Handmade in India Crafts of India

Editors: Aditi Ranjan |

Editors: Aditi Ranjan |

The Indian way of life is replete with products made with the help of simple, indigenous tools by craftspeople who belong within a strong fabric of tradition, aesthetic and artistry. The range of Indian handicrafts is as diverse as the country’s cultural diversity.

The Indian way of life is replete with products made with the help of simple, indigenous tools by craftspeople who belong within a strong fabric of tradition, aesthetic and artistry. The range of Indian handicrafts is as diverse as the country’s cultural diversity.

The Indian way of life is replete with products made with the help of simple, indigenous tools by craftspeople who belong within a strong fabric of tradition, aesthetic and artistry. The range of Indian handicrafts is as diverse as the country’s cultural diversity.

A source book of handicrafts, Handmade in India is a unique compendium of Indian crafts. It is a resource of the craft repertoire that reflects the diversity of the country, its cultural milieu and the relationships that nurture creativity and ingenuity. This encyclopaedic publication maps the crafts of the country, and captures the traditions that have enriched the day-to-day lives of Indian people while being a source of livelihood for generations of craftspeople. Handmade in India probes into all aspects of handicrafts—historical, social and cultural influences on crafts, design and craft processes, traditional and new markets, products and tools—unravelling a wealth of knowledge.

A source book of handicrafts, Handmade in India is a unique compendium of Indian crafts. It is a resource of the craft repertoire that reflects the diversity of the country, its cultural milieu and the relationships that nurture creativity and ingenuity. This encyclopaedic publication maps the crafts of the country, and captures the traditions that have enriched the day-to-day lives of Indian people while being a source of livelihood for generations of craftspeople. Handmade in India probes into all aspects of handicrafts—historical, social and cultural influences on crafts, design and craft processes, traditional and new markets, products and tools—unravelling a wealth of knowledge.

A source book of handicrafts, Handmade in India is a unique compendium of Indian crafts. It is a resource of the craft repertoire that reflects the diversity of the country, its cultural milieu and the relationships that nurture creativity and ingenuity. This encyclopaedic publication maps the crafts of the country, and captures the traditions that have enriched the day-to-day lives of Indian people while being a source of livelihood for generations of craftspeople. Handmade in India probes into all aspects of handicrafts—historical, social and cultural influences on crafts, design and craft processes, traditional and new markets, products and tools—unravelling a wealth of knowledge.

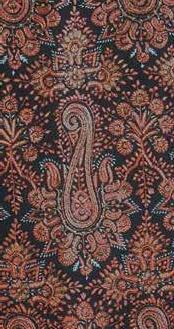

Handmade in India is based on extensive field work and research, and maps out the regional craft clusters identified across the country on the basis of prevailing craft-work patterns. It is closely woven with images to reveal the array of crafts in India. Some of these are renowned, like the pinjrakari and khatumband wood work of Kashmir, blue pottery of Jaipur, chikankari embroidery of Lucknow, the kannadi or metal mirrors from Aranmula, chappals or footwear from Kolhapur, and the bamboo craft of Assam. Other, lesser known, crafts like the paabu or stitched boots from Ladakh, jadupatua paintings from Jharkhand, the making of Kathakali and Theyyam headgear, khadi or tinsel printing in Ahmedabad have also been described in striking detail. The close study of various crafts makes it possible to discern subtle, sometimes unusual, differences in the same craft practiced by distinct regions or communities—like tie-resistdyeing which is called bandhani in Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, and bandhej in Rajasthan.

The first of its kind ever attempted, this publication with stunning photographs will be a tremendous resource for product and textile designers, artists, architects, interior designers, collectors, development professionals and connoisseurs alike. It will be of immense value for facilitating worldwide participation in the planning and development of the handicraft sector in India. It will also be a useful reference for libraries interested in Indian crafts and culture, and organizations and agencies that work for and with the crafts sector in India.

Handmade in India is based on extensive field work and research, and maps out the regional craft clusters identified across the country on the basis of prevailing craft-work patterns. It is closely woven with images to reveal the array of crafts in India. Some of these are renowned, like the pinjrakari and khatumband wood work of Kashmir, blue pottery of Jaipur, chikankari embroidery of Lucknow, the kannadi or metal mirrors from Aranmula, chappals or footwear from Kolhapur, and the bamboo craft of Assam. Other, lesser known, crafts like the paabu or stitched boots from Ladakh, jadupatua paintings from Jharkhand, the making of Kathakali and Theyyam headgear, khadi or tinsel printing in Ahmedabad have also been described in striking detail. The close study of various crafts makes it possible to discern subtle, sometimes unusual, differences in the same craft practiced by distinct regions or communities—like tie-resistdyeing which is called bandhani in Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, and bandhej in Rajasthan. The first of its kind ever attempted, this publication with stunning photographs will be a tremendous resource for product and textile designers, artists, architects, interior designers, collectors, development professionals and connoisseurs alike. It will be of immense value for facilitating worldwide participation in the planning and development of the handicraft sector in India. It will also be a useful reference for libraries interested in Indian crafts and culture, and organizations and agencies that work for and with the crafts sector in India.

Handmade in India is based on extensive field work and research, and maps out the regional craft clusters identified across the country on the basis of prevailing craft-work patterns. It is closely woven with images to reveal the array of crafts in India. Some of these are renowned, like the pinjrakari and khatumband wood work of Kashmir, blue pottery of Jaipur, chikankari embroidery of Lucknow, the kannadi or metal mirrors from Aranmula, chappals or footwear from Kolhapur, and the bamboo craft of Assam. Other, lesser known, crafts like the paabu or stitched boots from Ladakh, jadupatua paintings from Jharkhand, the making of Kathakali and Theyyam headgear, khadi or tinsel printing in Ahmedabad have also been described in striking detail. The close study of various crafts makes it possible to discern subtle, sometimes unusual, differences in the same craft practiced by distinct regions or communities—like tie-resistdyeing which is called bandhani in Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, and bandhej in Rajasthan. The first of its kind ever attempted, this publication with stunning photographs will be a tremendous resource for product and textile designers, artists, architects, interior designers, collectors, development professionals and connoisseurs alike. It will be of immense value for facilitating worldwide participation in the planning and development of the handicraft sector in India. It will also be a useful reference for libraries interested in Indian crafts and culture, and organizations and agencies that work for and with the crafts sector in India.

With over 3500 colour photographs and 140 maps

With over 3500 colour photographs and 140 maps

With over 3500 colour photographs and 140 maps

EDITORS

Aditi Ranjan, M P Ranjan

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF DESIGN (NID), AHMEDABAD

Published by Council of Handicraft Development Corporations (COHANDS), New Delhi

Office of the Development Commissioner Handicrafts, Ministry of Textiles

MAPIN PUBLISHING

Reprinted in 2024

First published in India in 2007 by: Council of Handicraft Development Corporations (COHANDS), New Delhi

Printed and produced by: Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd

706 Kaivanna, Panchvati, Ellisbridge, Ahmedabad-380006 India

T | 91-79-4022 8228

E | mapin@mapinpub.com www.mapinpub com

Conceived, researched, edited and designed by:

National Institute of Design (NID), Ahmedabad

Text, photographs and graphics © 2007 National Institute of Design (NID), Ahmedabad, and Development Commissioner (Handicrafts), New Delhi

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the Council of Handicraft Development Corporations (COHANDS), New Delhi.

Project funded by

Office of the Development Commissioner Handicrafts, Ministry of Textiles, Government of India

ISBN: 978-81-88204-57-1

LCCN: 2005929526

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

Editors: Aditi Ranjan, M P Ranjan

Designers: Zenobia Zamindar, Girish Arora

Printed in Malaysia

Cover photo by Ramu Aravindan.

An artisan finishing diyas, terracotta lamps, made for rural and urban markets for festivals, in Nawrangpur district, Orissa.

Back cover photo by Deepak J Mathew.

Carved and painted wooden toys of Kondapalli, depicting various craft processes, occupations and household activities. The toys resemble the 19th century Company paintings of vocations and craftspersons at work in India.

Front flap photo by Sandeep Sangaru. Kashmiri craftsman refining a high value walnut wood carving in Srinagar.

Back flap photo by Purvi Mehta.

Detail of a dowry bag appliquéd and embroidered by a Rabari woman in Kachchh, Gujarat.

Page 1: photo by Jogi Panghaal.

Detail of a contemporary cotton kantha, quilted and embroidered textile made by craftspersons in West Bengal.

Pages 2 & 3: photo by Farah Deba.

Detail of the carved and painted wood work inside a prayer hall in Thiksey Monastery, Ladakh.

Statutory notes on Map of India on page 006:

The external boundaries and coastlines of India agree with the Record/Master Copy certified by Survey of India

© Government of India, Copyright 2024.

The responsibility for the correctness of internal details rests with the publisher.

The territorial waters of India extend into the sea to a distance of twelve nautical miles measured from the appropriate base line.

The administrative headquarters of Chandigarh, Haryana and Punjab are at Chandigarh.

