FOREWORD

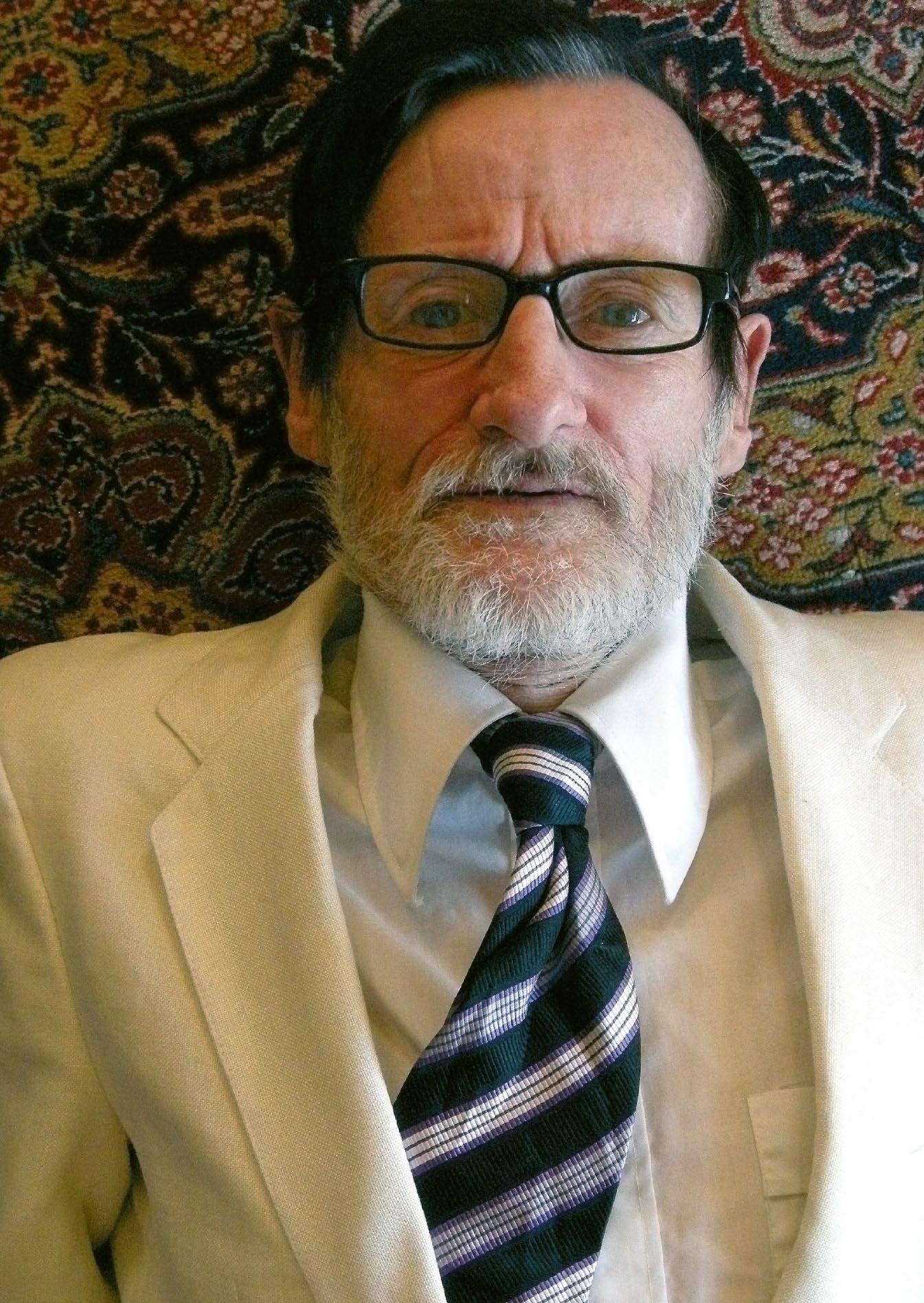

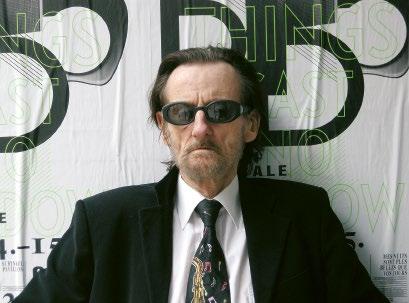

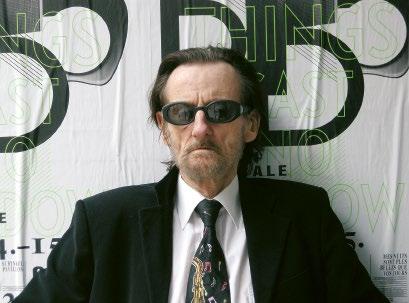

The need for reliable material about the life and works of the artist Hariton Pushwagner is acute, both here in Norway and further abroad. That is the reason for this slim volume, which will in fact be the very first printed publication about the phenomenon Pushwagner. Let us call it an introduction, or an essay of appreciation.

This text is based on a talk I gave at the Norwegian Literature Festival in Lillehammer in spring 2008. Apparently, it was the first such lecture ever given about Pushwagner.

In other words, prior to 2008, Hariton Pushwagner has more or less represented terra incognita. By any account, this is the case if you are seeking reliable, coherent information about his life.

My starting point for gaining an understanding of Pushwagner is the author Axel Jensen, whom I collaborated closely with during the final years of his life. One of the outcomes of this collaboration was a portrait interview,1 several radio programmes on P2 on NRK, the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation,2 and the book Axel Jensen: Life Seen from Nimbus, 3 which is very much of an autobiography.

Neither Axel Jensen nor his brother in spirit Pushwagner allowed themselves to be brought down by the weight of adversity that struck them. Despite suffering from ALS, a sneaking, and finally fatal, illness which paralysed him, Axel Jensen worked right up to the end of his life, even though he could only communicate by using his eyes during that last year.4 Pushwagner´s resurrection in the last years deserve the same acknowledgement.

The first time I met Pushwagner was, I recall, at the memorial service for Axel Jensen in his home at Ålefjær outside Kristiansand in the South of Norway. Pushwagner revealed his admiration for the book Livet sett fra Nimbus He identified very strongly with Axel’s life story and thought that in many ways it represented his own. Now that I have got to know him well in the course of our enumerable conversations, I understand

1 “Tvil er viktigere enn tro”, (Doubt is more important than belief) Humanist 2/1995.

