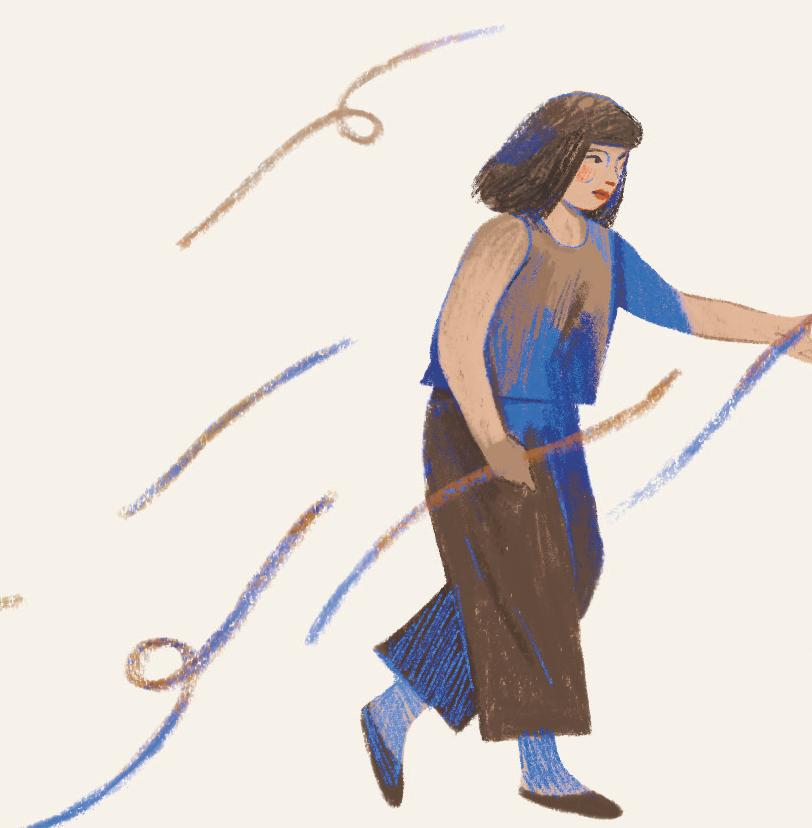

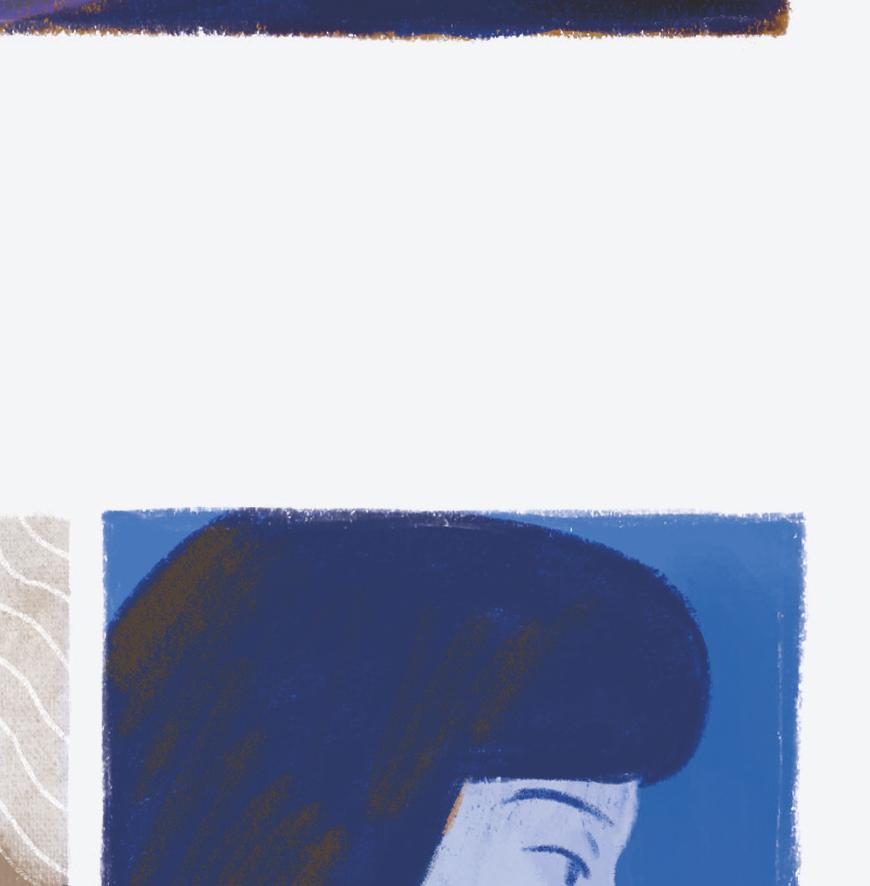

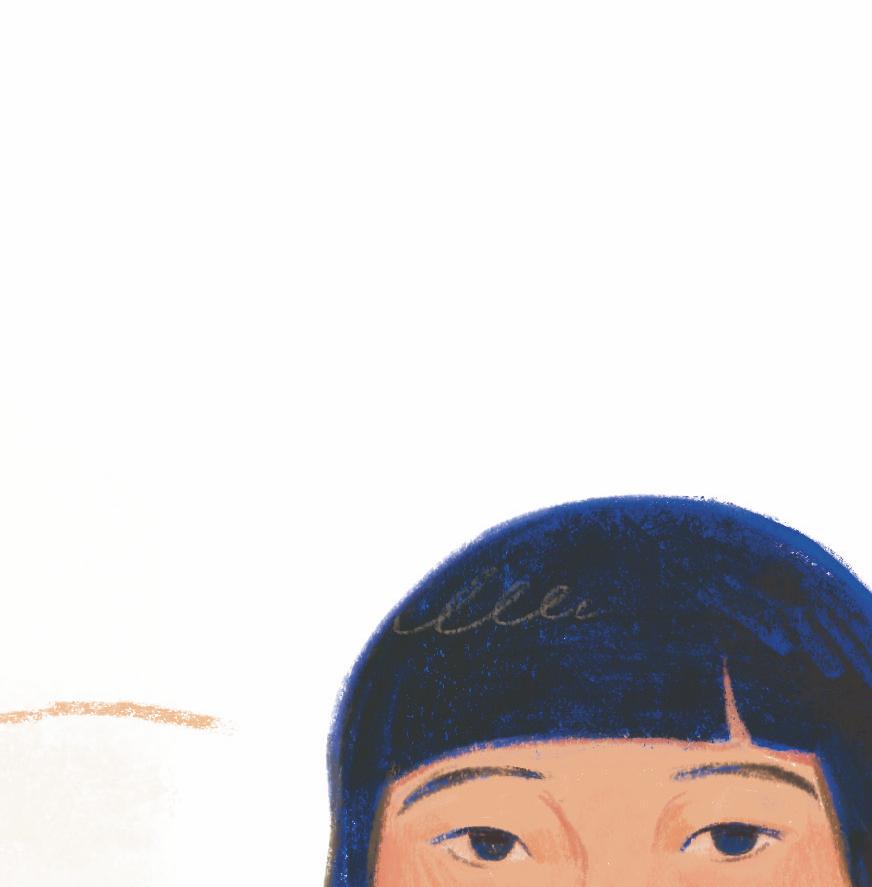

The Brilliant, Resilient Life of Artist Ruth Asawa written by Caroline McAlister; illustrated by Jamie Green

Winter 2025

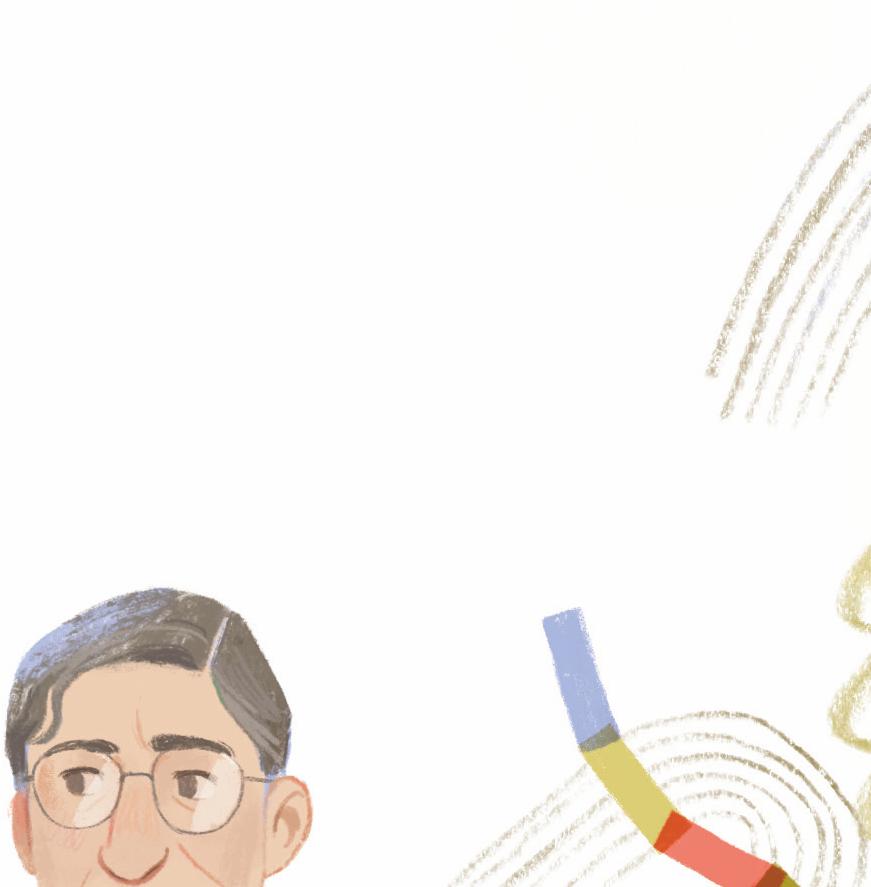

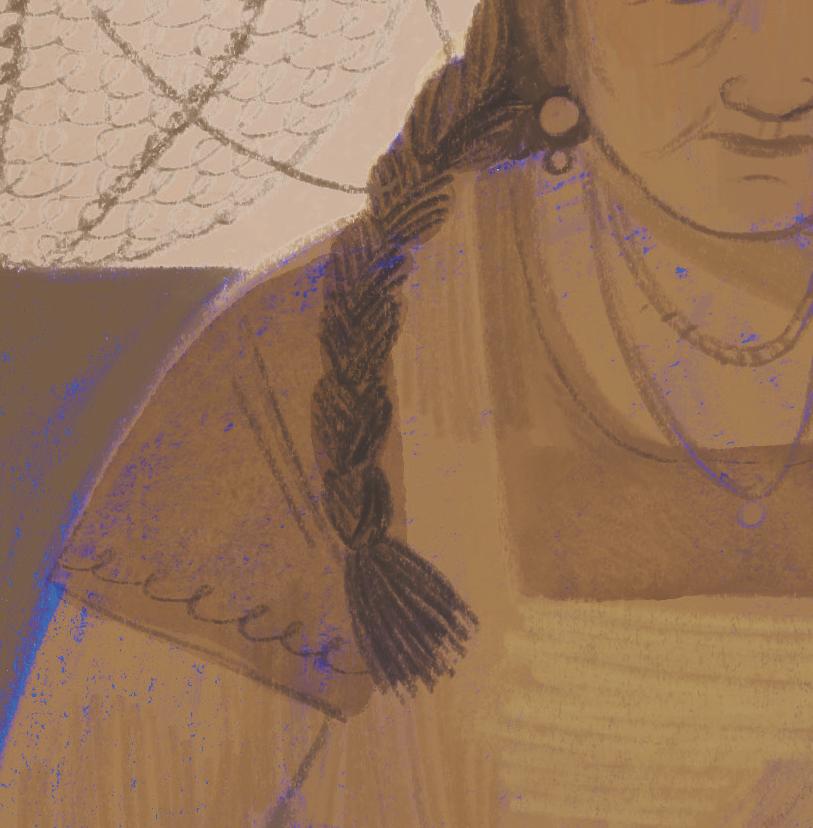

In this sweeping biography of famous sculptor Ruth Aiko Asawa, Caroline McAlister and Jamie Green trace the artist’s life from childhood to living in a Japanese incarceration camp to the remarkable career she would have.

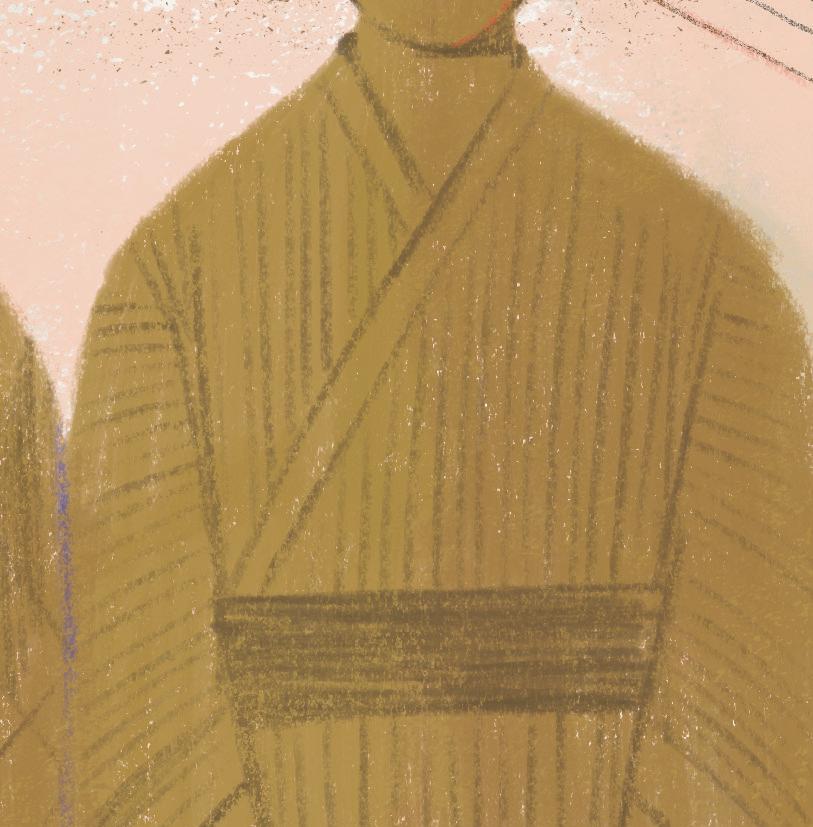

Growing up on a dusty farm in Southern California, Ruth Aiko Asawa lived between two worlds. She was Aiko to some and Ruth to others, an invisible line she balanced on every day.

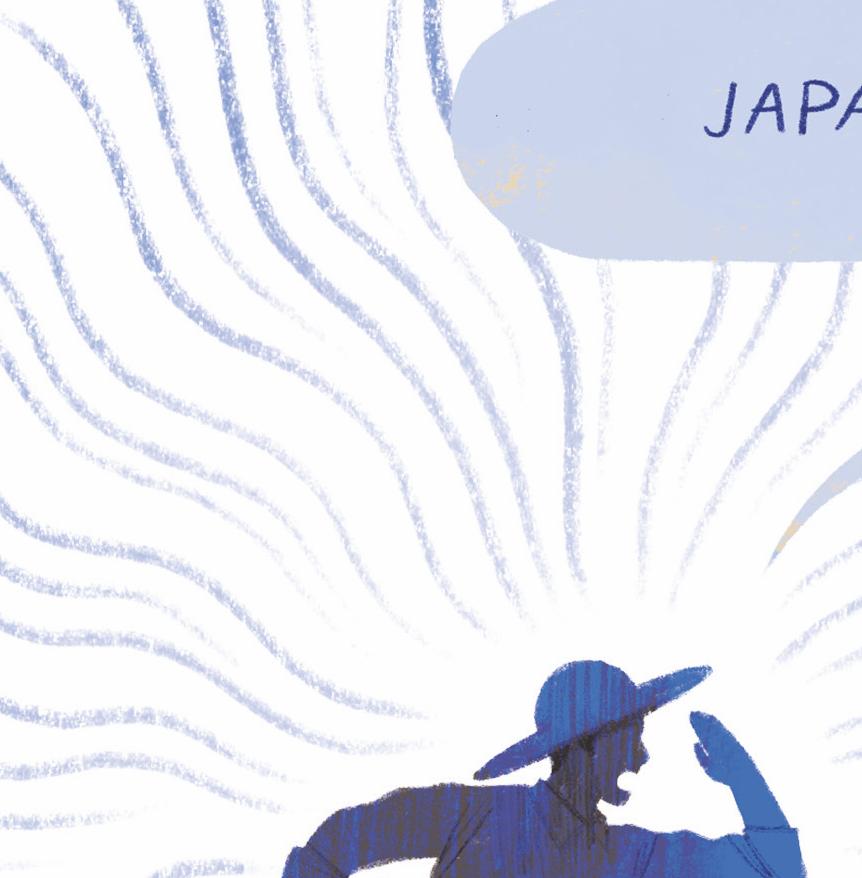

But when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, suddenly she was only Aiko, no matter how much her family tried to cut the lines that connected them to Japan. Like many other Japanese Americans, Ruth and her family were sent to incarceration camps.

