PALM OIL TRIBUNE

Sustainability

Harnessing the Power of Methane from Palm Oil Mill Effluent

Seeds of Legacy: The Oil Palm’s Story

PALM KERNEL OIL EXPELLER

Next Chapter Media

DISCLAIMER:

FRONT COVER BY MUAR BAN LEE GROUP BERHAD

Next Chapter Media's editorial team strives to provide accurate and reliable information. However, we recommend that readers independently verify the claims and information presented in our publications. Next Chapter Media is not responsible for the accuracy of the content and encourages readers to use their own judgment when evaluating the information.

kelly@maps-globe.com

DIRECTOR

Emily Yu

PUBLICATION

Maps & Globe Specialist Distributor Sdn. Bhd (625396-A) No 3-1 Jalan Perdana 10/6, Pandan Perdana, 55300 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Fong Wah Printing Sdn. Bhd. (1406717K) No. 17, JaIan Tembaga SD 5/2G Perindustrian Bandar Sri Damansara, Pekan Kepong, 52200 Kuala Lumpur

Malaysia will tighten enforcement against fraud in the used cooking oil (UCO) industry, Deputy Plantation and Commodities Minister Datuk Chan Foong Hin told Reuters, as Western regulators scrutinise whether Asia's UCO shipments contain ‘virgin’ oil.

MPOB is reviewing standards and policies to enhance traceability and prevent discrepancies in UCO and sludge palm oil (SPO) exports. "Ensuring full supply chain traceability is key to combating fraud and maintaining Malaysia’s reputation as a responsible exporter," Chan said.

Concerns over fraudulent UCO exports have grown a er the European biodiesel industry agged a surge in Chinese imports allegedly mis-declared as recycled oil but actually made from virgin sources. Last month, Indonesia, the world’s top palm oil producer, restricted UCO and palm oil residue exports, citing excessive shipment volumes suggesting crude palm oil (CPO) adulteration.

Govt to crack down on fraud in used cooking oil export

(15 February 2025)

In August, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency launched investigations into at least two renewable fuel producers over potential use of fraudulent biodiesel feedstocks to claim government subsidies. Chan also rea rmed Malaysia’s commitment to sustainability, noting 87% of its palm plantations are MSPO-certi ed. He dismissed a decline in palm oil shipments to India as temporary, citing sustained demand from its 1.45 billion population.

MPOB targets 90% of smallholders to achieve MSPO certi cation by end of next year, strengthens with SIMS

(11 November 2024)

MPOB aims to certify over 90% of independent smallholders (ISH) under the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) standard by the end of next year. Currently, 76.9% of the 210,891 licensed ISH are MSPO-certi ed.

MPOB supports smallholders through nancial aid, technical assistance, and awareness campaigns on sustainability. A key initiative is the Sawit Intelligent Management System (SIMS), which enhances monitoring of palm oil transactions, ensuring greater transparency and traceability across the supply chain.

To encourage certi cation, MPOB fully funds the MSPO audit process and provides essential inputs such as training, personal protective equipment (PPE), and pesticide storage facilities. ese e orts ease the nancial burden on smallholders and promote sustainable practices.

e MSPO certi cation strengthens Malaysia’s market position, particularly in the European Union (EU), the third-largest importer of Malaysian palm oil. Recognizing this, the government allocated RM50 million in the 2025 budget for MSPO certi cation and RM15 million to counter anti-palm oil campaigns.

By integrating technology like SIMS and nancial support, MPOB reinforces Malaysia’s commitment to sustainable palm oil production, ensuring compliance with global standards while improving marketability.

Malaysia is calling on investors, particularly from China, to explore opportunities in its agri-commodities sector, with crude palm oil (CPO) as a key focus. Speaking at the Malaysia-China Summit 2024, Plantation and Commodities Minister Datuk Seri Johari Abdul Ghani highlighted potential collaborations between the two nations. Johari identi ed 3 priority areas for investment: biomass and biogas energy, sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), and oleochemical plants in Sabah and Sarawak. He emphasised leveraging the circular economy by converting palm oil waste into green energy, noting that mills with 60-tonne per hour capacity could generate 5–7 MW of power. Full adoption across Malaysia's mills could produce 2,200 MW.

Malaysia Invites Chinese Investment in Palm Oil

(18 December 2024)

On SAF, Johari announced plans to mandate sustainable jet fuel for ights to Malaysia by 2027, positioning the country as a leader in SAF production due to its abundant feedstock and biofuel expertise. With 55% of Malaysia’s oil palm area in Sabah and Sarawak, Johari urged investors to establish oleochemical plants, as none exist in these states. He also encouraged upgrading outdated palm oil mills, integrating AI and automation to boost e ciency. Malaysia’s palm oil sector bene ts from strong infrastructure, sustainability certi cation (MSPO) and R&D capabilities. Johari assured investors of secure feedstock supply and a stable regulatory environment, positioning Malaysia as a prime partner for China in palm oil amid global uncertainties.