The interstate boundaries between Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Meghalaya shown on this map are as interpreted from the North-Eastern Areas (reorganisation) Act 1971, but have to be verified.

Administrative boundaries of J&K (Union Territory) and Ladakh (Union Territory) shown here are yet to be authenticated by concerned state authorities.

Newly formed districts of Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Mizoram, Meghalaya, Rajasthan, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu are yet to be authenticated by concerned state authorities.

006 Map of India

007 List of Crafts

010 How to Use the Book

012 Dedication Messages:

013 Prime Minister

014 Minister of Textiles

015 Secretary (Textiles)

016 Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) Foreword

017 Preface

018 Introduction

024-5 ZONE 1 : N/—NORTH

026 Jammu and Kashmir

048 Himachal Pradesh

062 Punjab

073 Chandigarh

074 Haryana

080 Rajasthan

124 Delhi

130-1 ZONE 2 : C/—CENTRE

132 Uttar Pradesh

168 Uttaranchal

178-9 ZONE 3 : E/—EAST

180 Bihar

194 Jharkhand

204 Orissa

236 Sikkim

240 West Bengal

266-7 ZONE 4 : S/—SOUTH

268 Andhra Pradesh

298 Tamil Nadu

336 Pondicherry

340 Kerala

362 Karnataka

390-1 ZONE 5 : W/—WEST

392 Goa

402 Dadra and Nagar Haveli

406 Daman and Diu

408 Gujarat

442 Maharashtra

458 Madhya Pradesh

480 Chhattisgarh

492-3 ZONE 6 : NE/—NORTHEAST

494 Assam

504 Arunachal Pradesh

514 Nagaland

520 Manipur

526 Mizoram

532 Tripura

540 Meghalaya

545 Sponsors

546 Technical Glossary

551 Annotated Bibliography of Archival Documents

556 Bibliography

558 Acknowledgements

561 Acknowledgements: Museums and Collections

562

Credits

564 Craft Categories

567 Index of Places

572 Index of Subjects

NORTH : N/

1.0 JAMMU AND KASHMIR N/JK 026 Kashmir N/JK 028

1.1 Papier-mâché N/JK 029

1.2 Kaleen – knotted carpets N/JK 030

030

1.3 Kashidakari – Kashmiri embroidery N/JK 032

032

033

1.4 Namda – felted rugs N/JK 033

033

1.5 Gabba – embroidered rugs N/JK 033

1.6 Walnut wood carving N/JK 034

wood carving N/JK 034

1.7 Pinjrakari and khatumband –wood work N/JK 035

1.7 Pinjrakari and khatumband –wood work N/JK 035

1.8 Wicker work N/JK 035

1.8 Wicker work N/JK 035

1.9 Copper ware N/JK 036 Jammu N/JK 037 Ladakh N/JK 038

1.9 Copper ware N/JK 036 Jammu N/JK 037 Ladakh N/JK 038

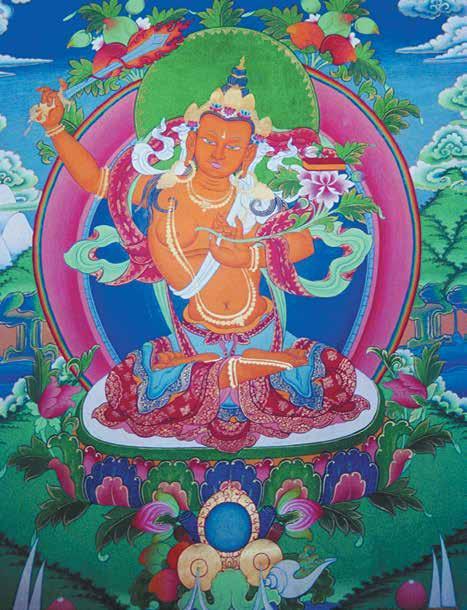

1.10 Thangka painting N/JK 039

1.10 Thangka painting N/JK 039

1.11 Ritual cloth installations N/JK 040

1.11 Ritual cloth installations N/JK 040

1.12 Khabdan – pile carpets N/JK 041

1.12 Khabdan – pile carpets N/JK 041

1.13 Tsug-dul and tsug-gdan –woollen pile rugs N/JK 042

1.13 Tsug-dul and tsug-gdan –woollen pile rugs N/JK 042

1.14 Challi – woollen textiles N/JK 043

1.14 Challi – woollen textiles N/JK 043

1.15 Hand-spinning N/JK 043

1.15 Hand-spinning N/JK 043

1.16 Paabu – stitched boots N/JK 044

1.16 Paabu – stitched boots N/JK 044

1.17 Thigma – tie-resist-dyeing N/JK 044

1.17 Thigma – tie-resist-dyeing N/JK 044

1.18 Metal work N/JK 045

1.18 Metal work N/JK 045

1.19 Wood carving N/JK 046

1.19 Wood carving N/JK 046

1.20 Painted wood N/JK 047

1.20 Painted wood N/JK 047

1.21 Basketry N/JK 047

1.21 Basketry N/JK 047

2.0 HIMACHAL PRADESH N/HP 048 Chamba N/HP 050

2.0 HIMACHAL PRADESH N/HP 048 Chamba N/HP 050

2.22 Lost wax metal casting N/HP 050

2.22 Lost wax metal casting N/HP 050

2.23 Silver jewellery N/HP 051

2.23 Silver jewellery N/HP 051

2.24 Chamba rumal N/HP 052

2.24 Chamba rumal N/HP 052

2.25 Chamba painting N/HP 053

2.25 Chamba painting N/HP 053

2.26 Embroidery on leather N/HP 053 Kangra N/HP 054

2.26 Embroidery on leather N/HP 053 Kangra N/HP 054

2.27 Thangka painting N/HP 055

2.27 Thangka painting N/HP 055

2.28 Dras-drub-ma – appliqué thangka N/HP 055

2.28 Dras-drub-ma – appliqué thangka N/HP 055

2.29 Metal work N/HP 056

2.29 Metal work N/HP 056

2.30 Wood work of Dharamsala N/HP 057 Kullu N/HP 058

2.30 Wood work of Dharamsala N/HP 057 Kullu N/HP 058

2.31 Basketry N/HP 059

2.31 Basketry N/HP 059

2.32 Doll making N/HP 059

2.32 Doll making N/HP 059

2.33 Thattar ka kaam – sheet metal work N/HP 060

2.33 Thattar ka kaam – sheet metal work N/HP 060

2.34 Knitted socks N/HP 060

2.34 Knitted socks N/HP 060

2.35 Pula chappal – grass footwear N/HP 061

2.35 Pula chappal – grass footwear N/HP 061

2.36 Kullu shawls N/HP 061

2.36 Kullu shawls N/HP 061

3.0 PUNJAB N/PB 062 Amritsar N/PB 064

3.0 PUNJAB N/PB 062 Amritsar N/PB 064

3.37 Khunda – bamboo staves N/PB 064

3.37 Khunda – bamboo staves N/PB 064

3.38 Galeecha – knotted carpets N/PB 065 Hoshiarpur N/PB 066

3.38 Galeecha – knotted carpets N/PB 065 Hoshiarpur N/PB 066

3.39 Carved and turned wood work N/PB 066

3.39 Carved and turned wood work N/PB 066

