FOR MORE THAN A DECADE, the Fiskens stand at Retromobile has proudly showcased and sold some of the most significant collector cars of all time. Our 2025 stand celebrated the finest examples across both road and race cars, with many of the consignments offered from long-term ownership and publicly available for the first time. As we conclude another strong year of both on and off-market sales, we are now inviting consignments for our renowned Paris motor show stand. To have a confidential discussion regarding the sale of your classic automobile, please get in touch using the details below.

For many years Harris’s famous morning reviver was served over the counter as a remedy, post-revelry, for the roisterous and bibulous of London’s St James’s. With its tinctures of gentian, cinnamon, clove and ammonia, it was the head-clearing jolt needed to start the process all over again. Now, revived as a cocktail bitters, this new version of The Original Pick-Me-Up is no less effective, but a touch more palatable.

Centro Stile at 20, Eagle Lightweight GTR, Art of Bespoke, Tamiya legacy, IHMA news, Italdesign road trip, Generations Trophy and more

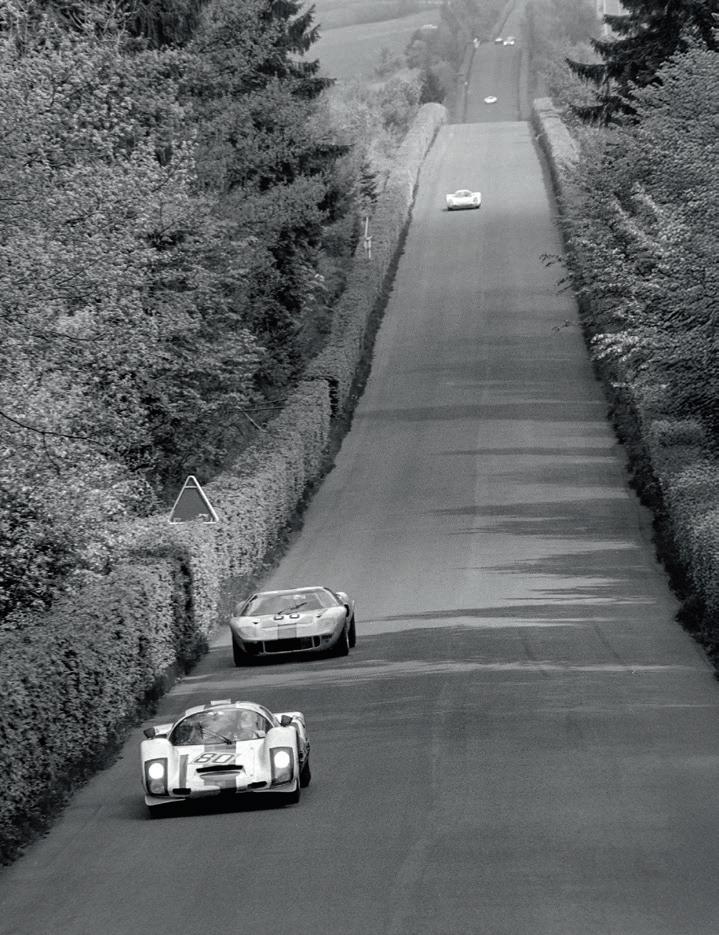

NÜRBURGRING: THE GREEN HELL

Buckle up for our breakneck drive through history, 100 years after work on the iconic circuit first began

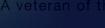

BAILLON FERRARI TAKES A BOW

Intriguing barn-find 1961 Ferrari 250 GT California Spyder with a Hollywood past is in the spotlight once more

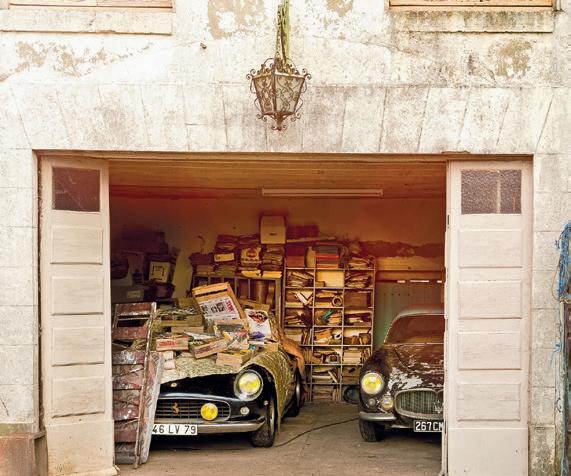

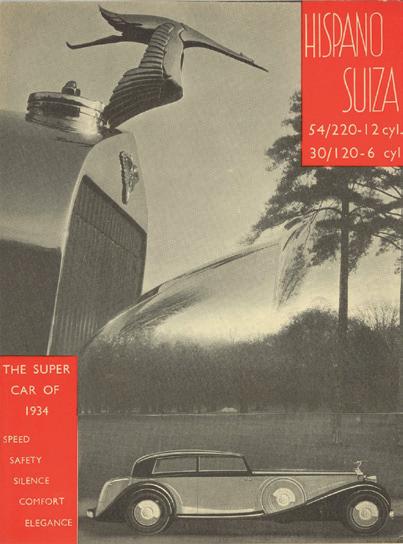

HISPANO-SUIZA POWER COUPLE

His ’n’ hers twins styled by ‘Dutch’ Darrin for Anthony and Yvonne de Rothschild will remain together forever

WACKY RACERS OF GRAHAM HILL

From single-seaters and sports-prototypes to fast saloons and motorised bathtubs, the motor sport legend drove it all

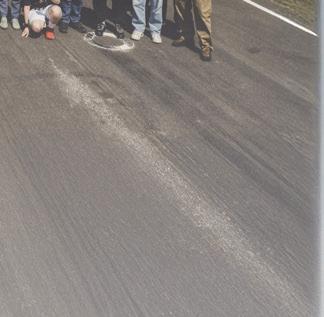

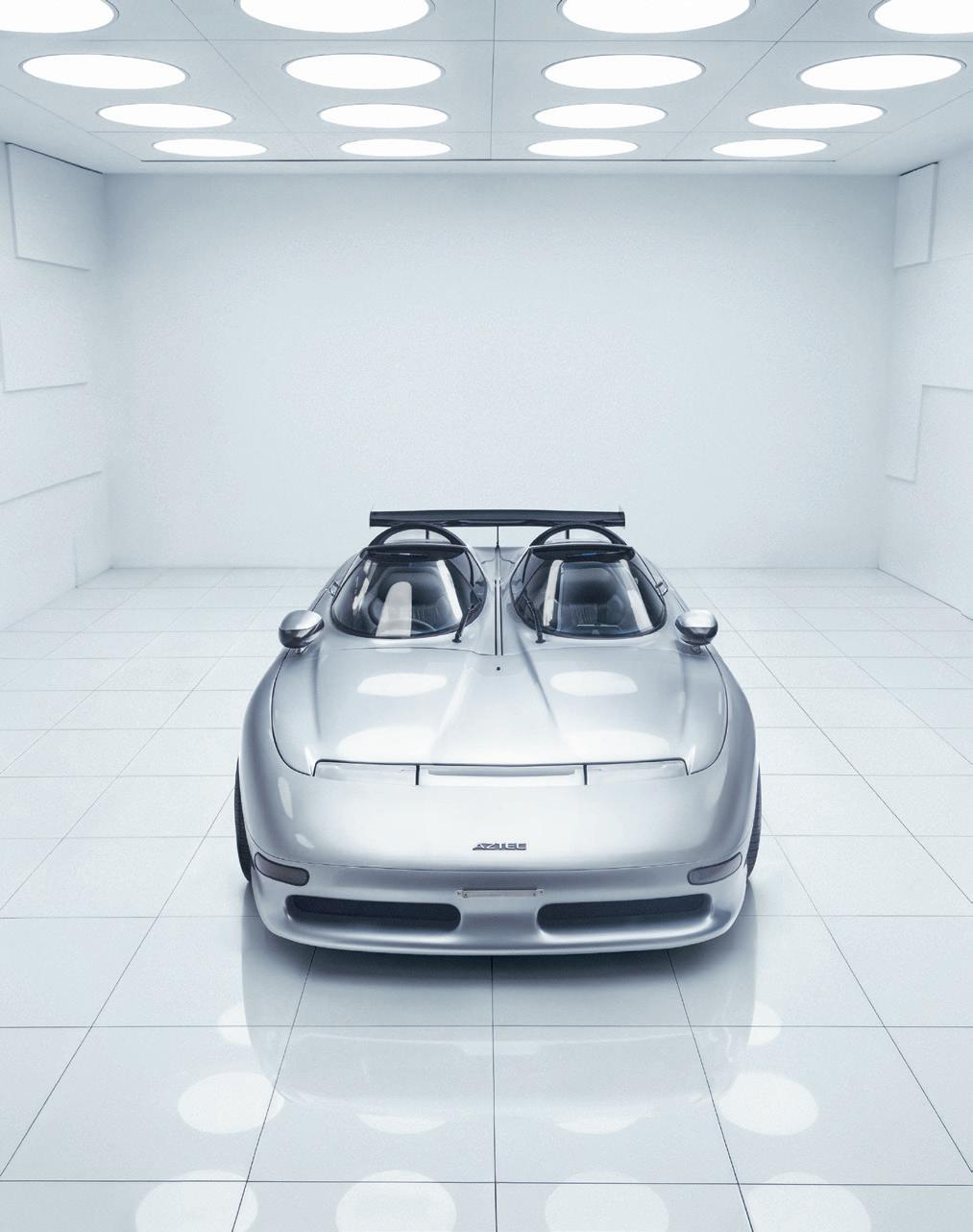

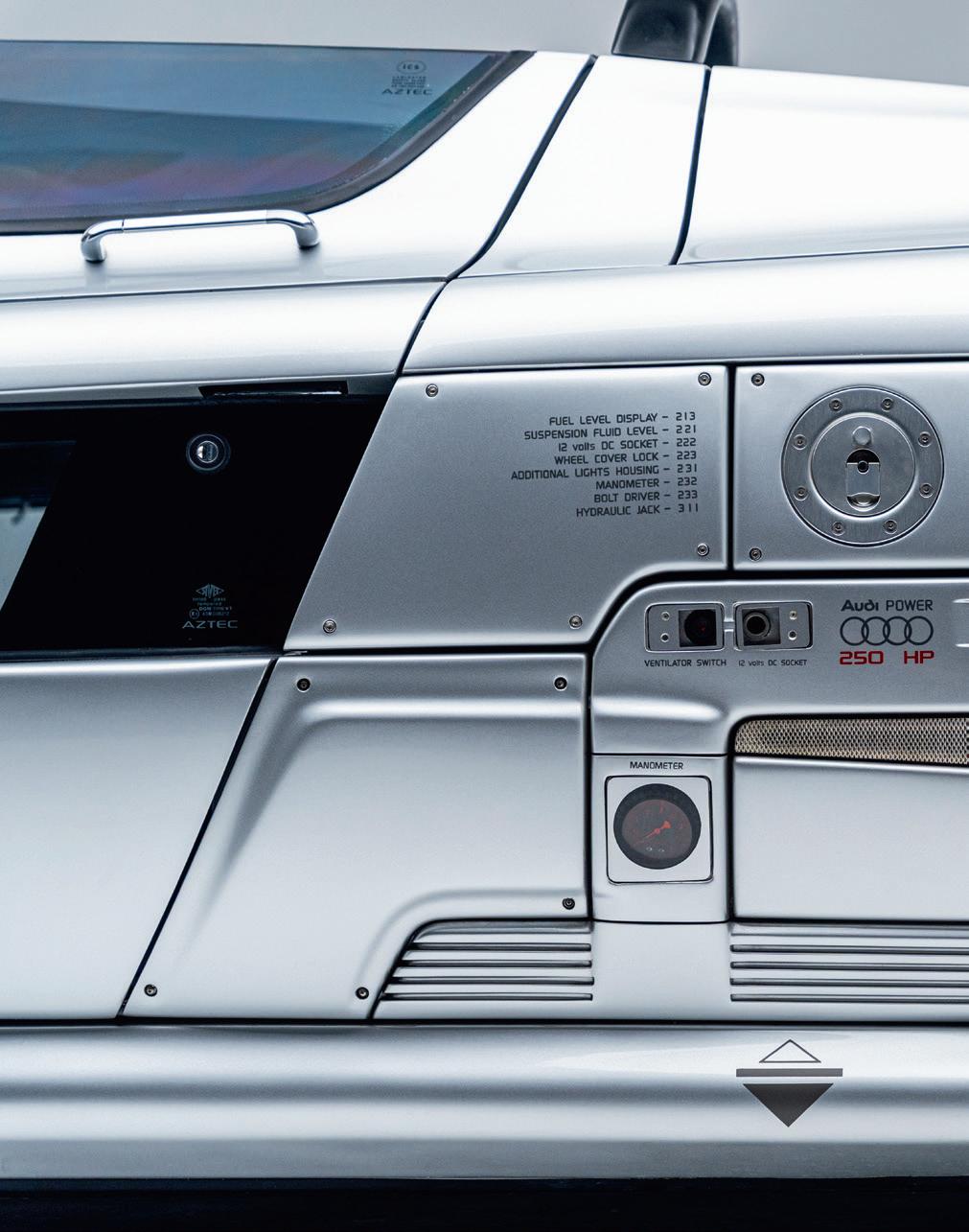

GIUGIARO’S 1988 AZTEC SHOW CAR

Sci-fi vision of the future was built to honour 20 years of Italdesign. It has never lost its space-age impact

SPADA: THE MAN, THE LEGEND

Father of the DB4 GT Zagato and Giulietta TZ was a beautiful, complex man who mainly let his designs do the talking

50 HOMOLOGATION SPECIALS

Creating a quota of road cars to legitimise a racing machine is a game of skill vs chance, as our Top 50 shows

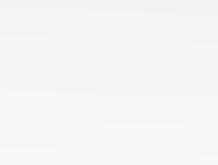

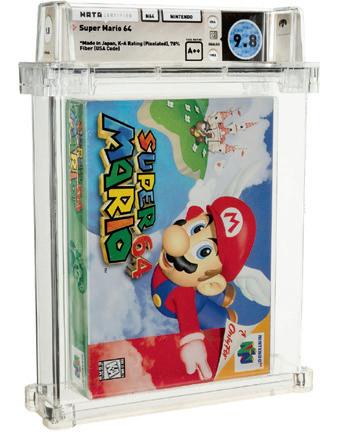

ACQUIRE

Buying a Porsche 914, collecting video games, automotive art by Joel Clark, Patek Philippe 3940 watches, products, book reviews and more

Estimate: $35,000 - $45,000

Many years ago, the late racer/writer Tony Dron gave me a copy of his ‘how to drive the Nürburgring Nordschleife’ notes. I studied them hard, and a few years later I was lucky enough to drive the Ring – at which point I forgot most of what I’d read and re-read so many times, and crawled around doing my best not to get in the way of the GT3s and M3s.

