Maitland Regional Art Gallery acknowledges that we are on the Country of the Wonnarua people. We acknowledge with deep respect their continuous connection to culture, community and Country.

Robert Fielding

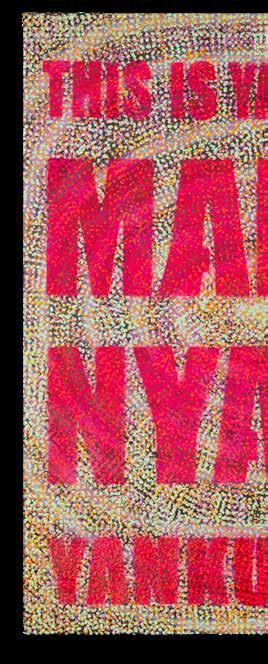

This is what it’s all about.

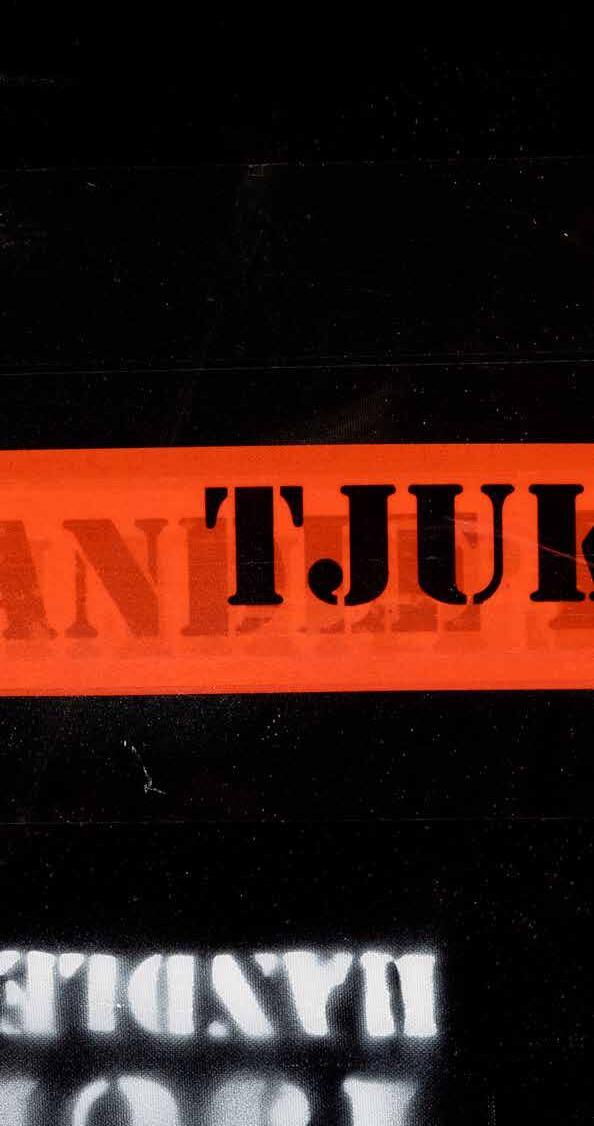

Tjukurpa

Maitland Regional Art Gallery acknowledges that we are on the Country of the Wonnarua people. We acknowledge with deep respect their continuous connection to culture, community and Country.

Robert Fielding

This is what it’s all about.

Tjukurpa

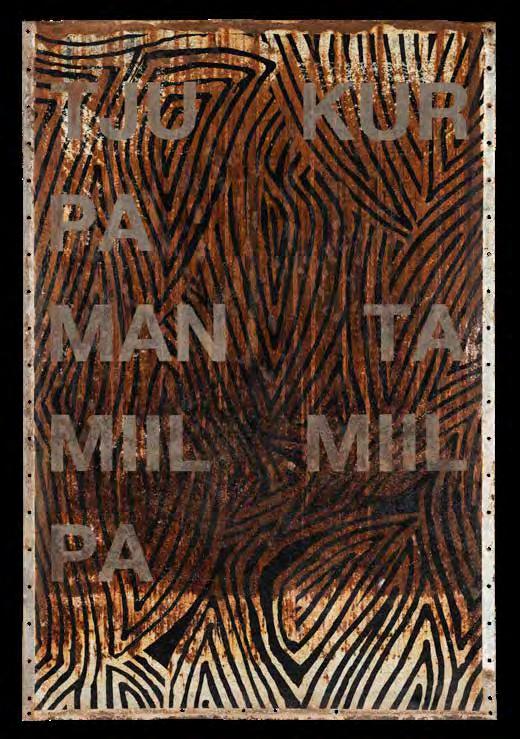

It’s on a lintel. It’s on the doorway. It’s about holding onto my teachers, my teachings, men, women, men that once sat in this room with power, that still has power that is dead. You must hold onto the importance of what Tjukurpa means. What miil-miilpa means, what manta means, what ngapartji-ngapartji means, what tjungu means. What malpa means. It means friends, storytelling, looking after each other, nurture, respect, acknowledge, embrace, fight, argue, forgive, respect, reconcile.

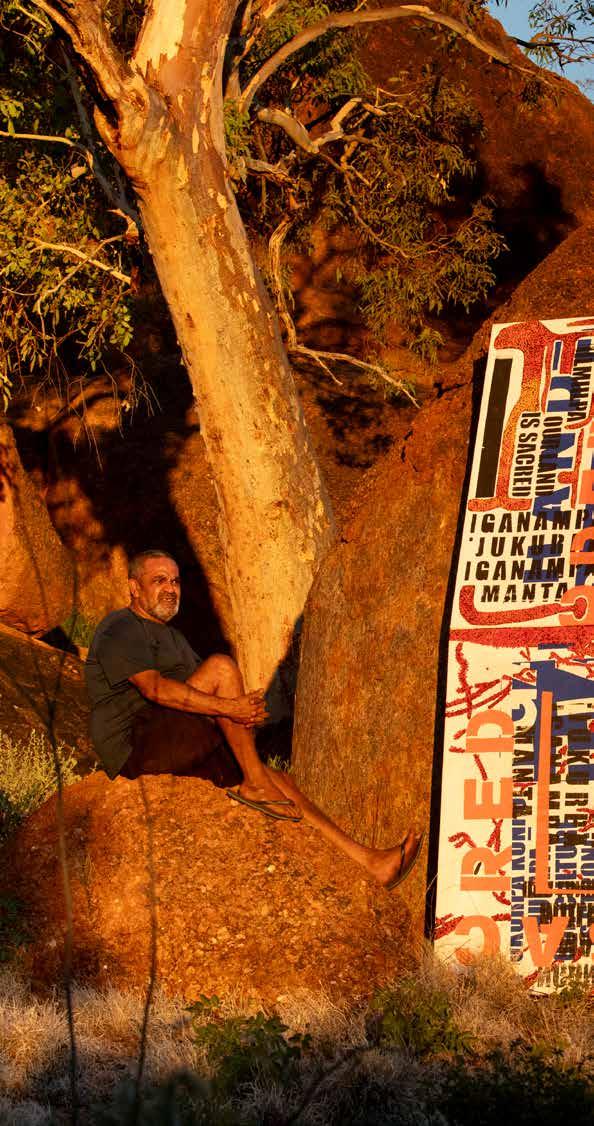

When you meet Robert Fielding, he takes both your hands in his and looks you directly in the eye. He is all things welcoming, curious and quietly challenging. You need to listen. Keep up. Conversation is fast paced. Dates and numbers punctuate his storytelling. The significance, burden and freedom of certain dates and times in his own life and that of his family. He is both forthright and poetic. Stories emerge along a timeline, 1927, 1948, 1969, 1998, 14 October 2023. These numbers pinpoint very specific events that are all present in the work he makes.

Robert Fielding is an artist, storyteller and a keeper of Tjukurpa (ceremony and culture). Descendant to the first Afghan cameleers, and the Yankunytjatjara and Western Arrernte people of the central desert, Fielding lives and works in Mimili Community on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands.

With a committed curiosity, a passion for collaboration and a compelling turn of phrase, Fielding is one of Australia’s leading artists. Over the past year, he has worked closely with the team at Maitland Regional Art Gallery and embarked on conversations with Community here on Wonnarua Country.

This exhibition and publication is the result of a partnership with Mimili Maku Art Centre, a place Robert says, “is the heartbeat of Community.” The words of Robert throughout this publication were part of a conversation in the Wati (men’s) studio in Mimili, filmed and transcribed as part of an extensive project to archive and celebrate the Mimili art movement.

The Wati studio is a place of quiet intensity. It is a place constantly changing with new process, new ideas and Robert’s unflinching commitment to telling the stories of his Elders, his teachers, his family.

