Rise up … women Deeds OR Words: Who was responsible in securing Women’s Suffrage?

A Woman’s Voice

Was Maggie Thatcher a feminist? A deep dive into what it means to be a woman working under the ‘Iron Lady’.

I’m Not a feminist... but Feminism with no filter, no limits, and no one left out.

Am I still a woman? Fighting sexism in real time.

With special introductions to the women’s protests in Mexico.

Introduction

Editor’s

First

Second

Third

Fourth

Editor’s Note

It is widely accepted that women throughout history have been repressed and believed to be inferior in status to their male counterparts. As far back as Classical Athens, constant attempts have been made by those in power to exclude women from politics, the world of work and even public life.

Unfortunately, despite significant progress in the advancement of women’s rights, there are still attempts to repress women today. In Afghanistan today, the Taliban continue to discriminate against women and girls and the country has actually seen a decline in the rights of women with females having now been banned from going to school or work, showing their skin in public, political involvement and leaving the house without being chaperoned by a male.

The situation has become so dire that women can no longer access healthcare if it is to be delivered by a man, this means healthcare is almost inaccessible to women entirely, with women being forbidden from work. As a result of the continuing difficulties women face in accessing their human rights to this day, feminism continues to be a prominent topic and that is why we have decided to produce this magazine.

We aim to draw attention to the impact feminism has had from the late nineteenth century until the present day and how successful it has been in advancing women’s rights in an attempt to emphasise how significantly feminism can still be used today.

We are a group of undergraduate students studying in Manchester and feel passionately about the importance of women’s voices being heard, throughout time and not just in the present day, which is why we decided to address all four waves of feminism, rather than only focus on particular issues. The magazine has been compromised by articles written by a range of different voices from different disciplines: history, politics, philosophy and English. This means together, we can be more comprehensive and interdisciplinary in our beliefs.

As your editor in chief, I strive to ensure that women’s voices are heard. Thank you, Millie Barratt.

Meet The Team

Amina: Picture/media editor.

I'm currently studying English, and a certified yapper. When I'm not buried in a novel or chatting away, I'm teaching secondary school kids- which is chaotic but fun. And when I finally get some free time, I'm probably out with friends, laughing too loud over coffee or food.

Abbie: Graphics editor.

Hi I’m Abbie, I’m a philosophy student with a passion for women’s rights. I enjoy learning about world issues and how support and solidarity can come from all corners.

Millie: Editor-in-chief.

A passionate feminist studying history with a particular love of all things Ancient Greece and Rome! I spend most of my spare time on holiday or booking holidays and aim to see as much of the world as I can. Usually found with either a coffee or a cocktail in hand.

Natalie: Managing editor.

I’m a philosophy student with a passion for ethical and religious studies. When I’m not studying I enjoy spending time with my cat, Amy, and playing games.

Cathrine: Copy editor.

I am a professional over-thinker, and full-time lover of philosophy! I thrive on curiosity, caffeine, and the occasional impulse decision. When I’m not studying for my degree in philosophy, religion and ethics, I’m probably travelling or spending time with friends.

James: Editor.

I am a writer passionate about history, politics, and social issues. My work highlights the struggles and resilience of women in their fight for equality. In this issue, I explore life as a woman in Thatcher’s Britain, reflecting on the challenges faced during a trans-formative era.

Overview

From the marches of the Suffragettes and Suffragists, to the digital protests of the #MeToo movement, women have always fought tooth and nail for the basic rights that men have kept to themselves. This magazine follows the waves of feminism throughout history, and how the whisper of freedom became a tangible reality for many women across the globe.

We begin with the first wave, where women’s strength was evident throughout the First World War stepped into roles traditionally held by men. Through the works of the Suffragettes, Suffragists, and many women who were never given the limelight, they fought for - and won - the rights for some women, laying the ground for change.

The second wave takes us into the 1960s and beyond, with more marches, strikes, and consciousness-raising. While election of Margaret Thatcher as the Prime Minister of the UK is often cited as a milestone for women in power, many feminists critiqued her leadership. Thatcher broke political ground, but largely ignored women’s rights and openly rejected the label of feminist.

The third wave introduces us to the concept of intersectionality - recognising that many women are not just oppressed because of their gender, but also because of their race and class too. Pop-groups, Riot Grrrl music, and the rise of the Internet led to more awareness and choice within feminism.

The final wave, continuing to this day, reflects the ongoing effort to define what a ‘woman’ is, and highlights how we still need global action for women. Many women around the world are still fighting for their rights in their own lives, and we need to use our voice to help them attain those rights.

01. Rise Up, Women

Deeds

or Words: Who was responsible in securing Women’s Suffrage?

By Millie Barratt

A comparative article addressing the work of both the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, also known as the suffragists, and the Women’s Social and Political Union, the suffragettes in securing the vote for women. This was the primary aim of the first wave of feminism.

As put forth by Emmeline Pankhurst, “first it is [the vote] a symbol, secondly a safeguard, and thirdly an instrument”. (Pankhurst, 1908) This emphasises the importance of women having the most fundamental legal right, the vote, which was the key aim of first wave feminism. Feminists wanted the vote, they wanted it on equal terms with men and they wanted it imminently.

There have been debates over when the campaign for women’s enfranchisement began within Britain, but we can date it back to 1865 when the first Women’s Suffrage Society was formed within our own city of Manchester before the movement then spread to other English cities of London, Birmingham and Bristol. (Oakley, 1982, p.10) Manchester also has further involvement in the development of the movement in that the first public meeting on the topic of women’s suffrage was held here in the Free Trade Hall in April 1868. (Ibid) At this meeting, a resolution was passed that asked for the vote “on the same terms as it is or may be granted to men”. (Ibid) This explicitly shows that the aim of initial feminist activity was to gain women access to voting rights. However, they did not achieve this until half a century later after campaigning efforts of suffragists,

as well as extensive measures having been taken by suffragettes. Not to mention a world war spanning four years of the first wave of feminism in which women demonstrated their ability to work in traditionally male job roles.

