thoughts on home, embracing contradictions, and life outside of publics

I have wrestled with home for all of my life. As a person having grown up in several suburban houses and neighborhoods, with varying degrees of happiness, heartbreak, instability, and of course the ultimate discomfort of growth - all lingering around, tethered to, and absolutely confused with my perception of home, I find nostalgia, warmth, and uneasiness together whenever I search my memory for images of “home.” The way I experience home is elastic: it has stretched as I have changed, it bends to hold many disparate feelings, desires, traumas, and hopes, and it is constantly being reformed by the relationships which define home for me. I have been shaped by home in many ways at the same time that I shape my home with a mold of myself.

What images come to mind when you think of "home"?

Reading Michelle Zauner’s CryinginHMart this past year brought me to tears. The book is beautifully written and, among other things, tells the heartbreaking story of Zauner losing her mother to cancer. But more than tears of sadness, I was crying because I felt so unexpectedly seen in the pages of her memoir. Zauner grew up in a place and a house different from mine. Her descriptions of the Korean dishes which symbolized home and tethered her to her mother and her heritage weren’t meals I was familiar with, many I had never heard of. I’ve never been to an H Mart. But the sensation of being overcome with emotion from seeing something as simple as a familiar aisle in the grocery store, feelings of loss and deep love, painful misunderstanding and growth, and the home that slips through your fingers because of sadness - all of this I felt viscerally. It’s an incredibly honest description of what home might be and how it changes, which is messy, uncomfortable and beautiful, that I had never encountered in literature until reading this book. This messiness eventually helped invite a question for me: if we are able to understand home as many things, as trauma, as nostalgic, as a place of love and despair, all at the same time, what possibilities are there to use this elasticity as a way to understand complexity in other aspects of our lives?

This project, the paper you’re reading, began simply because of a discomfort of mine. An uneasiness I had about the way the term “domestic sphere” can be lobbed against women, and the way it can be completely dissociated with all other genders. In saying this, really my discomfort is in the way the domestic sphere has been assigned the role of a villain in contemporary white feminist culture and politics. I’ll try to argue in this paper that we’ve reached a turning point in feminism, an age at which we now have

mountains and foliage - the condition of the air, humidity

lying on my stomach

a swing in a backyard in Chandigarh

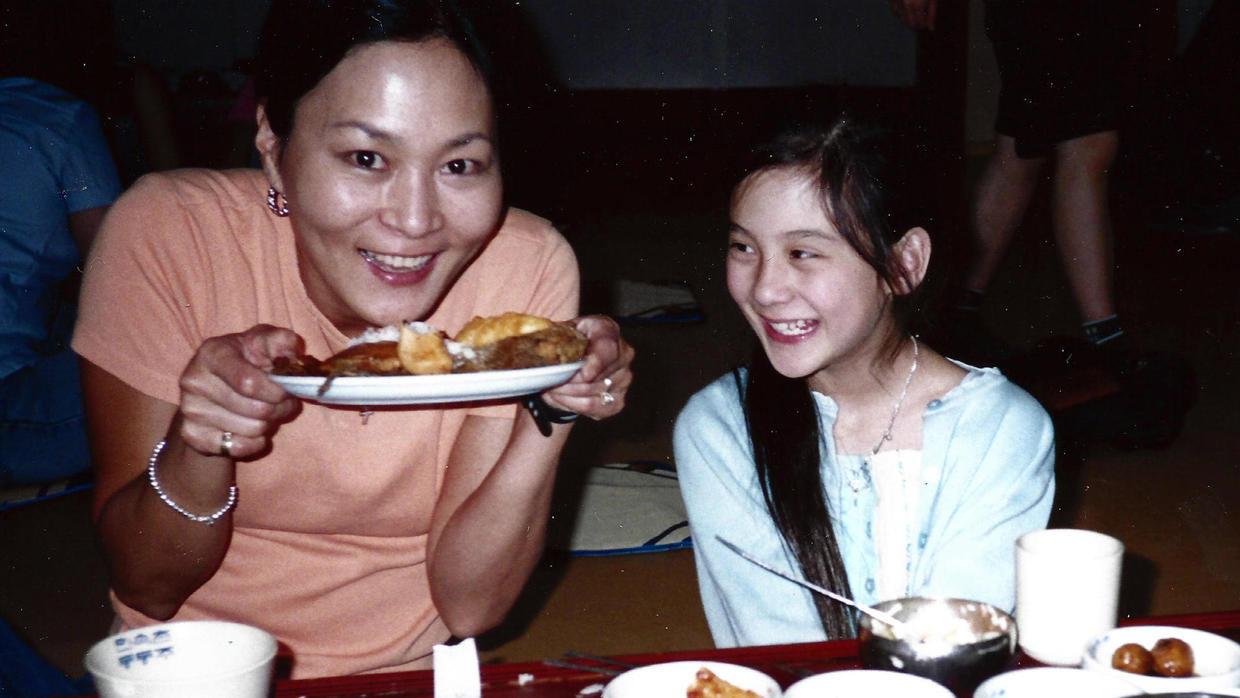

being with my mom in the kitchen

the noise of trees, the feeling of grass

Bryan Lia

Alisha

Chloe

Cristian

ghosts we must contend with and get to know, rather than let them rule our lives. It has been the case for perhaps the entirety of feminism’s history that women have, among other battles, fought to gain access to and rights in the public sphere. I wonder if this has come at the cost of the reputation of the domestic, and has led to the creation of a character who must be female and publicly facing in order to claim they are feminist.