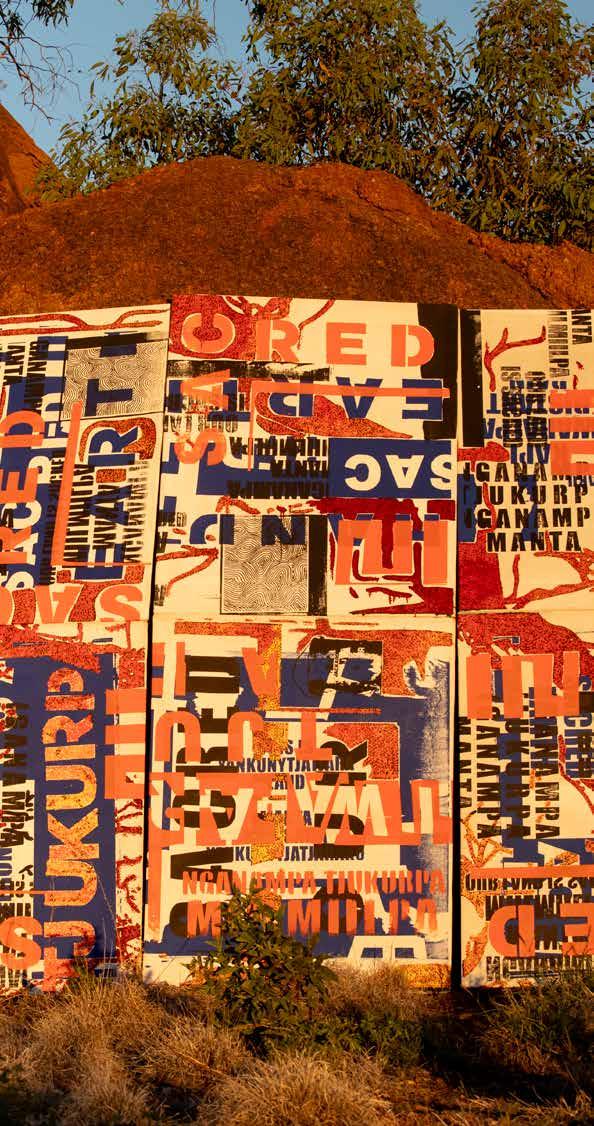

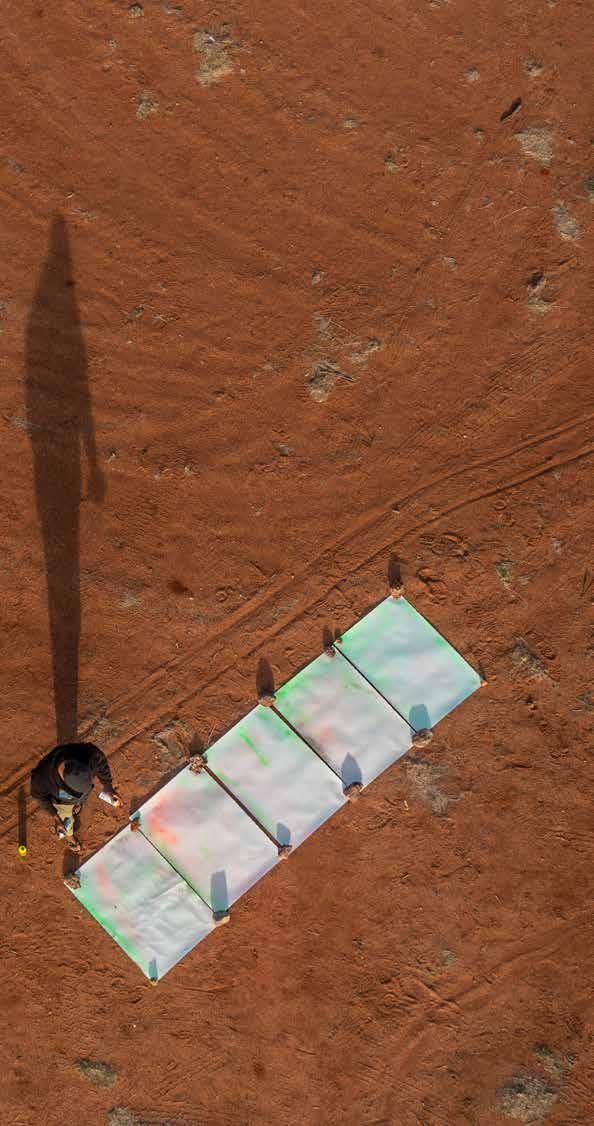

It is Fielding’s enduring and persistent printmaking that is the heart of this exhibition revealing a preoccupation that runs through all of his work. Stories emerge through the act of printing with all its urgent immediacy. Printing, pamphleteering, embossing, replicating. Fielding does all of this and then works over things again and again. A pamphlet becomes a paste-up that makes its way onto a printing press in Naarm and a photograph developed under the sun gets reprinted and worked over, screenprinted. A car in the desert on the road to Indulkana gets painted then photographed then sent to the Mimili Repco (the tip), pressed into a cube and then thrown like a dice onto the floor of a building on Wonnarua Country.

We would like to thank the generosity of the Mimili Community and Tuppy Goodwin, Chair of Mimili Maku Art Centre for working with us ngapartji-ngapartji, and extend this to Fielding’s long-time collaborator Angus Webb and Art Centre Manager Anna Wattler for their energy and expertise in the delivery of an exhibition that celebrates an extraordinary artist. A big thankyou to Erin Vink, Curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, for the insight and scholarship in her accompanying essay. To Robert, a hearty congratulations and warm thankyou for sharing your heart and creativity with us here on Wonnarua Country.

Palya Gerry Bobsien

Director Maitland Regional Art Gallery

These ones here. It’s about words. It’s about, you know,

our culture is strong. I’m only talking to tell you a story, but no matter how much trouble and how much we go through, this culture is strong. It’s powerful.

You know how secret this is?

This is a snippet. What I do as an artist is a snippet. What our other colleagues who paint tell you, is a snippet. They’re not telling you that truth. Telling you that whole story. But these are my stories whilst I live here and about how important it is that you must hold on to the stories of this environment, this space, this place, this time. Not only you as an individual, but your whole family group. That when you create, you create for all. Everybody. This (the art centre) is the heartbeat. This is the centre of unity, the centre of gravity.

Robert Fielding

Robert Fielding

Using layers to reveal and conceal. How much secrecy is in my work?

How much, um, Da Vinci Code is in my work? Do you know my son, Zaachariaha? Do you know what he does with his work? Read it. We are no different. We are telling our story. We’re telling our daily routine. We are telling our stories through language. English. A full sentence within the canvas? A half a sentence, a half of hidden objects within a painting, within a painting.

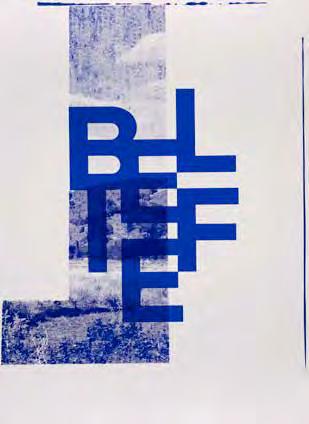

The work is about respect. It’s about holding onto belief. And that runs across everything. This is about

Handle It. I can’t even handle myself sometimes, you know, because you have so many feelings and emotions towards daily routines and daily life. We are all affected by our kinship, our relationship, our connection, our success, our highs, our lows, our rejections. But this work tells us don’t ever let go of that light, that candle of what Mimili is all about.

The roots of this community. You must not let go of the teachings of those Elders. Don’t ever let go of what Mimili has given us. We have a foundation

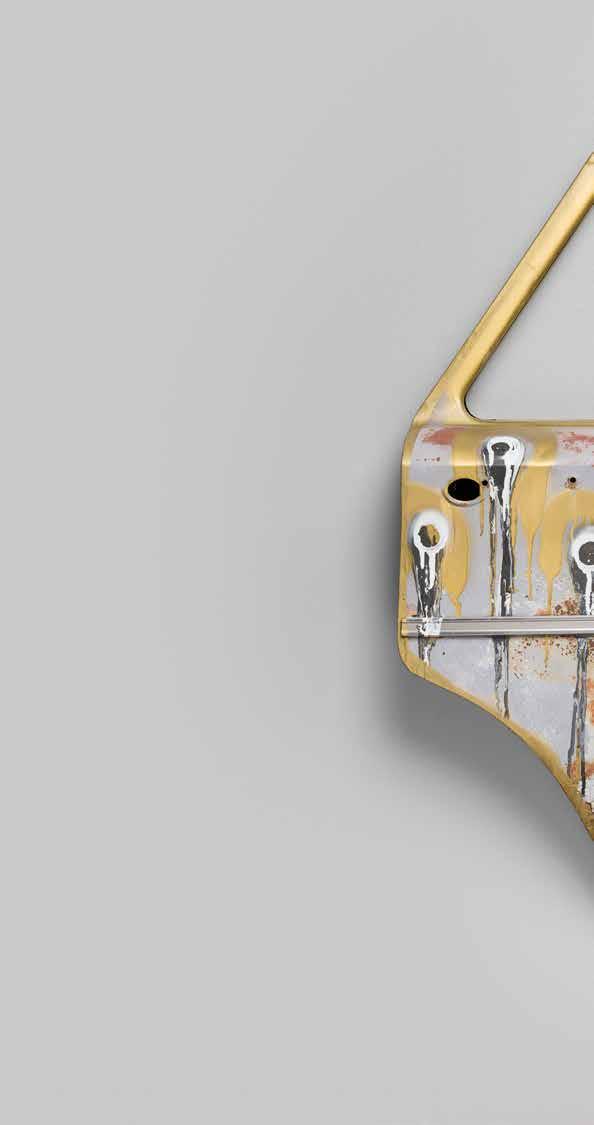

Untitled 2024

reclaimed car wreck with aerosol paint alteration, 100 × 100 × 90cm (detail p.26—27, p.30—31)