The first wave of feminism developed exponentially in 1987 with the formation of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), led by Millicent Fawcett. (Holdsworth, 1988, p.13) Members of this organisation are referred to as the suffragists and they wanted the vote for middle-class, property-owning women and believed they could achieve this through peaceful tactics, non-violent demonstrations, petitions and the lobbying of MPs. Fawcett thought that displays of intelligence, politeness and by abiding the law, the suffragists would prove themselves as responsible enough to participate in politics. Their aims and methods are clearly shown in a political manifesto they published themselves in the early twentieth century.

By 1903, many women had became impatient with the lack of progress from the peaceful methods used by the NUWSS and as a result, Manchester's Emmeline Pankhurst, with the

support of her family, formed the Women’s Social and Political Union. (Ibid) The WSPU was comprised mostly of working-class women rather than just property owners like the suffragists. With a desire to push for faster progress towards emancipation, members of this organisation pushed for “Deeds not Words”, indicating towards their turn to more militant methods. These feminists later became termed as the suffragettes by the Daily Mail in 1906, in an aim to be derogatory towards these women but the term stuck with members of the WSPU. (Gonzales, 2020)

By 1912, the suffragettes had become significantly more militant in their campaigns upon realising that to gain the attention needed to achieve emancipation, they must behave extremely enough to be sent to prison. Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney had been the first suffragettes to be imprisoned in 1905 for interrupting a Liberal Party meeting at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester (Holdsworth, 1988, p.13), advocating for voting rights for women. Pankhurst was arrested after spitting in a police officer’s face and refusing to pay a fine. (Gennard, 2018) After the realisation that imprisonment gathered attention, members of the Women’s Social and Political Union, in particular burned letterboxes and buildings, damaged property by throwing bricks and protested parliament. As a result, many did face imprisonment and subsequently some even faced forced feeding following hunger strikes.

Following the outbreak of World War One in 1914, most women withdrew from suffrage campaigns to support the war effort. (Pugh, 1992) The WSPU also agreed to put their militant activity on hold during the war and the Suffragette Newspaper became Brittanica to advocate their support of the war effort. Instead, feminists channelled this energy into

managing their households while their husbands were on the frontlines, filling job vacancies left by men and the production of munitions needed for the war. Throughout the four years of world war, women showed they could display the responsibility and professionalism needed of them to deserve the vote. Between April 1915 and July 1918, 1,659,000 women were added to the workforce. (Oakley, 1982, p.19) In September 1916, the War Office even claimed that “they had shown themselves capable of replacing the stronger sex in practically every calling”. (Rosen, 1974, p.256)

Following the end of the First World War, the Representation of the People Act was passed which gave all men over the age of 21 the vote. Women over the age of 30 who also were homeowners, or the wife of a local government elector were also given the vote. (Holdsworth, 1988, p.13) Women’s suffrage had been achieved; however, women still did not have equal voting rights to men so the

fight of suffragists and suffragettes alike did not stop there. It cannot be denied that the war played a role in securing votes for women, however the role of the war is significantly less than the role played by the activism of the suffragettes. Asquith, Prime Minister of Britain at the time of the Representation of the People Act, questioned how the vote could “legitimately be witheld from these women who had worked alongside the men during the long years of the war for the nations survival”. (Oakley, 1982, p.10) Arthur Marwick (1977) does argue that men’s participation in the war effort brought into question extending the franchise for men and in turn, attention was drawn to the women who wanted the same. However, the war was not directly and soley responsible for women’s suffrage because, as put forth by Paula Bartley (1998), the women who helped with the war efforttended to be younger than 30 and not homeowners and thus, were still denied the vote.

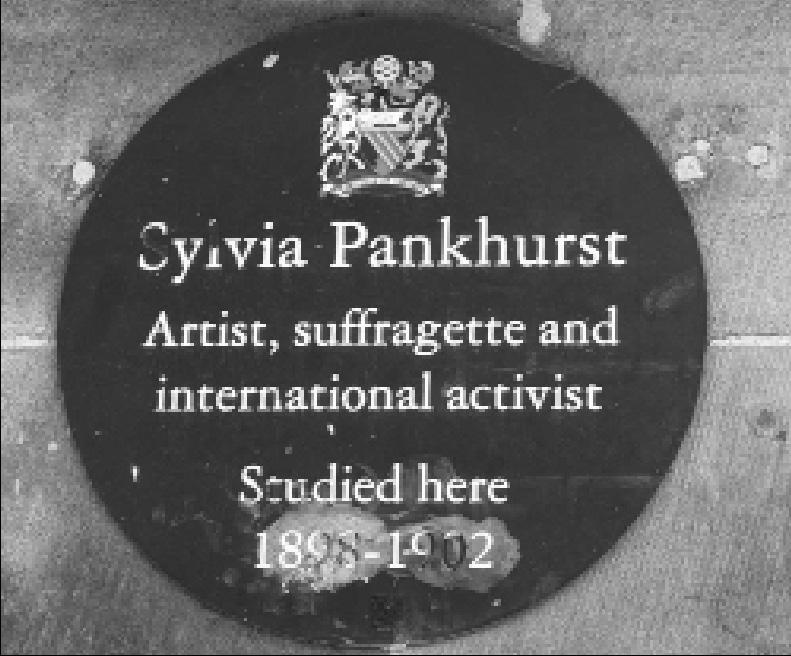

The impact of the suffrage movement has had an extremely significant and longstanding impact on British women. Women today have first wave feminists to thank for fighting for voting rights for us, as well as themselves, especially those who lost their lives to the cause. We can see the lasting work of Emmeline Pankhurst here in Manchester. Her statue, named Rise Up, Women, has stood in St Peter’s Square since 2018 and remains an important destination for protest in the city with it being utilised by a rnage of modern activists. It had been seen holding Ukraine and Palestine flags in recent years. Additionally, the Pankhurst museum is located on Nelson Street where the family formally resided and is the only museum dedicated to telling the story of women’s fight for the vote, aiming to ensure that the legacy of the suffragettes lives on.(Pankhurst Museum, 2025) The Pankhurst Trust also have ongoing work for the women of today under Manchester Women’s Aid in which they help victims of domestic abuse receive confidential help. (Manchester Women’s Aid, 2025)

