MUZAFFAR ALI’s

EDITED BY Meera Ali & Sathya Saran

MUZAFFAR ALI’S

MUZAFFAR ALI’S

SANJAY JAIN

edited by

Meera Ali & Sathya Saran

Prologue: Breathing Life into Umrao Jaan

The

A Language of Weaves & Motifs

Shabana Azmi X XI XII

The Graphic Image

From Anjolie Ela Menon to Preeti Vyas

manjula padmanabhan 148

Umrao Jaan

A logo design story preeti vyas 152

The Cautious Dreamer

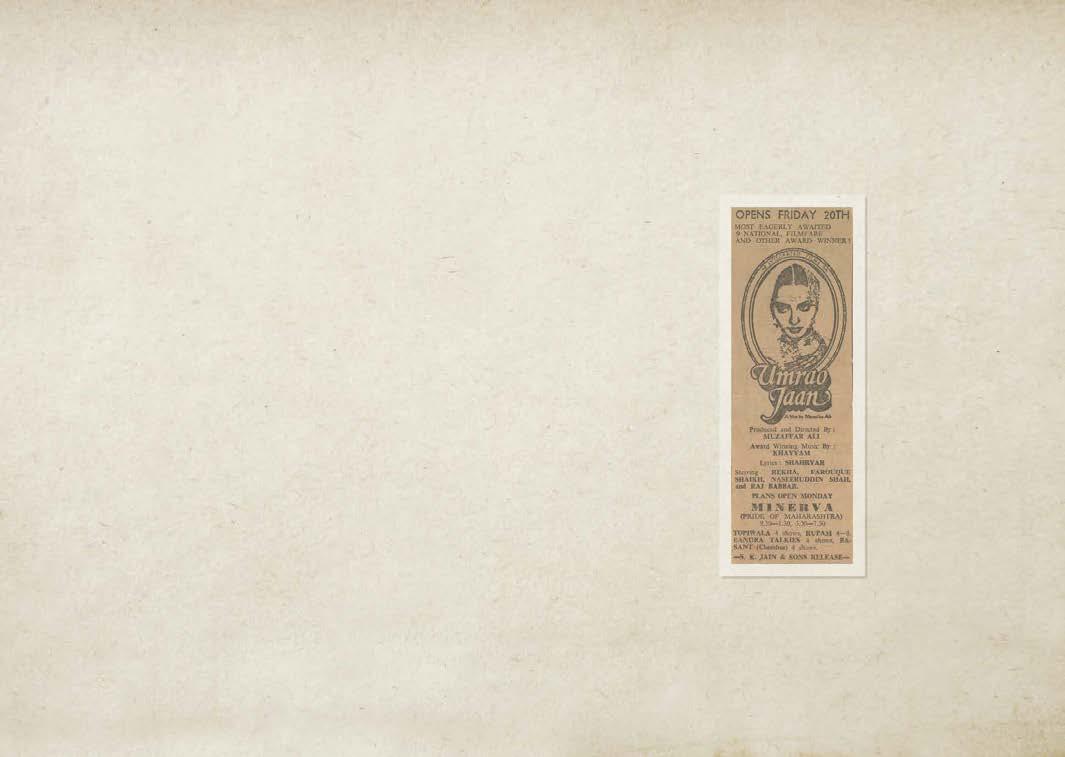

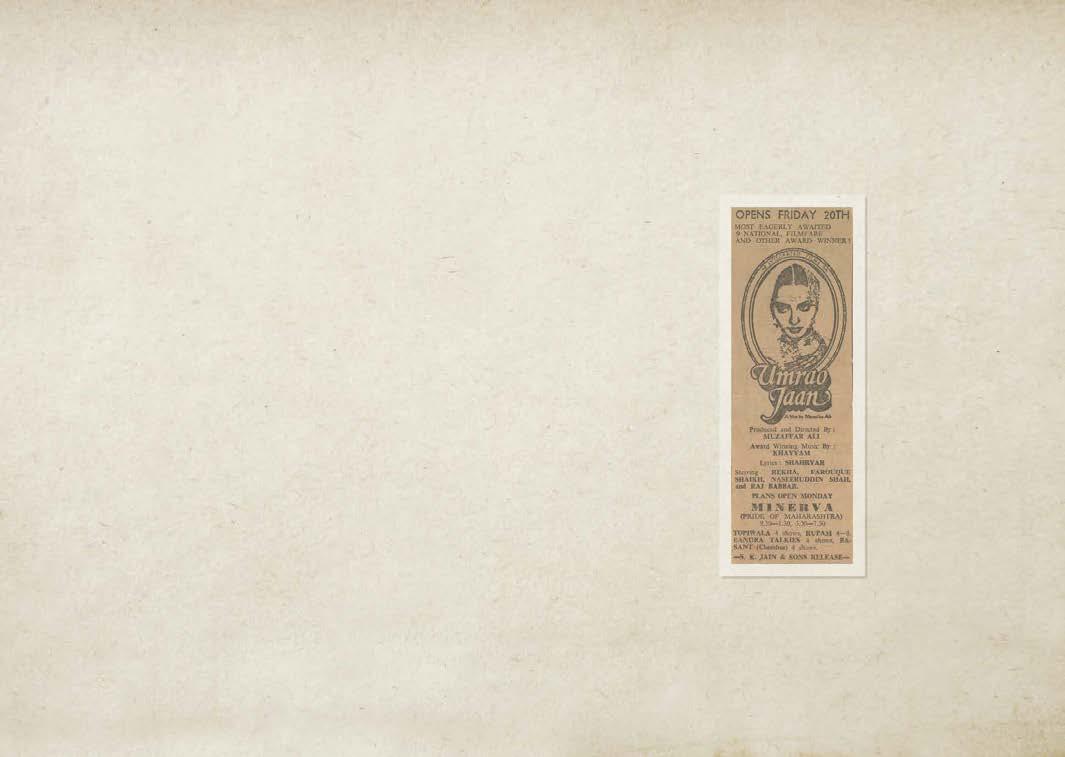

SK Jain, who blended commerce with art kaveree bamzai 156

Film Accolades

Eyes that stole a million hearts

Compiled by arpan kumar 170

Naseeruddin Shah

Raj Babbar

What Umrao Jaan Meant to Me An aching impression of the film in his life suvir saran 190

Epilogue: A Second Sunrise muzaffar ali 208

Umrao… Creator & actor in soulful trust, Silent thoughts between them, a sacred must rekha 226

What is it that draws you to a place?

A piece of culture, distilled into all its shades—walls that have held the secrets of countless dawns and dusks, of colours and hues, of words and thoughts, of ragas and rasas?

PROLOGUE: BREATHING LIFE INTO Umrao Jaan

e creator of this masterpiece leads us gently into a realm where, over 44 years ago, he sensed a presence called Umrao Jaan

by muzaffar ali

My Umrao Jaan is one that draws you to a place—a fragment of culture distilled through time, into all its subtle shades. A world where walls have witnessed the quiet unfolding of dawns and dusks, soaked in colours and silences, in whispered words and unspoken thoughts, in the lingering notes of ragas and the essence of rasas.

For me, that place was Umrao Jaan. It was more than a novel, more than a tapestry of customs and rituals. It was a mirror to how we live—with both joy and sorrow, with beauty and brutality. It was cinema not just as spectacle, but as alchemy: where people, memories and moments came to life.

I had returned to Lucknow wiser from the cities of Aligarh, Calcu a (now Kolkata) and Bombay (now Mumbai). Sensitive to society and the social predicament of people, inspired by the art of moving images. Gaman had changed me. I felt like a migrant myself, a driver behind a Fiat wheel, tossed from place to place to the profound melody of Shahryar’s ‘Seene Mein Jalan’ and Makhdoom’s ‘Aapki Yaad Aati Rahi’. Jaidev had won our hearts—and I felt something beyond even that.