Dedicated to my Malanypa Ngupulya Pumani (RIP)

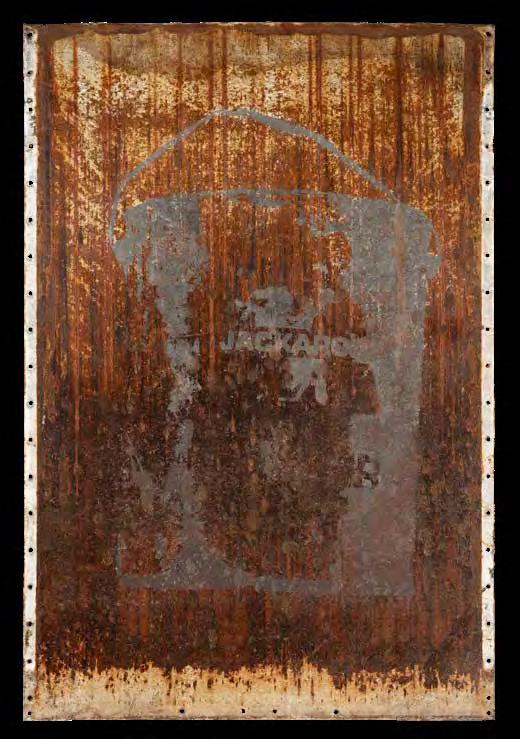

reclaimed water tank panel with sand blasted alterations, 170 × 122cm

Robert Fielding

bronze-cast spear and found object with alterations, 189 × 83 × 60cm

bronze-cast spear and found object with alterations, 189 × 83 × 43cm (detail p.42—43)

Like all my body of work – everything transitions from paper to pigments, to elements. Including my objects.

What are these objects?

What do they conceal?

What do they hold?

What do they maintain?

What do they carry?

They conceal the knowledge. They conceal secrecy.

Like the flour buckets. The jackaroo and the tea, sugar, and flour. They became my shields. They became my warriors. It was always about what was inside. The flour, the tea, the sugar. What it did to our health. But what happens when the flour bucket’s empty from flour? But these were objects and vessels. An instrument, a drum. It could have been the foot stool of a bed. And that flour bucket is very important throughout my body of work and the

the spears, that Mimili was once known for. It’s still known for

making.

Mama Tjamu, Sammy Dodd is the best craftsman on the lands for

making, and if you was to own one of these artworks know that it has a very big history. History of his forefathers and this man that I’ve sat and collaborated with over many years with his wife, Nana Ngilan. I wanted there to be eternal objects of

They led me into their world. Tjamu I want you to make me one spear. I want you to live for eternity. I want you to live like a mineral. I don’t want you to die. Wood will die and burn so we made it into bronze. We made that into bronze that’s eternal. When I die, when he dies, it’s still here. It is memorial.

found car doors with aerosol paint alterations, 110 × 100 × 15cm (detail p.46—47)

bronze-cast spear and found object with alterations, 198 × 33 × 60cm

found car doors with aerosol paint alterations, 110 × 100 × 15cm (detail p.50—51)

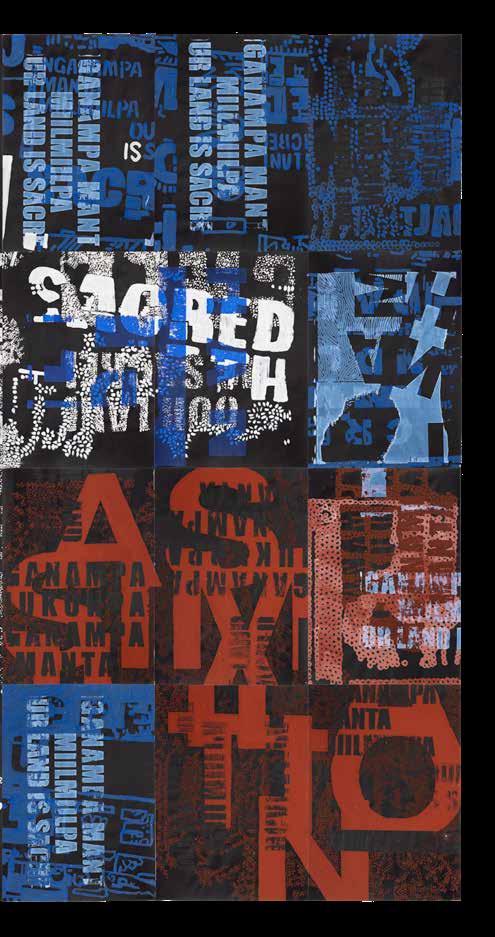

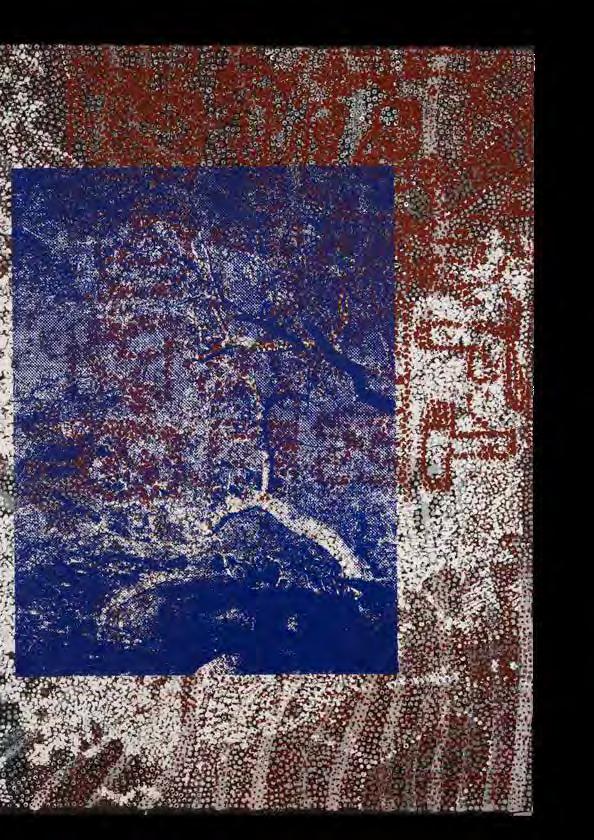

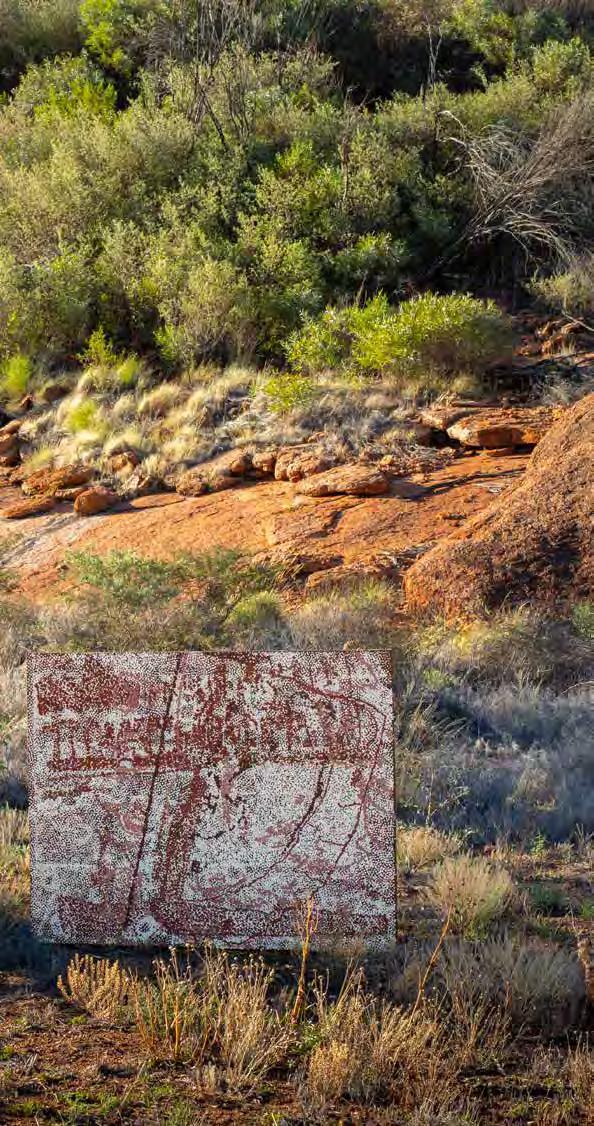

Tjukurpa Manta Miilmiilpa 2019

reclaimed water tank panel with aerosol paint and sand blasted alterations, 170 × 122cm

