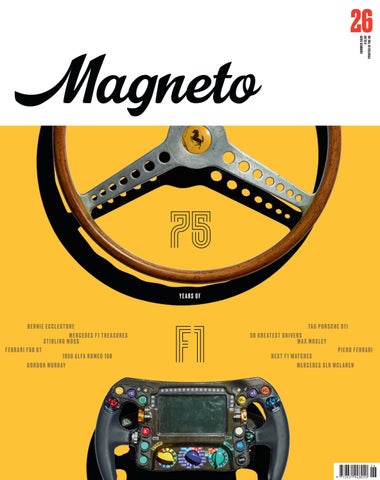

BERNIE ECCLESTONE

GREATEST DRIVERS MERCEDES F1 TREASURES

PORSCHE

MOSLEY STIRLING MOSS

F50 GT

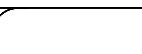

MERCEDES SLR MCLAREN

BERNIE ECCLESTONE

GREATEST DRIVERS MERCEDES F1 TREASURES

PORSCHE

MOSLEY STIRLING MOSS

F50 GT

MERCEDES SLR MCLAREN

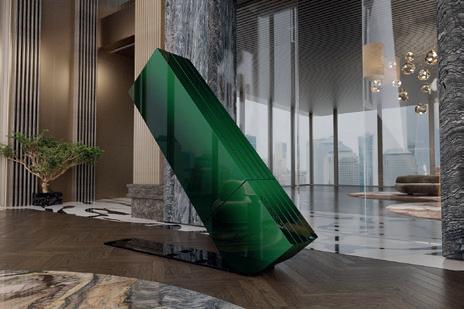

Discover the fusion of cutting-edge technology and exclusive design. Seamlessly blending into your luxury living space, the bespoke C SEED N1 TV is encased in the finest handcrafted finish, tailor-made and customizable to match any interior. When closed, it exudes the elegance of fine furniture, resembling a sleek and sophisticated sideboard.

At the touch of a button, the TV gracefully rises to a majestic height of two meters, and five 4K high-brightness MicroLED panels unfold like the petals of a blooming flower. In just 45 seconds, they form a stunning display measuring 165, 137, or 103 inches.

C SEED’s unique patented Adaptive Gap Calibration ensures that the borders between the panels vanish, giving you a perfect, uninterrupted visual experience.

The ultra-high-resolution display transforms any room into a cinematic paradise, offering breathtaking visuals in any lighting condition. The C SEED N1 redefines the synergy of technology and luxury living - it is a statement of sophisticated taste and a testament to the unforgettable moments you’ll share.

The C SEED N1 TV is available in three sizes: 165, 137, and 103 inches, as well as in various colors and bespoke finish options.

n Historic first chassis M26/1

ex-Hunt and Mass

n Six Grand Prix starts for McLaren, 4th at famous ’77 British G.P.

n 2021 Monaco Historic G.P. winner

n The only M26 eligible for Monaco Series E

n Offered from 24 years ownership and historic racing

14 Queens Gate Place Mews London SW7 5BQ

T: +44 (0)20 7584 3503

W: www.fiskens.com E: cars@fiskens.com

ABOVE 1952 JAGUAR C-TYPE, EX-FANGIO

n Famously purchased new by the great Juan Manuel Fangio

n Now offered by 2009 Formula 1 World Champion Jenson Button

n Period race history in Argentina, one of the fastest C-Types today

n Wins at Goodwood, Monaco, Silverstone Classic and more

n DBR9/5 is the only works DBR9 sold from new to North America

n Entered in the 2008 ALMS Championship achieving 4 podiums

n Driven by Dario Franchitti at the Endurance Racing Legends 2021

Le Mans 24 Hours support race –1st in Class Race 2

n 2023 Peter Auto Endurance Racing Legends GT1B winner

LEFT

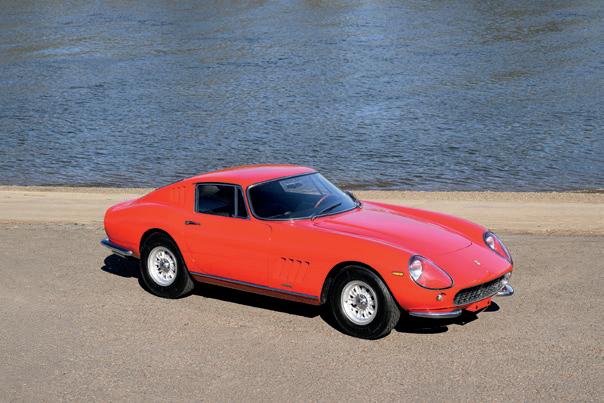

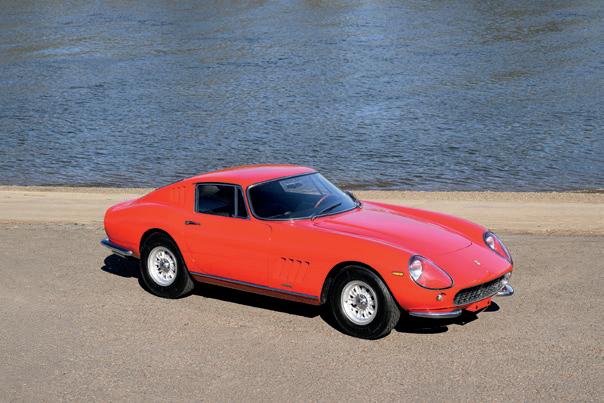

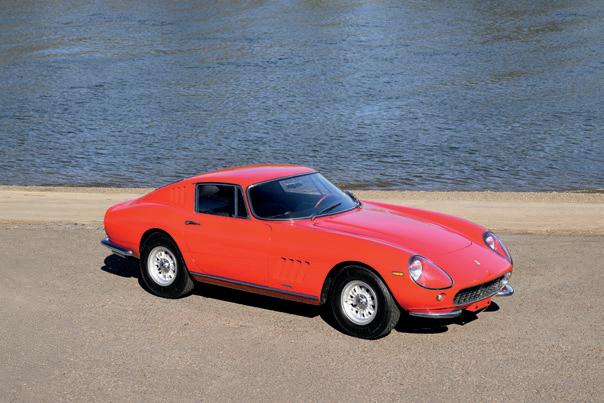

1965 FERRARI

275 GTB

n Fantastic early shortnose 275, chassis 06897, delivered in Rosso Cino over black

n Continuous ownership history, delivered new to Milan, Italy

n Fully matching numbers with Red Book Classiche Certification and Marcel Massini report

n Fresh from 3-year body off restoration completed in 2023

ABOVE

1935 DERBY BENTLEY 3½ VESTERS & NEIRINCK

n Exceptionally elegant coachwork by Vesters & Neirinck

n The first of the exclusive pair in this style

n Sister car now in the Loh Collection

n Originally delivered to Claude Lang of Brussels

n A highly significant and exquisite Derby Bentley

Murray’s magic, Schumacher’s boots, FuoriConcorso comes of age, Eddie Jordan Racing, F1-inspired car flops and more

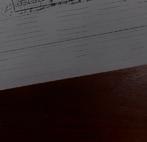

Designed in the late ’30s, Alfa’s voiturette was destined to deliver the first F1 Drivers’ Championship crown

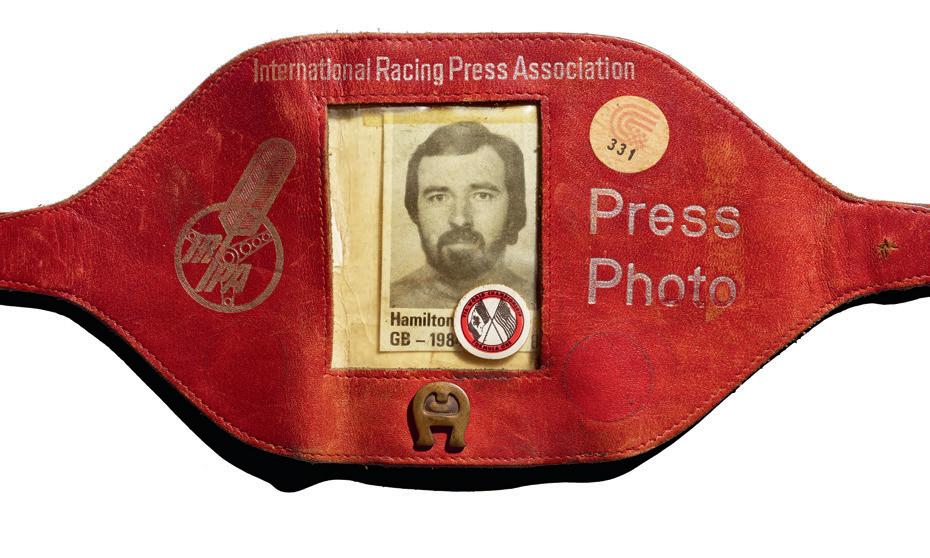

Maurice Hamilton gives a very personal account of his 50-year career covering motor sport’s premier formula

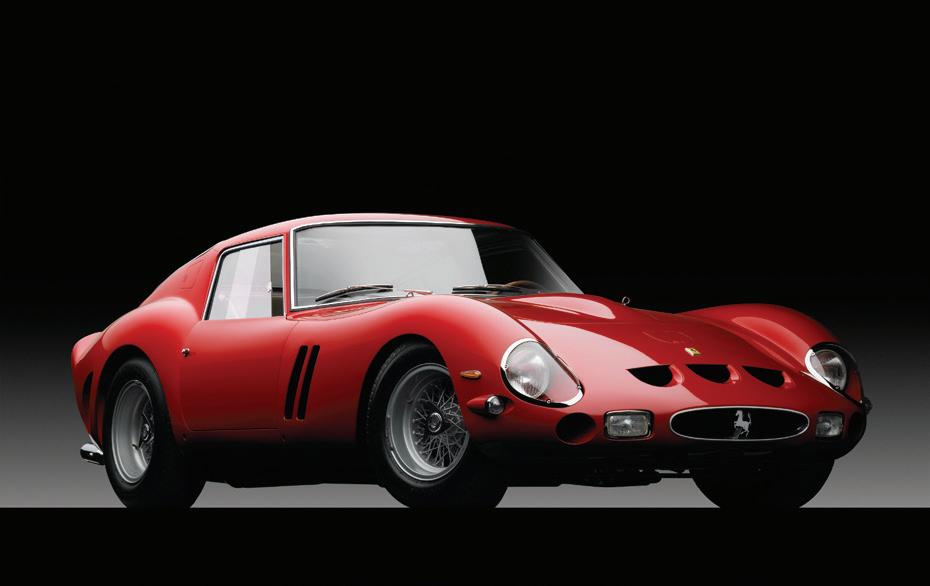

Ultimate F50 track car was set to dominate GT racing before rule changes scuppered Maranello’s plans