But a bigger challenge was waiting in the wings—another wrenching apart. A Gaman of over a hundred years ago, Umrao Jaan Ada had found its way into the corridors of Urdu departments in India and Pakistan. I don’t know how it was taught. In fact, I would have given my right hand to sit in on those classes. One day, an astrologer met Pravin Bha and me at the Carlton hotel in Lucknow. He said I would be continuing the work my maternal uncle had begun. He also told Pravin to never leave me alone in my world. I later discovered that my uncle had done an exhaustive critique on Umrao Jaan Ada. So, Umrao Jaan was in the air—in the past, present and the future.

I realized that it is out of these corridors of imagination that Umrao poured out, rst from the pen of Mirza Hadi Ruswa, and later, into English, through Khushwant Singh’s translation. But I met her in the voice of Salma Siddiqui—a gorgeous woman from Aligarh who sounded like every character of the lm. It was the greatest high to record the novel in her voice, which brought to life Umrao Jaan and all those who came into her life.

It was cinema not just as spectacle, but as alchemy: where people, memories, and moments came to life.

AMAZING GRACE

e life & times of the tawaifs of Lucknow

by ira mukhoty

THE EVOLUTION OF UMRAO JAAN

A woman & an era reborn through time

BY RANA SAFVI

Is anjuman mein aap ko aana hai baar baar divaar-o-dar ko ghaur se pahchan lijiye

(You have to visit this assembly of stars repeatedly, Look at it intently and seal it in your memory)

With a seductive gait that whispered promises, a mysterious half-smile framed by the pain of poetry, and a delicate ick of the wrist performing adab, Umrao Jaan entered our lives 44 years ago. She didn’t simply arrive—she forged her way into our hearts, etching herself into our memory like the refrain of a haunting ghazal. Since then, she has refused to leave; her presence as persistent as the scent of a ar on old silk, as beguiling as pressed owers between the pages of forgo en poetry—reminding us that some stories are eternal.

Umrao Jaan carried with her the faint fragrance of a world silenced by history—a world dismantled by colonial cannons and moral purging following the Uprising of 1857. In her gaze shimmered the vanished grace of Lucknow’s salons, where poetry and music were devotions to the Divine. Umrao emerged—not as a ghost, but as a ame—rekindling the elegance, sorrow and de ance of a lost era.

