciplinerouexploiter? Paris:Demopolis.

Guyer,J.I.(2004) MarginalGains:monetarytransactionsinAtlanticAfrica.ChicagoIL:UniversityofChicago Press.

Guyer,J.I.(2016) Legacies,Logics,Logistics.ChicagoIL:UniversityofChicagoPress.

Guyer,J.I.andS.M.E.Belinga(1995) ‘Wealthinpeopleaswealthinknowledge:accumulationandcompositioninEquatorialAfrica’ , JournalofAfricanHistory 36(1):91–120.

Guyer,J.I.andK.Pallaver(2018) ‘MoneyandcurrencyinAfricanhistory’ in OxfordResearchEncyclopediaof AfricanHistory [online].

Guyer,J.I.,K.Salami,O.AkinladeandJ.-P.Warnier(2011) ‘“Kòs’´ow´o ”:iln’yapasd’argent!’ , Politique Africaine 124(4):43–65.

Hart,K.(1973) ‘InformalincomeopportunitiesandurbanemploymentinGhana’ , JournalofModernAfrican Studies 11(1):61–89. Harvey,D.(2020) ‘Valueinmotion’ , NewLeftReview 126:99–116. Hibou,B.andB.Samuel(2011) ‘MacroéconomieetpolitiqueenAfrique’ , PolitiqueAfricaine 124(4):5–27. Hill,P.(1986) DevelopmentEconomicsonTrial:theanthropologicalcaseforaprosecution.Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress.

Ho,K.(2009) Liquidated:ananthropologyofWallStreet.DurhamNC:DukeUniversityPress.

Hopkins,A.G.(1973) AnEconomicHistoryofWestAfrica.NewYorkNY:ColumbiaUniversityPress. Hull,E.andD.James(2012) ‘Introduction:populareconomiesinSouthAfrica’ , Africa 82(1):1–19. Iliffe,J.(1983) TheEmergenceofAfricanCapitalism.London:Macmillan. IMN(2016) ‘14thAnnualAfricanCapitalMarketsConference’,InformationManagementNetwork(IMN) <https://www.imn.org/structured-finance/conference/African-Capital-Markets-2016/Description. html>,accessed21October2020.

Jakes,A.(2020) Egypt’sOccupation:colonialeconomismandthecrisesofcapitalism.PaloAltoCA:Stanford UniversityPress.

James,D.(2014) ‘“Deeperintoahole?” BorrowingandlendinginSouthAfrica’ , CurrentAnthropology 55(S9):S17–S29.

Jerven,M.(2014) EconomicGrowthandMeasurementReconsideredinBotswana,Kenya,Tanzania,andZambia, 1965–1995.Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress. Kanogo,T.(1987) SquattersandtheRootsofMauMau:1905–63.AthensOH:OhioUniversityPress.

Kenny,C.J.andT.J.Moss(1998) ‘StockmarketsinAfrica:emerginglionsorwhiteelephants?’ , World Development 26(5):829–43. Kusimba,S.(2021) ReimaginingMoney:Kenyainthedigitalfinancerevolution.StanfordCA:Stanford UniversityPress.

Kvangraven,I.H.,K.KoddenbrockandN.S.Sylla(2021) ‘Financialsubordinationandunevenfinancializationin21stcenturyAfrica’ , CommunityDevelopmentJournal 56(1):119–40.

Leins,S.(2018) StoriesofCapitalism:insidetheroleoffinancialanalysts.ChicagoIL:UniversityofChicago Press.

Leyshon,A.andN.Thrift(2007) ‘Thecapitalizationofalmosteverything:thefutureoffinanceandcapitalism’ , Theory,CultureandSociety 24(7–8):97–115.

MacKenzie,D.(2008) MaterialMarkets:howeconomicagentsareconstructed.Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress. Mawdsley,E.(2018) ‘DevelopmentgeographyII:financialization’ , ProgressinHumanGeography 42(2): 264–74.