I’m willing to accept that I’m unlikely to race at the Ring now – and that I won’t be bothering the big boys on the Touristenfahrten days. But I still love the place for its history and atmosphere, and also for the surroundings; it’s often forgotten what a beautiful area the Nürburgring sits in.

That’s why we chose aerial shots to illustrate our feature celebrating 100 years since the first foundation stones were laid there. If you’ve never been, then go – even if it’s just to sit on the grass bank at Brünnchen to watch the tourist-lap antics or to sample the famous Pistenklause restaurants in Nürburg. They’re surprisingly good places to relax.

In stark contrast, we’ve had a busy few weeks in the run-up to our International Historic Motoring Awards event, but we have also found time to relaunch an old favourite: Vantage magazine. Back when MD Geoff Love and I were at Dennis Publishing with Octane magazine, we launched Vantage as an independent Aston Martin quarterly, but it was killed off after we left. It’s now back, and available on the Magneto website. If you like Astons, we think you’ll love Vantage.

David Lillywhite Editorial director

Art director, graphic designer, illustrator, part-time rally co-driver and Magneto favourite Ricardo is a perfectionist with an irresistible retro style and almost limitless creativity. Asked to create eight bird’s-eye views of Graham Hill’s most obscure race cars with little reference, he absolutely nailed it.

Belgian-based writer Bart, together with photographer wife Lies De Mol, produces and publishes automotive books with a heart and a unique style. A love for cars is one thing, but for Bart, connecting with the people behind them is the real reward – as shown in his piece on Ercole Spada.

A huge road-trip and Nürburgring enthusiast, Frank has written and published several books on these topics. During his travels, you will typically find him with two or three cameras around his neck, parked awkwardly alongside the road or racetrack, waiting impatiently for the perfect photo opportunity.

Classic and contemporary sports and racing car writer Richard has experienced everything from pre-World War One leviathans to hybrid hypercars. When we asked him to write about the 1988 Italdesign Aztec concept car, his response was: “Sure, I would love to. I’ve even driven one!”

Deputy editor

Wayne Batty

Marketing manager

Rochelle Harman

Editorial director

David Lillywhite

Creative director Peter Allen

Features writer

Elliott Hughes

Marketing and events

Hannah-Maria Ward

Managing director

Geoff Love

Managing editor

Sarah Bradley

Designer Debbie Nolan Accounts

Advertising sales Sue Farrow, Rob Schulp

Jonathan Ellis, Sarah Dilley

Lifestyle advertising

Sophie Kochan

Contributors in this issue

Advertising production Elaine Briggs

Frank Berben-Groesfjeld, Blair Bunting, Jonathon Burford, David Burgess-Wise, Nathan Chadwick, Robert Dean, Lies De Mol, Richard Dredge, Paul Fearnley, Martyn Goddard, Rob Gould, Rick Guest, Richard Heseltine, Georg Kacher, Evan Klein, Bart Lenaerts, John Mayhead, Clive Robertson, Ricardo Santos, Damien Smith, Dean Smith, Peter Stevens, Nick Trott, Joe Twyman, Matt Walford, Gary Watkins, Greg White, Rupert Whyte

Single issues and subscriptions

Please visit www.magnetomagazine.com or call +44 (0)208 068 6829

Geoff Love, David Lillywhite, George Pilkington

Unit 16, Enterprise Centre, Michael Way, Warth Park Way, Raunds, Northants NN9 6GR, UK

Printing Buxton Press, Palace Road, Buxton, Derbyshire SK17 6AE, UK.

Printed on Amadeus Silk and Galerie Fine Silk supplied by Denmaur as a Carbon Balanced product. Made from Chain of Custody certified and traceable pulp sources

Who to contact

Subscriptions rochelle@hothousemedia.co.uk

Events hannahmaria@hothousemedia.co.uk

Business geoff@hothousemedia.co.uk

Accounts accounts@hothousemedia.co.uk

Editorial david@hothousemedia.co.uk

Advertising sue@flyingspace.co.uk or rob@flyingspace.co.uk

Lifestyle advertising sophie.kochan2010@gmail.com

Advertising production adproduction@hothousemedia.co.uk

Specialist newsstand distribution Pineapple Media, Select Publisher Services

In 2015, we watched the Baillon 250 GT California Spyder – once owned by French star Alain Delon, later left to rust at a French chateau – sell for a record €16.4m. Last month we photographed it, now perfectly restored, at the equally immaculate Kiklo Spaces. We’re lucky enough to see a lot of special cars, but this beautiful Ferrari sent shivers down all of our spines.

Ercole Spada, who died earlier this year, was a surprisingly quiet, humble man. Getting to know him wasn’t easy, but when writer Bart Lenaerts and photographer wife Lies De Mol inadvertently gatecrashed Spada’s 71st birthday party in 2008, they made a friend for life. In this issue, Bart explains how the relationship with the designer developed over the years.

© Hothouse Media. Magneto and associated logos are registered trademarks of Hothouse Media. All rights reserved. All material in this magazine, whether in whole or in part, may not be reproduced, transmitted or distributed in any form without the written permission of Hothouse Media. Hothouse Media uses a layered privacy notice giving you brief details about how we would like to use your personal information. For full details, please visit www.magnetomagazine.com/privacy.

ISSN Number 2631-9489. Magneto is published quarterly by Hothouse Publishing Ltd. Registered office: Castle Cottage, 25 High Street, Titchmarsh, Northants NN14 3DF, UK.

Great care has been taken throughout the magazine to be accurate, but the publisher cannot accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions that might occur. The editors and publishers of this magazine give no warranties, guarantees or assurances, and make no representations regarding any goods or services advertised in this edition.

Do you remember Vantage, the independent Aston Martin magazine? Magneto founders Geoff Love and David Lillywhite co-founded it years ago, but it was killed off when they left Dennis Publishing. Now it’s back, put together once again by Peter Tomalin and Dickie Meaden – and it’s as good as ever. Order it at www.magnetomagazine.com/store

Magneto’s Weekly Briefing is a curated regular package of the news, features, event reports and previews that matter most to classic and collector car audiences. Our fortnightly Market Briefing newsletter previews upcoming events and adds expert analysis of auction results and prevailing market trends. Sign up at www.magnetomagazine.com

The Magneto website reflects our love for the very best, the rarest and the most special production, prototype, competition and concept cars of every age. For all the news,

You can subscribe for one year for £54 including p&p (€62 or $68, plus postage), or two years for £94 including p&p (€108 or $120, plus postage). Magneto is delivered worldwide in strong cardboard packaging. Please visit www.magnetomagazine.com or call +44 (0)208 068 6829.

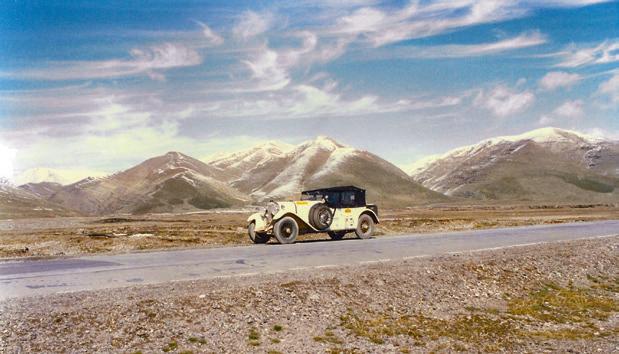

Offered for sale

1926 Rally Grand Sport ‘S‘

Painstakingly restored over seven years, this sole surviving Grand Sport S is a masterpiece in preservation.

Unrepeatable opportunity.

£90,000

www.tomhardman.com ask@tomhardman.com

+44(0)1200 538866

At a party celebrating two decades of style autonomy, Automobili Lamborghini revealed a new design. Bang on brand, the Manifesto was something ‘unexpected’

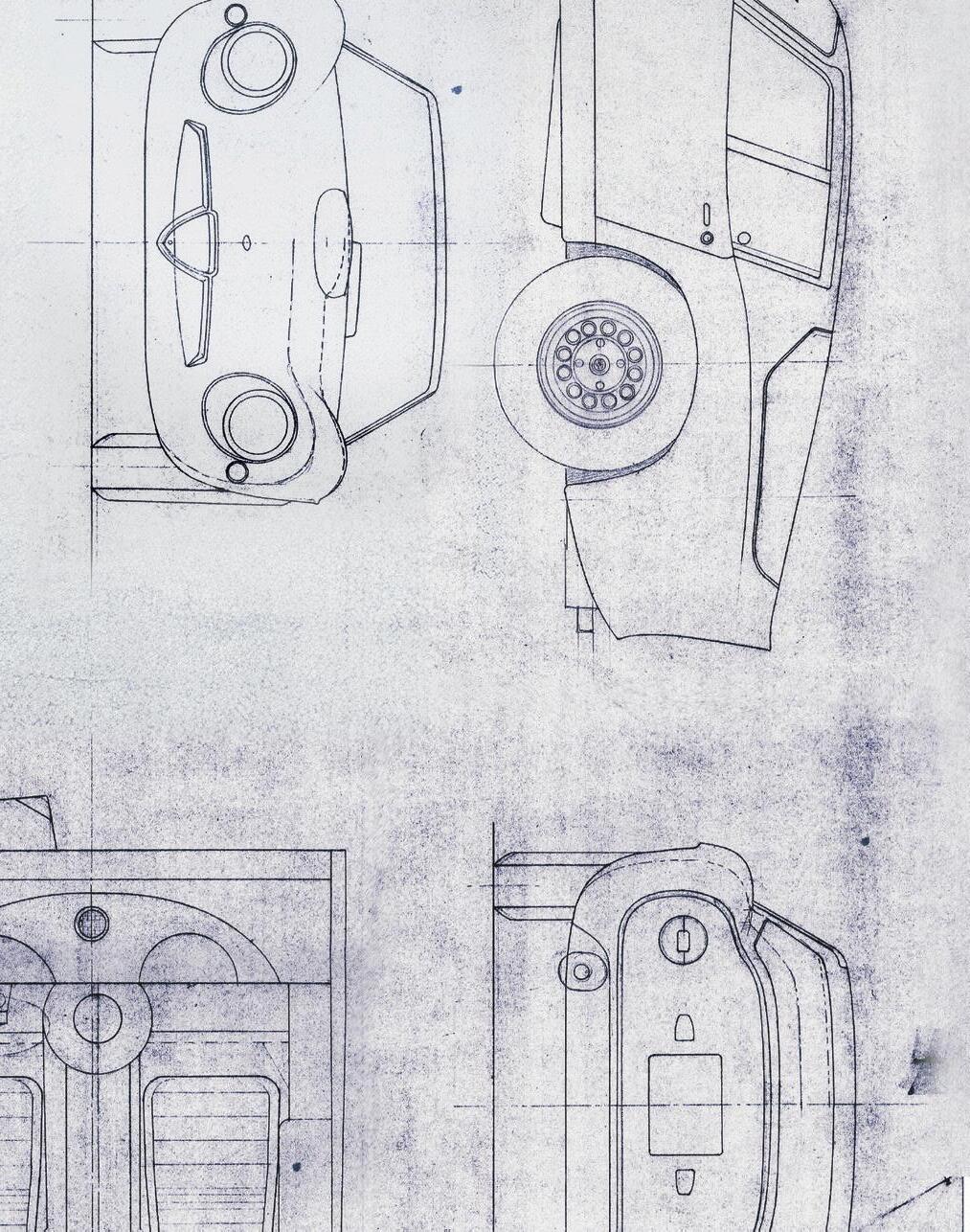

THIS SPREAD Design director Mitja Borkert’s tape skills are as sharp as the cars emerging from Centro Stile.

FEW WOULD ARGUE THAT THE core tenets of Automobili Lamborghini are performance engineering and design. While the cars have always incorporated exhilarating technical and mechanical specification, it’s their external designs that have really set pulses racing. Chairman and CEO Stephan Winkelmann readily acknowledges that “design is fundamental to all that we do”. From its genesis back in 1963, the Italian super-sports car manufacturer has consistently delivered models that are among the most visually arresting on the planet. This is principally, but not exclusively, epitomised by the astonishing and enduring impact of the 1971 Countach LP500 concept.