History is always about those who live life at centre stage, and rarely about those who live on the margins of society. Women themselves have mostly been sidelined in cinema, and rarely have lms been dedicated to their aspirations, dreams, and struggles. Even lms made about tawaifs or courtesans have reduced them to objects of desire or tragic victims. ese women were once integral to pre-colonial economic and cultural life. ey lived lives of luxury, and were repositories of art and culture. Yet, over time, they have been cut o from their roots in syncretic culture and literature, and relegated to the margins.

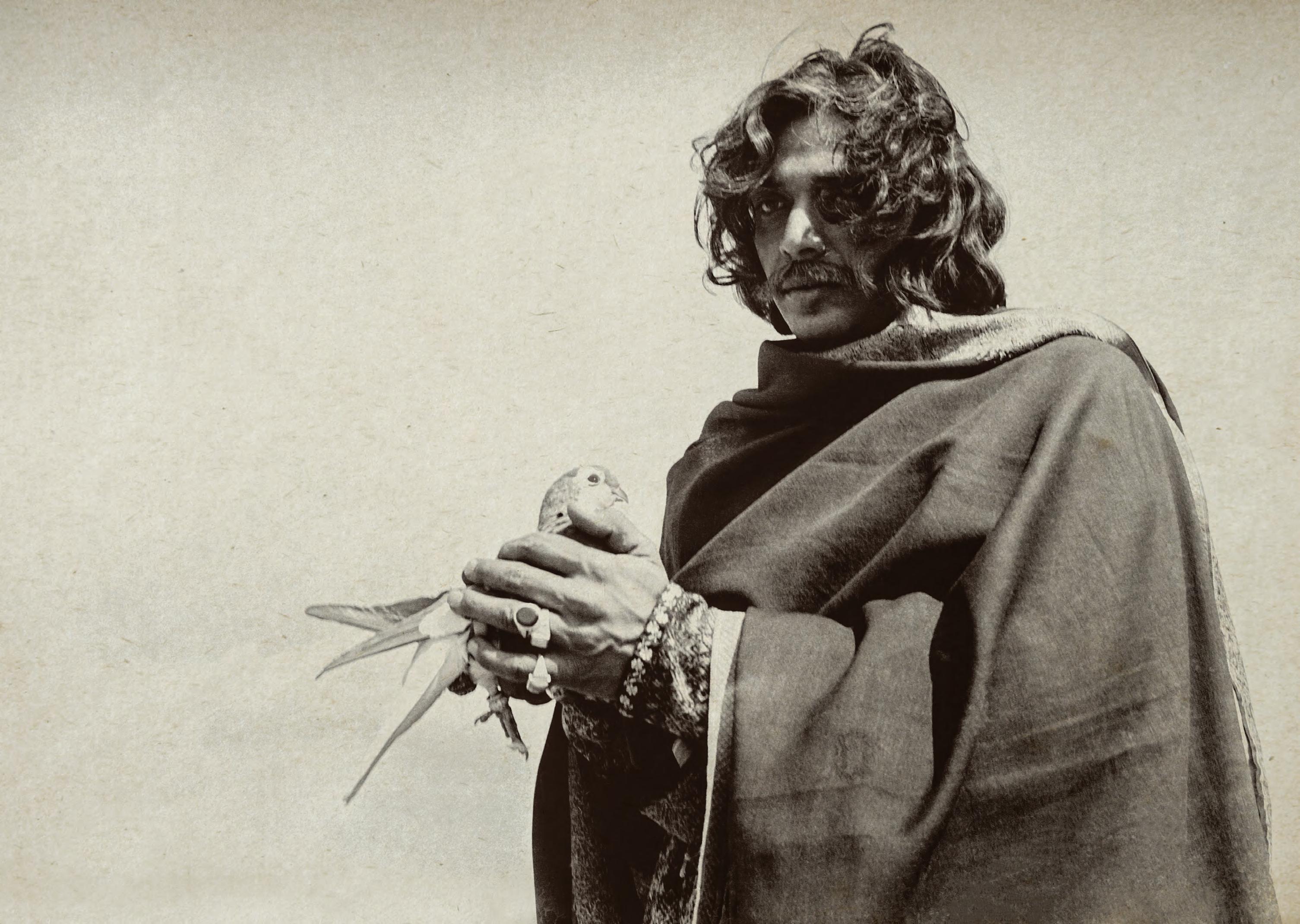

e Awadh aristocracy, and indeed Nawab Wajid Ali Shah himself, were seen as e ete, decadent symbols, engaged in chess playing, kite ying, pigeon ying. is high Persian literary culture, steeped in syncretic traditions of music, dance, poetry, was—as we know—deliberately misunderstood by the British, who used it to usurp the kingdom of Awadh and exile Nawab Wajid Ali Shah to Calcu a in 1856.

en came the Uprising of 1857, which was quelled by the British who rmly established their rule over India as an imperial power. It wasn’t only the Mughal dynasty or Nawabs of Awadh who were destroyed, but an entire era. A culture was destroyed.

e arbab-e-nishat or Kathak dancers and classical singers were now the “nautch girls” (from the word naach or dance).