2 Eight half-hour programmes were broadcasted during summer 1995 with the title “As long as I can sound off”.

3 Petter Mejlænder, Spartacus Publishing House, 2002.

4 Axel Jensen died in his home on 13 February, 2003.

4

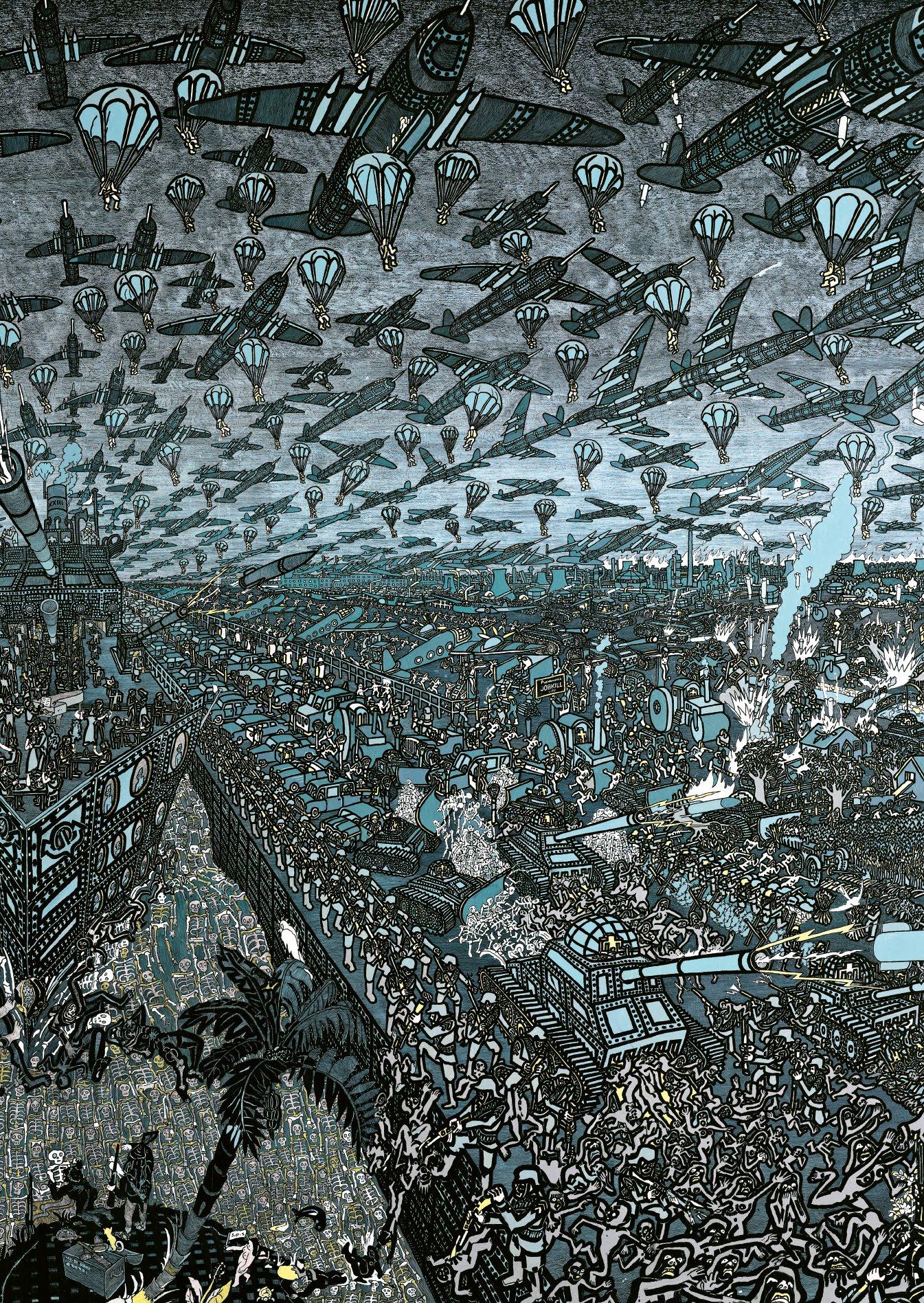

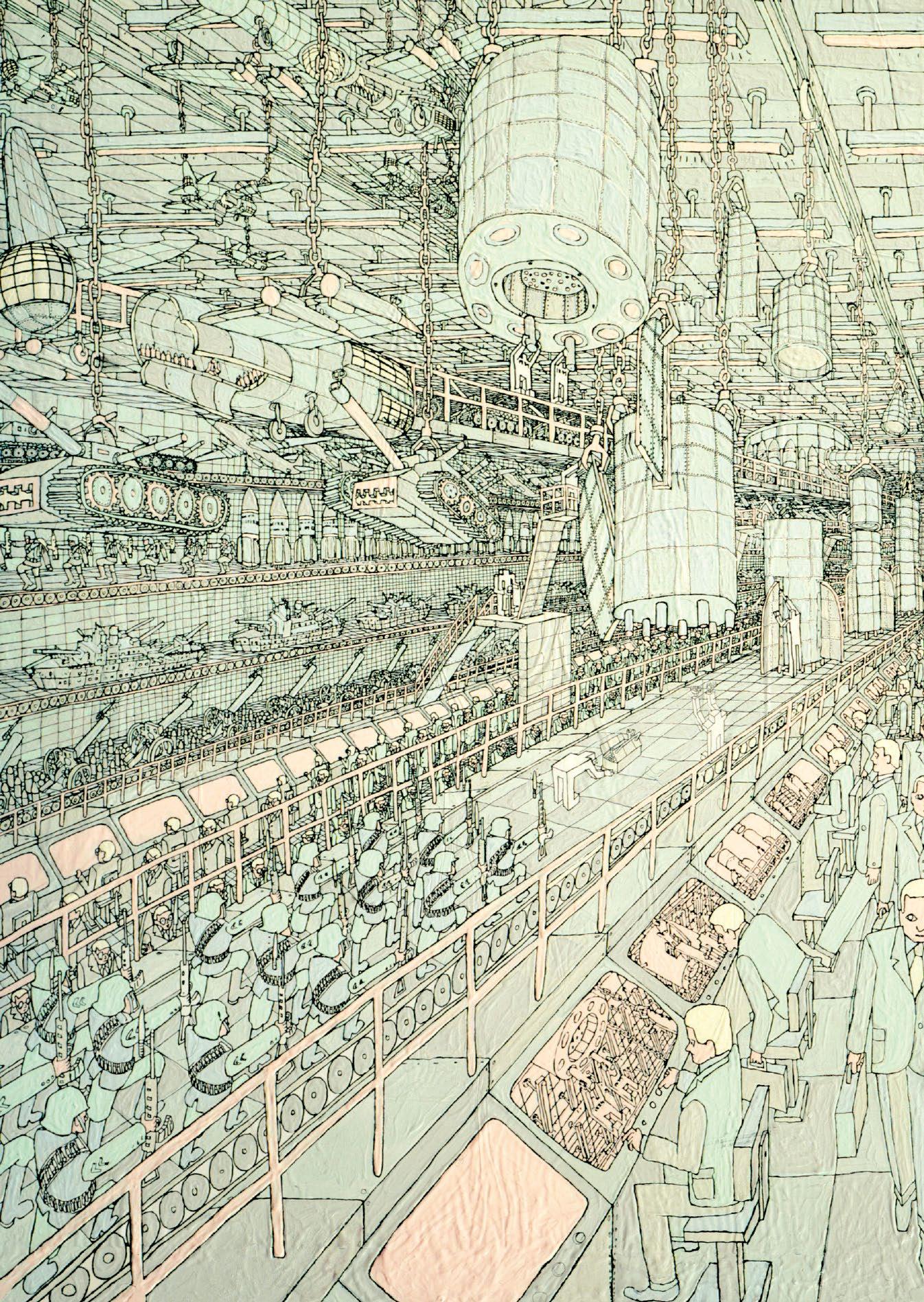

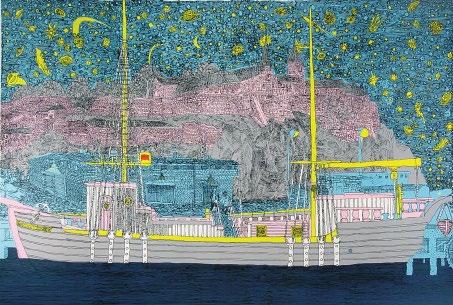

P. 3: ARTWORK, “SOFT CITY”

what he means since Pushwagner’s artistic renown owes a great deal to Axel Jensen. Nor should it be overlooked that Axel Jensen stood in debt to Pushwagner as well. If we were to sum up their months together under the same roof (and below the same deck5) we reach a period of roughly five years. That alone should reveal how close they were to each other, not just as friends and colleagues but as kindred spirits.

Consequently, when Pushwagner requested, barely a year ago, that I should write about his strenuous life, it was easy to agree. I knew by then that Pushwagner had much more on record than his fellowship with Axel Jensen. Pushwagner has illustrated several of Axel’s books, but his paintings have been purchased by several collectors and art institutions, notably the National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design in Oslo,6 and it is almost a generation since he exhibited his work at the Henie Onstad Art Centre at Høvikodden outside Oslo.7 In recent years his work has been represented eleven times in the annual National Autumn Exhibition in Oslo and three times in the annual exhibitions ‘Norwegian Pictures’ in Oslo City Hall. He also won prizes for his unique form of expression in the Baltic8 and New York9. The knowledge that, up to a few years ago, he was setting a steady course towards the silence of the grave certainly does nothing to lessen our interest in Pushwagner as an artistic phenomenon.

Currently here in Norway, the 68-year-old artist, satirist and social critic has virtually achieved cult status.10 Simultaneously, his works have aroused acclaim the world over (at the time of writing he has just arrived at the Sydney Biennale11 after opening an exhibition in Paris12). It is no exaggeration to say that Pushwagner no longer needs to