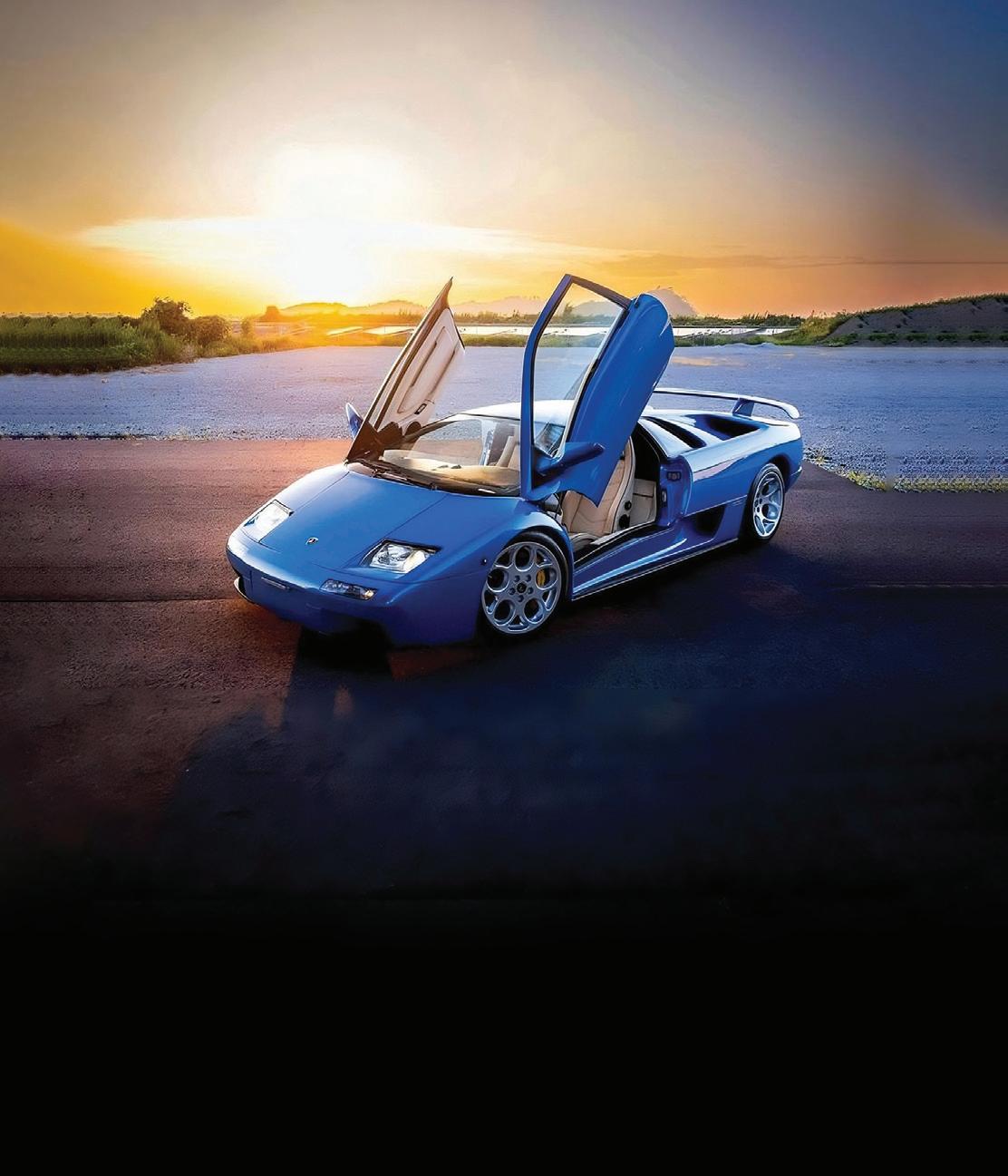

While all the early Lamborghinis were shaped by external styling studios (mostly Stile Bertone), models such as the 1981 Jalpa and 1986 LM

002 were designed by Lamborghini’s then technical director Giulio Alfieri. Under Chrysler ownership, Marcello Gandini’s P132 Countach replacement proposal morphed into the polished but still menacing Diablo courtesy of a thorough rework by Chrysler Styling Center’s Tom Gale.

Beneath the bravado, though, those years were difficult for the car maker. Volkswagen Group’s purchase of Lamborghini, and the supercar company’s subsequent positioning as an Audi Group subsidiary in 1998, brought the kind of stability and technical resource that authentic creativity thrives on. Joining from Audi, the uber-talented Luc Donckerwolke was charged with taking Lamborghini beyond the Diablo. He absolutely nailed that brief, creating the beguiling Murciélago in 2002, followed in 2004 by the V10-engined Gallardo

THIS PAGE It’s a Lamborghini tradition to deliver the ‘unexpected’. The Manifesto was certainly that – but outside, Centro Stile surprised all by displaying its never-before-seen Countach concept.

that then outsold all Lamborghini’s previous models combined.

It was incoming Audi Group design chief Walter de Silva who, in one of his first meetings with Group head Martin Winterkorn, pushed for the creation of an in-house design division at Lamborghini. In the early 2000s, the go-ahead was given to convert one of the company’s old car-storage areas into a new design studio, becoming fully operational as the Lamborghini Centro Stile in 2005. From that milestone moment on, every design decision would be made internally, thus ensuring full ownership of the brand’s creative voice and its future legacy.

After two prolific decades of extraordinary product creation, first under Donckerwolke and then in the care of Filippo Perini, incumbent design boss Mitja Borkert championed the idea of a 20th anniversary celebration of the Centro Stile. He had an enthusiastic buy-in from chairman and CEO Stephan Winkelmann.

Current and former Lamborghini designers, industry friends and a handful of media were invited to the event. On the agenda was an intriguing, mostly ‘unscripted’ Q&A session with de Silva and Borkert; an eye-popping display of the facility’s extraordinary concept cars, special editions and few-offs; and a wildly desirable sculptural statement of future intent, aptly named the

Lamborghini Manifesto.

Walter de Silva may sound a little frail these days, but an entertaining panel discussion inside the Centro Stile presentation area proved he’s lost none of his design fire. A few off-piste comments about the wider industry kept Lamborghini head of communications Tim Bravo on his toes. While discussing aspects of design, de Silva said European brands had “become followers of the copiers”, and put the blame firmly on weak leadership for the sad state of some heritage-rich (Italian) brands. Back on subject, he revealed that he’d admired Borkert’s “energy” at Porsche.

He recalled that in a meeting one night after the 2015 Frankfurt Motor Show, he’d simply said: “I want you for Lamborghini.” Ten years on, de Silva, voice cracking with pride, told the audience: “In Mitja, I found the right person.” Then, before anyone got too comfortable, he added that while much has changed at Centro Stile over the years – the design team has mushroomed from seven in Perini’s time to 25 now – “the next step is more. It is not enough”. To be 74 years old and yet still be encouraging those around you to push boundaries is remarkable.

Winkelmann himself said he expects Centro Stile to be “always pushing boundaries to deliver the unexpected that is so innate within the Lamborghini marque”.

For his part, Mitja Borkert appears

Fifty years

Despite advocating for cutting-edge tech, Borkert is still a sketch fanatic.

tailor-made for the role. “We must be open to embracing the developments of the next 20 years,” he said. “We are looking at AI, of course. I am the oldest one in the design centre, but I was the initial driver of this [exploration into AI]. Now the whole team understands its importance as a tool. The principles of Lamborghini Centro Stile mean we must always be curious, questioning the status quo.”

Arriving from Porsche in 2016, mere months after the unveiling of Stuttgart’s Mission E concept car, his first task was to finish the series Urus before its imminent design freeze. As the new design director, however, he also felt the need to deliver something crazy and unexpected – “to show all the enthusiasts that I understood the brand and was in no way going to do a Porsche out of Lamborghini”. Developed in 2017 with MIT, the extraordinary Terzo Millennio ‘third millennium’ electric concept car conclusively proved Mitja’s innate understanding of the brand’s traditional ability to deliver the shock of the new. The Terzo Millennio was never designed to be a real car – it was just too extreme. However, details such as the Y-shaped front DRLs, the hexagon in the body side and the rear shoulderpanel shape have over the past eight years inspired similar elements in the Revuelto, Temerario and Essenza SCV12 track car. Other Borkert highlights include the Sián, Countach LPI 800-4, Lanzador concept and the recently revealed Fenomeno. This celebratory event offered a chance to inspect absolutely all of these machines, and so many more.

The facility’s internal approach

road to the reception and the museum areas was littered with Centro Stile treasures. The line-up – one that is not likely to be seen all together on Tarmac ever again – included Donckerwolke’s two aforementioned marvels and his under-appreciated 2006 Miura concept; pinnacle examples of Perini’s production Aventador and Huracán and few-off models, the Reventón, Sesto Elemento, Centenario and Veneno, along with his much-admired 2008 Estoque, 2012 Urus and 2014 Asterion concepts.

A never-before-seen Countach concept developed by Borkert’s team prior to 2021’s LPI 800-4 was a genuine Easter egg. It drew universal praise from the attending motoring writers, which was certainly not the case when the limited-production car was first revealed. Mitja’s insight into the concept’s crucial airflow woes –serious lift and insufficient cooling issues – went a long way to explaining why so much was lost in the translation to showroom-ready machine.

Drinks and cocktail party small talk were in abundance on the ground floor of the company’s relatively intimate museum area, which was decorated with the 2013 Egoista, Terzo Millennio and 2019 Vision Gran Turismo concepts. Upstairs, the main surprise awaited. Alongside styling models of the 1971 Countach and the brand-new Fenomeno, and still cloaked in a black fabric shield, stood the next step in the evolution of Lamborghini’s design DNA.

In anticipation of a formal interview with Mitja the following day, I had planned to quiz him on design purity, cleaner surface treatments and the reduction of visual clutter. Acknowledging that Lamborghini sets trends, not follows them, surely he’d still noted that some of the most impactful concept cars of the year had trumpeted a return to a clinically pure – in some cases brutalist – design aesthetic. I’d also hoped to ask how much scope could possibly be left to develop the Countach theme, given that Borkert’s own wonderful design evolution sketches reveal how the simple purity of the 1971 concept has been taken to almost chaotic extremes. As the black cloth was whipped away, a startling wheeled

‘Guided by the Manifesto, it feels as if Centro Stile’s design engine is only just beginning to fire’

sculpture rendered in neon chartreuse was revealed. In an instant, I knew I’d need a new set of questions.

Centro Stile’s breathtaking new Manifesto represents an unadorned return to the shocking purity of the LP500 concept. Crucially, though, there’s not one square millimetre – or one pixel – that could be termed a retro pastiche. Placed near each other in the cold light of the following day, the LP500 still had the shock factor of a UFO, and yet the Manifesto’s exaggerated sculptural volumes were even more dramatic.

After we had found a quiet corner, Borkert told me the search for a new purism goes back several years to a project he oversaw involving an intern and another designer. They sought

something the opposite of the Terzo Millennio: “So, not full of elements, but a removal of elements.” The Manifesto sculpture was born from that idea. “It’s a shape that Stephan Winkelmann also likes a lot – but that doesn’t mean everything from now on will have always clean and always puristic shapes.”

So, while the Manifesto is a declaration of intent, it is definitively not the final design of the next car – it will not, and realistically cannot, be produced in this form.

“Cars with large-capacity V12s require huge cooling inlets for radiators, which means this kind of purism is not possible at the moment with these engines,” said Borkert. The car was instead created to guide the language of the brand in the years ahead. Just as the Terzo Millennio did before, the Manifesto is a new reference point for future Lamborghini models.

“When I joined Lamborghini, looking at the Miura and the Countach, I already understood that purism is part of the design legacy here. Everyone perceives the Countach as an ultra-extreme car, but the first LP500... there’s no wing, there are only puristic shapes. So, I understood

immediately that this is the starting point for our design DNA.”

For Lamborghini, the Gandini/ Bertone Countach is an enduring gift. It is the marque’s design language distilled to its very essence, an unmistakable guiding profile. Detail elements, the hexagon and the Y-motif – taken from the intersection of nested hexagons (the honeycomb) –were added decades later, inspired by the 1967 Marzal concept, but it’s the dramatic profile of the Countach that remains the starting point for every new Lamborghini.

Alongside the previous evening’s anniversary cake, Lamborghini had set up a large blackboard canvas for all to leave their thoughts and sketches. It was telling that at least four designer depictions of the Miura appeared, proving the car’s popularity among the Centro Stile crew. If Lamborghini design DNA starts with the 1971 Countach, what role does the Miura, seen by many as one of the most beautiful cars ever, actually play?

“The Miura is a standalone design – one of several standalone Lamborghinis,” replied Borkert. “Take the Espada for example; it was born from the Marzal. For me, they’re always important for all the hexagons and because of the general shape. It’s a wonderful design, but it’s also a standalone design, and as we always state: we look into the future.”

In this regard, Borkert said that the basic structure of Centro Stile is advanced design, production design, feasibility design – not operating as three separate silos, but rather “more like a garage band” jamming away together. In addition, he has also established what he calls a “crazy corner: a small group within Centro Stile tasked with imagining Lamborghini 20 years from now”.

