PALM OIL TRIBUNE

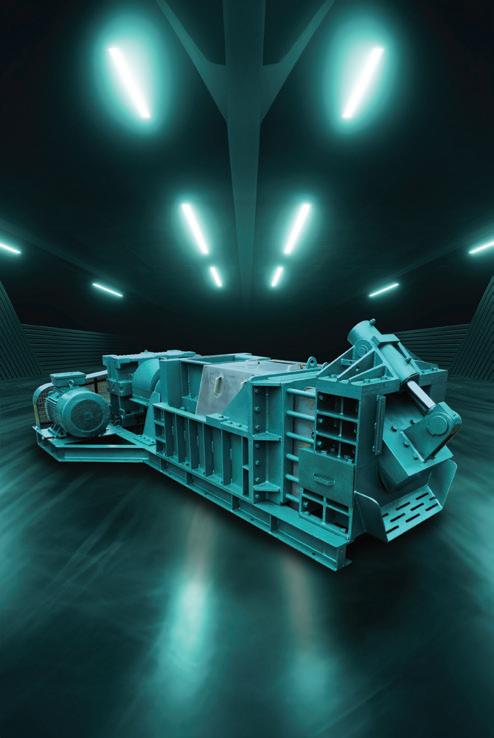

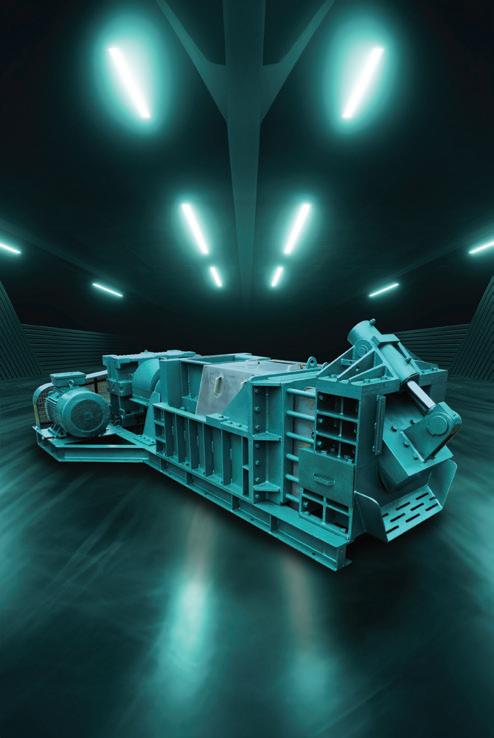

2 In 1 EFB

Cutter Press

Expert’s Insight

From contaminants to cash: Enhancing millers’ revenue with secondary oils

Interview

Oil palm industry remains the biggest earners in Papua New Guinea

2 In 1 EFB

Cutter Press

Expert’s Insight

From contaminants to cash: Enhancing millers’ revenue with secondary oils

Interview

Oil palm industry remains the biggest earners in Papua New Guinea

e factory located in Roing, in the Lower Dibang Valley of Arunachal Pradesh, advances Mission Palm Oil, representing a pivotal step in India's journey towards self-reliance in edible oils, catalyzed by the National Mission on Edible Oils - Oil Palm (NMEO-OP).

is integrated oil palm project includes a state-of-the-art oil palm factory (Palm Oil Processing and Re nery), a zero-discharge e uent plant, a palm waste-based power plant, and additional structures and go-downs for support purposes.

is factory is the rst oil palm factory in Arunachal Pradesh and India's rst oil palm factory under NMEO-OP. is initiative marks a signi cant step towards achieving self-reliance in edible oils and empowering farmers, particularly in the Northeast region.

Arunachal Pradesh alone has identi ed 130,000 hectares of suitable land for oil palm cultivation, with the Northeast region holding 33% (960,000 hectares) of the designated area. However, only 4% of this potential has been utilized for oil palm development.

India currently imports 96% of its required palm oil, which constitutes 67% of the country’s edible oil import bill, exceeding Rs. 1 Lakh crore (one trillion rupees). e NMEO-Oil Palm Policy aims to reduce this dependency through the promotion of domestic cultivation, particularly in the Northeast. @Source: Bikash Singh, e Economic Times

Cenergi SEA Bhd (Cenergi) and Kwantas Corporation Bhd (Kwantas) inked their rst biomass development joint venture (JV) partnership in Lahad Datu, Sabah during a simple ceremony here recently.

Cenergi and Kwantas will jointly undertake the development, construction, operations and maintenance of a Bio Compressed Natural Gas (BioCNG) plant located at Kwantas’ Pintasan Palm Oil Mill in Lahad Datu that is expected to be operational by the second quarter of 2025.