Inspired by Zauner’s dive into herself, I decided to analyze my own life for clues as to why I am uncomfortable with and suspicious of how we talk about the domestic sphere in the first place (what am I latching onto, where do these feelings come from?). I also wanted to talk it out with some other folks (what can I learn from my peers about their experience to make sense of mine?) I will also report on some searches through academic tranches and try to square literature with various personal experiences.

As a cis-woman, I have wrestled with “the domestic sphere” for a long time. I’m familiar to the point of boredom with images of the Victorian Era, with aprons and kitten heels and kitchens. I grew up with images of Rosie the Riveter aiding women out of the kitchen and into the capitalist labor force, and of bra-burning feminists rebelling against Victorian sexual practice, all paving the way for me to feel comfortable and even empowered rolling my eyes at men and women alike who I deem to have antiquated views of my gender. However, it is more than the fact that as someone the government thinks is a woman I may be expected to have children and live bound to “the home” that makes me continue to question the “domestic.” Quite honestly, as a white woman having grown up in the United States in the twenty-first century, with a left-leaning mother, and some pretty subversive friends who would listen to Paramore with me, I’ve never felt the weight of any specific hand holding me inside, forcing me to sew or sweep simply because of my anatomy. What I sit uncomfortably with more and more is the crusty-feeling assumption that as a progressive woman, I should want to rebel against the domestic sphere in the first place.

For me, it feels like domesticity is something that I have been taught both to be the steward of and wage righteous warfare against. There may not have been a figure in my life telling me that I was expected to find a husband and care for my children. There was however the casual body shaming native to conservative Christian culture which had me constantly question my public presence, the river of little things that washes over us in a way we can’t explain, but teach us what other people assume about us and of us, my personal experience caretaking for my mother through an extreme depressive episode which has shaped the way I form expectations of myself and my responsibility to care

What images come to mind when you think of "the domestic sphere"?

homely duties, cooking and cleaning, upkeep, tending

femininity, interior lives, authenticity, softness

comfort, honesty and openness, the feelings of home

a kitchen, a domestic goddess, cooking and baking in the morning

Bryan Alisha Cristian Lia

for others. Yet at the same time, I was living through American culture in the 2000s and 2010s, growing accustomed to female role models in politics and pop culture in a way that made it all too romantic to be disenchanted with a place commonly referred to as “the woman’s sphere,” even to understand the domestic as disempowering - or at least as completely separate from a woman or girl’s ability to assert her power.

What images come to mind when you think of "the domestic sphere"?

None of these things I mentioned before - public insecurities, societal expectations, a responsibility to emotionally mediate, have to do necessarily with what many people associate with “home,” (childhood, meal time, the smell of mountain air, the feeling of your stomach on your bed) but are, I believe, intrinsically linked with the way the domestic sphere is gendered. And how in turn this gendering creates space for scapegoating the domestic itself as part of the problem. I know I am not the only woman who has learned to assign herself the intimate responsibility of caretaking that is often associated with the interior. The anxiety of others’ gaze may have nothing to do with my memory of home, but has everything to do with my confidence to exist in public space. There is a word in English for a woman whose role is to care for others and is most at ease inside.

Is there a relationship that helps define "home" or "domestic space" for you?

Here I’ll introduce an elephant in the room, or rather two - main characters, either abstract or specific, that occupy the minds of many when asked to consider domestic space - that of The Mother and The Housewife.

“Observing [my friend’s mom] made me question my mother’s dreams. Her lack of purpose seemed more and more an oddity, suspect, even anti-feminist. That my care played such a principal role in her life that it was a vocation I naively condemned, rebuffing the intensive, invisible labor as the errand work of a housewife who’d neglected to develop a passion or a practical skill set.”

Michelle Zauner, CryinginHMart

These two characters are related but quite different. One is comforting, full of wisdom, and perhaps central to our idea of home. The other is embarrassing, without

Is

there

a relationship that helps define "home" or "the domestic sphere" for you?

original thought, and most certainly forgettable. One is a superhero, the other is simply pitiful. But however different these two characters may sit in our cultural imaginary, they are expected to share remarkably similar tasks. Care-taking, Homemaking, House-cleaning, Food-preparing. Why is it that we allow mothers agency and relegate housewives to the land of oppression? In doing so I propose there’s a type of schizophrenia induced when we consider the domestic - an uneasy line that we walk that praises and expects mothering but would never dare equate motherness to housewifery for fear of speaking to the reality that the work expected of both of these women is seen as embarrassing, without original thought, and forgettable.