Furthermore, suffragettes continued campaigning post-war to achieve the vote now on equal terms with men and as a result, the Equal Franchise Act, also known as the “Flapper’s Act”, was passed in 1928 that gave all women over the age of 21 the vote, this finally gave women equal voting rights to their male counterparts. This supports the notion argued by Sue Bruley (1999) that it was in fact pressure from feminists that led to these legislative changes that provided women with increased legal, specifically voting rights. Also, campaign efforts, as well as the efforts throughout the war, of women themselves changed the way that they were perceived in society and ultimately, raised women to a much more equal and respected status. Bruley (1999) argues that this improvement was a direct result of the collaborative efforts of women throughout first wave feminism.

Essentially, the hard work, passion and dedication of the suffragettes endures generations and leaves a particular impact on the city of Manchester, historically known for protest.

Bibliography:

Bartley, P. (1998). Votes for Women, 1860-1928. London: Hodder & Stoughton Educational.

Bruley, S. (1999). Women in Britain since 1900. London: Red Globe Press.

Gennard, D. (2018). The University of Manchester. Available at: https://www.manchester.ac.uk/about/magazine/picture-features/queen-of-the-mob/# :~:text=While%20a%20student%20of%20Law,pay%20a%20five%2Dshil- ling%20f ine.

(Assessed 14 April 2025)

Gonzales, E. (2020). How the Term Suffragette Evolved from Its Sexist Roots. Available at: https://www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/politics/a33633227/suffragette-mean- in g-history/ (Accessed 14 April 2025)

Holdsworth, A. (1988). Out of the Doll’s House: The Story of Women in the Twentieth Century. London: BBC Books.

Manchester Women’s Aid. (2025). Manchester Women’s Aid. Available at: https://www.manchesterwomensaid.org/about (Assessed 14 April 2025)

Marwick, A. (1977). Women at War, 1914-1918. London: Fontana Paperbacks.

Oakley, A. (1982). Subject Women: A powerful analysis of women’s experience in society today. London: Fontana Paperbacks.

Pankhurst, E. 1908. The Importance of the Vote. 24 March, Portman Rooms, London.

Pankhurst Museum. (2025). The Pankhurst Trust. Available at: https://www.pankhurstmuseum.com/learn (Assessed 14 April 2025)

Pugh, M. (1992). Women and the Women’s Movement in Britain, 1914-1959. London: Pal-grave Macmillan.

Rosen, A. (1974). Rise Up Women! The Militant Campaign of the Women’s Social and Political Union 1903-1914. Oxford: Routledge.

02. The War of The Women

By Amina Asghar

The second wave of feminism occurred in 1963-1980. This article will explore the issues of intersectionality, diversity and individual empowerment. It will focus on when Margaret Thatcher became prime minister, the anti war protests in 1990 and the equal rights amend-

ANTI- WAR PROTESTS IN THE UK:

In the 1990’s uk saw significant anti- war protests for example the Greenham common women’s peace camp was a series of protest camps established to protest against nuclear weapons. It lasted nearly two decades. It was set up by a group of women who opposed In September 1981, 36 women chained themselves to the base fence in protest against nuclear weapons. They then began to stay at the camp as that was not enough. The camp became well known on 1st April 1983 when 70,000 protestors formed a 23km human chain from greenham to the ordnance factory.

This ended up on the media and therefore inspired people across Europe to protest and create other peace camps. They used posters and songs to grab people’s attention. The camp therefore became a symbol of feminist and anti- nuclear activism, emphasising women’s roles in peace movements. Another famous movement of theirs was when 50,000 women joined hands around the base in a protest which was known as ‘embrace the base’. These protests contributed to the removal of the cruise missiles in 1991. The greenham common women’s peace camp was a groundbreaking example of grassroots activism, inspiring future movements for environmentalism and women’s. These protests lasted up until 2000.

THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT ACT:

The equal rights amendments act was first introduced in 1923 by Alice Paul and the national women’s party. On September 25, 1921 the national women’s party decided to campaign for the amendment to guarantee women equal rights with men. Alice Paul and her national women’s party asserted that women should be on equal terms with men in all regards. Even if that means sacrificing benefits given to women through protective legislation shorter work hours and no night work or heavy lifting.

World War II began with rise supporters of the ERA. Due to the war, many women had to take on untraditional roles at home and in the workforce. Protectionists were against the ERA because they believed women need to be treated differently than men. Women entered the workforce and proved they could handle working the same jobs as men, including joining the U.S armed forces. Women were supporting their country, despite not being compensated or rejected fairly. With the increased patriotism in the country people began to see the value of women being involved in their country. As the war continued more opportunities for women to work opened up die to fewer men being available. The support for equality grew with this as women continued to prove their ability and willingness to work.

CLEANING TIPS

Lemon juice to remove stains- You can brighten white laundry by adding half a cup of lemon juice to your wash. It doesn’t have to be fresh – bottled juice works just as well. Washing soda crystals instead of detergent- Washing soda crystals may seem very old-fashioned, but as they have no bleach or enzyme. Bicarbonate of soda to scour pans- We all know bicarb is a good fridge deodoriser, but it’s also great for making a scouring paste to clean stains with. Create a paste of half bicarbonate of soda and half water to rub into stains on kitchen worktops, sinks, cookers, and saucepans. Once the stain is removed, rinse thoroughly. You can also add it to bleach to boost its performance in the bathroom.