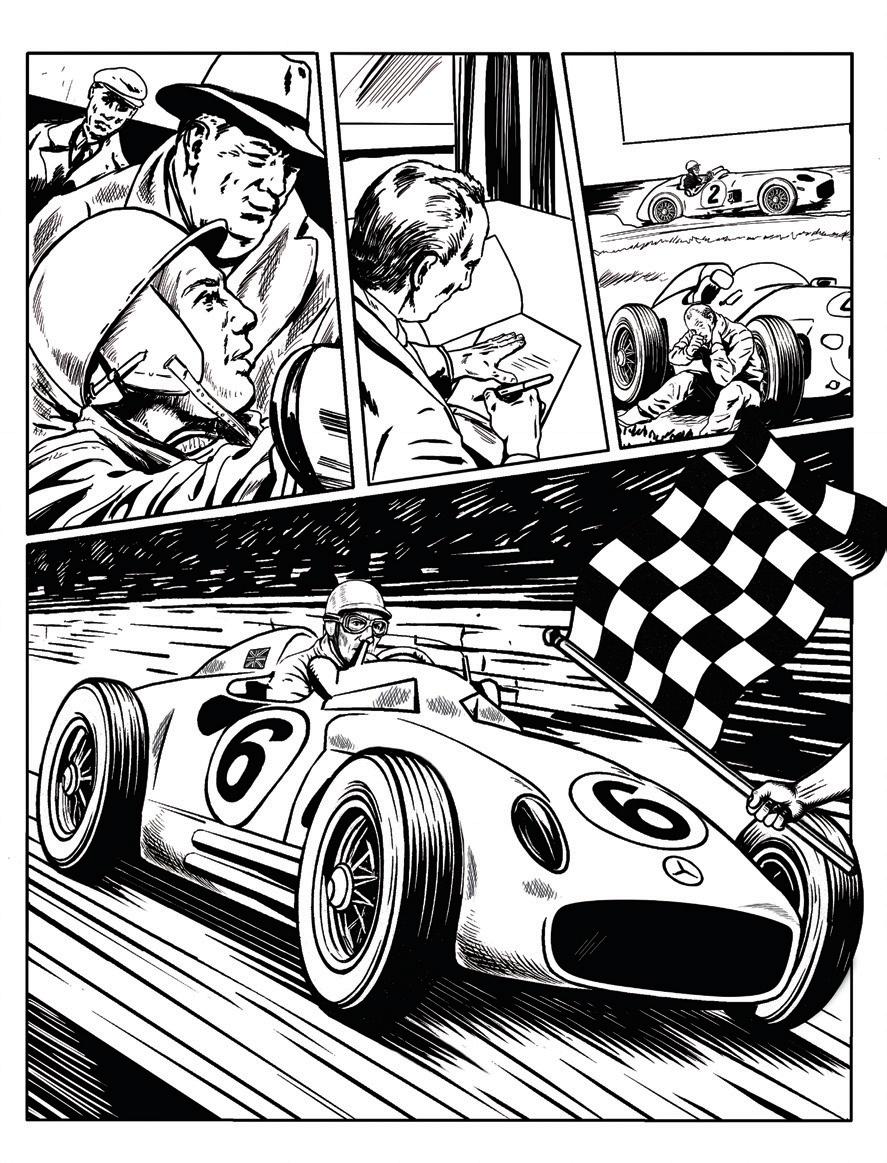

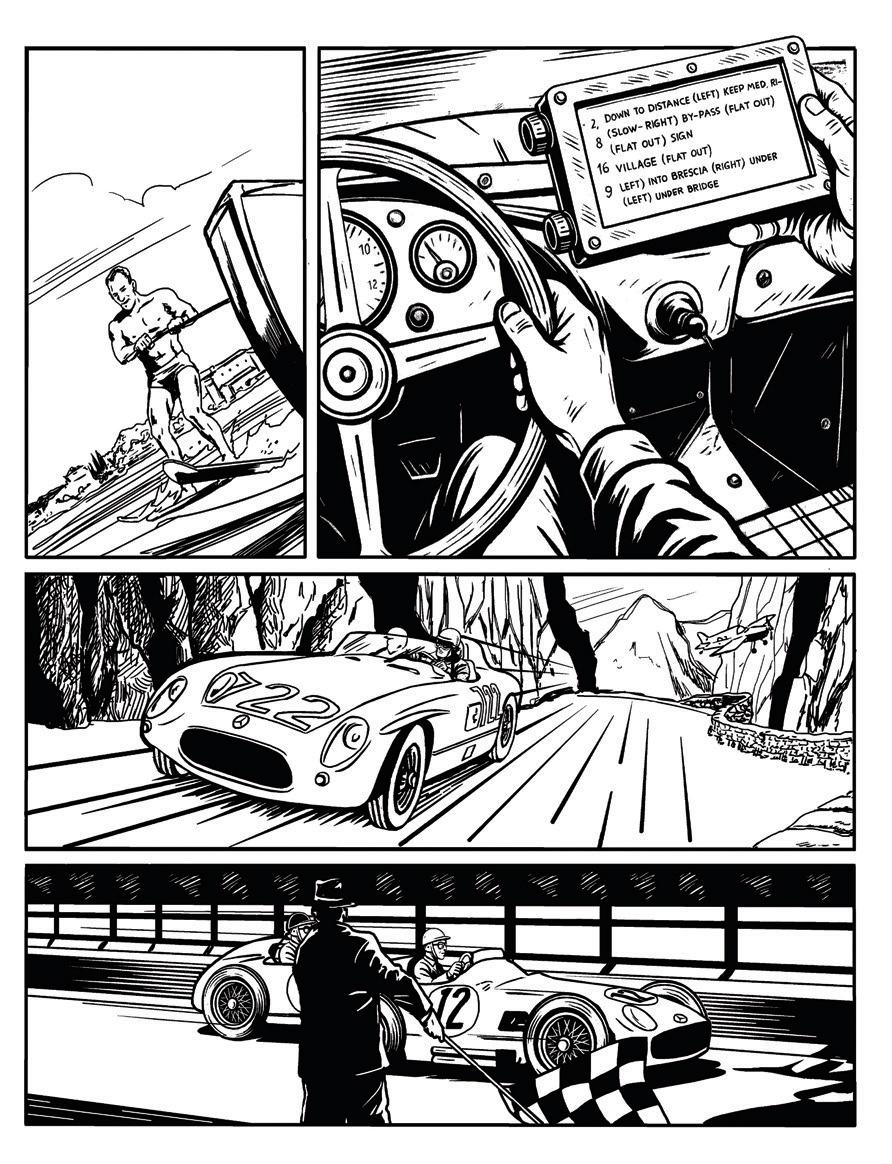

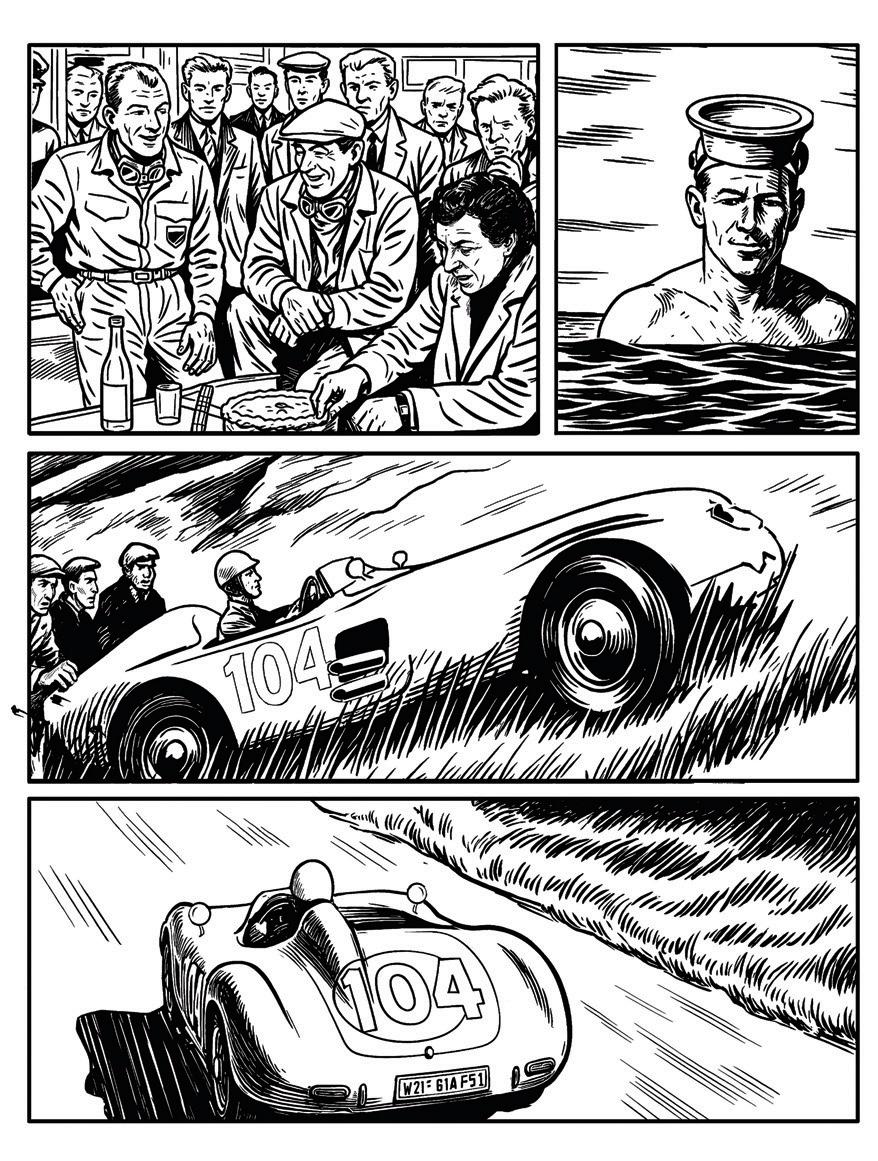

With Fangio at Mercedes, first Championship win, that Mille Miglia, that Le Mans, scuba-diving and more: ’55 had it all

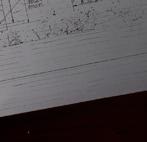

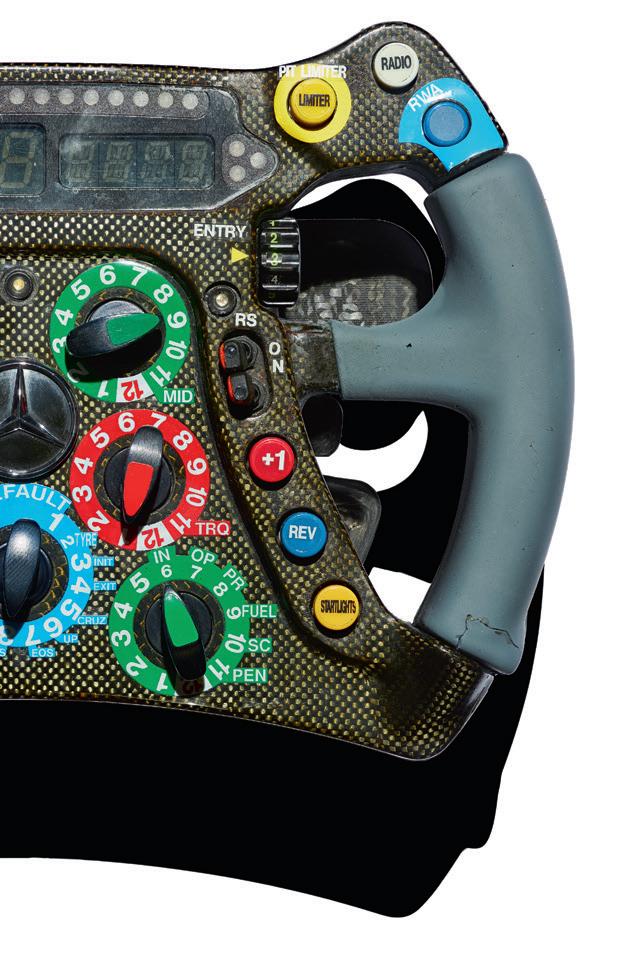

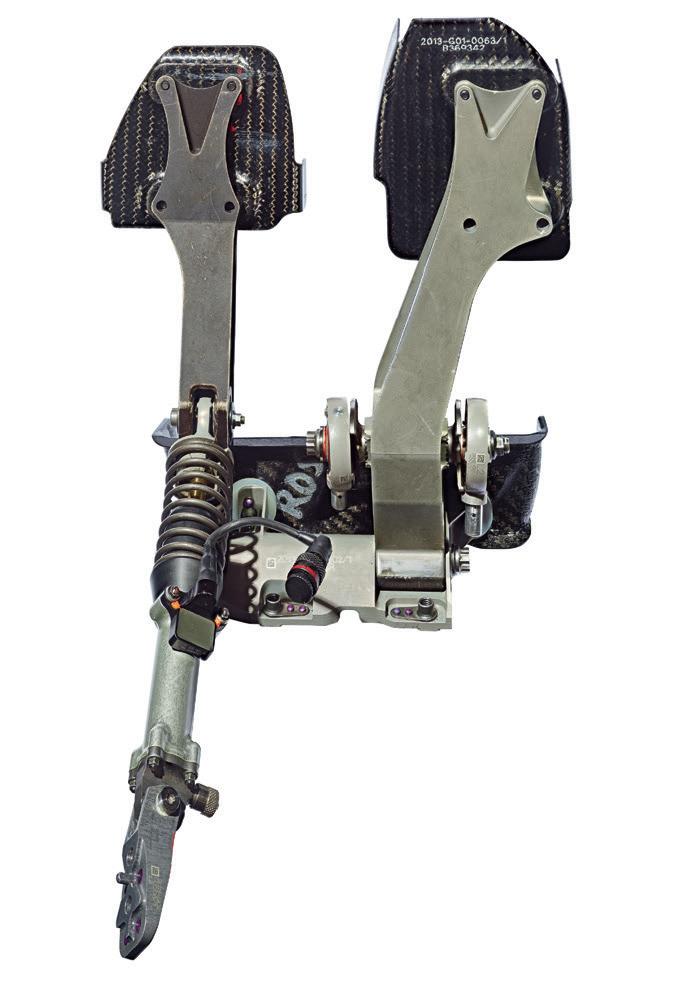

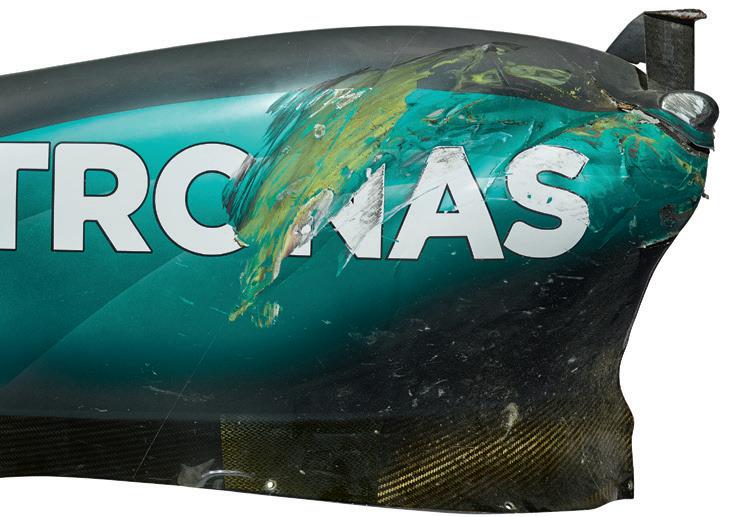

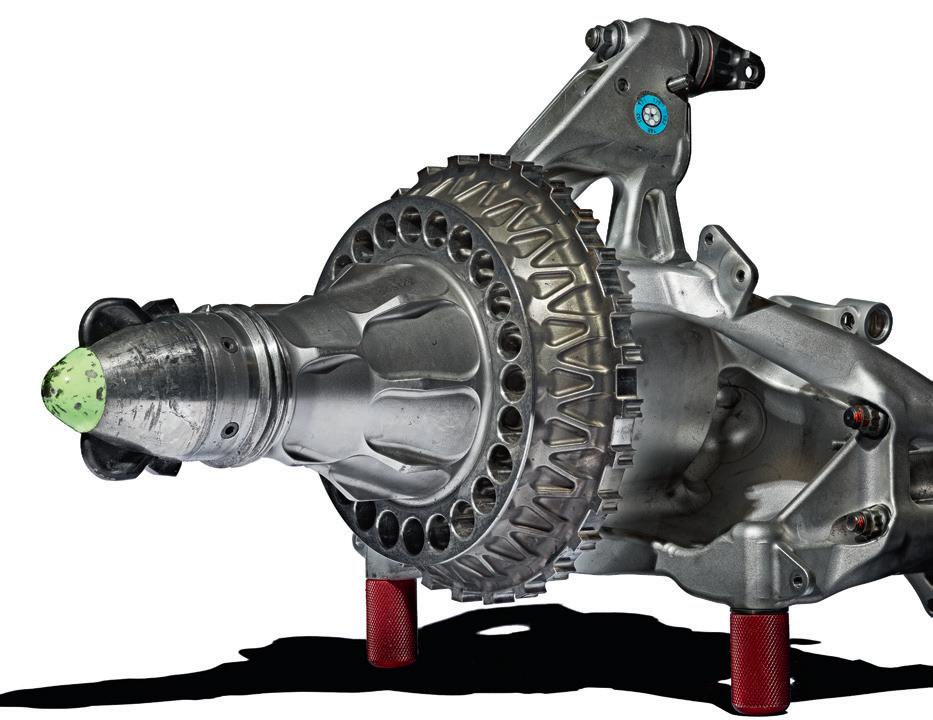

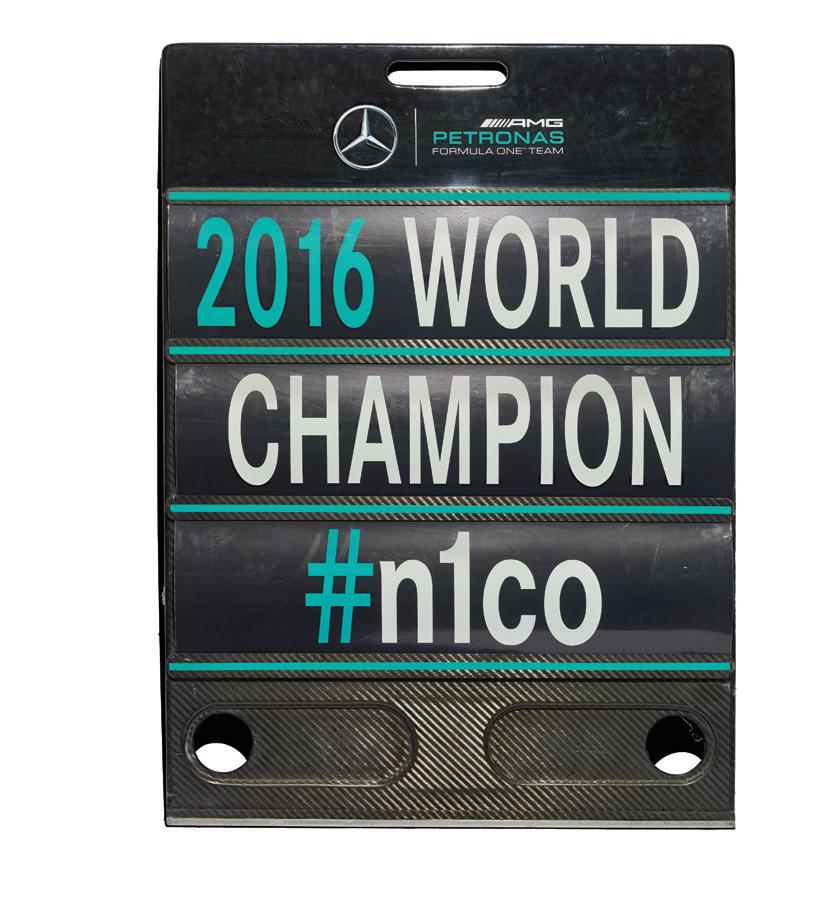

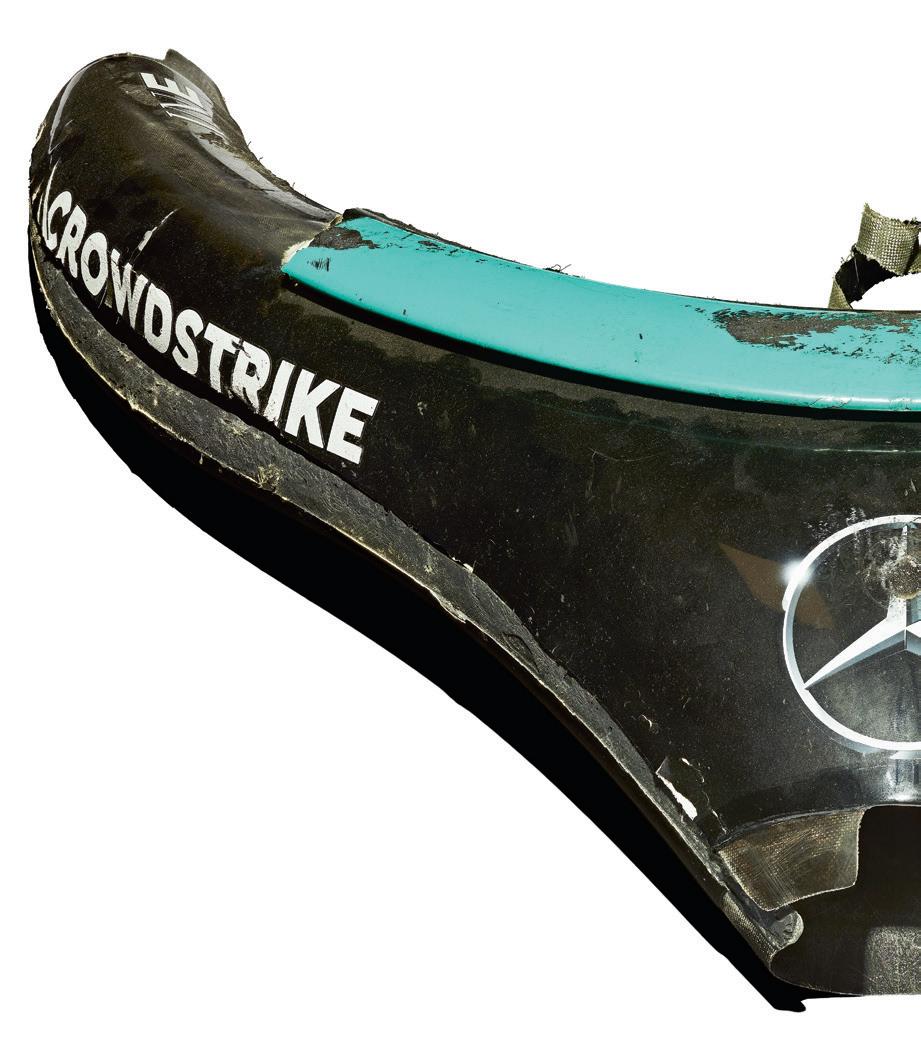

MERCEDES F1 OBJECTIFIED

The significant spoils of a component and memorabilia hunt through the Mercedes F1 factory warehouse