3.40 Panja dhurrie N/PB 067

3.40 Panja dhurrie N/PB 067

3.41 Wood inlay of Hoshiarpur N/PB 068

3.41 Wood inlay of Hoshiarpur N/PB 068

3.42 Wood and lac turnery N/PB 068 Patiala N/PB 069

3.42 Wood and lac turnery N/PB 068 Patiala N/PB 069

3.43 Phulkari and bagh – embroidered textiles N/PB 070

3.43 Phulkari and bagh – embroidered textiles N/PB 070

3.44 Nala – drawstrings N/PB 072

3.44 Nala – drawstrings N/PB 072

3.45 Tilla jutti – traditional footwear N/PB 072

3.45 Tilla jutti – traditional footwear N/PB 072

3.1 CHANDIGARH (Union territory) N/CH 073

3.1 CHANDIGARH (Union territory) N/CH 073

4.0 HARYANA N/HR 074 Haryana N/HR 076

4.0 HARYANA N/HR 074 Haryana N/HR 076

4.46 Palm leaf work N/HR 076

4.46 Palm leaf work N/HR 076

4.47 Sarkanda work N/HR 077

4.47 Sarkanda work N/HR 077

4.48 Brass ware N/HR 078

4.48 Brass ware N/HR 078

4.49 Jutti – leather footwear N/HR 078

4.49 Jutti – leather footwear N/HR 078

4.50 Surahi – pottery N/HR 079

4.50 Surahi – pottery N/HR 079

5.0 RAJASTHAN N/RJ 080 Jaipur N/RJ 082

5.0 RAJASTHAN N/RJ 080 Jaipur N/RJ 082

5.51 Blue pottery of Jaipur N/RJ 083

5.51 Blue pottery of Jaipur N/RJ 083

5.52 Kundan jadai – gem setting N/RJ 084

5.52 Kundan jadai – gem setting N/RJ 084

5.53 Meenakari – enamel work N/RJ 084

5.53 Meenakari – enamel work N/RJ 084

5.54 Lac ware N/RJ 085

5.54 Lac ware N/RJ 085

5.55 Razai – quilt making N/RJ 085

5.55 Razai – quilt making N/RJ 085

5.56 Bandhej and leheriya – tie-resist dyeing N/RJ 086

5.56 Bandhej and leheriya – tie-resist dyeing N/RJ 086

5.57 Block making N/RJ 088

5.57 Block making N/RJ 088

5.58 Block printing of Bagru and Sanganer N/RJ 089

5.58 Block printing of Bagru and Sanganer N/RJ 089

5.59 Mojari – leather footwear N/RJ 090

5.59 Mojari – leather footwear N/RJ 090

5.60 Handmade paper N/RJ 091

5.60 Handmade paper N/RJ 091

5.61 Felt products N/RJ 091

5.61 Felt products N/RJ 091

5.62 Bahi – clothbound books N/RJ 091

5.62 Bahi – clothbound books N/RJ 091

5.63 Sanjhi – paper stencils N/RJ 092

5.63 Sanjhi – paper stencils N/RJ 092

5.64 Terracotta of Sawai Madhopur N/RJ 092

5.64 Terracotta of Sawai Madhopur N/RJ 092

5.65 Stone work N/RJ 093

5.65 Stone work N/RJ 093

5.66 Katputli – puppets N/RJ 094

5.66 Katputli – puppets N/RJ 094

5.67 Wood and lac turnery N/RJ 094

5.67 Wood and lac turnery N/RJ 094

5.68 Gota work N/RJ 095

5.68 Gota work N/RJ 095

5.69 Tarkashi – metal inlay in wood N/RJ 095 Ajmer N/RJ 096

5.70 Phad painting N/RJ 097

5.69 Tarkashi – metal inlay in wood N/RJ 095 Ajmer N/RJ 096 5.70 Phad painting N/RJ 097

5.71 Miniature painting on wood N/RJ 097

5.72 Leather work N/RJ 098

Gorakhpur C/UP 156

7.142 Black pottery of Nizamabad C/UP 157

7.143 Terracotta and pottery C/UP 157 Varanasi C/UP 158

7.144 Wood and lac turnery C/UP 159

7.145 Repoussé C/UP 159

7.146 Wood carving C/UP 160

7.147 Carpets and dhurries C/UP 161

7.148 Meenakari – enamel work C/UP 162

7.149 Block printing C/UP 163

7.150 Zardozi – gold embroidery C/UP 163 Allahabad C/UP 164

7.151 Moonj basketry C/UP 165

7.152 Papier-mâché C/UP 166

7.153 Shazar stone jewellery C/UP 167

7.154 Date palm craft C/UP 167

8.0 UTTARANCHAL C/UT 168 Almora C/UT 170

8.155 Aipan – ritual floor painting C/UT 171

8.156 Ringaal basketry C/UT 172

8.157 Nettle fibre craft C/UT 173

8.158 Likhai – wood carving C/UT 173

8.159 Copper ware C/UT 174 Dehradun C/UT 175 8.160 Rambaans – natural fibre craft C/UT 176 8.161 Lantana furniture C/UT 176

8.162 Tibetan carpets C/UT 177

EAST : E/

9.0 BIHAR E/BR 180 Madhubani E/BR 182 9.163 Terracotta E/BR 183 9.164 Madhubani painting E/BR 184 9.165 Sujuni embroidery E/BR 186 9.166 Sikki craft E/BR 187 9.167 Papier-mâché E/BR 188 9.168 Lac bangles E/BR 188 Patna E/BR 189 9.169 Stone carving E/BR 190 9.170 Wooden toys E/BR 190 9.171 Khatwa – appliqué E/BR 191 Bhagalpur E/BR 192 9.172 Tribal jewellery E/BR 193 9.173 Jute work E/BR 193

10.0 JHARKHAND E/JH 194 Ranchi E/JH 196 10.174 Bamboo work E/JH 197 10.175 Dhokra – lost wax metal casting E/JH 198 10.176 Musical instruments E/JH 199 10.177 Tribal jewellery E/JH 200 10.178 Wall painting of Hazaribagh E/JH 201 Dumka E/JH 202 10.179 Jadupatua painting E/JH 203 10.180 Black terracotta E/JH 203

11.0 ORISSA E/OR 204 Ganjam E/OR 206 11.181 Ganjappa cards E/OR 207 11.182 Flexible fish – brass and wood E/OR 208 11.183 Brass and bell metal ware E/OR 208 11.184 Cowdung toys E/OR 209 11.185 Coconut shell carving E/OR 209 11.186 Betel nut carving E/OR 209 Bhubaneshwar E/OR 210 11.187 Talapatra khodai – palm leaf engraving E/OR 210 11.188 Pathar kama – stone work E/OR 211 11.189 Papier-mâché E/OR 211 Puri E/OR 212 11.190 Patachitra – painting E/OR 213

Pipili appliqué E/OR 214

Shola pith craft E/OR 214 11.193 Seashell craft E/OR 215 11.194 Coir craft E/OR 215 11.195