The Life of Women in Thatcher’s Britain

By James Butler

Following the Conservative victory in the 1979 General Election, Margaret Thatcher (1925 –2013) would become the Prime minister of Britain. As the first female prime minister, Thatcher shattered the political glass ceiling in British Politics. Rising to the top of a heavily male-dominated institution. Regardless of how Thatcher’s policies have been interpreted, her rise to power indicated to the women of Britain and the rest of the world that women were able to reach positions of power and wield influence on a global scale. Feminism is defined as, “the belief that women should be allowed the same rights, power and opportunities as men and be treated in the same way”. The sheer fact that Thatcher was able to become Prime minister is evidence of how successful feminist movements had been in Britain, now that there was a female head of government, it would seem no opportunity was out of reach for British women. However, Women from all different kinds of backgrounds would continue to face old challenges and encounter new ones under Thatcher’s government.

Section 28

Despite Thatcher serving as a role-model to the women of the world, showing that the fight for women’s rights and opportunities had been successful. The Economic and social policies put in place under her conservative government would arguably turn the nation against her. Women in Britain would face several challenges because of Thatcherism (political and economic policies advocated for by Margaret Thatcher). Firstly, it’s vital to acknowledge that under Thatcher’s government lesbian and gay communities faced challenges because of the 1988 Local Governments Act. As a result of this legislation, “The prohibited new clause (New clause 14) would prohibit local authorities from ‘promoting homosexuality by teaching or by publishing materiel’” (House of Commons, 2023). By passing this law, Thatcher’s government not only turned their backs on the Lesbian and Gay population but would add fuel to the fire of discrimination that homosexual people faced in Britain. Newspapers from the time present the law as one that divided Britain and withdrew aspects of freedom from Britain’s homosexual community. ‘Off Our Backs’, the longest surviving feminist newspaper from the United States recounts that, “The Essex County Council has become Britain’s first local government to use the anti-gay Section 28 to bar lesbian and gay Our Backs, 1989). From this controversial legislation came resistance, across the country people came together to stand against Section 28. In 1988 people gathered in Manchester to stand up for their rights and show Thatcher’s government that they would not be silenced out. Signs with Phrases such as ‘defend Lesbians, defend Gays’ and ‘never going underground’ would be presented at the Manchester protests and others across the country. Indicating that despite the challenge they faced, the Lesbian women and Gay men of Britain stood together to oppose discrimination.

Miners Strikes 1980’s

Furthermore, women in Britain would come to experience years of hardship because of Conservative economic policy in the 1980’s. Under Thatcher’s leadership Britain would move away from the coal mining industry and towards imported fuel. As a result of this, mines would be closed across Britain as they had been deemed inefficient. Traditionally, towns were built near these mines, and most men would work all day in them, acting as the breadwinner for their family and covering most expenses through their job as a miner. However, because of the mines being closed, large numbers of people were suddenly made unemployed and were unable to care for their family. With no government planned re-training process in place for workers, many were left jobless and hopeless. The women who were married to these workers also felt betrayed by Thatcher’s government, wondering how their family would be able to survive without the household income they had previously. To send a message to the government, strikes began all over the country opposing the closure of British mines. “Not long into the strike the slogan was invented, ‘close a pit, kill a community’” (Oxford, n.d.). Sayings like this emphasize how important the mines were to the British people; they were the difference between comfort and starvation for many men and women of Britain. Ultimately the fight to keep the mines open failed. “By 1994 only 15 of the 174 pits remained open, and there are now only two mines remaining in the UK” (People’s History Museum, 2024). Men and Women across Britain came to suffer from this legislation, losing money and scrambling to become employed again. Of all the policies that came from Thatcher’s government, it is perhaps this one that is most bitterly remembered and still today dictates many people’s resentment for Margaret Thatcher.

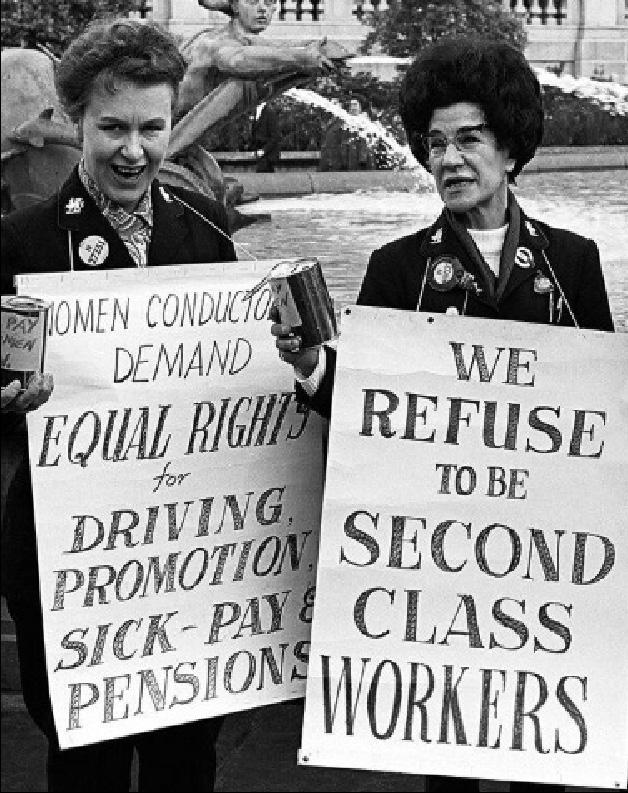

Second class workers / fighting for equal pay Although the years of campaigning for women’s rights had been largely successful, lots of women in Britain still faced great challenges. Most women in Britain faced uneven employment opportunities and discrimination in the workplace. Under Thatcher’s government women would be encouraged to live a traditional life of housework and childcare, however they would come to need their own income more than ever before. As a result of the mines being closed, most women looked for employment so they could make it through these hard times. However, “women were actively steered away from ‘men’s work’ including roles at the local dockyard” (Jenkins 2023). As a result of feeling like ‘second class workers’, women rose up across the country to demand equal employment rights.