I have a very deep desire of being a housewife, but I'm uncomfortable with all of the connotations, like being dependent on a man, so I dream about being a housewife for myself.

Lia

Even as we move further away in time from the reality of most women in the United States being housewives, and in fact towards an expectation that women, like men, will and should participate in the workforce, we are still expectant that mothers will be at the center of domestic life, that they will do so quietly and as of right, and all the while we grow increasingly more skeptical of any trace of The Housewife appearing in a woman’s identity. In fact, we expect mothers to use their superpowers to slide seamlessly into the workforce, adeptly making use of new technologies to support evermore responsibility, employing evermore misogyny to assume these are tasks no housewife could be capable of. In her 2003 article “Preserving Domesticity: Reading Tupperware in Women’s Changing Domestic” Susan Vincent writes:

“Half a century after the invention of Tupperware, it continues to solve the problems of preserving freshness and maintaining order in the kitchen, at the same time as it helps women mediate tensions between their domestic and income-earning roles. These tensions have changed but not disappeared since, despite women’s increased participation in the work force, there has not been a corresponding separation of their association with and responsibility for the domestic sphere.”

It would seem the progress women have made entering wage-earning work has been used to further deepen efforts to preserve the invisibility of the domestic sphere in the name of female empowerment. With this lens, it’s perhaps easier to see the construction

of The Housewife not as a woman who helplessly submits to the patriarchy, but as an image used to justify patriarchal expectation of free domestic labor by asserting domestic labor itself (as well as those who perform it) is of no real value to begin with.

Do you think of "home" and "the domestic sphere" differently? If so, in what way?

I tend to think of them differently - something about the term domestic sphere is less about comfort, maybe domesticity, the process of tending to a place where you live, reinforces home?

There's some level of activity that happens in the domestic sphere, where home is more of an embodied quality. Home is a feeling, and the domestic sphere is where home is.

Home is more the definition of a space - its private and trustworthy, somewhere where comfort and love take place. With domestic sphere, I connect that term more with the actions of a space.

Cristian, Alisha, Bryan

Paradoxically, while The Housewife is meant to be dismissed, she is also meant to set an ideal, and paint her existence in domestic space as a privilege to be vied for.

“A survey of the literature, as well as of public opinion, makes it clear that Tupperware is more than a product, it is a symbol. This symbol revolves around a notion of white, middle-class domestic femininity. It is important to recognize that the image of Tupperware is not only gendered, it is also class- and race- specific. This is not a reality that pertains to all women; rather, it was a cultural construct meant to stand for the “Everywoman” that Tupperware assumed women wanted to be.”

The gendered, racialized, and class image of domesticity is a picture of who should

have access to the domestic sphere. The Housewife is a boundary both meant to keep “women in” and to keep others out.

When asking around who may be interested in participating in an interview about domestic space for this paper, I asked my friend Bryan if he would want to be interviewed. While he eventually accepted, his first response was to wonder if he would have anything to contribute to the subject. I got similar responses from other male identifying people I spoke with, but I don’t think this was because of some kind of masculinity complex because of which they were embarrassed to be speaking of domesticity that any of these people reacted this way. But I don’t think men are ever told that they have anything to do with the domestic sphere. While films like Boyhood, classically acclaimed novels like TheCatcherintheRye, sitcoms like Everyoneloves Raymond, and the countless other works of literature that narrate the experiences of men analyze and celebrate the relationships and experiences that make up domestic experiences for boys and men, I presume “the sphere” is something that men are not taught they are attached to.

In Drew J. Lanham’s The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature he writes “I am just as much a scientist as I am a black man; my skin defines me no more than my heart does. But somehow my color always casts my love affair with nature in shadow.” Throughout the book, Lanham paints a picture of himself as a person who is most authentically whole when he is outdoors, with nature, who “celebrates and sings” himself, in a self-described Walt Whitman-esque fashion. However, Lanham takes time to question why, despite his own embodied experience, others are surprised, uncomfortable, or simply find it odd that as a Black man he may have this type of self-image. The same stroke that colors “wilderness” as a white endeavor would deny a reading of Lanham’s experience of nature as “domestic” because of his anatomy and gender identity, and for that matter its loose, uneasily defined existence.

It’s worth pausing here to try and understand what is at stake when the domestic sphere is exclusionary and domestic labor devalued. It is the injustice of unpaid care work and that housing is not a human right. It is a complex web of opposing identities domestic inhabitants are expected to navigate and it is ourselves and our stories - being with my mom in the kitchen, a swing in a backyard in Chandigarh, that are erased. These stories are not valuable because they are all good, all warm, or all sweetly simple. But our interiors are spaces we experience and process ourselves honestly, a process that can be

painful for many reasons, but one individuals should have a right to.