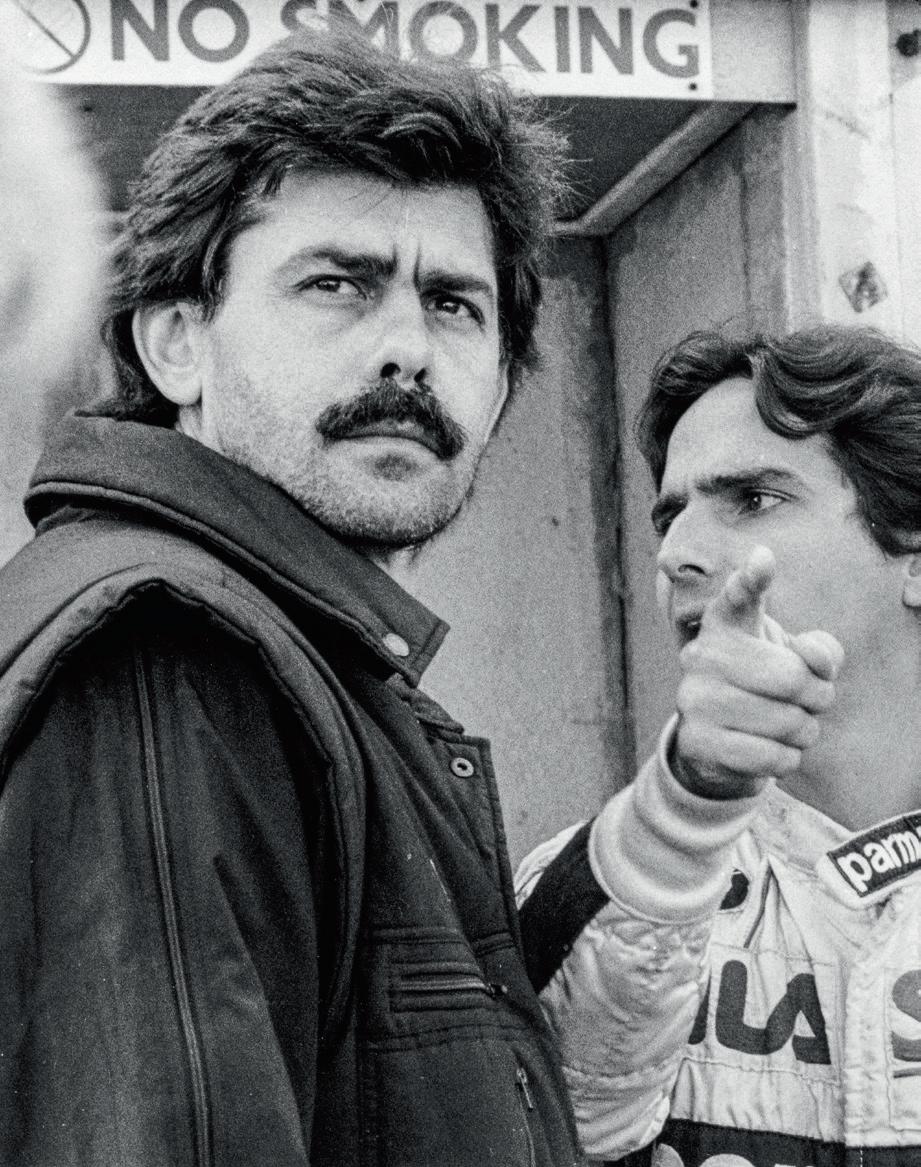

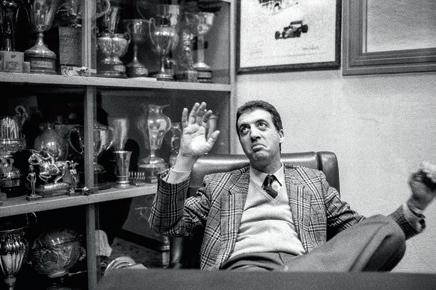

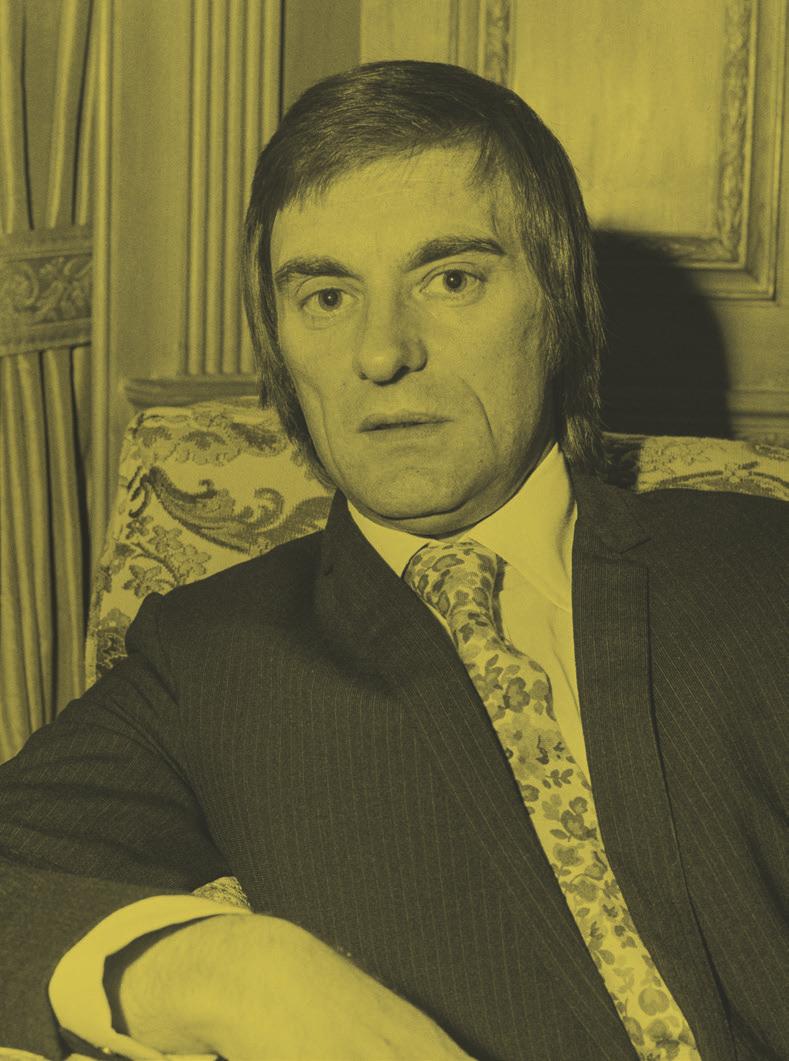

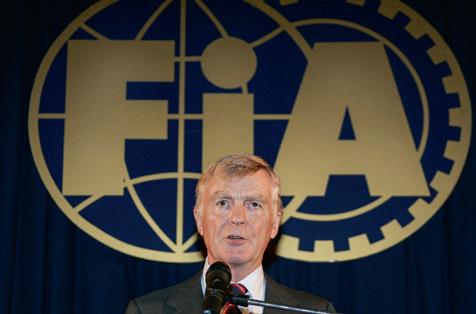

BERNIE AND MAX

Profiles on Ecclestone and Mosley, two F1 team owners who would come to be the most powerful men in motor sport

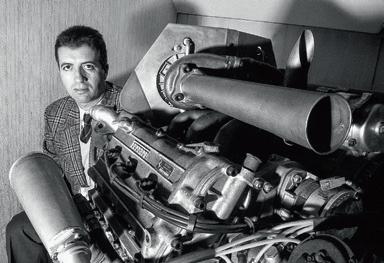

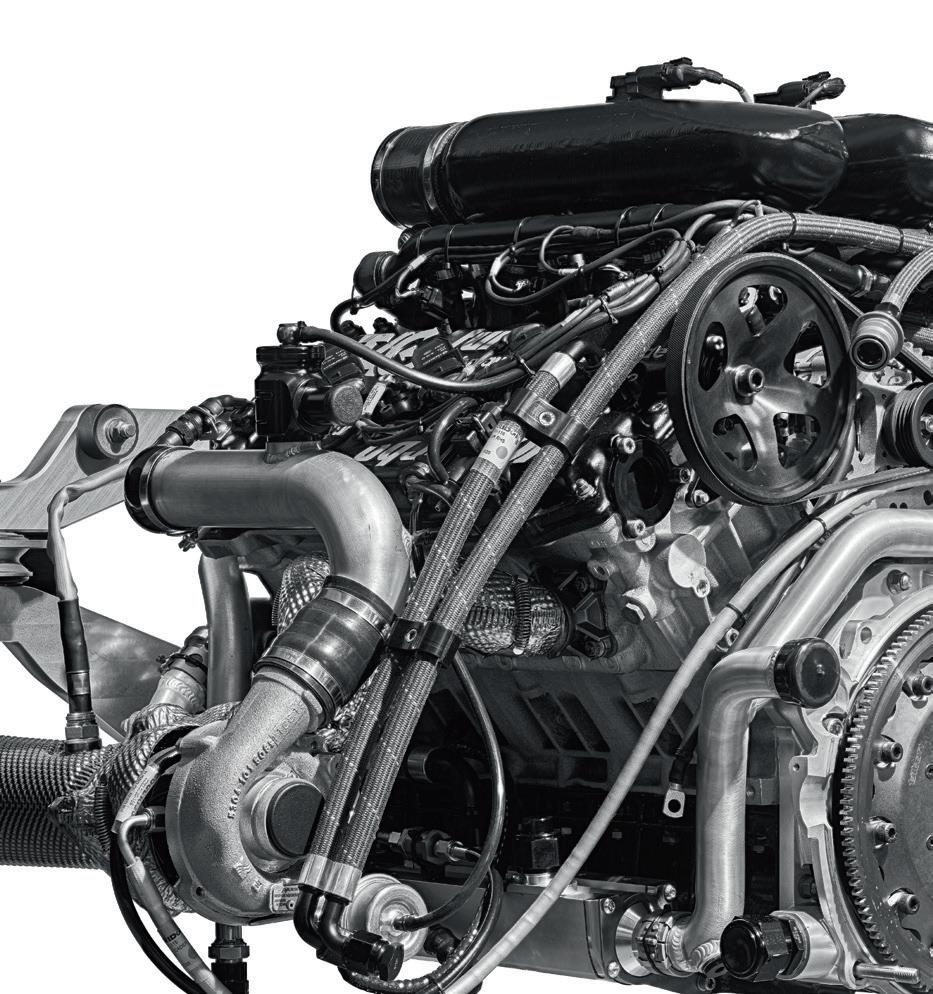

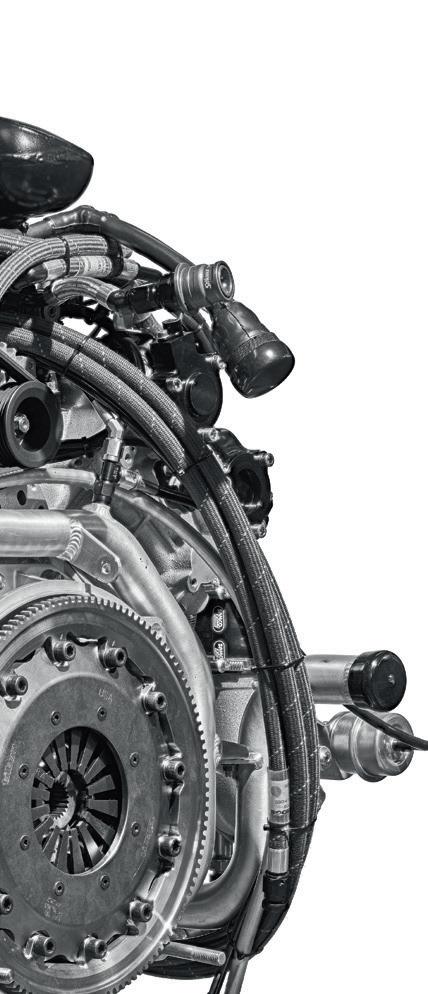

TAG TURBO PORSCHE 911

Under the skin of the 1.5-litre V6 TAG Turbo F1-engined tribute to McLaren F1 team’s 1980s prototype

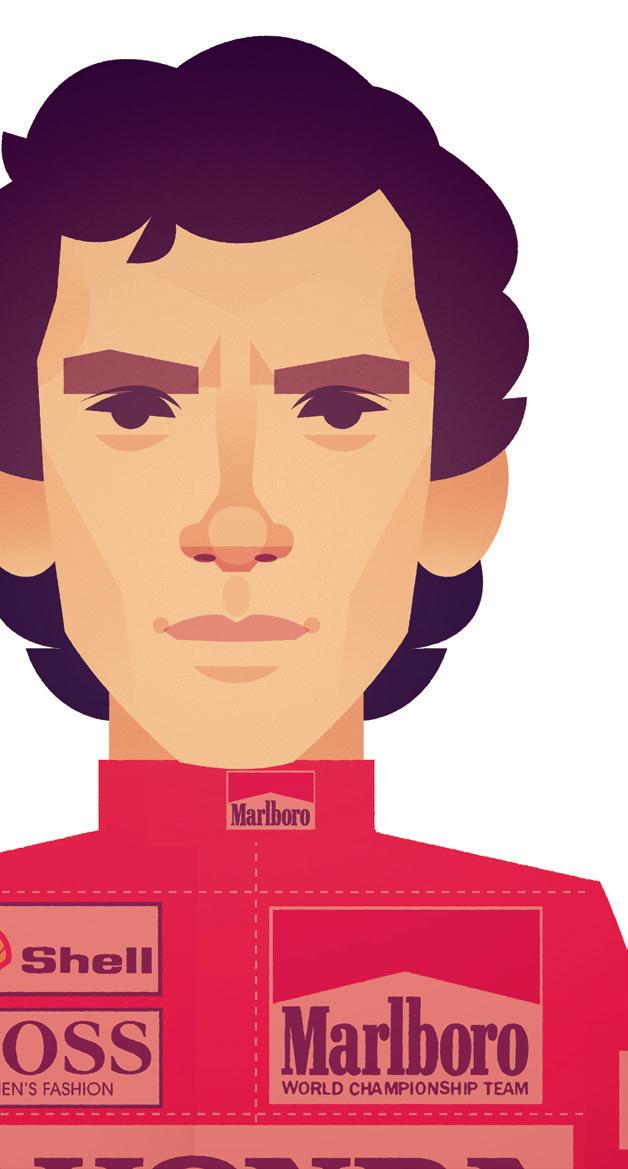

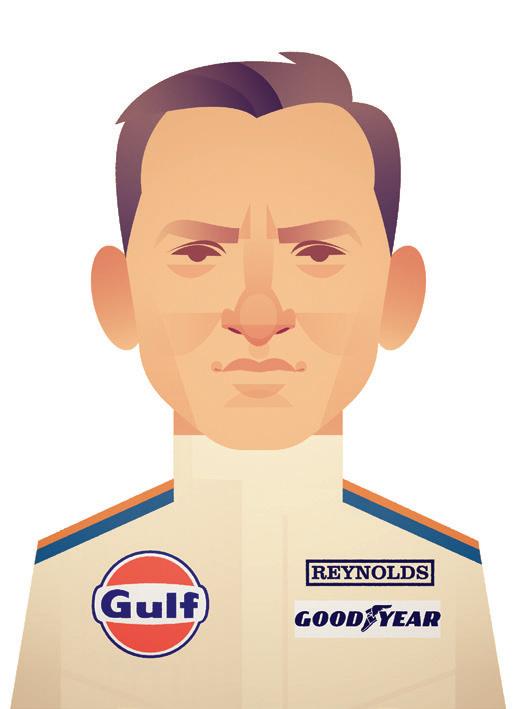

TOP 50 F1 DRIVERS

Statistics are one thing but they don’t tell the whole story; Formula 1’s greatest drivers assessed and [gasp] ranked