Cenergi is a subsidiary of UEM Group Bhd while Kwantas is a Sabah-based integrated palm oil producer involved in the entire palm oil supply chain business with a presence in Malaysia and China.

According to a statement by Kwantas, the plant will generate biogas through anaerobic digestion of POME (Palm Oil Mill E uent) and through a process of puri cation and compression of the biogas, convert the biogas into BioCNG.

BioCNG has gas composition similar to that of natural gas, enabling it to be used in the same way for heating and power, it said. e BioCNG produced by this facility will be compressed into cylinder tubes and supplied to industrial o -takers in Lahad Datu via trailers that transport the cylinder tubes, the statement read.

BioCNG is considered an environmentally friendly renewable gas derived from wastes of palm oil mills, and it will enable users to reduce their carbon emissions towards their net zero goals, it added.

Cenergi Group CEO Hairol Azizi Tajudin said to date, Cenergi has a portfolio of a total of 33 biogas to electricity plants in Peninsular Malaysia.

is includes those under construction, which harness biogas from palm oil mill e uent and convert it to electricity for injection into the grid through Sustainable Energy Development Authority (Seda)’s Feed-in-Tari programme, he said.

“ is partnership marks Cenergi’s inaugural venture into biogas development in Sabah, and we are excited to play a part in enhancing the renewable energy options available to the industry,” he said.

Kwantas Group CEO Alvin Kwan said their ultimate goal is to reduce carbon footprint and tackle climate change issues by capturing gas emissions from the POME and converting it into sustainable BioCNG to ful ll gas and energy demands in Sabah’s East Coast region.

With the availability of BioCNG, the wide applications of BioCNG could potentially expand to applications in the transportation and manufacturing sector, he said.

Source: Stephanie Lee, e Star

The BioLoop Intelligent Feeding System is a turnkey solution which comprises a robotic arm, automated feeder and an array of conveyor belts to control 4 main functions depalletizing, harvesting, feeding and palletising (Pics courtesy of BioLoop)

Palm oil waste in Malaysia represents a signi cant environmental and management challenge, as the country is one of the world’s largest producers of palm oil.

e industry generates substantial amounts of waste — including empty fruit bunches (EFBs), palm oil mill e uent (POME) and palm kernel shells (PKS). ere are ongoing e orts to manage these wastes more e ectively and sustainably.

BioLoop Sdn Bhd Co-founder and CEO Mah Jun Kit said the strategy involves utilizing biotechnology and Black Soldier Fly Larvae (BSFL) to divert substantial quantities of organic waste from land lls and transform it into valuable products.

e method is signi cantly faster than traditional waste management processes and leads to reduced greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

By repurposing palm oil byproducts, which are typically discarded or le on estates, using them as feed for larvae.

BioLoop uses palm kernel expeller and palm kernel cake to nourish larvae, which subsequently produce both protein and fertilizer.

e approach not only adds value to the byproducts but also signi cantly bolsters the sustainability narrative of palm oil mills.

Apart from that, converting waste into valuable resources such as protein and fertilizer, which can then be reintegrated into the economic system, has the potential to greatly improve global environmental sustainability by fostering a more e ective and circular economy.

Traditional palm oil waste disposal methods typically involve leaving waste on the estate as compost or selling it as low-value feedstock to sheries and cattle farms.

While these methods are bene cial, it does not fully capitalize on the waste’s potential value.

BioLoop leverages the waste in a more innovative way by using it to cultivate larvae, which are extremely rich in protein and subsequently produce high-quality organic fertilizer.

It also strategically forms joint ventures with companies along its value chain to ensure a sustainable, long-term source of waste and o ake, which is critical from a business perspective.

Despite the presence of several BSFL companies in Indonesia, Mah said Malaysia’s palm oil technological innovations are increasingly recognised and adopted across the region, setting the stage for BioLoop’s ambitious long-term growth and sustainability initiatives.

Mah says the govt is encouraging local municipalities to adopt BSF technology for food waste management and providing grants to support these initiatives (Photo by MUHD AMIN NAHARUL/TMR)

Currently processing approximately 20 tonnes of waste daily, the company is looking to expand its capacity to a medium-term goal of handling 100 tonnes per day within the next three to four years.

A key strategy in achieving this involves forming a partnership with the biogas facility to create co-located sites, which entails establishing operations directly adjacent to palm oil mills.

While initially considering a centralized model where all waste would be transported to a single location, the approach was deemed impractical and costly due to the scattered nature of the mills across Malaysia and the logistics involved.

“We are currently implementing a new project and plan to use this successful model as a showcase to other palm oil mills, inviting them to see our operations and consider a similar setup,” he said.