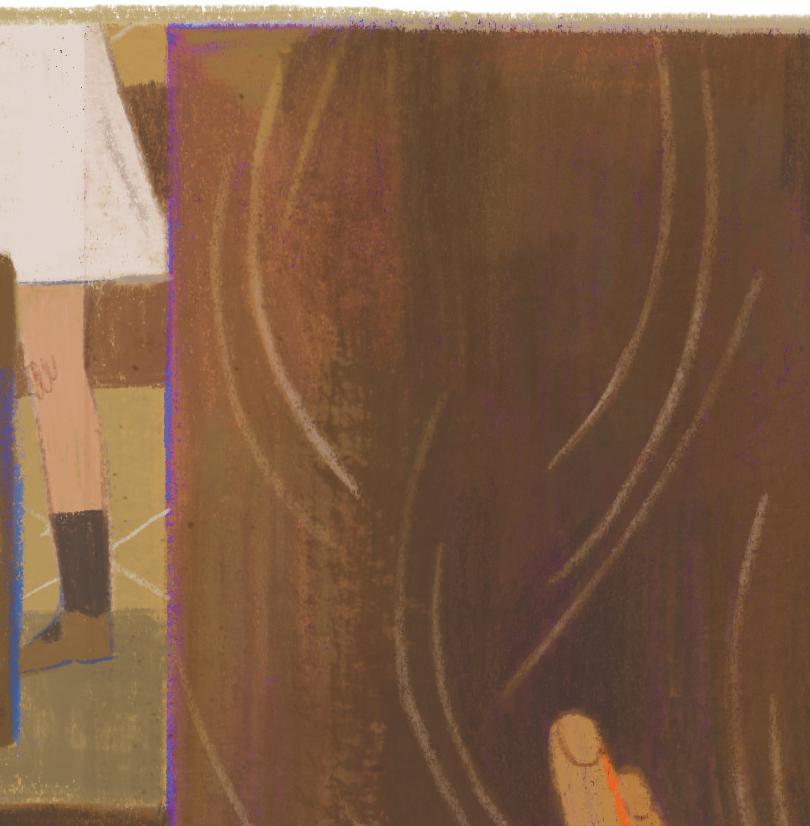

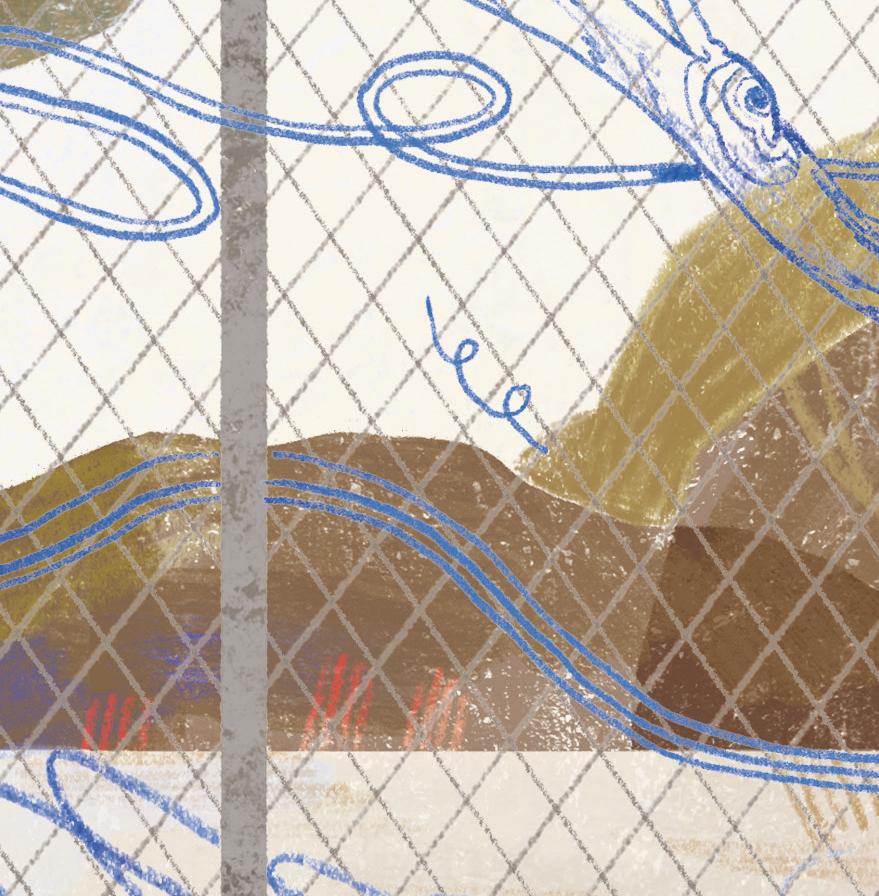

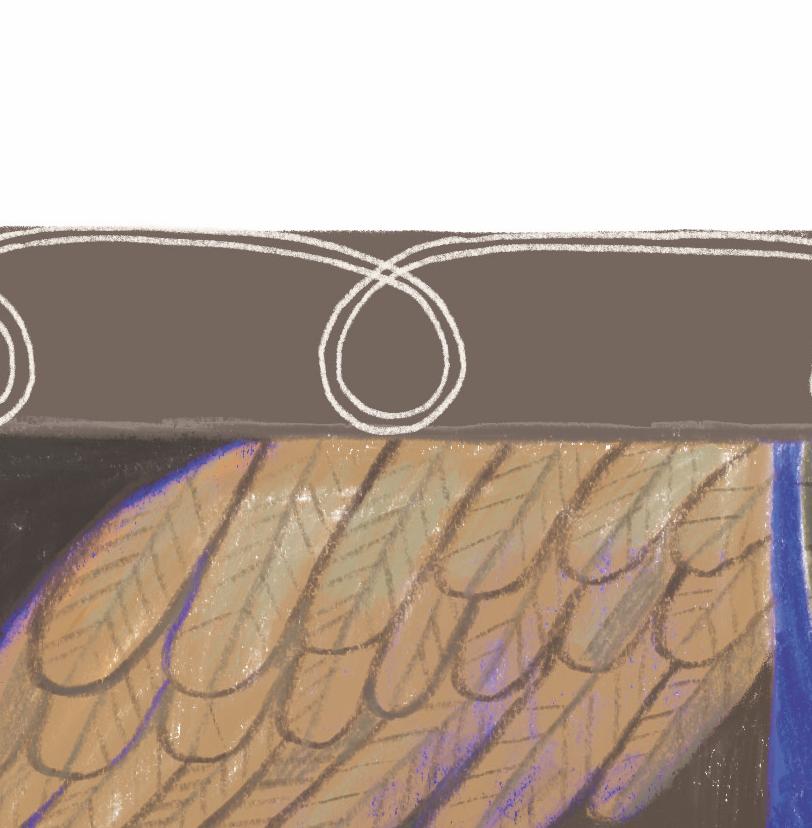

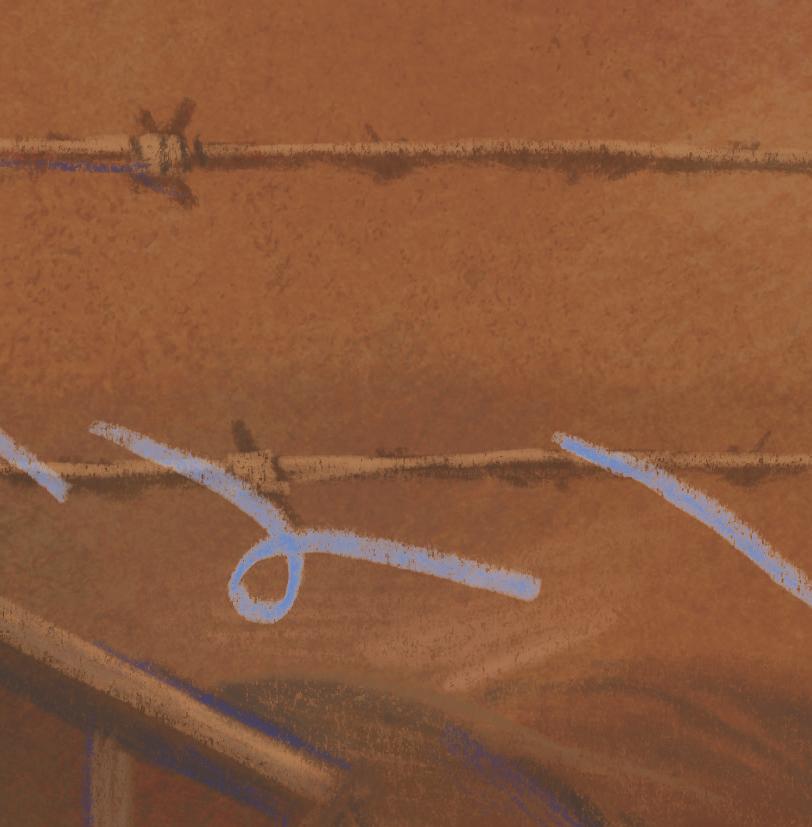

At the Santa Anita racetrack, Ruth ran her fingers over the lines of horsehair in the stable stalls the family had moved into. At the Rohwer Relocation Center in Arkansas, she drew what she saw—bayous, guard towers, and the barbed wire that separated her from her old life.

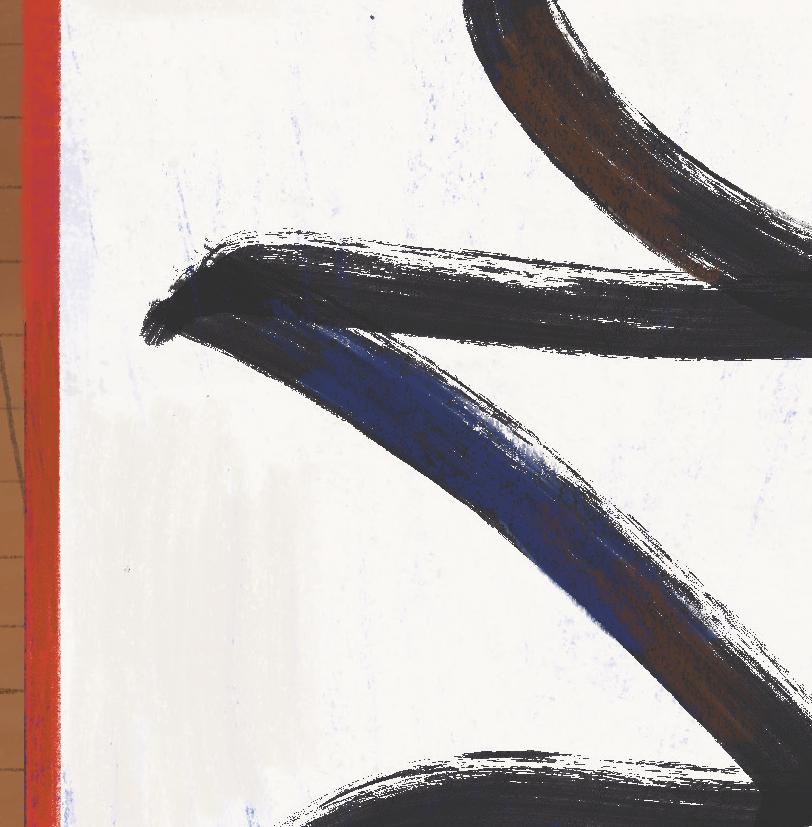

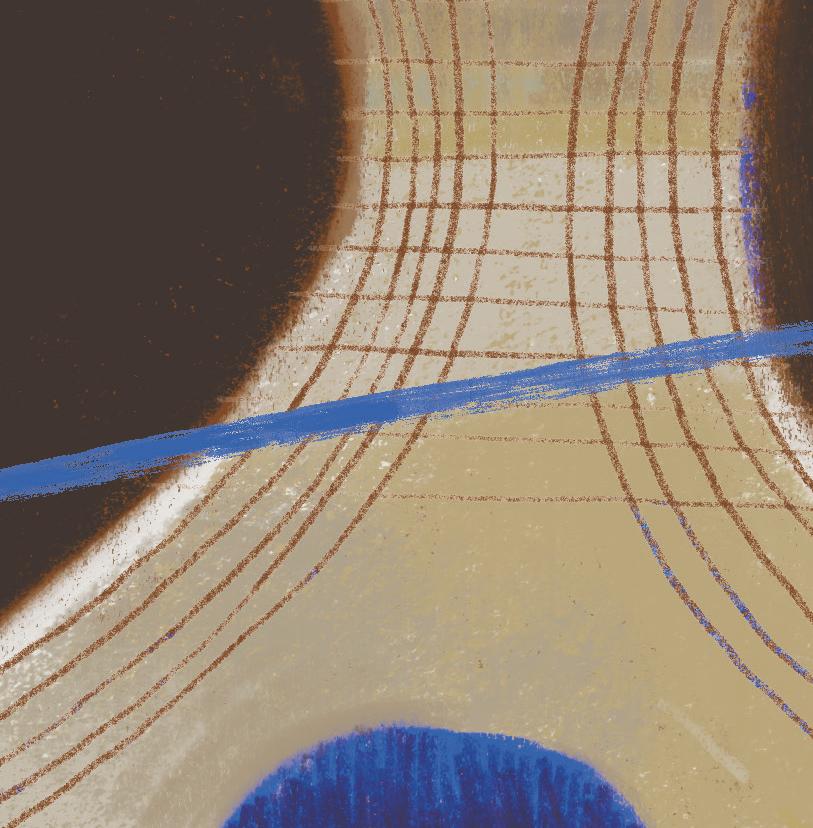

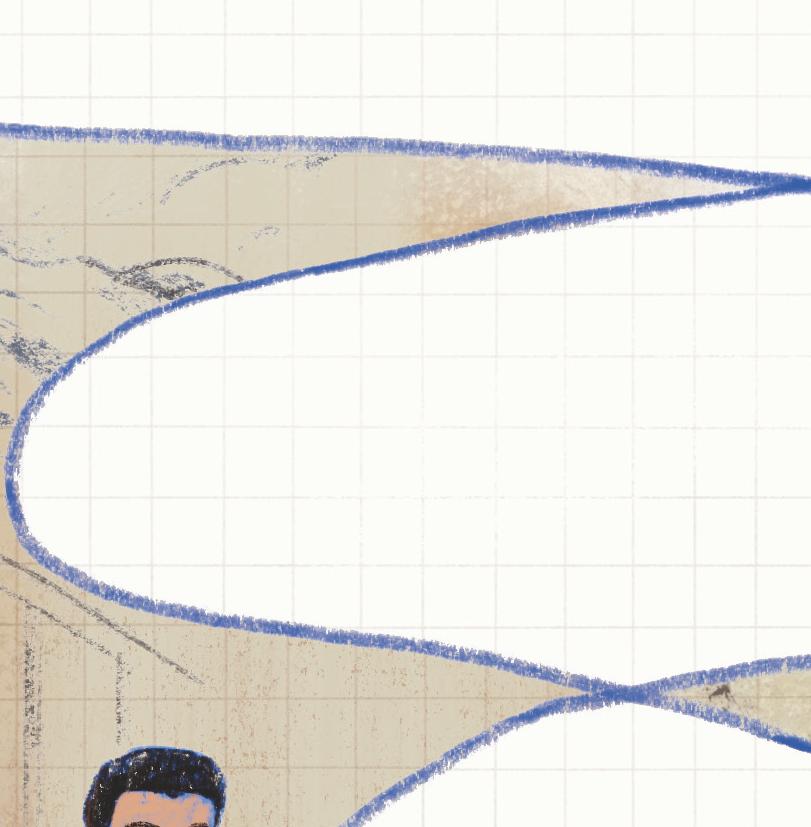

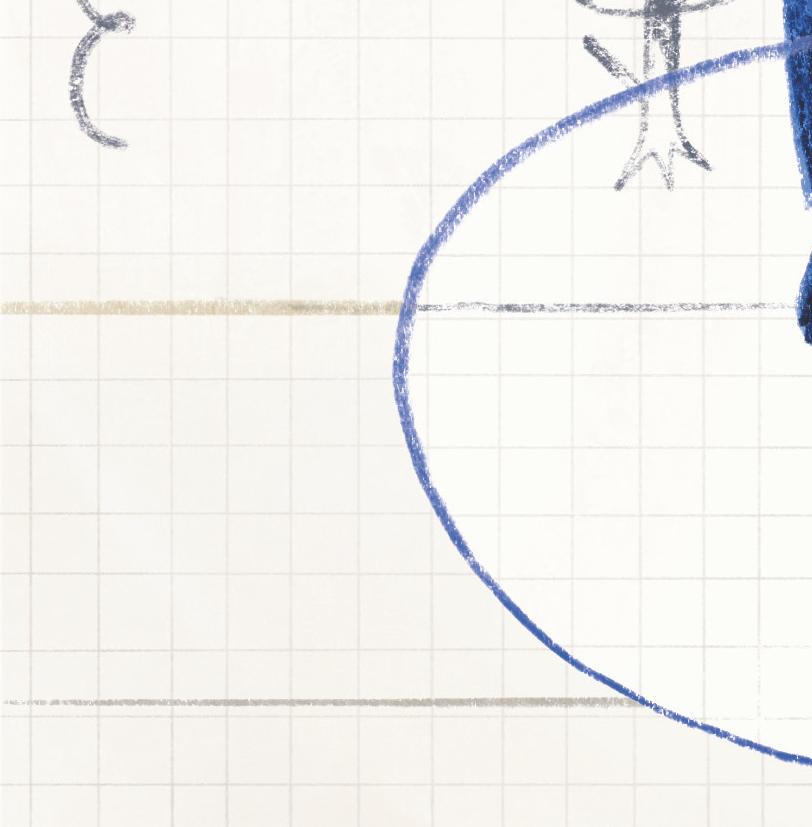

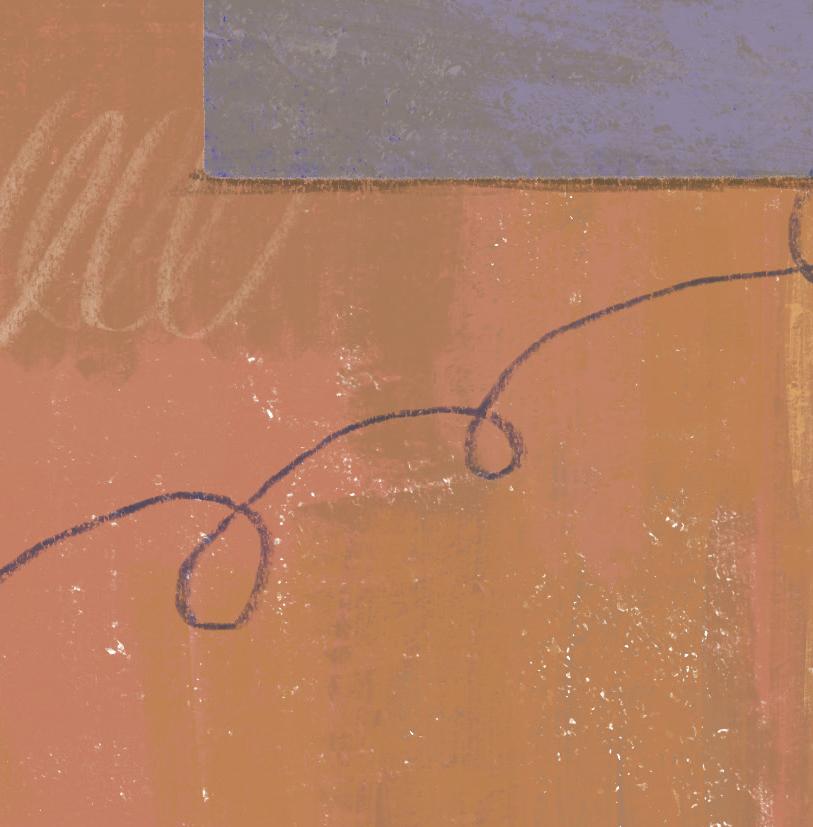

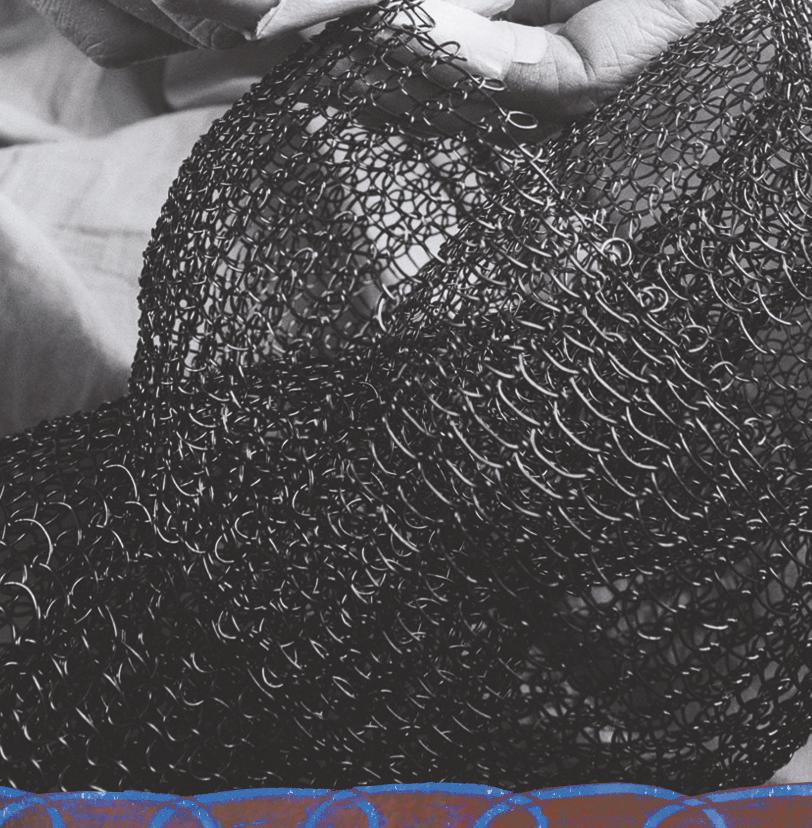

That same barbed wire would inspire Ruth’s art for decades as she grew into one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century. Throughout her career, she created enchanting twisting sculptures and curving shapes that connected, divided, and intersected.

Open this gorgeous biography to learn about the magnificent life of Ruth Asawa and her timeless contributions to the art world.