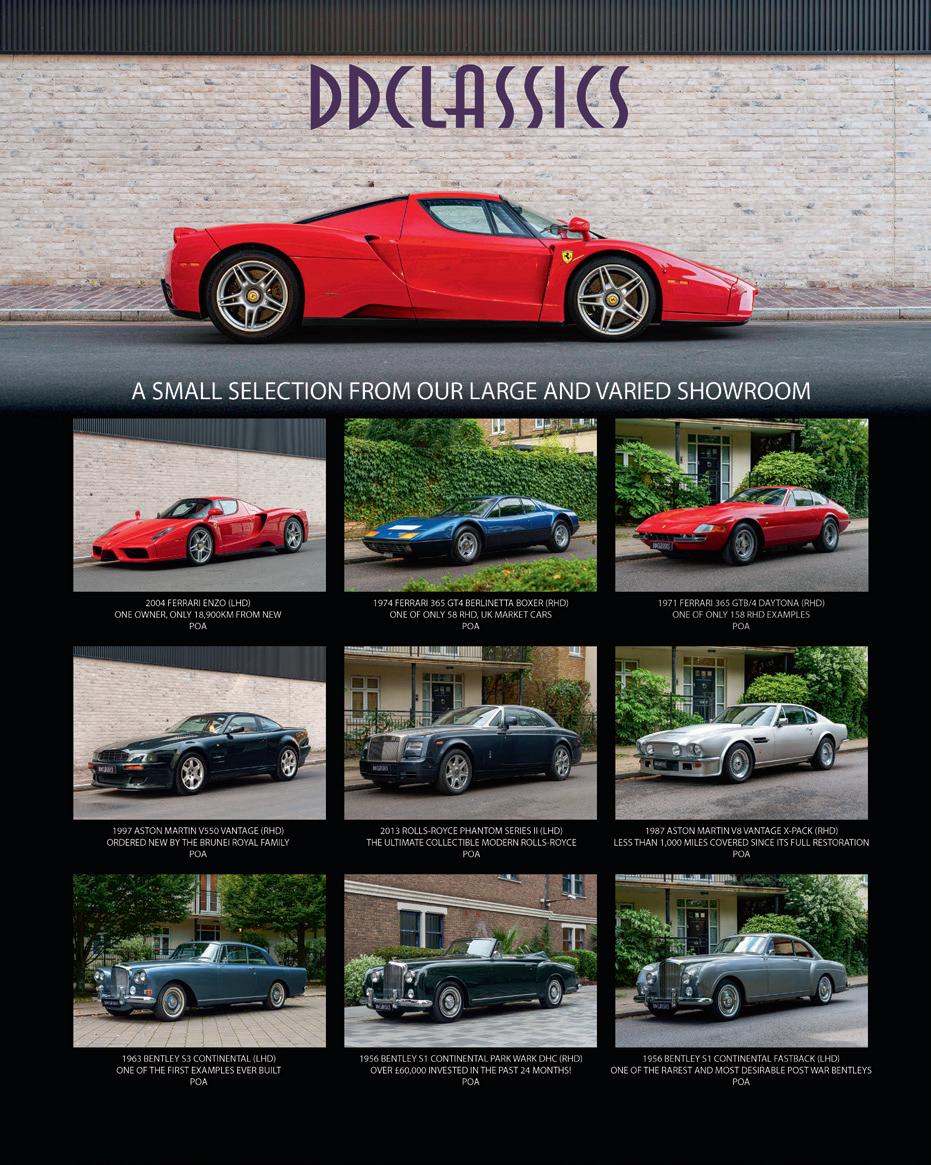

ACQUIRE

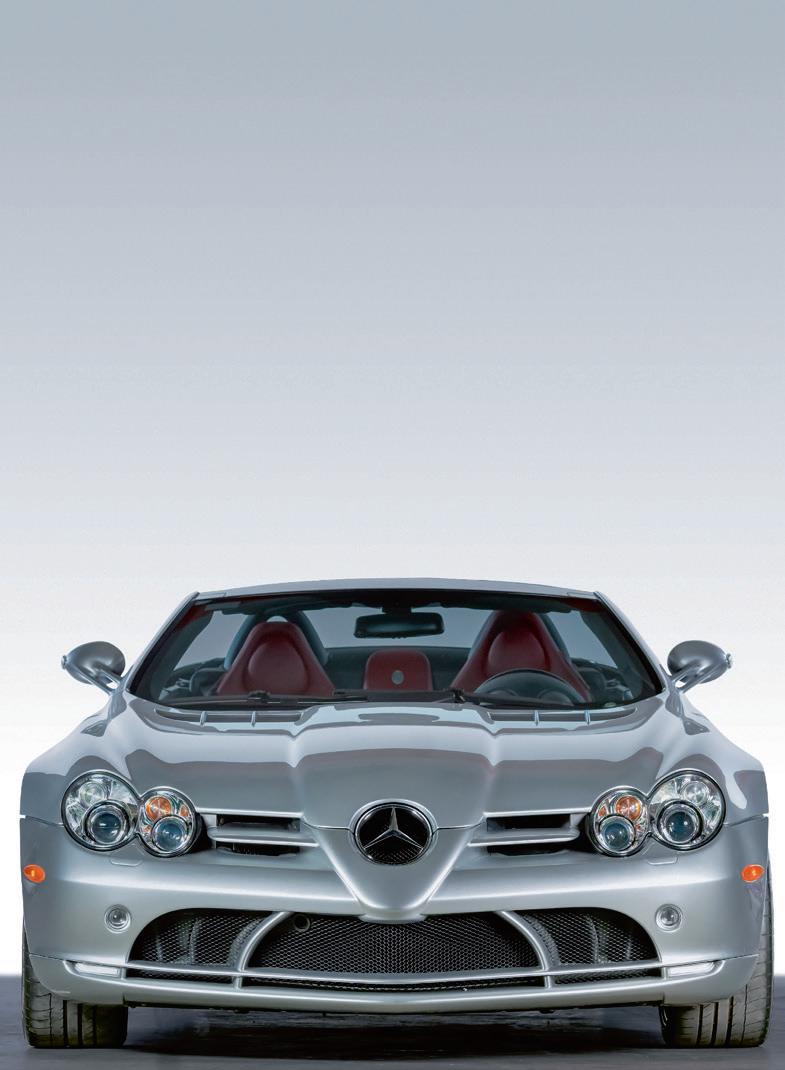

Buying a Mercedes SLR McLaren, collecting F1 parts, F1 art by Kevin McNicholas, best F1 watches, books, products and more

Our first themed issue, after six years and 26 issues of Magneto. It’s something we’ve talked about doing from the start, and 75 years of the Formula 1 Championship seemed the perfect opportunity. At last.

What we didn’t want to do was make this an encyclopaedia of racing cars through the years – there are plenty of those – or to make it boring for those who don’t care so much for motor sport or Formula 1 in particular.

So we’ve got a wide range of articles, each one with an F1 connection but not all directly about the racing. Personally, I love finding out about the people, the cars and the places associated with F1, but I’m not so bothered about the blow-by-blow race reports.

What I do urge you to do, even if you skim through everything else, is to read Paul Fearnley’s piece on Stirling Moss’s 1955 season line-by-line. We all know drivers of the period lived life to the limit, but this diary of the year in which Moss really proved himself, winning the Mille Miglia and enduring the Le Mans disaster, truly demonstrates the intense nature of his career. It’s a long read, so settle yourself down and prepare to have your mind thoroughly boggled.

Also, if you’ve been reading Magneto from the start, compare the featured modern Mercedes-Benz F1 parts with the BRM components similarly photographed for issue 1. How can you not love motor sport engineering...

David Lillywhite Editorial director

RM 43-01 FERRARI

Manual winding tourbillon movement

70-hour power reserve (±10%)

Baseplate and bridges in grade 5 titanium and Carbon TPT®

Split-seconds chronograph

Power-reserve, torque and function indicators

Case in microblasted titanium and Carbon TPT®

Limited edition of 75 pieces

Self-confessed petrolhead Joe has successfully competed in modern and Historic racing. Now Broad Arrow Auctions VP of Sales, EMEA, he is also a passionate collector and curator of motor sport memorabilia, and so he was in his element during a recent visit to the Mercedes Heritage Archive.

Motor-racing correspondent, commentator and acclaimed author Maurice has covered Formula 1 since 1977. Having attended more than 500 F1 races, he’s ideally equipped to deliver a personal account of the evolving Grand Prix experience.

Mat is the first Australian-based journalist to gain permanent Formula 1 media accreditation. He grew up in GP-hosting Adelaide in the 1980s. He’s worked in commentary and public relations, and is an award-winning journalist with more than 15 years of experience in the F1 paddock.

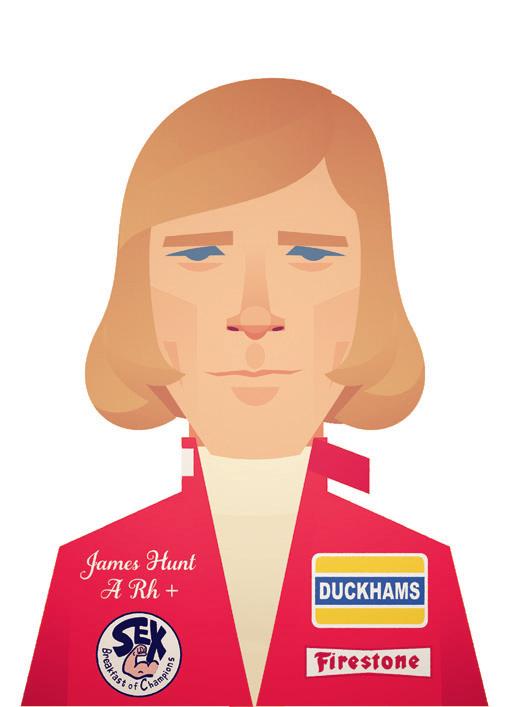

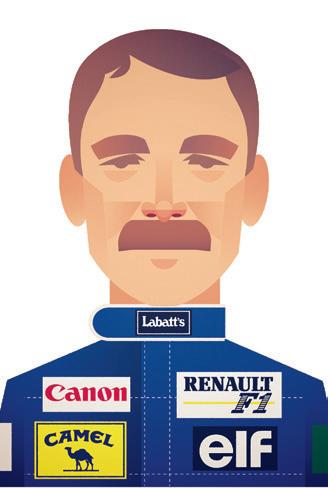

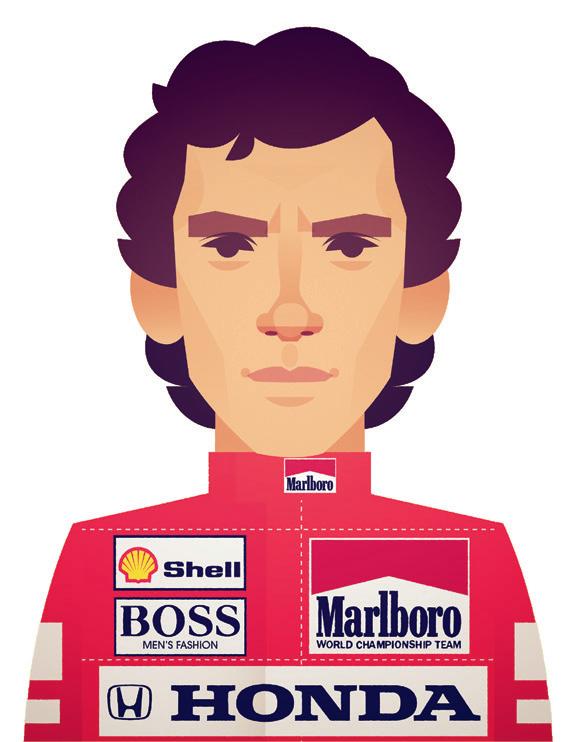

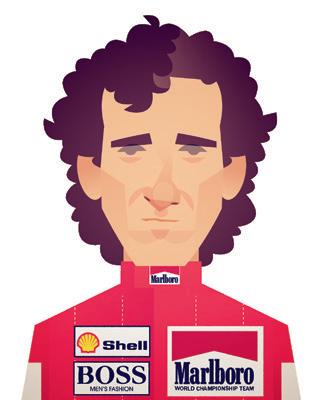

Manchester-born illustrator Stanley went from creating a bootleg White Stripes poster to staff-writer portraits for The New . We were thrilled when he agreed to illustrate 15 of our Top 50 F1 drivers feature; even more so when he threw in childhood heroes Alain Prost and Keke Rosberg.

Deputy editor Wayne Batty

Marketing manager

Rochelle Harman

Editorial director

David Lillywhite

Creative director Peter Allen

Staff writer

Elliott Hughes

Marketing and events

Jasmine Love

Managing director

Geoff Love

Managing editor Sarah Bradley

Designer

Debbie Nolan Accounts

Lifestyle advertising

Sophie Kochan

Contributors in this issue

Advertising sales Sue Farrow, Rob Schulp

Jonathan Ellis

Advertising production Elaine Briggs

Thomas Alexander, Jonathon Burford, Jordan Butters, Nathan Chadwick, Sam Chick, Stanley Chow, Mat Coch, Robert Dean, Richard Dredge, Paul Fearnley, Martyn Goddard, Rob Gould, Rick Guest, Maurice Hamilton, Richard Heseltine, Evan Klein, John Mayhead, Clive Robertson, Michael Alan Ross, Tim Scott, Damien Smith, Peter Stevens, Joe Twyman, Basem Wasef, Rupert Whyte, Brian Williamson

Single issues and subscriptions

Please visit www.magnetomagazine.com or call +44 (0)208 068 6829

Geoff Love, David Lillywhite, George Pilkington Unit 16, Enterprise Centre, Michael Way, Warth Park Way, Raunds, Northants NN9 6GR, UK

Printing Buxton Press, Palace Road, Buxton, Derbyshire SK17 6AE, UK.

Printed on Amadeus Silk and Galerie Fine Silk supplied by Denmaur as a Carbon Balanced product. Made from Chain of Custody certified and traceable pulp sources

Who to contact

Subscriptions rochelle@hothousemedia.co.uk

Events jasmine@hothousemedia.co.uk

Business geoff@hothousemedia.co.uk

Accounts accounts@hothousemedia.co.uk

Editorial david@hothousemedia.co.uk

Advertising sue@flyingspace.co.uk or rob@flyingspace.co.uk

Lifestyle advertising sophie.kochan2010@gmail.com

Advertising production adproduction@hothousemedia.co.uk

Specialist newsstand distribution Pineapple Media, Select Publisher Services

You’d have to be someone special to commandeer a one-of-three Ferrari F50 GT, hammer it around the Fiorano track in a sensationally quick lap time, and then leave your signature on the carbonfibre dashboard just to let the owner know you were there. Only the great Michael Schumacher could get away with that. See our F50 GT feature for more.

Photoshoot complete, the Alfetta is moved to temporary overnight storage in an off-limits workshop below the Museo Alfa Romeo. A brief ‘tour’ of the vicinity reveals no great secrets but does uncover unconventional treasures in the form of prototypes, motor sport marvels and oddball one-offs waiting to be prepped for possible display in the halls above.

© Hothouse Media. Magneto and associated logos are registered trademarks of Hothouse Media. All rights reserved. All material in this magazine, whether in whole or in part, may not be reproduced, transmitted or distributed in any form without the written permission of Hothouse Media. Hothouse Media uses a layered privacy notice giving you brief details about how we would like to use your personal information. For full details, please visit www.magnetomagazine.com/privacy.

ISSN Number 2631-9489. Magneto is published quarterly by Hothouse Publishing Ltd. Registered office: Castle Cottage, 25 High Street, Titchmarsh, Northants NN14 3DF, UK.

Great care has been taken throughout the magazine to be accurate, but the publisher cannot accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions that might occur. The editors and publishers of this magazine give no warranties, guarantees or assurances, and make no representations regarding any goods or services advertised in this edition.