Source: Aufa Mardhiah, e Malaysian Reserve

International Symposium on Plant Lipids

Lincoln, USA

Ju ly 2024

Sawit Indonesia Expo 2024

Pekanbaru Convention & Exhibition, Ria u

16th National Seminar (NATSEM) 2024

Pullman Miri Waterfron t, Sa rawak, Mala ysia

T-POMI Technologie & Talent Palm Oïl Mill

Indonesia 2024

Holiday Inn Bandung Pasteur, Indonesia

Globoil India 2024

The Westin Mumbai Powai L ake, India

The 7th of Malaysia International Agriculture Technology Exhibition 2024 S etia City Convention Centre, Malaysia

PALMEX Malaysia 2024 KLCC, Malaysia September 2024

World Food Istanbul 2024 Istanbul, Turkey

Food and Kitchen Tanzania

Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania

Oils & Fats International Congress 2024 KLCC, Malaysia

ICIS Pan American Oleochemicals Conference

The Ritz-Carlton Coconut Grove, USA

Heatech Indonesia

Jakarta International Expo, Indonesia

26th Central Asian International Exhibition FoodExpo Qazaqstan

Almaty, Kazakhstan

Biofuels Expo 2024

Renaissance London Heath row Hotel, UK

Food Ingredients

Europe 2024 Frankfurt, Germany

2nd Annual Food Security Asia Congress 2024

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

The 10th Indonesia

International Palm Oil Machinery & Processing Technology Exhibition 2024

Jakarta International Expo, Indonesia

Ju ly

PALMEX Thailand 2024

CO-OP Exhibition Centre, Thailand

China Feed Industry Expo

Nanjing , China

Seminar on Speciality Fats

Konya, Turkey North American SAF Conference & Expo

Saint Paul Rivercentre, USA

Sustainable Aviation Futures North America Congress

Marriot Marquis, USA

Malaysian Palm Oil Forum KL & Gala Dinner

3 October 2024

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

The 14th PALMEX Indonesia 2024

Santika Premiere Dyandra Hotel & Convention, Indonesia

20th Indonesian Palm Oil Conference (IPOC) and 2025 Price Outlook

Bali, Indonesia

Sustainable Aviation Fuetures APAC Congress

Singapore

YABITED Fats and Oils Congress

Antalya, Turkey

Smart Nation Expo 2024 and EVM Asia 2024

MITEC, Malaysia

Coex Food Week 2024 S eoul, S outh Korea

Food Africa 2024 Eg ypt International Exhibition Centre, Eg ypt

2025 Internationa Biomass Conference & Expo

Cobb Galleria Centre, Georgia, USA

Representatives from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) and the European Union (EU) are preparing for the 4th Joint Working Group (JWG) on Palm Oil, underscoring their commitment to collaboration in this critical sector.

is commitment was emphasized during the 31st Meeting of the Asean-EU Joint Cooperation Committee (JCC) held in Jakarta on May 8, where both sides explored avenues for further partnership.

In a joint statement, they stated that the next JWG meeting aims to "continue promoting mutual understanding on the sustainable production of vegetable oils and addressing challenges in this sector in a holistic, transparent, and non-discriminatory manner."

e upcoming JWG builds on previous meetings, including the inaugural session in January 2021, followed by subsequent sessions in June 2022 and June 2023.

Meanwhile, representatives from both sides also acknowledged common transboundary threats to peace, security, and stability in Asean and the EU, including terrorism, violent extremism, and cyber-attacks.

Source: e Star

Panasonic Housing Solutions makes wood boards from old palm trees (Pics courtesy of Panasonic Housing Solutions)

Japanese and Malaysian researchers are testing a process to turn felled palm trees into biomass that serves as a renewable source of energy.

e trunks of felled palm trees are arranged in stacks at a demonstration plant in Kluang, a town in southern Malaysia. e trunks, when fed into a machine, are reduced to heaps of moist, amber ber within seconds. e palm trees are easy to mulch because their elevated water content so ens the wood. e bers are later washed, dried, and converted into small, cylindrical fuel pellets.

Palm trees are 70% to 80% water, meaning they yield large quantities of sap. Because palm sap has sugar content, it can be recycled into fertilizer or sustainable aviation fuel, the plant's representatives say.

e palm tree biomass project was selected in 2018 for a sustainable development research program backed by the Japan Science and Technology Agency and the Japan International Cooperation Agency. e project is led by Akihiko Kosugi of the Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences (JIRCAS). Japanese universities and businesses, such as engineering rm IHI, are participating along with Malaysia's government and the Universiti Sains Malaysia, a major research university.

The experimental plant in the Malaysian town of Kluang mulches palm trunks into amber fibers (Photo by Fumika Sato)

A palm tree decreases its yield a er 25 years or so, necessitating replanting. When old palm trees are felled, they are usually le to decompose under the belief that they would fertilize the soil.