5 Pushwagner lived for almost four years on Axel and Pratibha Jensen’s schooner at Waxholm, outside Stockholm

6 The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design purchased Jobkill in 2006.

7 A Day in the Life of Family Man, Henie Onstad Art Centre, summer 1980.

8 The XIIth Vilnius Painting Triennial, 2004. He was awarded first prize for his painting Manhattan

9 Gallery 54, 1988; Art Horizons – Leading International Art Competition. He won first prize for his painting Gigaton

10 “The brightest star on the Norwegian art scene right now…” Dagbladet, 27 May, 2008.

11 The 16th Biennale of Sydney; Revolutions – Forms that Turn, summer 2008. Pushwagner participated with among other pieces: Soft City and Self-portrait

12 Kadist Art Foundation, Paris; Like an Attali Report, but Different, summer 2008. Pushwagner exhibited the painting Klaxton and drawings from the late sixties, which were recently found amongst documents left by Axel Jensen.

5

PUSHWAGNER AND AXEL JENSEN

SHANTI DEVI

dance in order to keep warm (as he did for several years in the late nineties because he had nowhere to live); now he can dance for pure joy. Today Pushwagner stands firmly planted in the centre of Norwegian art, although the public have only seen a fraction of his close on a hundred thousand drawings, prints, friezes and paintings.

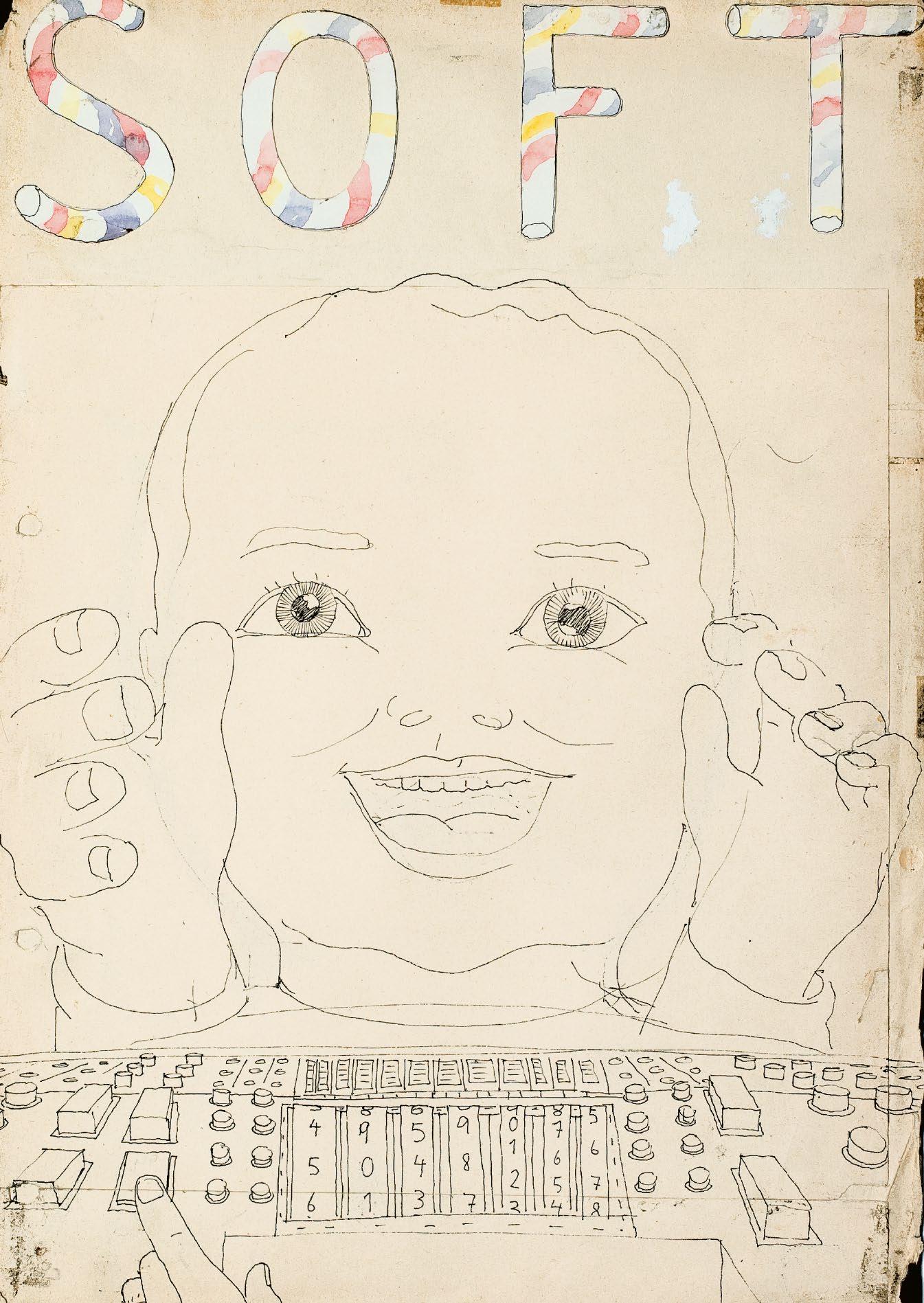

When he published the thirty-year-old graphic novel Soft City in early summer 2008,13 the queue for his signature was over 200 metres long. An amazing number of those waiting were young people who could have been his grandchildren. Bearing in mind that it is less than ten years since he was homeless, keeping alive by using illegal drugs, when people wished to avoid him, then we can fully understand why the artist did pirouettes in pure joy between signing books. Experiencing success like this is overwhelming.14