MbengMezui,C.(2017) Financerl’Afrique:densifierlessystèmesfinancierslocaux.Paris:ÉditionsSaintHonoré.

Meillassoux,C.(1981) Maidens,MealandMoney:capitalismandthedomesticcommunity.Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress.

Mizes,J.C.(2016) ‘WhoownsAfrica’sinfrastructure?’ , Limn 6(7):53–9. Monga,C.(2017) ‘Themacroeconomicsofmarginalgains:Africa’slessonstosocialtheorists’ in W.Adebanwi(ed.), ThePoliticalEconomyofEverydayLifeinAfrica:beyondthemargins.London:JamesCurrey. Montagne,S.andH.Ortiz(2013) ‘Sociologiedel’agencefinancière:enjeuxetperspectives’ , Sociétés Contemporaines 92(4):7–33.

Moore,G.andB.Kenewendo(2020) ‘Meettheworld’slargestfreetradearea’ , ForeignPolicy,13November <https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/11/13/afcfta-free-trade-africa-economics/>. Muniesa,F.,L.Doganova,H.Ortiz,Á.Pina-Stranger,F.Paterson,A.Bourgoin,V.Ehrenstein,P.-A.Juven, D.Pontille,B.Saraç-LesavreandY.Guillaum(2017) Capitalization:aculturalguide.Paris:PressesdesMines. Mwangi,W.(2001) ‘Ofcoinsandconquest:theEastAfricancurrencyboard,therupeecrisis,andthe problemofcolonialismintheEastAfricanprotectorate’ , ComparativeStudiesinSocietyandHistory 43(4):763–87.

Nitzan,J.andS.Bichler(2009) CapitalasPower:astudyoforderandcreorder.NewYorkNY:Routledge. Nkrumah.K.(1965) Neo-colonialism:thelaststageofimperialism.London:Panaf.

Ong,A.andS.J.Collier(2007) GlobalAssemblages:technology,politics,andethicsasanthropologicalproblems. MaldenMA:Blackwell.

OrganisationofAfricanUnity(OAU)(1980) LagosPlanofActionfortheEconomicDevelopmentofAfrica,1980–2000.Geneva:InternationalInstituteforLabourStudies. Ouma,S.(2016) ‘Fromfinancializationtooperationsofcapital:historicizinganddisentanglingthe finance–farmlandnexus’ , Geoforum 72:82–93.

Ouma,S.(2020a) ‘“Africapitalism” andthelimitsofanyvariantofcapitalism’ , ReviewofAfricanPoliticalEconomy, 16July <https://roape.net/2020/07/16/africapitalism-and-the-limits-of-any-variant-of-capitalism/>. Ouma,S.(2020b) FarmingasFinancialAsset:globalfinanceandthemakingofinstitutionallandscapes.Newcastle uponTyne:AgendaPublishing. Park,E.(2020) ‘“HumanATMs”:M-PesaandtheexpropriationofaffectiveworkinSafaricom’sKenya’ , Africa 90(5):914–33. Pietz,W.(1985) ‘Theproblemofthefetish:I’ , RES:AnthropologyandAesthetics 9(1):5–17. PricewaterhouseCoopers(2016) 2015AfricaCapitalMarketsWatch.Bloemfontein:PricewaterhouseCoopers Inc.SouthAfrica <https://www.pwc.co.za/en/assets/pdf/africa-capital-markets-watch-2015.pdf> PricewaterhouseCoopers(2021) 2020AfricaCapitalMarketsWatch.Bloemfontein:PricewaterhouseCoopers Inc.SouthAfrica <https://www.pwc.co.za/en/assets/pdf/africa-capital-markets-watch-2020.pdf> Riles,A.(2011) CollateralKnowledge:legalreasoningintheglobalfinancialmarkets.ChicagoIL:Universityof ChicagoPress. Rodrik,D.(2018) ‘AnAfricangrowthmiracle?’ , JournalofAfricanEconomies 27(1):10–27. Roitman,J.(2013) Anti-Crisis.DurhamNC:DukeUniversityPress. Roitman,J.(2021) ‘“AfricaRising”:questiondeclasseoudefinance?’ , PolitiqueAfricaine 161–2:205–26. Rudnyckyj,D.(2018) BeyondDebt:Islamicexperimentsinglobalfinance.ChicagoIL:UniversityofChicago Press.