Taken from the official release: “Twenty years after its foundation, Centro Stile Lamborghini is more than a design studio. It is a laboratory of imagination.” Easy to disregard that as mere marketing puffery, but judging by what has already emerged, listening to Borkert say that “Lamborghini is still like a start-up” and guided by the mesmerising Manifesto, it feels as if Centro Stile’s design engine is only just beginning to fire.

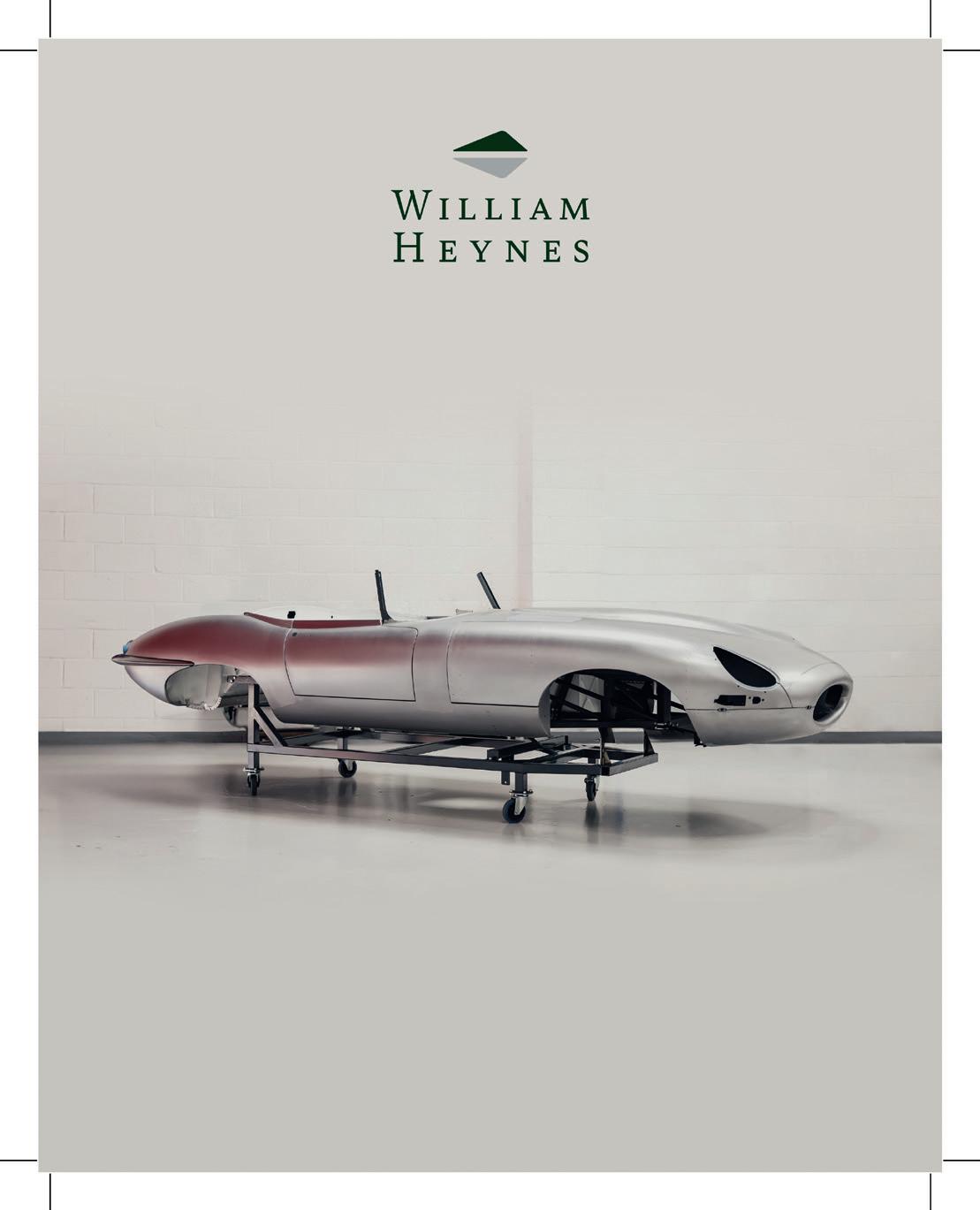

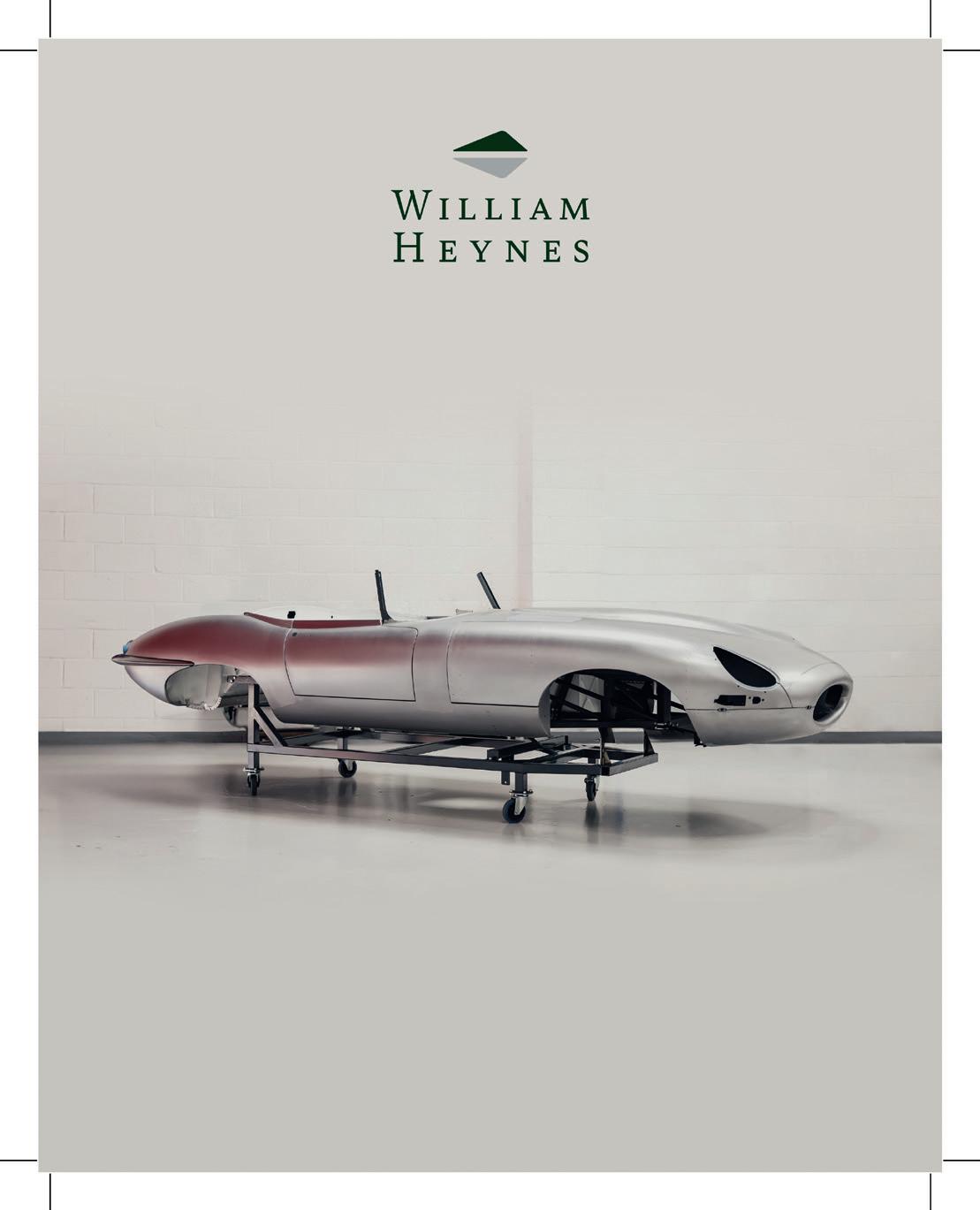

Even Eagle E-types’ own engineers didn’t think its alloy-bodied Lightweight GT could lose this much weight and remain civilised

SPECIAL-BODIED E-TYPES DON’T come along often from Eagle – but when they do, we sit up and take notice. We’ve driven them all over the years, and this car is the very latest.

A bit of background for you: irrepressible E-type obsessive Henry Pearman started Eagle in 1984 and created his first upgraded restoration in 1991. Eagle now restores four E-types a year to bespoke specification. These cars are fully re-engineered and upgraded for much-improved driving, comfort and performance, but they retain the original bodystyle and the six-cylinder XK engine.

In 2008, one customer asked for something extra special, though; this ended up as the alloy-bodied, opentopped Speedster, on which no single panel was the same as an original. That was followed by the equally bespoke Low Drag GT, the Spyder GT and then – in 2019 – the Lightweight GT. That last one is, as the name suggests, Eagle’s road-going take on the 12 race Lightweight E-types Jaguar built for racing in 1963 and ’64.

The Works cars were all Roadsters fitted with a hard-top, roof and boot vents plus centre-lock wheels; Eagle’s Lightweight GT has the same styling cues but the rear bodywork is curvier, the front and rear screens more steeply raked, the hard-top better integrated and lower profiled, the pegdrive wheels larger and wider, and the running gear seriously upgraded.

The first Lightweight GT, which we drove for Magneto issue 7 in 2020, weighed 1017kg (2242lb) – around 30 percent lighter than a standard E-type Roadster. The thinking at the time was that Eagle’s neat air-conditioning fitment would have had to be sacrificed to get the Lightweight GT under 1000kg (2204lb). We loved it.

However… one customer then challenged Eagle to build a Lightweight GT with a little more of a race feel,

although it still had to be usable on the road. It also had to have air-con, triple Weber carbs, the D-type wideangle, big-valve cylinder head, racetype cut-out switches and an exposed alloy fuel cap... and it absolutely had to come in at under 1000kg.

Challenge accepted! Eagle set about reducing the weight, from an already premium spec that included optional magnesium rear hub carriers, sump, bellhousing, gearbox and diff casings, plus tubular rear wishbones, Inconel manifolds, titanium exhausts, hollow driveshafts and a lithium battery.

To those were added specially developed titanium wheel hubs and carbon-ceramic brakes, lightened versions of Eagle’s magnesium rims, alloy seat shells, honeycomb material in place of plywood for the boot floor and almost countless titanium and drilled or cut-down components.

The result? An incredible 930kg (2050lb) dry or 975kg (2150lb) with fluids. And does it make a difference?

Well, over a stock E-type the newcomer is light and dark. It’s much, much quicker, it steers, rides and stops in a different league, its fivespeed ’box makes for far better cruising and it sounds like... heaven. A rather noisy heaven, admittedly.

Compared to that first Lightweight GT we drove, Eagle MD Paul Brace says it’s discernibly more compliant and responsive – but without driving them back to back I can’t comment on that. It will rev higher, though, due to using titanium connecting rods in the bored and stroked 4.7-litre 400bhp engine; with the lighter weight, this makes the model feel even more potent. For these reasons, this car, the third Lightweight GT built, has now gained an ‘R’ to its name and a significant premium on top of the usual £950,000 price. It would be difficult to imagine a more exhilarating E-type on the road. More details at www.eaglegb.com.

‘It would be difficult to imagine a more exhilarating E-type than the GTR on the road’

As we look forward to 2026, let’s reflect on 50 years ago when a raft of ‘cars of the future’ promised radically different takes on things to come. But how did they pan out?

The dream

In the wake of the fuel crisis and under pressure from European and Japanese small-car imports, General Motors tried to reverse its reputation for thirst as well as create a vision of future domination and patriotic pride. By this time market share had slumped to 42 percent, a post-war low.

The utopia

The dystopia

The reality

Buying one

Marshalling the smallcar know-how of the GM empire via Opel and GM Brazil, the T-Car project was brought to shores the parent company never intended. Rear-wheel drive and a solid back axle weren’t novel, but a single overhead camshaft and progressiverate rear springs were.

This car was glacially slow, while Ford’s Fiesta and Volkswagen’s Golf exposed how US development had dulled the Opel/Vauxhall

A radical vision that would transport plutocrats in futuristic style while also generating enormous profit margins to dig Aston out of its latest financial mess.

The 5.3-litre V8 had plenty of oomph and the interior was luxurious in a way only a Rolls-Royce could challenge. William Towns’ controversial wedge styling was widely criticised, but it worked – Aston received a flood of deposits.

That was the easy bit – but integrating the electrics swallowed the entire development budget, and even then Aston Martin still needed NASA’s help to get them working. Often even this wasn’t enough.

Although 2.8 million were sold, the Chevette gained a stigma – if you failed in life, it would be the car you drove.

For just $4000 you’ve got one of the most fascinating folk tales in Detroit history – and a sure-fire entry to the Concours d’Lemons.

Rover had arguably created the junior sports saloon with the P6, tapping into the young managerial class. The SD1 was a sharper-suited, futuristic successor aimed at those same customers, now in upper management.

David Bache’s aesthetics may have been inspired by the Ferrari 365 GTB/4 and GTB/C, but the general vibe came via the funky Citroën CX of 1974. Why couldn’t the Brits do modernism, too?

A bold vision of what luxury could be, wrapped in Pininfarina couture. Aldo Brovarone’s coupé was a sexy take on the wedge motif, but Leonardo Fioravanti’s ‘saloon’ was arguably more radical – a big luxury hatch shape, even more so than the SD1 and CX.