Robert Fielding

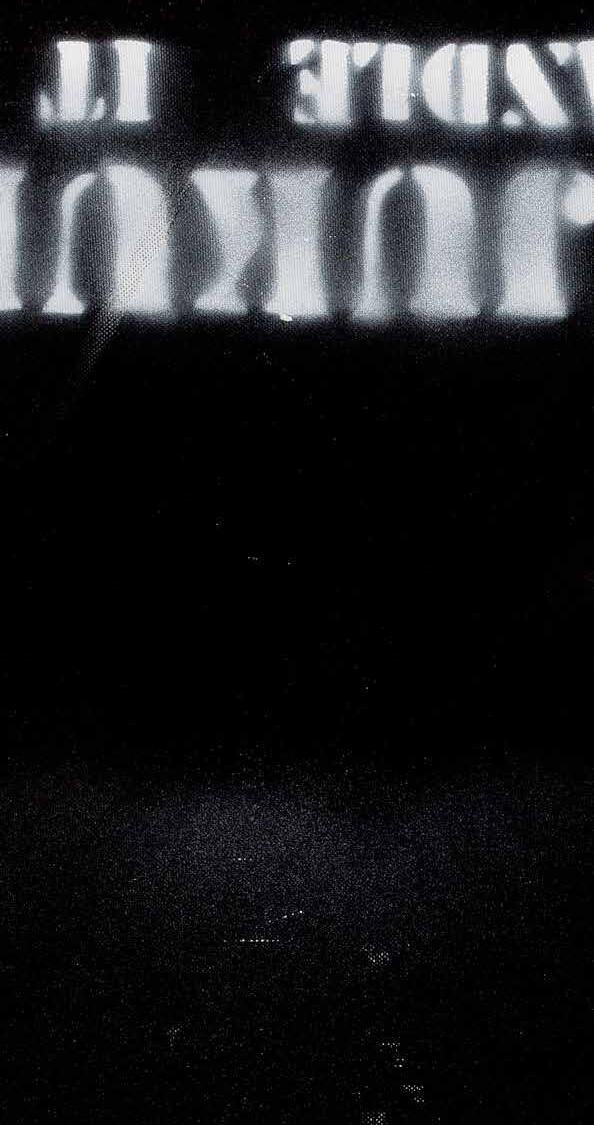

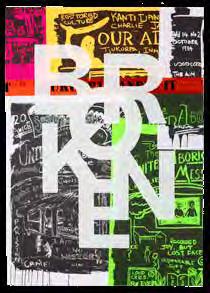

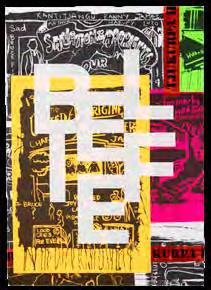

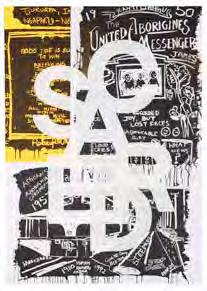

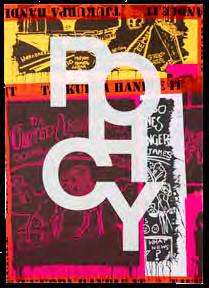

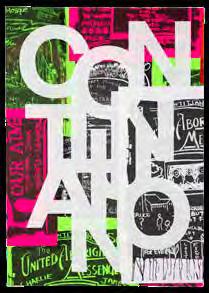

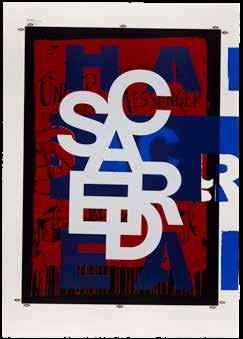

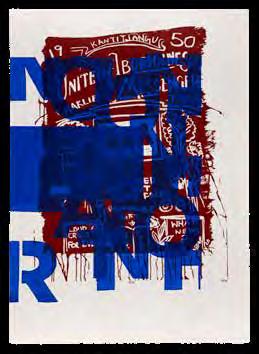

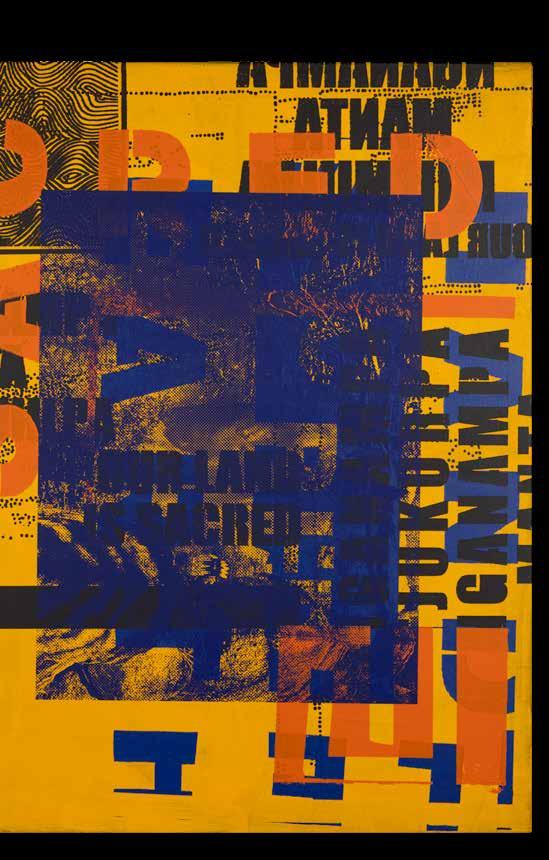

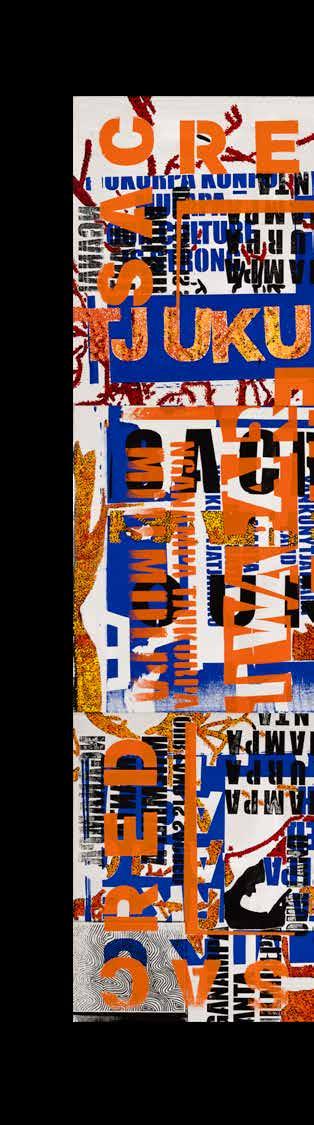

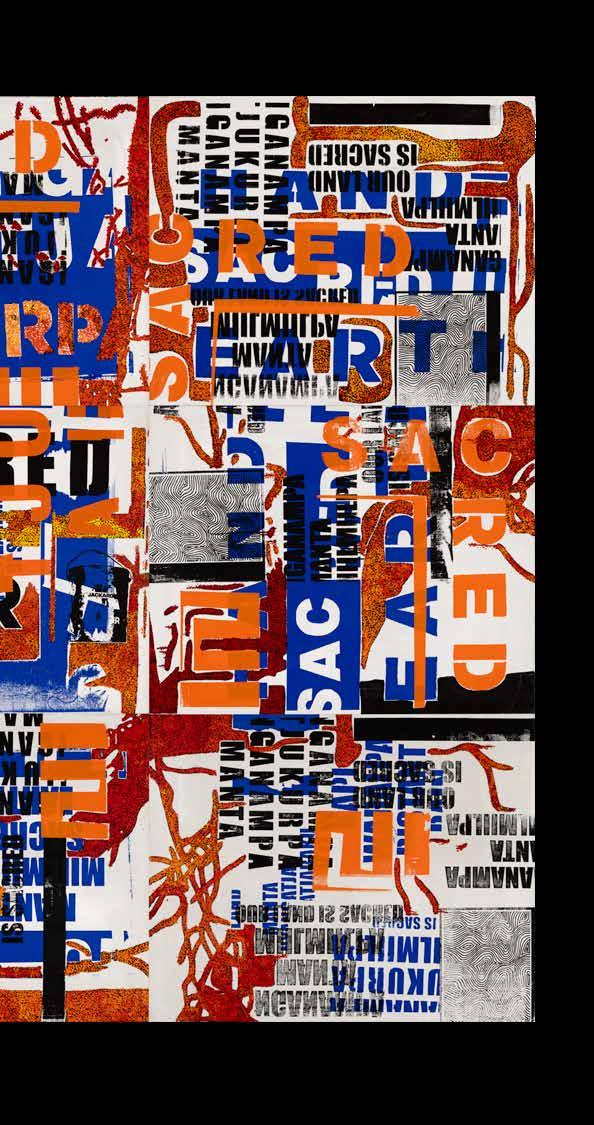

So, these was gonna be street art. These were just gonna be on the streets and just slapped on the wall. But they are meaningful. They were personal. They were actual events that happened to children. Things that happened to lost, found, reconciled, taken, language. It is about one’s personal history and these words are not my words. They’re words of actual events of stolen generation. Continuation, traumatic, sacred, assimilation, broken, slavery, belief, forgive, reconcile, exempt.