Stronger Together: Solidarity Among Palm Oil Producers

(19 January 2025)

Columnist Joseph Tek, in the Borneo Post, underscores the importance of solidarity among palm oil producers, especially in light of lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Malaysia, with 5.61 million hectares of oil palm, represents 17% of its land bank and contributes 20% of global edible oil exports. Oil palms are highly productive and essential to the global food system, making unity among producers crucial for maintaining sustainability and advocating for a level playing eld.

e COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the power of solidarity in the Malaysian palm oil industry. During the crisis, industry associations united, ensuring both safety and business continuity. ey created detailed COVID-19 SOPs, ensuring safety and operational e ciency, which were shared with other palm oil-producing countries, showing global unity.

is collaboration should continue beyond the pandemic, tackling issues such as labour, sustainability, and market access. By working together, producers can improve research, sustainability, and address misconceptions about palm oil. As global demand rises, cooperation is essential for ensuring a sustainable future.

e Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries (CPOPC), established in 2015, epitomises global collaboration, advocating for sustainable progress and addressing shared challenges. e future of the palm oil industry relies on continued unity. As Benjamin Franklin wisely said, “We must, indeed, all hang together, or most assuredly, we shall all hang separately.”

CPOPC Projects Higher Palm

Oil Production and Demand in 2025

(13 February 2025)

e Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries (CPOPC) forecasts increased palm oil production in 2025 across Malaysia, Indonesia, Honduras, and Papua New Guinea. However, Indonesia’s growth will be marginal due to stagnant yields, aging trees, and low replanting rates. Weather uncertainties, including wet conditions in late 2024 and early 2025 and a transition to El Niño-Southern Oscillation-neutral by mid-year, may impact yields. Demand is expected to remain strong, driven by Indonesia’s biodiesel expansion, stock replenishment in China and India, and limited alternative vegetable oil supplies. Growth in ASEAN and Africa, especially in Egypt, Kenya, and Nigeria, will further support demand. Palm oil is projected to trade at a premium over soybean oil, with prices ranging from US$1,000 to US$1,200 per tonne in Q1 2025 but likely declining in H2 2025 due to seasonal high production cycles and increased rapeseed and sun ower seed harvesting. Global biodiesel production, including hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO), rose 8.4% to 64.14 million tonnes in 2024, with palm oil comprising 33% of the feedstock. is growth is expected to continue in 2025, supported by rising demand for sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) and biofuel mandates, particularly in Indonesia and Brazil. CPOPC estimates a slight increase in biodiesel feedstock use in 2025, with palm oil rising 3.5%. Sustainability initiatives in transport, aviation, and maritime industries will further drive the biofuels sector.

EU is set to revise its palm oil-based biofuel rules

(17 January 2025)

e European Union (EU) will revise its palm oil-based biofuel rules following a World Trade Organisation (WTO) ruling that part of its Renewable Energy Directive (RED III) discriminated against Indonesia’s palm oil exports. e WTO's January 10 decision was a signi cant win for Indonesia, the world’s largest palm oil producer, in its ongoing dispute with the EU over biofuel trade restrictions.

Indonesia led the case in 2019 a er the EU classi ed palm oil-based biofuel as “high risk” due to deforestation concerns and announced plans to phase it out between 2023 and 2030. Although the WTO upheld the classi cation of palm oil biofuel as high-risk, it found issues with the EU's implementation of the policy. e WTO ruled that the EU’s 2019 Delegated Regulation 2019/807 was inconsistent with international trade rules and criticized French tax incentives that favoured rapeseed and soybean biofuels over palm oil-based ones, calling them discriminatory.

e EU has pledged to address these issues and align its policies with WTO obligations, with changes expected within 60 days unless appealed. Indonesia argued that the RED unfairly targeted palm oil while bene ting EU-produced biofuels.

Professor Datuk Dr. Ahmad Ibrahim highlights the palm oil industry's recent success, with prices stabilizing around RM5000 per ton, partly due to early investments in biofuels. However, a key challenge remains: increasing palm oil yield, which has stagnated at around 4 tons per hectare. While some companies have achieved higher yields, the industry as a whole is lagging behind competitors like soybean and sun ower oil.

Increasing yield is top agenda for palm oil

(29 January 2025)

In Malaysia, where plantation areas are nearing 6 million hectares, improving yield is the only way to increase production. ough research suggests palm oil yields could theoretically reach 17 tons per hectare, this goal remains elusive. Factors in uencing yield include fertilization, disease prevention, and the quality of planting material. e TENERA variety, a cross between DURA and PSIFERA, is widely used, but uniformity in planting material has been a challenge, and high costs hinder the adoption of newer technologies like genomic screening. Soil fertility, climate change, and economic pressures also a ect yield. Smallholders, who dominate production, face challenges in accessing quality inputs, further limiting productivity. Closing the yield gap requires investment in research, high-yielding varieties, and support for smallholders. Precision agriculture and technology can improve yields, but their adoption is hindered by costs and infrastructure gaps. Governments, industries, and smallholders must collaborate to balance productivity with sustainability and address these challenges.