The Gamma was also front-wheel drive, which was still relatively novel in the luxury-car segment. Its engine eschewed six-cylinder and V8 class convention in favour of a longitudinally mounted flat-four powerplant.

Let’s play 1970s British car bingo. Cost-cutting, shortcuts in development, shoddy materials and poor assembly... even the press cars were abysmal.

More than 600 Lagondas were built over 14 years, often with hugely expensive bespoke interiors and, sometimes, taste-challenging exterior treatments. A useful profit centre for Aston Martin, as intended.

The ultimate curate’s egg – one UK fan has around 30 – an excellent Lagonda costs £68k-£77k reckons Hagerty.

And yet... just look at it. It still looks like a vision of otherness. Most survivors today have been dutifully cared for. Get a good one and it’s a revelation to drive.

The engine had a fatal flaw – apply too much load on the power-steering pump and the timing belt could skip or snap. Cue a toasted motor. And then there was the body rust...

Hagerty says an early V8 SD1 costs £7500, a later Vitesse more like £14,000. The rare Twin Plenum homologation special is more.

You’ll never tire of gazing at the coupé’s concave bootlid, while the interior is a deeply comfortable place to waft

suggests £5600 for the Gamma saloon and £11,000 for the coupé.

THUR 29 JAN I LIVE AUCTION

PARIS EXPO

PORTE DE VERSAILLES

OFFICIAL AUCTION HOUSE OF RÉTROMOBILE

Featuring Selections from THE CHERRETT COLLECTION Offered Entirely Without Reserve

1928 ALFA ROMEO 6C 1500 MILLE MIGLIA SPECIALE

Coachwork in the style of Zagato I Chassis 0211409

1928 ALFA ROMEO 6C 1500 SPORT ZAGATO

Coachwork by Zagato I Chassis 0211501

1929 ALFA ROMEO 6C 1750 SS LE MANS

Coachwork in the style of Zagato I Chassis 0312917

MARCH 5 – 6 LIVE AUCTIONS

1989 RUF CTR ‘YELLOWBIRD’ SOLD for $6,055,000 Amelia Island Auctions 2025

Photography Ricardo Wiesinger

Meet Professor Friedhelm Loh, German billionaire, car enthusiast extraordinaire and founder of the country’s remarkable Nationales Automuseum The Loh Collection

WHILE WE WOULD AGREE THAT switch-cabinet construction doesn’t sound like rocket science – more of a ‘Tom, Dick and Harry’ job – Friedhelm Loh turned his father’s business into a licence to print money.

The high-voltage electrician not only did a better job than any rival, he also offered his products at lower prices. Going from strength to strength, he built a multi-brand empire that currently employs more than 12,000 people and made Loh one of the richest men in Germany. His personal fortune was recently pegged by Forbes at a whopping $13.9 billion.

But when I first met the master of the house, the person at the other side of the office table was not your generic aloof and standoffish captain of industry. Quite the contrary: the 79-year-old self-made entrepreneur turned out to be a jovial and totally unpretentious, down-to-earth car guy with an open face, attentive eyes and

THIS SPREAD Friedhelm Loh’s passion for cars spans from motor sport legends to classic icons and hightech concepts.

a grid of deep laugh lines. It was only two years ago that he made his phenomenal collection public by opening the Nationales Automuseum in the village of Dietzhölztal halfway between Frankfurt and Cologne.

The 160-plus exhibits on display (only ten of them are on loan) in a majestic converted historic steel mill may be the owner’s pride and joy, but as with so many high-end collectors, Herr Loh rarely takes one of his valuable classics out for a spin.

As he recalls: “The very first Bugatti Veyron, an early prototype, taught me a lesson. We drove it to Holland for a long weekend and had a blast, but a few days later the local papers ran pictures of ‘the multi-millionaire who is spending big on toy cars’. Although a senior shop steward congratulated me on my purchase, this kind of PR can easily backfire.

“Be that as it may, I still occasionally potter up and down the high street in

a Bentley 8 Litre or Mercedes SSK, both of which are permanently registered. My favourite daily drivers are a modern Maybach saloon and the G63 AMG in winter. I am not overly happy with the new SL, though –and I told [Mercedes-Benz CEO] Ola Källenius so when he last paid us a visit in his dual role as classic car enthusiast and senior fleet salesman.”

Loh has been a Merc man since his childhood days when a family friend pulled up in a chauffeur-driven silver 190 SL with a blue top and trim. Sure enough, the young boy was instantly hooked – first to this particular model, then to the brand. It was only logical that in the mid-1980s a white W 121 marked the foundation of what is now one of the world’s most significant classic collections. A blue-over-silver specimen was acquired at a later stage.

For many years, the patron would exclusively focus on vehicles wearing the Three-Pointed Star, but on a whim he fell in love with Bugatti, and after that the walls came down: “I now know that technology is what fascinates me most. Design is important, and so is craftsmanship, but to me the number one priority is engineering excellence that forms the backbone of innovation. The museum can, for instance, bridge the gap from one of the very first hybrids – the Lohner-Porsche Mixte – to the relatively recent, fully electric Mercedes SLS eDrive.

“We can also tell the full story of the head-up display, starting with the very first fully mechanical version pioneered by Ford for its 1956 Thunderbird. Or how about reeling back through time from the latest Mercedes-AMG One to the 1895 Benz Victoria that had only two owners:

the Benz family and Henry Ford.”

The Loh Collection is a well oiled commercial enterprise that employs 80 people, including a trained mechanic and four retired classic car specialists. A satellite of the Nürtingen-Geislingen University, it also offers training programmes for young people, who can graduate as Masters of Engineering and Certified Experts for Car Design and Historic Cars, aka appraisers. The vast building complex houses a period cinema, a US-style diner and a bunch of high-tech simulators.

“But this is only the beginning,” quips Friedhelm. “We’re in the process of setting up a hotel, and by 2035 the aim is to significantly increase the

‘Although I rarely buy on impulse, my top-secret wish-list is by no means complete’

exhibition space from today’s 7500m2 footprint, a move that will hopefully at least double the number of visitors from 100,000 to 200,000 per year. There are more cars in storage to fill the new open spaces, and although I rarely buy on impulse, my top-secret wish-list is of course by no means complete.” Big smile, change of subject.

As with most collectors, Professor Loh rarely talks money and likes to play his cards close to his chest. Is it true that he refused to buy a Bugatti Royale even though the price had dropped twice by several million Euros, simply because the selling party wasn’t playing straight? No comment.

“All I can say is that there is no fixed strategy, no firm game plan, no routine execution,” he says. “Sometimes I use an agent or a personal contact I trust, sometimes we buy at auction, sometimes cars change hands quietly among collectors. Occasionally I unearth myself what I’m looking for in the classifieds or online. Mercedes, Porsche, Ferrari and Bugatti are the marques I find particularly appealing, but I also love older American cars, post-war English brands and anything Italian that is pretty, clever and rare.

“Would I spend €50m or €60m on a Ferrari GTO? That’s a lot of money compared to a very good SSK that can be had for €12m-€17m, not to mention relative steals such as the BMW 507 or the evergreen 300 SL. But the times are changing, and the focus has long shifted from pre-war behemoths to relatively modern classics including super- and hypercars. Our exhibition mix should reflect this trend and put a stronger emphasis on state-of-theart, high-tech machinery.”

It is important to Friedhelm L that the core collection and the special

exhibition that is in place for only one year contain enough ‘lollies’: surefire head-turners and crowd magnets that keep the museum going and the cash register ringing. The number one smartphone target? Wrong. The most popular vehicle on display is the littleknown Maybach Exelero concept that never even made it into production.

Also high up on the list is anything painted rosso corsa, championshipwinning race cars including the iconic Porsche 956 and ultra-rare time capsules such as the unrestored Talbot-Lago T26. For political reasons, vehicles that are in any way related to World War Two are denied floor space.

“Although it is nice to have a hall full of red Ferraris, it is just as important to display a set of cars that have a story to tell,” reckons the architect behind this €1 billion (conservative guesstimate) motor museum. “Check out, for example, our Lincoln Continental – the last car President Kennedy rode in before his assassination. Or zoom in on Schumi’s Formula 1 Ferrari that won eight races out of 11, or examine absolute rarities such as the Bucciali, a front-wheel-drive, V12-engined art deco saloon of which only six were built – and only one exactly like ours.”

Off-roading used to be master Loh’s favourite pastime. In the 1980s, he competed in professional 4x4 rallying in Iceland, Russia and through the Sahara, and he still treasures his trick vintage G-Class that looks like a prop out of Jurassic (Car) Park. The man also has a soft spot for convertibles, which he claims to be more ‘emotional’ and better investments than their metal-top siblings.

If he was to start all over again in 2025 as a young car collector, what would his relatively affordable first cornerstone purchases be? He says: “I would probably invest in limitededition high-performance Porsches, in low-volume two-door AMG models and in Italian classics built when brands such as Alfa Romeo, Lancia and Maserati were at the height of their game. There are countless cool cars out there, but when a marque ceases to exist, its products tend to eventually become less collectable.

“At the end of the day, it’s all in the mix, so we need to make sure our programme is strong enough to bring people back for an even better, bigger and bolder encore.”

Vanwall driver’s valiant 1958 German GP win is all too often overshadowed by tragic circumstances

THE 1958 GERMAN GRAND PRIX at the Nürburgring was something of an all-British affair at the head of the pack. After qualifying, the front row of the grid was locked out by Brits, with Mike Hawthorn’s Ferrari 246 on pole closely followed by Tony Brooks’ Vanwall VW5.

Their team-mates Stirling Moss and Peter Collins lined up alongside them on the 4-3-4-format grid. Indeed, all four drivers had a turn leading the GP the following day, with Moss taking an early advantage prior to a broken magneto ruining any chance of victory.

Hawthorn moved to the front, before Collins passed and set off to build a lead – and to try to clinch his second victory in as many races, having won the British GP two weeks before. Soon, however, the remaining green Vanwall was in the Ferrari driver’s mirrors, with Brooks having made up an incredible 30-second deficit due to an improvement in his car’s handling as the fuel load lightened.

He got past both rivals, but shortly afterwards Collins tragically crashed at Pflanzgarten while trying to keep up with the new leader. Hawthorn retired with a clutch failure a lap later, and Brooks went on to win by over three and a half minutes. His heroic drive is often overlooked, overshadowed by the day’s calamitous events.

This is Brooks’ winner’s wreath; it was put on display in the Vanwall workshops, and many years later it was rescued by restorer Tony Merrick when demolition loomed. Each time it is moved it risks deterioration, so here it sits, preserved in these pages in still-life photographic form, as a lasting memory from this triumphant and tragic day in Germany.

We find out what Luigi Orlandini has planned for Canossa and Cavallino in the coming year – and beyond

FOR A MAN WHO HAS JUST completed the 25th Modena Cento Ore and is now in the final stages of organising a Ferrari tour of Patagonia, with Villa La Massa Excellence taking place in between, Luigi Orlandini appears remarkably relaxed.

After all, his company, Canossa, takes its name from an Italian queen who mediated between the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy more than 900 years ago. Getting guests from Argentina to Chile is probably only a little simpler. “We are crossing two countries, and then the Strait of Magellan by ferry. It is a major logistical challenge,” he says.

It has been yet another year of growth for Canossa, with an expanded Modena Cento Ore testing Orlandini’s 60-strong team. Next year promises

even more activity, with the 35th staging of the Cavallino Classic Palm Beach presenting new challenges, largely due to a change of venue.

“The Breakers is undergoing major renovation works that will last at least two to three years,” Luigi explains. Instead, the event will move to the 18th fairway at The Boca Raton: “It has never been used in that way before, and it will have a more Pebble Beach-style atmosphere.”

There will also be new classes for 2026. “We are introducing a class for the Daytona SP3, which is unusual for Cavallino,” he says. “You cannot award a Platinum prize to a car that is already essentially perfect, so we’ll be adopting a different judging method.”

Since acquiring Cavallino in 2020, Luigi acknowledges that some of the changes introduced by Canossa have upset traditionalists within the Ferrari community. “We sometimes receive complaints from long-time followers of Cavallino who say it was once reserved for Ferraris from the Enzo era and earlier,” he admits. “That’s true, but the world is changing, and I believe it is our responsibility to attract younger enthusiasts and help educate them. This benefits everyone,

including collectors of the older cars, because without new buyers the market cannot continue to thrive.”

He acknowledges that newer models tend to attract younger enthusiasts, but once inside, he has seen their fascination for older cars grow. To encourage this, Canossa offers free entry to those under 12, and a 50 percent discount for visitors under 25.

However, he is aware of the broader shift in interest towards post-Enzoera Ferraris. “People in their 40s and 50s, my generation included, did not grow up dreaming of a 275 or a 250, because we were not even born when those cars were built,” he says. “For us, the icons were the Testarossa, the F40 and the F50, which is why values for those models are rising. I am not sure what will happen to the older cars, but those of us in this community should strive to educate younger enthusiasts and help them appreciate the significance of these models.”

A key part of that mission is bringing the cars to the people, allowing them to see and hear the machines in motion. Luigi points to the recent Modena Cento Ore as an example: “We had an impressive line-up of five Alfa Romeo 8C 2300s from the 1930s, alongside newer entries such as a BMW M1 from the 1980s. We held a one-and-a-half-hour parade past some of Rome’s most famous landmarks before continuing to Assisi, Florence, Modena, San

THIS PAGE He’s busy with events such as Modena Cento Ore, but Orlandini has further big event plans.