Events like this should give us all hope, for Pushwagner’s fate shows that quality, originality and perseverance can overcome most obstacles – as long as one never ceases to “push”. Weakness and strength are neither stable phenomena nor clear entities. We all of us push and get pushed. Pushwagner knows that. He also knows that success is not something that can be planned. Success, if it comes, comes in its own time. And it has its costs.

I wish to thank Terje Brofos and Hariton Pushwagner for all the trust and friendship shown to me while working on this book. Everything written here about Pushwagner is a result of collaboration – and debate. No-one can be in Pushwagner’s proximity without feeling the man’s critical stance and provocative sharpness: his “push”.

Ultimately this book conveys my understanding of Pushwagner expressed in my own words. Pushwagner’s style of expression is inimitable.

Petter Mejlænder

13 No Comprendo Press, 2008.

14 Soft City received excellent reviews. The newspaper Fædrelandsvennen wrote “A masterpiece”, 23 June 2008. The newspaper Verdens Gang (VG) also gave it top rating and wrote “Original and disturbing” 25 July 2008.

6

BOOK LAUNCH, SOFT CITY

BOOK LAUNCH, SOFT CITY

SOFT CITY

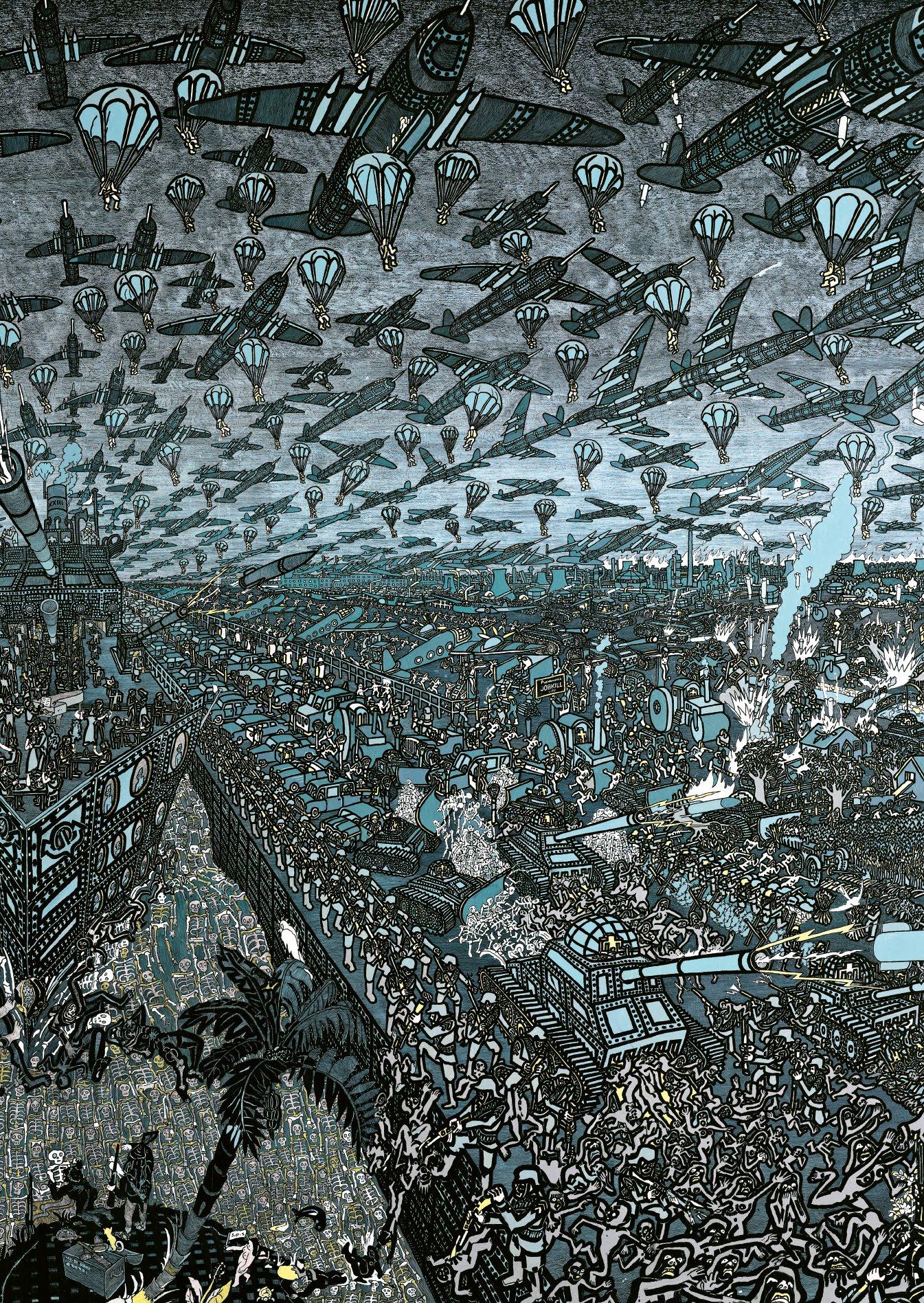

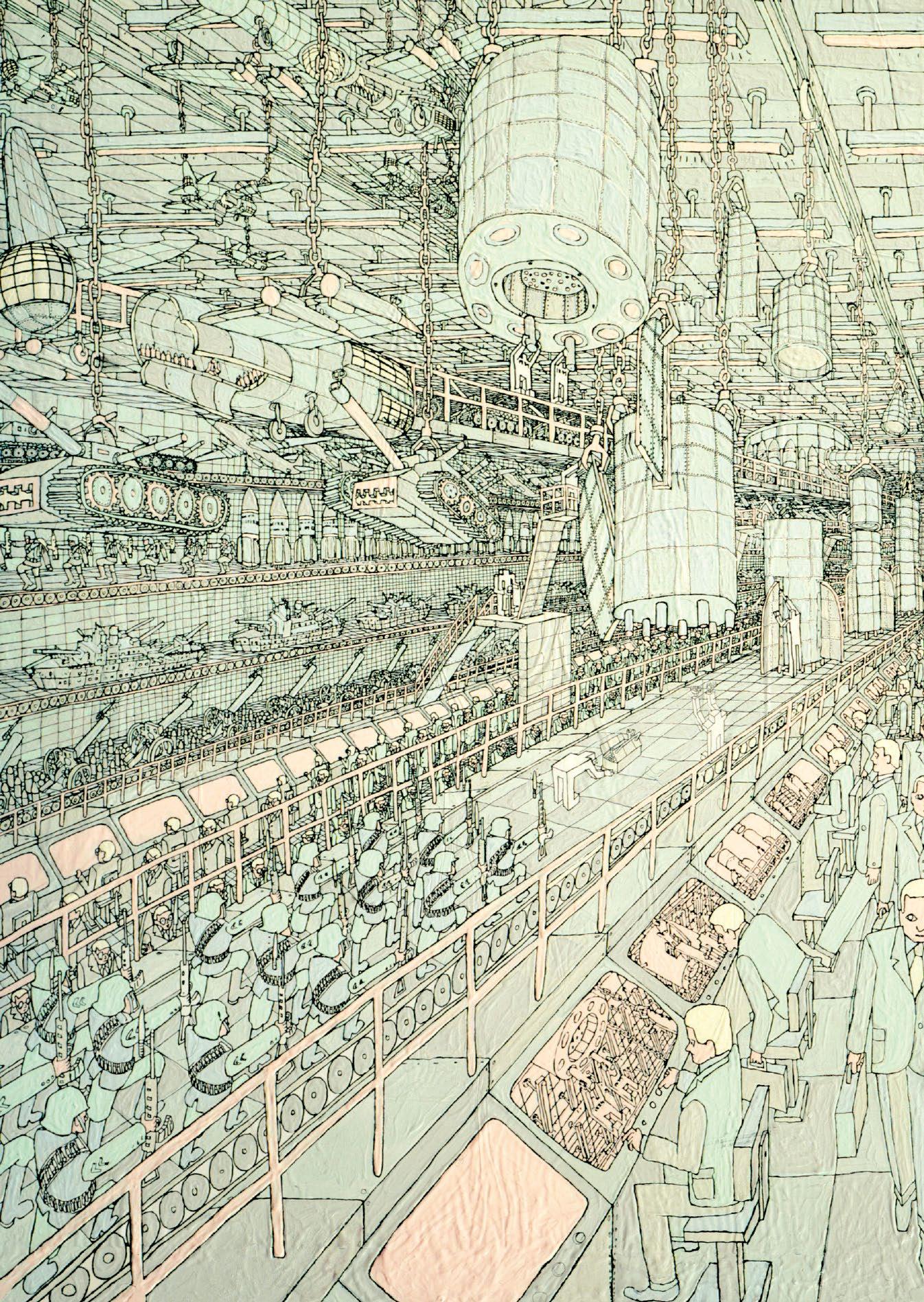

P. 7–8: “GIGATON”

The artist Hariton Pushwagner has, to his own and many other people’s amazement, become a name on everyone’s lips. Everybody knows of him, but his biography and the history of his artworks are only to be found in a fragmented form. A sense of unity, connection and understanding gets lost in the unknown. What is said and written about him readily assumes the stamp of myth and madness – or even of genius.15 No-one can ascertain whether what they have read or heard is rumour or pure speculation.

In the media, Pushwagner has been presented many times from a biographical angle, but there has often been something transient and agitated about these sketches or impressions created in connection with some specific occasion. The interviewers have tended to adopt a stance that is common in new journalism – foregrounding their own experience and admiration.16

This method is used for the simple reason that Pushwagner as an individual often behaves in a way that others find confusing and intangible. Moreover, he tends to have a somewhat abrupt, disjointed and circular way of communicating with people, frequently using his whole body as a means of expressing his, at times, rather elaborate explanations. In addition, he can break off in the middle of some explanation, or suddenly seek refuge in an intense loss of words or an astonished questioning look, or the opposite; for example, an intense scrutinizing look that can nail you to the spot and make you feel uncertain. Consequently, much of what has been written about him is unreliable, apart from providing an anecdotal, fleeting description of some incident.