Conclusion on the topic

Overall, women in Britain faced many challenges while Thatcher’s conservative government was in power. These mainly being discrimination and uneven opportunities. Despite this, the women of Britain never backed down in their goal to stand up for their rights and express how they felt. The 1970’s and 80’s represents a time where women expressed incredible determination to become equal in society, carrying on the spirit of previous movements such as the Suffragettes, to win the war for equal rights and opportunity.

Bibliography:

Cambridge University Press (n.d.) Feminism. Available at: https://dic-tionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/feminism (Accessed: 14 April 2025).

House of Commons Library (2023) The 20th anniversary of the repeal of section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988. Available at: https:// commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cdp-2023-0213/ (Accessed: 15 April 2025).

Off Our Backs (1989) ‘Britain: Section 28 Fight’, Off Our Backs, 19(5), p. 5. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25796807 (Accessed: 19 April 2025).

University of Oxford. (n.d.). The Miners’ Strike of 1984–5: An oral histo-ry. University of Oxford. Available at: https://www.history.ox.ac.uk/min-ers-strike-1984-5-oral-history#tab-2 838761 (Accessed: 19 April 2025).

People’s History Museum. (2024). Miners’ Strike 1984 to 1985. People’s History Museum. Available at: https://phm.org.uk/blogposts/miners-strike-1984-to-1985/ (Accessed: 19 April 2025).

Jenkins, L. (n.d.). ‘They could, but they weren’t encouraged to’: Class, gender and work in Portsmouth in the 1970s and 1980s. Women’s History Network. Available at: https://womenshistorynetwork.org/they-could-but-they-werent-encou raged-to-class-gender-and-work-in-portsmouth-in-the-1970s-and-198 0s-mandy-wrenn/ (Accessed: 20 April 2025).

03. I’m Not A Feminist ... But By

Cathrine Edwards

“I’m not a feminist, but…” – a phrase you’d hear in the 90s from schoolgirls, wary of being seen as ‘too political’, even if they benefited from feminist wins. It captured a moment in history: feminist ideas were shaping culture (equality in the workplace, for example) and more in the United Kingdom, whilst many were afraid to say the F word out loud (Aune, 2017, p. 8). In response to both the significant benefits and the perceived limitations of first and second-wave feminism, a new generation emerged. Third-wave feminism began, led by young women navigating a media-saturated, culturally complex, and economically diverse world. They inherited legal rights and protections, entering a world where social and economic freedoms were increasingly normalised. But something still felt unfinished (ibid., p.8). Influenced by two pivotal events, the Anita Hill hearings of 1991 and the increase of ‘Riot Grrrl’ groups, this wave sought to define and destigmatize feminism to be more diverse, intersectional, and expressive (Alexander, 2020). This piece dives into how protests, pop icons, and punk bands helped third-wave feminism challenge what feminism looks like.

WHAT WAS THIRD-WAVE FEMINISM?

Third-wave feminism developed in the early 1990s and expanded well into the 2000s, several decades after the 1960s and 70s second-wave feminist movement. It was led by a new group of activists who were mainly young women (Aune, 2017, p.3). Whilst the second-wave was focused on gender roles, this period of feminism sought to expand civil and social equality for all women. These activists took on inequality by using irony and stood up to exclusion through community action, making feminism less authoritarian. Third-wave feminism brought a non-judgmental attitude that allows women to choose for themselves how to negotiate the often contradicting desires for both equality and sexual pleasure (Snyder-Hall, 2010, p.255). Young feminist voices tried to mend the split between porn, sex work and heterosexuality. Instead of having one rule for everyone, they fought for the choice for each woman to decide how to negotiate this contradiction. This led to third-wave feminism also being known as the ‘choice’ feminism: one woman could become a lawyer whilst the other is a pole dancer – third-wave argued they both should be respected. But critics warned that calling everything a ‘choice’ could overlook how those choices are shaped by class, race, and power (ibid., p.256). Third-wave strives to be inclusive of the many choices that women have to make, and stresses that women do not share a common identity (ibid., p.259). It seeks to avoid exclusions based on gender, race or sexuality, and recognises that women in different positions often have very different experiences. The importance of individual experience and awareness came into sharp focus during the Anita Hill hearings of 1991. This is widely seen as the catalyst for third-wave feminism in the US – and later the UK – as it exposed the persistent silencing of women (particularly Black women) women).

POLITICAL AWAKENING – THE ANITA HILL EFFECT AND UK PARALLELS

Anita Hill testified against Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, accusing him of sexually harassing her when she worked for him. She declared that he had repeatedly pursued her to go on dates and made inappropriate comments to her. Despite her testimony, Thomas was still confirmed as a Supreme Court justice after these hearings.

However, Hill’s courage in speaking up prompted many other women to speak out about their own experiences and question the prevailing gender power structures within government (Alexander, 2020). In 1992, the ‘Year of the Woman’, a record 27 women were elected to Congress, which inspired more women to push towards careers in public service (U.S. Senate, n.d.).

“Women who accuse men, particularly powerful men, of harassment are often confronted with the reality of the men’s sense that they are more important than women, as a group” (Hill, 2011, p.141).

The House of Commons Library (2023) showed a jump in 1997 when 120 women were elected as MPs – a number that has continued to grow in subsequent elections. In the early 1990s, the UK saw growing public and media discussion around gender-based harassment, although legal frameworks were somewhat behind the US.

Protests like Hill’s empowered marginalised voices and prompted visible legal reforms. The case underscored the need for reform and laid the groundwork for intersectional third-wave feminism, led by Kimberlé Crenshaw, which emphasised the importance of lived experience and the visibility of women of colour in a feminist discourse.

INTERSECTIONALITY AND INDIVIDUALISM:

Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality highly influenced third-wave feminism, as she advocated for the acknowledgement of every part of your identity – your gender, race and sexuality – as these create unique experiences. Crenshaw highlighted how the first and second-wave feminisms did well to achieve some liberation, but most women of colour still felt excluded from this. Furthermore, this highlights the fact that Black women experience a ‘double discrimination’ due to their race and gender.