But research shows that felled palm trees become breeding grounds for termites, as well as other insects and fungi, Kosugi said. "We now know they produce methane and other greenhouse gasses," the researcher said.

Tens of millions of palm trees are felled and abandoned each year in Malaysia. Each tonne of palm tree trunk that is cut down produces 1.3 tonnes of greenhouse gasses, Kosugi said. Recycling old palm trees would reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Palm waste is being looked at as a source of biomass for producing energy. But impurities in palm waste can damage boilers or cause res. "It's critical to remove impurities," said Sudesh Kumar, biotechnology professor at the Universiti Sains Malaysia. e Kluang plant removes the impurities, pulverizes long bers into powder and compresses the dust into homogenous pellets.

Palm waste also can be recycled into material for making furniture. Panasonic Holdings subsidiary Panasonic Housing Solutions has developed a production process for making wooden boards out of dead palm trunks.

Production is still in the testing phase, but Panasonic Housing Solutions is providing 15 furniture makers with the boards. Beds and other furniture made from palm trunks have been sold in Japan since 2022. "We're considering using [recycled palm trees] as construction material in the future," a Panasonic Housing Solutions representative said.

Source: Fumika Sato, Nikkei Sta Writer

extraction plants to buy palm fruit from farmers at the rate of at least 4.50 baht per kilogram to prevent prices from falling.

e order was signed by Wattanasak Sur-iam, the department director-general, and sent to the president of the palm oil extraction association.

In the letter, Wattanasak said that o cials from his department had visited a province, which is a large producer of oil palm fruit, and held a meeting with representatives of oil palm farmers, intermediary palm buyers, and oil palm extraction plants.

e order did not reveal the name of the province.

Wattanasak said the meeting resolved to require middle-man buyers to buy the fruit from farmers at a minimum of 4.50 baht per kg.

If the fruit is of premium quality, the buying price must be raised accordingly, the order stated.

e order stated that anyone found to be buying the fruit at below the set price, would face a maximum jail term of seven years, or a maximum ne of 150,000 baht, or both.

e order also required operators of the extraction plants to report their operations to the department on a daily basis. e gures should state the amount of palm fruit purchases, the purchase rate and the quantity of extracted oil.

Source: e Nation

Activated carbon can remove impurities in waste water (Photo by Zhulin Carbon)

Palm kernel shell (PKS) can be converted to activated carbon serving as absorption media due to its high surface area and porosity; it can e ectively adsorb and remove various contaminants and impurities from gasses and liquids solutions. Activated carbon is commonly used for treating industrial wastewater and river pollution, puri cation of oleochemical products, bio-pharmaceutical solutions etc.

Used PKS-based activated carbon can be repurposed and reused as re-activated carbon through carbon regeneration technology to restore its adsorption capability by increasing its iodine value. Conservatively, it can be reused 5 to 8 times depending on the quality of spent carbon.

e global activated carbon market size was valued at USD 5.7 billion in 2021 and is projected to reach USD 8.8 billion by 2026, growing at a CAGR of 9.3% from 2021 to 2026. Bio-based activated carbon potentially serves to replace coal-based activated carbon. It has the potential to reduce carbon footprint and is quali ed as carbon neutral products.

Activated carbon has the potential to meet business demands as a premium product, catering to both overseas and domestic markets for a wide range of industrial applications.

e business model is subject to biomass feedstock availability, especially coconut shells which are currently imported from Indonesia by activated carbon producers due to shortage of coconut shells. A total of 1.25 million tonnes of PKS has been exported overseas in 2022 whilst the rest of the PKS were mainly used as green fuel in the palm oil mills. Bamboo biomass and cocoa pod husks also present good technical properties to be converted to activated carbon based on R&D ndings from the Forest Research Institute of Malaysia (FRIM) and Malaysian Cocoa Board (LKM).

e scalability of the PKS-based activated carbon is very much dependent on a new enabling initiative introduced by the Malaysia Government i.e. using PKS activated carbon for treating POME to reduce chemical oxygen demand (COD) and biological oxygen demand (BOD) levels. PKS-based activated carbon can serve as an alternative to imported coal-based activated carbon for water treatment projects or to reduce river pollution.

Additionally, Malaysia imported 16,622 tonnes of activated carbon valued at RM153 million in 2022 and the total export was RM147 million. Hence, newly developed PKS-activated carbon can also potentially address local demand and reduce import as well as developing circular economy opportunities in Malaysia through reactivated carbon technology.

e Ministry of Plantation and Commodities (KPK) and Malaysia Palm Oil Board (MPOB) to consider introducing and using palm kernel shell (PKS)-based activated carbon for treating POME to reduce its COD and BOD level. e used PKS-activated carbon can be reused again through carbon reactivation technology to restore its adsorption capability by increasing the iodine value.