Unfortunately, there is no authorised or systematic overview of his life and works, nor has he himself written down anything that can help us out, if, that is, we do not take his paintings into account. That is, however, exactly what we must do since that is where we find his self-presentation – one which is being carried on continually and with frenetic intensity. The fact that many of his works have been inaccessible, or have disappeared without a trace for long periods of time, has not been conducive to bringing

15 “One hell of a genius” wrote Audun Vinger, in the newspaper Natt og Dag in 2004.

16 Vinduet, Vol 1, 2008, where the interviewer Terje Thorsen describes himself as “an over-enthusiastic child celebrating ten Christmas Eves simultaneously” just because he is allowed to be close to the artist.

9

1

him into the limelight. Soft City, for instance, cropped up in a small leather suitcase in an attic at Nesodden on the outskirts of Oslo after 20 years’ mysterious disappearance. Pushwagner had left the whole pile of drawings behind in the hold of Axel and Pratibha Jensen’s schooner Zeus in Stockholm in the early eighties.17

In the Oslo region, Pushwagner has been notorious these past ten-twelve years as a wayward eccentric, vodka-drinking vagrant, a weird nonconformist, who, for hours on end, could act feverishly, appearing to be obsessively agitated, on the dance floors of Oslo’s trendiest nightclubs.18 In several bars, cafés, restaurants and clubs in the capital, he has made his mark using paintbrushes, felt-top marker pens and etching. He is probably the artist who has decorated most restaurants and clubs frequented by young people in Oslo.19

Recently, in total contrast, a great deal has changed in the life of Pushwagner, who up till only a few years ago was lying emotionally wounded in the gutter, his veins full of drugs. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say that his life has now set him back on his feet. Like the Phoenix he has risen out of the ashes of absolute chaos and awakened to a new life. Thanks to the assistance of curators and gallery owners at home and all over the world, Pushwagner is winging his way on a flight of conquest in Europe, USA and Australia. He has been discovered, as they say, and called one of the overlooked treasures within the satirical, social realist world of pop art. At the same time the newly acclaimed 68-year-old has decided to do battle against Morten Dreyer, his old companion in the eighties and nineties. The initial onslaught ensued across ten pages of the leading financial newspaper Dagens Næringsliv in spring 2008.20 In summer 2008, Dreyer was charged for having forged and sold Pushwagner prints.