Cuttack E/OR 225

11.203 Chandi tarkashi – silver filigree E/OR 226

11.204 Stone carving E/OR 226

11.205 Sikki craft E/OR 227 11.206 Katki chappal – leather footwear E/OR 227

11.207 Brass and bell metal ware E/OR 228 11.208 Katho kama – wood carving E/OR 228 Koraput E/OR 229

11.209 Kotpad sari E/OR 230

11.210 Dongaria scarf – kapra gonda E/OR 230

11.211 Dhokra – lost wax metal casting E/OR 231 11.212 Tribal ornaments E/OR 231 11.213 Bamboo craft

234

11.217 Dhokra – lost wax metal casting E/OR 235

12.0 SIKKIM E/SK 236

12.218 Ku – Buddhist figurines E/SK 238 12.219 Choktse – tables E/SK 239

13.0 WEST BENGAL E/WB 240 Darjeeling E/WB 242

13.220 Wood carving E/WB 243

13.221 Beaten silver engraving E/WB 243

13.222 Hill painting E/WB 244

13.223 Carpet weaving E/WB 244

13.224 Konglan – stitched boots E/WB 245

13.225 Terracotta E/WB 246

13.226 Cane furniture E/WB 246 Cooch Behar E/WB 247

13.227 Sheetalpati – reed mats E/WB 248

13.228 Gambhira masks E/WB 248 Murshidabad E/WB 249

13.229 Shola pith craft E/WB 250

13.230 Metal ware E/WB 251 Birbhum E/WB 252

13.231 Leather craft E/WB 253

13.232 Terracotta jewellery E/WB 253

13.233 Kantha – patched cloth embroidery E/WB 254

13.234 Wooden toys E/WB 255

13.235 Sherpai – measuring bowls E/WB 255

13.236 Dhokra – lost wax metal casting E/WB 256

13.237 Clay work of Krishnanagar E/WB 256 Bankura E/WB 257

13.238 Terracotta of Bankura E/WB 258

13.239 Patachitra – scroll painting E/WB 259

13.240 Ganjifa cards E/WB 259

13.241 Conch shell carving E/WB 260

13.242 Coconut shell carving E/WB 260

13.243 Wood carving E/WB 261

13.244 Stone carving E/WB 261

13.245 Maslond – grass mats E/WB 262

13.246 Chhau mask E/WB 263

13.247 Lac-coated toys E/WB 263 Kolkata E/WB 264

13.248 Beaten silver work E/WB 265

: S/

14.0 ANDHRA PRADESH S/AP 268 Hyderabad S/AP 270

14.249 Bidri ware S/AP 271

14.250 Paagdu bandhu – yarn tie-resistdyeing S/AP 272

14.251 Banjara embroidery S/AP 273

14.252 Lac bangles S/AP 273 Warangal S/AP 274

14.253 Dhurrie weaving S/AP 275

14.254 Painted scrolls of Cheriyal S/AP 276

14.255 Nirmal painting S/AP 277

14.256 Lace making S/AP 278

14.257 Silver filigree S/AP 278

14.258 Dhokra – lost wax metal casting S/AP 279

14.259 Sheet metal work S/AP 279 Visakhapatnam S/AP 280

14.260 Wood and lac turnery of Etikoppaka S/AP 281

14.261 Veena – string instrument S/AP 281

14.262 Jute craft S/AP 282

14.263 Metal work S/AP 282 Machilipatnam S/AP 283

14.264 Block printing S/AP 284

14.265 Telia

17.337 Natural fibre crafts S/KE 351

17.337 Natural fibre crafts S/KE 351

17.338 Laminated wood work and inlay S/KE 351 Thrissur S/KE 352

17.338 Laminated wood work and inlay S/KE 351 Thrissur S/KE 352

17.339 Pooram crafts S/KE 353

17.339 Pooram crafts S/KE 353

17.340 Bronze casting S/KE 354

17.340 Bronze casting S/KE 354

17.341 Wood carving S/KE 355

17.341 Wood carving S/KE 355

17.342 Cane and bamboo craft S/KE 355

17.342 Cane and bamboo craft S/KE 355

17.343 Kora mat weaving S/KE 356

17.343 Kora mat weaving S/KE 356

17.344 Screw pine craft S/KE 356 Kannur S/KE 357

17.344 Screw pine craft S/KE 356 Kannur S/KE 357

17.345 Bronze casting S/KE 358

17.345 Bronze casting S/KE 358

17.346 Ship building S/KE 359

17.346 Ship building S/KE 359

17.347 Kathakali and Theyyam headgear S/KE 360

17.347 Kathakali and Theyyam headgear S/KE 360

17.348 Nettur petti – jewellery boxes S/KE 361

17.348 Nettur petti – jewellery boxes S/KE 361

17.349 Symmetric wood stringing S/KE 361

17.349 Symmetric wood stringing S/KE 361

18.0 KARNATAKA S/KA 362 Bangalore S/KA 364

18.0 KARNATAKA S/KA 362 Bangalore S/KA 364

18.350 Metal casting S/KA 365

18.350 Metal casting S/KA 365

18.351 Stone carving S/KA 365

18.351 Stone carving S/KA 365

18.352 Wood carving S/KA 366

18.352 Wood carving S/KA 366

18.353 Wood and lac turnery of Channapatna S/KA 367 Mysore S/KA 368

18.353 Wood and lac turnery of Channapatna S/KA 367 Mysore S/KA 368

18.354 Sandalwood carving S/KA 369

18.354 Sandalwood carving S/KA 369

18.355 Rosewood inlay S/KA 370

18.355 Rosewood inlay S/KA 370

18.356 Soapstone carving S/KA 370

18.356 Soapstone carving S/KA 370

18.357 Mysore painting S/KA 371

18.357 Mysore painting S/KA 371

18.358 Ganjifa cards S/KA 371

18.358 Ganjifa cards S/KA 371

18.359 Metal casting S/KA 372

18.359 Metal casting S/KA 372

18.360 Sheet metal embossing S/KA 372

18.360 Sheet metal embossing S/KA 372

18.361 Terracotta S/KA 373

18.361 Terracotta S/KA 373

18.362 Tibetan carpets S/KA 373 Mangalore S/KA 374

18.362 Tibetan carpets S/KA 373 Mangalore S/KA 374

18.363 Stone carving S/KA 375

18.363 Stone carving S/KA 375

18.364 Rosewood carving S/KA 375

18.364 Rosewood carving S/KA 375

18.365 Terracotta and pottery S/KA 376

18.365 Terracotta and pottery S/KA 376

18.366 Bhoota figures S/KA 377

18.366 Bhoota figures S/KA 377

18.367 Yakshagana costume making S/KA 377

18.367 Yakshagana costume making S/KA 377

18.368 Bronze casting S/KA 378

18.368 Bronze casting S/KA 378

18.369 Areca palm leaf craft S/KA 379

18.369 Areca palm leaf craft S/KA 379

18.370 Mooda – rice packaging S/KA 379 Bellary S/KA 380

18.370 Mooda – rice packaging S/KA 379 Bellary S/KA 380

18.371 Terracotta and pottery S/KA 380

18.371 Terracotta and pottery S/KA 380

18.372 Banjara embroidery S/KA 381

18.372 Banjara embroidery S/KA 381

18.373 Sheet metal embossing S/KA 381

Bijapur S/KA 382

18.373 Sheet metal embossing S/KA 381 Bijapur S/KA 382

18.374 Surpur painting S/KA 383

18.374 Surpur painting S/KA 383

18.375 Bidri ware S/KA 383

18.375 Bidri ware S/KA 383

18.376 Sheet metal work S/KA 384

18.376 Sheet metal work S/KA 384

18.377 Banjara embroidery and quilts S/KA 385

18.377 Banjara embroidery and quilts S/KA 385

18.378 Wood carving S/KA 385 Belgaum S/KA 386

18.378 Wood carving S/KA 385 Belgaum S/KA 386

18.379 Gold jewellery and silver ware S/KA 387

18.379 Gold jewellery and silver ware S/KA 387

18.380 Navalgund dhurrie S/KA 388

18.380 Navalgund dhurrie S/KA 388

18.381 Kasuti embroidery S/KA 389

18.381 Kasuti embroidery S/KA 389

WEST : W/

WEST : W/

19.0 GOA W/GA 392 Goa W/GA 394

19.0 GOA W/GA 392 Goa W/GA 394

19.382 Kashta kari – wood carving W/GA 395

19.382 Kashta kari – wood carving W/GA 395

19.383 Crochet and lace work W/GA 396

19.383 Crochet and lace work W/GA 396

19.384 Menawati – candle making W/GA 396

19.384 Menawati – candle making W/GA 396

19.385 Otim kaam – brass ware W/GA 397

19.385 Otim kaam – brass ware W/GA 397

19.386 Boat making W/GA 398

19.386 Boat making W/GA 398

19.387 Terracotta W/GA 398

19.387 Terracotta W/GA 398

19.388 Coconut based crafts W/GA 399

19.388 Coconut based crafts W/GA 399

19.389 Dhaatu kaam – copper ware W/GA 400

19.389 Dhaatu kaam – copper ware W/GA 400

19.390 Shimpla hast kala – seashell craft W/GA 400

19.390 Shimpla hast kala – seashell craft W/GA 400

19.391 Maniche kaam – bamboo craft W/GA 401

19.391 Maniche kaam – bamboo craft W/GA 401

19.392 Fibre craft W/GA 401

19.392 Fibre craft W/GA 401

20.0 DADRA AND NAGAR HAVELI W/DNH 402 (Union territory)

20.0 DADRA AND NAGAR HAVELI W/DNH 402 (Union territory)

20.393 Bamboo fish traps W/DNH 404

20.393 Bamboo fish traps W/DNH 404

20.394 Bamboo baskets W/DNH 404

20.394 Bamboo baskets W/DNH 404

20.395 Terracotta and pottery W/DNH 405

20.395 Terracotta and pottery W/DNH 405

20.396 Fishing nets W/DNH 405

20.396 Fishing nets W/DNH 405

21.0 DAMAN AND DIU (Union territory) W/DD 406

21.0 DAMAN AND DIU (Union territory) W/DD 406

21.397 Crochet and lace work W/DD 407

21.397 Crochet and lace work W/DD 407

21.398 Tortosie shell and ivory carving W/DD 407

21.398 Tortosie shell and ivory carving W/DD 407

22.0 GUJARAT W/GJ 408 Kachchh W/GJ 410

22.0 GUJARAT W/GJ 408 Kachchh W/GJ 410

22.399 Clay relief work W/GJ 411

22.399 Clay relief work W/GJ 411

22.400 Painted terracotta W/GJ 411

22.400 Painted terracotta W/GJ 411

22.401 Kachchhi embroidery W/GJ 412

22.401 Kachchhi embroidery W/GJ 412

22.402 Rogan painting W/GJ 413

22.402 Rogan painting W/GJ 413

22.403 Bandhani – tie-resist-dyeing W/GJ 414

22.403 Bandhani – tie-resist-dyeing W/GJ 414

22.404 Appliqué W/GJ 416

22.404 Appliqué W/GJ 416

22.405 Namda – felted rugs W/GJ 417

22.405 Namda – felted rugs W/GJ 417

22.406 Leather work W/GJ 417

22.406 Leather work W/GJ 417

22.407 Wood and lac turnery W/GJ 418

22.407 Wood and lac turnery W/GJ 418

22.408 Wood carving W/GJ 418

22.408 Wood carving W/GJ 418

22.409 Ajrakh printing W/GJ 419

22.409 Ajrakh printing W/GJ 419

22.410 Silver work W/GJ 420

22.410 Silver work W/GJ 420

22.411 Bell making W/GJ 420 Rajkot W/GJ 421

22.411 Bell making W/GJ 420 Rajkot W/GJ 421

22.412 Bullock cart making W/GJ 422

22.412 Bullock cart making W/GJ 422