CPO Prices Expected to Decline Post-Ramadan Amid Rising

(26 February 2025)

Crude palm oil (CPO) futures are projected to decline a er Ramadan due to increased production, particularly from Indonesia, according to Dorab Mistry, director of Godrej International Ltd. Speaking at the Palm and Lauric Oils Price Outlook Conference, he forecasted CPO futures on Bursa Malaysia Derivatives (BMD) to trade between RM4,000 and RM4,600 per tonne from January to March before dropping to RM3,600–RM4,100 per tonne between April and November.

Indonesia’s expected production increase of at least two million additional tonnes and restrictions on used cooking oil (UCO) and palm oil residue exports are key factors in uencing supply. Other price drivers include US tari s, trade policies, energy trends, and the US dollar’s trajectory.

Meanwhile, Mistry predicts soybean oil futures may rise due to US biodiesel policy lobbying, as potential trade shi s under Donald Trump could impact agricultural markets. However, he did not specify a soybean oil price forecast.

Harnessing the Power of Methane from Palm Oil Mill E uent

MALAYSIA'S palm oil industry, which is important for its economy, has long faced environmental concerns associated with Palm Oil Mill E uent (POME). is wastewater, generated primarily from sterilisation, clari cation, and hydro-cyclone operations in palm oil milling, presents signi cant sustainability challenges if not managed properly.

POME is rich in organic matter and, when it decomposes without oxygen, it releases greenhouse gases like methane, which is approximately 27 times more potent than carbon dioxide in terms of global warming over a 100-year period. However, e ectively capturing and utilising methane from POME can mitigate environmental harm while contributing to Malaysia's energy sustainability.

Recognising its environmental impact, Malaysia has started actions to enhance methane capture. Initially, there was a requirement for all palm oil mills to have methane capture systems by 2020. However, this mandate was changed due to operational di culties.

Now, under the current rules, new oil mills constructed a er 2014 must have methane capture systems in place, whereas existing mills with lower production capacities are exempted from this requirements. Currently, around 30% of Malaysia's palm oil mills have adopted methane capture technologies, showing progress but still highlighting the need for further growth.

While some methane capture systems are solely used for aring without further utilisation, most are designed to harness methane for diverse applications.

under the Feed-in Tari (FiT) system. e FiT mechanism o ers a guaranteed price for renewable energy fed into the grid, aiming to incentivise investments in methane capture plants. However, the current FiT rates might not be appealing enough for widespread adoption. e Sustainable Energy Development Authority (SEDA) needs to review the current quotas and FiT rates to enhance the nancial viability of methane capture initiatives.

While capturing methane from POME quali es for carbon credits, renewable electricity produced from methane is not recognised as such by the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market. is exclusion is being debated, especially in the context of Malaysia, where many methane-to-electricity projects would not proceed without the nancial incentive of carbon credits.

With Malaysia’s renewable energy representation being limited—less than 20% of electricity comes from renewables, with a large share still depending on coal and

Photo Courtesy of Muar Ban Lee Group Berhad

On-Site Power Generation

Instead of integrating electricity into the national grid, methane-generated power is sometimes used to supply energy to nearby processing facilities, such as re neries or palm kernel crushing plants.

ese facilities are highly energy-intensive. Without renewable electricity from methane, they would rely on power from the national grid, which is not only costly but also increases their carbon footprint due to dependence on non-renewable energy sources. By utilising methane-generated electricity for internal consumption, these plants can signi cantly reduce both operational costs and, more importantly, their overall carbon footprint.

Products produced in facilities powered by renewable electricity should be considered for premium o erings. Could sustainability certi cation bodies such as the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil recognises this as an added sustainability criterion?

Reducing Reliance on Diesel Generators

Palm oil mills are energy self-su cient, using steam boilers fuelled by biomass for power generation. Typically, boilers operate when milling activities are ongoing, with diesel generators stepping in during non-processing hours.

In some cases, methane is used internally and supplied to steam boilers. Incorporating methane into boiler systems enables extended operation beyond milling periods, thereby reducing dependence on diesel generators.

is approach decreases fossil fuel consumption and signi cantly reduces carbon emissions. Additionally, repurposing methane in boilers allows mills to allocate biomass residues, such as palm kernel shells, for alternative uses or revenue generation.

Palm Kernel Shells (PKS)

Sustainability

Bio-CNG Production and Utilisation

Methane can be upgraded to bio-compressed natural gas (bio-CNG), providing a viable alternative to lique ed petroleum gas (LPG). However, widespread adoption remains hindered by high capital expenditure for upgrading facilities and uncompetitive selling prices to gas companies.

To x these problems, changes in pricing are needed. Gas companies such as Gas Malaysia Berhad, should consider revising bio-CNG pricing structures to improve investment attractiveness. Competitive pricing can incentivise industry participation and support national decarbonisation e orts.

Also, for mills that are far from gas pipelines, using bio-CNG on-site is a useful option. is can power heavy trucks, like crude palm oil tankers, which cuts down operational costs and emissions. A successful bio-CNG plant in Sabah has proven both the viability and economic bene ts of this technology.