In Pushwagner’s opinion, Dreyer had acquired several thousand of his most important paintings, friezes, drawings and etchings in a dishonest way. Dagens Næringsliv

17 The 80-foot long schooner from 1905 was later renamed Shanti Devi

18 Headline in Natt og Dag in 2004: “Look, grandfather’s dancing”.

19 The latest of these is Kafé Celsius at Christiania Torv in Rådhusgata in Oslo.

20

10

NATT OG DAG, 2004

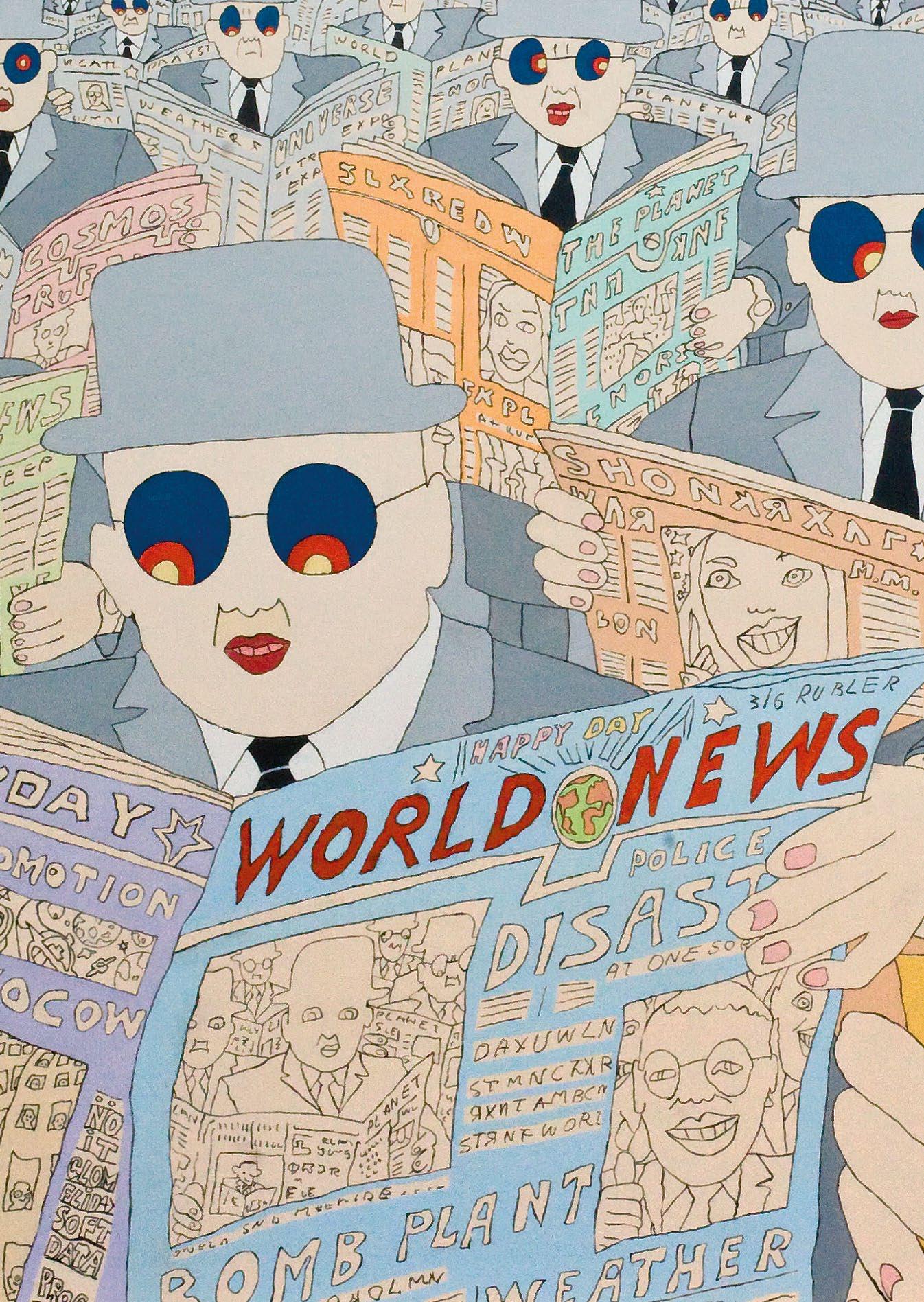

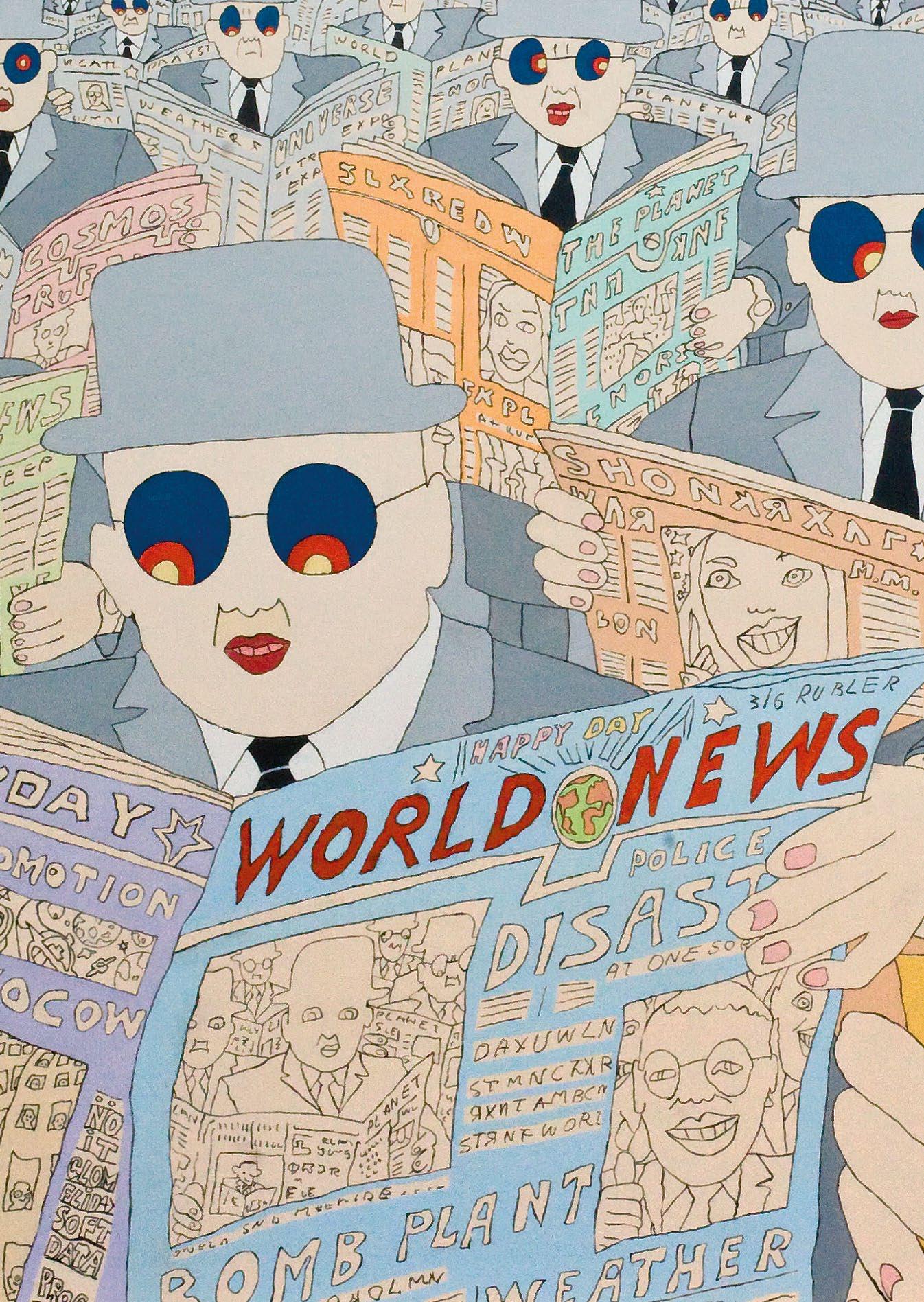

P. 11–12: “WORLD NEWS”

“Demands his paintings back – Pushwagner fights for art worth 30 million NOK” was the headline over the whole front page of Dagens Næringsliv, 26-27 April, 2008.

alone has written close to ten articles about this case throughout April 2008. Morten Dreyer responded by putting over a thousand silk prints up for sale in Oslo Art Association, an all-time record sale of Pushwagner’s prints.21 The market has caught the scent of Pushwagner, and moneyed investors have started to take up the hunt. Pushwagner’s name crops up time and again at art auctions, where figures soar into hundreds of thousands of pounds.