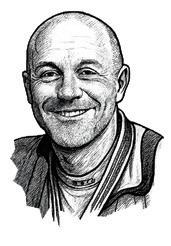

In 1934, Golden Miller became the only horse ever to win both the Grand National and the Cheltenham Gold Cup in the same year. The Golden Miller Racing Chronograph from Brooklands Watch Company in partnership with The Jockey Club features a buckle cast in an alloy made from an original horseshoe worn by the champion steeplechaser. Only 100 pieces will ever be made. The caseback features sapphires in the racing colours of Golden Miller’s owner Dorothy Paget – who was also the sponsor of ‘Bentley Boy’ Tim Birkin, the fastest supercharged car driver at Brooklands.

Be one of 100 lucky owners

Whether your passion lies in turf or track, wear an authentic piece of racing history on your wrist. Now available at brooklandswatches.com

Last year’s relaunch of the International Historic Motoring Awards, the most prestigious global awards night in the world of collector cars, was a resounding success. The 2025 edition will be held on Friday November 14 at the fabulous Peninsula London hotel. To nominate or to book a table, please visit www.historicmotoringawards.co.uk

The Magneto website reflects our love for the very best, the rarest and the most special production, prototype, competition and concept cars of every age. For all the news, features, reviews and event reports from the classic and collector car world, plus special offers, upcoming events and buying guides, visit www.magnetomagazine.com

Magneto’s Weekly Briefing is a curated weekly package of the news, features, event reports and previews that matter most to classic and collector car audiences. Our fortnightly Market Briefing newsletter previews upcoming events and adds expert analysis of auction results and prevailing market trends. Sign up at www.magnetomagazine.com

Don’t miss out on any issues of Magneto magazine. You can subscribe for one year for £54 including p&p (€62 or $68, plus postage), or two years for £94 including p&p (€108 or $120, plus postage). Magneto is delivered worldwide in strong cardboard packaging. Please visit www.magnetomagazine.com or +44 (0)208 068 6829

THE WORLD OF AUTOMOTIVE EXCELLENCE AT GUT KALTENBRUNN

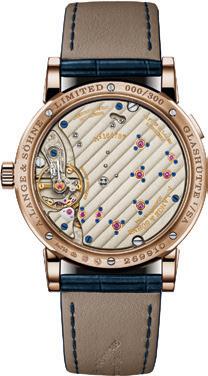

Including the Grand Arrival, Best of Show Parade, Car Club Displays, the Emerging Collectors, the Ladies’ Concours, the Junior Concours & Saturday’s Grand Depart which completes the showcase of timeless elegance, craftsmanship, and style at the Concours of Elegance Germany presented by A. Lange & Söhne.

For tickets visit concoursofelegancegermany.com

PRESENTED BY

While he is not the first-ever lightweighting devotee, Gordon Murray is one of the principle’s heaviest hitters. For 60 years, nearly all at the pinnacle of circuit- and street-machine creation, he has prioritised low mass, engineering purity and technical innovation with more single-minded consistency than any of his peers

Murray was just 19 years old when he built his first car. The Lotus Seven-like machine was powered by a modified 1.1-litre four-cylinder Ford Anglia motor. Mods included Weber side-draught carburettors, a ported cylinder head and a racier camshaft, among others. With power up to around 93bhp, Murray successfully campaigned it in various hillclimb events, sprints and National Class A Sports Car Racing in 1967 and ’68. He sold it before moving to the UK, so in 2017 he had his team build a replica from the original sketches.

In only Murray’s second year as chief designer at Brabham, the Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0-litre V8-powered BT44 became the first car he designed to win a Formula 1 race. Widely praised for its clean looks and effective aerodynamics, the innovative race car was also notable for its angular cross-section monocoque, downforce-inducing underbody skirts, semi-dry-sump gearbox and risingrate pull-rod front suspension. Carlos Reutemann drove the BT44 to victory at the South African, Austrian and United States Grands Prix. Team-mate Carlos Pace finished in second behind the Argentine at the 1974 season-ender at Watkins Glen, giving Brabham its first 1-2 under new owner Bernie Ecclestone. Revised for 1975, the Martini-liveried BT44B delivered two additional victories for the team.

BORN IN SOUTH AFRICA IN 1946, Ian Gordon Murray qualified as a mechanical engineer. He built and raced his own car, before setting off to the UK with a steely determination and no shortage of ability.

Turning up by chance to an interview for a role he never applied for, Murray got the job at Brabham in 1969. How it came about may have been fortuitous, but his 17-year tenure with the team –chief designer from ’73 – would yield two World Drivers’ Championships for Nelson Piquet, in 1981 and 1983 with the BT49 and BT52 respectively.

Joining McLaren in 1986 as technical director proved even more fruitful for Murray. Here, he oversaw the design and development of the 1988 Drivers’ and Constructors’ titlewinning MP4/4. That car’s immediate successors, the 4/5 and 4/5B, would repeat the feats in 1989 and 1990.

With 50 GP wins in the bag, and the Formula 1 world seemingly conquered,

Murray took his race-car nous to the streets, co-creating the brilliantly bonkers Rocket with friend Chris Craft, followed by the seminal McLaren F1 supercar, its legendary GTR competition derivative and the Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren.

For most, that would be mission handsomely accomplished, but he pressed on, establishing Gordon Murray Design in 2007, out of which flowed his iStream production process, T.25 and T.27 city car prototypes, stillborn projects for Yamaha, Toray Industries and TVR, along with the dormant flat-pack OX truck project.

Gordon Murray Automotive (GMA) followed in 2017. All its T.50s and T.33s have sold out almost instantly, with finished cars to date being met with critical acclaim. These latest chapters of his life story still reveal a singularly focused man who refuses to lighten up – even if that’s exactly what he’ll demand from the next GMA model.

Not forgetting the devastating pace of the 1978 BT46B ‘fan car’ and the 1981 BT49 that delivered the first Formula 1 title for a Murray-designed machine, the BT52 was perhaps even more significant as the first turbocharged car to win a World Championship. Adapting to 1983’s ‘flat-floor’ regulations and the introduction of fuel stops more effectively than rivals cemented Murray’s position as the era’s leading light in F1 car design. With its cleverly proportioned, dart-like shape and Peter Stevens-designed Parmalat livery, the BT52 remains one of F1’s most broadly admired and instantly recognisable machines.

The challenge to build a road car significantly lighter than a Lotus Seven was met with Gordon’s typically fastidious attention to detail and engineering purity. The clean-sheet Rocket design featured a purposefully retro-styled outer bodyshell of GRP sandwich construction attached to a steel spaceframe chassis. Precision-packaged within the tandem-seat body was a 1.0litre 20-valve Yamaha motorcycle engine that made 143bhp at 10,500rpm, and a five-speed sequential ’box and bespoke transverse final-drive unit incorporating a limited-slip differential, twin-speed axle and reverse gear. A kerbweight of just 370kg gave the Rocket a 0-100mph time of 10.0 seconds and a top speed of 145mph. Bonkers. Brilliant. Murray.

Epic. Legendary. Iconic. The F1 attracts every superlative. And rightly so. No other sports car has rocked the establishment as seismically as Murray’s ultimate driving machine. A masterclass in lightweighting with an all-carbon chassis, gorgeous body, brutal, unblown BMW 6.1-litre V12 and central-steer driving experience that has been the benchmark for decades. From the engine bay’s gold foil and the titanium throttle pedal, to the shaved-leather trim and the magnesium alloys, everything was designed to produce maximum function from minimal material. With a manual gearbox, unassisted steering and no ABS or even traction control, the F1 is peak analogue – a work of sublime engineering art that is still the fastest naturally aspirated car ever.

The spiritual successor to the F1 repeats that car’s winning recipe of all-carbon construction, naturally aspirated V12, three seats, central steering, advanced aerodynamics, compact dimensions and ultra-low mass. The T.50, though, takes advantage of 30 years of technical progress: better brakes, massively improved headlight performance, a smaller, lighter, even more powerful engine, modern system electronics, a full set of driver aids and visibly more effective fan-assisted ground-effect aerodynamics. There is also the not insignificant matter of sales performance. The F1 road car took years to find just 64 customers, while the 100 T.50 units were all allocated within 48 hours.

In the single-season wins vs races ratio stakes, only Red Bull’s RB19 scores higher than the MP4/4. Powered by Honda’s 1.5-litre turbocharged V6 RA168E motor, and designed by a talented team under the technical direction of Murray, the car was nigh-on unbeatable. With sheer mechanical grip, explosive engine power and wizard-grade proficiency in aerodynamic dark arts, the McLarens dominated at every track bar Monza. No doubt the pairing of Alain Prost and eventual champ Ayrton Senna played its part, too, with the duo sharing the team’s 15 victories seven to eight, respectively. The momentum continued well into 1990, culminating in three consecutive double championships for Murray and McLaren.

The latest landmark GMA creation is Gordon’s love letter to the “cleanly styled and gorgeously proportioned” sports cars of the 1960s. Powered by a derivative of the T.50’s 3.9-litre Cosworth V12, making 609bhp and capable of revving beyond 11,000rpm, the T.33 Spider promises an immersive open-top driving experience accompanied by the aural delights of a ram-induction intake mounted just at driver’s ear height. With 60 years of world-beating technical know-how hard-wired into its core, fuss-free retro-modern styling, advanced aerodynamics, a trademark-low 1.1-tonne dry weight, blistering performance and limited production, who would dispute the T.33 Spider’s instant collector status?

Symbolic gold stars and dragons adorn this bespoke footwear from Schuey’s penultimate season in F1

THESE BESPOKE BOOTS WERE produced by Alpinestars for Michael Schumacher, and they were used in his penultimate season of Formula 1 in 2011. They feature seven gold stars on the toes to represent his World Championships, as well as delicate Chinese dragons on either side.

The dragons – which represent power and strength – were adopted in 2006, when Schumacher ran them on his helmet. As a wider part of his personal branding they later appeared on merchandise clothing and other customisable areas of his race kit, such as the boots seen here.

In 2011 he raced to 11 points, scoring finishes that helped the Mercedes team lay the foundations for the superpower that was set to emerge in the coming years. These boots are the only custom pair to be retained by the Mercedes Heritage Archive, which holds in excess of one million relics that relate to the team. A further exposé on this incredible vault starts on page 112.

want your award nominations!

You can nominate for the 2025 IHMAs – and there’s a new category for Historic racing

Words David Lillywhite

THIS PAGE The prestigious IHMA award ceremony will take place at the Peninsula London hotel on November 14.

WE HAVE NOW OPENED OUR nominations, ticket bookings and sponsorship opportunities for the International Historic Motoring Awards sponsored by Lockton, which once again take place at the stunning Peninsula London hotel on Friday November 14, 2025.

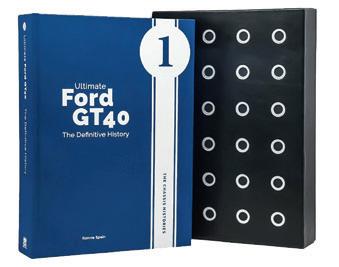

Following the relaunch of the awards last year, there will be further surprises for 2025. We’ve also added Race Series of the Year, changed Young Achiever of the Year to Rising Star of the Year, and incorporated Book of the Year into Best Use of Media. The full categories are listed here. As previously, Car of the Year will be voted for by Magneto readers. We’ll publish the shortlist of contenders on the IHMA and Magneto websites. The

rest, with the exception of the Lifetime Achievement Award, will be judged by an independent panel of experts.

This is one of the best nights out in the collector car world’s calendar, bringing together some of the most influential collectors, organisers and specialists in the world. Being shortlisted or winning an award carries global kudos. Don’t miss out on your chance to take part in some way.

To nominate or for more information, see www.historicmotoringawards.co.uk.

To book a table (note that we sold out well ahead of the event last year), contact events manager Jasmine Love at jasmine@hothousemedia.co.uk.

To talk about sponsorship opportunities, contact managing director Geoff Love at geoff@hothousemedia.co.uk.

Rising Star of the Year

The person under 30 years old who has demonstrated outstanding work in the collector car world.

Personal Achievement of the Year

The person who has made a significant difference to the collector car world through their personal endeavours.

The car – classic or new – that has made the greatest impact on the collector car world this year.

Most significant one-off or low-volume new car launched since November 2024.

The collector car specialist that has made the most significant contribution to the collector car world, or that has achieved something new or special for its own benefit, since November 2024. This goes across all genres, from car sales to restoration and parts supply.

Restoration of the Year

The best classic restoration completed since November 2024, demonstrating skills, understanding of history, provenance and overall achievement. Open to all eras and types of collector car.

The Historic race series, whether national or international, in any country, that has demonstrated particular success and/or innovation since November 2024.

The car club that has made a significant achievement this year.

Industry Supporter of the Year

The individual or organisation that has made the greatest contribution to the collector car world.

Museum or Collection of the Year

The museum or collection that has made the greatest achievements this year.

The best publication, article, website, video, film, social media or any other type of collector car-focused media.

The best collector car event that had its inaugural running after November 2024.

The collector car rally or tour that has demonstrated innovation, participant satisfaction or significant achievement.

The world’s best motoring event, whether a festival, concours, one-marque gathering, anniversary celebration or other collector car show.

The best collector car competitive motor sport event, from the disciplines of racing, hillclimbing, stage rallies, sprints, drag racing and more.

The person who has spent their working life involved in the automotive world, and who is judged to have made significant differences to that world along the way.

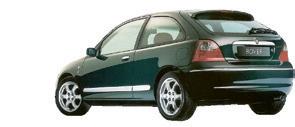

Formula 1 teams and stars have always added showroom glitz to road cars. Some, such as the Renault Clio Williams, are successful – but some aren’t, or else they are just plain odd. Here are a few of the latter…

ROVER 200 BRM (1998)

Qualifying performance?

Leading credentials?

To inject some Max Power magazine machismo into the distinctly Daily Express 200, Rover decided to pay tribute to a Formula 1 team that helped the brand take a gas-turbine car to Le Mans. A team that stopped racing before most of the target demographic were born...

Sprightly 143bhp variablevalve-timed K-series engine, Torsen limited-slip diff, closeratio ’box and lower, stiffer suspension: 500 planned, 1100-plus produced.

Sliding off the back of the grid?

Pole or own goal?

The BRM livery-referencing bright orange grille made the Rover 200 BRM look like a baboon in need of ointment.

(2004)

While it was not the first Schumacher Fiat (there is the Seicento, too), in a desperate bid to improve the Stilo’s fortunes the brand slapped the German’s name on an horrendously loss-making family hatch. Perhaps fortuitously, it was released just as Schumi’s F1 stranglehold began to slip...

The 170bhp 2.4-litre five-cylinder engine from the Stilo Abarth gave the newcomer some oomph, but the best was saved for the GP version. That had Prodrive suspension tweaks, a fruitier exhaust and 18-inch alloy wheels. Fiat built 3500 of all kinds.

The Viva was always a smart-looking car, but it was not exactly a sprightly one against sportier options from the likes of Ford. Vauxhall turned to Jack Brabham to extract the maximum from the model’s 1159cc four-pot for some youthful dynamism.

MERCEDES-BENZ A160 EDITION HÄKKINEN/ COULTHARD (1999)

McLaren-Mercedes was in its Newey-era pomp, so what better way to celebrate than with 250 special editions dedicated to drivers David Coulthard and Mika Häkkinen? Er...

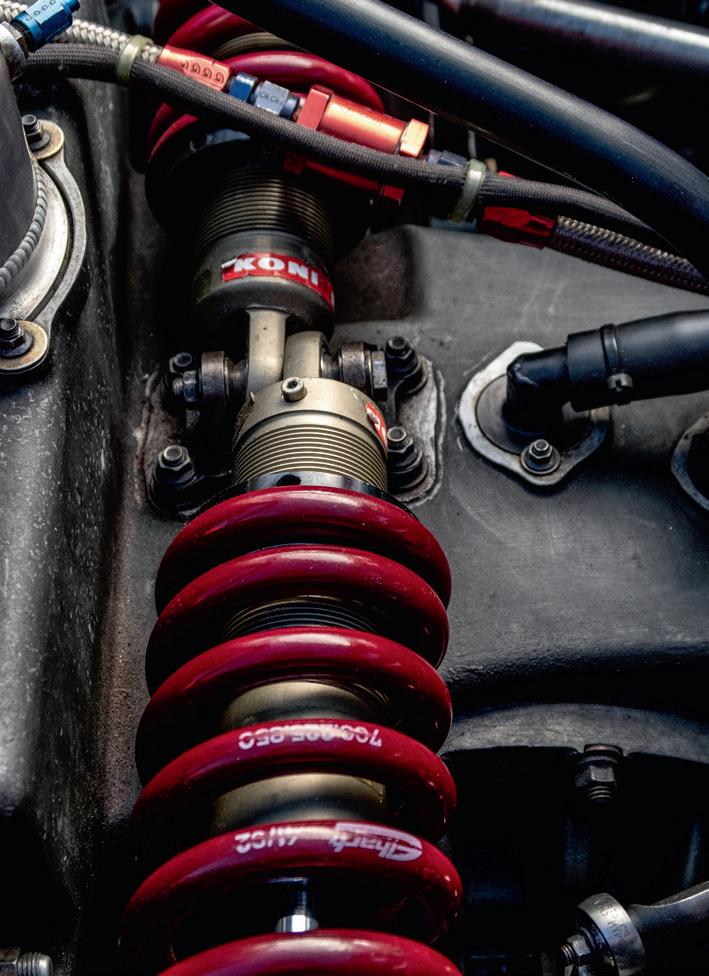

Modified head and manifold, twin Stromberg carbs and a zingier exhaust gave 78bhp. Visual tweaks and Koni dampers among options.