This is what all this work’s all about. It’s about holding onto the actual photographs that we saw at the state library, the United Aboriginal Messenger. My dad never ever talked about his time in Colebrook Home. My sister still lives on that road on that foundation of Colebrook Home on Stoney Creek. And that those pathways and that creek that runs through that country. My father was the first person that went back on to that land and lived with these children once he grew up.

He spoke but he never spoke hate. He never spoke anger. He spoke about how important these stories were. Of that railway line, the Ghan, the mosque, the train that travelled through that region. The Afghan pioneer that I am a descendant of that also lived in Herbert Springs. That travelled through

That my grandmother Miriam Khan delivered my father in 1927 at Lilla Creek Station. That my mother was also born 1928 then at Dalhousie. My grandmother Miriam delivered my father then my father marries my mother and has 12 children.

My grandmother was a very secretive woman. A very nomadic woman, Miriam Khan. She’s in a lot of magazines and a lot of Afghan books. The Marree Mosque, the Cameleers, the Flight of an Eagle She spoke her father’s language that you’ll see within this work. It’s about Afghans and pioneers and cameleers who played part of that early transitioning of opening the north to the south and the south to the north.

I am third generation of the pioneers that opened this country. I am also from the fruit and the womb of the black velvet.

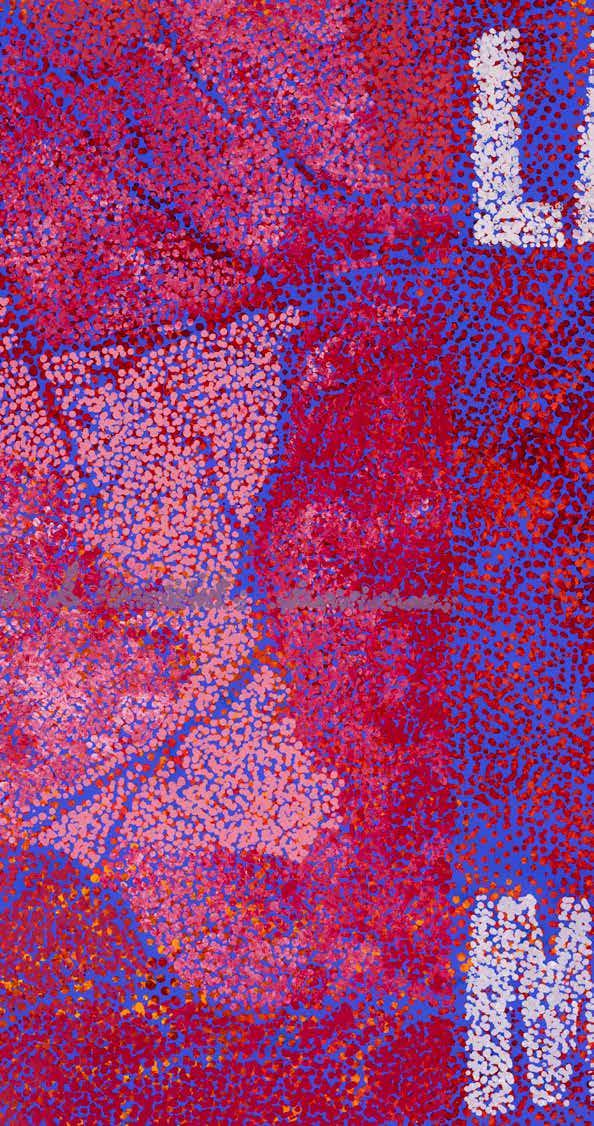

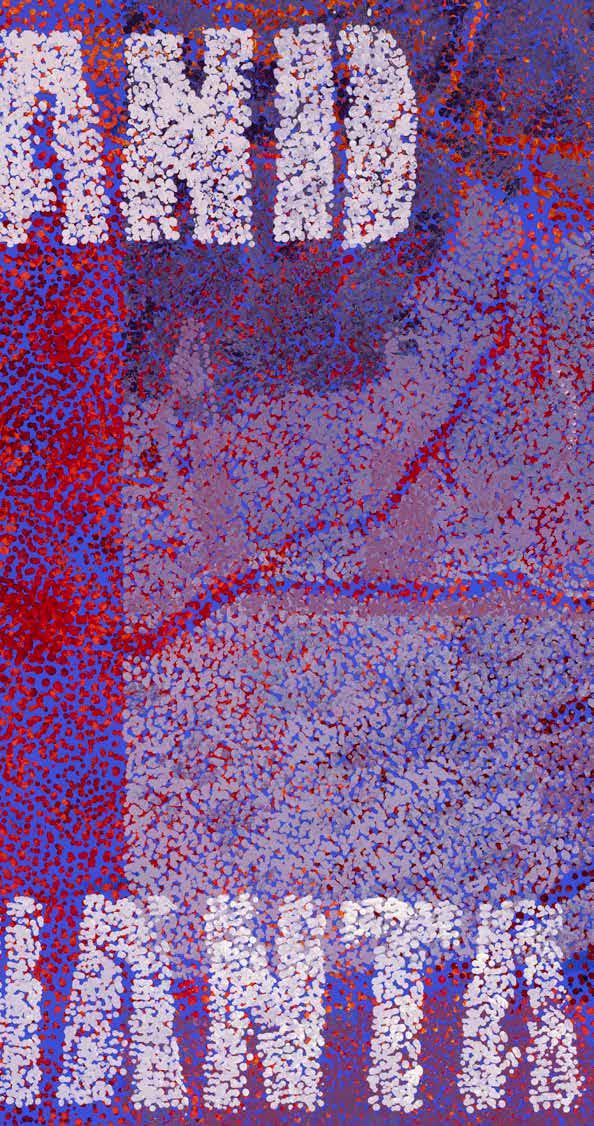

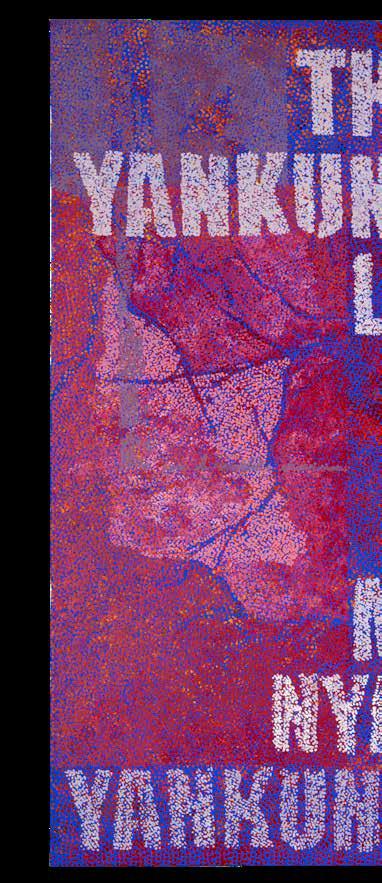

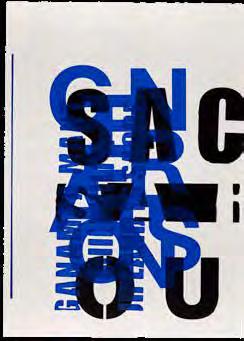

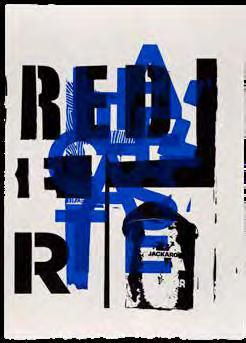

AIM 2023—2024

acrylic and aerosol paint on found paper, di-bond and packing tape, 84 × 59.5cm each (p.58—59)

acylic on linen, 198 × 198cm (detail p.64—65)

Robert Fielding

This body of work is about stolen generation. It’s about connection. It’s about the trauma. It’s about the sacred. It’s about assimilation. It’s about broken. It’s about slavery. It’s about belief. And do you know what you learn from this? You acknowledge it. You acknowledge but you cannot live through the eyes of your forefathers. So, one has learned to forgive. One may sound like a double minded man who is unstable in all his ways. But one is smart. One has learned how to manoeuvre and to travel between two worlds and to respect. We are

50/50. You must respect Black. You must respect White. We may not agree with a lot of things but we must acknowledge and respect. Because it’s going to be a continuation. It’s about how we tell our stories and how we live through the eyes of our forefathers.

Hold on to the importance of human race. Hold on to the importance of who we are as custodians, carers, storytellers.

These words are not my words. a stolen generation. These are the words that I used and stripped and ripped out of the books of stolen generation. I forgive, love for all hatred for none. That is Islam. I may sound like a very strong, belligerent person but I’m not. I’ve learned to forgive and to learn to look after other people’s belonging and to correct them and to teach them and for them to appreciate that time that they worked with us. ‘Cause when I first came back here (Mimili), it was fucking hard. I didn’t know their ways. It’s teaching and learning in a different way. A different meaningful way of Anangu that’s about learning and listening and being patient. I was a very hard person when I come here. I had a teacher. I don’t know how he was patient with me. I do not know how he was so patient with me.