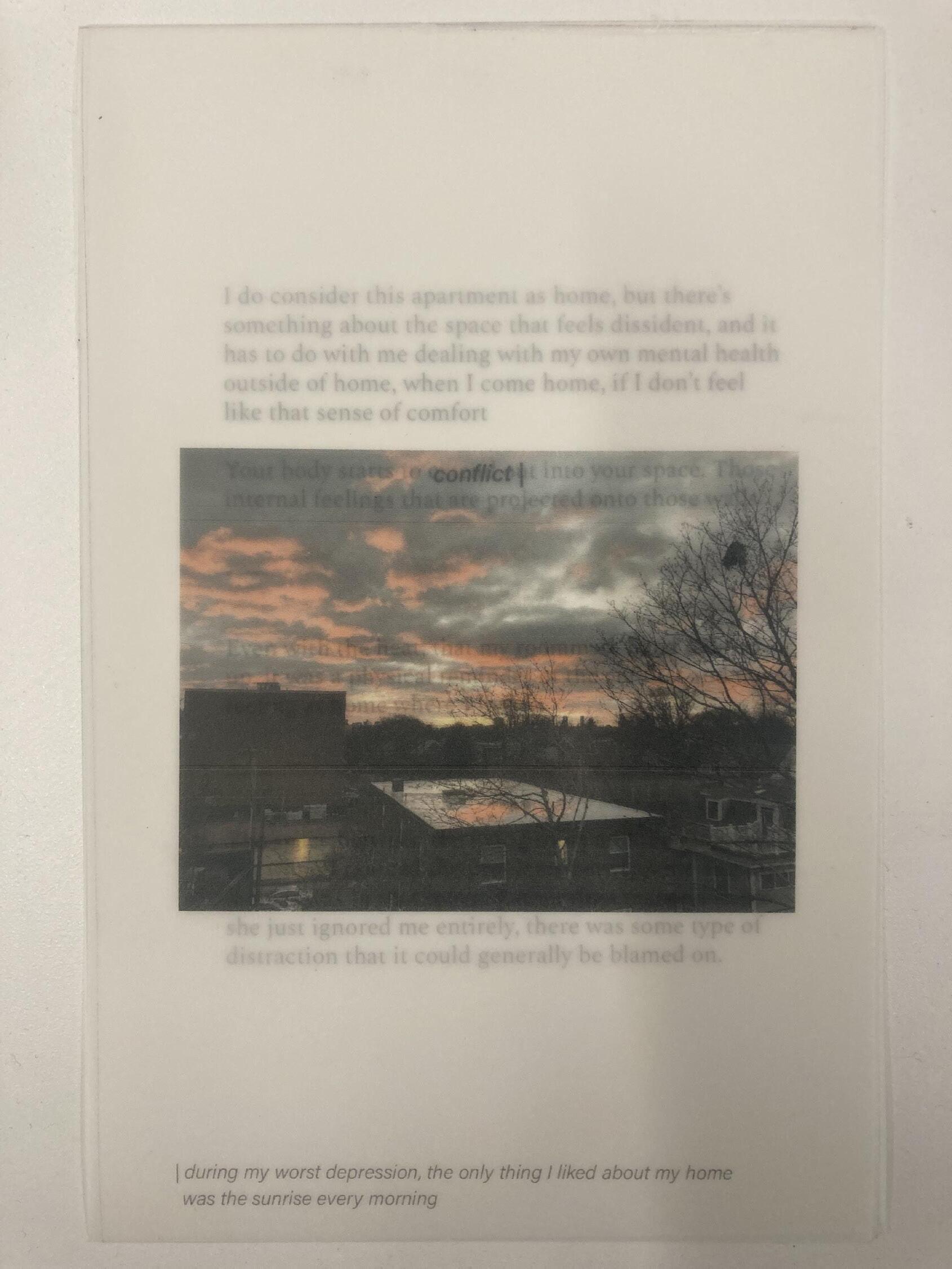

the space between the living room and the kitchen [is a space I remember most from my childhood home] but when I noticed the problems between me and my mom, it was in that space. Rather than respond to me she just ignored me entirely, there was some type of distraction that it could generally be blamed on.

theres a swing in the garden, and its a sunny day, my uncle is performing a magic trick, it's the feeling of home - a lot of things can change with trauma in life, and the relationships that were there in that space may not necessarily be there in that way anymore, [so that image] can also help me forgive certain people by being able to imagine these people and those relationships in the way they were.

Bryan, Alisha

The gendered enforcement of the domestic character as The Mother first is not capable of representing the breadth of gendered, emotional, racialized, and generational experiences that make up the domestic sphere, and second pronounces these experiences as secondary to our public, political lives.