170bhp in a large hot hatch wasn’t much to write home about in 2004. Tellingly, its

When new, it missed its target demographic completely: it was largely bought as a daily driver by British roadster-owning retirees. But more fool the young – it was an engaging steer and is now collectable.

Prodrive’s suspension tweaks woke up a somewhat woolly chassis, but few bothered to care. Of the 200 that came to the UK, 30 are now taxed and MoT’d.

Sporty stripes down the sides and ‘Brabham’ plastered across the car must have confused people in the late 1960s. That, and paying more than an entire Ford Cortina’s worth for an extra 9bhp (£699 vs £730).

With its garish decals and dog’s lipstick interior, at least the A-Class’s nemesis, the elk, would have run the other way – in disgust.

Merc built four prototype twin-engined A190s with 4WD, 250bhp and a 5.7second 0-60mph. Why couldn’t we have had that, rather than a limp, 102bhp 1.6-litre four-pot?

We’d rather commute via the elk, frankly.

Although Motor Sport’s review noted the extra handling nous, the best it could come up with in summary was ‘creditable’. Hardly effusive, is it?

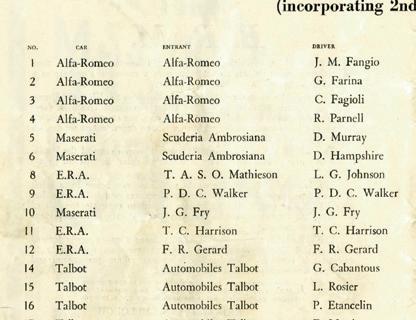

Who’d have known the significance of F1 in 1950?

75 years ago the arrival of the Formula 1 World Championship made motor sport history. If only people had realised...

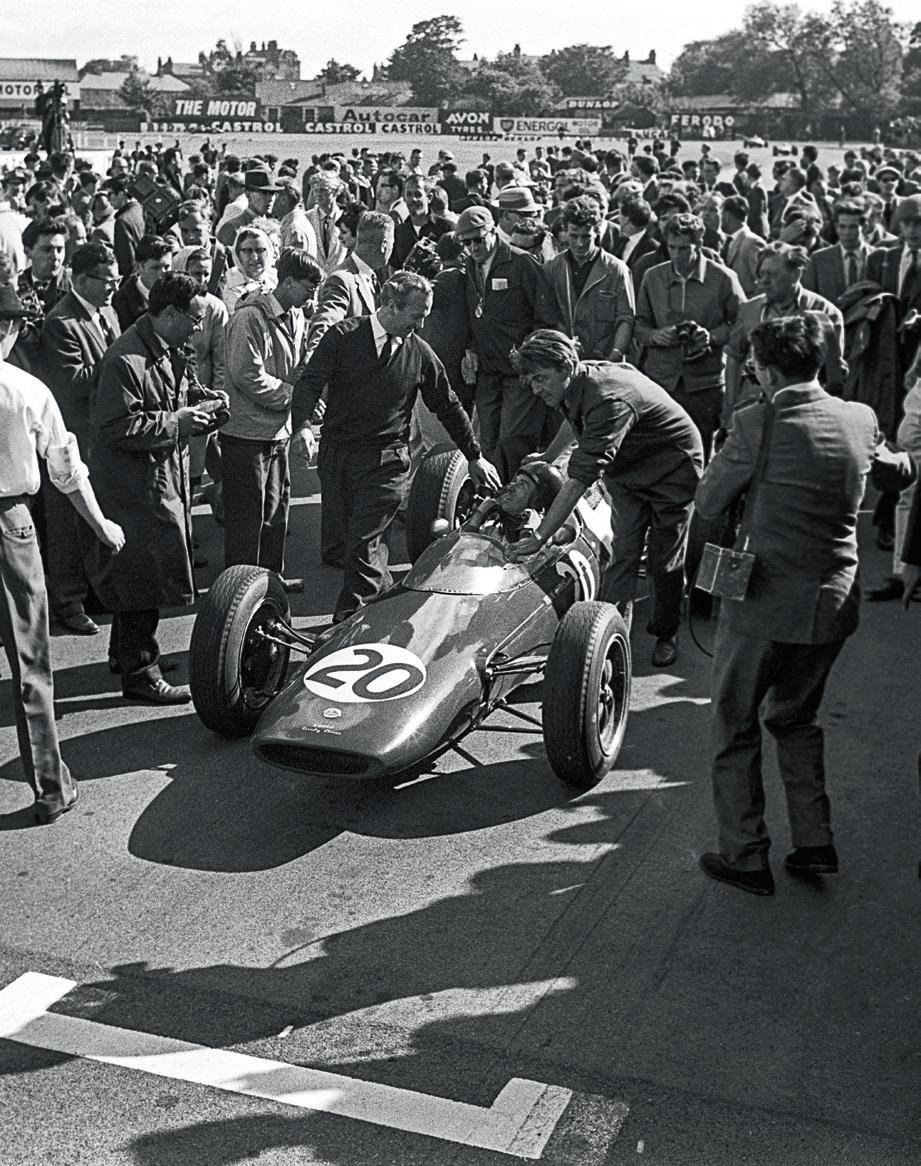

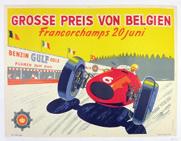

THE FIRST OFFICIAL FIA WORLD Championship Formula 1 Grand Prix took place on Saturday May 13, 1950, at the UK’s Silverstone Circuit – but at the time the ‘Championship’ aspect seemed to have gone virtually unremarked upon, despite a visitor attendance of more than 150,000.

The programme made no mention of the new points system, although it described the race as “the greatest occasion in the history of motor racing in this Country”. This was also the first (and so far last) time that a reigning sovereign “graciously consented” to attend a motor race.

Now, 75 years on, we can look back on the significance of this race. The new World Championship introduced the points-scoring system for the very first time, with seven prominent Formula 1 races selected in Britain (Silverstone), Monte Carlo, America (the Indianapolis 500), Switzerland, Belgium, France and Italy.

Points were awarded to the top five classified finishers, with eight going to the winner, six to the runnerup, four for third, three for fourth and two for fifth, with an extra point being awarded for setting the fastest lap. A driver’s four best results were then totalled up – and the one with the most points would be crowned as the World Champion.

At the time, though, the focus was on the attendance of His Royal Highness King George VI, Queen Elizabeth, Princess Margaret and the Earl and Countess Mountbatten of Burma. The royal party was introduced to the drivers, and a

special Royal Box was constructed for them to watch the action from.

Among the 21 drivers taking part were Prince Bira of Siam – a member of the Thai royal family – and Baron Emmanuel ‘Toulo’ de Graffenried, a Swiss nobleman who had won the previous year’s non-Championship British Grand Prix in a Maserati.

Ferrari had chosen not to attend the Silverstone event, and so the race was dominated by the all-conquering Alfa Romeo factory team, which dispatched four of its supercharged 158s to Silverstone. Juan Manuel Fangio, Nino Farina and Luigi Fagioli would race three of these, while the fourth car was kindly ‘loaned’ to local ace Reg Parnell. One such ‘Alfetta’ is featured further on in this issue of Magneto

Fangio subsequently retired with engine problems, but the other three Alfas took the podium, with Farina earning the maximum nine points and £500 of prize money. Later that year he became the very first Formula 1 World Drivers’ Champion.

This year, the Silverstone Circuit will celebrate 75 years of the Formula 1 World Championship with an unprecedented display of titlewinning machinery driven by all 34 of the sport’s World Champions, at the Silverstone Festival on August 22-24. It will showcase cars used by Fangio, Jim Clark, Jackie Stewart, Niki Lauda, Ayrton Senna, Michael Schumacher and Lewis Hamilton, all the way through to Max Verstappen’s titlewinning 2024 Red Bull RB20. More details at www.silverstone.co.uk.

The 1980s saw the start of a period of great change at Maranello – and Piero Ferrari was destined to oversee the next chapter

IN LATE JANUARY 1987, CAR AND Driver magazine editor Don Sherman called me, asking me to be in Modena the following Friday to team up with Formula 1 journalist Peter Windsor. Peter had wangled an exclusive interview with Piero Lardi Ferrari. This, he stressed, was a big deal.

Piero, son of Enzo Ferrari and Lina Lardi, had been working for Ferrari in the purchasing department. Due to growing recognition from his father, he had recently been promoted to a Gestione Sportiva position at the F1 racing department, but still kept away from the media spotlight. Peter sold the story to Ferrari on the recent arrival of John Barnard in the Ferrari F1 camp and the IndyCar racing project planned for 1988.

I’d never worked with Peter, and he wasn’t a regular C&D contributor, but

upon meeting up in Modena he briefed me on what he hoped would happen. This being Italy, there were no guarantees. As it turned out, Piero arrived in a red Alfa saloon complete with a driver, and during the long day that followed we were guided around the racing department where we were shown the F1 and IndyCar prototypes. Both had been designed by Gustav Brunner, and Peter discussed many technical aspects with the engineers. It was noted that Mr Barnard would only tweak the 1987 cars. Piero explained about the recent change in drivers, with Austrian Gerhard Berger joining the Scuderia due to Stefan Johansson’s criticism of the 1986 car.

In sit-down interviews Piero talked of the past and his relationship with his father. He mentioned that his dad said he should stay away from racing

SPREAD

Piero Lardi Ferrari was ascending the family ladder in the late 1980s, as Ferrari left behind the Enzo era on its way to becoming the road and track monolith it is today.

cars and be a farmer (he had grown up on a small farm). However, Piero had always enjoyed working on the farm machines, as well as helping a local motorcycle mechanic in his youth. After reading business studies at Bologna University, he’d joined Ferrari SpA working in admin. He then graduated to the racing department, and by 1987 he was working closely with Mauro Forghieri to engineer the radical step of hiring Barnard to design the new chassis despite the latter’s refusal to move to Italy. Piero stressed that Il Commendatore had the final say on all racing matters, but that he had supported the plan on the grounds of ‘whatever it takes to win’.

During this tour of the factory and design studios, I shot reportage images. I chose black-and-white film, because I needed to travel light and stay in the background, all subject to challenging lighting conditions. I think they really

forgot I was snapping away, so engrossed were they in the interesting topics of the interviews. By late afternoon Piero suggested that, as our dinner reservation was quite close by, we had time to look at Enzo’s original office in the old factory.

We were whisked through the traffic to a brick warehouse in the heart of Modena. Entering through a wicket door, we found a space full of storage racks. Piero lead us into a darkened room and hit the light switch to reveal an office with two facing wooden desks. The walls and shelving were loaded with trophies and artwork. He explained that one desk was Enzo’s and the other was that of his deceased son Dino – Piero’s half-brother. The office was a time capsule, and we were told that Enzo kept Dino’s desk just as his son had left it before he died of muscular dystrophy in 1956. As any photojournalist would do, I asked if I could photograph the room; to my surprise, Piero said I could go ahead.

We must have spent nine hours with him, without any PR navigating us around the factory and restricting my photography. The session ended at a restaurant that specialised in a balsamic vinegar menu. It had won a competition for the most innovative dishes using the local vinegar. In fact, all three courses featured the brew, ending with strawberries and ice cream bathed in a gran cru of balsamic. A nice touch that highlighted Mr Ferrari’s friendly nature was that our driver was invited to have dinner with us.

Peter Windsor’s story appeared in the May 1987 Car and Driver. The F1/87 cars were not a great success, chalking up only three wins that season, while

the IndyCar project never materialised. Later that year I returned to Maranello to photograph the last Enzo-era car, the F40, and I was granted a brief shoot with the great man himself. Fast forward to 2025, and I decided it was time to revisit Maranello. I wanted to look at the latest state-ofthe-art racing department, and view Enzo and Dino’s old office as displayed in the Museum Enzo Ferrari Modena.

Before this visit I’d had to submit a request as to what departments I wanted to visit and the questions I’d like to ask various heads. It was a far cry from the informal 1980s visit, when the marque had focused on racing and future production. We took the train to Modena and walked to the museum near the station, which consists of the original Ferrari family workshops and a modern glass eco-structure.

This visit was scheduled like a politician’s campaign trail, so we had to move through the exhibits sharpish, starting in the old workshop space packed with Ferrari engine history, and finishing with a ‘recreation’ of Enzo’s office – sadly showing none of the original’s size, layout or contents. We then entered a cathedral-like space dedicated, at the time of our visit, to the supercar, from the 250 GTO via just about every Ferrari contender to the current WEC Hypercar 499P.

An electric blue Ferrari Purosangue then whisked us to lunch at the famed Cavallino Restaurant. First, though, the security office placed a red sticker over my smartphone’s lens. To my recollection, every road and building had changed save for Via Abetone outside the old factory entrance. The Cavallino was once a workers’ coffee

THIS PAGE Enzo and Dino’s office was a time capsule; son and half-brother Piero stepped up to continue their work.

bar, but today – as part of Ferrari itself – it serves excellent regional food with great service. As I tucked into my tortellini, Piero Ferrari brushed past our table with a couple of colleagues on route to a private dining room.

After lunch, we walked to the Museum Ferrari Maranello for a tour heading to the Fiorano track, to visit the new Endurance and XX track-car building. I was given the all-clear to shoot the Le Mans car in the storage area, and also the rows of customers’ historic F1 cars. These were all ready for the lucky owners to participate in various track days – but when it came to the stroll through the workshops, unlike in ’87, my lens cap remained on. I was disappointed not to at least shoot an overview of the workshop, but our final destination more than made up for it. What is now Ferrari Classiche is housed in the original competitions department that I photographed back in the day. Head Andrea Modena gave us an interesting

department overview. The team understand that there are many fine restoration shops around the world, and indeed they have affiliations with 73 of them. What the factory possesses is the technical and sales data of every Ferrari ever produced.

We were given access to the archive, including the data sheets for the very first car and the 1951 sporting logbook with a report on the British GP won by José Froilán González in a Ferrari 375. Enzo might not have retained a collection of old cars, but he was fastidious about keeping records.

The workshop handles around 25 projects a year, with a waiting list of up to 55 cars – their owners all coveting that famous Red Book. The archive was mind-boggling in its size and organisation. We concluded the day with a good look around the workshop, photographing the examples of just about every decade of the marque. The space is now packed with classic Ferraris, where before a mere handful of F1 cars graced the premises.

When I departed Modena in 1987, I left a specialist auto manufacturer. In 2025, the factory builds 13,000 cars a year, and 700,000 people visit the museums. I was leaving ‘Ferrari land’.

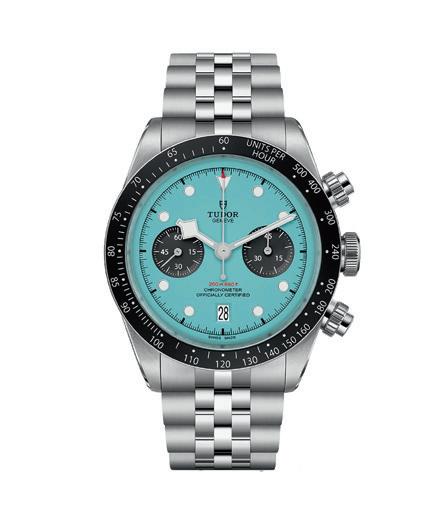

Swiss watch brand Tudor has given wings to its motor sport sponsorship. There’s history here

controversies and the term ‘DRS’ on constant repeat, there have not been as many eyes on this area of a Formula 1 car since aerofoils first appeared back in 1968. Fans will have noticed that Swiss watchmaker Tudor, a sponsor of the Visa Cash App Racing Bulls F1 Team (VCARB) since 2024, has dramatically increased its visibility in the sport with the prominent application of ‘TUDOR’ branding across the rear wing of the 2025 car. Tudor, much like sister brand Rolex, is no stranger to the motor sport arena. Avid followers of motor racing in the US will remember when the Rolex Sports Car Series merged with IMSA’s American Le Mans Series to create the very popular Tudor United SportsCar Championship of 2014-15. Before that, Tudor was the official timing partner of the 2010 Porsche Mobil 1 Supercup Championship, and a sponsor of Dutch racing driver Patrick Huisman.