22.413 Wood with metal embossing W/GJ 422

22.413 Wood with metal embossing W/GJ 422

22.414 Pathar kaam/Sompura kaam –stone carving W/GJ 423 Ahmedabad W/GJ 424

22.414 Pathar kaam/Sompura kaam –stone carving W/GJ 423 Ahmedabad W/GJ 424

22.415 Kite making W/GJ 425

22.415 Kite making W/GJ 425

22.416 Block making

W/GJ 425

22.416 Block making W/GJ 425

22.417 Mata ni pachedi – ritual cloth painting

22.417 Mata ni pachedi – ritual cloth painting

22.418 Patola weaving

W/GJ 426

W/GJ 426

22.418 Patola weaving W/GJ 427

W/GJ 427

22.419 Mashru weaving

W/GJ 427

22.419 Mashru weaving W/GJ 427

22.420 Ari embroidery

W/GJ 428

22.420 Ari embroidery W/GJ 428

22.421 Bohra caps

22.421 Bohra caps

22.422 Wood carving

22.422 Wood carving

22.423 Silver ornaments

W/GJ 428

W/GJ 428

W/GJ 429

W/GJ 429

Betul W/MP 472

Betul W/MP 472

24.468 Dhokra – lost wax metal casting W/MP 473 Gwalior W/MP 474

24.468 Dhokra – lost wax metal casting W/MP 473 Gwalior W/MP 474

24.469 Stone carving W/MP 475 Mandla W/MP 476

24.469 Stone carving W/MP 475 Mandla W/MP 476

24.470 Stone carving W/MP 477

24.471 Wood carving W/MP 477

24.470 Stone carving W/MP 477 24.471 Wood carving W/MP 477

24.472 Terracotta and pottery W/MP 478

24.472 Terracotta and pottery W/MP 478

24.473 Gond chitrakala – tribal

24.473 Gond chitrakala – tribal painting W/MP 479

25.0 CHHATTISGARH W/CT 480 Sarguja and Raigarh W/CT

W/GJ 430 Vadodara

22.423 Silver ornaments W/GJ 430 Vadodara W/GJ 431

W/GJ 431

22.424 Sankheda furniture W/GJ 432

22.424 Sankheda furniture W/GJ 432

22.425 Pithora painting W/GJ 433

22.425 Pithora painting W/GJ 433

22.426 Silver ornaments W/GJ 434

22.426 Silver ornaments W/GJ 434

22.427 Agate stone work W/GJ 435

22.427 Agate stone work W/GJ 435

22.428 Bead work

W/GJ 435

22.428 Bead work W/GJ 435

22.429 Terracotta and pottery W/GJ 436

22.429 Terracotta and pottery W/GJ 436

22.430 Brass and copper ware W/GJ 437 Surat W/GJ 438

22.430 Brass and copper ware W/GJ 437 Surat W/GJ 438

22.431 Marquetry W/GJ 439

22.431 Marquetry W/GJ 439

22.432 Mask making W/GJ 439

22.432 Mask making W/GJ 439

22.433 Patku weaving W/GJ 440

22.433 Patku weaving W/GJ 440

22.434 Sujuni weaving

W/GJ 440

22.434 Sujuni weaving W/GJ 440

22.435 Vaaskaam – bamboo crafts W/GJ 441

22.435 Vaaskaam – bamboo crafts W/GJ 441

22.436 Devru – embossed metal W/GJ 441

22.436 Devru – embossed metal W/GJ 441

23.0 MAHARASHTRA W/MH 442 Kolhapur W/MH 444

23.0 MAHARASHTRA W/MH 442 Kolhapur W/MH 444

23.437 Kolhapuri chappal – leather footwear W/MH 445

23.437 Kolhapuri chappal – leather footwear W/MH 445

23.438 Ganjifa cards W/MH 446

23.438 Ganjifa cards W/MH 446

23.439 Wooden toys W/MH 446

23.439 Wooden toys W/MH 446

23.440 Chandi che kaam – silver ware W/MH 447

23.440 Chandi che kaam – silver ware W/MH 447

23.441 Sitar – string instrument W/MH 447 Pune W/MH 448

23.441 Sitar – string instrument W/MH 447 Pune W/MH 448

23.442 Terracotta and pottery W/MH 449

23.442 Terracotta and pottery W/MH 449

23.443 Tambaat kaam – copper and brass ware W/MH 450

23.443 Tambaat kaam – copper and brass ware W/MH 450

23.444 Uthavache kaam – metal embossing W/MH 450

23.444 Uthavache kaam – metal embossing W/MH 450

23.445 Bidri ware W/MH 451

23.445 Bidri ware W/MH 451

23.446 Metal dies and metal casting W/MH 451

23.446 Metal dies and metal casting W/MH 451

23.447 Dhurrie weaving W/MH 452

23.447 Dhurrie weaving W/MH 452

23.448 Ambadi – sisal craft W/MH 452

23.448 Ambadi – sisal craft W/MH 452

23.449 Taal, jhanjh, ghanta – brass musical instruments W/MH 453

23.449 Taal, jhanjh, ghanta – brass musical instruments W/MH 453

23.450 Banjara embroidery W/MH 453 Mumbai W/MH 454

23.450 Banjara embroidery W/MH 453 Mumbai W/MH 454

23.451 Warli painting W/MH 455

23.451 Warli painting W/MH 455

23.452 Terracotta and pottery W/MH 456

23.452 Terracotta and pottery W/MH 456

23.453 Bamboo work W/MH 456

23.453 Bamboo work W/MH 456

23.454 Patua kaam – jewellery stringing work W/MH 457

23.454 Patua kaam – jewellery stringing work W/MH 457

23.455 Stringing of flowers W/MH 457

23.455 Stringing of flowers W/MH 457

24.0 MADHYA PRADESH W/MP 458 Jhabua W/MP 460

24.0 MADHYA PRADESH W/MP 458 Jhabua W/MP 460

24.456 Wood carving W/MP 461

24.456 Wood carving W/MP 461

24.457 Pithora painting W/MP 462

24.457 Pithora painting W/MP 462

24.458 Terracotta and pottery W/MP 462 Indore W/MP 463

24.458 Terracotta and pottery W/MP 462 Indore W/MP 463

24.459 Block printing of Bagh W/MP 464

24.459 Block printing of Bagh W/MP 464

24.460 Bandhani – tie-resist-dyeing W/MP 465

24.460 Bandhani – tie-resist-dyeing W/MP 465

24.461 Leather toys W/MP 465 Ujjain W/MP 466

24.461 Leather toys W/MP 465 Ujjain W/MP 466

24.462 Wood carving W/MP 467

24.462 Wood carving W/MP 467

24.463 Papier-mâché W/MP 468

24.463 Papier-mâché W/MP 468

24.464 Bohra caps W/MP 468 Bhopal W/MP 469

24.464 Bohra caps W/MP 468 Bhopal W/MP 469

24.465 Zardozi – gold embroidery W/MP 470

24.465 Zardozi – gold embroidery W/MP 470

24.466 Jute craft W/MP 470

24.466 Jute craft W/MP 470

24.467 Wood and lac turnery W/MP 471

24.467 Wood and lac turnery W/MP 471

This volume of Handmade in India is encyclopaedic in nature and the mass of information has been organized in a manner that shows, at a glance, the relationships between the different categories of information. This regional mapping of the crafts presents information by dividing the country in three levels— zone, state, metacluster.

The division of India into six geographical parts follows the administrative zones adopted by the Office of the Development Commissioner of Handicrafts [DC (H)], India to reach development initiatives of the Government of India to the far-flung clusters in each zone or region. Therefore, in the book, India is divided into six zones: North, Centre, East, South, West and Northeast. These six zones are separated in the book by section dividers, each with a map of the zone and a list of states and metacluster regions in that zone. A section is assigned to each zone. Pages are allocated to each state within a zone, according to the volume of information. Each state section in turn is subdivided into metacluster sections. Each metacluster region includes the particular production clusters located therein. The organization of the texts, image and navigational keywords used for the state pages, metacluster pages and craft pages is described further.

The organization of the various elements on the ‘state spread’ follows a common system across the book. Each state and union territory of India is introduced to the reader through a brief profile of the state, its geography, natural resources and socio-cultural setting. All these factors

Table of Zones and States:

Zone 1: N/—NORTH Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Chandigarh, Punjab, Rajasthan and Delhi.

Zone 2: C/—CENTRE Uttar Pradesh and Uttaranchal.

Zone 3: E/—EAST Bihar, Jharkhand, Orissa, Sikkim and West Bengal.

Zone 4: S/—SOUTH Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Pondicherry, Kerala and Karnataka.

Zone 5: W/—WEST Goa, Daman and Diu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh.

Zone 6: NE/—NORTHEAST Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, Tripura and Meghalaya.

have a bearing on the craft traditions of each region. Also located on this page is a map of the state showing the names of the metaclusters identified and included, along with names of the major cities or towns. Images distributed over the double page spread contain evocative expressions of typical landscapes, flora and fauna and people of the region. These pictures are supported by individual captions that describe some significant aspects of the state. The margins include a list of keywords contained under the following major headings—Crafts, Landmarks, Physical Features (major rivers and geographic identifiers), Biodiversity, Languages, Attire, Festivals and Cuisine. The page number of each state page can be found in the Table of Contents at the front of the book.

The states are divided into‘metaclusters,’ a grouping which is created for the purpose of this publication to give a quick reference to the crafts of each state. A metacluster is a geographical unit of smaller clusters in which field research was conducted. They comprise one or more districts and follow district boundaries. The bases for demarcating metaclusters were either geographical or in some cases even cultural proximity of districts. Some metaclusters have emerged from the concentration of crafts in a region. The metaclusters are identified in all cases by a district name. For instance, Metacluster Jammu takes its name from Jammu district.