That old man passed away in 2015. That old man moulded me and shaped me how to manoeuvre through two worlds, black and white. What you see in me here as an artist and as a person is totally different to what you see me in secrecy. The secrecy of holding onto the importance of stories of the land and holding onto Tjukurpa and how important it is that I cannot disrespect that old man’s teachings, what he had taught me. He made me a better person. He’s made me a better person on who I am as a descendant of stolen generation. I’m not stolen, I am found. I have a voice that my father was a Yankunytjatjara boy from around Granite Downs and Oodnadatta Dunjibar.

acrylic, pearlescent ink and found object on paper, 220 × 165cm

Robert Fielding

Robert Fielding

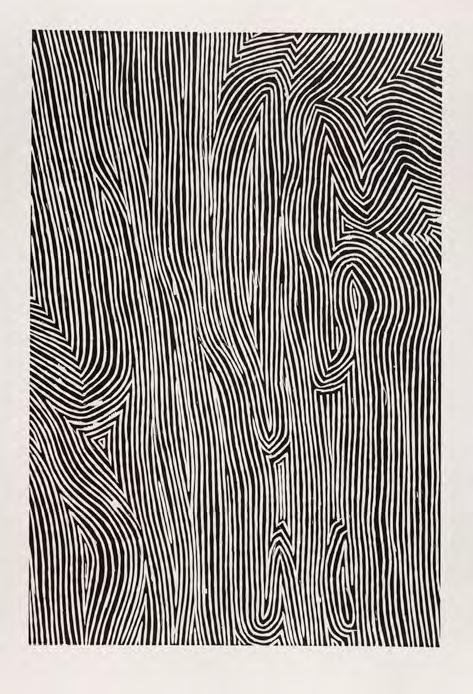

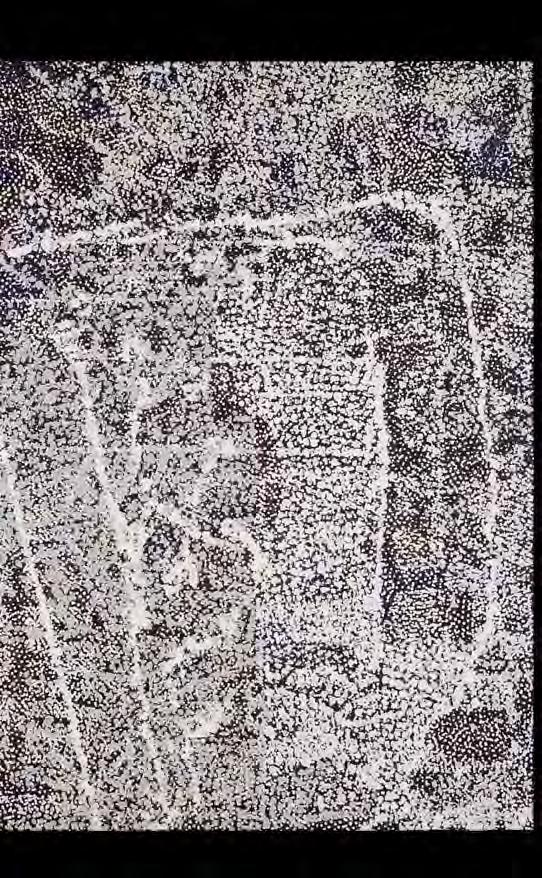

Manta Miilmiilpa 2021

acrylic and fluorescent aerosol on linen, 152 × 122cm

Robert Fielding

I love breaking boundaries. I love inventing. I love inventing with the right and the left and the left and the right because it’s always a hit-and-miss. I’m inspired by much, but I have always been drawn back to the work of Chuck Close and Rosalie Gascoigne. My inspiration and drive come from these different ways of making.

I am also deeply influenced by Mama Peter Mungkuri. You know the way he is connected to punu (trees) and how important this is for our Tjukurpa.

I’m not going through feelings or emotions, I just want to create something that is unique, that is an onion. How many layers does an onion have? An onion has many. So my argument has many layers of feelings, emotions, achievements, accomplished, unaccomplished, unfinished.

I was always fascinated by embossing. I said, “Angus?”

And he said, “Robert, what the fuck are you up to now?”

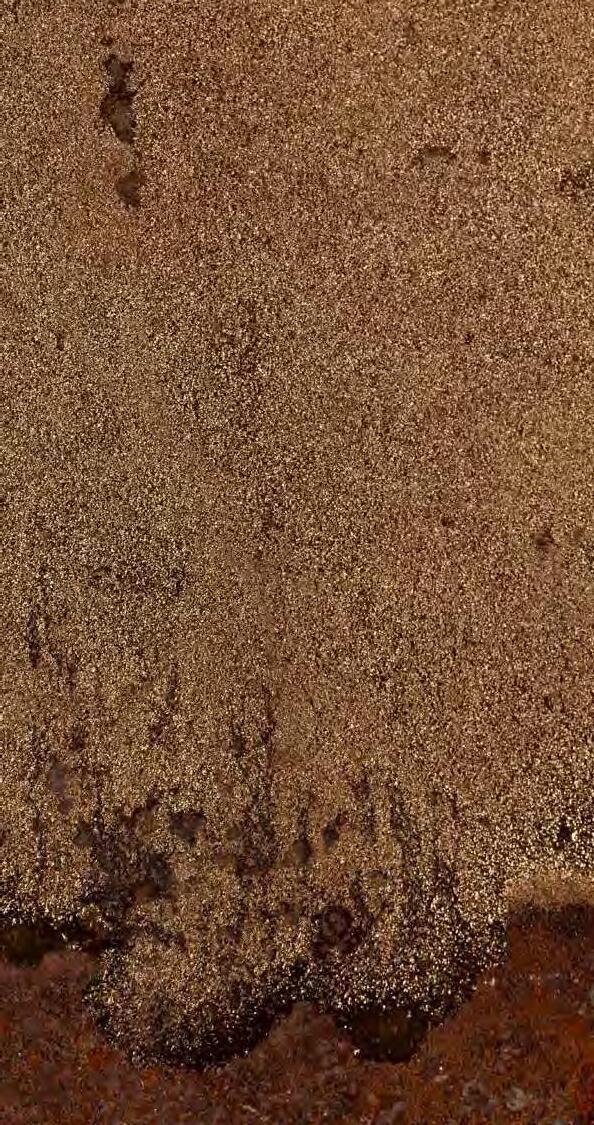

This is my DNA, this was for my sister. I’ve worked hard for this to give my sister a closure of who she was as a person and who she was as a mother. You hold it up, then you see it It’s about

It’s about we as individuals, we as people that hold and work together. But look at that thing. It’s only black and white but you will see yellow or red in there. The transformation when it moved from the board to the paper. The pigment’s still on there. It transferred and is beautiful. It’s about moving from a board to the print, from a print to the embossed. Everything is always moved on to become something else. It’s always used and worked over but in a different context.

This is my DNA. When I was 13, my father taught me how to ride a horse. My father taught me how to ride a horse bareback. My father taught me how to sit in a stock saddle. My father taught me how to sit in a jockey pad. I could still ride a horse if I was given that opportunity, ‘cause when you hold the reins, you hold the reins in a specific way. You learn how to manoeuvre your feet and the way you sit on a horse and the way you ride bareback.

Me and my father became best friends when I turned 21. When I had my first child. My father spoiled me. He spoiled me rotten. When I had my first child me and my father became the best of friends. It was short-lived. In ‘96 he died. Everything I do today in my art, not because of who I was born of - an Inkamala and Malbunka of powerful women and Afghan pioneers, this is about my father. My father was the first Aboriginal person to win the Australasian Cup . My father worked in the 1970s and 80s for the Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement. These people on this land and country in South Australia are very lucky that they’ve got what they’ve got because of Land Rights. My father was part of the first foundation with Christopher Charles, Gordon Coulthard, Joseph Hull, and many other prestigious men that fought for Land Rights.

Milkali Kutju 2024

embossed and printed pairing, emu fat, ink and ochre on paper, 108 × 150cm

ash, pigment, charcoal and acrylic on linen, 152 × 122cm (p.95, detail p.90—91)

Robert Fielding

These prints are about holding onto the importance of Mimili. Holding on to the importance of all your male teachers, all your matriarchs,

It’s about holding on to what Mimili is about. because this is where I came. And it’s about holding on to the importance of what this is, the importance of taking back the land and to hold on to it tightly. And to hold on to the importance of land. You know, holding on to the importance of how one can tell the stories of these forefathers.