However, Tudor’s official association with motor sport goes back to 1968, when Japanese Rolex and Tudor distributor Liebermann Waelchli’s sponsorship created the Tudor Watch Racing Team. The outfit’s weapon of choice was a Porsche 906, chassis no. 120, which it purchased from Shintaro Taki of Taki Racing. The Carrera 6 was given a new red livery with large ‘TUDOR’ lettering on the nose, rear haunches and tail-light panel. Rolex branding also featured, although not as overtly.

The Tudor car’s first race ended in a DNF for drivers Mitsumasa Takano and Jiro Yoneyama at the 1968 Fuji 1000km, but the same pairing finished second at the Suzuka 1000km event two months later.

After an opening win at the All Japan race at Suzuka in March 1969,

THIS PAGE Black Bay Ceramic ‘Blue’ marks Tudor’s alignment with motor sport from Porsche 906 in the late 1960s to Racing Bulls’ VCARB 02 in ’25.

and a third place at the All Japan Clubman Fuji race in April, the Tudorsponsored Porsche’s outing at the Suzuka 1000km race in June would be its most significant.

Starting from second place, the driver pairing of Tomohiko Tsutsumi and Yoneyama took the lead shortly into the race after Taki Racing’s polesitting Lola T70 ran into trouble. Falling back briefly, the Tudor car reclaimed the lead after three hours, and went on to take a well earned victory four hours later.

Pictures of the podium show the Tudor drivers with their laurel wreaths placed strategically over one shoulder only, so as not to cover the Tudor shield logo on their race suits. That’s some switched-on marketing for you. Naturally, Tudor watches were also part of the deal.

Although the 906’s competitiveness began to wane, Tudor’s commitment to the Japanese racing scene continued well into the 1970s, with Peter Bellamy driving it at races such as the 1972 Fuji Masters 250. Tetsu Ikuzawa then campaigned a Tudor-branded GRD S74 in the 1976 Grand Champion series, winning twice in the process. That particular car bore the slogan ‘Tudor Time Machines’ and had ‘TUDOR’ writ large across its giant rear wing.

Now, almost five decades on, Tudor again adorns the rear wing of a premier racing car. Sadly, though, big brother Red Bull’s poaching of VCARB’s rising star Yuki Tsunoda two races into the season has severed the watch brand’s admittedly tenuous but charmingly nostalgic link to the Japanese motor-racing community.

Coming full circle in a sense, today’s VCARB drivers sport Tudor’s Black Bay Ceramic ‘Blue’ watches. Fifty years on, the Tudor marketing machine still appears to be ticking along nicely.

22

140 Years of the Motor Car

The first production motorcar built by Karl Benz the in 1885

The Greatest Endurance Drive in History

7o Years since Stirling Moss won the 1000 Miglia

50 Years of the Porsche 911 Turbo

A showcase of the 7 generations of the Iconic Model

The Rolls Royce Phantom

100 Years since the successor to the Ghost was launched

The Aston Martin DB Era (1947-1972)

To celebrate 60 years since the DB6 was launched

Words Nathan Chadwick

With the passing of Eddie Jordan in March of this year, we look back at the colourful history of the giant-killing race team that bore his name for 25 years, including 14 in F1

1979-1982 THE START

Eddie competed in Irish Formula Ford, Formula 3, Formula Atlantic and Formula 2 from 1974-79, but a series of serious injuries and a lack of cash curtailed his driving ambitions. He founded his eponymous team at the end of 1979 to compete in British F3. He gave up driving duties in ’80, signing David Sears (Jack’s son) and David Leslie for ’81, the latter finishing fifth. New signing for ’82 James Weaver repeated the season finish.

Damon Hill joined the team and delivered a first win at the wild Belgian GP after a disappointing first half of the season with new Honda engines. Behind the scenes, Schumacher fumed at not being able to overtake the Brit – brother Michael bought out his contract for £2m.

1983-1990 PRE-FORMULA 1

Eddie ran Martin Brundle during an epic British F3 fight with Ayrton Senna in 1983, which the Brazilian won only in the very last round. The team eventually took the title with Johnny Herbert in 1987. Stepped up to F3000 and won the series with Jean Alesi in 1989 after an intense battle with Érik Comas. Future F1 drivers Damon Hill, Heinz-Harald Frentzen, Eddie Irvine, Paolo Barilla and Martin Donnelly ran with the team in F3000.

Progress continued with a new driver line-up of Ralf Schumacher and Giancarlo Fisichella for ’97. Plenty of podiums, and Fisichella came close to victory in Germany – but a holed radiator meant he had to get a lift home with Michael Schumacher. A team-mate collision at the Argentinian GP took a slight

1995-1996 SEASON FINISHES: 6TH, 5TH

Jordan became the Peugeot Works team and solidified its mid-pack credentials. A 1995 Barrichello and Irvine double podium was a highlight, although the podiums dried up in 1996 as the team adopted its signature yellow livery. A string of 4th-place finishes netted 5th.

Heinz-Harald Frentzen joined the team and took two victories and a pole to put the German in the position of an unlikely title charge. Hill endured a nightmare season and retired at the end of the year. Frentzen finished third in the drivers’ title as Ferrari and McLaren proved quicker and more consistent.

Jarno Trulli replaced Hill but results for him and Frentzen slipped away, including a double DNF from promising positions at the 2000 Monaco GP. 2001 saw Frentzen leave mid-season due to disagreements due to the courtship of engine supplier Honda, although Trulli bagged four points finishes. 2002 saw Takuma Sato and Fisichella in the team, but sponsorship declined and the team dropped down the grid.

Stepped up to F1 and, due to Bertrand Gachot’s legal issues, handed an F1 start to a promising young German driver, Michael Schumacher for the Belgian Grand Prix. The legal battle to retain his services when he then signed for Benetton, despite assurances from Mercedes that he was due to race for the team for the entire year, cost Jordan dear. Other highlight was Andrea de Cesaris’ epic but doomed battle with Senna in Belgium.

Despite finishing ahead of the other Honda team BAR, Jordan had to return to Ford Cosworth. The outfit slipped back to ninth in the standings, despite Fisichella winning the madness of the 2003 Brazilian GP. An attempt to sue Vodafone for £150 million of lost sponsorship ended badly, and the team would never recover.

Ford’s sale of Cosworth then left Jordan with no engines for 2005.

A switch to Yamaha and then Hart engines, plus a wide and varied driver line-up due to the fallout from the Schumacher battle, stymied progress for two years. 1994 was turbulent: rookie Rubens Barrichello bagged the team’s first podium, at the Pacific GP, but he was nearly killed qualifying at San Marino. He bounced back to score pole in Belgium, and the team entered the midpack with 5th place.

At the end of 2004 Eddie tearfully sold the team to Midland F1 for $60m, although the outfit would run as Jordan for a largely unsuccessful 2005. Engine was leased from Toyota. Tiago Monteiro bagged Jordan’s last point, with an eighth place in Belgium. The team morphed into MF1, Spyker, Force India, Racing

Italy’s FuoriConcorso is attracting more crowds, cars and manufacturer support year on year

JUST DOWN THE ROAD FROM Concorso d’Eleganza Villa d’Este is FuoriConcorso – still very much the new kid on the block compared with its neighbour, which started in 1929. For 2025, FuoriConcorso takes place on May 24-25, at the Villas del Grumello, Sucota and Olmo, located only a 35-minute stroll around Lake Como from Villa Erba and Villa d’Este. First held in 2019 it has attracted increasing manufacturer interest, from major brands such as Porsche and Aston Martin to smaller boutique firms like Koenigsegg and Zagato.

It all began in May ’19, when one of founder Guglielmo Miani’s other enterprises, the hand-made fashion brand Larusmiani, was sponsor to the Concorso d’Eleganza Villa d’Este.

“That year I had produced a book marking 100 years of Bentley and celebrating the Continentals of the 1990s,” he recalls. “I asked Villa d’Este and BMW if they minded if I rented a villa not far away to showcase 12 unique Continentals, all hand-made, and to present the book’s world

premiere. They said it was a great idea, and I expected 300, maybe 400 people – but 600 or 700 came along.

That gave me the enthusiasm to organise further events.”

This first of these was held during the 2019 Italian Grand Prix weekend.

“We brought six legendary F1 cars to a beautiful villa near Milan, and that was a success far beyond our expectations.

Then we started doing dynamic events,” Guglielmo explains. “We went to California and did our first FuoriConcorso rally from Palm Springs to LA. And then Covid arrived.”

He kept the concept afloat with a rally for only white cars in Sardinia, but FuoriConcorso remained the main focus. Subsequent themes have been aerodynamics (2023) and British Racing Green (2024), and 2025’s theme – Velocissimo (Italian racing legends) – will field some very special cars.

“I can promise a grid of Italian F1 machinery, as well as Le Mans and Targa Florio models,” Guglielmo says.

“There are 13-14 automotive brands involved, but even if they are not

THIS PAGE FuoriConcorso 2025 will build on the success of previous editions, with potential plans for a week-long experience.

‘I can promise a grid of Italian F1 cars, as well as Le Mans and Targa Florio models’

Italian they will interpret the theme.” Already confirmed for ’25 are Berger and Mansell F1 Ferraris, the Mauto Museum’s Maserati 250F and a Fangio Alfa Tipo 159. Non-F1 highlights include an ex-NART Ferrari Daytona and the 166MM Export ‘Uovo’, plus an OSCA MT4 Carrera Panamericana.

Alongside private collectors, brand heritage and classic teams also field rarely seen cars.

“Some manufacturers have approached us to be overall sponsors,” says Guglielmo. “But we say no – we want to build a community that involves all makers. When there is a special moment for a brand – such as Porsche’s 75th birthday in 2023 – we can give them a lot of visibility because that is a time for them to be in the spotlight. Maybe next year it could be Mercedes-Benz, because it has an anniversary, or Ferrari.”

Over the next few years Guglielmo is eyeing expansion: “Our goal – and I think we share this with BMW and Villa d’Este – is to lengthen the event to a week-long experience.”

See more at www.fuoriconcorso.org.

Rick Schad – better known as The Pope of Plastic – performs a miracle on a neglected GP winner

work of American Rick Schad – better known as The Pope of Plastic – who agreed to rescue my neglected RA272 from the twilight zone and transform it into a veritable work of art.

FOR MORE THAN FIVE YEARS, A 1:20 scale Tamiya kit of Richie Ginther’s 1965 Mexican Grand Prixwinning Honda RA272 Formula 1 car languished at the bottom of my wardrobe. As with many people I have fond childhood memories of building model cars, but my enthusiasm was always tempered by my lack of patience – and skill. So, rather than risk a disappointing result, I left the Honda kit in wardrobe purgatory, convincing myself that one day I would finally finish it.

That day never came. Yet, the little Honda Grand Prix car now sits completed, its elegant white bodywork weathered with faux oil and dirt, and its tyres marbled and worn. Even the exhaust pipes look as though they would be hot to the touch. The level of detail is staggering. Such incredible craftsmanship is the

Before The Pope anointed the model with glue, primer and paint, he did hours of research on Ginther’s car, referencing archive photographs to ensure fastidious levels of accuracy.

“I love doing research and using old images to create realism,” Rick says. “I certainly exaggerate the weathering –it’s not quite like this in real life – but this is art and it emphasises the car’s story. When you look at it, you should be able to almost smell the exhaust smoke and burning rubber.”

In total, it took him about 12 hours to complete the model – which is incredibly fast for the quality of finish and level of detail. “I build all the time, so it doesn’t take as long for me – for a regular person, it would probably take a week or so,” Rick reveals. That said, every build presents challenges, and the Honda GP car was no exception.

“Suspension is always tricky, no

matter how experienced you are –there are so many tiny parts,” he says. “You have to be really careful, because if you break the parts – which I have done many times – they’re difficult to fix. So that was challenging. I also lost one of the brakes for more than two hours,” he laughs.

For me, one of the most engaging aspects of the experience was watching Rick livestream the build on TikTok, allowing every artisan dab of glue and stroke of the paintbrush to be seen in real time. Ironically, following along only reinforced my decision to leave the kit untouched by my own hands – because the final result was far beyond anything I could achieve.

Maybe I will attempt another model, but for now I’ll simply enjoy this one – and continue watching The Pope work his magic on TikTok, where he’s inspiring a whole new generation of modellers. You can catch Rick live on TikTok on weeknights from 7:00pm ET and weekends from 11:00am ET.

To commission your own model, head to www.thepopeofplastic.com.

The London Concours is the capital’s leading automotive summer garden party, gathering together nearly 150 spectacular privately owned cars into one of London’s most beautiful hidden venues. Hosted at the Honourable Artillery Company HQ, a five-acre oasis of green in the heart of the City of London.

This year the London Concours will host – among many others – celebrations of Aston Martin, Mercedes-Benz and a dedicated Supercar Day to showcase the very latest performance innovations. Alongside these breathtaking displays, the London Concours is an occasion of pure indulgence, featuring luxury popup boutiques, champagne by Veuve Clicquot, catering by Searcys and a line-up of celebrity and expert guests as well as live podcast recordings

For tickets visit londonconcours.co.uk

TUESDAY 3 JUNE – A BRITISH ICON – ASTON MARTIN

WEDNESDAY 4 JUNE – THE GREATEST MARQUE – MERCEDES-BENZ

THURSDAY 5 JUNE – THE NEED FOR SPEED – SUPERCAR DAY

Boreham Motorworks’

Alan Mann Ford Escort Mk1 is one of the best Continuations we’ve driven

CONTINUATIONS DON’T GET better than this. It’s built by the original team, headed by the son of its creator, with several of the original engineers. It’s fully sanctioned by the original manufacturer. It’s also FIA approved for Historic racing.

This, then, is the Boreham Motorworks Alan Mann 68 Edition, a perfect copy of the 1968 British Saloon Car Championship-winning Ford Escort XOO 349F driven in ’68 and ’69 by Australian Frank Gardner.

In the Escort road car’s launch year, Alan Mann Racing built XOO to exploit every limit of the Group 5 regulations of the day, to the point that it ran a double-overhead-camshaft Formula 2 FVA engine, and suspension that used GT40 components at the front and torsion bars at the rear. Even the bubble arches, much-copied ever since, were an XOO first.

The recreation differs only in having modern cage, seats, harnesses and fire-extinguisher system (although an even more period-correct version can be ordered without the safety gear), along with Koni instead of Armstrong dampers. Otherwise, it’s just as the late Frank Gardner would have experienced XOO – which, as it turns out, is as raw, visceral and responsive a car as you’ll ever drive.

On the challenging, twisty private track of M-Sport, rally legend Malcolm Wilson’s all-conquering motor sportpreparation team, the new Alan Mann 68 Edition is a revelation. Strapped in tight by the five-point harness, you’re faced with an early race version of the classic six-dial dash and trademark deep-dish steering wheel. On correct Elektron magnesium-style aluminiumalloy 13 x 8in front rims (the rears are 13 x 9in), the steering is initially heavy and the twin-cam engine vibrates the bare shell, but the clutch is easy and

there’s enough torque to set us into motion without drama. That’s a relief in itself, for Alan Mann’s son Henry, who now runs the team, is watching.

Down to the first corner and the unservo’ed brakes – solid discs all round – need a hefty shove, but the car turns in exactly as expected and the engine picks up instantly, sounding glorious as the revs rise.

The four-speed ‘Bullet’ ’box can’t be rushed and needs a heel-and-toe throttle blip for the perfect shift, but it’s so direct that it feels like the selectors are in the palm of your hand.

As the laps go by, it becomes clear that the more you put into this car, the more it will give, whatever your skill levels. On a damp track this is a truly

THIS PAGE David Lillywhite in one of his childhood poster cars – or at least a recreation of it. Only 24 will be made, in period or FIA specifications.

unheroic drive, but instructor Karl Jones has already shown what the Escort can do, flicking from initial understeer to perfectly throttlecontrolled oversteer. It feels so good.

There will never be the chance to drive the original, XOO, in anger, but the Alan Mann 68 Edition could be as satisfying for an experienced racer as for a complete novice. Indeed, as part of the package Boreham Motorworks will invite buyers to events and offer training and racing fully supported by an Alan Mann Racing pit crew.