Caroline McAlister is the author of the picture books Finding Narnia and John Ronald’s Dragons . She writes stories that encourage children’s sense of wonder and inspire their creativity. She lives in Greensboro, North Carolina. carolinemcalisterauthor.com

Jamie Green is a freelance artist based in Chicago. They graduated from Ringling College of Art and Design with a BFA in illustration and have illustrated several books, including Mushroom Rain by Laura K. Zimmermann and Arden High: Twelfth Grade Night by Molly Horton Booth and Stephanie Kate Strohm. jamiegreenillustration.com

A division of Holtzbrinck Publishing Holdings Limited Partnership 120 Broadway, New York, NY 10271 • mackids.com

This digital copy has been distributed for promotional and review purposes only. No other uses are allowed, including but not limited to consumer viewing.

No sale or further distribution of this digital advance reader’s edition is permitted, except to others on your staff for review purposes only. Please do not post or share the link to this material. View and share it responsibly within your organization. We thank you for supporting the rights of our authors and artists in this endeavor.

For more information, contact childrens.publicity@macmillan.com.

• Outreach to Key Reviewers, Media, and School and Library Contacts

• Digital ARE Sent to Select Bloggers and Digital Influencers

• Included in MacKids Social Media Promotions

• Featured at Select School, Library, and Bookseller Conferences and Conventions

• Digital ARE Available on Edelweiss

Published by Roaring Brook Press

Roaring Brook Press is a division of Holtzbrinck Publishing Holdings Limited Partnership 120 Broadway, New York, NY 10271 • mackids.com

Text copyright © 2025 by Caroline McAlister. Illustrations copyright © 2025 by Jamie Green. All rights reserved.

Our books may be purchased in bulk for promotional, educational, or business use. Please contact your local bookseller or the Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at (800) 221-7945 ext. 5442 or by email at MacmillanSpecialMarkets@macmillan.com.

Library of Congress Control Number 2024010865

First edition, 2025

The illustrations in this book were created with charcoal, watercolor, and Procreate; the type was set in ITC Mendoza. The book was edited by Emily Feinberg and Emilia Sowersby, with art direction and design by Mina Chung. The editorial intern was Makena Cioni. The production editor was Hayley O’Brion, and the production was supervised by Celeste Cass. Printed in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd., Huizhou City, Guangdong Province.

ISBN 978-1-250-31037-8 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my good friends Lori and Calliope George, who went with me to Ruth’s exhibits and got as excited about this project as I did

C. M.

For Grandma Saiko

J. G.

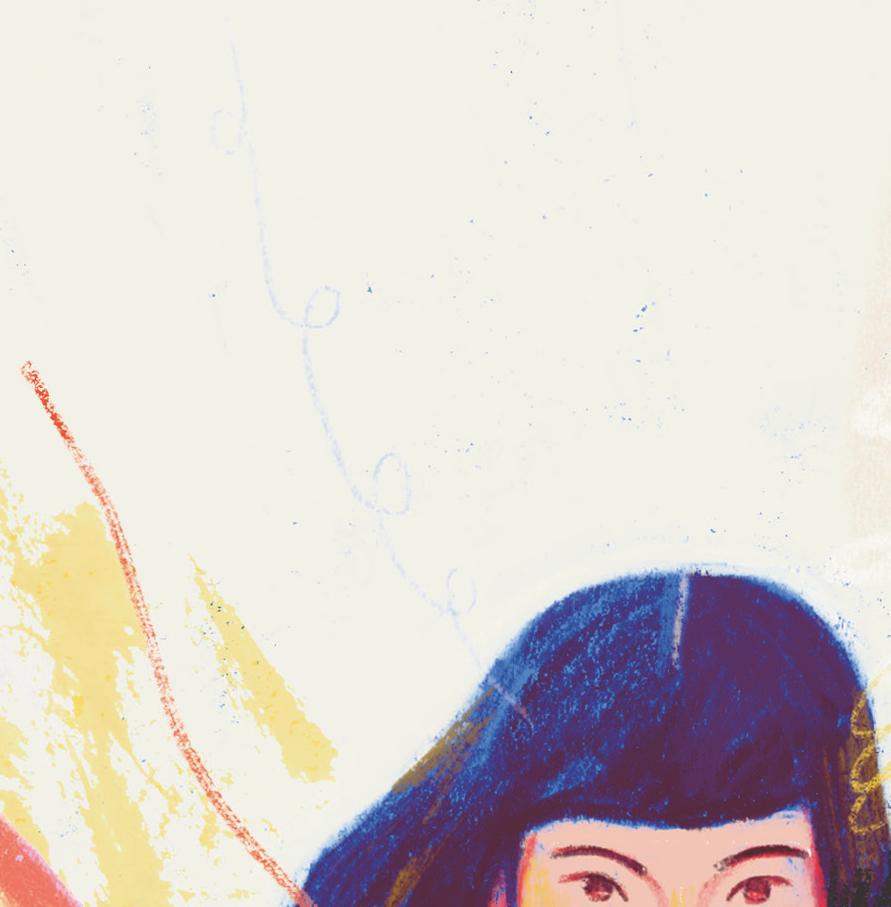

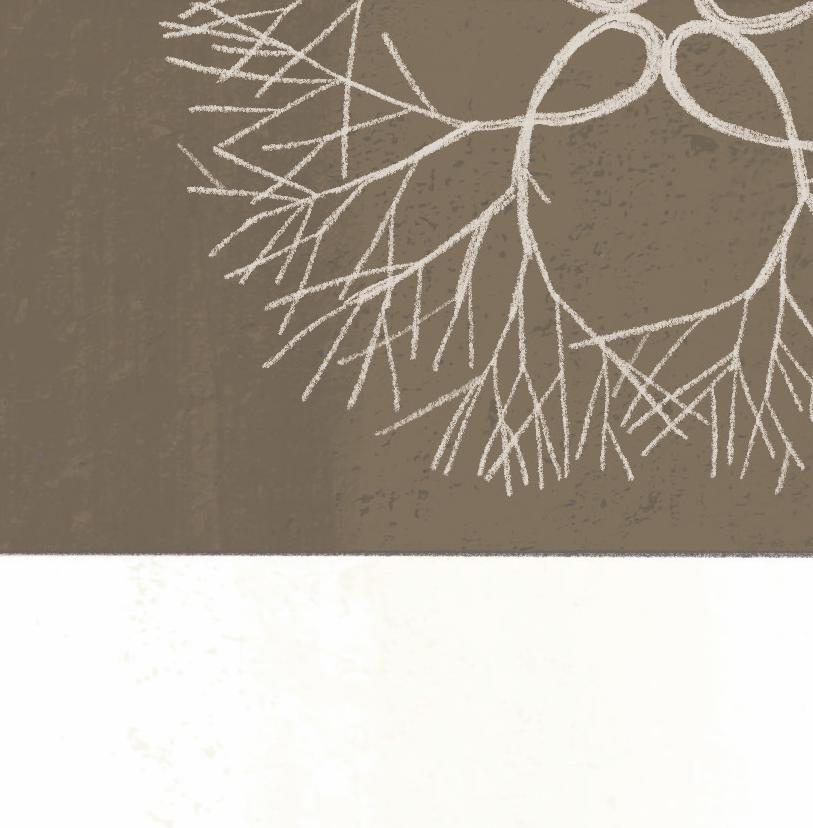

AIKO ASAWA drew her first lines in the dry California dirt.

She watched her lines narrow and widen.

They curved gently like the rounded hills to the east,

like the ocean waves to the west,

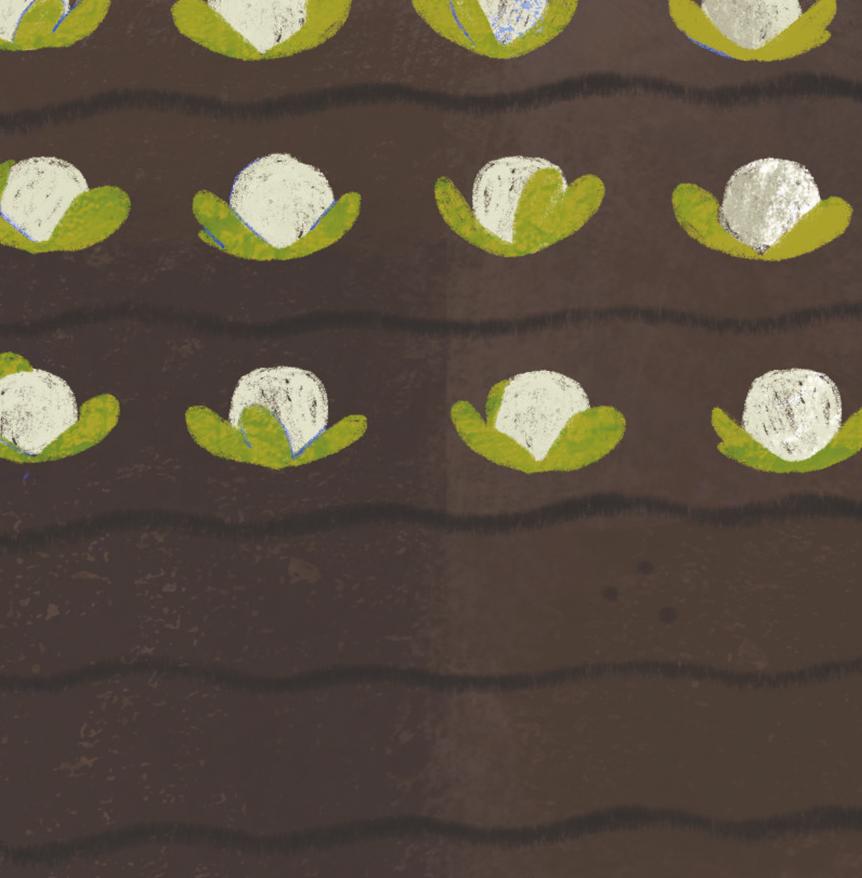

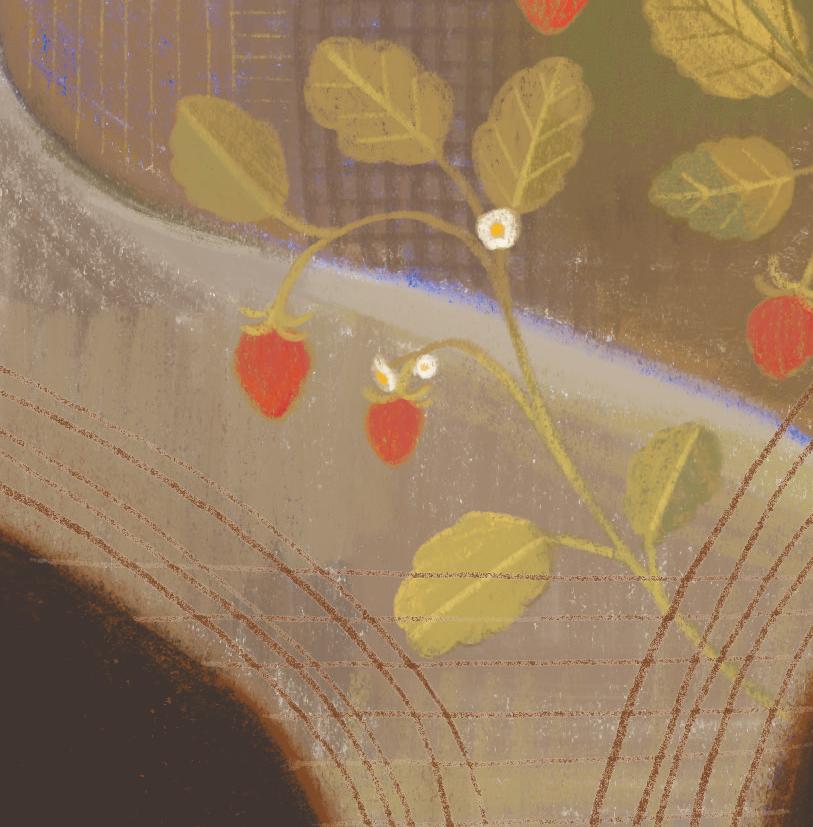

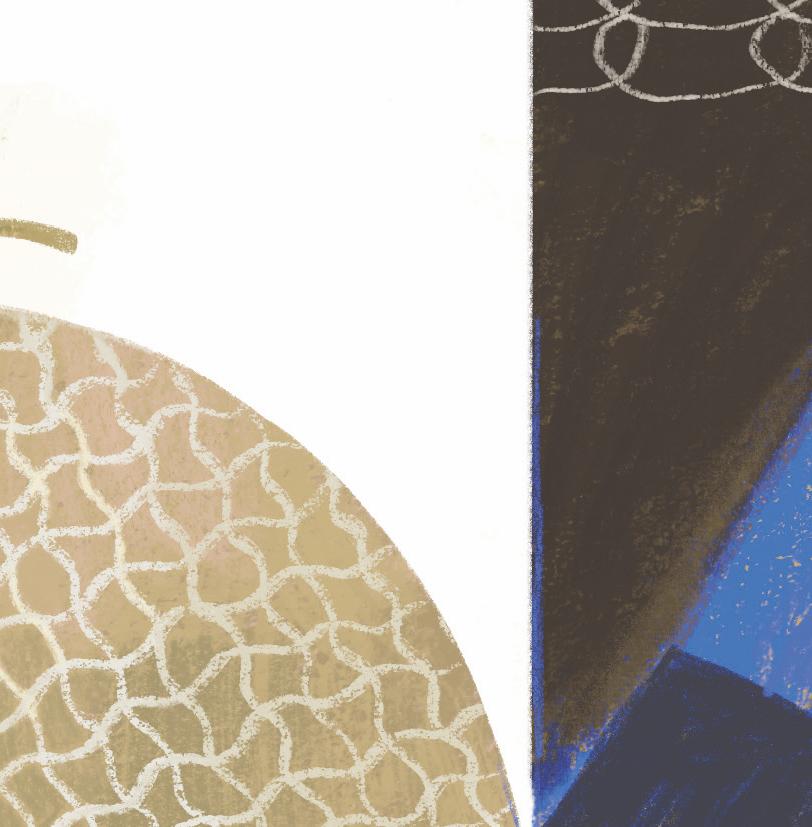

and like the fat melons and cabbages her family grew on their farm.

When the seven Asawa children lined up, Aiko was not the oldest, bossy and brash. She was not the baby, everyone’s darling.

She was number four, smack-dab in the messy middle.

All the children had chores.

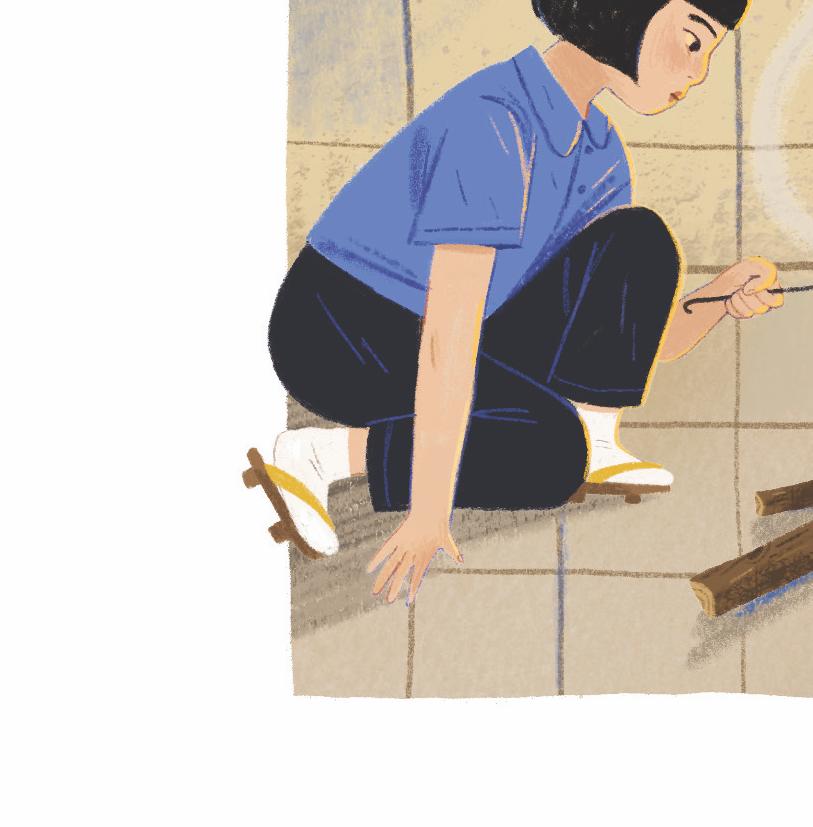

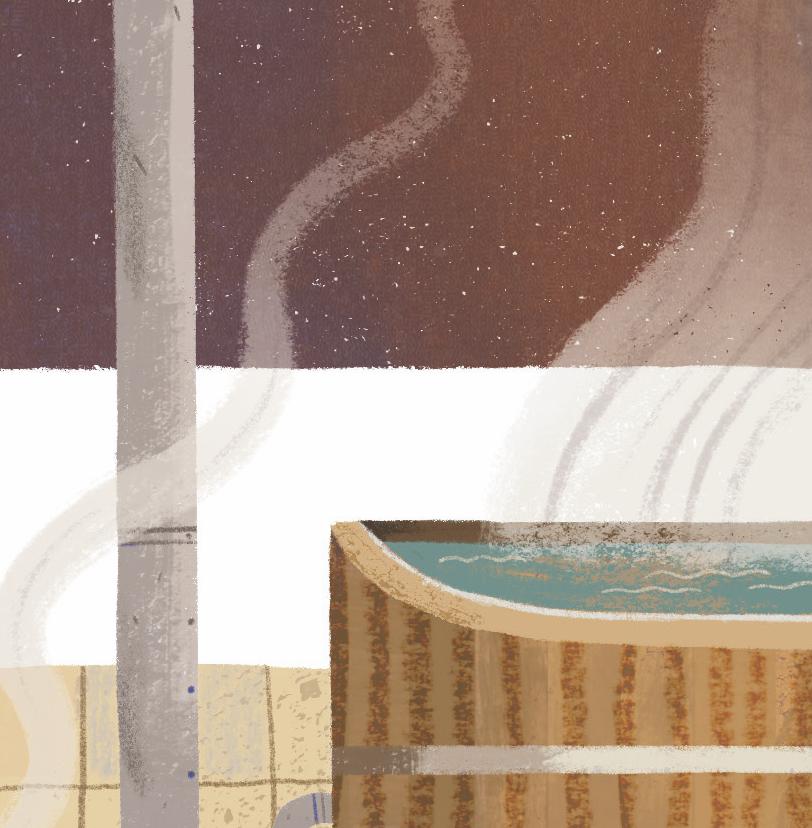

Aiko tended the fire that heated their ofuro, the family bath.