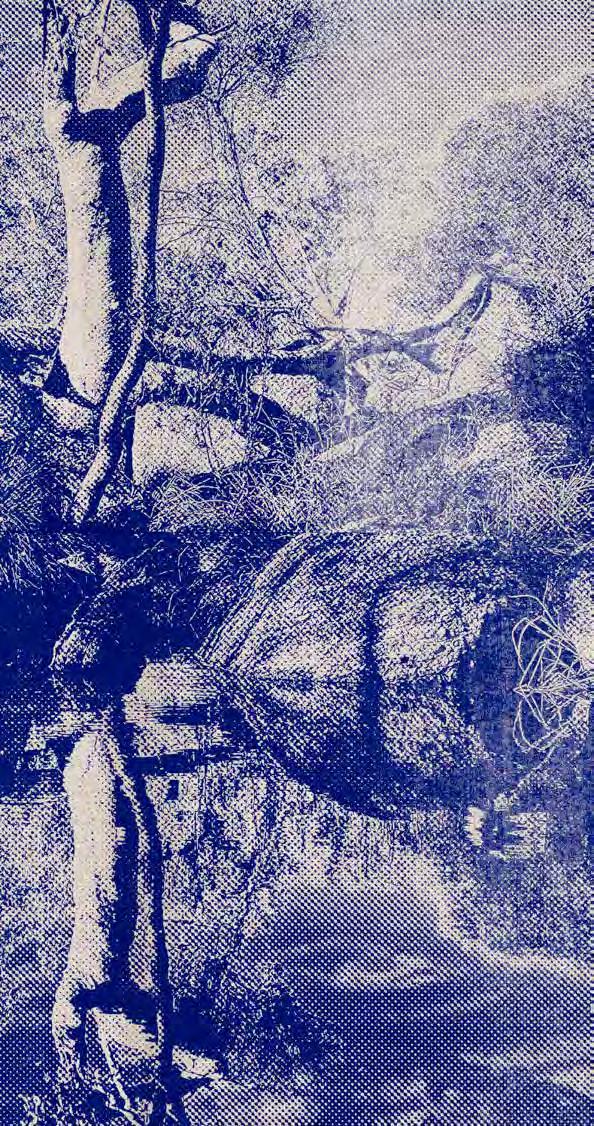

That I must also show what fauna means of Mimili, how important the trees are, how important the fauna, the flora. The importance of colour, the schemes, the language, and telling the stories of me as an individual by revitalising what Mimili is all about. And how important the community is, and how important these trees are. You know, the traditional methods of preparing foods, medicine, utensils, and weapons all from native plants. This is why these trees are important. This place is important.

It is about blue, it’s about resources, it’s about life, it’s about water, it’s about trees, and it’s about fauna. It’s about Mimili. This is my grandchildren’s home, they are born of matriarchs and patriarchs of this community. For one to hold on to the importance of those children’s stories, to hold on to the importance of what these trees mean, that they belong to my mama,

Mr Mungkuri was our father of trees.

acylic on linen, 198 × 230cm (detail p.98—99)

Robert Fielding

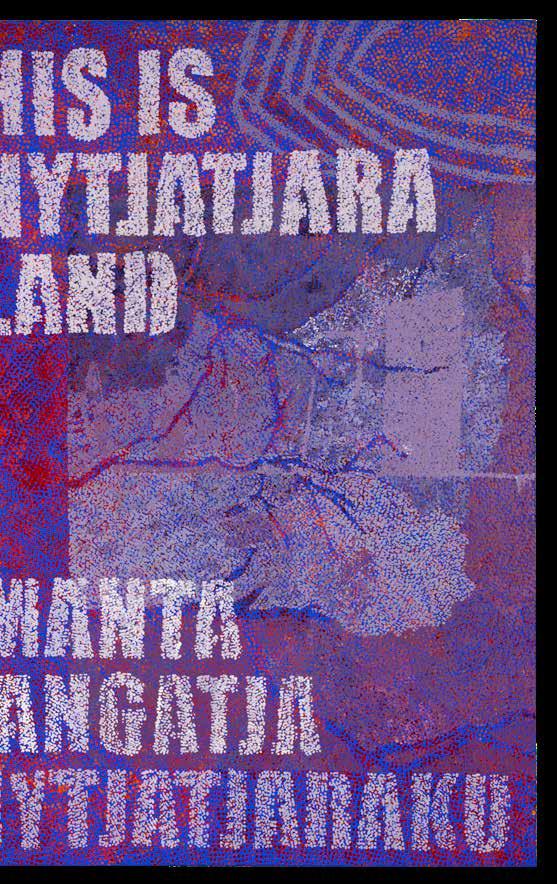

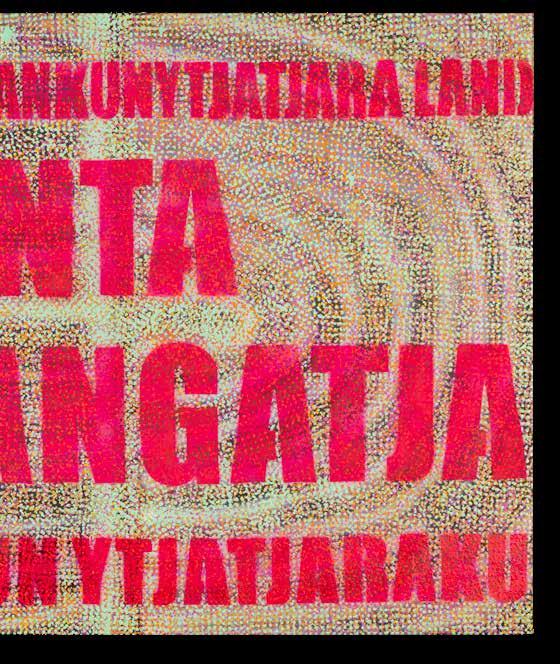

Manta Nyangatja Yankunytjatjaraku 2021

acrylic and fluorescent aerosol on linen, 152 × 122cm

Robert Fielding

by Erin Vink

More than any other artist from the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands, Robert Fielding and his ideas on culture have marked my work. I want to move quickly through the meaning of contemporary Indigenous storywork as a methodology in Australian First Nations art, and the history of the artist’s direction of it, because writing and reading stories is how I have come to understand the placement of Fielding’s sense of self and sovereignty, between the margins of regional and urban Indigenous worlds. In Fielding’s practice, storywork overturns racist notions of one’s Aboriginality to reveal cultural practice shrouded in mystery. His canvases are not open, his constructed landscapes decisively opaque. Fielding makes us question what it means to picture the world, so that we can better understand it as an image. As Fielding reminds us, culture is not some unchanging, unmovable, absolute entity. It is ubiquitous, all-knowing, and ambiguous to western art historical study.

Stó:lō academic Jo-Ann Archibald Q’um Q’um Xiiem first coined the term ‘Indigenous storywork’ in 2001, to describe a form of storytelling used across various cultural forms to encourage focus on Indigenous stories for meaningful education and research.1 She argues:

Special connections to the land – to “Mother Earth” –help in strengthening our cultural identities. It is important to recognise the spiritual power of particular places and the healing nature (physical and emotional) of the environment. I also learned to appreciate how stories engage us as listeners and learners to think deeply and to reflect on our actions and reactions … I call this pedagogy storywork because the engagement of story, storyteller, and listener created a synergy for making meaning through the story and making one work to obtain meaning and understand.2

The past ten years of Fielding’s prolific artistic career has seen some of his best work employ an Indigenous storywork methodology to map the deep past. The more culturally loaded Fielding’s work is, such as the seminal bodies of work Mayatja Pulka: The Elders 2017 and 2021, and Milpatjunanayi 2023, the more successful his practice is in speaking to the authorities he has sought, from Ancestors, Elders and Country. Take Mayatja Pulka 2017 for example, where he looks deep into the eyes of his mayatja. In constructing the story of himself and his relationship to the lens, then extending this to include his sitter, Fielding teaches the viewer that to be Anangu is to be an orator - a strong keeper of tjukurpa, inma and miil-miilpa.3 As a group, Fielding’s series celebrates the mayatja and their important cultural leadership; as singular images, they tell intimate stories of the individual and how their own cultural practice has impressed upon Fielding, such as the late Kunmanara Mumu Mike Williams of Mimili.

As the artist states:

I

wanted to capture the essence of each artist … Through our shared lore and culture, they are also mama, kamuru, ngunytju, kuntili, marutju.4

Shown at the Art Gallery of South Australia for Tarnanthi: Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art in 2017, Fielding’s Mayatja Pulka also extends towards critical interrogations of Indigenisation practices within cultural institutions, particularly those enmeshed within the discriminatory history of colonial photographic image making.

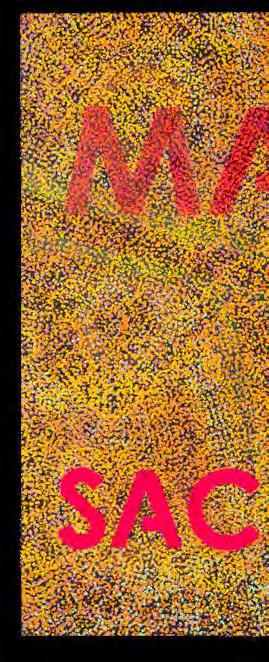

When I write about Fielding’s storywork, I also acknowledge the poetic brevity of the visually didactic metaphors he employs to put one into the critical interface between seeing and knowing. This is how Fielding reinscribes agency and Indigenous voice within the archive, particularly around notions of language and sovereignty. What I am speaking about is Fielding’s proliferation of text-based artworks that blend Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara and English inscriptions. It is possible to track the evolution of Fielding’s language artworks to a 2015 screenprint which used the phrase ‘Milkali Kutju’ as its title and within the artwork, ‘You See Black, I See Red’, as a deliberately provocative overlay. In calling for unity and an end to racial prejudice, this seminal work won Fielding the work on paper prize at the 32nd Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards (NATSIAAs). Following this success, Fielding went on to produce an extended series of works on paper and canvas which explores the notion of milkali kutju, including his 2017 award winning work made for the 34th Telstra NATSIAAs which blended the visual language of the dot with the composition of political poster making. This process, balanced with Fielding’s cultural

Robert Fielding

positioning as the son of a Stolen Generation survivor, resulted in images that offer audiences a fixed sense of place and time, whilst allowing for the Pitjantjatjara to counter the spatialising powers of the archive and all its tenets of classification. In Fielding’s more recent videowork made for the online exhibition Wirura kanyini 2020, to his Archibald Prize portrait of Tuppy Ngintja Goodwin Mayatja (keeper of song and culture) 2024, the use of inscription reveals Fielding’s understanding of spiritually embodied knowledge, to reconceptualise the boundaries of Aboriginal art narratives away from non-Indigenous understandings. Even whilst working across multiple mediums, the resulting artworks are collectively singular examples of storywork in practice that give meaning to Anangu knowledge systems for the purposes of celebration and education.