If our domestic lives are secondary, then housing is not a right. If domesticity is a privilege of whiteness, racial housing segregation is further justified. If domestic space is a place for women to free themselves from, men will continue to exclude themselves from domestic labor because they have already been freed from it.

To be sure, women’s liberation is an ongoing battle, and the ghost of The Housewife actively haunts the environments women must and choose to navigate. Both professional and interpersonal sexism are very much so alive and well in 2023 in the United States and elsewhere. Be it the of lack of female mentorship, gender wage gaps, the gender wealth gap, the disproportionate burden of care-taking on women, unchecked sexual violence towards women in the workplace, public and domestic spaces, unequal access to education due to disproportionate financial burden, maternal status, domestic violence, lack of supportive healthcare, explicitly discriminatory

legislation - the list goes on.

However, I’m troubled by the suspicion that there is a sneaky alignment of women’s liberatory politics and patriarchal binary that creeps into popular conceptions of “feminism” - that the domestic sphere is in many ways defined by women’s oppression. Or at least, that the domestic sphere is continually devalued by its positioning as an antagonist in the fight for women’s liberation. The fact that Rosie the Riveter still holds water as a symbol of women’s empowerment simply because she presents as masculine and might hold a power tool instead of a cooking pan speaks to an obsession in specifically white American feminist thought that equates liberty with the exterior and the workplace, and subsequently ties oppression to the interior and the home. Home is a lot of things for me, but more often than not, it’s something I am constantly wishing I had. And perhaps it is because of this sense of longing, the feeling of having been without, that this problem of the domestic sits so strangely for me.

Here is something that will sound anti-feminist - anytime I see something labeled feminist because it is contesting “a woman’s place is the home” I find a pit in my stomach. There is a story arch we might all be familiar with which makes this argument, presented in Disney Pixar movies old and new. The girl who longs for adventure, who must rebel against her parents or her town at large, perhaps dress like a boy to do so, and who at last returns successfully having proven her worth and playing out the various glass-ceiling breaking moments of women’s history we are so fond of. The joyful, empowered, “we did it” feeling washes over us, myself included.

The pit in my stomach comes, though, as I consider these scenarios in mass, which together rake over again and again the same storyline. It can all feel a little too much like a pigeon hole equating a woman’s ability to self-determine with an assumed innate need for her to break with social norms, and to do this outside, in public, proving something to or conquering the exterior in the process. It is not that I have anything against adventure, or a genre of movie that relies on excitement and is meant to entertain, but I do wonder about how we might as a culture read the subtext of the stories we tell ourselves.

Building on what this subtext may signal - if forging a new path and asserting oneself onto an antagonistic but conquerable landscape sounds at least a little colonial to you, well, you’re not far off from another ghost of the domestic which is deeply entangled with the construction of whiteness. In their 2020 article “ ‘Girl’ in Crisis: Colonial

Residues of Domesticity in Transnational School Reforms” Christopher Kirchgasler and Karishma Desai sort through residues of colonialism lingering in international efforts to “empower” girls in the “developing world” by orchestrating educational reforms. Kirchgasler and Desai uncover ways in which colonial structures which imposed western gender roles on colonized populations have now been translated into NGO activity which ties “‘proper’ notions of modern girl and womanhood as conditions for social progress and economic development.”

To continue cultural narratives which assume a singular desire for women’s liberation as a central theme of domestic experience, is to continue to enforce violent gender and racial binaries onto domestic space, as well as reduce the needs and desires of women, as well as all other domestic inhabitants, to that of the politics of liberation. In her 2001 essay Feminist Theory, Embodiment, and the Docile Agent, Saba Mahmood writes:

“...the narrative of individual and collective liberty [does not] exhaust the desires of [even] people in liberal societies. If we recognize that the desire for freedom from, or subversion of, norms is not an innate desire that motivates all beings at all times, but is also profoundly mediated by cultural and historical conditions, then a question arises: How do we analyze operations of power that construct different kinds of bodies, knowledges, and subjectivities whose trajectories do not follow the entelechy of liberatory politics?”

Which of these two words do you more closely link with "domestic" ?

1) Exterior

2) Interior

Interior because I think that there is a certain level of safety that is associated with the enclosure of an interior space. I also interpreted the question as the interior self vs exterior (the tangible) and I think that domestic is something that is experienced internally first, it is a feeling and state of being that gets translated into actions or defining of a physical spaces in sometimes in tangible ways

I think in regards to how I associate domesticity with upkeep to provide comfortable space, I tend to think of interior objects (washing dishes, dusting, sweeping, etc)

Cristian, Bryan

I wonder about our need to separate oppression from progress, understand them as separate and never intersecting poles. Do we not all experience both, constantly and simultaneously? While the domestic sphere may not always be in need of liberation, home is also not always a space of comfort. We and our spaces are capable of multiplicity, though this multiplicity often involves discomfort. Trading on individuals’ potential desire to find comfort in order to flatten and categorize (as opposed to explore and embrace messiness), is an all too common tool of patriarchy, capitalism, and colonialism.