Reactivated carbon technology should be prioritized as a potential R&D&C&I biomass technology to promote the new circular economy model of PKS, it is proposed that MPOB and relevant industry partners to spearhead this biomass technology R&D&C&I.

PKS-based activated carbon is a high-value integrated circular economy model for the palm oil industry which includes treating POME and puri cation of oleochemicals. It is recommended that palm oil mills joint venture with activated carbon producers to manufacture activated carbon through tax incentives provided by Malaysian Government rather than selling raw PKS as fuel commodity.

On average, the ex-factory selling price of coconut shell activated carbon is traded at RM8.50/kg. In other words, PKS converted activated carbon can yield RM8500 per tonne compared to the same amount of raw PKS sold at RM4800, based on conversion ratio of 12 to 1.

Source: National Biomass Action Plan 2023-2030

The EUDR represents a material change in position by a regulator with respect to the transparency of some of the EU’s biggest globally relevant supply chains. As the rule came into force on 29 June 2023, companies need to now consider and prepare for the new obligations which will be subject to enforcement from 30 December 2024.

Here are the Top 10 things that we need to know:

In addition to nes, other measures may be taken. is includes the con scation of products and revenue gained from these items, exclusion from the public procurement process and funding, and with repeated infringements, a ban from dealing in the EU in products covered by the regulation.

No3

EUDR applies to goods produced on or after 29 June 2023

e law applies to recent deforestation. Operators need to ensure that products entering the EU have not come from land that has been subject to deforestation or degradation since 31 December 2020.

EUDR also covers derived products; meat products, leather, chocolate, co ee, palm nuts, palm oil derivatives, glycerol, natural rubber products, soybeans, soy-bean our and oil, fuel wood, wood products, pulp and paper, printed books.

Products must be produced in accordance with local legislation. is extends EU compliance to laws and rules around land use, native title, environment, labor rights, anti-corruption and customs.

Responsibility sits with the company placing the product on the EU market

A er 30 December 2024, any company that wants to sell products in the EU that are covered by the EUDR will need to upload a due diligence statement to the competent national authority. EUDR extends to companies exporting covered products from the EU.

e Due Diligence Statement aims to clearly track the commodities supply chain by collecting data that proves compliance with regulations. It will include detailed information to verify adherence to standards. Although no countries will be speci cally banned, risk-based controls will be applied, with the European Commission classifying countries as low-, standard-, or high-risk. is classi cation is determined by the level of due diligence required. Risk assessments will be conducted for each product to evaluate the likelihood of non-compliance. Information from these assessments is accessible through government authorities, traders, and the public. Companies must share due diligence details, such as reference numbers and evidence of compliance, down the supply chain.

e regulation has gone as far as to set minimum thresholds for competent authorities who have carriage in member states for compliance and enforcement. For example, for high-risk products, a minimum of 9% of operators will be subject to compliance checks.

e EUDR requires companies or operators to establish a DD system. is needs to be reviewed at least annually and the company needs to publicly report as widely as possible the steps they have taken to establish compliance with their DD requirements.

e EUDR speci es that competent authorities are to use any technical and scienti c means adequate to determine the exact place where the relevant commodity or product was produced, including chemical and anatomical analysis. Origin or provenance has been identi ed as a critical tenant to the integrity of these supply chains –verifying origin or provenance of products will be important to ensuring compliance.

Failure by a company to comply with EUDR means that from 30 December 2024, it will be prohibited from selling covered products on the EU market.

Companies seeking to engage in the import or export of the commodities that fall in the scope of EUDR will be required to undertake thorough due diligence, either independently or through proficient external parties. The regulation outlines a set of essential steps for compliance:

Acquire geographical information, such as satellite imagery, pertaining to the specific land parcels where the commodities originated.

Evaluate the potential risks for non-compliance with the EUDR regulation.

Implement measures to reduce identified risks to minimal levels.

The EUDR entered into force on 29 June 2023, affording companies and pertinent authorities in both producing and consuming countries 18 months to prepare before the rules become enforceable as of 30 December 2024.

Starting in January 2025, business operators and traders will be mandated to conduct due diligence on products entering (or exiting) the EU market.

Upon the enforcement of the legislation, all producing countries, whether within the EU or other global regions, will initially receive a standard-risk classification. Before January 2025, the European Commission will issue a roster of countries categorized as presenting either a low or high risk in relation to commodities and products linked to deforestation.

Source: Federation of Malaysia Manufacturers (FMM)

Ministry of Plantation Industries and Commodities (KPK)

Jalan P2p, Presint 2, 62000 Putrajaya, Wilayah Persekutuan Putrajaya.