Runde,D.(2015) ‘Ensuringthebank’srelevance’ , Forbes,16March <https://www.forbes.com/sites/ danielrunde/2015/03/16/ensuring-world-bank-relevance/?sh=77590ad57feb>. Samuel,B.(2011) ‘Calculmacroéconomiqueetmodesdegouvernement:lescasdelaMauritanieetdu BurkinaFaso’ , PolitiqueAfricaine 124(4):101–26.

Sassen,S.(1991) TheGlobalCity:NewYork,London,Tokyo.PrincetonNJ:PrincetonUniversityPress.

Shipton,P.M.(2010) CreditBetweenCultures:farmers,financiers,andmisunderstandinginAfrica.NewHaven CT:YaleUniversityPress.

Stiglitz,J.E.andH.Rashid(2013) ‘Sub-SaharanAfrica’ssubprimeborrowers’ , ProjectSyndicate,25June <https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/sub-saharan-africa-s-subprime-borrowers-byjoseph-e–stiglitz-and-hamid-rashid-2013-06>.

Swainson,N.(1977) ‘TheriseofanationalbourgeoisieinKenya’ , ReviewofAfricanPoliticalEconomy 4(8): 39–55.

SWIFT(2018) AfricaPayments:insightsintoAfricantransactionflows.WhitePaper.LaHulpe,Belgium:SWIFT. Availableat <https://www.swift.com/swift-resource/170536/download?language=en>.

Sylla,N.S.(2014) ‘FromamarginalisedtoanemergingAfrica?Acriticalanalysis’ , ReviewofAfricanPolitical Economy 41(S1):S7–S25.

Tignor,R.(1998) CapitalismandNationalismattheEndofEmpire:stateandbusinessindecolonizingEgypt, Nigeria,andKenya,1945–1963.PrincetonNJ:PrincetonUniversityPress.

Uche,C.U.(1996) ‘CreditdiscriminationcontroversyinBritishWestAfrica:evidencefromBarclays (DCO)’ , AfricanReviewofMoneyFinanceandBanking 1–2:87–106.

Vallée,O.(2011) ‘L’Économiqueafricainsaisiparlafinance’ , PolitiqueAfricaine 124(4):67–86. Withagen,R.(2021) ‘WhatdoesAfrica’sprivateequitylandscapelooklikein2021?’ , TheAfricaReport, 8July <https://www.theafricareport.com/105738/what-does-africas-private-equity-landscape-looklike-in-2021/>

WorldBank(1981) AcceleratedDevelopmentinSub-SaharanAfrica:anagendaforaction.WashingtonDC: WorldBank.

WorldBank(2015) FromBillionstoTrillions:transformingdevelopmentfinance.WashingtonDC:WorldBank. Yount-André,C.(2021) ‘Convergingcrisesamidst “atmospheric” fragility:ethicalinvestingandkinship calculationsinDakar,Senegal’.PaperpresentedattheGermanAnthropologicalAssociation(GAA/ DGSKA)annualmeeting.

Zwanenberg,R.M.A.vanandA.King(1975) AnEconomicHistoryofKenyaandUganda,1800–1970.Atlantic HighlandsNJ:PalgraveMacmillan.

JamesChristopherMizes isanIFRISpostdoctoralresearchfellowattheInstitutdeRecherche InterdisciplinaireenSciencesSociales,UniversitéParis-Dauphine.

KevinP.Donovan isananthropologistandhistorianattheCentreofAfricanStudies,Universityof Edinburgh.

Citethisarticle: Mizes,J.C.andDonovan,K.P.(2022). ‘CapitalizingAfrica:highfinancefrombelow’ . Africa 92,540–560. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972022000444