World’s First Bio-compressed natural Gas (BioCNG) Commercial Plant from Palm Oil Mill E uent by MPOB, Felda Palm Industries Sdn. Bhd. and Sime Darby O shore Engineering Sdn. Bhd. at Sg. Tengi Palm Oil Mill, Malaysia in 2015

Exploring Co-Digestion with Other Biomass

Co-digestion of POME with other biomass waste like empty fruit bunches (EFB) can boost methane production. Historically, the complex lignocellulosic structure of EFB posed challenges for anaerobic digestion. However, advancements in biotechnological solutions, such as specialised enzymes, now allow for the hydrolysis of these complex components into simpler forms, facilitating more e cient digestion.

Mixing EFB into the digestion process can greatly raise methane production, making methane plants more economically viable and supporting better waste management. It is, therefore, time to revisit the concept of co-digestion.

Malaysia's journey in transforming methane from POME from an environmental liability into a renewable energy resource shows its dedication to sustainable progress. While some advancements have happened, continued e orts are essential to expand methane capture across all mills, optimise utilisation strategies, and implement supportive policies, especially from authorities. By doing so, Malaysia can harness the full potential of POME-derived methane, contributing to environmental conservation and energy sustainability.

Reproduced from Norrrahim et al. (2021). Greener Pretreatment Approaches for the Valorisation of Natural Fibre Biomass into Bioproducts.

Eur Ing Hong Wai Onn, a chartered engineer and chartered environmentalist, is a Fellow of the Institution of Chemical Engineers, the Royal Society of Chemistry, and the Malaysian Institute of Management.

Empty fruit bunches (EFB)

Seeds of Legacy: e Oil Palm’s Story

By Joseph Tek Choon Yee

During my undergraduate studies in Botany at UKM, I embarked on an enlightening exploration of the realms of Taxonomy and Ethnobotany. Taxonomy, with its meticulous science of naming, describing, and classifying all forms of life o ers a profound understanding of the natural world. Yet, while taxonomy provides a structured view of life's diversity, it was Ethnobotany that truly captivated me. Ethnobotany is a mesmerising eld that delves into the intricate relationship between humans and plants. It’s more than just a study of plant uses; it’s a celebration of how indigenous cultures have seamlessly woven plant knowledge into their lives. is eld reveals how plants are integral not only for medicine and sustenance but also for rituals and cultural practices. rough Ethnobotany, we gain insights into the rich tapestry of cultural narratives and traditional wisdom that have been passed down through generations, highlighting the profound connections between people and the plant world.

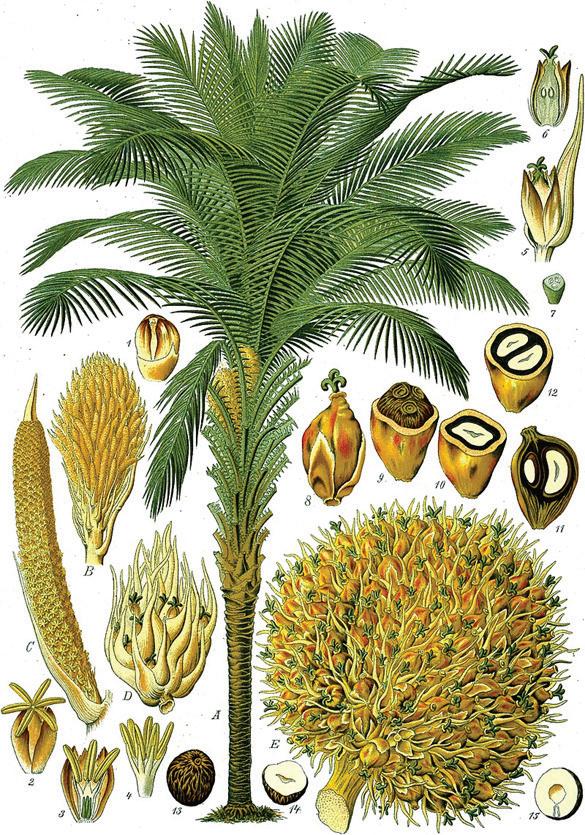

Among the many fascinating plants studied in ethnobotany, the oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) fascinated me and stands out as a symbol of both economic and cultural importance. My enthusiasm for unravelling the ethnobotanical and the historical narrative of the oil palm is driven by its dual role as a vital economic resource for Malaysia and a repository of knowledge. Understanding the oil palm’s ethnobotanical story not only sheds light on its economic impact but also reveals the deep-rooted social and cultural signi cance it holds.

Credit: Adapted from Universi Orbis Seu Terreni Globi In Plano E gies Cum privilegio. Publication Antwerp / 1571 (1578)

Oil palms are ubiquitous today, providing more edible fat than any other plant and featuring prominently in countless products - from cooking oil, cosmetics like lipstick to everyday items like cookies. e oil palm’s global journey began in the 19th century, transforming from a humble plant to a major economic force.