Phone : +6 03 8000 8000

Fax : +6 03 8880 3482

Email : portalmaster@kpk.gov.my www.kpk.gov.my

Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) 6, Persiaran Institusi, Bandar Baru Bangi, 43000 Kajang Selangor. Phone : +6 03 8769 4400

Email : general@mpob.gov.my www.mpob.gov.my

Malaysian Palm Oil Council (MPOC)

Level 25, PJX HM Shah Tower, No. 16A Jalan Persiaran Barat PJS 52, 46200 Petaling Jaya, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia. Phone : +6 03 7806 4097

Fax : +6 03 7806 2272

Email : wbmaster@mpoc.org.my www.mpoc.org.my

Malaysian Palm Oil Certi cation Council (MPOCC)

Level 2, Tower 2B, UOA Business Park, Unit 2-1, No 1, Jalan Pengaturcara U1/51, Seksyen U1, 40150 Shah Alam, Selangor.

Phone : +6 03 2181 0192

Email : info@mpocc.org.my www.mpocc.org.my

Malaysian Palm Oil Green Conservation Foundation (MPOGCF)

Level 12-3-3A PJX HM Shah Tower,16A, Persiaran Barat, Pjs 52, 46200 Petaling Jaya, Selangor. Phone : +6 03 7931 5544 / 5445 www.mpogcf.org

Malaysian Palm Oil Association (MPOA)

Tower 3, Level 8, Unit 03-08-09&10, UOA Business Park, No, 1, Jalan Pengaturcara U1/51, 0150 Shah Alam, Selangor. Phone: +6 03 5021 0730

Email: admin@mpoa.org.my www.mpoa.org.my

Palm Oil Millers Association of Malaysia (POMA)

27 Jalan Soo Ah Yong, Taman Canning 31400 Ipoh, Perak, Malaysia. Phone : +6 05 548 2279

Fax : +6 05 545 0380

Malayan Agricultural Producers Association (MAPA)

Unit K03-08-08, Tower 3,UOA Business Park, 1, Jalan Pengaturcara U1/51, 40150 Shah Alam, Selangor. Phone : +6 03 5031 3995

Email : mapahq@mapa.net.my www.mapa.net.my

Malaysian Oleochemical Manufacturers Group (MOMG)

Wisma FMM, No. 3 Persiaran Dagang, PJU 9, Bandar Sri Damansara, 52200

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Phone : +6 03 6286 7200

Fax: +6 03 6274 1266 / 7288

Email : secretariat@momg.org.my www.momg.org.my

Malaysian Edible Oil Manufacturers’ Association (MEOMA)

134-1 Jalan Tun Sambanthan 50470 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Phone : +6 03 2274 7420

Email : secretariat@meoma.org.my www.meoma.org.my

Malaysia Biodiesel Association (MBA) Wisma FMM, No. 3 Persiaran Dagang, PJU 9, Bandar Sri Damansara, 52200 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Tel : +6 03 6286 7200

Fax : +6 03 6277 6714

Email : secretariat@mybiodiesel.org.my www.mybiodiesel.org.my

Palm Oil Re ners Association of Malaysia (PORAM)

801C & 802A, Block B, Executive Suites Kelana Business Centre, No. 97 Jalan SS7/2, Kelana Jaya 40731 Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia.

Phone : +6 03 7492 0006

Fax : +6 03 7492 0128

Email: info@poram.org.my www.poram.org.my

e oil palm industry generates about K2.5 billion annually and remains the country’s biggest earner as far as cash crops are concerned. Oil palm became a commodity in 1960 and has been contributing to the economy in providing jobs and revenue. Ronald Soupa, the general manager of the Milne Bay Estate in Alotau, Milne Bay, recently talked to business reporter Nathan Woti about the industry and the role of the country’s only milling company, New Britain Palm Oil.

hen was the New Britain Palm Oil

Limited established in PNG? the country?

Soupa: In 1967. e New Britain Palm Oil Limited (NBPOL) focuses mainly on palm oil in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. It manages plantations and operates processing facilities which mostly handle certi ed sustainable palm material. e company produces and distributes Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)-certi ed palm oil under the identity preserved model, which means its palm oil is traceable to the plantation level. e company is also involved in research on seed production and plant breeding to optimize crop yields in oil palm growing regions.

an you explain NBPOL’s operations in

Soupa: We operate over 50 estates, 13 palm oil mills and seven kernel crushing mills. Until 2018/19, the NBPOL owned palm oil re neries in Liverpool in the United Kingdom, and West New Britain. ese are now owned and managed by our parent company’s downstream business, Sime Darby Oils. NBPOL’s focus remains entirely on upstream palm oil operations. Our sugar cane plantations comprise more than 5,600 hectares, and our cattle pastures over 9,500 hectares. We also operate a sugar re ning ethanol factory and two abattoirs to produce beef for the local markets. NBPOL’s world-class Dami Research Station and Seeds Production Unit are located in West New Britain.

hat is the current status of NBPOL?