THE VISUAL POETRY

Capturing emotion, aming art

by alka pande

e Emotional Landscape of Architecture

Filmed on location in Lucknow and Faizabad, and Kotwara, Umrao Jaan’s architecture plays an active role in visual storytelling. Courtyards, arched corridors, mirrored halls, and carved wooden screens aren’t just backgrounds; they symbolize Umrao’s shi ing states of mind. e architectural elements, such as high ceilings, la iced screens, and sprawling courtyards, become symbolic landscapes of Umrao’s inner world. Her emotions are mirrored in the spaces she inhabits: grand but empty, ornate but restrained. e repeated use of mirrored surfaces, corridors and partitions suggests a fragmented sense of identity, a woman admired, objecti ed and misunderstood. e grand but decaying Nawabi mansions mirror her life—beautiful, ornate, yet marked by sorrow and impermanence.

Also, the use of depth with Umrao o en amed within doors, arches, or windows reinforces the motif of separation and enclosure, central to her experience as a courtesan.

e use of depth—with Umrao o en framed within doors, arches, or windows—further reinforces the motif of separation and enclosure, central to her experience as a courtesan.

e Shared Aesthetics of Muza ar, Bha and Khayyam

For me, the soul of the lm had to be captured delicately on celluloid, and Pravin instinctively understood my language—how I felt about the texture of the textile, about the so , trembling language of candlelight… both in the intimate corners and across collective chandeliers.

—Muza ar Ali

e lm’s cinematography works hand-in-hand with Khayyam’s soul-stirring music and Shahryar’s poetry. Musical sequences are shot with reverence, with long takes, slow zooms, and minimal cuts, allowing Rekha’s nuanced expressions and gestures to take centre stage. With each mujra, the camera doesn’t intrude—it just observes, quietly respecting the sanctity of the performance. e result is deeply immersive, allowing viewers to feel the pathos behind the beauty. e visual rhythm matches the music’s cadence, making the mise-en-scène an extension of the ghazal itself.

Clothes for the men were a complicated a air because there were so many nawabs and nawab-like men in the lm.

It was important to choose colours to suit the mood of the scenes, and I was very pleased with the choice of green peshwaz and deep maroon dupa a that I made for Rekha to wear in the tragic moment when she is dancing in front of her childhood home.

Fortunately for us, the nancier could not say no to Rekha when she insisted on taking us to the Indian Textiles store at the Taj hotel for Banarasi fabric. We bought the beautiful brocades for several of her ghararas—including the stunning black and gold one—from there. Perhaps, black was a colour not worn by a courtesan of that time, but it was too beautiful not to be used.

I must mention here that Shaukat Aapa (Azmi) was a great source of encouragement for me. She had a keen eye for textiles and clothes. It was a pleasure making clothes for her—some of them extremely gorgeous—because she not only carried them well but was so appreciative and generous with her praise.

In the ‘In Aankhon Ki Masti’ scene, she has a beautiful dupa a with patapati got on it. at was loaned by Kulsum.