Third-wave feminism helped shape a new generation of girls to be more self-aware, empowered, articulate, and high-achieving. The awareness of these ‘barriers’ put in place by their society spurred women to achieve higher, breaking the boundaries that men had put in place to stop them. In the UK, the Southall Black Sisters (SBS) continue to challenge all forms of violence against women and girls, specifically Black communities, helping them gain control of their lives (Jackson, 2023). This awareness of identity not only redefined feminist activism but also began to influence representations of women in pop culture. As feminism was no longer about ‘one-size-fits-all’, pop culture started to reflect this, finding new ways to express themselves and allow previously excluded voices to enter the mainstream conversations.

POP-CULTURE AND THE FEMINIST REBRAND:

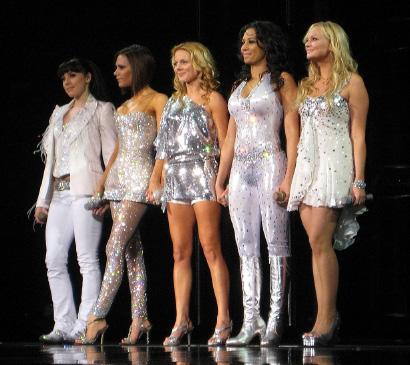

Bands like the Spice Girls and the idea of ladette culture led to the rise of ‘girl power’ in mainstream media, but the most influential of the time were the underground punk activists in ‘Riot Grrrl Groups’. Feminist musicians decided to organise a ‘girl riot’ through their activism, which was dedicated to women’s empowerment. Bands such as Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, and Heavens to Betsy led this wave of punk activism. In the concerts themselves, a group named ‘Women to the front’ provided a safe space for women, which became a larger symbol of the call for women to be brought to the forefront in all areas of life (U.S. Senate, n.d.). By the 1990s, Riot Grrrl bands were so well known that mainstream pop culture started to incorporate some of the movement’s terminology. ‘Girl power’ became a pop culture slogan, where the Spice Girls began promoting a theme of women’s empowerment.

Riot Grrrl groups were angry and intentionally raw. In contrast, the Spice Girls were repackaged as empowerment as glossy pop, catchy and easily digested. Their ‘girl power’ slogan echoed the movement, but stripped it of its politics, turning empowerment into branding. In its time, these Riot Grrrl bands were a prominent representation for women who may not have identified with the concerns or practices of the mainstream ‘cookie cutter’ feminism, and inspired radical global activism for decades to come. Bands like the Spice Girls seemed to promote a sort of ‘lipstick feminism’, where women could wear makeup, love the colour pink, and still be a feminist, flipping the idea that feminism had to be scared of femininity. In contrast to this, ‘Ladette’ culture also became more popular, as young women developed more traditionally masculine behaviours and adopted a more self-confident attitude. This highlights the freedom of movement, whether you are embracing femininity or rejecting it.

CONCLUSION:

As we have seen, ‘I’m not a feminist ... but’ encapsulates the contradictions of the era, as it allowed women to freely choose how to express their identity, through ladette culture and lipstick feminism. This era of feminism seemed to set up fourth-wave feminist ideas, as modern feminist movements continue the third-wave debates around sexuality, identity and choice. Even though the term ‘feminist’ may have connotations with primarily white feminism, many feminist ideas have become normalised. Third-wave feminism opened the door for a more culturally aware and individualist movement. It wasn’t perfect, but it made feminism feel relevant to a new generation. Is today’s feminism simply an evolution of the third-wave, or is it something entirely new?

REFERENCES:

Aune, K, Holyoak, R. (2017) ‘Navigating the Third Wave: Contemporary UK feminist activists and ‘third-wave feminism’, Feminist Theory, pp. 1-32. Available at: https://pure.coventry.ac.uk/ws/portal-files/portal/12570762/navigatingcomb.pdf (Accessed: 22 April 2025).

EUR-Lex. (n.d.) Equal pay for male and female workers. European Union. Available at: https://eur-lex. europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM%3Ac10917a (Accessed: 14 April 2025).

Hill, A. (2011) Speaking Truth to Power: A Memoir. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. House of Commons Library. (2023) Women in Parliament and Government. UK Parliament. Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01250/ (Accessed: 14 April 2025).

Jackson, L. A. et al. (2023) ‘Campaigning against workplace ‘sexual harassment’ in the UK: law, discourse and the news press c. 1975–2005’, Contemporary British History, Vol38, No2, pp.321–350. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13619462.2023.2262930 (Accessed: 22 April 2025).

National Women’s History Museum (2020) Feminism: The Third Wave. Available at: https://www. womenshistory.org/exhibits/feminism-third-wave (Accessed: 22 April 2025).

Snyder-Hall, C.R. (2010) ‘Third-Wave Feminism and the Defense of “Choice”’, Perspectives on Politics, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 255-261. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25698533 (Accessed: 22 April 2025).

U.S. Senate. (n.d) Year of the Woman. United States Senate. Available at: https://www.senate.gov/ artandhistory/history/minute/year_of_the_woman.htm (Accessed: 14 April 2025).

04. Am I still a woman?

In the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2022 decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, the landmark ruling that had protected abortion rights nationwide, a surge of activism has ignited both in the United States and across the globe in support of women’s rights. The reverberations of this decision have not been confined to American borders; they have sparked a wave of solidarity protests worldwide, including in the United Kingdom, highlighting the interconnectedness of women’s rights movements.