Fielding extends this notion with AIM 2023, (p.62—63) an installation of ten printed synthetic polymer and aerosol paint prints. This series addresses colonial missionary control of Indigenous bodies and minds and can be seen as the culmination of over four years of interrogation into Indigenisation practices and the archive.5 As Indigenous peoples, it is often noted that we are both haunting and haunted by the archive, but it is our interpretation of the past and one’s embodiment of spiritual inheritances that can counter the ongoing violence of history and settler inscriptions. Across this body of work, Fielding has reclaimed and remapped imagery and the brand identities of missionary ephemera including The United Aborigines’ Messenger, a periodical published between 1929-1987 by the United Aborigines Mission, a Christian organisation that ran missions and children’s homes in South Australia, Western Australia and New South Wales. Not only is the intergenerational trauma of the Stolen Generation apparent in the inscriptions of Fielding’s images, but it is the counternarratives

arguing that culture continues, which is pivotal. The bold lettering has a quiet strength amongst the busyness of the background of each print and this, for me, is a clear sovereign form of resistance.

Some of Fielding’s newest work made for Tjukurpa Handle It, also reaches into unknowability in much the same way that it has been described by the Martinique-born poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant. In Glissant’s argument concerning one’s ‘right to opacity’, he strives to be ungraspable:

As far as my identity is concerned, I will not take care of it myself. That is, I shall allow it to become cornered in any essence; I shall also pay attention to not mixing it into any amalgam. Rather, it does not disturb me to accept that there are places where my identity is obscure to me, and the fact that it amazes me does not mean I relinquish it.6

In works such as Tutu 2022, (p.21) Tutu 2022, (p.93) Yalta 2022 (p.97) and Paralpi 2022 (p.19), opacity is embodied by Fielding’s technique of overpainting; his purposeful enshrouding of text to control the conditions of the viewer’s visibility. Across the works, landscape gives form to word, and word becomes landscape. But, as the scene is barely legible, our brains feel unsure of which should lead to fill in the void. We must decide if a letter is to become the contour of a mountain, or if a tree branch is just the shape of shadows. This element is key to anchoring viewers into a scene of tension where slippages of knowledge move between transparency and opacity; where Fielding is the grandmaster revealing and concealing sacred knowledge and that which should be kept from view. This is a fine example of how Fielding mobilises source material to regain control, to tell what is true.

Robert Fielding

Sovereignty over Country and all its riches, lies at the heart of Fielding’s practice. Fielding is well known for interventions made to found objects, as well as assemblages of these items into ambitious displays including Untitled 2018 or Holden on 2022. His works Kultuni (spear right through) 2021 (p.37, 49) extends this notion and responds to the non-consensual policing of Indigenous bodies and resource exchange through unequal power dynamics. Intent on rendering a claim of strength and resilience, Fielding edits the history of the object away from an uninvited colonial regime by literally spearing through the racist legacy of paying Indigenous peoples their hard-earned rations in only flour, sugar, or tea. Those who controlled the rations, controlled the narrative. The way in which Fielding restores these works is multiple: the sandblasted patterning of the objects reveals a beating transcription of the unknowable. As the artist himself explains:

In my home of Mimili Community, flour buckets are used daily to carry, store or hide many things. For one who knows how to look, the storylines of these buckets and their owners unfold throughout the landscape. When I sand-blast into the buckets with the very sand I find them resting on, I reveal the shiny surface beneath … Underneath the many responsibilities

Anangu carry today lies a resilient and radiant strength. It is with this strength we continue to carry culture and protect Country. 7

The kind of images that Fielding creates on each bucket speaks to the practice of milatjunanyi, which rejects and counters nineteenth and twentieth century legacies, reshaping a

European system of logic into one of Indigenous representation. This is not a completed action, instead it is one of becoming through the work interacting with the viewer.

Across his multimodal practice, Fielding makes art to see. Two lenses are overlayed, two worlds come together to create a united expression of reality. But we must look beyond the surface of his work. Central to Fielding’s practice is the use of storywork to tell of sovereignty and what exists in the in-between. Even if one does not understand culture, Fielding gives the viewer instruction on how to see the movement of times long past, and movement of times yet to come. His practice echoes the process of picturing the world, grounded in photography and printmaking, to tell stories that have been fixed to place since time immemorial as a counterpoint to what has been collected by the archive. Herein lies the power of Fielding’s work: he finds new ways to tell stories, bringing both the known and unknown into conversation every day.

Glossary

Anangu — Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara peoples Inma — song and dance Iriti kuwari ngula — past, present and future Kamuru — uncle Ku nt ili — auntie Milkali kutju — one blood Mama — father Marutju — uncle Mayatja — keeper/manager Mayatja pulka — senior keepers /bosses of culture Miil-miilpa — sacred Milpatjunanayi — to mark the earth with a stick/wire to tell a story

Ngunytju — mother

Stó:lō — ‘river’, specifically the Fraser River that flows through the heart of Stó:lō territory, Greater Vancouver area, British Columbia, Canada; or ‘People of the River’ Tjukurpa — ancestral stories Wirura kanyini — well looked after

Footnotes

1 Jo-Ann Archibald, 2001, ‘Editorial: sharing Aboriginal knowledge and Aboriginal ways of knowing,’ Canadian Journal of Native Education 25(1), p.1-5

2 Archibald, 2001, p.1

3 National Portrait Gallery, Kamberri/Canberra, 2022, Robert Fielding ‘Looking deep within the eye of a person’. [Online Video]. Available from https://www.portrait.gov.au/stories/robert-fielding [Accessed 24 June 2024]

4 Nici Cumpston (ed)., ‘Mayatja Pulka: The Elders,’ Tarnanthi, Art Gallery of South Australia, Tarntanya/Adelaide, 2017, p.26

5 See Natalie Harkin, 2014, ‘The poetics of (re) mapping archives: memory in blood’, JASAL: Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, 14(3), p 3; Léuli Eshrāghi, 2017, ‘MĀTAU ‘O TAUTUANAGA O FA’ĀLIGA ATA MO O TĀTOU LUMANA’I. Considering the Service of Displays for our Futures,’ Sovereign Words: Indigenous Art, Curation and Criticism, Office for Contemporary Art Norway / Valiz, p. 246 6 Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation ‘For opacity’, trans Betsy Wing, the University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbour, 1997, pp. 191-92.

7 Robert Fielding, ‘Tjalini. Lift or carry something heavy, carry a load, lug.’, 2019 artist statement. Available from https://maph.org.au/artworks/2155/ Museum of Australian Photography, 2024 [Accessed 1 July 2024]

Robert Fielding

First published in 2024 by Maitland Regional Art Gallery, PO Box 220, Maitland NSW, 2320, to accompany the exhibition

Tjukurpa Handle It: Robert Fielding

Exhibition Dates — 09 November 2024 — 09 March 2025

Gallery Director — Dr Gerry Bobsien

Gallery Deputy Director — Courtney Novak

Exhibition Curators — Robert Fielding, Gerry Bobsien

Exhibition Assistant Curators — Kim Blunt, Angus Webb

Foreword — Gerry Bobsien

Essay — Erin Vink

Artist Transcripts — Robert Fielding

Pitjantjatjara proofread — Anna Wattler, Robert Fielding, Angus Webb

Editing — Gerry Bobsien, Kim Blunt, Cheryl Farrell, Holly Farrell, Courtney Novak

Graphic Design — Clare Hodgins

Environmental Portrait Photography — Meg Hansen

Artwork Photography — Clare Hodgins

All images copyright of the artist

ISBN: 978-1-7636628-0-3

Printed in China by The Australian Book Connection

Robert Fielding would like to thank Creative Australia and Trent Walter / Negative Press for their ongoing support of his practice. He would also like to acknowledge long-term colleague and friend Angus Webb for his compassionate guidance and understanding for his process.

Mimili Maku Arts is in deep gratitude to the Elders whom created the foundations for new generations of artists to rise strongly on their country. Thank you to the Indigenous Visual Arts Industry Support Program for supporting the ongoing operations of the art centre.

Tjukurpa Handle It represents a partnership between Maitland Regional Art Gallery and Mimili Maku Arts. The work in this exhibition is on loan from the artist with curatorial assistance from Angus Webb.

Maitland Regional Art Gallery would like to recognise the support of our Publication Sponsor, the Gordon Darling Foundation.

Maitland Regional Art Gallery is a service of Maitland City Council and is supported by the NSW Government through Create NSW.

Robert Fielding

Robert Fielding