But it does not look as though Pushwagner is intending to lay down his felt tips or battle-axe for that reason. Neither what Pushwagner has experienced as attempts to buy him off nor retirement age have affected him.22 Success has restored his energy and his combative spirit. Pushwagner is not intent on filling his bank account. He will probably not give up before he has regained the legal ownership of his life’s work. He wants to make the paintings available and visible for the whole world and dreams of no less than a foundation and a permanent Pushwagner museum in Oslo. The art critic Tommy Olsson is among those who give him whole-hearted support.23

Pushwagner appeared at Oslo Art Association’s vernissage in spring 2008. He had, though, a joker up his sleeve – he had equipped himself with a T-shirt with “Don’t buy Puswagner!!!” (sic) splashed across it. With this slogan he attempted to prevent Morten Dreyer’s sale of the silk print series A Day in the Life of Family Man, which covered the Art Association’s walls alongside Dreyer’s collection of Pushwagner’s acrylic paintings with the same motifs. The wealthy Oslo dwellers clutched their glasses of white wine while the scrawny, toothless artist kicked the door in and scuttled around with the ironically misspelled slogan “Puswagner” on his breast.

Pushwagner is, as is now evident, no ‘puss’; he is a smart, clear-eyed strategist who “pushes” us – preferably where we don’t wish to be. You can barely be in a room with him for more than five minutes before you get disconcerted or astounded by cryptic respon-

21 Pushwagner: Hello everybody, 8 May to 1 June, 2008.

22 “Pushwagner’s former patron Morten Dreyer will give the artist the income from the sale of thousands of graphic prints. That could give Pushwagner three million kroner.” Dagens Næringsliv, 8 May, 2008.

23 He has declared this on at least three occasions, two of them in Morgenbladet: 24 February, 2006 and 30 May, 2008.

13

PUSHWAGNER´S PROTEST

ses or apt quotations from literary history.

The vernissage in the gallery Oslo Art Association was an opportune moment for that wizard at pushing, Pushwagner, to live up to the title of the exhibition, Hello everybody, in his own inimitable fashion. He performed his “hello everybody” as a burlesque protest against what those members of the public who were present must have considered a very flattering celebration of the artist. What most of them probably did not register while the artist was in action was that the former homeless Pushwagner protested because he was not consulted during the planning of the exhibition, and because he was only invited to the exhibition to throw some stardust over what he felt was a grotesque presentation and the execution of his own kidnapped children. He affirms that he has not even had an opportunity to see his pictures after his former companion acquired them through a legally and morally dubious process ten years ago.24

On the invitation to the exhibition, Oslo Art Association called Pushwagner “Norway’s foremost underground artist”. At the vernissage, the Art Association in Rådhusgata was veritably confronted with its own words. When Pushwagner is incensed, he acts without more ado; he is like the child in the H. C. Andersen’s fairy tale about the emperor’s new clothes. As a rule he pours his fury and desperation out in his drawings, but this time the eruption took place in full publicity, with his own picture children as gawping witnesses. There can be no doubt that this time he has entered an arena where the principles and rights which are at stake extend far beyond his own personal interests.25

All this commotion is taking place while the artist, who just a few years ago was in the process of wiping himself out physically, mentally and economically, is in an extremely creative phase. He is creating his characteristic drawings as never before. As social satirist and art phenomenon, he is rapidly becoming Norway’s answer to Andy Warhol, who is actually one of his many sources of inspiration.

25 “It was

14

24 “What were you thinking of when you signed? I only wanted my five pound note. That was the only thing in my head. Five quid for a beer, says Pushwagner,” in Dagens Næringsliv about the contract Pushwagner signed with Morten Dreyer in 1998. Pushwagner was allowed to see some of the pictures in summer 2008.

uplifting to see how Pushwagner drew swords …” the artist Bjarne Melgaard told Dagens Næringsliv 30 April, 2008.

STREET ART, OSLO

TIFFANI CAFÉ, OSLO

CELSIUS CAFÉ, OSLO

Alternatively, why not go even further back in time and call him Norway’s answer to Francisco José de Goya (y Lucientes), whose works are characterized by the American weekly magazine TIME as: “Terrible Beauty. Goya’s disturbing depictions of Spanish wars of two centuries ago look hauntingly familiar today.” The curator behind the Prado Museum’s Goya Exhibition, summer 2008, says in the same article: “You can see his scepticism, his loss of faith in humanity.”26 The very same words could have been uttered about Pushwagner – someone probably already has.

When the graphic novel Soft City was first publicly exhibited, at the 5th Berlin Biennial for Contemporary Art,27 I bumped into the renowned, left-wing Norwegian author Dag Solstad in front of the Pushwagner exhibits in the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, where a whole room was devoted to the work. Dag Solstad’s reflections on his encounter with Pushwagner’s dystopia are worthy of quotation: “When I see these drawings, I am conscious of having completely suppressed the robot-like nature of our existence.” Dag Solstad continued: “We have accepted a reduction of the human quality of life. I become aware of the lethargy inside me when I look at Pushwagner.” These were Dag Solstad’s words after getting what he called a “kick of recognition” from his confrontation with the almost forty-year-old drawings. Dag Solstad’s conclusion was that “Soft City still functions as social criticism”.28

You have to be blind or have acquired a severe case of elephant skin or be trapped in a particularly thick muscular armour if you do not experience something like this on encountering Pushwagner’s claustrophobic satire on civilization. Nonetheless, there are those who claim Pushwagner is “outdated”.29 That is said about a Pushwagner who has anticipated and caricatured our devotion to LCD screens (A Day in the Life of Family Man), the rule of computer technology and whose bitter satire so perfectly captures the robotization of industrial society, the creation of illness and the destruction of the

26 TIME, 28 April, 2008.

27 When things cast no shadow, 5 April – 15 June, 2008.

28 The author´s article in Dagsavisen, 12 April, 2008: “Meeting of the masters in Soft City”.

29 See for example: www.billedkunstmag.no, Skyggen over Berlin (Shadow over Berlin), 6 May, 2008. The art critic Lotte Sandberg wrote in Aftenposten, 9 May, 1995: ”Pushwagner’s bird’s-eye perspective has thus become superfluous, indeed completely wrong.”