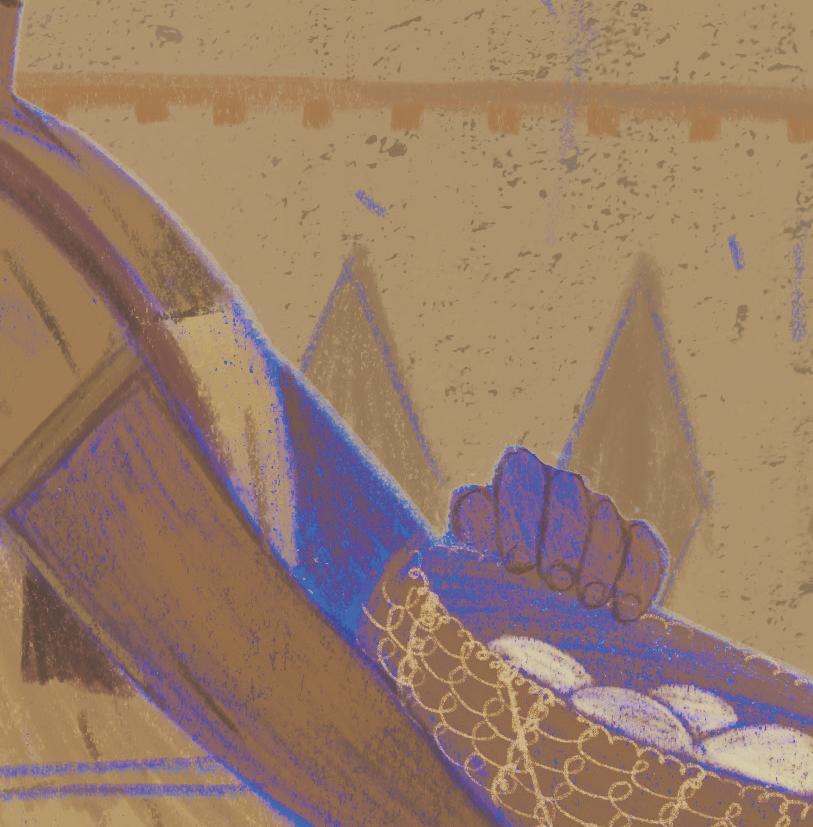

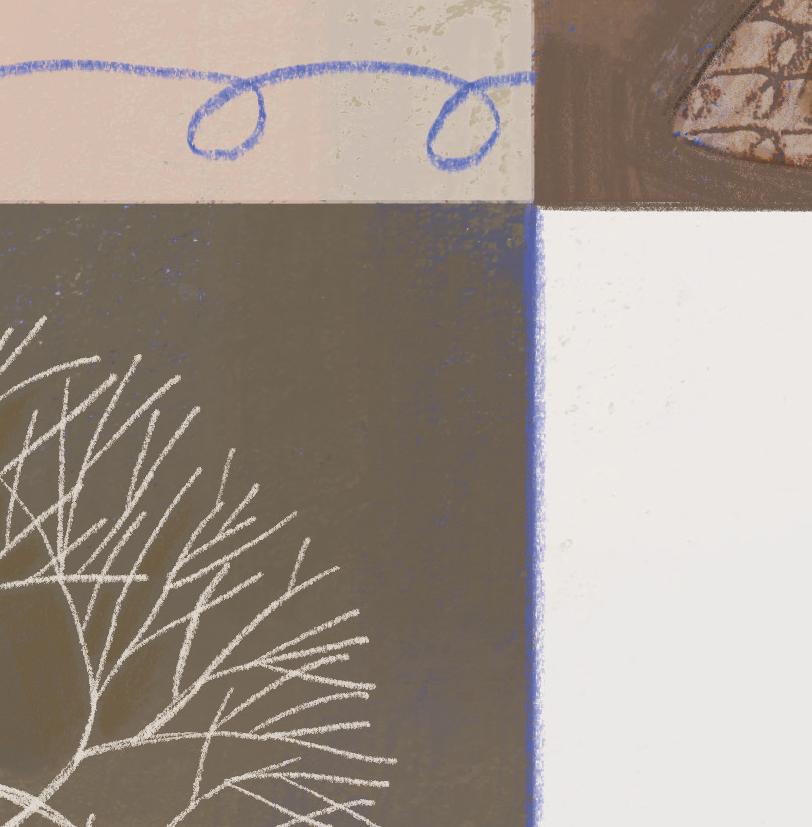

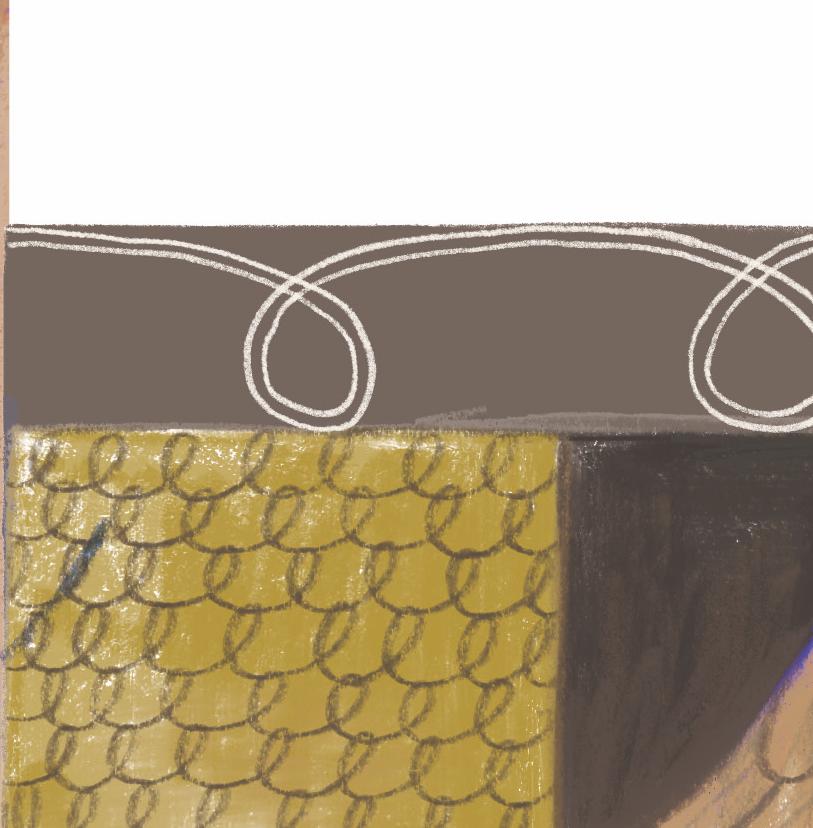

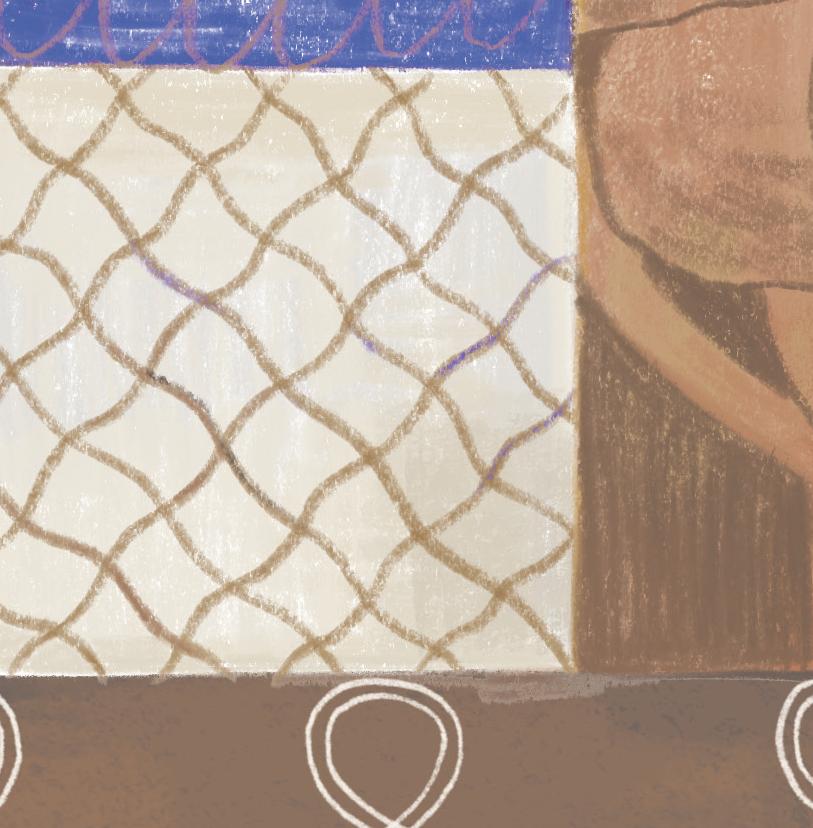

She also coiled string in, out, and around stakes to make trellises for the lima beans.

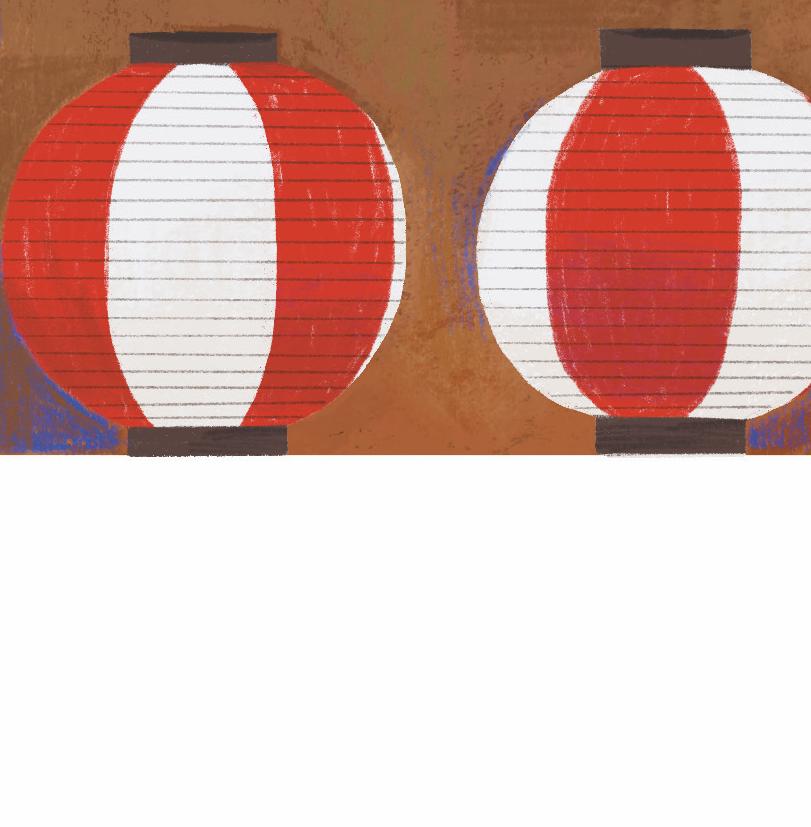

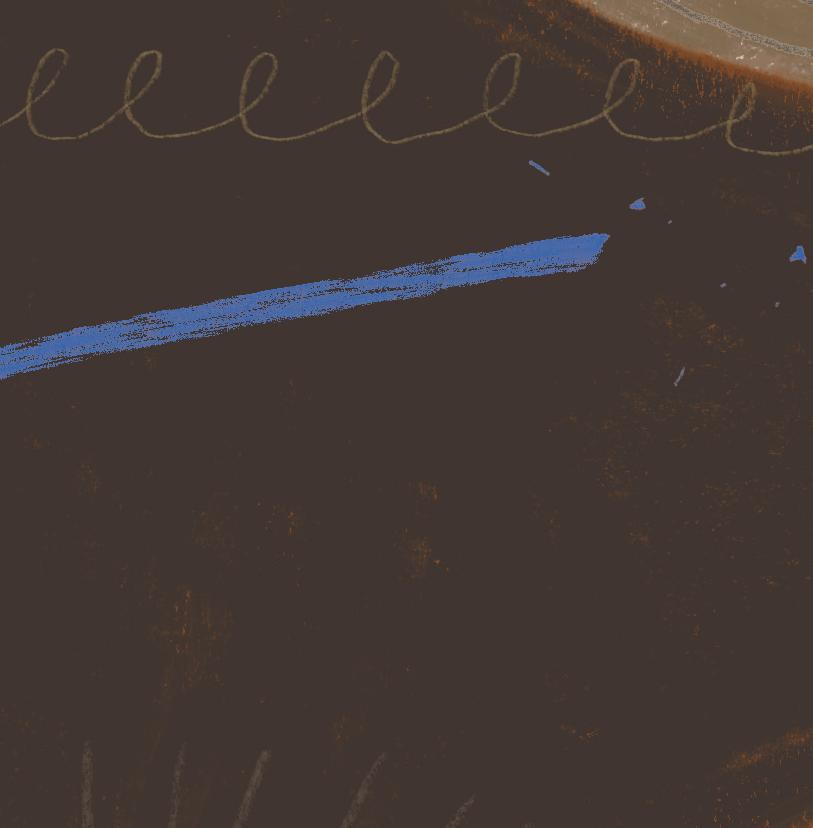

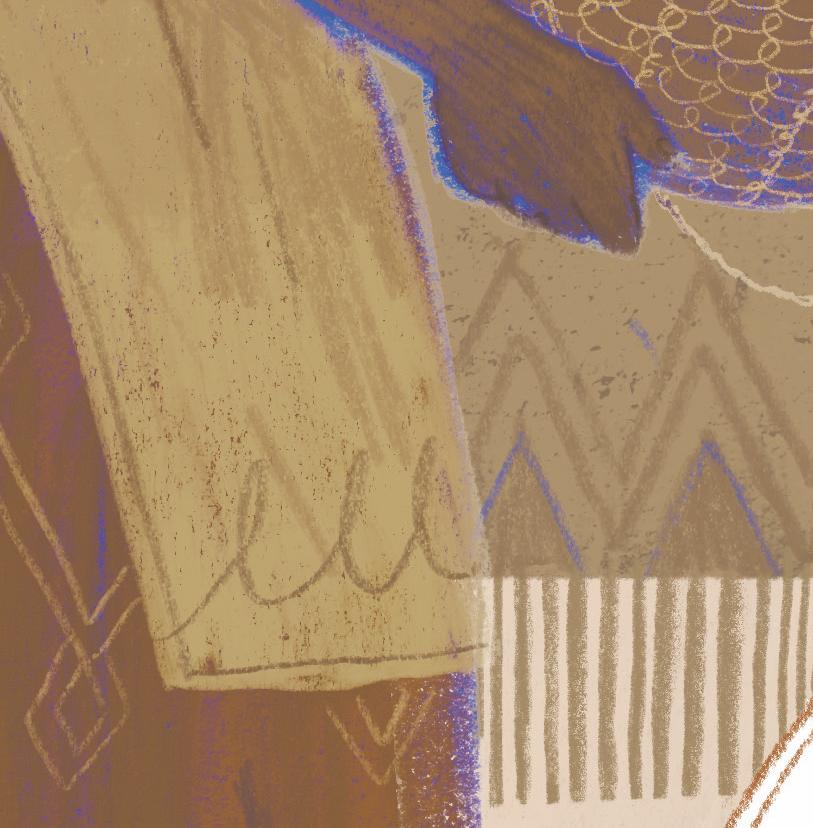

Saturdays at Japanese school, Aiko and her siblings traced arcs in the air with bamboo swords. In calligraphy lessons, they lifted their brushes up and brought them down in a rhythmic dance. Bold black lines stretched across white paper.

Aiko didn’t know she was making art when she collected labels from Campbell’s soup cans, when she wound wire used for bundling vegetables into bracelets, or when she copied the outlines of comics from old newspapers. Art was made by people who lived in big cities. It hung on walls in museums, not in a humble farmhouse with paper ceilings and a tin roof.

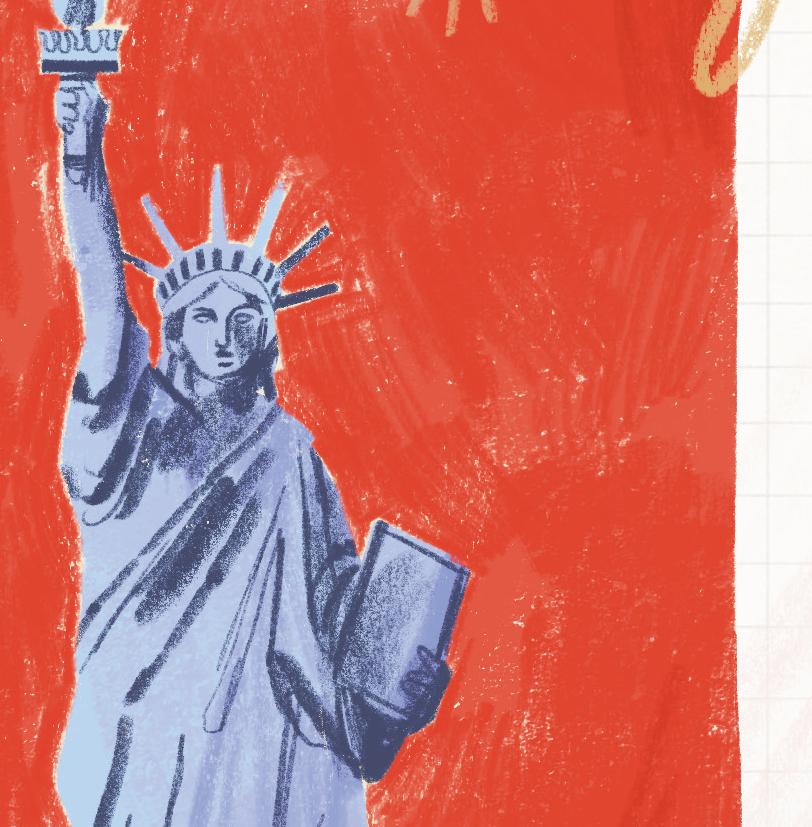

Weekdays at American school, the teachers called her Ruth. During morning assembly, she stood in line and pledged allegiance to the flag. She once won a prize for the poster she painted of the Statue of Liberty, torch held high. Her parents were so proud.

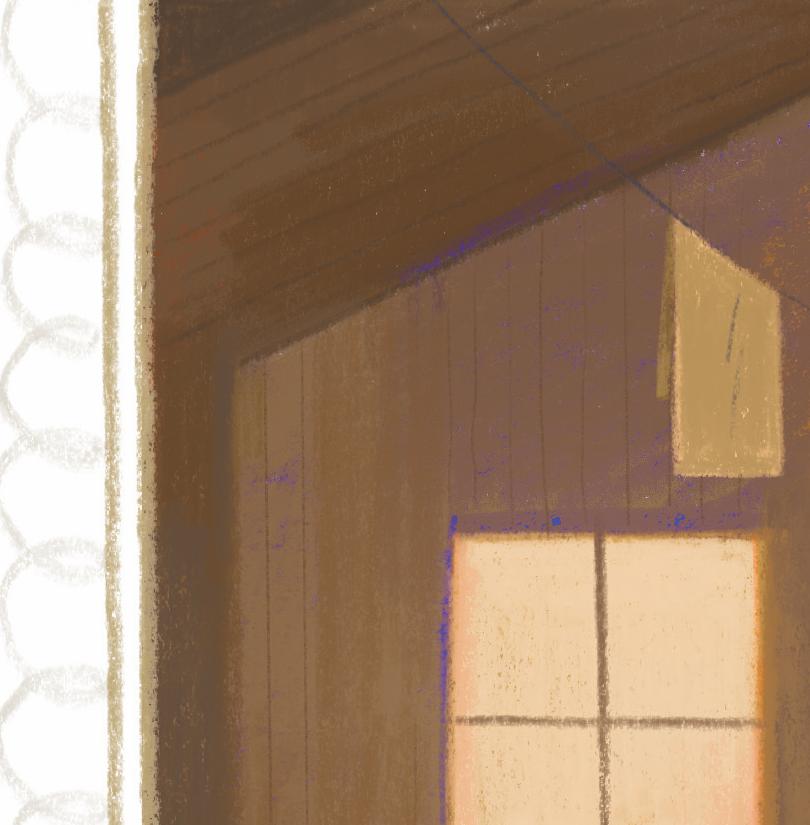

But an invisible line divided Ruth’s two worlds. At home and at Japanese school, she ate miso soup and pickled vegetables. She took off her shoes inside and put on surippa. She said “onegaishimasu” and “arigatou.”

At American school, her classmates shared hot dogs and cupcakes. She kept her shoes on, even though they tracked dirt inside.

She said “please” and “thank you.”