Boreham Motorworks and, since late 2024, Alan Mann Racing, are part of DRVN Automotive Group, which has engineering and production facilities around the UK. Its in-house teams have scanned and digitally modelled every component of XOO, while all new panels and parts are being manufactured using state-ofthe-art tooling and hand-built on new modern jigs for precision.

Next up is a road-spec restomod version of XOO, which will be followed by a ‘reimagined’ RS200 and further Alan Mann models – all officially approved by Ford, which shows the respect for DRVN in the industry.

For more on the Alan Mann 68 Edition, visit the Magneto website and see www.borehammotorworks.com.

AN ALL-NEW CONCOURS EVENT

is set to take place in Bahrain on November 7-8, 2025. The event has the full support of His Royal Highness

Prince Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa, Crown Prince and Prime Minister of Bahrain – who is best known for his part in the creation of Formula 1’s Bahrain International Circuit.

The Royal Bahrain Concours comes from Thorough Events, the team behind the successful Concours of Elegance Hampton Court, London Concours and Concours of Elegance Germany. It will take place at the Royal Golf Club, with exclusive activities for participants such as private track days and cultural excursions to Bahrain’s souks and historic sites, as well as a unique

November’s exclusive Royal Bahrain Concours to be staged by British team behind Concours of Elegance Hampton Court

Cars by Candlelight evening event.

The concours will feature 60 handselected, world-class collector cars. Forty of these will come from across the region and the rest from around the world, encompassing historic examples, coachbuilts and modern hypercars. This machinery will be supplemented by a display of 200 cars from local auto clubs.

“This is a Gulf concours, not a British concours in the Gulf,” Thorough Events CEO James BrooksWard said. “The date was chosen by His Royal Highness and the Bahrain Tourism and Exhibitions Authority. The people of Bahrain are very warm, friendly and welcoming, and we’ll be encouraging owners and their families to take part in all the events. We

are immensely privileged to have HRH Prince Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa as the Patron.”

Bahrain has become a tourist destination for the Gulf as well as a winter destination for Europeans and Americans. The temperature in November is usually around 25ºC to 30ºC, making it more comfortable for those flying in from outside the region.

Several major collectors from the Gulf, US, Europe and the UK have already committed to showing their cars. Concours classes will include Cars of State, The Cars of the Maharajas, The Cars of Falconry, 75 Years of Formula 1, American Classics, Modern Coachbuilding and Achievements in F1: McLaren’s Story. More details at www.royalconcours.com.

The 2025 Blenheim Palace automotive garden party will mark its anniversary with a series of innovations and new, special treatment for car owners and VIPs

THIS SPREAD Salon Privé founders Andrew and David Bagley have planned plenty of treats and surprises for this, the event’s 20th anniversary.

IT’S NOT JUST THE QUALITY of the concours, the garden-party atmosphere or the locations that define 20 years of Salon Privé. It’s also the continual innovation from founders David and Andrew Bagley and their team throughout the decades.

Think of how the event has changed, from its early beginnings at The Hurlingham Club in Fulham, West London, to Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire. It’s at the latter where it’s become a happy fixture in the calendar – indeed 2025 sees the tenth anniversary of Salon Privé at Blenheim.

To mark these two big occasions, the team has introduced several more innovations for Salon Privé week (Wednesday August 27 to Sunday August 31), as the Bagley brothers recently told Magneto:

“The key change this year is the new structure – this beautiful glass gallery that blends itself aesthetically with the palace and the surroundings to create a central covered area for all of the automotive brands and sponsors as well as the hospitality areas,” explained David.

“It brings all of the brands together

under one roof. It puts them all back on a level field, so the cars are the focus. It principally provides weather-proofing and sustainability, as well as a new direction for the event on its 20th anniversary.”

There’s also a new experience for concours car owners and VIPs, which marks a first for the Blenheim Palace estate since the venue was opened to the public 75 years ago.

“Owners and VIP guests of sponsors and automotive brands will now have a private gate, the Ditchley Gate entrance, further out on the estate,” explained Andrew. “They have their own private entrance to drive in and experience the estate all the way through, as they come up to and drive over the bridge and then park in the VIP paddock in front of the Great Court.

“And they’ll then come into the Great Hall and have their own mini history tour, because they’ll be taken right through some of the state rooms to the Long Library, and then come back along the rear side of the palace rooms and into the Saloon before they drop out onto the steps and into Salon

Privé. They’re going to have the most incredible and unique experience on arrival, before they even get onto the lawn and the event itself.”

Not only will this be the first time that Salon Privé owners and VIPs have been allowed this unique experience, it’s also the first time that Blenheim Palace has opened in this way to any public visitors.

To add to this, once again for the first time, the grounds of Blenheim Palace won’t open to the public until 11:00am instead of the usual 10:00am, meaning that owners and VIPs will have the place to themselves at the start of each of the three VIP days –Wednesday and Thursday’s Concours Days and Friday’s Ladies’ Day.

The 20th anniversary celebrations will add extra sparkle elsewhere, too, with the annual Gala Dinner this

year extended from the Great Hall to include the Saloon and the Long Library. This will allow capacity to expand from the accustomed 240 visitors to around 600.

Similarly, there will be anniversary celebrations at Salon Privé’s newest addition, the stunning MotorAvia evening party down the road at London Oxford Airport, which this year takes place on the Wednesday night.

The concours aspect, too, will be ramped up for 2025, with the toplevel ICJAG judging continuing to attract the very best cars from around the world. Indeed, every aspect of Salon Privé week has been given a touch of 20th anniversary magic, including the popular Supercar and Club days over the weekend.

For more information and for tickets, see www.salonpriveconcours.com

Team facilities

Power

Weight

1. NO

doubt you will have noticed all the 75th anniversary marketing fanfare and accompanying celebratory events. Of course, informed fans know that Formula 1 as a set of continuously evolving regulations governing top-tier post-war motor racing has been around for longer.

The first official F1 race was the 1946 Turin Grand Prix – a successful trial run for F1’s full introduction in 1947. For two further seasons, entrants campaigned for prize money and bragging rights but no real recognition. The institution of the FIA World Championship of Drivers in 1950 fixed this glaring lack of prestigious silverware, with Giuseppe ‘Nino’ Farina being crowned the first F1 World Champion. It’s this Championship we’re all celebrating.

From the downright obsessed to those who claim to only take a passing interest, almost all who follow Formula 1 will remember the moment the sport first got its hooks into them. Moss at Aintree in ’55; Jack Brabham pushing his Cooper to the drivers’ title at Sebring in ’59; Lauda’s gutwrenching, fiery, near-fatal Nürburgring crash, or his miraculous fourth-place finish at Monza just 42 days later; Gilles Villeneuve drifting his Ferrari in Argentina (and everywhere else); Senna in the wet at Donington Park; Räikkönen blindly refusing to lift through thick smoke while qualifying for the 2000 Belgian GP at Spa; Hamilton at Silverstone, for any one of his record nine British GP wins; the list could go on and on… Heroic, dramatic, dangerous and, yes, predictable too on occasion, the Formula 1 World Championship has delivered 75 years’ worth of unforgettable speed, courage and controversy,

while providing a premier showcase for outrageous driving skill, crafty team management and ingenious automotive engineering – the last of these being crucial to on-track success. After all, even the very best drivers can do nothing without a reliably quick car beneath them. From 1958, team owners and managers, technical directors, designers, engineers and mechanics got to battle it out for their own bit of silverware (and in recent decades, a healthy share of television-broadcast revenues) in the form of the International Cup for Formula 1 Constructors, known these days as the F1 World Constructors’ Championship – just one of the innumerable changes to a sport in constant evolution.

A lot can happen in 75 years. Picking just a few highlights from F1’s powerplant chronicles underscores the flux. From supercharged 1.5-litre and naturally aspirated 4.5 origins via the 1500bhp qualifying-spec turbocharged V6 grenades of the 1980s and near-20,000rpm turnof-the-century V10s, to the current 1000bhpplus hybrid era, F1 engines have driven innovation, specific power outputs and efficiency to stratospheric heights. Advancements in car construction, aerodynamics and suspension design have transformed these machines from unwieldy beasts to rockets on rails. Trackside clips of the cars blitzing Singapore’s Marina Bay circuit at night may as well be footage from the next Tron film.

Along with the phenomenal dynamic progress has come an absolute revolution in safety. In the early days, drivers in cotton overalls, cloth skull caps and goggles would hope to be thrown clear of the wreckage. Today’s flame-retardant Nomex-suited drivers wear full-face carbonfibre helmets, HANS devices and biometric-enabled gloves, and are strapped into halo-equipped, virtually impenetrable carbonfibre survival cells.

The result is that driver fatalities in the sport have gone from something morbidly routine to a freak occurrence. A measure of the step-up in safety is that four drivers – de Angelis,

Ratzenberger, Senna and Bianchi – have lost their lives testing and racing in Formula 1 in the past four decades, while four F1 drivers died in 1958 alone. In both cases it’s four too many, however, and no real comfort at all.

While the sport’s rapid evolution makes direct comparisons impossible, at the 1950 British Grand Prix at Silverstone the average age of the 21 starters was 39. Three of those were over 50 years old. At the 2024 season-ending race in Abu Dhabi, the average driver age was 29, with 13 of the 20-strong grid still in their 20s. In 1950 Alfa Romeo brought 12 personnel to the track. Three of them performed a fuel-andtyres pitstop in what was then a remarkable 22 seconds. In 2024, 20 of McLaren’s 50 team members – the maximum permitted on race day – changed the MCL38’s four tyres in 1.9 seconds. The prize money for the winner of the 1950 British GP was £500, while 2024 Constructors’ Champion McLaren won an estimated $161 million for its season’s efforts.

The differences are stark, with the role played by many of the sport’s most influential figures –Bernie Ecclestone, Max Mosley and several other FIA presidents, Professor Sid Watkins and Jackie Stewart, not to mention all the commercial partners, team sponsors and advertisers – being pivotal in transforming a little-known, extremely dangerous motor-racing discipline into the third most watched sporting event on the planet. The challenge for current overlord Liberty Media is to sustainably balance entertainment with authenticity. As long as that ratio stays within enthusiasts’ reasonably broad tolerance margin, we’ll keep on championing the sport. Long live F1!

RISING FROM THE ASHES OF GLOBAL CONFLICT WITH MORE SPEED AND PURPOSE THAN ITS RIVALS, ALFA ROMEO TURNED ITS ‘ALFETTA’ INTO A KINGMAKER, A RACE CAR WORTHY OF DELIVERING THE FIRST FORMULA 1 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP CROWN

YEARS OF F1

AS MUSEO ALFA ROMEO CURATOR Lorenzo Ardizio wheels the ruby red Tipo 158 from its darkened exhibition hall into a floodlit tunnel beneath the building, thoughts of Alfa personnel extracting 158s from the darkness of wartime hidey-holes back in 1946 spring to mind. They could not have known the full extent of the glory that awaited the dusty metal panels they handled that day, but as I run my palm across the polished bodywork almost eight decades later, the historical significance of this motor sport jewel could not feel more tangible. Ironically, the 158 was initially developed to race in the second-tier Voiturette class, in response to the Italian carmaker’s inability to compete effectively against the might of the German marques in the 750kg Grand Prix era. However, with the governing AIACR – the precursor of the FIA – announcing new regulations for 1938, Alfa wasn’t about to give up on GP racing altogether. No longer driven by a

maximum weight, the new rules placed limits on engine capacity instead, allowing teams to run either normally aspirated 4.5-litre or supercharged 3.0 units. With expediency in mind, Alfa Romeo entered the Tipo 308 – a rebodied, modified Tipo C powered by a slightly bored-out version of the 8C 2900’s straight-eight – as its 3.0-litre contender. The 308s, though, along with the 312 and 316 race cars that followed, were not a great success. Instead, it was hoped that Alfa’s Tipo 158, designed by Gioacchino Colombo and partially built by Scuderia Ferrari in Modena, would deliver the motor sport glory that Italy’s leaders so greatly desired. The all-new model was powered by a 1.5-litre straight-eight that featured a light magnesium-alloy block, a nickelchromium steel crankshaft, screw-in steel bores, Vittorio Jano’s gear-driven dual overhead camshafts, a triple-body carburettor and a Roots single-stage supercharger. In its earliest guise, it produced 185bhp (195bhp on its race debut). Mounted up front, the engine drove the back wheels via a transaxle arrangement. The 158 featured Ferdinand Porsche-type independent swing-axle rear suspension and independent trailing-arm front suspension, with transverse leaf springs fitted all round.

With the fortuitous news that the 1.5-litre supercharged Voiturette class was to become the leading Grand Prix class in 1940, Alfa Romeo’s Wifredo Ricart-run Servizio Studi Speciali began work on the Tipo 512, a far more radical and innovative 1.5-litre design as a possible replacement for the 158. It would not be required. Inspired by the mid-engined Auto Unions, Ricart opted for a similar layout for the 512, his second Alfa Romeo after the unsuccessful V16engined Tipo 162. The experimental flat-12, called ‘quadro’ in Italy due to its virtually identical bore and stroke measurements, is said to have produced 335bhp thanks to two twin-stage superchargers. Given more development time, that figure would likely have exceeded 500bhp. Its advanced suspension comprised double wishbones up front and a de Dion rear axle. However, serious handling issues put a damper on progress.

These two quite diverse projects reflected the split organisational set-up at the time. Enzo Ferrari’s Scuderia Ferrari was contracted to run Alfa’s racing programme, and Servizio Studi Speciali was tasked with special projects, the latter being the genesis of the company’s engineering department. Both were able to develop a car from scratch – an unnecessary duplication that likely played a role in Alfa’s decision to bring the entire operation in-house under the newly founded Alfa Corse racing department in Portello, Milan. Unhappy with the changes, Enzo soon parted ways with Alfa Romeo. By incorporating the Scuderia, Alfa Corse inherited a team of people with exceptional motor sport experience. They knew how to design a car, how to set it up – and how to race it. This was evident from the start because the

BELOW Nino Farina (on the right), second on the starting grid for the 1950 French Grand Prix at Reims-Gueux.

158, driven by Emilio Villoresi, won the Voiturette class on its debut in Livorno, Italy at the Coppa Ciano Junior in August 1938. People took notice, especially the press, with the influential Auto Italiana bestowing on the 158 a nickname that stuck: Alfetta (Little Alfa). Villoresi won again that year, at September’s Milan Grand Prix. Continuous development throughout 1939 involved bodywork revisions at the front, substantial improvements to the car’s airflow and cooling, an evolution of the chassis and an increase in engine power output. Class wins at the Coppa Ciano, the Coppa Acerbo and the Swiss Grand Prix in Bremgarten were just rewards for the constant work. The only race the 158 lost that year was the Tripoli Grand Prix in Libya, which Hermann Lang won at a canter in a Mercedes-Benz W 165, with a sister car finishing second. These very special 1.5-litre supercharged eight-cylinder Silver Arrows had been purposefully designed for the Voiturette-only 1939 Tripoli race and would never compete again. Stuttgart clearly did not have a resource problem.

By then the Alfetta’s engine was producing more than 225bhp, thanks in part to a revised lubrication system and crankshaft, but predominantly to work done on the fuel. Specific compositions of methanol, acetone, benzine, castor oil and other ‘secret ingredients’ allowed higher compression from larger supercharger rotors, resulting in an increase in power. Alfa was one of only a few companies with its own chemical-research laboratory, which it used to develop, in close cooperation with Agip, fuels and lubricants, as well as metal alloys for aviation and automotive applications. Everything was pointing to 1940 and the proposed new 1.5-litre GP regulations. Sadly, after a final Alfa 1-2-3 at the 1940 Tripoli GP, the escalation of World War Two prevented their implementation and ultimately brought the curtain down on motor racing in Europe.

As daily operations became increasingly difficult in the early 1940s, Alfa moved various development departments away from the city of Milan and its associated threat of bombings and war requisitions. The Alfettas were reportedly stored at Monza, before being hidden on nearby farms and behind a false wall in a factory in Melzo, not far from Milan. Ardizio tells me that a couple of race cars and Alfetta engines were hidden in the Villa Castoldi in Abbiategrasso. Achille Castoldi had been using marine-modified 158 engines in motorboat competitions since 1938. A letter in the archive thanks him for his help in hiding company assets during the war. Castoldi again received engine support after the war, setting a record in the 450kg hydroplane class with his Alfetta-engined Arno II, in what was a successful side hustle for the GP engines. Development work on the Alfettas commenced almost immediately post-war, with the focus again on increasing power. The introduction of a