Can you describe a time that you have felt at odds with a place you have considered home?

I think it was at odds because in general we had a very happy household but [a situation in my family] definitely took a toll on my mom, me and brother and so it becomes tough because you feel safe and comfortable in a space but there are these moments you look back on and you're like "oh, maybe that wasn't so happy."

Cristian

Turning back to CryinginHMart as a guide, I pulled scenes that allowed me to process different ghosts of the domestic sphere in relation to lived experience. I chose moments of Zauner’s life to pair with ghosts I myself was carrying, layering them together because the moment described in the book helped me understand domestic baggage differently, stood in direct contrast to my own rigid assumptions, or softly gestured at some kind of nuance. Are the ghosts of the domestic any less relevant today? Do they cloud our ability to see our lives for what they are? Are our lives any less valuable because they are wrapped up in loss, depression, or oppression?

Anne Anlin Cheng defines “ornamentalism” as a process through which Asian women are not only objectified, but equated with specific objects, serving the cultural space of ornament, likened and tethered to things associated with Euro-american conceptions of Asian-ness. Through ornamentalizing, Asian women are reduced to the thinness of material, the finite space of an object, and only the complexity granted by projecting

a kitchen

anonymous facebook post: “young women listen to me, it is NOT demeaning to fix your man’s plate. it is NOT a feminist issue.”

personhood onto a thing that is not a person, does not breathe or feel itself, and is therefore a vessel of the projections of its viewer. This process can be traced in the way that Asian women are siloed and othered, in patterns of both physical and structural violence. Traces of a similar process can be seen in white feminist obsession with liberation, and housewives are understood as equivalent with the images and spaces they are drawn into.

However, while Cheng describes ornamentalism as a method used to flatten Asian women, she also asserts that Asian women have the ability to use and craft

zillow listing for my mother’s house, an investment

photograph of Global Women’s Strike protest with sign that reads: “a care income for all caring work for PEOPLE & PLANET”

Can you describe a time you felt ownership over a place you associate with home?

Having a space furnished makes it feel like home - my family loves to host, which is a big part of home, hosting and making people feel comfortable and people gathering, makes me feel at home. In the era of trying to get a couch, I was so upset when it didn’t fit.

London junior year abroad, it’s uncommon in the UK to have a roommate in your room, but because everything was so expensive, we shared a room and we shared a bathroom, and it was the smallest place ever - an airplane hanger bathroom. But I was just so proud that, people would come visit me, and I would just say I can’t wait to show you where I live.

Chloe Lia

ornamentalism in order to enforce their visibility. This is because there is an underlying falsehood in the premise of individuals being defined by others, in that individuals are not defined by others. At least not in full.

I’m proposing an alternative way of understanding the domestic sphere. I propose that domestic space has always been inherently elastic. Because of its intimate linkage with personhood, interiority, gendered oppression, and capitalist exploitation, the domestic sphere is the site of constant contradiction, negotiation, and remaking.

Through some digging done for the sake of this project, much of the academic work I found dealing with the domestic takes one of two approaches, to frame domestic space as a site for potential liberal intervention, or as a physical space that mirrored the idea of “house” which is largely used for sleeping and eating, or holds an implication of some form of capital claim whether through ownership or renting. But through conversations with my peers, it was obvious that domesticity was thought of as an interior not because it was confining, or because it was an architecture, and while it differed from how people thought of home, it was deeply entangled with home, dealing with the trappings of what home may be, whether that is maintenance and care, or the casual, formal, violent, or nostalgic happenings that take place within “home” that activate it.

Can you describe a time you felt ownership over a place you associated with home?

It is these happenings and how they are valued and characterized that I am interested in. Giorgio Agamben, borrowing from Michel Foucault and Hannah Arendt before him, describes “the politicization of bare life” in his 1998 work HomoSacer:SovereignPower and Bare Life. Agamben defines this as the ways in which our livelihoods, the fact that we live (as in to be alive in a biological sense) - we sit on swings, we cook meals, we wash the dishes, we are too sad to do wash dishes - is called into question by our politics, our public lives. When our bare, or as I am choosing to call them, domestic lives, are politicized, and important question comes to mind. What could be the point of politics without caring for domestic lives, on which the public is built?

Why did I find it helpful to read CryinginHMart as a source for the study of domesticity? Perhaps because memoirs are stories for the sake of stories. More than anything, they are selfish, a vehicle through which individuals can speak truth to their bare lives, by using sharing as an excuse to do so. More than any other term, in speaking with my peers “honesty” and “authenticity” were used to describe the domestic sphere.

Chloe’s childhood living room

the dishes I can’t bring myself to wash, that I am ashamed of

protests over gun violence in Nashville, days prior two legislators’ expulsion for participating in protest

Cristian, Alisha

Alewife Nature Preserve, a year before Aaron proposed to me on this dock.