However, their journey onto the global stage began in the holds of slave ships and saw them become a cornerstone of the Industrial Revolution. Historical records from the mid-15th century indicate that European explorers encountered palm oil as a local food source in West Africa. By the 16th and 17th centuries, red palm oil had become a crucial trade commodity within the Atlantic slave trade, highlighting its growing importance. e British Industrial Revolution of the 18th century further escalated the demand for palm oil, particularly for candle-making and machinery lubrication. During this period, palm oil became a key ingredient in products like Lever Brothers' "Sunlight" soap and the American Palmolive brand, underscoring its signi cance in industrial applications.

e 19th century witnessed the establishment of European-run plantations in Central Africa and Southeast Asia. German investment in Cameroon was instrumental in discovering the high-yielding Tenera breed of oil palms, which now dominates global planting with Tenera or DxP planting materials. e oil palm’s journey into Southeast Asia began with four seedlings planted at the Bogor Botanic Gardens in Java, Indonesia, in 1848. ese seedlings, whose exact origins remain somewhat mysterious, were believed to have travelled from West Africa to Amsterdam before reaching Bogor in Java. Two seedlings came directly from Amsterdam, while the other two likely passed through Mauritius or Réunion. Despite their varied routes, all four palms exhibited similar growth and fruit characteristics, suggesting a well-preserved lineage.

Initially planted as ornamental specimens on tobacco estates near Deli in Sumatra, these palms were known as the ‘Deli palm.’ Although they were admired for their beauty, it took time for their potential as an agricultural crop to be recognised. e transition from ornamental use to large-scale plantation cultivation marked the beginning of a new chapter in the history of oil palm cultivation. Today, the legacy of those four Bogor seedlings is re ected in the vast and thriving oil palm plantations that span Southeast Asia, shaping economies and landscapes across the region.

Returning to Africa, the oil palm’s signi cance as Elaeis guineensis is deeply rooted in the cultural and economic fabric of West and Central Africa. is remarkable tree has been integral to daily life for millennia, providing not only a staple cooking ingredient but also a profound connection to tradition and survival. By the late 1800s, palm oil was a primary export for several West African nations, re ecting its immense value. Although its prominence was later overshadowed by cocoa during the colonial era, palm oil’s impact endures. It remains a crucial dietary element, celebrated for its rich, reddish pulp that yields oil abundant in carotene, a vital precursor to vitamin A. In fact, crude palm oil is one of the richest natural plant sources of carotenes. It has 300 times more provitamin A than tomatoes.

Palm wine, another cherished product derived from the oil palm, holds a special place in African cultures. e sap, tapped from the palm’s crown, is a vital source of vitamin B and serves as an emblem of local tradition and cra smanship. Traditional methods of palm wine production involve tapping the sap and allowing it to ferment, creating a beverage that is both culturally signi cant and nutritionally valuable. However, this practice faces challenges in Africa, such as the destructive felling of trees for wine production. E orts are underway to balance tradition with sustainability, preserving the delicate equilibrium between cultural practices and environmental stewardship.

I vividly recall an encounter with a Nigerian visitor during my time as an oil palm breeder. is individual possessed an extraordinary skill: he claimed that he could visually identify which oil palm trees were more proli c in sap production. His deep-rooted knowledge, passed through generations. Imagine the impact of having such expertise to pinpoint the most productive trees for sap extraction, ensuring a successful palm wine venture.

In tropical Africa, the oil palm is not just a source of oil but also a symbol of resilience and ingenuity. e central shoot, or "cabbage," is edible (in Malaysia, we call as ‘umbut’ sawit, used in recipes with gulai santan or with belacan or cili padi!), while the palm’s leaves are used for thatching, fencing, and cra ing strong bres for shing lines and cordage. e wood and leaves also contribute to local industries and religious practices, showcasing the palm’s multifaceted contributions to daily life.

e oil palm’s in uence extends beyond its African origins. Introduced to the Americas through the trans-Atlantic slave trade, it established itself in Brazil and the West Indies. Despite the rich Neotropical ora, where local species were preferred, oil palm found a place in the New World’s agricultural and medicinal practices. e oil palm’s adaptability and value ensured its continued spread, even as detailed records of its use in the Americas remain less comprehensive.

e journey of Elaeis guineensis from its African roots to global prominence is a testament to its remarkable adaptability and enduring importance. Its story is not merely one of agricultural success but a vibrant tradition that continues to shape the lives of people around the world. e oil palm’s legacy as a vital and land-e ciency food source, cultural icon and economic powerhouse endures, re ecting a living tradition that connects people across continents and generations – a global shared destiny.