Soupa: NBPOL manages plantations and operates processing facilities which mostly handle certi ed sustainable palm material. Basically, the supply chain position is downstream and midstream, meaning, we are grower of oil palm, processor and trader of crude palm oil and palm kernel oil. Re ning or down streaming is done by the parent company Sime Darby. In terms of land, the NBPOL owns up to 140,000 hectares of land (in PNG). However, smallholder growers also play a crucial role in the production line because they own most of the land and grow their own oil palm and sell it to NBOL mills at certain prices.

Soupa: We are proud to be the biggest employer in the country with more than 25,000 employees directly bene ting from the company. Plus, the small-holder growers and oil palm farmers who we indirectly create opportunities for. ow many people do you employ?

W W C H W W

hat is PNG’s main international market

and is PNG oil palm standards compliance?

Soupa: Because our oil palm is certi ed by international standards, we can export to any international market, including the European market. On compliance, we have come up with the world’s best practices, from palm seedling planting, to nursery, growing and harvesting, all the way to milling. So, the short answer is yes. We are certi ed members of RSPO. We have also ensured that we adhere to our commitment to the NDPE (no deforestation, no peat, and no exploitation) policy. at is why oil palm in PNG is restricted to growing in deforested land or exploited areas because there is traceability and accountability for international markets.

hat are some challenges hindering production in general?

Soupa: Every country you go to has its own challenges, and PNG is no di erent. We have our fair share of problems. I believe the biggest issue in our country at the moment is the law and order problem. If we want to prosper, attract foreign investors, and develop, we cannot keep allowing these kinds of issues to go on. For us here at Milne Bay Estate, we have experienced a drop in production due to the law and order issues we experienced in 2019 and 2020. Most of our sta members le work in fear for their lives, some were held at gunpoint and our machines, vehicles and equipment stolen. To counter the threat, we had to spend over a K1 million on security. We ew in 10 mobile squad members from Port Moresby to come and provide security. e company is looking a er them and they have been doing a fantastic job in providing security, not only for us but also for the police in Alotau to curb criminal activities. We pay for their plane tickets back and forth to visit their families every six months for the last two or three years. We also provide their accommodation, food, and allowances.

hat do you think of the government intervention programme for the oil palm industry??

Soupa: I thank the government for realizing the importance of this cash crop commodity. Oil palm has done much for our people and the country in the past decades despite being without a ministry or policy to guide it. With the creation of the new palm oil ministry, I feel like we have a voice and head now. e government’s intervention programme for seedlings and replanting is a start. We saw oil palm minister Francis Manake presenting K540,000 to the Higaturu Estate in Popondetta, Northern. He also gave about K216,000 to the Hagita Milne Bay Estate to buy seedlings. I am also happy to hear that the minister is working on tabling a national oil palm policy as a bill in Parliament to be approved. e policy, including the other two legislation are key to where this industry will be in the 20 years.

Source: e National

Malaysia has yet to establish a commercial scale manufacturing plant for PKS-converted bio-graphite and bio-graphene. Nano Malaysia Bhd is currently championing the development of the graphite and graphene industry through its Biomass Innovation Circular Economy Programme (BICEP).

Turning PKS into bio-graphite and bio-graphene is a new technology and business model and this is a capital-intensive investment. us, project developers can refer to the Green technology Financing Scheme (GTFS) IV. Alternatively, an initial public o ering (IPO) fundraising model such as Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) may be considered.

Palm Kernel Shells (PKS) are used as the raw material for producing bio-graphite and bio-graphene. e PKS are dried and crushed to remove the water and oil to get the pure biomass form.

Graphite is used for pencils, steel manufacturing and electronics such as smartphones. In application of lithium-ion batteries, graphite ranks above lithium as the key ingredient. Graphite is the key raw material in the battery anode with almost all electric vehicle (EV) battery anodes comprising 100% graphite.

Whilst, graphene has many di erent applications including lithium battery, energy storage, high frequency transistor, heat dissipation, paint, thin- lm transistor, carbon-based computer device, molecular detection, and imagery, biochemical, rubber additives, nano uids etc.

Intense commercialisation of graphite and graphene technology are taking place now, especially China which is the top export country of arti cial graphite.

Technology readiness level and access to nancing are the key success factors for bio-graphite and bio-graphene. Malaysia imported arti cial graphite valued at USD 671 million (598, 751 tonnes) in 2022 and USD 384.22 million (480,101 tonnes) in 2021, making Malaysia the largest importer in the world.

e above-mentioned trade data solidi es the fact that Malaysia has a strong market demand for arti cial graphite. In other words, there is a potential transformational new commodity business model of PKS-converted bio-graphite.