The invisible line was always there, but she could cross back and forth or even straddle it if she had to.

That is, until the war started.

It was a Sunday, and the family was in the field picking vegetables for the Monday market. A friend with a radio heard the terrible news first:

Suddenly, the invisible line became a wall. She and her family had to choose a side.

Ruth tried to make Aiko disappear.

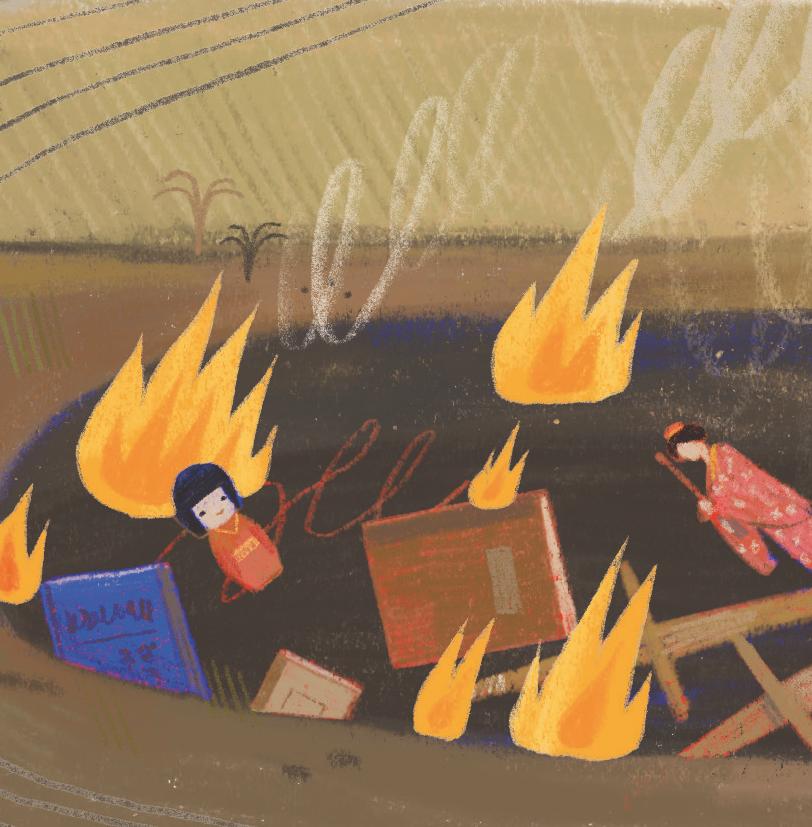

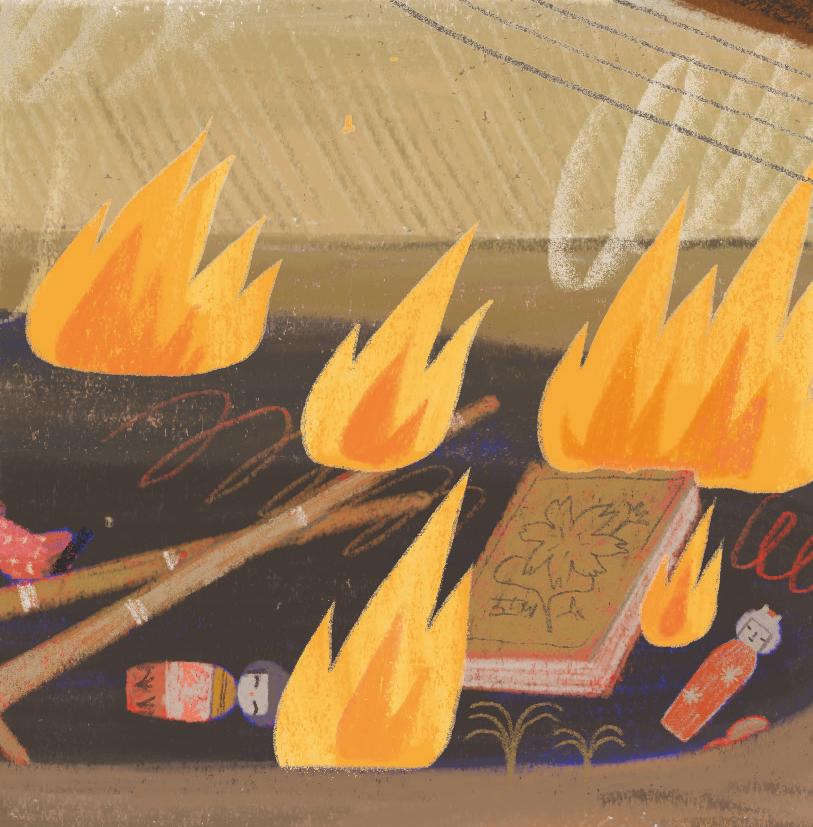

Her father tried to hide his ties to Japan. Behind the house, he built a bonfire and burned the bamboo kendo swords, the dolls in kimonos, and the books about tea ceremonies and flower arrangements.

As the fire crackled, Ruth felt the lines that connected her to aunts, uncles, and grandparents in Japan snap and break.

The government came for her father anyway. Ruth watched him disappear around a bend in the dirt road. She would not see him again for six years. Another line snapped.

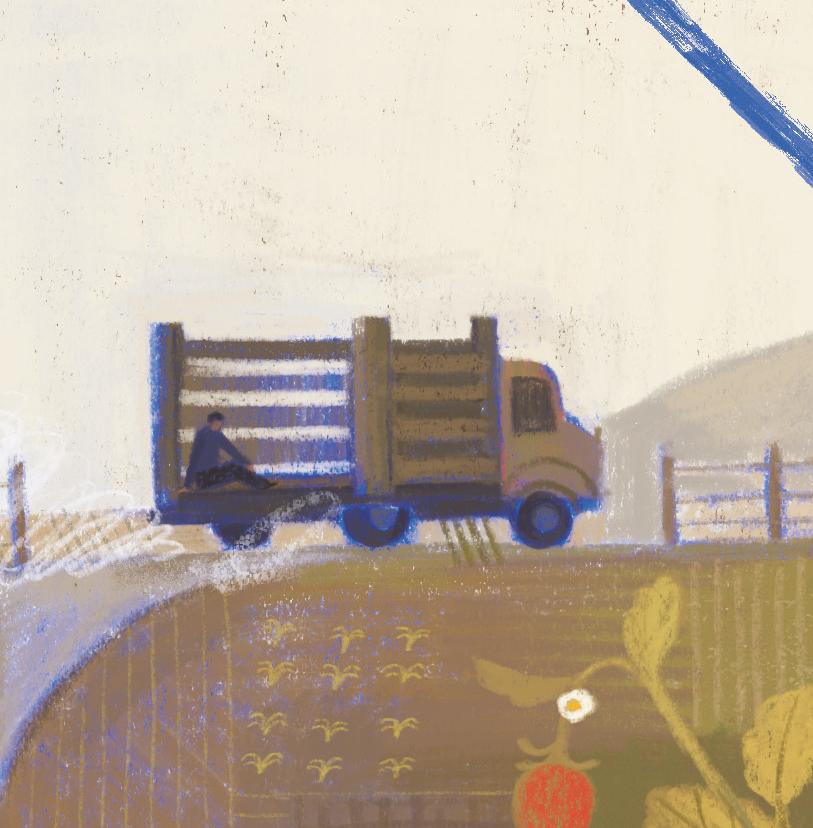

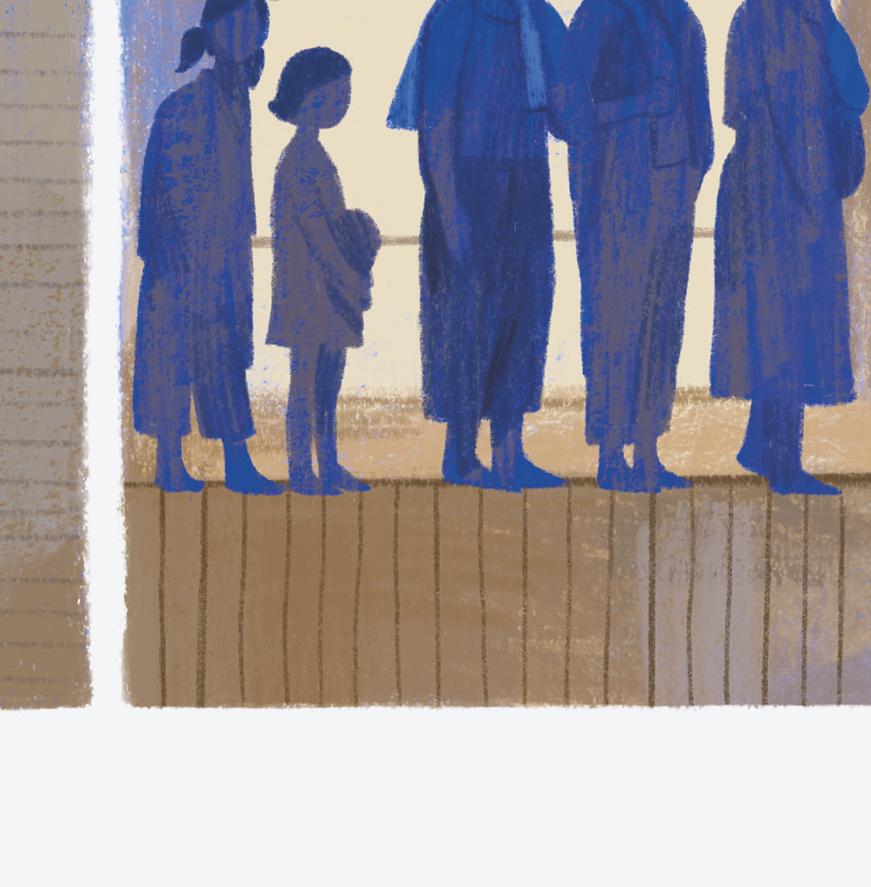

Two months later, Ruth, her mother, and her brothers and sisters followed government orders and drove to a racetrack. They were allowed to bring only what they could carry.

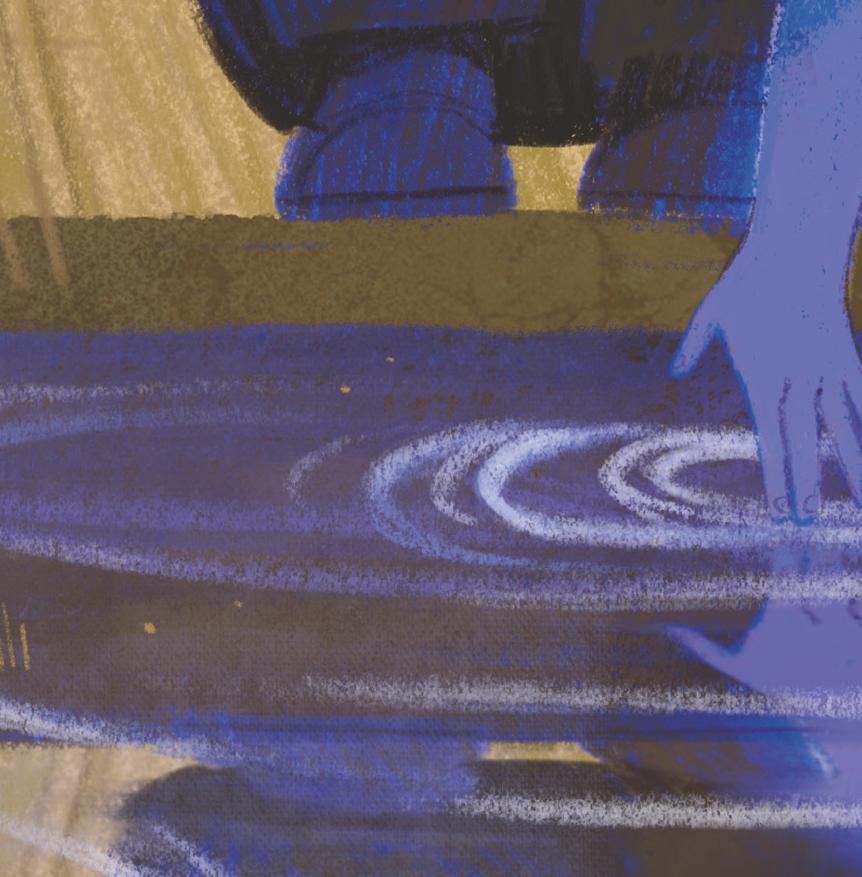

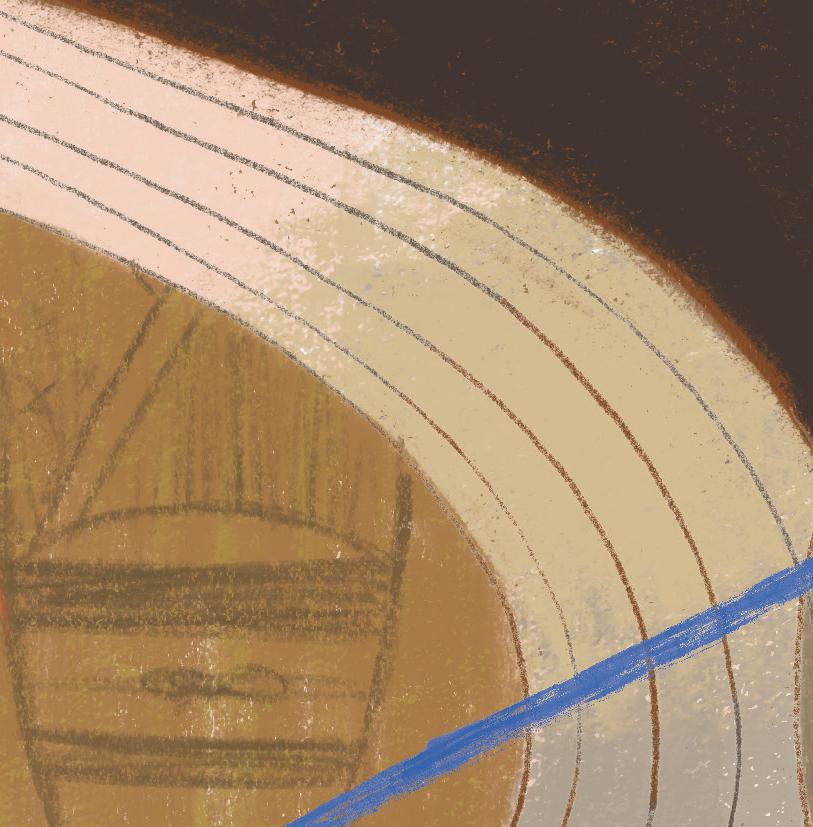

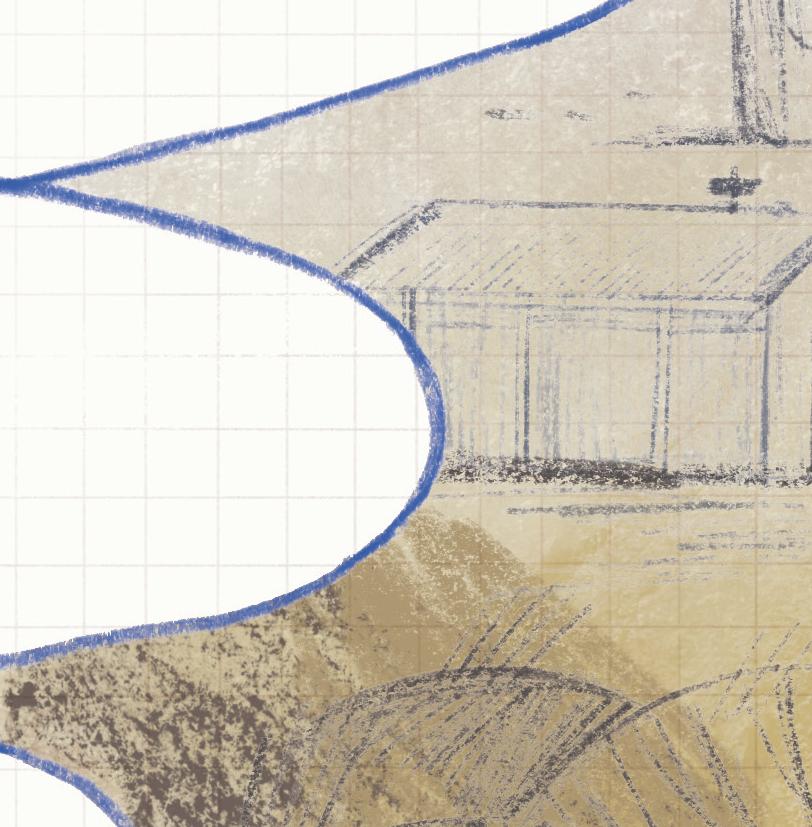

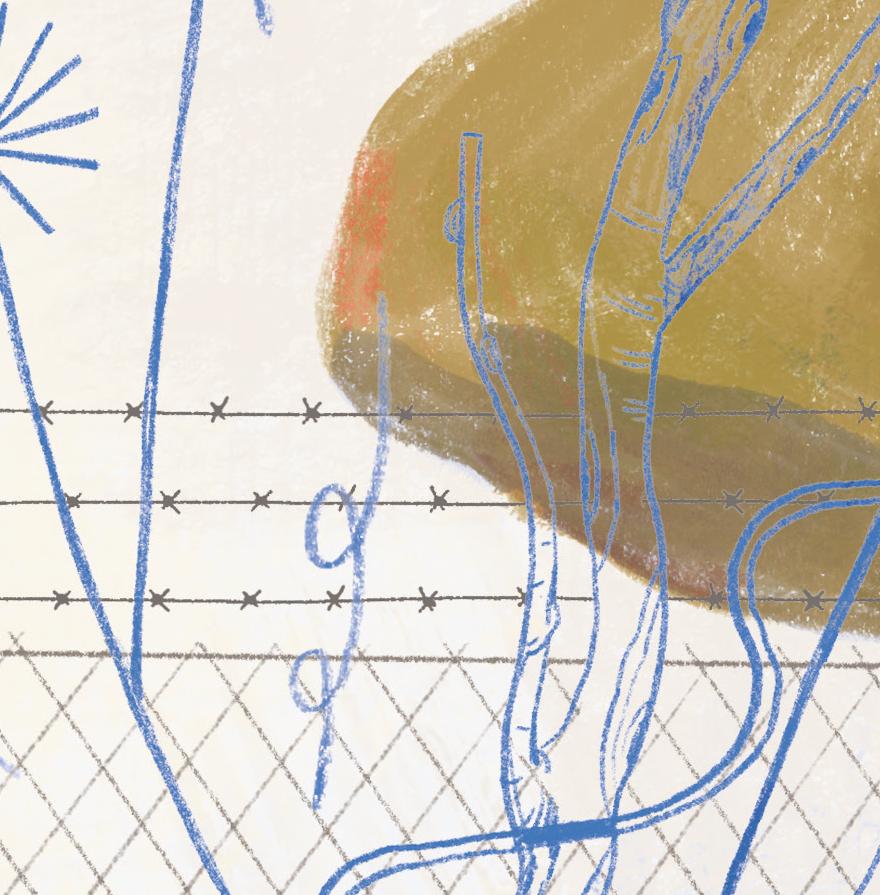

The whole family crowded into two horse stalls. Ruth ran her fingers over the lines of horsehair under the new paint. She smelled the manure beneath the thin linoleum.