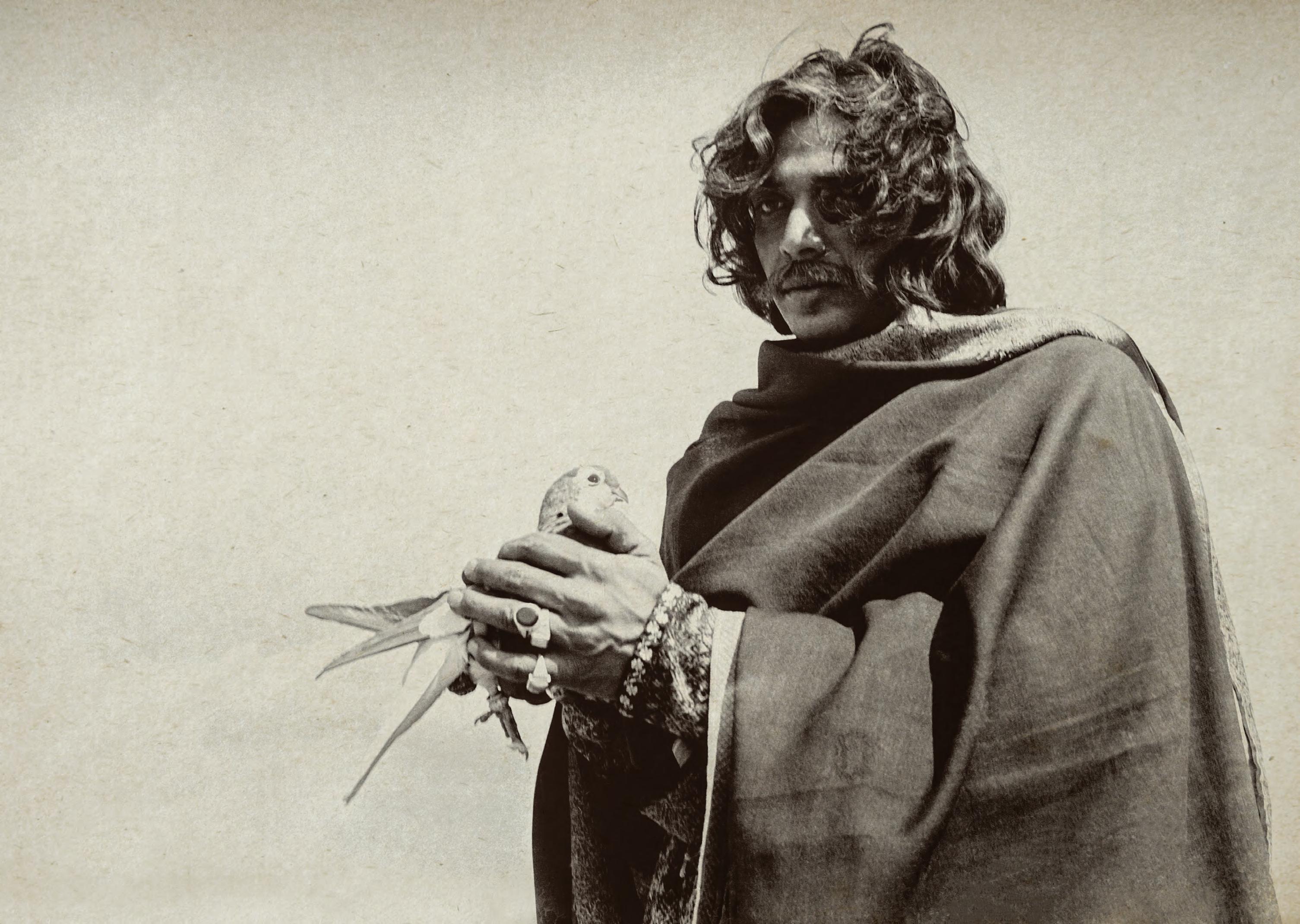

Clothes for the men were a complicated a air because there were so many nawabs and nawab-like men in the lm. Even if they appeared only for a few minutes, they had to be dressed appropriately. e men all wore loose pyjamas of co on, silk or brocade. Over these, they wore thin kurtas and, on top of those, achkans, sherwanis, and chapkans—di erent kinds of long coats, some closed and some open. And, of course, they all wore caps. In several scenes, they draped marvellous jamawar shawls across their shoulders. Many of these were lent to us by members of various aristocratic families, some of whom also sat as part of the audience for the mujras or dance sequences. For the two most important mujra scenes in the lm, over a dozen richly dressed real nawabs formed the audience.

Taqi Hasan of Salempur also loaned us several of his fabulous shawls, one of which he himself wore in a scene. When the nawabs were asked to come again the next day to continue shooting the same scene, many of them brought di erent shawls from their collections. ey were very disappointed to learn that ‘continuity’ in lmmaking dictates that everything—including every piece of clothing—must remain exactly the same for the length of a scene, even if its parts are shot months apart. In fact, there is even a special Assistant Director who looks a er continuity.

I remember Naseeruddin Shah complaining to me that he had to wear uninteresting clothes, sometimes more than once.

We were very lucky that we had a very senior wardrobe-in-charge, whom we called Chacha, who had worked on many classic period lms made decades earlier. He and his assistant Badshah kept the clothes for each scene together. ey were also experts at tying the safas needed for several male actors. I could not have managed without them. In addition, they also looked a er the women’s costumes—not to mention their expert skills at darning and ironing di erent kinds of fabric appropriately. ey were terri c!

I remember Naseeruddin Shah complaining to me that he had to wear uninteresting clothes, sometimes more than once. He also had to make do with a very unimpressive wig. As a consolation, I did make one or two very fancy sets of clothes for him, which he wore with his very impressive new wig.

It’s very gratifying that the costumes of Umrao Jaan are still talked about a er all this time. Watching the lm a er so many years, I remember all the people—many of whom are no longer with us—who contributed to the making of these clothes. I hope I have not forgo en anyone.

In aankhon ki masti ke mastaane hazaaron hain

In aankhon se vaabasta afsaane hazaaron hain

Ik tum hi nahin tanhaa, ulfat mein meri ruswaa

Is sheher mein tum jaise deewaane hazaaron hain

Ik sirf hamin mai ko, aankhon se pilaate hain Kahne ko to duniya mein maikhaane hazaaraon hain

Is shamm-e-farozaan ko, aandhi se daraate ho Is shamm-e-farozaan ke parvaane hazaaron hain

THE MUSICAL Mise-en-Scène

of memories, desire, longing & loss

BY ANIL ZANKAR

ere are nine songs in the lm, all uniquely positioned, composed and rendered. Khayyam asked Asha Bhosle—who would sing for Umrao Jaan onscreen—to lower her pitch and sing a note and a half lower than was natural for her, to match Rekha’s husky voice. Khayyam composed the songs (ghazals) in a lower scale and slower tempo, for they would be performed di erently in the lm than the traditional mujras of the kothas. e kotha/tawaif songs of Pakeezah (1972) composed by Ghulam Mohammed were rmly embedded in public memory. ey were high-pitched, fast songs with strong beats, suitable for vigorous dance performances. Khayyam wanted the songs of Umrao Jaan to be free of Pakeezah’s shadow, and he succeeded in creating songs that were distinctly di erent from those composed by Ghulam Mohammed for Pakeezah.