Credit: Elaeis guineensis - Köhler–s Medizinal-P anzen. Created: 1897. Source:Wikipedia

5th International Oil Palm Biomass Conference 2025 MATRADE Exhibition, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

14 - 15 April

15th PALMEX Indonesia 2025 (PALMEX Jakarta)

Jakarta International Expo (JIEXPO), Kemayoran, Jakarta, Indonesia

14 - 15 May

MPOA Annual Dinner

One World Hotel, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia

17 May

AgTech International Expo

Setia City Convention Centre, Shah Alam

21 -23 May

Andalas Forum VI 2025

SKA Convention Exhibition, Pekanbaru, Riau, Indonesia

22 -23 May

Malaysia Palm Oil Expo (MAPEX) 2025

Dewan Hakka Sandakan, Sabah, Malaysia

11 - 12 June

Palm Oil TechConnect: Advancing Global Mechanization and Automation Miri, Sarawak, Malaysia

TBC July

3rd T-POMI Technology & Talent Palm Oil Mill Indonesia 2025

Holiday Inn Bandung Pasteur, West Java, Indonesia

8 - 10 July

17th National Seminar (NATSEM) 2025

Berjaya Waterfront Hotel, Johor Bahru, Johor, Malaysia

14 - 16 July

11th Indonesia International Palm Oil Machinery & Processing Technology Exhibition 2025 (INAPALM ASIA 2025)

Jakarta International Expo (JIEXPO), Kemayoran, Jakarta, Indonesia

29 - 31 July

Asia Palm Oil Thailand 2024 CO-OP Exhibition Centre, SuratthanI, Thailand

7 - 8 August

3rd Sawit Indonesia Expo (SIEXPO) 2025 Pekanbaru Convention & Exhibition Riau, Indonesia

7 - 9 August

Palm Oil TechConnect: Advancing Global Mechanization and Automation

Sandakan, Sabah, Malaysia

TBC August

8th Malaysia International Agriculture Technology Exhibition MITEC Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

11 - 13 September

PALMEX Medan 2025

Santika Premiere Dyandra Hotel & Convention, Medan, Indonesia

7 - 9 October

Palm Oil TechConnect: Advancing Global Mechanization and Automation

TBC, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

TBC October

21st Indonesian Palm Oil Conference (IPOC) and 2026 Price Outlook

Bali International Convention Centre (BICC), Bali, Nusa Dua, Indonesia

Early November

MPOB International Palm Oil Congress and Exhibition (PIPOC) 2025

Kuala Lumpur Convention Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

18 - 20 November

2nd Unlocking Revenue and Sustainability: Exploring Carbon Credit Opportunities in the Palm Oil Industry 2025 (Biomass Edition)Kuala Resorts World Awana, Genting Highlands, Malaysiai

5 - 6 December

Imagine an oil palm plantation where by-products are turned into valuable resources in the ght against climate change. In Malaysia, the oil palm industry can become a key player in reducing GHG emissions by reusing by-products and capturing carbon. Let’s explore how more players in this sector can change its practices to bene t the environment and tap into the global carbon market, all while creating new revenue streams.

When palm oil is produced, it generates signi cant by-products, such as empty fruit bunches (EFB), palm kernel shells (PKS), bers, and palm oil mill e uent (POME). Traditionally viewed as waste, these materials have been used and are now being better utilised to capture carbon and produce renewable energy. Malaysia’s palm oil sector accounts for about 90% of the country’s biomass, making it vital for reducing emissions and generating carbon credits that can be sold to companies aiming to o set their carbon footprints.

Turning POME into Power: Biogas and Renewable Energy Credits

Biogas production o ers signi cant untapped potential for Malaysia, especially considering the country’s abundant agricultural and industrial waste resources including from oil palm sector. Estimates suggest that Malaysia has about 2,400 MW of biomass and 410 MW of biogas energy potential. However, only a small fraction of this has been realised, with the biogas energy capacity standing at 124 MW in 2023.

One of the key advancements in Malaysia's carbon reduction strategy is the capture of methane from Palm Oil Mill E uent (POME), a highly potent greenhouse gas. By converting this methane into biogas, palm oil mills are able to signi cantly reduce methane emissions while generating Renewable Energy Certi cates (RECs). Each REC represents one megawatt-hour of renewable electricity, thereby helping to cut reliance on fossil fuels and promote cleaner energy.

According to MPOB, 145 out of approximately 450 palm oil mills in Malaysia have now installed biogas trapping facilities. e MPOB has played an instrumental role in advancing biogas capture technologies and was also tasked with overseeing their implementation as part of the National Key Economic Areas (NKEA) under Entry Point Project 5 (EPP5). However, despite these strides, only 36 of these mills currently utilise the trapped biogas to generate electricity, re ecting an area for potential growth. To address this, MPOB is collaborating with SEDA to secure additional grid connection quotas for the industry. is increased access would enable more mills to feed renewable electricity into the national grid, scaling up Malaysia’s renewable energy contributions and enhancing the palm oil sector’s impact on national climate goals.

By Joseph Tek Choon Yee

As part of the drive to expand biogas production, there were new regulatory requirements for palm oil mills. According to MPOB regulation, with e ect from 1st January 2014, new mills and all existing mills which apply for throughput expansion will be mandated to install full biogas trapping or methane avoidance facilities. Any existing mill that seeks to increase its annual processing capacity above 270,000 tons—or any new mill—must install biogas capture systems, methane emission avoidance technology, or both.

e development of carbon credit projects in this space could further drive adoption, particularly ONLY for mills that are not subject to these methane capture regulations. Apparently, approximately 70% of palm oil mills are not yet covered by these mandates, creating an opportunity to achieve "additionality," a concept in carbon markets where only reductions beyond mandated levels can qualify for carbon credits. is opens a pathway for these mills to generate revenue through carbon credits by capturing and reducing methane emissions that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere.