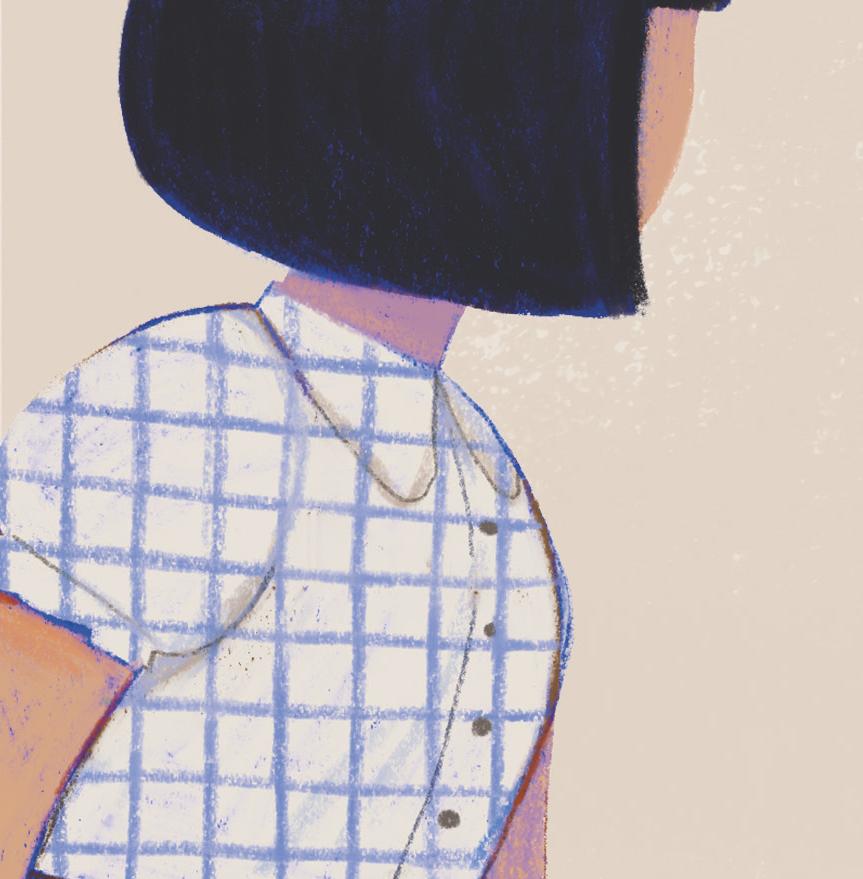

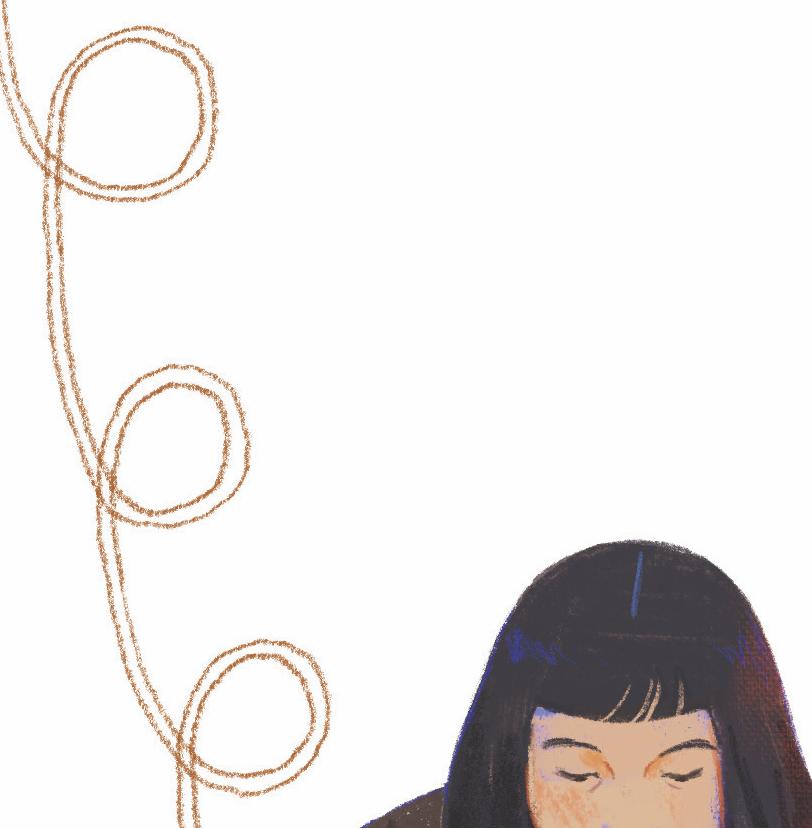

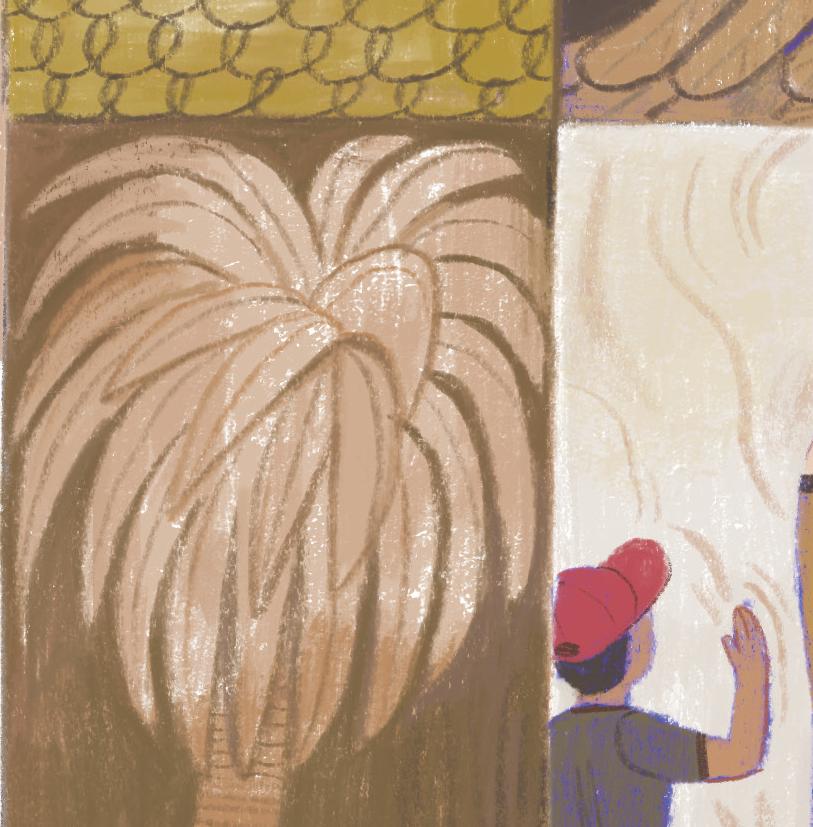

But in the bleachers outside, she met new people. Among those rounded up and imprisoned were talented artists, men who made Dumbo’s ears flap and Bambi’s tail twitch for Walt Disney’s movies. They showed Ruth how to draw what she saw: her friends’ faces, the racetrack, the horse stalls.

With charcoal and a pencil stub,

Ruth gave shape to her new world.

As summer turned to fall, a train took the family to a more permanent prison. Ruth peeked through the closed blinds. She saw the Colorado River winding like a ribbon beneath the full moon. California disappeared in the darkness as they rumbled toward the center of the country.

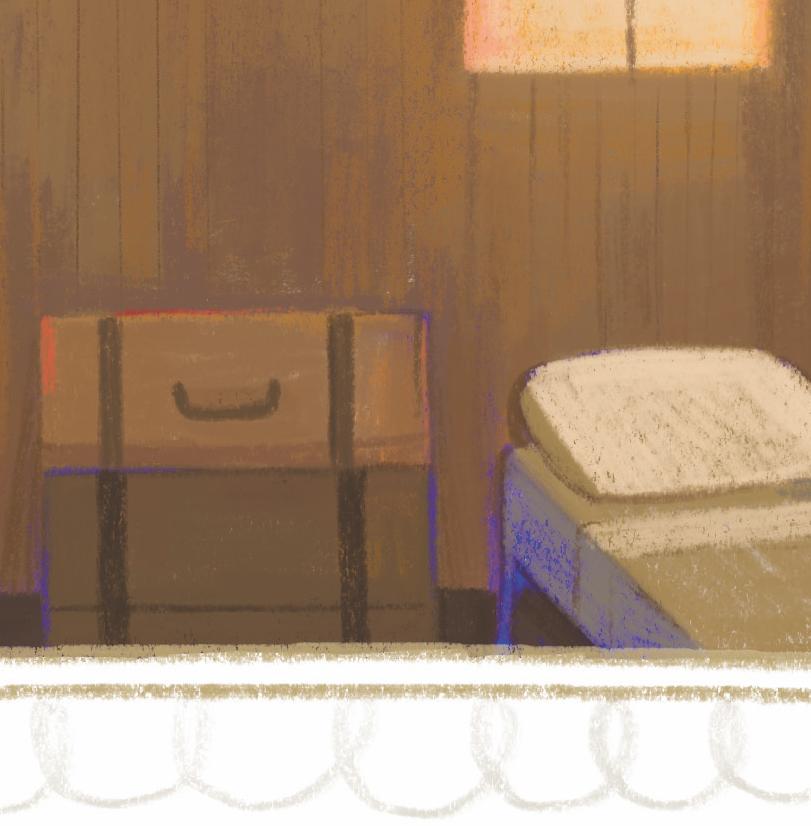

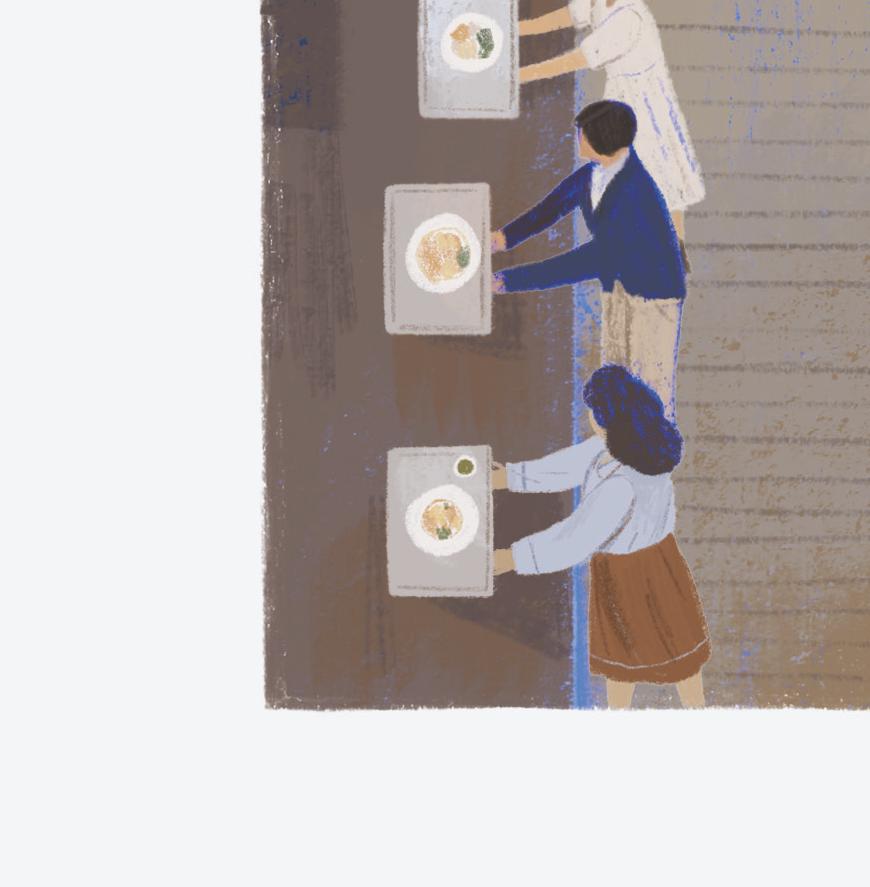

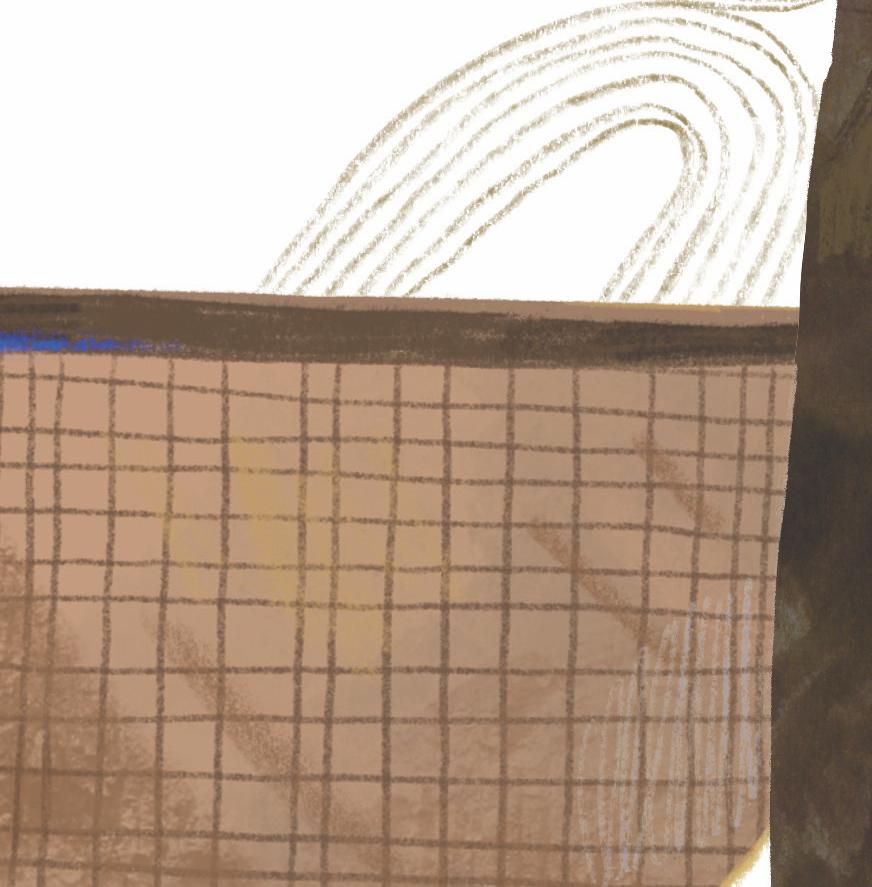

The Rohwer Relocation Center in Arkansas was more crowded than the racetrack. Ruth waited in line for meals. She waited in line to wash without the comfort or privacy of the family ofuro. While she waited, she looked.

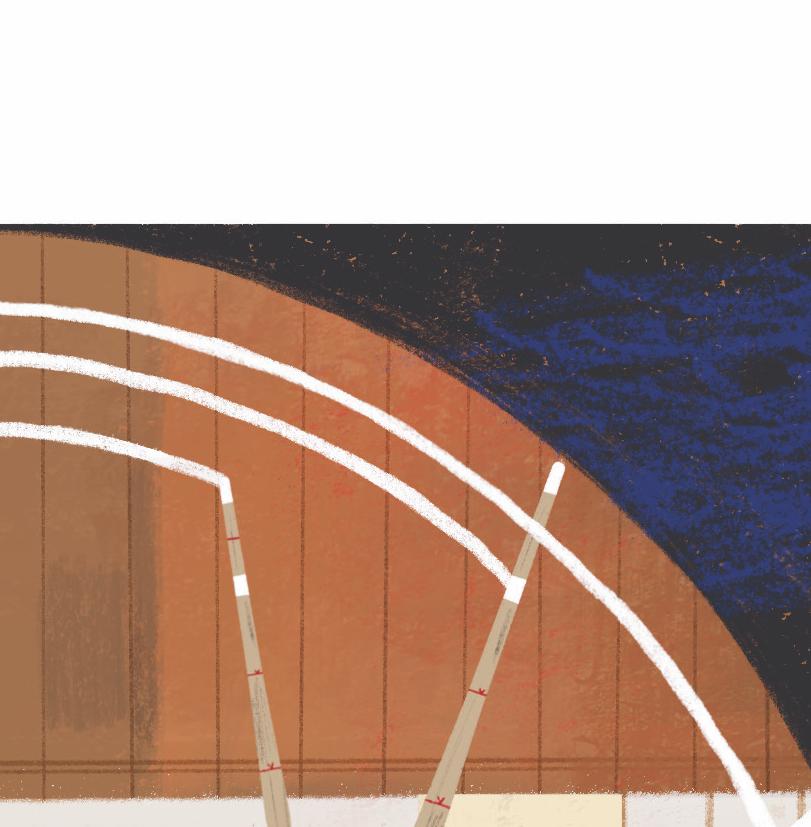

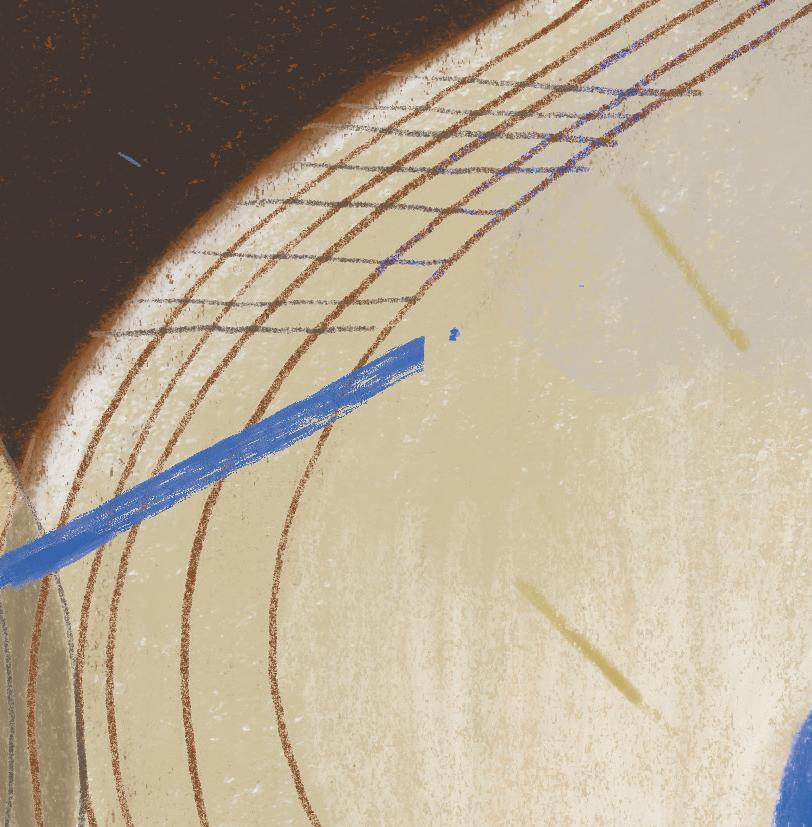

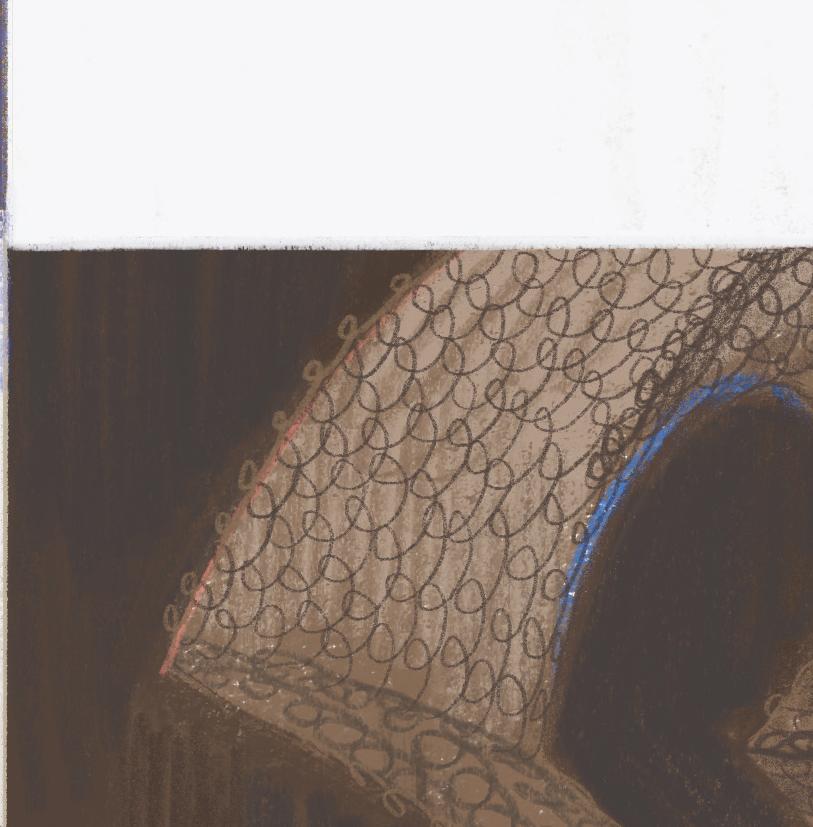

Barbed wire and guard towers surrounded her. Ruth sketched the low lines of the bayous, the knots and whorls of cypress knees, and the ramshackle fishing shacks beyond the fences.