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization dismantled nearly 50 years of federal protection for abortion rights, leaving the matter to individual states. This shift has led to a patchwork of laws, with some states enacting stringent bans and others striving to safeguard access. Notably, Florida’s recent appellate court decision declared unconstitutional a law allowing minors to obtain abortions without parental consent, citing infringements on parental rights . Simultaneously, anti-abortion activists have intensified efforts to restrict access to mifepristone, a widely used abortion pill, through campaigns like “Rolling Thunder,” despite scientific consensus on its safety. In response, grassroots organizations such as Rise Up 4 Abortion Rights have mobilized nationwide, organizing protests and walkouts to demand the restoration

By Abbie Billenness

The UK’s Response: A Show of Solidarity

Across the Atlantic, the UK’s response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision has been one of profound solidarity and concern. In June 2022, protests erupted in major cities, including

A Unified Global Movement

I, as a woman, stand with those in America as well as the rest of the world where our rights are stripped away for the sake of others beliefs. Our autonomy replaced with their enforcement of rules and bans that don’t typically even affect those who put such bans in place. We use our voice and the voice of this magazine to outstand and outlast that of the oppressive nature of our enemy. And as the fight for abortion rights continues, the solidarity between nations serves as a reminder that the struggle for women’s autonomy transcends borders. The collective efforts of activists, policymakers, and citizens alike are crucial in ensuring that reproductive rights are not only preserved but strengthened for future generations

“the fight for womens rights is a fight for human rights. It includes reproduc-tive justice, racial justice, LGBTQ+ rights and economic equity”

Mexico and Women's Rights

By Natalie Collinson

Mexico faces many issues of discrimination in the modern day, particularly against women and indigenous people with around 35% of women reporting to have faced physical violence and 50% having experienced sexual violence in their lifetime. The risk to women and their life is still greatly at risk; on average 10 women are killed every day, most because of intentional homicide or femicide (killing a women due to her gender). The cases of femicide has increased from 2015 to 797 cases of femi-cide in 2024. These risks have been the central demand of the feminist movement in Mexico for decades. Cancun’s town hall has been a returning area for feminist protests including strikes, demonstrations and even riots due to clashes with police. In November 2020, ignoring the governors instructions, the police opened fire in an attempt to intimidate and disperse protesters who were against the femicide. Although there were only injuries, the incident highlighted the ongoing repression women still face in the modern day.

Things are being put in place to protect women in Mexico, such as the national development plan and the national gender equality policy (2013-2018) which for the first time mainstreams the aim for gender equality and substantive equality. This means that the government is accountable for and is putting more focus on the impacts laws and policies. However, not enough spending is being put into these actions - in 2015 only 0.5% of public spending went into women’s equality issues.

When I went to Mexico in March 2025, I found myself at the town hall in Cancun witnessing a feminist protest. Their message was clear that not enough is

References:

United States

Associated Press. (2025). Florida appeals court strikes down law letting minors get an abortion without parents’ consent. [online] Available at:

https://apnews.com/article/fd1cf242ca67eea8503fffb563ec00c4 [Accessed 16 May 2025].

Associated Press. (2025). Missouri lawmakers approve referendum to repeal abortion-rights amendment. [online] Available at:

https://apnews.com/article/c4f7beb07e7b3de64f3e2460bcb539c0 [Accessed 16 May 2025]. Vox. (2025). The right’s new playbook to restrict access to abortion pills. [online] Available at:

https://www.vox.com/policy/412327/abortion-mifepristone-reproductive-rights-trumprolling-thunder-ectopic-pregnancy-medication-fda [Accessed 16 May 2025].

Associated Press. (2025). Challenge to Louisiana law that lists abortion pills as controlled dangerous substances can proceed. [online] Available at:

https://apnews.com/article/4bc1ec4d1b7dfdf00b82c283ed8b7118 [Accessed 16 May 2025].

United Kingdom

Sky News. (2023). Woman jailed for taking abortion pills after legal limit during lockdown. [online] Available at:

https://news.sky.com/story/woman-jailed-for-taking-abortion-pills-after-legal-limit-durin g-lockdown-12901086 [Accessed 16 May 2025].

Sky News. (2023). Thousands march in London in support of woman jailed for taking abortion pills after legal limit. [online] Available at: https://news.sky.com/story/thousands-march-in-london-in-support-of-woman-jailed-for-t aking-abortion-pills-after-legal-limit-12904463 [Accessed 16 May 2025].

Sky News. (2023). Woman jailed for illegally obtaining abortion tablets to be released from prison after sentence cut. [online] Available at: https://news.sky.com/story/woman-jailed-for-illegally-obtaining-abortion-tablets-to-bereleased-from-prison-after-sentence-cut-12922780 [Accessed 16 May 2025].

Cambridge Independent. (2022). Cambridge rally to protest US abortion ruling as UK government rejects inclusion in bill of rights. [online] Available at: https://www.cam-bridgeindependent.co.uk/news/cambridge-rally-to-protest-us-abortio n-ruling-as-uk-gov-ernme-9261557/ [Accessed 16 May 2025].

UN Women (2015). Mexico. [online] UN Women | Americas and the Caribbean. Available at: https://lac.unwomen.org/en/donde-estamos/mexico.

Mexico women’s protest: Outrage after police fired shots. (2020). BBC News. [online] 10 Nov. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-54888105.

Brewer, S. (2025). ‘The Era of Women’: challenges and priorities in the women’s human rights agenda in Mexico - WOLA. [online] WOLA. Available at: https://www.wola.org/anal-ysis/the-era-of-women-challenges-and-priorities-in-the-wome ns-human-rights-agenda-in-mexico/.

Statista. (2021). Number of femicide victims in Mexico 2020. [online] Available at: https:// www.statista.com/statistics/827142/number-femicide-victims-mexico/.

Photo References (in order of appearance):

LSE Library. (1880) Emmeline Pankhurst. Available at: Emmeline Pankhurst, c.1880s. - Public domain portrait print - PICRYLPublic Domain Media Search Engine Public Domain Search. (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Vesalainen, T. (n.d.) Silhouettes of business people. Available at: Free Stock Photo of Silhouettes of business people | Download Free Images and Free Illustrations (Accessed: 14 May 2025).

Wikipedia Commons. (2019) Earth. Available at: File:Earth icon 2.png - Wikimedia Commons (Accessed: 15 May 2025)

Nilov, M. (2021) Close Up Photo of Vote Stickers on People’s Fist. (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Wikipedia Commons. (2022) Today’s suffragettes - the last legal protest ? (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

RDNE Stock Project. (2020) I want to be heard. (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Barratt, M. (2025). Rise Up, Women (Emmeline Pankhurst Statue), Manchester. [photograph].