Marino, Rimini and Forlì. Sharing these cars with the wider public is, I believe, equally important. Seeing them pass by attracted great interest, even from the general public.”

However, appealing to enthusiasts still lies at Canossa’s core, and facilitating what must be a dream for most Tifosi is the big development for 2026. The Cavallino Classic Monaco in April will see Ferrari Formula 1 cars not only displayed at the principality’s yacht club but also taking to the streets during the Monaco Historique. “It is a unique opportunity, and we have had an excellent response from collectors,” Luigi confirms.

Looking further afield, he sees growing interest in Asia, particularly in Japan. “I have visited many times – it is such a beautiful country with warm, welcoming people who also have great affection for Italy,” he says.

In the meantime, Canossa continues to run smaller events and bespoke tours for select groups of travellers through its Atelier programme. But does Luigi have a favourite event? “They are like children: you cannot have a favourite,” he laughs. Find out more at www.canossa.com.

Scaglione-designed 3500GT one-off –the 1959 Turin Auto Show car – earns special Magneto award at The Quail

DURING EVERY MONTEREY CAR

Week, we award our Magneto Art of Bespoke trophy at The Quail, A Motorsports Gathering, to the car we judge to be the best one-off or lowvolume example at the event.

At the 2025 running of The Quail, Magneto’s editorial director David Lillywhite presented the trophy on stage to Jim Utaski for his stunning one-off 1959 Maserati 3500GT – the 1959 Turin Auto Show car, and the last model to be designed by Franco Scaglione during his time at Bertone.

THIS PAGE The Maserati 3500GT was recognised with a special trophy at The Quail 2025.

period photos as well as Bertone and Maserati company archives.

Bertone had exhibited the 3500GT at the 1959 Turin Auto Show, with four pieces of matching custom luggage in the rear instead of seats. Swiss Maserati dealer Martinelli & Sonvico bought the car direct from the show stand for one of its best customers, Josef Willi, requesting a number of modifications including wire wheels fitted with three-eared spinners, Fiamm horns and Koni rear dampers. The luggage was also replaced by traditional rear seats, and the front chairs were substituted, too.

Later in its life, from around 1969, the car was left in an open shed and allowed to deteriorate. It was rescued in 1978 by Francis G Mandarano, the founder of the Maserati Club International, missing its engine and in need of full restoration. However, it

seems that Mandarano hadn’t realised that it was the Turin show car, and his subsequent work on it paid little attention to historical accuracy.

Years later, the Maserati was bought by current owner Utaski, who made the decision to have it restored back to its original Turin show specification, complete with custom set of luggage. Incredibly, Jim managed to find an engine that was the next off the production line after the car’s missing original; after a 5000-hour restoration with Epifani Restorations of Berkeley, California, the 3500GT was shown at Pebble Beach in 2023 – and, of course, it caught our eye again at The Quail, A Motorsports Gathering.

It was there that we met with Jim Utaski to give him the Magneto Art of Bespoke trophy, designed and created by UK artist Jonny Ambrose. See www.jonnyambrose.com for details.

Tamiya, Inc chairman

Shunsaku Tamiya and his brother Masao both passed away in 2025. We celebrate their legacy

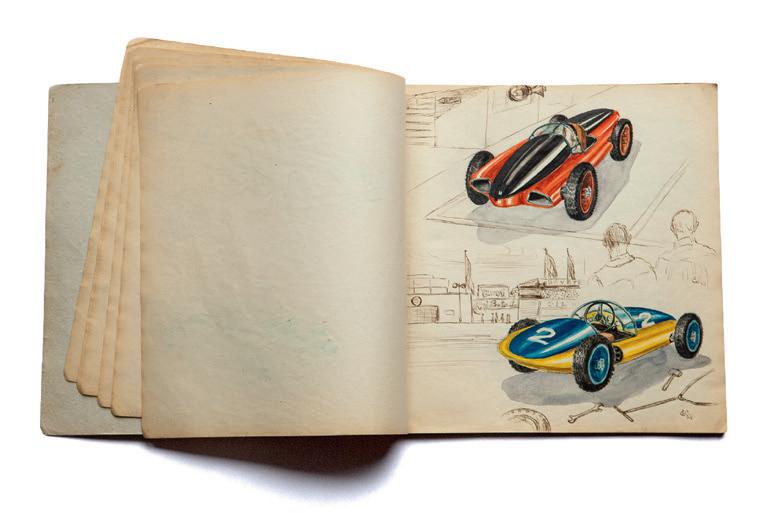

AS WITH SO MANY OF MY generation, my first car wasn’t one I could sit in. It was a radio-controlled Tamiya – a hand-me-down Martini Renault Formula 2 car from a cousin. It didn’t work. I didn’t have, and couldn’t afford, the controller, the servos or the receiver. But none of that mattered. I was still mesmerised by this joyous thing. I can still feel the edges of the bodywork beneath my fingertips, and conjure the bitter smell of its slick rubber tyres. As with so many, I would wager, I’d place it on my bedroom floor and, with my head flat beside it, gaze at it from eye level to amplify the realism.

In the embers of post-war Shizuoka, Yoshio Tamiya eked out a living with a modest sawmill, Tamiya Shoji & Co, founded in 1946 to help rebuild a nation. That all changed in 1951, when a devastating fire wiped out the lumber stock. It might have been

the end, but instead it became a beginning: Yoshio pivoted into crafting wooden model kits.

Yoshio’s son, Shunsaku, was born in 1934 and, after finishing school in the prefecture, went on to study at Waseda University. When he returned home, in 1958, it wasn’t just to help his father, it was to begin writing the next chapter. With Waseda behind him, Shunsaku joined Tamiya Shoji & Co, bringing academic discipline to a workshop already rich with craftsmanship and passion. He would soon steer it from wood to plastic, from local kits to global dreams.

I had interviewed Formula 1 world champions, motor-racing legends, the greatest of the great – but when I finally sat opposite Shunsaku Tamiya at the Nuremberg International Toy Fair in 2009, I realised I had never been more nervous, nor more excited. Here was a man who, perhaps

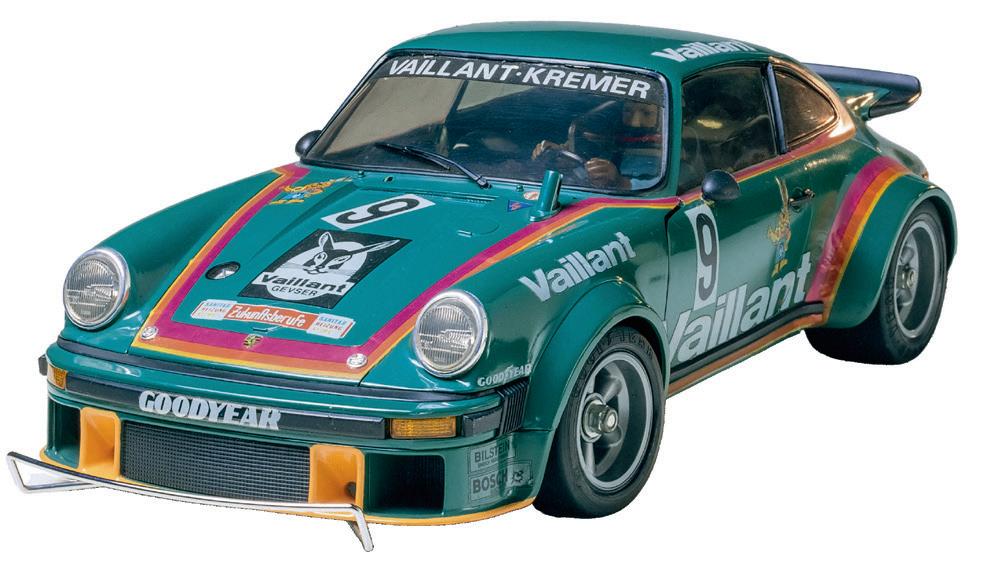

OPPOSITE The 934 was Tamiya’s first RC car. With superb engineering, and presented in beautiful packaging, it was a phenomenon.

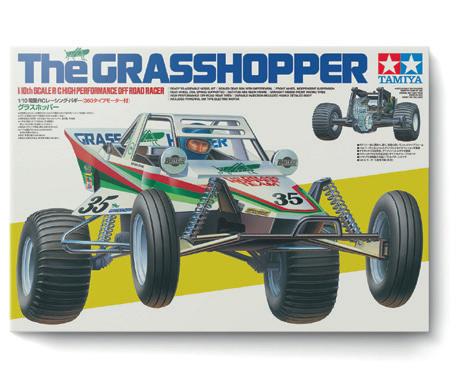

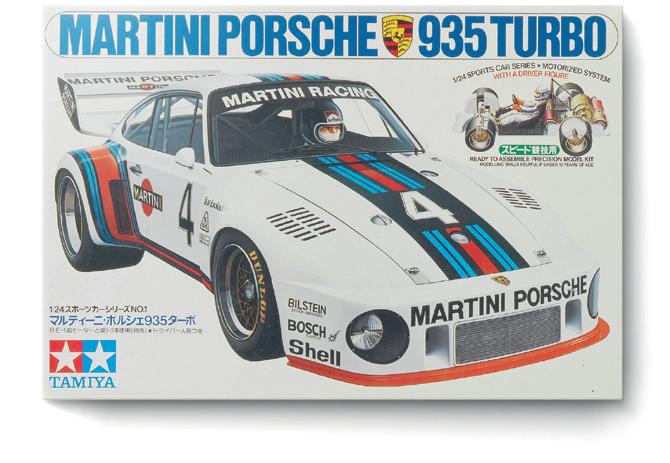

Grasshopper and Porsche 935 have been among Tamiya’s most popular models.

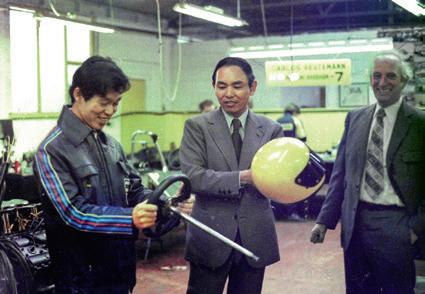

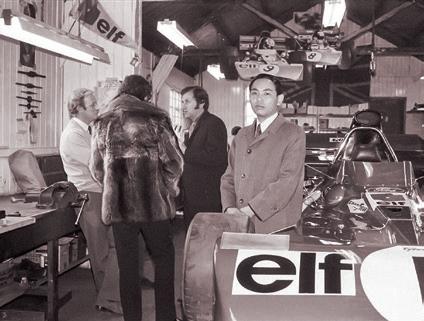

Boss Shunsaku’s research stretched to visiting Brabham in the UK with top model designer Honma-san (left), to see the Martini Racing BT44.

more than anyone else, had been responsible for sparking my deep fascination with the motor car. “I wanted people to build, to drive, to understand,” he told me.

The leap into radio control came thanks to Fumito Taki, a young engineer whom Shunsaku had spotted playing with radio-controlled models in the company’s car park (and legend has it, flying RC planes, too). Until then, most RC cars were petrol powered, with poor likeness to the real thing. Shunsaku had a brainwave – make them electric, and align the scale fidelity with the company’s (now famous) plastic model kits.

There was another imperative, too. The company had purchased and deconstructed a Porsche 934 at great cost in order to produce a 1:12th scale model, but it was not a commercial success. Shunsaku briefed ‘Dr Taki’ to reuse and recoup the mould cost and

transform the static Porsche into an electric-powered radio-controlled car.

Taki’s RC 934 was a phenomenon. It looked like a real Porsche, it had durable, accessible engineering, it combined a kit-building experience with beautiful packaging, and it was distributed globally.

The Tamiya XR311 Combat Support Vehicle and Lamborghini Cheetah followed, as off-road vehicles with detailed bodies, but they were fragile. So after witnessing the Baja Buggy races in California, Shunsaku returned to Shizuoka determined to capture that wild energy and toughness in miniature. Between Shunsaku and Taki, they delivered. Their genius lay in fusing mechanical realism with accessibility: cars that looked like the real thing, taught you how they worked, and survived the rough-and-tumble of childhood play.

That ethos – learn by doing –became the defining trait for Tamiya. Whether you were building a static kit of a Tiger tank or assembling the fragile rose joints of an Avante RC buggy, the process taught you something. You didn’t just own a Tamiya; you experienced it.

And that experience, I came to realise, is universal. I have seen it everywhere: a Le Mans engineer confessing that his fascination with aerodynamics started with a Tamiya Porsche 956; a designer at a major EV manufacturer explaining that her first lesson in packaging came from cramming a 7.2V NiCad into the tub chassis of a Grasshopper. Even Adrian Newey, the greatest race-car designer of his era, has spoken of how building Tamiya kits honed his instincts. In

THIS PAGE A visit to Tyrrell resulted in a model of the still-popular P34, designed by Honma-san. The Lotus 49B was among the kits that inspired a young Adrian Newey to Formula 1 greatness.

the distributor still serving the UK and Ireland with what Shunsaku once called “courage and insight”. Those early kits – particularly the Lotus 72 –became runaway hits, putting Tamiya firmly on the map for a new generation of model-makers and race fans.