There is something to be said for privacy to make honesty possible. In 2023, as Americans wring their hands over the increasingly entrenched surveillance state, and certainly in the wake of Dobbsv.JacksonWomen’sHealthOrganization, the right to privacy is perhaps now more than ever a battleground in our modern politics. But I also wonder about what else it is about our publics that disables honesty, disincentives authenticity, and excludes “bare life”? Hostile architectures, the lack of shady sidewalks, sidewalks with insufficient curb cuts, police violence, the plastic crisis, racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, climate change. Could these things be possible if politics

Our yard in Madison TN, I learned to be proud of our neighborhood watching Mom love and care for our home.

valued domestic life? If we could think of domesticity as elastic - a way to move through space - if we thought of domesticity as valuable, if we considered valuing bare life as nonnegotiable, what could our publics look like?

Throughout the conversations I had for this project, I found moments that I can say were probably more valuable to me personally than to this project’s academic integrity, but nonetheless helpful to draw together themes that help express the ways in which domestic experience stretches temporally, because of relationships, spaces, and political being, as well as the way we map ourselves onto our domestic experience. Many people expressed joy found in domestic space because of the relationships they experienced and trust they earned with both people and objects. People’s idea of ownership was almost never associated with the notion of capital but of agency and markings. Feelings of shame which I had never heard another person speak to so clearly before in a way that I have felt so closely, related to gendered notions of responsibility around upkeep and cleanliness, as well as a home’s ability to absorb and reflect depression as much as joy or nostalgia. The stacked papers shown as images in this paper, rather than symbolizing ghosts, are translated to layers, the deep waters that we swim through which fill up our lives for both better and worse.

~ In wanting to “expand” this project into a fulfledged project, one with a point, one that I could write a paper on and turn it in as a work relevant to a design school history seminar, I asked how individuals felt either supported or unsupported in being able to carry out their most honest lives by their environments. I was exploring the idea that domesticity is an infrastrucutre, not defined by housing or architecture, but by a person’s ability to experience the domestic as they navigate their surroundings in all parts of their lives. By and large these responses had to do with choice and the ability to further relationships. The magic of wandering, and the ability to extend your home as far as possible, the freedom of mobility, and the simple pleasure of walking to the grocery grocery store.

This ultimately found me considering the title H Mart as part of a book title, and the centrality of simple human needs like food and errand running in order to maintain a relationship with one’s identity through space - for Zauner this can be accessing her mother’s Korean cooking, and the memories of walking through aisles of plastic packaging and pungent smells at H Mart which gives the ability to find “a piece of ourselves.”

Chloe and Lia walking on a veryyyyy cozy snow day in Boston

I was struck several weeks ago when I encountered the work of Design Studio for Social Intervention and the way they pushed the kitchen into public space, simply asking, “if people had access to a shared kitchen, a place to learn about cooking

and food together, sharing recipes together, how having something like that in your neighborhood might change your life?” What could happen to the way we think about domesticity if it could be part of public service, rather than a private privilege? I am moved by the possibility that instead of domestic space being exploited by capitalism, domestic spaces may one day use the public sphere as a means of concretizing their worth.

However, as I say this, I am reminded of yet another one of Zauner’s passages, one where she is describing the feeling of writing her mother’s eulogy, days after her passing.

"I wanted to uncover something special about her that only I could reveal. That she was so much more than a housewife, than a mother. That she was her own spectacular individual. Perhaps I was still sanctimoniously belittling the two roles she was ultimately most proud of, unable to acceot that the same degree of fulfillment may await those who wish to nurture and love as those who seek to earn and create. Her art was the love that beat on in her loved ones, a contribution to the world that could be as monumental as a song or a book."

Is my need to equate the intimacy of domesticity to macro world of infrastructure similarly belittling to the themes of authenticity and interiority I worked in this paper to argue are so valuable and overlooked? Is it perhaps a sign of a little embarassment and the bravato that comes after someone is a little too vulnerable in public, a kind of protective reflex? Despite my these insecurities, what I hope I have conveyed in this paper is my conclusion that the domestic sphere is valuable even if the specific value you find were not to be seen by anyone other than yourself. (But this, too, makes me wonder, if domesticity were to be a political force or infrastructure, how can it be seen as so not because of an assumed need for liberation, but because we take seriously our desire to look for ourselves, to be allowed to seek and find what we need, and to commune with what and who we care for?)

~

Several people shared that they felt ownership of their homes when they were able to share it with people they loved. Alisha’s mom was so kind to find this picture of Christmas time in the Kapoor household. A very warm thank you to Alisha and Mom for sharing this memory.