e Contribution of Shahryar, the Poet Shahryar is the nom de plume of Akhlaq Mohammed Khan. A faculty member of the Urdu department of Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), he became one of the leading lights of Urdu poetry and went on to receive the Bharatiya Jnanpith Award, India’s highest literary honour. Shahryar’s work is a remarkable con uence of modernist sensibilities expressed in traditional form. For example,

Phir kahin khwaab-o haqiqat ka tasadum hoga

Phir koi manzil-e benaam bulati hai hamein

(Once again, a con ict between dreams and reality will rage somewhere

Once again, some nameless destination calls out to me)

His biographer Rakshanda Jalil notes:

Poetry, Shahryar believed, must necessarily have an element of music. Without music there can be no poetry and like music, poetry too must follow some rules and principles. […] Shahryar held tradition in great regard. He believed that tradition could teach the nuts and bolts of poetry and especially the ghazal, for the tools of Urdu poetry have remained largely unchanged while the outer appearance has changed as has its vocabulary.

Muza ar Ali and Shahryar’s friendship since their college days led to their professional collaboration. Ali says in memoriam. “He was one of the greatest modern poets. He was my inspiration. I used his poetry in all my lms... He was an extremely well-mannered person, particularly sensitive to social issues. As for his work, his maximum contribution was in Umrao Jaan. e songs were immortal. He understood the soul of my movies.”

It was the early 1980s. I was an illustrator and cartoonist, struggling to make a living while staying as a paying guest in South Bombay.

I had become close friends with the artist Anjolie Ela Menon, famous for her paintings of graceful, pensive nudes and expressive portraits. We o en met in my room in Nagin Mahal, a pleasant, airy apartment above Kamling Restaurant in Churchgate, where I lived as a paying guest.

She knew that I was always desperate for work!

So, when she got a call from Muza ar Ali, the equally famous lm director, artist and poet, asking if she’d be interested in designing a poster for his next lm, she thought of me.

I knew that I would not be designing the poster—my task would be to complete the design elements around the main image that she would create. at was ne by me. I loved and admired Anjolie’s work and was happy to help her complete the poster design.

It’s important to explain here that I had grown up outside India, with very li le contact with Hindi speakers and no knowledge at all of Hindi cinema. Even during the three years when we lived in Delhi in the early 1960s, my family and I hardly ever saw any Hindi movies. e only one I can remember is the horror movie Bees Saal Baad. Since I was a child when I saw it, the e ect it had was to scare me o from Hindi lms for many years to come! I can still remember the screechy-eerie theme song of a soul in anguish.

For me, therefore, Umrao Jaan was exotic in every sense. Anjolie and I watched it in a preview theatre, along with the director. e sound of the language was similar to Hindi but so er, more elegant, more musical and poetic. I understood the mood even without really knowing what was being said. e se ings and costumes were opulent in the way of a fairytale drama set in the distant past. e music was re ned, rather than “ lmi”. More than anything else, however, it was the theme of courtesan-as-heroine and the treatment of the subject that made the movie unusual.

I was, of course, aware of an earlier world in which it was very common for monarchs, lords and other wealthy men to maintain extramarital arrangements of various kinds. Plus, I had lived with my parents in ailand for three years, during the Vietnam War, when young American soldiers were ooding into Bangkok for “rest and recreation”. e pleasure-industry was thriving and the e ects of it were visible everywhere.

Perhaps, on account of this early exposure, I was very conscious of the sex trade and the complex ways in which di erent cultures manage to both incorporate and condemn it. Concubines, odalisques, geishas and courtesans were not prostitutes. Yet, at the same time, they were all women living outside the context of conventional, domestic sexuality.

I knew that the movie we were about to see was about a “legendary” courtesan. I assumed that there would not be any steamy scenes, because it was well known that

the Indian Censor Board was hyperactive in this regard. What I didn’t expect was that the lm would be so respectful of the central character that she would transcend her situation altogether. She becomes almost supernaturally pure. It’s as if, by the force of her character and her talent as a poet and dancer, she transforms the very earthly role that Fate has chosen for her into a platform on which she can sparkle as a type of living goddess.

Rekha looks fabulous. ere’s an enamelled quality to her face, her clothes and her gaze, as if she’s looking at us from the other side of history. As if she knows that her kind of woman will never again come into existence. While her body is trapped like a gemstone in a cage of gold, her spirit breaks free. It is a mesmerizing performance. I knew the actress’s face from hoardings around the city, but, in this movie, she becomes something else altogether. Not just a two-dimensional character in a tawdry story about a young girl snatched from her family and sold to a kotha, but an emblem of a gli ering, vanished culture in which romantic love could also be re ned and digni ed.

Needless to say, it was Muza ar Ali’s poetic vision into which Rekha breathed life. He gave her the lines and the direction, while she invested the role with a genuineness that was very poignant to witness.

e director had given Anjolie a handful of lm stills, to work from. She very quickly found the pose that she wanted to use. She brie y considered making a painting from the stills, before coming up with a much be er solution.