15

«SOFT CITY» RESTORATION

PUSHWAGNER IN BERLIN

environment in the wake of a global economy. Surely that is what the critique levelled by environmentalists is all about: that we are creating the annihilation of our own planet. Even in the West we can safely say that there has been a greater degree of robotization than liberation of human qualities. People are becoming more alike and more dependent on and subject to the narrow interests of the media and industry. In other words, our humane and creative impulses are losing out to a form of mechanical control.

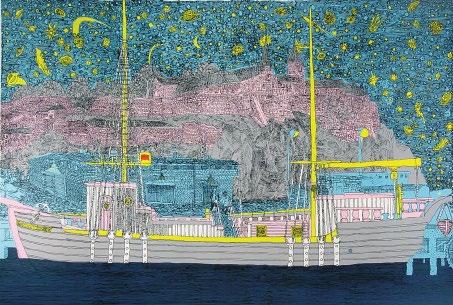

The Berlin Biennial was the acid test for Soft City. The reactions in Germany fully demonstrate that Pushwagner has hit the mark,30 whether it is in Soft City or the incredibly detailed war scene in Jobkill. Recognition was granted despite the fact that Pushwagner was the oldest artist in the biennial and his exhibited works were older than any of the other works there. Nevertheless, they were described as ‘fresher’ and ‘more refreshing’ than many of the other exhibits.31 Jobkill, which is owned by the National Museum in Oslo, was displayed along with other paintings belonging to his main work Apocalypse at a separate exhibition in the Schinkel Pavilion in the Crown Prince's Palace in Berlin during the biennial.32

With his sharp felt-tip strokes and the jumble of catatonic repetitive forms, Pushwagner’s pictures cut right to the core of unease surrounding our civilization. This is precisely what we in pure lethargy, or perhaps on account of our instinct to survive, have backed away from and forgotten. These images represent the nausea of our age, to borrow a literary expression from the existentialist philosopher Jean Paul Sartre. The news magazine Der Spiegel called Soft City “satirical mechanized life”. I could add that the graphic novel represents pure angst for civilization in a grandiose comic-strip format. If we study it long enough – which is possible now that Soft City has been published – we cannot avoid noticing how he mirrors our lives and awakens deep existential unease, which surely deserves to be called angst, something the pharmaceutical

30 “What is beyond doubt is that Pushwagner through his participation has won a new group of admirers in Berlin.” www.billedkunstmag.no, Skyggen over Berlin, 6 May, 2008.

31 See www.artcontent.de: "Soft City wirkt frischer und unverbrauchter als so manche der aktuell für die Ausstellung angefertigte Werke.”

32 This exhibition was curated by the Norwegian artist Lars Laumann, who also was exhibited in Berlin.

16

PUSHWAGNER´S DESIGN FOR THE BERLIN EXHIBITION

DAG SOLSTAD IN BERLIN

industry has done its best to steal from us with happy pills – just like in Soft City. For millions of individuals in the civilized world, life does not start before they have taken their pills, and we cannot deny that some medicines damp or conceal so-called urban ailments and therefore contribute towards maintaining unfortunate aspects of the way modern society functions.

Is it this unease that relentlessly agitates and perturbs Pushwagner? He is a manifestation of this unease; he is so prop full of it that it bubbles up inside him ceaselessly. This unease represents his life in a way. It is such an integral part of his personality that he can start to cry when looking at a child, a creature which is still innocent – unformed and full of life, like little Bingo in Soft City. Pushwagner has not just dedicated his life to observing and experiencing and, of course, depicting this unease from the rand zone –his pain is part of his personal identity and he keeps it in check by wielding his felt-tip pens. His artistic work is an obsession – literally a safeguard from madness and death.

From his position on the periphery, he has for years been sitting immersed in dreadful visions which he dispatches as silk prints, paintings and graphic novels, almost like innocent flyers, into the centre where the art scene and we others exist. This way we can take part in his pink-tinted Armageddon. Beyond a doubt, it is the end of civilization which is his subject here; that is what Soft City, Apocalypse and A Day in the Life of Family Man and many of the other works are about, no matter how well he may have camouflaged it.

In Soft City he delineates no less than the final day, the day when everything disintegrates and falls apart, with no-one observing the warning signs, and with no-one showing the slightest understanding as to why this apocalypse is the result of our deeds, nor contemplating that it is the collective effort of our working and social lives that will end up destroying us all and laying waste the entire planet. What he describes is purely and simply the suicide of our civilization. And just minutes before Pushwagner’s machines of mass destruction set their teeth into us, or roll over us with their caterpillar feet, or blow us to bits or transform us into atomic dust, we can sing “King of the road”, because we are unconcerned about what the next day will bring, while Pushwagner has throughout his whole artistic life seen it delineated so clearly.

17

JOBKILL, DETAIL

JOBKILL, DETAIL

Amongst the conglomeration of figures in the war scenes in Jobkill, we can detect a man waterskiing on a canal filled with corpses, blood and death. He is waving a banner that says “Victory”. Can we imagine a more fitting metaphor for industrialism’s annihilation of the environment or the weapon industry’s many macabre victories? Or a more terrifying glimpse into the future? Does this not echo the victory speech that George W. Bush made on 1 May, 2003, when as Commander-in-Chief of the world’s largest military power, he stood on the deck of the warship USS Abraham Lincoln in the Persian Gulf and declared that the war on Iraq had been won? On the enormous banner behind the president was a slogan that said: “Mission Accomplished”. Perhaps it is not at all strange that the prize-winning war reporter Mark Danner called the Iraq War “The War of the Imagination”.33 Here fantasy confronts fantasy: Mr Push versus Mr Soft. Fantasy and reality merge into one another.

We come to realise that Pushwagner provides our dulled adapted senses with some glimpses of awareness. That is the reason why we can experience both joy and despair when we contemplate Soft City and his other motifs. With playful irony Pushwagner calls these drawings “fairground mirrors”. Now we can hold these fairground mirrors up in front of us and ask: What is the real state of affairs in our brave new world? What is really going on inside us, the wonderful new machine people?

And while we carry on our investigation, and feel the horror emanating from the felttip strokes creeping inside us, we can spend a few moments pondering over the story behind the work, when the dynamic duo, Pushwagner and the author Axel Jensen, in harness, hatched out the idea for this superficially idyllic piece of insanity forty years ago. Soft City was only one of their many creative eruptions, each of which reflected the air of protest at the time. Without ever climbing up on barricades, they took part in the Paris uprising, the protests against the Vietnam War, the hippie ethos of ‘make love not war’ and the next phase of Aldous Huxley’s famous futuristic novel Brave New World They were living in their time, even if they were doing what they could to get out of it.

18

P. 21–22: “JOBKILL” DETAILS P. 19–20: “JOBKILL”

JOBKILL, DETAIL

33 The New York Review of Books, 21 September 2006 and The

Best American Essays 2007.