Edwards, C. (2025) Sylvia Pankhurst Plaque, Manchester.

Getty Images (1984). Women rally in support of Northumberland miners.

Levenson, D. (n.d.). Margaret Thatcher. Sykes, H. (n.d.). We refuse to be second-class workers.

British Culture Archive (2025). Clause 28 Demonstration, Manchester, 1988. https://britishculturearchive.co.uk/peter-j-walsh-clause-28-demonstration-manchester-1980s/ (Accessed: 16.5.25).

Patrick, Howard (1970). “Second wave feminism- accomplishments and lessons.” Against the current. Available at: https://again-stthecurrent.org/atc211/second-wave-feminism-accomplishments-lessons/.

Getty (1940). “Remembrance day: Women hero’s of perilous WWII munitions factories finally honoured ”. Available at: https:// www.google.com/imgres?q=women%20working%20in%20factories%20ww2&imgurl=https%3A%2F%2Fi2-prod.mirror.co.uk%2Farticle1427843.ece%2FALTERNATES%2Fs1200d%2FGirls%2520at%2520a%2520South%2520Eastern%2520Command%2520munitions%2520factory%2520preparing%2520shells%2520for%2520use&imgrefurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.mirror. co.uk%2Fnews%2Freal-life-stories%2Fremembrance-day-women-heroes-of-perilous-1427595&docid=ItL15O9HFActdM&tb-nid =44-ZPkncaHBaHM&vet=12ahUKEwj08fT1seSMAxV5QkEAHSxsH0kQM3oECGQQAA..i&w=1200&h=675&hcb=2&ved=2a-hU KEwj08fT1seSMAxV5QkEAHSxsH0kQM3oECGQQAA.

Magnolia Box (1960). “1960s 1970s Exhausted Housewife Sitting At Bottom Of Stairs Surrounded By House Cleaning Equip-ment”. Available at:

https://www.google.com/imgres?q=women%20cleaning%20in%20the%201960s&imgurl=https%3A%2F%2F-previews.magnolia box.com%2Fcorbis%2Fmb_hero%2F42-45533331%2FGLOBAL-FAP-12X12_scaled-bordered_850. jpg&imgrefurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.magnoliabox.com%2Fproducts%2F1960s-1970s-exhausted-housewife-sitting-at-bottomof-stairs-surrounded-by-house-cleaning-equipment-42-45533331&docid=9-4XyrtLXEEGLM&tbnid=Pll4yztQCO50LM&vet=12a-h UKEwjHiuO6mt2MAxUHT0EAHSh1AncQM3oECHwQAA..i&w=850&h=850&hcb=2&ved=2ahUKEwjHiuO6mt2MAxU-HT0EAHS h1AncQM3oECHwQAA.

Wikipedia (1982). “Greenham Common women’s protest 1982, gathering around the base”. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Greenham_Common_Women%27s_Peace_Camp#/media/File:Greenham_Common_women’s_protest_1982,_gathering_ around_the_base_-_geograph.org.uk_-_759136.jpg.

Wikipedia (n.d.). “Alice Paul toasting (with grape juice) the passage of the nineteenth amendment.” United States Library of Con-gress Prints and Photographs. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equal_Rights_Amendment#/media/File:Alice_paul.jpg Mansueto, CM. (1983) Peace camp at Greenham Common. Edition. Vol13. No.3 https://www.jstor.org/stable/25774837?search-Text=Greenham+common+women%27s+peace+camp&searchUri=%2Faction%2F doBasicSearch%3FQuery%3DGreenham%2B-common%2Bwomen%25E2%2580%2599s%2Bpeace%2Bcamp%26so%3Drel&a b_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcon-trol&refreqid=fastly-default%3Aafb4eccdea4dd48421cfcd203e283188&seq=1 Barbra, BB. (1971) The Equal Rights Amendment: A Constitutional Basis for Equal Rights for Women. Vol. 80, No.4. https://www.jstor.org/stable/795228?searchText=The+equal+rights+amendment+act&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasic-Se arch%3FQuery%3DThe%2Bequal%2Brights%2Bamendment%2Bact%26so%3Drel&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_ gsv2%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3Ac4d92bfa2cd7d78429761616460fd008&seq=3

Perry, L. (2015) I can sell my body if I wanna. Available at: https://csalateral.org/issue/4/i-can-sell-my-body-if-i-wanna-riot-grrrl-body/ (Accessed: 22 April 2025).

Cipalla, R. (2022) Flyer for Riot Grrrl Convention, ca. 1992. Available at: https://www.historylink.org/File/22505 (Accessed: 22 April 2025).

Jenkins, R.M. (1991) Hill testifying in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anita_Hill#/ media/File:Anita_Hill_testifying_in_front_of_the_Senate_Judiciary_Committee_(cropped).jpg (Accessed: 22 April 2025).

Ezekiel. (2011) The Spice Girls performing during a reunion concert in Toronto. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spice_ Girls#/media/File:Spice_Girls_in_Toronto,_Ontario.jpg (Accessed: 22 April 2025).

Collinson, N (2025) womens right protest mexico. (for all photos and videos).

Support Resources:

If you find yourself affected by any of the content in this magazine, please check out these links:

The African and Caribbean Women’s centre:

Practical support for Black women and girls. https://africab.org/

The LGBT Foundation:

National charity based in Manchester. https://lgbt.foundation

Gendered Intelligence:

Understanding gender diversity. https://genderedintelligence.co.uk/

Rape Crisis:

Working to end sexual violence and abuse. https://rapecrisis.org.uk

Refuge:

Specialist support for victims of domestic violence. https://refuge.org.uk/

Ngos promoting gender equality in Mexico:

https://borgenproject.org/gender-equality-in-mexico/

Thank you for listening to our voices.