INTERGENERATIONAL FARMING

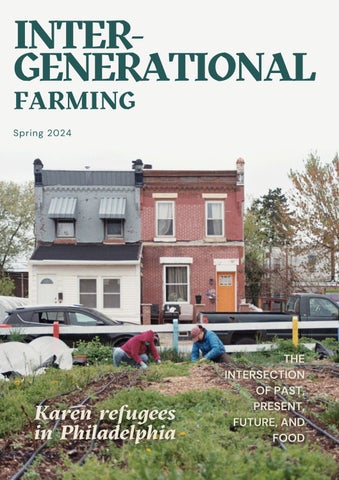

KarenrefugeesinPhiladelphia(PhotosprovidedbyClaraVarandi-True)

After being displaced by Myanmar’s civil unrest, Karen refugees find comfort in growing traditional foods in Philadelphia.

Novick Urban Farm was founded in 2012 by the Novick Corporation with the goal of providing nutrition and agricultural education, as well as improving food access Around the same time, recent Karen refugees from Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, were introduced to Novick Farm, and have worked with them since, growing produce culturally important to the Karen people, such as chin baung, bitter melon, and long beans

In the Fall of 2023, Novick Farm lost their land to the corporation’s expansion, and now have a year to transition the Karen farmers to their own growing sites in Philadelphia

With such heavy histories that Karen refugees come from and so much uncertainty of the future of their growing, different generations are impacted in different ways This profile highlights a conversation with a leader in the Philadelphia Karen community who works to bridge generational gaps through growing traditional foods.

KarenfarmersandNovick FarmOperationsDirector ClaraVarandi-Trueweedat

KarenfarmersandNovick FarmOperationsDirector ClaraVarandi-Trueweedat

oneoftheirplotsin SouthwestPhiladelphia

“When I came to United States, I thought I almost died because I couldn’t find my food right away.”

Born in the Kayah state of Burma,

Naw Doh first fell in love with growing food when she learned as a girl from her family

In the Kayah state, where the Karen are from, many generations grew up growing their own food to provide for their families Naw Doh says, “We survived from doing farm work Because we didn’t have markets, we had to grow our own food ”

Despite most adults encouraging kids to study hard, go to school, and get a good job, Naw Doh felt at peace at the farm.

“I love seeing the plants grow up. It’s a powerful feeling... It’s so peaceful. And it smells good.”

Upon coming to the U.S. in 2002, Naw Doh began work as a nanny. Speaking on the importance of food, she recounts,

“You know, when I came to United States, I thought I almost died because I couldn’t find my food right away. ” Although her boss would bring her rice, she soon ran out. She thought to herself, “Oh, I don’t know if I’m gonna survive or not I didn’t know I prayed and went to bed I was really scared! I thought without rice I was gonna die.”

Her boss often traveled for work, bringing Naw Doh to take care of the baby. While traveling so much, Naw Doh felt uncertainty about not being able to find her traditional food in unfamiliar places.

NawDoh(bottomright),Karenrefugees,andClarapull weedsalongtheedgesoftheirgardeninSouthwest

“My boss traveled to many beautiful countries with a lot of good food But it didn’t really taste like my food So it made me tired I put a small pack of rice in my luggage…I didn’t know where we were gonna go. And at the time, my English was very limited so I didn’t know how to ask…It made me scared. That’s why I carry my food wherever I go. ”

Now, Naw Doh is one of the main leaders of the Karen community in Philadelphia With her connections with many generations of Karen refugees in Philadelphia, she often translates for American researchers and healthcare workers who want to learn more about

the benefits of traditional foods When they ask Naw Doh about the benefits, her response used to always be the same: “I don’t know. My parents ate it, so I do too ”

Not satisfied with this answer, Naw Doh turned to refugee parents and

elders. She learned from them about medicinal benefits of many foods–such as young mango leaves, pennywort, and papaya–translating and conveying this knowledge to interested Americans.

Naw Doh emphasized the value in learning from and

respecting the elders: “The first fruit of anything we plant belongs to God. So we always present the first fruit to the pastor or the elders who can bless the fruit ”

Clara&Karenfarmerson growtogetherinthe

gardensinSouthwest Philadelphia

“I want to teach them because their parents survived in the jungle as farmers. That generation survived with growing.”

Using her own knowledge and what she’s learned from the elders, Naw Doh works at three local schools as a language counselor, helping bridge generational gaps between adult refugees and their kids through language, growing, and traditional cooking.