She cut out the gure of Umrao Jaan seated on a carpet with her ivory-white costume swirling around her. en, with that image as the focus, Anjolie made a painting on a small hardboard panel—about 24 x 18 inches in size. e panel had deep umber at the lower edge, and smoky sepia in the background. In the distance, white domed buildings faded into the twilight, with a pale moon rising in the sky over Umrao Jaan’s right shoulder. It was perfect.

My contribution was to place the titles! at’s it! e title-face was based on a famous font called Le Gri e, and I added the dimensional-shadow around it, to give it extra weight. en, I had bromide prints made of the title and placed them on a tracing-paper overlay covering the panel that Anjolie had designed. I placed all the other text-ma er onto the same overlay.

In the days before Photoshop, that was the way artworks came together—with bits of paper held in place with a smelly glue called rubber solution. All illustrators and commercial artists used it in those days because it enabled re-positioning. It also didn’t cause the paper to warp the way water-based glue did. I used a ruler and set-square to get the many li le bits properly aligned.

Anjolie made a couple of other designs, but this was the one that was most prominently used. Strangely enough, it’s almost impossible to nd online now!

THE CAUTIOUS DREAMER

SK Jain, who blended commerce with art by kaveree bamzai

Discovering this epic tale of love, betrayal and human resilience in the face of extreme odds, societal norms and restrictions proved to be a revelation, and my interest in Urdu literature took a quantum leap.

“My mother’s portrayal of Khanum in Umrao Jaan is the one performance she is most remembered by. She inhabited Khanum’s world as to the manor born!

Muza ar is a renaissance man and held a special position in her heart. His deep sensitivity to aesthetics, his tehzeeb, his passionate vision made him an easy collaborator for the detailed character study that the trained actress in her was used to.”

shabana azmi

Zindagi jab bhi teri bazm mein laati hai hamein

Ye zamin chaand se behtar nazar aati hai hamein

Surkh phulon se mahak uthati hain dil ki raahein

Din dhale yun teri aawaz bulaati hai hamein

Yaad teri kabhi dastak kabhi saragoshi se Raat ke pichhle pahar roz jagaati hai hamein

Har mulaqat ka anjaam judaai kyun hai

Ab to har waqt yahi baat sataati hai hamein

UMRAO...

Creator & actor in soulful trust, Silent thoughts between them, a sacred must

by rekha

Umrao, an experience vast, a journey untold, A woman led by fate’s rm hold.

On life’s chessboard, a challenging play, She chose her path, come what may.

Stepping o the board with fearless might, Holding fate’s horns, ready to ght.

Traversing boldly, like mountains’ height, With storms’ erce fury and earth’s gentle light.

rough hate’s sharp sting and love’s strong embrace, Umrao sought herself, her soul’s true place.

To depths profound, where beginnings lie, A timeless quest beneath the sky.

In silent whispers of gratitude so deep, Words fell short, yet emotions did seep. e scent of mogra awoke the weary soul, Navigating life’s challenges, making her whole.

Like glistening costumes rustling with dreams, Umrao’s desires in a world of gentle streams. Creator and actor in soulful trust, Silent thoughts between them, a sacred must.

e woman in silks, alive and intense, Gestures in symmetry, a dance immense. Authenticity, a privilege to share, Ful lling visions with utmost care.

e lm was kissed by a delicate golden hue, Where shades and shadows so ly entwine, Light’s playful dance gave life anew, Transforming moments into scenes divine.

e magic of Umrao Jaan in melodies ows, A tapestry of soul’s delicate pose.

Soulful music lingers, never to fade, Timeless tunes in hearts have strayed. Rendered by the goddess herself, In her haunting voice.

With sad whispers that touch the core, Of undying tales of longing and more. A symphony eternal, pure and serene, Li ing the lm to a dreamlike sheen.

contributors’ biographies

Muza ar Ali is an acclaimed Indian lmmaker, painter, designer and cra revivalist best known for his classic and much awarded lms such as Gaman (1978) and Umrao Jaan (1981). He is dedicated to the idea of creating rural employment in his ancestral village of Kotwara in U ar Pradesh. He upholds Su traditions of poetry and music, having founded the Rumi Foundation, with its agship program ‘Jahan e Khusrau: World Su Music Festival’ promoting global harmony. Ali has recently penned his autobiography Zikr: In the Light and Shade of Time, outlining his life’s inspirational and creative journey.

Meera Ali is a multifaceted entrepreneur, architect, fashion designer and cultural curator, passionate about design, heritage, and storytelling. Her work spans fashion, lm and publishing, blending creativity with intellect. Renowned for curating global festivals, she champions Indian art, architecture and cra s through innovative, collaborative platforms that celebrate tradition in contemporary ways.

Subhashini Ali, née Sahgal, was born to renowned freedom ghters Prem and Lakshmi Sahgal (INA). Educated in Kanpur, Dehradun, Chennai and the US, she joined the Communist Party of India (Marxist) in 1970. She married Muza ar Ali in 1974 and lived in Mumbai till 1984, when she went back to Kanpur. She was the CPI(M) Member of Parliament from Kanpur between 1989 and 1991. Since 1970, she has been an activist in the trade union and women’s movements.