Biochar: Improving Soil and Capturing Carbon

Palm oil biomass can be repurposed as an alternative fuel, further reducing fossil fuel use. Materials like EFB, PKS, and mesocarp bers can be burned to generate electricity or biofuel, signi cantly cutting carbon emissions. is transition supports Malaysia’s renewable energy goals while generating additional RECs.

According to MPOB, Malaysia’s palm oil industry holds signi cant potential for decarbonisation through biomass utilisation. In 2023, MPOB estimated that the industry could generate 2,300 megawatts (MW) of renewable energy from biomass by-products such as Empty Fruit Bunches (EFB), Mesocarp Fibers (MF), and Palm Kernel Shells (PKS). is energy production has the potential to o set substantial GHG emissions, with projected 13.43 million tons of CO2 equivalent annually, based on a rate of 0.695 tons of CO2 equivalent per megawatt-hour (MWh) of electricity generated.

is biomass-based renewable energy not only provides an e ective means of reducing emissions but also supports Malaysia’s broader goals to diversify its energy mix and reduce reliance on fossil fuels. By capitalising on these by-products, the palm oil industry can transform waste into a powerful asset for sustainable energy, further contributing to Malaysia’s climate targets and positioning the sector as a key player in the transition toward a low-carbon economy.

Capturing Carbon with Advanced Technologies

e industry can also explore Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies to minimise emissions. CCS captures CO2 emissions from production processes and stores them underground or repurposes them. One e ective method is Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), which involves converting palm oil by-products into energy while capturing and storing the CO2 produced. is could enable the industry to become a net carbon remover, actively pulling carbon from the

Building a Circular Economy: Reusing,

e palm oil industry is adopting a circular economy model, emphasizing resource reuse and waste reduction and by-product

For example: POME Treatment in capturing methane from POME generates biogas and renewable energy; and Recycling By-products where pruned oil palm fronds and trunks can serve as mulch, while palm kernel shells can be repurposed as fertiliser.

Biomass as an Alternative Fuel

Challenges and Opportunities in Biomass Use in Palm Oil Mills

e use of biomass as an energy source in palm oil mills presents several challenges, which explain why it hasn't been more widely adopted despite its potential. Biomass has a low calori c density, meaning it doesn't provide as much energy per unit as other fuels. To make biomass usable for energy production—whether thermal or electrical—additional processing is required, including shredding, drying, and pelletizing. Furthermore, boilers must be speci cally designed to handle biomass and must be regularly cleaned of ash, adding to maintenance costs and operational complexity.

While boiler technology has improved, there is still room for further advancements. Mills looking to shi to biomass will need to invest in upgrading their equipment, which represents a signi cant capital expense. To support this transition and help achieve Malaysia’s net-zero carbon target, the government could provide matching grants or other enticing reinvestment incentives to assist palm oil mills with this necessary capital. Such reinvestment is crucial for the industry's shi to more sustainable energy sources.

Achieving net-zero carbon emissions o ers several important bene ts for the palm oil industry. e sector has long been criticised for contributing to deforestation, despite its past and ongoing sustainability e orts. By committing to net-zero emissions, the industry can better counter these negative perceptions while further strengthening its sustainability credentials.

As countries and corporations become more focused on reducing their carbon footprints, the demand for products with a smaller environmental impact and footprint will grow. Although companies are not yet required to report their Scope 3 emissions (which includes supply chain emissions), some are choosing to do so voluntarily. is is especially true for companies whose supply chains represent a signi cant portion of their emissions in global market. As a result, countries and businesses will increasingly favour net-zero carbon palm oil as a preferred sourcing option, which can provide Malaysian palm oil a competitive advantage in global markets.

Business Decisions

Ultimately, adopting net-zero carbon initiatives in the palm oil industry will be a business decision, shaped by both mandatory regulations and voluntary commitments. Businesses will need to assess the long-term costs and bene ts of transitioning to cleaner technologies, factoring in upfront capital investment, ongoing operational costs, and potential incentives or penalties including carbon tax. e decision will be driven by a combination of regulatory pressure and the recognition that sustainability can enhance brand value for bigger planters, perhaps better access to new markets, and long-term pro tability – but remain cautiously pegged to its competitiveness. is decision-making process will involve a careful evaluation of the business case for adopting net-zero practices. While the costs may be signi cant in the short term, the long-term bene ts could make it a worthwhile investment. In this context, the palm oil industry can play a key role in achieving Malaysia’s climate goals while simultaneously securing its future growth.

e Malaysian government has made ambitious commitments to climate change mitigation, and nding ways to meet these goals will require innovation and collaboration across businesses and industries. e palm oil sector, a cornerstone of the Malaysian economy, can play a crucial role in this e ort. With the right mix of regulatory support, nancial incentives, and clear long-term business strategies, the industry could achieve net-zero carbon emissions sooner than expected—potentially well before 2050. By embracing net-zero carbon initiatives, the palm oil industry can not only contribute to national climate goals but also improve Malaysia’s global reputation as a leader in sustainable palm oil production. e decision to invest in sustainability, balanced against the cost-bene t of long-term growth, will ultimately help de ne the industry’s future.