“In my community in Philadelphia, young girls are not interested in farming... When I invited them to Novick a few years ago, they said, ‘Oh, it’s too hot and dirty and yucky!’ They saw the worms and they ran away They said, ‘We’re so tired.’ So I want to teach them because their parents survived in the jungle as farmers. That generation survived with growing.”

Because of Myanmar’s civil war, many kids grew up in refugee camps, making their childhood vastly different from that of their parents.

Naw Doh explains that in the camps “whatever people gave to you, you had to eat…You didn’t know how to make it by yourself And they were born at the camp so they didn’t have the opportunity to try country styles and country tastes It’s just not special for them…So that’s why they can easily eat American food…But for adults, we cannot adapt to this food because we grew up in our original country with traditional foods ”

In addition to wanting younger generations to be able to cook for themselves to save money and make healthier meals, Naw Doh hopes teaching them to cook traditional foods will bond families Because to Naw Doh, family is at the heart of tradition.

“I had a nice family Whatever we had, we ate together and it made us so happy. We enjoyed the feeling of eating the food together Now, when we cook traditional food, we share it with each other because many other families are busy and cannot cook everyday Some families cannot cook because it takes time…So that’s why it’s special Together, as a family, you feel whole.”

Because younger generations didn’t grow up valuing their

traditional foods, Naw Doh is worried about the impacts this will have on their families. “I don’t want separation within the family. Like, ‘Oh, the kids eat this food and the adults eat this food ’ No, I want them gathering together We are family We don’t want a divide. I especially don’t want to lose family and that feeling of togetherness.”

Naw Doh notices that younger generations still love the taste of traditional foods, they just don’t know how to make them. So, to avoid burnout, Naw Doh starts by teaching them easy meals, like spring rolls, pizza, and salads, all using traditional produce grown in the farms But after losing their land at Novick, there is much uncertainty in where and how this produce will be grown

bytheKaren

KarenandNovickfarmersenjoyamealtogetherafteramorningof

“We are family. We don’t want a divide. I especially don’t want to lose family and that feeling of togetherness.”

Top left: traditional Karen dish of tomato, egg, mixed beans, cabbage, and rice

Bottom left: Karen farmer plants cucumber seeds

Bottom right: Farmers fill their plates with traditional food prepared by the Karen

Naw Doh and Karen refugees grew at Novick Farm for over 10 years, and now they are mourning not only the loss of this land, but of the work they put into it.

“Oh, I don’t know how to describe the feeling. We spent a lot of time getting the land ready to use. But it’s time to move on. It makes me feel depressed. How are we gonna grow? Where are we gonna go? My community here said, ‘Oh, so we are gonna lose our food and our traditional things ’ That made me more sad ”

“We spent a lot of time getting the land ready to use. But it’s time to move on. It makes me feel depressed.”

AKarenfarmer’ssonholdsupadandelion pickedfromthegardens

To Naw Doh, losing this land after years of learning how to grow on it feels like if you climbed a mountain and you had to start in the middle “It’s very difficult,” she said

As refugees, the Karen people spent a long time moving from place to place They came to the U S with hopes of settling down, but now they are forced to move again But just like they learned to be resilient to changes in the past, Naw Doh says, “We try to think about how we had to move place to place in the camps I remind myself about that in each new place we grow ”

Now, as the Karen farmers grow on three smaller plots of land spread

throughout Philadelphia, Naw Doh makes sure to save seeds so they can continue growing their traditional produce for generations to come

Even though this adaptation is difficult, Naw Doh continues to be motivated and inspired by the thought of continuing traditions for future generations and for the seniors Naw Doh says, “It’s very difficult, but I have to find a way because, for the seniors, they love to be in the gardens They talk together, they feel close to each other You can see the smiles on their faces when they are in the gardens I think they’re healing, you know ”

“You can see the smiles on their faces when they are in the gardens. I think they’re healing, you know.”AKarenfarmer’ssondecorateshismother’shairwithdandelionspicked fromthegardens

Over the next year, the Karen will be growing at four sites in Philadelphia: Southwest Philadelphia, Taggart Elementary, Growing Together gardens, and FDR park. However, their goal is to campaign to secure permanent land in South Philadelphia. What’s next?

Reach out to

novickfarm@gmail.com to learn how you can best support the Karen in their fight for securing permanent land to continue growing their traditional foods that brings generations together.