In an era awash with AI, simulations and hyper-realistic gaming, you might expect physical model-making to have edged into obscurity. Yet Tamiya has quietly defied that trajectory. Its kits offer tactile joy – a slow, deliberate counterpoint to instant digital gratification. Forums brim with hobbyists sharing build logs and weathering techniques – sometimes using AI to refine colour palettes or test liveries, but always grounded in handson craftsmanship. Even in the digital realm, modellers reference Tamiya as the standard: clean engineering, intuitive fit, instructions that welcome newcomers yet reward purists...

define the brand’s visual soul. Masao, who passed away in August 2025, was responsible for the striking look and feel of the packaging and promotional material, as well as for media and event strategy. He was also the creator of the iconic twin-star logo.

To open a Tamiya kit was to enter another world: the sprues perfectly laid, the instructions folded with care, the lid art so vivid you could almost hear the whine of tyres or the roar of the tank. Long before Apple perfected the theatre of packaging, Tamiya had already nailed the ritual of ‘unboxing’.

The UK was one of the first places to embrace Tamiya. In 1966, a chance pairing between a discerning British toy wholesaler and Tamiya’s plasticmodel innovations sparked something remarkable. David Binger of Richard Kohnstamm Ltd (RIKO) chased down a handful of grey-imported Tamiya kits on a US buying trip – and within the year, he’d travelled to Shizuoka to meet Shunsaku and his father. This planted the seed for Tamiya’s emergence in the UK and Europe. David’s faith in the brand did more than launch sales; it helped establish Tamiya as a household name among hobbyists. His son Pete now leads The Hobby Company in Milton Keynes,

And the business behind all of this remains quietly healthy. Tamiya is private, but its global footprint speaks to sustained demand. When Shunsaku eventually stepped back from leadership in 2024, it was not under pressure but as part of a careful succession plan. Today, under the stewardship of his grandson-in-law Nobuhiro Tamiya, the company has expanded its reach while holding fast to its core promise: kits that delight, educate and endure. When news of Shunsaku’s passing broke in summer 2025, what followed was not concern for the company’s future but a global chorus of gratitude.

I last spoke to Shunsaku a decade after we first met. He reflected on the global community his firm had created.

“It is business,” he said, “but also my personal passion. The enjoyment of assembling something by hand is different. It teaches you how things are made, and patience. It gives history.”

It is difficult to think of another brand, in any field, which has inspired such enduring affection. The reason is simple: Tamiya never talked down to its audience. Whether you were an engineer in Stuttgart or a 12-year-old in Gravesend, the kit in front of you carried the same promise of possibility.

Shunsaku Tamiya didn’t just build models. He built bridges – between generations, between cultures, between the simple joy of creation and the boundless possibilities of curiosity.

Martyn Goddard

THIS PAGE From the Ital Aztec to the Lamborghini Calà and the Touareg, and plenty more besides, the 2003 Italdesign road trip was epic.

March 2003 memories of a 200-mile drive in Italdesign prototypes to mark 35 years of the iconic Italian design house

I ARRIVED FROM LONDON AND met up with Jean Jennings, legendary editor of Automobile magazine, and her husband Tim for one of the strangest road trips of my 50-year career.

“Hey Marty, we are going to have a ball: a 200-mile road trip in a bunch of Giugiaro’s prototypes to celebrate 35 years of Italdesign.” That was the good news. The bad news was that our fellow trippers were the great and the good of the world’s motoring press.

At Italdesign’s HQ there followed a short briefing by Fabrizio Giugiaro on the firm’s design ethos, and a drivers’ meeting given by Franco Bay describing our route to Lake Como via the wine capital Barolo. He supplied no maps but did give us a sheet of directions with kilometre markers. However, since none of the 21 show cars had odometers, the drive was... interesting Once the motoring scribes had

chosen their individual rides – Ms Jennings selected the 2000 ‘Mad Max’ Touareg concept – the leading Lancia minivan swept out of the gates towards the autostrada with the wacky racers trailing in its slipstream. The photographers hitched a ride in either the show cars or the caravan of support vehicles.

The locals must have thought they were seeing things as strange-looking prototype cars passed at speed with a bunch of snappers hanging out of every window of the chasing vehicles taking tracking shots. Things settled down as we approached the first stop at Cherasco, which gave us a chance to photograph the locals eye-balling the cars and shoot atmospheric images of the concepts in a classical Italian location. Suitably refreshed, the writers swapped steeds and departed, leaving the photographers

with no time for coffee and scrambling for transport to the lunch stop.

The trip continued apace, with photo cars blasting ahead of the pack to shoot the all-important images of the convoy driving through the Italian countryside and villages. By the time we arrived at the Castillo Marchesi di Barolo, Jean had switched to a Maserati Buran and I, as with my photographer colleagues, was exhausted. The fun continued with a fine dinner in the castle and a conjuror vanishing one of the show cars in the courtyard.

On day two, the cars headed north towards Lake Como. All was going well until disaster stuck; a flat battery caused my new digital Canon 1DS to stop working. I’d only recently made the move to digital, and I couldn’t understand why. A fellow snapper asked: “Did you leave your hotel room and remove the key? That is the

problem; the power to your charger turned off when you left the room.”

I had a spare film camera in my bag but was short of 35mm, so at the first autostrada fuel stop I raided the shop for every roll of film it had. I was then ready for the lunch stop at Arona. The restaurant’s courtyard was packed with Italy’s finest. The local police officer spent his time examining the strange cars and keeping admiring local kids off them. When it was time to depart, we had a police motorcycle escort for the lakeside drive.

Arriving at Cernobbio on Lake Como’s west shore, we parked the cars up at the hotel. To my knowledge none had failed to complete the run, and all were ready for detailing for the Villa Erba show to celebrate Italdesign at 35. Assignment completed, I returned to London with fond memories of a wonderful, if unusual, Italian road trip.

Frohe Weihnachten und ein glückliches neues Jahr

I migliori auguri per un buon Natale e un felice Anno Nuovo

Joyeux Noel ainsi qu‘une bonne et heureuse nouvelle année

Zalig Kerstfeest en een Gelukkig Nieuwjaar

Feliz Navidad y un próspero Año Nuevo

AND

The Ferrari F80 has once again seen the Prancing Horse gallop to the top of the hypercar class – but how does the new charger measure up against Maranello’s stable of ultimate machines?

Contrary to popular belief, the 288 GTO was not originally conceived to be Ferrari’s Group B competition weapon. Instead, the germ of the project originated from Enzo’s belief that the Ferrari range didn’t have a halo model – in his words, it was too “gentrified”. However, with a chief engineer of Nicola Materazzi’s calibre (he played a key role in the Lancia 037, among many other things), the possibilities of Group B use became apparent. Just 272 road cars were built, powered by a 395bhp twinturbo V8 that made the 288 GTO good for a 5.0-second 0-60mph dash and a top speed of 189mph.

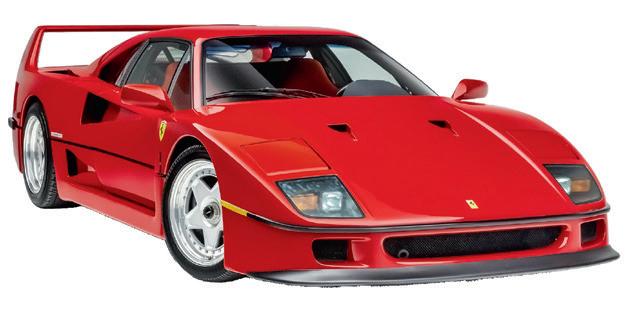

The 288 GTO Evoluzione intended for Group B suddenly found itself without an arena to race in, so Materazzi convinced Enzo that the essential idea would make for a great road model. Il Commendatore agreed, and the F40 was born. Ferrari claimed it was the first road car to breach 200mph – something independent tests failed to prove, but no matter. This bare-bones car was blisteringly quick, with 471477bhp from its 2.9-litre twin-turbo V8, wrapped up in a 1254kg body; it could hit 60mph in 4.7 seconds.

Unlike the 288 GTO the F40 did compete in global endurance racing, with the Michelotto-built F40 LM. A further development for privateer drivers, the F40 Competizione, appeared with 691bhp and 228mph. There were 1311 F40s in total.

ABOVE Ferrari’s first 200mph-plus car? Debatable – but the F40 was blisteringly quick.

To celebrate its 50th birthday Ferrari decided to put that age-old trope – a racing car for the road – to the test with the F50. At the model’s heart was the Tipo F130 V12, which could trace its roots back to the 1990 641 Formula 1 car and, in evolution form, the 333 SP racer. It was teamed with a six-speed manual ’box and clothed in a love-it-or-hate-it carbonfibre body from Pininfarina’s Lorenzo Ramaciotti and Pietro Camardella. Its 4.9-litre naturally aspirated V12 made it good for a 198mph top end and 3.8-second 0-60mph dash. Looked upon dismally for many years – Ferrari not allowing auto journalists to drive it didn’t help – the F50 has since gone on to be one of the auction world’s hottest properties. It is the most expensive car here, and just 349 were built.

Ferrari sought F1 inspiration for its millennial monster, which boasted a carbonfibre body and a six-speed Graziano automated manual. It even had active aero, which the Scuderia wasn’t allowed to use in competition. The Ken Okuyama styling was, if anything, more polarising than the F50’s – although there was no denying the Enzo’s potency. Its 6.0-litre naturally aspirated V12 developed 651bhp, propelling the Enzo to 60mph in 3.1 seconds and onto a 218mph top speed. Four hundred examples were built, and F40 aside it’s the least expensive way to get into a Ferrari hypercar – you’ll need an average of £2.9m. Interestingly, the most expensive

The FXX Corse Clienti track-day model formed the basis of Ferrari’s next flagship – which had one of the most awkward car names ever. The first non-Pininfarina-styled Ferrari in more than five decades, it was also the marque’s first full hybrid, delivering 950bhp via a 789bhp naturally aspirated V12 and a 161bhp HY-KERS unit. It could do 0-62mph in 2.6 seconds, double that in barely twice the time and hit 220mph. The topless Aperta of 2016 formed the basis of the FXX-K and FXX-K Evo track-day cars; 499 LaFerraris

To celebrate its 80th birthday Ferrari has unleashed the F80. Under the car’s carbonfibre skin it has the twin-turbo V6 derived from the Le Mans-winning 499P, with three electric motors. The 3.0-litre ICE powerplant produces 888bhp; that’s 296bhp per litre with 55psi of turbo boost – the highest figures of any production car ever. That’s augmented with 296bhp

LEFT Arguably unloved at first, the F50 has since gone on to become one of the auction world’s hottest properties.

ABOVE The 950bhp LaFerrari was the marque’s first full hybrid, marking the dawn of a new era.

New Generations Trophy is the ultimate activity for Historic motor sport-loving families

HOW DO WE GET THE YOUNGER generations into Historic motor sport?

By encouraging them, of course – but that’s easier said than done. Several organisations are already doing this, including HERO-ERA with Rally For The Ages, Rally The Globe with its Generations Rally and Happy Few Racing with variants of its father-andson and father-and-daughter event. Now Motor Racing Legends (MRL) has introduced its own version.

MRL’s all-new Generations Trophy had its first outing at Silverstone in late October 2025, bringing together 20 teams. Several of the drivers were new to competitive motor sport. The concept is simple: each car is identical, and each driving team is made up of two generations of the same family. All compete in a 60minute race at the wheel of a pre-1966 FIA-specification MGB – chosen for

its accessibility, mechanical simplicity and relatively low cost – and to ensure a level playing field, each car’s power is measured on a dyno before the race.

The 20-car field included many rookie drivers, from 18-year-old Evie Russell to John Kent, who was making his racing debut at the age of 73. Richard Hammond of Top Gear and The Grand Tour fame teamed up with his daughter Izzy for their first-ever shared race, in MGB number 351.

“Izzy and I both came here to learn,” said Richard. “We just wanted to finish the race in one piece, and we did. We’re not yet ready for a ‘real’ Historic race, and the Generations Trophy seems like a great entry point for people like us. We will do more.”

Shaun Lynn, the owner of Motor Racing Legends, shared MGB number 13 with his daughter Jemima: “As a motor-racing enthusiast, I have been

indoctrinating my children for a very long time,” he said. “The many races I have done alongside my sons, Alex and Maxwell, have helped to bring us closer together. These are very special moments.

“Jemima often followed us to the circuits, but she never dared to put on a helmet. It’s actually thanks to her that I came up with the idea for a series dedicated to those who need a welcoming and safe environment to

‘The many races I’ve done alongside my sons have helped to bring us closer together’

THIS PAGE Each team is made up of two generations of the same family. Even Richard Hammond is giving it a go...

take that first step into racing.”

Evie Russell shared MGB number 67 with her grandfather, Gordon: “My granddad has been racing for 57 years. I’m used to following him as a spectator at Goodwood and elsewhere, so when MRL announced the Generations Trophy, we jumped at the chance to compete together. I was a bit nervous, but everything went really well. I had some great battles on track, and I was genuinely emotional when I handed over the wheel to my grandfather. I can’t wait to do it again next year.”

The race was won by Rick and Joseph Willmott, who beat Patrick and Aimee Watts into second place. The Generations Trophy will return at the Donington Historic Festival on the Early May Bank Holiday weekend, May 1-3, with around 30 cars expected. You can find out more information at www.motorracinglegends.com.

These are the entries that made it through to final voting for the International Historic Motoring Awards

THE SHORTLIST FOR THE 2025 International Historic Motoring Awards (IHMA) presented by Lockton is a roll call of the very best events, cars and achievements of the past year.