Following are exceptions to metacluster names—Metacluster Kashmir lies in Srinagar district; likewise, Metacluster Bhubaneshwar lies in Khurda district; Metacluster Machilipatnam is in Krishna district and Metacluster Mangalore is

in Dakshina Kannada district. States of Chandigarh, Haryana, Goa, Delhi, Sikkim and Meghalaya have metaclusters by the same name as the state, as the size of the states and scale of craft activity allows for such rationalization. Union territories of Pondicherry, Daman and Diu, and Dadra and Nagar Haveli also have metaclusters by the same name as the states.

The symbol indicates a metacluster region. Metaclusters occur sequentially within a state. The single page layout used for each metacluster has images that provide an exemplary view of the metacluster and include local craftsmen in typical settings as seen in each region. The image captions provide additional information while the main body of text gives an overview of the significant features and the cultural history of each metacluster. This page also carries lists of keywords in the margins or in tables, which include the following: List of Subclusters covered in the study (which are marked on the Map), and a list of crafts that appear in the pages that immediately follow. Further, a table of resources lists Crafts, Raw materials and significant Sources in an easy to review matrix. Basic access information is included at the end of the main text to facilitate travel to the region.

The ‘crafts pages’ lie between metacluster pages. Individual crafts are displayed in accordance with their relevance and impact on the region’s economy, tradition and historicity. Each craft is titled wherever possible with the vernacular name of the craft. There is a description of the craft with definitions, context of making and using, and a summary of unique features

that help identify the particular craft expression with reference to its context in the particular metacluster where it is found. The same craft practiced elsewhere would have some different features. The pictures show selected objects that are typical of the craft described. There is a list of keywords under the following headings: names of production clusters of the craft, names of typical products made and names of tools and devices used in the craft. Keywords provided in the margin are followed throughout the book. They are also elaborated in Crafts Resource Directory of the series Handmade in India and organized as a master index with relevant information.

End matter and appendices

This section contains a technical glossary and bibliographic information, including an annotated bibliography of the unpublished craft documentation collection of the National Institute of Design, which is housed in the Knowledge Management Centre of the institute. The book has a comprehensive index to facilitate readers to locate infromation. An extensive list of people and institutions that have been acknowledged for their contribution to this volume has also been included.

SAMPLE Zone 3: E/—EAST Showing the states that comprise it.

The States comprising a Zone are divided into regions known as ‘Metaclusters’. Metaclusters comprise one or more districts and follow district boundaries.

MAYURBHANJ –District of Mayurbhanj

MAYURBHANJ

Mayurbhanj district

Bargarh district Sambalpur district

Sonepur district

Dhenkanal district

Jajpur district

Jharkhand

Phulbani district

Nawrangpur district

Rayagada district

Koraput district

KORAPUT: Districts of Nawrangpur, Kalahandi, Koraput, Rayagada and Phulbani.

Cuttack district

Khurda district

Ganjam district

GANJAM

Gajapati district

BHUBANESHWAR CUTTACK

PURI Puri district

BHUBANESHWAR (in Khurda district), takes its name from the city of Bhubaneshwar, which is the state capital.

SAMPLE STATE SPREAD

SAMPLE STATE SPREAD

NB: Vernacular Terms

NB: Vernacular Terms

Not all vernacular terms are explained in this volume. But will be elucidated in the ‘Vernacular Glossary’ in Crafts Resource Directory

Not all vernacular terms are explained in this volume. But will be elucidated in the ‘Vernacular Glossary’ in Crafts Resource Directory

Rathayatra

Holi

Chandan Yatra

Snana Yatra

Bali Yatra

Number of Districts and Craftpersons1* in the state.

State Name

Number of Districts and Craftpersons1* in the state. State Name

Vernacular Term described in detail.

Vernacular Term described in detail.

Craft List of the state in the state colour.

Craft List of the state in the state colour.

The State Text gives a brief social and cultural overview of the state that serves to explain its craft context.

The State Text gives a brief social and cultural overview of the state that serves to explain its craft context.

Map of the State shows metaclusters , major cities, towns and rivers. State Locator Map shows the location of the state within India.

Page Number includes Zone/State Name Abbreviation.

Page Number includes Zone/State Name Abbreviation.

1* Number of districts are as per the latest figures available from the Survey of India map references and the estimated population for the craftpersons in the State is obtained from the 2000 Census of the Ministry of Textiles. In case of Union territories or newly formed States, like Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, the craftspersons population is either unavailable or clubbed with the states from which they were carved out.

1* Number of districts are as per the latest figures available from the Survey of India map references and the estimated population for the craftpersons in the State is obtained from the 2000 Census of the Ministry of Textiles. In case of Union territories or newly formed States, like Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, the craftspersons population is either unavailable or clubbed with the states from which they were carved out.

SAMPLE METACLUSTER PAGE

SAMPLE METACLUSTER PAGE

Metacluster Locator Map shows the location of the metacluster within the state.

Metacluster Locator Map shows the location of the metacluster within the state.

Icon indicates Metacluster.

Icon indicates Metacluster.

Keywords contained under the headings: Subclusters of the metacluster. Crafts included in the metacluster.

Keywords contained under the headings: Subclusters of the metacluster. Crafts included in the metacluster.

Table of Resources: Matrix of Crafts, Raw Materials and Sources.

Table of Resources: Matrix of Crafts, Raw Materials and Sources.

Access information for reaching the metacluster.

Access information for reaching the metacluster.

Image Numbering

[3] or if more than one in a set [3, 3a, 3b].

Image Numbering [3] or if more than one in a set [3, 3a, 3b].

Number above, below or on side of image.

Number above, below or on side of image.

Keywords on the State Page contained under the headings : Physical Features, Biodiversity, Landmarks, Languages, Festivals, Attire, Cuisine.

Keywords on the State Page contained under the headings : Physical Features, Biodiversity, Landmarks, Languages, Festivals, Attire, Cuisine.

2* Map Legend appears alongwith the Scale at which the map appears. All maps have been verified and approved by the Survey of India. Only the maps on the State spread indicate a Scale; the maps on the Metacluster pages are not accorded a scale, as each region is enlarged in proportion to the space required to show all the craft clusters present.

2* Map Legend appears alongwith the Scale at which the map appears. All maps have been verified and approved by the Survey of India. Only the maps on the State spread indicate a Scale; the maps on the Metacluster pages are not accorded a scale, as each region is enlarged in proportion to the space required to show all the craft clusters present.

Metacluster Map shows all the Craft clusters in the metacluster.

Metacluster Map shows all the Craft clusters in the metacluster.

SAMPLE CRAFT PAGE

SAMPLE CRAFT PAGE

Name

Craft Name

State Colour Tab

State Colour Tab

Running Head consists of the zone/state/metacluster and appears on all craft pages.

Running Head consists of the zone/state/metacluster and appears on all craft pages.

Description of the craft with definitions, contexts of making and using, and a summary of unique features that help identify the particular craft expression with the metacluster in which it is found.

Description of the craft with definitions, contexts of making and using, and a summary of unique features that help identify the particular craft expression with the metacluster in which it is found.

Keywords contained under the headings: Production Clusters, Products and Tools.

Keywords contained under the headings: Production Clusters, Products and Tools.

NB: Production Clusters only indicate the craft villages, towns or cities actually visited by the research teams.

NB: Production Clusters only indicate the craft villages, towns or cities actually visited by the research teams.

Tool Box, with icon appears on most craft pages, as per the field research generated. Where possible, tools have been identified and named.

Tool Box, with icon appears on most craft pages, as per the field research generated. Where possible, tools have been identified and named.

Thepotisagod.Thewinnowing fanisagod.Thestoneinthe streetisagod.Thecombisa god.Thebowstringisalsoa god.Thebushelisagodandthe spoutedcupisagod.

Basavanna(1106-1167A.D.)

The handicrafts of India represent our rich cultural tradition. They embody our heritage of creativity, aesthetics and craftsmanship. At a more substantial level, the handicraft tradition has sustained generations of people in our country. As a highly decentralized activity, the handicrafts industry is a shining example of using local resources and local initiatives.

The handicrafts of India represent our rich cultural tradition. They embody our heritage of creativity, aesthetics and craftsmanship. At a more substantial level, the handicraft tradition has sustained generations of people in our country. As a highly decentralized activity, the handicrafts industry is a shining example of using local resources and local initiatives.

Through the ages, our handicrafts have fascinated the world. The beauty of these products and the skill and ingenuity they represent have few parallels anywhere in the world. They have set a benchmark of quality and excellence that is quintessentially Indian. The skills of our craftsmen reflected in our handicrafts became living symbols of our self-reliance and thereby inspired our freedom fighters to demand self rule. Since Independence, the Government of India has made a concerted effort to sustain the craft sector. In the process, a credible infrastructure of support has been put in place to augment the ability of craftspersons and to face growing challenges confronted by them. In the present era, it is essential for this industry to meet the challenges of globalization through innovation and upgradation of skills. The Government will continue to play a supportive role in this effort.

Through the ages, our handicrafts have fascinated the world. The beauty of these products and the skill and ingenuity they represent have few parallels anywhere in the world. They have set a benchmark of quality and excellence that is quintessentially Indian. The skills of our craftsmen reflected in our handicrafts became living symbols of our self-reliance and thereby inspired our freedom fighters to demand self rule. Since Independence, the Government of India has made a concerted effort to sustain the craft sector. In the process, a credible infrastructure of support has been put in place to augment the ability of craftspersons and to face growing challenges confronted by them. In the present era, it is essential for this industry to meet the challenges of globalization through innovation and upgradation of skills. The Government will continue to play a supportive role in this effort.

I also wish to commend this effort to systematically document our handicraft heritage. This handbook adds to the corpus of literature that deals with the viability and sustainability of the crafts sector in a world that remains in quest of unique offerings such as are produced by traditional craftspersons.

I also wish to commend this effort to systematically document our handicraft heritage. This handbook adds to the corpus of literature that deals with the viability and sustainability of the crafts sector in a world that remains in quest of unique offerings such as are produced by traditional craftspersons.

I extend greetings to all those associated with this publication and wish it all success.

I extend greetings to all those associated with this publication and wish it all success.

Manmohan Singh

New Delhi

August 31, 2005

New Delhi August 31, 2005

This documentation of India’s handicraft tradition and resource maps is a vehicle for bringing the world to craftsmen’s doorsteps in an age of rapid communication and global change. Numerous well-wishers and business partners from all over the world seek Indian craftsmen and their craftsmanship. The Ministry of Textiles and the Government of India are committed to provide the necessary support and encouragement that is needed to develop the handicraft sector of our country, since it is the source of high quality livelihoods for many of our people, particularly in the remote regions of our country.

Today the rural and urban crafts continue to make a hefty contribution to the economy of the country as they did in the past. In many cases this has been a hidden contribution since these did not necessarily get reflected in the visible part of our economy. For centuries, the rural artisans have been providing for the needs of local farmers and other rural inhabitants in the form of locally made products and services. The village melas or fairs and the weekly bazaars are full of locally produced crafts that are now admired across the world. With the advent of machine produced goods, many of our traditional artisans have had to face intense competition from a growing industrial sector. However, the inventiveness of the Indian craftsman and the various efforts at development that has been invested over the years in human resource development and in product innovation and promotion, has strengthened their ability to face this competition with a great degree of success.

Our crafts infrastructure and the market network that has been built with the active participation of the government, local bodies, NGOs and a vast network of our trade and service providers has helped the Indian crafts sector reinvent itself to face the world of tomorrow. This publication is one more effort in the direction towards our craftsmen achieving selfreliance and confidence to showcase their skills in order to attract users and craft lovers from all over the world to a new partnership that will take Indian crafts to the rest of the world.

Shri Shankersinh Vaghela Minister of Textiles Government of India

The Development Commissioner of Handicrafts has taken on a timely initiative to map and make available fairly comprehensive information about the vast range of handicrafts that provide livelihood and creative satisfaction to thousands of craftsmen in our country. The handicrafts traditions that have been continued undisturbed over the centuries have to face the realities of rapid change brought about by the inexorable forces of communication and globalization. Today they face many discontinuities and from the traditional role of providing all the artifacts of village life. Many crafts have over the years transformed themselves to becoming high citadels of skill through the active patronage of the state, local culture and religion. Hand skills and the handmade object have always had a special place in the minds of the initiated but many more have been drawn away by the glamour and glitter of industrially produced goods in a rapidly changing world order. Crafts are the lifeblood of a vibrant country. In our context this is the link that holds together the creative fabric of India.

The Development Commissioner of Handicrafts has taken on a timely initiative to map and make available fairly comprehensive information about the vast range of handicrafts that provide livelihood and creative satisfaction to thousands of craftsmen in our country. The handicrafts traditions that have been continued undisturbed over the centuries have to face the realities of rapid change brought about by the inexorable forces of communication and globalization. Today they face many discontinuities and from the traditional role of providing all the artifacts of village life. Many crafts have over the years transformed themselves to becoming high citadels of skill through the active patronage of the state, local culture and religion. Hand skills and the handmade object have always had a special place in the minds of the initiated but many more have been drawn away by the glamour and glitter of industrially produced goods in a rapidly changing world order. Crafts are the lifeblood of a vibrant country. In our context this is the link that holds together the creative fabric of India.

That the handicrafts are a viable means of production in India is not in doubt but the global change needs to be responded in kind, through the production of knowledge which can both preserve what is of value and make it available to the world at large. Our craftspeople who are being celebrated in the pages of this book, in three volumes, need this support to make their skills and knowledge accessible to the creative and sensitive consumers in search of the sublime and the spirit that is India. It is in these crafts and in the artifacts of our culture that the spirit of India resides. These volumes will preserve their knowledge for posterity and make available new avenues of access to the world of creative producers who can beat a path to the doorsteps of these craftsmen who hold the refined skills and knowledge of millennia.

That the handicrafts are a viable means of production in India is not in doubt but the global change needs to be responded in kind, through the production of knowledge which can both preserve what is of value and make it available to the world at large. Our craftspeople who are being celebrated in the pages of this book, in three volumes, need this support to make their skills and knowledge accessible to the creative and sensitive consumers in search of the sublime and the spirit that is India. It is in these crafts and in the artifacts of our culture that the spirit of India resides. These volumes will preserve their knowledge for posterity and make available new avenues of access to the world of creative producers who can beat a path to the doorsteps of these craftsmen who hold the refined skills and knowledge of millennia.

As people living in India, we have all been exposed to our crafts heritage from our childhood and in all regions of India the young have had these unique experiences and encounters with the local crafts that ingrained in them the material and spiritual sensibilities of the region and its culture. The traditional crafts manifest themselves in the temple architecture of the region as well as in the ubiquitous household products crafted with ingenuity from local materials and skills. Today, when we live and work in our metros, all of us in India, know that we have lost something dear, but it is the presence of some finely crafted objects in our ritual and festive occasions that bring back these valuable qualities to mind very sharply and in a clearly delineated fashion. From being mere curios on our shelves, the handicrafts of India must reinvent themselves to be the cherished objects that are in harmony with the needs and aspirations of future citizens of the world. It is only then that we can be sure of the renewal of interest and a sustainable future for the livelihoods and prosperity of the multi-million strong craftsmen community in India.

As people living in India, we have all been exposed to our crafts heritage from our childhood and in all regions of India the young have had these unique experiences and encounters with the local crafts that ingrained in them the material and spiritual sensibilities of the region and its culture. The traditional crafts manifest themselves in the temple architecture of the region as well as in the ubiquitous household products crafted with ingenuity from local materials and skills. Today, when we live and work in our metros, all of us in India, know that we have lost something dear, but it is the presence of some finely crafted objects in our ritual and festive occasions that bring back these valuable qualities to mind very sharply and in a clearly delineated fashion. From being mere curios on our shelves, the handicrafts of India must reinvent themselves to be the cherished objects that are in harmony with the needs and aspirations of future citizens of the world. It is only then that we can be sure of the renewal of interest and a sustainable future for the livelihoods and prosperity of the multi-million strong craftsmen community in India.

Shri R Poornalingam Secretary (Textiles)

Shri R Poornalingam Secretary (Textiles)

The Office of the Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) was set up for the socio-economic upliftment of handicrafts artisans and for the promotion and development of the handicraft sector within the country. This office has been striving to achieve qualitative improvement in production, increase in productivity of artisans for the augmentation of their income both at the individual and group level, creation of more employment opportunities to achieve a higher standard of living for craftpersons, and for the higher export of handicrafts from the country including preservation of our rich cultural and craft heritage.

The growth of the sector is being facilitated in a balanced manner to help six million craftpersons located in over 530 regional clusters identified in this publication. Our staff and officers at headquarters and field offices across the country are committed to provide various services for the development and growth of this sector in an efficient and transparent manner to achieve the goals. As is evident, the sector is multi-polar, with an enormous amount of diversity in cultural manifestation, traditions, raw materials, techniques and applications that represent various regions and districts of India. The complexity of managing the sector and providing services at the doorsteps of craftpersons requires in-depth knowledge and a deep insight of their traditions, needs and aspirations. Due to the well distributed infrastructure of Regional Offices, Design and Technical Development Centres, Marketing and Service Extension Centres, this office has been able to provide support to craftpersons. A national network of trainers, master craftpersons and Shilp Gurus, are our important partners in carrying forward the craft traditions and its values to a much larger base of performing artisans.

I am sure that this documentation of the Indian craft heritage with geo-specific locations, materials and processes will be a tool for creating awareness about the craft traditions of India, all over the world. This book will not only facilitate importers and exporters of handicrafts to identify craft concentration areas for sourcing their requirements but will also help scholars in carrying out research in the area of their interest. It will further be of help to artisans seeking to protect their craft traditions and designs under GIA or IPR Acts and help policy makers in designing appropriate strategies for the development of this sector.

The National Institute of Design (NID) team, which worked systematically with dedication and zeal, deserves full credit and appreciation for bringing out this landmark publication. I hope this publication will not only be interesting to the reader but will also be able to generate awareness amongst them, which will take Indian handicrafts to a new height in the global arena.