Berenice Ellena is a costume and dress designer and has worked as curator in France and India. Initially researching on Indian traditional textiles, Ellena authored various books and articles and now lives in Paris. Designing kalamkaris for French museums and for Devi Arts Foundation, she realized an art lm on the subject.

Arpan Kumar is a writer in Hindi, known for his work in poetry, fiction, and literary criticism. His acclaimed novel (Pachchees Varg Gaz) sensitively portrays urban poverty. With ve poetry anthologies and two critical volumes, he is a powerful voice in contemporary Hindi literature.

Ira Mukhoty is a best-selling writer of narrative history. She is the author of Akbar: e Great Mughal; Song of Draupadi: A Novel; Daughters of the Sun and Heroines. Her latest book e Lion and the Lily examines the rise and fall of Awadh in the context of the global Franco-British wars.

Manjula Padmanabhan is an author, playwright, illustrator and artist. She lives in the US, with a part-time home in New Delhi.

Alka Pande is an art historian, independent curator and author. Her area of specialization is gender and sexuality through the lens of traditional Indian art and cultural practice.

Rana Saf vi is a historian, writer, scholar, and translator, passionately dedicated to preserving India’s syncretic Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb through her writings, podcasts and videos. She has authored several books, including the Delhi trilogy—Where Stones Speak: Historical Walks rough Mehrauli, e First City of Delhi; e Forgo en Cities of Delhi; Shahjahanabad: e Living City of Old Delhi, runs a popular blog and is founder of the #Shair forum on Twi er to promote Urdu poetry.

Kaveree Bamzai is an author and a journalist. She was editor of India Today and has worked with e Times of India and e Indian Express

Sathya Saran edited Femina for 12 years, making it India’s best-loved women’s magazine. She is the author of the critically acclaimed biographies on Guru Du , SD Burman, Jagjit Singh and Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia, besides a book of short stories. Her latest books include Caged, a translation of Gulzar’s poems and a translation of Gulzar Sa’ab, Yatindra Mishra’s critical biography. Her next book is an analysis of Shailendra’s work.

Suvir Saran is Culinary Director of One 8 Commune, Neuma, and Jolene. Author of Instamatic; Indian Home Cooking and Masala Farm, he writes columns for e Indian Express and Open Magazine. He sings, reads, scribbles, and stirs trouble—living between Bombay, New Delhi, and a heart forever stuck in New York City.

Preeti Vyas is an artist, designer and entrepreneur and the Founder and Chairwoman of VGC, one of India’s leading independent design and brand consultancies. A pioneer in strategic design thinking, she serves on multiple corporate boards and has shaped brand narratives for top Indian businesses for nearly three decades. She is also a published and awarded industry voice.

Anil Zankar is a writer, director, lm teacher and lm historian. He has won two National Awards and the Sudhir Nandgaonkar Memorial Award for his writings. He is an alumnus of Film And Television Institute of India, Pune.

integrated films u mrao jaa n film credits

Producer & Director

Muza ar Ali

World Rights Controller

SK Jain

Cast

Rekha

Farooque Shaikh

Naseeruddin Shah

Raj Babbar

Prema Narayan

Shaukat Kai

Dina Pathak

Gajanan Jagirdar

Akbar Rashid

Rita Rani Kaul

Satish Shah

Athar Nawaaz

Music

Khayyam

Lyrics

Shahryar

Camera

Pravin Bha

Costumes

Subhashini Ali

Screenplay

Shama Zaidi

Javed Siddiqui

Muza ar Ali

Editor

B Prasad

Playback singers

Asha Bhonsle

Jagjit Kaur

Ustad Ghulam Mustafa Khan

Talat Aziz

First published in India in 2025 by Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd in association with SK Jain & Sons and Kotwara Studios Pvt Ltd

Text © Authors / Kotwara Studios Pvt Ltd

Images © Kamat Foto Flash, SK Jain & Sons, Kotwara Studios Pvt Ltd, Anil Relia collection and Gyan Museum Gem Plaza

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The moral rights of Muzaffar Ali, Rekha, Subhashini Ali, Shabana Azmi, Raj Babbar, Kaveree Bamzai, Berenice Ellena, Arpan Kumar, Ira Mukhoty, Manjula Padmanabhan, Alka Pande, Rana Safvi, Sathya Saran, Suvir Saran, Naseeruddin Shah, Preeti Vyas and Anil Zankar as the authors of this work are asserted.

ISBN: 978-93-94501-78-2

Editors: Meera Ali & Sathya Saran

Copyediting: Marilyn Gore / Mapin Editorial

Proofreading: Ashwati Franklin / Mapin Editorial

Editorial Management: Neha Manke / Mapin Editorial

Design: Neha Ahuja

Calligraphy: Mohd Zubair

Cover illustration: Gopal Limbad and Sunil Parekh, based on the illustration by Sm.bakhshandeh

Production: Gopal Limbad / Mapin Design Studio

Printed at Thomson Press, New Delhi

CINEMA

M U Z A F F A R A L I ’ s UMRAO JAAN

Edited by Meera Ali & Sathya Saran

240 pages, 130 photographs

9.5 x 13.42” (241 x 341 mm), hc-plc, GILT EDGE

ISBN: 978-93-94501-78-2

₹10000 | $150

2025 • World rights