At the camp school, the students put their hands on their hearts and pledged allegiance to the flag. When they got to “with liberty and justice for all,” they shouted,

In both camps, Ruth wrote line after line to officials in Washington, asking them to reunite her father with the family. But the officials were slow to respond. Her father missed her high school graduation.

When she was seventeen, Ruth seized an opportunity to leave Rohwer and attend college. She planned to be an art teacher. She studied for three years, but to get her degree, she needed to spend her last year practice-teaching. But because she looked like the enemy, her college wouldn’t place her at a school. They said they were protecting her; instead, they were protecting people’s prejudices.

Ruth left college without a diploma or a job.

Her path would not be a straight line.

She was now twenty years old. The war was over. She followed friends to an experimental liberal arts college in North Carolina. There, no one cared where she came from or what she looked like. They cared only about the art she made.

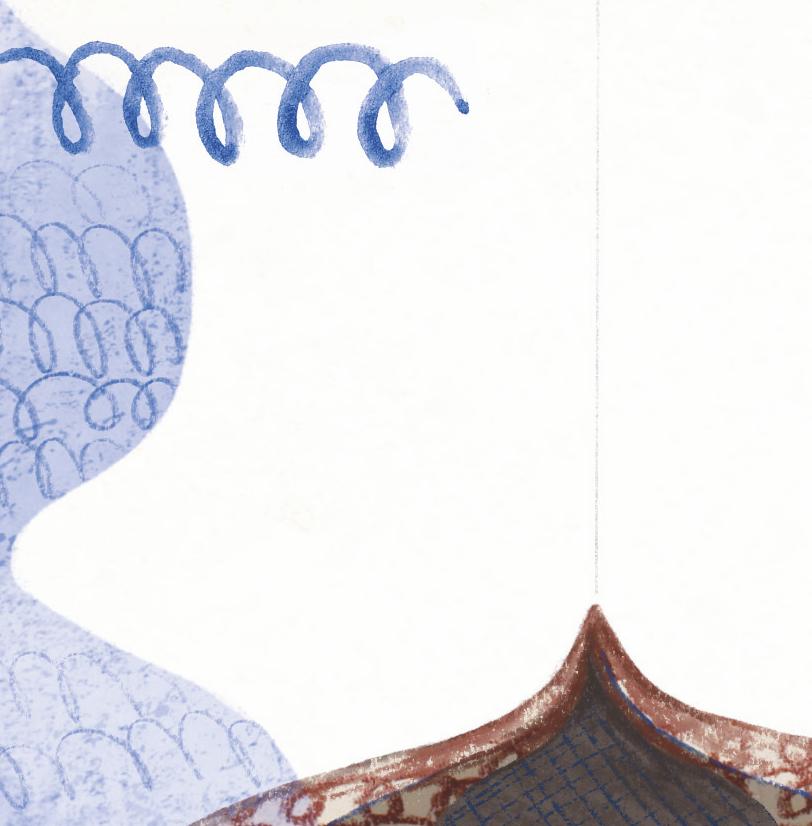

Surrounded by the curving outlines of the Blue Ridge Mountains, Ruth painted; she stamped, she sang, she danced. She drew meandering lines.

Her teacher, a strict German, disapproved of her messy studio. But he, too, had been displaced by the war. He taught the students to make art with whatever they could find—leaves, hardware, knickknacks. Ruth was already an expert at this. She pasted dogwood leaves onto paper so they leaped across the page. She printed patterns with potatoes and apples. He approved of her hard work.

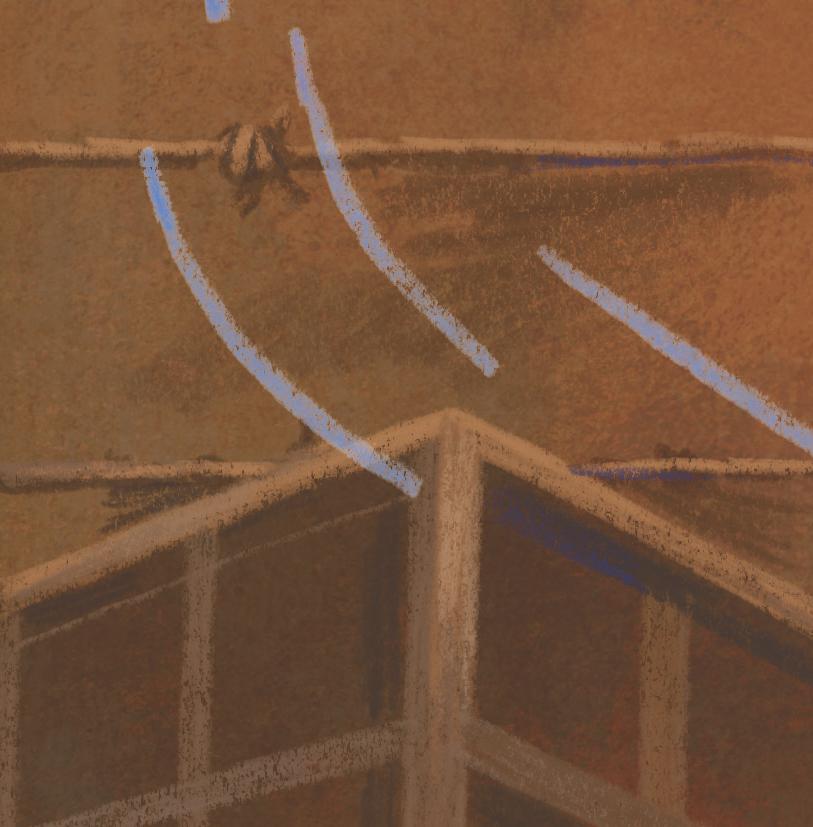

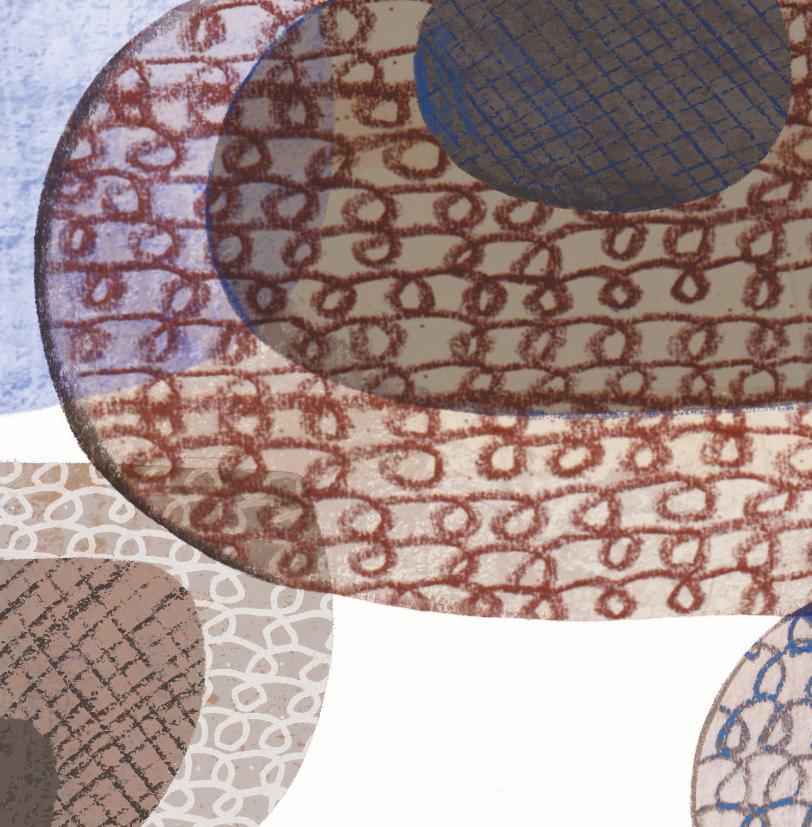

Then on a summer trip to Mexico, Ruth watched women carry eggs in woven wire baskets. She liked that the baskets were sturdy, strong, and practical, but also beautiful, patterned, and transparent. This was art made by ordinary people, used in their everyday lives. It didn’t hang on museum walls.

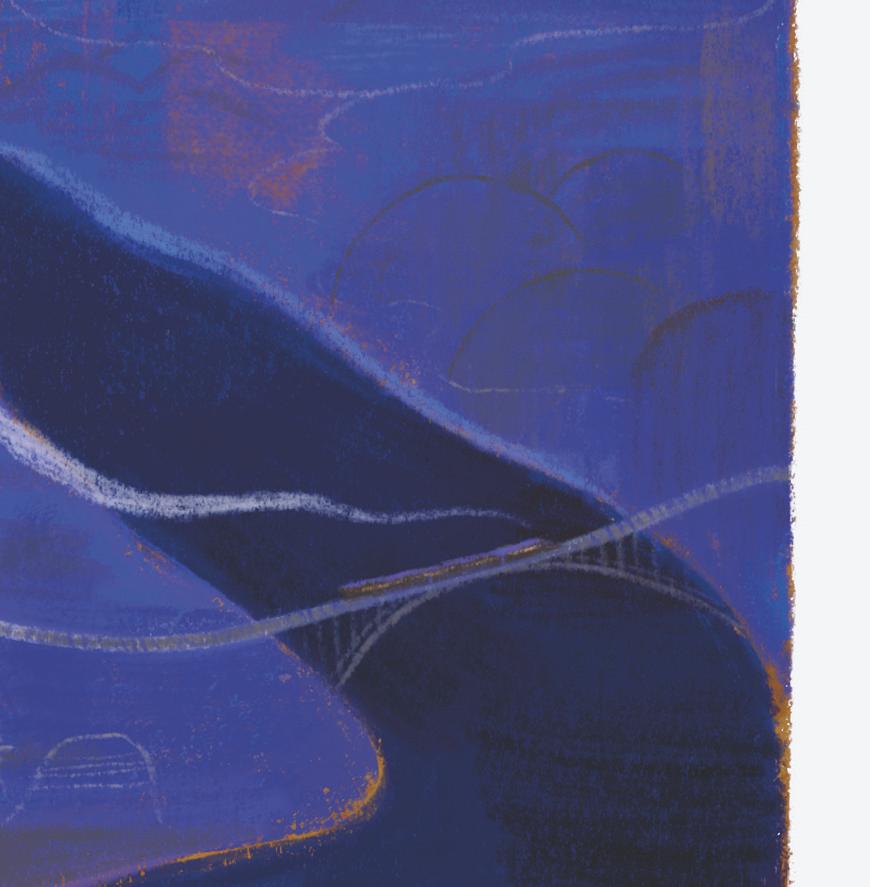

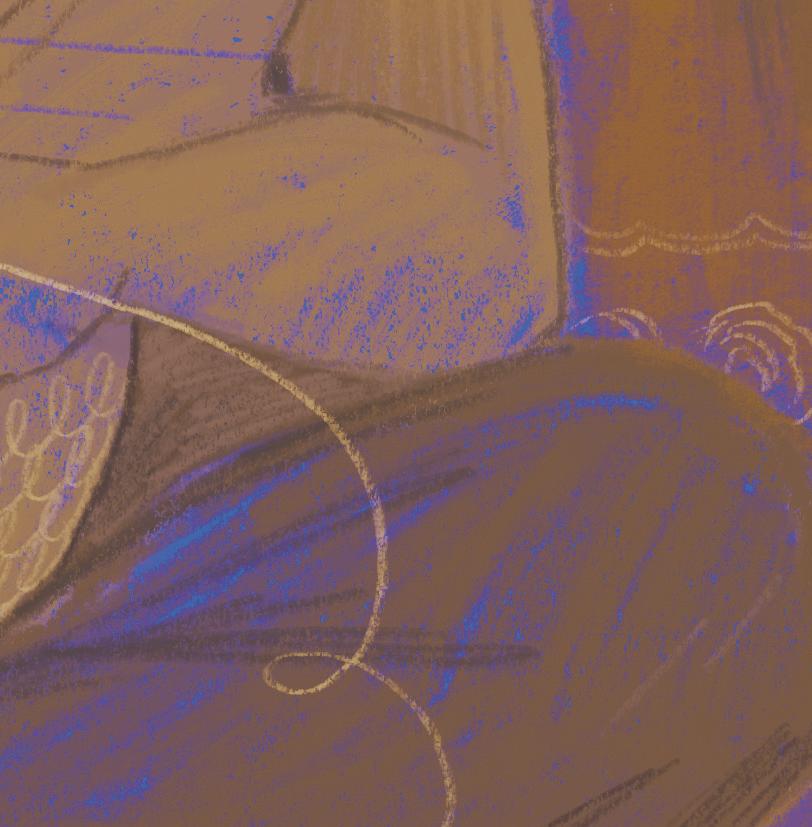

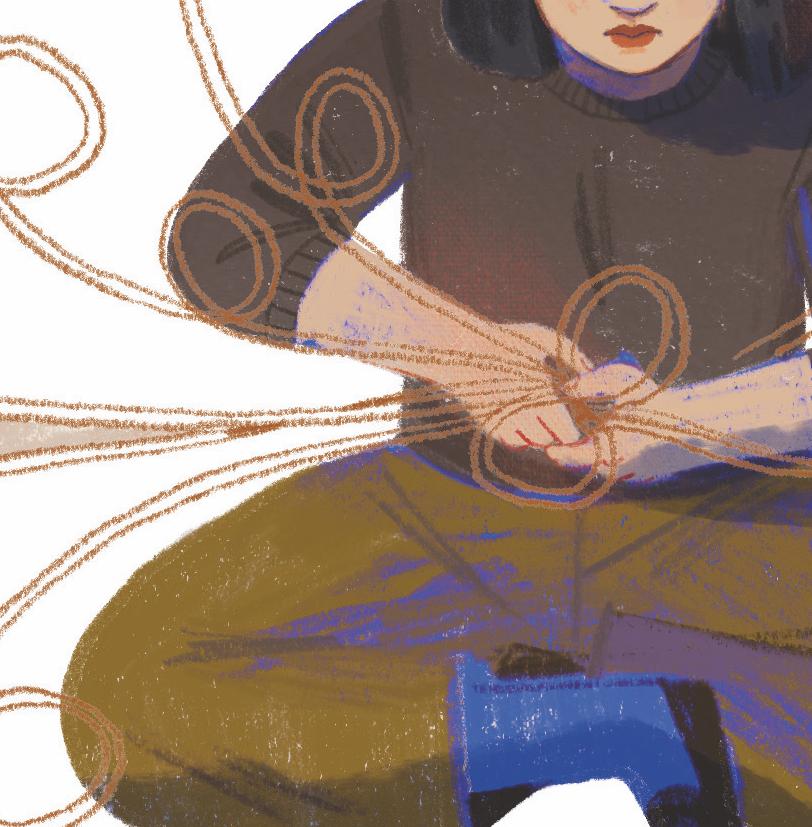

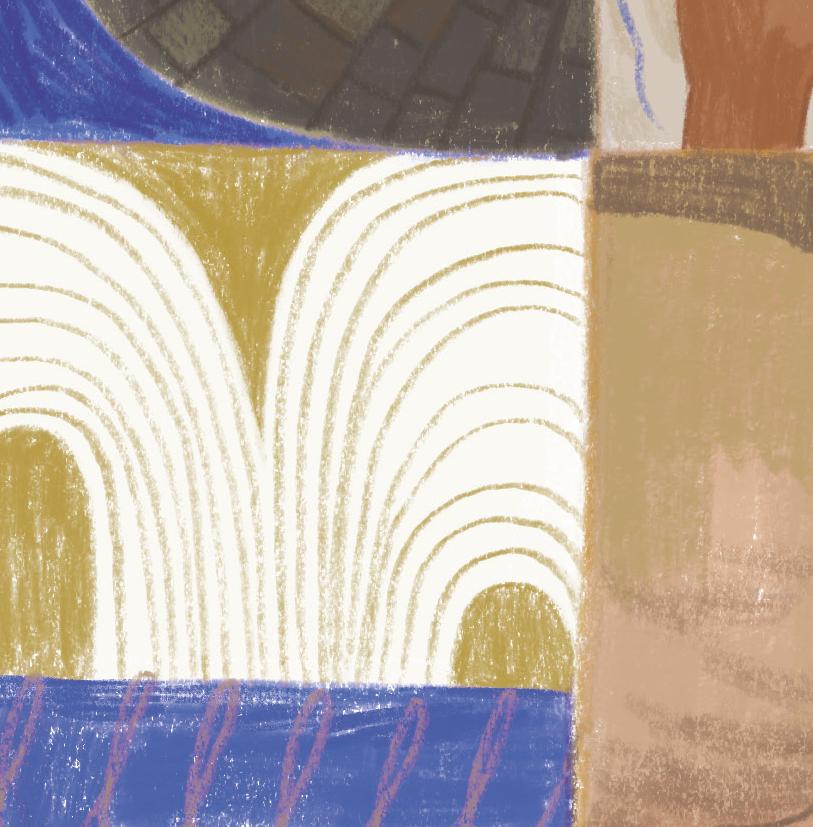

She thought back to the barbed wire that had kept her imprisoned at the Arkansas camp. Now as the world moved on from war, she found freedom in twisting wire into cells that divided and multiplied. A single strand of ordinary wire became a continuous piece with no beginning or end. She demonstrated that a line could go anywhere, be anything. A line could stretch into infinity.

Sometimes her sculptures looked like a dancer’s arms held in an arc. Sometimes they resembled the outlines of the Blue Ridge. And sometimes they looked like the winding tendrils and roots of the vegetables her family had grown back in California.

Finally released from the camps, Ruth’s family returned to farming. They had to start over, all living in one crowded room, but at least they were together—father, mother, and the three youngest children.

Ruth took time away from art school to help with the fall chores. She pickled and canned; she bundled flowers to sell.

When Ruth fell in love, she added lines to her life that twisted in new directions. She wanted to create a big family, like the one she had grown up in, but she also wanted to continue making art.

Teachers and friends told her she would have to choose. But Ruth didn’t. She zigged and she zagged.