There were a record number of entries for this year’s Awards, taking place on November 14 at The Peninsula London. After this, results will be on www.historicmotoringawards.co.uk.

Those who made it onto the shortlist advanced to the final stage of judging, from which a distinguished panel of experts and prominent figures from the motoring world determined the winners. The judges included TV stars Wayne Carini and Donald Osborne, Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance chairman Sandra Button and Octane Japan editor Shiro Horie.

The 2025 IHMA is supported by Castrol Classic Oils, Classic Car Register, Revs Institute, the Petersen Automotive Museum and Nyetimber, and Octane and Magneto magazines.

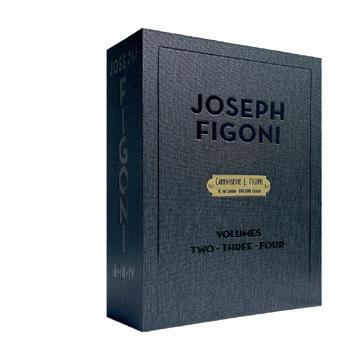

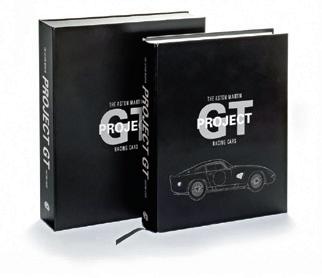

BOOK OF THE YEAR

Spy Octane: The Vehicles of James Bond, by Matthew Field and Ajay Chowdhury (Porter Press International)

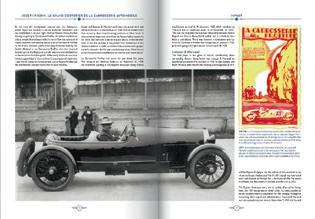

Joseph Figoni: Le Grand Couturier de la Carrosserie Automobile Vol. II-IV: Bugatti, by Peter M Larsen and Ben Erickson (Moteurs!)

Power Unleashed: Trailblazers Who Energised Engines With Supercharging and Turbocharging, by Karl Ludvigsen (Evro)

Twice Around the Clock – The Yanks at Le Mans Vol IV-V, by Tim Considine (David Bull)

The Aston Martin ‘Project’ GT Racing Cars, by Stephen Archer and David Tremayne (Palawan Press)

BREAKTHROUGH EVENT OF THE YEAR

The Royal Automobile Club Concours

Concours of Slovakia

Pearl of India Rally

CAR OF THE YEAR

Sunbeam 350hp ‘Blue Bird’

Alfa Corse Alfa Romeo 158

Hispano-Suiza H6C Nieuport-Astra Torpedo

Mercedes-Benz W196R Stromlinienwagen

Ford Escort Alan Mann 68 Edition

Alfa Romeo Tipo B (P3)

BRM P5781 ‘Old Faithful’

RESTORATION OF THE YEAR

Sponsored by Classic Car Register

Jaguar C-type by Tony Purnell / Pendine / CKL Developments

Aston Martin Two Litre Sports by RS Williams

Hispano-Suiza H6C Type Sport Torpedo by RM Auto Restoration

Ferrari 410 Superamerica by Paul Russell & Company

Hispano-Suiza H6C ‘Boulogne’ by Jonathan Wood

Ferrari 275 GTB/4 Alloy by Tom Hartley Jnr

Siata 208 CS Balbo by RX Autoworks

BESPOKE CAR OF THE YEAR

Sponsored by Octane

R33 Stradale by Automotive Artisans

Rolls-Royce Corniche ‘Henry II’ by Niels van Roij Design

Wood & Pickett Mini by CALLUM

Lightweight GTR by Eagle

Veloce12 Barchetta by Touring Superleggera

Battista Novantacinque by Pininfarina

Ford Escort Alan Mann 68 Edition

Batur Convertible ‘One-Plus-One’ by Bentley Mulliner

The Ayrburn Classic

Icons Mallorca

CLUB OF THE YEAR

Sponsored by Lockton

Aston Martin Owners Club

Vintage Sports-Car Club

MG Car Club

Porsche Club GB

INDUSTRY SUPPORTER OF THE YEAR

BMW Group Classic

Heritage Skills Academy

Historic & Classic Vehicles Alliance

Association of Heritage Engineers

Motul

Piston Foundation

Mercedes-Benz Heritage

MOTORSPORT EVENT OF THE YEAR

Sponsored by Revs Institute

Rolex Monterey Motorsports Reunion

Pittsburgh Vintage Grand Prix

Le Mans Classic

Silverstone Festival (including the World Champions Collection)

MOTORING EVENT OF THE YEAR

Sponsored by Nyetimber

The Quail, A Motorsports Gathering

The Amelia Concours

The Bridge

Salon Privé

ModaMiami

The Aurora

Audrain Newport Concours & Motor Week

Concorso d’Eleganza Villa d’Este

PERSONAL ACHIEVEMENT OF THE YEAR

Sponsored by the Petersen Automotive Museum

Guy Moerenhout

Luigi Orlandini

Tomas de Vargas Machuca

Fritz Burkard

SPECIALIST OF THE YEAR

Sponsored by Castrol Classic Oils

Tom Hartley Jnr

HK-Engineering

RM Sotheby’s

Rally Preparation Services

Aston Martin Works

Lamborghini Polo Storico

RALLY OR TOUR OF THE YEAR

Tour de Corse Historique (Modus Vivendi)

Terre di Canossa Rally (Canossa Events)

Flying Scotsman (HERO-ERA)

Rallye des Princesses (Peter Auto)

Oman Classics 2025 (HK-Engineering)

RISING STAR OF THE YEAR

Ethan Blake-Jones (Paddock Speedshop)

William Garrett (Hilton & Moss)

Alex Hearnden (96 Engineering)

Will Marsh (VSCC)

RACE SERIES OF THE YEAR

Super Sprint (Equipe Classic Racing)

Alfa Revival Cup (Canossa Events)

Endurance Racing Legends (Peter Auto)

GT & Sports Car Cup (Automobiles Historique)

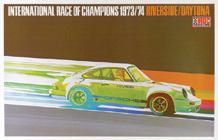

IROC (IROC Holdings)

Silverline (Formula Junior Historic Racing Asso)

MUSEUM / COLLECTION OF THE YEAR

Sponsored by Magneto

Silverstone Museum

Petersen Automotive Museum

National Motor Museum (Beaulieu)

Autoworld Museum (Brussels)

Museo Alfa Romeo

Nationales Automuseum The Loh Collection

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum

DIGITAL MEDIA OF THE YEAR

The Late Brake Show

Richard Hammond’s Workshop

Harry’s Garage

Jay Leno’s Garage

Petersen Automotive Museum

Vintage Velocity podcast

Hagerty Media

Boxengasse

IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE PHIL AND MARTHA BACHMAN FOUNDATION & CHRISTOPHER MIELE OF PRANCING HORSE OF NASHVILLE 48 AUTOMOBILES TO BE OFFERED AT KISSIMMEE • JANUARY 6-18, 2026

ONE HUNDRED YEARS SINCE WORK BEGAN ON THE NÜRBURGRING, WE SPOOL THROUGH HISTORY FROM THE GLORY DAYS OF THE SILVER ARROWS TO THE LARGER-THAN-LIFE ANNUAL 24-HOUR RACE, WRAPPING UP OUR ODE TO THE NORDSCHLEIFE WITH A HOT-LAP SLIDESHOW OF THE WORLD’S LONGEST AND TOUGHEST CIRCUIT.

SO PUT ON YOUR HELMET, BUCKLE UP AND SET YOUR MIND TO AWE-AND-RESPECT MODE

WORDS

GEORG KACHER

PHOTOGRAPHY

FRANK BERBEN-GROESFJELD

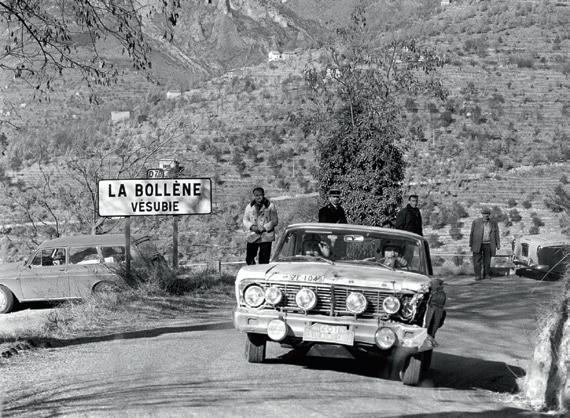

FOR YOU, WHAT DOES THE CATCHWORD ‘Nürburgring’ trigger? My initial flashback is in grainy black and white. Caracciola, Nuvolari, von Brauchitsch and Rosemeyer in bright, flabby overalls, their tanned faces badger pale where the goggles have left their marks, leading the 1935 drivers’ parade. Cut. Revolve to the next image, now in full colour; the blazing fire that engulfs Niki Lauda’s Ferrari, with the fearless Arturo Merzario diving into a slo-mo rescue. Cut. Wind forward to early 2025, as an extensively YouTubed Xiaomi SU7 Ultra prototype records a 6:22.09 lap time – the third fastest ever – beating every other contender to date bar Timo Bernhard in the Porsche 919 and Romain Dumas in the almost-forgotten Volkswagen ID.R. Cut. Another handbrake turn, this time to the pre-war days when the Nürburgring still features a short, 7.74km appendix aptly named Südschleife, which will stage its final competition in 1973 prior to being part-overbuilt by the new Grand Prix circuit inaugurated in 1984. Cut. The Nordschleife

ABOVE With work starting in 1925 and the first race taking place in 1927, the challenging Nürburgring was the pride of Germany’s inter-war car industry.

loses its Formula 1 ticket in 1977 due to persistent safety issues, but even so its popularity will rise to new heights thanks to the annual 24-hour race that keeps attracting huge crowds. Cut. Enough food for thought? Now let the mind freewheel from one flashback to the next, conjuring more Nürburgring myths and memories.

The origin of the Ring, as we know it today, dates back to 1907, when Emperor Wilhelm II pondered setting up an extensive proving ground for the nascent German car industry. After World War One the idea resurfaced, and an early version of the Ring was compiled from several sections of public roads, which added up to a 33km-long street circuit. On July 15, 1922, the ADAC Rhineland conducted the first Eifelrennen, which attracted 134 competitors and more than 40,000 spectators.

Two years later, an encore was staged – and promptly deemed too dangerous for drivers and spectators alike. As a result, three senior county officials in charge of the Nürburg, Adenau and Mayen districts founded a special division of the ADAC that had only one mission: to build Germany’s ultimate permanent racetrack. The mastermind of the project was Otto Creutz, who

named Gustav Eichler as chief architect.

On May 18, 1925 the Adenau county council signed off “the construction of a groundbreaking permanent racetrack”. ‘Track’ was perhaps a bit of an overstatement; partially sealed one-way scenic drive without crossroads or turn-offs would have been a more accurate description. On September 27, 1925, 100 years ago this year, the foundation stone of the circuit was laid in the presence of the first president of the Rhine province, the former imperial minister Dr Fuchs. With the help of up to 2500 workers, the track was completed in only 23 months – no mean feat in view of the unsophisticated construction equipment and barren budget. The Eifel region’s volcanic nature, with its rich basalt deposits, allowed for the entire track to be built on rock. Initially, the surface construction consisted of a 20cm layer of very hard basalt covered with a sufficiently thick blanket of hand-crushed basalt, which was then flattened using huge steamrollers. Although the German Government spent close to RM15,000,000 on this prestige project, there were no guard rails whatsoever, no fences, no kerbs and most certainly no run-off areas. “The only changes here are the trees – they just get thicker every year,” quipped Jackie Stewart many years later – and he never experienced the original layout, which included a unique feature known as Steilstrecke (steep climb). This special section forked off

100 YEARS OF

LENGTH

20.832KM (12.94 MILES)

FASTEST LAP TIME 5:19.55 – PORSCHE 919

HYBRID EVO (JUNE 2018)

WIPPERMANN

BRÜNNCHEN

PFLANZGARTEN I

Initially just a flat 180º slow-speed corner, the Karussell’s sloped inside drainage area is first used by MercedesBenz driver Rudolf Caracciola to effectively slingshot his way to victory, finishing more than 78 seconds ahead of Louis Chiron’s Bugatti at the 1931 German GP.

6:11.13

In final practice for the 1983 1000km, Stefan Bellof’s Porsche 956 clocks the Nordschleife in just over six minutes, 11 seconds. His lap time remains the fastest ever recorded as part of a race event. Thirty years later, a section of the circuit is named the Stefan Bellof-S.

PFLANZGARTEN II

GALGENKOPF

DÖTTINGER

HÖHE

ESCHBACH EISKURVE

SPRUNGHÜGEL

KARUSSELL

HEDWIGSHÖHE

HOHE ACHT

F1’S FIERY NORDSCHLEIFE FINALE

August 1, 1976. On the second lap of the Grand Prix, Niki Lauda loses control of his Ferrari 312 in the section between Ex-Mühle and Bergwerk. He crashes heavily into a barrier and is engulfed in flames. Although suffering severe external and near-fatal internal burns, he’s back in his race car just six weeks later. Understandably, F1 turns its back on the Nordschleife for good.

KLOSTERTAL

MUTKURVE

KLEINES KARUSSELL

SCHWALBENSCHWANZ

KESSELCHEN

BERGWERK