Plenty of feedstock i.e palm kernel shell (PKS) which is mainly used as green fuel at boilers or exported to Japan and sold around RM400-RM500 per tonne in 2022. Bio-graphite and bio-graphene are higher value products with a better margin to o set the higher price of the feedstock.

Graphene Market: e BICEP highlights that Lux Research UK has projected the graphene market will grow to around USD 780 million by 2028.

Graphite Market: Graphite global trade has achieved more than USD4 billion in 2022 with Malaysia as the No.1 importer in the world, representing 15.1% of world import of graphite.

ere is an emerging need for Malaysia to expedite the R&D&C&I of PKS-based bio-graphene and bio-graphite considering the huge market demand globally and domestically. It is proposed that MPOB and relevant industry partners to undertake R&D&C&I for both bio-graphite and bio-graphene. A market study on bio-graphite should be conducted in view of its immediate commercialisation potential

Source: National Biomass Action Plan 2023-2030

While palm oil remains the most e cient oil crop globally, it remains entangled in concerns regarding sustainability, biodiversity, health risks, and more. While some issues may be misconceptions, others are genuine challenges, such as the presence of process contaminants like 3-MCPDE (3-monochloropropane-1,2-diol) and GE (Glycidyl esters).

3-MCPDE and GE are contaminants that can be found in vegetable oils and food items derived from these oils. ey are by-products that may arise during the re ning process of oils. ese process contaminants could possibly have carcinogenic e ects on humans.

anks to the research conducted by various parties, the industry has identi ed the sources of precursors responsible for the formation of 3-MCPDE and GE. Chlorides, along with diacylglycerols and monoacylglycerols, which are linked to free fatty acid levels in crude palm oil (CPO), are the primary precursors for 3-MCPDE and GE, respectively.

Across di erent processing units in palm oil mills, unavoidable oil losses occur. Some millers choose to recycle these oils to improve process e ciency. While this practice is well-intentioned, it carries the risk of reintroducing poor-quality secondary oil back into CPO, potentially contaminating it with high levels of chlorine.

Additionally, some millers are apprehensive that if they do not recycle such oil, it will be disposed of as waste oil and le in e uent ponds as palm oil mill e uent oil (POME oil), thereby making it worthless and signi cantly a ecting their income. is may explain why the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) has decided to postpone the planned implementation of Licensing Conditions for 3-MCPDE and GE, originally scheduled for 1 January 2023, to 1 January 2026.

Source: Eur Ing Hong Wai Onn, Fellow of the Institution of Chemical Engineers, the Royal Society of Chemistry, and the Malaysian Institute of Management.

However, the situation has evolved since then. POME oil now holds the potential to be repurposed into higher-value products. It can serve as feedstock for the production of renewable diesel or hydrotreated vegetable oil. Presently, numerous renewable diesel producers seek POME oil that carries International Sustainability and Carbon Certi cation (ISCC) due to its favorable attributes. Certi ed POME oil is regarded as emitting zero greenhouse gasses at its collection source and quali es for double counting toward blending targets in the European Union. Depending on market dynamics, some certi ed POME oil has been sold at prices close to that of CPO.

Certainly, there are additional expenses associated with obtaining ISCC certi cation for POME oil, including audits, documentation, training, and potential infrastructure enhancements to meet certi cation criteria. However, the return on investment for such endeavors typically materializes within a few months for a standard operational oil mill. Moreover, palm oil mills equipped with facilities for empty fruit bunches (EFB) pressing and pressed palm bers (PPF) oil recovery can also market their EFB and PPF oil for similar purposes and values as POME oil. is enhances the attractiveness of ISCC investments.

With such lucrative options now available, MPOB may reconsider not only preponing the Licensing Conditions for 3-MCPDE and GE but also introducing stricter standards for CPO. e current speci cations for CPO, widely used in trade between millers and re ners, have remained unchanged for decades. erefore, this could be an opportune moment to revise the standards to include more parameters such as chloride content, while also making existing parameters such as free fatty acids level more stringent.

e national palm oil extraction rate could potentially be impacted if the recycling of secondary oil to CPO is prohibited. To tackle this issue, MPOB could contemplate requiring millers to report both CPO and secondary oil production separately, and then consider them collectively in calculating the oil extraction rate with appropriate classi cation. is approach would also enable MPOB to e ectively monitor mills to prevent any deliberate production of excessive secondary oil.

Repurposing secondary oil for high-value feedstock in renewable diesel production would o er dual bene ts by not only ensuring the quality of CPO but also generating additional revenue streams for millers. ere is also a need to revise the quality standards of Malaysian CPO and position it as a superior product that meets international standards for 3-MCPDE and GE.