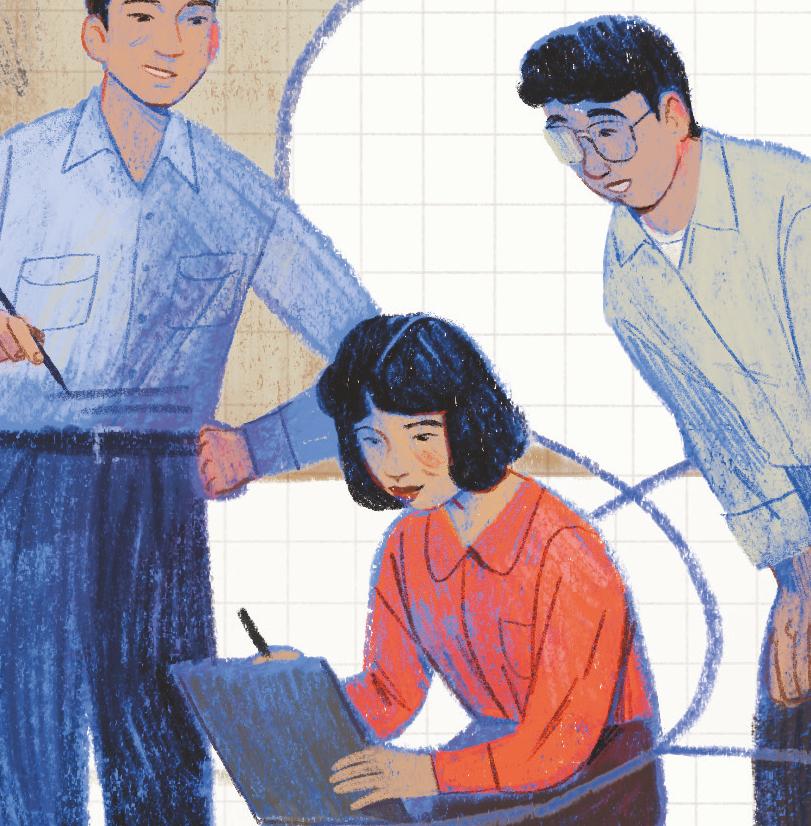

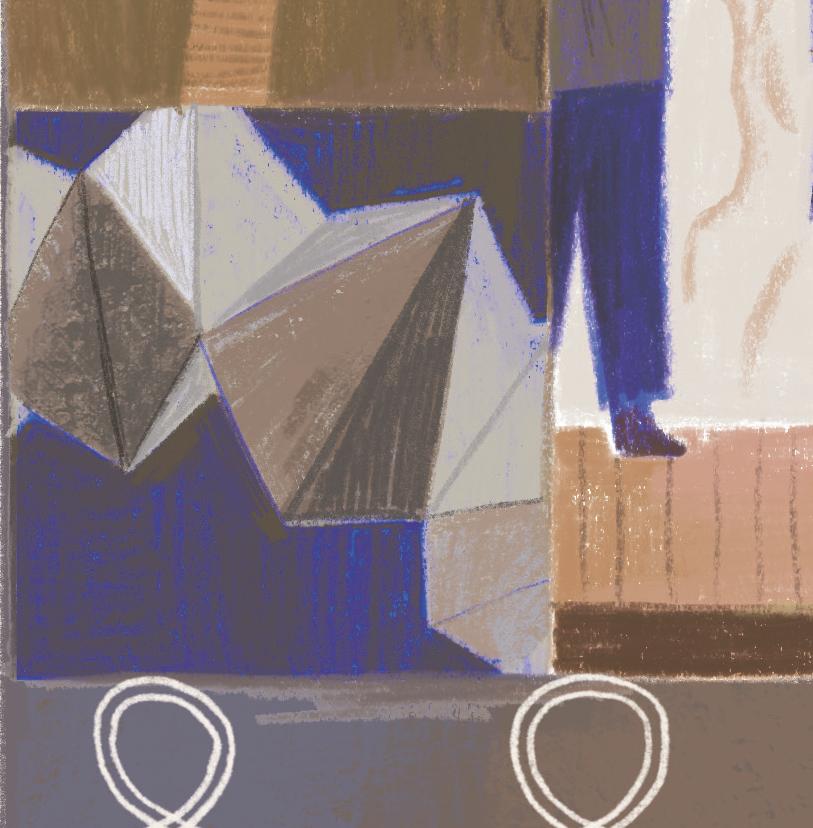

While her babies slept, Ruth looped wire into patterns of intersecting lines. Her six children learned to walk and play among the dancing shadows cast by her sculptures.

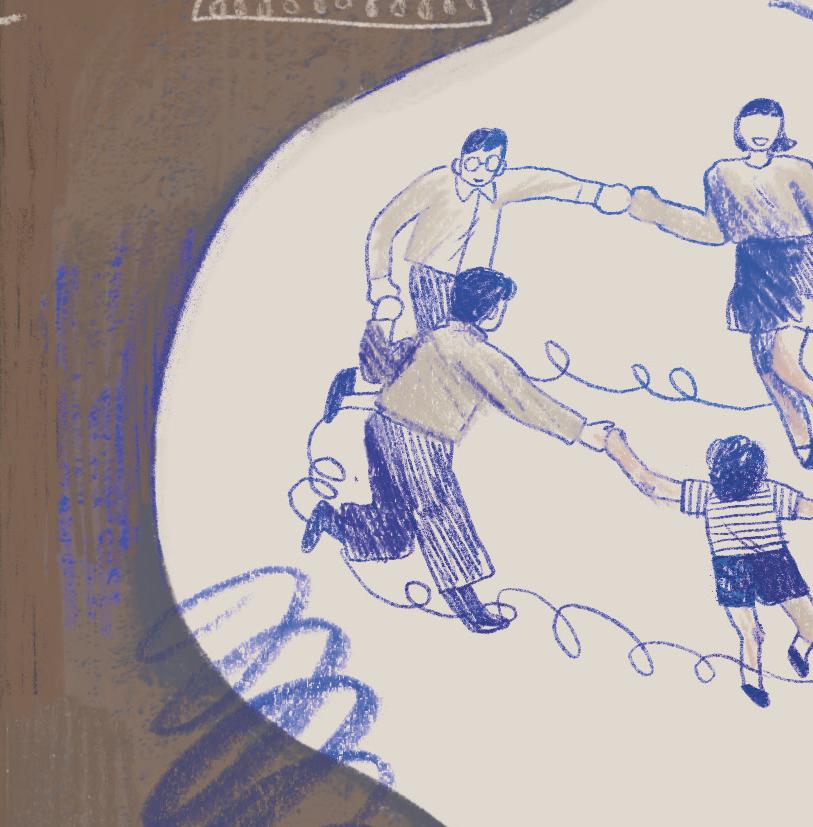

In New York City, critics and collectors began to notice Ruth’s artwork. In San Francisco, she was commissioned to sculpt fountains for public spaces. Ruth surprised the city by creating a mermaid mother and her baby, whose tails curved in undulating lines. Children pointed at the turtles and frogs that splashed around the merfamily.

“Art is for everyone,” Ruth declared. “It is not something that you should have to go to the museums in order to see and enjoy.”

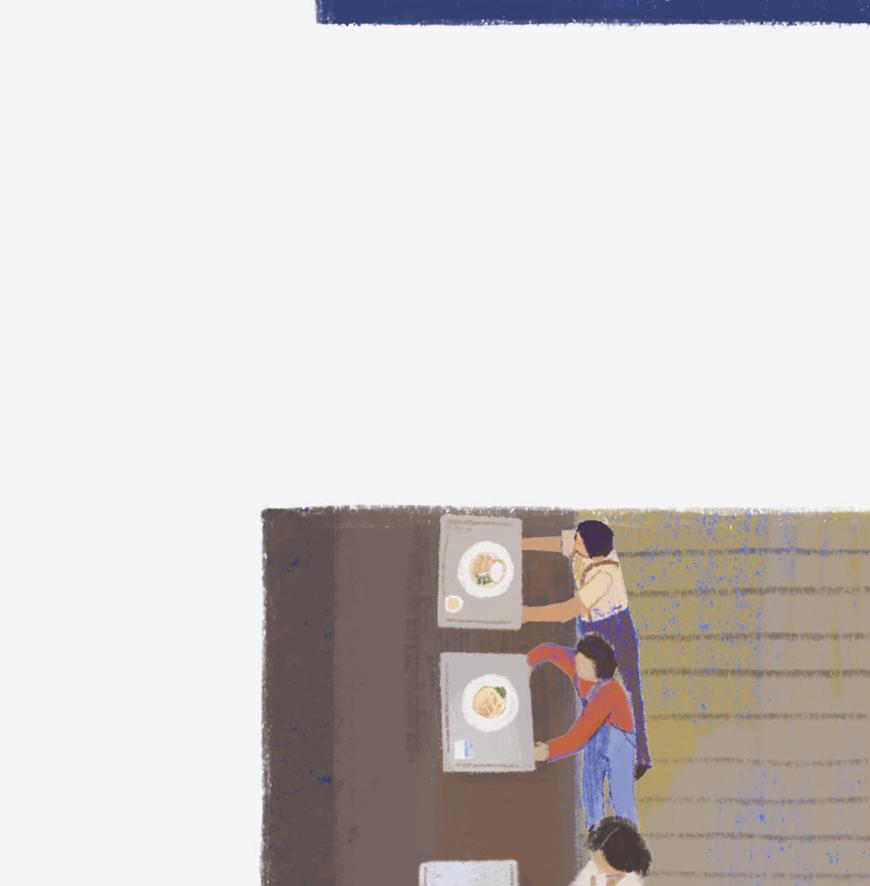

For her next fountain, she invited more than a hundred volunteers, including schoolchildren, neighbors, and family, to help her mold baker’s clay into scenes of San Francisco life. Even her seventy-seven-year-old mother joined in, crafting the fine details of seagulls and leaves. Once the fountain was finished and cast in bronze, it looked like a giant cookie which was just fine with Ruth.

Still, lines from an interrupted childhood hung loose and dangled. How to repair them?

Ruth molded a memorial for the families imprisoned during the war. On the bronze wall, a child’s paper airplane sailed through the barbed wire that surrounded the prison camp.

Ruth’s life curved and twisted, looped and doubled back. Lines divided and met.

Look at how her sculptures curve and curl, with lines that overlap and intersect, connect and divide. They move in the breeze and cast shadows that change with the light. Her art is for everyone and for all of time graceful, breathtaking, mysterious.

Look and then look again. Do you see something new? Where do the lines lead? What do they mean to you?

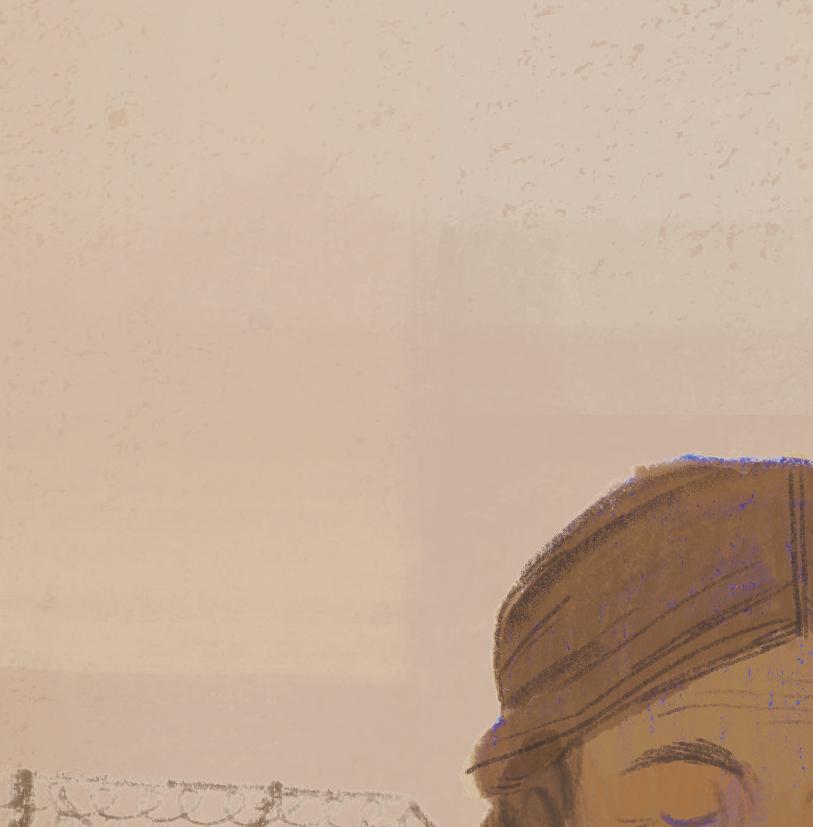

uth’s father, Umakichi, left Japan in 1902 and worked his way from Hawaii to Mexico and then to Utah. He finally settled in Southern California, where he farmed and built his own small house. Ruth’s mother, Haru, was a picture bride. Her family sent photos to Umakichi’s family, and the match was arranged. In 1919, Haru traveled by ocean liner from Japan to California, and the two were married. He was thirty-seven, and she was twenty-five. Haru found life on the farm grueling and isolating. She never learned English but was happy to know that her seven children nisei, or second-generation Japanese Americans would have an easier life than she did. After all, they were born citizens of the United States.

However, the war changed everything. The United States became a hostile place for Japanese Americans. Ruth’s younger sister Kimiko was visiting an aunt in Japan when the war broke out. She had to stay there until 1946. Because Ruth’s father was a leader of the Japanese American community in Norwalk, the government suspected him of disloyalty. FBI officers arrested him and sent him to a prison for “alien enemies” in Lordsburg, New Mexico. For a long time, the family did not know where he was. When the children finally discovered his location, they began a letter-writing campaign to get him transferred to be with the family. He was finally reunited with them after Ruth left for college.

In February 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, stripping the rights of all people of Japanese descent, citizen or not. In April, Ruth’s mother followed the government’s orders, and the family drove to the assembly center at the Santa Anita racetrack, where the seven of them were housed in two horse stalls. A bright spot for Ruth was that professional artists also incarcerated at Santa Anita organized art classes for the children. Tom Okamoto, Chris Ishii, and James Tanaka had worked on such Disney films as Fantasia, Dumbo, and Bambi. Ruth credited Tom Okamoto with teaching her for the first time to draw from life to draw what she saw with her own eyes.

After several months, the government sent Ruth’s family to the Rohwer Relocation Center, a more permanent prison camp in Arkansas. Ruth graduated from the camp high school and applied to college in the Midwest. Influential university presidents as well as Quaker organizations had pressured the government to release college-age prisoners so they could pursue higher education. The caveat was they had to select schools away from the West Coast. Ruth was one of four thousand students who left the prison camps for college.

Ultimately, Ruth chose Milwaukee State Teachers College because it was the most affordable option, and she thought a degree in teaching art would be practical. To pay her expenses, she secured a position as a live-in maid, earning one dollar a week.

When Milwaukee State denied her the degree she had worked so hard to earn, Ruth turned misfortune into opportunity. Friends Elaine Schmitt and Ray Johnson encouraged Ruth to accompany them to Black Mountain College, an experimental liberal arts school in North Carolina. Studying art at Black Mountain, she came under the influence of such midcentury giants as Buckminster Fuller, who developed the geodesic dome; Merce Cunningham, leader and innovator of modern dance; Josef Albers, color theorist and visionary teacher; and Anni Albers, weaver and printer.

At Black Mountain, Ruth also met her husband, architect Albert Lanier. The couple moved to San Francisco, where they found acceptance among an eclectic group of artistic friends, which included the photographer Imogen Cunningham. Cunningham took many of the iconic photos of Ruth with her sculptures.

An early breakthrough for Ruth’s artwork was a show at the Peridot Gallery in New York in 1954. While continuing to craft her hanging sculptures, she also created new tiedwire sculptures based on natural forms such as tumbleweeds. By the end of the decade, in addition to pursuing her art, Ruth had given birth to four children and adopted two. Early reviews of her work often described her as a housewife and dismissed her sculptures as “craft” rather than “art.”

In the 1960s, Ruth began to work with sculptures cast in bronze. From 1966 to 1968, she designed and cast a fountain for Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco. The lead architect for the project had envisioned a sleek, abstract monolith, but Ruth’s design featured a mermaid nursing a baby, and whimsical frogs basking on lily pads. The architect was furious, but Ruth defended her choices by arguing that art should be for everyone. The sculpture is now an important San Francisco landmark.

Ruth designed other fountains in the Bay Area, including the San Francisco Fountain next to the Grand Hyatt Hotel, which she completed in 1973. Exemplifying her dedication to art as a community endeavor, the fountain’s scenes of city life were first molded out of humble baker’s clay, made from flour, salt, and water. Students at her children’s school, Alvarado Elementary, as well as friends and family all contributed details.

In 1994, Ruth turned to commemorating the injustice of Japanese American imprisonment during World War II. She created a bronze bas-relief depicting the history of Japanese Americans—from their arrival in boats, through the incarceration, up to the US government’s 1988 apology. Her final commission was the Garden of Remembrance on the campus of San Francisco State University, designed to honor nineteen Japanese American students whose educations were interrupted when they were incarcerated.

As well as being an artist, Ruth was an activist for arts education. When one of her children brought home a mimeographed outline to color for art class, Ruth was dismayed by what passed for art instruction. She began a program to bring working artists into public schools artists like the ones who had taught her at Santa Anita and Black Mountain. Ruth was also instrumental in founding San Francisco’s public high school for the arts in 1982; it was renamed the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts in 2010.

Ruth famously said, “Sculpture is like farming. If you just keep at it, you can get quite a lot done.” Her sculptures are now in the collections of many prestigious museums, including the de Young in San Francisco; the Getty in Los Angeles; the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston; and the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim, and the Whitney in New York. Her fountains and public commissions are scattered throughout the Bay Area.

Ruth Asawa is a true American hero. She embodied in equal parts genius, persistence, and resilience. She was devoted to her family, to her community, and to her own original artistic vision.

Asawa, Ruth. “Art, Competence, and Citywide Cooperation for San Francisco.” Interview by Harriet Nathan. Bancroft Library Oral History Center, University of California, Berkeley. 1974 and 1976. ia804700.us.archive.org/15/items/artcompetencecity00asawrich/artcompetencecity00asawrich.pdf.

Asawa, Ruth, and Albert Lanier. Oral history interview by Mark Johnson and Paul Karlstrom. Archives of American Art. June 21–July 5, 2002. aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview -ruth-asawa-and-albert-lanier-12222.

Chase, Marilyn. Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2020.

Cornell, Daniell, ed. The Sculpture of Ruth Asawa: Contours in the Air. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

Cotter, Holland. “What to See in New York Art Galleries This Week: Ruth Asawa.” New York Times, October 11, 2017.

Harris, Mary Emma. The Arts at Black Mountain College. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1987.

Inada, Lawson Fusao, ed. Only What We Could Carry: The Japanese American Internment Experience. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2000.

Isenberg, Alison. “‘Culture-a-Go-Go’: The Ghirardelli Square Sculpture Controversy and the Liberation of Civic Design in the 1960s.” Journal of Social History 44, no. 2 (Winter 2010): 379–412.

Lange, Alexandra. “The Forgotten History of Japanese-American Designers’ World War II Internment.” Curbed, January 31, 2017. archive.curbed.com/2017/1/31/14445484/japanese-designers-wwii -internment.

Martin, Douglas. “Ruth Asawa, an Artist Who Wove Wire, Dies at 87.” New York Times, August 17, 2013.

Molesworth, Helen, ed. Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College, 1933–1957. With Ruth Erickson. Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 2015. Exhibition catalog.

Ollman, Leah. “The Industrious Line.” Art in America 95, no. 5 (May 2007): 158–213.

Rountree, Cathleen. “Ruth Asawa: Making Every Moment Count.” In On Women Turning 70: Honoring the Voices of Wisdom, 84–94. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1999. Ruth Asawa Lanier Inc. Ruth Asawa. ruthasawa.com.

Scott, Andrea K. “Ruth Asawa Reshapes Art History.” New Yorker, September 29, 2017.

Storr, Robert, and Jonathan Laib. Ruth Asawa: Line by Line. New York: Christie’s, 2015. Exhibition catalog.

Vartikar, Jason. “Ruth Asawa’s Radical Universalism.” Museum from Home initiative, Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center, Asheville, NC, September 23, 2020. blackmountaincollege.org /ruth-asawas-radical-universalism.