In the opening lines of One World in Relation an interview documentary recording the thoughts of poet and philosopher Édourd Glissant, Glissant describes the impossibility of an architecture that could contain the boundless essence of his mother - “a presence that no architecture of tombstones, baroque or pretentious, stupid or naive, with its clumsy devotion to a denuded grass, could have contained.” It is possibly just as naive and clumsy to assume any architecture or politics could define domestic space, or the essence, desires, and specifics of any individual, race, gender, nationality, any other identity. Although we are intimately linked with our architectures, are emotionally entangled with the dishes in our sinks which haunt us, are molded by the furniture we arrange in such a way that we can be proud, although we leave traces of ourselves there, we will not be constrained to them or contained by them because we cannot be. At its very most benign, our desire to define the domestic as houses and mothers could be attributed to a desire to know ourselves. However, the ability to accept what we cannot find, what alludes us, what Glissant calls our “right to opacity,” or the right to not have to understand, ironically allows us not to create confinement for ourselves. Accepting domesticity’s elasticity may allow us to stretch our homes to architectures, interior or exterior, we never thought possible.

To the friends who participated in this project, thank you so much. It has been an emotional and at times confusing project to work through, one that feels incomplete, one that I’m still sitting in. But the ability to ask you your thoughts and learn from your experiences has been so incredibly valuable. Thank you for sharing your time and your space, your memories and feelings with me. Thank you for sharing pictures of yourselves and your lives with me, it has in a way helped me find pieces of myself.

Michelle Zauner. Crying in H Mart. Alfred A. Knopf, 2021.

Bryan Pickle. Personal Interview. 3 April 2023.

Cristian Umaña. Personal Interview. 14 April 2023.

Alisha Kapoor. Personal Interview. 17 April 2023.

Chloe Reeves. Personal Interview. 19 April 2023.

Lia Green. Personal Interview. 19 April 2023.

Female Mentorship:

“Mentoring Women in the Workplace: A Global Study.” DDI, https://www.ddiworld. com/research/mentoring-women-in-the-workplace.

Gender Wage Gap:

Carolina Aragão. “Gender Pay Gap in U.S. Hasn't Changed Much in Two Decades.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 1 Mar. 2023, https://www.pewresearch. org/fact-tank/2023/03/01/gender-pay-gap-facts/.

Gender Wealth Gap:

Ana Hernández Kent and Lowell R. Ricketts. “Gender Wealth Gap: Families

Headed by Women Have Lower Wealth: St. Louis Fed.” Saint Louis Fed Eagle, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 12 Sept. 2022, https://www.stlouisfed.org/ publications/in-the-balance/2021/gender-wealth-gap-families-women-lower-wealth.

Care Burden:

“Not All Gaps Are Created Equal: The True Value of Care Work.” Oxfam International, 25 May 2022, https://www.oxfam.org/en/not-all-gaps-are-created-equal-true-valuecare-work.

Unchecked Sexual Violence: “Explore the Facts: Violence against Women.” UN Women | Explore the Facts: Violence against Women, https://interactive.unwomen.org/ multimedia/infographic/violenceagainstwomen/en/index.html#nav-3.

Danielle Campoamor. “How Many Sexual Assault Reports Did the FBI Ignore before Larry Nassar?” FBI History Of Ignoring Sex Abuse Like Larry Nassar, https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2021/07/10582933/larry-nassarfbi-sexual-assault-claims-ignored-history.

Arturo Samaniego, et al. “Companies Ignore Sexual Harassment in the Workplace - The Bottom Line Ucsb.” The Bottom Line UCSB -, 1 Mar. 2017, https://thebottomline.as.ucsb.edu/2017/02/companies-ignore-sexualharassment-in-the-workplace.

Access To Education:

Abi Richards. “Girls' Education: Challenges and Recommendations.” Rights of Equality - Promoting Gender Equality and Women Empowerment, 4 Dec. 2022, https://www.rightsofequality.com/girls-education-challengesand-recommendations/.

Susan Vincent. “Preserving Domesticity: Reading Tupperware in Women's Changing Domestic, Social and Economic Roles.” Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne De Sociologie, vol. 40, no. 2, 2003, pp. 171–196.

J. Drew Lanham. The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man's Love Affair with Nature. Milkweed Editions, 2017.

Christopher Kirchgasler and Karishma Desai. Kirchgasler, Christopher, and Karishma Desai. “‘Girl’ in Crisis: Colonial Residues of Domesticity in Transnational School Reforms.” Comparative Education Review, vol. 64, no. 3, 2020, pp. 384–403.

Saba Mahmood. “Feminist Theory, Embodiment, and the Docile Agent: Some Reflections on the Egyptian Islamic Revival.” Cultural Anthropology, vol. 16, no. 2, 2001, pp. 202–236.

Anne Anlin Cheng. Ornamentalism. Oxford University Press, 2021.

Giorgio Agamben. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford University Press, 1998.

Manthia Diawara, Director. Lydie Diakhaté, K'a Yelema Productions, Producers. Edouard Glissant: One World In Relation. Third World Newsreel, 2010.