Palm Oil Sector in Going Forward with Carbon Market

e Malaysian government is supporting the carbon market initiatives through policies like the Bursa Carbon Exchange (BCX) and regulations requiring methane capture. is support enables the palm oil sector to engage with international carbon markets, allowing for the sale of carbon credits and International Renewable Energy Certi cates (i-RECs) that meet global sustainability standards. However, challenges remain. Ensuring that carbon credits are veri ed and meet international standards is crucial. e transition to technologies like biogas and biochar requires signi cant investments, and reliable infrastructure for carbon trading is essential. Nonetheless, the palm oil sector must stand ready to adapt and invest in its future.

It became clear from attending the seminar that stakeholders in the palm oil supply chain will face a transitional phase as they try to navigate the complexities of carbon trading and related ecosystem, especially while dealing with their ongoing operational challenges they already face. With all the technical jargon and intricate details, it’s evident that fully understanding the subject matter will take considerable time and e ort. However, one thing is certain—mandatory regulations will eventually force stakeholders to participate and comply, whether they are ready or not.

It is also important to note that not all green or climate-friendly projects automatically qualify for carbon credits. To be eligible, a project must follow an approved methodology under a recognised carbon credit standard programme. ere are methodologies that outline speci c requirements for eligibility and provides guidelines for calculating emissions reductions or removals. Only projects that meet these stringent criteria can issue carbon credits, ensuring that the credits represent real, measurable, and additional bene ts for the climate.

While the initial learning curve may be steep, the hope is that, over time, stakeholders will acquire the knowledge needed to e ectively navigate the carbon related landscape. is process to invest will require careful business decision-making, as companies will need to evaluate the costs and bene ts of adopting decarbonisation practices. ough the upfront costs may be signi cant, the long-term nancial and reputational rewards could make the investment worthwhile. If they manage this transition successfully, stakeholders could unlock new revenue streams and strengthen the sustainability credentials of the Malaysian palm oil industry. at said, how smoothly this shi will occur—and whether it will lead to real, lasting change—remains to be seen.

rough participation in carbon markets, Malaysia’s palm oil industry is not just producing edible oil; it is actively combating climate change. By turning by-products and waste into energy, capturing carbon, and selling carbon credits, the industry is paving the way for an enhanced sustainable future. ese e orts generate income and contribute to Malaysia’s carbon reduction goals, further showcasing the palm oil sector as a model for sustainable agriculture globally.

us, as the industry continues to innovate and adopt green technologies, it strengthens both Malaysia’s economy and its commitment to environmental sustainability. e journey toward a low-carbon future is underway, proving that sustainability and pro tability can go hand in hand.

KEY PALM OIL MID & DOWNSTREAM STAKEHOLDERS: MINISTRY, ITS AGENCIES AND RELATED ASSOCIATIONS

MALAYSIA

Ministry of Plantation and Commodities (KPK) www.kpk.gov.my

Malaysia Biomass Industries Confederation (MBIC) http://www.biomass.org.my

Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) www.mpob.org.my

Malaysian Palm Oil Association (MPOA) www.mpoa.org.my

Malaysian Oleochemical Manufaturers' Group (MOMG) www.momg.org.my

Badan Pengelola Dana Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit (BPDPKS) Indonesian Palm Oil Plantation Fund Management Agency https://www.bpdp.or.id/

Asosiasi Produsen Oleochemical Indonesia (APOLIN) Indonesian Oleochemical Producers Association https://apolin.org/

Malaysian Palm Oil Council (MPOC) www.mpoc.org.my

The Federation of Palm Oil Millers Association of Malaysia (POMA)

Malaysian Biodiesel Association (MBA)

Malayan Edible Oil Manufacturers' Association (MEOMA) meoma.org.my/v1

INDONESIA

Gabungan Pengusaha Kelapa Sawit Indonesia (GAPKI) Indonesian Palm Oil Association https://gapki.id/en/

Asosiasi Produsen Biofuel Indonesia (APROBI) Indonesian Biofuel Producers Association https://www.aprobi.or.id/

Indonesian Oil Palm Research Institute (IOPRI) Pusat Penelitian Kelapa Sawit (PPKS) https://iopri.co.id/

Gabungan Industri Minyak Nabati Indonesia (GIMNI) Indonesian Vegetable Oil Industry Association https://gimni.org/

Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) www.mspo.org.my

Palm Oil Re ners Association of Malaysia www.poram.org.my

Malaysian Oil Scientists' and Technologists' Association (MOSTA) mosta.org.my

Palm Oil Agribusiness Strategic Policy Institute (PASPI) https://palmoilina.asia/

Indonesian Biomass Energy Masyarakat Energi Biomassa Indonesia (MEBI) https://mebi.or.id/

Hosted by :

Co-host:

Suppor ted by :

Organised by :

Seminar Registration: