Cross-Fertilization of Style in Buddhist, Hindu and Jain Cave Temples

Cross-Fertilization of Style in Buddhist, Hindu and Jain Cave Temples

Cross-Fertilization of Style in Buddhist, Hindu and Jain Cave Temples

Klein and Arno Klein

For Professor Walter Spink, who taught us how to see when we thought there was nothing more to see.

Naman Parmeshwar Ahuja

Iconographic experiments, structural developments, and accretions to the oral tradition were given fixed literary and artistic forms by the fifth century ce, borne out by texts like the Linga, Agni, and Vishnudharmottara Purana s. Ellora is amongst the sites that became active soon after their composition with which they share some general concepts that undergird images. More specifically, they can be related to canons of iconography and iconometry as preserved in them. Ellora and its contemporary sites occupy primacy in art history for this reason. These are architectural spaces that encourage us to reflect on the parallels between text and image. Adjectives like awesome may be trite, but Ellora’s sculptures, larger than lifesize scale, their extraordinary compositional strength, and the poetic symbolism with which they are all communicated, do evoke hyperboles. And yet art historians are taught that while Ellora may be grander than all other similar sites, it is not a oneoff. It needs to be contextualized within the oeuvre of other major temples in Elephanta, Badami, and Mahabalipuram. This book provides an introduction to Ellora’s Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain shrines and their chief iconographic concerns. It compares these sculptures and the architectural features in which they are emplaced with those at other sites, and questions a rather puzzling aspect of their patronage: which portions of these shrines are left unfinished, and why?

In this Foreword, I shall try to delve deeper into the milieu that influenced the pedagogy of the patrons of Ellora and in turn, their expectations of their sculptors. As mighty as the scale of the enterprise is the level of thought behind the sculptural iconography. The symbolism in each composition reveals a satisfying connection with aesthetic principles in literature—even paralleling rules of linguistics and grammar—a co-relationship with a rich array of mythological texts and a worldview that shows awareness of the branches of philosophy. How does that inform us of the interdisciplinary environment within which sculptural training was imparted? With its grand sculptures carved permanently in living rock, Ellora allows us to seek logic in placement of a sculpture, its location in a

sequence of ideas. This kind of a deep iconological study is dependent, however, first on an iconographic identification of the sculptures and on the appreciation of their form. Similarities in sculptures across sites emerge on careful observation—making evident that what is being studied is part of a pattern, a tradition.

There is no single hierarchy of Indian images. The pantheons of deities vary according to region, cult, caste, and historical or political context. There is, however, a more or less fixed language of communication employed by the images. Using mudra s (gestures), asana s (postures) and a finite range of visual symbols usually thought of as attributes, sculptors created an iconographic vocabulary certainly by the first century bce, if not earlier. Gods and goddesses are shown holding different objects that are symbolic. Martial attributes such as swords, tridents, axes, and spears suggest, for example, that the divinity can cut through ego or ignorance; a lotus flower is seen as a symbol of purity, transcendence, and wisdom; a chakra (wheel) is both a weapon and a symbolic reference to kala (cyclical time) where death is followed by rebirth. By the first century ce, although many attributes had become associated with specific images, artists continued to add to the repertory as new revelations or visions of divinity developed. Once the system of communicating ideas through images was fixed, the sculptors’ lexicon or vocabulary of symbols could be used to read any mythological narrative in its visual form, with every image given its own nama (name) and rupa (form) using that vocabulary of symbols. More intrepid visitors at Ellora experiment by disaggregating sculptures, looking at their details, allowing their focus to settle on any two arms in a multi-armed figure and then one begins to see the same composition anew, even reading new meaning into the symbolism of the sculpted body, as its different attributes are paired. Each pairing is perfectly balanced.

Such genius and the confidence of sculpting at this scale are achieved after centuries of investment in the training of

sculptors. Precise rules are provided in Indian art historical texts1 on how the gods, or rather supernatural figures, are to be made. Their idealized bodies are not canonized in myth alone but are accompanied by explicit rules of art production that specify details such as their countenance and mood, deportment, and physical proportions. These are elaborated down to the last detail on the number of hairs that will be appropriate from each follicle, whether curls should turn clockwise or anticlockwise, etc. Reading these ancient texts alongside mythology reveals an exhaustive capacity for elaboration as well as communicates to us the seriousness with which art practice was observed.

Moreover, rules of iconometry are important because they demonstrate in painstaking detail, not only what is codified, but also how it is to be codified. Whether in Hindushahi Afghanistan, Hund in Pakistan or Kashmir, these sculptures appear to follow the same dynamism and aesthetic milieu as the imagery in Ellora, Mahabalipuram, and Badami. Is this because of a widespread dissemination of a Puranic corpus? Are these temples, their sthapatis (architects/foremen of artists), and those in charge of guilds of craftsmen, part of a wider administrative apparatus that spread from Kanchi to Kabul?

To answer these complex questions, one has to consult the numerous texts that govern this subject which are actually not all identical. Some principles appear to be common, such as the effect of the zodiac and nakshatra s (constellations) on the body, or the role of caste in determining the shape, form, and color of bodies. However, in their specific details, ancient texts may differ from each other. Iconometric information in the shastra s that are related to art and architecture in northern and central India comes from texts such as Mandana’s Vastushastra, Bhuvanadeva’s Aparajitapriccha, and Maharaja Bhoja’s text called Samaranganasutradhara. The shastra s applicable to southern India include the Manasara, which is an important text on architecture, as is the Mayamatam, among several others. The Agama s are books that detail specific systems of technical knowledge, which also tend to be region-specific and are usually dated between the tenth and thirteenth centuries. The ones that deal with proportion systems for making images are divided into a northern group and a southern group, and into Vaishnava, Shaiva, and Shakta groups. Each of these comprises further divisions, which detail how to make specific

images that belong to the iconographic plan of the mythic cycle of a particular deity.

This kind of variety might seem perplexing and unfortunately has led many modern art historians to discount their usefulness: limited as they seem to be to a varied set of ideals created in a variety of courts across South Asia in different periods. But what a substantial corpus of ideals they are. And, surely, that is indicative of the kind of intellectual investment in art that came along with the actual sculpting, building, and painting.

Perhaps the lack of consistency can be understood better if we compare the ancient books on art and architecture with those on music—the Sangitashastra s. There too, details vary; we get the names of raga s but not practical notations of music, and yet what becomes clear is that there is an elaborate vyakarana (grammar) that undergirds music. A raga is very much bound by rules just as sculptures are. They have an iconography (just as symbols, attributes, and the tala-mana iconometric system govern the communication of an accurate image), so to do specific notes, communicate an accurate raga. One raga cannot be contaminated by another, they insist. The rules meant for each are said to be strict, yet the rules are not explicit. And, sure enough, when musicologists trace the history of specific raga s, they note that while their iconography may indeed vary from place to place, they also possess some overarching principles that allow them to be recognized as being related to that particular raga, to a particular shade of light at a specific time, to complement a particular season in a state of mind or even health, no matter where in South Asia the music is heard. Writings that played with these aesthetic determinants had come to an elaborate crescendo in the literature of South Asia at the very times when the shrines at Ellora were being made and used. Further, we have much to learn from the iconographic system of raga s, which too end up being turned into a visual system: As for instance, the ragamala paintings. Each raga can be easily personified because of its distinct iconography. Visual and performing arts share not just a common system but a common vocabulary as well.

However, from where we stand today, removed from the repartee of the spirit of the age captured in its libraries of Sanskrit, these texts can be bewildering in their detail and unrelenting in their capacity to enumerate iconographic

Deepanjana Klein

Ellora was a place I dreamed of as I began my undergraduate days in 1989 as an art student in Santiniketan. I was finally able to visit Ellora in 1993, and it was love at first sight. As I write about it three decades later, I still feel the excitement of seeing the caves for the first time. My love for the site has only grown stronger, my admiration for the sculptors has only grown deeper, and the urgency I feel to spread awareness about this brilliant creation makes me restless.

I am grateful to Walter Spink, my friend and guide who introduced me to the caves. He took me around Ellora so many times over the years, always with the same level of enthusiasm, exclaiming at every peg and hole in the wall, mysteries waiting to be solved. I named my daughter Ellora in tribute to the site, and Walter was like a grandfather to her. I wanted to publish this work during his lifetime, but life had other plans. So, as I write today, Walter is with me. When I began to go through my doctoral thesis anew, it was clear that I could not do justice to this site alone. So, over months, I began to assemble a group of scholars who share the same passion, dedication, and scholarship for the site. I hope their work in this collection of essays will foster the same excitement that Walter planted in me thirty years ago.

The photographic documentation for this book would not have been possible without Arno Klein, who has been coming back to the site with me over decades. I would like to share with our readers Arno’s account of one such trip, to give a sense of his perseverance that brought you these magical images:

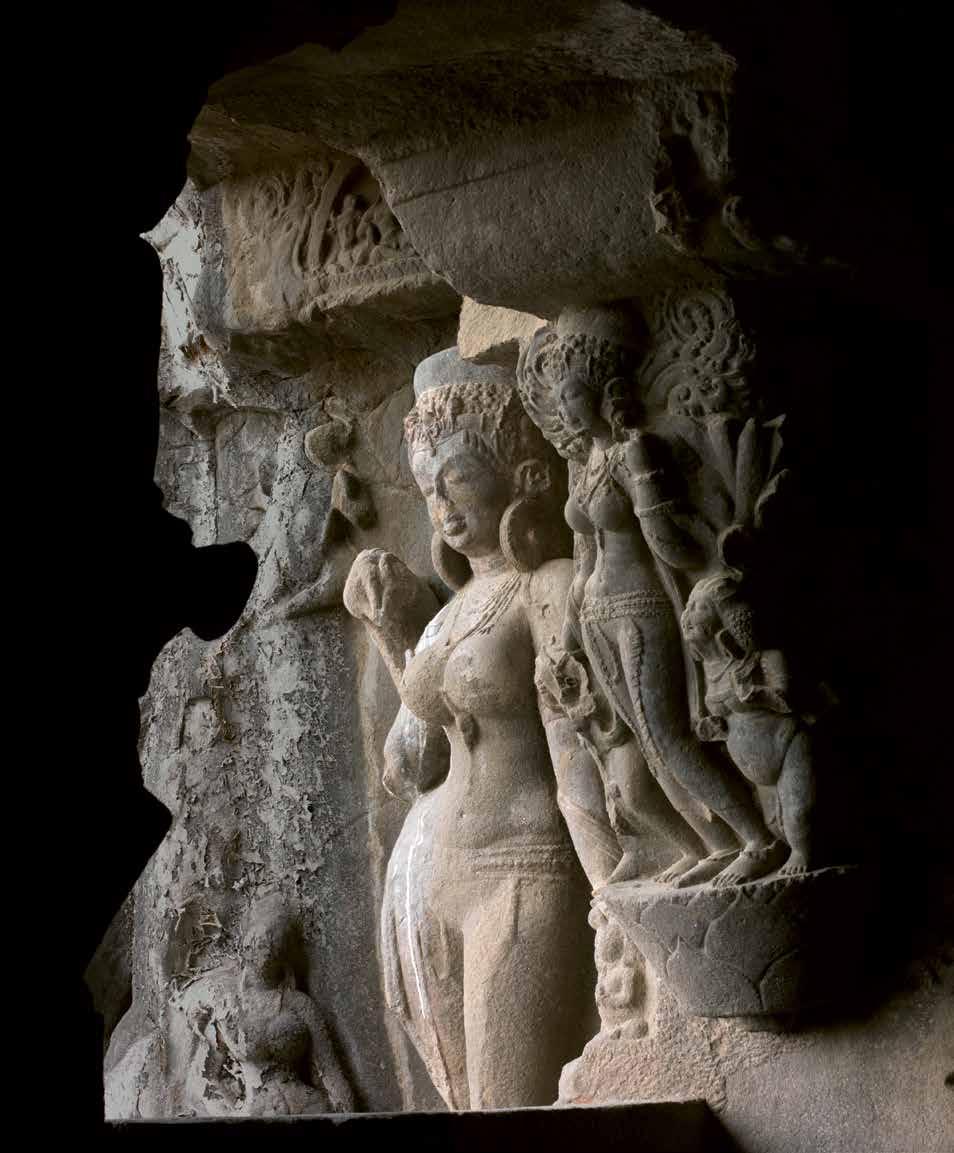

In the 1990s, Deepanjana and I made one of many trips to document Ellora, and, on that occasion, I was not granted permission to use a tripod or artificial lighting. It required some patience to photograph a subject of pitted rock on a backdrop of pitted rock, in the dark, with a digital camera of that era. In one of the Jain caves, I repeatedly tried to capture an image of a minor bas relief of a Jina. I held my breath for each shutter release, to try and record something more than an inscrutable blur. Holding my breath had a side benefit—in the dark, humid, hot cave, you can’t always see, but can hear and most definitely smell the presence of other creatures in the stale air. Inhale Freeze Click . I crushed dead cockroaches underfoot who had once feasted on guano. Crunch . Freeze Click . I felt urine trickle down my back, as bats shrieked above. Shiver Freeze. Click . Dozens of failed attempts in, I lowered my camera and started taking mental snapshots, as the light changed expressions and the life around me continued, unperturbed.

Nandi; Dashavatara, Cave 15, upper floor

Stanislaw J. Czuma

I think I am well-qualified to pay tribute to the great art historian and beloved teacher Professor Walter Spink, since he was my true “guru”—spiritual teacher—in addition to being my academic advisor. He guided me through my graduate years at the University of Michigan (1961–1968). I was his first PhD student, and I began working with him from the moment I joined the university in 1961.

That was the first year of my studies in the USA. In my twenties, I had just arrived from the Sorbonne to continue work in Indian and Southeast Asian Art. Still inexperienced in matters of the American educational system, I was received with understanding and assistance from Walter, which over the course of the years grew into a wonderful friendship. Soon after my arrival, I became a graduate assistant involved in the photographic art archives for the University of Michigan. In 1962, we traveled together to India and Southeast Asia, which was an unforgettable trip. The same year, I married Ingrid, a charming Swiss woman whom I met in Paris. Our ties with Walter, his wife Nesta, and their three children, became very close, making us feel a part of their family.

Walter had an incredible command of Indian/Southeast Asian art and civilization and an unusual ability to share this expertise with his students, gaining their great respect and admiration. He had an uncanny talent for making his audience interested in any given subject. His subtle humor and enterprising lecturing style made him very popular with his students.

Walter graduated from Harvard in 1954, where he worked under the close supervision of Benjamin Rowland, the American pioneer in Indian studies. His first employment was with the University of Brandeis, where he taught for six years (1956–61), moving to the University of Michigan in 1961 and remaining there until his retirement in 2000.

Professor Walter Spink , Michigan, 2003

Deepanjana Klein

A quiet village named Elapura was chosen, over a thousand years ago, to be the site where powerful dynasties would bring their best artists, artisans, and architects to showcase their talents and the devotion the kings and their subjects had for the gods of their faith. Over centuries, the site evolved, changing hands and faiths, and we are the recipients of this gift of a magical place called Ellora, home of the greatest Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain rock-cut cave temples in India.

Sprawling over two kilometers, the Ellora Caves are a stunning testament to ancient Indian art. Carved into the Charanandri Hills, nearly all of the 34 principal caves at this site are adorned with intricate sculptures and elaborate facades that depict mythological scenes and daily life. Clustered by religion, the caves are arranged south to north—Buddhist (Caves 1–12) to the south, Hindu (Caves 13–29) just to the north, and Jain (Caves 30–34) farther north. Unlike many other historical sites that focus on a single religious tradition, Ellora harmoniously combines Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain elements, reflecting a period of religious tolerance and cultural exchange. Several caves were appropriated from Buddhist to Hindu, and it is also apparent that some of the Hindu cave plans were inspired by Buddhist caves from around the region. There are several minor caves atop the hills, including the Ganesh Leni and the Jogeshwari, some of which used to house beautiful paintings, now in complete ruin. The sheer size of the site, with its extensive network of caves and the sophisticated techniques used in their creation, make Ellora an unparalleled historical and cultural landmark.

Before diving into the chapterization of this book, it would be prudent to give a brief introduction to the history of rock-cut cave architecture in India, and how and when it all began. The Mauryan dynasty excavated the earliest rockcut temples in the north in Bihar, in the Barabar and Nagarjuni Hills, around 250 bce. An inscription in the Barabar Hills attributes the authorship of these caves to King Dasharatha (r. 232–24 bce), the grandson of Emperor Ashoka (r. 272–32 bce). In succeeding centuries, cave architecture spread in different directions:

Deepanjana Klein

Ellora is one of the greatest sites of rock-cut cave architecture in the world. An architectural and engineering marvel enriched with some of the most beautiful sculptures in India, it is the only such place in the world that celebrates three coexisting major religions: Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism. There are numerous Hindu caves at Ellora excavated over a period of 400 years (sixth to ninth centuries ce), 17 of which are numbered sequentially (Caves 13 through 29) from south to north. This chapter will focus on five of these caves for their beauty, the myths represented in their sculptures, and the power and prestige showcased by their patron dynasties.

Before delving into each of these five caves, it would be prudent to situate Ellora historically among the other Hindu rock-cut cave sites in Maharashtra.1 There are ten significant Hindu sites in Maharashtra ranging from the late fifth to the late eighth century ce, in present-day Kharosa, Takli Dhokeshwar, Mumbai, Ellora, Aurangabad, Mahur, Bhokardan, Ghatnandra, Dharashiv, and Pune. The dynasties active in these Hindu excavations were the Vakatakas, Kalachuris, Chalukyas, and the Rashtrakutas. Power in the upper Deccan became centralized with the Vakataka dynasty in the last quarter of the fifth century. After the fall of the Vakatakas, the Kalachuris became the most prominent ruling power in the region, superseded by the Rashtrakutas of Malkhed in central India. In the sixth century ce, by the time the Chalukyas came into power, the Deccan had been a relatively coherent political and cultural unit for several centuries. The Chalukya and Rashtrakuta dynasties became the chief royal patrons in the Deccan for four centuries, starting from the second half of the sixth century.

The earliest known Hindu cave site in the Maharashtra region is in Kharosa, inaugurated by the Vakatakas in the last quarter of the fifth century ce. The majority of the sculptures at this site are Vaishnavite and are similar to the sculptures from Ramgarh and Udayagiri (near Vidisha in Madhya Pradesh, the capital of the Gupta empire). They are considered to be the earliest Hindu caves attributed to the Gupta

Kailash, Cave 16

; Kailash, Cave 16, north courtyard

Nicolas Morrissey

The Buddhist cave excavations at Ellora, dating from the late sixth to the eighth centuries ce, reflect the apogee of over a millennium of Buddhist rock-cut architectural and sculptural development in the Western Deccan region of the Indian subcontinent. As such, these cave-sanctuaries at Ellora exhibit significant continuities with the preceding heritage of Buddhist rock-cut monasteries across the Deccan, yet also a myriad of innovative features.1 Certainly many of these latter elements at Ellora can be attributed to the complex religious milieu of the early centuries of the medieval period, which—though still rather imprecisely understood—witnessed both the maturation of Mahayana Buddhism and the early emergence of esoteric and/or Vajrayana practices. These developments engendered widespread shifts in Buddhist ritual and devotionalism, philosophical discourse, as well as more broadly, the identity and social roles of Buddhist monastic communities.

Ellora’s development was, however, not only circumscribed by this axial period of religious change, but also by the backdrop of a social, economic, and political environment marked by sustained upheaval and uncertainty. This rather fraught transition to the early medieval period in the Deccan was instigated by the dissolution of the “Gupta-Vakataka” polity in the late fifth century ce, which persisted until the stability of the Rashtrakuta empire’s consolidation in the mid-eighth century ce. Although the Buddhist monastic complex at Ellora appears to have expanded incrementally during these centuries, it is apparent that even from its earliest phases the site was intended to serve a substantial monastic population. From the cavernous devotional center of the monastery, chaitya (prayer hall) of Cave 10 [fig. 2.1], and the expansive assembly hall of Cave 5 [fig. 2.2]—the largest cave of this type ever to be excavated in the Western Deccan (see Chapter 5, pp. 208–209)—to the imposing multistoried ritual and residential halls of Cave 11 and 12 [fig. 2.3], there was clearly no deficit of communal, congregational space for Ellora’s monastic community. The undeniable extent of this physical infrastructure, however, raises important questions about how such a substantial monastery would have been supported

of entrance

above

(see p. 248, above & p. 249, above)

below

facing page above

Lisa N. Owen

The Jain caves at Ellora are among the most impressive examples of rock-cut architecture found on the subcontinent. They are noteworthy for their variety in form and scale, their beauty in carving, and their expansive sculpted and painted programs. These programs feature Jinas (a series of twenty-four omniscient and liberated teachers) and Jain deities (particularly associated with health, wealth, and abundance). They are carved and painted within every cave. The rigid seated and standing postures of the meditating Jinas contrast with the relaxed poses of deities who seem to be enjoying the various objects they hold—including branches of foliage, round fruits, long-stemmed flowers, strands of jewels, and/or bags of coins. The Jain figure Bahubali is also found throughout the caves and is presented in a “bodyabandonment” posture, with vines wrapped around his limbs and deer resting at his feet [fig. 3.1]. While these elements clearly illustrate the long duration of Bahubali’s forest meditation, they also contribute to the overall aesthetic of Ellora’s Jain caves, which is simultaneously “world-renouncing” and “world-celebrating.”

Wondrous worlds surrounding the Jina and Jain deities are further defined through the complex’s numerous flying figures [figs 3.2a–b], vegetal and floral motifs, and richly ornamented architectural elements. For example, cave ceilings are carved with colossal, open lotuses with unfurling petals that seem to defy the weight of their rock matrix [fig. 3.3]. Pillar shafts are multifaceted and carved with pearl festoons and lozenge-shaped gems or diamonds, indicative of the earth’s treasures. A common motif found in the caves is the purnaghata (vase-of-plenty), with foliage overflowing the brim of the vessel to connote unending abundance. These elements clearly add to the sumptuousness of these spaces and create the appropriate environment for representations of enlightened and liberated beings.

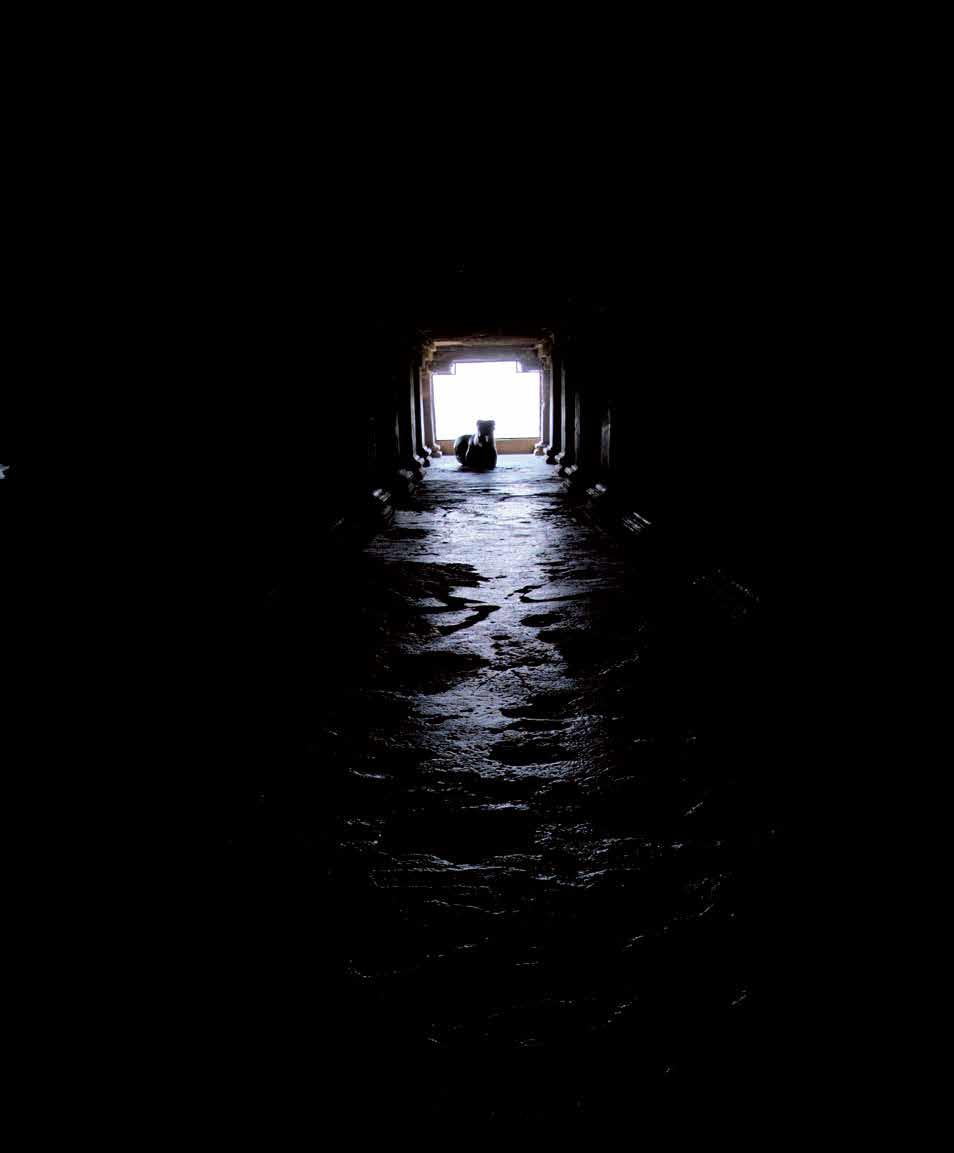

The multistoried layout of the caves—with stairways and passages leading from dimlylit lower stories to large, upper-story halls, filled with light—create a physical sensation of wonder. Even if the exterior of a cave slightly replicates a structural temple through

Indra Sabha, Cave 32 (see p. 261)

The veranda pillars in this upper-story Jain cave [fig. 3.9] are important to us as they are a pillar type that was commonly carved across the site in the late sixth through seventh century ce. In fact, they are found in one of Ellora’s earliest and largest caves, Cave 29 [fig. 3.10]. Slight modifications to this pillar type can be seen in other late sixth-century Shaiva caves at Ellora, including Caves 17, 19, 20, and 26, and in the early seventh-century Buddhist Caves 2 and 5. In general, modifications include a narrowing of the pillar shaft, a reduction of the bulbous shape of the cushion capital, and the addition of carved gana s (dwarf attendants). The inclusion of gana s and carved brackets on the Jain veranda pillars suggests a seventh-century date. Importantly, they differ greatly from the purnaghata pillar type [fig. 3.11] found in the majority of the Jain caves which are commonly cited as evidence for a ninth-century date for all Jain activity at Ellora.6

Rather than the ninth century ce, I posit that work on the Jain caves began in the seventh century and that the upper-story veranda and the three Jina reliefs demarcated this nucleus of rock for Jain artistic activities. The three Jinas functioned as visual placeholders, protecting, marking, and announcing the developing Jain presence at the site. They were created at the same time that select Shaiva and Buddhist caves were being carved. Seen through a larger lens of Jain rock-cut architecture across the Deccan, this would place initial Jain activity at Ellora closer in date with the carving of Jain caves at the multireligious sites of Badami and Aihole.

In the early eighth century, with teams of artists working on the site’s multistoried caves (Caves 11, 12, and 15),7 work on the Jain monuments remained somewhat limited. The natural rock scaffolding supporting the artists who had carved the three Jina reliefs in the seventh century had to be removed so that the facade and hall of this cave could be created. The facade of Cave 33 is quite simple; it comprises a rectangular opening without any roof overhang, canopy, porch, or additional sculpture. The aesthetic of its plain surfaces and massive rectangular pillars correlates well with the site’s early eighth-century, multistoried caves. In addition, the rear wall of this Jain cave is carved with two small rooms, which may have been used for storage, housing loose sculpture and/or ritual implements, or perhaps as residential cells. This particular feature is not replicated in other Jain excavations at Ellora but is included in some of the site’s Buddhist caves. Small cells are also carved in the rear wall of the lower level of Cave 15.

While this work was being conducted, I posit that a team of artists also began penetrating rock located less than 40 meters east of Cave 33. This matrix would form

the gateway and complex of caves known as the Indra Sabha [fig. 3.12]. During this period, only the gateway and perimeter were blocked out. Nonetheless, the limited work here established the outer dimensions of this complex which would later serve as a main hub for Jain devotional activities. Artists then shifted their attention to the two extraordinary monolithic temples at the site.

The Chhota Kailash [fig. 3.13] is located approximately 200 meters southeast of the other Jain monuments. As work had already begun on the Jagannatha and Indra Sabha complexes, artists needed a large, unadulterated exposure of basalt to create this monolithic temple. The initial choice of rock was a good one, as it allowed for a replication of Kailash’s (Cave 16’s) architectural components, its layout, and even directional orientation. However, as Dehejia and Rockwell point out, this formation of basalt was of poorer quality and revealed many lines of breakage during the excavation process.8 This of course caused artists to abandon many parts of this Jain complex, including finishing the rock-cut gateway and leveling the courtyard floor.

Vidya Dehejia

It is likely to come as a surprise to many to hear that the rock-cut site of Ellora, renowned for the grandeur of its richly sculpted monuments dedicated variously to the Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain faiths, carries a considerable degree of “unfinished” work. What exactly do we mean in this context by “finish” or the lack thereof? Finish implies firstly that none of the component parts of a monument are lacking or deficient. A finished monument is thus one which has all of its requisite parts—gateways, halls, porches, shrine, roofs, towers—and which depicts carved imagery appropriate to its dedication to one or other deity. Finish also implies that the various portions of a monument, and all its accompanying decorative and figural carvings, are crafted to a state of refinement so that nothing rough or inadequate remains. Recurring instances of lack of finish in both these senses are evident at Ellora, and they occur across the site and in caves dedicated to all three faiths. There is, for instance, a cave in which rock-cutters have not yet reached the stage of creating uniformly vertical walls or flat horizontal ceilings, but in which sculpted images have already been commenced. There are caves that are usable, but which reveal major areas of unfinished sculptural and architectural work. And there are caves that are almost complete but lack the element of refinement and finish in several details.

Why should “unfinished” work matter to us or be important in any way? Firstly, the substantial body of unfinished monuments at Ellora, and elsewhere in India, demands that we reassess pre-modern India’s attitude towards “finish.” The modern eye is so focused on finished work, especially in the case of the richly decorated monuments of India, that we tend to easily overlook the lack of finish. More often than not, such unfinished work may not be attributed to geological reasons such as bad strata of rock, or the sudden appearance of an underground spring of water, nor entirely to external factors such as natural disasters, wars, the death of a monarch, or bankruptcy of a patron. It would appear rather that we need to come to terms with the fact that pre-modern India had a remarkably flexible and pragmatic approach towards the concept of finish.

previous pages

Entrance facade; Cave 30 a facing page Shiva destroying Andhaka (detail); Dhumar Lena, Cave 29, west entrance (see p. 179)

Pia Brancaccio

The Ellora caves, situated on the western edge of the Sahyadri hills in the Aurangabad district, were established by multiple religious communities (Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain) and served as a fertile site of artistic exchange throughout their development. The present chapter aims to elucidate the relationships between Ellora and other cave sites in the region of Maharashtra active within the same chronological horizon. The goal is to situate Ellora within a broader religious landscape of rock-cut architecture, and to better understand the dynamics of growth at the site.

Unlike most of the Buddhist cave sites from the region, Ellora does not have an identifiable early foundation dating to the beginning of the common era. Walter Spink proposes that the earliest units at Ellora may be small caves clustered above Cave 29, also known as the Ganesh Leni group, situated upstream from the waterfall [figs 5.1 and 5.2].1 Ellora truly blossomed in the early sixth century as a center dedicated to the cult of Shiva, at the same time when the Great Cave at Elephanta and the caves of Mandapeshwar and Jogeshwari were carved in the Konkan. The major undertaking of Ellora Cave 29, also known as Dhumar Lena, an unfinished unit of monumental proportions that extends over the waterfall edge, marks the first important intervention at the site during the early Kalachuri period in the sixth century. 2 There was great activity at Ellora at this time, as confirmed by the finding of an early Kalachuri copper coin in front of Cave 21. 3

When the early Kalachuri rulers were in the region, there were simultaneous activities at the nearby Buddhist site of Aurangabad (Caves 2, 5, 7, and 8). This small cave complex, situated about 30 km away from Ellora, was probably established at the end of the first century ce but witnessed its larger phase of expansion precisely at the time when Ellora was developing its ambitious Shaiva cave excavations. Some of the architectural features we see at Ellora, along with a trend in image monumentality, were also implemented at Aurangabad. In a few instances described below, one can observe how the very capable sculptors active at Ellora and further west in coastal previous pages

Entrance facade; Rameshwar, Cave 21 (see p. 254)

facing page Dwarapala; Dhumar Lena, Cave 29

figs 5.1 and 5.2

Ganesh Leni

Konkan may have also been responsible for the Buddhist sculptures at Aurangabad. Ellora and the Konkan caves also remained connected through the centuries: the Buddhist caves at Kanheri in the Thane district completed in the Rashtrakuta period (ninth century ce) share important features with the Buddhist cluster of Ellora caves. Most relevant is the case of Cave 12 in Kanheri and Cave 5 in Ellora, which are the only large rock-cut Buddhist meeting halls in the Western Deccan, as discussed later in this chapter.

At the turn of the sixth century ce, after the fall of the Vakataka power and its regional feudatories, the early Kalachuri rulers fought for supremacy in the Konkan and inner areas of Maharashtra. In their copper plate inscriptions—the Abhona and Vadner plates—they openly declared their Shaiva–Pashupata faith.4 The new rulers seeking legitimacy and power ended up supporting Shaiva religious groups that better accommodated the values of the belligerent elites. 5 This led to the patronage of many Shaiva cave temples, and to some extent, to the weakening of Buddhist patronage in the region. This also caused a change of trajectory within Buddhist art, where the

Deepanjana Klein

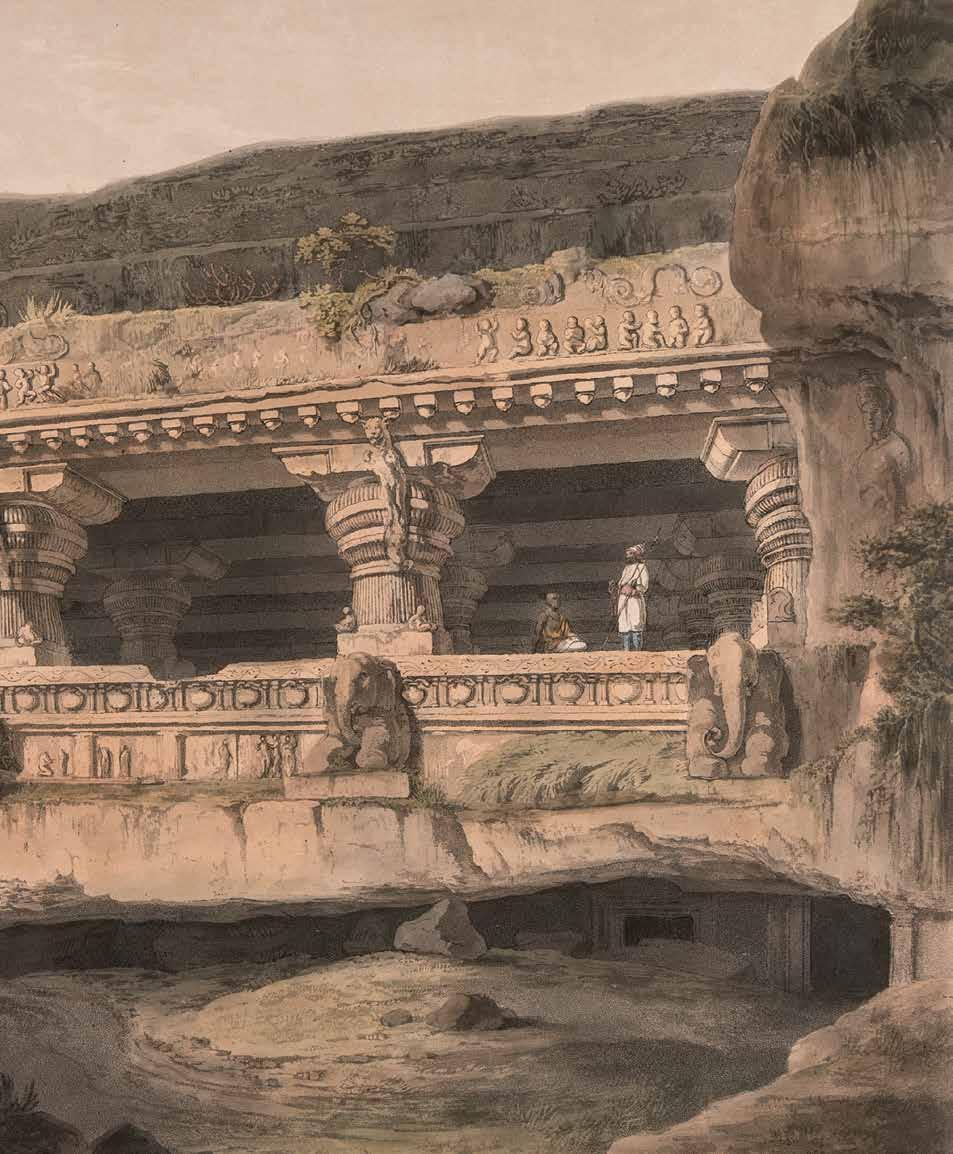

T he study of Ellora would be incomplete without examining the rich 19th-century archival material that documents the site’s encounter with colonial scholarship and artistic documentation. These visual records—from Thomas Daniell’s hand-colored aquatints based on James Wales’s drawings to Raja Lala Deen Dayal’s and Henry Cousens’s pioneering photographs and M.F. Pithawalla’s detailed watercolors—serve as invaluable records that capture the caves at a critical moment in their modern history, before systematic conservation efforts, tourism infrastructure, and environmental changes fundamentally altered both the monuments and their surrounding landscape. The chronological progression of these documentation efforts reveals evolving approaches to recording India’s architectural heritage.

James Wales (1747–1795), a Scottish artist who had moved from Aberdeen to London before arriving in India in 1791, made drawings and paintings of both the Elephanta and Ellora Caves while documenting the Maratha Empire. After Wales’s death in 1795, his drawings passed to Sir Charles Warre Malet, who had married Wales’s daughter Susanna and subsequently commissioned Thomas Daniell to engrave and publish them as the acclaimed 1803 work Hindoo Excavations in the Mountain of Ellora

Thomas Daniell (1749–1840), an English landscape painter who had spent seven years in India, created 24 hand-colored aquatints based on Wales’s field drawings that formed part of his monumental Oriental Scenery series published between 1795 and 1808.

The Ellora plates were marked June 1, 1803, and published between 1803 and 1804, with the accompanying text published June 1, 1804. These images remain among the most significant early visual records of Ellora.

Raja Lala Deen Dayal (1844–1905) was trained as a draftsman at Thomason College of Civil Engineering before becoming India’s first internationally renowned photographer. His career spanned diverse photographic categories, including documentation of India’s great temples and monuments. Deen Dayal’s photographs from the 1880s provide perhaps the most objective documentation of Ellora’s condition in the late 19th century, showing architectural details, sculptural elements, and the site’s relationship to its landscape before significant restoration work began. His systematic

approach offers crucial evidence for understanding the monuments’ historical state and assessing the impact of time and human intervention. For example, in several of the photographs by Deen Dayal and other photographers, vestiges of the original plaster highlighting eyes and ribs are still visible.

Henry Cousens (1854–1933), a Scottish archaeologist and photographer, pioneered the study of monuments and antiquities in British India, particularly in present-day western India and southern Pakistan. The importance of comprehensive visual documentation of India’s archaeological sites was being recognized by a few trailblazing individuals by the end of the 19th century, and Cousens was most notable among them. Joining the Western Division of the Archaeological Survey of India in 1881, he was promoted to Superintendent in 1891 and served for nearly two decades.

Leading a team of artists and draftsmen, he traveled to remote sites, meticulously documenting caves, temples, and monuments through photographs, measurements, and sketches. His work provided some of the earliest systematic documentation of historic sites in these regions. In collaboration with James Burgess, Cousens produced a series of influential publications that remain cited today.

M.F. Pithawalla (1872–1937), who would later become an important painter of the Bombay school, created watercolors of Ellora during his

visits to the site in the 1880s as a young artist. Working during his formative years before establishing himself as a renowned portrait painter, Pithawalla’s watercolors contribute a different perspective—that of an Indian artist operating within both indigenous and colonial artistic traditions, potentially offering insights into how local artists viewed and represented their own cultural heritage during the colonial period.

These 19th-century archival materials from Ellora collectively offer invaluable insights into both the monuments themselves and the colonial gaze that documented them. The images reveal details now lost to weathering, vandalism, or well-intentioned but transformative restoration work, showing us sculptures with intact surfaces, painted details that have since faded, and architectural elements before modern stabilization efforts. By comparing these historical records with the site’s current condition, scholars can trace patterns of deterioration, assess the impact of conservation interventions, and make informed decisions about future preservation strategies. More importantly, these records illuminate how the colonial encounter fundamentally shaped our conception of India’s artistic heritage. Collectively, these archival materials reveal not merely the physical evolution of Ellora, but the layered history of how different cultures have perceived, interpreted, and valued these extraordinary monuments across time.

Dr. Deepanjana Klein

Deepanjana Klein, PhD, is the Special Advisor to the Chairperson, and the Director of Acquisitions and Development, at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi. She has been documenting the Ellora cave temples since 1993. After conducting doctoral research on Ellora, she was awarded the Mellon Foundation grant to create the first comprehensive photo documentation of the site with her husband, Arno Klein, and in conjunction with Dr. Walter Spink, then Professor Emeritus of the University of Michigan. They have contributed more than 3,000 images of Ellora to the Artstor Digital Library.

Dr. Nicolas Morrissey

Nicolas Morrissey, PhD, is Assistant Professor of Asian Art and Religion in the University of Georgia’s Lamar Dodd School of Art. A specialist in the archaeology, epigraphy, architecture, and art history of India, Dr. Morrissey’s recent publications include Silence, Secrecy and Enigmatic Meaning in Esoteric Buddhist Art and A Note on Some Neglected Records from Pitalkhora in the Western Deccan.

Dr. Lisa Owen

Lisa N. Owen, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the University of North Texas. Dr. Owen’s research focuses on ancient and medieval rock-cut monuments in India and her interests also include the production of imagery in ancient India, patterns of patronage, and constructions of identity. Her publications include Carving Devotion in the Jain Caves at Ellora (Brill, 2012) and essays in Marg, Artibus Asiae, the International Journal of Jaina Studies, and the Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies.

Dr. Vidya Dehejia

Vidya Dehejia, PhD, is the Barbara Stoler Miller Professor Emerita of Indian and South Asian Art at Columbia University. Dr. Dehejia is also former Chief Curator of South and Southeast Asian art at the Freer and Sackler Galleries, Smithsonian Institution. With her background in classical Sanskrit and Tamil and knowledge of a range of modern Indian languages, Dr. Dehejia’s writings have incorporated translations of ancient poetry, and material from unpublished manuscripts in order to illuminate an artistic milieu.

Dr. Pia Brancaccio

Pia Brancaccio, PhD, is Professor of South Asian Art and Archaeology at the Università di Napoli 'L'Orientale', Italy. Her research focuses on early Buddhist art and cross-cultural exchange in South Asia, with particular emphasis on the visual cultures of ancient Gandhara and the Deccan Plateau. Her scholarship is published internationally; she serves on the editorial boards of academic journals in Europe and Asia and is regularly invited to speak and collaborate with institutions around the world.

Dr. Arno Klein

Arno Klein, PhD, is the Director of Innovative Technologies at the Child Mind Institute in New York City. Dr. Klein has held positions at Columbia University, Stony Brook University, Sage Bionetworks, and the Parsons Institute for Information Mapping. He first visited Ellora in 1992 with Professor Walter Spink and has since taken almost 10,000 photographs of the site to create a comprehensive photo documentation on the elloracaves.org website.

First published in 2026 by Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd

706 Kaivanna, Panchvati, Ellisbridge, Ahmedabad 380006 INDIA

T: +91 79 40 228 228

E: mapin@mapinpub.com www.mapinpub.com

Text © Authors

Photographs © Arno Klein unless otherwise stated.

Plans on the tracing insert between pages 34–35, 44–45, 68–69, 106–107, 108–109, 136–137 and 138–139 based on Ellora: Sanctuaires bouddhiques, hindous et jaïns (2020), published by 5 Continents Editions, Milan.

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The moral rights of Deepanjana Klein, Stanislaw J. Czuma, Nicolas Morrissey, Lisa N. Owen, Vidya Dehejia and Pia Brancaccio as authors of this work are asserted.

ISBN: 978-93-85360-80-0

Copyediting and Proofreading: Ashwati Franklin / Mapin Editorial Editorial Management: Neha Manke / Mapin Editorial Design: Gopal Limbad / Mapin Design Studio Production: Mapin Design Studio

Printed in India at Archana Advertising Private Limited.

For additional information visit elloracaves.org

Captions

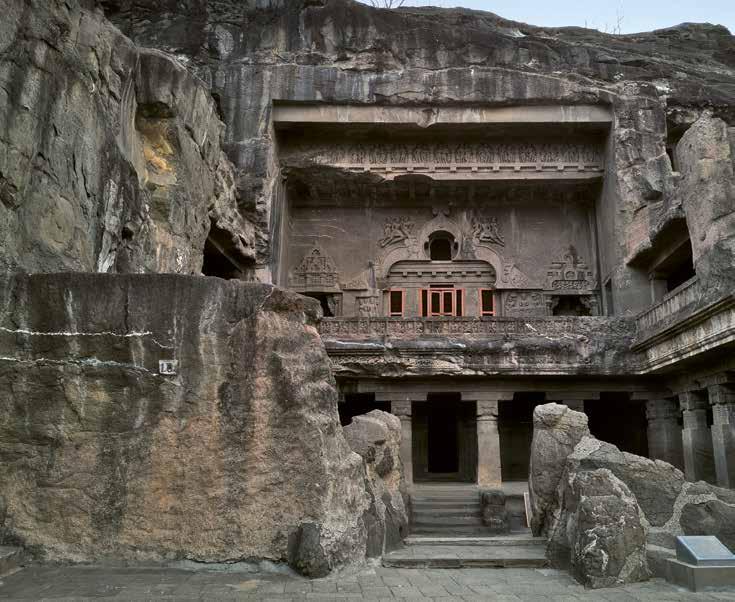

front-cover

Linga shrine (detail); Dhumar Lena, Cave 29 (See fig. 4.7)

page 1

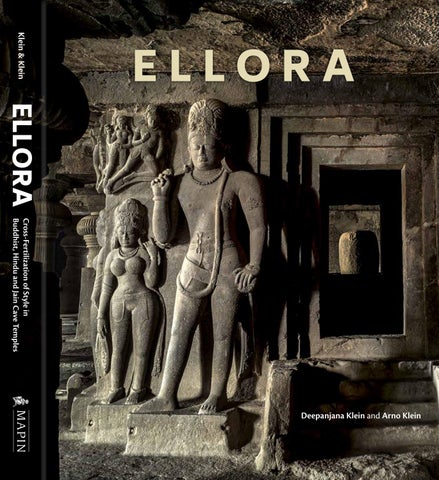

River goddess Ganga; Rameshwar, Cave 21 (See fig. 1.3)

pages 2–3

Seated Buddhas; Tin Thal, Cave 12 (See fig. 2.4)

I first visited the Ellora caves with Professor Walter Spink in 1993. He taught me to observe without restraint, to question relentlessly, and to pursue knowledge with passionate commitment. His mentorship was the seed from which this entire journey sprouted, much like his own half-century dedication to Ajanta’s intricate stories. These caves became more than a research subject for me—they became a home, with each visit revealing deeper layers of understanding and belonging. Dr. Adam Hardy and Dr. Deepak Kannal, as supervisors of my PhD thesis on Brahmanical cave architecture, encouraged me to think independently and explore Ellora as a topic of immense complexity.

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Ajit and Dipali Danda, Arnold and Karen Klein, to my daughter Ellora, who embodies the site’s timeless spirit, and to my co-editor and husband Arno Klein, whose photographs capture the essence of Ellora. A special thanks to my colleague and art historian Tristan Bruck, for his diligent verification of the photo documentation. I will forever be indebted to Sonia and Sid for making the impossible happen for us at Ellora, and to Kiran Nadar, Sunil Hirani, and Dipti Mathur, who believed unconditionally. This work is a love letter—to scholarship, to persistence, to the extraordinary stories embedded in stone.

My gratitude extends across continents and communities: to the contributing authors for their hard work and patience with this project; Bipin Shah and the Mapin team, who transformed research into a beautiful book; Ghiora Aharoni for his helpful feedback on the layout; the Mellon Foundation and the Blanca and Sunil Hirani Foundation for their generous support; and to Navina Najat Haidar, Ashish Anand and my colleagues at KNMA for their invaluable assistance. I am immensely grateful to my local friends at Ellora—especially Yunus, Pathan, and Zuber—who opened impossible doors at the site, sharing not just access but also hospitality, late-night Sufi music, and home-cooked meals that nourished both body and spirit. I have always felt welcome by the staff at the Ellora Caves, the officers of the Archaeological Survey of India, and by Mr. and Mrs. Shah and their staff at Kailash Hotel.

This book arose from an entire community’s collective love for the site and would not have been possible without an entire village coming together.

–Deepanjana Klein

pages 4–5

Jagannatha Sabha, Cave 33, upper hall ceiling (See pp. 266–267)

pages 6–7

North court; Kailash Temple, Cave 16 (See p. 252)

page 268

Thick plaster application on a Bodhisattva; Cave 15, second floor

pages 276–277

Linga in the garbhagriha; Dhumar Lena, Cave 29 (See pp. 176–177)

page 279

Columns; Cave 15, second floor

back cover

Buddha number 5; Cave 2 (See fig. 4.5)

Ellora

Cross-Fertilization of Style in Buddhist, Hindu and Jain Cave Temples

Deepanjana Klein and Arno Klein

Foreword by Naman P. Ahuja • Contributions by Stanislaw J. Czuma, Nicolas Morrissey, Lisa N. Owen, Vidya Dehejia and Pia Brancaccio

280 pages with 7 tracing pages, 203 photographs, 29 illustrations, 22 drawings and a map

9.5 x 11.5” (241 x 292 mm), hc-plc

ISBN: 978-93-85360-80-0

₹4950 | $70 | £50 Feb. 2026 | World Rights

This book attempts to capture the essence of the Ellora cave temples, a UNESCO World Heritage Site excavated between 600 and 1000 ce, and the only cave temple site that houses Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain caves. The contributing authors investigate the temples by religion and myth, patronage and support, stylistic influence and exchange, chronology, and the process of carving and completion of these rock-cut temples.

Ellora also includes extensive photographic documentation, ground plans, and rarely seen 19th-century archival materials.

With 203 photographs, 29 illustrations, 22 drawings and a map.

Deepanjana Klein, PhD, is the Special Advisor to the Chairperson, and the Director of Acquisitions and Development, at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi.

Naman P. Ahuja, PhD, is Professor of Indian art history at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, and the General Editor of Marg

Stanislaw Czuma, PhD, is the George P. Bickford Curator Emeritus of Indian and Southeast Asian Art at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Nicolas Morrissey, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Asian Art and Religion at the University of Georgia’s Lamar Dodd School of Art.

Lisa N. Owen, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the University of North Texas.

Vidya Dehejia, PhD, is the Barbara Stoler Miller Professor Emerita of Indian and South Asian Art at Columbia University.

Pia Brancaccio, PhD, is Professor of South Asian Art and Archaeology at the Università di Napoli ‘L’Orientale’, Italy.

Arno Klein, PhD, is the Director of Innovative Technologies at the Child Mind Institute in New York City.

www.mapinpub.com

www.mapinpub.com