Sanjay Agarwal, IAS Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) & Ex-Officio Joint Secretary

The Office of the Development Commissioner (Handicrafts), Ministry of Textiles, Government of India was established with the mandate of serving and strengthening one of the most significant segments of the non-agricultural sector of the Indian economy—the handicraft sector—focusing on employment generation and providing sustainable livelihood. Handicraft or craft as is commonly understood is primarily an occupational art, which requires some skills and creativity to think, imagine, and visualize in order to produce an artistic and cultural object. These cultural and ethnographic objects represent traditional art and craft and local technologies practiced by the indigenes of a locality portraying their cultural values. The objects or the process involving their manufacturing is a knowledgerepository and representative of the era and period during which they were originally created or used as cultural elements and as a means of augmenting socio-economic returns for improving their standards of living.

Globalization, open markets and changing economic borders and barriers have significantly altered the perspective and vision with which handicrafts is viewed today. Traditional know-how has regained its significance as a base for knowledge which can be utilized for the welfare of all. In this era of knowledge and debate on ownership and protection of intellectual property rights gaining momentum, it has become imperative to mine, assimilate, document the vast knowledge, collected and collated by the Department over the years and present it in a manner where it would become useful for further research, point of reference for trade, knowledge base for designers and a database for policy makers.

This document is also meant to pave the way for legislative or legal framework in providing the rural, semi-urban communities, their due share of economic returns and recognition by way of different mechanisms available currently or will become available in the near future, where the intellectual property is collectively shared by the indigenes who have practiced and proliferated the knowledge over centuries.

Tinoo Joshi Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) Government of India

Traditional crafts are innovations of yesterday. Crafts define not only the cultural moorings but also the search for economic sustenance. The craftsmen derive their inspiration, innate wisdom and skills not from books but from nature and their surroundings. Crafts reflect the immense creativity of ordinary people and their quest for self-expression and fulfillment. Just as human evolution, crafts also evolve over time by mixing and churning infl uences and events. A country’s creative history is decipherable from the metal, pottery, textiles, and scores of other crafts, which were prevalent in its different regions. India is seen by the discerning not just as a country but as one that produced a rich civilization. Despite the ruptures of history, invasions and foreign occupation, Indian crafts continued to lead the way in many respects. The innovativeness and creative expressions in textiles, stones and jewellery have captured the imagination of the world.

The vicissitudes of history and the tides of time have not robbed the enchanting diversity, rich landscape and beauty of Indian crafts. The aesthetics of India, reflected through the crafts and its forms, shapes and its colour palette are almost like the cuisines of India reflecting the great diversity and tastes. The multitude of hues and forms seen in the shandys and the melas of India tell the stories of hundreds of crafts that belong to a vast country with 18 major and 1600 minor languages and dialects, 6 major religions, 6 major ethnic groups, 52 major tribes, 6400 castes and subcastes, 29 major festivals and over 1 billion people, 50 per cent of them in rural areas, spread over coast lines, valleys, hills, mountains, deserts, backwaters, forests and even inhospitable terrain. It is not easy to grasp the breadth and depth of Indian craft. There are more than 23 million craftsmen engaged in different craft sectors and it is estimated that there are over 360 craft clusters in India.

‘Living’ culture and ‘evolving’ crafts are required to preserve both culture and crafts. The laudable endeavour by the Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) to present, in a directory, authentic information and visual images of handicrafts from every nook and corner of India is a herculean endeavour. The National Institute of Design has been studying and sustaining craft related design interventions for over four decades as part of its education, outreach and services. This is perhaps the reason that the Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) decided to engage NID in preparing this magnum opus on the world of handicrafts. NID’s mandate for searching indigenous solutions and an Indian idiom in design have often led to linking yesterday’s innovations with today’s. Thus for NID, this task, though arduous, has also been very edifying and fulfilling.

The team at NID, consisting of many field researchers, editors, designers, and copy writers, have all passed through moments of despair and delight. After toiling hard and struggling with resources and time over nearly three years, the dedicated team led by Mrs Aditi Ranjan our senior faculty member has succeeded in celebrating crafts in a publication which has both the magic of hands and creative spirit of the unsung heroes of crafts. As Aldous Huxley said, “Culture is like the sum of special knowledge that accumulates in any large united family and is a common property of all its members.” We can replace the word ‘culture’ in this case with ‘craft’ and in the context of the book, it would be just right.

Handmade in India represents the sum of the special knowledge from India’s united family and it captures vividly the intellectual property which has created wealth for generations and which will continue creating it and multiplying it in the times to come. Many of the crafts clusters have the potential of linking the product range from a geographical indication and branding perspective under the WTO regime. In the emerging arena of world competition led by the frameworks of WTO, this book will be a repository of heritage and inspiration for all those seeking wealth, from India as well as from all parts of the world. In a globalizing and increasingly digital world, which is searching for emotional and cultural connections, crafts can bring forth harmony. In the emerging knowledge economy, crafts and folklore will form the foundations for the nation’s wealth, especially in countries like India, which has a magnificent heritage and a glorious future. I am truly delighted to present this book to the readers on behalf of the National Institute of Design, to provide inspiration and sustenance to the generations ahead.

Dr. Darlie O. Koshy Executive Director, NID Ahmedabad

Handmade in India is a tribute to the Indian craftsperson. His or her uncanny understanding of materials is combined with mastery of the tools, techniques and processes that have evolved over the centuries through social and cultural interactions. Today this craft continuum constitutes an enormous resource that can be harnessed for the future development of our society.

This volume provides a geographic organization of craft di stribution across the length and breadth of the country and shows how craft permeates even the remotest corner of India. In this introduction we have tried to summarize the enormity of craft variety and the significant role that it plays in the day-to-day lives of both rural and urban people.

The panorama of Indian crafts is a patchwork quilt of many hues and shades of meaning, reflective of interactions with social, economic, cultural and religious forces. And the craft world is full of contrasts, a universe of utility products and sacred objects, articles for ritual use and ephemeral festival crafts, representing many levels of refinement—from the simplest to the most technically advanced. Likewise there are many perceptions of the term ‘craftsman,’ ranging from a manual labourer to a worker of high artistic excellence. Craft, then, is situated in a complex milieu, a dense matrix of many strands and elements. To understand this, our study undertook many months of fieldwork and research. Throughout, our research was guided by the conviction that the context informs the structure, language and form of crafts.

The aim of this three-volume publication is to showcase the creative potential of Indian craftspersons and make available a directory of resources—skills, materials, capabilities and products. The products embody the craftsperson’s understanding that is structural, conceptual and aesthetic, just as cr aft is also an interrelation between function, form, material, process and meaning. The directory unveils the product not only as an end but also as a seed for new possibilities and directions, a creative potential and palette of resources. The crafts of India are at the threshold of massive change and it is hoped that this publication will help capture the many facets of the current scenario and promote a better understanding of the milieu, issues and resources that it offers for designers and layman alike to influence economic change at the grassroots level.

The range and diversity of Indian crafts is staggering. To understand this diversity one would need to look at numerous dimensions that include all the historical processes that shaped the transformations of our society over time. Social and cultural diversity has multiplied particular forms of artefacts, each shaped by a multitude of forces leading to the vast canvas of variety that can be witnessed today. Modernity tends to have universal forms that homogenize cultures across continents that are seen as an outcome of communication and globalization. On the other hand, the prolific variety was a result of each regional or sub-regional group asserting its own identity in the objects and cultural expressions. Therefore the vast array of artefacts, implements, built environments, ornaments, clothing, headgear and personal body decorations all showed the deep need for holding on to their unique identity as distinct from that of their neighbours.

India is a land of immense variety, a land of vast biodiversity and climatic zones from the sea-level coastal settlements to the extreme habitats built on top of lofty snow-covered mountains. Similarly regions of very heavy rainfall and abundant vegetation are contrasted with dry deserts, each with appropriately evolved housing and other built forms that find a resonance with the particular climatic zone in which it has evolved. Much can be learnt from the manner in which local communities have invented solutions to tackle the diversity of climates. These solutions are both a creative response for survival and celebration alike—the bamboo rainshields of Assam, Tripura and Meghalaya are worn by farmers as headgear while the palm leaf sunshades of Andhra Pradesh are carried as umbrellas by shepherds or used as shelters in open-air weekly markets. The jhappi, bamboo rainshield of Assam, is decorated with red appliquéd forms and transformed into a votive offering that symbolizes a good harvest. These creative community responses represent the triumph of the human spirit over the forces of nature. Community responses mark many craft developments, initiated when sensitive craftsmen

and their clientele interact in the bazaars and at points of exchange. These interactions have a collective impact on the form of the craft offering that no single craftsman could have produced, a perfect fit with the environment and with the social mores that the community aspires to. The climate helps determine the nature of material availability, in some places in abundance and in others as an extremely scarce commodity, which in turn influences the value attributed to that material in the given context. We see examples of non-precious materials treated like royalty in zones of scarcity, sometimes preserved for many generations to mature before it is put to use. On the other hand the response to abundance could be seen in the free abandon with which materials are crafted into objects of function or celebration.